Abstract

Purpose

Congenital aplasia of vas deferens (CAVD) is an atypical form of cystic fibrosis (CF) and causes obstructive azoospermia and male infertility. Compound heterozygous variants of CFTR are the main cause of CAVD. However, most evidence comes from genetic screening of sporadic cases and little is from pedigree analysis. In this study, we performed analysis in a Chinese pedigree with two CAVD patients in order to determine the genetic cause of this familial disorder.

Methods

In the present study, we performed whole-exome sequencing and co-segregation analysis in a Chinese pedigree involving two patients diagnosed with CAVD.

Results

We identified a rare frameshift variant (NM_000492.3: c.50dupT;p.S18Qfs*27) and a frequent CBAVD-causing variant (IVS9-TG13-5T) in both patients. The frameshift variant introduced a premature termination codon and was not found in any public databases or reported in the literature. Co-segregation analysis confirmed these two variants were in compound heterozygous state. The other male members, who harbored the frameshift variant and benign IVS9-7T allele, did not have any typical clinical manifestations of CF or CAVD.

Conclusion

Our findings may broaden the mutation spectrum of CFTR in CAVD patients and provide more familial evidence that the combination of a mild variant and a severe variant in trans of CFTR can cause vas deferens malformation.

Keywords: CFTR, CBAVD, Compound heterozygous, Chinese pedigree

Introduction

The majority of males with cystic fibrosis (CF) are infertile because of obstructive azoospermia caused by congenital bilateral aplasia of vas deferens (CBAVD, OMIM: 277180) [1]. CBAVD is the most common subtype of congenital aplasia of vas deferens (CAVD) and may occur in an isolated form or in company with other typical manifestations of CF. Another less common subtype, congenital unilateral aplasia of vas deferens (CUAVD), was found in 0.5~1% of males [2]. It has been estimated that 1~2% male infertility [3] and nearly one quarter of obstructive azoospermia [4] were caused by this reproductive disorder.

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene (CFTR, OMIM: 602421) is the main genetic cause of CAVD. It encodes a transmembrane Cl− channel responsible for anion transport and fluid reabsorption, and is widely expressed in the apical membrane cells of efferent ducts in the lung, pancreas, sweat glands, and vas deferens [5]. The dysfunctions of CFTR, caused by many types of genetic variants or improper molecular signaling, may result in abnormal fluid reabsorption in the efferent ducts in male reproductive system and the obstruction of the vas deferens [6]. Adhesion G protein–coupled receptor G2 gene (ADGRG2, OMIM: 300572) on chromosome X is an additional causative gene of CBAVD identified [7] and replicated by recent studies [8–10]. Males with hemizygous variants of ADGRG2 manifested obstructive infertility phenotypes similar to that observed in knock-out mice [11]. Further experiments showed ADGRG2 and CFTR may function in a complex formation that was critical for Cl−/acid-base homeostasis and fluid reabsorption in the efferent ducts [12]. However, the exact mechanism of CBAVD still remains elusive.

Variants in CFTR are the main cause of CAVD and CF, and more than 2000 variants have so far been identified and documented in the CFTR2 database (https://www.cftr2.org/). It was estimated by meta-analyses that 78% of CBAVD [3] and 46% of CUAVD [13] patients harbor at least one variant of CFTR but the frequency of carrying CFTR variants varied between different populations. Several variants including p.F508del, p.M470V, p.R117H, and c.1210-7_1210-6delTT (IVS9-5T, formerly known as IVS8-5T) were found in a high frequency in CAVD patients [14]. The bi-allelic combinations of variants with different severities may lead to different clinical manifestations [15, 16]. In general, CAVD patients without any other manifestations of CF are caused by compound heterozygous variants composed of one mild and one severe variant or two mild variants in trans [14]. However, most of the bi-allelic variants were reported in sporadic cases lacking familial evidence of inheritance pattern, and only a few were found in pedigrees [17, 18].

Here, we reported a Chinese pedigree with two congenital aplasia of vas deferens (CAVD) patients who carried compound heterozygous variants of CFTR, one rare frameshift variant (NM_000492.3: c.50dupT;p.S18Qfs*27) inherited from the father and one mild variant (NM_000492.3: c.1210-33_1210-6GT[13]T[5], also known as IVS9-TG13-5T) inherited from the mother.

Materials and methods

CAVD pedigree

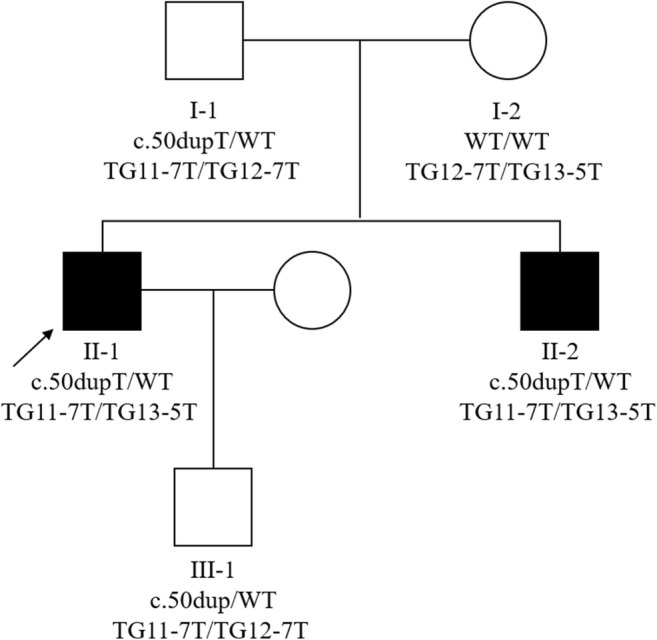

A Chinese pedigree with two CAVD patients were recruited from the Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University (Fig. 1). The proband was 28 years old and referred to the hospital for having been infertile for 2 years after marriage. Physical examination showed an impalpable vas deferens of the left side and an extremely thin vas deferens of the right side. Semen examination showed a total absence of sperm, decreased volume (0.5 mL) and pH value (5.5), and normal liquefaction time (30 min), while percutaneous epididymal sperm aspiration (PESA) showed motile sperms in the epididymis. The patient had normal karyotype but no microdeletions in the Y chromosome, normal serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH, 4.4 mIU/mL), luteinizing hormone (LH, 7.4 mIU/mL), and total testosterone (TT, 21.86 nmol/L). He had two normal kidneys. Therefore, this proband was diagnosed with congenital unilateral aplasia of vas deferens (CUAVD). The other patient, 25 years old, claimed infertility for 1 year after marriage. Physical examination showed impalpable bilateral vas deferens. The results of other examinations were similar to his brother (semen volume, 0.5 mL; pH, 6.0; liquefaction time, 25 min; PESA: motile sperms; serum FSH, 10.9 mIU/mL; LH, 8.0 mIU/mL; TT, 20.1 nmol/L). The other symptoms of CF were not found and bilateral normal kidneys were present. Thus, he was diagnosed with CBAVD. Both of the patients received in vitro fertilization treatment in our hospital and gave birth to a boy and a girl, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Pedigree structure of the CBAVD family. Black squares indicate CBAVD patients. Arrow indicates the proband. WT wild type

We collected the peripheral blood samples from both patients, their parents and the son of the proband and extracted the genomic DNA. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University.

Whole-exome sequencing and validation

Whole-exome sequencing was performed on both patients to identify the genetic cause. The exomes were captured by SureSelect Human All Exon V5 Enrichment kit (Agilent, USA) and parallel-sequenced on the Illumina Hiseq 4000 platform (Illumina, USA). Burrows-Wheeler Aligner v0.7.15 was used to map the reads to human reference genome (hg19), and GATK v3.3.0 best practice was performed to detect SNPs and indels. Finally, SnpEff was used to annotate all the variants.

Two variants of CTFR were validated by Sanger sequencing in all family members with available DNA using the following primers: forward 5′-ACGTAACAGGAACCC GACTA-3′ and reverse 5′-GTGCCAAGAAGACAATCAAG-3′ for c.50dupT, and forward 5′-GCTTTGAAAGAGGAGGAT-3′ and reverse 5′-CAAGACACTACACCC ATAC-3′ for c.1210-33_1210-6GT[13]T[5].

Results

By whole-exome sequencing, we identified two heterozygous variants in CFTR shared by both patients. One was a frameshift variant (NM_000492.3: c.50dupT;p.S18Qfs*27, rs397508714) that introduced a premature termination codon downstream the variant and led to protein truncation. The variant was totally absent from 1000Genomes (http://www.internationalgenome.org) or ExAC (http://exac.broadinstitute.org), and was not documented in the CFTR2 database or reported in the literature. It had an extremely low frequency of 0.009% as documented by the Kaviar database (http://db.systemsbiology.net/kaviar/) which incorporates high-throughput sequencing data from various projects. The other heterozygous variant was NM_000492.3: c.1210-33_1210-6GT[13]T[5] (IVS9-TG13-5T for short, formerly known as IVS8-TG13-5T) in the boundary between the 9th intron and 10th exon, a known pathogenic variant of CBAVD. We did not find any non-synonymous variants in ADGRG2.

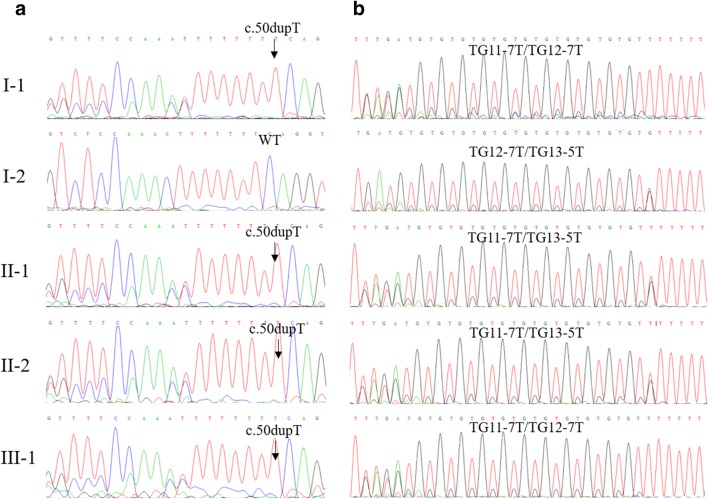

Familial segregation analysis using Sanger sequencing confirmed that these two variants in the patients were in compound heterozygous state (Fig. 1). For the T insertion, the patients and the father had a heterozygous variant and the mother was wild-type (Fig. 2a). For the IVS9-(TG)m(T)n alleles in both chromosomes, the patients were TG11-7T/TG13-5T, the father was TG11-7T/TG12-7T while the mother was TG12-7T/TG13-5T (Fig. 2b). Therefore, the patients inherited the T insertion from the father and TG13-5T from the mother. Additionally, the son of the proband carried a heterozygous T insertion and had TG11-7T/TG12-7T on each chromosome.

Fig. 2.

Validation of both variants of CFTR among family members by Sanger sequencing

Discussion

Although almost all of CF males are infertile due to obstructive azoospermia and CAVD is regarded as atypical form of CF, CAVD can occur in isolation without any typical manifestations of CF. This may be caused by the difference in alternative mRNA splicing or sensitivity to dysfunctional CFTR protein between various organs [19, 20]. Therefore, the mutation spectrums of typical CF and CAVD are distinguished.

The poly-T polymorphism in intro 9 of CFTR, IVS9-(T)n, is commonly found in CAVD patients. IVS9-5T, the shortest form of (T)n, may alter the splicing pattern of exon 10 and result in the skipping of exon 10. It is considered a pathogenic variant with incomplete penetrance [15]. (TG)m, another polymorphism adjacent to (T)n, can increase the penetrance by reducing the splicing efficiency of exon 10, especially in the presence of longer TG repeats in cis with shorter T repeats. Analysis of CFTR transcripts showed that TG13-5T allele had the lowest level (less than 10%) of exon 10 intact, followed by TG12-5T [21]. The other (TG)m(T)n polymorphisms, including TG12-7T and TG11-7T that are the most common alleles in the general population, had high exon 10 splicing efficiency [21]. The skipping of exon 10 on both chromosomes results in dysfunctional CFTR protein without channel activity and causes the malformation of the vas deferens. However, CAVD patients with IVS9-TG13-5T may not have lung problems. It was found that, in bronchial epithelial cells, even a low level of normal CFTR transcripts was sufficient for the maintenance of normal airway function, suggesting a high tolerance of lung tissue to dysfunctional CFTR protein [22].

In CAVD patients, IVS9-TG13-5T allele is usually accompanied with a mild or severe variant in trans. Radpour et al. detected one mutation (missense, nonsense, in-frame deletion, or splicing site) combined with one TG13-5T allele in 28 out of 112 CBAVD patients and with one TG12-5T allele in 4 patients [21]. Groman et al. found the combination of a TG13-5T allele and a severe CFTR mutation had 34.0 times of pathogenicity than TG11-5 T [23].

In present study, we identified a rare mutation (NM_000492.3: c.44_45insT;p.S18Qfs*27) leading to a truncated protein of which only a small proportion of the N-terminal retained. Co-segregation analysis confirmed that both patients harbored one frameshift variant in trans with the IVS9-TG13-5T allele, which may result in extremely low expression of functional CFTR protein and cause CAVD. This frameshift, causing a null variant (PVS1) at extremely low frequency in public databases (PM2), being in trans with a known pathogenic variant IVS9-TG13-5T (PM3) and in co-segregation with CAVD in the family with two affected patients (PP1), should be classified as a pathogenic variant according to the ACMG guideline [24] and considered as a severe variant. Similar pathogenicity class related to this variant has been given in the Varsome database (https://varsome.com/variant/hg19/NM_000492.3%3Ac.44_45insT). The father and the son of the proband, although also having the frameshift variant, carried the TG11-7T/TG12-7T genotype. They did not have any clinical manifestations of CF or CAVD as they had only one copy of severe variant but no IVS9-5T allele. This is in accordance with previous conclusions that only one copy of pathogenic variant of CFTR is not sufficient to cause CAVD and that the combination of a frequent variant with a rare variant may be the main cause of this disorder [14, 25]. However, most of previous studies were performed in sporadic cases and the compound heterozygous state of two CFTR variants they identified cannot be confirmed if the DNA samples from parents were unavailable. Together with the present study, several studies have reported evidence from pedigrees comprising multiple CAVD patients and confirmed the compound heterozygous state of CFTR variants [18]. The pedigrees may provide more evidence to classify the pathogenicity class of the variants identified.

In addition to the aplasia of vas deferens, renal agenesis was not found in both patients. Renal agenesis is a usual complication of CAVD and is more frequent in CUAVD (26.8%) than in CBAVD (6.7%) [13]. However, there was significantly a lower frequency of CFTR variant in CUAVD patients with renal agenesis than in those without renal agenesis [26], indicating that CFTR variants may not be the genetic cause of renal agenesis in CAVD patients.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we identified a rare frameshift variant in trans with the IVS9-TG13-5T allele of CFTR in a Chinese pedigree with two CAVD patients. Our findings have broadened the CAVD-associated mutation spectrum of CFTR and provided more familial evidence of the pathogenicity of compound heterozygous variants of CFTR.

Funding information

This work was supported by funds from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 81671448 and 81871152).

Compliance with ethical standards

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Bin Ge and Mingzhe Zhang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Hongjun Li, Email: lihongjun@pumch.cn.

Binbin Wang, Email: wbbahu@163.com.

References

- 1.Chillon M, Casals T, Mercier B, Bassas L, Lissens W, Silber S, Romey MC, Ruiz-Romero J, Verlingue C, Claustres M, et al. Mutations in the cystic fibrosis gene in patients with congenital absence of the vas deferens. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(22):1475–1480. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506013322204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiske WH, Salzler N, Schroeder-Printzen I, Weidner W. Clinical findings in congenital absence of the vasa deferentia. Andrologia. 2000;32(1):13–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2000.tb02859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu J, Chen Z, Ni Y, Li Z. CFTR mutations in men with congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens (CBAVD): a systemic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(1):25–35. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wosnitzer MS, Goldstein M. Obstructive azoospermia. Urol Clin N Am. 2014;41(1):83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Sullivan BP, Freedman SD. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1891–1904. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nistal M, Riestra ML, Galmes-Belmonte I, Paniagua R. Testicular biopsy in patients with obstructive azoospermia. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23(12):1546–1554. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199912000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patat O, Pagin A, Siegfried A, Mitchell V, Chassaing N, Faguer S, Monteil L, Gaston V, Bujan L, Courtade-Saidi M, Marcelli F, Lalau G, Rigot JM, Mieusset R, Bieth E. Truncating mutations in the adhesion g protein-coupled receptor G2 gene ADGRG2 cause an X-linked congenital bilateral absence of vas deferens. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99(2):437–442. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang B, Wang J, Zhang W, Pan H, Li T, Liu B, Li H, Wang B. Pathogenic role of ADGRG2 in CBAVD patients replicated in Chinese population. Andrology. 2017;5(5):954–957. doi: 10.1111/andr.12407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan MJ, Pollock N, Jiang H, Castro C, Nazli R, Ahmed J, Basit S, Rajkovic A, Yatsenko AN. X-linked ADGRG2 mutation and obstructive azoospermia in a large Pakistani family. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):16280. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34262-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan P, Liang ZK, Liang H, Zheng LY, Li D, Li J, Zhang J, Tian J, Lai LH, Zhang K, He ZY, Zhang QX, Wang WJ. Expanding the phenotypic and genetic spectrum of Chinese patients with congenital absence of vas deferens bearing CFTR and ADGRG2 alleles. Andrology. 2019;7(3):329–340. doi: 10.1111/andr.12592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies B, Baumann C, Kirchhoff C, Ivell R, Nubbemeyer R, Habenicht UF, Theuring F, Gottwald U. Targeted deletion of the epididymal receptor HE6 results in fluid dysregulation and male infertility. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(19):8642–8648. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.19.8642-8648.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sobel RE, Bate A, Marshall J, Haynes K, Selvam N, Nair V, Daniel G, Brown JS, Reynolds RF. Do FDA label changes work? Assessment of the 2010 class label change for proton pump inhibitors using the Sentinel System’s analytic tools. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018;27(3):332–339. doi: 10.1002/pds.4392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai H, Qing X, Niringiyumukiza JD, Zhan X, Mo D, Zhou Y, Shang X. CFTR variants and renal abnormalities in males with congenital unilateral absence of the vas deferens (CUAVD): a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Genet Med. 2019;21(4):826–836. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0262-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Souza DAS, Faucz FR, Pereira-Ferrari L, Sotomaior VS, Raskin S. Congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens as an atypical form of cystic fibrosis: reproductive implications and genetic counseling. Andrology. 2018;6(1):127–135. doi: 10.1111/andr.12450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuppens H, Lin W, Jaspers M, Costes B, Teng H, Vankeerberghen A, Jorissen M, Droogmans G, Reynaert I, Goossens M, Nilius B, Cassiman JJ. Polyvariant mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator genes. The polymorphic (Tg)m locus explains the partial penetrance of the T5 polymorphism as a disease mutation. J Clin Invest. 1998;101(2):487–496. doi: 10.1172/JCI639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noone PG, Knowles MR. ‘CFTR-opathies’: disease phenotypes associated with cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator gene mutations. Respir Res. 2001;2(6):328–332. doi: 10.1186/rr82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng JR, Zhang YN, Wu X, Yang XJ, Chen ST, Ma GC, Luo SG, Zhang Y. Homozygous 5T alleles, clinical presentation and genetic analysis within a family with congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2018;98(18):1414–1418. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0376-2491.2018.18.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang B, Wang X, Zhang W, Li H, Wang B. Compound heterozygous mutations in CFTR causing CBAVD in Chinese pedigrees. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2018;6(6):1097–1103. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mak V, Jarvi KA, Zielenski J, Durie P, Tsui LC. Higher proportion of intact exon 9 CFTR mRNA in nasal epithelium compared with vas deferens. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6(12):2099–2107. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.12.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuppens H, Cassiman JJ. CFTR mutations and polymorphisms in male infertility. Int J Androl. 2004;27(5):251–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2004.00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radpour R, Gourabi H, Gilani MA, Dizaj AV. Molecular study of (TG)m(T)n polymorphisms in Iranian males with congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens. J Androl. 2007;28(4):541–547. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.106.002337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chu CS, Trapnell BC, Curristin SM, Cutting GR, Crystal RG. Extensive posttranscriptional deletion of the coding sequences for part of nucleotide-binding fold 1 in respiratory epithelial mRNA transcripts of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene is not associated with the clinical manifestations of cystic fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 1992;90(3):785–790. doi: 10.1172/JCI115952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groman JD, Hefferon TW, Casals T, Bassas L, Estivill X, Des Georges M, Guittard C, Koudova M, Fallin MD, Nemeth K, Fekete G, Kadasi L, Friedman K, Schwarz M, Bombieri C, Pignatti PF, Kanavakis E, Tzetis M, Schwartz M, Novelli G, D’Apice MR, Sobczynska-Tomaszewska A, Bal J, Stuhrmann M, Macek M, Jr, Claustres M, Cutting GR. Variation in a repeat sequence determines whether a common variant of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene is pathogenic or benign. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74(1):176–179. doi: 10.1086/381001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL, Committee ALQA. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lissens W, Mercier B, Tournaye H, Bonduelle M, Ferec C, Seneca S, Devroey P, Silber S, Van Steirteghem A, Liebaers I. Cystic fibrosis and infertility caused by congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens and related clinical entities. Hum Reprod. 1996;11(Suppl 4):55–78. doi: 10.1093/humrep/11.suppl_4.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casals T, Bassas L, Egozcue S, Ramos MD, Gimenez J, Segura A, Garcia F, Carrera M, Larriba S, Sarquella J, Estivill X. Heterogeneity for mutations in the CFTR gene and clinical correlations in patients with congenital absence of the vas deferens. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(7):1476–1483. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.7.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]