Abstract

Background: Sleep fragmentation is common among those with advanced serious illness. Nonpharmacological interventions to improve sleep have few, if any, adverse effects and are often underutilized in these settings.

Objective: We aimed to summarize the literature related to nonpharmacological interventions to improve sleep among adults with advanced serious illness.

Methods: We systematically searched six electronic databases for literature reporting sleep outcomes associated with nonpharmacological interventions that included participants with advanced serious illness during the period of 1996–2016.

Results: From a total of 2731 results, 42 studies met the inclusion criteria. A total of 31 individual interventions were identified, each evaluated individually and some in combination with other interventions. Twelve of these studies employed either multiple interventions within an intervention category (n = 8) or a multicomponent intervention consisting of interventions from two or more categories (n = 5). The following intervention categories emerged: sleep hygiene (1), environmental (6), physical activity (4), complementary health practices (11), and mind–body practices (13). Of the 42 studies, 22 demonstrated a statistically significant, positive impact on sleep and represented each of the categories. The quality of the studies varied considerably, with 17 studies classified as strong, 17 as moderate, and 8 as weak.

Conclusions: Several interventions have been demonstrated to improve sleep in these patients. However, the small number of studies and wide variation of individual interventions within each category limit the generalizability of findings. Further studies are needed to assess interventions and determine effectiveness and acceptability.

Keywords: : circadian rhythms, integrative review, nonpharmacological

Introduction

Sleep fragmentation is associated with increased morbidity and decreased quality of life, as well as increased use of healthcare services.1,2 In patients with advanced serious illness, sleep is often disrupted due to the underlying condition or comorbidities, including cancer,3 renal failure,4 pulmonary disease,5 coronary artery disease,6 congestive heart failure,7 or dementia.8 Poorly controlled symptoms of pain, dyspnea, fatigue, anxiety, or depression significantly impact sleep quality in these patients.9–11 Similarly, insomnia can increase the intensity of these symptoms and further complicate symptom management.1 The medical treatments for these serious illnesses often unfavorably affect sleep.12

The practices of institutions and clinicians also impact sleep. For patients who are hospitalized or are in an institutionalized setting, environmental factors that hinder restful sleep include high levels of nighttime noise and light, low levels of daytime bright or natural light, lack of daytime activity, and nighttime treatments or assessments.13

The management of sleep disturbances is as complicated as these multiple etiologic factors. The adverse effects of long-term hypnotic use are well documented, highlighting the need for nonpharmacological interventions.14 Clinical guidelines suggest avoidance of benzodiazepines15,16 and nonbenzodiazepine sedative–hypnotics.17

Nonpharmacological approaches such as cognitive behavioral interventions, sleep hygiene, and environmental interventions, are increasingly being used because there is little or no risk of adverse effects and result in more sustained effects than medications.18 There is mounting evidence of these interventions' efficacy with patients in the early stages of a serious illness,19 and with cancer survivors20 is cited in the guidelines of major professional associations.1,21 The evidence of the treatments' effectiveness in those with advanced illness, however, is not clearly delineated in the literature.

The objective of this integrative review is to summarize the existing international literature related to nonpharmacological interventions to improve sleep and circadian rhythms among adults with advanced serious illness. The intent is to evaluate the extent and nature of the available evidence concerning both single- and multicomponent nonpharmacological interventions, as well as to outline potential directions for future research.

Methods

We performed systematic reviews of several electronic databases (Medline Complete, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Wiley Interscience, Ageline, Academic Search Premier, and AMED). Table 1 provides an example of the Boolean/Phrase that details the key words and MESH terms, as well as the limits employed in the search. Table 2 outlines our inclusion and exclusion criteria. This search resulted in a total of 2525 articles. We supplemented this with a hand search of reference lists from relevant literature reviews22–24 and all sleep studies that were cited in the Oncology Nurses Society's “Putting Evidence into Practice” website,21 resulting in an additional 206 articles.

Table 1.

Search Boolean/Phrase (Medline Complete Example)

| AB (Sleep OR insomnia OR “sleep wake disturbances” OR “Circadian Rhythm” OR ““sleep wake cycle” OR “sleep wake disorders” OR “biological clocks” OR “sleep phase) AND TX (Palliative OR hospice OR terminal Or end-of-life OR “advanced stage” OR “advanced serious illness” OR end-stage” OR “advanced life limiting illness”) AND TX (Non-pharmacological OR light OR noise OR education OR temperature OR “physical environment” OR facility OR window OR comfort OR ergonomics) AND TX intervention |

| Limiters: English language, All Adults (19+), Years January 1996-December 2016, Academic journals |

Table 2.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| English language publications irrespective of the country was conducted | |

| Intervention studies published in peer-reviewed journals | Systematic reviews, dissertations, presentation abstracts, brief reports, letters to the editors |

| Nonpharmacological interventions | Model of care (e.g., palliative care team) as an intervention instead of a specific intervention |

| Experimental or quasi-experimental studies | Single case studies or studies with a cross-sectional design |

| Adult participants with advanced or serious illness, that is, there is no cure for their illness, general health and functioning decline, and treatments begin to lose their impact. This includes advanced cancer, moderate-to-late state Alzheimer's Disease/dementia, end-stage renal disease, and those receiving palliative, long-term care, or hospice services at home or in a nursing home. For those with cancer, “advanced,” recurrent, metastatic (such as stage IV prostate, breast, head/neck, or colorectal cancer, and stages IIIB or IV lung cancer) | Cancer patients in remission or considered a survivor without expectation of recurrence |

| Any setting, including palliative care or hospice | Simulated healthcare setting |

| Sleep as a subjective (self-reported) or objective outcome (primary or secondary) | Sleep not measured with tools |

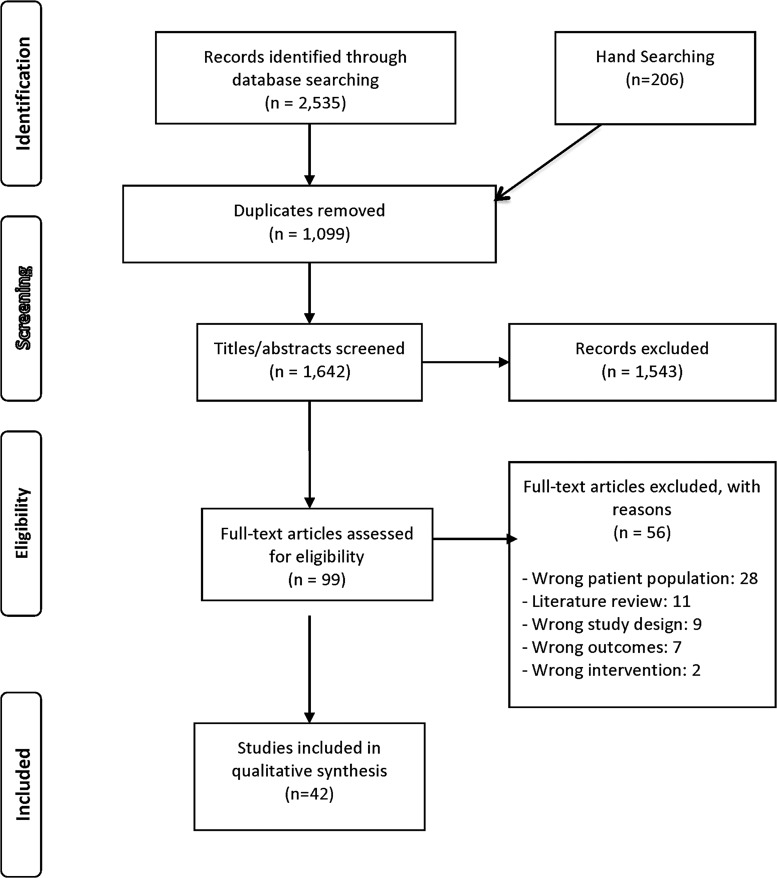

The process of article selection is presented in a PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1). After the duplicates were removed (1099), the titles and abstracts of 1642 articles were evaluated, resulting in 99 articles remaining for full review. Of these, a final data set of 42 articles met the study's criteria.

FIG. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

The characteristics of included studies (Table 3) were summarized by two research assistants (N.W. and A.B.) and then reviewed by two investigators (E.C. and R.Z.). The Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies, developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project, was used to critically appraise each study (Table 4).25 Each study was classified based on overall global rating of the methods, including selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, and withdrawals/dropouts. Each criterion was rated as strong, moderate, or weak. We considered studies to be of high quality if none of the criteria was weak, of moderate quality if there was only one weak rating, and weak if there were two or more weak ratings. Any conflicts were resolved among all team members. In the data extraction process each member re-read each study and developed an initial list of codes for the intervention type. The interventions were grouped into categories based on consensus among the team members.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| References | Study objective | Setting and location | Sample and participant characteristic | Design and data collection | Sleep measure and other outcomes | Intervention | Nighttime sleep and other applicable results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alessi et al.43 | To test whether an intervention combining increased daytime physical activity with improvement in the nighttime environment improves sleep and decreases agitation in nursing home residents. | LTCF; one community nursing home, Los Angeles, California | n = 29 residents with incontinence; mean age 88.3 years, 90% female | RCT with one group receiving intervention + nighttime program and the control group receiving only the nighttime program | Sleep: actigraphy (wrist) at night + behavioral observations of sleep | Multicomponent—physical activity (increased daytime physical activity) + Sleep hygiene (reduce nighttime disruptions) | Positive: Nighttime% sleep increased in intervention group from 51.7% to 62.5% compared with 67.0% to 66.3% in controls |

| Alessi et al.28 | To test a multidimensional, nonpharmacological intervention to improve abnormal sleep/wake patterns in nursing home residents | LTCF,a four nursing homes; Los Angeles, California |

n = 118 Residents with sleep problems; mean age = 86.9 years, 90% nonHispanic white, 77% female |

RCT, facility clustered | Sleep: Actigraphy (wrist) for 72 consecutive hours of nighttime sleep plus structured behavioral observations of daytime sleep Other outcomes: Social and physical activities |

Multicomponent: Environmental (increased daytime light with 30 minutes sunlight and decreased nighttime light and noise), Physical activity, and sleep hygiene (decreased daytime in-bed time and structured bedtime routine) × 5 days/nights | Positive: Significant decrease in daytime sleeping and modest decrease in mean duration of nighttime awakenings in intervention group vs. control |

| Birocco et al.60 | To investigate the role of Reiki in the management of anxiety, pain, and global wellness in cancer patients | Outpatient; Italy |

n = 118 Adults with cancer at any stage and receiving any kind of chemotherapy; mean age 55 years, 57% female |

Pre–post test design with one group recruited over three years | Sleep: Symptom survey questions Other outcomes: Pain, anxiety, and physical feelings during each session | Complementary health practices—Touch: Reiki sessions were provided a maximum of four times during chemotherapy infusions for about 30 minutes | Positive trend: 34% of patients reported improved sleep quality, not statistically significant |

| Cheville et al.39 | To estimate the effect of a limited intensity and duration REST (Rapid, Easy Strength Training) exercise program and pedometer-based walking program on self-reported mobility, as well as pain, quality of life, fatigue, sleep quality, and the ability to perform daily activities | Home; Mayo Clinic Outpatient Oncology Clinic, Minnesota |

n = 66 Adults with Stage IV lung or colorectal cancer recruited from an oncology center. Intervention group: 33 patients, mean age 63.8 years, 52% female. Control group: 33 patients, mean age 65.5 years, 42% female. Mostly Caucasian. |

RCT, data collected immediately before and after the eight-week intervention | Sleep: Symptom Numeric Rating Scales Other outcomes: Self-reported measures of mobility, function, quality of life, fatigue, and pain |

Physical exercises over eight weeks of incremental walking and home-based strength training. A 90-minute instructional session plus bimonthly phone calls by physical therapist to review and advance program goals. | Positive: Intervention group reported improved sleep quality compared with the usual care group |

| Dowling et al.31 | To test the effectiveness of morning bright light therapy in reducing rest and disrupting circadian rhythms in institutionalized patients | LTCF, two large skilled nursing facilities; San Francisco, California | n = 46 Participants with Alzheimer's disease and staff-identified rest–activity disruption; mean age 84 years, 78% female, 80.4% Caucasian | RCT, placebo-controlled clinical trial; 12-week protocol with assessments at weeks 1 and 11 | Sleep: Actigraphy (wrist) | Environmental: Increased daytime light; morning bright light exposure for one hour Monday through Friday for 10 weeks | Negative: No significant improvement in experimental group; only those with the most impaired rest–activity rhythm had significantly positive results |

| Dowling et al.37 | To test whether the addition of melatonin to bright light therapy enhances efficacy in treating rest–activity (circadian) disruption in institutionalized patients with Alzheimer's disease | LTCF, two nursing homes; San Francisco, California |

n = 50 Residents with Alzheimer's disease and a rest–activity rhythm disruption; mean age = 86 years, 86% female |

RCT, three groups: Morning bright light + melatonin, morning bright light + placebo or usual indoor light (150–200 lux; control group) |

Sleep: Actigraphy (wrist) continuously during each monitoring period, which consisted of five nights and four days (Monday 8:00 p.m. through Saturday 8:00 a.m.) for a total of 108 possible hours per subject |

Multicomponent: Environmental and mind–body practice; two interventions 10 weeks of either morning (9:30–10:30 a.m.) bright light exposure (≥2500 lux in gaze direction) + evening administration of 5 mg of melatonin or morning bright light exposure plus evening lactose placebo administration | Mixed: Daytime sleep decreased and daytime activity increased significantly in the light + melatonin group compared with either the light alone or control groups. Neither intervention significantly improved nighttime sleep. |

| Ducloux et al.51 | To assess whether relaxation therapy can improve satisfaction with sleep in hospitalized patients with advanced cancer and sleep disorders | Hospital; Switzerland |

n = 11 Inpatients with advanced metastatic cancer and sleep problems; mean age 61 years in immediate-intervention group and 66 years in delayed-intervention group |

RCT; two groups—either immediate (treatments on days three through six) or delayed-intervention group (treatment on days six to nine) | Sleep: Numerical rating scale of satisfaction with sleep and a daily sleep diary | Mind–body practice—relaxation: One-hour training session (deep breathing exercises, somatic tension release, somatic relaxation), and audio recording before sleep | Positive: No significant changes, but both groups' sleep improved |

| Espie et al.44 | To investigate the clinical effectiveness of a protocol-driven cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for persistent insomnia, delivered by oncology nurses | Outpatient; two outpatient cancer centers; Scotland |

n = 150 Adults who had completed active therapy for breast, prostate, colorectal, or gynecological cancer and had problems with sleep; mean age 61 years, 68.7% female |

RCT; data collected at baseline, post-treatment, and at six-month follow-up | Sleep: Actigraphy (wrist) for 10 days at each of three assessments and sleep diary Other outcomes: Health-related quality of life, psychopathology, and fatigue |

Mind–body practices—CBT: Five weekly 50-minute, group sessions of CBT (stimulus control, sleep restriction, and cognitive therapy strategies) | Positive: The intervention group, compared with the control, experienced a mean reduction in wakefulness of 55 minutes per night immediately post-intervention and 6 months after treatment |

| Fetveit et al.34 | To evaluate the effects of bright light therapy among nursing home patients with dementia and sleep disturbances | LTCF; one nursing home; Norway |

n = 11 Residents with dementia; mean age 86.1 years, 91% female |

Pre–post test design with one group (subjects served as their own controls) | Sleep: Actigraphy (wrist) and nursing staff ratings of sleep/wakefulness disturbances as measured during a two-week pretreatment period and a two-week treatment period | Environmental: Bright light exposure (bright light box with a light intensity of 6000–8000 lux at a distance of 60–70 cm) for two hours per day (08:00–11:00) for two weeks |

Positive: Following the intervention, sleep efficiency improved, and total wake time and sleep onset latency were reduced. Nurse ratings improved for sleep onset latency, nocturnal awakenings, and daytime sleepiness. |

| Fetveit et al.35 | To investigate the duration of treatment effect on sleep disturbances after the termination of a two-week bright light intervention | LTCF; one nursing home; Norway |

n = 11 Residents with dementia; mean age 86.1 years, 91% female Same population as in Fetveit et al.34 study |

Pre–post test design with one group (subjects served as their own controls) | Sleep: Actigraphy (wrist) and nursing staff ratings of sleep/wakefulness disturbances measured at one-week intervals post-treatment and at 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks after treatment termination, for a total of 462 days of data | Environmental: Bright light exposure (bright light box with a light intensity of 6000–8000 lux at a distance of 60–70 cm) for two hours per day (08:00–11:00) for two weeks |

Mixed.: The variables sleep efficiency, sleep onset latency, wake after sleep onset, early morning awakening, total wake time, and time in bed remained positive for four weeks, but then gradually returned to pretreatment levels. After 16 weeks, there was no significant difference from pretreatment for any variable. Sleep onset latency remained statistically reduced up until 12 weeks post-treatment. |

| Fetveit et al.36 | To evaluate the effects of bright light therapy on daytime sleep and waking among nursing home residents | LTCF; one nursing home; Norway |

n = 11 Residents with dementia; mean age 86.1 years, 91% female. Same population as in Fetveit et al.34 study. |

Pre–post test design with one group (subjects served as their own controls) | Sleep: Actigraphy (wrist) and nursing staff ratings of average nap duration and total nap duration during the day period (rising time to 3 p.m.) measured at preintervention; at post-intervention; at one-week intervals after treatment; and at 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks after treatment termination | Environmental: Bright light exposure (bright light box with a light intensity of 6000–8000 lux at a distance of 60–70 cm) for two hours per day (between 08:00–11:00) for two weeks |

Mixed: Average nap duration and total nap duration were significantly reduced post-treatment, but returned to pretreatment levels at four weeks and remained so until 16 weeks post-treatment. |

| Feng et al.56 | To compare acupuncture and an SSRI medication on depression and insomnia in malignant tumor patients | Hospital; China |

n = 80 Adults with malignant tumor, insomnia, and depression with expected survival time greater than three months; age range: 18–75 years |

RCT; Control group received anti-depressant SSRI (Fluoxetine HCL); data collected before and after 30-day treatment | Sleep: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | Complementary health practices—Touch: Acupuncture administered once per day for 20–30 minutes for 30 days | Positive: Significant improvement in sleep vs. comparison group. |

| Fleming et al.45 | To examine associations between symptom clusters (sleep, fatigue, anxiety, and depression) following cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) compared with usual practice | Outpatient; Scotland |

n = 113 Participants with insomnia and fatigue, anxiety, or depression among a larger sample of participants who had completed anticancer therapy. Mean age: intervention group, 63; and usual care group; 58. Primarily tumors of breast, prostate, or bowel; most patients were female. |

RCT; Secondary analysis (Espie et al., 2008) | Sleep: Actigraphy (wrist) for 10 days at each of three assessments and sleep diary Other outcomes: Health-related quality of life, psychopathology, and fatigue |

Mind–body practices—CBT: Five, weekly, 50-minute, group sessions of CBT (stimulus control, sleep restriction, and cognitive therapy strategies) | Positive: Most participants at baseline had insomnia and fatigue which significantly decreased post-intervention |

| Innominato et al.64 | To assess the effect of melatonin on circadian biomarkers, sleep, and quality of life in breast cancer patients | Outpatient; Canada |

n = 32 Women with metastatic breast cancer (5–220 months post-diagnosis); median age 55.4 years; 100% female |

Pre–post design, one group; repeated measures design | Sleep: Actigraphy (wrist), diurnal patterns of serum cortisol and expression of the core clock genes PER2 and BMAL1 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Other outcomes: quality of life | Complementary health practices—Supplement: 5 mg of melatonin at bedtime for two months | Mixed: Significant improvement in a marker of objective sleep quality, sleep fragmentation and quantity, subjective sleep. Morning clock gene expression was increased following bedtime melatonin intake. Melatonin did not affect actigraphy measure of circadian rhythmicity or the diurnal cortisol pattern. |

| Karaday et al.66 | To assess the effect of baby oil on itching, sleep quality, and quality of life in patients receiving hemodialysis for end-stage renal disease | Outpatient hemodialysis units; Turkey |

n = 70 Adults with end-stage renal disease; 35 in intervention group and 35 in control group. Mean age of 54 years; 39% female. |

Pre–post design, two groups. Data collected before and 30 days after the end of the intervention. | Sleep: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index Other outcomes: Level of itching and quality of life |

Complementary health practices— Supplement (external): Application of cooled baby oil for 15–20 minutes three times per week on the day before dialysis | Positive: Significant improvement in sleep following the intervention, compared with controls |

| Kwekkeboom et al.46 | To test the feasibility and initial efficacy of a patient-controlled cognitive behavioral intervention for pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbance of advanced cancer patients | Outpatient oncology clinics; Midwest United States |

n = 27 Adults with advanced (recurrent or metastatic) colorectal, lung, prostate, or gynecological cancer receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy. 89% women; 96% Caucasian |

Pre–post test design, one group. Log of intervention use and symptoms during two-week intervention. Symptom rating immediately post intervention. | Sleep: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index Other outcomes: Pain, fatigue, and 13 common cancer-related symptoms |

Mind–Body Practices: Cognitive behavioral treatment encompassing relaxation, distraction, and imagery exercises | Neutral: No significant reductions in sleep problems or other symptoms at the end of intervention, but severity in ratings was reduced immediately after use of each strategy |

| Low et al.47 | To test the effects of emotionally expressive writing in a randomized controlled trial of metastatic breast cancer patients and to determine whether effects of the intervention varied as a function of perceived social support or time since metastatic diagnosis | Home; United States |

n = 62 Women with Stage IV breast cancer. Eighty-seven percent white women, diagnosed a mean of 7.9 years before study, and living with metastasis for a mean of 3.3 years |

Pre–post study, two groups. Data collected at baseline and three to four weeks into intervention | Sleep: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index Other outcomes: Depressive symptoms, cancer-related intrusive thoughts, negative somatic symptoms, and perceived emotional support |

Mind–body practices: Expressive therapy, four 20-minute sessions within a three-week interval delivered by phone | Negative: No significant effect on sleep among more recently diagnosed women; intervention was associated with increased sleep disturbances for women who had been diagnosed more than 4.7 years ago |

| Lund (2015)79 | To investigate the effect of melatonin on fatigue and other symptoms in patients with advanced cancer | Palliative care unit and outpatient; Denmark |

n = 50 Adults with stage IV cancer (lung, breast, GI, GYN, and others) and reported fatigue; n = 23 treatment group and n = 27 control group; 18 completed all five weeks; mean age of 65 years; 71% female |

RCT and prospective follow-up of those continuing to take melatonin | Sleep: 15-item (EORTC QLQ-C15-PAL) at the beginning and end of each treatment period (days 1, 7, 10, and 17). In part two, patients completed it at the end of each week. Other outcomes: fatigue, quality of life | Complementary health practices—Supplement: 20 mg melatonin one hour before sleep while control group received placebo | Negative: No significant improvement in insomnia, fatigue, or other symptoms |

| McCurry et al.27 | To investigate the feasibility of implementing a Sleep Education Program for improving sleep in adult family home residents with dementia determining the relative efficacy of this program compared with usual care | LTCF, Adult family home; Washington |

n = 47 Residents with comorbid dementia and sleep disturbances and 37 staff caregivers |

RCT; Data collected at baseline, one-month post-treatment, and at six-month follow-up | Sleep: Actigraphy (wrist) and Epworth Sleepiness Scale given by caregiver Other outcomes: Caregiver reports of resident daytime sleepiness, depression, and disruptive behaviors |

Sleep hygiene—Education/Information: Caregivers received a four-session sleep education trainings of nonpharmacological approaches to sleep problems and how to implement an individualized sleep plan | Positive: Intervention group had decreased frequency of nocturnal behaviors and improved actigraph-measured sleep percent and total sleep time over the six-month follow-up period compared with the control condition |

| McCurry et al.29 | To evaluate whether a comprehensive sleep education program (Nighttime Insomnia Treatment and Education for Alzheimer's Disease [NITE-AD]) could improve sleep in dementia patients living at home with their family caregivers | Home; Washington | n = 31 Community-dwelling patients with Alzheimer's Disease and their family caregivers; patient age range of 63–93 years; predominantly male and white. n = 17 intervention and n = 19 control | RCT; Data collected at baseline and at two and six months after intervention | Sleep: Actigraphy (wrist), Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and daily sleep logs. Caregiver self-reports with Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and daily sleep diary | Multicomponent —Environmental (increased daytime light), sleep hygiene (education/information), and physical activity (daily walking). Three weekly treatment sessions; each treatment component monitored at three biweekly sessions over the following six weeks. |

Positive: NITE-AD subjects' sleep improved and control subjects' sleep worsened; NITE-AD patients spent an average of 36 minutes less time awake at night (32% reduction from baseline) and had 5.3 fewer nightly awakenings than controls |

| McCurry et al.67 | To test the effects of walking, light exposure, and a combination intervention (walking, light, and sleep education) | Home; Washington | n = 132 Community-residing adults with Alzheimer's disease and sleep disorders and their in-home caregivers. Participants were mostly white, female, and around 80 years old. | RCT; four groups (three intervention, one control) | Sleep: Actigraphy (wrist) of total wake time and caregiver ratings of patient sleep quality on the Sleep Disorders Inventory | Multicomponent: Environmental (increased light exposure), physical activity (walking), and a combination. Patients randomly assigned to one of three active treatments (walking, light, or a combination of walking, light, and guided sleep education (NITE-AD) or control group. | Positive: Participant in each of the three treatment groups demonstrated similar pattern reductions in actigraph-measured total wake time compared with the control group. Patients in the walking, light, and combination groups were awake 33.1, 39.0, and 39.8 fewer minutes per night, respectively. No differences in caregiver reports of patient sleep among the groups. No differences at six-month follow-up. |

| Milbury et al.54 | To establish the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a dyadic mind–body intervention | Outpatient clinic; Houston, Texas |

n = 10 Patients with small-cell lung disease, including advanced stage three (70%), who were to receive at least five weeks of radiotherapy and their family caregivers |

Pre–post test, one group. Outcomes assessed at baseline and during the last week of radiotherapy | Sleep: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index Other outcomes: Anxiety, fatigue, health-related quality of life, and spiritual well-being |

Mind–body practices—Yoga: Attended two or three weekly sessions of couples-based Tibetan yoga that focused on breathing exercises, gentle movements, guided visualizations, and emotional connectedness. The 15-session intervention was delivered over the course of each patient's radiotherapy treatment schedule. | Positive: Nonsignificant improvement in sleep; feasible, safe, and acceptable supportive-care program |

| Milbury et al.55 | To establish the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a couple-based yoga intervention | Outpatient clinic; Houston, Texas |

n = 9 Adults with small-cell lung disease, including advanced stage three (70%), and their family caregivers; mean age of 73 year, 65% female |

Pre–post test design, one group. Outcomes assessed at baseline and following the intervention. | Sleep: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index Other outcomes: Fatigue, psychological distress, overall quality of life, spirituality, and relational closeness |

Mind–body practices—Yoga: Participants attended up to 15 sessions of couples-based Vivekananda Yoga (two to three weekly sessions of 60 minutes each over the course of the five to six weeks of radiotherapy). The program consisted of four main components: joint loosening with breath synchronization, postures/deep relaxation, breath energization, and meditation | Negative: No changes in sleep for patients although caregivers' sleep significantly improved |

| Milbury et al.48 | To examine the quality-of-life benefits of an expressive writing intervention for patients with renal cell carcinoma and identify a potential underlying mechanism of intervention efficacy | Home; United States |

n = 277 Adults with stage I to IV renal cell carcinoma (28% stage IV). Mean age of 58; 41% female |

RCT; Data collected by mail at baseline and 1, 4, and 10 months after the intervention | Sleep: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index Other outcomes: Depression, fatigue, quality of life, and intrusive thoughts |

Mind–body practices —Expressive therapy: Both groups completed four 20-minute writing assignments in their homes over a 10-day period. | Negative: No changes in sleep problems. Intervention was significantly associated with reduced cancer-related symptoms and improved physical functioning. |

| Mosher et al.49 | To determine the effect of expressive writing on well-being and sleep quality | Home; United States |

n = 86 Women with metastatic breast cancer and distress. Mean age of 59 years; 81% Caucasian |

RCT; Data collected by mail at baseline and eight weeks following the intervention | Sleep: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index Other outcomes: Fatigue, existential well-being, and psychological well-being |

Mind–body practices—Expressive therapy: Four 20-minute home-based writing sessions over four to seven weeks prompted by phone-based psychology research fellow. | Negative: No improvement in sleep or other outcomes following the intervention in either group |

| Nakamura (2013)80 | To evaluate the effects of two mind–body interventions (mind–body bridging and mindfulness meditation) on sleep disturbance and comorbid symptoms, as compared with sleep hygiene education (control) | Outpatient cancer support center; Utah |

n = 55 Adults with cancer who have completed treatment and have clinically significant self-reported sleep disturbance, randomly assigned to treatment groups. Mostly white females with breast cancer, including metastatic disease. |

RCT, three-arm parallel groups. Data collected at baseline, post-intervention, and at two-month follow-up | Sleep: Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale (self-report) Other outcomes: Life/well-being, stress, depression, mindfulness, self-compassion, emotional functioning, and affect |

Mind–body practices—Meditation (mindfulness meditation) and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (mind–body bridging) compared with an active control (sleep hygiene education). All interventions delivered in three two-hour sessions, once a week for three consecutive weeks | Positive: All groups demonstrated improved sleep following the intervention, with mean improvements in self-reported sleep scores of 22.29 mind–body bridging, 18.70 for mindfulness meditation, and 12.11 for sleep hygiene control. Compared with control, meditation and mind–body bridging continued to be effective at two-month follow-up. |

| Ouslander et al.26 | To improve nighttime sleep in nursing home patients | LTCF Nursing home; Georgia |

n = 160 Residents without the ability to walk without assistance from eight urban nursing homes (96–240 beds) |

RCT (cluster-unit crossover intervention). Data collected at baseline assessments, during immediate-intervention phase, and following the intervention | Sleep: Actigraphy (wrist) in all participants and polysomnography in a subgroup of 45 participants chosen randomly | Multicomponent—Environmental (Increased light exposure from 5 to 8 p.m. and noise abatement), Physical activity (out of bed during the day), and Sleep hygiene (keep out of bed during day and consistent bedtime routine) | Negative: No significant changes in any of the actigraphic measures of nighttime sleep; significant decrease in daytime sleep based on behavioral observations and actigraphy |

| Palesh et al.50 | To examine depression, pain, life stress, and participation in group therapy in relation to sleep disturbance | Outpatient; United States |

n = 93 Women with metastatic breast cancer who participated in a group therapy intervention |

RCT; Secondary analysis of a large intervention trial examining the effect of group therapy on symptoms. Data collected at baseline and after 4, 8, and 12 months. | Sleep: Six-item version of Structured Insomnia Interview Other outcomes: Depression, pain, and life stress | Mind–body practices—Expressive therapy: One year of weekly group therapy and educational materials (existential concerns, expression and management of disease-related emotions, increasing social support, and improving symptom control) | Negative: Primary study did not reduce sleep issues and this analysis found worsening of sleep disturbances over 12 months, which was predicted by baseline depression, pain, and life stress scores and was strongly associated with increases in depression and pain scores over that time |

| Park et al.63 | To compare the effects of aroma hand massage vs. hand massage among hospitalized hospice patients | Hospice |

n = 30 Hospice patients; 53% age 50–69 years; 41% female |

Pre–post test design (two groups). Data collected | Sleep: Verran and Snyder-Halpern Scale Other outcomes: fatigue |

Complementary Health practices—Touch + Smell: Hand massage and aromatherapy | Positive trend toward improved sleep in the aroma massage group compared with hand massage only |

| Plaskota et al.52 | To assess the effectiveness of hypnotherapy in the management of sleep disturbance in palliative care patients | Hospice palliative care unit (28 beds); England |

n = 11 Hospice patients with cancer; median age of 60 years, 73% female |

Pre–post test design, one group. Surveys at baseline, the second and last hypnotherapy sessions. Actigraphy recorded continuously for five nights prior and following intervention. | Sleep: Actigraphy (wrist) and Verran and Snyder-Halpern Scale Other outcomes: Anxiety, depression, and symptoms |

Mind–body practice—Relaxation: Four sessions of hypnotherapy, including self-hypnosis, visualization, installation of an anchor, and immune system visualization | Negative: Improvement in sleep after intervention but not significant. Found safe and acceptable. |

| Royer et al.32 | To investigate the effects of light therapy on cognition, depression, sleep, and circadian rhythms in a general, nonselected population of seniors in a long-term care facility | LTCF; Pennsylvania |

n = 28 Residents of care facility, about half with dementia; treatment group n = 15 (mean age = 84.3; 53% female), control group n = 13 (mean age = 86.4; 77% female) |

RCT; Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of all residents, regardless of diagnosis or symptoms of mood, sleep, or cognitive disorders | Sleep: Epworth Sleepiness Scale Other outcomes: Cognition, depression, and mood state |

Environmental—Increased daytime light: Both treatment and placebo groups received the light stimulus in the morning for four weeks in May and June, Monday through Friday each week for a total of 20 sessions | Negative: No significant differences between groups |

| Savard et al.42 | To assess the efficacy of individual cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in women with metastatic breast cancer, as well as the treatment's effect on immune functioning and other symptoms | Outpatient cancer clinic; Canada |

n = 37 Canadian women with metastatic breast cancer randomly assigned to treatment (n = 21; mean age of 51.5 years) or waitlist control (n = 16; mean age of 51.7 years) groups; 100% Caucasian |

RCT; Data collection at baseline, immediately after treatment and at three and six months post-treatment | Sleep: Insomnia Severity Index Other outcomes: Depression, anxiety, fatigue, quality of life, health behaviors, and several immunological measures |

Mind–body practices—cognitive behavioral therapy: Cognitive therapy was conducted individually with eight weekly sessions of 60–90 minutes to develop an optimistic but realistic attitude toward the situation. | Positive: Reduced insomnia symptoms post-intervention |

| Simeit et al.30 | To examine the effects of two multimodal psychological sleep management programs combining relaxation techniques with sleep hygiene, cognitive techniques, and stimulus control technique education on sleep and quality of life | Inpatient cancer rehabilitation clinic; Germany |

n = 229 Cancer rehabilitation clinic patients in three groups: control (n = 78; mean/SD age = 57.6/10.9), progressive muscle relaxation group (n = 80; mean/SD age = 60.2/9/2), or autogenic training (n = 71; mean age = 57.6/11.7). Most were women with breast cancer. |

Pre–post design, three groups (two interventions). Data collected four times: at start and end of rehabilitation and at six weeks and six months after treatment. | Sleep: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQ I-German version) with additional scale of daytime energy Other outcomes: Cancer quality of life |

Multicomponent —Sleep hygiene (education) and Mind–body practice (relaxation): Over three- to four-week stay, all received standard rehabilitation. Two intervention groups received three 1-hour relaxation/sleep hygiene instruction with one choosing progressive muscle relaxation and the other autogenic training | Positive: Over time, all groups showed improvement in sleep disturbance, sleep quality, and daytime energy. However, the treatment groups demonstrated a significant improvement compared with the control. There were no significant differences in outcomes between the two intervention groups. |

| Sloane et al.33 | To determine whether high-intensity ambient light in public areas of long-term care facilities will improve sleeping patterns and circadian rhythms of persons with dementia | LTCF; North Carolina and Oregon |

n = 66 Older adults with dementia recruited from a psychiatric facility and a dementia-specific residential care facility |

RCT (cluster-unit crossover intervention) | Sleep: Actigraphy (wrist) at night and during daytime activity with 48 randomly distributed one-minute observations of each participant, as alert, drowsy, or asleep. | Environmental—Increased daytime light: Ambient bright, low-glare light in dining and activity areas under four conditions: morning bright light, evening bright light, all-day bright light, and minimum standard light | Positive: Morning light and all-day light were associated with a small increase in nighttime sleep, whereas standard light and evening light with the least amount of sleep; daytime sleepiness varied by cognitive level |

| Soden et al.58 | To compare the effects of four-week courses of aromatherapy massage and massage alone on physical and psychological symptoms and on sleep quality in patients with advanced cancer | Hospice palliative care units in hospitals; England |

n = 42 Patients with advanced cancer (36% with breast cancer). Median age of 73 years, 76% female. |

RCT, three groups (two intervention and one control). Data collected at baseline and a week after the last massage, and weekly pain assessments | Sleep: Verran and Snyder-Halpern Sleep Scale. Other outcomes: Pain, anxiety, depression, and symptoms |

Complementary health practices—Combination touch (massage) and aromatherapy: All received an inert oil carrier and one group received lavender essential oil through a 30-minute back massage weekly for four weeks. | Positive: Compared with controls, sleep improved significantly in both intervention groups (massage and massage/aromatherapy), but the addition of lavender essential oil did not increase the beneficial effects of massage. |

| Swenson et al.40 | To evaluate whether an outpatient, physical therapy treatment (supervised Cancer Rehabilitation Strengthening and Conditioning program) improved conditioning level, functional status, quality of life, and symptoms, including sleep disturbances | Outpatient fitness center; Minnesota |

n = 75 Patients with cancer who were referred to the Cancer Rehabilitation Strengthening and Conditioning program by their medical oncologist and completed the study; median age = 62.6 years |

Pre–post test design, one group. Data collected at baseline, at the end of the intensive eight week program and at the end of the maintenance program. | Sleep: M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory (self report of disturbed sleep) Other outcomes: Functional status, conditioning level, symptoms, and quality of life |

Physical activity: Aerobic exercise and strength training with a physical therapist to increase endurance, strength, and flexibility and decrease oncology-related symptoms × 8-weeks in individual or group sessions plus six-month maintenance | Positive: Results following the six-month maintenance program demonstrated significant decreases in severity, relative to baseline, of symptoms, including disturbed sleep. Those who showed the worst performance at baseline showed the greatest improvement. |

| Tang et al.59 | To explore the effects of acupressure on fatigue in patients with lung cancer undergoing chemotherapy | Hospital; Taiwan |

n = 45 Adults with lung cancer (most at Stage IV) |

RCT, three groups. Two interventions (acupressure and acupressure with essential oil) and one control (sham acupressure). Data collected one day before initial chemotherapy, and on the first, third, and sixth days of chemotherapy. | Sleep: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index Other outcomes: Fatigue, functional status, anxiety, and depression |

Complementary health practices—Combination touch (massage) and aromatherapy: During chemotherapy participants e taught how to self-administer acupressure and received a handbook. Then a RA confirmed accuracy. Then participants self-administered acupressure once daily at home. One group received a 5% essential oil compound | Positive: Patients who received acupressure with essential oils and acupressure had significantly better sleep quality at the third session than the controls. Those who received acupressure with essential oils had significantly better sleep quality at the final or sixth chemotherapy than controls. |

| Tang et al.41 | To determine the effect of a home-based walking exercise program on the sleep quality and quality of life of cancer patients and to determine whether enhanced sleep quality was associated with improvement in quality of life over time | Home; Taiwan |

n = 71 Adults with cancer; mean age of 54, 55, and 66 years, respectively, for the three groups; 27% female |

RCT; Data collected at baseline) and two follow-up visits: one and two months after the initial visit in person by interview format. | Sleep: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (Taiwanese) Other outcomes: Quality of life, perceived exertion, and walking exercise log | Physical activity: eight-week walking program | Positive: Intervention group reported significant improvements in sleep quality and the mental health dimension of quality of life. Of those that exercised, enhanced sleep quality was associated with reduced bodily pain and improved quality of life. |

| Tsay and Chen57 | To test the effectiveness of acupressure on sleep quality in end-stage renal disease patients | Outpatient dialysis centers; Taiwan |

n = 98 Adults with end-stage renal disease; mean age of 55.5 years; 54.8% female |

RCT, three groups; patients randomly assigned to an acupressure group, a sham acupressure group, and a control group | Sleep: Pittsburgh sleep quality index and sleep log | Complementary health practices —Touch: Acupressure (intervention) or no acupressure (control) massage three times a week for four weeks. The acupoints were chosen on the ears, hands, and feet. | Positive: Acupressure group had a significantly greater improvement in sleep reports compared with the control group; however, there were no differences between those in the acupressure group and the sham group or the sham group and the control group). |

| Toth et al.61 | To determine the feasibility and effects of providing therapeutic massage at home for patients with metastatic cancer | Home; Massachusetts |

n = 39 Adults with metastatic cancer; mean age of 55.1 years; 82% female |

RCT, three groups (touch, no touch, and usual care). Data collected at baseline and at one week and one month following the intervention. Massage therapists documented (anxiety, pain, and alertness scale). | Sleep: Richards–Campbell scale Other outcomes: Pain, anxiety, alertness, and quality of life |

Complementary health practices —Touch: Massage treatment of three 15- to 45-minute home visits by massage therapists. The no-touch group received a sham intervention and the usual—did not receive any visits from the massage therapists. | Positive: Trend toward improvement in sleep after therapeutic massage, but not in the control groups |

| Vilela et al.53 | To measure the effects of the Nucare program, a short-term psychoeducational coping strategy intervention, on quality of life and depressive symptoms in head and neck cancer patients | Outpatient oncology clinic of hospital; Canada |

n = 101 Head and neck cancer patients; intervention group: n = 45, mean age of 57.3; control group: n = 56, mean age of 63.9; 95% Caucasian |

Pre–post, two groups. Data collected at baseline and at three to four weeks after beginning intervention. | Sleep: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life survey (single item, self-report of sleep disturbance) Other outcomes: Health-related quality of life, depression, anxiety, and fatigue | Mind–body practice —Relaxation: The Nucare program teaches coping techniques, ways of thinking, communication, use of social support, healthy lifestyle, and relaxation training. Delivered as small group, one-on-one at clinic, or one-on-one at home. | Positive trend for sleep |

| Weze et al.62 | To study the healing effects of gentle touch on physical and psychological functioning in cancer patients and to determine whether or not the treatment is safe. | Outpatient center for complementary care; England |

n = 35 Adults with cancer; median age of 57 years; 66% female |

Pre–post test design with one group. Data collected at baseline and following the final (fourth) session. | Sleep: Visual Analog Scale Other outcomes: Stress, pain, and coping ability |

Complementary health practices —Touch: Noninvasive touch on the head, chest, arms, legs, and feet for 40 minutes, plus 10-minute rest. Each received four sessions within a four- to six-week period. Treatment meant to enable self-healing mechanisms. | Positive trend for sleep |

| Young-McCaughan et al.38 | To investigate the feasibility of an exercise program to improve selected physiological and psychological parameters of health in patients with cancer | Outpatient oncology clinics at military medical centers; United States |

n = 46 Adults with cancer recruited from two military clinics; mean age of 59; approximately half female |

Pre–post test design with one group. Actigraph data collected four times, and other data collected pre- and post-intervention. | Sleep: Actigraphy (wrist) Other outcomes: Daytime activity, as well as quality of life and exercise tolerance |

Physical Activity: 12-week cardiac rehab program designed to increase exercise tolerance, modify risk factor behavior, and enhance psychological state | Negative: No significant improvement in objective measures of sleep, although participants reported significant improvement in sleep |

GI, gastrointestinal; GYN, gynecologic; LTF, long-term care facilities; RA, research assistant; RCT, randomized control trial; SD, standard deviation; SRRI, selective seratonin reuptake inhibitors.

Table 4.

Quality Appraisal of Included Articles

| Selection bias | Study design | Confounders | Blinding | Data collection method | Withdrawals and dropouts | Global rating | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alessi et al.43 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Alessi et al.28 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Birocco et al.60 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Cheville et al.39 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Dowling et al.31 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Dowling et al.37 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ducloux et al.51 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Espie et al.44 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Fetveit et al.34 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Fetveit et al.35 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Fetveit et al.36 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Feng et al.56 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Fleming et al.45 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Innominato et al.64 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Karaday et al.66 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Kwekkeboom et al.46 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Low et al.47 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Rasmussen et al.65 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| McCurry et al.27 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| McCurry et al.29 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| McCurry et al.67 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Milbury et al.54 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Milbury et al.55 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Milbury et al.48 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Mosher et al.49 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Ouslander et al.26 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Palesh et al.50 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Park et al.63 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Plaskota et al.52 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Royer et al.32 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Savard et al.42 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Simeit et al.30 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Sloane et al.33 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Soden et al.58 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Swenson et al.40 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Tang et al.59 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Tang et al.41 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Tsay and Chen57 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Toth et al.61 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Vilela et al.53 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Weze et al.62 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Young-McCaughan et al.38 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

Results

There was extensive variation among the studies in design, population, setting, measurement of sleep, inclusion of other outcomes, and interventions employed. Table 3 provides a summary of the characteristics of the 42 included studies and Table 4 provides the methodological ratings.

Types of studies, settings, and samples

Most studies (25) used a randomized control trial (RCT) design; however, six were feasibility studies. Three of the RCTs had a cluster design—either by facility or by unit. The next largest category included studies employing a pre–post design (17), with most (10) using a single group.

Intervention settings varied from community-based care (outpatient clinics: 15, home: 8), to institutional care (long-term care facilities: 11, hospital: 4, or hospice/palliative care: 4). Most studies (21) were conducted in the United States; the others were from Europe (16), Asia (5), or Canada (4). Sample sizes varied from 9 to 277 participants, with a mean of 68.9 and a median of 57.

The samples' demographics were fairly homogenous: Most participants were older (mean age ∼71.4), female (86% of studies), and Caucasian (37% of studies of those that listed participant race). Most studies (26) recruited participants who had cancer, with several focusing on those with breast (6), lung (3), or head and neck (1) cancer; the remainder included patients with various types of cancers (16). Most studies of those with cancer focuses exclusively on those with advanced or metastatic disease (19); however, some studies included participants in both advanced and nonadvanced stages of cancer (10). The other studies targeted those with dementia (11) or end-stage renal disease (2). Although we developed specific criteria defining “advanced serious illness,” it was not always possible to determine the actual stage of illness because some authors referred to “later stage,” “terminal,” or “no longer receiving treatment.”

Outcome measures

Sleep was measured in various ways, generally using valid and reliable tools. Twenty-one studies used wrist actigraphy, with one also employing polysomnography in a subset of participants.26 Among the studies using self-reporting techniques, most used valid and reliable tools such as the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (11), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (3), or the Verran and Snyder-Halpern Scale (3).

Many studies (10) included a sleep diary to document adherence to an intervention and/or record sleep quality. Others relied on symptom scales that included at least one item addressing sleep (e.g., Symptom Numeric Rating Scale). Most studies (31) included measurement of other related symptoms, such as fatigue, depression, anxiety, pain, well-being, and quality of life.

Quality assessment risk of bias in included studies

As illustrated in Table 4, the quality of the studies varied considerably, with 17 studies classified as strong, 17 as moderate, and 8 as weak. Among the last group, five of the eight studies were feasibility studies. Of the 25 studies with at least one weak rating among the 6 criteria, 12 studies were weak due to their selection bias (12) and/or controlling for potential confounders (11). Seven studies had a high risk of detection bias (no blinding or participants and/or assessors), and seven reported a high level of withdrawals and/or dropouts. Nearly all (40) used valid and reliable tools for data collection.

Study findings by category of intervention

The individual interventions are listed in Table 3. A categorization of the interventions emerged from our synthesis: sleep hygiene (1), environmental (6), physical activity (4), complementary health practices (11), and mind–body practices (13). There were a total of 21 individual interventions; 15 studies employed either a combination of interventions within a specific category of intervention (8) or a multicomponent intervention consisting of two or more categories of nonpharmacological interventions (7).

The quality assessment by category demonstrated that most (88%) of the 18 high-quality articles were evenly divided among three intervention categories: complementary, mind–body practice, and multicomponent. Most (71%) of the moderate-quality studies were evenly divided among the categories of complementary, mind–body practices, and environmental. Of the eight weak-quality studies, four were mind–body practices, two were complementary, one was physical activity, and one was environmental.

Of these 42 studies, 22 nonpharmacological interventions demonstrated a statistically significant positive impact on sleep (Table 3). These 22 individual interventions represented all categories: sleep hygiene (1), environmental (2), physical activity (3), complementary health practices (7), mind–body practices (4), and multicomponent (5). Another four studies reported a positive, although nonsignificant, trend for sleep outcomes.

Sleep hygiene (1)

Only one study evaluated sleep hygiene strategies as an individual intervention and found favorable results among adults with dementia in an assisted living facility.27 Five studies included sleep hygiene as part of a multicomponent intervention.26,28–30

Environmental (6)

Six studies, all conducted in long-term care facilities, (three RCTs and three pre–post single group design) focused on increasing light exposure,31–36 and another five studies included it as part of a multicomponent intervention.26,28,29,37 Two studies reported an increase in nighttime sleep, whereas three studies did not; whereas in a sixth study, bright light exposure during the day did not reduce daytime sleep and waking.

Physical activity (4)

One study did not find improved sleep for a rehabilitation program for those with cancer38 while the other three studies found positive results for walking, aerobic exercise, and strength training.39–42 One multicomponent study of exercise in combination with sleep hygiene also had a significant positive effect on nighttime sleep.43

Mind–body practices (13)

In these interventions, the participant takes an active role in the implementation of the strategy. Three RCTs employing cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) significantly improved sleep,42,44,45 The fourth study of CBT, without positive findings, was a one-group feasibility study.46 Another set of four studies evaluated expressive writing, and none was associated with improvement in sleep outcomes.47–50 Two small studies demonstrated the feasibility of relaxation techniques—deep breathing/somatic tension release51 and hypnotherapy52—in patients with advanced metastatic cancer. A third study testing a relaxation training found a positive trend for sleep outcomes.53 Two types of yoga, Tibetan54 and Vivekananda,55 were found to be feasible for caregiver/patient couples, but only the caregivers reported improved sleep.

Complementary health practices (11)

These practices include approaches that have developed outside of mainstream Western medicine and are administered or recommended by a practitioner, as well as dietary, nutritional, or externally applied supplements. Of the 11 studies, nearly all incorporated some type of touch therapy. Among the six RCTs, four resulted in significant positive sleep findings from the use of acupuncture,56 acupressure,57 or massage with aromatherapy.58,59 The other studies reported a nonsignificant, positive trend for better sleep outcomes among those receiving Reiki,60 massage,61 gentle touch,62 and hand massage with aromatherapy.63 However, two of these studies did not have a control group.60,62 One study of melatonin reported significant positive results among women with metastatic cancer, and another found no effect in those with various types of stage IV cancer.64,65 Finally, participants who received baby oil on their skin to reduce pruritus of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) demonstrated a significant improvement in sleep, compared with a control group.66

Multicomponent interventions (7)

Six of the seven multicomponent studies were RCTs, including five with an environmental component. Three studies demonstrated significant positive nighttime sleep outcomes when environmental components were combined with sleep hygiene28,29 and physical activity.67 Combining environment components with melatonin was associated with improved daytime sleep and activity.37 One RCT combining physical activity and sleep hygiene was positively associated with increased nighttime sleep,43 whereas another RCT that included physical activity, sleep hygiene, and an environmental component found no significant improvement in sleep.26 One study using both sleep hygiene and the mind–body practice of relaxation demonstrated positive sleep results.30

Discussion

Although the use of nonpharmacological approaches to improve sleep in adults with advanced serious illnesses is becoming more common, very little data are currently available to guide such interventions. This systematic review found only 42 studies that included or targeted participants with advanced serious illness, consistent with others who have also noted this paucity of sleep intervention studies.68

For most types of intervention, we identified only one study. Some were feasibility studies (6) and/or did not include a control/comparison group (10). The inclusion of studies of poor quality (8), as well as a study population in which the majority of the patients were either those with cancer (26) or dementia (11), limits the generalizability of the findings to those with other advanced illnesses. Also, nearly a third (10) of cancer studies included those at various stages, thus, limiting their application to those with advanced cancer.

Although most used valid and reliable measures of sleep, the variation in outcome metrics makes comparisons among studies challenging. The studies also included other types of symptoms (depression, anxiety, etc.), but did not include these based on recognized symptom clusters that include sleep.69 No studies addressed the patient's view of the intervention.

Because there were so many different individual interventions, we categorized the interventions to assist us in finding trends that may guide practice and future research. Among the six categories, two (exercise and mind–body practices) require the active involvement of the person. CBT was found in this review and others to lead to better sleep70,71 including those with cancer,72 whereas relaxation and yoga had mixed results. Despite the effectiveness of many of these interventions in other, less ill, populations,71 those within these two categories of “active” interventions seem to have limited applicability to those in the later stages of advanced serious illness. Depending on the type and stage of a patient's serious illness, physical and/or cognitive barriers may inhibit these activities.

The other four categories included mostly passive interventions administered by staff or family caregivers. All 11 studies employing environmental (light) interventions were all conducted in long-term care facilities among those with dementia. The rest–activity rhythm disturbances in dementia may have influenced the mixed results (positive for two of six single environmental interventions and three of five multicomponent interventions). It is difficult to compare results among studies because the light intervention varied and thus, it remains unclear which specific light delivery strategy is optimal.37,23

Environmental interventions seem to be the easiest interventions to implement in patients with advanced serious illness because implementation does not require much effort on the part of the patient. Yet these interventions may require alterations to the current physical environment or the development of custom products or systems by experts.73 Changing practices in institutional settings is not a simple process as quality improvement studies have demonstrated the need for consistent staff feedback to sustain practice changes.74,75 Making environmental changes in the home care environment is also difficult since it may disrupt other family routines.

This is also true for sleep hygiene practices. Depending on the functional status of the person with advanced serious illness, staff or family caregivers may be required to implement the intervention. The only study utilizing sleep hygiene education as a single intervention was a training program for staff. Consistent with national guidelines,69 sleep hygiene was combined with other interventions in five studies in which four demonstrated positive results. Other single interventions in this review may have benefitted from including sleep hygiene, particularly because it is considered a standard treatment for insomnia.18 Moreover, sleep outcomes may have been affected because some studies did not control for several of the most critical environmental components of sleep hygiene (the noise, light, and temperature levels of the ambient environment).

Complementary health practices generally do not require active patient participation, and the results of the studies were mostly positive, suggesting that complementary health practices may be the most promising individual category of nonpharmacological intervention in adults with advanced illnesses. All of the studies in this category were implemented with cancer patients. These interventions may effectively promote sleep by encouraging relaxation and/or reducing negative emotions that may interfere with sleep.76

Although multicomponent interventions are recommended over single treatments,1 such interventions made up only 7 of the 42 studies in this review. Given the likely multifactorial etiology of sleep disturbance, it would make sense that these interventions would be the most effective. Light therapy and sleep hygiene were the most common elements in the multicomponent studies reporting positive sleep outcomes.

In conclusion, despite the limitations, this review provides preliminary support for passive interventions (environmental, complementary, and multicomponent) because these resulted in the most significantly positive sleep outcomes. However, environmental (light) interventions were only tested in patients with dementia, whereas complementary interventions were only tested in those with cancer (Table 5). Neither were tested in patients with ESRD. Interventions in the physical activity and mind–body practices categories differed considerably and did not have enough evidence to support their use.

Table 5.

Intervention Type and Positive Finding By Diagnosis

| Intervention type | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Sleep hygiene | Environmental | Physical activity | Mind–body | Complementary | Multicomponent | Totals |

| Cancer—breast | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2/5 | 0/1 | 0 | 2/6 |

| Cancer—lung | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/2 | 1/1 | 0 | 2/3 |

| Cancer—other/mixed | 0 | 0 | 3/4 | 3/7 | 2/5 | 1/1 | 9/17 |

| Dementia | 1/1 | 2/6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3/4 | 6/11 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2/3 | 1/2 | 3/5 |

| Totals | 1/1 | 2/6 | 3/4 | 6/14 | 5/10 | 5/7 | 42 |

Future research

The general low quality of the evidence in this review points to the need for more studies with adequate sample sizes and standardized methodology to determine statistical significance. Many of the research studies identified in this review were feasibility studies showing promising results that require more rigorous testing before widespread adoption. Additional work is needed to address clinical relevance and which interventions can be reasonably applied in all types of palliative care settings—both institutional and community based. Given the high refusal and attrition rate found in several studies, the treatment preferences of those with advanced serious illness need to be a priority in future studies. Because the functional level of those with advanced serious illness may also affect this, more research is needed to evaluate passive interventions (environmental, complementary, and multicomponent employing these as well as sleep hygiene strategies). Interventions that improved sleep in one population (such as environmental interventions in those with dementia and complementary health practices in those with cancer) should be tested in other populations. Clearly more research is also needed among those with ESRD.

Some negative results may be a result of the researchers, including all persons with a particular advanced serious illness instead of targeting those with a known sleep problem.33–36 Thus, future research should only include those with sleep disturbance, preferably documented with objective measurements.

Future studies should consider how these interventions are delivered.77 There has been considerable research regarding bright light therapy; however, the expense or application of light boxes and overhead lighting make many such techniques impractical. Lamps that emit the appropriate spectrum of light to affect circadian rhythms should be tested in the home environment in those with advanced serious illness.78

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the students who assisted with the scoping review (Kaye Estioco, RN, MS, Hunter College) and the initial review of articles (Hessam Sadatsafavi, Cornell University; Elvy Barroso, MS, RN, City University of New York [CUNY] Graduate Center; and Mimi Lim, MS, RN, CUNY Graduate Center). Special thanks to Paul Eshelman, MFA, Cornell University, for his substantive input to the overall design of the grants supporting this work and Melissa Kuhnell for article preparation. The authors appreciate the support of librarians Ajatshatru Pathak, MLS, MPH (Hunter College) and Kevin Pain (Weill Cornell Medicine) for assistance with the revision of the article.

The study was funded by the United States Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture's Federal Capacity Fund (Smith Lever) for outreach and cooperative extension of research in land grant universities, as well as by the Professional Staff Congress at the City University of New York, the Cornell Institute for Healthy Futures, and the College of Human Ecology's Building Faculty Connections Program. The study was seeded by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30AG022845. The project also received support from the Lawrence and Rebecca Stern Family Foundation through the Translational Research Institute for Pain in Later Life. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Fung CH, Vitiello MV, Alessi CA, et al. : Report and research agenda of the American Geriatrics Society and National Institute on Aging bedside-to-bench conference on sleep, circadian rhythms, and aging: New avenues for improving brain health, physical health, and functioning. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:238–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Renom-Guiteras A, Planas J, Farriols C, et al. : Insomnia among patients with advanced disease during admission in a palliative care unit: A prospective observational study on its frequency and association with psychological, physical and environmental factors. BMC Palliat Care 2014;13:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis MP, Goforth HW: Long-term and short-term effects of insomnia in cancer and effective interventions. Cancer J 2014;20:330–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elias RM, Chan CT, Bradley TD: Altered sleep structure in patients with end-stage renal disease. Sleep Med 2016;20:67–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Budhiraja R, Siddiqi TA, Quan SF: Sleep disorders in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Etiology, impact, and management. J Clin Sleep Med 2015;11:259–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Culebras A: Sleep, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Disease. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma K, Kass DA: Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Mechanisms, clinical features, and therapies. Circ Res 2014;115:79–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cipriani G, Lucetti C, Danti S, Nuti A: Sleep disturbances and dementia. Psychogeriatrics 2015;15:65–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pearse SG, Cowie MR: Sleep-disordered breathing in heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:353–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis MP, Goforth H: Fighting insomnia and battling lethargy: The yin and yang of palliative care. Curr Oncol Rep 2014;16:377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis MP, Goforth HW: Long-term and short-term effects of insomnia in cancer and effective interventions. Cancer J 2014;20:330–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savard J, Ivers H, Savard MH, Morin CM: Cancer treatments and their side effects are associated with aggravation of insomnia: Results of a longitudinal study. Cancer 2015;121:1703–1711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoder JC, Staisiunas PG, Meltzer DO, et al. : Noise and sleep among adult medical inpatients: Far from a quiet night. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:68–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schorek JL, Ford J, Conway EL, et al. : Review of safety and efficacy of sleep medicines in older adults. Clin Ther 2016; 38:2340–2372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel: Updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:2227–2246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Guideline Clearinghouse: Clinical Guideline for the Treatment of Primary Insomnia in Middle-Aged and Older Adults. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea MA, et al. : Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2016;165:125–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Irish LA, Kline CE, Gunn HE, et al. : The role of sleep hygiene in promoting public health: A review of empirical evidence. Sleep Med Rev 2015;22:23–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kemple M, O'Toole S, O'Toole C: Sleep quality in patients with chronic illness. J Clin Nurs 2016;25:3363–3372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howell D, Oliver TK, Keller-Olaman S, Davidson JR: Sleep disturbance in adults with cancer: A systematic review of evidence for best practices in assessment and management for clinical practice. Ann Oncol 2013;25:791–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oncology Nursing Society: “Putting Evidence into Practice” https://ons.org/practice-resources/pep (last accessed January5, 2018)

- 22.Trauer JM, Qian MY, Doyle JS, et al. : Cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:191–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Maanen A, Meijer AM, van der Heijden KB, Oort FJ: The effects of light therapy on sleep problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 2016;29:52–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiao W, Chow KM, So WKW, et al. : The effectiveness of psychoeducational intervention on managing symptom clusters in patients with cancer: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Cancer Nurs 2016;39:279–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools: Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. Hamilton, ON: McMaster University; www.nccmt.ca/resources/search/14 (Last accessed April13, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ouslander JG, Connell BR, Bliwise DL, et al. : A nonpharmacological intervention to improve sleep in nursing home patients: Results of a controlled clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:38–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCurry SM, LaFazia DM, Pike KC, et al. : Development and evaluation of a sleep education program for older adults with dementia living in adult family homes. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012;20:494–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alessi CA, Martin JL, Webber AP, et al. : Randomized, controlled trial of a nonpharmacological intervention to improve abnormal sleep/wake patterns in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:803–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCurry SM, Gibbons LE, Logsdon RG, et al. : Nighttime insomnia treatment and education for Alzheimer's disease: A randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:793–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simeit R, Deck R, Conta-Marx B: Sleep management training for cancer patients with insomnia. Support Care Cancer 2004;12:176–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dowling GA, Hubbard EM, Mastick J, et al. : Effect of morning bright light treatment for rest–activity disruption in institutionalized patients with severe Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr 2005;17:221–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Royer M, Ballentine NH, Eslinger PJ, et al. : Light therapy for seniors in long term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012;13:100–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sloane PD, Williams CS, Mitchell CM, et al. : High‐intensity environmental light in dementia: Effect on sleep and activity. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:1524–1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fetveit A, Skjerve A, Bjorvatn B: Bright light treatment improves sleep in 35. Institutionalized elderly—an open trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003;18:520–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]