Abstract

Objectives

Data collected during routine clinic visits are key to driving successful quality improvement in clinical services and enabling integration of research into routine care. The purpose of this study was to develop a standardized core dataset for juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) (termed CAPTURE-JIA), enabling routine clinical collection of research-quality patient data useful to all relevant stakeholder groups (clinicians, service-providers, researchers, health service planners and patients/families) and including outcomes of relevance to patients/families.

Methods

Collaborative consensus-based approaches (including Delphi and World Café methodologies) were employed. The study was divided into discrete phases, including collaborative working with other groups developing relevant core datasets and a two-stage Delphi process, with the aim of rationalizing the initially long data item list to a clinically feasible size.

Results

The initial stage of the process identified collection of 297 discrete data items by one or more of fifteen NHS paediatric rheumatology centres. Following the two-stage Delphi process, culminating in a consensus workshop (May 2015), the final approved CAPTURE-JIA dataset consists of 62 discrete and defined clinical data items including novel JIA-specific patient-reported outcome and experience measures.

Conclusions

CAPTURE-JIA is the first ‘JIA core dataset’ to include data items considered essential by key stakeholder groups engaged with leading and improving the clinical care of children and young people with JIA. Collecting essential patient information in a standard way is a major step towards improving the quality and consistency of clinical services, facilitating collaborative and effective working, benchmarking clinical services against quality indicators and aligning treatment strategies and clinical research opportunities.

Keywords: juvenile idiopathic arthritis, core dataset, quality improvement, collaboration, safety, patient reported outcomes

Rheumatology key messages

CAPTURE-JIA is the first standardized core dataset for juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

CAPTURE-JIA enables routine clinical collection of a standardized research-quality dataset in juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

CAPTURE-JIA will facilitate collaborative and effective care and alignment of treatment strategies and clinical research opportunities.

Introduction

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is an umbrella term for a heterogeneous group of childhood-onset arthritides, sub-divided into seven disease subtypes according to clinical features at disease onset [1, 2]. JIA is one of the most common chronic inflammatory illnesses of childhood, affecting at least 15 000 children and young people (CYP) across the UK [3]. JIA can have a major impact on physical, psychological and visual function, health-related quality of life and social/educational attainments, affecting both children and their families throughout childhood and into adult life [4].

JIA consists of a very variable group of diseases in terms of presentation, disease course and longer-term outcomes and it is increasingly clear that a significant proportion of patients do not achieve inactive disease within the first 1–2 years of follow-up [5]. The probability of achieving inactive disease is known to depend upon the disease subtype and diagnostic delay prior to presentation [6, 7] and a higher burden of disease activity is associated with poorer functional outcomes [7]. Timely access to high-quality specialist paediatric rheumatology (PRh) care is therefore key to reducing the burden of disease-related complications [8]. More recently, a positive association has been demonstrated between low patient global assessment and poorer functional outcomes, even in the absence of clinically identifiable inflammatory arthritis [9]. This highlights the importance of understanding and addressing the patient/parent perspective as part of high quality clinical care.

Universal access to high quality clinical care is therefore an important aspiration of the UK PRh community. High quality clinical care requires provision of safe, effective, patient centred, timely, efficient and equitable services, investigations and treatments that increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge [10]. Furthermore, all patients and families must be treated in a humane and culturally appropriate manner, have access to high quality and relevant clinical studies and be invited to participate fully in clinical decisions.

Data collected during routine clinic visits are key to understanding and improving quality of care and enabling integration of research into routine clinical practice. In 2014, a multicentre clinical audit of 14 UK PRh providers demonstrated wide variability in collection and documentation of clinical data; the variation applied to the data items collected and their definitions [11]. The same data item was often collected more than once and documented in multiple places, with significant overlap between datasets requested by different stakeholder groups.

This variation in data collection likely relates to a long-standing uncertainty around the optimal definition of disease states in JIA. In the 1990s, a lack of standardization in the reporting of JIA clinical trials led to the development of the JIA Core Outcome Variables [12]. More recently, a wide range of composite indices defining disease states and outcomes have been developed specifically for JIA [13–17] and these definitions are becoming central to modern clinical trial design and routine clinical care [18]. A JIA clinical dataset would enable uniform definition and clinical collection of these key data items.

In 2013, a multicentre UK audit against the British Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology (BSPAR)/Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance (ARMA) Standards of Care (SOC) for CYP with JIA [19] demonstrated considerable variation in service delivery and time to access specialist care [20]. The same audit highlighted the need for consensus in agreed and measurable JIA-specific quality indicators, reflecting current clinical practice and including both clinician-reported and patient/parent reported outcome measures, to enable standardization of clinical data collection.

Prior to commencement of this project, the Arthritis Research UK/Medicines for Children Research Network PRh Clinical Studies Group (PRh CSG) identified a number of different groups working on PRh-specific core datasets. Datasets under development included measures of clinical outcome (including disease activity, damage assessment and uveitis), measures of treatment response (including safety), patient-reported outcome measures and patient-reported experience measures, and measures relating to service delivery and the BSPAR standards of care [19]. This project arises out of the identification within the PRh CSG that despite the likely overlap between datasets, there was no coordination between the study groups and considerable duplication of work for clinical teams collecting multiple datasets.

The purpose of this study is therefore to develop a standardized core dataset for JIA, enabling collection of a sustainable source of research-quality patient data, including outcomes of relevance to patients/families, in all clinical settings.

The agreed, clinically relevant and feasible standardized ‘core dataset’ will be termed CAPTURE-JIA (Consensus derived, Accessible (information), Patient-focused, Team-focused, Universally-collected (UK), Relevant to all and containing Essential data items).

Aims and objectives

The aim of this project was to develop an agreed core dataset for JIA (termed CAPTURE-JIA) meeting the needs of key stakeholder groups (consumers, clinical teams, service providers, health care planners and PRh research teams).

In order to address the heterogeneity of purpose of the proposed CAPTURE-JIA dataset, specific objectives included the following. First, identification and inclusion of representatives from pre-existing UK PRh groups engaged in developing relevant datasets. Second, identification of key clinical status data items: a unified, standardized clinical ‘core dataset’ for JIA, including key data items collected during a standard clinical encounter. Third, identification of key service delivery data items: clinician and patient reported data items required for National Health Service (NHS) Specialist Commissioning and national audit of JIA. Finally, development of the CAPTURE-JIA dataset: to consist of a de-duplicated list of essential service delivery and clinical status data items along with standard data definitions and validation rules.

Methods

Identification and inclusion of relevant pre-existing teams

Existing UK groups engaged in developing datasets were identified through a series of email communications with key clinical and research groups (BSPAR membership list, the PRh CSG and a number of personal networks). Each individual identified in this way was invited to share his/her work with standardized information collected on a pre-prepared template, and invited to participate in a final facilitated consensus workshop (May 2015).

Clinical status data items

Development of governance structure

Establishment of a consultative governance structure (Project Steering Group and Project Expert Group) including representatives from pre-existing UK PRh groups engaged in developing relevant datasets. In summary, first a multidisciplinary Project Steering Group (n = 6) comprising: academic lead (chair), one researcher/project manager, three clinicians/clinical academics, one patient/carer, representing JIA patient groups and other attendees by invitation, as required. Second, a larger multidisciplinary Project Expert Group (n = 44 including six members of the steering group and clinicians/clinical academics leading other projects on core datasets) comprising: clinicians/clinical academics (33), specialist nurses (4), specialist physiotherapist (1), patients/carers, representing JIA patient groups (5) and academic researchers (1).

Clinical status dataset review and identification of possible data items for Delphi

15 NHS trusts across the UK were contacted with the aim of collating a long list of candidate data items for inclusion in the dataset. The long list included all data items on clinical data collection sheets/clinical databases.

Because the additional purpose of the CAPTURE-JIA dataset is to inform future research, we collaborated with the Childhood Arthritis Response to Treatment (CHART) Consortium, funded via a Medical Research Council partnership award, which was in the process of aligning the data collected in four UK-based research projects (Childhood Arthritis Prospective Study (CAPS), Childhood Arthritis Response to Medication Study (CHARMS) and two drug registries, BSPAR‐Etanercept (BSPAR‐Et) and Biologics in Children with Rheumatic Diseases (BCRD)). Those CHART items relating to clinical status were added to the preliminary list.

Similar data items were combined, and two academic members of the steering group agreed the de-duplications, with expert clinical advice for some of the more technical items. Data items were included in the next stage if they were collected by four or more (>20%) of the 15 NHS trusts.

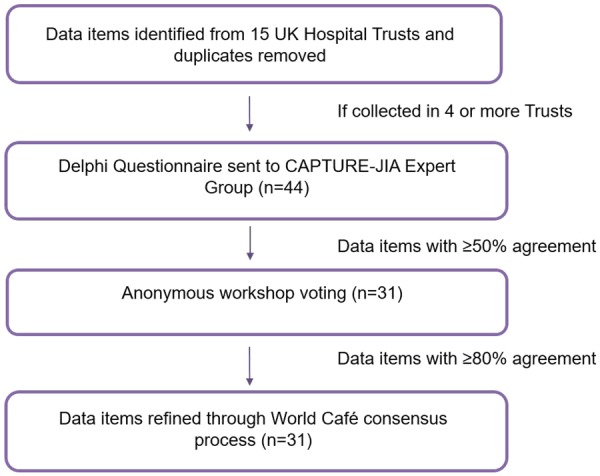

A two-stage Delphi process was then utilized to enable the expert group to reduce and refine the list of data items for inclusion in CAPTURE-JIA [21]. The first stage required completion of an online survey to refine the list of data items and the second stage was a face-to-face workshop (overview of clinical status data item derivation in Fig. 1) . Participants received travel and accommodation expenses only.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart summarizing the methodology used to develop the CAPTURE-JIA clinical status dataset

Delphi survey

The expert group were asked, via online consultation, to rate the importance of each proposed data item to the final CAPTURE- JIA dataset using a scale from 0 (not relevant) to 5 (essential).

Data items were categorized into bins according to the proportion of ratings ranked 4 or 5 (⩾70% vs 50–69% vs <50% responses). Items rated 4 or 5 by 50% or more of respondents were included in the workshop.

Delphi workshop

The expert group was invited to a two-day facilitated workshop with two main aims: to agree the clinical status dataset for inclusion in CAPTURE-JIA; and to agree the definition, shared meaning and manner of assessment of selected data items.

The first day of the workshop consisted of four rounds of anonymous voting using TurningPoint software from Turning Technologies and handheld voting devices, led by an independent facilitator. Participants were asked to vote on: ‘Should <data item> be included in CAPTURE-JIA Y/N’ according to their personal understanding of the importance of that data item.

Round 1. The first round of voting was for all data items with a score in the prior Delphi survey of ⩾70% (i.e. ⩾70% of respondents rated the item as a 4 or 5 in terms of relevance). Items achieving 80% or more of YES votes in this first round were included in CAPTURE-JIA and items achieving ⩾70% but <80% YES votes were benched for further discussion in Round 3. The chosen thresholds are purposefully similar to previous consensus-based studies in this field [22, 23].

Round 2. The second round of voting was for items with 50–69% of respondents rating the item as a 4 or 5 in terms of relevance in the prior Delphi survey. This time a brief 8-min facilitated discussion was held for each item, allowing time for 4 min of discussion for/against inclusion. Voting then took place as above on whether the item should be included in the dataset. Again, items achieving 80% or more of YES votes were included in CAPTURE-JIA and items achieving ⩾70% but <80% YES votes were benched for further discussion in Round 3.

Round 3. Items achieving between 70 and 80% YES votes in Rounds 1 and 2 were discussed and voted on as previously described. Items achieving 80% or more YES votes were included in CAPTURE-JIA and other items were discarded.

Round 4. Active and limited joint counts may be collected and documented in a number of different ways (e.g. active joint count vs swollen and tender joint count documented via tables or mannequins). Due to this complexity, joint counts were included in a separate round of voting with a dedicated discussion.

The second day of the meeting was run as a World Café event (http://www.theworldcafe.com/method.html). World Café works as a series of progressive rounds (welcome-starter-main-dessert), in which participants move from one table to the next to refine the work of the previous groups. Each table has a facilitator who remains at one table to explain the task to successive groups. The aim of the World Café was to describe and name each data item, refine a pre-prepared definition, identify options for the item (e.g. rheumatoid factor: positive/negative/not tested), suitable clinic visits and any related data items. Workshop attendees were divided into five groups of six or seven experts. Each group worked with an independent facilitator on separate tables on separate tasks (refining six to eight data items per table) and circulated around every table. Round 4 data items (joint counts) were considered too complex for the World Café.

Refining data items and final approval

Each table facilitator summarized discussions, with summaries cross-checked for accuracy and fairness by the Steering Group project managers/researchers. This enabled further refinement and the addition of validation rules to data items, with Expert Group advice sought as necessary. The table of data items (including definitions, format, validation ranges, options and when they will be collected) was reviewed and amended initially by members of the Steering Group. The clinical status dataset was then sent out for further review by the wider Expert Group with feedback incorporated prior to final inclusion in CAPTURE-JIA.

Service delivery data items

A JIA national audit tool was developed in parallel with this process, with considerable overlap between co-authors [22]. The audit tool has been described previously and comprises eleven service-related quality measures, relating to access to care and clinical research, clinic organization, uveitis status and medication use, assessed against disease-related outcome measures (the three-variable Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score or cJADAS) [17] and presence/absence of uveitis and a JIA-specific patient-reported outcome measure and patient-reported experience measure. The patient and clinician-reported national audit data items fully encompass the service delivery data items in CAPTURE-JIA and as such will not be further outlined here.

Results

Clinical status data items

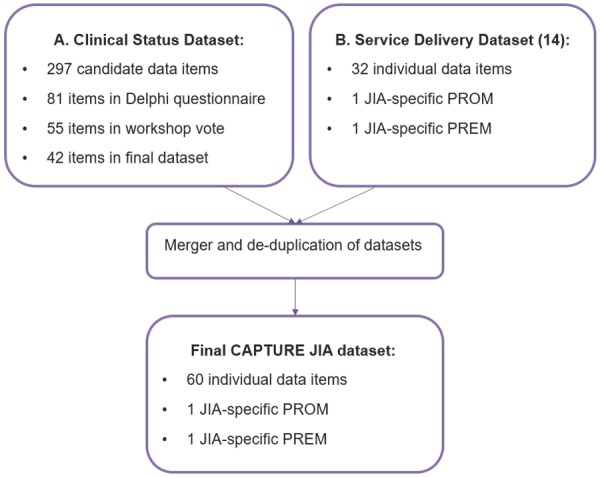

Fig. 2 shows a flow chart summarizing the derivation of the final list of data items included in the CAPTURE-JIA dataset.

Fig. 2.

Flow chart summarizing the derivation of the CAPTURE-JIA dataset

Clinical status dataset review

297 individual data items (after consolidating (de-duplicating) duplicate or very closely related data items) were identified from one or more of the 15 NHS Trusts and PRh research projects. Eighty-one data items appeared on >4 occasions and were therefore included in the Delphi survey.

Delphi survey

The Round 1 electronic Delphi survey was completed by 36/44 (82%) of the Expert Group. Data items with relevance rated 4 or 5 by >50% respondents (a total of 55 data items) were carried forward into the Delphi workshop. In summary: data items were rated 4 or 5 in terms of relevance by ⩾70% respondents; 19 data items were rated 4 or 5 in terms of relevance by 50–69% respondents; and 26 data items were rated 4 or 5 by <50% respondents and did not progress to the workshop.

Delphi workshop

Thirty-three (75%) Expert Group members attended the two-day workshop held in May 2015. Thirty-one (94%) of the workshop attendees had completed the online Delphi survey; a further five Expert Group members had completed the survey but were unable to attend the workshop.

Day 1. At the start of the meeting, the group agreed a cut-off of 80% agreement to be the minimum requirement for inclusion of a data item in the final dataset.

Voting on the data items for inclusion in the clinical status dataset was conducted in four rounds separating the data items with the highest agreement in the prior Delphi survey (Round 1: ⩾70%, n = 32 items) from those with lower agreement (Round 2: 50–69%, n = 17 items). Ten data items were voted on in Round 3 (re-voting) and six data items were included in Round 4 (joint data). As a result of these voting rounds and discussions, a total of 33 data items were accepted into the World Café round on the second day of the workshop (Fig. 2).

Day 2. Each of the 33 data items was discussed in detail during the World Café, with discussion points and particular concerns documented by each facilitator as the groups moved around the tables. A small number of data items discussed on day 1 required further discussion and amendment. Further changes to the dataset included: two items, identified as challenging to define and collect, were split into two (uveitis became two items and ‘drug start date’ was split into ‘date of decision to treat/change treatment’ and ‘date treatment started/date of single treatment’); plasma viscosity was added as an alternative to ESR at the request of some members to reflect availability of tests in their area; ANA had been very close to threshold in rounds 2 and 3 and was subject to further discussion. Following a further vote, ANA was added back to the dataset; the physician global assessment is challenging to define and employ in children with systemic onset JIA. A specific systemic JIA global assessment was added to the dataset; and four joint count data items (active joint count, swollen joint count, tender joint count and limited joint count) were accepted following detailed discussions with clinician representatives. It was agreed that the limited joint count and either the active joint count or both the swollen and tender joint counts should be collected.

The final clinical status dataset therefore consisted of 42 data items. Following the consensus meeting, a table of data items (including agreed definitions, format, validation ranges and time-points for collection) was drawn up by the project manager (G.A./J.C.) and reviewed by the Steering Group. Following a number of minor amendments (relating to definitions and validation ranges), the clinical status dataset was sent to the Expert Group for review with relevant feedback incorporated prior to final approval.

Final CAPTURE-JIA dataset

The service delivery data items [22] and clinical status data items were merged and de-duplicated to form the definitive CAPTURE-JIA dataset (Table 1). Following approval by the Steering and Expert Groups, the dataset contains 59 discrete data items as well as the novel JIA-specific patient-reported outcome measure and patient-reported experience measure (n = 61).

Table 1.

List of data items included in the CAPTURE-JIA dataset

| Data Item (n = 62) | Visit |

|---|---|

| 1.1 NHS number of patient (Scotland: CHI number; Northern Ireland: H&C number)a | All |

| 1.2 Date of attendance / visit datea | All |

| 2.1 Gender | First |

| 2.2 Date of birtha | First |

| 2.3 Ethnicity | First |

| 3.1 Height | All |

| 3.2 Weight | All |

| 4.1.A Active joint assessmenta | All |

| 4.1.B Swollen joint assessmenta | All |

| 4.1.C Tender joint assessmenta | All |

| 4.2 Limited joint assessment | All |

| 4.3 Physician global assessmenta | All |

| 4.4 Patient/Parent Global Assessment of overall well-beinga | All |

| 4.5.A CHAQ/HAQ (final numeric score)a | All |

| 4.5.B CHAQ multiple choice questions | All |

| 4.5.C CHAQ yes/no questions | All |

| 4.6.A ESRa | All |

| 4.6.B Plasma viscositya | All |

| 4.7 CRP | All |

| 4.8 Pain VAS | All |

| 4.9 Date COVs assesseda | All |

| 5.1 RF +/− | First/clinically indicated |

| 5.2 HLA B27 +/− | Once if clinically indicated |

| 5.3 ANA +/− | First/clinically indicated |

| 6.1 Date of symptom onset | First |

| 6.2 ILAR sub-typea | First/clinically indicated |

| 6.3 Date of diagnosis | First/clinically indicated |

| 6.4 Relevant co-morbidities | First/clinically indicated |

| 6.5 Morning stiffness of joints | All |

| 6.6 Leg length discrepancy | First/clinically indicated |

| 6.7.A Systemic features | First/clinically indicated |

| 6.7.B Systemic JIA Global Assessment | First/clinically indicated |

| 6.8.A Uveitis history | All |

| 6.8.B Uveitis status at most recent eye examinationa | All |

| 7.1 Medication namea | All |

| 7.2.A Date of decision to treat or change treatmenta | All |

| 7.2.B Date treatment started / date of single treatmenta | All |

| 7.3 Dose | All |

| 7.4 Frequency | All |

| 7.5 Routea | All |

| 7.6 Date medication stopped or changeda | All |

| 7.7 Reason for stopping or changing medicationa | All |

| 7.8 Joints injected with intra-articular steroids | All |

| 7.9 Adverse drug reactions | All |

| 8.1 Date of referral letter being received in rheumatology departmenta | First |

| 8.2.A Date of first appointment offered in a rheumatology clinica | First |

| 8.2.B Date of first appointment in a rheumatology clinica | |

| 8.3 Did the decision to treat with steroid injection specify a dedicated Paediatric GA list?a | All |

| 8.4 Date of first eye screena | All |

| 8.5 Date patient was counselled before starting methotrexatea | All |

| 8.6 Date patient was counselled before starting a biologica | All |

| 8.7 Clinic type / organisationa | All |

| 8.8.A Is the patient eligible for the recruitment to the BSPAR Etanercept Cohort Study?a | All |

| 8.8.B Has the patient been recruited to the BSPAR Etanercept Cohort Study?a | All |

| 8.9.A Is the patient eligible for recruitment to the BCRD study?a | All |

| 8.9.B Has the patient been recruited to the BCRD study?a | All |

| 8.10 Date form completed (CHAQ/PREM/PROM) | All |

| 8.11 Form type (patient or parent) (CHAQ/PREM/PROM) | All |

| 8.12 Completed by (CHAQ/PREM/PROM) | All |

| 8.13 Time taken to complete form (CHAQ/PREM/PROM) | All |

| 8.14 JIA-specific PREM questionsa [22] | All |

| 8.15 JIA-specific PROM questionsa [22] | All |

Data item also included in the service delivery dataset (national audit dataset) [22].

BCRD: Biologics for Children with Rheumatic Diseases; BSPAR: British Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology; CHAQ: Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire; COV: core outcome variable; GA: general anaesthesia; NHS: National Health Service; PREM: patient-reported experience measure; PROM: patient-reported outcome measure; VAS: visual analogue score.

Relevant definitions, formats and validation rules are detailed in Supplementary Table 1 (the CATURE JIA Data Dictionary) (available at Rheumatology online). The CATURE JIA Data Dictionary is likely to be subject to further changes over time. For the latest version please email Flora McErlane (flora.mcerlane@nuth.nhs.uk).

Discussion

This paper describes the highly consultative approach underlying development of the first ‘core dataset’ of data items for routine clinical collection in JIA patients. The final approved CAPTURE-JIA dataset consists of 62 discrete and defined data items. Thirteen data items require collection once only and a further nine are split into one or more sub-items, ensuring that the everyday clinical dataset is both clinically feasible and complete enough to answer important clinical, service provision and research questions. CAPTURE-JIA was designed for use in the UK, but we believe it relevant to the international context, potentially facilitating more complete international datasets.

A key strength of this study is the collaborative nature and emphasis on inclusion of representatives from all stakeholder groups, including patient/carer representatives, throughout the decision-making process. Collecting essential patient information in such a standard way will benefit key stakeholders (namely patients/families, clinicians, service providers, researchers and commissioners), facilitating shared decision making, collaborative and effective working, benchmarking of clinical services against quality indicators and aligning treatment strategies and clinical research opportunities.

An important challenge was the need to balance inclusion of all essential data items while maintaining clinical feasibility. The initial phase of the study, wherein a large number of NHS Trusts were visited, minimized the risk of missing important data items. A two-stage Delphi process, involving a large number of experts, enabled refinement and agreement of the final CAPTURE-JIA dataset.

Although voting was anonymous throughout the Delphi process, workshop discussions prior to the final three rounds of voting may have impacted on decision making at an individual level. However, discussion of certain data items can be essential during a consensus process if participants’ understanding is variable. Such discussion is standard practice among consensus-based techniques such as the Nominal Group Technique, which requires feedback on all ideas before a second round of voting [24]. In this study, a number of clinical data items required explanation for both consumer and research representatives. Discussion aided understanding to Stage 2 and ensured that all voices could be heard. The World Café methodology was employed to give structure to the process and minimize bias. TurningPoint technology enabled voting anonymity.

Although the dataset was designed by clinical teams and consumers, the true clinical feasibility of the proposed CAPTURE-JIA dataset is not yet known. The next step in this process is to develop a pilot study exploring the feasibility and acceptability of collecting the CAPTURE-JIA dataset in the routine clinical environment. The proposed pilot study will provide a further opportunity for the clinical community to review and comment on the dataset. We recognize that the CAPTURE-JIA dataset is likely to evolve over time. The clinical care of CYP with JIA is evolving rapidly and novel outcome measures may become increasingly important over time. Preliminary new classification criteria for JIA are under development and the CAPTURE JIA dataset may require further modification as these criteria are validated over the next few years [25]. We anticipate regular review meetings to explore and update the dataset if necessary.

Although CAPTURE-JIA was developed for use primarily in the UK, routine implementation of CAPTURE JIA may be of value in other countries and, similar to the BSPAR Standards of Care [19], may become an exemplar driving development of similar datasets for other chronic diseases of childhood. Direct benefits to patient care and clinical research may include: ensuring outcomes of relevance to patients/families are collected as routine; improved quality and consistency of services that patients can access in a nationally and internationally equitable manner; embedding extractable research-quality data collection in routine clinical care for immediate use within local units and national/international projects (facilitating responses to clinical trial feasibility requests and driving development of electronic patient record systems); maximising opportunities for collaborative research and enabling comparison between cohort studies undertaken in different countries; and reducing the burden on patients, health care professionals and researchers by eliminating duplication.

Although a national audit tool has been developed for JIA [22], there is currently no UK mechanism to collect national audit data. Routine collection of the CAPTURE-JIA dataset will allow benchmarking of services and an immediate national audit programme. Many hospitals are now developing electronic patient record systems and the CAPTURE JIA dataset is ideally suited to incorporation within these local systems. For CAPTURE-JIA to reach its full potential, a suitable platform to extract data from electronic patient record systems is needed. An interim period of collecting the CAPTURE-JIA dataset alongside routine clinical data may be needed in some centres. The purpose of the Data Dictionary (Supplementary Table 1, available at Rheumatology online) is to support the development of software for capturing the CAPTURE-JIA data and to provide a focus for harmonizing software development across multiple organizations. The definitions in the Data Dictionary are likely to change slightly over time.

The UK PRh community is committed to and enthusiastic about clinical research with an excellent track record of collaboration and recruitment to clinical trials [22, 26]. These studies are essential given the number of off-licence therapies available to treat CYP with JIA and the wide variation in response [27]. Embedding research-quality data collection in routine clinical care will facilitate ease of participation in observational studies and clinical trials and maximize opportunities for collaborative studies, which are essential for this rare and heterogeneous disease, thus increasing opportunities to further our understanding of susceptibility and outcome.

Routine collection of the CAPTURE-JIA dataset will generate key information about the clinical effects and cost-effectiveness of treatments, informing NHS and other national health care commissioning bodies. The dataset may be an exemplar for new approaches to care for other chronic conditions with onset in childhood.

In conclusion, we present CAPTURE-JIA, the first ‘core dataset’ including those data items considered essential by key stakeholder groups engaged with leading and improving the clinical care of CYP with JIA. The dataset is the first step towards improving the quality and consistency of clinical services across the UK and beyond. An ongoing commitment from all stakeholders remains key to the future success of this ambitious project.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of the people who contributed to this work and in particular the CAPTURE-JIA Steering Group and CAPTURE-JIA Expert Group for their help throughout the project. Project steering group membership included G.A., Eileen Baildam, J.C., S.D., H.F., F.M. and W.T. Expert Group membership included Eslam Al-Abadi, Kate Armon, K.B., Michael Beresford, Jeremy Camilleri, G.C., Terry Cox, Joyce Davidson, Penny Davis, Andrew Fell, Mark Friswell, Elaine Haggart, Sarah Hartfree, Daniel Hawley, Kimme Hyrich, John Ioannou, Zeba Jamal, Akhila Kavirayani, Shane Kirrane, Alice Leahy, Catherine Lees, Liza McCann, Janet McDonagh, Bridget Oates, Clare Pain, Ira Pande, Clarissa Pilkington, Ellie Potts, Athimalaipet Ramanan, A.R., Philip Riley, Madeleine Rooney, S.S., Rangaraj Satyapal, S.S.-W., Allan Smith, Simon Stones, Helen Strike, Rachel Tatttersall, Lucy Wedderburn, Nick Wilkinson, Mark Wood and Ruth Wyllie. Special thanks to Suzanne Parsons who helped to design and facilitate the CAPTURE JIA workshop.

Thanks also go to the British Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology (BSPAR), the CHART Consortium and the HQIP JIA Audit Steering Group for their support throughout the project.

W.T. is supported by Arthritis Research UK grant number 20380 and the National Institute for Health Research Manchester Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Centre.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, The National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from Arthritis Research UK 20877.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Petty RE, Southwood TR, Baum J. et al. Revision of the proposed classification criteria for juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Durban, 1997. J Rheumatol 1998;25:1991–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P. et al. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol 2004;31:390–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Symmons DP, Jones M, Osborne J. et al. Pediatric rheumatology in the United Kingdom: data from the British Pediatric Rheumatology Group National Diagnostic Register. J Rheumatol 1996;23:1975–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moorthy LN, Peterson MG, Hassett AL, Lehman TJ.. Burden of childhood-onset arthritis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2010;8:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shoop-Worrall SJ, Kearsley-Fleet L, Thomson W, Verstappen SM, Hyrich KL.. How common is remission in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017;47:331–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Glerup M, Herlin T, Twilt M.. Clinical outcome and long-term remission in JIA. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2017;19:75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van Dijkhuizen EH, Wulffraat NM.. Early predictors of prognosis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a systematic literature review. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1996–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Foster H, Rapley T.. Access to pediatric rheumatology care—a major challenge to improving outcome in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2010;37:2199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shoop-Worrall SJW, Verstappen SMM, McDonagh JE. et al. Long-term outcomes following achievement of clinically inactive disease in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: the importance of definition. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018;70:1519–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Institute of Medicine. America's health in transition: protecting and improving quality. Washington, DC, USA: The National Academies Press, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abstracts from the 2014 annual conference of the British Society of Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology. Rheumatology 2015;54:ii5–16. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Giannini EH, Ruperto N, Ravelli A. et al. Preliminary definition of improvement in juvenile arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1202–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wallace CA, Giannini EH, Huang B, Itert L, Ruperto N.. American College of Rheumatology provisional criteria for defining clinical inactive disease in select categories of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2011;63:929–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wallace CA, Ruperto N, Giannini E. et al. Preliminary criteria for clinical remission for select categories of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2004;31:2290–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Magni-Manzoni S, Ruperto N, Pistorio A. et al. Development and validation of a preliminary definition of minimal disease activity in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:1120–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Consolaro A, Ruperto N, Bazso A. et al. Development and validation of a composite disease activity score for juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:658–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McErlane F, Beresford MW, Baildam EM. et al. Validity of a three-variable Juvenile Arthritis Disease Activity Score in children with new-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1983–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McErlane F, Beresford MW, Baildam EM, Thomson W, Hyrich KL.. Recent developments in disease activity indices and outcome measures for juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology 2013;52:1941–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Davies K, Cleary G, Foster H, Hutchinson E, Baildam E.. BSPAR standards of care for children and young people with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology 2010;49:1406–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kavirayani A, Foster HE.. Paediatric rheumatology practice in the UK benchmarked against the British Society for Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology/Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Alliance Standards of Care for juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology 2013;52:2203–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C.. Using and reporting the delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS One 20116:e20476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McErlane F, Foster HE, Armitt G. et al. Development of a national audit tool for juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a BSPAR project funded by the Health Care Quality Improvement Partnership. Rheumatology 2018;57:140–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McCann LJ, Kirkham JJ, Wedderburn LR. et al. Development of an internationally agreed minimal dataset for juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM) for clinical and research use. Trials 2015;16:268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Delbecq AV, Gustafson DH.. Group techniques for program planning, a guide to nominal group and Delphi processes. Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman Company, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Martini A, Ravelli A, Avcin T. et al. Toward new classification criteria for juvenile idiopathic arthritis: first steps, pediatric rheumatology international trials organization international consensus. J Rheumatol 2019;46:190–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ramanan AV, Dick AD, Jones AP. et al. Adalimumab plus methotrexate for uveitis in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1637–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Davies R, Carrasco R, Foster HE. et al. Treatment prescribing patterns in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA): analysis from the UK Childhood Arthritis Prospective Study (CAPS). Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016;46:190–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.