Abstract

The aim of this article is to introduce family medicine researchers to case study research, a rigorous research methodology commonly used in the social and health sciences and only distantly related to clinical case reports. The article begins with an overview of case study in the social and health sciences, including its definition, potential applications, historical background and core features. This is followed by a 10-step description of the process of conducting a case study project illustrated using a case study conducted about a teaching programme executed to teach international family medicine resident learners sensitive examination skills. Steps for conducting a case study include (1) conducting a literature review; (2) formulating the research questions; (3) ensuring that a case study is appropriate; (4) determining the type of case study design; (5) defining boundaries of the case(s) and selecting the case(s); (6) preparing for data collection; (7) collecting and organising the data; (8) analysing the data; (9) writing the case study report; and (10) appraising the quality. Case study research is a highly flexible and powerful research tool available to family medicine researchers for a variety of applications.

Keywords: Case study research, research design, mixed methods, family practice, primary care, general practice

Significance statement

Given their potential for answering ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions about complex issues in their natural setting, case study designs are being increasingly used in the health sciences. Conducting a case study can, however, be a complex task because of the possibility of combining multiple methods and the need to choose between different types of case study designs. In order to introduce family medicine and community health researchers to the fundamentals of case study research, this article reviews its definition, potential applications, historical background and main characteristics. It follows on with a practical, step-by-step description of the case study process that will be useful to researchers interested in implementing this research design in their own practice.

Introduction

This article provides family medicine and community health researchers a concise resource to conduct case study research. The article opens with an overview of case study in the social and health sciences, including its definition, potential applications, historical background and core features. This is followed by a 10-step description of the process of conducting a case study project, as described in the literature. These steps are illustrated using a case study about a teaching programme executed to teach international medical learners sensitive examination skills. The article ends with recommendations of useful articles and textbooks on case study research.

Origins of case study research

Case study is a research design that involves an intensive and holistic examination of a contemporary phenomenon in a real-life setting.1–3 It uses a variety of methods and multiple data sources to explore, describe or explain a single case bounded in time and place (ie, an event, individual, group, organisation or programme). A distinctive feature of case study is its focus on the particular characteristics of the case being studied and the contextual aspects, relationships and processes influencing it.4 Here we do not include clinical case reports as these are beyond the scope of this article. While distantly related to clinical case reports commonly used to report unusual clinical case presentations or findings, case study is a research approach that is frequently used in the social sciences and health sciences. In contrast to other research designs, such as surveys or experiments, a key strength of case study is that it allows the researcher to adopt a holistic approach—rather than an isolated approach—to the study of social phenomena. As argued by Yin,3 case studies are particularly suitable for answering ‘how’ research questions (ie, how a treatment was received) as well as ‘why’ research questions (ie, why the treatment produced the observed outcomes).

Given its potential for understanding complex processes as they occur in their natural setting, case study increasingly is used in a wide range of health-related disciplines and fields, including medicine,5 nursing,6 health services research1 and health communication.7 With regard to clinical practice and research, a number of authors1 5 8 have highlighted how insights gained from case study designs can be used to describe patients’ experiences regarding care, explore health professionals’ perceptions regarding a policy change, and understand why medical treatments and complex interventions succeed or fail.

In anthropology and sociology, case study as a research design was introduced as a response to the prevailing view of quantitative research as the primary way of undertaking research.9 From its beginnings, social scientists saw case study as a method to obtain comprehensive accounts of social phenomena from participants. In addition, it could complement the findings of survey research. Between the 1920s and 1960s, case study became the predominant research approach among the members of the Department of Sociology of the University of Chicago, widely known as ‘The Chicago School’.10 11 During this period, prominent sociologists, such as Florian Znaniecki, William Thomas, Everett C Hughes and Howard S Becker, undertook a series of innovative case studies (including classical works such as The Polish peasant in Europe and America or Boys in White), which laid the foundations of case study designs as implemented today.

In the 1970s, case study increasingly was adopted in the USA and UK in applied disciplines and fields, such as education, programme evaluation and public policy research.12 As a response to the limitations of quasi-experimental designs for undertaking comprehensive programme evaluations, researchers in these disciplines saw in case studies—either alone or in combination with experimental designs—an opportunity to gain additional insights into the outcomes of programme implementation. In the mid-1980s and early 1990s, the case study approach became recognised as having its own ‘logic of design’ (p46).13 This period coincides with the publication of a considerable number of influential articles14–16 and textbooks4 17 18 on case study research.

These publications were instrumental in shaping contemporary case study practice, yet they reflected divergent views about the nature of case study, including how it should be defined, designed and implemented (see Yazan19 for a comparison of the perspectives of Yin, Merriam and Stake, three leading case study methodologists). What these publications have in common is that case study revolves around four key features.

First, case study examines a specific phenomenon in detail by performing an indepth and intensive analysis of the selected case. The rationale for case study designs, rather than more expansive designs such as surveys, is that the researcher is interested in investigating the particularity of a case, that is, the unique attributes that define an event, individual, group, organisation or programme.2 Second, case study is conducted in natural settings where people meet, interact and change their perceptions over time. The use of the case study design is a choice in favour of ‘maintaining the naturalness of the research situation and the natural course of events’ (p177).20

Third, case study assumes that a case under investigation is entangled with the context in which it is embedded. This context entails a number of interconnected processes that cannot be disassociated from the case, but rather are part of the study. The case study researcher is interested in understanding how and why such processes take place and, consequently, uncovering the interactions between a case and its context. Research questions concerning how and why phenomena occur are particularly appropriate in case study research.3

Fourth, case study encourages the researcher to use a variety of methods and data types in a single study.20 21 These can be solely qualitative, solely quantitative or a mixture of both. The latter option allows the researcher to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the case and improve the accuracy of the findings. The four above-mentioned key features of case study are shown in table 1, using the example of a mixed methods case study evaluation.22

Table 1.

Key features of case study as presented by Shultz et al 22

| Feature | How the feature is reflected in the study |

| In depth |

|

| Natural setting |

|

| Focus on context |

|

| Combination of methods |

|

There are many potential applications for case study research. While often misconstrued as having only an exploratory role, case study research can be used for descriptive and explanatory research (p7–9).3 Family medicine and community health researchers can use case study research for evaluating a variety of educational programmes, clinical programmes or community programmes.

Case study illustration from family medicine

In the featured study, Japanese family medicine residents received standardised patient instructor-based training in female breast, pelvic, male genital and prostate examinations as part of an international training collaboration to launch a new family medicine residency programme.22 From family medicine residents, trainers and staff, the authors collected and analysed data from post-training feedback, semistructured interviews and a web-based questionnaire. While the programme was perceived favourably, they noted barriers to reinforcement in their home training programme, and taboos regarding gender-specific healthcare appear as barriers to implementing a similar programme in the home institution.

A step-by-step description of the process of carrying out a case study

As shown in table 2 and illustrated using the article by Shultz et al,22 case study research generally includes 10 steps. While commonly conducted in this order, the steps do not always occur linearly as data collection and analysis may occur over several iterations or implemented with a slightly different order.

Table 2.

Ten steps for conducting a case study

| Step | Description | ||

| 1 | Conduct a literature review. |

|

|

| 2 | Formulate the research questions. |

|

|

| 3 | Ensure that a case study is appropriate. |

|

|

| 4 | Determine the type of case study design. |

|

|

| 5 | Define the boundaries of the case(s) and select the case(s). |

|

|

| 6 | Prepare to collect data. |

|

|

| 7 | Collect and organise the data. |

|

|

| 8 | Analyse the data. |

|

|

| 9 | Write the case study report. |

|

|

| 10 | Appraise quality. |

|

|

SPI, standardised patient instructor.

Step 1. Conduct a literature review

During the literature review, researchers systematically search for publications, select those most relevant to the study’s purpose, critically appraise them and summarise the major themes. The literature review helps researchers ascertain what is and is not known about the phenomenon under study, delineate the scope and research questions of the study, and develop an academic or practical justification for the study.23

Step 2. Formulate the research questions

Research questions critically define in operational terms what will be researched and how. They focus the study and play a key role in guiding design decisions. Key decisions include the case selection and choice of a case study design most suitable for the study. According to Fraenkel et al,24 the key attributes of good research questions are (1) feasibility, (2) clarity, (3) significance, (4) connection to previous research identified in the literature and (5) compliance with ethical research standards.

Step 3. Ensure that a case study is appropriate

Before commencing the study, researchers should ensure that case study design embodies the most appropriate strategy for answering the study questions. The above-noted four key features—in depth examination of phenomena, naturalness, a focus on context and the use of a combination of methods—should be reflected in the research questions as well as subsequent design decisions.

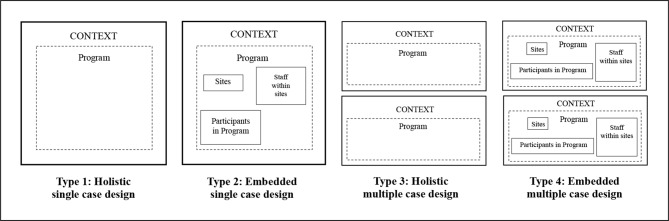

Step 4. Determine the type of case study design

Researchers need to choose a specific case study design. Sometimes, researchers may define the case first (step 5), for example, in a programme evaluation, and the case may need to be defined before determining the type. Yin’s3 typology is based on two dimensions, whether the study will examine a single case or multiple cases, and whether the study will focus on a single or multiple units of analysis. Figure 1 illustrates these four types of design using a hypothetical example of a programme evaluation. Table 3 shows an example of each type from the literature.

Figure 1.

Types of case study designs.3 21

Table 3.

Examples of published studies using the four types of case study designs suggested by Yin3

| Study example | Type of case study design | Study aim | Methodological features |

| Little et al 44 | Holistic single case. | To evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of a prenatal visit programme for Japanese women with limited English skills. | Survey and interview data were collected from women attending the programme. The programme (ie, the case) was the sole unit of analysis of the study. |

| Shultz et al 22 | Embedded single case. | To evaluate the perceived feasibility and impact of an SPI programme providing training in sexual healthcare examinations to Japanese family medicine residents. | Quantitative and qualitative data were gathered from groups of participants directly involved with the programme (ie, trainers in the programme and Japanese residents attending the programme) or whose work was affected by the outcomes of the programme (ie, medical and nursing staff at the residents’ workplace). The programme (ie, the case) was the core unit of analysis of the study and the groups of participants were subunits of analysis in the programme. |

| Peterson et al 45 | Holistic multiple case. | To identify and describe factors associated with the use of prevention research in seven public health programmes. | Seven programmes were compared in terms of the characteristics of research utilisation, including related barriers and facilitators. Archival, observational and interview data were collected from stakeholders involved in the design, implementation and evaluation of the programme. Each programme (ie, cases) constituted a unit of analysis of the study. |

| Shea et al 46 | Embedded multiple case. | To explore factors considered by primary care providers when assessing the added value of a health-related quality-of-life information technology application for geriatric patients. | Three primary care practices were examined using quantitative and qualitative data sources, such as surveys, observations, audio recordings and semistructured interviews. Data were collected from several groups of participants, including providers, clinical and administrative staff, and patients. The three primary care practices (ie, cases) were the core units of analysis of the study and the groups of participants were subunits embedded within the practices. |

SPI, standardised patient instructor.

In type 1 holistic single case design, researchers examine a single programme as the sole unit of analysis. In type 2 embedded single case design, the interest is not exclusively in the programme, but also in its different subunits, including sites, staff and participants. These subunits constitute the range of units of analysis. In type 3 holistic multiple case design, researchers conduct a within and cross-case comparison of two or more programmes, each of which constitutes a single unit of analysis. A major strength of multiple case designs is that they enable researchers to develop an in depth description of each case and to identify patterns of variation and similarity between the cases. Multiple case designs are likely to have stronger internal validity and generate more insightful findings than single case designs. They do this by allowing ‘examination of processes and outcomes across many cases, identification of how individual cases might be affected by different environments, and the specific conditions under which a finding may occur’ (p583).25 In type 4 embedded multiple case design, a variant of the holistic multiple case design, researchers perform a detailed examination of the subunits of each programme, rather than just examining each case as a whole.

Step 5. Define the boundaries of the case(s) and select the case(s)

Miles et al 26 define a case as ‘a phenomenon of some sort occurring in a bounded context’ (p28). What is and is not the case and how the case fits within its broader context should be explicitly defined. As noted in step 4, this step may occur before choice of the case study type, and the process may actually occur in a back-and-forth fashion. A case can entail an individual, a group, an organisation, an institution or a programme. In this step, researchers delineate the spatial and temporal boundaries of the case, that is, ‘when and where it occurred, and when and what was of interest’ (p390).9 Aside from ensuring the coherence and consistency of the study, bounding the case ensures that the planned research project is feasible in terms of time and resources. Having access to the case and ensuring ethical research practice are two central considerations in case selection.1

Step 6. Prepare to collect data

Before beginning the data collection, researchers need a study protocol that describes in detail the methods of data collection. The protocol should emphasise the coherence between the data collection methods and the research questions. According to Yin,3 a case study protocol should include (1) an overview of the case study, (2) data collection procedures, (3) data collection questions and (4) a guide for the case study report. The protocol should be sufficiently flexible to allow researchers to make changes depending on the context and specific circumstances surrounding each data collection method.

Step 7. Collect and organise the data

While case study is often portrayed as a qualitative approach to research (eg, interviews, focus groups or observations), case study designs frequently rely on multiple data sources, including quantitative data (eg, surveys or statistical databases). A growing number of authors highlight the ways in which the use of mixed methods within case study designs might contribute to developing ‘a more complete understanding of the case’ (p902),21 shedding light on ‘the complexity of a case’ (p118)27 or increasing ‘the internal validity of a study’ (p6).1 Guetterman and Fetters21 explain how a qualitative case study can also be nested within a mixed methods design (ie, be considered the qualitative component of the design). An interesting strategy for organising multiple data sources is suggested by Yin.3 He recommends using a case study database in which different data sources (eg, audio files, notes, documents or photographs) are stored for later retrieval or inspection. See guidance from Creswell and Hirose28 for conducting a survey and qualitative data collection in mixed methods and DeJonckheere29 on semistructured interviewing.

Step 8. Analyse the data

Bernard and Ryan30 define data analysis as ‘the search for patterns in data and for ideas that help explain why these patterns are there in the first place’ (p109). Depending on the case study design, analysis of the qualitative and quantitative data can be done concurrently or sequentially. For the qualitative data, the first step of the analysis involves segmenting the data into coding units, ascribing codes to data segments and organising the codes in a coding scheme.31 Depending on the role of theory in the study, an inductive, data-driven approach can be used where meaning is found in the data, or a deductive, concept-driven approach can be adopted where predefined concepts derived from the literature, or previous research, are used to code the data.32 The second step involves searching for patterns across codes and subsets of respondents, so major themes are identified to describe, explain or predict the phenomenon under study. Babchuk33 provides a step-by-step guidance for qualitative analysis in this issue. When conducting a single case study, the within-case analysis yields an in depth, thick description of the case. When the study involves multiple cases, the cross-comparison analysis elicits a description of similarities and divergence between cases and may generate explanations and theoretical predictions regarding other cases.26

For the quantitative part of the case study, data are entered in statistical software packages for conducting descriptive or inferential analysis. Guetterman34 provides a step-by-step guidance on basic statistics. In case study designs where both data strands are analysed simultaneously, analytical techniques include pattern matching, explanation building, time-series analysis and creating logic models (p142–167).3

Step 9. Write the case study report

The case study report should have the following three characteristics. First, the description of the case and its context should be sufficiently comprehensive to allow the reader to understand the complexity of the phenomena under study.35 Second, the data should be presented in a concise and transparent manner to enable the reader to question, or to re-examine, the findings.36 Third, the report should be adapted to the interests and needs of its primary audience or audiences (eg, academics, practitioners, policy-makers or funders of research). Yin3 suggests six formats for organising case study reports, namely linear-analytic, comparative, chronological, theory building, suspense and unsequenced structures. To facilitate case transferability and applicability to other similar contexts, the case study report must include a detailed description of the case.

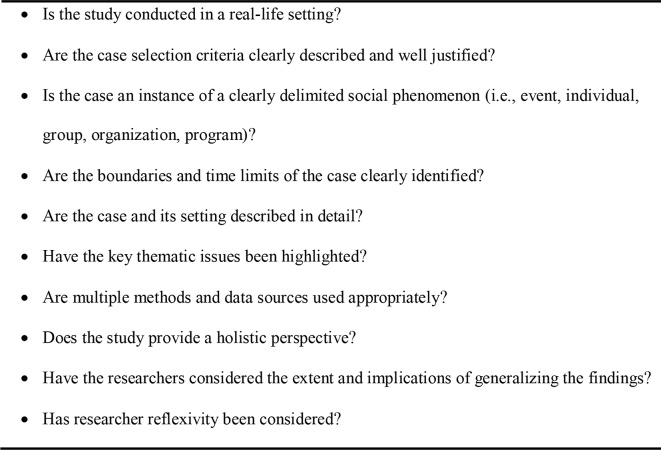

Step 10. Appraise quality

Although presented as the final step of the case study process, quality appraisal should be considered throughout the study. Multiple criteria and frameworks for appraising the quality of case study research have been suggested in the literature. Yin3 suggests the following four criteria: construct validity (ie, the extent to which a study accurately measures the concepts that it claims to investigate), internal validity (ie, the strength of the relationship between variables and findings), external validity (ie, the extent to which the findings can be generalised) and reliability (ie, the extent to which the findings can be replicated by other researchers conducting the same study). Yin37 also suggests using two separate sets of guidelines for conducting case study research and for appraising the quality of case study proposals. Stake4 presents a 20-item checklist for critiquing case study reports, and Creswell and Poth38 and Denscombe39 outline a number of questions to consider. Since these quality frameworks have evolved from different disciplinary and philosophical backgrounds, the researcher’s approach should be coherent with the epistemology of the study. Figure 2 provides a quality appraisal checklist adapted from Creswell and Poth38 and Denscombe.39

Figure 2.

Checklist for evaluating the quality of a case study.38 39

Discussion

The challenges to conducting case study research include rationalising the literature based on literature review, writing the research questions, determining how to bound the case, and choosing among various case study purposes and designs. Factors held in common with other methods include analysing and presenting the findings, particularly with multiple data sources.

Other resources

Resources with more in depth guidance on case study research include Merriam,17 Stake4 and Yin.3 While each reflects a different perspective on case study research, they all provide useful guidance for designing and conducting case studies. Other resources include Creswell and Poth,38 Swanborn2 and Tight.40 For mixed methods case study designs, Creswell and Plano Clark,27 Guetterman and Fetters,21 Luck et al,6 and Plano Clark et al 41 provide guidance. Byrne and Ragin’s42 The SAGE Handbook of Case-Based Methods and Mills et al’s43 Encyclopedia of case study research provide guidance for experienced case study researchers.

Conclusions

Family medicine and community health researchers engage in a wide variety of clinical, educational, research and administrative programmes. Case study research provides a highly flexible and powerful research tool to evaluate rigorously many of these endeavours and disseminate this information.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the help of Dick Edelstein and Marie-Hélène Paré in editing the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Correction notice: This article has been corrected. Reference details have been updated.

Contributors: SF and MDF conceived and drafted the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, et al. The case study approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:1–9. 10.1186/1471-2288-11-100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Swanborn P. Case study research: what, why, and how? Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yin R. Case study research: design and methods. 5th edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stake R. The art of case study research. Thousandthousand Oaksoaks. CA: Sage, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Walshe CE, Caress AL, Chew-Graham C, et al. Case studies: a research strategy appropriate for palliative care? Palliat Med 2004;18:677–84. 10.1191/0269216304pm962ra [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Luck L, Jackson D, Usher K. Case study: a bridge across the paradigms. Nurs Inq 2006;13:103–9. 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2006.00309.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ford L, Golden M, Ray E. The case study in health communication research : Whaley B, Research methods in health communication: principles and application. New York: Routledge, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Keen J, studies C. In: Pope C, Mays N, editors. : Qualitative research in health care. 3rd edn Oxford: Blackwell, 2006: 112–20. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tight M. Case study research : Wyse D, Selwyn N, Smith E, et al., The BERA/SAGE Handbook of educational research. London: Sage, 2017: 376–94. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Adelman C, Eurepos G, Eurepos G, et al. Chicago School : Mills A, Eurepos G, Wiebe E, et al., Encyclopedia of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010: 140–4. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Blatter J. Case study : Given LM, The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2008: 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stark S, Torrance H. Case study : Somekh B, Lewin C, Research methods in the social sciences. London: Sage, 2005: 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Platt J. “Case Study” in American Methodological Thought. Current Sociology 1992;40:17–48. 10.1177/001139292040001004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Judging the quality of case study reports. Int J Qual Stu Edu 1990;3:53–9. 10.1080/0951839900030105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eisenhardt KM. Building theories from case study research. Acad Manage Rev 1989;14:532–50. 10.5465/amr.1989.4308385 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yin RK. The case study crisis: some answers. Adm Sci Q 1981;26:58–65. 10.2307/2392599 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Merriam S. Qualitative research and case study applications in education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yin R. Case study research: design and methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yazan B. Three approaches to case study methods in education: Yin, Merriam, and stake. The Qualitative Report 2015;20:134–52. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hijmans E, Wester F. Comparing the case study with other methodologies : Mills A, Eurepos G, Wiebe E, Encyclopedia of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010: 176–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guetterman TC, Fetters MD. Two methodological approaches to the integration of mixed methods and case study designs: a systematic review. Am Behav Sci 2018;62:900–18. 10.1177/0002764218772641 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shultz CG, Chu MS, Yajima A, et al. The cultural context of teaching and learning sexual health care examinations in Japan: a mixed methods case study assessing the use of standardized patient instructors among Japanese family physician trainees of the Shizuoka family medicine program. Asia Pac Fam Med 2015;14 10.1186/s12930-015-0025-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boote DN, Beile P. Scholars before researchers: on the centrality of the dissertation literature review in research preparation. Educ Res 2005;34:3–15. 10.3102/0013189X034006003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fraenkel J, Wallen N, Hyun H. How to design and evaluate research in education. 5th edn New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chmiliar L. Multiple-case designs : Eurepos G, Mills A, Eurepos G, Encyclopedia of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010: 582–4. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Miles M, Huberman A, Saldaña J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. 3rd edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Creswell J, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 3rd edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Creswell J, Hirose M. Approach to mixed methods survey design. Fam Med Com Health 2019;7:e000086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. DeJonckheere M, Vaughn LM. Fundamentals of semi-structured interviews. Fam Med Com Health 2019;7:e000057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bernard H, Ryan G. Analyzing qualitative data: systematic approaches. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tesch R. Qualitative research: analysis types and software tools. Abingdon: Routledge Falmer, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gibbs G. Analysing qualitative data. London: Sage, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Babchuk W. Fundamentals of qualitative analysis. Fam Med Com Health 2019;7:e000040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guetterman T. Fundamentals of biostatistical analysis. Fam Med Com Health 2019;7:e000067. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Baxter P, Jack S. Qualitative case study methodology: study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report 2008;13:544–99. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gray D. Doing research in the real world. London: Sage, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yin RK. Enhancing the quality of case studies in health services research. Health Serv Res 1999;34:1209–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Creswell J, Poth C. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. 4th edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Denscombe M. The good research guide for small-scale social research projects. 4th edn Berkshire: Open University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tight M. Understanding case study research: Small-scale research with meaning. London: Sage, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Plano Clark VL, Foote LA, Walton JB, et al. Intersecting mixed methods and case study research: design possibilities and challenges. Int J Mult Res Approaches 2018;10:14–29. 10.29034/ijmra.v10n1a1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Byrne D, Ragin C, The SAGE handbook of case-based methods. London: Sage, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mills A, Eurepos G, Wiebe E, Encyclopedia of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Little SH, Motohara S, Miyazaki K, et al. Prenatal group visit program for a population with limited English proficiency. J Am Board Fam Med 2013;26:728–37. 10.3122/jabfm.2013.06.130005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Peterson JC, Rogers EM, Cunningham-Sabo L, et al. A framework for research utilization applied to seven case studies. Am J Prev Med 2007;33:S21–S34. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shea CM, Halladay JR, Reed D, et al. Integrating a health-related-quality-of-life module within electronic health records: a comparative case study assessing value added. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12 10.1186/1472-6963-12-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]