Abstract

Objective:

To assess the incidence, severity, and outcomes of pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome (PARDS) following trauma using Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference criteria

Design:

Retrospective cohort study

Setting:

Level 1 pediatric trauma center

Patients:

Trauma patients ≤17 years admitted to the intensive care unit from 2009-2017

Interventions:

None

Measurements and Main Results:

We queried electronic health records to identify patients meeting PARDS oxygenation criteria for ≥6 hours and determined whether patients met complete PARDS criteria via chart review. We estimated associations between PARDS and outcome using generalized linear Poisson regression adjusted for age, injury mechanism, Injury Severity Score, and serious brain and chest injuries. Of 2470 critically injured children, 103 (4.2%) met PARDS criteria. Mortality was 34.0% among PARDS patients versus 1.7% among non-PARDS patients (adjusted RR 3.7, 95% CI 2.0-6.9). Mortality was 50.0% for severe PARDS at onset, 33.3% for moderate, and 30.5% for mild. Cause of death was neurologic in 60.0% and multi-organ failure in 34.3% of PARDS non-survivors versus neurologic in 85.4% of non-survivors without PARDS (p=0.001). Among survivors, 77.1% of PARDS patients had functional disability at discharge versus 30.7% of non-PARDS patients (p<0.001), and only 17.5% of PARDS patients discharged home without ongoing care versus 86.4% of non-PARDS patients (aRR 1.5, 1.1-2.1).

Conclusions:

Incidence and mortality associated with PARDS following traumatic injury are substantially higher than previously recognized, and PARDS development is associated with high risk of poor outcome even after adjustment for underlying injury type and severity.

Keywords: Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Child, Intensive Care Units, Hospital Mortality, Outcome Assessment, Trauma Centers

Introduction

Traumatic injury is a known but understudied trigger for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in children. Data from the National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB) demonstrate that ARDS is the most common medical complication in children who die ≥24 hours post-injury.1 Approximately 1.8% of children included in the NTDB admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) following trauma develop ARDS.2 Those with ARDS experience a significantly higher risk of morbidity and mortality than children with comparable injury type and severity without ARDS.3

Although these data offer important insights into the impact of ARDS on outcomes after pediatric trauma, there are limitations to using the NTDB to study ARDS in children. ARDS is recorded in the NTDB for patients meeting American-European Consensus Conference criteria4 and subsequently Berlin criteria.5 Adult definitions likely underestimate ARDS occurrence in children6,7 and may identify a more severely ill subset of patients than those identified by pediatric criteria.8,9 Additionally, the accuracy of ARDS diagnoses recorded by NTDB registrars cannot be verified.

We thus aimed to apply Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference (PALICC) criteria10 (SDC 1) in a cohort of critically injured children to determine the incidence, timing of onset, and severity of pediatric ARDS (PARDS) after trauma and evaluate the risk of morbidity and mortality associated with PARDS development. Better understanding of the epidemiology of PARDS after traumatic injury may facilitate development of improved PARDS recognition, treatment, and prevention strategies to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with the medical sequelae of severe pediatric trauma.

Materials and Methods

Study participants:

We included children ≤17 years admitted with traumatic injury to the Harborview Medical Center (HMC) PICU or transferred to the Seattle Children’s Hospital (SCH) PICU from 2009-2017.

Settings:

HMC in Seattle, Washington is the only Level I pediatric trauma center for five states. Pediatric trauma patients at HMC who may require high-frequency oscillatory ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation are transferred to SCH, a stand-alone academic children’s hospital. Both the HMC and SCH PICUs are staffed by University of Washington (UW) Pediatric Critical Care Medicine faculty and fellows.

Identification of PARDS:

We used the HMC trauma registry to identify all pediatric trauma patients admitted to the HMC PICU or transferred from HMC to the SCH PICU. We performed electronic health record queries at both sites to extract all SpO2, PaO2, FiO2, and mean airway pressure (MAP) variables recorded within 7 days after injury. For mechanically ventilated patients, we calculated the oxygenation saturation index (OSI) for every recorded SpO2 ≤97% and the oxygenation index (OI) for every recorded PaO2, using the most recent FiO2 and MAP. For patients receiving full-face non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) with expiratory positive airway pressure ≥5, we calculated SpO2:FiO2 and PaO2:FiO2 ratios. We considered patients to have met PALICC oxygenation criteria for PARDS6 if they had ≥3 qualifying oxygenation indices sustained for ≥6 hours.

We performed chart reviews for patients meeting oxygenation criteria to determine whether they met complete PALICC criteria for PARDS. We evaluated for a new parenchymal infiltrate on chest radiograph based on agreement between the attending radiologist read and review by a pediatric intensivist (EYK). We reviewed documentation by the attending pediatric intensivist to determine whether respiratory failure was attributable primarily to cardiac failure or fluid overload. We reviewed documented medical history to evaluate for comorbidities requiring special consideration of oxygenation metrics. Patients meeting all PALICC criteria were determined to have PARDS.

PARDS severity:

Patients were categorized as having mild (4≤OI<8; 5≤OSI<7.5), moderate (8≤OI<16; 7.5≤OSI<12.3), or severe (OI ≥16; OSI ≥12.3) PARDS at the time of PARDS onset and serially from 6-48 hours after onset. Categorization was based on the most representative OI and OSI values closest to each time point. Per PALICC criteria, if both OI and OSI values were available severity was determined based on OI, and patients receiving NIPPV were not categorized by severity.

Outcomes:

We assessed in-hospital mortality for patients with and without PARDS by PARDS severity at onset, six hours after onset, and peak severity within 48 hours of onset. We evaluated the cause of death (hypoxemia, cardiac arrest, neurologic, multi-organ failure) and mode of death (cardiopulmonary resuscitation [CPR], therapy withdrawal/limitation, neurologic criteria) by chart review of all inpatient deaths. Among survivors to discharge, we assessed duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU and hospital length of stay (LOS), Functional Independence Measure (FIM),11 and discharge disposition. FIM was assessed by bedside nurses at hospital discharge for patients ≥7 years,12–14 with three domains of feeding, expression, and locomotion each scored from 1 (most impaired) to 4 (normal function). Post-discharge care included inpatient rehabilitation, skilled nursing facilities, other acute care, inpatient psychiatric care, and home healthcare services.

Statistical Analysis:

We determined PARDS incidence, timing of onset, and PARDS severity at onset and serially up to 48 hours after onset. We compared patient and injury characteristics of patients with and without PARDS using chi-squared, Wilcoxon rank-sum, and two-sample t-tests. We estimated the risk of mortality for patients with PARDS and by severity category using generalized linear Poisson regression. Among survivors, we estimated the association between PARDS and duration of ventilation and LOS using linear regression, and the risk of requiring post-discharge care using generalized linear Poisson regression. We adjusted each regression model for age, injury mechanism, Injury Severity Score (ISS), presence of a traumatic brain injury (TBI) with an Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) severity score ≥3, and presence of a chest injury with AIS≥3. We compared cause and mode of death and FIM scores of patients with and without PARDS using chi-squared tests and two-sample t-tests. We conducted all analyses using Stata/SE 14.2 statistical software.

The study was approved by the UW and SCH Institutional Review Boards.

Results

Population characteristics:

Of 2,470 pediatric trauma admissions to the HMC and SCH PICUs during the study period, 4.2% (n=103) met complete PARDS criteria within 7 days post-injury. Patients with PARDS were older than patients without PARDS (10.8 versus 9.0 years, p=0.003) (Table 1). The mechanism of injury differed significantly between groups (p<0.001); motor vehicle crashes were the most common mechanism among patients with PARDS, whereas falls were the most common among patients without PARDS. Strangulation injuries were much more common among patients with PARDS. The median ISS among PARDS patients was 30 (IQR 24-50) compared to a median ISS of 14 (IQR 9-21) among non-PARDS patients (p<0.001). Patients with PARDS were more likely to have sustained serious TBIs (71.8% versus 47.6%, p<0.001) and chest injuries (53.4% versus 15.5%, p<0.001) than patients without PARDS.

Table 1:

Characteristics of pediatric intensive care unit patients with and without PARDS

| Patient or Injury Characteristic | Patients with PARDS No. (%) (n=103, 4.2%) | Patients without PARDS No. (%) (n=2367, 95.8%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 73 (70.9) | 1573 (66.5) | 0.35 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 10.8 (5.8) | 9.0 (5.9) | 0.003 |

| <1 | 3 (2.9) | 173 (7.3) | |

| 1 – 4 | 20 (19.4) | 601 (25.4) | |

| 5 – 12 | 26 (25.2) | 680 (28.7) | |

| 13 – 17 | 54 (52.4) | 913 (38.6) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 58 (56.3) | 1445 (61.1) | 0.62 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 9 (8.7) | 186 (7.9) | |

| Hispanic | 17 (16.5) | 378 (16.0) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 10 (9.7) | 178 (7.5) | |

| Native American/Alaska Native | 6 (5.8) | 77 (3.3) | |

| Other/Unknown/Multiracial | 3 (2.9) | 103 (4.4) | |

| Mechanism of injury | <0.001 | ||

| Motor vehicle crash | 47 (45.6) | 557 (23.5) | |

| Pedestrian/cyclist | 16 (15.5) | 366 (15.5) | |

| Strangulation | 13 (12.6) | 11 (0.5) | |

| Fall | 8 (7.8) | 853 (36.0) | |

| Struck by/against | 9 (8.7) | 312 (13.2) | |

| Firearm | 7 (6.8) | 95 (4.0) | |

| Other | 3 (2.9) | 173 (7.3) | |

| Injury Severity Score, median (IQR) | 30 (24-50) | 14 (9-21) | <0.001 |

| 1 – 8 | 3 (2.9) | 501 (21.3) | |

| 9 – 15 | 5 (4.9) | 767 (32.5) | |

| 16 – 24 | 19 (18.5) | 579 (24.6) | |

| 25 – 39 | 40 (38.8) | 427 (18.1) | |

| 40 – 75 | 36 (35.0) | 84 (3.6) | |

| Traumatic brain injury with AIS ≥3 | 74 (71.8) | 1126 (47.6) | <0.001 |

| Chest injury with AIS ≥3 | 55 (53.4) | 366 (15.5) | <0.001 |

PARDS, pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; AIS, Abbreviated Injury Scale severity score

PARDS course:

The median time to PARDS onset was 1.3 days post-injury (IQR 0.8-2.6). The initial trauma was the only identified clinical insult triggering PARDS in 90.3% of cases, while 6 patients also developed pneumonia and 4 patients experienced an aspiration event prior to the onset of PARDS.

At the time of PARDS onset, 55% of patients had mild PARDS, 29% moderate, and 14% severe, and two patients were non-invasively ventilated and severity was not assigned (Figure 1). By 48 hours after onset, 42% of the patients with mild PARDS or who were non-invasively ventilated at onset had resolved while 17% died and 41% continued to meet PARDS criteria (31% mild, including 1 NIPPV; 5% moderate; 5% severe). Of patients with moderate PARDS at onset, 27% resolved by 48 hours, 23% died, and 50% continued to have PARDS (33% mild; 10% moderate; 7% severe). Of those with severe PARDS at onset, only 7% had resolved by 48 hours while 29% died and 64% continued to have PARDS (43% mild; 21% moderate). There were no patients with severe PARDS at onset who had persistent severe PARDS at 48 hours.

Figure 1: Progression of PARDS severity in the first 48 hours after onset, stratified by severity category at onset.

Patients meeting PARDS criteria while on non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) are combined with patients with mild PARDS (n=2 at PARDS onset; n=3 after extubation from mild or moderate PARDS).

Patient outcomes:

Mortality was 34.0% among PARDS patients (Table 2). An additional 48.5% required ongoing post-discharge care and only 17.5% discharged home without in-home services. In contrast, mortality among patients without PARDS was only 1.7%, with 11.8% requiring ongoing post-discharge care and 86.4% discharging home without services. Mortality was highest among patients for whom the initial trauma was the only identified clinical insult triggering PARDS (36.6%) compared to patients who also experienced pneumonia (16.7%) or aspiration (0%) prior to PARDS onset. After adjusting for patient age, injury mechanism, injury severity, and serious TBI or chest injuries, the relative risk of death associated with PARDS was 3.7 (95% CI 2.0-6.9). The aRR associated with PARDS of requiring ongoing post-discharge care relative to discharging home was 1.5 (95% CI 1.1-2.1).

Table 2:

Cause, mode, and timing of death of patients with and without pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome

| Variable | Patients with PARDS | Patients without PARDS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality No. (%) | Days to death median (IQR) | Mortality No. (%) | Days to death median (IQR) | |

| All-cause mortality | 35 (34.0) | 1.9 (1.1-4.0) | 41 (1.7) | 1.6 (0.5-2.5) |

| Cause of death | ||||

| Neurologic | 21 (60.0) | 2.6 (1.2-8.9) | 35 (85.4) | 1.6 (0.6-2.6) |

| Multisystem organ failure | 12 (34.3) | 1.9 (1.6-2.9) | 2 (4.9) | 78.8 (2.5-155.0) |

| Refractory hypoxemia | 1 (2.9) | 0.4 | 0 | - |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 (2.9) | 0.3 | 4 (9.8) | 0.2 (0.2-0.3) |

| Mode of death | ||||

| Death by neurologic criteria | 18 (51.4) | 1.9 (1.2-2.6) | 20 (48.8) | 1.5 (0.8-2.0) |

| Therapy withdrawal/limitation | 17 (48.6) | 3.9 (1.1-10.8) | 17 (41.5) | 2.6 (1.0-6.1) |

| Unsuccessful CPR | 0 | - | 4 (9.8) | 0.2 (0.2-0.3) |

PARDS, pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome; IQR, interquartile range; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Mortality by severity:

In-hospital mortality increased with higher PARDS severity when evaluated either at PARDS onset, six hours after onset, or by the peak severity within 48 hours of onset (Figure 2). Mortality was highest among patients with severe PARDS at onset (50.0%). Severity six hours after PARDS onset had better discrimination for risk for mortality than either severity at onset or peak 48-hour severity. Relative to patients who did not develop PARDS, the adjusted risk of mortality by severity six hours after PARDS onset was 2.7 for mild PARDS/NIPPV (95% CI 1.4-5.3), 4.7 for moderate PARDS (95% CI 2.0-11.0), and 5.4 for severe PARDS (95% CI 2.4-12.2).

Figure 2: Mortality by PARDS severity at onset, 6 hours after onset, and peak severity within the first 48 hours after PARDS onset.

Patients meeting PARDS criteria while on non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) are combined with those who met criteria for mild PARDS.

Timing and cause of death:

Time to death was longer among patients with PARDS after a median of 1.9 days (IQR 1.1-4.0) of hospitalization compared with 1.6 days (IQR 0.5-2.5) among patients without PARDS. Death occurred at a median of 1.1 days (IQR 0.5-3.2) after PARDS onset, ranging from 0.9 days (IQR 0.5-3.2) for severe PARDS to 1.1 days (IQR 0.5-7.8) for mild PARDS.

The primary cause of death was attributable to neurologic failure for 60.0% of PARDS non-survivors and 85.4% of non-survivors without PARDS (Table 2). Of patients who died of neurologic failure, 20% of those with PARDS had non-traumatic brain injury compared to 3% of those without PARDS. Multi-organ failure was the second most common cause of death among patients with PARDS (34.3%), but uncommon among patients without PARDS (4.9%). Only one patient with PARDS died of refractory hypoxemia.

Time from admission to death was longer for PARDS patients who died of neurologic failure (median 2.6 days, IQR 1.2-8.9) than multi-organ failure (median 1.9 days, IQR 1.6-2.9). Approximately half of non-survivors in both groups were declared deceased by neurologic criteria; the remainder of PARDS non-survivors had withdrawal/limitation of therapy whereas 9.8% of non-survivors without PARDS died after unsuccessful CPR and 41.5% died after withdrawal/limitation of therapy. Time to death was longer among PARDS patients than non-PARDS patients for either death by neurologic criteria or therapy withdrawal/limitation.

Outcomes among survivors:

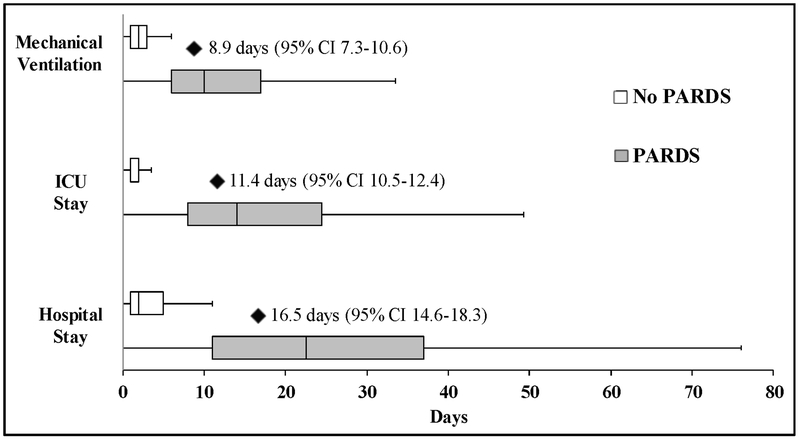

Patients with PARDS who survived to hospital discharge experienced significantly longer duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU LOS, and hospital LOS than patients without PARDS (Figure 3). After adjustment, PARDS was associated with an estimated additional 8.9 days of mechanical ventilation (95% CI 7.3-10.6), 11.4 ICU days (95% CI 10.5-12.4), and 16.5 total hospital days (95% CI 14.6-18.3).

Figure 3: Duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU length of stay, and hospital length of stay among patients with and without PARDS who survived to hospital discharge.

Box-plots demonstrate median and interquartile range, with whiskers representing upper and lower adjacent values (1.5x the interquartile range). Black diamonds represent the mean number of additional days for PARDS patients compared to non-PARDS patients after adjustment for confounders, with the 95% confidence interval represented in parentheses.

Only 22.9% of PARDS survivors ≥7 years had normal function (FIM 12/12) at hospital discharge compared with 69.3% of survivors without PARDS (p<0.001). The mean FIM score at discharge was 7.8/12 (SD 3.3) among patients with PARDS and 11.2/12 (SD 1.6) among patients without PARDS (p<0.001). PARDS patients more commonly experienced disability across all three domains of locomotion (75% of PARDS patients versus 29% of non-PARDS patients, p<0.001), feeding (61% versus 6%, p<0.001), and expression (37% versus 4%, p<0.001).

Discussion

In this large 9-year cohort study of nearly 2,500 critically injured children, we found that the incidence of post-traumatic ARDS using a pediatric-specific definition was much higher than previously recognized from administrative data, with higher associated in-hospital mortality. The only previous studies of ARDS following traumatic injury in children utilized the NTDB and relied on ARDS being documented by NTDB registrars at each participating site based on Berlin and AECC criteria;3,15 ARDS incidence was 1.8% among children admitted to an ICU with 20% mortality by those criteria.3 Using primary data collection and applying PALICC criteria to our local cohort, we found a PARDS incidence of 4.2% with 34% in-hospital mortality.

Although the higher incidence in this population compared to the NTDB cohort is consistent with prior findings in all-cause pediatric ARDS that PALICC criteria identify more children with ARDS than Berlin or AECC criteria,7–9 these other studies found that mortality was lower among cohorts identified by PALICC criteria. The considerably higher ARDS mortality in our population over a similar date range to the NTDB study does not appear to be due to greater injury severity at our institution; the median ISS of the two cohorts was equivalent and non-ARDS mortality was actually higher in the NTDB cohort at 4.3%3 compared with 1.7% in the HMC cohort. It is possible that we were more likely than NTDB registrars to identify severely ill patients who met PARDS criteria but died quickly; the median time to death among PARDS patients in our cohort was only two days versus three days in the NTDB.3

Our findings also suggest that PARDS development occurs with similar or even higher frequency among critically injured children relative to general PICU populations; the international PARDIE study found an all-cause PARDS incidence of 3.2%.7 The 34% PARDS mortality in our cohort is also considerably higher than the overall PARDS mortality rate found in many recent investigations16–22 including PARDIE with 17% in-hospital mortality.7 High injury severity and a high prevalence of serious TBI likely contribute greatly to mortality in this population and are reflected in the short median time to death. Nevertheless, the risk of mortality among patients with PARDS remained nearly four times greater than patients without PARDS even after adjustment for age, injury mechanism, ISS, and the presence of serious head and chest injuries.

With a very low frequency of persistent hypoxemia as a cause of death, it is difficult to isolate the contribution of lung disease to outcomes after trauma. This is not unique to the trauma population; previous studies of both pediatric21 and adult23,24 all-cause ARDS have found that neurologic failure is a more common cause of death than hypoxemia. In our cohort, PARDS patients were much more likely to die of multi-organ failure and non-traumatic brain injury than patients without PARDS, suggesting that hypoxemia due to PARDS could have been a contributing factor to end-organ injury. Given that median PARDS onset was only 1.3 days after injury, it is difficult to ascertain the extent of anoxic organ injury that occurred before or after PARDS onset. The finding that the risk of mortality was strongly associated with severity of hypoxemia, however, does support the concept that PARDS may influence outcomes beyond underlying injury severity.

This study also confirms prior findings that post-traumatic PARDS in children is associated with substantial morbidity among survivors.3 Significantly longer duration of mechanical ventilation and LOS among PARDS patients likely contributed to over three-quarters of PARDS survivors experiencing functional disability at discharge compared with one-third of survivors without PARDS, and only 17.5% of PARDS patients being able to discharge home without ongoing healthcare services compared with 86.4% of patients without PARDS. The impact of PARDS on development of new morbidity and need for post-discharge care has been demonstrated in general PICU populations as well,25 and there is increasing awareness of the importance of assessing morbidity in addition to mortality following PARDS.21,26,27

There were several limitations to this study. Our cohort only represents a single trauma system, and thus our findings may not be generalizable to other settings. As the incidence of PARDS was calculated from a cohort of all pediatric trauma patients admitted to the HMC and SCH PICUs, different PICU admission criteria at different institutions may result in incidence rates that are not directly comparable. Per PALICC criteria, we only calculated an OSI for recorded SpO2 values ≤97%; we may have missed patients by not capturing events when SpO2 was 98-100% and FiO2 was not titrated to achieve an SpO2 ≤97%. We attempted to adjust for important potential confounding factors, but there are likely unmeasured confounders that may have inflated the associations between PARDS development and patient outcome and we cannot establish a causative link between PARDS and outcome. Finally, we were only able to assess immediate hospital disposition, and thus the need for post-discharge care may not be an adequate surrogate for ongoing morbidity.

Conclusions

Application of PALICC criteria to a critically injured pediatric trauma population reveals substantially higher post-traumatic ARDS incidence and mortality than previously recognized using administrative data. Development of PARDS after traumatic injury is associated with high risk of both mortality and morbidity. Mortality associated with post-traumatic PARDS is due to neurologic and multi-organ failure rather than hypoxemia, suggesting that interventions to improve outcomes in this population must be focused on multisystem support rather than solely on lung protection and recovery.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1: Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference criteria for pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Supported by NICHD grant 5 T32 HD057822-08

Footnotes

Work performed at: Harborview Injury Prevention and Research Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose

Copyright form disclosure: Drs. Killien and Rivara’s institutions received funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Drs. Killien, Vavilala, and Rivara received support for article research from the NIH. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.McLaughlin C, Zagory JA, Fenlon M, et al. Timing of mortality in pediatric trauma patients: A National Trauma Data Bank analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53(2):344–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Killien EY, Mills B, Watson RS, et al. Risk Factors on Hospital Arrival for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Following Pediatric Trauma. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(12):e1088–e1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Killien EY, Mills B, Watson RS, et al. Morbidity and Mortality Among Critically Injured Children With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(2):e112–e119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, et al. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149(3 Pt 1):818–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. Jama. 2012;307(23):2526–2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khemani RG, Smith LS, Zimmerman JJ, et al. Pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome: definition, incidence, and epidemiology: proceedings from the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16(5 Suppl 1):S23–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khemani RG, Smith L, Lopez-Fernandez YM, et al. Paediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome incidence and epidemiology (PARDIE): an international, observational study. The Lancet Respiratory medicine. 2019;7(2):115–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta S, Sankar J, Lodha R, et al. Comparison of Prevalence and Outcomes of Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Using Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference Criteria and Berlin Definition. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parvathaneni K, Belani S, Leung D, et al. Evaluating the Performance of the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference Definition of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18(1):17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference G. Pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome: consensus recommendations from the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16(5):428–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stineman MG, Shea JA, Jette A, et al. The Functional Independence Measure: tests of scaling assumptions, structure, and reliability across 20 diverse impairment categories. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77(11):1101–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aitken ME, Jaffe KM, DiScala C, et al. Functional outcome in children with multiple trauma without significant head injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(8):889–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winthrop AL, Brasel KJ, Stahovic L, et al. Quality of life and functional outcome after pediatric trauma. J Trauma. 2005;58(3):468–473; discussion 473–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoell SL, Weaver AA, Talton JW, et al. Functional outcomes of motor vehicle crash thoracic injuries in pediatric and adult occupants. Traffic injury prevention. 2018;19(3):280–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Roulet A, Burke RV, Lim J, et al. Pediatric trauma-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes. J Pediatr Surg. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flori HR, Glidden DV, Rutherford GW, et al. Pediatric acute lung injury: prospective evaluation of risk factors associated with mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):995–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kneyber MC, Brouwers AG, Caris JA, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: is it underrecognized in the pediatric intensive care unit? Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(4):751–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmerman JJ, Akhtar SR, Caldwell E, et al. Incidence and outcomes of pediatric acute lung injury. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Luca D, Piastra M, Chidini G, et al. The use of the Berlin definition for acute respiratory distress syndrome during infancy and early childhood: multicenter evaluation and expert consensus. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(12):2083–2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yehya N, Servaes S, Thomas NJ. Characterizing degree of lung injury in pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(5):937–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dowell JC, Parvathaneni K, Thomas NJ, et al. Epidemiology of Cause of Death in Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(11):1811–1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schouten LRA, Veltkamp F, Bos AP, et al. Incidence and Mortality of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Children. Critical Care Medicine. 2015:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stapleton RD, Wang BM, Hudson LD, et al. Causes and timing of death in patients with ARDS. Chest. 2005;128(2):525–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Villar J, Martinez D, Mosteiro F, et al. Is Overall Mortality the Right Composite Endpoint in Clinical Trials of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome? Crit Care Med. 2018;46(6):892–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keim G, Watson RS, Thomas NJ, et al. New Morbidity and Discharge Disposition of Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Survivors. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(11):1731–1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yehya N, Thomas NJ. Relevant Outcomes in Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Studies. Front Pediatr. 2016;4:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quasney MW, Lopez-Fernandez YM, Santschi M, et al. The outcomes of children with pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome: proceedings from the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16(5 Suppl 1):S118–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1: Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference criteria for pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome.