Abstract

Background:

Legal interventions are important mechanisms for chronic disease prevention. Since Canadian laws to promote physical activity and healthy eating are growing, we compared the characteristics of legal interventions targeting physical activity and healthy eating with tobacco control laws, which have been extensively described.

Methods:

We reviewed 718 federal, provincial and territorial laws promoting tobacco control, physical activity and healthy eating captured in the Prevention Policies Directory between spring 2010 and September 2017. We characterized the legislation with regard to its purpose, tools to accomplish the purpose, responsible authorities, target location, level of coerciveness and provisions for enforcement.

Results:

Two-thirds (67.9%) of tobacco control legislation had a primary chronic disease prevention purpose (explicit in 5.3% of documents and implicit in 62.6%), and 29.5% had a secondary chronic disease prevention purpose. One-quarter (27.0%) of physical activity legislation had a primary chronic disease prevention purpose (explicit in 8.8% of documents and implicit in 18.1%), and 53.0% had a secondary chronic disease prevention purpose. In contrast, 69.3% of healthy eating legislation had no chronic disease prevention purpose. Tobacco control legislation was most coercive (restrict or eliminate choice), and physical activity and healthy eating legislation was least coercive (provide information or enable choice). Most tobacco control legislation (85.8%) included provisions for enforcement, whereas 47.4% and 24.8% of physical activity and healthy eating laws, respectively, included such provisions. Patterns in responsible authorities, target populations, settings and tools to accomplish its purpose (e.g., taxation, subsidies, advertising limits, prohibitions) also differed between legislation targeting tobacco control versus physical activity and healthy eating.

Interpretation:

Legislative approaches to promote physical activity and healthy eating lag behind those for tobacco control. The results serve as a baseline for building consensus on the use of legislation to support approaches to chronic disease prevention to reduce the burden of chronic disease in Canadians.

Legislative and regulatory approaches are important mechanisms for chronic disease prevention whereby governments use law to create health-supporting environments that enable behaviour change.1–3 Growing evidence supports the use of legal interventions (e.g., taxation; appropriate packaging, labelling and composition standards; marketing restrictions) as key components within a comprehensive chronic disease prevention strategy.4–7 At the United Nations high-level meeting on the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases in September 2018, Canada and other governments reaffirmed commitment to urgent implementation of priority interventions — the “best buys” — targeting lifestyle behaviours6–8 to accelerate action on reducing the escalating burden of chronic disease.9 Best buys are evidence-based and cost-effective, and have major public health impact. They consist of predominantly legal and regulatory interventions, such as bans on industrial trans fats and taxation on sugar-sweetened beverages.6–8

Enactment of legislation has been central to tobacco control in Canada, leading to considerable progress in curbing tobacco use.10 The use of law is enshrined in the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, a legally binding treaty.11 Building on lessons from tobacco control can help accelerate progress in developing public regulations to promote physical activity and healthy eating.12,13 In Canada and other jurisdictions, tobacco control policies have been identified, described and evaluated extensively. 14–18 Legal interventions targeting physical activity and healthy eating are increasing,19–23 with recent Canadian studies examining the effects of provincial bans of food and beverage advertising on the quality and quantity of advertised products24– 26 and of provincial bans of junk food in schools on overweight and obesity in children.27 To provide a baseline for measuring progress toward United Nations commitments and to build Canadian consensus on the use of law for chronic disease prevention, we need to compare legal interventions targeting physical activity and healthy eating to tobacco control laws. Guided by Rogers’28 diffusion of innovations framework, we characterized Canadian federal, provincial and territorial legislation promoting tobacco control, physical activity and healthy eating with regard to its purpose, tools to accomplish the purpose, responsible authorities, target location, level of coerciveness and provisions for enforcement.

Methods

Setting

Legal interventions pertaining to chronic disease prevention in Canada constituted the general setting for this study.

Data sources

The Prevention Policies Directory (PPD) is a regularly updated, comprehensive online inventory developed and curated by the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer and modelled on the US National Cancer Institute State Cancer Legislative Database. It is populated by a Web-scanning technology by Lexum Informatique Juridique (lexum.com) that scans monthly current and archived content of more than 200 websites.29 The technology was developed and validated to ensure that it captures publicly available legislation from all federal, provincial and territorial government websites. It also extracts legislation from the Canadian Legal Information Institute (CanLII), which provides centralized access to a comprehensive virtual library of consolidated Canadian laws from all jurisdictions that are uploaded monthly (http://canlii.org/).29 Captured documents are scored against multiple Boolean queries for relevance and reviewed by a curator for quality assurance. A detailed description of the PPD design and methodology has been published elsewhere.29

Design

For each document entered into the PPD between spring 2010 and September 2017, the PPD contains descriptive information (document type, title, geographic location, targeted risk factor, year) and includes a link to the document on a government website or CanLII. We used PPD descriptive data to identify federal, provincial and territorial legislation targeting tobacco control, physical activity, the built environment and healthy eating that came into effect between 1980 and September 2017. We included as legislation statutes, regulations, codes and bills that received royal assent. We combined legislation targeting the built environment (e.g., roads, buildings, infrastructure and parks, human-made landscape and preservation of the natural environment for recreation) and physical activity (e.g., physical education standards, child fitness tax credits) because improving the built environment also improves opportunities for physical activity.30 A “general” category comprised broad legislation concerning chronic disease prevention that made no specific reference to tobacco control, physical activity or healthy eating (e.g., provincial and territorial public health acts).29

Two coders trained in law and public health independently extracted the data from the text of each legislative document using a coding manual that described the coding criteria. For 3 variables (purpose, tools to accomplish the purpose, level of coerciveness), the coding criteria are well established, as described below. The coding criteria for the 3 other variables (ministry responsible, target location, enforcement provisions) were developed de novo. In pilot work, 2 team members (J.M. and K.M.) each coded 100 diverse legislative documents to ensure that our coding system consistently differentiated policies in terms of strength (e.g., legislation that bans smoking in public places should be scored high, whereas legislation concerning healthy eating that lacks provisions to address chronic disease prevention should be scored low). Last, we consulted public health law experts at the University of Alberta’s Health Law Institute, the Public Health Agency of Canada and the World Health Organization to ensure that our measures were comprehensive and had face and content validity. Coding disagreements generally arose from texts with vague terminology or inconsistent use of terms. In the few cases (< 5) of unresolved disagreement, we reported the data extracted by the legal coder.

Outcome measures

We used standard legal analysis methods,31 including validated statutory interpretation methods, to interpret purpose,32 Gostin’s33 criteria to assess tools to accomplish the purpose and the Nuffield Council on Bioethics policy framework to assess level of coerciveness.34 We derived the statutory purpose from the objective or purpose statements of each legislative document, which declare the intention of the legislators. 32,35 We distinguished whether the legislation had a primary or secondary chronic disease prevention purpose based on whether an entire piece of legislation or a portion thereof, respectively, focused on chronic disease prevention.32 For example, Prince Edward Island’s Smoke-free Places Act36 has a primary chronic disease prevention purpose to reduce tobacco use and exposure, whereas Alberta’s Child Care Licensing Act37 has a secondary chronic disease prevention purpose; its primary purpose is licensing and regulation of daycare centres, with provisions stipulating serving of healthy foods or prohibition of smoking on day care premises. We categorized the intent of the legislation as explicit versus implicit based on whether the primary purpose was stated in the preamble or implied, respectively.35 We coded legislation that did not mention chronic disease prevention as having no chronic disease prevention purpose. For example, the purpose of Canada’s National Dairy Code38 is to regulate the production and processing of dairy products, with no reduction targets for trans fat or sodium relevant to chronic disease prevention.

We based our assessment of tools or means through which the legislation accomplished its purpose on Gostin’s33 criteria, which include 1) economic incentives and disincentives that raise revenue and allocate resources for the good of the population (e.g., tax breaks for enrolment of children in physical activity programs), 2) interventions that alter the informational environment (e.g., nutrition labelling) and 3) direct regulation, which involves monitoring of compliance and punishment of noncompliance with health and safety standards (e.g., restriction on sales of tobacco to minors). The classification of tools is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1:

Classification of tools used to accomplish the legislation purpose32

| Tool | Description |

|---|---|

| Tax and spend | Impose taxes, provide tax credits or exemptions |

| Direct regulation | Directly impose restrictions such as prohibitions and licensing on individuals and businesses |

| Indirect regulation through tort system | Grant of causes of action in tort to government or others |

| Deregulation | Repeal of legislative provisions that disincentivize desired public health behaviours |

| Delegation of regulation to public administrative body | Grant legal authority to public or administrative body (e.g., school board) empowering it to act and set its duties |

| Alter informational environment | Mandate product labelling, instructions for safe use, disclosure of ingredients or health warnings, limits on harmful or misleading advertising |

| Alter built environment | Grant ability to alter or regulate built environment or what people can do with built environment |

| Alter socioeconomic environment | Improve health by targeting social or economic resources to benefit of disadvantaged populations |

We determined the responsible ministry from the legislation or from public government websites. The responsibility for the legislation, including amendments and enactment of regulations, may be the same as or distinct from administrative responsibility, which may be delegated to public bodies (captured under the coding of tools). We assigned a name to each ministry according to the most common name in use across Canadian jurisdictions (e.g., ministry of health). We assessed the target location for the application of the legislation from the text or inferred it from the content and purpose of the legislation.39

We assigned a level of coerciveness based on the Nuffield Council on Bioethics policy framework,34 which differentiates 8 levels of intervention, from least to most restrictive of individual rights: 1) do nothing (simply monitor the situation), 2) provide information (inform and educate people [e.g., health warnings, nutrition labels]), 3) enable choice (support behaviour change), 4) guide choices by changing default options (make “healthier” choices the default), 5) guide choice through incentives (financial and other incentives to guide people to pursue healthy activities), 6) guide choice through disincentives (financial and other disincentives to guide people not to pursue unhealthy activities), 7) restrict choice (regulate to restrict options available) and 8) eliminate choice (regulate to eliminate choice entirely).34,40

We assessed whether the legislation included enforcement provisions (appointment and duties of officers and inspectors, or powers of audit, search, seizure or inspection) and specified conditions for an offence or penalty: in the legislation itself, in the enacting legislation of regulations or under another piece of legislation.41

Data analysis

The data were entered into Microsoft Excel and analyzed with the Stata 13 statistical package (Stata Corp.).

Ethics approval

The University of Alberta Research Ethics Board approved the study protocol.

Results

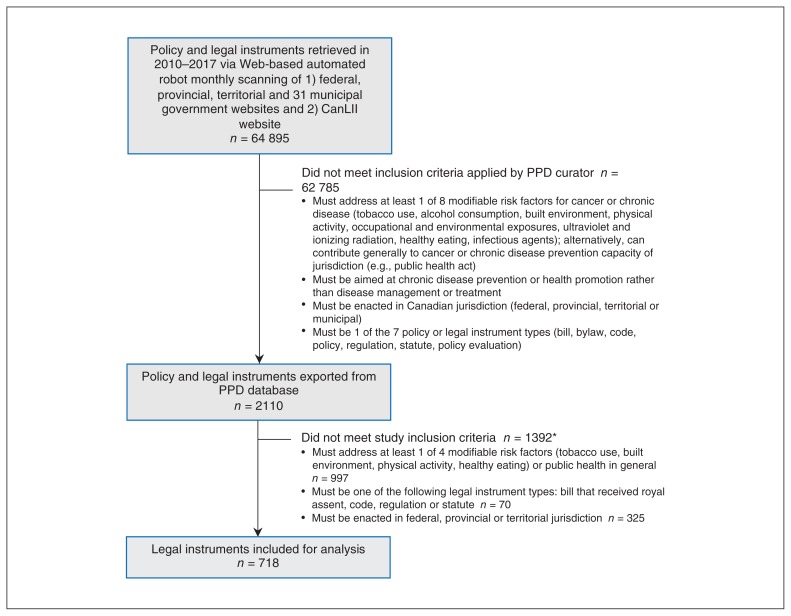

We identified 718 pieces of legislation that met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Interrater reliability was high (agreement > 90%; κ > 0.90). Table 2 shows the distribution of legislation according to type and targeted risk factor (provincial distribution is found in Appendix 1, Supplemental Table S1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/4/E745/suppl/DC1). Two-thirds (67.9%) of tobacco control legislation had a primary chronic disease prevention purpose, 29.5% had a secondary prevention purpose, and 2.1% had no prevention purpose42 (Table 3). Just over half (53.0%) of legislation targeting physical activity had a secondary chronic disease prevention purpose, 27.0% had a primary prevention purpose, and 20.0% had no prevention purpose. Two-thirds (69.3%) of legislation targeting healthy eating had no chronic disease prevention purpose, 23.8% had a secondary prevention purpose, and 6.9% had a primary prevention purpose. A condensed list of the primary purpose of the legislation is found in Appendix 1, Supplemental Table S2.

Figure 1:

Flow chart showing selection of Prevention Policy Directory (PPD) legislation for analysis. *Criteria applied by study investigators. Note: CanLII = Canadian Legal Information Institute.

Table 2:

Legislation type by targeted risk factor

| Legislation type | Risk factor; no. (%) of documents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco control n = 190 |

Physical activity n = 215 |

Healthy eating n = 101 |

Multiple factors* n = 100 |

Total† n = 718 |

|

| Statute | 75 (39.5) | 116 (54.0) | 42 (41.6) | 19 (19.0) | 335 (46.7) |

| Regulation | 84 (44.2) | 80 (37.2) | 47 (46.5) | 74 (74.0) | 303 (42.2) |

| Code | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.0) | 3 (0.4) |

| Bill | 31 (16.3) | 18 (8.4) | 12 (11.9) | 5 (5.0) | 77 (10.7) |

Legislation targeting more than 1 risk factor.

Includes general legislation (e.g., provincial public health act).

Table 3:

Legislation purpose and tools to accomplish its purpose by targeted risk factor

| Variable | Risk factor; no. (%) of documents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco control n = 190 |

Physical activity n = 215 |

Healthy eating n = 101 |

Multiple factors* n = 100 |

Total† n = 718 |

|

| Purpose | |||||

| Primary — explicit | 10 (5.3) | 19 (8.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (5.0) | 35 (4.9) |

| Primary — implicit | 119 (62.6) | 39 (18.1) | 7 (6.9) | 7 (7.0) | 175 (24.4) |

| Secondary | 56 (29.5) | 114 (53.0) | 24 (23.8) | 75 (75.0) | 307 (42.8) |

| No purpose | 4 (2.1) | 43 (20.0) | 70 (69.3) | 12 (12.0) | 199 (27.7) |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.3) |

| Tools to accomplish purpose | |||||

| Tax and spend | 33 (17.4) | 44 (20.5) | 6 (5.9) | 13 (13.0) | 100 (13.9) |

| Direct regulation | 148 (77.9) | 30 (14.0) | 18 (17.8) | 67 (67.0) | 269 (37.5) |

| Indirect regulation | 17 (8.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (2.4) |

| Regulation through public body | 15 (7.9) | 64 (29.8) | 8 (7.9) | 8 (8.0) | 128 (17.8) |

| Alter informational environment | 32 (16.8) | 2 (0.9) | 4 (4.0) | 2 (2.0) | 42 (5.8) |

| Alter built environment | 3 (1.6) | 124 (57.7) | 0 (0.0) | 39 (39.0) | 185 (25.8) |

| Alter socioeconomic environment | 1 (0.5) | 4 (1.9) | 3 (3.0) | 2 (2.0) | 10 (1.4) |

Legislation targeting more than 1 risk factor.

Includes general legislation (e.g., provincial public health act).

Most (77.9%) tobacco control legislation used direct regulation to accomplish its purpose, followed by tax and spend (17.4%) and alter informational environment (16.8%) (Table 3). Alter built environment was the most common tool used in physical activity legislation, at 57.7%, followed by regulation through a public body (29.8%) and tax and spend (20.5%). The legislation targeting healthy eating used direct regulation (17.8%), regulation through a public body (7.9%) and tax and spend (5.9%).

For most legislation (44.7%), the ministry of health held legislative responsibility for tobacco control legislation, followed by finance (28.4%) and justice (12.6%) (Table 4). For physical activity legislation, the ministry of the environment most commonly held legislative responsibility (24.6%), followed by municipalities (19.5%) and culture (8.8%). The ministries of health (9.9%), social services (6.9%) and education (5.9%) were most often responsible for legislation targeting healthy eating.

Table 4:

Ministry responsible for legislation and target location by targeted risk factor

| Variable | Risk factor; no. (%) of documents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco control n = 190 |

Physical activity n = 215 |

Healthy eating n = 101 |

Multiple factors* n = 100 |

Total† n = 718 |

|

| Ministry responsible | |||||

| Health | 85 (44.7) | 1 (0.5) | 10 (9.9) | 27 (27.0) | 131 (18.2) |

| Finance | 54 (28.4) | 13 (6.0) | 4 (4.0) | 7 (7.0) | 78 (10.9) |

| Municipal | 0 (0.0) | 42 (19.5) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (5.0) | 63 (8.8) |

| Environment | 0 (0.0) | 53 (24.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.0) | 56 (7.8) |

| Education | 2 (1.0) | 14 (6.5) | 6 (5.9) | 5 (5.0) | 32 (4.5) |

| Social services | 0 (0.0) | 5 (2.3) | 7 (6.9) | 16 (16.0) | 32 (4.5) |

| Justice | 24 (12.6) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 28 (3.9) |

| Culture | 0 (0.0) | 19 (8.8) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (7.0) | 26 (3.6) |

| Transportation | 10 (5.3) | 8 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 20 (2.8) |

| Agriculture | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (3.0) | 14 (14.0) | 20 (2.8) |

| Development | 1 (0.5) | 12 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 14 (1.9) |

| Employment/labour | 9 (4.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.0) | 11 (1.5) |

| Other | 3 (1.6) | 46 (21.4) | 70 (69.3) | 11 (11.0) | 207 (28.8) |

| Target location | |||||

| Municipalities | 8 (4.2) | 60 (27.9) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (9.0) | 94 (13.1) |

| Public transit | 39 (20.5) | 13 (6.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.0) | 58 (8.1) |

| Schools | 31 (16.3) | 12 (5.6) | 7 (6.9) | 2 (2.0) | 56 (7.8) |

| Food establishments | 25 (13.2) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (5.0) | 24 (24.0) | 54 (7.5) |

| Outdoor nonurban spaces | 1 (0.5) | 48 (22.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.0) | 53 (7.4) |

| Long-term care facilities | 23 (12.1) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (5.0) | 15 (15.0) | 45 (6.3) |

| Child care facilities | 15 (7.9) | 1 (0.5) | 6 (5.9) | 19 (19.0) | 44 (6.1) |

| Workplaces | 41 (21.6) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.0) | 44 (6.1) |

| Recreation and sport facilities | 23 (12.1) | 9 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.0) | 36 (5.0) |

| Enclosed public spaces | 35 (18.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 36 (5.0) |

| Hospitals | 28 (14.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 29 (4.0) |

| Universities | 18 (9.5) | 5 (2.3) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 25 (3.5) |

| Pharmacies | 14 (7.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (2.2) |

Legislation targeting more than 1 risk factor.

Includes general legislation (e.g., provincial public health act).

In terms of settings where the legislation applied, workplaces (21.6%), public transit (20.5%) and enclosed public spaces (18.4%) were most often protected by tobacco control legislation (Table 4). Municipalities were most often covered by physical activity legislation (27.9%), followed by outdoor nonurban spaces (22.3%). Finally, healthy eating legislation targeted schools (6.9%), child care facilities (5.9%), food establishments (5.0%) and long-term care facilities (5.0%).

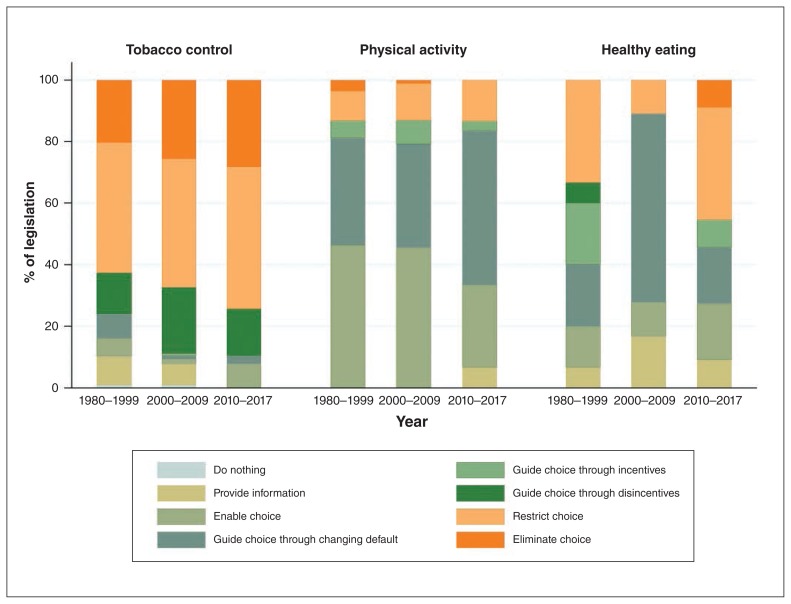

Tobacco control legislation was most restrictive of individual rights across all periods (Figure 2). It most commonly eliminated or restricted choice, and its coerciveness increased gradually between 1980 and 2017, with one-third and two-thirds of legislation eliminating choice or restricting choice, respectively. Most physical activity legislation enabled choice or guided choice through changing the default policy. Legislation targeting healthy eating was least coercive.

Figure 2:

Levels of legislation coerciveness by targeted risk factor and period (based on the Nuffield Council on Bioethics policy framework34).

Finally, most tobacco control legislation included provisions for enforcement (85.8%) and specified conditions for an offence or penalty (86.8%), using 1 of 3 mechanisms: in the legislation itself, via delegated authority or in other legislation (Table 5). About one-half (47.4%) of physical activity legislation and one-quarter (24.8%) of healthy eating legislation included such provisions (Table 5). Most tobacco control laws (86.8%) specified an offence or a penalty, or both, in the legislation itself or in the enabling legislation of regulations; half (49.3%) of physical activity legislation and one-quarter (25.7%) of healthy eating legislation did so.

Table 5:

Legislation enforcement by targeted risk factor

| Variable | Risk factor; no. (%) of documents | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco control n = 190 |

Physical activity n = 215 |

Healthy eating n = 101 |

Multiple factors* n = 100 |

Total† n = 718 |

|

| Provision for enforcement specified | |||||

| In legislation itself | 66 (34.7) | 67 (31.2) | 12 (11.9) | 21 (21.0) | 189 (26.3) |

| In enacting or other legislation | 97 (51.0) | 35 (16.3) | 13 (12.9) | 46 (46.0) | 195 (27.2) |

| None specified | 27 (14.2) | 113 (52.6) | 76 (75.2) | 33 (33.0) | 334 (46.5) |

| Offence or penalty specified | |||||

| In legislation itself | 73 (38.4) | 71 (33.0) | 14 (13.9) | 7 (7.0) | 185 (25.8) |

| In enacting or other legislation | 92 (48.4) | 35 (16.3) | 12 (11.9) | 60 (60.0) | 203 (28.3) |

| None specified | 25 (13.2) | 109 (50.7) | 75 (74.3) | 33 (33.0) | 330 (46.0) |

Legislation targeting more than 1 risk factor.

Includes general legislation (e.g., provincial public health act).

Interpretation

Three key findings emerged from this study. First, the laws investigated are diverse in purpose, tools to accomplish their purpose, responsible authority, target location, coerciveness and enforcement. Second, although the primary goal of most tobacco control legislation in Canada over the study period was to improve behaviour (i.e., reduce tobacco use or exposure) and prevent chronic disease, few laws targeting physical activity or healthy eating had similar primary goals. Third, the restrictiveness of tobacco control legislation increased gradually since 1980. Although the coerciveness of physical activity and healthy eating legislation appears to have increased between 2010 and 2017, these areas lag behind tobacco control, focusing instead on promotion of best practices and adoption of self-regulatory standards by industry.

The central role of public regulatory approaches within national and international chronic disease prevention strategies recognizes governments as key stakeholders in the development of policy frameworks to create health-supporting environments.6–8 The World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control has been a catalyst and powerful legal instrument to promote implementation of strong regulatory approaches aimed at reducing the prevalence of tobacco use and exposure to tobacco smoke. Recent assessments of global tobacco control policies showed substantial increases in highest-level implementation of all key demand-reduction measures of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and provide convincing evidence that these approaches led to considerable reductions in tobacco use and other tobacco-related outcomes.17,18 Implementation of a comprehensive package that combines interventions and policies, particularly higher taxes and smoke-free environment legislation, is critical for accelerating action.12,13

Corroborating international evidence, softer approaches for improving diet and physical activity levels are preferred in Canadian legislation. A systematic assessment of US state-level legislation aimed at preventing childhood obesity adopted in 2003–2005 showed that bills involving softer tools (school nutrition standards, walking/biking trails, safe routes to school) were more likely to be enacted than bills with stronger tools (snack and soda taxes, menu and product labelling). 22 Informed by Gostin’s33 criteria, a systematic review of legislation targeting dietary risk factors enacted in the United States and the European Union since 2004 also highlighted the limited legislative scope, with provision of information to consumers preferred over taxation and marketing restrictions. 23 Research in support of stronger legislative and regulatory approaches for improving diet and activity levels is burgeoning and has served to inform an expanded set of best-buy interventions.6 Studies in the US suggest that a ban on television advertising of unhealthy foods high in sugar, fat or salt is associated with a 20.5% decline in overweight/obesity in children. 43,44 In Canada, the body mass index of schoolchildren declined by 0.05 each year after junk food sales were banned on school property in 6 provinces (i.e., a decline of 1 kg after 5 yr).27 Despite improvements in the nutritional profile of food and beverages advertised to children on television in Quebec,24 which bans advertising to children less than age 13 years,45 the ban does little to limit the amount of food and beverages advertising during prime television viewing time, which highlights the need for monitoring and enforcement. 25,26 Our results show that few laws focused on healthy eating and physical activity in Canada include provisions for monitoring and enforcement.

Limitations

Prevention Policies Directory coverage is comprehensive since all laws in Canada must be publicly accessible. However, some laws may not have been captured owing to the scanning method of monitoring and surveillance of prescribed websites. 29 This limitation is mitigated by the addition of new websites. The CanLII virtual library may also have limitations of completeness (e.g., delays in document transfer and processing) and professional use (i.e., authoritative value, admissibility with relevant authority) listed on its website (www.canlii.org/en/databases.html), which are mitigated in part by the PPD Web-scanning technology, which scans websites in addition to CanLII (e.g., Quebec Department of Justice). The PPD undergoes regular process and outcome evaluation, which shows that it captures a large cross-section of Canadian healthy public policy.29 We excluded municipal bylaws, government policy documents and policy evaluations because our intent was to identify issues and responses important enough to be enshrined in federal, provincial or territorial laws. However, the addition of 325 bylaws from across Canada to our analysis did not change the findings (data not shown). Capturing administrative responsibility was challenging since this information was extracted from the legislation text and publicly accessible government websites. Nonetheless, the analysis showed that responsibility lies across several ministries. Last, we studied characteristics of legislation as it exists “on the books” and not in practice.

Conclusion

This study highlights substantial lags in using stronger legislative approaches to promote physical activity and healthy eating. Our findings underscore the need for improving capacity in the public health system to develop and implement diverse, comprehensive chronic disease prevention laws that are evidence based, well designed and appropriately targeted. Despite United Nations commitments to accelerate action on reducing the escalating burden of chronic disease, Canadian efforts to enact new laws or inject information relevant to chronic disease prevention into existing laws face challenges that thwart the creation of optimally health-supportive environments.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Katerina Maximova conceived and designed the study, and analyzed the data. Kim Raine assisted in study design. Christine Czoli reviewed the literature. Kendall Tisdale assisted with data extraction and management. Tania Bubela conceived the methodology and guided the legislation review. Katerina Maximova interpreted the data, with assistance from Jennifer O’Loughlin. Katerina Maximova and Christine Czoli drafted the manuscript. Kim Raine, Jennifer O’Loughlin, John Minkley, Kendall Tisdale and Tania Bubela revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All of the authors approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This work was funded by operating funds through a Career Development Award in Prevention Research from the Canadian Cancer Society to Katerina Maximova (grant 702936).

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/7/4/E745/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Magnusson R, Patterson D. Role of law in global response to non-communicable diseases. Lancet. 2011;378:859–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60975-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Advancing the right to health: the vital role of law. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [accessed 2019 June 28]. Available: www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/health-law/health_law-report/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gostin LO. Law as a tool to facilitate healthier lifestyles and prevent obesity. JAMA. 2007;297:87–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cecchini M, Sassi F, Lauer J, et al. Tackling of unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, and obesity: health effects and cost-effectiveness. Lancet. 2010;376:1775–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61514-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gostin LO. Legal and public policy interventions to advance the population’s health. In: Smedley BD, Syme SL, editors. Promoting health: intervention strategies from social and behavioral research. Washington: National Academies Press; 2000. pp. 390–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.“Best buys” and other recommended interventions for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases: updated 2017 Appendix 3 of the Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [accessed 2019 June 28]. Available: www.who.int/ncds/management/WHO_Appendix_BestBuys.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Time to deliver: report of the WHO Independent high-level commission on noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [accessed 2019 June 28]. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/272710. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agenda item 119, 73rd sess. New York: United Nations; 2018. [accessed 2019 June 28]. 73/2. Political declaration of the third high-level meeting of the General Assembly on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. Available: www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/73/2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.How healthy are Canadians? A trend analysis of the health of Canadians from a healthy living and chronic disease perspective. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2016. [accessed 2019 June 28]. Available: www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/how-healthy-canadians.html. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strong foundation, renewed focus: an overview of Canada’s federal tobacco control strategy 2012–2017. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2012. [accessed 2019 June 28]. Available: www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/healthy-living/strong-foundation-renewed-focus-overview-canada-federal-tobacco-control-strategy-2012-17.html. [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [accessed 2019 June 28]. Available: www.who.int/fctc/text_download/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yach D, McKee M, Lopez AD, et al. Improving diet and physical activity: 12 lessons from controlling tobacco smoking. BMJ. 2005;330:898–900. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7496.898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blouin C, Dubé L. Global health diplomacy for obesity prevention: lessons from tobacco control. J Public Health Policy. 2010;31:244–55. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2010.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asbridge M. Public place restrictions on smoking in Canada: assessing the role of the state, media, science and public health advocacy. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nykiforuk CI, Eyles J, Campbell HS. Smoke-free spaces over time: a policy diffusion study of bylaw development in Alberta and Ontario, Canada. Health Soc Care Community. 2008;16:64–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2007.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eriksen MP, Cerak RL. The diffusion and impact of clean indoor air laws. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:171–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gravely S, Giovino GA, Craig LV, et al. Implementation of key demand-reduction measures of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and change in smoking prevalence in 126 countries: an association study. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2:e166–74. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30045-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung-Hall J, Craig L, Gravely S, et al. Impact of the WHO FCTC over the first decade: a global evidence review prepared for the Impact Assessment Expert Group. Tob Control. 2019;28(Suppl 2):s119–28. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eyler AA, Budd E, Camberos GJ, et al. State legislation related to increasing physical activity: 2006–2012. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13:207–13. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2015-0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cawley J, Liu F. Correlates of state legislative action to prevent childhood obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:162–7. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monnat SM, Lounsbery MAF, Smith NJ. Correlates of state enactment of elementary school physical education laws. Prev Med. 2014;69(Suppl 1):S5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boehmer TK, Luke DA, Haire-Joshu DL, et al. Preventing childhood obesity through state policy. Predictors of bill enactment. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34:333–40. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sisnowski J, Handsley E, Street JM. Regulatory approaches to obesity prevention: a systematic overview of current laws addressing diet-related risk factors in the European Union and the United States. Health Policy. 2015;119:720–31. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Potvin Kent M, Dubois L, Wanless A. A nutritional comparison of foods and beverages marketed to children in two advertising policy environments. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:1829–37. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Potvin Kent M, Dubois L, Wanless A. Self-regulation by industry of food marketing is having little impact during children’s preferred television. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6:401–8. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2011.606321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kent MP, Dubois L, Wanless A. Food marketing on children’s television in two different policy environments. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6:e433–41. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2010.526222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leonard PS. Do school junk food bans improve student health? Evidence from Canada. Can Public Policy. 2017;43:105–19. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed. New York: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Politis CE, Halligan MH, Keen D, et al. Supporting the diffusion of healthy public policy in Canada: the Prevention Policies Directory. Online J Public Health Inform. 2014;6:e177. doi: 10.5210/ojphi.v6i2.5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sallis JF, Bauman A, Pratt M. Environmental and policy interventions to promote physical activity. Am J Prev Med. 1998;15:379–97. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCormack N, Papadopoulos J, Cotter C. The practical guide to Canadian legal research. 4th ed. Toronto: Carswell, Thomson Reuters; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sullivan R. Sullivan on the construction of statutes. 6th edition. Toronto: Lexis-Nexis Canada; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gostin LO. Public health law: power, duty, restraint. 2nd ed. Berkeley (CA): University of California Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Public health: ethical issues. London (UK): Nuffield Council on Bioethics; 2007. [accessed 2019 June 28]. Available: https://nuffieldbioethics.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Public-health-ethical-issues.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sullivan R. Statutory interpretation in a new nutshell. Can Bar Rev. 2003;82:51–82. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smoke-free Places Act, RSPEI 1988, c S-4.2. [accessed 2019 Feb 19]. Available: http://canlii.ca/t/538zc.

- 37.Child Care Licensing Act, SA 2007, c C-10.5. [accessed 2019 Feb 19]. Available: http://canlii.ca/t/52vn4.

- 38.National Dairy Code: production and processing requirements. 7th ed. Ottawa: Canadian Dairy Information Centre; 2015. [accessed 2019 June 28]. Available: www.dairyinfo.gc.ca/pdf/dairy_code_sept_2015_I_e.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 39.The Education Act, 1995, SS 1995, c E-0.2. [accessed 2019 Feb 19]. Available: http://canlii.ca/t/533q2.

- 40.PLACE Research Lab intervention ladder policy analysis framework. Edmonton: Policy, Location and Access in Community Environments (PLACE) Research Lab, School of Public Health, University of Alberta; 2107. [accessed 2019 June 28]. Available: http://placeresearchlab.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/final_interventionladder_kab_2017-11-14.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Offence Act, RSBC 1996, c 338. [accessed 2019 Feb 19]. Available: http://canlii.ca/t/533tx.

- 42.Regulation respecting the Québec sales tax, CQLR c T-0.1, r 2. [accessed 2019 June 20]. Available: http://canlii.ca/t/53kx2.

- 43.Chou SY, Rashad I, Grossman M. Fast-food restaurant advertising on television and its influence on childhood obesity. J Law Econ. 2008;51:599–618. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Veerman JL, Van Beeck EF, Barendregt JJ, et al. By how much would limiting TV food advertising reduce childhood obesity? Eur J Public Health. 2009;19:365–9. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Consumer Protection Act, CQLR c P-40.1. [accessed 2019 Feb 22]. Available: http://canlii.ca/t/53h79.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.