Abstract

Rationale: Microbiological confirmation of pulmonary tuberculosis in children is desirable.

Objectives: To investigate the diagnostic accuracy and incremental yield of Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra (Ultra; Cepheid), a new rapid test, on repeated induced sputum, nasopharyngeal aspirates, and combinations of specimens.

Methods: Consecutive South African children hospitalized with suspected pulmonary tuberculosis were enrolled.

Measurements and Main Results: Induced sputum (IS) and nasopharyngeal aspirates (NPAs) were obtained. NPAs were frozen; IS underwent liquid culture, and an aliquot was frozen. Ultra was performed on thawed NPAs and IS specimens individually. Children were categorized as confirmed, unconfirmed, or unlikely tuberculosis according to NIH consensus case definitions. The diagnostic accuracy of Ultra was compared with liquid culture on IS. In total, 195 children (median age: 23.3 mo; 32 [16.4%] HIV-infected) had one IS and NPA, and 130 had two NPAs. There were 40 (20.5%) culture-confirmed cases. Ultra was positive on NPAs in 26 (13.3%) and on IS in 31 (15.9%). Sensitivity and specificity of Ultra on one NPA were 46% and 98%, respectively, and similar by HIV status. Sensitivity and specificity of Ultra on one IS were 74.3% and 96.9% respectively. Combining one NPA and one IS increased sensitivity to 80%. Sensitivity using Ultra on two NPAs was 54.2%, increasing to 87.5% with an IS Ultra.

Conclusions: IS provides a better specimen than repeated NPA for rapid diagnosis using Ultra. However, Ultra testing of combinations of specimens provides a novel strategy that can be adapted to identify most children with confirmed pulmonary tuberculosis.

Keywords: tuberculosis, child, Xpert Ultra, induced sputum, nasopharyngeal aspirate

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Microbiological diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) in children remains challenging. Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra, a new diagnostic on the GeneXpert platform with greater sensitivity than Xpert, has not been well tested in children, with only two studies reporting sensitivities of 64–77% when testing was done on a single induced sputum (IS).

What This Study Adds to the Field

We investigated the yield of Ultra on repeated respiratory specimens (IS and nasopharyngeal [NP] samples) against a gold standard of liquid culture. Overall, IS provided a better specimen than repeated NPs for rapid diagnosis. We found the highest yield from Ultra testing of a single IS and two separate NPs, which detected 87% of cases, amongst the highest sensitivity reported for a rapid diagnostic in children. A single IS and NP detected 80% of cases, while an IS alone detected 74%. In contrast, an NP detected only 46% of cases, which increased to 54% with a second NP. IS provides an optimal sample for diagnostic confirmation of pulmonary TB in children. Although guidelines recommend a single rapid PCR test in children with suspected TB, a second test on a respiratory sample is important to enhance yield in children. Testing multiple different respiratory specimens provides a novel and useful strategy for rapid diagnosis of pediatric TB with Ultra.

Tuberculosis (TB) in children is a major public health problem, with almost 1 million new cases reported each year. However, modeling estimates indicate that only 30% of childhood TB cases are diagnosed and notified (1). In contrast, a latent class analysis of children with suspected pulmonary TB (PTB) suggests that TB disease may be overdiagnosed in children in a high-burden setting (2). Diagnosis of PTB in children is challenging because of nonspecific clinical or radiologic signs, paucibacillary disease, and lack of capacity, expertise, and infrastructure for microbiological diagnosis (3). Microbiological confirmation of PTB is desirable in children because it enables timely and effective treatment, limits unnecessary use of TB therapy, and can identify drug-resistant disease.

Advances in specimen collection and the emergence of rapid molecular diagnostics have improved the ability to rapidly obtain a microbiologic diagnosis, enabling prompt initiation of therapy. Induced sputum (IS) specimens have been shown to be feasible and useful for microbiologic diagnosis using culture or Xpert MTB/RIF (Xpert) in several settings in low- and middle-income countries (4–7). A meta-analysis reported that the sensitivity of Xpert compared with culture on IS in children was 65% for a single IS specimen (8). Several studies have reported an incremental yield with repeated IS specimens, with the sensitivity of Xpert done on two sequential IS specimens as high as 76% (9). Nasopharyngeal aspirates (NPAs) are more easily obtained than IS; Xpert on two NPAs has been reported to have a sensitivity of 65% for diagnosis when compared with culture confirmation from IS (10). Importantly in children, repeated specimens, either IS or NPAs, are needed for reasonable sensitivity (4, 10).

Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra (Ultra; Cepheid), a new diagnostic for TB on the GeneXpert platform, has a substantially lower limit of detection than Xpert and improved sensitivity in studies of adults (11). We recently reported that the sensitivity and specificity of a single Ultra test done on one IS in children with suspected PTB was 77% and 97%, respectively, compared with liquid culture; this was similar to the accuracy of Xpert testing on IS (12). However, we did not perform Ultra on NPAs, nor were we able to investigate the yield from combinations of different specimens. The aim of this study was to investigate the yield from Ultra on repeated NPA specimens and the use of combinations of IS and NPA specimens to maximize diagnostic yield in children.

Methods

Consecutive children hospitalized with suspected PTB in Cape Town, South Africa, from April 1, 2012, to September 30, 2017, were enrolled. Eligibility criteria were age younger than 15 years and cough of any duration with one of the following conditions: a household TB contact within the preceding 6 months, weight loss or failure to gain weight within the preceding 3 months, a positive tuberculin skin test (TST) to PPD (PPD 2TU, PPD RT23; Staten Serum Institute), or a chest radiograph suggestive of PTB. Children were excluded if they had received TB therapy or prophylaxis for longer than 72 hours, they were not resident in Cape Town, informed consent was unavailable, or an IS and NPA were not obtained.

All children had a chest radiograph, a TST, and HIV testing when HIV status was unknown. HIV-infected children were classified by World Health Organization (WHO) clinical staging; CD4 count and HIV viral load (Abbott RealTime HIV-1 assay) were done. Nutritional status was calculated as height-for-age and weight-for-age z-scores using 2006 WHO child growth standards. TB therapy was initiated at the discretion of the treating doctor. Follow-up visits were done at 1, 3, and 6 months for children diagnosed with PTB and started on tuberculosis therapy and at 1 and 3 months for those not treated. Response to treatment was assessed at follow-up by recording signs and symptoms; the chest radiograph was repeated at completion of TB therapy.

Children were categorized into one of three diagnostic categories according to the revised NIH consensus definition (13) but excluding results of Ultra tests to avoid inclusion bias: “confirmed TB” (culture positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis), “unconfirmed TB” (culture negative, clinically diagnosed with TB), and “unlikely TB” (culture negative, not clinically diagnosed with TB, no tuberculosis treatment given, and documented improvement at 3-mo follow-up visit). Written informed consent was obtained from a parent or legal guardian, and assent was received from children older than 7 years. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town.

Specimen Collection and Laboratory Procedures

Two NPA and two IS specimens were obtained as described previously (10). The NPA was done before IS. Two drops of sterile saline were instilled into each nostril, and the nasopharynx was suctioned using a sterile catheter with a mucus trap. Sputum induction was done at least 30 minutes after an NPA, following a 2- to 3-hour fast by a trained research nurse, as described previously. The second NPA and IS were obtained the next day or a minimum of 4 hours after the first IS. Pulse oximetry was done throughout the procedure and 30 minutes thereafter.

NPA and IS specimens were processed within 2 hours of collection in an accredited laboratory, using standardized protocols. For both specimens, following standard decontamination with sodium hydroxide, centrifuged deposits were resuspended in 1.5 ml of phosphate buffer. For both sputum and nasopharyngeal samples, a drop of sediment was used for fluorescent acid-fast smear microscopy, and 0.5 ml of resuspended pellet was used for automated liquid culture (BACTEC MGIT; Becton Dickinson). Cultures were incubated for up to 6 weeks. Positive cultures were identified by acid-fast staining followed by GenoType MTBDRplus testing (Hain Lifescience). For the first IS, an aliquot of 0.5 ml was used for Xpert testing, as per the manufacturer’s recommendations. For the second IS, an aliquot of 0.5 ml was frozen at −80°C; frozen aliquots from the second sample were subsequently thawed in batches for Ultra testing according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Both NPAs were frozen and subsequently thawed for Ultra testing, which was done on each NPA individually. Staff performing Ultra test results were blinded to clinical and other microbiological results. If Ultra identified rifampicin resistance, the corresponding cultured isolate also underwent phenotypic resistance testing by automated liquid MGIT culture.

Analysis

The primary reference standard was a positive culture for M. tuberculosis from an IS. We excluded children without at least one IS and one NPA specimen. We used a positive culture from the first IS specimen as the reference standard to determine the sensitivity and specificity of a single Ultra on NPA in a per-sample analysis and a positive culture from any IS specimen as the reference standard to determine the sensitivity and specificity of a single Ultra on the IS or NPA in a per-patient analysis. The sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of the assays with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were determined. The incremental yield from a second IS culture, a second NPA Ultra, or the combination of Ultra on an IS and NPA was calculated. Data were analyzed using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp).

Simple summary statistics were used to describe the study population. Continuous data were summarized as median and interquartile range (IQR); categorical data were summarized as number and proportion. Statistical tests included the chi-square test, a two-sample test of equal proportions, and the Kruskal-Wallis test to compare medians. Statistical tests were two-sided at α = 0.05.

Results

Study Population

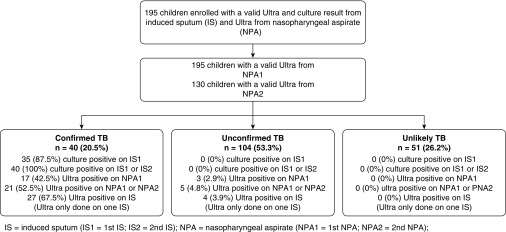

We included 195 children with Ultra and culture on IS and an NPA for Ultra; of these, 130 also had a second NPA for testing (Figure 1). Of the 195 children, 40 (20.5%) had confirmed TB, 104 (53.3%) had unconfirmed TB, and 51 (26.2%) had unlikely TB (Figure 1). The median age of children was 23.3 months (IQR, 13.5–47.3 mo), which was similar across TB categories, P = 0.53, (Table 1). The median weight-for-age z-score was −0.8 (IQR, −2.0 to 0) and height-for-age z-score was −0.9 (IQR, −2.2 to 0.3); 46 (24.6%) children were underweight for age, and 42 (26.4%) were stunted (Table 1). Nutritional status was similar across TB categories. There were 32 (16.4%) HIV-infected children, with a similar proportion in all diagnostic categories; most were WHO stage 3 or 4 at the time of diagnosis. Only 15 (7.7%) of the children had received previous treatment for TB. A positive TST occurred in 99 (57.2%); this proportion was higher in the confirmed TB category, in which 91% were positive (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participants. IS = induced sputum; NPA = nasopharyngeal aspirate; TB = tuberculosis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Children by TB Category

| Variable | All (N = 195) | Confirmed TB (n = 40 [20.5%]) | Unconfirmed TB (n = 104 [53.3%]) | Unlikely TB (n = 51 [26.2%]) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mo, median (IQR) | 23.3 (13.5 to 47.3) | 27.4 (15.3 to 57.6) | 22.6 (11.7 to 44.9) | 22.8 (14.0 to 47.7) | 0.533 |

| Age category | |||||

| <5 yr | 160 (82.0) | 31 (77.5) | 86 (82.7) | 43 (84.3) | 0.681 |

| ≥5 yr | 35 (18.0) | 9 (22.5) | 18 (17.3) | 8 (15.7) | |

| HIV infection | 32 (16.4) | 6 (15.0) | 17 (16.4) | 9 (17.7) | 0.911 |

| WHO clinical staging | |||||

| Stage 1 | 1 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | 0.012 |

| Stage 2 | 4 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (50.0) | |

| Stage 3 | 12 (46.2) | 2 (33.3) | 8 (66.7) | 2 (25.0) | |

| Stage 4 | 9 (34.6) | 4 (66.7) | 4 (33.3) | 1 (12.5) | |

| History of previous tuberculosis | 15 (7.7) | 2 (5.0) | 7 (6.7) | 6 (11.8) | 0.595 |

| WAZ, median (IQR) | −0.8 (−2.0 to −0.0) | −1.0 (−1.6 to −0.3) | −0.7 (−2.3 to 0.1) | −0.7 (−1.6 to −0.0) | 0.739 |

| HAZ, median (IQR) | −0.9 (−2.2 to 0.3) | −1.2 (−2.0 to −0.1) | −0.9 (−2.8 to 0.4) | −0.8 (−1.7 to 0.7) | 0.400 |

| Underweight for age | 46 (24.6) | 8 (20.0) | 30 (29.4) | 8 (17.8) | 0.239 |

| Malnourished | 24 (12.8) | 4 (10.0) | 17 (16.7) | 3 (6.7) | 0.206 |

| Stunted | 42 (26.4) | 8 (23.5) | 26 (32.1) | 8 (18.2) | 0.220 |

| Severe stunting | 26 (16.4) | 3 (8.8) | 19 (23.5) | 4 (9.1) | 0.047 |

| TST positive | |||||

| All children | 99 (57.2) | 32 (91.4) | 61 (64.9) | 6 (13.6) | <0.001 |

| HIV infected | 13 (54.2) | 3 (75.0) | 8 (61.5) | 2 (28.6) | 0.243 |

| HIV uninfected | 85 (57.4) | 29 (93.6) | 52 (65.0) | 4 (10.8) | <0.001 |

Definition of abbreviations: HAZ = height-for-age z-score; IQR = interquartile range; TB = tuberculosis; TST = tuberculin skin test; WAZ = weight-for-age z-score; WHO = World Health Organization.

Data are n (%), except as noted.

Performance of Ultra on a Single NPA or a Single IS Compared with a Reference Standard of Culture on a Single IS

Among 195 children with at least one IS and NPA, Ultra was positive on 20 (10.3%) NPA and 31 (15.9%) IS; there were 35 (18%) culture-positive cases on the corresponding IS. Most Ultra-positive cases on an NPA were in culture-confirmed cases, with only 3 positive in the unconfirmed category and none in the unlikely category (Figure 1). Similarly, most Ultra-positive tests on IS were in the confirmed category, with 4 positives among unconfirmed cases and none in the unlikely category (Figure 1). Of those with a positive Ultra but negative culture, none had been on TB treatment for more than 72 hours when the IS was taken. Ultra semiquantitative results were predominantly trace or very low (Table 2). Among the children with trace Ultra-positive results on either the first or second NPA, 9 of 13 (69.2%) were culture positive. The sensitivity and specificity of Ultra on a single NPA using culture from a single IS sample as the reference standard were 45.7% and 97.5%, respectively (Table 3). The sensitivity in HIV-infected children was similar to that in HIV-uninfected children (Table 3). The sensitivity and specificity of Ultra on one IS was 74.3% and 96.9%, respectively, with similar sensitivity in HIV-infected and -uninfected children (Table 3). Among children treated for prior TB, Ultra sensitivity was similar to those never treated (50.0% [95% CI, 1.2–98.7%] vs. 46.9% [95% CI, 29.1–65.3%]); specificity was nonsignificantly lower in those with prior treatment (92.3% [95% CI, 64.0–99.8%] vs. 97.9% [95% CI, 94.1–99.6%]; P = 0.22) (Table 3). In 165 children in whom Xpert MTB/RIF was performed on a first IS, the sensitivity and specificity were 68.6% and 97.8%, respectively (Table 3). The sensitivity and specificity of Ultra tests combining results from one NPA and one IS was 80% and 95%, respectively, using a reference standard of a single IS culture (Table 3).

Table 2.

Ultra Semiquantitative Results on NPA

| Sample | Negative | Trace | Very Low | Low | Moderate | High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First NPA (n = 195) | 175 | 9 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| Second NPA (n = 130) | 118 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

Definition of abbreviation: NPA = nasopharyngeal aspirate.

Table 3.

Accuracy of a Single Ultra from NPA or IS Compared with Sputum Culture

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPA | ||||

| Ultra on NPA (n = 195) | ||||

| Number positive/number tested (%) | 16/35 (45.7) | 156/160 (97.5) | 156/175 (89.1) | 16/20 (80.0) |

| 95% CI | 28.8–63.3 | 93.7–99.3 | 83.6–93.3 | 56.3–94.3 |

| By HIV infection status | ||||

| HIV infected (n = 32) | ||||

| Number positive/number tested (%) | 3/6 (50.0) | 26/26 (100.0) | 3/3 (100.0) | 26/29 (89.7) |

| 95% CI | 11.8–88.2 | 87.1–100.0 | 43.9–100.0 | 72.6–97.8 |

| HIV uninfected (n = 162) | ||||

| Number positive/number tested (%) | 13/29 (44.8) | 129/133 (97.0) | 13/17 (76.5) | 129/145 (89.0) |

| 95% CI | 26.4–64.3 | 92.5–99.2 | 50.1–93.2 | 82.7–93.6 |

| By TB treatment | ||||

| Prior TB treatment (n = 15) | ||||

| Number positive/number tested (%) | 1/2 (50.0) | 12/13 (92.3) | 1/2 (50.0) | 12/13 (92.3) |

| 95% CI | 1.2–98.7 | 64.0–99.8 | 1.2–98.7 | 64.0–99.8 |

| No prior TB treatment (n = 177) | ||||

| Number positive/number tested (%) | 15/32 (46.9) | 142/145 (97.9) | 15/18 (83.3) | 142/159 (89.3) |

| 95% CI | 29.1–65.3 | 94.1–99.6 | 58.6–96.4 | 83.4–93.6 |

| | ||||

| IS | ||||

| Xpert MTB/RIF* on IS (n = 165) | ||||

| Number positive/number tested (%) | 24/35 (68.6) | 132/135 (97.8) | 21/24 (87.5) | 132/141 (93.6) |

| 95% CI | 50.7–83.1 | 93.6–99.5 | 67.6–97.3 | 88.2–97.0 |

| Ultra on IS (n = 195) | ||||

| Number positive/number tested (%) | 26/35 (74.3) | 155/160 (96.9) | 26/31 (83.9) | 155/164 (94.5) |

| 95% CI | 56.7–87.5 | 92.9–99.0 | 66.3–94.5 | 90.0–97.5 |

| By HIV infection status | ||||

| HIV infected (n = 32) | ||||

| Number positive/number tested (%) | 3/6 (50.0) | 26/26 (100.0) | 3/3 (100.0) | 26/29 (89.7) |

| 95% CI | 11.8–88.2 | 87.1–100.0 | 43.9–100.0 | 72.6–97.8 |

| HIV uninfected (n = 162) | ||||

| Number positive/number tested (%) | 23/29 (79.3) | 128/133 (96.2) | 23/28 (82.1) | 128/134 (95.5) |

| 95% CI | 60.3–92.0 | 91.4–98.8 | 63.1–93.9 | 90.5–98.3 |

| Ultra on NPA and IS | ||||

| Number positive/number tested (%) | 28/35 (80.0) | 152/160 (95.0) | 28/36 (77.8) | 152/159 (95.6) |

| 95% CI | 63.1–91.6 | 90.4–97.8 | 60.8–89.9 | 91.1–98.2 |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; IS = induced sputum; NPA = nasopharyngeal aspirate; NVP = negative predictive value; PPV = positive predictive value; TB = tuberculosis.

One hundred sixty-five children have Xpert MTB/RIF on the first induced sputum.

Performance of Ultra on Repeated NPA or IS Specimens Compared with a Reference Standard of Sputum Culture

Among 130 children with two NPAs for Ultra testing, there were 24 (18.5%) culture-confirmed cases from one IS specimen. There were 11 Ultra-positive tests on the first NPA (10 in confirmed TB and 1 in unconfirmed TB cases) and 12 on the second NPA (10 in confirmed TB and 2 in unconfirmed TB cases). The sensitivity and specificity of Ultra from the first NPA were 37.5% and 98.1%, respectively; results were similar on the second NPA (37.5% and 97.2%, respectively) (Table 4). However, Ultra on the second NPA detected an additional 4 cases, increasing the yield from 9 cases to 13, (Table 4), and the sensitivity to 54.2% with a specificity of 96.2% (Table 4). Of these four cases, Ultra testing was trace in two and very low or low in a single case each. Ultra on a single IS detected 17 of 24 cases (sensitivity, 70.8%; specificity, 96.2%); the addition of a single-sputum Ultra to testing of two NPAs increased sensitivity to 87.5% with a specificity of 93.4% (Table 4).

Table 4.

Accuracy of Ultra from Two NPAs and from IS Compared with Sputum Culture in All Children with Two NPA Samples (n = 130)

| Accuracy of Ultra MTB/RIF | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| From NPA1 (n = 130) | ||||

| Number positive/number tested (%) | 9/24 (37.5) | 104/106 (98.1) | 9/11 (81.8) | 104/119 (87.4) |

| 95% CI | 18.8–59.4 | 93.4–99.8 | 48.2–97.7 | 80.1–92.8 |

| From NPA2 (n = 130) | ||||

| Number positive/number tested (%) | 9/24 (37.5) | 103/106 (97.2) | 9/12 (75.0) | 103/118 (87.3) |

| 95% CI | 18.8–59.4 | 92.0–99.4 | 42.8–94.5 | 80.0–92.7 |

| From NPA1 or NPA2 positive (n = 130) | ||||

| Number positive/number tested (%) | 13/24 (54.2) | 102/106 (96.2) | 13/17 (76.5) | 102/113 (90.3) |

| 95% CI | 32.8–74.4 | 90.6–99.0 | 50.1–93.2 | 83.2–95.0 |

| From one IS (n = 130) | ||||

| Number positive/number tested (%) | 17/24 (70.8) | 102/106 (96.2) | 17/21 (81.0) | 102/109 (93.6) |

| 95% CI | 48.9–87.4 | 90.6–99.0 | 58.1–94.6 | 87.2–97.4 |

| From NPA1, NPA2, and IS compared with culture on IS | ||||

| Number positive/number tested (%) | 21/24 (87.5) | 99/106 (93.4) | 21/28 (75.0) | 99/102 (97.1) |

| 95% CI | 67.6–97.3 | 86.9–97.3 | 55.1–89.3 | 91.6–99.4 |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; IS = induced sputum; NPA = nasopharyngeal aspirate; NVP = negative predictive value; PPV = positive predictive value.

Rifampicin Resistance and Time to Results

Results for rifampicin susceptibility testing were available from culture (followed by MTBDRplus) and Ultra in 30 isolates (Table 5). Rifampicin susceptibility was identified in 21 of 28 isolates by Ultra and culture, one isolate was resistant by both MTBDRplus and Ultra, seven were indeterminate on Ultra but sensitive on MTBDRplus, and one isolate was sensitive by Ultra but indeterminate by MTBDRplus. Among samples with valid results, the sensitivity and specificity of Ultra for diagnosis of rifampicin resistance were both 100%. Ultra results were available within 1 day—faster than for culture (1 d [IQR, 1–1 d] vs. 19 d [IQR, 12–25d]; P < 0.001).

Table 5.

Detection of Rifampicin Resistance by Ultra on NPA and Culture or MTBDRplus-based Drug Susceptibility Testing

| Ultra | MTBDRplus |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistant | Sensitive | Inconclusive | Totals | |

| Resistant | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sensitive | 0 | 21 | 1 | 22 |

| Inconclusive | 0 | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| Total | 1 | 28 | 1 | 30 |

Definition of abbreviation: NPA = nasopharyngeal aspirate.

Discussion

In this study, we found that Ultra performed on combinations of respiratory specimens could detect the majority of young children with confirmed PTB. The yield from Ultra improved with the number of specimens, with the best results—detection of 87% of culture-confirmed cases on a single sputum—obtained from testing two NPAs and a single IS. A single NPA Ultra had sensitivity of up to 46%, and two NPAs increased this to 54%, whereas a single Ultra on IS had sensitivity of 74%, and a single IS and NPA further increased this to 80%. The yield from additional specimens is consistent with prior studies reporting on the incremental yield for culture or Xpert on IS and on NPAs (4, 10). The increased sensitivity from a second specimen may be due to detection of cases that were missed due to a low bacillary load, as shown by most cases having low or trace Ultra results. Trace positive results are reported when the multicopy targets of the Ultra assay are positive but rpoB (ribosomal polymerase B) amplification is unsuccessful. These likely represent samples with very low bacillary load that are true positives, as shown by approximately 70% also being culture positive. Trace positive results in children who are symptomatic should be regarded as indicative of microbiologic confirmation. Although the WHO recommendations are currently for a single Xpert test for children with suspected TB, our findings indicate that a second test on a respiratory specimen is important to enhance yield in children.

The yield of Ultra from a single IS and NPA (80%) or from a single IS and two NPAs (87%) is among the highest that has been reported for a rapid pediatric diagnostic test and is higher than has been reported for Xpert. This may be partly due to the improved limits of detection for M. tuberculosis with Ultra (14). The use of combinations of specimens for rapid diagnosis in children may also offer a new improved strategy. Rapid diagnosis is especially important in young children, in whom timely initiation of therapy is crucial to prevent progression of disease and mortality. In addition, the ability to rapidly detect rifampicin resistance is important in initiating optimal therapy in children for effective treatment. Ultra results were potentially available on the same day—much quicker than the time to obtain culture results. Late initiation of therapy is a challenge in children, with reports that 20–47% of children with culture-confirmed TB are discharged from the hospital without commencing TB therapy because of the delay in diagnosis (15). Testing of a combination of specimens with Ultra may enable rapid diagnosis in a high proportion of children, allowing for immediate initiation of TB therapy, including adjusting therapy when there is rifampicin resistance and minimizing the number of patients who go untreated or who receive delayed treatment.

This study is the first to report on the yield from Ultra testing on NPAs. The use of NPAs offers an attractive strategy in children because NPAs can be noninvasively and relatively easily obtained. Pediatric studies from Uganda, Yemen, and Peru using culture and in-house polymerase chain reaction on NPA and other specimens reported previously that NPAs may be useful for diagnosis with a yield similar or less than that from IS (16–18). However, these studies enrolled older children with smaller sample sizes and did not repeat NPAs or use Ultra. We reported previously that the yield of two Xpert tests done on repeated IS specimens or on repeated NPAs was similar, at 71% and 65%, respectively (10); however, IS provided a significantly higher yield from culture. Therefore an IS specimen is preferable for culture IS rather than an NPA. Furthermore, in the current study, a single Ultra test on IS detected substantially more cases than that from a single NPA or from repeated NPAs. The sensitivity for Ultra on IS is consistent with our prior findings (12) and with findings recently reported in a pediatric Tanzanian study in which the sensitivity of Ultra (64%) was found to be higher than that of Xpert (54%) on a single sputum (19). These are the only two published studies on the diagnostic performance of Ultra in children. IS has been widely used in pediatric studies of TB in low- and middle-income settings such as Tanzania, Uganda, Malawi, Bangladesh, and several settings in South Africa and is safe and effective for diagnosis (5, 6, 8, 19). Sputum induction can also be done in primary care settings and has been shown to improve diagnostic yield for TB using either culture or Xpert, although there are few studies in such settings (4, 20). Strategies to strengthen the capacity for healthcare systems and training of health workers to undertake sputum induction in children should be strengthened for optimal diagnosis. In addition, the feasibility of different sampling strategies in primary care settings to optimize yield should be explored further; in some settings where samples can be collected on only 1 day, a single NPA and IS on the same day may be most feasible.

Approximately half of patients were clinically diagnosed with TB but were culture negative. Among these, a minority were Ultra positive; these likely represent true-positive cases because all were symptomatic and improved with TB therapy. Although false-positive Ultra results have been reported, particularly in adults previously treated for TB (14), this is likely to be less of a problem in young children, who infrequently have been treated for TB, as in the current study. This may suggest an additional role for Ultra in detecting cases of childhood TB that are culture negative. Further work is needed to study those children with positive Ultra and negative culture results to determine whether these represent cases missed by culture or are falsely positive. However, these results also underscore the pressing need for a better diagnostic test to distinguish those children who truly have TB among the unconfirmed TB cases.

A limitation of this study was the small numbers of HIV-infected children with culture-confirmed disease. However, as programs for prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission have been strengthened and antiretroviral therapy has become more widely available, the number of HIV-infected children has declined substantially. In addition, our results indicate similar diagnostic performance in HIV-infected and -uninfected children. A further limitation is that we were able to test only a single sputum sample with Ultra; however, the sensitivity of 74% was high and comparable to or higher than that reported for repeated Xpert testing on sputum in children (10). Ultra was performed on frozen samples that were thawed and concentrated by centrifugation before testing; results cannot be directly extrapolated to testing of fresh or unconcentrated samples. Future studies should investigate the performance of Ultra on fresh or unconcentrated samples. The generalizability of results to children with less severe illness who do not require hospitalization requires further study. Finally, we tested each sample separately so as to investigate the yield from each sample; additional studies using a single Ultra test on combined samples are needed. However, a recent study reported that pooling specimens (IS, gastric lavage, NPA) did not result in improved diagnostic accuracy from Xpert or culture compared with a single specimen (21).

Conclusions

Testing multiple different respiratory specimens provides a novel and useful strategy for rapid diagnosis of pediatric TB with Ultra. Ultra on two NPAs and on a single IS detected 87% of culture-confirmed cases, whereas testing on a single IS and NPA detected 80% of cases. IS provides a higher yield than NPAs and is preferable for Ultra and for culture confirmation; the capacity of health systems to undertake sputum induction in children must be strengthened globally. Better strategies for rapidly confirming a diagnosis of TB in children are urgently needed.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

Ultra cartridges were provided by the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics. The authors thank the National Health Laboratory Service diagnostic microbiology at Groote Schuur Hospital, the children who participated in the study, the children’s carers, the staff at Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital for their support, and Dr. Jeffrey Starke from Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, for his continued guidance and support.

Footnotes

Supported by the Regional Prospective Observational Research in Tuberculosis Consortium, which is cofunded by the Medical Research Council of South Africa and the U.S. Office of AIDS Research of the U.S. NIH. Additional funding was received from the Medical Research Council of South Africa for the Tuberculosis Collaborating Centre for Child Health and for the SA MRC Unit on Child and Adolescent Health and from the U.S. NIH (R01HD058971). The funding sources played no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author Contributions: H.J.Z. and M.P.N. conceived and supervised the study and obtained funding. H.J.Z. primarily drafted the manuscript. L.J.W. was responsible for data management and analysis. M.P. and L.J.B. enrolled patients and collected specimens and data. S.P.M. was responsible for coordinating microbiologic testing. C.B.W. oversaw clinical aspects. C.M.D. provided expert advice regarding Ultra testing and protocols. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201904-0772OC on August 5, 2019

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Dodd PJ, Gardiner E, Coghlan R, Seddon JA. Burden of childhood tuberculosis in 22 high-burden countries: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2:e453–e459. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70245-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schumacher SG, van Smeden M, Dendukuri N, Joseph L, Nicol MP, Pai M, et al. Diagnostic test accuracy in childhood pulmonary tuberculosis: a Bayesian latent class analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184:690–700. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connell TG, Zar HJ, Nicol MP. Advances in the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected children. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:S1151–S1158. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zar HJ, Workman L, Isaacs W, Dheda K, Zemanay W, Nicol MP. Rapid diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in African children in a primary care setting by use of Xpert MTB/RIF on respiratory specimens: a prospective study. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e97–e104. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Planting NS, Visser GL, Nicol MP, Workman L, Isaacs W, Zar HJ. Safety and efficacy of induced sputum in young children hospitalised with suspected pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18:8–12. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rachow A, Clowes P, Saathoff E, Mtafya B, Michael E, Ntinginya EN, et al. Increased and expedited case detection by Xpert MTB/RIF assay in childhood tuberculosis: a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:1388–1396. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bates M, O’Grady J, Maeurer M, Tembo J, Chilukutu L, Chabala C, et al. Assessment of the Xpert MTB/RIF assay for diagnosis of tuberculosis with gastric lavage aspirates in children in sub-Saharan Africa: a prospective descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:36–42. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70245-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Detjen AK, DiNardo AR, Leyden J, Steingart KR, Menzies D, Schiller I, et al. Xpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:451–461. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00095-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicol MP, Workman L, Isaacs W, Munro J, Black F, Eley B, et al. Accuracy of the Xpert MTB/RIF test for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in children admitted to hospital in Cape Town, South Africa: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:819–824. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70167-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zar HJ, Workman L, Isaacs W, Munro J, Black F, Eley B, et al. Rapid molecular diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in children using nasopharyngeal specimens. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:1088–1095. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chakravorty S, Simmons AM, Rowneki M, Parmar H, Cao Y, Ryan J, et al. The new Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra: improving detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and resistance to rifampin in an assay suitable for point-of-care testing. MBio. 2017;8 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00812-17. e00812-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicol MP, Workman L, Prins M, Bateman L, Ghebrekristos Y, Mbhele S, et al. Accuracy of Xpert Mtb/Rif Ultra for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018;37:e261–e263. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham SM, Cuevas LE, Jean-Philippe P, Browning R, Casenghi M, Detjen AK, et al. Clinical case definitions for classification of intrathoracic tuberculosis in children: an update. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(Suppl 3):S179–S187. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorman SE, Schumacher SG, Alland D, Nabeta P, Armstrong DT, King B, et al. Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance: a prospective multicentre diagnostic accuracy study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:76–84. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30691-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore DP, Klugman KP, Madhi SA. Role of Streptococcus pneumoniae in hospitalization for acute community-acquired pneumonia associated with culture-confirmed Mycobacterium tuberculosis in children: a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine probe study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:1099–1104. doi: 10.1097/inf.0b013e3181eaefff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oberhelman RA, Soto-Castellares G, Gilman RH, Caviedes L, Castillo ME, Kolevic L, et al. Diagnostic approaches for paediatric tuberculosis by use of different specimen types, culture methods, and PCR: a prospective case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:612–620. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70141-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owens S, Abdel-Rahman IE, Balyejusa S, Musoke P, Cooke RP, Parry CM, et al. Nasopharyngeal aspiration for diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:693–696. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.108308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franchi LM, Cama RI, Gilman RH, Montenegro-James S, Sheen P. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in nasopharyngeal aspirate samples in children. Lancet. 1998;352:1681–1682. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)61454-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabi I, Rachow A, Mapamba D, Clowes P, Ntinginya NE, Sasamalo M, et al. Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra assay for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in children: a multicentre comparative accuracy study. J Infect. 2018;77:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore HA, Apolles P, de Villiers PJ, Zar HJ. Sputum induction for microbiological diagnosis of childhood pulmonary tuberculosis in a community setting. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:1185–1190. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0681. i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walters E, van der Zalm MM, Demers AM, Whitelaw A, Palmer M, Bosch C, et al. Specimen pooling as a diagnostic strategy for microbiologic confirmation in children with intrathoracic tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019;38:e128–e131. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]