Abstract

The highly selective synthesis of spirobiindanes, alkenyl chlorides, and monofluoroalkenes via the cleavage of inert C(sp3)–F bonds in unactivated gem-difluoroalkanes using readily available and inexpensive aluminum-based Lewis acids of low toxicity is reported. The selectivity of this reaction can be controlled by modifying the substituents on the central aluminum atom of the promoter. An intramolecular cascade Friedel-Crafts alkylation of unactivated gem-difluorocarbons can be achieved using a stoichiometric amount of AlCl3. The subsequent synthesis of alkenyl chlorides via F/Cl exchange followed by an elimination can be accomplished using AlEt2Cl as a fluoride scavenger and halogen source. The defluorinative elimination of acyclic and cyclic gem-difluorocarbons to give monofluoroalkenes can be achieved using AlEt3.

Subject terms: Synthetic chemistry methodology, Reactive precursors

Introduction

The widespread use of a variety of readily available organofluorine molecules in the chemical industry and the environmental concerns caused by the longevity of some potentially toxic fluorinated organic compounds has inspired impressive advances of the defluorinative functionalization of carbon-fluorine (C–F) bond1–6. In contrast to the considerable number of reports that focus on the transition-metal-mediated or -catalyzed cleavage of C(sp2)–F bonds in aromatic and vinylic fluorocarbons2–4,6, the direct degradation of C(sp3)–F bonds in unactivated aliphatic fluorides remains challenging7,8.

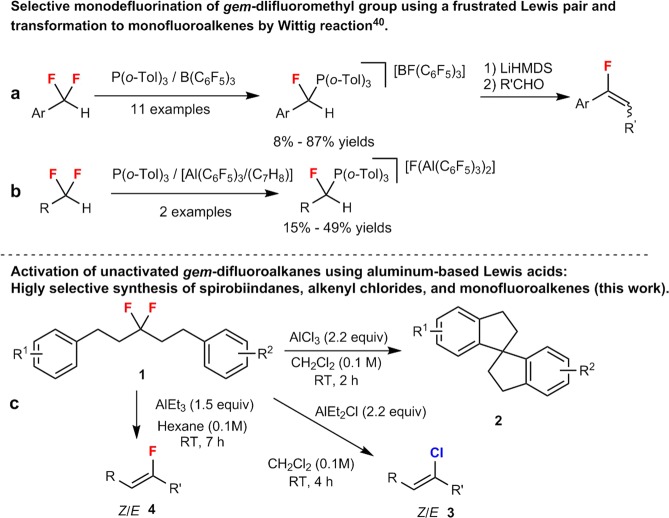

Main-group-based Lewis acids that promote fluoride-abstraction processes have dramatically emerged in recent decades as an attractive strategy to selective functionalize inert C(sp3)–F bonds7,9–12. Although the fluoride moiety in C–F bonds is neither a good leaving group nor a good Lewis base13,14, the formation of more stable covalent bonds (e.g. Si–F, B–F, Al–F, and P–F) provides in many cases the thermodynamic driving force for this heterolytic transformation7. In particular, practical and economic protocols that render the scission of the C(sp3)–F bond feasible include aluminum-based Lewis acids such as aluminum halides, AlEtCl2, AlEt2Cl, Al(alkyl)3, Al(Oi-Pr)3, or alumina, which are inexpensive, easy to handle, environmentally benign, and commonly used aluminum reagents of low toxicity15–17. In 1938, Henne and Newman reported the fluorine/chlorine (F/Cl) exchange between trifluoromethyl benzene and aluminum chloride18, while the pioneering work of C–F bond activation appeared in the report by Olah and co-workers in 1957, the ionization of C-F bond to synthesize long lived carbocations19. Not only boron based Lewis acids, antimony, bismuth, arsenic based Lewis acids and silica surface also effectively activate C–F bonds20–25. Inspired by these work, using aluminum-based Lewis acids, a wide range of transformations of saturated fluorocarbons, including hydrodefluorinations, halodefluorinations, Friedel-Crafts alkylations, and the formation of C-heteroatom bonds5,7,8 have been studied extensively. However, most of these reports have focused on activated fluoroalkane substrates for further modifications such as benzylic and allylic trifluoroalkanes26–29, as well as benzylic and tertiary aliphatic monofluoroalkanes30,31, all of which afford stabilized carbocation intermediates. Meanwhile, due to their comparatively lower steric congestion, primary monofluoroalkanes have been used for Finkelstein-SN2-type halogen-exchange reactions32,33. However, in spite of recent advances in transition-metal-catalyzed reactions of activated allylic or propargylic gem-difluoroalkanes34,35, there are only a few synthetic methods that use classical aluminum-based Lewis acids on gem-difluorocarbon-type substrates. In early examples, the alkylation and chlorodefluorination of benzylic gem-difluorocarbons has been achieved using an excess of AlCl3, AlMe3, or AlPh328. Subsequently, the SN2′-type alkylation of difluorohomoallyl alcohols can be controlled by trialkylaluminum compounds, which can coordinate to fluorine and adjacent oxygen atoms36,37. Recently, it has been reported that Al(OTf)3 enables the defluorinative cycloaddition/aromatization between benzylic 2,2-difluoroethanol and nitriles to afford oxazoles38. Nevertheless, breaking C(sp3)–F bonds in unactivated gem-difluoroalkanes remains highly challenging39–41. In 2018, Young and co-workers achieved the selective monodefluorination of benzylic and non-benzylic gem-difluoromethyl compounds using a frustrated Lewis pair approach based on B(C6F5)3 and P(o-Tol)3 to generate monofluoro phosphonium salts, which were subsequently convert into monofluoroolefins using Wittig protocols (Fig. 1a). Although the activation of benzylic gem-difluoromethyl groups proceeds in good yields (Fig. 1a), the abstraction of fluoride from unactivated 1,1-difluoroalkanes does not proceed well, and the more fluorophilic Lewis acid [Al(C6F5)3·(C7H8)] (2 equiv.) was required for the transformation, which proceeded in lower yields (Fig. 1b)40.

Figure 1.

Selective defluorination of unactivated gem-difluoroalkanes. (a,b) gem-Difluoro substrates for C–F bond activation (previous work). (c) Selective transformation of gem-difluoro substrates controlled by aluminum reagents (this work).

The occurrence of “over reactions” and poor reaction selectivity, which are mainly caused by unexpected transformations32,39 that include hydride shifts, hydrogen fluoride (HF) eliminations, and skeletal rearrangements of unstable fluoro-substituted carbocation intermediates generated from the initial abstraction of fluoride from a gem-difluoromethyl moiety, renders controlled synthetic methods highly desirable. Recently, we have reported the selective synthesis of spirobiindanes and monofluoroalkenes using B(C6F5)3 and hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP), which exhibits a very high affinity toward fluoride41. Although the method is of great importance as a proof-of-concept, the reaction still requires high temperatures and the relatively expensive reagents B(C6F5)3 and HFIP, which are critical for this transformation. Our continued interest in the activation and modification of inert C(sp3)–F bonds41,42 has led us to examine ubiquitous aluminum-based Lewis acids of low cost for the selective synthesis of spirobiindanes (2), alkenyl chlorides (3), and monofluoroalkenes (4) from unactivated gem-difluoroalkanes (1) under mild conditions. Specifically, we used stoichiometric amounts of AlCl3, AlEt2Cl, or AlEt3 in this study to induce aluminum-fluorine (Al–F) interactions29,43,44 for the direct abstraction of fluoride (Fig. 1c).

Results

Optimization study

The results of the screening of Al-based Lewis acids for the cleavage of C(sp3)–F bonds are summarized in Table 1. Initially, we selected the simple unactivated aliphatic difluoroalkane 3,3-difluoropentane-1,5-diyl)dibenzene (1a) as a substrate. When 2.2 equiv. of AlCl3 was used to initiate an intramolecular Friedel-Crafts cyclizations, the targeted 2,2′,3,3′-tetrahydro-1,1′-spirobi[indene] (2a) was formed in 72% yield (Table 1, entry 1), albeit under heterogeneous conditions. Attempts to render the reaction catalytic were unsuccessful, i.e., the formation of 2a was observed in <10% yield when 0.2 equiv. of AlCl3 were used (entry 3). However, when 1.1 equiv. of AlCl3 were used for the degradation of fluorinated 1a, the defluorinative chlorination/elimination product (3-chloropent-2-ene-1,5-diyl)dibenzene (3a) was formed in 24% yield, together with 2a in 39% yield (entry 2). As alkenyl chlorides represent useful building blocks for the formation of complex organic architectures45–48, establishing control by preventing such “over reactions” in favor of alkenyl chlorides 3 would most likely be as attractive as it would be challenging. To solve this problem, we aimed at decelerating the heterolysis of C(sp3)–F bonds in gem-difluoroalkanes 1 by tuning the Lewis acidity of the aluminum reagents, which could potentially establish control over the reaction selectivity and exclusively afford alkenyl chlorides 3. Therefore, we focused our attention on organoaluminum reagents with reduced Lewis acidity by adding electron-rich alkyl substituents to the central aluminum atom (entries 4–7).

Table 1.

Optimization of the reaction conditions with respect to Al-based Lewis acids.

| Entry | Lewis acids (equiv) | Time (h) | Producta (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2a | 3a | 4a | |||

| 1 | AlCl3 (2.2) | 2 | 72 | ND | ND |

| 2 | AlCl3 (1.1) | 8 | 39 | 24 | ND |

| 3 | AlCl3 (0.2) | 8 | 6 | trace | ND |

| 4 | AlEtCl2 (2.2) | 8 | complex mixture | — | — |

| 5 | AlEt2Cl (2.2) | 4 | ND | 92b | ND |

| 6 | AlEt3 (2.2) | <0.5 | ND | — | 51c |

| 7 | AlEt3 (1.5) | 7 | ND | — | 85d |

aIsolated yields for 2a and 3a. 19F NMR yield for 4a using trifluorotoluene as the internal standard. ND = not detected by 1H or 19F NMR analysis of the crude reaction mixture. bZ/E = 12:1. cZ/E = 7.3:1. dHexane was used as reaction solvent (0.1 M), Z/E = 8.7:1.

Recently, it has been reported that an equimolar amount of AlEtCl2 promotes an intermolecular SN1′-type substitution in 2-trifluoromethyl-1-alkenes29. However, when we treated 1a with 2.2 equiv. of AlEtCl2, we obtained only a tar-like complex mixture (entry 4). Yet, when using the weaker Lewis acid AlEt2Cl, alkenyl chlorides 3 formed exclusively, i.e., the desired 3a was obtained in 92% yield and the formation of side products was not observed (entry 5; for more details, see also Supplementary Fig. 76 in SI). AlEt2Cl has already been reported to facilitate F/Cl exchange reactions in aliphatic monofluoroalkanes at −78 °C via SN1- or SN2-type mechanisms, albeit that these reactions exhibit a very limited substrate scope32. Using AlEt3 under otherwise identical reaction conditions afforded monofluoroalkene 4a in 51% yield without producing any Friedel-Crafts alkylation products (2a). Further improvement of the yield of 4a to 85% was observed upon conducting the reaction in n-hexane, using 1.5 equiv. of AlEt3, and prolonging the reaction time (entry 7; for more details, see also Supplementary Table 1 in SI). However, it should be noted here that the AlEt3-mediated defluorinative elimination of 1,1-difluorocyclopentane has already been reported by Ozerov, albeit only in one special case39. Specifically, the formal HF-abstraction product 1-fluorocyclopent-1-ene was observed in 24% 19F NMR yield after a C6D12 solution of 1,1-difluorocyclopentane (1.5 M) in a J. Young tube had been treated for 24 h with AlEt3 (2.0 equiv.) at room temperature39. Modifying the substituents on the central aluminum atom (AlCl3, AlEt2Cl, and AlEt3) allowed tuning the reaction selectivity for the heterolysis of the C(sp3)–F bonds in unactivated gem-difluoroalkanes 1.

Substrate scope

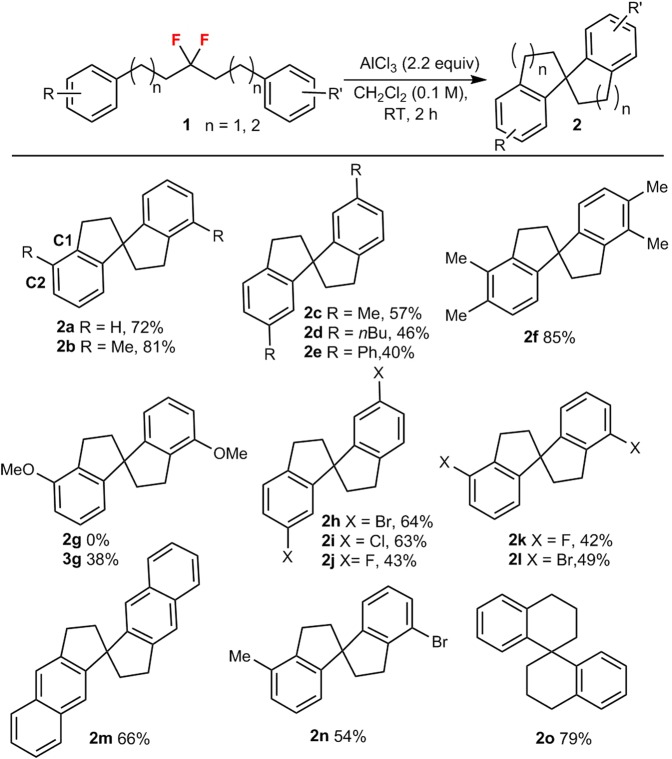

As shown in Fig. 2, aliphatic gem-difluoroalkanes substituted with alkyl groups (1a–f) afford moderate to high yields (up to 85%) of the corresponding spirobiindanes, whereby C2-substituted substrates (1a,b) perform slightly better than C4-substituted substrates (1c–e). Interestingly, when using methoxy-substituted gem-difluoride 1 g, alkenyl chloride 2,2′-(3-chloropent-2-ene-1,5-diyl)bis(methoxybenzene) (3 g) was formed in 38% yield, and the desired Friedel-Crafts alkylation product (2 g) was not observed. Consistent with our strategy that a modification of the Lewis acidity could potentially control the reaction selectivity, the oxygen atom in 1 g probably coordinates to the aluminum center of AlCl3 and thus reduces its Lewis acidity, which would hamper the fluoride-abstraction process, and thus switch the reaction pathway from the expected Friedel-Crafts alkylation to a chlorination/elimination process. The presence of halogen substituents in the gem-difluoroalkanes (1h–l) was well tolerated when using AlCl3, and the corresponding products were generated in acceptable yield (42–64%). Moreover, naphthyl-type 2 m, mixed product 2n, and the six-membered spiro-compound 2o were also obtained in good yield.

Figure 2.

AlCl3-mediated synthesis of spirobiindanes 2.

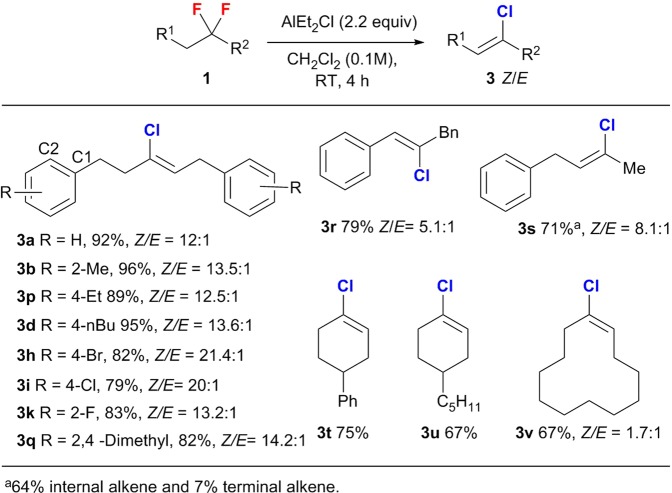

Subsequently, we examined the synthesis of tri-substituted alkenyl chlorides (3) using AlEt2Cl both as an activator and a chloro source (Fig. 3). High yields and good Z/E stereocontrol were observed in most cases; specifically, long-chain acyclic substrates, independent of their substitution pattern on the benzene ring, afforded the desired alkenyl chlorides (3a,b, 3p, 3d, 3h–k, 3q), including halogen-substituted products, in good to high yield (up to 96%) with good Z/E stereoselectivity (up to 21.4:1). In addition, moderate regioselectivity was observed for the defluorinative chlorination/elimination to provide the inner alkene product (3-chlorobut-2-en-1-yl)benzene (3 s), and only ~10% of the corresponding terminal alkene was formed. It should also be noted here that cyclic gem-difluoroalkanes (1t–v) are also well tolerated under the AlEt2Cl-mediated conditions, furnishing the targeted cyclic alkenyl chlorides (3t–3v) in acceptable yield (67–75%).

Figure 3.

AlEt2Cl-mediated synthesis of trisubstituted alkenyl chlorides 3.

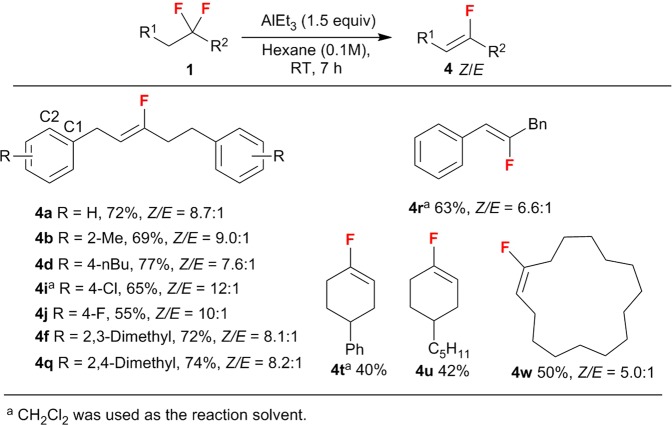

Monofluoroalkenes 4 were obtained via a defluorination/elimination process (Fig. 4). As expected, long-chain acyclic substrates, independent of their substitution pattern on the benzene ring, furnished the desired monofluoroalkenes (4a-b, 4d, 4i,j, 4f, and 4q in moderate to good yield (up to 77%) with good Z/E stereocontrol (up to 12:1). In particular, dialkyl-substituted substrates 1 f and 1q generated the corresponding monofluoroalkenes (4 f and 4q) in 72% and 74% yield, respectively. Furthermore, the defluorination of cyclic substrates including large-ring-type gem-difluoroalkanes proceeded smoothly to afford the corresponding cyclic monofluoroalkenes (4t, 4 u, and 4w) in moderate yield (40–50%)39,49,50.

Figure 4.

AlEt3-mediated synthesis of monofluoroalkenes 4.

Mechanistic investigations

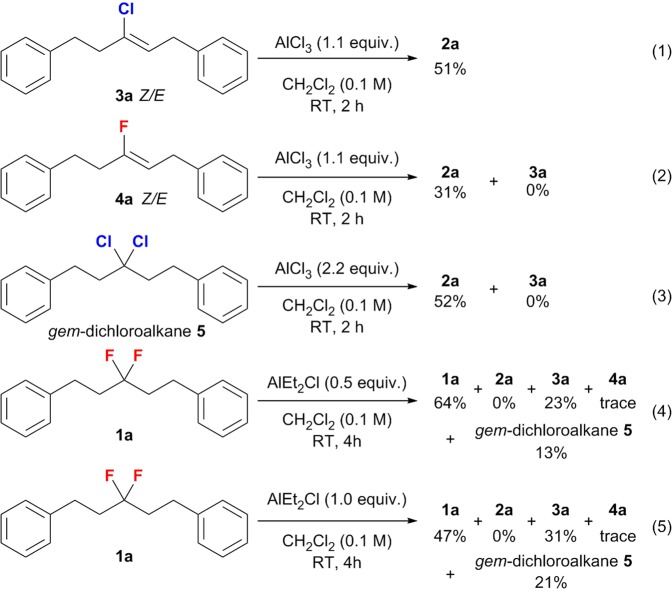

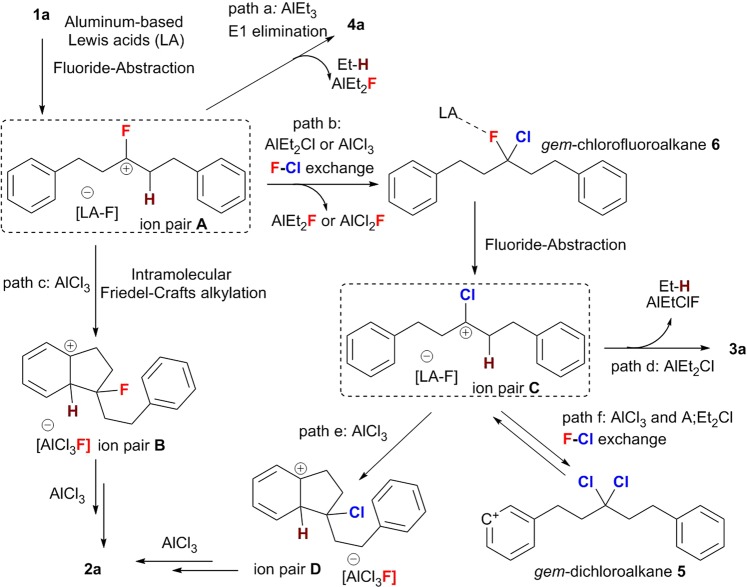

In order to avoid “over reactions” during the modification of inert C(sp3)-F bonds in saturated gem-difluoroalkanes (1), we reduced the Lewis acidity of the Al-based promoters. We observed that such “controllable reactions” stopped at the defluorinative elimination or F-Cl exchange/elimination stage, while further Friedel-Crafts alkylations did not occur. Indeed, using methoxyl-substituted fluorocarbon 1 g and AlCl3 (Fig. 2) represents a special case, as it does not generate the desired spiro product 2 g, but alkenyl chloride 3 g in 38% yield. Accordingly, the vital importance of the Lewis acidity of the aluminum promotors for the reaction selectivity can feasibly be rationalized under consideration of two points: 1. The abstraction of a fluoride anion from the C(sp3)–F bonds is facilitated with increasing strength of the Lewis acidity of the main-group promoter, as the fluorine moiety is neither a good Lewis base nor a good leaving group13. Indeed, species with a stronger formal positive charge such as [Ph3C]+, [R3Si]+, [R2Al]+, [(C6F5)3PF]+, and even P(III) dications with weakly coordinating anions, have recently been used for the direct cleavage and functionalization of C(sp3)–F bonds10,12,51–53. 2. Weaker Lewis acids favor elimination over substitution reactions of carbocation intermediates, which is due to the higher Lewis basicity of the conjugated Lewis bases [LA–F]− (LA = Lewis acid) generated form the heterolytic cleavage of the C–F bonds. Thus, the weaker LA AlEt3 afforded only monofluoroalkenes 4 via a defluorinative elimination, commensurate with the formal loss of one molecule of HF. Although proposing a clear mechanism is difficult due to the potential complexity of the structures of the conjugated Lewis bases [LA–F]−, which may form fluoride-bridged polymetric framework54–57, as well as due to the heterogeneous reaction conditions when using aluminum trichloride58,59, control experiments were conducted (Fig. 5) and a feasible reaction mechanism that would explain the high reaction selectivity is outlined in Fig. 6.

Figure 5.

Control experiments to investigate possible reaction intermediates (percentage values refer to the NMR yield).

Figure 6.

Proposed reaction mechanism.

Initially, the strong Al-F interaction could promote the cleavage of one C(sp3)–F bond in gem-difluoroalkanes to give one tight ion pair (A) between a fluorinated carbocation and a conjugated Lewis base [LA–F]− counter ion. Then, the reaction could proceed via three competitive reaction pathways: 1. Direct elimination of the acidic α-proton of the fluorinated carbocation intermediate to give monofluoroalkenes 4, which is favored in the presence of AlEt3; 2. Twofold intramolecular Friedel-Crafts alkylation in the presence of AlCl3; 3. F-Cl exchange reaction via SN1-type substitutions32 in the presence of AlCl3 or AlEt2Cl. Subsequently, the second abstraction of a fluoride anion could generate the tight ion pair C, which bears a chlorinated carbocation. In a similar fashion, the direct Friedel-Crafts alkylation, the F-Cl exchange, and the E1-type elimination represent three competitive reaction pathways. As mentioned above, when 1.1 equiv. of AlCl3 were used, the trisubstituted alkenyl chloride was detected in 24% yield (Table 1, entry 2). Using alkenyl chloride 3a as the chlorinated carbocation precursor furnished the intramolecular Friedel-Crafts type product 2a in 51% yield in the presence of 1.1 equiv. of AlCl3, while 31% yield were observed when using monofluorinated olefin 4a as the precursor for the fluorinated carbocation intermediate under otherwise identical reaction conditions (Fig. 5). Meanwhile, the F-Cl-exchange-type product 3,3-dichloropentane-1,5-diyl)dibenzene (5) also generated spirobiindane 2a in 52% yield. These results indicate that the cascade intramolecular Friedel-Crafts cyclization is a complex transformation that involves fluorinated carbocations and chlorinated carbocation intermediates, as well as competitive F-Cl exchange reaction pathways. Although we were unable to capture any F-Cl exchange products such as gem-chlorofluoroalkane 6 when using 0.5 equiv. or 1.0 equiv. of AlEt2Cl, the double F-Cl exchange product gem-dichloroalkane 5 was observed in 13% and 21% yield, respectively (Fig. 5; for more details, see the NMR study in Supplementary Figs. 78–85 in SI). Thus, alkenyl chloride 3 is probably generated from the double F-Cl exchange product gem-dichloroalkane 5, which may serve as a reservoir for the chlorinated carbocation intermediate in the tight ion pair C.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have developed a highly selective synthetic route to spirobiindanes 2, trisubstituted alkenyl chlorides 3, and monofluoroalkenes 4, based on the aluminum-induced cleavage of inert C(sp3)–F bonds in unactivated gem-difluoroalkanes 1. The three reaction types can be selectively controlled by using the readily available aluminum-based Lewis acids AlCl3, AlEt2Cl, or AlEt3. Since the reaction can be performed using ubiquitous and cheap aluminum-based Lewis acids at room temperature, these methods should be of high practical utility.

Methods

General procedure for the intramolecular Friedel-Craft reaction of gem-difluoroalkanes

In a flame-dried test tube (10 mL), to the heterogeneous solution of AlCl3 (29.3 mg, 0.22 mmol, 2.2 equiv.) in dry CH2Cl2 (0.5 mL), gem-difluoroalkanes 1 (0.1 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (0.5 mL) was added dropwise by syringe, and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 hours under a positive pressure of argon with a balloon. Then, the resulting mixture was washed with water, extracted with CH2Cl2, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and then concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel using n-hexane as the eluent to afford the desired spirobiindanes 2a-n and spirobitetraline 2o. In addition, alkenyl chloride 3 g, 2,2′-(3-chloropent-2-ene-1,5-diyl)bis(methoxybenzene), was also prepared as one special example. In addition, the gem-difluoroalkanes 1 were prepared based on previous reports via fluorination of corresponding ketones by (diethylamino)sulfur trifluoride or 4-tert-butyl-2,6-dimethylphenylsulfur trifluoride (Fluolead).

General procedure for the synthesis of alkenyl chlorides 3 from gem-difluoroalkanes 1

In a flame-dried test tube (10 mL), diethylaluminum chloride (255 μL, ca. 0.22 mmol, 2.2 equiv., ca. 15% in hexane, ca. 0.87 mol/L) was added slowly to the solution of gem-difluoroalkanes 1 (0.1 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (0.1 M, 1.0 mL), and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 hours under a positive pressure of argon with a balloon. Then, the resulting mixture was washed with water, extracted with CH2Cl2, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and then concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel using n-hexane as the eluent to afford the desired alkenyl chloride 3. The ratio for Z/E isomers was determined by 1H NMR based on previous literature.

General procedure for the synthesis of monofluoroalkene 4 from gem-difluoroalkanes 1

In a flame-dried test tube (10 mL), triethylaluminum (150 μL, ca. 0.15 mmol, 1.5 equiv.,15% in hexane, ca. 1.0 mol/L) was added slowly to the solution of gem-difluoroalkanes 1 (0.1 mmol) in n-hexane (0.1 M, 1.0 mL), and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 7 hours under a positive pressure of nitrogen with a balloon. Then, the resulting mixture was washed with water, extracted with CH2Cl2, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and then concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel to afford the desired monofluoroalkene 4. The ratio for Z/E isomers was determined by 19F NMR.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grants JP 18H02553 (KIBAN B) and J.P. 18H04401 (Middle Molecular Strategy).

Author contributions

N.S. conceived the concept. J.W. conducted the experiments and analyzed the obtained results. J.W. and Y.O. synthesized compounds. Y.O. prepared the starting materials. N.S. designed and directed the project, and N.S. and J.W. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results.

Data availability

The authors declare that all the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files, and also are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-55206-7.

References

- 1.Amii H, Uneyama K. C−F Bond Activation in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:2119–2183. doi: 10.1021/cr800388c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahrens T, Kohlmann J, Ahrens M, Braun T. Functionalization of Fluorinated Molecules by Transition-Metal-Mediated C–F Bond Activation To Access Fluorinated Building Blocks. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:931–972. doi: 10.1021/cr500257c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenstein O, Milani J, Perutz RN. Selectivity of C–H Activation and Competition between C–H and C–F Bond Activation at Fluorocarbons. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:8710–8753. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pike SD, Crimmin MR, Chaplin AB. Organometallic chemistry using partially fluorinated benzenes. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:3615–3633. doi: 10.1039/C6CC09575E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamel J-D, Paquin J-F. Activation of C–F bonds α to C–C multiple bonds. Chem. Commun. 2018;54:10224–10239. doi: 10.1039/C8CC05108A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuehnel MF, Lentz D, Braun T. Synthesis of Fluorinated Building Blocks by Transition-Metal-Mediated Hydrodefluorination Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:3328–3348. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stahl T, Klare HFT, Oestreich M. Main-Group Lewis Acids for C−F Bond Activation. ACS Catal. 2013;3:1578–1587. doi: 10.1021/cs4003244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shen Q, et al. Review of recent advances in C−F bond activation of aliphatic fluorides. J. Fluorine Chem. 2015;179:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2015.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caputo CB, Stephan DW. Activation of Alkyl C–F Bonds by B(C6F5)3: Stoichiometric and Catalytic Transformations. Organometallics. 2012;31:27–30. doi: 10.1021/om200885c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chitnis SS, et al. Phosphorus Coordination Chemistry in Catalysis: Air Stable P(III)-Dications as Lewis Acid Catalysts for the Allylation of C–F Bonds. Organometallics. 2018;37:4540–4544. doi: 10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00686. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bamford KL, Chitnis SS, Qu Z-W, Stephan DW. Interactions of C−F Bonds with Hydridoboranes: Reduction, Borylation and Friedel-Crafts Alkylation. Chem.-Eur. J. 2018;24:16014–16018. doi: 10.1002/chem.201804705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Douvris C, Ozerov OV. Hydrodefluorination of Perfluoroalkyl Groups Using Silylium-Carborane Catalysts. Science. 2008;321:1188–1190. doi: 10.1126/science.1159979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Hagan D. Understanding organofluorine chemistry. An introduction to the C–F bond. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:308–319. doi: 10.1039/b711844a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nolte C, Ammer J, Mayr H. Nucleofugality and Nucleophilicity of Fluoride in Protic Solvents. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:3325–3335. doi: 10.1021/jo300141z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maruoka K, Yamamoto H. Selective Reactions Using Organoaluminum Reagents [New Synthetic Methods (54)] Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1985;24:668–682. doi: 10.1002/anie.198506681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nikonov GI. New Tricks for an Old Dog: Aluminum Compounds as Catalysts in Reduction Chemistry. ACS Catal. 2017;7:7257–7266. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.7b02460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amsharov KY, Kabdulov MA, Jansen M. Facile Bucky‐Bowl Synthesis by Regiospecific Cove‐Region Closure by HF Elimination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:4594–4597. doi: 10.1002/anie.201200516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henne AL, Newman MS. The Action of Aluminum Chloride on Fluorinated Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1938;60:1697–1698. doi: 10.1021/ja01274a046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olah, G. A., Kuhn S. & Olah, J. 416. Aromatic substitution. Part III. Alkylation of aromatic compounds by the boron trifluoride-catalysed reaction of alkyl fluorides. J. Chem. Soc., 2174–2176 (1957).

- 20.Olah GA, Kuhn SJ, Barnes DG. Selective Friedel-Crafts Reactions. I. Boron Halide Catalyzed Haloalkylation of Benzene and Alkylbenzenes with Fluorohaloalkanes. J. Org. Chem. 1964;29:2317–2320. doi: 10.1021/jo01031a051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olah GA, Mo YK. Organic fluorine compounds. XXXIII. Electrophilic additions to fluoro olefins in superacids. J. Org. Chem. 1972;37:1028–1034. doi: 10.1021/jo00972a022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ichikawa, J., Jyono, H., Kudo, T., Fujiwara, M. & Yokota, M. Friedel-Crafts Cyclization of 1,1-Difluoroalk-1-enes: Synthesis of Benzene-Fused Cyclic Ketones via α-Fluorocarbocations. Synthesis, 39–46 (2005).

- 23.Betterley NM, et al. Bi(OTf)3 Enabled C–F Bond Cleavage in HFIP: Electrophilic Aromatic Formylation with Difluoro(phenylsulfanyl)methane. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2018;7:1642–1647. doi: 10.1002/ajoc.201800313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christe KO, Wilson WW, Schack CJ, Wilson RD. Lewis acid induced intramolecular redox reactions of difluoroamino compounds. Inorg. Chem. 1985;24:303. doi: 10.1021/ic00197a013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Culver DB, Conley MP. Activation of C−F Bonds by Electrophilic Organosilicon Sites Supported on Sulfated Zirconia. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:14902–14905. doi: 10.1002/anie.201809199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riera J, Castañer J, Carilla J, Robert A. New synthesis of polychloro(trifluoromethyl)benzenes and highly strained polychloro(trichloromethyl)benzenes. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:3825–3828. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)80668-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramchandani RK, Wakharkar RD, Sudalai A. AlCl3-Catalyzed regiospecific alkylation of aromatics with chlorobenzotrifluorides: A high yield preparation of 1,1-dichlorodiphenylmethanes. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:4063–4064. doi: 10.1016/0040-4039(96)00733-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terao, J., Nakamura M. & Kambe, N. Non-catalytic conversion of C–F bonds of benzotrifluorides to C–C bonds using organoaluminium reagents. Chem. Commun., 6011–6013 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Fuchibe K, Hatta H, Oh K, Oki R, Ichikawa J. Lewis Acid Promoted Single C–F Bond Activation of the CF3 Group: SN1′-Type 3,3-Difluoroallylation of Arenes with 2-Trifluoromethyl-1-alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:5890–5893. doi: 10.1002/anie.201701985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ooi T, Uraguchi D, Kagashima N, Maruoka K. Organoaluminum-catalyzed new alkylation of tert-alkyl fluorides: Synthetic utility of Al–F interaction. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:5679–5682. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(97)01237-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaiswal AK, Goh KKK, Sung S, Young RD. Aluminum-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of Silylalkynes with Aliphatic C–F Bonds. Org. Lett. 2017;19:1934–1937. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terao, J. et al. Conversion of a (sp3)C–F bond of alkyl fluorides to (sp3)C–X (X = Cl, C, H, O, S, Se, Te, N) bonds using organoaluminium reagents. Chem. Commun., 855–857 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Mizukami Y, Song Z, Takahashi T. Halogen Exchange Reaction of Aliphatic Fluorine Compounds with Organic Halides as Halogen Source. Org. Lett. 2015;17:5942–5945. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drouin M, Hamel J-D, Paquin J-F. Exploiting 3,3-Difluoropropenes for the Synthesis of Monofluoroalkenes. Synlett. 2016;27:821–830. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang C-Q, Ye L, Feng C, Loh T-P. C–F Bond Cleavage Enabled Redox-Neutral [4+1] Annulation via C–H Bond Activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:1762–1765. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b12142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yanai H, Okada H, Sato A, Okada M, Taguchi T. Copper-free defluorinative alkylation of allylic difluorides through Lewis acid-mediated C–F bond activation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:2997–3000. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.03.148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sato A, Yanai H, Suzuki D, Okada M, Taguchi T. Synthesis of (Z)-fluoroallyl azides through aluminium-mediated defluorinative functionalization reactions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015;56:925–929. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.12.128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsieh M-T, Lee K-H, Kuo S-C, Lin H-C. Lewis acid-mediated defluorinative [3+2] cycloaddition/aromatization cascade of 2,2-difluoroethanol systems with nitriles. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018;360:1605–1610. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201701581. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gu W, Haneline MR, Douvris C, Ozerov OV. Carbon−Carbon Coupling of C(sp3)−F Bonds Using Alumenium Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:11203–11212. doi: 10.1021/ja903927c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mandal D, Gupta R, Young RD. Selective Monodefluorination and Wittig Functionalization of gem-Difluoromethyl Groups to Generate Monofluoroalkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:10682–10686. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b06770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang J, Ogawa Y, Shibata N. Activation of Saturated Fluorocarbons to Synthesize Spirobiindanes, Monofluoroalkenes, and Indane derivatives. iScience. 2019;17:132–143. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2019.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haufe G, et al. C−F Bond Activation of Unactivated Aliphatic Fluorides: Synthesis of Fluoromethyl-3,5-diaryl-2-oxazolidinones by Desymmetrization of 2-Aryl-1,3-difluoro-2-propanols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:12275–12279. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ooi T, Kagoshima N, Uraguchi D, Maruoka K. Organoaluminum-promoted selective addition to fluorinated carbonyl compounds via pentacoordinate trialkylaluminum complexes. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:7105–7108. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(98)01508-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maruoka K, Ooi T. The Synthetic Utility of the Hypercoordination of Boron and Aluminum. Chem.-Eur. J. 1999;5:829–833. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3765(19990301)5:3<829::AID-CHEM829>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petrone DA, Ye J, Lautens M. Modern Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Carbon–Halogen Bond Formation. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:8003–8104. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Derosa J, et al. Palladium(II)-Catalyzed Directed anti-Hydrochlorination of Unactivated Alkynes with HCl. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:5183–5193. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b00892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iwai T, Fujihara T, Terao J, Tsuji Y. Iridium-Catalyzed Addition of Aroyl Chlorides and Aliphatic Acid Chlorides to Terminal Alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:1268–1274. doi: 10.1021/ja209679c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zeng X, Liu S, Hammond GB, Xu B. Hydrogen-Bonding-Assisted Brønsted Acid and Gold Catalysis: Access to Both (E)- and (Z)-1,2-Haloalkenes via Hydrochlorination of Haloalkynes. ACS Catal. 2018;8:904–909. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.7b03563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vandamme M, Paquin J-F. Eliminative Deoxofluorination Using XtalFluor-E: A One-Step Synthesis of Monofluoroalkenes from Cyclohexanone Derivatives. Org. Lett. 2017;19:3604–3607. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Drouin M, Hamel J-D, Paquin J-F. Synthesis of Monofluoroalkenes: A Leap Forward. Synthesis. 2018;50:881–955. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1591867. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen J, Chen EY-X. Elusive Silane–Alane Complex [Si—H⋅⋅⋅Al]: Isolation, Characterization, and Multifaceted Frustrated Lewis Pair Type Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:6842–6846. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu J, Pérez M, Caputo CB, Stephan DW. Use of Trifluoromethyl Groups for Catalytic Benzylation and Alkylation with Subsequent Hydrodefluorination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:1417–1421. doi: 10.1002/anie.201510494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Forster F, Metsaenen TT, Irran E, Hrobarik P, Oestreich M. Cooperative Al-H Bond Activation in DIBAL-H: Catalytic Generation of an Alumenium-Ion-Like Lewis Acid for Hydrodefluorinative Friedel-Crafts Alkylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:16334–16342. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b09444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen M-C, Roberts JAS, Marks TJ. New Mononuclear and Polynuclear Perfluoroarylmetalate Cocatalysts for Stereospecific Olefin Polymerization. Organometallics. 2004;23:932–935. doi: 10.1021/om0341698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lehmkuhl H. Complex Formation with Organoaluminum Compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1964;3:107–114. doi: 10.1002/anie.196401071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laubengayer AW, Lengnick GF. The Structure and Properties of Diethylfluoroalane, (C2H5)2AlF. Inorg. Chem. 1966;5:503–507. doi: 10.1021/ic50038a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dimitrov A, Heidemann D, Kemnitz E. F/Cl-Exchange on AlCl3-Pyridine Adducts: Synthesis and Characterization of trans-Difluoro-tetrakis-pyridine-aluminum-chloride, [AlF2(Py)4]Cl. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:10807–10814. doi: 10.1021/ic061493x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Petrov VA, Krespan CG, Smart BE. Isomerization of halopolyfluoroalkanes by the action of aluminum chlorofluoride. J. Fluorine Chem. 1998;89:125–130. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1139(98)00098-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krahl T, et al. Structural Insights into Aluminum Chlorofluoride (ACF) Inorg. Chem. 2003;42:6474–6483. doi: 10.1021/ic034106h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files, and also are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.