Introduction

Drug-induced ototoxicity imposes significant functional and socioeconomic challenges for individuals who experience lifelong hearing loss as sequelae of treatment for conditions such as sepsis, especially in neonates (1,2); multi-drug resistant tuberculosis, particularly in developing countries (3,4); lung infections in the setting of cystic fibrosis (5,6); and cancers treated with platinum-based chemotherapies (7,8). Indeed, the very conditions these drugs are used to treat may actually enhance the risk of sustaining life-long hearing loss as a side effect of treatment. This clinical paradox poses a difficult situation for the treating physician. While these therapies are effective treatments, life-long hearing loss can have significant negative impacts on long-term quality of life. These adverse effects can be of particular challenge in neonatal/pediatric patients, for whom early hearing loss can delay language acquisition and subsequently impact education and social attainment (9).

Endotoxemia, as a model for gram-negative sepsis, enhances the risk and severity of drug-induced hearing loss in mice after treatment with ototoxic drugs such as cisplatin (10), aminoglycosides such as kanamycin (11), and synergistic combination of kanamycin/furosemide (12). In neonatal intensive care unit patients, meeting criteria for systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) (13,14) (Table S1) in the setting of suspected bacterial sepsis increases the risk-ratio of sustaining life-long hearing loss after empirical gentamicin therapy (15). A previous study demonstrated that endotoxemia-enhanced aminoglycoside ototoxicity is tied to increased aminoglycoside trafficking at the BLB (11). Furthermore, endotoxemia-enhanced BLB trafficking is mechanistically tied to TLR4 activity as C3H/HeJ mice, with a hypomorphic Tlr4 gene variant, did not exhibit enhanced BLB trafficking during endotoxemia (11). TLR4 is a potent immune sensor, promoting innate inflammation in response to pathogen and damage associated molecular patterns (PAMPs and DAMPS) such as LPS, which is a commonly used experimental TLR4 agonist. Binding of LPS to TLR4 induces release and production of innate pro-inflammatory signals, which orchestrate downstream inflammatory effector cell activity (16,17). Thus, immune cells may mechanistically contribute to endotoxemia-enhanced BLB trafficking.

Neutrophils are the most abundant white blood cell and are first responders to innate inflammatory cues, including LPS-endotoxemia induced SIRS. Neutrophil-mediated vascular injury is a long appreciated pathological vascular change that occurs during sepsis (including SIRS) and is a result of intravascular neutrophil release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs or NETosis) (18–20). Because neutrophil-mediated vascular injury is elicited by neutrophil activity downstream of TLR4, we tested the hypothesis that knockdown of neutrophil numbers would rescue endotoxemia-enhanced BLB trafficking, similar to that observed in Tlr4-KO hypomorphic C3H/HeJ mice (11). To test this hypothesis, we investigated BLB pathophysiology and the relative contributions of TLR4 signaling and downstream neutrophil activity during endotoxemia in Tlr4-KO mice (reduced Tlr4 signaling) and G-csf-KO neutropenic mice (reduced neutrophils). Our results demonstrate that both TLR4 mediated cytokine/chemokine signaling and downstream neutrophil activity are both required for endotoxemia-enhanced BLB trafficking.

Methods

Experimental animals

Animals were bred in-house by OHSU staff. C57BL/6 and Tlr4-KO (B6(Cg)-Tlr4tm1.2Karp/J) founder mice were procured from Jackson Lab. G-csf-KO (B6.129X1(Cg-Csf3rtm1Link/J) founder mice were generously provided by Dr. Jason Shohet. Both mutant strains have a C57BL/6 background. Both male and female mice were used at ages 16–20 weeks with weights ranging from 18–30 g. Animals were housed in gender-separated boxes in groups of between 3–6 mice. Animals were allowed free access to food and water and kept under a twelve-hour light/dark cycle.

Lipopolysaccharide solution preparation

LPS (Millipore-Sigma, Cat# L3012) was dissolved in 0.05% endotoxin-free bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Equitech Bio, Cat# BAH70–0050) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a concentration of 2.0 mg/ml. LPS and vehicle solutions were filter-sterilized into sterile vacuum tubes using a 0.05 μm polypropylene filter and kept on ice during use on the same day.

Endotoxemia induction and tissue collections

Mice were lightly anesthetized using ketamine/xylazine “half-strength mouse cocktail” (100 mg/kg ketamine, 5 mg/kg xylazine in saline; 5 μl/g i.p.). Once adequate sedation was achieved, animals were treated with sterile LPS (10mg/kg, 2 mg/ml; 5 μl/g i.v. via tal-vein) or vehicle 0.5% endotoxin-free BSA in PBS (5 μl/g i.v.) solutions. Twenty-four hours later mice were re-anesthetized with “full-strength mouse cocktail” (100 mg/kg ketamine, 10 mg/kg xylazine in saline; 5 μl/g i.p.) and once adequate sedation had been reached, mice were perfused with 10 ml room-temperature PBS.

qRT-PCR analysis

Temporal bones from PBS-perfused mice were placed in RNA preservative (RNAlater, Millipore-Sigma, Cat# R0901) and their cochleas dissected. Excess RNAlater was removed and tissues were pooled into samples of four cochleas from two mice, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. RNA was isolated from samples of pooled cochleas (four cochleas from two mice) using an RNeasy kit and concentrated via Speed Vac on low heat. RNA concentration and quality was determined using a NanoDrop 2000 series spectrophotometer (ThermoFischer Scientific, ND2000). RNA from each sample (150 ng) was utilized for reverse-transcription cDNA synthesis via TaqMan RT-reagents (Applied Biosystems, Cat# N8080234). 5ng of cDNA was used for each TaqMan primer/probe qRT-PCR reaction in a 96-well format using TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Cat# 4369016). Samples were run in duplicate on a AB7300 (Applied Biosystems) plate reader over 60 PCR cycles. Cycle threshold (Ct) values were exported to Excel and delta-delta Ct (ddCt) analysis was hand-calculated using 18S as the housekeeping gene for delta Ct (dCt) calculation (21). Each experimental group had an n=3–7 (6–14 mice) depending upon the number of animals available; a small minority of samples were excluded due to low RNA yield.

Biocytin-TMR vascular tracer treatment

Biocytin-TMR (Setareh Biotech, Cat# 6662) in PBS (1% (m/m), 5 ul/g, i.v.) was administered to mice 23.25 hours after LPS treatment and allowed to circulate for 45 minutes prior to euthanasia.

Cochlear Ly6G immunohistochemistry and Biocytin-TMR counter labeling

Following intracardiac perfusion of 10 ml room-temperature PBS, mice were perfused with 10 ml of room-temperature 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. Cochleas were dissected and fixed for 24 hours in 4% PFA. Cochleas were decalcified in 10% EDTA in Tris-buffered saline pH 7.4 for 7 days, then sectioned at 50 μm with a vibratome (22). Tissues were washed in PBS, then blocked with 0.5% Triton X-100 and 5% donkey serum in PBS for 1 hour, followed by incubation with primary antibody in blocking solution overnight at 4 °C (Ly6G, 1A8 clone BioLegend cat# ab154885; 2.5 μg/ml). Sections were washed 3× in PBS, then incubated with secondary antibody in blocking solution overnight (Donkey Anti-Rat IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor 647) preadsorbed; abcam cat# ab150155, 0.5 μg/ml). Sections were washed 3×1 hour in PBS followed by treatment with Streptavidin Alexa Fluor 568 (ThermoFisher, Cat# S11226) at 10 μg/ml in PBS with 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.1 mM CaCl2, and 10% donkey serum for 1 hour. Tissues were washed 2×1 hour in PBS with 0.2% Triton X-100 and incubated overnight with Hoescht (1 ug/ml) and Lycopersicon Esculentum lectin-488 (Vector cat# DL-1174; 200 μg/ml) in PBS. Next, sections were washed 2×1 hour with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS, washed 1×1 hour with PBS, post-fixed in 4% PFA for 15 minutes then washed 3×20 minutes in PBS, then mounted on slides with Vectashield mounting medium.

Confocal microscopy

Four-color z-stacks of cochlear sections were collected at 20× magnification on a Zeiss LSM 880 laser-scanning confocal microscope with an inverted microscope base and Airyscan capabilities for faster image acquisition. Three cochlear sections were imaged for each individual mouse. The microscope laser power and detector settings for the biocytin-TMR channel was calibrated to the brightest slide.

Biocytin-TMR vascular tracer and neutrophil quantification

Confocal image stacks were analyzed using Fiji. Red channel z-stacks of cochlear sections were combined into maximum intensity projections and regions of interest were hand drawn (Fig. 4a). Mean pixel intensities for each region of interest were averaged over three cochlear sections for each individual n and used for cohort-level statistical analysis.

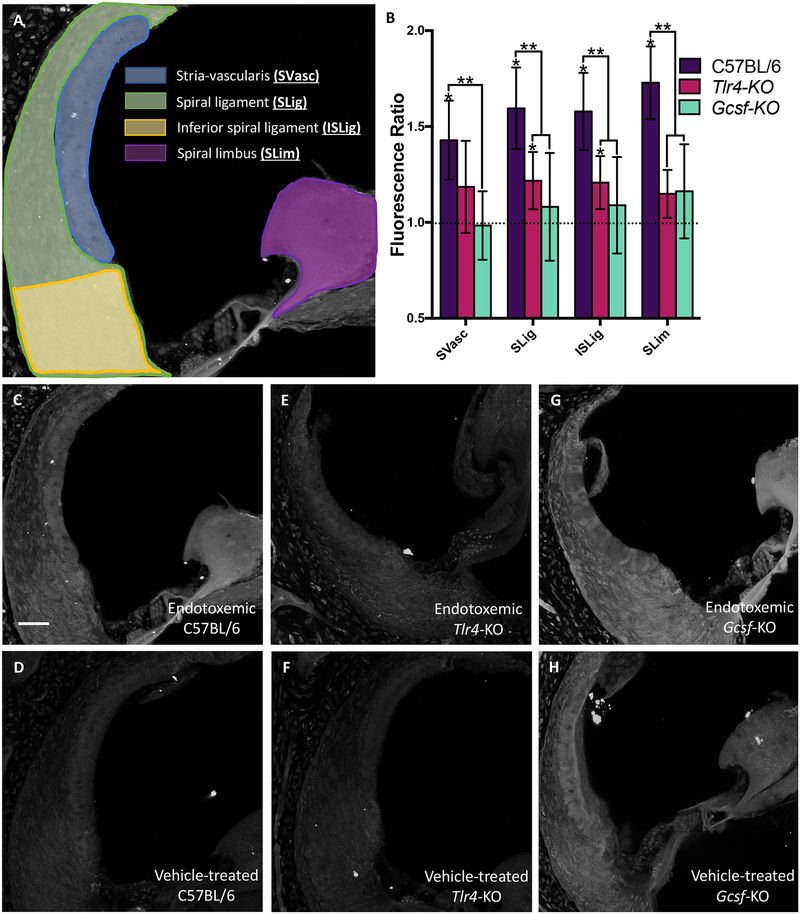

Fig. 4. Biocytin-TMR vascular tracer quantification during endotoxemia.

Mice were treated with either 10 mg/kg LPS i.v. or vehicle and 24 hours later with 1% biocytin-TMR. Cochleas were imaged via quantitative confocal microscopy. (A) Regions of interest were hand-drawn in Fiji and each anatomical region quantified (B) for C57BL/6, Tlr4-KO and Gcsf-KO mice (n=3–5 per cohort). 95% student’s-t confidence intervals. * p<0.05 for LPS treatment normalized to vehicle treatment within a mouse strain. ** p<0.05 between indicated mouse strains. SVasc = stria vascularis, SLig = spiral ligament, ISLig = inferior spiral ligament, SLim = spiral limbus (C-H) Representative cochlear sections of mice treated with biocytin-TMR and counter-labeled with Streptavidin Alexa Fluor 568. Strain and treatment are indicated in each panel. Raw data is presented in Fig S2. White error bar is 50 μm.

To assess total cochlear neutrophil load, all neutrophils were counted in cochlear sections from all anatomical regions. Neutrophils from three randomly selected mid-cochlear selected slices from each animal were quantified and averaged for an individual n and used for cohort-level statistical analysis. n = 3–5 as indicated by each data point on Fig 3; the n depended upon the number of available animals Averages for each animal were individually plotted and p values calculated using a non-parametric t-test. Fluorescent objects near the surface of the slice that were not cellular in appearance were not counted as neutrophils.

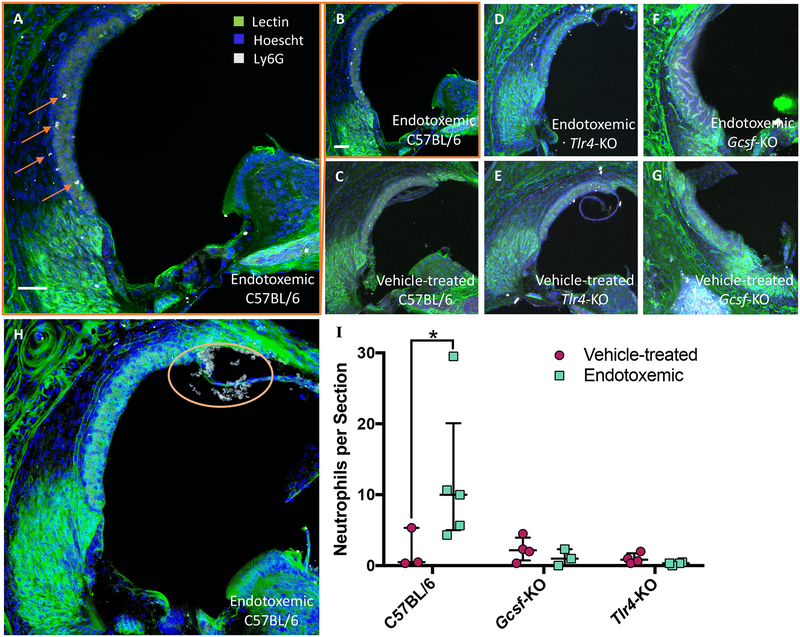

Fig. 3. Endotoxemia recruits’ neutrophils to wild-type but not Tlr4-KO or Gcsf-KO mice.

(A-H) Representative cochlear sections of mice treated with either 10 mg/kg LPS or vehicle and labeled with Ly6G neutrophil marker (white), a lectin to label blood vessels (green), and Hoescht for nuclei (blue); mouse strain and treatment indicated on panel. (A) Larger representation of panel B. (H) A severe case of cochlear neutrophilic infiltration marked with orange circle. (I) Quantification of cochlear neutrophils. Each data point is one individual averaged over three cochlear sections. White scale bars are 50 μm. Error bars are median with interquartile range. * indicates p<0.05 for one-tailed Mann-Whitney U test.

Statistics

Graphpad Prism v7.0a was used to calculate statistical tests as indicated in each Fig. legend. For ratiometric analyses (Fig. 4 and Fig S1) 95% confidence intervals were hand-calculated in Excel and graphs plotted using Prism.

Study Approval

All protocols and procedures were approved by our intuitional animal care and use committee.

Results

Tlr4-KO but not G-csf-KO dampens cochlear innate immune marker transcription

Tlr4 mutant C3H/HeJ mice demonstrate reduction in endotoxemia-enhanced aminoglycoside uptake and concomitant reduced innate immune marker expression (11). Because neutrophil activity is downstream of Tlr4 activity, we assessed cochlear transcription of innate immune cytokines and chemokines in Tlr4-KO and G-csf-KO mice. Mice were treated with high dose LPS (10 mg/kg i.v.); the LD50 is somewhere between 12.5–60 mg/kg depending on dosing, LPS-type/purity, and route of administration (23–26) to model a high-morbidity/mortality gram-negative sepsis situation indicating aminoglycoside therapy i.e. the sickest of sick patients. Additionally, high dose LPS was chosen to model clinical situations where a patient is most at risk for experiencing long term aminoglycoside side effects, such as lifelong hearing loss.

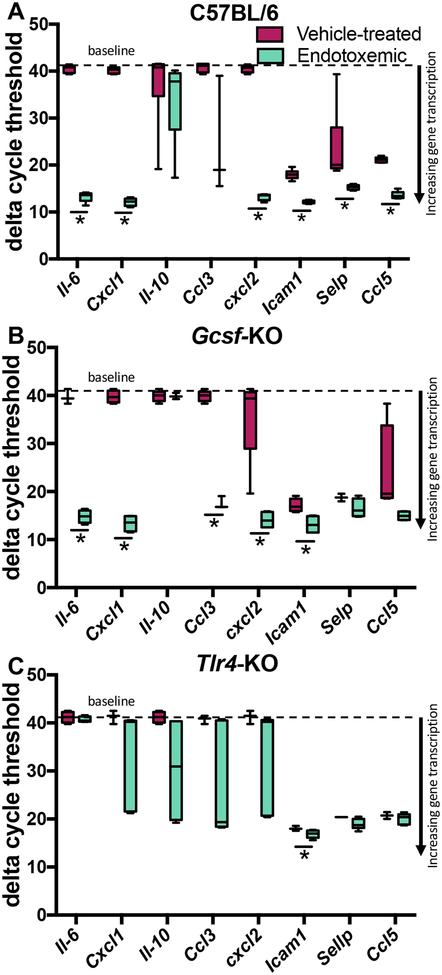

After twenty-four hours of endotoxemia, cochleas were collected for qRT-PCR analysis of innate immune system pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine transcripts (Fig. 1, Table S2). The twenty-four hour time point was selected based on previous studies that demonstrate a window of endotoxemia-enhanced BLB trafficking (11,12,27). Wild-type C57BL/6 mice served as the positive control, as endotoxemia induces cochlear transcription of innate immune markers (11,28). Endotoxemia upregulated the transcription of a majority of these innate immunity markers, as demonstrated by decreased dCt values for most genes analyzed with the exception of Il-10 and Ccl3 (Fig. 2A).

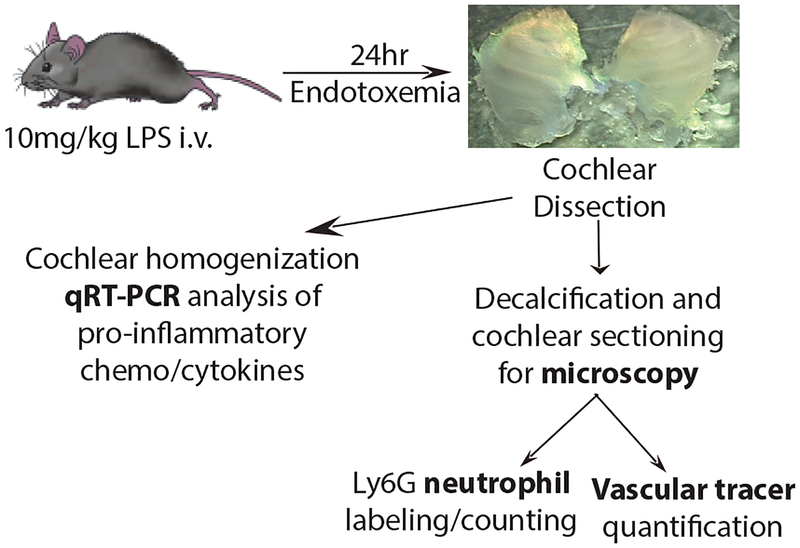

Fig. 1. Study Design.

Mice were treated with 10mg/kg LPS i.v. and cochleas collected 24 hours later for qRT-PCR analysis, neutrophil counts, and vascular tracer quantification.

Fig. 2. Cochlear innate immunity gene transcription in endotoxemic vs vehicle-treated C57BL/6, Tlr4-KO, and Gcsf-KO mice.

Mice were treated with 10 mg/kg LPS i.v. and cochleas collected 24 hours later for qRT-PCR analysis. Delta cycle threshold (dCt) values normalized to 18S are presented; lower dCt corresponds to greater gene expression. (A) dCt values for endotoxemic vs vehicle-treated wild-type C57BL/6, (B) neutropenic Gcsf-KO, (C), and LPS-hyporesponsive Tlr4-KO mice. (n=3–7 per cohort). Box and whisker plots. * indicates p<0.05 after student’s t-test.

Neutropenic G-csf-KO mice, which have wild-type Tlr4, demonstrated a qualitatively similar transcript profile as compared to wild-type mice. All genes analyzed were upregulated; with the exceptions of Il-10, Selp, and Ccl5 (Fig. 2B). By contrast, transcription of pro-inflammatory markers in Tlr4-KO mice were not upregulated with the exception of a very small, yet statistically significant, dCt difference in Icam1 (Fig. 2C).

Baseline gene transcription was similar between strains (Fig. S1A). Two exceptions were Cxcl2 upregulation in G-csf-KO mice and Selp upregulation in both Tlr4-KO and G-csf-KO strains.

Endotoxemia recruits’ neutrophils to the BLB of wild-type but not Tlr4-KO or G-csf-KO mice

TLR4-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine/chemokine activity promotes innate immune cell activity and associated neutrophil-mediated vascular injury. Because of this we used the neutrophil-specific marker Ly6G to investigate the presence of neutrophils in cochlear sections of C57BL/6, Tlr4-KO, and G-csf-KO mice treated with 10 mg/kg LPS or vehicle. Because Tlr4-KO mice do not express LPS-induced pro-inflammatory genes (Fig. 2C), we hypothesized that few neutrophils would be recruited to carry out LPS-mediated cochlear inflammation. G-csf-KO mice are neutropenic and the sparse neutrophils in these animals are anergic and underdeveloped (29); we therefore hypothesized that few neutrophils would be recruited to the cochleas of these mice.

A varied number but statistically significant number of neutrophils appeared in endotoxemic C57BL/6 wild-type mice (Fig. 3A–B, 3H) compared to vehicle treated mice (Fig. 3C). This was in contrast to the small number of neutrophils in cochlear sections of both endotoxemic and vehicle-treated Tlr4-KO mice (Fig. 3D–E), which exhibit diminished pro-inflammatory signaling, and G-csf-KO mice (Fig. 3F–G) which have greatly reduced numbers of neutrophils. Diminished neutrophil recruitment is consistent with the attenuated pro-inflammatory gene expression profile in Tlr4-KO and chronic neutropenia in G-csf-KO mice. The observed variance in the observed neutrophil number per animal could be due to a number of reasons; some possible reasons include counting neutrophils in sections and the inherent random sampling of this method, the time point chosen is on the up- or down-slope of peak neutrophil activity, individual health status of each mouse prior to LPS treatment (although the mice were all grossly healthy by physical exam prior to LPS treatment).

Endotoxemia enhances BLB biocytin-TMR trafficking in C57BL/6 mice and is rescued in Tlr4-KO and G-csf-KO mice

Endotoxemia and local LPS treatment, as well as other innate immune reaction provoking stimuli, compromise endothelial barriers, including the blood-brain barrier, the blood-retinal barrier, and the BLB (27,30,31) which could be due to neutrophil-mediated vascular injury. Analogously, neutropenia decreases drug uptake in the lungs of pneumonitic mice (32). Since Tlr4-KO and G-csf-KO mice express differential patterns of innate immune pro-inflammatory markers (Fig. 2) and neutrophil recruitment (Fig. 3), we tested the hypothesis that both Tlr4 and neutrophil activity are required to enhance vascular trafficking at the BLB. To test this hypothesis, we treated endotoxemic and vehicle-treated C57BL/6, Tlr4-KO, and G-csf-KO mice with the paracellular vascular tracer biocytin-TMR (33) and quantified parenchymal uptake via confocal microscopy (Fig. 4, Fig. S2).

Endotoxemia increased the normalized biocytin-TMR fluorescence intensity ratios in all ROIs (Fig. 4A) in C57BL/6 mice, but not in Tlr4-KO or G-csf-KO mice with the exception of the spiral ligament regions in the Tlr4-KO strain (Fig. 4B). Analysis of the absolute fluorescence levels also demonstrated that biocytin-TMR uptake was increased in cochleas of C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 4C–D, Fig. S2A) but not in Tlr4-KO mice (Fig. 4E–F, Fig. S2B) or G-csf-KO mice (Fig. 4G–H, Fig. S2C), with the exception of the spiral limbus region in G-csf-KO mice (Fig. S2C). The baseline fluorescence intensity was also compared between strains. C57BL/6 and Tlr4-KO strains had comparable baseline biocytin-TMR uptake, while G-CSF-KO mice demonstrated increased baseline uptake of biocytin-TMR in all ROIs (Fig. S2D).

Discussion

We set out to determine if Tlr4-mediated cytokine/chemokine signaling is sufficient or whether downstream neutrophil activity is also required for endotoxemia-enhanced BLB trafficking. Endotoxemic neutropenic G-csf-KO mice exhibit robust enhancement of cochlear pro-inflammatory innate immune gene transcription similar to wild-type C57BL/6 mice (10,28). This response was greatly attenuated in LPS-hyporesponsive Tlr4-KO mice, similar to observations with the Tlr4 hypomorphic C3H/HeJ mouse strain (11). C57BL/6 and G-csf-KO mice both harbor wild-type Tlr4 genes, whereas Tlr4-KO mice do not. Therefore, this observation confirms that the genes studied here are TLR4 dependent. Still, the cochlear pro-inflammatory marker response to endotoxemia was not completely null in Tlr4-KO mice. Although TLR4 is the canonical and most potent LPS sensor, there is evidence for other (minor and less potent) LPS sensors. For example, the non-canonical inflammasome is activated by intracellular LPS-mediated dimerization of caspase-11 via LPS endocytosis and subsequent interaction with the NLRP3 inflammasome (26); in addition, there is controversial evidence that LPS is a partial agonist of TLR2 (34–36).

Innate immune pro-inflammatory markers selected for the qRT-PCR panel are endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecules, cytokines, and chemokines, that are stimulated via convergent and redundant TLR-signaling, which orchestrate downstream immune effector cells such as neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages (Table S2) promoting neutrophil-mediated vascular injury. Therefore, we wanted to assess the numbers of Ly6G+ neutrophils in cochlear sections of endotoxemic vs vehicle-treated mice in C57BL/6, Tlr4-KO, and G-csf-KO mice. Endotoxemic wild-type C57BL/6 mouse cochlear sections demonstrated the most Ly6G+ neutrophils. In both Tlr4-KO and G-csf-KO strains, neutrophils were rarely observed in cochlear sections of endotoxemic mice. In vehicle-treated mice, neutrophils were also very rarely observed in all three mouse strains. C57BL/6 mice with a wild-type immune system and robust transcription of innate immune chemokines/cytokines neutrophils would be expected to show an increase in neutrophil numbers and activity after LPS challenge. In Tlr4-KO mice with greatly dampened innate immune cytokine/chemokine signaling, neutrophils have fewer cues directing them to carry out immune functions and incur neutrophil mediated vascular injury. G-csf-KO mice are congenitally neutropenic and their greatly reduced neutrophil numbers, with an immature phenotype diminishes endotoxemia-mediated neutrophil recruitment.

To assess the relative contributions of inflammatory signaling and downstream neutrophil activity to endotoxemia-enhanced BLB trafficking, we quantified cochlear biocytin-TMR distribution in endotoxemic relative to vehicle-treated C57BL/6, Tlr4-KO, and G-csf-KO mice. This demonstrated enhanced biocytin-TMR trafficking in the stria vascularis, spiral ligament, and interestingly in the spiral limbus region of C57BL/6 wild-type mice. In Tlr4-KO mice, enhanced BLB trafficking was not significantly enhanced in either the stria vascularis or the spiral limbus region although there was very small statistically significant increase in biocytin-TMR trafficking in the spiral ligament region. In G-csf-KO mice, endotoxemia-enhanced trafficking of biocytin-TMR returned to baseline levels in all cochlear regions examined. G-csf-KO mice demonstrated significantly increased baseline cochlear uptake of biocytin-TMR. A possible explanation for the difference in baseline biocytin-TMR uptake, is the difference in baseline transcription levels of inflammatory markers (Fig. S1B), and in particular Cxcl2. Presumably, other related pro-inflammatory markers not measured in the current study are also upregulated; enhanced baseline expression of these cytokines and chemokines could be sufficient to cause endothelial cell-independent enhanced baseline trafficking activities at the BLB in G-csf-KO mice.

This study was limited by the use of only one vascular tracer. Endothelial transport mechanisms other than paracellular trafficking are almost certainly involved. Our gene panel is also limited to a subset of genes specific to the converging TLR and inflammasome mediated innate inflammatory response; however, they do not examine other aspects of an inflammatory reaction such as adaptive immunity. Other leukocyte markers besides Ly6G could also expand the scope of this study on cochlear leukocyte activity including macrophage and adaptive immune system cell markers to investigate the full complement of immune cell activity during endotoxemia.

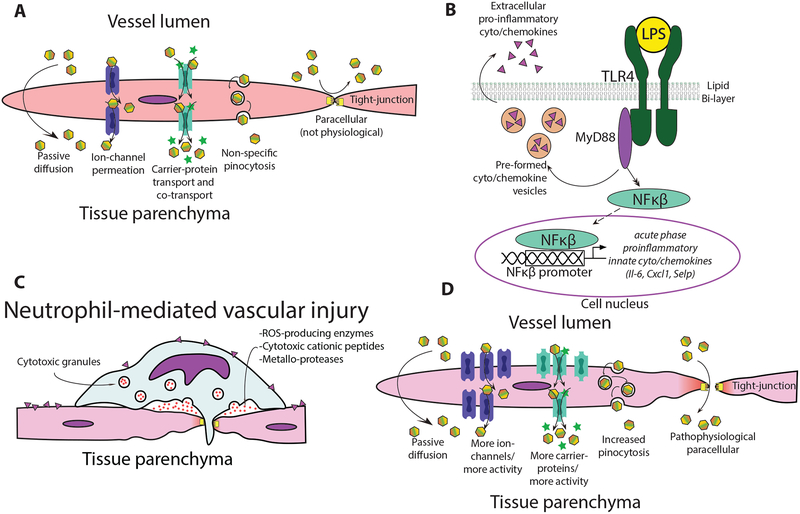

A pathophysiological hallmark of SIRS and sepsis is perturbed endothelial barrier properties causing capillary leak syndrome (37), for which endotoxemia is a classic model system (38); neutrophil-mediated vascular injury is a significant contributor to capillary leak (39–43). At baseline, the primary endothelial transport mechanisms are passive diffusion, ion-channel permeation, carrier-mediated transport, and pinocytosis; paracellular BLB trafficking is not a major mechanism under physiological conditions (Fig. 5A). Within minutes to hours LPS-mediated activation of TLR4 induces cytokine/chemokine transcription (Fig. 5B) enhancing transcellular BLB trafficking in an endothelial-cell independent manner (33). These transcellular mechanisms include increased ion-channel permeation through channels such as TRP-channels (44,45), enhanced carrier-mediated transport via molecules such as SGLT2 (46), and non-specific pinocytosis/transcytosis. Initial enhanced transcellular trafficking activities are believed to enhance immune globulin uptake into tissue parenchyma where they can mount an immune response (47–49). Concurrently, endothelial barriers increase the expression of leukocyte adhesion molecules such as P-SELECTIN (50) and ICAM1 (51,52) promoting leukocyte adhesion, neutrophil-mediated vascular injury, and diapedesis leading to paracellular trafficking (27,31) routes (hours later) not present under healthy physiological states (Fig. 5C) (33,50,53). Enhanced BLB trafficking at early time points is likely most reliant on increased transcellular trafficking mechanisms (pino/transcytosis, ion-channel, and specific transporters) with paracellular theoretically becoming more apparent at later time points after neutrophil-mediated vascular injury accumulation (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5. Model for endotoxemia-enhanced BLB trafficking.

(A) Baseline BLB trafficking mechanisms. Paracellular trafficking is largely absent during healthy physiological states. (B) Endotoxemia stimulates TLR4 signaling inducing cytokine/chemokine expression (C) Chemokine/cytokine activated neutrophils and other white blood cells adhere to activated endothelium and degranulate causing neutrophil-mediated vascular injury. (D) Possible endotoxemia-induced pathophysiological trafficking routes emerge in injured vasculature allowing enhanced cochlear ototoxic drug uptake.

Endotoxemia diminishes the endolymphatic potential (EP) (12) and enhances perilymph uptake of the vascular tracer fluorescein (27). Less is known about endolymph uptake of vascular tracers as sampling rodent endolymph is difficult although some indirect methods suggest endolymph as an important aminoglycoside trafficking route (54,55). Diminished EP suggests diminished cell-cell coupling both at BLB vessels, and the epithelial marginal cells lining the scala-media immediately adjacent to cochlear vasculature. Furthermore, decreased EP means reduced electrogenic potential energy barrier for trafficking of polycations such as aminoglycosides into endolymph. Neutrophil granule-derived NETs contain proteases such as matrix-metalloproteinases which directly degrade tight-junction proteins (56,57), and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generating enzymes that non-specifically damage host-tissues, generating DAMPs (58). Rescue of endotoxemia-enhanced biocytin-TMR trafficking by genetic deletion of neutrophils (G-csf-KO) suggests directly that knocking down neutrophil activity, and associated NET release (59), diminishes paracellular trafficking into cochlear parenchyma.

Recent findings in the context of cisplatin ototoxcicity suggests cisplatin remains in the stria vascularis indefinitely after exposure, and that hair cell loss is secondary to BLB dysfunction rather than direct hair cell toxicity (60). Therapeutic strategies to prevent drug-induced hearing loss therefore should focus on protecting BLB function. Pharmacological efforts could target both transcellular uptake as well as neutrophil-mediated vascular injury, blocking subsequent paracellular disruption. Transcellular strategies could include non-specific cation channel blockers expressed at the BLB if such a druggable candidate is identified, or local cochlear administration of agents that reduce pinocytosis. Interestingly, anti-inflammatory treatments (such as aspirin (61–64)) and anti-ROS thiol-based therapies such as D-methionine (65–68) have demonstrated efficacy in both pre-clinical and clinical studies of sepsis (69), aminoglycoside and cisplatin ototoxicity (70–74). Because ROS-dampening thiol-based therapies work in the isolated contexts of sepsis, and ototoxic drugs, there is likely overlap in the mechanisms of each pathology. Indeed, sepsis, and aminoglycoside/cisplatin ototoxicity involve ROS. Where exactly cochlear ROS are generated is unknown. ROS could derive from leukocytes recruited by DAMPs released by necrotic cochlear cells, and/or directly from stressed cochlear cells. This study suggests that neutrophil-mediated vascular injury, which involves ROS-mediated cell damage, is an important contributor to endotoxemia-enhanced BLB trafficking.

Understanding the mechanisms leading to drug-induced hearing loss may lead to either patient management strategies and/or pharmacological strategies to protect hearing during ototoxic therapies. This study suggests neutropenia may protect a patients’ hearing functionality during ototoxic antibacterial therapy or chemotherapy. Furthermore, targeting neutrophil activity such as ROS-generating neutrophil-derived NET-associated enzymes could be a promising pharmacological strategy to ameliorate drug-induced hearing loss.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

Jason Shohet for our colony founding G-csf-KO mice. Leonard Rybak, Peter Barr-Gillespie, and Daniel Marks for critical reading and editing of this manuscript. Peter Steyger for his role in help in developing the concepts motivating this study and for sponsoring the affiliated F30 and American Otological Society fellowships. Oregon Health and Science University’s Advanced Light Microscopy Core for guidance and resources for confocal microscopy data analysis. Funding: NIH/NIDCD F30DC014229–01A1, (ZDU) American Otological Society Fellowship (ZDU). NINDS P30 NS061800 imaging core grant (Sue Aicher). National Cancer Institute grant CA199111 to EAN.

References

- 1.Skorup P, Maudsdotter L, Lipcsey M et al. Beneficial antimicrobial effect of the addition of an aminoglycoside to a beta-lactam antibiotic in an E. coli porcine intensive care severe sepsis model. PLoS One 2014;9:e90441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuchs A, Zimmermann L, Bickle Graz M et al. Gentamicin exposure and sensorineural hearing loss in preterm infants. PLoS One 2016;11:e0158806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Altena R, Dijkstra JA, van der Meer ME et al. Reduced chance of hearing loss associated with therapeutic drug monitoring of aminoglycosides in the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017;61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pietersen E, Peter J, Streicher E et al. High frequency of resistance, lack of clinical benefit, and poor outcomes in capreomycin treated South African patients with extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0123655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Malky G, Dawson SJ, Sirimanna T et al. High-frequency audiometry reveals high prevalence of aminoglycoside ototoxicity in children with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2015;14:248–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Handelsman JA, Nasr SZ, Pitts C et al. Prevalence of hearing and vestibular loss in cystic fibrosis patients exposed to aminoglycosides. Pediatr Pulmonol 2017;52:1157–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greene JB, Standring R, Siddiqui F et al. Incidence of cisplatin induced ototoxicity in adults with head and neck cancer. Advances in Otolaryngology 2015;2015:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brinkman TM, Bass JK, Li Z et al. Treatment-induced hearing loss and adult social outcomes in survivors of childhood CNS and non-CNS solid tumors: Results from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Cancer 2015;121:4053–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirk KI, Miyamoto RT, Lento CL et al. Effects of age at implantation in young children. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology 2002;111:69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oh GS, Kim HJ, Choi JH et al. Activation of lipopolysaccharide-TLR4 signaling accelerates the ototoxic potential of cisplatin in mice. Journal of Immunology 2011;186:1140–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koo JW, Quintanilla-Dieck L, Jiang M et al. Endotoxemia-mediated inflammation potentiates aminoglycoside-induced ototoxicity. Science Translational Medicine 2015;7:298ra118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirose K, Li SZ, Ohlemiller KK et al. Systemic lipopolysaccharide induces cochlear inflammation and exacerbates the synergistic ototoxicity of kanamycin and furosemide. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology 2014;15:555–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldstein B, Giroir B, Randolph A. International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 2005;6:2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Chest 1992;101:1644–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cross CP, Liao S, Urdang ZD et al. Effect of sepsis and systemic inflammatory response syndrome on neonatal hearing screening outcomes following gentamicin exposure. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 2015;79:1915–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I et al. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in TLR4 gene. Science 1998;282:2085–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arbour NC, Lorenz E, Schutte BC et al. TLR4 mutations are associated with endotoxin hyporesponsiveness in humans. Nature Genetics 2000;25:187–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harlan JM. Neutrophil mediated vascular injury. Acta Medica Scandinavica 1987;221:123–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harlan JM, Killen PD, Harker LA et al. Neutrophil-mediated endothelial injury in vitro. Journal of Clinical Inves 1981;68:1394–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meegan JE, Yang X, Coleman DC et al. Neutrophil-mediated vascular barrier injury: Role of neutrophil extracellular traps. Microcirculation 2017;24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001;25:402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shim K Vibratome sectioning for enhanced preservation of the cytoarchitecture of the mammalian organ of Corti. Journal of Visualized Experiments 2011;52:e2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Musson RA, Morrison DC, Ulevitch RJ. Distribution of endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide) in the tissues of lipopolysaccharide-responsive and -unresponsive mice. Infection and Immunity 1978;21:448–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berczi I, Bertok L, Bereznai T. Comparative studies on the toxicity of escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide endotoxin in various animal models. Canadian Journal of Microbiology 1966;12:1070–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Remick DG, Newcomb DE, Bolgos GL et al. Comparison of the mortality and inflammatory response of two models of sepsis: lipopolysaccharide vs. cecal ligation and puncture. Shock 2000;13:110–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kayagaki N, Wong MT, Stowe IB et al. Noncanonical inflammasome activation by intracellular LPS independent of TLR4. Science 2013;341:1246–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirose K, Hartsock JJ, Johnson S et al. Systemic lipopolysaccharide compromises the blood-labyrinth barrier and increases entry of serum fluorescein into the perilymph. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 2014;15:707–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quintanilla-Dieck L, Larrain B, Trune D et al. Effect of systemic lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation on cytokine levels in the murine cochlea: a pilot study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;149:301–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richards MK, Liu F, Iwasaki H et al. Pivotal role of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in the development of progenitors in the common myeloid pathway. Blood 2003;102:3562–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Banks WA, Gray AM, Erickson MA et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced blood-brain barrier disruption: roles of cyclooxygenase, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and elements of the neurovascular unit. J Neuroinflammation 2015;12:223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J, Chen S, Hou Z et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced middle ear inflammation disrupts the cochlear intra-strial fluid-blood barrier through down-regulation of tight junction proteins. PLoS One 2015;10:e0122572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garraffo R, Roptin C, Boudjadja A. Impact of neutropenia on tissue penetration of moxifloxacin and sparfloxacin in infected mice. Drugs 1999;58:242–5. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knowland D, Arac A, Sekiguchi K et al. Stepwise recruitment of transcellular and paracellular pathways underlies blood-brain barrier breakdown in stroke. Neuron 2014;82:603–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirschning CJ, Wesche H, Ayres MT et al. Human toll-like recepter 2 confers responsiveness to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Journal of Experimental Medicine 1998;188:2091–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang RB, Mark MR, Gray A et al. Toll-like receptor-2 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced cellular signaling. Nature 1998;395:284–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirschfeld M, Ma Y, Weis JH et al. Cutting Edge: repurification of lipopolysaccharide eliminates signaling through both Human and murine toll-like receptor 2. The Journal of Immunology 2000;165:618–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siddall E, Khatri M, Radhakrishnan J. Capillary leak syndrome: etiologies, pathophysiology, and management. Kidney Int 2017;92:37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Deventer SJ, Buller HR, ten Cate JW et al. Experimental endotoxemia in humans: analysis of cytokine release and coagulation, fibrinolytic, and compliment pathways. Blood 1990;76:2520–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yi ES, Ulich TR. Endotoxin, interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor cause neutrophil-dependent microvascular leakage in postcapillary venules. American Journal of Pathology 1992;140:650–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guidot DM, Repine MJ, Hybertson BM et al. Inhaled nitric oxide prevents neutrophil-mediated, oxygen radical-dependent leak in isolated rat lungs. American Journal of Physiology - Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology 1995;269:L2–L5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Conner WC, Gallagher CM, Miner TJ et al. Neutrophil priming state predicts capillary leak after gut ischemia in rats. Journal of Surgical Research 1999;84:24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Standiford TJ, Kunkel SL, Lukacs NW et al. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha mediates lunk leukocyte recruitment, lung capillary leak, and early mortality in murine endotoxemia. The Journal of Immunology 1995;155:1515–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fishel RS, Are C, Barbul A. Vessel injury and capillary leak. Crit Care Med 2003;31:S502–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marcotti W, van Netten SM, Kros CJ. The aminoglycoside antibiotic dihydrostreptomycin rapidly enters mouse outer hair cells through the mechano-electrical transducer channels. J Physiol 2005;567:505–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alharazneh A, Luk L, Huth M et al. Functional hair cell mechanotransducer channels are required for aminoglycoside ototoxicity. PLoS One 2011;6:e22347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiang M, Wang Q, Karasawa T et al. Sodium-glucose transporter-2 (SGLT2; SLC5A2) enhances cellular uptake of aminoglycosides. PLoS One 2014;9:e108941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Almeida CJ, Witkiewicz AK, Jasmin JF et al. Caveolin-2-deficient mice show increased sensitivity to endotoxemia. Cell Cycle 2011;10:2151–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Garrean S, Gao XP, Brovkovych V et al. Caveolin-1 regulates NF-kB activation and lung inflammatory response to sepsis induced by lipopolysaccharide. The Journal of Immunology 2006;177:4853–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tiruppathi C, Shimizu J, Miyawaki-Shimizu K et al. Role of NF-kappaB-dependent caveolin-1 expression in the mechanism of increased endothelial permeability induced by lipopolysaccharide. The Journal of biological chemistry 2008;283:4210–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang B, Ling Y, Lin J et al. Force-dependent calcium signaling and its pathway of human neutrophils on P-selectin in flow. Protein Cell 2017;8:103–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gujral JS, Liu J, Farhood A et al. Functional importance of ICAM-1 in the mechanism of neutrophil-induced liver injury in bile duct-ligated mice. American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 2004;286:G499–G507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simon SI, Hu Y, Vestweber D et al. Neutrophil tethering on E-selectin activates integrin binding to ICAM-1 through a mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway. The Journal of Immunology 2000;164:4348–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Henson VE. Normal cochlear lateral wall permeability to fluorescent macromolecules Program in Audiology and Communication Sciences: University of Washington; St. Louis, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li H, Steyger PS. Systemic aminoglycosides are trafficked via endolymph into cochlear hair cells. Scientific Reports 2011;1:159–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dai CF, Steyger PS. A systemic gentamicin pathway across the stria vascularis. Hearing Research 2008;235:114–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vandenbroucke RE, Dejonckheere E, Van Lint P et al. Matrix metalloprotease 8-dependent extracellular matrix cleavage at the blood-CSF barrier contributes to lethality during systemic inflammatory diseases. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2012;32:9805–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Choi CH, Jang CH, Cho YB et al. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor attenuates cochlear lateral wall damage induced by intratympanic instillation of endotoxin. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2012;76:544–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McColl BW, Rothwell NJ, Allan SM. Systemic inflammation alters the kinetics of cerebrovascular tight junction disruption after experimental stroke in mice. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2008;28:9451–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Allen C, Thornton P, Denes A et al. Neutrophil cerebrovascular transmigration triggers rapid neurotoxicity through release of proteases associated with decondensed DNA. J Immunol 2012;189:381–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Breglio AM, Rusheen AE, Shide E Det al. Cisplatin is retained in the cochlea indefinitely following chemotherapy. Nature Communications 2017;8:1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Behnoud F, Davoudpur K, Goodarzi MT. Can aspirin protect or at least attenuate gentamicin ototoxicity in humans? Saudi Medical Journal 2009;30:1165–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sha SH, Qiu JH, Schacht J. Aspirin to prevent gentamicin-induced hearing loss. New England Journal of Medicine 2006;354:1856–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sha SH, Schacht J. Salicylate attenuates gentamicin-induced ototoxicity. Laboratory Investigations 1999;79:807–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen Y, Huang WG, Zha DJ et al. Aspirin attenuates gentamicin ototoxicity: from the laboratory to the clinic. Hearing Research 2007;226:178–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bernard GR, Lucht WD, Niedermeyer ME et al. Effect of N-acetylcysteine on the pulmonary response to endotoxin in the awake sheep and upon in vitro granulocyte function. Journal of Clinical Investigation 1984;73:1772–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Feldman L, Sherman RA, Weissgarten J. N-acetylcysteine use for amelioration of aminoglycoside-induced ototoxicity in dialysis patients. Seminars Dialysis 2012;25:491–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fox DJ, Cooper MD, Speil CA et al. d-Methionine reduces tobramycin-induced ototoxicity without antimicrobial interference in animal models. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 2015;15:518–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Campbell KC, Meech RP, Rybak LP et al. D-Methionine protects against cisplatin damage to the stria vascularis. Hearing Res 1999;138:13–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hsu BG, Lee RP, Yang FL et al. Post-treatment with N-acetylcysteine ameliorates endotoxin shock-induced organ damage in conscious rats. Life Sci 2006;79:2010–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dickey DT, Wu YJ, Muldoon LL et al. Protection against cisplatin-induced toxicities by N-acetylcysteine and sodium thiosulfate as assessed at the molecular, cellular, and in vivo levels. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2005;314:1052–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Doolittle ND, Muldoon LL, Brummett REet al. Delayed sodium thiosulfate as an otoprotectant against carboplatin-induced hearing loss in patients with malignant brain tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2001;7:493–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Freyer DR. The effects of sodium thiosulfate (STS) on cisplatin-induced hearing loss: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:5s (suppl; abstr 10017). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Muldoon LL, Pagel MA, Kroll RA et al. Delayed administration of sodium thiosulfate in animal models reduces platinum ototoxicity without reduction of antitumor activity. Clin Can Res 2000;6:309–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Neuwelt EA, Brummett RE, Remsen LG et al. In vitro and animal studies of sodium thiosulfate as a potential chemoprotectant against carboplatin-induced ototoxicity. Cancer Res 1996;56:706–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.