Abstract

Recently, carbon dioxide capture and conversion, along with hydrogen from renewable resources, provide an alternative approach to synthesis of useful fuels and chemicals. People are increasingly interested in developing innovative carbon dioxide hydrogenation catalysts, and the pace of progress in this area is accelerating. Accordingly, this perspective presents current state of the art and outlook in synthesis of light olefins, dimethyl ether, liquid fuels, and alcohols through two leading hydrogenation mechanisms: methanol reaction and Fischer-Tropsch based carbon dioxide hydrogenation. The future research directions for developing new heterogeneous catalysts with transformational technologies, including 3D printing and artificial intelligence, are provided.

Subject terms: Catalytic mechanisms, Heterogeneous catalysis, Chemical engineering

Carbon dioxide (CO2) capture and conversion provide an alternative approach to synthesis of useful fuels and chemicals. Here, Ye et al. give a comprehensive perspective on the current state of the art and outlook of CO2 catalytic hydrogenation to the synthesis of light olefins, dimethyl ether, liquid fuels, and alcohols.

Introduction

Capturing carbon dioxide (CO2) has emerged as an important method of mitigating its impact on environment1–5. However, this introduces the challenge of utilizing a large volume of captured CO2, which previously has not had any industrially viable uses at such a large scale. Realizing that, historically, fossil resources were produced via natural carbon-hydrogenation during photosynthesis, synthetic CO2 hydrogenation is likely the best way to regenerate combusted hydrocarbons.

While CO2 hydrogenation is challenging due to the thermal stability of CO2, making reaction conversions low, considerable progress has been made towards converting CO2 to single carbon (C1) products (e.g., formic acid, carbon monoxide (CO), methane, and methanol) through direct hydrogen reduction or hydrothermal-chemical reduction in water6–11. Thermocatalytic hydrogenation of CO2 to methane can be achieved easily at atmospheric pressure and high gas hourly space velocity (GHSV), and has been shown to achieve CO2 conversion and CH4 selectivity close to theoretical equilibrium values12. Hydrogenation to CO can be performed via the reverse water gas shift (RWGS) reaction. CO2-to-methanol (CTM) (CH3OH and MeOH) has already been industrialized in Reykjavik, Iceland using heterogeneous catalysis and geothermal energy13.

In addition, catalysis for CO2 hydrogenation to C1 products has been widely studied with considerable progress14. Recently, significant progress has been achieved in heterogeneous catalytic hydrogenation of CO2 to various high-value and easily marketable fuels and chemicals containing two or more carbons (C2+ species), including dimethyl ether (DME)15, olefins16, liquid fuels17, and higher alcohols18. Compared to C1 products, C2+ product synthesis is more challenging due to the extreme inertness of CO2 and the high C–C coupling barrier, as well as many competing reactions leading to the formation of C1 products. However, C2+ hydrocarbons and oxygenates possess higher economic values and energy densities than C1 compounds. Therefore, this perspective mainly focuses on heterogeneous catalysis for CO2 hydrogenation to high-value C2+ products.

Many reviews of heterogeneous catalytic hydrogenation of CO2 have been published, organized according to using several approaches, including thermal, electrochemical, and photochemical hydrogenation19; homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts20; and by their respective product distributions or catalysts employed14,21–24. Some are limited to C1 products (e.g., methane or methanol)14,25. However, perspectives on heterogeneous catalytic CO2 hydrogenation to C2+ products are needed to guide scientists working in this area. Thus, this work is designed to help fill this gap and is organized to emphasize reaction mechanisms for producing C2+ materials.

The hydrogenation of CO2 to C2+ products mainly occurs via a methanol-mediated route or a CO2 modified Fischer–Tropsch mechanism17,26. There are a variety of questions that need to be answered for each of these reaction mechanisms: what kinds of catalysts are beneficial for each route? How do the catalysts regulate product selectivity? What can be done to further enhance catalytic performance? What is the central challenge with catalysts for CO2 hydrogenation to C2+ products? To answer these questions, the catalysts for CO2 hydrogenation to C2+ species will be discussed based on the methanol-mediated route and the CO2 modified Fischer–Tropsch route. Some experimental guidelines are provided to improve CO2 conversion and to reduce C1 byproducts. In addition, an outlook of transformational technologies for developing new catalysts is given in this work. Artificial intelligence (AI) is expected to guide the design and discovery of catalysis27,28, while 3D printing technologies are anticipated to be used to manufacture them on a large scale29.

Methanol reaction based CO2 hydrogenation

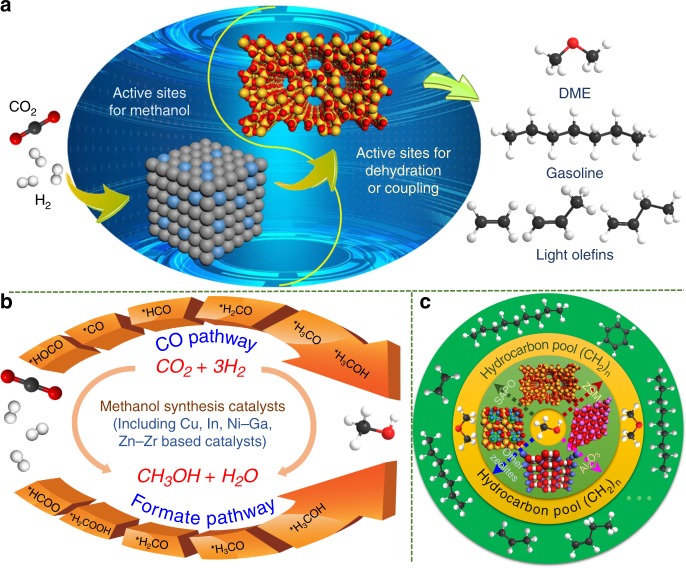

Methanol (CH3OH) reaction based CO2 hydrogenation can be realized by coupling two sequential reactions over a bifunctional catalyst. First, CO2 and H2 are converted to CH3OH over a partially reduced oxide surface (e.g., Cu, In, and Zn) or noble metals via a CO or formate pathway. Then, methanol is dehydrated or coupled over zeolites or alumina. Accordingly, bifunctional or hybrid catalysts are composed of a CH3OH synthesis catalyst and a CH3OH dehydration/coupling catalyst, which can convert CO2 into high-value C2+ compounds, including DME, hydrocarbons like gasoline, and light olefins. An efficient catalyst for these high-value C2+ products should be active for both CH3OH synthesis and dehydration/coupling under the same conditions (Fig. 1a, R1–R4).

| R1 |

| R2 |

| R3 |

| R4 |

Fig. 1. CO2 hydrogenation to fuels and chemicals via the methanol reaction mechanism.

a Schematic for the reaction mechanism of direct CO2 hydrogenation to C2+ products over bifunctional catalysts. b Two possible reaction pathways for methanol synthesis. c Schematic for methanol conversion into hydrocarbons inside zeolites via the hydrocarbon-pool mechanism.

In CO2 hydrogenation to C2+ compounds, the reactions of CO2 to CH3OH and CH3OH to C2+ compounds take place at 200–300 °C and 400 °C, respectively, over bifunctional catalysts. Therefore, investigation of the reaction conditions, catalyst properties, and catalytic performance for CO2 to CH3OH and CH3OH to C2+ products is necessary.

Methanol

As mentioned earlier, one of the possible targets of CO2 hydrogenation is to convert CO2 to CH3OH. Significant progress has been made in this area recently, especially in developing copper (Cu)- and indium (In)-based catalysts30,31. Recent publications have dealt with Cu–ZnO composites, whose CH3OH selectivity ranges from 30 to 70% at CO2 conversions less than 30% under typical reaction conditions (temperature: 220–300 °C, pressure <5 MPa, H2/CO2 = 3)32,33. By increasing the pressure to 36 MPa and H2/CO2 molar ratio to 10, the single pass CO2 conversion can be increased to 95.3% with 98.2% methanol selectivity over a Cu–ZnO–Al2O3 catalyst34. When Cu nanoparticles (NPs) are encapsulated in metal organic frameworks (MOFs) and strongly interact with their secondary structural units, the resultant metal NPs@MOFs (e.g., Cu ⊂ UiO-6635 and CuZn@UiO-bpy36) show enhanced activity and 100% CH3OH selectivity, while preventing the agglomeration of the Cu NPs. In addition, ZrO2 is a noted promoter or support in Cu-based catalysts for CTM hydrogenation37,38.

Indium-based materials have shown promise as alternatives for CO2 conversion to methanol. Pure In2O3 can convert 7.1% of CO2 with 39.7% selectivity to CH3OH at 330 °C and 5 MPa39. A Pd/In2O3 catalyst with many interfacial sites and oxygen vacancies enhances CO2 adsorption, achieving CO2 conversions of above 20% with a methanol space time yield (STY) of 0.89 gMeOH gcat−1 h−1 at 300 °C and 5 MPa31. In2O3/ZrO2 catalysts significantly boost the methanol selectivity to 99.8%, with a CO2 conversion of 5.2% and long-term stability of 1000 h under industrially relevant conditions40. Besides the Cu and In-based catalysts, great progress has also been achieved with ZnO–ZrO2 solid solution catalysts, as well as Pd/Pt-based catalysts41–43. The ZnO–ZrO2 solid solution catalysts have achieved CH3OH selectivities of 86–91% under a GHSV of 24,000 mL g−1 h−1 with high thermal stability after being tested for more than 500 h; it also shows a strong resistance to sulfur-containing molecules31. In 2014, Norskov’s group reported a Ni–Ga bimetallic catalyst for CO2 hydrogenation to CH3OH at 0.1 MPa, whose STY reached 0.64 gMeOH gcat−1 h−1 at 210 °C44. Subsequently, a series of noble metal based catalysts, such as Ga–Pd45, Au–CeOX/TiO246, and Pt–MoOX/Co-TiO247, were developed to convert CO2 to CH3OH at low pressure or low temperature. Similarly, Fan’s group achieved low-pressure CH3OH synthesis via another series of multiple-metal catalysts that included In2O3, like Ni–In–Al/SiO2 and La–Ni–In–Al/SiO2, starting with a phyllosilicate precursor3,48, and achieving CH3OH STYs of above 0.011 gMeOH gcat−1 h−1 at 255 °C and 0.1 MPa.

Dimethyl ether (DME)

There has been rapid development in DME synthesis from CO2 hydrogenation using CH3OH synthesis catalysts hybridized with CH3OH coupling catalysts15. The effect of promoters, supports, and synthesis conditions have been explored42,43,49. For example, the acidic sites on γ-alumina surfaces and the CuAl2O4 spinel phase can be regulated by promoters like gallium or zinc oxides, resulting in higher stability for Cu NPs during CO2-to-DME49. To date, CO2 conversion and DME selectivity mostly vary between 35–80% and 5–50%, respectively15, but CO2 conversion can reach up to 97% at 280 °C over a Cu–Zn–Al/HZSM-5 catalyst by drastically increasing the reaction pressure (to 36 MPa)34. In addition, interesting results have been reported on core–shell structured hybrid catalysts with the MeOH synthesis catalysts at the core and the MeOH dehydration catalysts forming the shell50,51. Compared with traditional hybrid catalysts prepared by physically mixing the components, these novel core–shell catalysts have received much attention in the literature due to their unique structures and ability to valorize CO2 by improving conversion and DME selectivity.

Light olefins, aromatics, and gasoline

MeOH can not only be dehydrated to DME, but also serve as an intermediate to synthesize hydrocarbon chains, (CH2)n, and final products, such as olefins, aromatics, and gasoline. As mentioned above, defective indium oxide (In2O3) with oxygen vacancies is shown to be effective for CO2 hydrogenation to CH3OH, while In2O3 mixed with SAPO-34 is attractive for efficient CO2 conversion to CH3OH and subsequent selective C–C coupling of CH3OH to form light olefins52. The addition of Zr into In2O3 is helpful for creating more oxygen vacancies, enhancing CO2 chemisorption and stabilizing both surface intermediates and active In NPs53,54. Similarly, a high yield of light olefins can also be achieved by composite catalysts, such as ZnZrO16, ZnGaO55, and CuZnZr56 mixed with SAPO-34. As shown in Table 1 (Entries 1–5, 9–13), the selectivity of light olefins, represented by the C2–C4= column in the table, can be as high as 90%, while the CH4 selectivity is less than 5% of the hydrocarbon products with 15–30% CO2 conversions over most bifunctional catalysts tested, which deviates from the Anderson–Schulz–Flory (ASF) distribution.52,54 This result is a significant breakthrough in the synthesis of light olefins. When the zeolite is changed from SAPO-34 to HZSM-5, more C5+ compounds are produced than light olefins. A 78.6% selectivity of gasoline-range hydrocarbons, with only 1% CH4 selectivity, was obtained from the tandem In2O3/HZSM-5 catalyst26. When In2O3 is replaced by ZnAlOx or ZnZrO, CH3OH is synthesized on the metal oxide surface and then converted to olefins and aromatics inside the HZSM-5 pores with an aromatic selectivity of 73%, which is attributed to a shielding of the external Brønsted acid sites of HZSM-5 by ZnAlOx57. Therefore, the type of product is affected by both the character of the metal oxides and the geometries of the zeolites that determine the confinement of the hydrocarbons. Furthermore, as mentioned previously, catalysts with product yields exceeding the ASF distribution limit were recently reported that follow the methanol reaction mechanism-based CO/CO2 hydrogenation. However, fundamental understanding of this ASF distribution deviation is still lacking. Jiao et al.58 observed that ketene (CH2CO) can be formed from the reaction between surface CO and CH2 species, blocking the surface polymerization, and thus breaking the ASF distribution. Another important reason suggested for the reported ASF distribution deviation is the use of bifunctional catalysts with two types of active sites.

Table 1.

Representative catalysts and their performance for hydrogenation of CO2 to C2+ species.

| Entry | Catalysts | CO2 con./% | CO select./% | CH select./% | Hydrocarbon distribution/%a | GHSV/ml g−1 h−1 | Temp./°C | P/MPa | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH4 | C2–C40 | C2–C4= | C5+ | |||||||||

| C2+ hydrocarbons based on methanol reaction mechanism | ||||||||||||

| 1 | In2O3/ZrO2+SAPO-34 | 19.0 | 87.0 | 13.0 | 4.0 | 12.0 | 84.0 | – | 3000 | 400 | 1.5 | 53 |

| 2 | In2O3/SAPO-34 | 15.3 | 68.3 | 31.7 | 2.7 | 13.7 | 81.9 | 1.7 | 9000 | 380 | 3.0 | 52 |

| 3 | In2O3–ZrO2/SAPO-34 | 26.2 | 63.9 | 36.1 | 2.0 | 21.5 | 74.5 | 2.0 | 9000 | 380 | 3.0 | 52 |

| 4 | In–Zr/SAPO-34 | 29.0 | 78.2 | – | 4.1 | 9.2 | 83.9 | 2.8 | 15,750 | 400 | 3.0 | 54 |

| 5 | ZnZrO/SAPO-34 | 12.6 | 47.0 | – | 3.0 | 14.0 | 80.0 | 3.0 | 3600 | 380 | 2.0 | 16 |

| 6 | (CuO–ZnO)–Kaolin/SAPO-34 | 50.4 | 7.5 | – | 13.6 | 15.8 | 70.6 | 0.0 | 1800 | 400 | 3.0 | 145 |

| 7 | Zn–Ga–O/SAPO-34 | 13.0 | 46.0 | – | 1.0 | 11.0 | 86.0 | 2.0 | 5400 | 370 | 3.0 | 55 |

| 8 | CuZnZr@Zn–SAPO-34 | 19.6 | 58.6 | 41.4 | 14.6 | 20.2 | 60.5 | 4.8 | 3000 | 400 | 2.0 | 56 |

| 9 | In2O3/HZSM-5 | 13.1 | 44.8 | – | 1.0 | – | – | 78.6 | 9000 | 340 | 3.0 | 26 |

| 10 | Cr2O3/HZSM-5 | 33.6 | 41.2 | – | 3.0 | 15.7 | 3.1 | 78.2 | 1200 | 350 | 3.0 | 146 |

| 11 | Fe2O3/HZSM-5 | 7.1 | 73.5 | – | 2.0 | – | – | 70.5 | 9000 | 340 | 3.0 | 26 |

| 12 | ZnAlOx and HZSM-5 | 9.1 | 57.4 | 42.6 | 0.5 | 6.7 | 10.7 | 80.3 | 2000 | 320 | 3.0 | 57 |

| 13 | ZnZrO/HZSM-5 | 14.1 | 43.7 | 57.3 | 0.3 | 14.5 | 4.9 | 80.3 | 1200 | 320 | 4.0 | 71 |

| C2+ hydrocarbons based on CO2 modified FTS mechanism | ||||||||||||

| 14 | FeZnK–NC | 34.6 | 21.2 | 78.8 | 24.2 | 7.1 | 40.6 | 28.1 | 7200 | 320 | 3.0 | 120 |

| 15 | Fe–2K | ~30.0 | 22.0 | 74.0 | 31.1 | 14.9 | 32.4 | 21.6 | – | 320 | 2.0 | 82 |

| 16 | 10Fe0.8K0.53Co | 54.6 | 2.0 | 98.0 | 19.3 | 7.8 | 24.9 | 48.0 | 560 | 300 | 2.5 | 91 |

| 17 | N–K–600-0 | 43.1 | 26.1 | 73.9 | 35.5 | 6.8 | 36.9 | 20.8 | 3600 | 400 | 3.0 | 121 |

| 18 | 1Fe–1Zn–K | 51.0 | 6.0 | 85.1 | 34.9 | 7.8 | 53.6 | 3.7 | 1000 | 320 | 0.5 | 147 |

| 19 | 35Fe–7Zr–1Ce–K | 57.3 | 3.1 | 96.3 | 20.6 | 7.9 | 55.6 | 15.9 | 1000 | 320 | 2.0 | 76 |

| 20 | Fe–Co/K–Al2O3 | 41.4 | 14.8 | 85.2 | 21.7 | 6.3 | 45.0 | 27.0 | 9000 | 320 | 3.0 | 77 |

| 21 | C–Fe–Zn/K | 54.8 | 4.6 | 94.4 | 23.1 | 8.5 | 57.4 | 11.0 | 1000 | 320 | 2.0 | 78 |

| 22 | Na–Fe3O4/HZSM-5 | 22.0 | 20.1 | – | 4.0 | – | – | 79.4 | 4000 | 320 | 3.0 | 17 |

| 23 | ZnFeOx–4.25Na/S–HZSM-5 | 36.2 | 11.0 | 89.0 | 8.2 | 13.3 | 3.2 | 75.4 | 4000 | 320 | 3.0 | 93 |

| 24 | Fe–Cu–K–La/TiO2 | 23.1 | 33.0 | 67.0 | 19.4 | – | – | 67.2 | 3600 | 300 | 1.1 | 115 |

| 25 | Na–ZnFe2O4 | 34.0 | 11.7 | – | 9.7 | – | – | 58.5 | 1800 | 340 | 1.0 | 116 |

| 26 | K–Fe | 43.9 | 10.1 | 89.9 | 12.2 | – | – | 56.6 | 750 | 300 | 1.5 | 148 |

| 27 | 92.6Fe7.4 K | 41.7 | 6.0 | 94.0 | 10.9 | 23.0 | 6.5 | 59.6 | 560 | 300 | 2.5 | 122 |

| 28 | 10Fe4.8 K | 35.2 | 9.0 | 91.0 | 8.1 | 4.3 | 16.4 | 71.2 | 560 | 300 | 2.5 | 91 |

| 29 | CuFeO2−24 | 16.7 | 31.4 | – | 2.4 | – | – | 64.9 | 1800 | 300 | 1.0 | 123 |

| 30 | Na–CoCu/TiO2 | 18.4 | 30.2 | – | 26.1 | – | – | 42.1 | 3000 | 250 | 5.0 | 96 |

| 31 | Co/MIL-53(Al) | 25.3 | 6.6 | 18.7 | 35.2 | – | – | 35.0 | 800 | 260 | 3.0 | 94 |

| Entry | Catalysts | CO2 con./% | CO select./% | HC select./% | MeOH select./% | C2+OH select./% | GHSV/ml g−1 h−1 | Temp./°C | P/MPa | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C2+ alcohols from CO2 hydrogenation | ||||||||||

| 32 | CuZnFe0.5K0.15 | 42.3 | 6.9 | 56.4 | 4.7 | 32.0, C2+OH | 5000 | 300 | 6.0 | 99 |

| 33 | Mo1Co1K0.8 sulfide | 28.8 | – | – | 70.9 | 10.9, C2+OH | 3000 | 320 | 5.0 | 149 |

| 34 | 1 wt%Pt/Co3O4 | – | – | – | – | 82.5, C2+OH | – | 200 | 8.0 | 98 |

| 35 | PdCu NPs/P25 | – | – | – | – | 92.0, EtOH | – | 200 | 3.2 | 150 |

| 36 | RhFeLi/TiO2 | 15.7 | 12.5 | 53.9 | 2.2 | 31.3, EtOH | 6000 | 250 | 3.0 | 18 |

aThe hydrocarbon distribution was calculated without CO

Reaction mechanisms

For most catalysts, the rate-determining step for methanol synthesis is CO2 activation (R1)59,60, which includes chemisorption of CO2 and electron transfer from the catalyst to CO211,61. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations have shown that different catalysts activate CO2 through electron transfer between different orbitals62. For example, in PtCo-based catalysts, carbon in the CO2 tends to bind to the Pt sites with an η1-CPt bonding mode, while the O in the CO2 prefer to combine with the reduced Mδ+ cations in metal oxides with η1-OMδ+ configuration63. In addition, oxygen vacancies on metal oxide surfaces and Lewis acid sites have also been shown to enhance CO2 activation37,55, stabilize intermediates64, and reduce sintering52. DFT calculations reveal that an oxygen-defective surface could be created through direct thermal desorption or exposure to a reducing agent54. After activation, CO2 proceeds to form methanol, most likely via a formate intermediated pathway.

The use of DFT and ab initio molecular dynamics sampling techniques on Cu–ZnO32, Cu–Pd42,65, In66, and Ga48,67 catalysts suggest that methanol synthesis occurs via a formate intermediate (See Fig. 1b). However, while calculations for Cu–ZnO interfacial sites suggest a formate intermediate32, calculations for the near surface regions suggest a CO intermediated pathway68. In addition, the calculations indicate that H2O produced in situ from both RWGS and CH3OH formation on Pd incorporated Cu catalysts accelerates CO2 conversion to methanol by reducing the kinetic barriers by 0.2–0.7 eV for O–H bond formation steps42,65. On In-based catalysts, defective In2O3 surfaces have different CO2 activation barriers66. The synthesized methanol can then be transformed into high-value C2+ compounds, including DME, lower hydrocarbons, and gasoline via the hydrocarbon-pool mechanism in which an organic center is trapped in the zeolite pores and acts as a co-catalyst, as depicted in Fig. 1c26,69,70. The DFT results indicate that the rate-determining step is generally CO2 activation during conversion to methanol over the hybrid catalysts, whose ΔG0 at 320 °C reaches 47 kJ/mol, which is much higher than that of the subsequent dehydration reaction (e.g., ΔG0 = −87 kJ/mol for methanol to xylene at 320 °C)71,72; thus, an efficient CH3OH synthesis catalyst is beneficial for the subsequent formation of C2+ compounds.

As indicated above, the bifunctional catalysts consist of CH3OH synthesis and dehydration catalysts. However, is the bifunctional catalyst mechanism also the simple sum of the two individual reactions? Li et al.16 estimated the CH3OH selectivity based on the hydrocarbon selectivity for a hybrid catalyst and found that it was much higher than that for ZnZrO alone. This result clearly indicates that the products from the bifunctional catalysts are not a simple sum of the two individual reactions, and these two catalysts have a large synergistic effect. Thus, further study on the direct CO2 hydrogenation to C2+ products over bifunctional catalysts is still desirable.

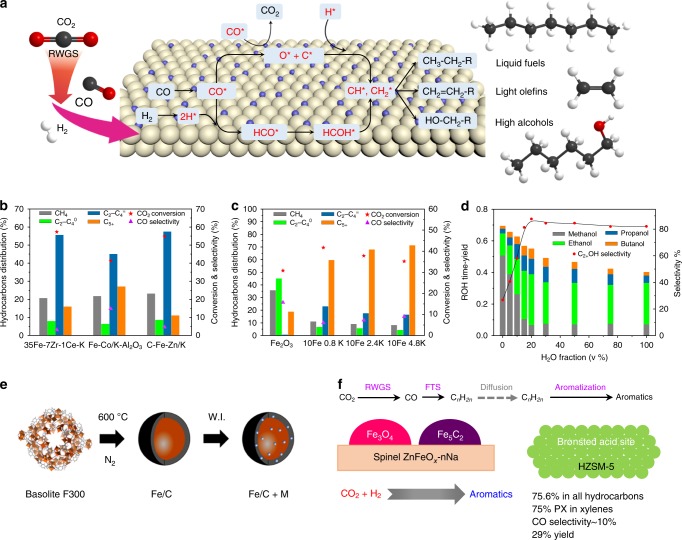

Fischer–Tropsch synthesis (FTS)-based CO2 hydrogenation

Heterogeneous FTS-based CO2 hydrogenation can be realized in either one or two reactors, although the single reactor process dominates. The direct one-reactor conversion system has drawn much attention due to its ease of operation and thus lower CO2 conversion cost. This process integrates the reduction of CO2 to CO via the RWGS reaction and hydrogenation of CO to hydrocarbons via FTS. An efficient catalyst for generating C2+ products, which generally refer to light olefins, liquid fuels, and higher alcohols, should be active for both RWGS and FTS under the same conditions (Fig. 2a, R5–R7). The product distribution can be wide, depending on the structure and composition of the catalysts. Iron (Fe), cobalt (Co), and ruthenium (Ru) based supported catalysts, with appropriate promoters, are predominantly used in this area.

| R5 |

| R6 |

| R7 |

Fig. 2. CO2 hydrogenation to C2+ products via the FTS-based mechanism.

a Scheme of CO2 modified FTS-based catalytic mechanism. b–d CO2 hydrogenation via the FTS mechanism for production of light olefins, liquid fuels, and higher alcohols76–78,91,98. e Synthesis strategy for an Fe-based catalyst. (Reprinted with permission from Ramirez et al.83. Copyright (2018) American Chemical Society). f Selective production of aromatics from the CO2 hydrogenation process over a ZnFeOx–nNa/HZSM-5 catalyst. (Reprinted with permission from Cuiet al.93. Copyright (2019) American Chemical Society).

(The values of ΔRH are reproduced from the literature73,74).

Prior to FTS, the RWGS reaction converts CO2 to CO to form dissociatively adsorbed *CO precursor molecules on the catalyst surface. Therefore, an understanding of the reaction conditions and catalytic performance for the RWGS reaction is necessary. Since RWGS (R6) is endothermic, it requires high temperatures for reasonable conversions. CO selectivity up to 100% can be achieved at 200–600 °C using the primary RWGS catalysts, such as Cu- and noble metal (Pt, Pd, Rh)-based catalysts, with CO2 conversions up to 50%75.

Light olefins

Light olefins, including C2–C4 alkenes, are important target products for the FTS-based CO2 hydrogenation process. Fe-based catalyst systems are considered to be most suitable for olefin production by applying appropriate promoters, textural additives, or supports to form the required active sites for the different reaction stages. Fe and Co-based catalysts with alkali metal promoters (e.g., 35Fe–7Zr–1Ce–K76, Fe–Co/K–Al2O377, and C–Fe–Zn/K78) are reported to be highly active for FTS to produce C2+ products79,80 with as high as 57% selectivity at 40–60% CO2 conversion (Fig. 2b). The most effective promoters are alkali metals, especially Na and K, as they limit the formation of methane while improving the selectivity to C2+ products81. Meiri et al.82 pointed out that the introduction of potassium can stabilize the texture of the Fe–Al–O spinel, increase the surface content of Fe5C2, and strengthen CO2 adsorption. In one study of fourteen different kinds of promoters added individually to MOF-derived Fe/C catalysts (Fig. 2e), only K dramatically enhanced the olefin selectivity from 0.7 to 36%83. Martinelli et al.84 concluded that the K-loading did not influence the CO2 conversion, but increased the olefin/paraffin ratio and the average molecular weight of the products. Besides the alkali metals, other metals such as Cu, Zn, Ni, Zr, Mn, and Pt can also be used to modify Fe-based catalysts83. For example, bimetallic Fe–Cu/Al2O3 catalysts can suppress CH4 formation and thus exhibit higher amounts of C2–C7 production compared with pure Fe/Al2O3 catalysts85.

Support material is another important factor that can influence catalyst activity and product selectivity by affecting the dispersion of active metals and the interactions between reactive intermediates and the support material. The support materials for Fe-based FT catalysts can be divided into metal oxides (e.g., ZrO2, CeO2, and Al2O3) and carbonaceous materials (e.g., MOFs, mesoporous carbon, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, and organic precursors to mesoporous carbon). Wang et al.86 studied several supports and found that a ZrO2 supported (K-Fe/ZrO2) catalyst exhibited the highest selectivity to lower olefins, while SiO2 was not suitable for the CO2-FTS reaction. Since Fe carbides are generally considered to be the active phase in FTS catalysis, carbon materials are naturally considered as good support materials for Fe catalysts; indeed, they have demonstrated excellent catalytic performance for olefin synthesis. Carbon support materials can improve the dispersion of the active metals and lead to higher selectivity to olefins87. An Fe-based core–shell nanocatalyst with Fe3O4 and Fe5C2 in the core and partially graphitized carbon in the shell was prepared to efficiently convert CO2 to C2–C4= olefins. The olefin/paraffin ratio was increased by carefully controlling the content of carbon to improve the accessibility of reactants to the active sites88. CNTs and graphene are also good carbon supports with superior thermal and chemical stability87,89. For example, a honeycomb-structured graphene (HSG) with a special meso-macroporous architecture was devised to confine K-promoted Fe NPs for the CO2-to olefins reaction. The FeK1.5/HSG catalyst can increase the selectivity of C2–C4= to 59.0% and the stability to 120 h, due to K promotion and HSG confinement effects89. Similarly, Ding et al. have successfully improved the catalytic activities by combining the K promoter and ZrO2 support with sufficient oxygen defects90.

C5+ products

Liquid fuels (e.g., gasoline and diesel) and other value-added chemicals (e.g., aromatics and isoparaffins) are also desired products from CO2 hydrogenation via FTS. Jiang et al.91 prepared Fe- and FeCo-based catalysts and achieved, when promoted with an appropriate amount of K, ≥54.6% CO2 conversions and ≥47.0% C5+ selectivity (Fig. 2c). A Na–Fe3O4/HZSM-5 catalyst with three types of active sites was developed by Wei et al., demonstrating that 22% of CO2 can be directly converted to gasoline with a selectivity of 78%17. When HZSM-5 was changed to HMCM-22, aromatization was suppressed, while isomerization was promoted due to the appropriate Brønsted acid properties of HMCM-22 and the special lamellar structure consisting of two independent pore systems. Thus, 57% selectivity of isoparaffins was obtained over the Na–Fe3O4/HMCM-22 catalyst, while the values over Na–Fe3O4/HZSM-5 and Na–Fe3O4 were only 34 and 6%, respectively92. Similarly, aromatics are important feedstocks with applications in the synthesis of various polymers, petrochemicals, and medicines. ZnFeOx–nNa/HZSM-5 catalysts can achieve 75.6% selectivity to total aromatics at a CO2 conversion of 41.2% (Fig. 2f)93.

Owing to superior ability for chain growth, stability, and lower activity for the WGS reaction, Co-based catalysts have also been applied to produce long-chain C5+ hydrocarbons. Recently, a pure Co-based catalyst without promoters was reported to display high performance for both CO-FTS and CO2-FTS94,95. The Co/MIL-53(Al) catalyst was first found to exhibit 47.1% CO conversion and 68.6% selectivity to C5+ products. When it was applied to CO2-FTS, 35.0% selectivity to C5+ was still achieved at 260 °C. Furthermore, different kinds of promoters and support materials are employed to tune the product distribution towards heavier hydrocarbons. Shi et al. prepared a promoted Co–Cu bimetallic catalyst for CO2 hydrogenation based on consideration of Cu as a popular RWGS catalyst. For example, with the introduction of Na as a promoter to a CoCu/TiO2 catalyst, the CH4 selectivity significantly decreased from 89.5 to 26.1%, while the C5+ selectivity increased from 4.9 to 42.1%, with an excellent stability of more than 200 h96. He et al.97 reported the bimetallic Co6/MnOx nanocatalyst with synergism between Co and Mn for 15.3% CO2 conversion and 53.2% C5+ selectivity.

Higher alcohols

Reports of higher alcohol (C2+OH) production are less prevalent compared to methanol and other C2+ products of CO2 hydrogenation. However, C2+OH alcohols have higher energy density and wider applications as fuel additives. The formation of higher alcohols is a parallel reaction competing with formation of hydrocarbons during the FTS process, resulting in much lower selectivity to C2+OH. Furthermore, the synthesis of C2+OH is difficult, as both C–C coupling and OH formation are required. Interestingly, water was found to enhance the selectivity of higher alcohols to 82.5% over a 1 wt% Pt/Co3O4 catalyst (Table 1, Entry 34)98. Moreover, the C2+OH selectivity was affected by the volume fraction of water, increasing dramatically with small amounts (<20 vol%) of added water, and then decreased slightly with further addition of water (Fig. 2d). The promoting effect of water was attributed to assisting methanol dissociation to form more *CH3 species. *CH3 then can react with *CO to form *CH3CO, which will be further hydrogenated to ethanol (EtOH). Also, ordered Pd–Cu NPs, with charge transfer between Pd and Cu, are reported to efficiently convert CO2 to ethanol with 92.0% selectivity (Table 1, Entry 35). The rate-determining step of *CO hydrogenation to *HCO can be promoted on a Pd–Cu NPs/P25 catalyst, leading to lower *CO coverage and weaker *CO adsorption. Similarly, Cu–Fe and Zn–Fe interactions in the Fe-doped K/Cu–Zn catalyst have synergistic interactions, which can facilitate catalyst reduction and metal dispersion, as well as increase the yield of higher alcohols99. The reduction temperature can be regulated to obtain different phase compositions over the Co-based catalysts. For example, an alumina-supported catalyst reduced at 600 °C (CoAlOx−600) contained coexisting Co–CoO phases and exhibited 92.1% selectivity to ethanol at 140 °C, due to the formation of acetate intermediates from formate by insertion of *CHx100.

Reaction mechanisms

Although many successful catalysts have been developed for the CO2-FTS reaction, the nature of the active sites and reaction mechanism remain controversial. In view of the catalysts reported to date, the mechanism of the RWGS reaction can be assigned to either the decomposition of *HOCO intermediates or to direct C–O bond cleavage to produce *CO75. Ko et al.101 pointed out that CO2 can be activated to anionic CO2δ− through charge transfer from the pure and bimetallic alloy surfaces with bending of the structure and splitting of the π orbital. Both the adsorption energy of CO2δ− and the reaction energy for CO2 dissociation are a linear function of adsorption energies of *CO and *O. To facilitate further *CO hydrogenation, the interaction between *CO and the catalyst interface need to be enhanced; otherwise, *CO is desorbed with concomitantly increased CO selectivity. According to the most-accepted reaction mechanism, during the FTS process, steps including *CO dissociative chemisorption on the active sites with hydrogen-assisted insertion to form *CHx intermediates, initiation of chain growth through the coupling of *CHx, and the termination of chain growth through further hydrogenation, dehydrogenation, or insertion of non-dissociatively adsorbed *CO happen successively on the catalyst surface (Fig. 2a). *CO intermediates can be produced through the RWGS reaction, followed by the FTS reaction. According to modeling and kinetic analysis by Willauer et al., the RWGS reaction rate can reach 3.5 × 105 s−1 initially and decreases to 0.032 s−1 within 2 s, while the FTS reaction rate is zero initially and increases to 0.004 s−1 at 18.7 s102. The FTS reaction is the rate-limiting step due to the much lower reaction rate. The FTS reaction during the CO2 hydrogenation process is limited by the reaction between the adsorbed CO and H2 to form *HCO intermediates, as reported by Pour et al.103 after evaluating different kinetic models and applying a genetic algorithm (GA) approach and the Levenberg–Marquardt (LM) method. Thus, efficient active sites for the FTS reaction are important for the whole CO2 hydrogenation process. Also, chain propagation in FTS is still in dispute based on the basic C–C coupling mechanisms104. The most limiting process or factor during FTS-based CO2 hydrogenation that should be addressed in future research may be affected significantly because of the various thermodynamic and physical properties of the reactions. For example, when using higher reaction temperatures (>300 °C), mass transfer appears to become the rate-limiting step instead of the surface reaction at relatively low temperatures105.

Concerning the active sites in iron and cobalt catalysts, several phases are present and change dynamically during reaction. The catalyst transformation in structure and composition has several steps with their own kinetic regimes106. The reduced iron catalysts mainly consist of α-Fe and Fe3O4 with extremely low activity at the beginning of FTS. Fe3O4 is capable of activating CO2 to CO via the RWGS reaction81,107. Then, the α-Fe reacts with the dissociatively adsorbed CO to form iron carbide (e.g., Fe5C2), generating Fischer–Tropsch activity. Thus, the catalytic sites of iron carbides appear to be active for CO activation and chain growth81. Considering the different functions of iron species and the zeolites’ superior properties of acid sites for oligomerization/aromatization/isomerization, a multifunctional structure Na–Fe3O4/HZSM-5 catalyst was developed and achieved as high as 78% selectivity to gasoline, with only 4% methane generated17. Therefore, researchers need to focus not only on optimizing the composition and structure of the catalysts, but also on developing new catalytic systems with desired properties by using comprehensive approaches that can directly control the microstructures of the catalysts and be used for more accurately identifying the reaction pathways during FTS-based CO2 hydrogenation.

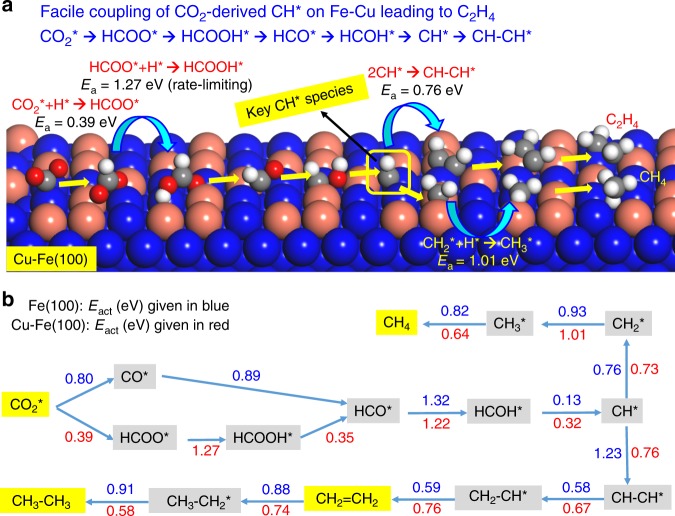

It is generally accepted that bulk Fe catalysts show insufficient catalytic performance and that the addition of promoters can enhance the selectivity to C2+ products. However, the essential basis of the promotion effect remains unclear. More investigation needs to focus on the reaction mechanism. For example, the reaction pathways over Fe/Al2O3, Cu/Al2O3, and Fe–Cu/Al2O3 catalysts are different, resulting in different product distributions85. Cu has high activity for the RWGS reaction instead of the CO2 methanation reaction, leading to more surface *CO. Thus, bimetallic Fe–Cu/Al2O3 catalysts form more CO, which leads to more C2+ hydrocarbons compared to the Fe/Al2O3 catalyst. Nie et al. also investigated the mechanism of CO2 hydrogenation to methane and C2 hydrocarbons over Fe(100) and Cu–Fe(100) surfaces and showed that the hydrogenation barrier of CH2* species is higher than those for C–C coupling and CH–CH* conversion to ethylene on Cu–Fe bimetallic catalysts (see Fig. 3)108, which results in a more selective process to ethylene. The addition of K to Fe–Cu/Al2O3 catalysts can further inhibit methanation and enhance the production of olefin-rich C2–C4 hydrocarbons by increasing the surface coverage of carbon85. DFT calculations show that the presence of K on Fe-based surfaces can enhance the CO2 adsorption strength and reduce the CO2 dissociation barrier (e.g., 2.36 eV for oct2-Fe3O4(111) versus 1.13 eV for K/oct2-Fe3O4(111))109. Therefore, the introduction of promoters can modify the surface electronic features.

Fig. 3. Mechanistic insight into C–C coupling over Fe-Cu bimetallic catalysts.

a Mechanism of CO2 hydrogenation to C2H4 over a Cu–Fe(100) surface. b Reaction pathways for production of CH4, C2H4, and C2H6 from CO2 hydrogenation on Fe(100) and Cu–Fe(100) surfaces at 4/9 monolayer coverage. The kinetic barrier for each elementary step is given in eV. (Reprinted with permission from Nie et al. 108. Copyright (2017) American Chemical Society).

Outlook

Methanol reaction based CO2 hydrogenation

The primary challenge in converting CO2 to value-added products is low selectivity due to excessive formation of CO and the large amount of water (H2O) generated. CO and CH4 are both formed due to partial reduction and cracking, respectively, during dehydration at the elevated temperatures (≥400 °C) generally employed for dehydration. To date, it has limited conversion (<30%) towards desired products (Table 1, Entries 1–5, 7–13). In addition, H2O produced from CH3OH synthesis and dehydrative coupling further complicates separations and, in some cases, deactivates the catalyst. However, altering the zeolite structure has been shown to alter product distributions and increase selectivity to desired products, which was realized by increasing the space velocity during catalytic CO2 hydrogenation over In2O3 combined with zeolites26,110. Through the introduction of CO conversion promoters, such as In–FeK, In–CoNa, or CuZnFe/zeolites, bifunctional catalysts can be upgraded to reduce CO formation. In addition, these catalytic CO2 conversion technologies face several other challenges, such as revealing the relationship between product type and molecular sieve type, increasing the CO2 conversion and final product yield via improving the structures of bifunctional catalysts, as well as further elucidating the reaction mechanisms. More detailed information on these points is depicted below.

First, more research on the zeolite properties is needed. By varying the zeolite structure, the product distribution can be better controlled. For example, HZSM-5 zeolite is selective towards DME and gasoline, whereas SAPO molecular sieves are preferred for light olefin generation. However, the structure-property relations between zeolite properties and CO2 hydrogenation activity have not yet been systematically investigated. Because many variables and conditions exist during zeolites synthesis (e.g., synthesis template, crystallization temperature, and Si/Al ratio), the relationship between zeolite properties and CO2 hydrogenation activity remains an active area of study111–113. Shape-selective catalysis was identified as a factor in these catalysts, as SAPO zeolite windows allowed only small linear hydrocarbons to pass, while H-ZSM zeolite windows allowed much larger branched and linear hydrocarbons to leave114. In addition, DFT calculations have linked density of surface Lewis acids and defects in the zeolite structure with dehydration activity115,116.

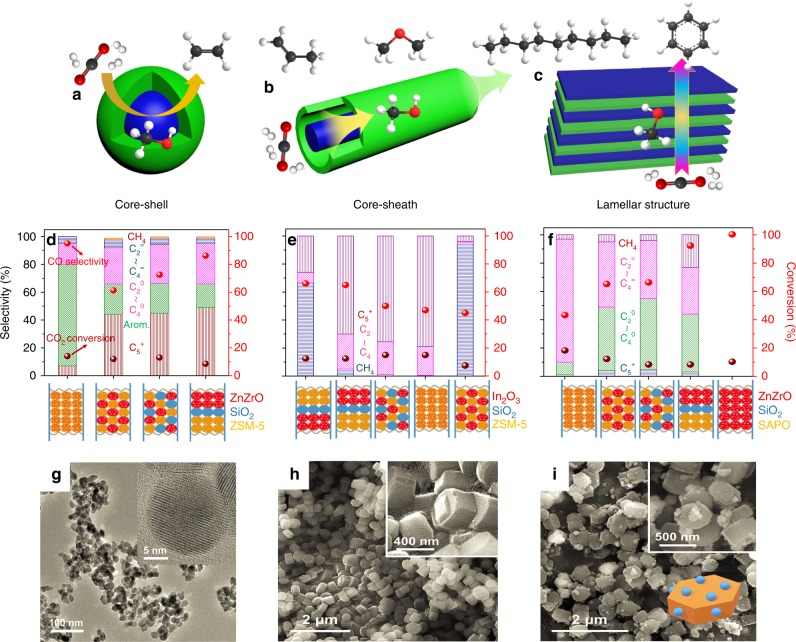

Second, additional research on the structure of bifunctional catalysts is required. To improve CO2 conversion and final product yield, the morphology and structure of the bifunctional catalysts should be optimized, rather than just making physical mixtures. The precise control of the desired morphology and structure of the catalyst is a significant and synthetically challenging task (see Fig. 4a–c), as shown by the example of utilizing core–shell structures incorporating multiple-metal oxide cores to direct the growth of zeolite shells. Additionally, catalysts with core–sheath and lamellar structures are reported to exhibit high activity and stability for C=O bond hydrogenation117. Bifunctional catalysts can be assembled via layer-by-layer growth methods and probably exhibit better performance. Furthermore, efforts to improve important intrinsic factors, like the dispersion and crystallite size of active metals on methanol synthesis catalysts and the acid strength together with acid sites on the zeolites, as well as the methods of integration of the active components, should be made. As shown in Fig. 4d–f, different product distributions were obtained when the methanol synthesis catalyst and the zeolite were synthesized with different spatial arrangements16,26,71. The TEM and SEM images in Fig. 4g–i indicate that ZnZrO particles can be highly dispersed on the surface of HZSM-5 and maintain their own structures16,26,71. Sufficient physical mixing of the two components seems to be better than the granular form or a dual-bed separated in space by a layer of quartz sand.

Fig. 4. The structure and performance of bifunctional catalysts.

a–c Proposed structures of bifunctional catalysts. d–f Hydrogenation of CO2 over bifunctional catalysts, which are integrated methanol synthesis catalyst and zeolites, with different spatial arrangements. (Adapted with permission from Li et al.71. Copyright (2019) Elsevier); Gao et al.26. Copyright (2017) Springer Nature; Li et al.16. Copyright (2017) American Chemical Society). g–i TEM and SEM images of bifunctional catalysts. (Reprinted with permission from Li et al.71. Copyright (2019) Elsevier).

Analyzing the integration between methanol synthesis catalysts and zeolites remains a challenge. DFT calculations may be the most efficient method to explore the interactions between CH3OH synthesis catalysts and dehydration catalysts. However, the information gained from DFT calculations can be limited because the systems studied are under idealized conditions, which are different from the ones in a packed bed reactor. As computing power with machine learning continues to increase, more complex and realistic catalytic systems can be modeled, which provides deep insight into the mechanism of CO2 hydrogenation to olefins, such as the design of 3D nanocrystal tandem catalysts with multiple interfaces for CO2 hydrogenation.

FTS-based CO2 hydrogenation

The major obstacles of FTS-based CO2 hydrogenation lie in the thermal stability of CO2 and the complicated reaction mechanism with a wide product distribution. With the RWGS process being endothermic and FTS being exothermic, both need to be efficiently catalyzed under the same conditions, which sets a very strict requirement for the catalytic system. The designed catalysts should be effective for the RWGS reaction and also active enough for the subsequent FTS reaction. Different active sites must be precisely tuned and carefully dispersed on the support materials. These challenges will be discussed in view of different kinds of products: olefins, C5+ hydrocarbons, and higher alcohols.

The first, challenge to be discussed is production of light olefins. In spite of the promising results discussed, major challenges still remain. For example, the selectivity of C2–C4= can be above 80% for catalysts with methanol as the reactive intermediate, while only about 50% selectivity to C2–C4= is achieved on the catalysts for CO2 conversion via FTS (Table 1, Entries 14–21). The key to improve the C2+ selectivity is to develop catalysts that have compatible bifunctional active sites for the two reaction steps, namely, *CO generation and subsequent *CO hydrogenation. The appropriately engineered reaction window is extremely important. The consequence of the incompatible activity of these two different types of active sites could be high CH4 selectivity (~30%, Table 1, Entries 14–21), as is suggested by the activation energy of RWGS being higher than that of CH4 formation (81.0 and 59.3 kJ/mol, respectively) for Fe-based catalytic CO2 hydrogenation105. As shown in Table 1 (Entries 1–8, 14–23), the reaction temperature (~320 °C) for the CO2-FTS process is lower than that for the methanol-mediated route (~380 °C). Thus, the CO selectivity (~30%) is dramatically reduced due to relatively low temperatures for the RWGS reaction, leading to improved hydrocarbon selectivity.

Many researchers have tried to provide possible solutions for improving C2+ selectivity by adjusting the structures and compositions of the catalysts. Specifically, development of enhanced promoters, supports, and experimental conditions have been attempted. For example, bulk Fe is favorable for methane formation; however, olefin and long-chain hydrocarbon production can be enhanced with the addition of promoters (i.e., alkaline promoters). Potassium, as an electronic promoter, can regulate the phase proportion of Fe0/FeOx/FeCx to maintain an optimum balance. The dissociative adsorption of *CO can be improved, while surface *H is decreased by donated electrons to the vacant d-orbital of Fe. The resulting higher C/H ratio favors chain growth and chain termination by forming unsaturated hydrocarbons118. Thus, a very important challenge is to increase the surface C/H ratio. Competitive adsorption between H2 and CO occurs on the catalyst surface. The partial pressure of CO is always limited due the difficulty of converting CO2 via the RWGS reaction. Since a high C/H ratio is desired to form unsaturated hydrocarbons, a possible strategy would be to enhance CO2 activation and CO adsorption, while weakening H2 adsorption101. In addition, the H2 ratio in the feed gas should also be carefully chosen. To achieve good results from FTS-based CO2 hydrogenation, more consideration is needed based on the characteristics of those reactions instead of imitation of the CO hydrogenation process.

To increase selectivity to light olefins, further hydrogenation must be suppressed. Thus, synergy between the promoter and the support is suggested. For example, an Al2O3 support can interact with a K promoter to form a KAlO2 phase under calcination temperatures above 500 °C, which has been shown to suppress further hydrogenation of olefins77. To increase the synergistic effect, the active metal can be mixed with supports. A series of K-modified supports (activated carbon, TiO2, ZrO2, SBA-15, B-ZSM-5, and Al2O3) were physically mixed with Fe5C2 and tested for direct hydrogenation of CO2. The Fe5C2–10 K/α-Al2O3 catalyst converted 40.9% of CO2 with a selectivity of 73.5% to C2+ products, containing 37.3% C2–C4= and 31.1% C5+119. A promising support for Fe-based catalysts is MOF-derived carbon materials. Some researchers have recently developed methods of using MOFs to fabricate carbon supported Fe-based catalysts83,120. Two Fe-MOF-derived catalysts have been reported for CO2 hydrogenation, with high stability and selectivity to light olefins and liquid fuels120,121. However, the challenge of separating light olefins from unreacted CO2 and H2 remains. Increasingly advanced techniques and materials are required for their separation.

The second, set of challenges are production of C5+ products. These challenges are similar to those for the synthesis of light olefins, due to the shared fundamental reaction mechanism. The selectivity of C5+ products is also comparable to that of light olefins synthesis (Table 1, Entries 22–31). CO2 hydrogenation to C5+ products consist of multiple steps, including the RWGS reaction, C–C coupling, and acid-catalyzed reactions (oligomerization, isomerization, or aromatization). Therefore, cooperation between steps is required to develop an efficient and multifunctional catalyst. As zeolites are often used to incorporate the active sites, they generally undergo deactivation as a result of coke deposition. For example, the selectivity of isoparaffins over a Na–Fe3O4/HMCM-22 catalyst was reduced from ~60 to ~30% and the total acidity of HMCM-22 decreased from 0.200 to 0.032 mmolpyridine gcat−1 after 12 h of reaction time, which was attributed to coke formation and accumulation in the cavities and channels92. Thus, a big challenge for the synthesis of C5+ products is to reduce coke deposition in the zeolites and to enhance the catalyst stability. As heavier hydrocarbons contain many components, it is difficult to precisely control a specific type of product. Zeolites with different framework topologies are suggested to regulate product distribution. In addition, in contrast to the CO-based FTS process, the reaction is fed with stable CO2 molecules; therefore, the reformation of CO2 from the produced CO via the WGS reaction is a thermodynamically favorable process, which limits CO2 conversion17,122. One method to decrease the reformation of CO2 from CO is to develop better multifunctional catalysts by employing appropriate promoters to facilitate the formation of iron carbide, which is known as the active catalyst for heavy hydrocarbon formation in FTS96, and to enhance the chemisorption and dissociation of CO2123. Also, by cycling reactants, CO2 conversion is increased. Therefore, finding suitable multifunctional catalyst combinations or promoters and optimizing the reactors should be an attractive area of research in the future. Dual-promoter systems are usually designed to improve the RWGS reaction activity, while increasing FTS activity and C5+ selectivity. Finally, there is a significant gap between the quality of synthesized liquid fuels and commercial gasoline. The octane number would be enhanced by developing catalysts that increase the fraction of isoparaffins in the gasoline.

Finally, the challenges to produce higher alcohols are considered. For higher alcohols synthesis, the major obstacles are the formation and insertion of the hydroxyl group during the C–C coupling process in the presence of parallel reactions. This is made even more challenging since the formation pathways are different over Fe- and Co-based catalysts and the mechanisms are controversial. On K/Fe/N-functionalized CNT catalysts, alcohol synthesis was explained by the reaction between hydrocarbon species, such as alkylidenes (R-CH2-CH = ), and *OH, which forms from the dissociation of adsorbed CO (*CO) and H2 (*H)73. *CO was hypothesized to react with *CH3 species to form *CH3CO, which was then hydrogenated to form CH3CH2OH on a Na-Co/SiO2 catalyst. To increase the yield of higher alcohols, efficient Co-based catalysts with more stable cobalt carbide (Co-Co2C) interfaces and/or Co-M alloy nanocrystals should be developed. Co2C is responsible for CO adsorption on the surface, whereas the Co metal is useful for CO dissociation and subsequent carbon-chain growth124. The synthesis of higher alcohols requires precise coordination between C–C coupling and OH formation, otherwise, more methanol or long-chain hydrocarbons would be produced. Also, the synergy of high metal dispersion and a high-density of hydroxyl groups on the supports can promote the selectivity to ethanol because the hydroxyls are able to stabilize formate species and protonate methanol18. The work from Fan’s group also indicates that metal oxyhydroxides, such as FeOOH125, TiO(OH)21, and ZrO(OH)2126 can accelerate the CO2 sorption and desorption processes, thus reducing the energy required for CO2 capture based on experimental and DFT calculations. These metal oxyhydroxides are likely catalyst candidates because they contain hydroxyl groups that should enhance CO2 hydrogenation to higher alcohols.

Transformational technologies for catalyst development

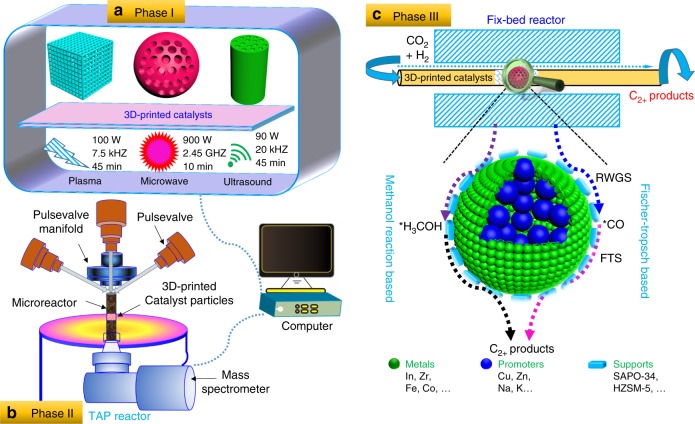

Revolutionary material manufacturing, characterization, and evaluation technologies emerging in the new century may be instrumental for hydrogenating CO2 to high-value products. However, these technologies are only beginning to be explored for their application to CO2 hydrogenation. Thus, this perspective endeavors to fill in critical blanks. The keys are to discover alternative catalysts, modify current catalysts for CO2 activation, develop methods to prepare specialized catalysts on a large-scale, and intelligently evaluate catalysts. Guided by reaction theories and the associated heterogeneous catalytic CO2 hydrogenation experimental results, the feasibility of transformational technologies in three phases of CO2 hydrogenation will be explored: catalyst preparation and modification, characterization, and AI-guided evaluation (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Scheme of AI-guided development of CO2 hydrogenation catalysts.

Phase I is to prepare and modify catalysts using 3D printing technologies and new material modification technologies, such as plasma, microwave, and ultrasound modification135,137,138. Phase II is to use advanced techniques to characterize the catalysts. Phase III is to perform AI-guided evaluation of the catalysts.

Phase I is CO2 hydrogenation catalyst preparation and modification. Conventional labor-intensive lab-based CO2 hydrogenation catalyst preparation may be replaced by low-cost 3D-printing approaches to include characteristics of high mechanical strength and surface-to-volume ratio, with precise control of porosity, size, and shape127. The development of 3D-printed catalysts with designable and tunable structures is appealing and potentially useful for catalyst synthesis on a large scale. Although green 3D-printing has been utilized in preparing highly active, reusable, and stable catalysts for CO2 removal, methane combustion, methanol to olefins conversion, syngas methanation, and N-aryl compound synthesis128–131, it has not been used for CO2 hydrogenation or CO2 conversion catalysts to date. Also, most of the printed catalysts are millimeter- to micrometer-sized materials, while nano- or atomic-sized catalysts are still challenging to print by existing 3D printing technology. As the functional components of active CO2 hydrogenation catalysts are further studied (e.g., metals, promoters, and supports), more effort can be devoted to incorporating them into a fully integrated platform with diverse microstructures by 3D printing. As different spatial arrangements in bifunctional catalysts influence catalytic performance, 3D printing can assemble the components with multiple structures in their preferred configuration. Therefore, 3D printing provides an alternative approach for preparation of novel CO2 hydrogenation catalysts, especially for synthesizing bifunctional catalysts. Realizing that AI has proven to be a great tool in a range of fields, including materials discovery and design132, the authors intend to apply a pioneering outlook with its application to CO2 hydrogenation catalyst preparation, especially in combination with 3D printing technology. The 3D printing strategy already has advantages in potential scale-up manufacturing of catalysts, and AI technology would accelerate its application. AI-assisted 3D printing technologies can open new possibilities for the large-scale conversion of CO2.

Also, new material modification technologies, such as microwave, ultrasound, and plasma treatments, have been suggested to modify catalysts for CO2 activation, especially if the particle sizes or metal dispersion are affected by the 3D printing technologies. The utilization of unconventional modification tools in catalyst preparation and treatment can improve active phase dispersion to obtain a more uniform morphology with smaller particle sizes compared to the untreated catalysts133–135. Smaller particle size would enhance specific surface area and the exposed active sites available. The catalyst mechanical strength and the average basic site strength for CO2 adsorption can be increased by microwave irradiation treatment, due to its better heat transfer133. Catalysts synthesized with the assistance of ultrasound, microwave, or plasma treatments have been employed in CO2 hydrogenation and CO2/CH4 reforming reactions134,136. These unconventional methods need high frequency and input power with reduced processing time135,137,138. In addition, the reactor can be constructed with plasma or microwave enhancement. The CO2-to-CH3OH reaction was accomplished in a plasma reactor without heating or adding pressure, generating a CH3OH selectivity of 53.7% and a CO2 conversion of 21.2% over a Cu/γ-Al2O3 catalyst136. Coupling of plasma and catalyst lowered the kinetic barrier and energy cost associated with conventional high temperature and high pressure processing. Therefore, the use of these new modification technologies before or after 3D printing can possibly remedy defects introduced by 3D printing technologies.

Phase II is to characterize the CO2 hydrogenation catalysts. New material characterization technologies, including in situ scanning transmission electron microscopy and temporal analysis of product reactors, coupled with qualitative and/or quantitative species identification, such as gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, are suggested for characterization of the catalysts prepared with state-of-the-art and transformational technologies. To date, in situ CO2-temperature programmed surface reaction and diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy have been applied widely to elucidate how CO2 molecules dynamically interact with the catalyst. However, other characterization methods for heterogeneous catalysts under in situ conditions are challenging due to the lack of experimental facilities. Therefore, in the future, AI-assisted CO2 hydrogenation catalyst characterizations are needed. Machine learning especially can bring advanced computational techniques to the forefront of characterization of heterogeneous catalysts. For example, machine learning can be used to help interpret experimental spectra. Although the imaging and spectroscopic results are complicated, it would be helpful to design new catalysts and link models and experiments by connecting these results to structure–function information139. Timoshenko et al.140 have successfully deciphered the 3D geometric structure of supported Pt NPs with the use of X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectroscopy and supervised machine learning. They solved the structures and reconstructed the morphology of Pt NPs just from the experimental XANES data using an artificial neural network. Therefore, theoretical simulations can assist in obtaining more spectra and deconvoluting the structural characterization.

Phase III is to perform AI-guided evaluation of CO2 hydrogenation catalysts. The prospect of using AI for identification of reaction intermediates and pathways and establishing kinetic models would be promising. First, the AI-guided method is expected to predict catalytic performance and to discover promising catalyst candidates. AI-based catalyst evaluation might largely help predict and improve catalyst stability, which however will require more significant effort. Zahrt et al.141 pointed out that machine learning has the potential to change the way chemists select and optimize catalysts. Some examples of recent results in AI-based catalyst evaluation follow. The hydrocarbon selectivities for DME conversion can be accurately predicted by an AI model with an R2 greater than 0.98 compared to experimental results142. Several known and unknown electrocatalysts for CO2 reduction and hydrogen evolution were identified from 1499 intermetallics by machine learning27. Specifically, 258 candidate surfaces among 102 alloys have been identified from 23,141 adsorption sites for the H2 evolution reaction.

Currently, it is inconvenient to characterize catalyst structures in situ during stability tests. Thus, in situ monitoring of the catalyst structure dynamics and transformation by AI would be beneficial. Second, we need more automatic, integrated, and flexible set-ups to evaluate catalysts. Third, data analysis could be performed and kinetic models evaluated with the help of AI. Numerous experimental data for CO2 hydrogenation have been generated and this existing data should be reanalyzed. Kitchin suggests that machine learning can be applied to build models with more sophisticated methods143, generating new relevant data and calculated properties. Furthermore, it is crucial to identify reaction intermediates and pathways by AI. A simple syngas reaction on Rh(111) exhibits more than 2000 potential pathways144, in comparison with the more complicated CO2 hydrogenation reaction routes that are strongly influenced by the various active centers. Hence, it is necessary to analyze the reaction mechanism by employing machine learning and DFT calculations.

Finally, predicting relationships among the characteristics of the catalysts, such as Lewis acidity, CO2 conversion efficiency, and product selectivity, with AI based on the available experimental data and DFT computation results will be helpful for discussing structure–function relationships and accelerating the discovery of catalytic mechanisms. Although AI offers many promising applications in CO2 hydrogenation, robust and versatile AI is still in a primitive stage. A difficulty for AI development comes from the slowly developing applications of big data and a convenient language or software. Li et al.28 pointed out that it is crucial and challenging to build additional criteria for screening and synthesizing catalysts, to quantify the uncertainties of machine-learning models, and to develop fingerprints of more sophisticated active sites with targeted functionalities. Also, more data for machine learning are required, including all reactions related to CO2, such as FTS, CO2/CH4 reforming, and CO2 hydrogenation. In conclusion, the collaborative efforts from experts and scientists in catalysis and materials design, machine-learning practitioners, and algorithm developers all over the world are needed to promote its development.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the China Scholarship Council (File no. 201704910592), the “Strategic Priority Research Program” of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA21020800), and University of Wyoming.

Author contributions

R.Y., J.D., and W.G. were responsible for preparing the whole paper; R.Y., J.D., W.G., and Q.L. contributed to the figure designing and drawing as well as comparisons of different types of reaction mechanisms; M.A. and C.R. contributed to the understanding of the intermediate formation and catalysis mechanisms involved in the paper; Q.Z., Y.W., Z.X., A.R. contributed to the understanding of the effects of catalyst structure on CO2 conversion and product selectivity, M.F. and Y.Y. are the initiators, designers, and leaders of the work.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Run-Ping Ye, Jie Ding, Weibo Gong.

Contributor Information

Maohong Fan, Email: mfan@uwyo.edu.

Yuan-Gen Yao, Email: mfan@uwyo.edu.

References

- 1.Lai Q, et al. Catalyst-TiO(OH)2 could drastically reduce the energy consumption of CO2 capture. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2672. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05145-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cui S, et al. Mesoporous amine-modified SiO2 aerogel: a potential CO2 sorbent. Energ. Environ. Sci. 2011;4:2070–2074. doi: 10.1039/c0ee00442a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richard AR, Fan M. Low-pressure hydrogenation of CO2 to CH3OH using Ni-In-Al/SiO2 catalyst synthesized via a phyllosilicate precursor. ACS Catal. 2017;7:5679–5692. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.7b00848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogelj J, et al. Paris agreement climate proposals need a boost to keep warming well below 2 °C. Nature. 2016;534:631–639. doi: 10.1038/nature18307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis SJ, Caldeira K, Matthews HD. Future CO2 emissions and climate change from existing energy infrastructure. Science. 2010;329:1330–1333. doi: 10.1126/science.1188566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin F, et al. High-yield reduction of carbon dioxide into formic acid by zero-valent metal/metal oxideredox cycles. Energ. Environ. Sci. 2011;4:881–884. doi: 10.1039/c0ee00661k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun Y, et al. In situ hydrogenation of CO2 by Al/Fe and Zn/Cu alloy catalysts under mild conditions. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2019;42:1223–1231. doi: 10.1002/ceat.201800389. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyu L, Zeng X, Yun J, Wei F, Jin F. No catalyst addition and highly efficient dissociation of H2O for the reduction of CO2 to formic acid with Mn. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48:6003–6009. doi: 10.1021/es405210d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhong H, et al. Selective conversion of carbon dioxide into methane with a 98% yield on an in situ formed Ni nanoparticle catalyst in water. Chem. Eng. J. 2019;357:421–427. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2018.09.155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang Y, et al. Synergetic conversion of microalgae and CO2 into value-added chemicals under hydrothermal conditions. Green Chem. 2019;21:1247–1252. doi: 10.1039/C8GC03645D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, et al. Exploring the ternary interactions in Cu-ZnO-ZrO2 catalysts for efficient CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1166. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09072-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan Y, Dai YH, He H, Yu YB, Yang YH. A novel W-doped Ni-Mg mixed oxide catalyst for CO2 methanation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2016;196:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2016.05.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kothandaraman J, Goeppert A, Czaun M, Olah GA, Prakash GK. Conversion of CO2 from air into methanol using a polyamine and a homogeneous ruthenium catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:778–781. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b12354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roy S, Cherevotan A, Peter SC. Thermochemical CO2 hydrogenation to single carbon products: Scientific and technological challenges. ACS Energy Lett. 2018;3:1938–1966. doi: 10.1021/acsenergylett.8b00740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saravanan K, Ham H, Tsubaki N, Bae JW. Recent progress for direct synthesis of dimethyl ether from syngas on the heterogeneous bifunctional hybrid catalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017;217:494–522. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.05.085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Z, et al. Highly selective conversion of carbon dioxide to lower olefins. ACS Catal. 2017;7:8544–8548. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.7b03251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei J, et al. Directly converting CO2 into a gasoline fuel. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15174–15181. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang C, et al. Hydroxyl-mediated ethanol selectivity of CO2 hydrogenation. Chem. Sci. 2019;10:3161–3167. doi: 10.1039/C8SC05608K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu J, Huang Y, Ye W, Li Y. CO2 reduction: from the electrochemical to photochemical approach. Adv. Sci. 2017;4:1700194. doi: 10.1002/advs.201700194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prieto G. Carbon dioxide hydrogenation into higher hydrocarbons and oxygenates: thermodynamic and kinetic bounds and progress with heterogeneousand homogeneous catalysis. ChemSusChem. 2017;10:1056–1070. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201601591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang W, Wang S, Ma X, Gong J. Recent advances in catalytic hydrogenation of carbon dioxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:3703–3727. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15008a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alvarez A, et al. Challenges in the greener production of formates/formic acid, methanol, and DME by heterogeneously catalyzed CO2 hydrogenation processes. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:9804–9838. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olah GA, Mathew T, Prakash GK. Chemical formation of methanol and hydrocarbon ("Organic") derivatives from CO2 and H2-carbon sources for subsequent biological cell evolution and life's origin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:566–570. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b10230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jia J, et al. Heterogeneous catalytic hydrogenation of CO2 by metal oxides: defect engineering-perfecting imperfection. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017;46:4631–4644. doi: 10.1039/C7CS00026J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kattel S, Liu P, Chen JG. Turning selectivity of CO2 hydrogenation reactions at the metal/oxide interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:9739–9754. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b05362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao P, et al. Direct conversion of CO2 into liquid fuels with high selectivity over a bifunctional catalyst. Nat. Chem. 2017;9:1019–1024. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tran K, Ulissi ZW. Active learning across intermetallics to guide discovery of electrocatalysts for CO2 reduction and H2 evolution. Nat. Catal. 2018;1:696–703. doi: 10.1038/s41929-018-0142-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Z, Wang S, Xin H. Toward artificial intelligence in catalysis. Nat. Catal. 2018;1:641–642. doi: 10.1038/s41929-018-0150-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parra-Cabrera C, Achille C, Kuhn S, Ameloot R. 3D printing in chemical engineering and catalytic technology: structured catalysts, mixers and reactors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018;47:209–230. doi: 10.1039/C7CS00631D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samson K, et al. Influence of ZrO2 structure and copper electronic state on activity of Cu/ZrO2 catalysts in methanol synthesis from CO2. ACS Catal. 2014;4:3730–3741. doi: 10.1021/cs500979c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rui N, et al. CO2 hydrogenation to methanol over Pd/In2O3: effects of Pd and oxygen vacancy. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017;218:488–497. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.06.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kattel S, Ramírez PJ, Chen JG, Rodriguez JA, Liu P. Active sites for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol on Cu/ZnO catalysts. Science. 2017;355:1296–1299. doi: 10.1126/science.aal3573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Behrens M, et al. The active site of methanol synthesis over Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 industrial catalysts. Science. 2012;336:893–897. doi: 10.1126/science.1219831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bansode A, Urakawa A. Towards full one-pass conversion of carbon dioxide to methanol and methanol-derived products. J. Catal. 2014;309:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jcat.2013.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rungtaweevoranit B, et al. Copper nanocrystals encapsulated in Zr-based metal-organic frameworks for highly selective CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Nano Lett. 2016;16:7645–7649. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b03637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.An B, et al. Confinement of ultrasmall Cu/ZnOx nanoparticles in metal-organic frameworks for selective methanol synthesis from catalytic hydrogenation of CO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:3834–3840. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b00058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lam E, et al. Isolated Zr surface sites on silica promote hydrogenation of CO2 to CH3OH in supported Cu catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:10530–10535. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b05595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larmier K, et al. CO2-to-methanol hydrogenation on Zirconia-supported copper nanoparticles: Reaction intermediates and the role of the metal-support interface. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:2318–2323. doi: 10.1002/anie.201610166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun, K. H. et al. Hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol over In2O3 catalyst. J. CO2Util.12, 1–6 (2015).

- 40.Martin O, et al. Indium oxide as a superior catalyst for methanol synthesis by CO2 hydrogenation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:6261–6265. doi: 10.1002/anie.201600943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li H, et al. Synergetic interaction between neighbouring platinum monomers in CO2 hydrogenation. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018;13:411–417. doi: 10.1038/s41565-018-0089-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nie X, et al. Mechanistic understanding of alloy effect and water promotion for Pd-Cu bimetallic catalysts in CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. ACS Catal. 2018;8:4873–4892. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.7b04150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yin Y, et al. Pd@zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 derived PdZn alloy catalysts for efficient hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018;234:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.04.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Studt F, et al. Discovery of a Ni-Ga catalyst for carbon dioxide reduction to methanol. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:320–324. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fiordaliso EM, et al. Intermetallic GaPd2 nanoparticles on SiO2 for low-pressure CO2 hydrogenation to methanol: catalytic performance and in situ characterization. ACS Catal. 2015;5:5827–5836. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.5b01271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang X, et al. Low pressure CO2 hydrogenation to methanol over gold nanoparticles activated on a CeOx/TiO2 interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:10104–10107. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Toyao T, Kayamori S, Maeno Z, Siddiki SMAH, Shimizu K-i. Heterogeneous Pt and MoOx Co-loaded TiO2 catalysts for low-temperature CO2 hydrogenation to form CH3OH. ACS Catal. 2019;9:8187–8196. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.9b01225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Richard AR, Fan M. The effect of lanthanide promoters on NiInAl/SiO2 catalyst for methanol synthesis. Fuel. 2018;222:513–522. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2018.02.185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ham H, Baek SW, Shin C-H, Bae JW. Roles of structural promoters for direct CO2 hydrogenation to dimethyl ether over ordered mesoporous bifunctional Cu/M–Al2O3 (M = Ga or Zn) ACS Catal. 2018;9:679–690. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b04060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang G, Tsubaki N, Shamoto J, Yoneyama Y, Zhang Y. Confinement effect and synergistic function of H-ZSM-5/Cu-ZnO-Al2O3 capsule catalyst for one-step controlled synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:8129–8136. doi: 10.1021/ja101882a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Phienluphon R, et al. Designing core (Cu/ZnO/Al2O3)–shell (SAPO-11) zeolite capsule catalyst with a facile physical way for dimethyl ether direct synthesis from syngas. Chem. Eng. J. 2015;270:605–611. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2015.02.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dang S, et al. Role of zirconium in direct CO2 hydrogenation to lower olefins on oxide/zeolite bifunctional catalysts. J. Catal. 2018;364:382–393. doi: 10.1016/j.jcat.2018.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gao J, Jia C, Liu B. Direct and selective hydrogenation of CO2 to ethylene and propene by bifunctional catalysts. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2017;7:5602–5607. doi: 10.1039/C7CY01549F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao P, et al. Direct production of lower olefins from CO2 conversion via bifunctional catalysis. ACS Catal. 2018;8:571–578. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.7b02649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu X, et al. Selective transformation of carbon dioxide into lower olefins with a bifunctional catalyst composed of ZnGa2O4 and SAPO-34. Chem. Commun. 2018;54:140–143. doi: 10.1039/C7CC08642C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen J, et al. Hydrogenation of CO2 to light olefins on CuZnZr@(Zn-)SAPO-34 catalysts: Strategy for product distribution. Fuel. 2019;239:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2018.10.148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ni Y, et al. Selective conversion of CO2 and H2 into aromatics. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3457. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05880-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jiao F, et al. Selective conversion of syngas to light olefins. Science. 2016;351:1065–1068. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu X, et al. Effective and highly selective CO generation from CO2 using a polycrystalline α-Mo2C catalyst. ACS Catal. 2017;7:4323–4335. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.7b00735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Posada-Perez S, et al. Highly activeAu/δ-MoC and Cu/δ-MoC catalysts for the conversion of CO2: The metal/C ratio as a key factor defining activity, selectivity, and stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:8269–8278. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b04529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ma Z, Porosoff MD. Development of tandem catalysts for CO2 hydrogenation to olefins. ACS Catal. 2019;9:2639–2656. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b05060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhao, B., Liu, Y., Zhu, Z., Guo, H. & Ma, X. Highly selective conversion of CO2 into ethanol on Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalyst with the assistance of plasma. J. CO2Util.24, 34–39 (2018).

- 63.Kattel S, et al. CO2 hydrogenation over oxide-supported PtCo catalysts: the role of the oxide support in determining the product selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:7968–7973. doi: 10.1002/anie.201601661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tsoukalou A, et al. Structural evolution and dynamics of an In2O3 Catalyst for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol: an operando XAS-XRD and in situ TEM study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:13497–13505. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b04873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu L, et al. Mechanistic study of Pd–Cu bimetallic catalysts for methanol synthesis from CO2 hydrogenation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2017;121:26287–26299. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b06166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ye J, Liu C, Mei D, Ge Q. Active oxygen vacancy site for methanol synthesis from CO2 hydrogenation on In2O3(110): a DFT study. ACS Catal. 2013;3:1296–1306. doi: 10.1021/cs400132a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tang Q, Shen Z, Russell CK, Fan M. Thermodynamic and kinetic study on carbon dioxide hydrogenation to methanol over a Ga3Ni5(111) surface: the effects of step edge. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2018;122:315–330. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b08232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Martínez-Suárez L, Siemer N, Frenzel J, Marx D. Reaction network of methanol synthesis over Cu/ZnO nanocatalysts. ACS Catal. 2015;5:4201–4218. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.5b00442. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Olsbye U, et al. Conversion of methanol to hydrocarbons: how zeolite cavity and pore size controls product selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:5810–5831. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shi J, Wang Y, Yang W, Tang Y, Xie Z. Recent advances of pore system construction in zeolite-catalyzed chemical industry processes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:8877–8903. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00626K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li Z, et al. Highly selective conversion of carbon dioxide to aromatics over tandem catalysts. Joule. 2019;3:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.joule.2018.12.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Numpilai T, Wattanakit C, Chareonpanich M, Limtrakul J, Witoon T. Optimization of synthesis condition for CO2 hydrogenation to light olefins over In2O3 admixed with SAPO-34. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019;180:511–523. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2018.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kangvansura P, et al. Product distribution of CO2 hydrogenation by K- and Mn-promoted Fe catalysts supported on N -functionalized carbon nanotubes. Catal. Today. 2016;275:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cattod.2016.02.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chew LM, et al. Effect of nitrogen doping on the reducibility, activity and selectivity of carbon nanotube-supported iron catalysts applied in CO2 hydrogenation. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2014;482:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.apcata.2014.05.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kattel S, Liu P, Chen JG. Tuning selectivity of CO2 hydrogenation reactions at the metal/oxide interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:9739–9754. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b05362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]