Abstract

Rationale: Administration of intravenous crystalloid solutions is a fundamental therapy for sepsis, but the effect of crystalloid composition on patient outcomes remains unknown.

Objectives: To compare the effect of balanced crystalloids versus saline on 30-day in-hospital mortality among critically ill adults with sepsis.

Methods: Secondary analysis of patients from SMART (Isotonic Solutions and Major Adverse Renal Events Trial) admitted to the medical ICU with an International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition, Clinical Modification System code for sepsis, using multivariable regression to control for potential confounders.

Measurements and Main Results: Of 15,802 patients enrolled in SMART, 1,641 patients were admitted to the medical ICU with a diagnosis of sepsis. A total of 217 patients (26.3%) in the balanced crystalloids group experienced 30-day in-hospital morality compared with 255 patients (31.2%) in the saline group (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.74; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.59–0.93; P = 0.01). Patients in the balanced group experienced a lower incidence of major adverse kidney events within 30 days (35.4% vs. 40.1%; aOR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.63–0.97) and a greater number of vasopressor-free days (20 ± 12 vs. 19 ± 13; aOR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.02–1.54) and renal replacement therapy–free days (20 ± 12 vs. 19 ± 13; aOR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.08–1.69) compared with the saline group.

Conclusions: Among patients with sepsis in a large randomized trial, use of balanced crystalloids was associated with a lower 30-day in-hospital mortality compared with use of saline.

Clinical trial registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02444988).

Keywords: sepsis, septic shock, balanced crystalloids, saline, lactated Ringer’s

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Balanced crystalloids may improve outcomes among all critically ill patients compared with saline.

What This Study Adds to the Field

In this study of critically ill adults with sepsis or septic shock enrolled in a trial comparing balanced crystalloids to saline, 30-day in-hospital mortality was lower with balanced crystalloids compared with saline. These findings suggest that balanced crystalloids may be more effective resuscitation fluids than saline for sepsis.

Sepsis is a common illness for which few effective therapies exist (1–3). In addition to prompt source control and antibiotic administration, infusion of intravenous crystalloid solutions is recommended for critically ill adults presenting with sepsis or septic shock (4).

Saline (0.9% sodium chloride) has historically been the most common intravenous crystalloid administered to critically ill adults with sepsis (5, 6). The supraphysiologic chloride concentration of saline may cause hyperchloremia (7–10), metabolic acidosis (7, 11–15), renal vasoconstriction (7), hypotension (14), and altered immune function (10, 16). Preclinical research has also suggested that sepsis resuscitation with high-chloride intravenous fluids may lead to increased inflammatory cytokines (16), hypotension (17), impairment of microcirculation (18), and increased mortality (14).

Compared with saline, balanced crystalloids, such as lactated Ringer’s solution and Plasma-Lyte A, contain an electrolyte composition more similar to plasma. Observational and before-and-after studies of patients with sepsis have suggested that using balanced crystalloids instead of saline may reduce rates of acute kidney injury (AKI) (19) and death (20). However, no large trials have compared balanced crystalloids to saline specifically among critically ill patients with sepsis, and the 2016 Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines recommend using either balanced crystalloids or saline for sepsis resuscitation (4).

The recent SMART (Isotonic Solutions and Major Adverse Renal Events Trial) trial compared balanced crystalloids to saline among critically ill adults and found that balanced crystalloids decreased the incidence of the composite outcome of death, new renal replacement therapy, or persistent renal dysfunction (21). In a prespecified subgroup analysis, the effect of balanced crystalloids compared with saline on the composite outcome appeared to be greater among patients with sepsis (odds ratio [OR], 0.80; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.67–0.94) than among patients without sepsis (OR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.86–1.07), although this difference did not achieve statistical significance (P value for the test of interaction = 0.06).

To better understand the comparative effectiveness of balanced crystalloids versus saline for adult patients with sepsis and the potential mechanisms by which fluid composition might affect mortality, we conducted a secondary analysis of the SMART dataset. We hypothesized that use of balanced crystalloids would result in a lower incidence of 30-day in-hospital mortality compared with saline among patients with sepsis. Some of the results of this study have previously been reported in the form of an abstract (22).

Methods

Study Design and Oversight

We conducted a secondary analysis of data from SMART (21), a pragmatic, nonblinded, cluster-randomized, multiple-crossover trial among critically ill adults admitted to five ICUs at Vanderbilt University Medical Center between June 2015 and April 2017. SMART was approved by the institutional review board at Vanderbilt University. Patients enrolled in SMART were assigned to receive either balanced crystalloids (the treating clinician’s choice of lactated Ringer’s solution or Plasma-Lyte A) or saline (0.9% sodium chloride) for intravenous fluid administration in the emergency department, operating room, and ICU according to fluid assignment for that month (Table E1 and Figure E1 in the online supplement). The subgroup of interest for this secondary analysis was patients admitted to the medical ICU with a diagnosis of sepsis. The SMART protocol, which identified patients with sepsis as an a priori subgroup of interest, was published before completion of enrollment (23).

Patient Population

SMART included all adult patients admitted to five ICUs, including a medical ICU, a trauma ICU, a neurologic ICU, a cardiovascular ICU, and a surgical ICU. Patients were identified as having a diagnosis of sepsis if any of the prespecified International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition, Clinical Modification System (ICD-10-CM) codes for sepsis were present in the first five billing codes for the hospitalization (see Supplemental Methods, Study Definitions, in the online supplement) (24, 25). The primary population for analysis in the current study was patients from the SMART dataset with a diagnosis of sepsis admitted to the medical ICU. Restriction to the medical ICU for the primary analysis enriched the population for patients whose management consisted primarily of fluid resuscitation and antibiotic delivery rather than operative intervention. Alternate patient populations, including all patients with a diagnosis of sepsis regardless of admitting ICU and alternative definitions of sepsis, were examined in sensitivity analyses, as described in Statistical Analysis.

Study Outcomes

The primary outcome for this analysis was death from any cause before the earlier of hospital discharge or 30 days after ICU admission (30-day in-hospital mortality). Mortality was selected as the primary outcome to be consistent with the outcomes of other large trials of interventions in sepsis and because death is an objective outcome that is important to clinicians and patients. In-hospital mortality was selected because the mechanistic effects of the intervention were anticipated to occur early after enrollment and because we did not have access to postdischarge vital status. Additional clinical outcomes included 60-day in-hospital mortality and ICU-free days, ventilator-free days, vasopressor-free days, and renal replacement therapy–free days during the 28 days after ICU admission (assigning a value of 0 for patients who died before 28 d). Additional renal outcomes included the primary outcome for the original trial (21): the proportion of patients with a major adverse kidney event within 30 days (MAKE30), defined as death, new receipt of renal replacement therapy, or persistent renal dysfunction at the first of hospital discharge or 30 days (see Supplemental Methods, Study Definitions, in the online supplement) (26–30); new receipt of renal replacement therapy; persistent renal dysfunction (final inpatient creatinine concentration ≥200% of baseline); and stage II or greater AKI by Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomescreatinine criteria (31). Additional exploratory outcomes included mean arterial pressure, vasopressor receipt and dose (Table E2), and plasma lactate concentration.

Statistical Analysis

To describe the detectable difference in the primary outcome using the available sample size we performed the following power calculation: analysis of data from the 1,641 medical ICU patients with a diagnosis of sepsis in the SMART dataset provided 80% power at an α-level of 0.05 to detect an unadjusted 6.0% absolute difference between the balanced crystalloids and saline groups in the primary outcome of 30-day in-hospital mortality, assuming a 30.0% incidence of 30-day in-hospital mortality in the saline group based on prior data (9, 21).

The primary analysis was an intention-to-treat comparison of 30-day in-hospital mortality between patients assigned to the balanced crystalloids group versus the saline group using a logistic regression model accounting for prespecified baseline covariates. We included the same set of prespecified baseline covariates used in the primary analysis of the original trial (21) (age, sex, race, source of admission, receipt of mechanical ventilation, and receipt of vasopressors) except for diagnosis of sepsis (because all patients in the current analysis had a diagnosis of sepsis) and diagnosis of traumatic brain injury (because no patients in the current analysis had a diagnosis of traumatic brain injury). Age was included in the model with a nonlinear relationship to the outcome using a restricted cubic spline with three knots. A two-sided P value less than 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

To evaluate the consistency and robustness of the findings of the primary analysis, we performed several secondary analyses (see Supplemental Methods in the online supplement).

-

1.

We compared additional outcomes (60-d in-hospital mortality; ICU-free, ventilator-free, and renal replacement therapy–free days; MAKE30; new receipt of renal replacement therapy; persistent renal dysfunction; stage II or greater AKI; and creatinine values) between the balanced crystalloids and saline groups in the primary study population using the same set of prespecified baseline covariates in logistic regression modeling for binary outcomes and proportional odds modeling for continuous outcomes.

-

2.

To evaluate alternative definitions of the study population, we repeated the primary analysis among all patients in the SMART dataset with a diagnosis of sepsis regardless of the ICU to which they were admitted (which added patients with sepsis in the surgical, trauma, cardiac, and neurologic ICUs to the patients in the primary analysis from the medical ICU). We also repeated the primary analysis excluding patients transferred from an outside hospital.

-

3.

To evaluate alternative methods of identifying patients with sepsis, we repeated the primary analysis in five additional cohorts. First, we examined patients admitted to the medical ICU with an ICD-10-CM diagnosis of sepsis for whom physician manual chart review confirmed that sepsis was the primary reason for ICU admission (for details of physician manual chart review see Supplemental Methods in the online supplement). Second, we performed physician manual chart review, blinded to ICD-10-CM diagnoses and study group assignment, for 1,000 randomly selected patient records to identify patients for whom sepsis was the primary reason for ICU admission. Among patients identified by physician manual chart review to have sepsis as the primary reason for ICU admission, we compared balanced crystalloids to saline. Third, we repeated the primary analysis among all patients admitted to the medical ICU with 1) any microbiology cultures drawn within 24 hours of enrollment, 2) any blood cultures drawn within 24 hours of enrollment, or 3) any positive blood cultures drawn within 24 hours of enrollment.

-

4.

We repeated the primary analysis with the additional covariate of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score at ICU admission, an established prognostic tool for patients with sepsis (32). We then repeated this analysis with additional covariates, including platelet count at baseline and history of diabetes, drug abuse, metastatic cancer, or AIDS.

-

5.

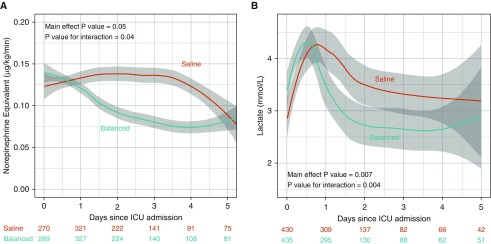

We compared mean arterial pressure, vasopressor receipt, and plasma lactate concentration over the 5 days after ICU admission using ordinary least squares regression with correction for correlated responses for the same patient using the Huber-White method (33, 34).

-

6.

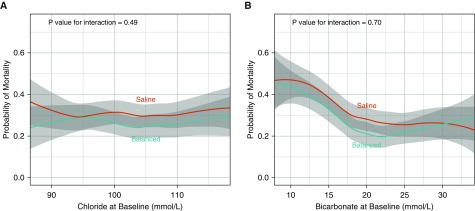

We assessed whether baseline plasma chloride concentration or bicarbonate concentration modified the effect of study group on 30-day in-hospital mortality using a binary logistic model testing for interaction.

Other between-group comparisons (baseline variables, fluid receipt, serum laboratory values, and indications for new renal replacement therapy) were made with the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and the Pearson’s chi-squared test for categorical variables. Continuous variables were presented as mean and SD, or as median and interquartile range; categorical variables were presented as frequency and proportion. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons because all subgroups were specified a prori (23), sepsis as a subgroup is supported by a strong biological rationale (14, 16, 35), and adjusting for multiple comparisons would increase the risk of type II error. Between-group differences in secondary and exploratory outcomes are reported with the use of point estimates and 95% CIs; however, the widths of the CIs have not been adjusted for multiplicity and should not be used to infer definitive differences in treatment effects between groups. All analyses were performed using R version 3.3.0 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

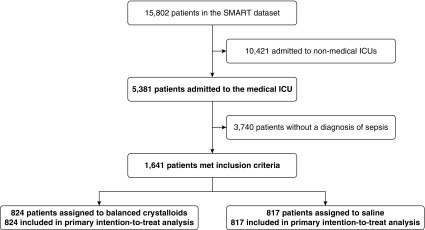

Among 15,802 patients in SMART, 1,641 (10.4%) were admitted to the medical ICU with a diagnosis of sepsis (Figure 1). The median age was 60 years old, and 55.0% were male. At ICU admission, 34.1% of patients were receiving vasopressors and 40.0% were receiving mechanical ventilation. Baseline characteristics were similar between patients assigned to balanced crystalloids (n = 824) and saline (n = 817) (Tables 1, E3, and E4).

Figure 1.

Derivation of the study cohort. Among 15,802 patients in SMART (Isotonic Solutions and Major Adverse Renal Events Trial), 1,641 were admitted to the medical ICU with a diagnosis of sepsis and were included in the primary analysis for the current study.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics at Baseline

| Patient Characteristics* | Balanced Crystalloids (n = 824) | Saline (n = 817) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 60 (48–69) | 60 (47–69) |

| Men, n (%) | 451 (54.7) | 448 (54.8) |

| White, n (%) | 617 (74.9) | 618 (75.6) |

| Weight, kg† | 78 (64–98) | 77 (64–94) |

| Chronic comorbidities, n (%)‡ | ||

| Pulmonary | 204 (24.8) | 214 (26.2) |

| Chronic heart failure | 200 (24.3) | 184 (22.5) |

| Chronic liver disease | 177 (21.5) | 198 (24.2) |

| Diabetes | 310 (37.6) | 279 (34.1) |

| Drug abuse | 38 (4.6) | 58 (7.1) |

| Metastatic malignancy | 78 (9.5) | 82 (10.0) |

| AIDS | 20 (2.4) | 21 (2.6) |

| Renal | ||

| Chronic kidney disease, stage III or greater§ | 169 (20.5) | 157 (19.2) |

| Prior renal replacement therapy receipt | 91 (11.0) | 92 (11.3) |

| Source of admission to the ICU, n (%) | ||

| Emergency department | 464 (56.3) | 458 (56.1) |

| Transfer from another hospital | 179 (21.7) | 180 (22.0) |

| Hospital ward | 154 (18.7) | 159 (19.5) |

| Operating room | 15 (1.8) | 8 (1.0) |

| Another ICU within the hospital | 9 (1.1) | 10 (1.2) |

| Outpatient | 3 (0.4) | 2 (0.2) |

| Sepsis as primary diagnosis at ICU admission, n (%)|| | 577 (70.0) | 573 (70.1) |

| Suspected source of infection, n (%)|| | ||

| Pulmonary | 189 (32.8) | 164 (28.6) |

| Urinary | 97 (16.8) | 94 (16.4) |

| Intraabdominal | 78 (13.5) | 83 (14.5) |

| Skin and soft tissue | 35 (6.1) | 36 (6.3) |

| Bloodstream | 22 (3.8) | 28 (4.9) |

| Other | 43 (7.4) | 51 (8.9) |

| Multiple sources suspected | 83 (14.4) | 87 (15.2) |

| No confirmed source | 30 (5.2) | 30 (5.2) |

| Vasopressors, n (%) | 289 (35.1) | 270 (33.0) |

| Vasopressor dose, norepinephrine equivalent, μg/kg/min¶ | 0.11 ± 0.27 | 0.11 ± 0.30 |

| Mean arterial pressure, mm Hg | 73 (62–87) | 74 (63–88) |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 324 (39.3) | 333 (40.8) |

| SOFA score** | 7 (5–10) | 8 (5–11) |

| White blood cell count, 103/μl†† | 13.9 (8.3–19.9) | 12.7 (8.3–19.0) |

| Platelet count, 103/μl†† | 189 (116–284) | 189 (107–280) |

| Hb, g/dl†† | 10.4 (8.7–12.2) | 10.2 (8/7–12.3) |

| Baseline creatinine, mg/dl‡‡ | 0.88 (0.67–1.21) | 0.87 (0.66–1.23) |

| Acute kidney injury, stage II or greater§§ | 207 (25.1) | 208 (25.4) |

Definition of abbreviation: SOFA = Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Continuous data are presented as median (25th percentile–75th percentile) or mean ± SD. Categorical data are presented as number (n) and percentage (%). The only significant difference in baseline characteristics between the two study groups was history of drug abuse (P = 0.03).

Information on weight at ICU admission was missing for 22 patients (8 in the balanced crystalloids group and 14 in the saline group).

Chronic comorbidities are defined by the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, a method for measuring patient comorbidity based on the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Edition, Clinical Modification System and the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition, Clinical Modification System (ICD-10-CM) diagnosis codes, found in administrative data (40, 41).

Chronic kidney disease stage III or greater is defined as a glomerular filtration rate less than 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 as calculated by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration Equation (42) using the patient’s baseline creatinine value.

Of 1,641 patients admitted to the medical ICU with a diagnosis of sepsis by ICD-10-CM criteria, physician manual chart review determined that the primary diagnosis at the time of ICU admission was sepsis for 1,150 patients (70.1%), 577 in the balanced crystalloids group and 573 in the saline group. For these patients, the suspected source of infection was determined.

Vasopressor dose represents the first value, in norepinephrine equivalents (Table E2), among patients receiving vasopressors on the day of ICU admission.

The SOFA score, also known as the Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment score (32), was calculated using data collected from the day of ICU admission. Baseline SOFA was missing for 5 patients (3 patients in balanced crystalloids group and 2 patients in saline group).

Baseline white blood cell count was missing for 7 (0.8%) patients in the balanced crystalloids group and 8 (1.0%) in the saline group. Baseline platelet count was missing for 1 (0.1%) patients in the balanced crystalloids group and 4 (0.5%) in the saline group. Baseline Hb was missing for 3 (0.4%) patients in the balanced crystalloids group and 5 (0.6%) in the saline group.

Baseline creatinine for the study was defined as the lowest plasma creatinine measured in the 12 months before hospitalization if available; otherwise, as the lowest plasma creatinine measured between hospitalization and ICU admission, using an estimated creatinine only for patients without an available plasma creatinine between 12 months before hospitalization and the time of ICU admission. The baseline creatinine was estimated for 107 (13.0%) patients in the balanced crystalloids group and 110 (13.5%) in the saline group.

Acute kidney injury stage II or greater is defined according to Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes creatinine criteria (43) as a first measured plasma creatinine value after ICU admission at least 200% of the baseline value or both 1) greater than 4.0 mg/dl and 2) increased at least 0.3 mg/dl from the baseline value.

Fluid Therapy and Electrolytes

Because fluid therapy in the emergency department was coordinated with the study ICU for most of the trial, in the 24 hours before ICU admission, patients in the balanced crystalloids group received a mean of 1,281 ± 67 ml of balanced crystalloids and 277 ± 29 ml of 0.9% sodium chloride, whereas patients in the saline group received a mean of 1,262 ± 59 ml of 0.9% sodium chloride and 266 ± 32 ml of balanced crystalloids (Table E5). Between ICU admission and hospital discharge or 30 days, patients in the balanced crystalloids group received a mean of 2,967 ± 4,498 ml of balanced crystalloids and 1,374 ± 3,514 ml of 0.9% sodium chloride. Patients in the saline group received a mean of 3,454 ± 4,982 ml of 0.9% sodium chloride and 629 ± 2,348 ml of balanced crystalloids (Table E6 and Figure E2). For patients in the balanced crystalloids group, 91.0% of the balanced crystalloid received was lactated Ringer’s solution and 9.0% of the balanced crystalloid received was Plasma-Lyte A. There were no significant differences between groups in receipt of nonisotonic crystalloids, albumin, or blood products (Table E7).

Patients in the balanced crystalloids group experienced lower plasma chloride concentrations and higher plasma bicarbonate concentrations than patients in the saline group (Figure E3). Fewer patients in the balanced crystalloids group had a chloride concentration greater than 110 mmol/L (36.8% vs. 46.4%; P < 0.001) or a bicarbonate concentration less than 20 mmol/L (60.8% vs. 69.3%; P < 0.001) (Table E8).

Primary Outcome

A total of 217 patients (26.3%) in the balanced crystalloids group died in the hospital within 30 days of ICU admission compared with 255 patients (31.2%) in the saline group (adjusted OR [aOR], 0.74; 95% CI, 0.59–0.93; P = 0.01) (Tables 2 and E9). The magnitude of the effect of balanced crystalloids versus saline on 30-day in-hospital mortality was similar in sensitivity analyses 1) including all patients in SMART with a diagnosis of sepsis regardless of admitting ICU, 2) excluding patients transferred from outside hospitals, 3) including only patients with a primary diagnosis of sepsis at medical ICU admission by physician manual chart review (with or without an ICD-10-CM code for sepsis), 4) including only patients with a microbiology culture drawn within 24 hours of ICU admission, 5) including only patients with a blood culture drawn within 24 hours of ICU admission, 6) including only patients with a positive blood culture drawn within 24 hours of ICU admission, and 7) controlling for additional covariates including baseline Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score, medical history, and platelet count (Table E10). Neither baseline plasma chloride (Figure 2A) nor bicarbonate concentration (see Figure 2B) modified the effect of assigned crystalloid on 30-day in-hospital mortality.

Table 2.

Clinical Outcomes

| Outcome* | n | Balanced Crystalloids (n = 824) | Saline (n = 817) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||||

| 30-d in-hospital mortality, n (%) | 1,641 | 217 (26.3) | 255 (31.2) | 0.74 (0.59 to 0.93) |

| Additional clinical outcomes | ||||

| 60-d in-hospital mortality, n (%) | 1,641 | 241 (29.2) | 269 (32.9) | 0.80 (0.64 to 1.01) |

| ICU-free days‡, median (IQR) | 1,641 | 23 (0 to 26) | 23 (0 to 26) | 1.15 (0.97 to 1.38) |

| Mean ± SD | — | 17 ± 11 | 16 ± 12 | — |

| Ventilator-free days‡, median (IQR) | 1,641 | 27 (0 to 28) | 26 (0 to 28) | 1.37 (1.12 to 1.68) |

| Mean ± SD | — | 19 ± 12 | 18 ± 13 | — |

| Vasopressor-free days‡, median (IQR) | 1,641 | 27 (0 to 28) | 27 (0 to 28) | 1.25 (1.02 to 1.54) |

| Mean ± SD | — | 20 ± 12 | 19 ± 13 | — |

| Renal replacement therapy–free days‡, median (IQR) | 1,641 | 28 (0 to 28) | 28 (0 to 28) | 1.35 (1.08 to 1.69) |

| Mean ± SD | — | 20 ± 12 | 19 ± 13 | — |

| Additional renal outcomes§ | ||||

| Major adverse kidney event within 30 d, n (%)|| | 1,641 | 292 (35.4) | 328 (40.1) | 0.78 (0.63 to 0.97) |

| Receipt of new renal replacement therapy, n (%)§ | 1,458 | 54 (7.4) | 75 (10.3) | 0.71 (0.48 to 1.04) |

| Final creatinine ≥200% of baseline, n (%) | 1,458 | 164 (22.4) | 162 (22.3) | 0.99 (0.76 to 1.28) |

| Stage II or greater AKI developing after ICU admission, n (%)¶ | 1,458 | 201 (27.4) | 231 (31.9) | 0.79 (0.63 to 1.00) |

| Creatinine**, mg/dl | 1,458 | |||

| Highest before discharge or 30 d | — | 1.58 (0.87 to 3.00) | 1.59 (0.93 to 2.97) | 0.95 (0.79 to 1.13) |

| Change from baseline to highest value | — | 0.18 (−0.07 to 1.13) | 0.23 (−0.07 to 1.20) | 0.99 (0.82 to 1.18) |

| Final value before discharge or 30 d | — | 0.94 (0.69 to 1.77) | 0.95 (0.71 to 1.80) | 0.97 (0.81 to 1.16) |

Definition of abbreviations: AKI = acute kidney injury; CI = confidence interval; IQR = interquartile range; OR = odds ratio.

Continuous data are presented as median (25th percentile to 75th percentile) or mean ± SD.

The adjusted OR is for the balanced crystalloids group compared with the saline group. Categorical outcomes are compared between study groups using a logistic regression model accounting for covariates (age, sex, race, source of admission, use of mechanical ventilation, and use of vasopressors). Continuous outcomes are compared between groups using a proportional odds model adjusting for the same variables.

ICU-free, ventilator-free, vasopressor-free, and renal replacement therapy–free days refer to the number of days alive and free from the specified therapy in the first 28 days after ICU admission. ORs greater than 1.0 indicate a better outcome (i.e., more days alive and free from the specified therapy) with balanced crystalloids compared with saline.

Receipt of new renal replacement therapy and additional renal outcomes based on creatinine measurements are among the 1,458 patients (733 in the balanced crystalloid group and 725 in the saline group) not known to have received renal replacement therapy before ICU admission.

Major adverse kidney events within 30 days is the composite of death, receipt of new renal replacement therapy, or final creatinine greater than or equal to 200% baseline, all censored at the first of hospital discharge or 30 days after ICU admission.

Stage II or greater AKI developing after ICU admission is defined using the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes creatinine criteria (31) as any creatinine value between ICU admission and discharge or 30 days that is 1) increased at least 0.3 mg/dl from a preceding postenrollment value and 2) at least 200% of the baseline value, at least 200% of a preceding postenrollment value, or at least 4.0 mg/dl; or new receipt of renal replacement therapy.

Among patients who had not received prior renal replacement therapy, plasma creatinine was measured a mean of 8.0 times between ICU admission and the first of discharge or 30 days in each group; plasma creatinine was not measured between ICU admission and the first of discharge or 30 days for 8 patients (1.0%) in the balanced crystalloid group and 9 patients (1.1%) in the saline group.

Figure 2.

Relationship between baseline chloride and bicarbonate concentration, study groups, and 30-day in-hospital mortality. The mean and 95% confidence interval (denoted by gray shading) for the probability of 30-day in-hospital mortality is displayed for patients in the balanced crystalloids group (blue) and in the saline group (red) relative to (A) baseline plasma chloride concentration and (B) baseline bicarbonate concentration, with locally weighted scatterplot smoothing. Although 30-day in-hospital mortality overall was lower in the balanced crystalloids group than the saline group, neither baseline chloride nor baseline bicarbonate concentration modified the effect of study group on in-hospital mortality.

Additional Outcomes

A total of 292 patients (35.4%) in the balanced crystalloids group experienced a MAKE30, compared with 328 patients (40.1%) in the saline group (aOR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.63–0.97) (see Table 2). New receipt of renal replacement therapy occurred for 54 patients (7.4%) in the balanced crystalloids group and 75 patients (10.3%) in the saline group (aOR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.48–1.04) (Table E11). A total of 201 patients (27.4%) in the balanced crystalloids group developed stage II or greater AKI after ICU admission compared with 231 (31.9%) patients in the saline group (aOR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.63–1.00). Patients in the balanced crystalloids group experienced more ventilator-free days, more vasopressor-free days, and more renal replacement therapy–free days than patients in the saline group (see Table 2).

Hemodynamics

Mean arterial pressure in the first 5 days after ICU admission did not differ significantly between the balanced crystalloids and saline groups (Figure E4). Despite similar doses of vasopressors at ICU admission, patients in the balanced crystalloids group received lower doses of vasopressors than patients in the saline group in the days following ICU admission (Figure 3A). Despite similar plasma lactate levels at ICU admission, patients in the balanced crystalloids group experienced lower plasma lactate concentrations in the days following ICU admission than patients in the saline group (see Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Vasopressor dose and plasma lactate concentration according to study group. The mean and 95% confidence interval (denoted by gray shading) for (A) dose of vasopressor in micrograms per kilogram per minute in norepinephrine equivalents for patients receiving vasopressors and (B) measured plasma lactate concentration for those with a measured value for the balanced crystalloids group (blue) and the saline group (red) for the first 5 days following ICU admission are displayed using locally weighted scatterplot smoothing. The number of patients with a measured value on each day is displayed for each group.

Discussion

This secondary analysis of a large clinical trial found that, compared with use of saline, use of balanced crystalloids was associated with a lower rate of 30-day in-hospital mortality for critically ill adults with sepsis. Use of balanced crystalloids was associated with a greater number of vasopressor-free days and renal replacement therapy–free days, though the mechanism remains unclear.

The results of this subgroup analysis are consistent with the overall results of SMART (21). SMART found that, among all critically ill adults, use of balanced crystalloids rather than saline decreased the incidence of a MAKE30 (OR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.82–0.99). This effect appeared to be potentially greater among patients with sepsis (OR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.67–0.94) than among patients without sepsis (OR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.86–1.07; P value for the test of interaction = 0.06). The current study adds to the overall SMART results by finding that, among patients with sepsis, crystalloid composition appeared to affect not only the composite outcome of a MAKE30 but also in-hospital mortality, vasopressor-free days, renal replacement therapy–free days, and other clinical outcomes. The difference in 30-day in-hospital mortality (15.7% relative risk reduction and 4.9% absolute risk reduction) observed with the use of balanced crystalloids compared with saline was consistent in numerous sensitivity analyses and was similar to the findings of two large, retrospective cohort studies among patients with sepsis, which reported relative risk reductions of in-hospital mortality with balanced crystalloids of 14.0% (20) and 14.1% (35), respectively.

The 2016 Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines recommend using either balanced crystalloids or saline for resuscitation of patients with sepsis (weak recommendation, low quality of evidence) (4). The guidelines also suggest monitoring plasma chloride concentration and other laboratory values to guide crystalloid choice. The current study directly compared balanced crystalloids to saline among patients with sepsis, observed a significant reduction in in-hospital mortality with balanced crystalloids, and found that baseline chloride and bicarbonate concentration did not modify the effect of study group on clinical outcomes, suggesting that plasma chloride monitoring may have limitations as a tool for choosing between intravenous crystalloid solutions.

The mechanism by which balanced crystalloids may result in better clinical outcomes than saline remains incompletely understood. One proposed mechanistic pathway is that saline induces hyperchloremia, which causes renal vasoconstriction and inflammation, AKI, renal replacement therapy, and death (36). However, in our study, baseline serum chloride concentration did not modify the effect of study group assignment on probability of in-hospital mortality. In addition, the effect of study group assignment on 30-day in-hospital mortality was larger than the effects on plasma creatinine and AKI.

Based on observed point estimates, the current study found that patients with sepsis assigned to balanced crystalloids rather than saline appeared to receive lower doses of vasopressors and experience lower plasma lactate concentrations after ICU admission. Two prior randomized trials among adults undergoing surgery have reported lower vasopressor requirements among patients assigned to receive balanced crystalloids compared with saline (37, 38). If these effects were confirmed in future studies of critically ill patients, additional research focusing on whether these effects are due to saline-associated acidosis on vasculature (14, 18) or release of inflammatory mediators (10, 16) could be undertaken.

The current study has several strengths. First, the crystalloid solution to which patients were assigned was determined by the original trial randomization, generating similar groups at baseline and minimizing indication bias. Second, patients with a diagnosis of sepsis were a prespecified subgroup of interest in the design of the original trial. Third, 30-day in-hospital mortality is an objective outcome relevant to clinicians and patients. Fourth, available data from more than 1,600 patients allowed greater statistical power to evaluate for a difference in in-hospital mortality than in any prior trial examining choice of crystalloid among patients with sepsis.

Our study also has important limitations. First, all patients were enrolled from a single academic center. Second, fluid group assignment was not blinded. Third, our primary analysis employed ICD-10 codes as a surrogate for prospective clinical assessment of sepsis. ICD-10 codes are not available at baseline and organ dysfunction arising after treatment allocation may influence ICD-10 code assignment. However, 1) agreement between this ICD-10–based approach and physician manual review is similar to the interrater reliability of two-physician manual chart review (39), 2) using ICD-10 codes identified a similar number of patients in each group with sepsis, and 3) our results were similar in sensitivity analyses using multiple other methods of identifying patients with sepsis that did not rely on ICD-10 codes. Fourth, ventilator-free, vasopressor-free, and renal replacement therapy–free days are sensitive to differences in in-hospital mortality between groups due to competing risk. Fifth, we observed a very large reduction in mortality with the use of balanced crystalloids instead of saline, particularly given the relatively small volumes of fluids that patients received on average, and our study is a secondary analysis of a clinical trial from a single site; therefore, our results are at risk of type I error. Sixth, many comparisons were made when looking at secondary and exploratory outcomes without adjustment; therefore, we did not present P values for these outcomes and they should be considered hypothesis-generating.

In conclusion, in this secondary analysis of 1,641 critically ill adults with sepsis from a large pragmatic trial, the use of balanced crystalloids was associated with a lower incidence of 30-day in-hospital mortality than saline. These results should be viewed as hypothesis-generating. Future research should examine the effect of crystalloid composition on mortality in sepsis and explore mechanisms linking crystalloid composition to clinical outcomes.

Footnotes

Supported by Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research grants UL1TR000445 and UL1TR002243 from National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/NIH, NHLBI grant HL087738-09 (J.D.C.), Vanderbilt Center for Kidney Disease (E.D.S.), National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant K23GM110469 (W.H.S), NIH grant R34HL105869 (T.W.R.), and NHLBI grants K12HL133117 and K23HL143053 (M.W.S.). The funding institutions had no role in 1) conception, design, or conduct of the study; 2) collection, management, analysis, interpretation, or presentation of the data; 3) preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or 4) the decision to submit for publication.

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: R.M.B., L.W., G.R.B., W.H.S., T.W.R., and M.W.S. Acquisition of data: R.M.B., L.W., T.D.C., N.I.K., J.D.C., J.P.W., J.M.E., D.W.B., J.L.S., G.R.B., W.H.S., T.W.R., and M.W.S. Analysis and interpretation of data: R.M.B., L.W., D.W.B., G.R.B., W.H.S., T.W.R., and M.W.S. Drafting of the manuscript: R.M.B. and M.W.S. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: R.M.B., L.W., T.D.C., N.I.K., J.D.C., J.P.W., J.M.E., D.W.B., J.L.S., E.D.S., G.R.B., W.H.S., T.W.R., and M.W.S. Statistical analysis: R.M.B., L.W., D.W.B., W.H.S., T.W.R., and M.W.S. Study supervision: G.R.B., W.H.S., T.W.R., and M.W.S. R.M.B., L.W., D.W.B., and M.W.S. had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. L.W. and D.W.B. conducted and are responsible for the data analysis.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201903-0557OC on August 27, 2019

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: for the SMART Investigators and the Pragmatic Critical Care Research Group

References

- 1.Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:840–851. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rhee C, Dantes R, Epstein L, Murphy DJ, Seymour CW, Iwashyna TJ, et al. CDC Prevention Epicenter Program. Incidence and trends of sepsis in US hospitals using clinical vs claims data, 2009-2014. JAMA. 2017;318:1241–1249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rowan KM, Angus DC, Bailey M, Barnato AE, Bellomo R, Canter RR, et al. PRISM Investigators. Early, goal-directed therapy for septic shock: a patient-level meta-analysis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2223–2234. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock. 2016. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:486–552. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Awad S, Allison SP, Lobo DN. The history of 0.9% saline. Clin Nutr. 2008;27:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammond NE, Taylor C, Finfer S, Machado FR, An Y, Billot L, et al. Fluid-TRIPS and Fluidos Investigators; George Institute for Global Health, The ANZICS Clinical Trials Group, BRICNet, and the REVA research Network. Patterns of intravenous fluid resuscitation use in adult intensive care patients between 2007 and 2014: an international cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0176292. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chowdhury AH, Cox EF, Francis ST, Lobo DNA. A randomized, controlled, double-blind crossover study on the effects of 2-L infusions of 0.9% saline and plasma-lyte® 148 on renal blood flow velocity and renal cortical tissue perfusion in healthy volunteers. Ann Surg. 2012;256:18–24. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318256be72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw AD, Bagshaw SM, Goldstein SL, Scherer LA, Duan M, Schermer CR, et al. Major complications, mortality, and resource utilization after open abdominal surgery: 0.9% saline compared to Plasma-Lyte. Ann Surg. 2012;255:821–829. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31825074f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Semler MW, Wanderer JP, Ehrenfeld JM, Stollings JL, Self WH, Siew ED, et al. SALT Investigators * and the Pragmatic Critical Care Research Group; SALT Investigators. Balanced crystalloids versus saline in the intensive care unit: the SALT randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:1362–1372. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201607-1345OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Volta CA, Trentini A, Farabegoli L, Manfrinato MC, Alvisi V, Dallocchio F, et al. Effects of two different strategies of fluid administration on inflammatory mediators, plasma electrolytes and acid/base disorders in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery: a randomized double blind study. J Inflamm (Lond) 2013;10:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-10-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams EL, Hildebrand KL, McCormick SA, Bedel MJ. The effect of intravenous lactated Ringer’s solution versus 0.9% sodium chloride solution on serum osmolality in human volunteers. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:999–1003. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199905000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasman H, Cinar O, Uzun A, Cevik E, Jay L, Comert B. A randomized clinical trial comparing the effect of rapidly infused crystalloids on acid-base status in dehydrated patients in the emergency department. Int J Med Sci. 2012;9:59–64. doi: 10.7150/ijms.9.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Kramer DJ, Pinsky MR. Etiology of metabolic acidosis during saline resuscitation in endotoxemia. Shock. 1998;9:364–368. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199805000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kellum JA. Fluid resuscitation and hyperchloremic acidosis in experimental sepsis: improved short-term survival and acid-base balance with Hextend compared with saline. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:300–305. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200202000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waters JH, Gottlieb A, Schoenwald P, Popovich MJ, Sprung J, Nelson DR. Normal saline versus lactated Ringer’s solution for intraoperative fluid management in patients undergoing abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: an outcome study. Anesth Analg. 2001;93:817–822. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200110000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kellum JA, Song M, Almasri E. Hyperchloremic acidosis increases circulating inflammatory molecules in experimental sepsis. Chest. 2006;130:962–967. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.4.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kellum JA, Song M, Venkataraman R. Effects of hyperchloremic acidosis on arterial pressure and circulating inflammatory molecules in experimental sepsis. Chest. 2004;125:243–248. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orbegozo D, Su F, Santacruz C, He X, Hosokawa K, Creteur J, et al. Effects of different crystalloid solutions on hemodynamics, peripheral perfusion, and the microcirculation in experimental abdominal sepsis. Anesthesiology. 2016;125:744–754. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yunos NM, Bellomo R, Hegarty C, Story D, Ho L, Bailey M. Association between a chloride-liberal vs chloride-restrictive intravenous fluid administration strategy and kidney injury in critically ill adults. JAMA. 2012;308:1566–1572. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.13356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raghunathan K, Shaw A, Nathanson B, Stürmer T, Brookhart A, Stefan MS, et al. Association between the choice of IV crystalloid and in-hospital mortality among critically ill adults with sepsis*. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:1585–1591. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Semler MW, Self WH, Wanderer JP, Ehrenfeld JM, Wang L, Byrne DW, et al. SMART Investigators and the Pragmatic Critical Care Research Group. Balanced crystalloids versus saline in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:829–839. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1711584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown RM, Wanderer JP, Ehrenfeld JM, Stollings JL, McKown AC, Bernard GR, et al. SALT Investigators; Pragmatic Critical Care Research Group. Balanced crystalloids versus saline for adults with sepsis or septic shock [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:A6188. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Semler MW, Self WH, Wang L, Byrne DW, Wanderer JP, Ehrenfeld JM, et al. Isotonic Solutions and Major Adverse Renal Events Trial (SMART) Investigators; Pragmatic Critical Care Research Group. Balanced crystalloids versus saline in the intensive care unit: study protocol for a cluster-randomized, multiple-crossover trial. Trials. 2017;18:129. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-1871-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ICD-10-CM official guidelines for coding and reporting [accessed 2018 May 3] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/icd/10cmguidelines_2017_final.pdf.

- 25.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Hospital inpatient quality reporting program measures: International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition, Clinical Modification System (ICD-10-CM) draft code sets [accessed 2018 May 3] Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/Downloads/HIQR-ICD9-to-ICD10-Tables.pdf.

- 26.Semler MW, Rice TW, Shaw AD, Siew ED, Self WH, Kumar AB, et al. Identification of major adverse kidney events within the electronic health record. J Med Syst. 2016;40:167. doi: 10.1007/s10916-016-0528-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaw A. Models of preventable disease: contrast-induced nephropathy and cardiac surgery-associated acute kidney injury. Contrib Nephrol. 2011;174:156–162. doi: 10.1159/000329387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palevsky PM, Molitoris BA, Okusa MD, Levin A, Waikar SS, Wald R, et al. Design of clinical trials in acute kidney injury: report from an NIDDK workshop on trial methodology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:844–850. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12791211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kashani K, Al-Khafaji A, Ardiles T, Artigas A, Bagshaw SM, Bell M, et al. Discovery and validation of cell cycle arrest biomarkers in human acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2013;17:R25. doi: 10.1186/cc12503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kellum JA, Zarbock A, Nadim MK. What endpoints should be used for clinical studies in acute kidney injury? Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:901–903. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4732-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120:c179–c184. doi: 10.1159/000339789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonça A, Bruining H, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related organ failure assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure: on behalf of the working group on sepsis-related problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huber PJ. The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under nonstandard conditions. In: Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability. Vol. 1: Statistics. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1967. pp. 221–233. [Google Scholar]

- 34.White H. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica. 1980;48:817–838. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raghunathan K, Bonavia A, Nathanson BH, Beadles CA, Shaw AD, Brookhart MA, et al. Association between initial fluid choice and subsequent in-hospital mortality during the resuscitation of adults with septic shock. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:1385–1393. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Filis C, Vasileiadis I, Koutsoukou A. Hyperchloraemia in sepsis. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8:43. doi: 10.1186/s13613-018-0388-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Potura E, Lindner G, Biesenbach P, Funk G-C, Reiterer C, Kabon B, et al. An acetate-buffered balanced crystalloid versus 0.9% saline in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing cadaveric renal transplantation: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2015;120:123–129. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfortmueller CA, Funk G-C, Reiterer C, Schrott A, Zotti O, Kabon B, et al. Normal saline versus a balanced crystalloid for goal-directed perioperative fluid therapy in major abdominal surgery: a double-blind randomised controlled study. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2017.11.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunatchik A, Semler MW, Rice TW, Casey JD Pragmatic Critical Care Research Group. Accuracy of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services ICD-10-CM codes in identifying sepsis among critically ill adults [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:A5016. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi J-C, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, III, Feldman HI, et al. CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2012;2:8. [Google Scholar]