Abstract

Objective:

Patellofemoral (PF) alignment and trochlear morphology are associated with PF osteoarthritis (OA) and knee pain, however it is unknown whether they are associated with localized anterior knee pain (AKP), which is believed to be a symptom specific to PF joint pathology. We therefore aimed to evaluate the relation of PF alignment and morphology, as well as PFOA and tibiofemoral OA, to AKP.

Methods:

The Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study (MOST) is a cohort study of individuals with, or at risk for, knee OA. We evaluated cross-sectional associations of PF alignment, trochlear morphology, and PF and tibiofemoral radiographic OA, with localized AKP (defined with a pain map). We used two approaches: a within-person knee-matched evaluation of participants with unilateral AKP (conditional logistic regression); and a cohort approach comparing those with AKP to those without (binomial regression).

Results:

With the within-person knee-matched approach (n=110, 64% women, mean age 70, BMI 30.9), PF alignment, morphology, and tibiofemoral OA were not associated with unilateral AKP. Radiographic PFOA was associated with pain, odds ratio 5.3 (95% CI 1.6, 18.3). Using the cohort approach (n=1818, 7% of knees with AKP, 59% women, age 68, BMI 30.4), results were similar: only PFOA was associated with pain, prevalence ratio 2.2 (1.4, 3.4).

Conclusion:

PF alignment and trochlear morphology were not associated with anterior knee pain in individuals with, or at risk for, knee OA. Radiographic PFOA, however, was associated with pain, suggesting features of OA, more so than mechanical features, may contribute to localized symptoms.

Keywords: patellofemoral osteoarthritis, knee osteoarthritis, pain, alignment, morphology

Radiographic patellofemoral osteoarthritis (OA) is present in approximately 25% of individuals derived from population-based samples, and approximately 39% of individuals who report knee pain (1). Importantly, a common sequence of development of knee OA begins at the patellofemoral joint, with subsequent progression to multi-compartment knee OA (2–4). In order to develop more effective interventions for treating knee OA in general, it is critical to identify factors that contribute to patellofemoral OA and OA-related pain. Pain ultimately drives patients to seek medical care. Patellofemoral joint pathology (such as patellar malalignment or structural damage) is believed to be specifically associated with anterior knee pain (5). However, this has not been explicitly evaluated in individuals with, or at high risk for having, knee OA.

Patellofemoral alignment (the position of the patella relative to the distal femur) and trochlear bony morphology (the geometric shape of the trochlear groove) are associated with patellofemoral OA as well as to knee pain (6, 7). This association with knee pain justifies further investigation as to whether patellofemoral alignment and morphology are associated with localized anterior knee pain in particular; this may offer insight into the mechanisms driving patellofemoral pain and OA. For example, a laterally displaced patella could cause anterior knee pain as a result of a localised increase in joint stress in the lateral patellofemoral compartment, and this increased joint stress could lead to structural damage. This theory would also suggest, then, that patellofemoral joint structural damage may also be associated with anterior knee pain.

A key challenge in OA-related pain research is that the pain experience is complex and multifactorial. Pain may be caused by mechanical factors (7), but also by inflammatory factors (8), central sensitization (9) and psychosocial factors (10). There are also unknown or unmeasurable factors that contribute to the pain experience. As a result, successfully identifying pain determinants can be challenging using traditional research methods.

To minimize confounding by factors that may differ between individuals, an approach used in studying the relation of structural severity of tibiofemoral OA to knee pain involved evaluation of both knees in individuals with unilateral knee pain (i.e., pain in one knee and no pain in the contralateral knee) (11). This method removes the effect of person-level characteristics that may contribute to pain (e.g., BMI, sex, psychosocial profile, genetics, etc.) that could otherwise explain pain variability among people. Using this method, it was demonstrated in two large knee OA cohorts that knee pain was strongly associated with radiographic tibiofemoral OA (11). Similar approaches have since been used to better understand various knee-specific determinants of pain in knee OA (12, 13), and would be well-suited to evaluating joint-level determinants of anterior knee pain.

We aimed to evaluate the relation of patellofemoral alignment and morphology to anterior knee pain. We hypothesized that, with anterior knee pain, the patella would be more laterally displaced, laterally tilted, and proximally displaced, and the trochlea would be shallower and wider, compared to knees without pain. Our secondary aim was to evaluate the relation of radiographic patellofemoral and tibiofemoral OA to anterior knee pain. We hypothesized that patellofemoral OA would be more strongly associated with anterior knee pain than tibiofemoral OA.

Materials and Methods

We evaluated participants from the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study (MOST), a cohort of 3026 individuals with, or at risk for, knee OA (14). Participants were recruited from Iowa City, Iowa and Birmingham, Alabama (14). Eligibility criteria for the MOST study have been previously described (14, 15). Briefly, individuals aged 50 – 79 years were eligible if they were overweight or obese; had knee pain, aching, or stiffness for most of the previous 30 days; or had a previous knee injury or surgery. Exclusion criteria included inflammatory, rheumatoid, or other medical conditions (e.g. cancer) that could impact key outcomes; were not ambulatory; or were planning to move away in the three years following enrollment (14).

For this study, we used data from the 60-month and 84-month study visits based on meeting our inclusion criteria (described below). The 60-month study visit was the first visit at which a knee pain map was utilized to assess the location of knee pain, and we used this to define anterior knee pain (Figure 1). Our study sample was limited to individuals with unilateral frequent anterior knee pain for the within-person, knee-matched analyses (our primary approach). We also conducted secondary analyses using a more traditional cohort study approach. Using this approach, we evaluated knees with frequent anterior knee pain in comparison to those without knee pain. For both approaches, we excluded individuals with total knee replacement (TKR).

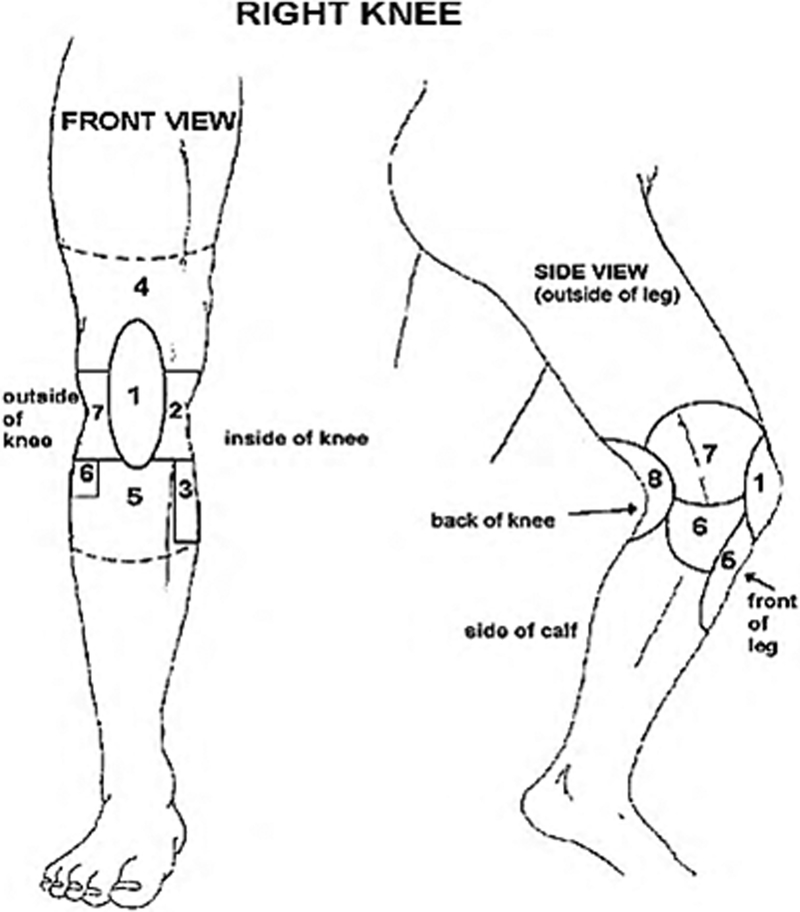

Figure 1.

Knee pain map completed by MOST study participants at 60- and 84-month visits

Patellofemoral alignment and trochlear morphology:

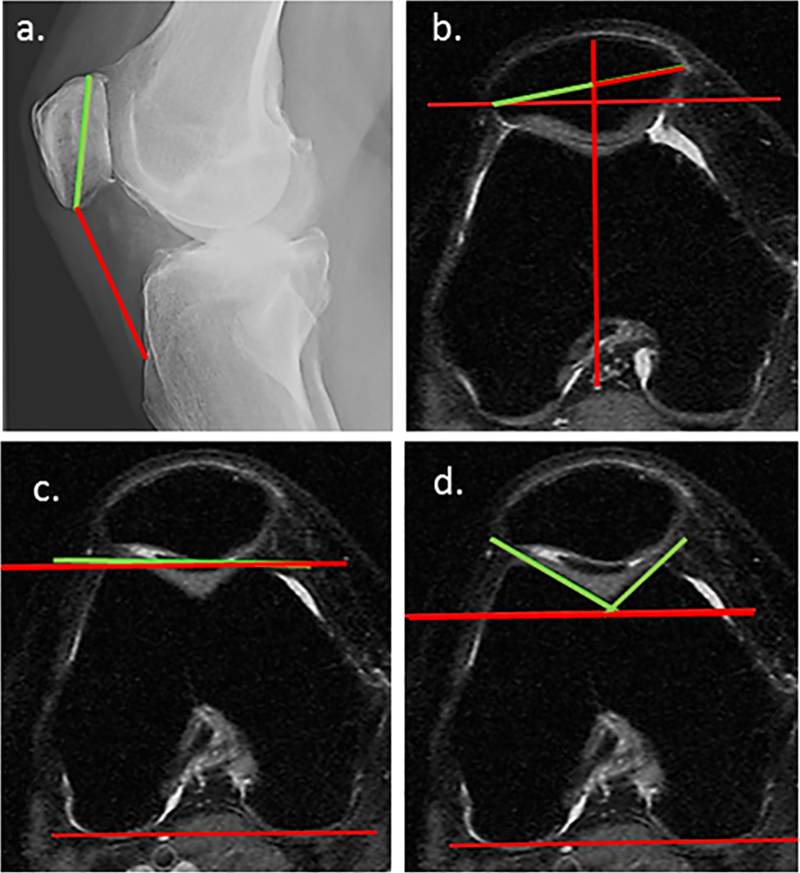

We used lateral view radiographs to measure patellar height with Insall-Salvati ratio (16) (Figure 2). Insall-Salvati ratio represents a ratio of the length of the patellar tendon to the oblique patella length. Patella alta is defined as a ratio ≥ 1.2, and patella baja, a ratio ≤ 0.8 based on a previous study defining confidence limits of structurally normal knees (16).

Figure 2.

a. Insall-Salvati ratio: ratio, patellar tendon length to oblique patellar length; b. Bisect offset: percentage of patella lying lateral to the line bisecting the sulcus; Patellar tilt angle: angle formed by line through greatest width of patella and transposed posterior condylar line; c. Trochlear angle: angle between anterior and posterior condylar lines; d. Sulcus angle: angle formed by lateral and medial trochlear facet margins; Lateral trochlear inclination: angle between lateral trochlear facet margin and posterior condylar line; Medial trochlear inclination: angle between medial trochlear facet margin and posterior condylar line.

We used MR images to calculate the remaining alignment measures (bisect offset, patellar tilt) (17) and morphology measures (sulcus angle, trochlear angle, lateral and medial trochlear inclination) (18) (Figure 2). MR images were acquired in a 1.0 tesla scanner (OrthOne; GE Healthcare) using axial fat saturated fast spin echo proton density weighted sequences (echo time 13.2, repetition time 5500, slice thickness 3 mm, gap 0 mm, acquisition matrix 288 × 192, echo train length 10).

To measure alignment, we first selected the axial MRI slice with the largest representation of the posterior femoral condyles (i.e., adjacent slices demonstrated a smaller amount of posterior femoral condyle) (Figure 2). On this slice, we drew a line connecting the two posterior condyles. We then transposed this line onto the axial slice with the maximum mediolateral patellar width. On this latter slice, we measured bisect offset and patellar tilt angle. Bisect offset is a measure of the percentage (%) of patellar width lateral to a line that is perpendicular to the posterior condylar line and bisects the sulcus (Figure 2b). Patellar tilt angle (°) is formed by a line through the greatest width of the patella relative to the posterior condylar line (Figure 2b). High bisect offset was previously defined as ≥ 61.6%; high patellar tilt angle as ≥ 17.2°, and low patellar tilt angle as ≤ 0.0° based on confidence limits of a population-based sample without patellofemoral OA and without pain (7).

To measure trochlear morphology, we used only the first MRI slice with the largest posterior femoral condyles. Trochlear angle (°) is formed by the anterior and posterior condylar lines (Figure 2c), and is defined as high at ≥ 4.7° (7). Sulcus angle (°) is formed by the lateral and medial trochlear facet margins (Figure 2d), and is defined as wide at ≥ 141.5° (7). Lateral trochlear inclination (°) is the angle formed by the lateral trochlear facet margin and posterior condylar line (Figure 2d), and is defined as shallow at ≤ 18.6° (7). Medial trochlear inclination (°) is the angle formed by the medial trochlear facet margin and posterior condylar line (Figure 2d), and is defined as shallow at ≤ 21.5° (7).

For within-person, knee-matched analyses of unilateral anterior knee pain (described below), a single author (EMM) assessed all patellofemoral alignment and trochlear morphology measures in both knees . Images were not evaluated in pairs, and the evaluator was also blinded to which knee was painful. For the cohort study comparisons (described below), a second author (RW) independently assessed all MRI-based patellofemoral alignment and trochlear morphology measures in a single knee, and a third author (MR) independently assessed lateral radiographs to evaluate Insall-Salvati ratio (19). All investigators who measured alignment and morphology were trained by the same investigator (JJS) until adequate inter-rater reliability was achieved (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC 2,1] ≥ 0.80). We have previously reported intra-rater reliability ICC 2,1 ≥ 0.89 and inter-rater reliability ICC 2,1 ≥0.80 using similar measurement protocols and training methods(7, 18, 20). All measurements were made using OsiriX Lite version 9.0 (within-person measures) and version 8.0 (between-group measures) (Pixmeo SARL, Switzerland).

Radiographic osteoarthritis:

Radiographs were acquired in two views, postero-anterior (PA) and lateral. Skyline views were not acquired in the MOST study. All radiographs were scored on a scale of 0 – 3, informed by atlases of the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) for the PA view, and of the Framingham Osteoarthritis Study for the lateral view (21, 22).

Tibiofemoral OA was defined as Kellgren & Lawrence grade of at least 2 on PA radiographs (23, 24). Patellofemoral OA was defined as either (i) prevalence of any osteophytes of at least grade 2, or (ii) joint space narrowing of at least grade 2 plus any osteophyte, sclerosis, or cyst of at least grade 1 in the patellofemoral joint (24, 25). Two raters independently scored all radiographs, and in cases where there was disagreement regarding the presence of OA, a panel of three adjudicators resolved discrepancies (26).

Anterior knee pain:

Our primary outcome measure, anterior knee pain, was operationalized as frequent knee pain that was isolated to the anterior knee region. We defined this as: (i) a response of ‘yes’ to the question “During the past 30 days, have you had pain, aching, or stiffness in your knee on most days?” at the in-person clinic visit; and (ii) the pain was reported to be isolated to the anterior knee region using a knee pain map (Figure 1).

Within-person, knee-matched unilateral anterior knee pain analyses:

For the within-person, knee-matched analyses, we identified individuals who had strictly defined unilateral knee pain, meaning they had frequent isolated anterior knee pain (as defined above) in one knee only, and did not have frequent knee pain in the contralateral knee. For these analyses, we included individuals who met these criteria at the 60-month clinic visit or at the 84-month visit. If participants had unilateral anterior knee pain at both visits, the 60-month data only were included in the analyses. We evaluated both knees in all within-person, knee-matched analyses.

Cohort analyses:

At the 60-month study visit, we identified knees with frequent isolated anterior knee pain, as well as knees without frequent knee pain. Knees were excluded from the present study if there was frequent knee pain but that was not isolated to the anterior knee region. From this subsample, we evaluated one knee per participant in individuals who had previously had patellofemoral alignment and trochlear morphology measured in a single randomly selected knee (19). However, radiographs were available and graded for both knees in this sample. Therefore, we evaluated both knees of participants in all analyses of radiographic OA.

Statistical analyses:

Within-person, knee-matched unilateral anterior knee pain analyses:

We examined the relation of each alignment or morphology exposure (bisect offset, patellar tilt angle, sulcus angle, lateral trochlear inclination, medial trochlear inclination, trochlear angle, and Insall-Salvati ratio) to the presence of anterior knee pain using conditional logistic regression in separate models, with each individual’s knees analyzed as a matched pair. In addition to crude models, we adjusted for knee-specific variables, i.e., patellofemoral OA and history of knee injury or surgery. Similarly, to evaluate patellofemoral OA as the exposure, we calculated crude odds ratios (OR) and also adjusted for tibiofemoral OA and history of knee injury or surgery. When we evaluated tibiofemoral OA as the exposure variable, we additionally adjusted for patellofemoral OA and history of knee injury or surgery.

Cohort analyses:

We examined the relation of each degree increase in patellofemoral alignment and trochlear morphology, and of presence of patellofemoral and tibiofemoral OA, to presence of anterior knee pain in separate generalized estimating equation models (distribution: poisson, link: log with robust variance estimation). We calculated prevalence ratios (PR) adjusting for age, BMI, and sex, then further adjusted for radiographic OA (patellofemoral or tibiofemoral), and history of injury or surgery to the knee. When both knees were included in the model, we used a repeated subject statement to account for the within-person correlation.

All statistical analyses were done using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Within-person, knee-matched unilateral anterior knee pain analyses:

We identified 110 individuals who met the criteria for unilateral frequent anterior knee pain (see Table 1 and 2 for participant characteristics). Of these 110 participants, 71 had bilateral MR images for evaluating the association of alignment and morphology to anterior knee pain. All 110 participants had bilateral radiographs for evaluating the association of radiographic OA to anterior knee pain.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics. All numbers are n (%) unless otherwise noted.

| Within-person matched knee analyses (n=110) | Cohort MRI analyses (single knee) (n=882) |

Cohort radiograph analyses (two knees) (n=1818) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequent isolated anterior knee pain (n=58) |

No frequent knee pain (n=824) |

Frequent isolated anterior knee pain (n=230)* |

No frequent knee pain (n=2906) |

||

| Age (years) mean (SD) | 70.0 (7.6) | 69.0 (6.9) | 66.9 (7.6) | 68.7 (7.8) | 67.8 (7.8) |

| BMI (kg/m2) mean (SD) | 30.9 (6.3) | 29.9 (4.9) | 29.3 (4.8) | 31.1 (6.6) | 30.2 (5.7) |

| Women | 70 (64%) | 39 (67%) | 486 (59%) | 158 (68.7%) | 1660 (57.1%) |

| Patellofemoral ROA | 32 (30%) – index (painful) 19 (18%) – contralateral |

14 (25%) | 86 (10%) | 54 (28.1%) | 346 (13.0%) |

| Tibiofemoral ROA | 55 (51%) – index (painful) 47 (44%) – contralateral |

22 (39%) | 256 (31%) | 90 (46.4%) | 926 (34.8%) |

| History of surgery or injury | 48 (44%) – index (painful) 29 (26%) – contralateral |

19 (33%) | 224 (27%) | 68 (29.6%) | 872 (30.0%) |

BMI = body mass index, ROA = radiographic osteoarthritis

Sample sizes for radiograph analyses groups are number of knees, as are descriptive statistics. All remaining sample sizes and descriptive statistics are participant level.

Table 2.

Alignment and morphology. Mean (SD) for knees with anterior knee pain and knees without pain; and n (%) of knees exceeding reference values.

| Within-person matched knee analyses (n=110 radiograph, 71 MRI) |

Cohort MRI analyses (single knee) (n=882) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequent anterior knee pain mean (SD) |

Exceed reference values* n (%) |

No frequent knee pain mean (SD) | Exceed reference values n (%) |

Frequent anterior knee pain (n=58) mean (SD) |

Exceed reference values* n (%) |

No frequent knee pain (n=824) mean (SD) |

Exceed reference values n (%) |

|

| Insall-Salvati ratio | 1.08 (0.18) | 32 (29%) | 1.10 (0.16) | 29 (26%) | 1.09 (0.13) | 14 (25%) | 1.07 (0.15) | 207 (25%) |

| Bisect offset (%) | 61.07 (8.56) | 27 (39%) | 60.99 (10.57) | 29 (41%) | 61.29 (9.52) | 24 (43%) | 59.41 (9.33) | 291 (36%) |

| Patellar tilt angle (°) | 9.24 (5.77) | 8 (11%) | 9.89 (6.47) | 10 (14%) | 11.30 (5.71) | 7 (13%) | 10.29 (5.47) | 86 (11%) |

| Trochlear angle (°) | 3.19 (2.97) | 23 (32%) | 3.05 (3.11) | 24 (34%) | 4.05 (3.52) | 24 (43%) | 4.14 (3.31) | 344 (43%) |

| Sulcus angle (°) | 137.23 (9.21) | 21 (30%) | 136.29 (7.80) | 15 (21%) | 137.14 (9.54) | 18 (32%) | 136.22 (8.99) | 222 (28%) |

| Lateral trochlear inclination (°) | 24.22 (6.69) | 8 (11%) | 24.01 (4.76) | 12 (17%) | 22.43 (5.41) | 13 (23%) | 23.17 (4.83) | 136 (17%) |

| Medial trochlear inclination (°) | 24.30 (6.38) | 19 (27%) | 24.60 (5.60) | 27 (39%) | 20.77 (7.21) | 31 (55%) | 20.90 (6.47) | 412 (51%) |

No patellofemoral alignment or trochlear morphology measures differed between knees with anterior knee pain compared with knees without pain (see Table 3). The odds of having anterior knee pain was increased in those knees with radiographic patellofemoral OA compared with those without (OR 5.3 [95% CI 1.6, 18.3]. There was no association between radiographic tibiofemoral OA and anterior knee pain.

Table 3.

Within-person knee-matched unilateral anterior knee pain results.

| Sample size |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

p | Adjusted OR^

(95% CI) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insall Salvati | 110 | 0.97 (0.93, 1.01)* | 0.11 | 0.98 (0.94, 1.03) | 0.45 |

| Bisect offset (%) | 69 | 0.99 (0.94, 1.05) | 0.80 | 0.99 (0.94, 1.05) | 0.77 |

| Patellar tilt angle (°) | 69 | 0.94 (0.86, 1.03) | 0.18 | 0.94 (0.85, 1.04) | 0.20 |

| Trochlear angle (°) | 71 | 1.03 (0.89, 1.20) | 0.70 | 1.04 (0.87, 1.24) | 0.66 |

| Sulcus angle (°) | 71 | 1.03 (0.97, 1.09) | 0.35 | 1.01 (0.95, 1.07) | 0.84 |

| Lateral trochlear inclination (°) | 71 | 1.02 (0.92, 1.13) | 0.70 | 1.06 (0.95, 1.19) | 0.30 |

| Medial trochlear inclination (°) | 71 | 0.99 (0.92, 1.06) | 0.70 | 0.99 (0.92, 1.07) | 0.88 |

| Prevalence | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

p | Adjusted OR^ (95% CI) |

p | |

| Patellofemoral ROA | 5.33 (1.55, 18.30) | 0.01 | 4.87 (1.39, 17.05) | 0.01 | |

| Index (painful) | 32/108 (30%) | ||||

| Contralateral | 19/108 (18%) | ||||

| Tibiofemoral ROA | 1.73 (0.82, 3.63) | 0.15 | 1.33 (0.58, 3.05) | 0.50 | |

| Index | 55/108 (51%) | ||||

| Contralateral | 47/108 (44%) |

ROA = radiographic osteoarthritis

Note odds ratios for alignment and morphology measures are all per degree (or per percentage) difference between knees.

Adjusted for patellofemoral radiographic OA and history of surgery or injury (with PFROA as exposure, adjusted for tibiofemoral radiographic OA and history of surgery or injury)

Cohort analyses:

Of 1174 participants with readable MR images for evaluating patellofemoral alignment and trochlear morphology, 58 individuals met the criteria for frequent isolated anterior knee pain, 824 had no frequent knee pain, and the rest had pain that was not isolated to the anterior knee region and were thus excluded from further analyses (see Table 1 and 2 for participant characteristics). Of participants with bilateral radiographs scored for tibiofemoral and patellofemoral OA, 230 knees met the criteria for frequent isolated anterior knee pain, 2906 knees had no frequent knee pain, and the rest were excluded from further analyses.

Patellofemoral alignment and trochlear morphology did not differ between knees with anterior knee pain compared with knees without knee pain (see Table 4). Radiographic patellofemoral OA was associated with greater prevalence of anterior knee pain (PR 2.2 [95% CI 1.4, 3.5]). Radiographic tibiofemoral OA was not associated with anterior knee pain.

Table 4.

Cohort study results.

| Sample size |

Adjusted Prevalence Ratio (95% CI) |

p | Further adjusted PR (95% CI)^ | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insall Salvati | 876 | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02)* | 0.47 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | 0.58 |

| Bisect offset (%) | 857 | 1.02 (0.99, 1.04) | 0.16 | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 0.42 |

| Patellar tilt angle (°) | 857 | 1.03 (0.98, 1.08) | 0.20 | 1.02 (0.98, 1.07) | 0.30 |

| Trochlear angle (°) | 858 | 0.99 (0.91, 1.07) | 0.73 | 1.00 (0.92, 1.08) | 0.96 |

| Sulcus angle (°) | 858 | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 0.50 | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 0.68 |

| Lateral trochlear inclination (°) | 858 | 0.97 (0.92, 1.03) | 0.30 | 0.98 (0.93, 1.04) | 0.55 |

| Medial trochlear inclination (°) | 858 | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | 0.92 | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | 0.94 |

| Prevalence | Adjusted PR (95% CI) |

p | Further adjusted PR (95%CI)^ | p | |

| Patellofemoral ROA | 2.19 (1.39, 3.45) | 0.001 | 2.05 (1.25, 3.37) | 0.005 | |

| Knees with pain | 54/192 (28.1%) | ||||

| Knees without pain | 346/2664 (13.0%) | ||||

| Tibiofemoral ROA | 1.44 (0.95, 2.17) | 0.09 | 1.21 (0.76, 1.93) | 0.42 | |

| Knees with pain | 90/194 (46.4%) | ||||

| Knees without pain | 926/2664 (34.8%) |

ROA = radiographic osteoarthritis

Prevalence ratios for alignment and morphology measures are all per degree (or per percentage), analyses are based on one knee per participant (PFROA and TFROA analyses are based on two eligible knees per participant)

In addition to sex, BMI, and age, we also included patellofemoral radiographic OA and history of surgery or injury (for PFROA, included tibiofemoral radiographic OA and history of injury or surgery)

Discussion

Contrary to our initial study hypotheses, patellofemoral alignment and morphology were not associated with frequent isolated anterior knee pain in individuals with, or at risk of, knee OA. However, our secondary hypothesis was supported, in that patellofemoral radiographic OA was associated with anterior knee pain, and tibiofemoral OA was not. These results persisted using two different study designs, which enhances the robustness and generalizability of our findings.

In the within-person knee-matched sample, patellofemoral alignment and trochlear morphology were generally symmetrical between knees. In addition, a substantial portion of the knees in our study had patellofemoral alignment and trochlear morphology values that exceeded previously established reference values (7, 16). This occurred in both study designs, in knees both with and without frequent isolated anterior knee pain. Thus, patellofemoral malalignment and trochlear dysplasia may be more common in individuals with, or at risk of, knee OA, compared with population-based samples with no pain or patellofemoral OA. It is unknown to what extent malalignment and trochlear dysplasia in currently pain-free knees may increase risk for future pain episodes.

Patellofemoral alignment and trochlear morphology have previously been shown to be associated with patellofemoral OA (6, 7) and with any knee pain (7). Alignment and morphology also differ in younger individuals with patellofemoral pain compared to healthy pain-free controls, most notably bisect offset and patellar tilt while the lower limb is loaded, and sulcus angle (27). While no previous studies had looked at associations between alignment and morphology and localized anterior knee pain in individuals with, or at risk of, knee OA, these findings informed our hypothesis that we would detect an associated in the present study. Several factors may explain our negative findings. First, in the MOST cohort, MRI images were acquired with knees unloaded and positioned near full extension. Loading the knee may increase patellar malalignment due to the direction of pull of the quadriceps (thus explaining the positive findings in patellofemoral pain). Second, pain is a complex, variable, and subjective phenomenon that is difficult to objectively quantify. It is unknown to what extent these challenges make it difficult to consistently detect associations of various factors to pain across different studies. Finally, it may also be that the true associations with anterior knee pain differ in individuals with, or at risk for, knee OA compared to individuals with patellofemoral pain. For example, alignment or morphology may be associated with knee pain in general in an OA population, but not with pain manifesting exclusively as anterior knee pain.

Importantly, patellofemoral radiographic OA was associated with anterior knee pain in our study, while tibiofemoral radiographic OA was not. This persisted using two different study designs, and provides face validity that anterior knee pain is reflective of patellofemoral pathology. Altered alignment, either independently or in relation to trochlear dysplasia (and thus loss of passive bony stability during daily activities), may cause patellofemoral OA via increased focal patellofemoral joint stress (28). It may be that patellofemoral OA thus serves as a mediator between alignment or morphology and pain. In individuals with patellofemoral OA, patellofemoral alignment may be modifiable with conservative methods such as tailored taping (29) or bracing (30), and this may also reduce knee pain, particularly when applied in combination with exercise therapy (29, 31). Based on our study results, malalignment may not be driving the pain experience. Any benefits derived from taping, for example, may be achieved through altering malalignment but may also be due to other aspects of taping such as neurophysiological effects. Further research evaluating any treatments for patellofemoral OA or pain should incorporate mechanistic outcomes (such as measuring alignment or morphology) to gain insight as to the role of these mechanical factors underpinning symptoms and response to treatment.

Limitations

Compared to structural features of knee OA, pain is a subjective phenomenon that is highly variable, complex, and multifactorial in nature. Moreover, radiographic patellofemoral OA was diagnosed with only lateral view radiographs, as skyline view radiographs were not taken in the MOST cohort. Both of these could have resulted in participant misclassification, which may have influenced the results of our study. Given that this is a cross-sectional study, it also limits our ability to draw conclusions regarding causation.

Our within-person, knee-matched approach removes the effects of person-level differences since such factors are the same for both knees within an individual. Nonetheless, to improve generalizability and examine the reproducibility of our results with a more traditional study design, and in a larger sample size, we also conducted a cohort study, which showed similar results. With a traditional observational study design, an inherent limitation is the difficulty in adequately accounting for all potential confounders, including, by definition, unknown factors that may influence pain outcomes. We therefore elected to use both approaches together in the same study to more comprehensively address our research aims, with both approaches providing similar findings.

Conclusions

Patellofemoral alignment and trochlear morphology were not cross-sectionally associated with frequent isolated anterior knee pain in individuals with, or at risk for, knee OA. Patellofemoral radiographic OA, however, was associated with anterior knee pain, suggesting that there are pathologic features of OA that are contributing to these symptoms. Future larger studies are required to determine if patellofemoral OA is a mediator between alignment or morphology and pain, and what pathologic features of patellofemoral OA itself contribute to anterior knee pain.

Significance and Innovations:

Patellofemoral alignment and trochlear morphology are not associated with localized anterior knee pain

Malalignment and trochlear dysplasia may not be driving the pain experience in OA

Radiographic patellofemoral osteoarthritis, but not tibiofemoral osteoarthritis, are associated with localized anterior knee pain

Future studies are needed to determine which specific features of patellofemoral OA contribute to localized anterior knee pain

Grants and financial support, and potential conflicts of interest:

The Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study was funded by the NIH (U01-AG18820, U01-AG18832, U01-AG18947, U01-AG19069 and AR-47785). J. Stefanik and E. Macri were supported by NIH/NIGMS U54- GM104941. J. Stefanik was also supported by K23-AR070913. T. Neogi was supported by K24-AR070892 and P60-AR047785 and R01 AR062506. Funding sources had no role in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of the data or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Kobayashi S, Pappas E, Fransen M, Refshauge K, Simic M. The prevalence of patellofemoral osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23:A189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duncan R, Peat G, Thomas E, Hay EM, Croft P. Incidence, progression and sequence of development of radiographic knee osteoarthritis in a symptomatic population. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(11):1944–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lankhorst N, Damen J, Oei E, Verhaar J, Kloppenburg M, Bierma-Zeinstra S, et al. Incidence, prevalence, natural course and prognosis of patellofemoral osteoarthritis: the Cohort Hip and Cohort Knee study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(5):647–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stefanik JJ, Guermazi A, Roemer FW, Peat G, Niu J, Segal NA, et al. Changes in patellofemoral and tibiofemoral joint cartilage damage and bone marrow lesions over 7 years: the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24(7):1160–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins NJ, Barton CJ, van Middelkoop M, Callaghan MJ, Rathleff MS, Vicenzino BT, et al. 2018 Consensus statement on exercise therapy and physical interventions (orthoses, taping and manual therapy) to treat patellofemoral pain: recommendations from the 5th International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat, Gold Coast, Australia, 2017. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macri EM, Stefanik JJ, Khan KM, Crossley KM. Is tibiofemoral or patellofemoral alignment or trochlear morphology associated with patellofemoral osteoarthritis? A systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(10):1453–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macri EM, Felson DT, Zhang Y, Guermazi A, Roemer FW, Crossley KM, et al. Patellofemoral morphology and alignment: reference values and dose-response patterns for the relation to MRI features of patellofemoral osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25:1690–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neogi T, Guermazi A, Roemer F, Nevitt MC, Scholz J, Arendt-Nielsen L, et al. Association of joint inflammation with pain sensitization in knee osteoarthritis: the multicenter osteoarthritis study. Arthritis rheumatol. 2016;68(3):654–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fingleton C, Smart K, Moloney N, Fullen B, Doody C. Pain sensitization in people with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(7):1043–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rathbun AM, Stuart EA, Shardell M, Yau MS, Baumgarten M, Hochberg MC. Dynamic effects of depressive symptoms on osteoarthritis knee pain. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018;70(1):80–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neogi T, Felson D, Niu J, Nevitt M, Lewis CE, Aliabadi P, et al. Association between radiographic features of knee osteoarthritis and pain: results from two cohort studies. BMJ. 2009;339:b2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birmingham TB, Marriott KA, Leitch KM, Moyer RF, Lorbergs AL, Walton DM, et al. Association Between Knee Load and Pain: Within-Patient, Between-Knees, Case-Control Study in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steidle-Kloc E, Culvenor AG, Dorrenberg J, Wirth W, Ruhdorfer A, Eckstein F. Relationship Between Knee Pain and Infrapatellar Fat Pad Morphology: A Within- and Between-Person Analysis From the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018;70(4):550–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Multicentre Osteoarthritis Study Public Data Sharing 2009. [cited 2017 21 December]. Available from: www.most.ucsf.edu. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felson DT, Niu J, Guermazi A, Roemer F, Aliabadi P, Clancy M, et al. Correlation of the development of knee pain with enlarging bone marrow lesions on magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(9):2986–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Insall J, Salvati E. Patella Position in the Normal Knee Joint 1. Radiology. 1971;101(1):101–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stefanik JJ, Zumwalt AC, Segal NA, Lynch JA, Powers CM. Association between measures of patella height, morphologic features of the trochlea, and patellofemoral joint alignment: the MOST study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(8):2641–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stefanik JJ, Roemer FW, Zumwalt AC, Zhu Y, Gross KD, Lynch JA, et al. Association between measures of trochlear morphology and structural features of patellofemoral joint osteoarthritis on MRI: the MOST study. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2012;30(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Widjajahakim R, Roux M, Jarraya M, Roemer FW, Neogi T, Lynch JA, et al. Relationship of Trochlear Morphology and Patellofemoral Joint Alignment to Superolateral Hoffa Fat Pad Edema on MR Images in Individuals with or at Risk for Osteoarthritis of the Knee: The MOST Study. Radiology. 2017;284(3):806–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stefanik J, Zhu Y, Zumwalt A, Gross K, Clancy M, Lynch J, et al. Association between patella alta and the prevalence and worsening of structural features of patellofemoral joint osteoarthritis: the multicenter osteoarthritis study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(9):1258–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altman RD, Hochberg M, Murphy WA, Jr., Wolfe F, Lequesne M. Atlas of individual radiographic features in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1995;3 Suppl A:3–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaisson CE, Gale DR, Gale E, Kazis L, Skinner K, Felson DT. Detecting radiographic knee osteoarthritis: what combination of views is optimal? Rheumatology. 2000;39(11):1218–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16(4):494–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Felson DT, Zhang Y, Hannan MT, Naimark A, Weissman B, Aliabadi P, et al. Risk factors for incident radiographic knee osteoarthritis in the elderly. The Framingham Study. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(4):728–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felson DT, McAlindon TE, Anderson JJ, Weissman BW, Aliabadi P, Evans S, et al. Defining radiographic osteoarthritis for the whole knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1997;5(4):241–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roemer FW, Guermazi A, Hunter DJ, Niu J, Zhang Y, Englund M, et al. The association of meniscal damage with joint effusion in persons without radiographic osteoarthritis: the Framingham and MOST osteoarthritis studies. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17(6):748–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drew BT, Redmond A, Smith T, Penny F, Conaghan P. Which patellofemoral joint imaging features are associated with patellofemoral pain? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24(2):224–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farrokhi S, Keyak J, Powers C. Individuals with patellofemoral pain exhibit greater patellofemoral joint stress: a finite element analysis study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(3):287–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crossley K, Marino G, Macilquham M, Schache A, Hinman R. Can patellar tape reduce the patellar malalignment and pain associated with patellofemoral osteoarthritis? Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(12):1719–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Callaghan M, Guney H, Reeves N, Bailey D, Doslikova K, Maganaris C, et al. A knee brace alters patella position in patellofemoral osteoarthritis: a study using weight bearing magnetic resonance imaging. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24(12):2055–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crossley KM, Vicenzino B, Lentzos J, Schache AG, Pandy MG, Ozturk H, et al. Exercise, education, manual-therapy and taping compared to education for patellofemoral osteoarthritis: A blinded, randomised clinical trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(9):1457–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]