Abstract

Background: Timeliness is one of the fundamental yet understudied quality metrics of cancer care. Little is known about cancer treatment delay among adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer patients. This study assessed cancer treatment delay, with a specific focus on facility transfer and diagnosis/treatment interval.

Methods: Based on MultiCare Health System's (MHS's) institutional cancer registry data of AYA patients diagnosed during 2006–2015, this study analyzed patient demographics, insurance, clinical characteristics, and time of diagnosis and treatment initiation. Chi-squared tests, cumulative hazard estimates, and Cox proportional regression were used for univariable analysis. Multivariate regression models were used to test the association between care transfer and days of interval or prolonged delay, controlling for baseline parameters.

Results: Of 840 analytic AYA cases identified, 457 (54.5%) were both diagnosed and treated within MHS. A total of 45.5% were either diagnosed or treated elsewhere. Mean and median intervals for treatment initiation were 27.03 (95% CI = 21.94–33.14) and 8.00 days (95% CI = 5.00–11.00), respectively, with significant differences between patients with and without facility transfer. Transfer was significantly correlated with longer length of diagnosis-to-treatment interval. Treatment delay, ≥1 week, was associated with transfer, female sex, older age, no surgery involvement, and more treatment modalities. Treatment delay, ≥4 weeks, was associated with transfer, female sex, no insurance, and no surgery involvement.

Conclusion: In a community care setting, the diagnosis-to-treatment interval is significantly longer for transferred AYA cancer patients than for patients without a transfer. Future studies are warranted to explore the prognostic implications and the reasons for delays within specific cancer types.

Keywords: adolescent and young adult, cancer treatment delay, cancer patient pathway, community cancer care, access to care

Introduction

The National Academy of Medicine identifies six domains of health care quality, including timeliness.1,2 In cancer research, there is a relative paucity of studies on “timeliness” compared with other domains. Early detection and prompt treatment improve the odds of cancer care before metastatic spread, enhancing prospects for long-term survival.3–5

Previous reports on cancer care delay have examined the impact of patients',6 providers', and health system failures to efficiently respond to signs of cancer and confirm the diagnosis.7 Studies on cancer treatment delay have often focused on single cancer types, most often among elderly adults.8,9 Very few have focused on malignancies of young people, or mixtures of primary tumor locations.

Adolescents and young adults (AYA), ages 15–39 years at the time of cancer diagnosis, are a unique subset of cancer patients. In the United States (U.S.), cancer is the leading cause of disease-related death among AYAs.10 Over the past 30 years, although under debate, particularly with concerns in HIV/AIDS-related cancers and gender-specific statistics,11 survival improvement in AYAs has been less marked compared with children and older adults with cancer.12–16 AYAs have not been appreciated as a distinct population until fairly recently. AYA cancer patients may fall into a “no man's land”17,18 between pediatric and adult oncology, being treated by either pediatric or adult providers with little expertise in their specific needs.19–21

Cancer care delay (or “cancer delay”) among AYAs is a multifaceted and understudied challenge to the delivery of high-quality care.22 In the U.S., only a small minority of AYA cancer patients are treated within specific AYA-focused programs. Poor communication and lack of collaboration between medical services are a potential source of both inappropriate therapeutic strategies and treatment delay in AYAs.23

In general, cancer delay can be termed as “lagtime,”24 “wait-time,”25 or “prolonged care interval,”26 and parsed into diagnostic delay and treatment delay. Diagnostic delay has been categorized in the literature under tags such as “primary care delay,” “referral delay,” “investigation delay,” and “secondary care/specialist delay.” Researchers in the field commonly attribute diagnostic delay to either the provider's diagnostic acumen or to the efficiency of intake processes, including waits surrounding diagnosis, consultation, and treatment initiation, or triage for diagnostic testing.27 However, patient characteristics, perceptions, and behaviors also could play important roles in diagnostic delay especially before first contact with the health care system.28,29

Treatment delay has been conceptualized as primarily influenced by provider characteristics and system failures, such as misdiagnosis and wait lists.30 However, treatment delay may actually be strongly impacted by intrinsic patient characteristics as well as behaviors shaped by interactions with the medical system. In fact, patient-related treatment delays have been shown to exist in a socialized health care system with universal access and a single payer, where health system factors are somehow controlled.31 Thus, the allocation of risk factors into specific domains may have overlooked the fact that cancer delays cannot be fully attributed to any single stakeholder, but instead are the result of the complex interplay of multiple factors.

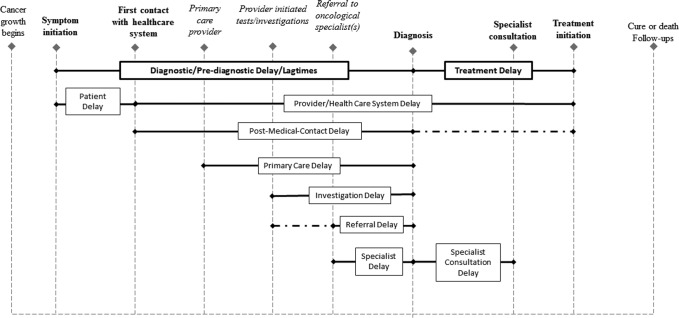

Four critical events are involved in the analysis of cancer delay: (1) symptom recognition, (2) first presentation to a health care professional, (3) diagnosis, and (4) treatment initiation (Fig. 1).9 Along this pathway, AYAs may experience added complexity as they can enter the health care system through contact with either pediatric or adult medical providers, depending mainly on the first contact provider's referral patterns.32 Unlike children or older adults who stay within pediatric or adult medical oncological care after diagnosis, AYAs are more likely to be referred back and forth between the two, which often requires changing care facilities. Difficulties in access to care, that is, geographically and financially feasible and clinically suitable before and after diagnosis, further challenge AYAs. The particular transition of main cancer-relevant care, regardless of reasons, among different health service systems or care facilities, is considered “cancer care transfer” (referred as “transfer,” “facility transfer,” or “patient transfer” below). Due to the transitional nature and perceptions of invulnerability, facility transfers are common in AYAs. Facility transfers in AYAs may generate a variety of impediments to patients' transitions in medical management and may pose distinctive risks in outcomes. Transfer reflects patients' most important disease-related behaviors regarding where to seek care, and decisions about changes in cancer care utilization may impact the diagnosis/treatment interval. However, few prior studies have investigated the influence of patient transfer on cancer delays.

FIG. 1.

Definition of cancer intervals and cancer delays in the literature. Bolded events represent those most critical to delay definitions; italicized events may or may not occur during patients' cancer care journeys in the U.S.; dashes represent an extension to the definition of postmedical contact delay.

In the U.S., the majority of cancer patients are treated at community cancer care facilities,33 with comparatively smaller numbers receiving care in academic cancer centers. The aim of this study is to describe treatment delay in AYAs in a community care setting. By using transfer as the major proxy for patient pathway and care dynamics, we aim to understand how transfer impacts treatment delay, which is measured by the diagnosis/treatment interval, among AYAs.

Methods

Study design and data

This is a retrospective study using data from an internal cancer registry platform (MultiCare cancer registry), capturing AYA cancer patients (ages 15–39 years at diagnosis) served by the MultiCare Health System (MHS) with a primary cancer diagnosis between January 1, 2006, and June 30, 2015. MHS is a member of a network of community hospitals and clinics in Washington State. MHS registers and reports cancer data in accordance with Washington Administrative Code 246-102, which establishes rules for reporting cancer cases to the Washington State Department of Health (WADOH). All data, including those outside of MHS, were audited, amended, incorporated, and confirmed by the WADOH. The study was considered to be a retrospective data review and thus was approved under the exempt research category by the MHS IRB. All data were deidentified and anonymous.

Invasive cancers were collected regardless of vital status at the time of data retrieval. Primary benign brain tumors (pituitary adenomas and meningiomas) were also included because of their potential for clinically significant adverse effects requiring therapy. Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast was also included. Neoplasms of uncertain behavior, in situ carcinomas of uterine cervix, or basal-cell and squamous-cell carcinomas of the skin were not included in this analysis. Case definition of this study considered the primary “Case-finding Code List for Reportable Neoplasms” defined by the National Cancer Institute of U.S.34 as well as by the National Cancer Database (NCDB).35

Initially, we included patients who had any cancer-relevant clinical encounter at any MHS facility, including diagnosis, supportive care, and/or part or all of the recommended courses of cancer-directed therapy. The final analysis database, however, excluded cases that only used supportive care in MHS facilities.

Treatment delay

The time interval between “Time of Diagnosis (TDx)” and “Time of Treatment Initiation (TRx)” was used to measure treatment interval in this study. Data were collected for both time points even if some of the patient's care was delivered at a non-MultiCare site.

TDx, as the start point of time intervals, used “Date of Initial Diagnosis,”36 defined as “the earliest date this primary cancer is diagnosed clinically; or is diagnosed microscopically by a recognized medical practitioner, regardless of whether the clinical diagnosis was made.” This excluded dates of suspicious cytology before definitive cancer diagnosis.34

TRx used “Date of First Course of Treatment” defined as “the earliest date of first surgical procedure with treatment purposes, date radiation started, date systemic therapy started, or date other treatment started” (SEER Reporting Guidelines).37,38 Only cancer-directed treatment was considered in measurement and calculation.

Treatment delays are measured by longer days of interval between TDx and TRx (“Dx-Rx interval”), or by cutoffs at 1 and 4 weeks for the intervals. We used these two benchmarks based on the descriptive results of Dx-Rx median (8 days) and mean (27 days) from this data set.

Patient pathway and transfer

“Patient pathway” is a theoretical term that describes the course of patients' interactions with the health care system. In this study, patient pathway is reflected by the parameter “care transfer” derived from the original “class of case” variable, a data item that is of great importance to a hospital registry,39 which divides the care-seeking pathways into four major pathways/routes:

-

1.

Diagnosed and started first course of cancer treatment within MHS.

-

2.

Diagnosed outside of MHS but received the first course of treatment at any MHS facility.

-

3.

Diagnosed at an MHS facility, but received first cancer-relevant treatment outside of MHS.

-

4.

Neither diagnosed nor initiated treatment at MHS, but seen at MHS for supportive care services only.

Categories 1 through 3 are defined as analytic cases. Nonanalytic category 4 was excluded. Routes 2 and 3 were further combined as “transferred patients” and 1 was classified as “nontransferred patients.” Furthermore, route 2 was defined as “transferred-in” and 3 as “transferred-out” patients, within the transferred patient group.

Other variables

We captured patients' sociodemographic characteristics, insurance status (two derived dichotomized parameters were formed: no insurance vs. any insurance; Medicaid vs. no Medicaid), and cancer clinical features (primary site group and comorbidities at diagnosis). We also involved first-course treatment type, particularly whether surgery was involved, and the number of different treatment modalities utilized.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to examine distributions of sociodemographic characteristics, health insurance status, clinical features of cancer, pathways, and Dx-Rx intervals. Chi-square tests were performed to understand benchmarked Dx-Rx interval discrepancies (≥1 and ≥4 weeks) among patient subgroups defined by (1) patient transfer; (2) patients' baseline sociodemographics; (3) health insurance; and (4) comorbidities.

The analysis of patient pathways compared “nontransferred” to “transferred” patients. A dichotomized “common cancer type” parameter was derived based on the presence or absence of 1 of the 10 most common cancers in the data: breast, thyroid, testis, brain, Hodgkin's disease, other endocrine, cervix-uteri, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, melanoma, and colorectal/anal cancer. This dichotomization was based on the assumption that less common types may require more specific care due to their rarity or lack of local care expertise for such types of AYA cancer, thus making transfer more likely. We also accounted for the number of comorbidities, number of cancer treatment modalities, and whether initial cancer therapy involved a surgical procedure in the models.

Time-to-event (TTE) analysis (or survival analysis) was adopted using TDx and TRx. The censoring was set on August 12, 2016 (TCensor). Univariable TTE in this study included three parts:

-

(1)

Kaplan/Meier log survival functions were used to analyze the impact of different patient pathways on the Dx-Rx interval. The “survival” function was used to measure not survival, but continued wait to begin cancer treatment (the reverse would be the treatment initiation). We will subsequently refer to this use of the survival as “wait-time.” Shorter “wait-time” represents a smaller Dx-Rx interval and thus less delay. This part included cumulative survival function scores on linear and logarithmic scales.

-

(2)

Nelson/Aalen cumulative hazard estimates were generated to examine factors correlated with prolonged wait-time, including transfer, race, health insurance, and surgery involvement in the treatment plan.

-

(3)

Cox proportional hazard models40,41 were adopted to evaluate the significance of differences in Dx-Rx interval between patients from different subgroups, including variation among patient pathways.

In these semiparametric models, the hazard function assesses not the instantaneous risk of death (shorter survival, a negative outcome) at TCensor, as it normally does in cancer survival studies, but the risk of shorter Dx-Rx interval (a positive outcome). Higher Nelson/Aalen cumulative hazard estimates or lower Kaplan/Meier scores each reflect a smaller chance of treatment delay. Hazard ratios <1 in the Cox proportional hazard regression indicate greater likelihood of a longer Dx-Rx interval.

In addition, we used bootstrapped quantile regression42 and logistic regression models to calculate average marginal effects of Dx-Rx delay on the probability of selected patient pathways, adjusting for other baseline factors. For the quantile regression, days of Dx-Rx intervals were used as the dependant variable. For logistic regression, we used ≥1 and ≥4 weeks as the cutoff benchmarks for treatment delay. These two benchmarks were set as proxies of prolonged wait based on descriptive median and mean for the Dx-Rx intervals. Stata 14 (StataCorp. 2015. College Station, TX) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Study population

During the study period, MHS captured 840 new analytic AYA cancer cases. The 10 most common cancer sites were breast (in females 21.7%), thyroid (12.0%), testis (in males 23.2%), brain (8.2%), Hodgkin's disease (6.8%), other endocrine (6.3%), cervix-uteri (in females 7.4%), melanoma (4.6%), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (4.6%), and colon/rectum/rectosigmoid (4.3%). These 10 types account for 73.7% of all the cases. The range of cancers overall and the ranking for individual cancer types were consistent with that of AYA cancer nationally.21

There were 457 (54.5%) nontransferred and 383 (45.5%) transferred patients, including 36.1% of transferred-in AYAs, and 9.4% of transferred-out cases.

Insurance coverage between transferred (80.5%) and nontransferred patients (75.7%) was not significantly different (χ2 = 3.443, p = 0.179). The difference in the proportion of “Medicaid-only” patients between the two groups (29.7% vs. 23.4%) was also not significant (χ2 = 5.038, p = 0.081).

Transferred patients were older than nontransferred patients with more patients between 30 and 39 years old (yo) (65.3% vs. 55.8%) and fewer between 10 and 19 yo (9.5% vs. 15.5%) (χ2 = 9.943, p = 0.007). The percent of students in the two groups was comparable (9.2% vs. 13.8%, χ2 = 5.0813, p = 0.079) as was the sex ratio (male 37.5% vs. 40.3%, χ2 = 3.242, p = 0.072). A comparable percentage of patients had one or more comorbidities (52.0% vs. 58.3%, χ2 = 5.464, p = 0.141) and were white (81.8% vs. 77.0%, χ2=2.925, p = 0.087) between transferred and nontransferred groups. The two groups did not differ in proportion of common cancer types (χ2=2.918, p = 0.088), nor having surgery for treatment (73.8% vs. 67.5, χ2=3.838, p = 0.060).

Dx-Rx intervals

Dx-Rx intervals are presented and tested by patient characteristics (Table 1; Fig. 2). Univariable analysis on Dx-Rx intervals ≥1 and ≥4 weeks showed that multiple factors significantly impacted the likelihood of having a prolonged Dx-Rx interval, at both thresholds, including age group, sex, student status at diagnosis, no health insurance, patient pathway, and number of comorbidities. Medicaid and race did not predict a prolonged Dx-Rx interval in the univariable analysis.

Table 1.

Description of Demographic, Health Insurance, and Clinical Characteristics of the Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients, and Univariable Analysis on Dx-Rx Intervals by Patient Characteristics

| Variable | Counts (%) | Dx-Rx interval (days) mean, median | Delay ≥1 and ≥4 weeks (%) | χ2(for Dx-Rx intervals at 1 and 4 weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 20.384**; 10.745** | |||

| All age groups | Mean ± SD | |||

| 30.17 ± 7.287 | 27.00, 8.00 | 48.7, 25.2 | ||

| 15–19 | 107 (12.7) | 22.55, 4.00 | 36.4, 15.0 | |

| 20–29 | 227 (27.0) | 22.78, 3.00 | 40.5, 22.0 | |

| 30–39 | 506 (60.2) | 29.80, 12.00 | 54.9, 28.9 | |

| Sex | 15.236**; 9.213** | |||

| F | 525 (62.5) | 26.69,13.00 | 53.9, 28.8 | |

| M | 315 (37.5) | 26.68,4.00 | 40.0, 19.4 | |

| Occupation | 5.252*;6.956** | |||

| Student | 99 (11.8) | 23.63, 5.00 | 37.8, 14.3 | |

| Other | 741 (88.2) | 27.07, 8.00 | 50.1, 26.6 | |

| Race | 1.537; 1.423 | |||

| White | 174 (20.7) | 24.94, 7.00 | 47.6, 24.3 | |

| Other | 666 (79.3) | 34.75, 12.00 | 52.9, 28.7 | |

| Health insurance | ||||

| Medicaid | 221 (26.3) | 22.65, 3.00 | 44.5, 25.5 | 0.158; 0.015 |

| No Medicaid | 28.15, 9.00 | 50.1, 25.0 | ||

| No insurance | 185 (22.0) | 47.77, 18.00 | 57.1, 32.6 | 6.714*; 6.967** |

| Any insurance | 21.24, 5.00 | 46.3, 23.1 | ||

| Patient pathway | 85.005**; 52.269** | |||

| Dx/Rx at MHS | 458 (54.5) | 16.37, 1.00 | 34.1, 15.5 | |

| Dx out of MHS | 303 (36.1) | 32.23, 20.50 | 65.9, 36.8 | |

| Rx out of MHS | 79 (9.4) | 75.87, 22.00 | 66.7, 38.5 | |

| No. of comorbidities | 12.874**; 12.208** | |||

| 0 | 376 (44.7) | 26.17, 6.00 | 45.3, 21.1 | |

| 1 | 145 (17.3) | 39.44, 11.00 | 55.2, 35.2 | |

| 2 | 110 (13.1) | 16.64, 1.00 | 38.2, 21.8 | |

| 3 or more | 209 (24.9) | 23.81, 12.50 | 55.5, 27.3 | |

p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

MHS, MultiCare Health System.

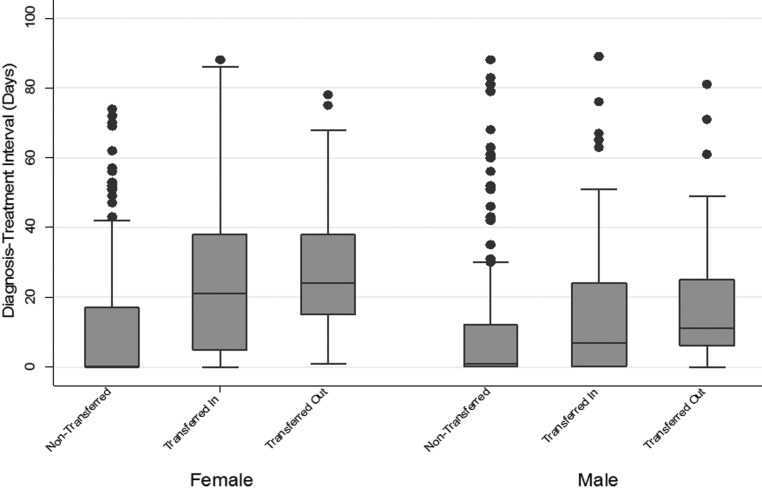

FIG. 2.

Boxplot of diagnosis/treatment intervals (days) by gender and patient pathways for patients whose time interval to start therapy was 90 days or less.

Nontransferred AYA patients had the shortest Dx-Rx interval, followed by “transferred-in” patients. “Transferred-out” AYAs had the longest Dx-Rx delay.

Univariable analyses

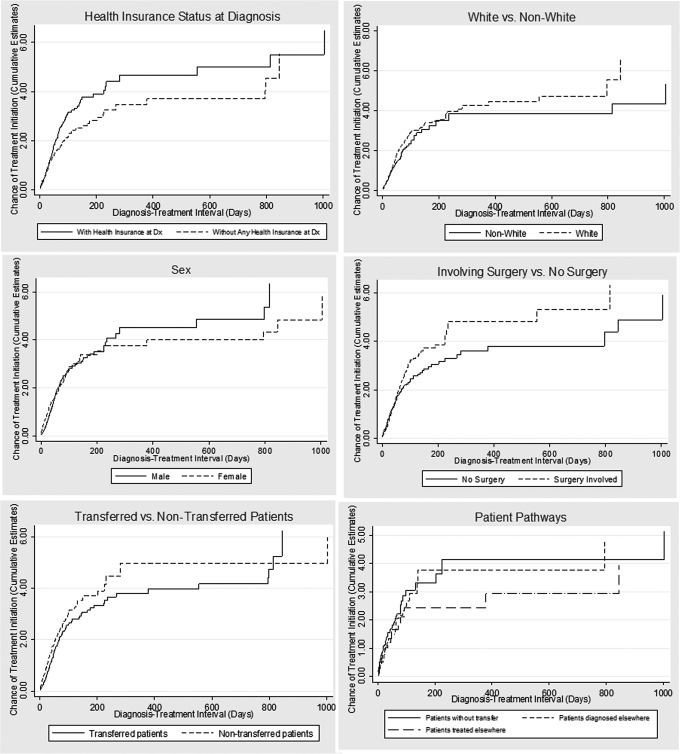

Nelson/Aalen cumulative hazard estimates and Kaplan/Meier functions strongly pointed to the association of total Dx-Rx delays and certain factors, including care transfer, the category 3 pathway, lack of insurance, non-white race, female, and no-surgery involvement (Figs. 3–4).

FIG. 3.

Nelson/Aalen cumulative estimates on chances of treatment initiation (higher score is better) by patient characteristics, health insurance status, treatment feature, and cancer care pathways. Note: Higher estimated scores represent a better cumulative chance of timely cancer treatment initiation within a given wait interval.

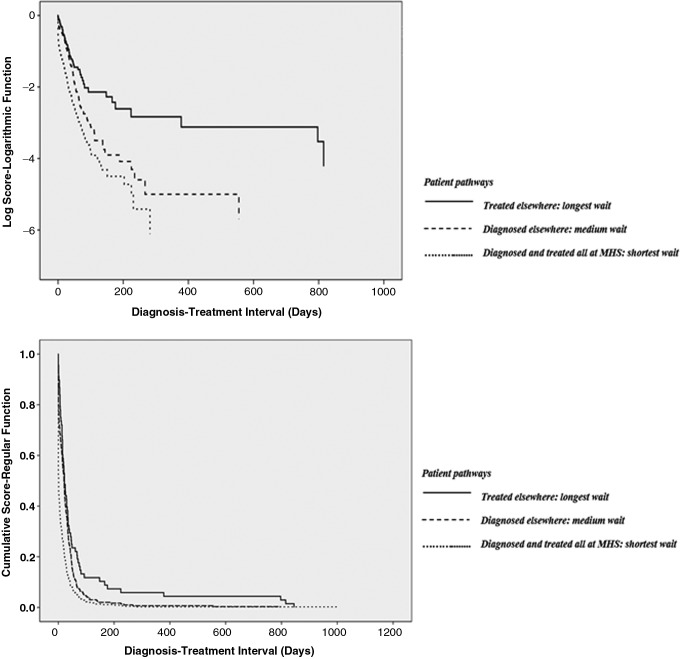

FIG. 4.

Kaplan/Meier logarithmic and regular function curves based on diagnosis/treatment intervals, by patient pathways.

Cox regression estimates (Table 2) showed that AYA cancer patients transferred in or out had longer Dx-Rx intervals, and were on average 27% more likely to see a treatment delay compared with nontransferred patients. Females were 17% more likely than male patients to have prolonged Dx-Rx intervals. Patients older than 24 years at diagnosis were 28%–38% more likely to have prolonged Dx-Rx compared with patients younger than 20 years.

Table 2.

Univariable Cox Proportional Hazard Model for Dx-Rx Intervals

| Risk factors | Hazard ratio | Standard errors | 95% CI, p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient pathway | |||

| Dx/Rx both at MHSa | |||

| Dx out of MHS | 0.770 | 0.7137 | 0.642–0.923, 0.005 |

| Rx out of MHS | 0.629 | 0.0900 | 0.475–0.832, 0.001 |

| Any type of transfer | 0.730 | 0.0639 | 0.615–0.867, 0.000 |

| Sex | |||

| Malea | |||

| Female | 0.831 | 0.0750 | 0.697–0.992, 0.041 |

| Race | |||

| Non-white | 0.864 | 0.0902 | 0.704–1.060, 0.162 |

| Whitea | |||

| Age group (years) | |||

| <20a | |||

| 20–24 | 0.766 | 0.1442 | 0.530–1.108, 0.157 |

| 25–29 | 0.682 | 0.1103 | 0.496–0.936, 0.018 |

| 30–34 | 0.724 | 0.1063 | 0.543–0.966, 0.028 |

| 35–39 | 0.620 | 0.0857 | 0.473–0.813, 0.001 |

| Health insurance | |||

| No insurance (any insurancea) | 0.852 | 0.0835 | 0.703–1.033, 0.102 |

| Medicaid (othera) | 0.835 | 0.0874 | 0.680–1.024, 0.085 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| 0 | 0.959 | 0.1022 | 0.778–1.182, 0.697 |

| 1 | 0.703 | 0.1932 | 0.841–1.211, 0.108 |

| 2 | 0.979 | 0.1523 | 0.721–1.328, 0.892 |

| 3 or morea | |||

| Dx year | |||

| 2006–2009 | 0.863 | 0.0756 | 0.727–1.025, 0.093 |

| 2010–2015a | |||

| No. of cancer treatment modalities | |||

| 1 | 1.454 | 0.8464 | 0.464–4.551, 0.520 |

| 2 | 2.068 | 1.2076 | 0.658–6.495, 0.213 |

| 3 | 2.038 | 1.1952 | 0.646–6.433, 0.225 |

| 4 | 1.662 | 1.0024 | 0.510–5.421, 0.399 |

| 5a | |||

Reference group.

The bold italic parts show the statistically significant outcomes by risk factors.

Multivariable analyses

Because the Dx-Rx interval showed a skewed distribution, bootstrapped quantile regression instead of linear regression was adopted. This model indicated that a longer Dx-Rx interval was associated with transfer (either in or out), uninsured status, and older age. Shorter Dx-Rx interval was associated with surgery involvement.

In logistic regression, male sex and surgical treatment were associated with less likelihood of wait ≥1 week. More treatment modalities, older age, and transfer were associated with treatment delay of more than 1 week. Male sex and surgical treatment were associated with lower likelihood of a wait ≥4 weeks. Transfer and lack of insurance were associated with a wait ≥4 weeks (Tables 3–4).

Table 3.

Bootstrapped Quantile Regression Model for Dx-Rx Interval (Days)

| Risk factorsa | Coefficient | Standard errors | 95% CI | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (femaleb) | −1.50 | 1.41 | −4.26 to 1.26 | −1.07 | 0.29 |

| Age group (years) | |||||

| <20b | |||||

| 20–24 | 2.38 | 2.39 | −1.21 to 5.93 | 1.30 | 0.19 |

| 25–29 | 1.87 | 1.83 | −1.51 to 5.69 | 1.14 | 0.25 |

| 30–34 | 4.32 | 1.83 | 0.71 to 7.97 | 2.35 | 0.02 |

| 35–39 | 4.12 | 1.76 | 0.65 to 7.64 | 2.32 | 0.02 |

| White (otherb) | −0.88 | 1.26 | −3.35 to 1.60 | −0.70 | 0.49 |

| Student (otherb) | 1.54 | 2.22 | −5.94 to 2.81 | −0.70 | 0.47 |

| No insurance(any insuranceb) | 4.38 | 1.92 | 0.76 to 8.62 | 2.47 | 0.02 |

| Common cancer types (otherb) | 1.50 | 1.37 | −0.54 to 4.54 | 1.10 | 0.27 |

| Comorbidity | 0.38 | 0.23 | −0.29 to 1.20 | 1.66 | 0.10 |

| Diagnosed before 2010 | −1.00 | 1.11 | −3.18 to 1.18 | −0.90 | 0.37 |

| Surgery involvement (no surgeryb) | −9.63 | 2.22 | −13.98 to −5.27 | −4.34 | 0.00 |

| Patient pathway | |||||

| Dx/Rx at MHSb | |||||

| Dx out of MHS | 15.88 | 2.29 | 11.38 to 20.37 | 6.94 | 0.00 |

| Rx out of MHS | 18.38 | 4.95 | 8.66 to 28.09 | 3.71 | 0.00 |

Model constant = 8.25, SE = 2.66, p = 0.002.

Reference group.

Bold italic indicates risk factors that are statistically significant.

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Estimates on Risk Odds Ratio of Dx-Rx Delays Using 1- and 4-Week Cutoffs

| Model | Factors | Odds ratio | SE | p | 95% CI of OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-week cutoff | No insurance at Dx (othera) | 1.067 | 0.262 | 0.791 | 0.660 | 1.726 |

| Patient pathway | ||||||

| Dx/Rx at MHSa | ||||||

| Dx out of MHS | 4.176 | 0.731 | 0.000 | 2.963 | 5.886 | |

| Rx out of MHS | 4.329 | 1.261 | 0.000 | 2.446 | 7.662 | |

| Sex (femalea) | 0.538 | 0.088 | 0.000 | 0.389 | 0.742 | |

| Student (othera) | 0.577 | 0.185 | 0.087 | 0.307 | 1.082 | |

| Common cancer types (othera) | 1.347 | 0.260 | 0.122 | 0.923 | 1.966 | |

| Surgery Rx (no surgery involveda) | 0.217 | 0.051 | 0.000 | 0.138 | 0.343 | |

| No. of Rx modalitiesb | 1.374 | 0.120 | 0.000 | 1.158 | 1.631 | |

| Comorbidityb | 1.009 | 0.066 | 0.891 | 0.888 | 1.146 | |

| Dx in year 2010 or later | 0.811 | 0.129 | 0.189 | 0.593 | 1.109 | |

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| <20a | ||||||

| 20–24 | 0.810 | 0.276 | 0.537 | 0.416 | 1.580 | |

| 25–29 | 1.206 | 0.389 | 0.561 | 0.641 | 2.270 | |

| 30–34 | 1.861 | 0.562 | 0.040 | 1.030 | 3.362 | |

| 35–39 | 1.942 | 0.557 | 0.021 | 1.107 | 3.046 | |

| Being white (othera) | 0.790 | 0.148 | 0.203 | 0.548 | 1.139 | |

| 4-week cutoff | No insurance at Dx (othera) | 1.845 | 0.531 | 0.035 | 1.044 | 3.249 |

| Patient pathway | ||||||

| Dx/Rx at MHSa | ||||||

| Dx out of MHS | 3.358 | 0.641 | 0.000 | 2.310 | 4.881 | |

| Rx out of MHS | 2.857 | 0.830 | 0.000 | 1.617 | 5.050 | |

| Sex (femalea) | 0.571 | 0.105 | 0.002 | 0.398 | 0.820 | |

| Student (othera) | 0.635 | 0.308 | 0.338 | 0.247 | 1.608 | |

| Common cancer types (othera) | 1.023 | 0.213 | 0.915 | 0.680 | 1.539 | |

| Surgery Rx (no surgery involveda) | 0.488 | 0.117 | 0.003 | 0.305 | 0.780 | |

| No. of Rx modalitiesb | 0.967 | 0.089 | 0.711 | 0.807 | 1.157 | |

| Comorbidityb | 0.983 | 0.069 | 0.811 | 0.856 | 1.129 | |

| Dx in year 2010 or later | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.998 | 1.000 | |

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| <20a | ||||||

| 20–24 | 0.529 | 0.209 | 0.754 | 0.432 | 3.182 | |

| 25–29 | 0.680 | 0.245 | 0.511 | 0.528 | 3.614 | |

| 30–34 | 0.767 | 0.793 | 0.284 | 0.655 | 4.236 | |

| 35–39 | 0.852 | 0.796 | 0.259 | 0.378 | 4.256 | |

| Being white (othera) | 0.683 | 0.130 | 0.053 | 0.466 | 1.005 | |

Reference group.

As a continuous predictor.

Bold italic indicates risk factors that are statistically significant.

Discussion

We identified several potential disparities in Dx-Rx intervals among AYAs. More than one-quarter of the AYA patients in this study had waits ≥4 weeks. Our study suggests that AYA cancer treatment delay is multifactorial. Transfer of care is a major and newly defined independent risk factor of timely cancer treatment delivery for AYAs captured in the community setting. Care transfer was robustly shown in our analysis to predict longer cancer treatment waits.

Compared with younger patients, AYAs older than 30 had longer wait in both univariable and multivariable models, similar to results from previous studies.43–45 The significant associations of lack of insurance with increased wait-times in the 4-week model, but not in the 1-week model, may show that insurance coverage reduces longer treatment waits, but does not help reduce the Dx-Rx gap at a more moderate level. Surgery involved in the treatment plan was associated with a shorter wait, while an increasing number of treatment modalities were associated with longer wait-times.

Prompt diagnosis and treatment initiation are associated with lower risk of metastatic spread and increased long-term survival.46–49 How medical facility transfer pre- and postcancer diagnosis impact cancer treatment initiation has not been sufficiently studied in the U.S., nor among AYAs. Our findings, based on cancer registry data, have proved that facility transfer is associated with longer wait to treatment initiation. The results support the rationale for recent initiatives, at our institution and throughout the U.S., to offer age-appropriate, high-quality cancer care for AYAs within their own communities.50

Data from other countries with national health care systems may have better rationale to attribute prediagnosis delays to patient behaviors and postdiagnosis delays to provider error and/or deficiencies in the health care system. However, in the U.S., decisions about transferring care may depend on multifaceted decision-making between patients, providers, health care systems, and payers.51 Future studies should investigate the root causes of medical transfers in AYAs and the impact on survival, and particularly compare findings with those for AYAs in countries with a universal single-payer system. Also, studies that empirically examine the interactions among patients, providers, health care systems, and insurance status are warranted.

Limitations include the following: (1) This is a retrospective study from a hospital-based registry, which is maintained for nonresearch, administrative purposes. (2) Because AYA is defined based on patients' age at diagnosis and includes many cancer types, justification on disease severity and cancer types is challenging. There are no tumor-agnostic guidelines to suggest a “reasonable” Dx-Rx interval for AYAs who present with a wide variety of cancer types and stages at diagnosis. Nor has there been a consensus on the appropriateness of some previously proposed delay thresholds for cancers in general. (3) Due to the retrospective feature of this study, determining whether the associations found can be explained by provider behaviors, preparatory procedures, insurance approval, system factors, or all of the above is beyond the scope of this article.

Our study suggests that the Dx-Rx interval among AYAs who use cancer-specific services at a community-level health care system in the U.S. varies due to multiple factors, of which care transfer is a significant attributable factor. The health care delivery system in the U.S. is still working to optimize care for the AYA cancer patient population.52 Understanding the status quo will help formulate standards of care for AYAs, in which timely referral and transition across providers and facilities can be supported.53 Larger, multi-institutional cohort studies using clinical severity stratification are warranted to confirm our findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Professor Larry Kessler and Professor Donald Patrick from the Department of Health Services, School of Public Health at the University of Washington-Seattle, and Professor Lonnie Nelson from Washington State University for valuable advice concerning the study design. This study is supported by the Northwest NCORP Grant Number: 1UG1CA189952-01, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Partnership (PCORP), and the Northwest Center for Public Health Practice. This study has been previously presented, in part, at the 2017 American College of Epidemiology Annual Conference (September 2017, New Orleans, LA) and at the AYA Global Congress 2017 (December 2017, Atlanta, GA).

Authors' Contributions

Conception and design: J.M., P.J.A., B.D., and L.-M.B. Administrative support: E.L.B., P.J.A., B.M.P., and L.L.F. Provision of study materials or patients: E.L.B. and R.H.J. Collection and assembly of data: J.M., E.L.B., P.J.A., and B.M.P. Data analysis and interpretation: J.M., R.H.J., and B.D. Article writing: all authors. Final approval of the article: all authors. Accountable for all aspects of the work: all authors.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Baker A. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. BMJ. 2001;323:1192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schroeder S, Berkowitz B, Berwick D, et al. Performance measurement: accelerating improvement. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:271–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dolly D, Mihai A, Rimel B, et al. A delay from diagnosis to treatment is associated with a decreased overall survival for patients with endometrial cancer. Front Oncol. 2016;6:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tørring ML, Frydenberg M, Hansen RP, et al. Evidence of increasing mortality with longer diagnostic intervals for five common cancers: a cohort study in primary care. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:2187–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carter-Harris L, Hermann CP, Schreiber J, et al. Lung cancer stigma predicts timing of medical help–seeking behavior. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41(3):E203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Facione NC. Delay versus help seeking for breast cancer symptoms: a critical review of the literature on patient and provider delay. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36:1521–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bozcuk H, Martin C. Does treatment delay affect survival in non-small cell lung cancer? A retrospective analysis from a single UK centre. Lung Cancer. 2001;34:243–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Walter F, Webster A, Scott S, Emery J. The Andersen model of total patient delay: a systematic review of its application in cancer diagnosis. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2012;17:110–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bleyer A, Budd T, Montello M. Adolescents and young adults with cancer. Cancer. 2006;107:1645–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu L, Moke DJ, Tsai K-Y, et al. A reappraisal of sex-specific cancer survival trends among adolescents and young adults in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018; DOI: 10.1093/jnci/djy140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Keegan TH, Ries LA, Barr RD, et al. Comparison of cancer survival trends in the United States of adolescents and young adults with those in children and older adults. Cancer. 2016;122(7):1009–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barr RD, Ferrari A, Ries L, Whelan J, Bleyer WA. Cancer in adolescents and young adults: a narrative review of the current status and a view of the future. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:495–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harlan LC, Lynch CF, Keegan TH, et al. Recruitment and follow-up of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors: the AYA HOPE Study. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:305–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:220–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:252–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hollis R, Morgan S. The adolescent with cancer—at the edge of no-man's land. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:43–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ferrari A, Bleyer A. Participation of adolescents with cancer in clinical trials. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33:603–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nass SJ, Beaupin LK, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Identifying and addressing the needs of adolescents and young adults with cancer: summary of an Institute of Medicine workshop. Oncologist. 2015;20:186–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bleyer A. Adolescent and young adult (AYA) oncology: the first A. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2007;24:325–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bleyer WA, Barr RD. Cancer in adolescents and young adults. New York: Springer; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meeneghan MR, Wood WA. Challenges for cancer care delivery to adolescents and young adults: present and future. Acta Haematol. 2014;132:414–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kyle RG, Macmillan I, Rauchhaus P, et al. Adolescent Cancer Education (ACE) to increase adolescent and parent cancer awareness and communication: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Martin S, Ulrich C, Munsell M, et al. Delays in cancer diagnosis in underinsured young adults and older adolescents. Oncologist. 2007;12:816–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bilimoria KY, Ko CY, Tomlinson JS, et al. Wait times for cancer surgery in the United States: trends and predictors of delays. Ann Surg. 2011;253:779–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yorio JT, Xie Y, Yan J, Gerber DE. Lung cancer diagnostic and treatment intervals in the United States: a health care disparity? J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:1322–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Allgar V, Neal R. Delays in the diagnosis of six cancers: analysis of data from the National Survey of NHS Patients: Cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1959–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coates A. Breast cancer: delays, dilemmas, and delusions. Lancet. 1999;353:1112–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dang-Tan T, Trottier H, Mery LS, et al. Delays in diagnosis and treatment among children and adolescents with cancer in Canada. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:468–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chapple A, Ziebland S, McPherson A. Qualitative study of men's perceptions of why treatment delays occur in the UK for those with testicular cancer. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:25–32 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dood R, Haynes K, Ko E. Risk factors for surgical treatment delay in women with endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;141:37 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bleyer A. Young adult oncology: the patients and their survival challenges. CA Cancer J Clini. 2007;57:242–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Community Cancer Care and the US Oncology Network. The US oncology network. Accessed December30, 2018 from: https://media.gractions.com/E5820F8C11F80915AE699A1BD4FA0948B6285786/19947648-3e9d-43c7-b73b-43e12f93e773.pdf

- 34. Adamo M, Johnson C, Ruhl J, Dickie L. SEER program coding and staging manual. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Ko CY. The national cancer data base: a powerful initiative to improve cancer care in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:683–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hayat MJ, Howlader N, Reichman ME, Edwards BK. Cancer statistics, trends, and multiple primary cancer analyses from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Oncologist. 2007;12:20–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. NIH/NCI. Data Collection Answers from the CoC, NPCR, SEER Technical Workgroup. NIH. June 10, 2016. Accessed December30, 2018 from: https://seer.cancer.gov/registrars/data-collection.html

- 38. Adamo M, Dickie L, Ruhl J. SEER Program Coding and Staging Manual 2016 in: Services USDoHaH, ed. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute; 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jensen OM. Cancer registration: principles and methods. Vol. 95 Lyon, France: IARC; 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Basu A, Manning WG, Mullahy J. Comparing alternative models: Log vs Cox proportional hazard? Health Econ. 2004;13:749–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moriguchi S, Hayashi Y, Nose Y, et al. A comparison of the logistic regression and the Cox proportional hazard models in retrospective studies on the prognosis of patients with gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 1993;52:9–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fitzenberger B. The moving blocks bootstrap and robust inference for linear least squares and quantile regressions. J Economet. 1998;82:235–87 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Saha V, Love S, Eden T, et al. Determinants of symptom interval in childhood cancer. Arch Dis Child. 1993;68:771–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Haimi M, Nahum MP, Arush MWB. Delay in diagnosis of children with cancer: a retrospective study of 315 children. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2004;21:37–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pollock BH, Krischer JP, Vietti TJ. Interval between symptom onset and diagnosis of pediatric solid tumors. J Pediatr. 1991;119:725–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Huang J, Barbera L, Brouwers M, et al. Does delay in starting treatment affect the outcomes of radiotherapy? A systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:555–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Richards M, Smith P, Ramirez A, et al. The influence on survival of delay in the presentation and treatment of symptomatic breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Biagi JJ, Raphael MJ, Mackillop WJ, et al. Association between time to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy and survival in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305:2335–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Neal R, Tharmanathan P, France B, et al. Is increased time to diagnosis and treatment in symptomatic cancer associated with poorer outcomes? Systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2015;112 Suppl 1:S92–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Johnson RH. AYA in the USA. International Perspectives on AYAO, Part 5. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2013;2:167–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Han X, Xiong KZ, Kramer MR, Jemal A. The affordable care act and cancer stage at diagnosis among young adults. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108:djw058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Thomas DM, Albritton KH, Ferrari A. Adolescent and young adult oncology: an emerging field. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4781–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zebrack B, Mathews-Bradshaw B, Siegel S. Quality cancer care for adolescents and young adults: a position statement. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4862–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]