Abstract

Purpose:

Previous studies have suggested that higher circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels are associated with decreased colorectal cancer (CRC) risk and improved survival. However, the influence of vitamin D status on disease progression and patient survival remains largely unknown for patients with advanced or metastatic CRC.

Experimental design:

We prospectively collected blood samples in 1,041 patients with previously untreated advanced or metastatic CRC participating in a randomized phase III clinical trial of first-line chemotherapy plus biologic therapy. We examined the association of baseline plasma 25(OH)D levels with overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS). Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and confidence intervals (CIs), adjusted for prognostic factors and confounders.

Results:

At study entry, 63% of patients were vitamin D deficient (<20 ng/mL) and 31% were vitamin D insufficient (20 to <30 ng/mL). Higher 25(OH)D levels were associated with an improvement in OS and PFS (Ptrend=0.0009 and 0.03, respectively). Compared to patients in the bottom quintile of 25(OH)D (≤10.8 ng/mL), those in the top quintile (≥24.1 ng/mL) had a multivariable-adjusted HR of 0.66 (95% CI, 0.53 to 0.83) for OS and 0.81 (95% CI, 0.66 to 1.00) for PFS. The improved survival associated with higher 25(OH)D levels was consistent across patient subgroups of prognostic patient and tumor characteristics.

Conclusions:

In this large cohort of patients with advanced or metastatic CRC, higher plasma 25(OH)D levels were associated with improved OS and PFS. Clinical trials assessing the benefit of vitamin D supplementation in CRC patients are warranted.

Keywords: 25-hydroxyvitamin D, colorectal cancer, survival

Introduction

Vitamin D deficiency is increasingly prevalent in the United States. A national survey showed that only 23% of Americans have serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels ≥30 ng/mL, the level required for optimum health (1). Most foods, unless they are fortified, are poor sources of vitamin D. Thus, exposure to type B ultraviolet (UV-B) radiation is the major determinant of vitamin D status in humans. Over the past decades, skin cancer prevention campaigns that recommend avoidance of sun exposure, coupled with more daylight hours spent indoors and increasing prevalence of obesity, may have contributed to the rising prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, particularly in northern latitudes (2).

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States (3). Among CRC patients, only 39% are diagnosed at an early stage with a 5-year survival rate of 90%; the survival rates decline to 71% and 14% for locally advanced and metastatic stages, respectively (4). Vitamin D has antineoplastic properties (5), and CRC patients are prone to vitamin D deficiency (6–9). Prospective epidemiologic studies consistently show an association between higher vitamin D status and improved survival among patients with all stages of CRC (8,10–13). However, the influence of vitamin D status on cancer progression and survival remains largely unknown for patients with advanced or metastatic CRC. We therefore examined the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and the association between baseline plasma 25(OH)D levels and survival outcome in a large cohort of patients with previously untreated advanced or metastatic CRC enrolled in a randomized phase III clinical trial of first-line chemotherapy plus biologic therapy.

Methods

Study population

Patients in this study were drawn from the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB; now a part of the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology) and SWOG 80405 (Alliance) trial, which was designed in collaboration with the National Cancer Institute to compare various combinations of chemotherapy [leucovorin, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin (mFOLFOX6) or leucovorin, fluorouracil, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) per investigator’s choice] with biologic therapy as first-line treatment of advanced and metastatic CRC: (1) chemotherapy plus cetuximab; (2) chemotherapy plus bevacizumab; and (3) chemotherapy plus cetuximab and bevacizumab. Patients were enrolled at centers across the National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN) in the United States and Canada. Eligible patients had pathologically confirmed, unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic CRC. Patients had to be candidates for either mFOLFOX6 or FOLFIRI regimens without known contraindications for bevacizumab or cetuximab therapy. Patients were required to have had no previous treatment for advanced or metastatic disease but may have received prior adjuvant treatment (≤6 months) that must have concluded >12 months before recurrence. Institutional review board approval was required at all participating centers and all participating patients provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects (CIOMS).

Full details and results of the treatment trial have been described previously (14). In brief, the trial was initiated in September 2005 with a total of 2,326 patients randomized to the three treatment arms. The lack of efficacy of EGFR antibodies in KRAS-mutant tumors (15) and failure of the chemotherapy and dual antibody combination in other studies (16,17) resulted in a pivotal amendment restricting eligibility to patients with confirmed KRAS wild-type tumors in November 2008 and closure of the dual antibody arm in September 2009. Although the final analysis cohort for the treatment trial was comprised of only the 1,131 KRAS wild-type patients randomized to the bevacizumab-chemotherapy arm or the cetuximab-chemotherapy arm, the study population for this vitamin D study was drawn from all three arms of CALGB/SWOG 80405 (Alliance). Among the 2,326 patients, 1,041 provided blood samples at study entry for biomarker research and had 25(OH)D levels measured (Supplementary Fig. S1). We compared baseline characteristics of these 1,041 patients with the entire population as well as the final analysis cohort for the treatment trial, and did not detect any appreciable differences (Supplementary Table S1). Moreover, patients in both populations experienced similar overall survival (OS) (median=28.8 and 31.2 months, respectively).

Plasma 25(OH)D assessment

SWOG oversaw specimen biobanking and distribution of samples for correlative research. To measure 25(OH)D, plasma samples were sent by overnight delivery to Heartland Assays (Ames, IA) for radioimmunoassay (18). Masked quality control samples were interspersed among the samples, and all laboratory personnel were blinded to survival data. The mean intra-assay coefficient of variation was 10%, and National Institute of Standards and Technology reference ranges (±SDs) were met as follows: 23.3±1.8 ng/mL for concentration 1, 14.6±1.3 ng/mL for concentration 2, 38.6±2.4 ng/mL for concentration 3, and 33.1±2.6 ng/mL for concentration 4.

Clinical outcomes

The primary endpoint of OS was calculated from time of study entry to death or last known follow-up for those without reported death. The secondary endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from study entry to first documented progression or death. Patients alive without documented progression were censored for PFS at the most recent disease assessment. Disease assessment was done by treating investigators and was not blinded.

Covariates

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from weight and height measured at study entry (weight in kilograms divided by square of height in meters). At enrollment, patients were given the option of inclusion in the diet and lifestyle companion study. Within the first month of enrollment, 774 of the 1,041 patients completed a questionnaire capturing diet and lifestyle habits at diagnosis of advanced or metastatic disease, including a validated semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire that consisted of 131 food items plus vitamin and mineral supplement use. A physical activity score, expressed in metabolic equivalent-hours/week, was derived by multiplying the time spent on each activity per week by the typical energy expenditure for that activity and then summing contributions from all activities. Dietary vitamin D and calcium intakes were computed by multiplying the frequency of consumption of each food by its nutrient content and summing contributions from all foods.

Patients who consented to be tested for KRAS agreed to submit two archival paraffin-embedded tumor tissue sections and one histology reference slide or one paraffin-embedded tumor block of previously resected primary colorectal tumor and/or a metastatic tumor deposit. KRAS and NRAS mutation status was determined by BEAMing (beads, emulsion, amplification, magnetics; Hamburg, Germany) technology.

Statistical analyses

Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan–Meier method (19), and statistical significance was measured using the log-rank test (20). Cox proportional hazards models (21) were used to examine the association of 25(OH)D levels with OS and PFS. The assumption of proportional hazards was tested and met by evaluating a time-dependent variable, which was the product of 25(OH)D level and time. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated according to (1) quintile of 25(OH)D, with the lowest quintile as the reference group; and (2) clinical category of 25(OH)D (<10, 10 to <20, or ≥20 ng/mL), with <10 ng/mL as the reference group. We tested for a linear trend using the median value of each quintile as a continuous variable. In multivariable models, we included a piori the covariates that are known to be prognostic factors for CRC survival or related to 25(OH)D levels, including age, sex, race, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, RAS mutation status, prior adjuvant chemotherapy, chemotherapy backbone, assigned treatment arm, BMI, physical activity, geographic region of residence (as a surrogate for UV-B exposure), and season of blood collection.

We next examined whether the association of 25(OH)D levels with OS and PFS varied according to other prognostic factors. Interactions between 25(OH)D and potential effect modifiers were assessed by entering in the model the cross product of the 25(OH)D level as a continuous variable and the stratification variable, evaluated by the likelihood ratio test.

Data collection was conducted by the Alliance Statistics and Data Center. Data quality was ensured by review of data by the Alliance Statistics and Data Center following Alliance policies. Statistical analysis was performed based on the study database frozen on January 18, 2018, using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All P-values are two sided and were considered significant at the 0.05 level.

Results

Among 1,041 patients with advanced or metastatic CRC, the mean age was 59 years (standard deviation, 12 years), with 58% males and 42% females. The vast majority of patients were white (86%). At study entry, the median plasma 25(OH)D level in the entire study population was 17.2 ng/mL (range, 2.2 to 72.7 ng/mL) and the mean was 17.7 ng/mL (standard deviation, 7.6 ng/mL); 63% of patients were vitamin D deficient (<20 ng/mL), 31% were vitamin D insufficient (20 to <30 ng/mL), and only 6% were vitamin D sufficient (≥30 ng/mL). We also detected a 17% prevalence of extremely low 25(OH)D levels (<10 ng/mL).

Baseline characteristics by quintile of 25(OH)D are shown in Table 1. Patients with higher 25(OH)D levels had a lower BMI, were more likely to be of white race, were more likely to possess an ECOG performance status of 0, were more likely to have RAS wild-type tumors (defined as wild-type in both KRAS and NRAS), and consumed higher levels of total vitamin D and calcium.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by quintile of plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D

| Characteristic | Quintile of plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n=208) |

2 (n=209) |

3 (n=207) |

4 (n=209) |

5 (n=208) |

||

| 25-hydroxyvitamin D, ng/ml, mean (SD) | 7.7 (2.2) | 13.4 (1.3) | 17.3 (1.1) | 21.5 (1.4) | 28.8 (5.0) | <0.0001a |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 57.6 (10.6) | 59.1 (11.8) | 59.6 (12.3) | 60.3 (11.3) | 60.5 (12.8) | 0.09a |

| Sex, No. (%) | 0.003b | |||||

| Female | 108 (52) | 75 (36) | 87 (42) | 74 (35) | 93 (45) | |

| Male | 100 (48) | 134 (64) | 120 (58) | 135 (65) | 115 (55) | |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | <0.0001c | |||||

| White | 149 (72) | 177 (85) | 184 (89) | 186 (89) | 199 (96) | |

| Black | 52 (25) | 25 (12) | 12 (6) | 15 (7) | 5 (2) | |

| Other | 6 (3) | 5 (2) | 8 (4) | 6 (3) | 3 (1) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (0) | |

| ECOG performance statusd, No. (%) | 0.0004c | |||||

| 0 | 102 (49) | 133 (64) | 119 (57) | 132 (63) | 145 (70) | |

| 1 | 105 (50) | 76 (36) | 88 (43) | 77 (37) | 63 (30) | |

| 2 | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Prior adjuvant chemotherapy, No. (%) | 0.22b | |||||

| No | 186 (89) | 183 (88) | 183 (88) | 174 (83) | 174 (84) | |

| Yes | 22 (11) | 26 (12) | 24 (12) | 35 (17) | 34 (16) | |

| Chemotherapy backbone, No. (%) | 0.96b | |||||

| mFOLFOX6 | 158 (76) | 159 (76) | 162 (78) | 158 (76) | 161 (77) | |

| FOLFIRI | 50 (24) | 50 (24) | 45 (22) | 51 (24) | 47 (23) | |

| Assigned treatment arm, No. (%) | 0.38b | |||||

| Bevacizumab | 86 (41) | 74 (35) | 79 (38) | 87 (42) | 94 (45) | |

| Cetuximab | 90 (43) | 91 (44) | 84 (41) | 76 (36) | 77 (37) | |

| Bevacizumab + cetuximab | 32 (15) | 44 (21) | 44 (21) | 46 (22) | 37 (18) | |

| Disease extent | 0.89c | |||||

| Locally advanced | 3 (1) | 4 (2) | 2 (1) | 5 (2) | 2 (1) | |

| Metastatic | 205 (99) | 204 (98) | 205 (99) | 203 (97) | 205 (99) | |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (0) | 0 | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | |

| Primary tumor location, No. (%) | 0.48b | |||||

| Left (splenic flexure, descending colon, sigmoid, rectum) | 121 (58) | 123 (59) | 132 (64) | 114 (55) | 120 (58) | |

| Right (cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure) | 63 (30) | 56 (27) | 47 (23) | 71 (34) | 61 (29) | |

| Transverse | 14 (7) | 13 (6) | 15 (7) | 16 (8) | 13 (6) | |

| Multiple | 0 | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 0 | 1 (0) | |

| Unknown | 10 (5) | 15 (7) | 10 (5) | 8 (4) | 13 (6) | |

| RAS mutation status, No. (%) | 0.01b | |||||

| Wild-type | 68 (33) | 65 (31) | 55 (27) | 80 (38) | 77 (37) | |

| Mutant | 62 (30) | 62 (30) | 80 (39) | 60 (29) | 44 (21) | |

| Unknown | 78 (37) | 82 (39) | 72 (35) | 69 (33) | 87 (42) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 29.4 (7.1) | 28.6 (6.4) | 28.0 (5.7) | 28.2 (6.0) | 26.8 (5.6) | 0.0008a |

| Physical activity, MET-h/week, mean (SD) | 7.6 (16.3) | 11.9 (18.9) | 9.1 (15.2) | 11.3 (19.2) | 11.7 (18.6) | 0.15a |

| Dietary vitamin D intake, energy-adjusted, IU/d, mean (SD) | 203 (116) | 211 (119) | 214 (109) | 225 (118) | 235 (130) | 0.15a |

| Total vitamin D intakee, energy-adjusted, IU/d, mean (SD) | 261 (218) | 356 (257) | 413 (277) | 519 (332) | 556 (357) | <0.0001a |

| Total calcium intakee, energy-adjusted, mg/d, mean (SD) | 997 (503) | 1148 (550) | 1207 (534) | 1241 (533) | 1368 (637) | <0.0001a |

| Season of blood collection, No. (%) | 0.03b | |||||

| Summer (June, July, August) | 35 (17) | 43 (21) | 40 (19) | 56 (27) | 59 (28) | |

| Fall (September, October, November) | 33 (16) | 42 (20) | 40 (19) | 39 (19) | 47 (23) | |

| Winter (December, January, February) | 43 (21) | 49 (23) | 43 (21) | 50 (24) | 34 (16) | |

| Spring (March, April, May) | 97 (47) | 74 (35) | 84 (41) | 64 (31) | 68 (33) | |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Geographic region of residencef, No. (%) | 0.21c | |||||

| Southern US | 87 (42) | 77 (37) | 85 (41) | 99 (47) | 87 (42) | |

| Midwestern/western US | 81 (39) | 97 (46) | 82 (40) | 65 (31) | 85 (41) | |

| Northeastern US | 33 (16) | 33 (16) | 34 (16) | 42 (20) | 31 (15) | |

| Canada | 7 (3) | 2 (1) | 5 (2) | 2 (1) | 5 (2) | |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 | |

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; FOLFIRI, leucovorin, fluorouracil, and irinotecan; MET, metabolic equivalent; mFOLFOX6, leucovorin, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin; SD, standard deviation.

Calculated using analysis of variance test.

Calculated using Chi-squared test.

Calculated using Fisher’s exact test.

Grade 0 = fully active, able to carry on all pre-disease performance without restriction; grade 1 = restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to carry out work of a light or sedentary nature, e.g., light house work, office work; grade 2 = ambulatory and capable of all selfcare but unable to carry out any work activities, up and about more than 50% of waking hours.

Including intake from foods and supplements.

Southern US includes AL, AR, CA, CO, DE, FL, GA, HI, KY, LA, MD, MS, NV, NC, OK, SC, TN, TX, UT, VA, and WV; midwestern/western US includes ID, IL, IN, IA, KS, MI, MN, MO, MT, NE, ND, OH, OR, SD, WA, and WI; northeastern US includes AK, CT, ME, MA, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, and VT; Canada includes ON and SK.

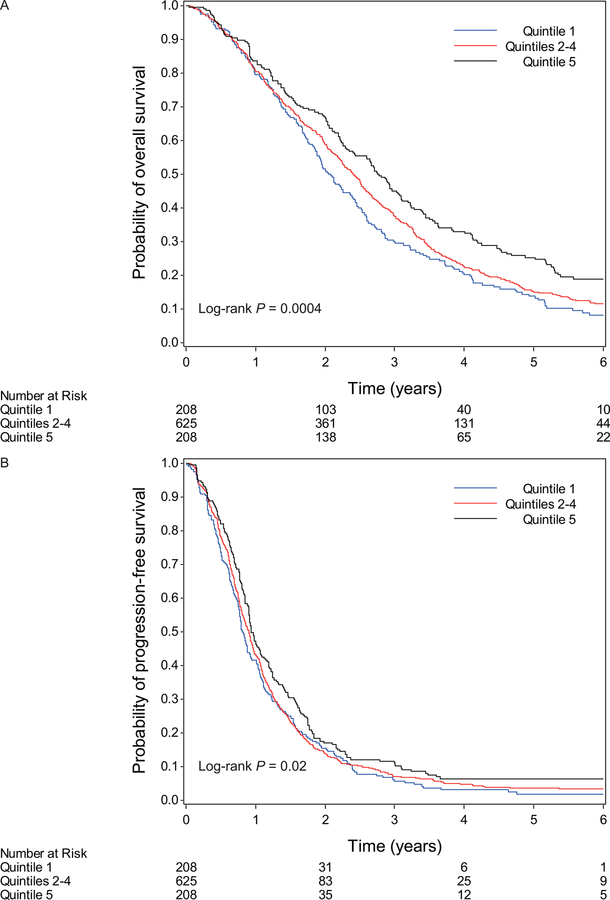

The median follow-up time among living patients was 5.6 years (90th percentile: 7.7 years). A total of 987 patients (95%) had died or progressed. Survival curves by quintile of 25(OH)D are shown in Figure 1 (log-rank P comparing extreme quintiles=0.0004 for OS and 0.02 for PFS). Higher 25(OH)D levels were associated with a significant improvement in OS (Ptrend=0.001; Table 2). These results did not change after adjustment for potential confounding factors (Ptrend=0.0009). Compared to patients in the bottom quintile of 25(OH)D (≤10.8 ng/mL), those in the top quintile (≥24.1 ng/mL) had a multivariable-adjusted HR for OS of 0.66 (95% CI, 0.53 to 0.83), corresponding to an 8-month longer median OS time. Similarly, higher plasma 25(OH)D levels were associated with a significant improvement in PFS, with patients in the top quintile having a multivariable-adjusted HR for PFS of 0.81 (95% CI, 0.66 to 1.00; Ptrend=0.03), compared to those in the bottom quintile. In sensitivity analyses, we additionally adjusted for number of metastatic sites and liver metastasis, and the association remained similar. In analyses examining survival by clinical category of 25(OH)D, a similar positive association was noted between 25(OH)D levels and patient survival (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for (A) overall survival and (B) progression-free survival according to quintile of plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Patients in quintiles 2 to 4 were combined for ease of graphic viewing.

Table 2.

Hazard ratios for overall survival and progression-free survival by quintile of plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D

| Quintile of plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D | P trenda | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Median (range), ng/ml | 8.0 (2.2–10.8) | 13.6 (10.9–15.4) | 17.2 (15.4–19.2) | 21.3 (19.3–24.0) | 27.5 (24.1–72.7) | |

| OS | ||||||

| No. of events/No. of patients | 185/208 | 184/209 | 177/207 | 177/209 | 170/208 | |

| Median OS (95% CI), months | 25 (22–29) | 30 (27–33) | 28 (24–31) | 27 (24–32) | 33 (28–37) | |

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 | 0.86 (0.70–1.05) | 0.87 (0.71–1.07) | 0.84 (0.68–1.03) | 0.70 (0.57–0.86) | 0.001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted HR (95% CI)b | 1 | 0.82 (0.66–1.02) | 0.80 (0.64–0.99) | 0.80 (0.65–1.00) | 0.66 (0.53–0.83) | 0.0009 |

| PFS | ||||||

| No. of events/No. of patients | 200/208 | 203/209 | 194/207 | 196/209 | 194/208 | |

| Median PFS (95% CI), months | 10 (9–11) | 10 (9–11) | 10 (9–12) | 11 (10–13) | 11 (11–13) | |

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 | 1.02 (0.84–1.24) | 0.91 (0.74–1.10) | 0.89 (0.73–1.08) | 0.80 (0.65–0.97) | 0.01 |

| Multivariable-adjusted HR (95% CI)b | 1 | 1.00 (0.82–1.23) | 0.89 (0.72–1.09) | 0.91 (0.73–1.12) | 0.81 (0.66–1.00) | 0.03 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

Calculated by entering quintile-specific median values for 25-hydroxyvitamin D as a continuous variable.

Adjusted for age (continuous), sex (female, male), race (white, black, other, unknown), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (0, 1, 2), prior adjuvant chemotherapy (yes, no), chemotherapy backbone (leucovorin, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin; leucovorin, fluorouracil, and irinotecan), assigned treatment arm (bevacizumab, cetuximab, bevacizumab + cetuximab), RAS mutation status (wild-type, mutant, unknown), body mass index (continuous), physical activity (continuous), season of blood collection (summer, fall, winter, spring, unknown), and geographic region of residence (southern US, midwestern/western US, northeastern US, Canada, unknown).

Table 3.

Hazard ratios for overall survival and progression-free survival by clinical category of plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D

| Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D level | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| <10 ng/mL | 10 to <20 ng/mL | ≥20 ng/mL | |

| OS | |||

| No. of events/No. of patients | 135/152 | 426/491 | 332/398 |

| Median OS (95% CI), months | 23 (20–26) | 29 (27–31) | 31 (27–34) |

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 | 0.82 (0.67–0.99) | 0.72 (0.59–0.88) |

| Multivariable-adjusted HR (95% CI)a | 1 | 0.78 (0.64–0.96) | 0.70 (0.56–0.86) |

| PFS | |||

| No. of events/No. of patients | 146/152 | 466/491 | 375/398 |

| Median PFS (95% CI), months | 9 (9–11) | 10 (9–11) | 11 (11–13) |

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | 1 | 0.88 (0.73–1.06) | 0.80 (0.66–0.96) |

| Multivariable-adjusted HR (95% CI)a | 1 | 0.87 (0.71–1.06) | 0.81 (0.66–1.00) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

Adjusted for age (continuous), sex (female, male), race (white, black, other, unknown), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (0, 1, 2), prior adjuvant chemotherapy (yes, no), chemotherapy backbone (leucovorin, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin; leucovorin, fluorouracil, and irinotecan), assigned treatment arm (bevacizumab, cetuximab, bevacizumab + cetuximab), RAS mutation status (wild-type, mutant, unknown), body mass index (continuous), physical activity (continuous), season of blood collection (summer, fall, winter, spring, unknown), and geographic region of residence (southern US, midwestern/western US, northeastern US, Canada, unknown).

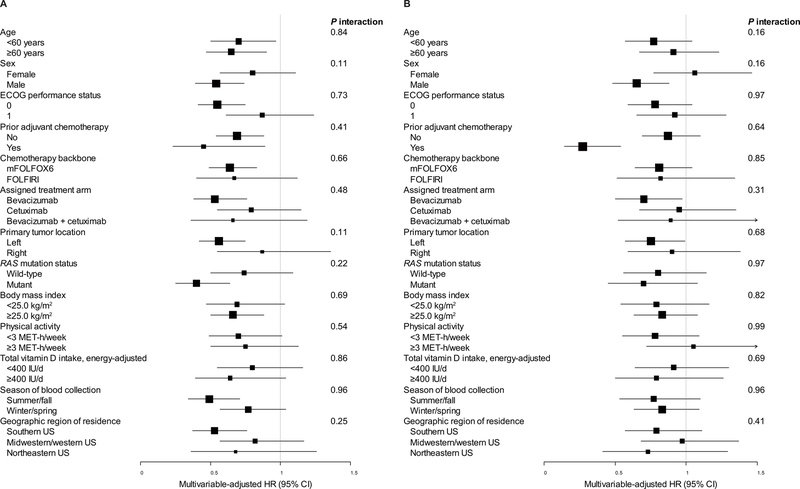

We examined the association of 25(OH)D levels with OS and PFS across strata of other prognostic factors. The association of 25(OH)D levels with OS and PFS remained largely unchanged across subgroups, including age, sex, ECOG performance status, prior adjuvant chemotherapy, chemotherapy backbone, assigned treatment arm, primary tumor location, RAS mutation status, BMI, physical activity, total vitamin D intake, geographic region of residence, and season of blood collection (all Pinteraction≥0.11; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for (A) overall survival and (B) progression-free survival, comparing the highest to lowest quintile of plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D, across strata of potential effect modifiers. Adjusted for age (continuous), sex (female, male), race (white, black, other, unknown), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (0, 1, 2), prior adjuvant chemotherapy (yes, no), chemotherapy backbone [leucovorin, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin (mFOLFOX6); leucovorin, fluorouracil, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI)], assigned treatment arm (bevacizumab, cetuximab, bevacizumab + cetuximab), RAS mutation status (wild-type, mutant, unknown), body mass index (continuous), physical activity (continuous), season of blood collection (summer, fall, winter, spring, unknown), and geographic region of residence (southern US, midwestern/western US, northeastern US, Canada, unknown), excluding the stratification variable. MET, metabolic equivalent.

Discussion

Among 1,041 patients with advanced or metastatic CRC, we found that 63% of patients were vitamin D deficient and 31% were vitamin D insufficient at baseline. Higher plasma 25(OH)D levels were associated with a significant improvement in OS and PFS. The benefit associated with higher 25(OH)D levels was consistent across most strata of demographic, lifestyle, and pathological characteristics. To our knowledge, this was the largest study of the association between circulating 25(OH)D levels and survival among patients with advanced or metastatic CRC when it was presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in 2015 (22).

The high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among patients with advanced or metastatic CRC is consistent with – and indeed more pronounced than – the trend in vitamin D status in the general US population. In the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 2001 and 2004, the mean serum 25(OH)D level was 24 ng/mL among 13,369 participants, indicating a remarkable decrease from the third NHANES (1988–1994), when the mean 25(OH)D level was 30 ng/mL (1). The major causes of this progressive decrease in vitamin D status include avoidance of sun exposure for skin cancer prevention in conjunction with increased use of sunscreen, decreased levels of physical activity, increased percentage of workforce being indoors, and the rising obesity epidemic in the US population. Compared to the general population, our participants with advanced or metastatic CRC had particularly low levels of 25(OH)D with a mean of 17.7 ng/mL, which was consistent with previous studies (6,7). We noted that patients with RAS mutant tumors had lower 25(OH)D levels than those with RAS wild-type tumors. Preclinical studies suggest that KRAS mutation could modulate vitamin D activity through the down-regulation of vitamin D receptor (VDR) (23) or resistance to growth inhibition by calcitriol [1,25(OH)2D] (24,25), the hormonally active form of vitamin D. Although we found no interaction between 25(OH)D levels and RAS mutation on patient survival, further research is warranted to investigate the underlying mechanisms.

The observed association between 25(OH)D levels and survival among patients with advanced or metastatic CRC is consistent with prior findings. We previously reported that higher prediagnostic plasma 25(OH)D levels were associated with improved OS in 304 patients with all stages of CRC from two prospective cohort studies (10). In another study of 515 metastatic CRC patients nested within the North Central Cancer Treatment Group trial N9741, we noted no association between plasma 25(OH)D levels and OS in the entire population but a benefit of higher 25(OH)D levels on OS among patients receiving FOLFOX (6). Recently, a meta-analysis of 11 studies, including the abovementioned two, with a total of 7,718 CRC patients found a robust association of higher circulating 25(OH)D levels with improved overall and CRC-specific survival (26). In addition, the promising results of the current study led to a randomized double-blind phase II trial, SUNSHINE, of 139 patients with KRAS wild-type advanced or metastatic CRC, to test whether vitamin D supplementation to raise plasma 25(OH)D levels can improve outcomes in these patients. This trial was recently published, showing that patients randomized to high-dose vitamin D supplementation (4000 IU/d) had sufficiently increased 25(OH)D levels and improved PFS compared to those receiving lose-dose vitamin D supplementation (400 IU/d) (7).

Abundant preclinical evidence supports the hypothesis that vitamin D may possess antineoplastic activity against CRC. VDR and 1-α-hydroxylase, which converts 25(OH)D into 1,25(OH)2D, are present in colon cancer cells (27–29). The binding of VDR by 1,25(OH)2D promotes differentiation (30,31), activates apoptotic pathways (32), and inhibits angiogenesis (33,34), proliferation (35), and metastasis (36) of colon cancer. In the genetically engineered mouse model of intestinal carcinogenesis (APCmin), tumor burden was significantly increased by inactivation of the VDR gene (37) and decreased by treatment with vitamin D or its synthetic analogue (38). Other mechanisms through which vitamin D may influence colorectal carcinogenesis include modulation of cellular immunity and systematic inflammation (39,40).

The current study has several strengths. The patient population was large and drawn from a rigorously conducted, multicenter NCTN phase III randomized clinical trial. All patients had pathologically proven advanced or metastatic CRC at study entry, with standardized treatment and follow-up care, as well as regular examinations to prospectively record the date and nature of cancer progression. Extensive and detailed information on lifestyle and disease characteristics was prospectively collected, so we were able to accurately adjust for potential confounders and assess their interactions with 25(OH)D levels on survival.

Nonetheless, several potential limitations warrant discussion. Because 25(OH)D levels were only measured once at study entry, the impact of changes in these levels on survival could not be studied. It is possible that lower baseline 25(OH)D levels are a surrogate for greater burden of cancer, inadequate nutrition, or limited physical activity from illness, all of which are associated with worse survival. We adjusted for these factors in multivariable analyses and continued to see a significant independent effect of higher vitamin D status on improved survival, and more importantly, our SUNSHINE randomized phase II trial (7) supports causality in the relationship between vitamin D and CRC survival. Finally, patients who enroll on clinical trials may not be representative of the population at large. Although CALGB/SWOG 80405 (Alliance) was conducted within the NCTN, which is composed of both academic and community hospitals throughout North America, our participants were predominantly individuals of European descent, and additional studies in other populations are warranted.

In conclusion, we observed a particularly high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among patients with advanced or metastatic CRC. In light of our findings that higher 25(OH)D levels are associated with improved OS and PFS, randomized trials are warranted to assess the benefit of vitamin D supplementation in CRC patients. These findings, followed by the promising results of our SUNSHINE randomized phase II trial (7), have now paved the way for an Alliance-led randomized phase III trial of vitamin D supplementation in combination with standard chemotherapy plus biologic therapy among previously untreated metastatic CRC patients (SOLARIS, Protocol A021703) to confirm causality. Correlative research using biospecimens from these clinical trial cohorts are also warranted to further elucidate underlying mechanisms of action.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance:

Preclinical and epidemiologic evidence indicates that vitamin D has a beneficial effect on colorectal cancer (CRC) survival. Among 1,041 patients with advanced or metastatic CRC participating in a randomized clinical trial, we observed a particularly high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency at baseline. Higher plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels were associated with a significant improvement in overall and progression-free survival, indicating that vitamin D supplementation to raise 25(OH)D levels may play a role in treatment of advanced and metastatic CRC. Clinical trials assessing the benefit of vitamin D supplementation in CRC patients are warranted.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers U10CA180821 and U10CA180882 (to the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology), U10CA180795, U10CA180838, U10CA180867, U24CA196171, UG1CA189858, K07CA148894 [K.N.], P50CA127003 [C.S.F., J.A.M., K.N.], R01CA118553 [C.S.F., J.A.M., K.N.], R01CA205406 [K.N.], U10CA180826 [C.S.F.], U10CA180830 [H-J.L.], and U10CA180888 [C.D.B.]. Also supported in part by funds from Project P Fund, Genentech, Sanofi, and Pfizer. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest:

R.M.G. declares consulting for Merck KGaA. C.S.F. declares consulting for Agios, Bain Capital, Bayer, Celgene, Dicerna Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly and Company, Entrinsic Health Solutions, Five Prime Therapeutics, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, KEW, Merck & Co., Merrimack Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Sanofi, Taiho Pharmaceutical, and Unum Therapeutics. He also serves as a Director for CytomX Therapeutics and owns unexercised stock options for CytomX Therapeutics and Entrinsic Health Solutions. Other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier:

References

- 1.Ginde AA, Liu MC, Camargo CA Jr. Demographic differences and trends of vitamin D insufficiency in the US population, 1988–2004. Archives of internal medicine 2009;169(6):626–32 doi 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holick MF, Chen TC. Vitamin D deficiency: a worldwide problem with health consequences. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2008;87(4):1080S–6S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2018. doi 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Neyman N, Altekruse S, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2010.[Based on the November 2012 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2013.] Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2013;9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dou R, Ng K, Giovannucci EL, Manson JE, Qian ZR, Ogino S. Vitamin D and colorectal cancer: molecular, epidemiological and clinical evidence. The British journal of nutrition 2016;115(9):1643–60 doi 10.1017/S0007114516000696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng K, Sargent DJ, Goldberg RM, Meyerhardt JA, Green EM, Pitot HC, et al. Vitamin D status in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer: findings from Intergroup trial N9741. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2011;29(12):1599–606 doi 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.7255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ng K, Nimeiri HS, McCleary NJ, Abrams TA, Yurgelun MB, Cleary JM, et al. Effect of High-Dose vs Standard-Dose Vitamin D3 Supplementation on Progression-Free Survival Among Patients With Advanced or Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: The SUNSHINE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019;321(14):1370–9 doi 10.1001/jama.2019.2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zgaga L, Theodoratou E, Farrington SM, Din FV, Ooi LY, Glodzik D, et al. Plasma vitamin D concentration influences survival outcome after a diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2014;32(23):2430–9 doi 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.5947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinicrope FA, Shi Q, Smyrk TC, Goldberg RM, Heying EN, Cohen SJ, et al. Analysis of serum vitamin D levels and prognosis in stage III colon carcinoma patients treated with adjuvant FOLFOX+/−cetuximab chemotherapy: NCCTG N0147 (Alliance). American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2017.

- 10.Ng K, Meyerhardt JA, Wu K, Feskanich D, Hollis BW, Giovannucci EL, et al. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin d levels and survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2008;26(18):2984–91 doi 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ng K, Wolpin BM, Meyerhardt JA, Wu K, Chan AT, Hollis BW, et al. Prospective study of predictors of vitamin D status and survival in patients with colorectal cancer. British journal of cancer 2009;101(6):916–23 doi 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fedirko V, Riboli E, Tjonneland A, Ferrari P, Olsen A, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, et al. Prediagnostic 25-hydroxyvitamin D, VDR and CASR polymorphisms, and survival in patients with colorectal cancer in western European ppulations. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 2012;21(4):582–93 doi 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mezawa H, Sugiura T, Watanabe M, Norizoe C, Takahashi D, Shimojima A, et al. Serum vitamin D levels and survival of patients with colorectal cancer: post-hoc analysis of a prospective cohort study. BMC cancer 2010;10:347 doi 10.1186/1471-2407-10-347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Venook AP, Niedzwiecki D, Lenz HJ, Innocenti F, Fruth B, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Effect of First-Line Chemotherapy Combined With Cetuximab or Bevacizumab on Overall Survival in Patients With KRAS Wild-Type Advanced or Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017;317(23):2392–401 doi 10.1001/jama.2017.7105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lievre A, Bachet JB, Boige V, Cayre A, Le Corre D, Buc E, et al. KRAS mutations as an independent prognostic factor in patients with advanced colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2008;26(3):374–9 doi 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.5906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tol J, Koopman M, Cats A, Rodenburg CJ, Creemers GJ, Schrama JG, et al. Chemotherapy, bevacizumab, and cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2009;360(6):563–72 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa0808268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hecht JR, Mitchell E, Chidiac T, Scroggin C, Hagenstad C, Spigel D, et al. A randomized phase IIIB trial of chemotherapy, bevacizumab, and panitumumab compared with chemotherapy and bevacizumab alone for metastatic colorectal cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2009;27(5):672–80 doi 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollis BW. Quantitation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D by radioimmunoassay using radioiodinated tracers. Methods in enzymology 1997;282:174–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. Journal of the American statistical association 1958;53(282):457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mantel N Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer chemotherapy reports 1966;50(3):163–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. Breakthroughs in statistics: Springer; 1992. p 527–41. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng K, Venook AP, Sato K, Yuan C, Hollis BW, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Vitamin D status and survival of metastatic colorectal cancer patients: Results from CALGB/SWOG 80405 (Alliance). American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2015.

- 23.Qi X, Tang J, Pramanik R, Schultz RM, Shirasawa S, Sasazuki T, et al. p38 MAPK activation selectively induces cell death in K-ras-mutated human colon cancer cells through regulation of vitamin D receptor. J Biol Chem 2004;279(21):22138–44 doi 10.1074/jbc.M313964200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solomon C, Sebag M, White JH, Rhim J, Kremer R. Disruption of vitamin D receptor-retinoid X receptor heterodimer formation following ras transformation of human keratinocytes. J Biol Chem 1998;273(28):17573–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solomon C, Kremer R, White JH, Rhim JS. Vitamin D resistance in RAS-transformed keratinocytes: mechanism and reversal strategies. Radiat Res 2001;155(1 Pt 2):156–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maalmi H, Walter V, Jansen L, Boakye D, Schottker B, Hoffmeister M, et al. Association between Blood 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels and Survival in Colorectal Cancer Patients: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2018;10(7) doi 10.3390/nu10070896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meggouh F, Lointier P, Saez S. Sex steroid and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptors in human colorectal adenocarcinoma and normal mucosa. Cancer research 1991;51(4):1227–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vandewalle B, Adenis A, Hornez L, Revillion F, Lefebvre J. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptors in normal and malignant human colorectal tissues. Cancer letters 1994;86(1):67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zehnder D, Bland R, Williams MC, McNinch RW, Howie AJ, Stewart PM, et al. Extrarenal expression of 25-hydroxyvitamin d(3)-1 alpha-hydroxylase. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 2001;86(2):888–94 doi 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vandewalle B, Wattez N, Lefebvre J. Effects of vitamin D3 derivatives on growth, differentiation and apoptosis in tumoral colonic HT 29 cells: possible implication of intracellular calcium. Cancer letters 1995;97(1):99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palmer HG, Gonzalez-Sancho JM, Espada J, Berciano MT, Puig I, Baulida J, et al. Vitamin D(3) promotes the differentiation of colon carcinoma cells by the induction of E-cadherin and the inhibition of beta-catenin signaling. The Journal of cell biology 2001;154(2):369–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diaz GD, Paraskeva C, Thomas MG, Binderup L, Hague A. Apoptosis is induced by the active metabolite of vitamin D3 and its analogue EB1089 in colorectal adenoma and carcinoma cells: possible implications for prevention and therapy. Cancer research 2000;60(8):2304–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iseki K, Tatsuta M, Uehara H, Iishi H, Yano H, Sakai N, et al. Inhibition of angiogenesis as a mechanism for inhibition by 1alpha-hydroxyvitamin D3 and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 of colon carcinogenesis induced by azoxymethane in Wistar rats. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer 1999;81(5):730–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fernandez-Garcia NI, Palmer HG, Garcia M, Gonzalez-Martin A, del Rio M, Barettino D, et al. 1alpha,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 regulates the expression of Id1 and Id2 genes and the angiogenic phenotype of human colon carcinoma cells. Oncogene 2005;24(43):6533–44 doi 10.1038/sj.onc.1208801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scaglione-Sewell BA, Bissonnette M, Skarosi S, Abraham C, Brasitus TA. A vitamin D3 analog induces a G1-phase arrest in CaCo-2 cells by inhibiting cdk2 and cdk6: roles of cyclin E, p21Waf1, and p27Kip1. Endocrinology 2000;141(11):3931–9 doi 10.1210/endo.141.11.7782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evans SR, Shchepotin EI, Young H, Rochon J, Uskokovic M, Shchepotin IB. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 synthetic analogs inhibit spontaneous metastases in a 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced colon carcinogenesis model. Int J Oncol 2000;16(6):1249–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng W, Wong KE, Zhang Z, Dougherty U, Mustafi R, Kong J, et al. Inactivation of the vitamin D receptor in APC(min/+) mice reveals a critical role for the vitamin D receptor in intestinal tumor growth. International journal of cancer 2012;130(1):10–9 doi 10.1002/ijc.25992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huerta S, Irwin RW, Heber D, Go VL, Koeffler HP, Uskokovic MR, et al. 1alpha,25-(OH)(2)-D(3) and its synthetic analogue decrease tumor load in the Apc(min) Mouse. Cancer research 2002;62(3):741–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Harten-Gerritsen AS, Balvers MG, Witkamp RF, Kampman E, van Duijnhoven FJ. Vitamin D, Inflammation, and Colorectal Cancer Progression: A Review of Mechanistic Studies and Future Directions for Epidemiological Studies. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 2015;24(12):1820–8 doi 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song M, Nishihara R, Wang M, Chan AT, Qian ZR, Inamura K, et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D and colorectal cancer risk according to tumour immunity status. Gut 2016;65(2):296–304 doi 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.