Abstract

Growing evidence has suggested a possible relationship between dietary calcium intake and metabolic syndrome (MetS) risk. However, the findings of these observational studies are inconclusive, and the dose-response association between calcium intake and risk of MetS remains to be determined. Here, we identified relevant studies by searching PubMed and Web of Science databases up to December 2018, and selected observational studies reporting relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for MetS based on calcium intake and estimated the summary RRs using random-effects models. Eight cross-sectional and two prospective cohort studies totaling 63,017 participants with 14,906 MetS cases were identified. A significantly reduced risk of MetS was associated with the highest levels of dietary calcium intake (RR: 0.89; 95% CI: 0.80–0.99; I2 = 75.3%), with stronger association and less heterogeneity among women (RR: 0.74, 95% CI: 0.66–0.83; I2 = 0.0%) than among men (RR: 1.06, 95% CI: 0.82–1.37; I2 = 72.6%). Our dose-response analysis revealed that for each 300 mg/day increase in calcium intake, the risk of MetS decreased by 7% (RR: 0.93; 95% CI: 0.87–0.99; I2 = 77.7%). In conclusion, our findings suggest that dietary calcium intake may be inversely associated with the risk of MetS. These findings may have important public health implications with respect to preventing the disease. Further studies, in particular longitudinal cohort studies and randomized clinical trials, will be necessary to determine whether calcium supplementation is effective to prevent MetS.

Subject terms: Metabolic syndrome, Epidemiology

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is characterized by a constellation of interacting risk factors including impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), atherogenic dyslipidemia, elevated blood pressure, and visceral adiposity. These factors contribute to type 2 diabetes mellitus(T2D), cardiovascular disease (CVD), and other interrelated diseases1,2. The global incidence of MetS is continuing to rise over the past decades. The age-adjusted prevalence of MetS in the United States increased from 29.2% to 34.2% from 1999 to 20063. Asian populations also showed the similar trend4. Given its strong link to several chronic diseases, preventing MetS has been an important public health problem.

Calcium, an essential element, is the most abundant ion in human body. It is mainly stored in bones in the form of hydroxyapatite5. Serving as a ubiquitous signaling molecule with diverse role, calcium is also involved in a wide variety of physiological processes outside of the skeleton, including neuronal transmission, muscle contraction, organelle communication, hormone secretion, fertilization, and cell growth6. Previous evidence from meta-analysis indicated that calcium may reduce the risk of CVD and some types of cancer7,8. In the recent dozen years, a growing body of epidemiological studies evaluated the association between dietary calcium intake and the risk of MetS. However, the results of these studies were not consistent, and the overall conclusion still remains controversial.

To our knowledge, there is no meta-analysis has been performed before to study the putative association between dietary calcium intake and the risk of MetS. Hence, we conducted the current systematic review and meta-analysis in order to quantify the dose-response relationship between dietary calcium intake and MetS risk.

Results

Study selection

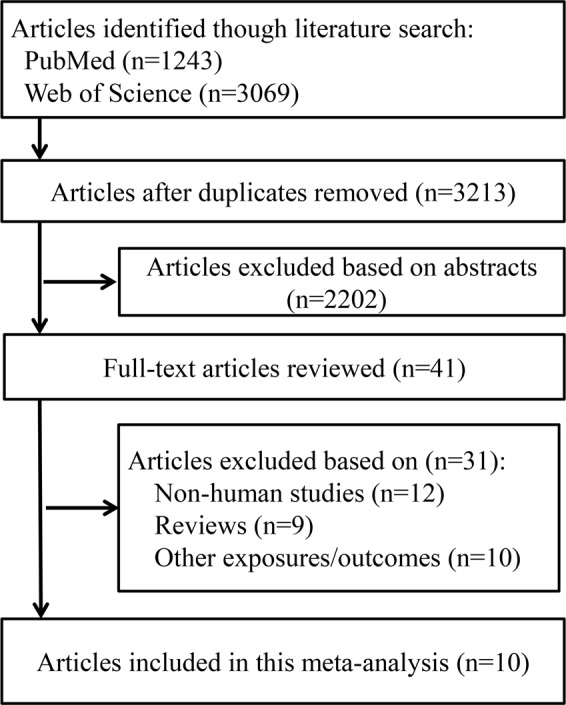

Figure 1 reports the bibliographic research process. In total, we identified 3,609 articles from Web of Science, and 1,243 articles from PubMed using our search strategy. Duplicate studies and studies that did not fulfill the inclusion criteria were excluded. Finally, we included 10 articles in our meta-analysis: 8 cross-sectional studies9–16 and 2 prospective cohort studies17,18.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search and study selection.

Table 1 shows the detailed characteristics of the 10 studies included in this meta-analysis. In total, these studies, which were published from 2005 through 2018, included 63,017 participants and 14,906 MetS cases aged 20 years and older. Five of the studies were performed in Korea10–12,15,16, two studies were conducted in United States13,18, and the others were performed in Saudi Arab9, France17, and Australia14, respectively. The definition of metabolic syndrome in all these studies either used the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) criteria or the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) ATP III criteria. Quality assessment for the studies yielded an average score of 7.7 (0.9) (Tables 2–3), and the quality of all the 10 studies was deemed moderate or high (score of 6 or above).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies (n = 10) regarding the association between dietary calcium intake and MetS.

| Author, Year | Study Name | Design | Location | Cases/Participants | Sex | Age (y) | Follow-up (y) | Assessment | Adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Daghri et al., 2013 | N/A | CS | Saudi | 72 (IDF)/185 | M/F | 19–60 | / | 24-h recall | Age, BMI, physical activity |

| Cho et al., 2009 | KNHANES 2001–2005 | CS | Korea | 2479 (NCEP)/9341 | M/F | >20 | / | 24-h recall | Age, BMI, marital status, education, alcohol, smoking, exercise, energy intake |

| Fumeron et al., 2011 | DESIR | PC | France | 667 (IDF) or 452 (NCEP)/3435 | M/F | 30–65 | 9 | FFQ | Sex, age, BMI, smoking, total fat intake, physical activity |

| Kim et al., 2017 | KNHANES 2008–2011 | CS | Korea | 2762 (NCEP)/14705 | M/F | >20 | / | 24-h recall | Total calorie intake, calcium supplement intake, age, living area, education, income, occupation, marital status, alcohol, smoking, exercise level, stature, BMI |

| Lim et al., 2017 | N/A | CS | Korea | 49 (NCEP)/143 | M/F | 58.0 ± 9.3 | / | 3-d recall | Age, sex, BMI, alcohol, smoking, exercise |

| Liu et al., 2005 | WHS | PC | US | 1039 (NCEP)/10066 | F | ≥45 | 8.8 | FFQ | Age, smoking, exercise, total calories, alcohol, multivitamin use, parental history of myocardial infarction |

| Moore-Schiltz et al., 2015 | NHANES | CS | US | 3579 (NCEP)/9148 | M/F | >20 | / | 24-h recall | Sex, age, ethnicity, education, income, total energy intake and fiber intake. |

| Pannu et al., 2016 | VHM | CS | Australia | 735 (IDF)/3403 | M/F | 15–75 | / | 24-h recall | Age, sex, country of birth, income, education, smoking, energy intake, physical activity, body weight, alcohol, dietary fiber |

| Shin et al., 2015 | MRCohort | CS | Korea | 2018 (NCEP)/6375 | M/F | >40 | / | FFQ | Age, education, marital status, exercise, glycemic load, intake of fat, fiber, sodium and energy |

| Shin et al., 2016 | KNHANES 2010–2012 | CS | Korea | 1506 (NCEP)/5946 | M | >20 | / | 24-h recall | Age, BMI, smoking, alcohol, income, education, residential area, physical activity, energy intake, eGFR, serum 25(OH)D level |

Abbreviations: BMI, Body mass index; CS, Cross-sectional; DESIR, Data from the Epidemiological Study on the Insulin Resistance; FFQ, Food frequency questionnaire; IDF, International Diabetes Federation; KNHANES, Korea National Health and Nutrition Survey; MRCohort, Multi-Rural Communities Cohort Study in Rural Communities; N/A, Not Available; NCEP National Cholesterol Education Program; PC, Perspective cohort; US, United States; VHM, Victorian Health Monitor; WHS, Women’s Health Study.

Table 2.

Quality assessment of included perspective cohort studies.

| Author, year | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Overall quality | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representative of exposed cohort | Selection of controls | Exposure ascertainment | No history of disease | Comparable on confounders | Outcome assessment | Adequate follow-up time (>5 years) | Follow-up rate (>80%) | ||

| Fumeron et al., 2011 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Liu et al., 2005 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

Table 3.

Quality assessment of included cross-sectional studies.

| Author, year | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Overall quality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representative of the sample | Sample size | Non-respondents | Exposure ascertainment | Comparable on confounders | Outcome assessment | Statistical test | ||

| Al-Daghri et al., 2013 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 |

| Cho et al., 2009 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| Kim et al., 2017 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 9 |

| Lim et al., 2017 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| Moore-Schiltz et al., 2015 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| Pannu et al., 2016 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| Shin et al., 2015 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 9 |

| Shin et al., 2016 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

Dietary calcium intake and MetS

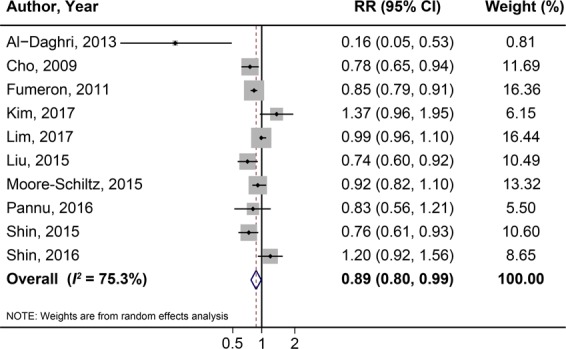

The RRs (with 95% CI) of MetS for highest vs. lowest dietary calcium intake are shown in Fig. 2. Compared to lowest calcium intake levels, the overall RR for MetS among the highest levels was 0.89 (95% CI: 0.80–0.99), and the heterogeneity was estimated high (I2 = 75.3%). Neither Egger’s test (P = 0.46) nor the funnel plot (Supplementary Fig. 1) revealed probability of publication bias.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of MetS for the highest vs. lowest category of dietary calcium intake.

Subgroup analyses

To identify the potential sources of heterogeneity, we performed subgroup analyses among all of the selected studies in order (Table 4). Notably, there is a significant association between dietary calcium intake and the risk of MetS only among female populations (RR: 0.74, 95% CI: 0.66–0.83), with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0). Moreover, association was more robust in the analysis based on cohort studies (RR: 0.82, 95% CI: 0.74–0.92; I2 = 31.3%) than that based on cross-sectional studies (RR: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.79–1.06; I2 = 73.7%). The associations were similar in other subgroups, including study location and the definition of MetS.

Table 4.

Subgroup analyses of dietary intake of calcium and risk of MetS.

| Subgroup | No. | RR (95% CI) | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design | |||

| Cohort | 2 | 0.82 (0.74–0.92) | 31.3 |

| Cross-sectional | 8 | 0.92 (0.79–1.06) | 73.7 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 5 | 1.06 (0.82–1.37) | 72.6 |

| Female | 5 | 0.74 (0.66–0.83) | 0.0 |

| Location | |||

| Asia | 6 | 0.92 (0.75–1.13) | 80.6 |

| US | 2 | 0.84 (0.68–1.03) | 63.1 |

| Definition of MetS | |||

| NCEP | 8 | 0.91 (0.81–1.01) | 72.2 |

| IDF | 3 | 0.69 (0.44 1.08) | 73.0 |

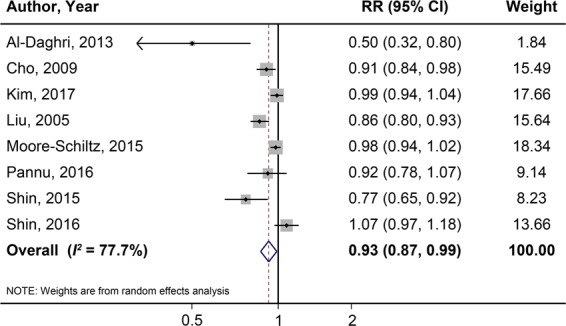

Dose-response analysis

For dose-response analysis, one cross-sectional study and one cohort study were excluded for lacking detailed data of dietary calcium intake level. We extracted data from the remaining 8 studies. The result showed that a 300 mg/day increase in dietary calcium intake was associated with a 7% lower risk of MetS (RR: 0.93; 95% CI: 0.87–0.99; I2 = 77.7%; see Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Dose-response meta-analysis of each 300 mg/day increment in dietary calcium intake and the risk of MetS.

Discussion

This systemic meta-analysis indicated that calcium intake may have a putative protective effect against MetS, which was also the most up-to-date epidemiological evidence. Assessment of dose-response effect showed a 300 mg/day increase in dietary calcium intake is significantly associated with a 7% decrease of MetS risk. In addition, subgroup analyses suggested the inverse association between dietary calcium intake and the risk of MetS was more robust in female population.

Metabolic syndrome is not a new medical condition. Eskil Kylin from Sweden reported the interesting observation of an aggregation of several metabolic risk factors19 in 1920s. However, the term “metabolic syndrome” was not formalized until 199820. Other terms that are used synonymously with MetS such as syndrome X21, the deadly quartet22, and insulin resistance syndrome23. Among many lifestyle factors, dietary behavior is quite important in the development of MetS. Previous epidemiological studies suggested that particular kinds of dairy food including milk, yogurt, as well as total dairy food intake were inversely related to MetS or some of its components24. As we know, calcium is a major component of diary food. Although the underlying mechanisms remain incomplete, scientists postulated calcium makes a great difference in the beneficial effect against MetS18,25.

Similar to dairy food consumption, dietary calcium intake is inversely related to T2D, body weight, hypertension, glucose homeostasis, and cardiovascular disease8,26–28. In recent years, an increasing number of evidence - in particular, epidemiological studies - has suggested a potential link between calcium and MetS. Unfortunately, their results were inconsistent and controversial. To our knowledge, this review and meta-analysis is the first one designed to systematically explore the association between dietary calcium intake and MetS, including dose-response analysis.

In view of the current study, the controversy among different epidemiological studies may be attributed to gender difference. According to the data extracted from the Insulin Resistance Syndrome (DESIR) cohort, Drouillet et al. found that with increasing quartiles of dietary calcium intake, insulin concentrations and blood pressures decreased and HDL-cholesterol increased in women during about 9-year follow-up. In men, however, higher level of calcium intake was only significantly associated with 0.4 mmHg decrease in diastolic blood pressure29. Such difference was observed in several populations after being stratified by sex. Moore-Schiltz’s team suggested that men may require more calcium intake than current recommendation to gain the potential protective effect against MetS13 after analyzing the data from the National Health and Nutrition Exami nation (NHANES). In addition, Cho et al. indicated menopause status may influence the protective effect of calcium intake on MetS10. They found that only in postmenopausal women, higher level of calcium intake was related to decreased MetS risk. However, these findings weren’t repeated successfully in subsequent research11. Notably, heterogeneous methods to measure calcium intake, such as food frequency questionnaire (FFQ), 24-hour or 3-day food recall, were used among these studies, which may lead to misclassification of exposure and inconsistencies in findings.

Although the exact mechanisms remain unclear, the protective effect of calcium consumption on MetS may be due to its ability in regulating energy metabolism and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and storage30. Accumulating evidence has suggested that imbalance of intercellular calcium homeostasis may play an important role in adipocyte function6. Increased cytosolic calcium promoted triglyceride accumulation as well as lipid storage through controlling de novo lipogenesis31. Additionally, unabsorbed calcium in the gastrointestinal tract isn’t without metabolic effects32. For example, calcium may form insoluble calcium soaps with fatty acids in gastrointestinal tract to influence fat and energy metabolism33.

This meta-analysis has several advantages. Above all, the primary advantage is that it is the first dose-response meta-analysis that quantitatively examined the relationship between dietary calcium intake and the risk of MetS. We also generated linear associations in addition to comparing the highest and lowest categories of calcium intake to increase the power of meta-analysis. Moreover, a common source of concern in meta-analysis is publication bias, but There was no evidence of publication bias in our study. Last but not least, relatively large number of study population enhanced the statistical power and made the subgroup analysis feasible.

On the other hand, the primary limitation of our analysis is that most of the selected studies were retrospective epidemiological studies. We also cannot exclude the possibility of confounding because of the observational nature of the included studies, although most of the original studies were adjusted for major potential confounders. Second, we also found significant heterogeneity in the result of the present study, and the sources of high heterogeneity cannot be totally explained by most of our subgroup analyses. However, significant differences in dietary calcium intake and MetS risk remained in several subgroups with lower heterogeneity, suggesting that the pooled results are likely reliable. Third, the number of included studies is relatively small. Besides, we might have neglected the missed unpublished reports, although every effort was made to estimate the unpublished risk. Finally, measurement and recall bias of dietary consumption assessment using food recall or FFQ would likely cause information bias.

In summary, this meta-analysis suggested that dietary calcium intake was inversely related to MetS risk, and such weak but significant association was supported by linear dose-response analysis. Subgroup analysis provided evidence that the beneficial effect may be significant among women, but less robust among men. In consideration of developing guidelines to prevent MetS by increasing the calcium-rich foods consumption, these findings may have important public health implications. However, the putative inverse association of dietary calcium intake with MetS risk still needs to be confirmed by larger prospective cohort studies and randomized clinical trials.

Methods

Search strategy

A comprehensive bibliographic research was performed on two databases - PubMed and Web of Science - for population-based studies published up to December 31th, 2018. Observational studies that examined the relationship between dietary intake of calcium and the risk of developing MetS were considered as potential suitable studies. The following terms were adopted as search strategy: calcium AND (“metabolic syndrome” OR “insulin resistance syndrome” OR “syndrome X”). To identify potential publications, we also examined the references of relevant reviews and meta-analysis. Bibliographic search was restricted to human studies without language limitation.

Selection of articles

Each included studies in this meta-analysis should fulfill the following four criteria: (1) population-based epidemiological studies, including cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies; (2) the exposure of interest is intake of dietary calcium; (3) the outcome is MetS; (4) either adjusted risk ratios, including relative risks (RRs) and odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs), or necessary data to calculate these values should be reported.

During the screening process, we excluded non-observational studies, studies that were not original (e.g., editorials, reviews, and commentaries), or not conducted in human subjects.

Data extraction

Two investigators (authors DH and XF) extracted the relevant data independently from the identified articles using a standard extraction form. From each identified study, we extracted the following information: study characteristics (the study name, design, the publication year, name of first author, the country of data collection, and the number of follow-up years for cohort studies); the participants’ characteristics (sex, age, population size, and the incidence or prevalence of MetS); the method used to assess nutrient intakes; and the definition of metabolic syndrome measurements.

Quality assessment of included studies was conducted according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) that gives a maximum of nine points for each study34, while cross-sectional studies were evaluated using a modified version of NOS with a highest score of ten35. Scores of 0–3, 4–6, and 7–9 were interpreted as low, moderate, or high quality, respectively.

Statistical analysis

In the present study, we used RR with 95% CI to estimate risk; in addition, ORs (for case-control or cross-sectional studies) were used to directly determine the relative risk. Before inclusion in the overall analysis, we pooled the results that were stratified by sex by conducting a fixed effects meta-analysis.

We first pooled these RRs sequentially using the DerSimonian and Laird random effects method, taking both within-study and between-study variability into account36. Prospective and retrospective studies were analyzed separately in the main meta-analysis. To determine the sources causing between-study heterogeneity, we also performed subgroup analyses based on sex, location, study design, and the definition of MetS.

Dose-response analysis for calcium intake and MetS were conducted according to the method described by Greenland and Longnecker37 and using the publicly available Stata command written by Orsini et al.38. In accordance with this method, studies with three or more exposure categories were included. If the number of cases or participants was not available, we used variance-weighted least-squares regression to estimate risk39. If neither the median nor the mean was given in the original study, we used the categorical midpoint instead. If the lowest and/or highest category was open-ended, the midpoint of the category was determined by assuming that the width of the category is the same as the next adjacent category.

We used I² tests for across studies comparison. The values of 25%, 50%, and 75% were interpreted as low, moderate, and high degrees of heterogeneity, respectively40. Publication bias was evaluated by visually inspecting a contour-enhanced funnel plot and by performing Egger’s linear regression test (with significance defined as P < 0.10)41. Stata 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) was used to perform all statistical analyses. All statistical tests were two-sided and differences with a P-value < 0.05 were considered significant except where noted otherwise.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by research grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81573155, 31900835) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2019M650139).

Author contributions

D.H. and X.F. originated and designed the study. D.S. and M.H. searched the databases. L.H. and D.S. contributed to the data extraction and data analyses. D.Z. and Y.Z. assisted with literature selection. D.H. and X.F. drafted the manuscript. R.Z. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-55507-x.

References

- 1.Mottillo S, et al. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1113–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberti KG, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–1645. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mozumdar A, Liguori G. Persistent increase of prevalence of metabolic syndrome among U.S. adults: NHANES III to NHANES 1999–2006. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:216–219. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim S, et al. Increasing prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Korea: the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey for 1998–2007. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1323–1328. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laine M, Weckstrom M, Vuolteenaho O, Arjamaa O. Effect of ryanodine on atrial natriuretic peptide secretion by contracting and quiescent rat atrium. Pflugers Arch. 1994;426:276–283. doi: 10.1007/BF00374782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arruda AP, Hotamisligil GS. Calcium Homeostasis and Organelle Function in the Pathogenesis of Obesity and Diabetes. Cell Metab. 2015;22:381–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asemi Z, Saneei P, Sabihi SS, Feizi A, Esmaillzadeh A. Total, dietary, and supplemental calcium intake and mortality from all-causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25:623–634. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A. Dietary calcium intake and risk of stroke: a dose-response meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:951–957. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.052449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Daghri NM, et al. Selected dietary nutrients and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in adult males and females in Saudi Arabia: a pilot study. Nutrients. 2013;5:4587–4604. doi: 10.3390/nu5114587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho GJ, et al. Calcium intake is inversely associated with metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women: Korea National Health and Nutrition Survey, 2001 and 2005. Menopause. 2009;16:992–997. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31819e23cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim MK, et al. Associations of dietary calcium intake with metabolic syndrome and bone mineral density among the Korean population: KNHANES 2008-2011. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28:299–308. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim HS, Shin EJ, Yeom JW, Park YH, Kim SK. Association between Nutrient Intake and Metabolic Syndrome in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Clin Nutr Res. 2017;6:38–46. doi: 10.7762/cnr.2017.6.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore-Schiltz L, Albert JM, Singer ME, Swain J, Nock NL. Dietary intake of calcium and magnesium and the metabolic syndrome in the National Health and Nutrition Examination (NHANES) 2001-2010 data. Br J Nutr. 2015;114:924–935. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515002482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pannu PK, Zhao Y, Soares MJ, Piers LS, Ansari Z. The associations of vitamin D status and dietary calcium with the metabolic syndrome: an analysis of the Victorian Health Monitor survey. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20:1785–1796. doi: 10.1017/S1368980016001609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shin SK, et al. The cross-sectional relationship between dietary calcium intake and metabolic syndrome among men and women aged 40 or older in rural areas of Korea. Nutr Res Pract. 2015;9:328–335. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2015.9.3.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shin BR, Choi YK, Kim HN, Song SW. High dietary calcium intake and a lack of dairy consumption are associated with metabolic syndrome in obese males: the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010 to 2012. Nutr Res. 2016;36:518–525. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fumeron F, et al. Dairy consumption and the incidence of hyperglycemia and the metabolic syndrome: results from a french prospective study, Data from the Epidemiological Study on the Insulin Resistance Syndrome (DESIR) Diabetes Care. 2011;34:813–817. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu S, et al. Dietary calcium, vitamin D, and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in middle-aged and older U.S. women. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2926–2932. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.12.2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kylin E. Studien uber das Hypertonie-Hyperglyka “mie-Hyperurika” miesyndrom. Zentralblatt fuer Innere Medizin. 1923;44:105–127. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15:539–553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reaven GM. Banting lecture 1988. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988;37:1595–1607. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.12.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan NM. The deadly quartet. Upper-body obesity, glucose intolerance, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:1514–1520. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1989.00390070054005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeFronzo RA, Ferrannini E. Insulin resistance. A multifaceted syndrome responsible for NIDDM, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Care. 1991;14:173–194. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.3.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee M, Lee H, Kim J. Dairy food consumption is associated with a lower risk of the metabolic syndrome and its components: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. 2018;120:373–384. doi: 10.1017/S0007114518001460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Major GC, et al. Recent developments in calcium-related obesity research. Obes Rev. 2008;9:428–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davies KM, et al. Calcium intake and body weight. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:4635–4638. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.12.7063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jayedi, A. & Zargar, M. S. Dietary calcium intake and hypertension risk: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Clin Nutr (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Villegas R, et al. Dietary calcium and magnesium intakes and the risk of type 2 diabetes: the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1059–1067. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drouillet P, et al. Calcium consumption and insulin resistance syndrome parameters. Data from the Epidemiological Study on the Insulin Resistance Syndrome (DESIR) Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;17:486–492. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zemel MB. Regulation of adiposity and obesity risk by dietary calcium: mechanisms and implications. J Am Coll Nutr. 2002;21:146S–151S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2002.10719212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zemel MB, Shi H, Greer B, Dirienzo D, Zemel PC. Regulation of adiposity by dietary calcium. FASEB J. 2000;14:1132–1138. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.9.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soares MJ, Murhadi LL, Kurpad AV, Chan She Ping-Delfos WL, Piers LS. Mechanistic roles for calcium and vitamin D in the regulation of body weight. Obes Rev. 2012;13:592–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.00986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Denke MA, Fox MM, Schulte MC. Short-term dietary calcium fortification increases fecal saturated fat content and reduces serum lipids in men. J Nutr. 1993;123:1047–1053. doi: 10.1093/jn/123.6.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wells, G. A. et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessingthe quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses, www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (2011).

- 35.Herzog R, et al. Are healthcare workers’ intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fang X, et al. Dietary intake of heme iron and risk of cardiovascular disease: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greenland S, Longnecker MP. Methods for trend estimation from summarized dose-response data, with applications to meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:1301–1309. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orsini N, Bellocco R, Greenland S. Generalized least squares for trend estimation of summarized dose-response data. Stata Journal. 2006;6:40–57. doi: 10.1177/1536867X0600600103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fang, X. et al. Quantitative association between body mass index and the risk of cancer: A global Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int J Cancer (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Jackson D, White IR, Riley RD. Quantifying the impact of between-study heterogeneity in multivariate meta-analyses. Stat Med. 2012;31:3805–3820. doi: 10.1002/sim.5453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.