Abstract

Background: A majority of cancer-bereaved siblings report long-term unresolved grief, thus it is important to identify factors that may contribute to resolving their grief.

Objective: To identify modifiable or avoidable family and care-related factors associated with unresolved grief among siblings two to nine years post loss.

Design: This is a nationwide Swedish postal survey.

Measurements: Study-specific questions and the standardized instrument Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Primary outcome was unresolved grief, and family and care-related factors were used as predictors.

Setting/Participants: Cancer-bereaved sibling (N = 174) who lost a brother/sister to childhood cancer during 2000–2007 in Sweden (participation rate 73%). Seventy-three were males and 101 females. The age of the siblings at time of loss was 12–25 years and at the time of the survey between 19 and 33 years.

Results: Several predictors for unresolved grief were identified: siblings' perception that it was not a peaceful death [odds ratio (OR): 9.86, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.39–40.65], limited information given to siblings the last month of life (OR: 5.96, 95% CI: 1.87–13.68), information about the impending death communicated the day before it occurred (OR: 2.73, 95% CI: 1.02–7.33), siblings' avoidance of the doctors (OR: 3.22, 95% CI: 0.75–13.76), and lack of communication with family (OR: 2.86, 95% CI: 1.01–8.04) and people outside the family about death (OR: 5.07, 95% CI: 1.64–15.70). Depressive symptoms (OR: 1.27, 95% CI: 1.12–1.45) and time since loss (two to four years: OR: 10.36, 95% CI: 2.87–37.48 and five to seven years: OR: 8.36, 95% CI: 2.36–29.57) also predicted unresolved grief. Together, these predictors explained 54% of the variance of unresolved grief.

Conclusion: Siblings' perception that it was not a peaceful death and poor communication with family, friends, and healthcare increased the risk for unresolved grief among the siblings.

Keywords: : grief, loss, pediatric cancer, prolonged grief, siblings

Introduction

A majority of cancer-bereaved siblings report that they still grieve years after bereavement.1 They also describe feelings of loneliness2 and poor communication about illness and death.3 The loss of a brother/sister can have a range of consequences for the siblings, including increased risk of mortality,4 negative effects on scholastic achievement, and socioeconomic outcomes in adulthood.5

Grief among children does not occur in isolation: their grief process can be influenced by the grief of the parent(s),6–7 the level of family cohesion, their immediate caregiving environments, and the child's age.6 Little research has probed factors that contribute to siblings' grief after bereavement, with one exception.1 Our previous research, based on the same cohort as this study, showed that 54% still grieve two to nine years after the loss, and the strongest contributing factor to not having worked through their grief was a lack of perceived social support.1

However, predictors of grief have been studied among other groups. A systematic review8 of predictors for complicated grief among bereaved individuals found, among other things, that violent death, the quality of the caregiving or the dying experience, and lack of preparation for the death were associated with grief. However, the vast majority of the studies included in that review were based on adults and the conclusions may not apply to bereaved children.

Notably, the literature about factors influencing the grief of siblings of children with cancer is limited, as previous research among siblings has mainly focused on grief reactions3,9 or consequences of grief5,10 and not grief as an outcome measure. The aim of this study was therefore to identify modifiable or avoidable family and care-related factors during illness and after bereavement that could have an influence on unresolved grief among cancer-bereaved siblings two to nine years post loss. Based on previous literature on bereaved individuals we explored associations between the following variables and unresolved grief: (1) time with the ill brother/sister in the last month of life, (2) communication about and awareness of illness and pending death, and (3) poor quality of death.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

This study derives from a Swedish nationwide survey which focused on siblings' experiences of losing a brother/sister to cancer.9,11 In 2009, all eligible siblings who had a brother/sister who was diagnosed with cancer before the age of 17 years and who died before the age of 25 years during 2000–2007 were invited to participate. To be eligible siblings had to be between the age of 12–25 years at time of loss and at least 18 years of age at time of the study. Siblings had to be born in any of the Nordic countries, speak and understand Swedish, and have a nonconfidential and reachable phone number. The deceased children and their siblings were traced through the Swedish Childhood Cancer Registry and the Swedish Registry population. Multiple siblings per family could participate if they met inclusion criteria.

Eligible siblings (N = 240) were sent a personal introductory letter describing the objectives of the study and an invitation to participate. As all siblings had reached lawful age they could decide independent of their parents about participation. A few days later an assistant phoned the siblings and asked whether they wished to participate. Those who agreed (N = 220), gave their consent, were mailed an anonymous study-specific questionnaire with a response letter, which was supposed to be returned separately from the questionnaire to maintain anonymity. A total of 174 questionnaires were returned (participation rate: 73%).

Fifty-eight percent of the participating siblings were women, and the average time since loss was six years. Mean age was 18 years [standard deviation (SD) = 3.7] at time of death and 24 years (SD = 3.8) at the time of data collection. Most had completed senior high school and were married/cohabiting or living with their parents (Table 1). The Regional Ethics Committee of Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden, approved the study, Dnr 2007:862-31.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Cancer-Bereaved Siblings

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Man | 73 (42) |

| Woman | 101 (58) |

| Age at time of death | |

| Mean (SD) | 18 (3.7) |

| 12–15 years | 49 (30) |

| 16–19 years | 59 (36) |

| 20–25 years | 58 (35) |

| Missing | 8 |

| Age at data collection | |

| Mean (SD) | 24 (3.8) |

| Minimum–maximum | 19–33 |

| Marital status | |

| Married/cohabiting | 74 (43) |

| Lives with parents | 49 (28) |

| Lives with friends | 3 (2) |

| Lives alone | 46 (27) |

| Missing | 2 |

| Place of residence | |

| Rural | 38 (22) |

| Village | 36 (21) |

| Town | 64 (38) |

| City | 32 (19) |

| Missing | 4 |

| Level of education | |

| Elementary school | 27 (16) |

| Senior high school | 124 (72) |

| University | 22 (13) |

| Missing | 1 |

| Time since loss | |

| Mean (SD) | 6 (2.3) |

| 2–4 years | 46 (28) |

| 5–7 years | 60 (36) |

| 8–9 years | 61 (37) |

| Missing | 7 |

Sum of percentages may not equal 100 due to rounding.

SD, standard deviation.

Measures

The study-specific questionnaire was developed according to the method described by Charlton12 and others.9,13–16 Eight bereaved siblings were interviewed and they revealed what had been of importance to them in relation to their bereavement. Thereafter questions to cover the contents were constructed and tested face-to-face with eight other bereaved siblings to ensure understanding and interpretation as intended. It consists of around 200 questions about siblings' current life situation and health, experiences during the illness period, time of death, and after bereavement. This particular article is based on 29 close-ended questions from that specific questionnaire.

Grief

Grief was measured by the following question: “Do you think you have worked through your grief over your sibling's death?” The response alternatives were: “No, not at all,” “Yes, to some extent,” “Yes, a lot,” “Yes, completely,” and “Not applicable, I was too young.” The question has been previously validated by Sveen et al.1 In this study, we refer to worked through grief as resolved grief and not worked through grief as unresolved grief.

Family and care-related factors

We included 14 family and care-related questions (Table 2), covering the areas hypothesized to influence grief: less time together with the ill brother/sister the last month of life (1 question), inadequate communication and awareness about illness and death (10 questions), and poor quality of death (3 questions).

Table 2.

Bivariate and Multivariate Associations between Unresolved Grief and Family and Care-Related Factors Two to Nine Years after the Loss of a Brother or Sister to Cancer

| Unresolved grief/total N | Bivariable regressions OR (95% CI) | Multiple regression OR (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spending less time together with the ill brother/sister | |||

| Amount of time that the sibling spent with the brother/sister weekly | |||

| No time/occasionally | 11/18 | 1.43 (0.52–3.93) | — |

| Every week/every day (references) | 68/130 | ||

| Poor communication and awareness about illness and death | |||

| Satisfied with the amount of information about the brother's/sister's illness | |||

| Wanted more information | 45/66 | 3.03 (1.53–5.97) | 5.06 (1.87–13.68) |

| Wanted less information/content (references) | 34/82 | ||

| Avoided the brother's/sister's doctors for fear of what they might say | |||

| Yes | 10/16 | 1.62 (0.56–4.69) | 3.22 (0.75–13.76) |

| No (references) | 68/131 | ||

| Sibling satisfied with how often he/she talked with someone outside the family about his/her feelings about the illness | |||

| Wanted to talk more | 33/47 | 2.82 (1.35–5.90) | — |

| Wanted to talk less/content (references) | 45/100 | ||

| Sibling's understanding that the brother/sister would die | |||

| No/little | 39/65 | 1.59 (0.82–3.07) | — |

| To some extent/to a great extent/completely (references) | 40/82 | ||

| Informed by a family member and/or a professional about the impending death during the last 24 hours before it occurred | |||

| Yes | 57/96 | 1.99 (1.01–3.95) | 2.73 (1.02–7.33) |

| No (references) | 22/52 | ||

| Was told what to expect when the brother/sister was about to die | |||

| Yes (references) | 10/27 | ||

| No | 69/121 | 0.44 (0.19–1.05) | — |

| Talked to anyone about the brother's/sister's death | |||

| Yes (references) | 53/110 | - | |

| No | 26/38 | 2.33 (1.07–5.08) | |

| Avoided talking to the parents about his/her feelings out of respect for the parents' feelings | |||

| Yes | 56/83 | 3.77 (1.90–7.49) | — |

| No (reference) | 23/64 | ||

| Sibling content with how often he/she had been able to share feelings about the brother's/sister's death with the family | |||

| Wanted to talk more | 40/52 | 4.87 (2.27–10.44) | 2.86 (1.01–8.04) |

| Wanted to talk less/content (references) | 39/96 | ||

| Sibling content with how often he/she had been able to share feelings about the brother's/sister's death with people outside the family | |||

| Wanted to talk more | 39/52 | 4.01 (1.90–8.45) | 5.07 (1.64–15.70) |

| Wanted to talk less/content (references) | 40/95 | ||

| Poor quality of death | |||

| Noticed suffering in the last hours of life | |||

| Yes | 50/84 | 1.47 (0.64–3.40) | — |

| No | 14/34 | 0.70 (0.26–1.88) | — |

| Not there (references) | 15/30 | ||

| Resuscitation attempt | |||

| Yes | 72/131 | 0.55 (0.15–2.02) | — |

| No (references) | 3/7 | ||

| Don't know | 4/10 | 0.61 (0.13–2.86) | — |

| A feeling of peace and quietness at time of death | |||

| Yes | 31/61 | 1.18 (0.58–2.39) | 1.55 (0.52–4.59) |

| No | 18/25 | 2.84 (1.04–7.77) | 9.86 (2.39–40.65) |

| Not present (references) | 29/61 | ||

| Siblings' characteristics and symptoms of depression | |||

| Sex | |||

| Male (references) | 30/61 | ||

| Female | 49/87 | 1.33 (0.69–2.57) | — |

| Age at time of death | |||

| Continuous (OR = 1 year) | 1.00 (0.91–1.09) | — | |

| Time since loss | |||

| 2–4 years | 29/43 | 3.11 (1.34–7.27) | 10.36 (2.87–37.48) |

| 5–7 years | 32/52 | 2.67 (1.19–5.96) | 8.36 (2.36–29.57) |

| 8–9 years (references) | 16/47 | ||

| Depression | |||

| Continuous (OR = 1 point on HADSb) | 1.27 (1.12–1.45) | 1.31 (1.11–1.53) | |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.54 | ||

OR and 95% CI are shown only for the factors that contributed to the multivariate model based on AIC selection criteria (see Data Analyses).

Scores on HADS range from 0 to 21 points and have in this study been used as a continuous variable.

AIC, Akaike information criterion; CI, confidence interval; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; OR, odds ratio.

Siblings' characteristics and depression

Seven questions about siblings' demographic characteristics were included to describe the sample (Table 1), but only three of them were used as predictors for grief (Table 2). In addition, we included the depression subscale (seven items) from the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).17,18 The response alternatives score 0–3 points for each question; thus the possible scores range from 0 to 21.

Data analyses

A multivariable prediction model was built, including all variables found to be significantly associated with unresolved grief in univariate analyses. The dependent variable grief was dichotomized; the response alternatives “No, not at all” and “Yes, to some extent” represented unresolved grief, while “Yes, a lot” and “Yes, completely” represented resolved grief. Siblings who provided no answer to this question and those who responded “Not applicable, I was too young” were excluded from the analysis (N = 26). To handle nonresponses to individual questions, 100 imputation-completed datasets were created using Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE). These datasets were used for univariable and multivariable modeling, whereas the original incomplete data were used for all descriptive statistics. The continuous variables depression and age were used with linear parametrizations for modeling, whereas time since loss was categorized to give three groups of approximately equal size, as preliminary findings suggested a nonlinear association with the outcome (data not shown).

To select which variables to include in a multivariable model, a preliminary model was created from each imputation-completed dataset through backward selection, using the small-sample corrected Akaike information criterion (AICc) as selection criterion. It has previously been found that unresolved grief is associated with depression and time since loss.1 Hence, we forced these two variables into all models to avoid selection of related variables in their stead. AICc and related measures are used to identify which model out of those considered minimizes the information loss between the true data-generating process and the model, but may result in a model where not all included covariates are statistically significant at 5% significance level.19 The variables which were included in at least half of the 100 preliminary models were considered globally selected,20 and a final imputation-pooled model was formed using these variables.

Overall model fit was assessed with the Nagelkerke R2. Correlations between variables included in the final model were assessed using variance inflation factors (VIF), and variables having VIF >5 were considered as showing severe multicollinearity. All variables included in the final model had VIF <2, indicating no problematic multicollinearity.

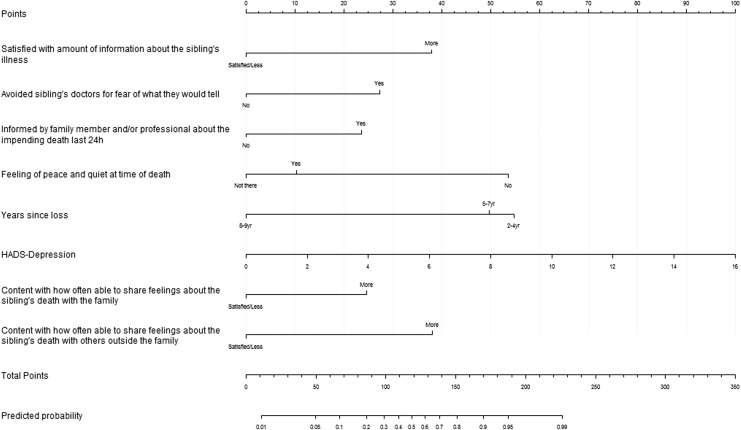

The statistical analysis was carried out using R version 3.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), using the mice and rms packages. The results of the analyses are illustrated in Table 2 [with odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI)] and Figure 1 (showing a model that allows calculation of the estimated probability of unresolved grief in a sibling).

FIG. 1.

Factors that contributed to unresolved grief among cancer-bereaved siblings. To calculate the estimated probability of unresolved grief in a sibling, go through the variables included in the Nomogram and mark the values which correspond to the individual's circumstances. Use the scale at the top to assign a number of points for each value (e.g., a sibling with five to seven years since loss is scored 50 points for this variable). Finally, sum up the points from all variables and use the two scales at the bottom to convert the total points to a predicted probability, for example, a sibling whose values score a total of 100 points has a 31% probability of unresolved grief.

To avoid overfitting, that is, inclusion of unnecessary/uninformative variables in a multivariable model, we adjust for that through the small-sample AICc. AICc balances model fit and sparsity by rewarding a model depending on how well it fits the data, while simultaneously punishing the model proportional to the number of predictors it includes.

As this study derives from a larger survey the original power calculation was not based on the variable grief, but on difference in anxiety (HADS) between siblings who reported awareness of their brother's or sister's impending death and siblings who were not. Nevertheless, for illustrative purposes we have performed a post hoc power calculation for this study. Given 79 individuals with and 69 individuals without unresolved grief and that 50% of those without unresolved grief have a certain characteristic, the minimum odds ratio that can be detected at 5% significance level with 80% power is 2.7.

Results

Siblings' characteristics

The sample included for the multivariable modeling (148/174) differed slightly from the rest of the sample in that these siblings were older (mean age at time of death: 18 years vs. 15, p < 0.001) and had more education (15% of the included siblings had finished university vs. none of those excluded, p < 0.05). These differences are explained by our exclusion of siblings who had stated “Not applicable, I was too young” from the multivariable modeling.

Factors influencing unresolved grief

The results of the multivariable analysis showed that communication and awareness of illness and death and poor quality of death influenced unresolved grief, whereas spending time together with the ill brother/sister the last month of life did not. Two other factors of importance were symptoms of depression and time since loss (Table 2, Fig. 1). The Nomogram (Fig. 1) complements Table 2 by calculating the estimated probability of unresolved grief in a sibling. For example, a sibling who lost a brother/sister five years ago, who wanted more information about the illness, and did not experience a peaceful death has an ∼60% probability of unresolved grief.

Three factors that assessed communication and awareness of illness and death (siblings satisfaction with how often he/she talked with someone outside the family about his/her feelings about the illness; if the sibling had talked to anyone outside the family about the brother's/sister's death; if the siblings had avoided talking to the parents about his/her feelings out of respect for the parents' feelings) influenced unresolved grief in the bivariate analysis, but showed no impact in the multivariate model (Table 2). Below, the results of the multivariable model are described.

Communication and awareness of illness and death

Two factors relative to the last month of the brother's or sister's life influenced unresolved grief in the multivariable model: siblings who were dissatisfied with the amount of information they received about the brother's/sister's illness had a higher risk of unresolved grief, as did siblings who avoided the brother's/sister's doctors for fear of what they might tell them about the illness (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Those who were informed by a family member and/or healthcare staff about the impending death in the last 24 hours before it occurred had higher risk of reporting unresolved grief than those who were not informed in the last 24 hours (Table 1, Fig. 1). When we further examined this relation we found that among those who received information about the impending death 24 hours before it occurred, hospital deaths were more common than home deaths (p = 0.034).

At follow-up, siblings who wanted to talk more about the brother's/sister's death with their family and with people outside the family had a greater risk than those who were content or wanted to talk less (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Poor quality of death

One factor related to poor quality of death influenced unresolved grief: that the sibling perceived lack of peace and quiet at the time of the brother's/sister's death (Table 2, Fig. 1). As illustrated by the Nomogram this factor had the strongest impact on unresolved grief of all the family and care-related factors we examined.

Symptoms of depression and time since loss

Factors outside the family and care that influenced unresolved grief among siblings were symptoms of depression and shorter time since loss. As illustrated in Figure 1, passage of more than seven years since loss was associated with a lower risk for unresolved grief, whereas shorter time since loss, two to seven years, showed a higher risk (two to four years: OR: 10.36, 95% CI: 2.87–37.48 and five to seven years: OR: 8.36, 95% CI: 2.36–29.57).

All factors included in the multivariable model explained 54% of the variance in unresolved grief (R2 = 0.544).

Discussion

This nationwide study showed that the siblings' perception of a nonpeaceful death, poor medical information, siblings' avoidance of the physicians, and poor communication about the brother's/sister's death with family and friends predicted unresolved grief two to nine years post loss. Depressive symptoms and time since loss also contributed to unresolved grief.

One factor related to poor quality death was associated with unresolved grief: siblings' experience that the death was not peaceful. The results echo those of Barry et al.21 who found that when bereaved individuals (mostly spouses) perceived the death as violent, this was associated with major depression. We have also previously reported that some siblings describe stressful situations at the time of death, for example, dramatic symptoms, as complicating their grieving process. Dramatic bodily changes such as rattle breath or seizure at the time of death were frightening to some siblings, as they did not understand what was happening or why nobody helped their brother/sister.3

Previous research22 has found that siblings reporting being dissatisfied with communication and the amount of information received had higher distress, which is similar to the results in this study showing that dissatisfaction with communication and information about the illness predicted unresolved grief. Receiving information about the illness is described as one step in becoming aware of and prepared for the impending death.23 However, our results also showed that those who were informed about the impending death during the last 24 hours had a higher risk for unresolved grief. This finding surprised us, as previous studies have shown that siblings want to be informed about illness and death.3 We therefore did a closer analysis of those who received the information at that time and found that death at a hospital was more common in this group, which might be associated with the brother/sister taking a sudden turn for the worse. Given that siblings have described how rapid deterioration has led to missed opportunities to say goodbye and negative emotional reactions later on,3 we want to highlight this as a potential confounder.

Avoidance of physicians, which influenced unresolved grief in this study, might result in poor information and thus lead both to less awareness about the impending death and lower preparedness. We have previously shown that siblings who avoided healthcare staff for fear of being in their way, especially at the hospital, had a higher risk for long-term anxiety.24 Both we24,25 and others26 have highlighted siblings' relationship and communication with staff in previous reports, where the importance of including siblings in the care has been emphasized directly by the siblings25 and in SIOP guidelines.27 The siblings have also expressed that staff should not give up trying to offer help, even if the sibling did not seem to need it, and that the initiative to contact must come from staff.25 The value of communication and psychological support for long-term grief has earlier been found among bereaved parents.28 Previous research suggests that social support is especially important for siblings' grief.1 This can be strengthened by our findings that poor communication about the brother's/sister's death with family and especially with people outside the family predicted unresolved grief. Unfortunately, siblings report that they are alone with their feelings and disappointed in the extended family.2,29

Notably, our study showed that the risk for unresolved grief was much lower after seven years. Seven years is a long time when you are young and much can happen during that period. A sibling's death during childhood has been found to have negative consequences on scholastic achievement and socioeconomic outcomes in adulthood,5 which underscore the need for methods to prevent these unwanted effects. Depression was also found to be associated with unresolved grief. However, 87% of this sample of cancer-bereaved siblings show no signs of depression9 even though 54% still grieve two to nine years after the loss.1 This indicates that grief and depression are related, but that depression is not the underlying cause of grief for most of these siblings.

Even though this is a nationwide study with a high participation rate, it has shortcomings. The self-reports were done in retrospect and can suffer from recall bias. The outcome variable, grief, relies on a single item that has been used before.30 In contrast, the question has been validated1 in relation to questions from the Inventory of Complicated Grief.31 As a correlation was found, we can assume that our question is related to the concept “prolonged grief.”32 Grief among siblings also needs to be further explored. For example, the lack of longitudinal data on siblings' grief makes it difficult to define a “normal” grief trajectory among siblings.

In conclusion, several of the factors that influenced unresolved grief among siblings can be avoided or modified with the right support from healthcare, family, and people outside the family. For example, siblings who perceived that the death was not peaceful might benefit from being offered support to understand the situation. Staff also needs to give information about the illness, establish a relationship with siblings, and encourage the patient's relatives to communicate both within the family and with people outside the family about bereavement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all siblings who made this study possible. Funding for this project has been provided by the Swedish Childhood Cancer Foundation, the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Research Council, and Gålö Foundation.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Sveen J, Eilegård A, Steineck G, Kreicbergs U: They still grieve-a nationwide follow-up of young adults 2–9 years after losing a sibling to cancer. Psychooncology 2014;23:658–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nolbris M, Hellström AL: Siblings' needs and issues when a brother or sister dies of cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2005;22:227–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lövgren M, Jalmsell L, Eilegård Wallin A, et al. : Siblings' experiences of their brother's or sister's cancer death: A nationwide follow-up 2–9 years later. Psychooncology 2015;25:435–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li J, Vestergaard M, Cnattingius S, et al. : Mortality after parental death in childhood: A nationwide cohort study from three Nordic countries. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fletcher J, Mailick M, Song J, Wolfe B: A sibling death in the family: Common and consequential. Demography 2013;50:803–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warnick AL: Supporting youth grieving the dying or death of a sibling or parent: Considerations for parents, professionals, and communities. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2015;9:58–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris AT, Gabert-Quillen C, Friebert S, et al. : The indirect effect of positive parenting on the relationship between parent and sibling bereavement outcomes following the death of a child. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:60–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lobb EA, Kristjanson LJ, Aoun SM, et al. : Predictors of complicated grief: A systematic review of empirical studies. Death Stud 2010;34:673–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eilegård A, Steineck G, Nyberg T, Kreicbergs U: Psychological health in siblings who lost a brother or sister to cancer 2 to 9 years earlier. Psychooncology 2013;22:683–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrera M, Alam R, D'Agostino NM, et al. : Parental perceptions of siblings' grieving after a childhood cancer death: A longitudinal study. Death Stud 2013;37:25–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eilegård A, Steineck G, Nyberg T, Kreicbergs U: Bereaved siblings' perception of participating in research: A nationwide study. Psychooncology 2013;22:411–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charlton R: Research: Is an “ideal” questionnaire possible? Int J Clin Pract 2000;54:356–359 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdóttir U, Onelöv E, et al. : Talking about death with children who have severe malignant disease. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1175–1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grenklo TB, Kreicbergs UC, Valdimarsdottir UA, et al. : Communication and trust in the care provided to a dying parent: A nationwide study of cancer-bereaved youths. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2886–2894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rådestad I, Steineck G, Nordin C, Sjogren B: Psychological complications after stillbirth—influence of memories and immediate management: Population based study. BMJ 1996;312:1505–1508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valdimarsdóttir U, Kreicbergs U, Hauksdóttir A, et al. : Parents' intellectual and emotional awareness of their child's impending death to cancer: A population-based long-term follow-up study. Lancet Oncol 2007;8:706–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herrmann C: International experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: A review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res 1997;42:17–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP: The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burnham KP, Anderson DR: Multimodel inference: Understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Socio Meth Res 2004;33:261–304 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wood AM, White IR, Royston P: How should variable selection be performed with multiply imputed data? Stat Med 2008;27:3227–3246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barry LC, Kasl SV, Prigerson HG: Psychiatric disorders among bereaved persons: The role of perceived circumstances of death and preparedness for death. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002;10:447–457 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenberg AR, Postier A, Osenga K, et al. : Long-term psychosocial outcomes among bereaved siblings of children with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;49:55–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hauksdóttir A: Towards Improved Care and Long-Term Well-Being of Men Who Lose a Wife to Cancer: A Population Based Study. Stockholm: Karolinska Institute, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallin AE, Steineck G, Nyberg T, Kreicbergs U: Insufficient communication and anxiety in cancer-bereaved siblings: A nationwide long-term follow-up. Palliat Support Care 2016;14:488–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lövgren M, Bylund-Grenklo T, Jalmsell L, et al. : Bereaved siblings' advice to health care professionals working with children with cancer and their families. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2016;33:297–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaab EM, Owens GR, MacLeod RD: Siblings caring for and about pediatric palliative care patients. J Palliat Med 2014;17:62–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spinetta JJ, Jankovic M, Eden T, et al. : Guidelines for assistance to siblings of children with cancer: Report of the SIOP Working Committee on Psychosocial Issues in Pediatric Oncology. Med Pediatr Oncol 1999;33:395–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kreicbergs UC, Lannen P, Onelöv E, Wolfe J: Parental grief after losing a child to cancer: Impact of professional and social support on long-term outcomes. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:3307–3312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eilertsen ME, Eilegård A, Steineck G, et al. : Impact of social support on bereaved siblings' anxiety: A nationwide follow-up. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2013;30:301–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lannen PK, Wolfe J, Prigerson HG, et al. : Unresolved grief in a national sample of bereaved parents: Impaired mental and physical health 4 to 9 years later. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5870–5876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF, 3rd, et al. : Inventory of complicated grief: A scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Res 1995;59:65–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maercker A, Brewin CR, Bryant RA, et al. : Proposals for mental disorders specifically associated with stress in the International Classification of Diseases-11. Lancet 2013;381:1683–1685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]