TO THE EDITORS:

Berggren et al1 provide valuable data that describe the increase in resting metabolic rate (RMR) during pregnancy and its relationship with changes in body composition. The authors showed RMR increased 19 ± 6% from early to late pregnancy.

Expressing RMR per kilogram of fat-free mass (FFM), the most important determinant of RMR, the authors account for pregnancy-related changes in FFM and showed that RMR was 7 ± 11% higher in late pregnancy and therefore concluded that there was an adaptive thermogenesis (wasting of energy). A negative correlation between the change in RMR/FFM and the change in maternal fat mass then led to the conclusion that low adaptive thermogenesis (or the inability to waste energy) may contribute to fat accumulation for some women.

The energy metabolism field has spent extensive time considering different approaches for estimating adaptive thermogenesis.2 The field asserts that using a simple ratio (RMR/FFM) is insufficient because the y-intercept of this relation is not equal to zero.2 Furthermore, only considering FFM when estimating adaptive thermogenesis is not sufficient because fat mass (FM) contributes 7–12 kcal/kg to RMR per day.3,4 Age and race are also significant determinants of RMR in especially large heterogeneous cohorts.

The accepted practice is to use linear regression to model independent variables of interest on the initial measured energy expenditure (ie, early pregnancy). This approach provides an equation (ie, RMR = a⋆[fat-free mass] + b⋆[fat mass] + c⋆[age] + intercept) that, when individual data for each independent variable is imputed, yields an RMR for each person that is now proportional to these variables (RMRadjusted). RMRadjusted can then be used in statistical analyses to understand differences between individuals or changes throughout pregnancy that are dependent on body composition and to quantify adaptive thermogenesis that is independent of body composition (ie, RMR minus RMRadjusted).

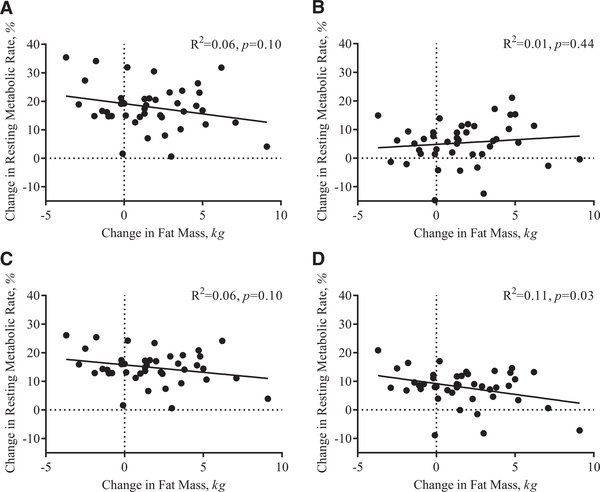

Using our published data (Figure),3 we also observe increases in RMR from early to late pregnancy that are similar to data from Berggren et al1 (A, 18 ± 8% as absolute values, and B, 5 ± 7% as RMR/FFM). When using linear regression considering FFM only, the adaptive thermogenesis in RMR is 15 ± 6% (C). Yet when FM and age are also included, the adaptive thermogenesis is 8 ± 6% (D).

FIGURE. Effect of using different methodologies to adjust resting metabolic rate.

Changes in fat mass and RMR are shown from mid- to late pregnancy (weeks 22–36). Changes in RMR from mid- to late pregnancy are expressed as percentage change absolute values (A), as percentage change in the ratio, RMR/FFM (B), as percentage adaptive thermogenesis, using FFM as the only independent determinant of RMR (C), and as percentage adaptive thermogenesis, using FFM, FM, and age as independent determinants of RMR (D).

Hence, there are important methodological considerations needed for appropriate analysis and interpretation of RMR data (Figure). Importantly, the accepted analytical approach supports the conclusion of Berggren et al.1 We encourage the authors to use these more rigorous statistical approaches to test the robustness of their findings, which will allow for comparison with other published studies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds from the National Institutes of Health (grant R01DK099175; to Dr Redman).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berggren EK, O’Tierney-Ginn P, Lewis S, Presley L, De-Mouzon SH, Catalano PM. Variations in resting energy expenditure: impact on gestational weight gain. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:445.e1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muller MJ, Geisler C, Hubers M, Pourhassan M, Braun W, Bosy-Westphal A. Normalizing resting energy expenditure across the life course in humans: challenges and hopes. Eur J Clin Nutr 2018;72: 628–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilmore LA, Butte NF, Ravussin E, Han H, Burton JH, Redman LM. Energy intake and energy expenditure for determining excess weight gain in pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol 2016;127:884–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Most J, Vallo PM, Gilmore LA, et al. Energy expenditure in pregnant women with obesity does not support energy intake recommendations. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2018;26:992–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]