Abstract

Background

Micronutrients are known to modulate host immunity, and there is limited literature on this association in the context of dengue virus infection (DENV).

Methods

Using a nested case-control design in a surveillance program, we measured the following: anthropometry; nutritional biomarkers including serum ferritin, soluble transferrin receptor, retinol-binding protein (RBP), 25-hydroxy vitamin D, folate, and vitamin B12; and a panel of immune response markers. We then compared these measures across 4 illness categories: healthy control, nonfebrile DENV, other febrile illness (OFI), and apparent DENV using multivariate polytomous logistic regression models.

Results

Among 142 participants, serum ferritin (ng/mL) was associated with apparent DENV compared to healthy controls (odds ratio [OR], 2.66; confidence interval [CI], 1.53–4.62; P = .001), and RBP concentrations (µmol/L) were associated with apparent DENV (OR, 0.03; CI, 0.00–0.30; P = .003) and OFI (OR, 0.02; CI, 0.00–0.24; P = .003). In a subset of 71 participants, interleukin-15 levels (median fluorescent intensity) were positively associated with apparent DENV (OR, 1.09; CI, 1.03–1.14; P = .001) and negatively associated with nonfebrile DENV (OR, 0.89; CI, 0.80–0.99; P = .03) compared to healthy controls.

Conclusions

After adjusting for the acute-phase response, serum ferritin and RBP concentrations were associated with apparent DENV and may represent biomarkers of clinical importance in the context of dengue illness.

Keywords: dengue, micronutrients

In a nested case-control study, biomarkers of serum ferritin, vitamin A (RBP), and IL-15 are associated with apparent DENV infection, yet not with nonfebrile DENV, and may play a role in the immunopathology of dengue illness.

Dengue virus (DENV) infection affects an estimated 390 million people each year with 14% of cases occurring in the Americas [1]. More than half of the global population lives in tropical regions at risk for dengue transmission, and the burden of illness is disproportionately higher for communities with limited resources [2]. Transmission of the 4 distinct DENV serotypes is primarily by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, and inoculation can result in a range of clinical presentations [3]. Many DENV infections are inapparent, either without any symptoms (asymptomatic) or without requiring clinical care (subclinical). The clinical hallmark of apparent or symptomatic dengue is acute fever and is further classified by severity into categories of dengue without warning signs (DNWS), dengue with warning signs (DWWS), and severe dengue (SD) [4].

Of the estimated annual cases, 96 million are clinically apparent, resulting in 20 000 deaths attributable to plasma leakage, hemorrhage, shock, and organ impairment [1]. More severe clinical presentations and outcomes of DENV infection are influenced by prior DENV infection with a heterologous serotype [5, 6] and by the host immune response [7]. Although a dengue vaccine candidate Dengvaxia (CYD-TDV; Sanofi Pasteur) has been licensed in more than 20 countries, concerns surrounding increased risks for seronegative individuals have led to vaccine hesitancy, defined as the delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccination services [8, 9]. Given the challenges associated with dengue vaccine administration and no specific treatment, researchers have long sought to identify biomarkers to predict DENV infection outcomes. The ability to identify and modify such biomarkers may represent treatment opportunities to prevent the progression of DENV infection severity.

Micronutrients share an interdependent relationship with the host immune response and infection. The acute-phase reaction (APR) accompanying acute viral infection temporarily alters circulating concentrations of some nutrients, including iron and vitamin A, which precludes accurate assessment during infection [10]. These measures can be adjusted using circulating concentrations of acute-phase proteins [11, 12]. Some micronutrient deficiencies impair the host immune response and are associated with more severe infection outcomes. Iron deficiency impacts the function of phagocytes and the proliferation of T-cells [13] as well the cytokine activity of all stages of pathogenesis [14]. In response to some viral agents, vitamin A deficiency reduces phagocytic activity and impairs cell-mediated immunity [15]. Vitamin A deficiency is also associated with increased prevalence of measles, diarrheal infections, and anemia [16, 17]. Vitamin D deficiency impairs macrophage maturation and phagocytic response, production of proinflammatory cytokines, and cell-mediated immunity [18–20]. Folate and vitamin B12 play roles in deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis and genome methylation, and deficiency in these nutrients affects cell-mediated immunity [21, 22].

Several studies have examined the association between malnutrition and DENV infection [23], but few have investigated micronutrients specifically [24, 25]. A systematic review examined existing evidence for the role of micronutrients and summarized that limited literature, small sample sizes, and inconsistent results constrain the ability to draw conclusions [26]. This hypothesis-generating study seeks to expand on available literature by examining a panel of micronutrients in the context of DENV infection. We also included a panel of immune response markers, because certain soluble factors play critical roles in driving either protective or pathologic responses [27, 28]. In a nested case-control analysis within a surveillance program, we compared nutritional and immune response markers among individuals identified as DENV infection positive (DENV+) cases or DENV infection negative (DENV−) controls, either presenting with or without acute fever.

METHODS

Study Population

Details from the parent study [29, 30], including participant recruitment, DENV diagnostic tests, and Institutional Review Board approvals, are described in the Supplementary Information. In brief, participants recruited from clinics were defined as index cases. Additional participants, defined as associates, were recruited by visiting the households and 4 neighboring households of randomly selected index cases. At enrollment, trained staff collected demographic data, anthropological measurements, and venous blood samples. Stored serum was used for biochemical analyses. In addition to approvals from other institutions, the analyses described here were approved by the Cornell University Institutional Review Board (protocol no. 1411005125A001).

For the nested case-control analysis, DENV+ cases were matched on age and sex with DENV− controls. The DENV+ cases were defined by a positive quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) result. The DENV− controls were defined as negative based on PCR and DENV nonstructural protein 1 (NS1) antigen, immunoglobulin (Ig)M, and IgG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) results. No case was matched to a control from the same household.

Nutritional Status

Anthropometric Measures

Anthropometric measurements, including height (m), weight (kg), mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC, cm), and waist circumference (cm) were collected using standardized procedures. Conventional cutoffs, according to the World Health Organization, were used to categorize variables of stature, body mass index (BMI), and waist circumference [31].

Micronutrient Biomarkers

Assessment of serum samples at the Human Nutritional Chemistry Service Laboratory at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York included iron status measuring ferritin and soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR), vitamin A retinol-binding protein (RBP), 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25(OH)D), folate, and vitamin B12. Ferritin, folate, and vitamin B12 concentrations were evaluated by chemiluminescence using the Immulite 2000 immunoassay system (Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, Deerfield, IL). The sTfR (TFC-94; Ramco Laboratories Inc., Stafford, TX), RBP (DRB400; R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN), and 25(OH)D concentrations (AC-57SF1; Immunodiagnostic Systems, Boldon, UK) were measured by ELISA. Total body iron (TBI) was calculated using the approach developed by Cook et al [32] with concentrations of sTfR and APR-adjusted serum ferritin:

| (1) |

Immune Response Markers

Acute Phase Proteins

C-reactive protein (CRP) and alpha-1 acid glycoprotein (AGP) were measured for ferritin and vitamin A APR-adjustment. The CRP concentrations were evaluated by chemiluminescence using the Immulite 2000 immunoassay system. The AGP concentrations were measured by colorimetric assay using the Dimension Xpand Plus chemistry analyzer (Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics).

Immune Response Biomarkers

A premixed panel of 29-target cytokines and chemokines were measured by magnetic bead multiplex assay, (HCYTMAG60PMX29BK; EMD Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA) and reported in median fluorescent intensity (MFI) [33]. Measured markers are described in the Supplementary Information.

Statistical Analyses

The study outcome was grouped into 4 illness categories based on acute DENV infection and fever reported within the past 7 days: healthy control (DENV− without fever); nonfebrile dengue (DENV+ without fever); other febrile illness ([OFI] DENV− with fever); and apparent dengue (DENV+ with fever). Primary exposures included anthropometry measurements, micronutrient assessment, and immune response markers.

Normality was assessed for the distribution of all continuous variables of interest. For descriptive analysis, data were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and as percentages for categorical variables.

The non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to test for differences in continuous exposure variables across outcome illness categories. Multivariate analysis was performed using polytomous logistic regression to model the outcome illness categories with either micronutrient biomarkers (n = 142) or immune response markers (n = 71), and odds ratios (ORs) and confidence intervals (CIs) are reported. We used an approach based on Rothman and Greenland’s recommendations to evaluate potential confounders [34]. In brief, variables with a univariate P < .20 association with the outcome along with any known or potential risk factors for the outcome were considered as potential confounders. Variables with a P < .05 were retained in the final multivariate model. P < .05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The Cornell Institute for Social and Economic Research reproduced this analysis.

RESULTS

Population Characteristics

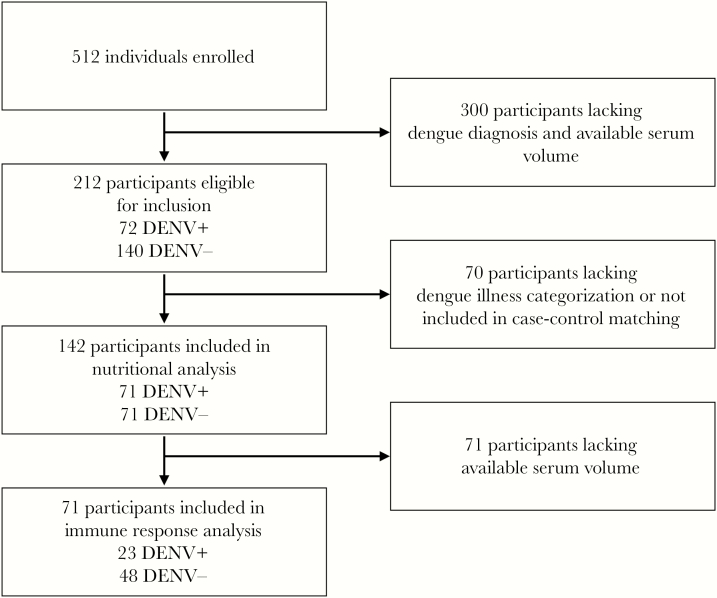

A total of 71 confirmed cases of acute DENV infection and 71 matched controls (n = 142 individuals) were included in this study and grouped into 4 illness categories: healthy control (n = 57); nonfebrile dengue (n = 18); OFI (n = 14); and apparent dengue (n = 53). A detailed breakdown of participants is provided in Figure 1. Descriptive data on participant characteristics for the total sample and for illness categories are provided in Table 1. There were no differences in composition by sex in the overall sample (n = 142; males 53.5%; females 46.5%; P = .40). Among cases of DENV infection (n = 71), there were no differences in composition by sex (males 53.5%; females 46.5%; P = .55); however, more males presented with apparent dengue (62.3%) and more females presented with nonfebrile dengue (72.2%; P = .015). More of the included participants were classified as adults ≥19 years (65.5%) than as children and adolescents <19 years (34.5%; P = .0002), and the distribution of these age groups across illness groups differed significantly (P = .002). Larger proportions of participants with OFI (78.6%) or apparent DENV infection (86.8%) were index cases recruited in clinical settings, and, similarly, larger proportions of participants categorized as healthy controls (100%) or with nonfebrile DENV infection (88.9%) were associates of index cases recruited in households (P < .0001). Across illness categories, there were no significant differences in previous participant or household member DENV infection or participant comorbidities.

Figure 1.

Selection criteria for included participants. DENV, dengue virus.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants Across Illness Categories

| Overall | Healthy Control | Nonfebrile DENV | OFI | Apparent DENV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic, n (%) | n = 142 | Fever−/ DENV− n = 57 | Fever−/ DENV+ n = 18 | Fever+/ DENV− n = 14 | Fever+/ DENV+ n = 53 | P Value a |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <19 | 49 (34.5) | 12 (21.1) | 3 (16.7) | 8 (57.1) | 26 (49.1) | .002 |

| ≥19 | 93 (65.5) | 45 (78.9) | 15 (83.3) | 6 (42.9) | 27 (50.9) | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 76 (53.5) | 30 (52.6) | 5 (27.8) | 8 (57.1) | 33 (62.3) | .09 |

| Female | 66 (46.5) | 27 (47.4) | 13 (72.2) | 6 (42.9) | 20 (37.7) | |

| Recruitment | ||||||

| Index Case | 59 (41.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.1) | 11 (78.6) | 46 (86.8) | <.0001 |

| Associate | 83 (58.5) | 57 (100.0) | 16 (88.9) | 3 (21.4) | 7 (13.2) | |

| History of DENV infection | ||||||

| Participant (ever) | 24 (17.3) | 9 (16.4) | 3 (16.7) | 3 (23.1) | 9 (17.0) | .93 |

| Participant household member (within 4 weeks) | 33 (23.7) | 16 (28.6) | 6 (33.3) | 2 (15.4) | 9 (17.3) | .35 |

| Medical History | ||||||

| Allergies | 37 (26.2) | 13 (22.8) | 4 (22.2) | 6 (42.9) | 14 (26.9) | .48 |

| Hypertension | 8 (5.6) | 3 (5.3) | 3 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.8) | .19 |

| Asthma | 6 (4.2) | 2 (3.5) | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.7) | .86 |

| Cancer | 3 (2.1) | 2 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) | 1.00 |

| Diabetes | 4 (2.8) | 1 (1.8) | 2 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) | .29 |

Abbreviations: DENV, dengue virus; OFI, other febrile illness.

a P values are from Fisher’s exact test for categorical data comparisons.

Symptoms

A comparison of clinical symptoms across illness categories is presented in Table 2. More than half of participants in the OFI and apparent DENV illness categories reported fever within the previous 7 days, headache, drowsiness, myalgia, retro-orbital pain, and nausea; each differed significantly across illness groups (P < .0001). Abdominal pain as well as episodes of vomiting and diarrhea were also reported by more participants in the OFI and apparent DENV categories compared to nonfebrile categories (P < .0001). Among participants with apparent dengue, 30.2% reported rash, which accounted for almost all instances of reported rash (P < .0001). Symptoms of cough, rhinitis, and any instances of bleeding were not significantly different across illness categories.

Table 2.

Reported Symptoms Across Illness Categories

| Healthy Control | Nonfebrile DENV | OFI | Apparent DENV | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic, n (%) | Overall n = 142 | Fever−/ DENV− n = 57 | Fever−/ DENV+ n = 18 | Fever+/ DENV− n = 14 | Fever+/ DENV+ n = 53 | P Valuea |

| Fever reported within last 7 days | 67 (48.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (100.0) | 53 (100.0) | <.0001 |

| Headache | 80 (56.3) | 15 (26.3) | 4 (22.2) | 13 (92.9) | 48 (90.6) | <.0001 |

| Drowsiness | 76 (53.5) | 15 (26.3) | 3 (16.7) | 11 (78.6) | 47 (88.7) | <.0001 |

| Myalgia | 68 (47.9) | 8 (14.0) | 4 (22.2) | 11 (78.6) | 45 (84.9) | <.0001 |

| Retro-orbital pain | 60 (42.6) | 8 (14.3) | 2 (11.1) | 8 (57.1) | 42 (79.3) | <.0001 |

| Nausea | 50 (35.2) | 4 (7.0) | 1 (5.6) | 10 (71.4) | 35 (66.0) | <.0001 |

| Abdominal pain | 50 (35.2) | 13 (22.8) | 1 (5.6) | 6 (42.9) | 30 (56.6) | <.0001 |

| Vomiting | 25 (17.6) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (28.6) | 20 (37.7) | <.0001 |

| Rash | 17 (12.1) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (30.2) | <.0001 |

| Cough | 29 (20.4) | 8 (14.0) | 2 (11.1) | 4 (28.6) | 15 (28.3) | .18 |

| Diarrhea | 21 (14.8) | 4 (7.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (14.3) | 15 (28.3) | .003 |

| Rhinitis | 16 (11.3) | 5 (8.8) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (28.6) | 7 (13.2) | .07 |

| Bleedingb | 5 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.1) | 4 (7.6) | .08 |

Abbreviations: DENV, dengue virus; OFI, other febrile illness.

a P values are from Fisher’s exact test for categorical data comparisons.

bBleeding refers to any reported bleeding.

Anthropometry

Data on anthropometry for adults ≥19 years and children and adolescents <19 years are presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively; anthropometry data were available for all 142 included study participants. The median BMI in adults was 26.4 kg/m2 with an IQR between 23.4 and 29.8. More than 50% of included adults were categorized as overweight or obese (≥25 kg/m2). Among adults and also children and adolescents, there were no significant differences in weight, height, BMI, waist circumference, or MUAC between across illness categories (P > .05).

Table 3.

Anthropometry Across Illness Categories: Adults (≥19 Years)

| Overall | Healthy Control | Nonfebrile DENV | OFI | Apparent DENV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic, Median ± IQR or n (%) | n = 93 | Fever−/DENV− n = 45 | Fever−/DENV+ n = 15 | Fever+/DENV− n = 6 | Fever+/DENV+ n = 27 | P Valuea |

| Weight, kg | 68.0 (59.8–78.3) | 66.0 (55.9–77.2) | 71.6 (64.0–85.6) | 65.4 (59.8–68.0) | 67.6 (63.4–79.3) | .32 |

| Height, cm | 160.0 (155.0–166.0) | 160.0 (156.0–163.5) | 158.0 (156.0–161.0) | 159.0 (153.0–160.0) | 160.0 (154.0–169.0) | .80 |

| <150 cm | 9 (9.7) | 5 (11.1) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (7.4) | .72 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.4 (23.4–29.8) | 26.2 (23.6–29.8) | 29.8 (24.9–33.4) | 25.2 (23.2–27.2) | 27.0 (23.1–29.7) | .35 |

| Underweight <18.5 | 4 (4.3) | 2 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (3.7) | .67 |

| Normal 18.5 ≤ 25 | 34 (36.6) | 18 (40.0) | 4 (26.7) | 2 (33.3) | 10 (37.0) | |

| Overweight 25 ≤ 30 | 32 (34.4) | 16 (35.6) | 4 (26.7) | 2 (33.3) | 10 (37.0) | |

| Obese ≥30 | 23 (24.7) | 9 (20.0) | 7 (46.7) | 1 (16.7) | 6 (22.2) | |

| Waist circumference, cm | 90.0 (82.0–98.0) | 88.0 (79.5–99.0) | 91.4 (81.6–101.0) | 88.7 (88.0–93.0) | 90.0 (83.0–98.0) | .83 |

| Increasedb | 54 (58.1) | 26 (57.8) | 12 (80.0) | 3 (50.0) | 13 (48.1) | .24 |

| Substantially increasedc | 33 (35.5) | 12 (26.7) | 9 (60.0) | 3 (50.0) | 9 (33.3) | .10 |

| MUAC, cm | 30.0 (27.0–32.3) | 30.0 (26.6–32.5) | 31.5 (27.5–36.0) | 29.2 (26.8–31.0) | 30.0 (28.0–32.0) | .43 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DENV, dengue virus; IQR, interquartile range; MUAC, mid-upper arm circumference; OFI, other febrile illness.

a P values from Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous comparisons; Fisher’s exact test for categorical comparisons.

bIncreased waist circumference was defined as >94 cm for men and >80 cm for women.

cSubstantially increased waist circumference was defined as >102 cm for men and >88 cm in women.

Table 4.

Anthropometry Across Illness Categories: Children And Adolescents (<19 Years)

| Overall | Healthy Control | Nonfebrile DENV | OFI | Apparent DENV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic, Median ± IQR or n (%) | n = 49 | Fever−/DENV− n = 12 | Fever−/DENV+ n = 3 | Fever+/DENV− n = 8 | Fever+/DENV+ n = 26 | P Valuea |

| Weight, kg | 49.8 (41.0–59.8) | 43.4 (37.5–52.5) | 51.3 (46.0–86.0) | 48.1 (40.1–60.5) | 49.9 (41.0–59.8) | .66 |

| Height, cm | 158.0 (150.5–164.0) | 152.5 (139.3–158.0) | 164.0 (154.0–168.0) | 158.5 (147.0–172.5) | 159.5 (152.0–164.0) | .29 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 19.5 (17.4–21.3) | 19.6 (16.9–21.0) | 19.4 (18.2–32.0) | 18.8 (17.4–20.4) | 19.9 (17.4–21.7) | .80 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 68.0 (64.0–75.2) | 68.3 (63.5–75.7) | 72.2 (64.0–100.0) | 69.5 (65.0–74.1) | 68.0 (62.0–75.2) | .77 |

| MUAC, cm | 23.5 (22.0–26.0) | 23.0 (21.0–24.8) | 25.0 (23.5–30.0) | 22.5 (21.5–25.5) | 24.0 (22.0–27.0) | .57 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DENV, dengue virus; IQR, interquartile range; MUAC, mid-upper arm circumference; OFI, other febrile illness.

a P values from Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous comparisons.

Micronutrient Status

Micronutrient and acute-phase protein biomarkers are described in Tables 5 and 6; micronutrient data were available for almost all of the 142 included participants. Serum ferritin, TBI, and RBP concentrations were adjusted for inflammation using the Thurnham correction factor approach described in the Supplementary Information section [11, 12]. Table 5 summarizes nutrient distributions for included participants and compares median nutrient concentrations across illness categories. Iron status was assessed by serum ferritin, sTfR, and TBI. Median serum ferritin for included participants was 96.2 µg/L (IQR, 45.5–211.0) and differed significantly across illness categories with the highest concentrations observed among those with apparent DENV infection (median 209.4 µg/L; IQR, 82.0–571.3; P = .0002). Likewise, TBI differed across illness groups with the highest concentration represented in the apparent DENV infection category (median 12.5 mg/kg; IQR, 8.9–15.4; P = .001). Serum RBP concentrations were lower in participants with apparent DENV (median 1.0 µmol/L; IQR, 0.9–1.3) compared to healthy control (median 1.2 µmol/L; IQR, 1.1–1.8) or nonfebrile DENV (median 1.5 µmol/L; IQR, 1.2–1.8) categories, and concentrations differed across illness categories (P = .0003). Serum vitamin D (25(OH)D) differed across illness groups (P = .02) with the lowest concentrations in the nonfebrile illness category (median 72.8 nmol/L; IQR, 63.3–86.3) and the highest concentrations in the apparent DENV infection category (median 87.1 nmol/L; IQR, 74.9–99.3). Acute-phase proteins CRP (P < .0001) and AGP (P < .0001) were significantly higher in febrile illness categories. The sTfR (P = .37), folate (P = .79), and vitamin B12 (P = .69) concentrations were not significantly different across illness categories.

Table 5.

Micronutrient Biomarkers Across Illness Categories

| Healthy Control | Nonfebrile DENV | OFI | Apparent DENV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic, Median (IQR) | n | Overall | Fever−/ DENV− n = 57 | Fever−/DENV+ n = 18 | Fever+/DENV− n = 14 | Fever+/DENV+ n = 53 | P Valuea |

| Ferritin (µg/L)b | 141 | 96.2 (45.5–211.0) | 72.5 (35.5–126.0) | 72.6 (40.9–144.8) | 66.8 (49.4–144.7) | 209.4 (82.0–571.3) | .0002 |

| sTfR (mg/L) | 141 | 4.1 (3.5–4.8) | 4.0 (3.4–4.7) | 4.2 (3.4–4.5) | 4.1 (3.2–4.5) | 4.3 (3.7–5.3) | .37 |

| TBI (mg/kg)b | 140 | 10.0 (7.1–13.1) | 8.7 (6.7–11.2) | 9.0 (6.7–10.8) | 9.2 (7.2–10.8) | 12.5 (8.9–15.4) | .001 |

| Folate (ng/mL) | 140 | 19.5 (15.4–29.5) | 19.7 (16.3–28.1) | 19.0 (14.5–30.4) | 18.5 (15.4–29.9) | 20.6 (15.2–31.3) | .79 |

| RBP (µmol/L)b | 141 | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | 1.2 (1.1–1.8) | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | 1.1 (0.8–1.3) | 1.0 (0.9–1.3) | .0003 |

| Vitamin B12 (pg/mL) | 138 | 343.5 (249.0–538.0) | 317.0 (248.0–486.0) | 377.5 (262.0–506.0) | 356.0 (258.0–716.0) | 343.5 (251.5–591.5) | .69 |

| 25(OH)D (nmol/L) | 141 | 80.8 (68.0–93.0) | 75.5 (63.5–86.0) | 72.8 (63.3–86.3) | 83.1 (66.8–100.3) | 87.1 (74.9–99.3) | .02 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 142 | 4.3 (1.0–12.3) | 2.1 (0.7–4.5) | 2.4 (0.7–6.5) | 10.0 (5.1–34.3) | 10.9 (4.2–26.5) | <.0001 |

| AGP (g/L) | 141 | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | <.0001 |

Abbreviations: AGP, alpha-1 acid glycoprotein; CRP, C-reactive protein; DENV, dengue virus; IQR, interquartile range; OFI, other febrile illness; RBP, retinol-binding protein; sTfR, soluble transferrin receptor; TBI, total body iron; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxy vitamin D.

a P values from Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous comparisons.

bAdjusted for acute-phase response using the Thurnham correction factor.

Table 6.

Multivariate Estimates of Micronutrients With Illness Category

| Overall | Healthy Control | Nonfebrile DENV | OFI | Apparent DENV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever−/DENV− | Fever−/DENV+ | Fever+/DENV− | Fever+/DENV+ | ||||||

| Exposure Variables | n = 141 | n = 57 | n = 18 | n = 14 | n = 53 | ||||

| Wald χ 2 | P Valuea | OR (95% CI) | P Valueb | OR (95% CI) | P Valueb | OR (95% CI) | P Valueb | ||

| Ferritin (ng/mL)c | 12.51 | .006 | Reference | 1.40 (.75–2.62) | .3 | 1.72 (0.83–3.57) | .14 | 2.66 (1.53–4.62) | .0006 |

| RBP (µmol/L)c | 13.04 | .005 | Reference | 2.74 (.49–15.40) | .25 | 0.02 (0.00–0.24) | .003 | 0.03 (.00–.30) | .003 |

| AGP (g/L)d | 26.00 | <.0001 | Reference | 0.99 (.79–1.24) | .92 | 1.95 (1.44–2.65) | <.0001 | 1.81 (1.42–2.30) | <.0001 |

Abbreviations: AGP, alpha-1 acid glycoprotein; CI, confidence interval; DENV, dengue virus; OFI, other febrile illness; OR, odds ratio; RBP, retinol-binding protein.

a P values obtained using a Wald χ 2 tests for independence.

b P values obtained from polytomous logistic regression, Type 3 analysis of effects. Each illness category compared to“healthy control” as the reference group. Model is adjusted for age, sex, and body mass index.

cAdjusted for acute-phase response using the Thurnham correction factor.

dAGP modeled as value per 0.1 g/L.

Polytomous logistic regression was then used to model the outcome illness categories with nutrient and acute-phase protein biomarkers (n = 141) for multivariate analysis using log-transformed variables of serum ferritin, TBI, RBP, 25(OH)D, CRP, and AGP. After adjusting the model for covariates of age, sex, and BMI, ORs for serum ferritin, RBP, and AGP with the illness category outcome remained significant (P < .05). The results of this model are shown in Table 6. Every unit increase of ferritin (ng/mL) resulted in a 2.66 odds increase in apparent DENV infection (CI, 1.53–4.62) compared to the reference illness category: healthy control (P = .001). In contrast, lower RBP concentrations (µmol/L) were associated with febrile illness categories OFI (OR, 0.02; CI, 0.00–0.24; P = .003) and apparent DENV (OR, 0.03; CI, 0.00–0.30; P = .003) compared to the healthy control reference group. Increased concentrations of AGP (g/L) were associated with increased odds for febrile illness categories OFI (OR, 1.95; CI, 1.44–2.65; P < .0001) and apparent DENV (OR, 1.81; CI, 1.42–2.30; P < .0001) compared to the healthy control reference group.

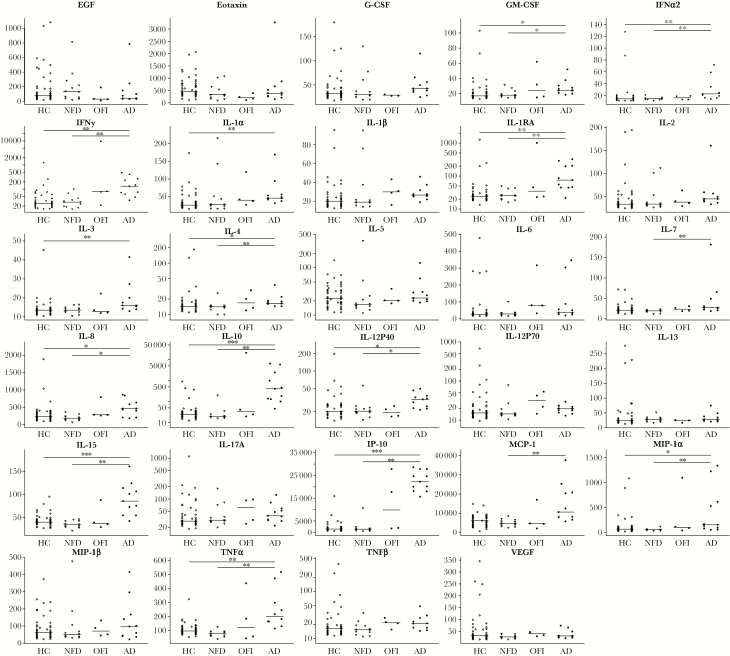

Immune Response Markers

Cytokine and chemokine biomarkers are described in Figure 2 and Table 7; data were available for 71 of the 142 included participants. The 71 participants with available data were similarly grouped by illness category: healthy control (n = 44); nonfebrile dengue (n = 12); OFI (n = 4); and apparent dengue (n = 11). Among the 29-panel biomarker assay, levels of 17 markers differed significantly across illness categories (P < .05) (Supplementary Table 1). In pairwise comparisons, levels of 15 markers differed significantly between apparent DENV and nonfebrile DENV infection categories (P < .05) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Immune response marker levels across illness categories. AD, Apparent DENV; DENV, Dengue virus; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; HC, Healthy control; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; IP, interferon-inducible protein; MCP, monocyte chemoattractant protein; MIP, macrophage-inflammatory protein; NFD, Nonfebrile DENV; OFI, Other febrile illness; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Table 7.

Multivariate Estimates of Immune Response Markers With Illness Category

| Overall | Healthy Control | Nonfebrile DENV | OFI | Apparent DENV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever−/DENV− | Fever−/DENV+ | Fever+/DENV− | Fever+/DENV+ | ||||||

| Exposure Variables | n = 71 | n = 44 | n = 12 | n = 4 | n = 11 | ||||

| Wald χ 2 | P Valuea | OR (95% CI) | P Valueb | OR (95% CI) | P Valueb | OR (95% CI) | P Valueb | ||

| IL-15 (MFI) | 15.66 | .001 | Reference | 0.89 (.80–.99) | .03 | 1.01 (.95–1.08) | .69 | 1.09 (1.03–1.14) | .001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DENV, dengue virus; IL, interleukin; MFI, median fluorescence intensity; OFI, other febrile illness; OR, odds ratio.

a P values obtained using a Wald χ 2 tests for independence.

b P values obtained from polytomous logistic regression, Type 3 analysis of effects. Each illness category compared to “healthy control” as the reference group. Model is adjusted for age, sex, and body mass index.

In a multivariate analysis using polytomous logistic regression to model the outcome illness categories with immune response biomarkers (n = 71), only interleukin (IL)-15 remained in the model. The model was adjusted for covariates of age, sex, and BMI (Table 7). Compared to the reference group of healthy controls, every unit increase of IL-15 resulted in a 9% increase in odds of apparent DENV (CI, 3%–14%; P = .001) and an 11% decrease in odds of nonfebrile DENV (CI, 1%–20%; P = .03).

DISCUSSION

In a nested case-control analysis, we assessed nutritional status and immune response markers among participants grouped in categories of healthy control, nonfebrile DENV infection, OFI, and apparent DENV infection. Concentrations of serum ferritin and TBI differed across categories and were highest in the apparent DENV group. Vitamin A (RBP) and vitamin D (25(OH)D) concentrations also differed significantly across illness groups. As expected, many of the immune response markers, measured in 71 of the 142 participants, were elevated in the apparent DENV group. In multivariate models adjusting for age, sex, and BMI, micronutrient concentrations for ferritin and RBP were significantly associated with increased odds for apparent DENV infection, when compared to the healthy control group. Elevated levels of IL-15 were associated with apparent DENV and appeared to preclude nonfebrile DENV when compared to the healthy control group.

A recent systematic review summarizing research on relationships between micronutrient biomarkers and DENV infection motivated the present study. We applied APR adjustments to offer a more accurate interpretation of the associations between nutrient biomarkers and DENV regardless of infection stage. Another strength of the present study includes access to participants with nonclinical DENV infection, recruited as associates from surrounding households of clinical index cases. Cases of nonfebrile viremic DENV infection are challenging to capture, and this unique recruitment strategy allowed for biomarker comparisons between both DENV infection and febrile illness categories.

Elevated serum ferritin or hyperferritinemia has been described with regard to several Flaviviridae family viral infections including hepatitis C [35], West Nile encephalitis [36], and DENV. Studies have demonstrated that elevated serum ferritin is associated with dengue infection, either relating to increased severity [25] or in comparison to OFI or healthy controls [37–39]. One possible explanation points to macrophage cells. Monocytes and macrophages are among the target cells for DENV infection in vivo, and macrophages play a key role in regulating ferritin storage and secretion [40]. Dengue virus infection and activation of macrophages may increase ferritin production, resulting in hyperferritinemia [38, 39]. Given these associations, researchers have proposed using serum ferritin cutoffs as a clinical diagnostic tool for dengue infection or severity, but none has applied APR adjustments for ferritin concentrations. After APR adjustment, our results demonstrate that serum ferritin concentrations were highest in the apparent DENV group. Therefore, serum ferritin may represent an important clinical marker for dengue severity; however, APR adjustment should be taken into account when determining decisive serum ferritin cutoffs.

There is limited evidence investigating relationships between vitamin A and DENV infection [26]. One study concluded that unadjusted vitamin A retinol and β-carotene concentrations were lower in individuals with acute DENV infection compared to the same individuals 7 days after hospital discharge or healthy controls [41], which is likely explained by the APR. After APR adjustment, RBP concentrations in the present study differed significantly across illness categories and were lower in apparent DENV compared to nonfebrile DENV (pairwise data not shown). With demonstrated roles in innate and adaptive immune function, vitamin A may also provide specific antiviral support at the transcriptional level via regulation of genes expressing viral sensing receptors, type I interferons, and proinflammatory cytokines [42, 43]. Low vitamin A concentration or deficient status may impair the immune response to DENV infection and contribute to more severe illness outcomes. Specifically, reduced vitamin A can interfere with dendritic cell differentiation, T-cell function, and secretion of key cytokines involved in DENV immunity [42, 44, 45]. However, further investigation with estimated vitamin A status before infection would appropriately demonstrate any influence of vitamin A status on DENV infection outcomes. In addition, it is worth noting that the results of vitamin A supplementation in the context of infection have often been mixed [46].

In a subset of 71 included participants, several of the 29 measured cytokine and chemokine marker levels (MFI) differed significantly across illness groups with the highest levels observed in cases of apparent DENV. Although many immune response markers have been described in an effort to distinguish SD and DWWS from DNWS, few studies have focused on markers that distinguish apparent DENV infection from inapparent or subclinical DENV infection. In a study of 85 DENV-infected Cambodian children, markers of IL-6, IL-8, IL-15, macrophage-inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α, MIP-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-α were not significantly different in those with clinical dengue compared with asymptomatic dengue [47]. In a separate study that collected blood samples from Thai children before and during natural DENV infection, baseline peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were stimulated with DENV, and resulting cytokine production was compared with corresponding clinical illness. Interleukin-6, IL-15, and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 were significantly higher from PBMCs of those who developed symptomatic DENV infection compared with asymptomatic DENV infection [48]. The present study showed that compared to the healthy control category, higher levels of IL-15 were associated with apparent DENV, and lower levels were associated with nonfebrile DENV, contributing to existing evidence that IL-15 may be part of a “pathologic” immune profile. Interleukin-15 has been associated with natural killer cell expansion in DENV infection, which is linked to both cytolytic activity and tissue damage [49, 50].

This study has several limitations. The assessment of DENV infection and micronutrient concentrations at a single time point precludes interpretations of temporal associations and causation. We cannot infer to what degree DENV affects circulating nutrients or nutrient deficiencies impact DENV immunity. The burden of apparent dengue illness is typically borne by children younger than 15 years experiencing primary or secondary heterotypic infection; however, given the recruitment study design, the sample may not be representative of the general population. Clinical assessment of dengue severity between DNWS, DWWS, and SD is determined using a combination of clinical signs and biomarkers. With many associate participants recruited from communities, clinical laboratory biomarkers were unavailable for all participants, which prevented further dengue illness classification beyond apparent and nonfebrile. The nutritional analysis also would have been more comprehensive if measures for hemoglobin were available. Without hemoglobin, we were unable to fully examine the burden and etiology of anemia in this population. Furthermore, immune response marker measurements for all included participants (n = 142), constrained by available sample volume, would have allowed for analysis of associations between nutrient biomarkers and the immune response with respect to illness categories.

CONCLUSIONS

This analysis from a cohort in coastal Ecuador provides a comprehensive investigation of the role of nutrition in the context of DENV infection. Our results suggest that the biomarkers serum ferritin, vitamin A (RBP), and IL-15 are associated with apparent DENV, yet not with nonfebrile DENV, and may play a role in the immunopathology of dengue illness. Identifying biomarkers that can help diagnose and/or predict dengue illness severity offers the potential for prevention and treatment options. Future prospective studies ought to measure concentration kinetics of these biomarkers over the course of DENV infection, or at least during acute and convalescent time points, to fully evaluate directional relationships between micronutrients and DENV.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Table 1. Immune response marker levels across illness categories.

Supplementary Table 2. Thurnham correction factors.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We are grateful to the field personnel and the study participants, without whom the study would not have been possible. We also acknowledge the support of Vicky Simon (Human Nutritional Chemistry Service Laboratory, Division of Nutritional Sciences, Cornell University) for conducting micronutrient assays, the results of which are presented in the manuscript.

Financial support. The parent study was funded, in part, by the Department of Defense Global Emerging Infection Surveillance Grant (P0220_13_OT) and the Department of Medicine of SUNY Upstate Medical University; the ancillary analyses were partly funded by the Division of Nutritional Sciences and the Einaudi Center for International Studies at Cornell University along with the Office of the Director, Office of Research on Women’s Health, and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (Grant R01 EB021331) at the National Institutes of Health. AJL acknowledges support by the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number TL1TR001858.

Potential conflicts of interest. S. M. is an unpaid board member for a diagnostic start up focused on measurement of nutritional biomarkers at the point-of-care utilizing the results from his research. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Presented in part: Annual Meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, Philadelphia, PA, 2015.

References

- 1. Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 2013; 496:504–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Castro MC, Wilson ME, Bloom DE. Disease and economic burdens of dengue. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17:e70–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. Dengue: guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pan American Health Organization. Dengue: Guidelines for patient care in the región of the Americas. 2nd ed Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sabin AB. Research on dengue during World War II. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1952; 1:30–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burke DS, Nisalak A, Johnson DE, Scott RM. A prospective study of dengue infections in Bangkok. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1988; 38:172–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Halstead SB. Dengue. Lancet 2007; 370:1644–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fatima K, Syed NI. Dengvaxia controversy: impact on vaccine hesitancy. J Glob Health 2018; 8:010312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization. Meeting of the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) on immunization, April 2018 – conclusions and recommendations: policy recommendations on the use of the first licensed dengue vaccine. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2018; 337–40. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bresnahan KA, Tanumihardjo SA. Undernutrition, the acute phase response to infection, and its effects on micronutrient status indicators. Adv Nutr 2014; 5:702–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thurnham DI, McCabe GP, Northrop-Clewes CA, Nestel P. Effects of subclinical infection on plasma retinol concentrations and assessment of prevalence of vitamin A deficiency: meta-analysis. Lancet 2003; 362:2052–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thurnham DI, McCabe LD, Haldar S, Wieringa FT, Northrop-Clewes CA, McCabe GP. Adjusting plasma ferritin concentrations to remove the effects of subclinical inflammation in the assessment of iron deficiency: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2010; 92:546–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cherayil BJ. Iron and immunity: immunological consequences of iron deficiency and overload. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2010; 58:407–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ekiz C, Agaoglu L, Karakas Z, Gurel N, Yalcin I. The effect of iron deficiency anemia on the function of the immune system. Hematol J 2005; 5:579–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ross AC, Stephensen CB. Vitamin A and retinoids in antiviral responses. FASEB J 1996; 10:979–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Katona P, Katona-Apte J. The interaction between nutrition and infection. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46:1582–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Villamor E, Fawzi WW. Effects of vitamin a supplementation on immune responses and correlation with clinical outcomes. Clin Microbiol Rev 2005; 18:446–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abu-Amer Y, Bar-Shavit Z. Impaired bone marrow-derived macrophage differentiation in vitamin D deficiency. Cell Immunol 1993; 151:356–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kankova M, Luini W, Pedrazzoni M, et al. Impairment of cytokine production in mice fed a vitamin D3-deficient diet. Immunology 1991; 73:466–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yang S, Smith C, Prahl JM, Luo X, DeLuca HF. Vitamin D deficiency suppresses cell-mediated immunity in vivo. Arch Biochem Biophys 1993; 303:98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dhur A, Galan P, Hercberg S. Folate status and the immune system. Prog Food Nutr Sci 1991; 15:43–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tamura J, Kubota K, Murakami H, et al. Immunomodulation by vitamin B12: augmentation of CD8+ T lymphocytes and natural killer (NK) cell activity in vitamin B12-deficient patients by methyl-B12 treatment. Clin Exp Immunol 1999; 116:28–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Trang NTH, Long NP, Hue TTM, et al. Association between nutritional status and dengue infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2016; 16:172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Widagdo. Blood zinc levels and clinical severity of dengue hemorrhagic fever in children. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2008; 39:610–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chaiyaratana W, Chuansumrit A, Atamasirikul K, Tangnararatchakit K. Serum ferritin levels in children with dengue infection. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2008; 39:832–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ahmed S, Finkelstein JL, Stewart AM, et al. Micronutrients and dengue. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2014; 91:1049–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rothman AL. Immunity to dengue virus: a tale of original antigenic sin and tropical cytokine storms. Nat Rev Immunol 2011; 11:532–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Srikiatkhachorn A, Mathew A, Rothman AL. Immune-mediated cytokine storm and its role in severe dengue. Semin Immunopathol 2017; 39:563–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kenneson A, Beltrán-Ayala E, Borbor-Cordova MJ, et al. Social-ecological factors and preventive actions decrease the risk of dengue infection at the household-level: results from a prospective dengue surveillance study in Machala, Ecuador. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017; 11:e0006150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stewart-Ibarra AM, Ryan SJ, Kenneson A, et al. The Burden of dengue fever and chikungunya in Southern Coastal Ecuador: epidemiology, clinical presentation, and phylogenetics from the first two years of a prospective study. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2018; 98:1444–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. World Health Organization. 2018 Global reference list of 100 core health indicators (plus health-related SDGs). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cook JD, Flowers CH, Skikne BS. The quantitative assessment of body iron. Blood 2003; 101:3359–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Breen EJ, Tan W, Khan A. The statistical value of raw fluorescence signal in Luminex xMAP based multiplex immunoassays. Sci Rep 2016; 6:26996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL.. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd ed Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ackerman Z, Pappo O, Ben-Dov IZ. The prognostic value of changes in serum ferritin levels during therapy for hepatitis C virus infection. J Med Virol 2011; 83:1262–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cunha BA, Sachdev B, Canario D. Serum ferritin levels in West Nile encephalitis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2004; 10:184–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Roy Chaudhuri S, Bhattacharya S, Chakraborty M, Bhattacharjee K. Serum ferritin: a backstage weapon in diagnosis of dengue fever. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis 2017; 2017:7463489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Soundravally R, Agieshkumar B, Daisy M, Sherin J, Cleetus CC. Ferritin levels predict severe dengue. Infection 2015; 43:13–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. van de Weg CA, Huits RM, Pannuti CS, et al. Hyperferritinaemia in dengue virus infected patients is associated with immune activation and coagulation disturbances. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014; 8:e3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. La A, Nguyen T, Tran K, et al. Mobilization of iron from ferritin: new steps and details. Metallomics 2018; 10:154–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Klassen P, Biesalski HK, Mazariegos M, Solomons NW, Fürst P. Classic dengue fever affects levels of circulating antioxidants. Nutrition 2004; 20:542–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hall JA, Cannons JL, Grainger JR, et al. Essential role for retinoic acid in the promotion of CD4(+) T cell effector responses via retinoic acid receptor alpha. Immunity 2011; 34:435–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Loo YM, Gale M Jr. Immune signaling by RIG-I-like receptors. Immunity 2011; 34:680–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pino-Lagos K, Guo Y, Brown C, et al. A retinoic acid-dependent checkpoint in the development of CD4+ T cell-mediated immunity. J Exp Med 2011; 208:1767–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Beijer MR, Kraal G, den Haan JM. Vitamin A and dendritic cell differentiation. Immunology 2014; 142:39–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fawzi WW, Msamanga GI, Spiegelman D, et al. A randomized trial of multivitamin supplements and HIV disease progression and mortality. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Simon-Loriere E, Duong V, Tawfik A, et al. Increased adaptive immune responses and proper feedback regulation protect against clinical dengue. Sci Transl Medi 2017; 9:eaal5088. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aal5088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Friberg H, Beaumier CM, Park S, et al. Protective versus pathologic pre-exposure cytokine profiles in dengue virus infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018; 12:e0006975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Azeredo EL, De Oliveira-Pinto LM, Zagne SM, Cerqueira DI, Nogueira RM, Kubelka CF. NK cells, displaying early activation, cytotoxicity and adhesion molecules, are associated with mild dengue disease. Clin Exp Immunol 2006; 143:345–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sung JM, Lee CK, Wu-Hsieh BA. Intrahepatic infiltrating NK and CD8 T cells cause liver cell death in different phases of dengue virus infection. PLoS One 2012; 7:e46292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.