The Ebola virus VP24 protein plays a critical role in escape of the virus from the host innate immune response. Therefore, deciphering the molecular mechanisms modulating VP24 activity may be useful to identify potential targets amenable to therapeutics. Here, we identify the cellular proteins USP7, SUMO, and ubiquitin as novel interactors and regulators of VP24. These interactions may represent novel potential targets to design new antivirals with the ability to modulate Ebola virus replication.

KEYWORDS: SUMO, USP7, VP24, Ebola virus, ubiquitin

ABSTRACT

Some viruses take advantage of conjugation of ubiquitin or ubiquitin-like proteins to enhance their own replication. One example is Ebola virus, which has evolved strategies to utilize these modification pathways to regulate the viral proteins VP40 and VP35 and to counteract the host defenses. Here, we show a novel mechanism by which Ebola virus exploits the ubiquitin and SUMO pathways. Our data reveal that minor matrix protein VP24 of Ebola virus is a bona fide SUMO target. Analysis of a SUMOylation-defective VP24 mutant revealed a reduced ability to block the type I interferon (IFN) pathway and to inhibit IFN-mediated STAT1 nuclear translocation, exhibiting a weaker interaction with karyopherin 5 and significantly diminished stability. Using glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown assay, we found that VP24 also interacts with SUMO in a noncovalent manner through a SIM domain. Mutation of the SIM domain in VP24 resulted in a complete inability of the protein to downmodulate the IFN pathway and in the monoubiquitination of the protein. We identified SUMO deubiquitinating enzyme ubiquitin-specific-processing protease 7 (USP7) as an interactor and a negative modulator of VP24 ubiquitination. Finally, we show that mutation of one ubiquitination site in VP24 potentiates the IFN modulatory activity of the viral protein and its ability to block IFN-mediated STAT1 nuclear translocation, pointing to the ubiquitination of VP24 as a negative modulator of the VP24 activity. Altogether, these results indicate that SUMO interacts with VP24 and promotes its USP7-mediated deubiquitination, playing a key role in the interference with the innate immune response mediated by the viral protein.

IMPORTANCE The Ebola virus VP24 protein plays a critical role in escape of the virus from the host innate immune response. Therefore, deciphering the molecular mechanisms modulating VP24 activity may be useful to identify potential targets amenable to therapeutics. Here, we identify the cellular proteins USP7, SUMO, and ubiquitin as novel interactors and regulators of VP24. These interactions may represent novel potential targets to design new antivirals with the ability to modulate Ebola virus replication.

INTRODUCTION

Ebola virus (species Zaire ebolavirus; EBOV) is a highly pathogenic agent causing hemorrhagic fever with a high case fatality rate in humans. One of the mechanisms that contribute to the pathogenesis of the virus is the inhibition of signaling cascades of the interferon (IFN) system by EBOV protein VP24. The minor matrix VP24 protein has been reported to exert its inhibitory activity by competing with tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT1 for interaction with the importins alpha karyopherin 1 (KPNA1), KPNA5, and KPNA6, inhibiting the import of phosphorylated STAT1 into the nucleus (1–3). So far, whether the IFN-signaling modulatory activity of VP24 can be regulated at the posttranslational level has not been investigated. Identification of molecular mechanisms controlling the antagonistic activity of VP24 may be useful to identify potential targets amenable to therapeutics.

Posttranslational modifications by ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins play a key role in the regulation of protein-protein interactions, being essential in the control of multiple processes (4). SUMOylation consists in the covalent attachment of the small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) to a lysine residue in the target protein by an enzymatic process that requires an E1 activating enzyme, a ubiquitin E2 conjugating enzyme (Ubc9), and a SUMO E3 ligase (5). This modification may promote or inhibit binding to other proteins. Importantly, many SUMOylated proteins also contain SUMO-interacting motifs (SIM) that mediate the noncovalent interaction between the target protein and SUMO or SUMOylated proteins (6). In addition, ubiquitin, through its numerous connections with SUMO, may alter the properties of the SUMO substrate (7). Many viruses have developed strategies to manipulate these modification pathways to favor virus replication either by modulating global or specific cellular protein modifications or by exploiting the modification machinery of the cell to regulate their own proteins (8, 9). One example is EBOV, which can exploit the SUMOylation machinery of the cell using both strategies. The EBOV VP35 protein induces SUMOylation of IRF7 and therefore inhibits the production of type I interferon (IFN) (10), and the EBOV major matrix VP40 protein is modified by SUMO, which contributes to its stability (11). Furthermore, EBOV can also exploit the ubiquitination pathway. Thus, promotion of EBOV replication by conjugation of VP35 or VP40 proteins to ubiquitin has been reported previously (12, 13).

Here, we identify a novel mechanism by which EBOV exploits both the ubiquitin and the SUMO pathways. Our data demonstrate that VP24 can interact with SUMO in both covalent and noncovalent manners. Inhibition of the covalent and noncovalent interactions between VP24 and SUMO modulated the ability of the protein to interact with karyopherin 5 (KPNA5) and to inhibit the IFN-mediated STAT1 nuclear translocation and diminished and totally blocked, respectively, the ability of the viral protein to inhibit the IFN signaling. In addition, inhibition of the noncovalent VP24-SUMO interaction promoted the monoubiquitination of the viral protein, a modification regulated through its interaction with the SUMO deubiquitinase ubiquitin-specific-processing protease 7 (USP7). Interestingly, mutation of a ubiquitination site in VP24 potentiated the IFN downmodulation activity of the viral protein. In summary, we have identified a novel mechanism by which EBOV exploits the SUMOylation machinery of the cell and demonstrate that this strategy contributes to viral control of the immune response.

RESULTS

EBOV VP24 is modified by SUMO.

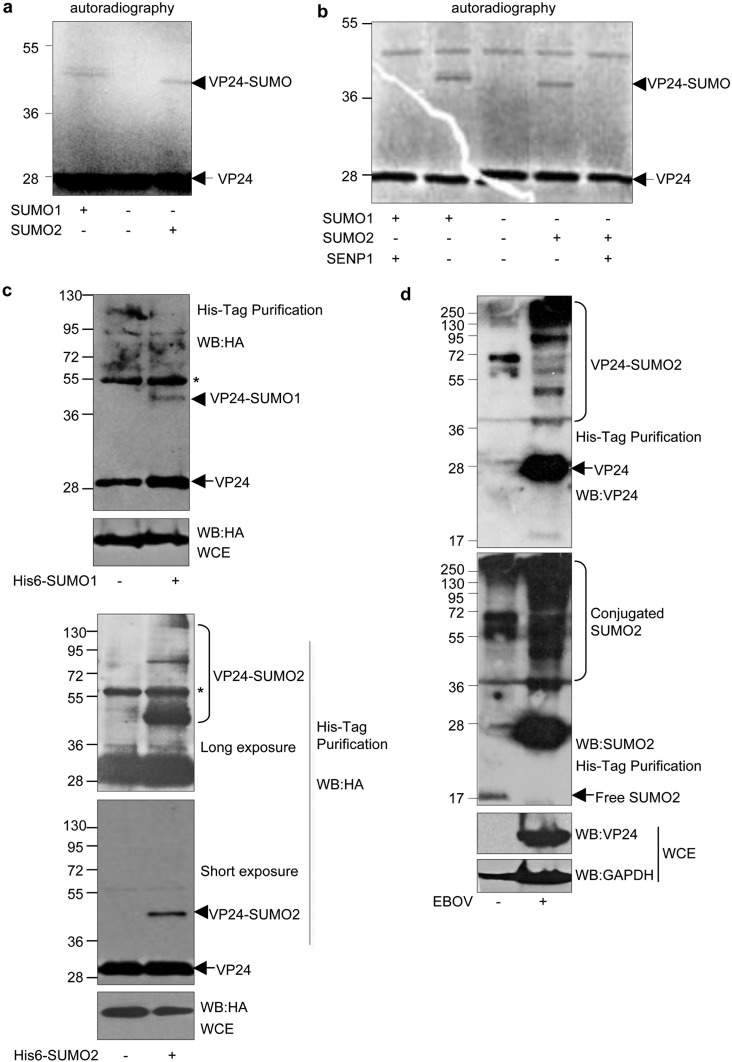

We wondered whether VP24 protein could be modified by SUMO. To evaluate whether EBOV VP24 was modified in vitro, we carried out an in vitro SUMOylation assay with 35S-methionine-labeled in vitro-translated VP24 in the presence of SUMO1 or SUMO2. The molecular weight of the in vitro-translated VP24 was around 28 kDa, as expected (14) (Fig. 1a). Incubation with SUMO1 induced the appearance of a double band of around 40 kDa (Fig. 1a), indicating that VP24 can be SUMOylated by SUMO1 in vitro and suggesting that the VP24-SUMO1 protein may be additionally modified (Fig. 1a). A band of around 40 kDa was detected also after incubation of the protein with SUMO2 (Fig. 1a), indicating that VP24 can be modified by SUMO2 in vitro. To prove that the 40-kDa band corresponds to SUMOylated VP24 protein, the VP24-SUMO1 and VP24-SUMO2 proteins were incubated with the SUMO-specific protease SENP1. The 40-kDa-molecular-weight bands disappeared after incubation with SENP1, demonstrating that EBOV VP24 protein is modified by SUMO1 and SUMO2 in vitro (Fig. 1b). To confirm that the protein can be modified also in living cells, we transfected HEK-293 cells with hemagglutinin-VP24 (HA-VP24) in combination either with pcDNA-, Ubc9-, and His6-SUMO1-expressing plasmids or with Ubc9- and His6-SUMO2-expressing plasmids and, at 36 h after transfection, whole-protein extracts and histidine-tagged proteins purified under denaturing conditions using nickel columns were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody. As shown in Fig. 1c, analysis of the purified proteins revealed a 40-kDa band exclusively in those cells transfected with His6-SUMO1 (upper panel) or His6-SUMO2 (lower panel). Also, additional higher-molecular-weight bands corresponding to VP24 protein conjugated to SUMO2 chains were observed in the His6-SUMO2-transfected cells (Fig. 1c, lower panel). These results indicated that VP24 protein is modified by SUMO1 and SUMO2 in transfected cells. Finally, we decided to evaluate whether VP24 protein is SUMOylated in cells infected with authentic EBOV. HeLa cells stably expressing His6-SUMO2 were infected with EBOV, and at 5 days after infection, the histidine-tagged proteins were purified under denaturing conditions. Western blot analysis of the purified proteins by the use of anti-VP24 antibody revealed the appearance of multiple bands corresponding to VP24-SUMO2 protein, indicating that VP24 is modified in infected cells (Fig. 1d). Interestingly, subsequent incubation with anti-SUMO2 antibody also revealed that EBOV infection triggers an increase in the levels of SUMOylated proteins whereas the level of unconjugated SUMO2 protein decreases (Fig. 1d). Altogether, these results indicate that the VP24 protein was modified by SUMO1 and SUMO2 in vitro and in vivo.

FIG 1.

EBOV VP24 protein is modified by SUMO. (a) In vitro SUMOylation assay in the presence of SUMO1 or SUMO2 using 35S-methionine-labeled in vitro-translated VP24 protein. (b) SUMO1-VP24 or SUMO2-modified VP24 proteins were incubated with SENP1. (c) HEK-293 cells were transfected with HA-VP24 in combination with either pcDNA, Ubc9 and His6-SUMO1-expressing plasmids (upper panel) or His6-SUMO2-expressing plasmids (lower panel), and 36 h after transfection, whole-protein extracts and histidine-tagged purified proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody. The asterisk indicates an unspecific band. (d) HeLa cells stably expressing His6-SUMO2 were infected with Ebola virus or left uninfected. At 5 days after infection, whole-protein extracts or histidine-tagged purified proteins were then analyzed by Western blotting (WB) with the indicated antibodies. WCE, whole-cell extracts.

Mutation of the SUMOylation site in VP24 slightly reduces its stability and its ability to both block IFN-I signaling and interact with KPNA5.

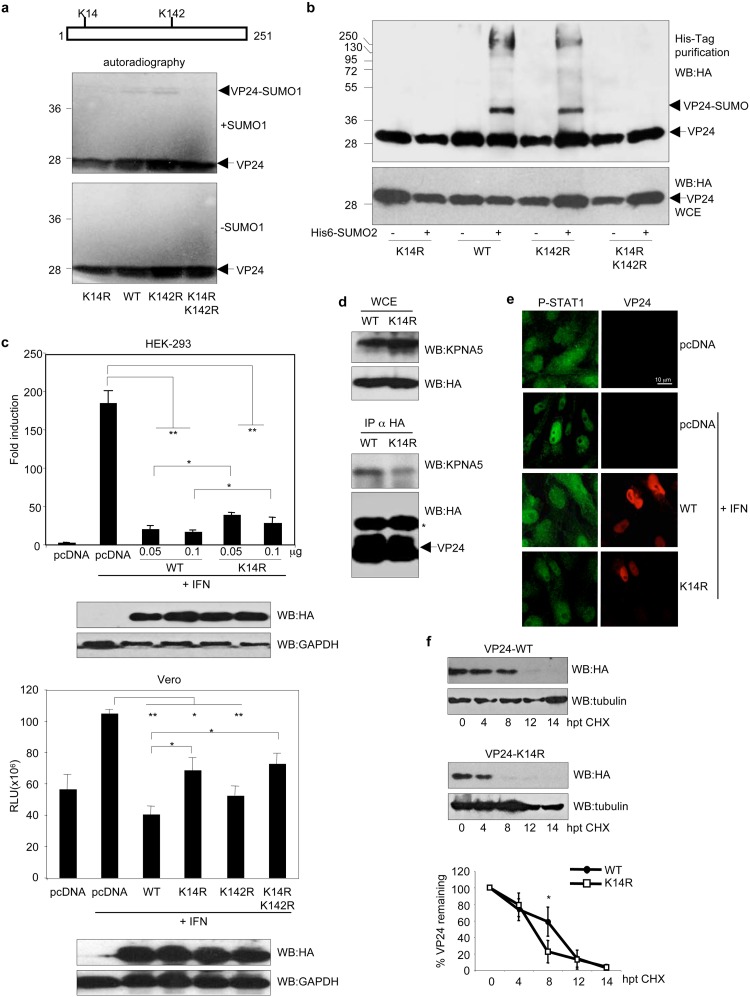

In silico analysis of the VP24 amino acid sequence using the SUMOsp2.0 program revealed lysine residue K142 to be the most probable residue involved in SUMO conjugation and K14 as the second most probable SUMO conjugation site in VP24. We then generated single mutants in lysine K14 (VP24-K14R) or K142 (VP24-K142R) or the double mutant VP24-K14RK142R, and then we carried out an in vitro SUMOylation assay with 35S-methionine-labeled in vitro-translated VP24 wild-type (VP24-WT), VP24-K14R, VP24-K142R, or VP24-K14RK142R proteins in the presence of SUMO1. We did not observe a reduction in the level of in vitro SUMOylation of the VP24-K142R mutant in comparison with the WT protein (Fig. 2a). However, we observed a reduction in the SUMOylation of the K14R or K14RK142R VP24 mutants, indicating that lysine residue K14 is involved in SUMO conjugation. To confirm this result, we then evaluated the relevance of these residues for the SUMOylation of VP24 in vivo. We cotransfected HEK-293 cells with HA-VP24-WT or the indicated mutants together with pcDNA or Ubc9 and His6-SUMO2, and 36 h after transfection, whole-protein extracts and histidine-tagged proteins purified under denaturing conditions using nickel columns were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody. We observed a clear reduction in the SUMOylation of both the VP24-K14R and VP24-K14RK142R mutants relative to the WT protein (Fig. 2b), indicating that lysine residue K14 in VP24 is indeed involved in SUMO conjugation.

FIG 2.

Mutation of the SUMOylation site in VP24 slightly reduces its stability and its ability to block interferon. (a) In vitro SUMOylation assay performed with SUMO1 using 35S-methionine-labeled in vitro-translated VP24-WT, VP24-K14R, VP24-K142R or VP24-K14RK142R proteins. (b) HEK-293 cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding HA-tagged VP24-WT, VP24-K14R, VP24-K142R, or VP24-K14RK142R together with pcDNA or with Ubc9 and His6-SUMO2, and 36 h after transfection, whole-protein extracts and histidine-tagged purified proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody. (c) HEK-293 cells (upper panel) were cotransfected with the luciferase reporter ISG54-luc and the pcDNA-beta-galactosidase plasmids together with the indicated doses of HA-VP24-WT or HA-VP24-K14R. Cells were treated with IFN-α 24 h after transfection, and luciferase production was analyzed 16 h after treatment. Columns are representative of means of results, and error bars represent standard deviations of results from three biological replicates. Similar results were obtained at least twice. Statistical significance was assessed by a Student's t test. Cell lysates from the experiment were analyzed by Western blotting for HA-VP24 expression (bottom panel). Vero cells (lower panel) were cotransfected with the luciferase reporter ISG54-luc and the pcDNA-beta-galactosidase plasmids together with the indicated plasmids. Cells were treated with IFN-α 24 h after transfection, and luciferase production was analyzed 16 h after treatment. Columns are representative of means of results, and error bars represent standard deviations of results from three biological replicates. Statistical significance was assessed by a Student's t test. Cell lysates from the experiment were analyzed by Western blotting for HA-VP24 expression (lower panel). (d) HEK-293 cells were transfected with HA-VP24 WT or HA-VP24-K14R, and 36 h after transfection, immunoprecipitations (IP) were performed with anti-HA antibody, and the precipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA or anti-KPNA5 antibodies, as indicated. The asterisk indicates the immunoglobulin. (e) Vero cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids, and 24 h after transfection, cells were serum starved for 4 h and then treated with 1,000 U/ml of human IFN-alpha for 30 min or left untreated. Cells were then fixed and immunostained using primary goat anti-HA and mouse anti-phosphorylated STAT1 (P-STAT1) antibodies and secondary Alexa 488 chicken anti-mouse and Alexa 594 donkey anti-goat antibodies. (f) HEK-293 cells were transfected with HA-VP24-WT or HA-VP24-K14R, and 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with cycloheximide (CHX). At the indicated hours after CHX treatment, protein extracts were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody. VP24 protein intensity bands were quantified using ImageJ software. VP24 band intensity was normalized to tubulin from each respective time point and plotted. Data represent means and error bars of results from 3 independent experiments and 2 biological replicas. Statistical analysis was assessed by a Student's t test.

One of the main functions of VP24 is to inhibit IFN-I signaling (2). Therefore, we decided to evaluate whether mutation of the SUMOylation site in VP24 would alter the ability of the viral protein to inhibit IFN-I signaling. We cotransfected HEK-293 cells with ISG54-luc together with beta-galactosidase and pcDNA, HA-VP24-WT, or HA-VP24-K14R, as indicated, and 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with IFN-α for 16 h. Cell extracts were then harvested and assayed for luciferase and beta-galactosidase activity. We observed that IFN induced transactivation of the reporter, as expected, and that VP24-WT significantly abolished this transactivation, as previously reported (Fig. 2c, upper panel) (2). The luciferase levels observed in cells transfected with the VP24-K14R mutant were significantly lower than the levels detected in pcDNA-transfected cells but significantly higher than the levels observed in the VP24-WT-transfected cells (Fig. 2c, upper panel), suggesting that conjugation of SUMO to lysine K14 in VP24 contributes to the inhibition of IFN signaling by the viral protein. Evaluation of the ability of the protein to inhibit IFN-I signaling was also carried out in Vero cells. We cotransfected Vero cells with ISG54-luc together with beta-galactosidase and pcDNA, HA-VP24-WT, HA-VP24-K14R, HA-VP24-K142R, or HA-VP24-K14RK142R, and 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with IFN-α for 16 h. Cells were then harvested, and extracts were assessed for luciferase and beta-galactosidase activity. We observed that IFN induced transactivation of the reporter and that VP24-WT significantly abolished this transactivation, as expected (Fig. 2c, lower panel). We did not detect significant differences in the abilities of VP24-K142R and VP24-WT to inhibit the transactivation of the reporter (Fig. 2c, lower panel). We also observed that VP24-K14R inhibited ISG54 reporter activity but that this reduction was significantly lower than that caused by the WT protein (Fig. 2c, lower panel). In addition, we observed that VP24-K14RK142R was unable to block the IFN pathway (Fig. 2c, lower panel). These results suggest that conjugation of SUMO to lysine K14 in VP24 contributes to the inhibition of IFN signaling by the viral protein.

Inhibition of the IFN activity by VP24 has been reported to be mediated, at least partially, by its binding to karyopherin alpha 1, 5, and 6 (2, 3, 15). Therefore, we decided to evaluate the binding between VP24-K14R and karyopherin. HEK-293 cells were transfected with HA-VP24-WT or HA-VP24-K14R expression plasmids. At 36 h after transfection, immunoprecipitations (IP) were performed with anti-HA antibody, and the precipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA or anti-KPNA5 antibodies. As shown in Fig. 2d, the levels of KPNA5 coimmunoprecipitating with HA-VP24-K14R were lower than the levels of KPNA5 protein interacting with VP24-WT, indicating that lysine residue K14R contributes to the VP24-KPNA5 interaction.

Interaction of VP24 with karyopherin blocks the nuclear accumulation of phosphorylated STAT1 in response to interferon treatment (2). We therefore carried out immunofluorescence analysis of phosphorylated STAT1 in Vero cells expressing VP24-WT or VP24-K14R protein after treatment with IFN. Treatment with IFN of cells transfected with an empty vector (pcDNA) induced the translocation of STAT1 to the nucleus in 88% of the cells (n = 69), whereas only 4% of the cells expressing VP24-WT (n = 72) exhibited nuclear STAT1 protein (Fig. 2e). This percentage increased to 36% in cells expressing VP24-K14R (n = 79) (Fig. 2e). These observations suggest that the covalent interaction of VP24 with SUMO has a positive impact on the ability of VP24 to block STAT1 nuclear accumulation in response to IFN treatment.

Interaction of EBOV VP24 protein with karyopherin has also been reported to increase the stability of the viral protein (16). We thus decided to evaluate the stability of the VP24-K14R mutant. HEK-293 cells transfected with WT or K14R mutant VP24 proteins were treated with cycloheximide, and at different times after treatment, HA-VP24 protein was analyzed by Western blotting using anti-HA antibody, and levels were quantified and plotted. As shown in Fig. 2f, the stability of VP24-K14R was significantly reduced compared with the stability of the VP24-WT protein, suggesting that conjugation of SUMO to lysine residue K14 in VP24 contributes to its stability.

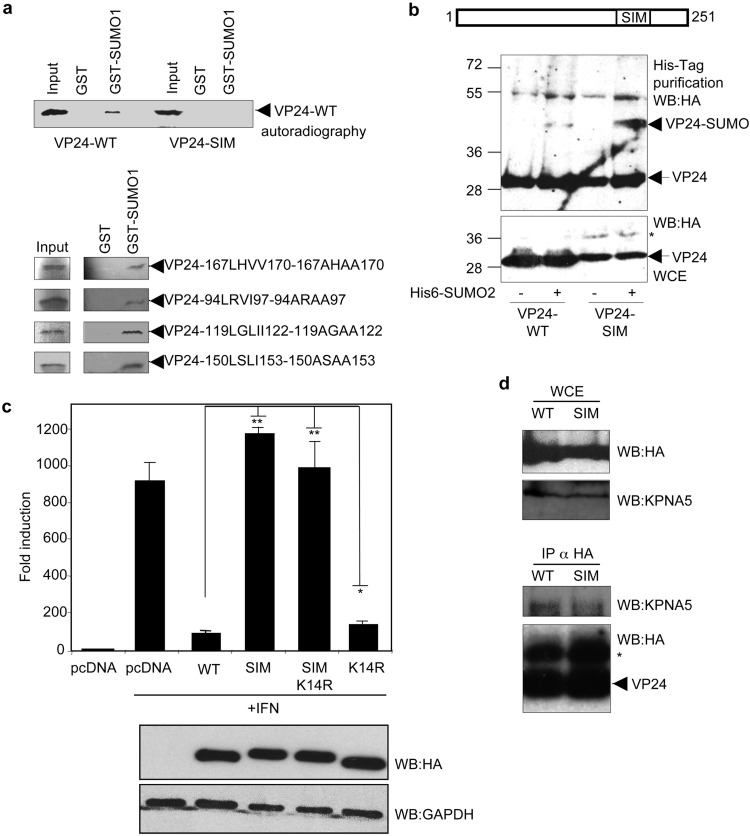

The SIM domain in VP24 mediates its noncovalent interaction with SUMO and is essential for the control of IFN activity by the viral protein.

Many SUMOylated proteins can interact with SUMO in a noncovalent manner through a SUMO-interacting motif (SIM), which has been reported to consist of a hydrophobic core with the consensus sequence V/I/L-X-V/I/L-V/I/L or V/I/L-V/I/L-X-V/I/L (17). In silico analysis of EBOV VP24 using the SUMOsp2.0 program revealed the presence of 5 putative SIM domains in VP24. We then generated single mutants of VP24 in the different putative SIM domains and carried out a glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown assay using 35S-methionine-labeled in vitro-translated VP24 proteins and GST-SUMO1. As shown in Fig. 3a, we observed that VP24-WT interacted with SUMO1 in a noncovalent manner. Similarly, we observed interactions of VP24-94LRVI97-94ARAA97, VP24-119LGLI122-119AGAA122, VP24-150LSLI153-150ASAA153, and VP24-167LHVV170-167AHAA170 mutants with GST-SUMO1 (Fig. 3a). However, we detected a clear reduction in the level of the interaction between VP24-198LVEL201-198AAEA201 (VP24-SIM) and GST-SUMO1 (Fig. 3a), indicating that the 198LVEL201 SIM domain is involved in noncovalent conjugation of VP24 with SUMO1.

FIG 3.

VP24 protein interacts with SUMO in a noncovalent manner, and this interaction is required for the control of IFN activity by the viral protein. (a) GST pulldown assay using 35S-methionine-labeled in vitro-translated VP24-WT or the indicated VP24 mutants and GST or GST-SUMO1. (b) HEK-293 cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding HA-VP24-WT or HA-VP24-SIM together with pcDNA or Ubc9 and His6-SUMO2, and 36 h after transfection, whole-protein extracts and histidine-tagged purified proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody. The asterisk indicates a band of around 10-kDa-higher molecular weight than VP24 detected in the cells transfected with VP24-SIM. (c) HEK293 cells were cotransfected with the luciferase reporter ISG54-luc together with pcDNA, HA-VP24-WT, or the indicated mutants. Cells were treated with IFN-α 24 h after transfection, and luciferase production was analyzed 16 h after treatment. Columns are representative of means of results, and error bars represent standard deviations of results from three biological replicates. Similar results were obtained at least twice. Statistical significance was assessed by a Student's t test. Cell lysates from the experiment were analyzed by Western blotting for HA-VP24 expression (lower panel). (d) HEK-293 cells were transfected with HA-VP24 WT or HA-VP24-SIM, and 36 h after transfection, immunoprecipitations (IP) were performed with anti-HA antibody, and the precipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA or anti-KPNA5 antibodies, as indicated. The asterisk indicates the immunoglobulin.

The presence of a SIM motif in the SUMOylation substrate can contribute to its conjugation to SUMO. We then decided to evaluate whether mutation of the SIM domain in VP24 inhibited its SUMO conjugation. HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with HA-VP24-WT or HA-VP24-SIM and with pcDNA or Ubc9 and His6-SUMO2, and 48 h after transfection, whole-protein extracts and histidine-tagged purified proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody. As shown in Fig. 3b, we observed SUMOylation of the VP24-SIM protein, suggesting that conjugation of SUMO to VP24 did not require the SIM domain.

We then decided to evaluate whether the mutation of the SIM domain in VP24 had a role in the modulation of the IFN-signaling pathway by the viral protein. We cotransfected HEK-293 cells with ISG54-luc together with beta-galactosidase and pcDNA, HA-VP24-WT, HA-VP24-K14R, HA-VP24-SIM or the double mutant HA-VP24-SIMK14R, as indicated, and 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with IFN-α for 16 h. Cell extracts were then harvested and assayed for luciferase and beta-galactosidase activity. IFN treatment induced transactivation of the reporter, and statistically significant results showed that VP24-WT abolished this transactivation, as expected (Fig. 3c). The ability of a mutant of VP24 with a mutation in lysine residue K14 to block the IFN response was significantly reduced relative to the WT protein, as shown above (Fig. 3c). Interestingly, both VP24-SIM and VP24-SIMK14R proteins were totally unable to block the IFN pathway (Fig. 3c), indicating that the SIM motif in VP24 was essential for its IFN downmodulation activity.

We then evaluated the coimmunoprecipitation between VP24-SIM and KPNA5. As shown in Fig. 3d, the levels of KPNA5 that coimmunoprecipitated with HA-VP24-SIM were lower than the levels of KPNA5 protein interacting with VP24-WT protein, indicating that the SIM domain in VP24 contributes to the interaction with KPNA5.

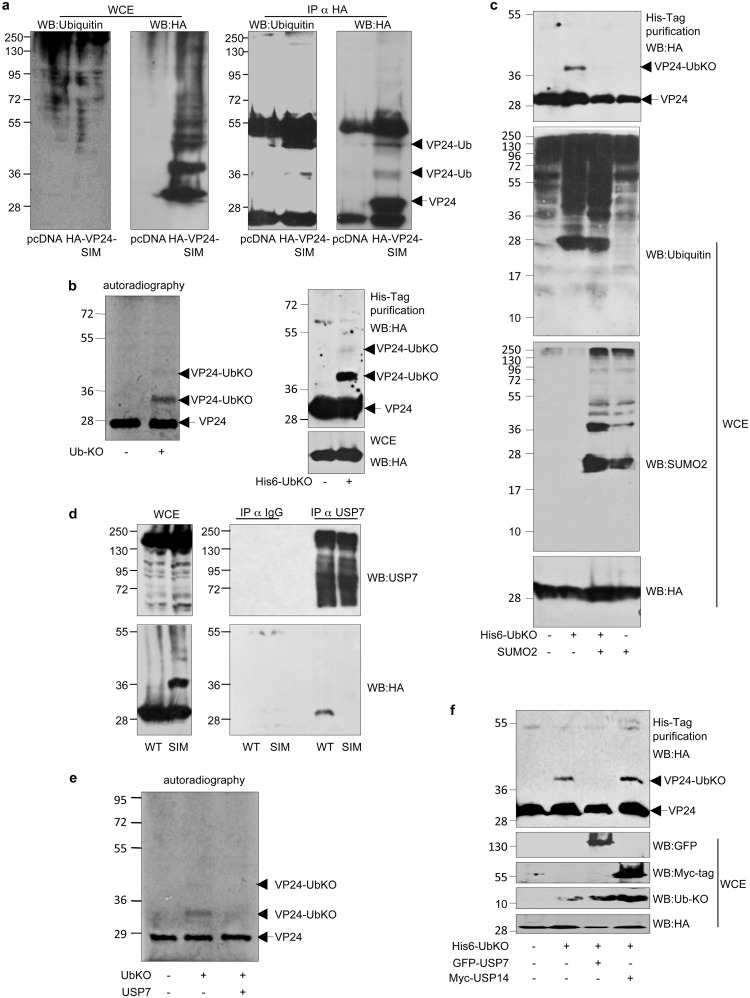

Mutation of the SIM domain in VP24 inhibits its interaction with ubiquitin-specific-processing protease 7 (USP7) and promotes its monoubiquitination.

Of note, Western blotting of the cells transfected with HA-VP24-SIM revealed the appearance of a band of the expected VP24-WT molecular weight, as well as an additional band of around 38 kDa (Fig. 3b; band marked by an asterisk). We wondered whether this 10-kDa-higher-molecular-weight band might correspond to monoubiquitin-modified VP24 protein. To evaluate the putative monoubiquitination of VP24-SIM, we first transfected HEK-293 cells with pcDNA or HA-VP24-SIM, and 24 h after transfection, VP24-SIM protein was immunoprecipitated using anti-HA antibody and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-ubiquitin antibody. As shown in Fig. 4a, the anti-ubiquitin antibody recognized a band of the expected 38-kDa molecular weight in the lane corresponding to the HA-VP24-SIM protein, identified also with the anti-HA antibody, indicating that mutation of the SIM domain in VP24 promoted its monoubiquitination. Therefore, we then decided to study the putative monoubiquitination of the WT protein. We first carried out an in vitro ubiquitination assay using 35S-methionine-labeled in vitro-translated VP24-WT protein in the presence of recombinant ubiquitin protein in which all the lysine residues had been mutated to arginine (ubiquitin knockout [UbKO]). As shown in Fig. 4b (left panel), incubation of VP24 protein with UbKO led to the appearance of two additional bands of around 38 and 48 kDa, indicating that monoubiquitin could be conjugated to at least two lysine residues in VP24 in vitro. To determine whether VP24 protein could be monoubiquitinated also in cells, we transfected HEK-293 cells with HA-VP24-WT together with pcDNA or His6-UbKO. Analysis of the histidine-tagged purified proteins using anti-HA antibody revealed the appearance of two bands of around 38 and 48 kDa in the lane corresponding to His-UbKO-transfected cells (Fig. 4b, right panel), indicating that VP24 could be monoubiquitinated in cells. The results shown here suggested that inhibition of the SIM-mediated noncovalent interaction between VP24 and SUMO or SUMOylated proteins promoted the covalent interaction between VP24 and ubiquitin. Therefore, we decided to evaluate whether an increase in SUMO levels would negatively modulate the ubiquitination of VP24. HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with HA-VP24-WT together with pcDNA, His6-UbKO, and pcDNA, with SUMO2 and pcDNA, or with SUMO2 and His6-UbKO, and 48 h after transfection, whole-protein extracts and histidine-tagged purified proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody. Western blotting of the purified proteins revealed the appearance of bands corresponding to monoubiquitinated VP24 protein in cells transfected with His6-UbKO and pcDNA that were almost undetectable in cells cotransfected with His6-UbKO and SUMO2 (Fig. 4c). These findings suggested that SUMO2 had a negative impact on the monoubiquitination of VP24. One possible explanation for these results could be that mutation of the SIM domain in VP24 might disrupt the interaction between VP24 and a deubiquitinase enzyme. It has been recently demonstrated that ubiquitin-specific protease USP7 interacts with SUMOylated proteins, probably through a SIM domain, and reverses its ubiquitination (18). In addition, USP7 has been reported to be involved in virus-host interaction processes (19–22). Therefore, we decided to study the putative interaction between VP24-WT or VP24-SIM and USP7. Endogenous USP7 was immunoprecipitated from HEK-293 cells transfected with HA-VP24-WT or HA-VP24-SIM, and immunoprecipitated proteins were then analyzed by Western blotting using anti-HA antibody. As shown in Fig. 4d, VP24-WT protein interacted with USP7. However, we could not detect an interaction between VP24-SIM and USP7 (Fig. 4d). We then decided to evaluate the putative deubiquitination of VP24 by USP7. First, we evaluated the deubiquitination of in vitro-monoubiquitinated 35S-methionine-labeled in vitro-translated VP24 protein incubated or not incubated with recombinant USP7. As shown in Fig. 4e, incubation with USP7 led to a reduction in the intensity of the VP24-UbKO band in vitro. To further evaluate this possibility, we cotransfected HEK-293 cells together with HA-VP24 and pcDNA, His6-UbKO and pcDNA, His6-UbKO and GFP-USP7, or His6-UbKO and Myc-USP14, and 48 h after transfection, whole-protein extracts and histidine-tagged purified proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody. The band corresponding to the monoubiquitinated VP24 protein detected in the lane transfected with His6-UbKO and pcDNA was almost undetectable in those cells cotransfected with His6-UbKO and GFP-USP7 (Fig. 4f). However, we did not observe any alteration in the intensity of the monoubiquitinated VP24 band in those cells expressing USP14 (Fig. 4f). Altogether, these results indicated that USP7 interacted with VP24 through the SIM domain and downmodulated the conjugation of ubiquitin to VP24.

FIG 4.

Mutation of the SIM domain in VP24 inhibits its interaction with the ubiquitin-specific-processing protease 7 (USP7) and promotes its monoubiquitination. (a) HEK-293 cells were transfected with pcDNA or HA-VP24-SIM, and 24 h after transfection, protein extracts of transfected cells were immunoprecipitated using anti-HA antibody. Immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed using anti-ubiquitin antibody. (b) In vitro ubiquitination assay with UbKO using 35S-methionine-labeled in vitro-translated VP24-WT protein (left panel). HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with VP24-WT and pcDNA or His6-ubiquitin KO. At 36 h after transfection, total cell extracts and histidine-purified proteins were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-HA antibody (right panel). (c) HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with VP24-WT and pcDNA, His6-ubiquitin KO and pcDNA, SUMO2 or SUMO2, and His6-ubiquitin KO, as indicated. At 36 h after transfection, total cell extracts and histidine-purified proteins were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-HA antibody. (d) HEK-293 cells were transfected with HA-VP24-WT or HA-VP24-SIM, and 24 h after transfection, protein extracts of transfected cells were immunoprecipitated using anti-USP7 antibody. Immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed using anti-HA antibody. (e) Incubation of in vitro-ubiquitinated 35S-methionine-labeled in vitro-translated VP24-WT protein with UbKO in presence or absence of recombinant USP7. (f) HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with VP24-WT and pcDNA, His6-ubiquitin KO, His6-ubiquitin KO and GFP-USP7, or His6-ubiquitin KO and Myc-USP14. At 36 h after transfection, total cell extracts and histidine-purified proteins were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-HA antibody.

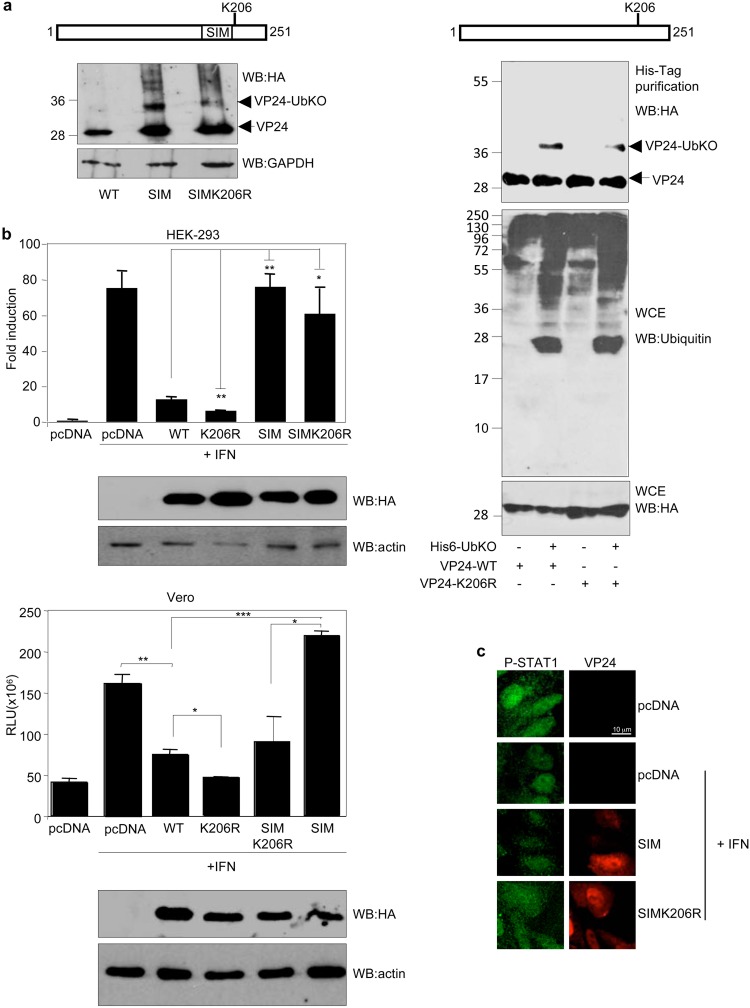

Mutation of lysine residue K206 in VP24 potentiates its IFN-signaling inhibitory activity.

Interestingly, in silico analysis of VP24 protein using the Ubpred program pointed to lysine residue K206 in VP24, just five amino acids away from the SIM domain, as the unique putative ubiquitin conjugation site in VP24. To determine whether lysine K206 had a role in the ubiquitination of VP24, lysine residue K206 in VP24-SIM was mutated to arginine followed by evaluation for the presence of the VP24-UbKO band in cells transfected with VP24-SIM or VP24-SIM-K206R by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 5a (left panel), the intensity of the band corresponding to VP24 conjugated to ubiquitin was reduced in the SIM-K206R mutant relative to that of the band observed in the VP24-SIM-transfected cells, suggesting that K206 is one of the lysine residues involved in ubiquitin conjugation in VP24. To further evaluate this possibility, we generated a VP24 mutant in lysine residue K206 (VP24-K206R) and then evaluated its monoubiquitination in cells. We cotransfected HEK-293 cells with HA-VP24-WT or HA-VP24-K206R together with pcDNA or His6-UbKO, and 36 h after transfection, whole-protein extracts and histidine-tagged proteins purified under denaturing conditions using nickel columns were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody. We observed a slight reduction in the monoubiquitination of VP24-K206R relative to the WT protein (Fig. 5a, right panel), suggesting that lysine residue K206 in VP24 is involved in ubiquitin conjugation. Finally, to determine whether ubiquitin conjugation had a role in the antagonistic activity of VP24, we evaluated the ability of the mutants of VP24 with mutations in lysine residue K206 to inhibit IFN signaling. We cotransfected HEK-293 or Vero cells with ISG54-luc together with beta-galactosidase and pcDNA, HA-VP24-WT, HA-VP24-K206R, HA-VP24-SIM, or HA-VP24-SIMK206R as indicated, and 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with IFN-α for 16 h. Cell extracts were then harvested and assayed for luciferase and beta-galactosidase activity. Interferon treatment induced transactivation of the reporter, and VP24-WT significantly abolished this transactivation (Fig. 5b). The VP24-SIM mutant was not able to inhibit the transactivation of the reporter, as shown above (Fig. 5b). Interestingly, the VP24-K206R mutant had a stronger inhibitory effect on IFN response than the WT protein (Fig. 5b), suggesting that conjugation of ubiquitin to K206 in VP24 had a negative role on the IFN inhibitory activity of the viral protein. Immunofluorescence analysis of phosphorylated STAT1 supported this hypothesis. Among the cells expressing VP24-SIM, 90% (n = 96) were observed to have nuclear phosphorylated STAT1, and in those cells expressing VP24-SIMK206R, the percentage was lower (73%) (n = 49) (Fig. 5c). Taken together, these observations suggest that the interaction of VP24 with SUMO has a positive impact on the ability of VP24 to block STAT1 nuclear accumulation in response to IFN treatment whereas interaction with ubiquitin negatively modulates such activity.

FIG 5.

Mutation of lysine residue K206 in VP24 potentiates its IFN-signaling inhibitory activity. (a) HEK-293 cells were transfected with HA-VP24-SIM or HA-VP24-SIMK206R, and 24 h after transfection, protein extracts of transfected cells were analyzed using anti-HA antibody (left panel). HEK-293 cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding HA-VP24-WT or HA-VP24-K206R together with pcDNA or His6-UbKO and 36 h after transfection whole-protein extracts and histidine-tagged purified proteins were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody (right panel). (b) HEK-293 cells (upper panels) or Vero cells (lower panels) were cotransfected with the luciferase reporter ISG54-luc together with pcDNA, HA-VP24-WT, or the indicated mutants. Cells were treated with IFN-β 24 h after transfection, and luciferase production was analyzed 16 h after treatment. Columns are representative of means of results, and error bars represent standard deviations of results from three biological replicates. Similar results were obtained at least twice. Statistical significance was assessed by a Student's t test. Cell lysates from the experiments were analyzed by Western blotting for HA-VP24 expression (lower panels). (c) Vero cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids, and 24 h after transfection, cells were serum starved for 4 h and then treated with 1,000 U/ml of human IFN-alpha for 30 min or left untreated. Cells were then fixed and immunostained using primary goat anti-HA and mouse anti-phosphorylated STAT1 antibodies and secondary Alexa 488 chicken anti-mouse and Alexa 594 donkey anti-goat antibodies.

DISCUSSION

Here, we show that EBOV exploits the SUMOylation machinery of infected cells to regulate the immune antagonistic function of the minor matrix protein VP24. Our results demonstrate that VP24 is modified by SUMO in vitro and in vivo in both transfected and EBOV-infected cells. In addition, the SUMOylation of VP24 in transfected cells indicates that its posttranslational modification does not require additional EBOV proteins. Moreover, the appearance of a unique double band in the in vitro SUMOylation assay with SUMO1 suggests that only one SUMO molecule is conjugated to VP24 at a time and that the SUMOylated protein may be additionally modified. In silico analysis of the putative SUMOylation sites pointed to lysine residue K14 as one of the lysine residues in VP24 involved in SUMO conjugation. One of the best well-known functions of VP24 is to inhibit the IFN activity (2). This immunomodulatory activity of VP24 has been reported to be mediated at least partially by the interaction with STAT1 (23) and with karyopherin, an interaction that also increases the stability of VP24 (2, 3, 15). We show that a mutant of VP24 in lysine residue K14 has a significantly reduced ability to interact with KPNA5 and to block the IFN activity, exhibits decreased stability, and shows a reduced capacity to inhibit IFN-induced nuclear translocation of phosphorylated STAT1. These results suggest that SUMOylation of VP24 at lysine residue K14 has a role in its interaction with karyopherin contributing to blocking the IFN signaling.

SUMOylated proteins frequently contain SUMO interaction domains (SIM) that allow the noncovalent interaction between the SUMO substrates and SUMO or SUMOylated proteins (6). Here, we show that VP24 also interacts with SUMO in a noncovalent manner and that mutation of the 198LVEL201 domain in VP24 reduces this interaction, indicating that the SIM domain located at positions 198 to 201 in VP24 has a role in the noncovalent interaction between SUMO and VP24. A SIM domain may have an impact on the SUMOylation, subcellular localization, stability, or activity of a protein (6). We did not observe an effect of the SIM domain in the SUMOylation of VP24. However, our data revealed that the SIM domain was essential for the IFN inhibitory activity of VP24, suggesting that the noncovalent interaction with SUMO is indispensable for the immunomodulatory activity of VP24. Although the SIM domain seems to contribute to the VP24-KPNA5 interaction, mutation of the SIM domain did not totally abolish the coimmunoprecipitation of VP24 and KPNA5, suggesting that the noncovalent interaction of SUMO with VP24 may be involved in additional functions of the viral protein. Interestingly, mutation of the SIM domain in VP24 also led to the appearance of a band that is 10 kDa higher than that corresponding to the VP24 protein that was identified as VP24-UbKO protein, suggesting that the interaction of SUMO or a SUMOylated protein with the SIM domain in VP24 negatively modulates the ubiquitination of VP24, a hypothesis that was also supported by the inhibition of VP24 ubiquitination in response to SUMO overexpression.

USP7 is a SUMO deubiquitinase that has been shown to interact with different viral proteins and to regulate the replication of some viruses (18–22). We then hypothesized that USP7 may be the ubiquitin protease that, by interacting with the SIM domain of VP24, induces its deubiquitination. Although, so far, USP7 has not been reported to be SUMOylated, recently, proteomic studies have pointed to USP7 as a putative SUMOylation substrate (24), reinforcing our hypothesis. Furthermore, coimmunoprecipitation studies revealed that VP24-WT protein but not a mutant with a mutation in the SIM domain can interact with USP7, demonstrating the involvement of the SIM domain in VP24-USP7 interaction. Finally, we showed that USP7 decreases the levels of the monoubiquitinated VP24 protein in vitro and in vivo, supporting the idea of a newly recognized form of cooperative SUMO and ubiquitin signaling.

We show that a mutant of VP24 with a mutation in the SIM domain that did not interact with SUMO in a noncovalent manner but covalently interacted with ubiquitin was not able to inhibit IFN signaling, had weaker interaction with KPNA5 than with VP24-WT protein, and had lost its ability to block phosphorylated STAT1 nuclear translocation. Therefore, the noncovalent interaction with SUMO and/or the conjugation to ubiquitin may play a role in the IFN inhibitory activity of VP24. In silico analysis of VP24 pointed to the K206 lysine residue as one ubiquitin conjugation site in VP24. Mutation of this residue did not abolish the conjugation of VP24 to ubiquitin, likely due to the interaction of ubiquitin with additional lysine residues in VP24, as suggested by the two monoubiquitinated bands detected in the monoubiquitination assays. However, we detected a decrease in the levels of the monoubiquitinated protein, suggesting that K206, a lysine residue conserved in all species of the genus Ebolavirus, has a role in the ubiquitin conjugation. Interestingly, mutation of lysine residue K206 in VP24 significantly potentiated the IFN downmodulation activity of the viral protein, indicative of a negative impact of ubiquitin conjugation on the activity of VP24.

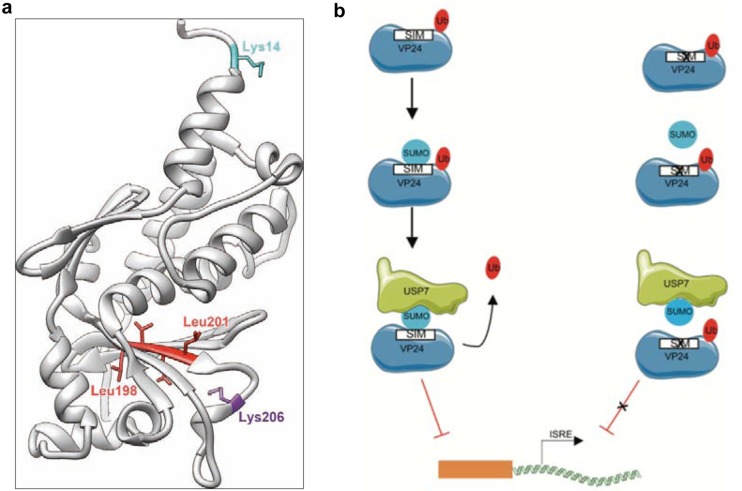

Location of the SUMOylation or ubiquitination sites in the VP24 structure reveals that both lysine residues are on the protein surface (Fig. 6a). Regarding the SIM domain (Fig. 6a), some of the residues that conform to it have been proposed to constitute part of a cavity in the Sudan EBOV VP24 structure (23). In addition, according to X-ray structures of Sudan EBOV VP24 and H/D exchange assays previously reported (23), the VP24 peptidic region adjacent to the SIM domain (residues 181 to 198) is probably involved in flexibility/conformational change under specific conditions. Therefore, we speculate that SUMO may interact with the SIM domain in VP24 through this cavity or in response to a conformational change in the SIM region.

FIG 6.

(a) Structure of VP24 (gray ribbon) with the key residues discussed in this work highlighted. The crystal structure of Zaire Ebolavirus VP24 (PDB ID 4m0q) (15) is depicted. Residues proposed to form a SIM domain are colored in red. The figure was composed using UCSF Chimera (30). (b) Proposed model to explain the regulatory role of ubiquitination and noncovalent SUMO interaction in the IFN-inhibitory activity of VP24.

In summary, these results identify SUMO and ubiquitin as positive and negative regulators of the ability of VP24 to inhibit the signaling cascades of the interferon system, respectively (Fig. 6b), and point to modulation of the VP24-SUMO and VP24-ubiquitin interactions as a novel strategy that may help in the design of new antivirals with the ability to modulate EBOV replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and plasmids.

HeLa cells stably expressing His6-SUMO2, HEK-293, and Vero cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Transfection experiments were performed using polyethylenimine (PEI), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The plasmid encoding HA-tagged VP24 (HA-VP24) was generated by subcloning of the VP24 coding cDNA into the pcMV5-HA plasmid. Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out using the primers listed in Table 1 and HA-VP24. All mutations were verified by sequencing. Expression plasmids pcDNA-His6-SUMO1, pcDNA-Hi6-SUMO2, pcDNA-Ubc9-SV5, and pcDNA-His6-UbKO have been previously reported (25–27).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used in VP24 protein mutagenesis

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| VP24-K14R-F | 5′-CAATCTAATATCGCCCAGAAAGGACCTGGAGAAAG-3′ |

| VP24-K14R-R | 5′-CTTTCTCCAGGTCCTTTCTGGGCGATATTAGATTG-3′ |

| VP24-K142R-F | 5′-GCGAACACAACGTGTCAGGGAACAATTGAGCC-3′ |

| VP24-K142R-R | 5′-GGCTCAATTGTTCCCTGACACGTTGTGTTCGC-3′ |

| VP24-LSLI-ASAA-F | 5′-CAATTGAGCCTAAAAATGGCGTCGGCGGCTCGATCCAATATTCTC-3’ |

| VP24-LSLI-ASAA-R | 5′-GAGAATATTGGATCGAGCCGCCGACGCCATTTTTAGGCTCAATTG-3’ |

| VP24-LGLI-AGAA-F | 5′-CCCTTAGCAGGAGCCGCTGGTGCGGCCTCTGATTGGCTGCTAAC-3’ |

| VP24-LGLI-AGAA-R | 5′-GTTAGCAGCCAATCAGAGGCCGCACCAGCGGCTCCTGCTAAGGG-3’ |

| VP24-LRVI-ARAA-F | 5′-GAATCACCGCTGTGGGCAGCGAGAGCGGCCCTTGCAGCAGGGATAC-3’ |

| VP24-LRVI-ARAA-R | 5′-GTATCCCTGCTGCAAGGGCCGCTCTCGCTGCCCACAGCGGTGATTC-3’ |

| VP24-LVEL-AAEA-F | 5′-GAACTAACATGGGTTTTGCGGCGGAGGCCCAAGAACCCGACAA-3’ |

| VP24-LVEL-AAEA-R | 5′-TTGTCGGGTTCTTGGGCCTCCGCCGCAAAACCCATGTTAGTTC-3’ |

| VP24-LHVV-AHAA-F | 5′-AACAAATTGGATGCTGCACATGCCGCGAACTACAACGGATTG-3’ |

| VP24-LHVV-AHAA-R | 5′-CAATCCGTTGTAGTTCGCGGCATGTGCAGCATCCAATTTGTT-3’ |

| VP24-K206R-F | 5′-CTCCAAGAACCCGACAGATCGGCAATGAACCGC-3′ |

| VP24-K206R-R | 5′-GCGGTTCATTGCCGATCTGTCGGGTTCTTGGAG-3′ |

| VP24-LVEL-K206R-F | 5′-GCCCAAGAACCCGACAGATCGGCAATGAACCGC-3′ |

| VP24-LVEL-K206R-R | 5′-GCGGTTCATTGCCGATCTGTCGGGTTCTTGGGC-3′ |

In vitro transcription/translation.

The in vitro transcription/translation of proteins was performed by using 1 μg of plasmid DNA and a rabbit reticulocyte-coupled transcription/translation system following the instructions of the manufacturer (Promega).

Stability assay.

HEK-293 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids, and 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with cycloheximide (100 μg/ml). At different times after treatment, cells were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody. Band intensities were measured using ImageJ software. VP24 band intensity was normalized to tubulin from each respective time.

In vitro SUMOylation assay.

In vitro SUMO conjugation assays were performed on 35S-methionine-labeled in vitro-transcribed/translated proteins as described previously (28) using recombinant E1 (Biomol, Lausen, Switzerland), Ubc9, and SUMO1 or SUMO2.

In vitro deSUMOylation assay.

In vitro deSUMOylation assays with recombinant GST-SENP1 (Biomol) were performed on VP24-SUMO1 or VP24-SUMO2 as described previously (11).

Histidine purification.

The purification of His-tagged conjugates using Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA)-agarose beads was performed as described previously (11).

GST pulldown assay.

Pulldown experiments were performed with GST-SUMO1 as described previously (29), using 35S-methionine-labeled in vitro-transcribed/translated VP24 WT or mutant proteins.

Reporter assay.

HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with ISG54-luc plasmid, the pcDNA-beta-galactosidase plasmid, and pcDNA, VP24-WT, or mutated VP24 expression plasmids. At 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with 1,500 U/ml human IFN-α for 16 h. Then, the cells were harvested and analyzed. Firefly luciferase values were normalized to beta-galactosidase values. Fold induction for each sample was then determined relative to the normalized luciferase activity value for untreated cells. Statistical significance was assessed using a Student's t test.

Western blotting and antibodies.

For Western blotting, cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), resuspended in SDS-gel loading buffer, and boiled for 5 min. Proteins of total extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Monoclonal antibody against HA (901503) was purchased from BioLegend. Goat anti-HA (A190-138A) antibody was purchased from Bethyl Laboratories. Anti-tubulin (2146), anti-myc tag (2276S), and anti-SUMO2 (4971) antibodies were from Cell Signaling. Anti-GAPDH (anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) (32233), anti-phosphorylated STAT1 (8394), and anti-ubiquitin (8017) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-VP24 antibody (362919) was from Biorbyt. Anti-GFP was from Abcam (1218) or from BioLegend (902601). Anti-USP7 antibody (A300-034A) was purchased from Bethyl Laboratories or from Sigma (PLA0009). Anti-KPNA5 antibody (PA529460) and Alexa 488 chicken anti-mouse antibody (A21200) were from Invitrogen. Alexa 594 donkey anti-goat antibody (ab150136) was from Abcam.

Immunofluorescence assay.

Vero cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids, and 24 h after transfection, cells were serum starved for 4 h and then treated or not with 1,000 U/ml of human IFN-alpha for 30 min. Cells were then fixed and immunostained as previously described (11).

Infection.

HeLa cells at 90% confluence were infected with EBOV (Ebola virus/H. sapiens-tc/COD/Yambuku-Mayinga) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. All infection experiments were carried out by experienced personnel wearing positive-pressure protection suits at the biosafety level 4 (BSL4) laboratory of the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine in Hamburg.

In vitro ubiquitylation assay.

35S-methionine-labeled in vitro-transcribed/translated VP24 were incubated in a 10-μl reaction mixture (50 mM Tris [pH 7.6], 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ATP, 10 mM creatine phosphate, 3.5 U/ml of creatine kinase, 0.6 U/ml of inorganic pyrophosphatase), 10 ng human E1, 12 ng E2 (UbcH5), and 10 μg recombinant ubiquitin-KO in an apparatus that included an ATP regenerating system. After incubation at 37°C for 120 min, the reaction products were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography.

Immunoprecipitation assay.

Cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) or BC-100 buffer at 4°C, centrifuged at 15,800 × g for 10 min, and immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C after addition of the specified antibody and 30 μl of 50% protein G-Sepharose (Life Technologies). Beads were then washed four times with lysis buffer and resuspended in 30 μl of loading buffer.

Data availability.

The data sets generated during the present study are available from C. Rivas upon request.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding at the laboratory of C.R. is provided by Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities and FEDER (BFU-2017-88880-P). C.R. also acknowledges grants GRC GI-2119 (Xunta de Galicia) and SAF2017-90900-REDT (UBIRed Program). S.V. is a predoctoral fellow funded by Xunta de Galicia. M.B.-M. is a postdoctoral fellow funded by Xunta de Galicia (Consellería de Cultura, Educación e Ordenación Universitaria). A.E.M. is the recipient of a fellowship of the Spanish FPI program. This work was partially funded by the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF TTU 01.702_00 to C.M.-F.). R.B. and J.D.S. acknowledge grants BFU2017-84653-P (MINECO/FEDER, EU), SEV-2016-0644 (Severo Ochoa Excellence Program), 765445-EU (UbiCODE Program), and SAF2017-90900-REDT (UBIRed Program). C.S.M. acknowledges grant BFU2016-74868-P.

We declare that we have no competing financial interests.

S.V., A.E.M., R.S., V.P., S.G.-M., Y.H.B., D.R., M.T.R., and M.B.-M. conducted the experiments. S.V., C.M.-F., and C.R. designed the experiments. C.R. wrote the paper. S.V., C.S.M., M.S.R., R.B., D.R., J.D.S., and C.R. analyzed the data. D.R., M.S.R., R.B., J.D.S., C.S.M., and C.M.-F. provided critical revisions of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mateo M, Reid SP, Leung LW, Basler CF, Volchkov VE. 2010. Ebolavirus VP24 binding to karyopherins is required for inhibition of interferon signaling. J Virol 84:1169–1175. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01372-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reid SP, Leung LW, Hartman AL, Martinez O, Shaw ML, Carbonnelle C, Volchkov VE, Nichol ST, Basler CF. 2006. Ebola virus VP24 binds karyopherin alpha1 and blocks STAT1 nuclear accumulation. J Virol 80:5156–5167. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02349-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reid SP, Valmas C, Martinez O, Sanchez FM, Basler CF. 2007. Ebola virus VP24 proteins inhibit the interaction of NPI-1 subfamily karyopherin alpha proteins with activated STAT1. J Virol 81:13469–13477. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01097-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hochstrasser M. 2009. Origin and function of ubiquitin-like proteins. Nature 458:422–429. doi: 10.1038/nature07958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flotho A, Melchior F. 2013. Sumoylation: a regulatory protein modification in health and disease. Annu Rev Biochem 82:357–385. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061909-093311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gareau JR, Reverter D, Lima CD. 2012. Determinants of small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 (SUMO1) protein specificity, E3 ligase, and SUMO-RanGAP1 binding activities of nucleoporin RanBP2. J Biol Chem 287:4740–4751. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.321141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Praefcke GJ, Hofmann K, Dohmen RJ. 2012. SUMO playing tag with ubiquitin. Trends Biochem Sci 37:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calistri A, Munegato D, Carli I, Parolin C, Palu G. 2014. The ubiquitin-conjugating system: multiple roles in viral replication and infection. Cells 3:386–417. doi: 10.3390/cells3020386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowrey AJ, Cramblet W, Bentz GL. 2017. Viral manipulation of the cellular sumoylation machinery. Cell Commun Signal 15:27. doi: 10.1186/s12964-017-0183-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang TH, Kubota T, Matsuoka M, Jones S, Bradfute SB, Bray M, Ozato K. 2009. Ebola Zaire virus blocks type I interferon production by exploiting the host SUMO modification machinery. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000493. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baz-Martínez M, El Motiam A, Ruibal P, Condezo GN, de la Cruz-Herrera CF, Lang V, Collado M, San Martín C, Rodríguez MS, Muñoz-Fontela C, Rivas C. 2016. Regulation of Ebola virus VP40 matrix protein by SUMO. Sci Rep 6:37258. doi: 10.1038/srep37258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bharaj P, Atkins C, Luthra P, Giraldo MI, Dawes BE, Miorin L, Johnson JR, Krogan NJ, Basler CF, Freiberg AN, Rajsbaum R. 24 August 2017, posting date The host E3-ubiquitin ligase TRIM6 ubiquitinates the Ebola virus VP35 protein and promotes virus replication. J Virol. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00833-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han Z, Sagum CA, Takizawa F, Ruthel G, Berry CT, Kong J, Sunyer JO, Freedman BD, Bedford MT, Sidhu SS, Sudol M, Harty RN. 27 September 2017, posting date Ubiquitin ligase WWP1 interacts with Ebola virus VP40 to regulate egress. J Virol. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00812-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han Z, Boshra H, Sunyer JO, Zwiers SH, Paragas J, Harty RN. 2003. Biochemical and functional characterization of the Ebola virus VP24 protein: implications for a role in virus assembly and budding. J Virol 77:1793–1800. doi: 10.1128/jvi.77.3.1793-1800.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu W, Edwards MR, Borek DM, Feagins AR, Mittal A, Alinger JB, Berry KN, Yen B, Hamilton J, Brett TJ, Pappu RV, Leung DW, Basler CF, Amarasinghe GK. 2014. Ebola virus VP24 targets a unique NLS binding site on karyopherin alpha 5 to selectively compete with nuclear import of phosphorylated STAT1. Cell Host Microbe 16:187–200. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwarz TM, Edwards MR, Diederichs A, Alinger JB, Leung DW, Amarasinghe GK, Basler CF. 31 January 2017, posting date VP24-karyopherin alpha binding affinities differ between ebolavirus species, influencing interferon inhibition and VP24 stability. J Virol. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01715-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerscher O. 2007. SUMO junction—what’s your function? New insights through SUMO-interacting motifs. EMBO Rep 8:550–555. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lecona E, Rodriguez-Acebes S, Specks J, Lopez-Contreras AJ, Ruppen I, Murga M, Muñoz J, Mendez J, Fernandez-Capetillo O. 2016. USP7 is a SUMO deubiquitinase essential for DNA replication. Nat Struct Mol Biol 23:270–277. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chavoshi S, Egorova O, Lacdao IK, Farhadi S, Sheng Y, Saridakis V. 2016. Identification of Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV) vIRF1 protein as a novel interaction partner of human deubiquitinase USP7. J Biol Chem 291:6281–6291. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.710632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Everett RD, Meredith M, Orr A, Cross A, Kathoria M, Parkinson J. 1997. A novel ubiquitin-specific protease is dynamically associated with the PML nuclear domain and binds to a herpesvirus regulatory protein. EMBO J 16:1519–1530. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holowaty MN, Zeghouf M, Wu H, Tellam J, Athanasopoulos V, Greenblatt J, Frappier L. 2003. Protein profiling with Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen-1 reveals an interaction with the herpesvirus-associated ubiquitin-specific protease HAUSP/USP7. J Biol Chem 278:29987–29994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303977200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jager W, Santag S, Weidner-Glunde M, Gellermann E, Kati S, Pietrek M, Viejo-Borbolla A, Schulz TF. 2012. The ubiquitin-specific protease USP7 modulates the replication of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latent episomal DNA. J Virol 86:6745–6757. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06840-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang AP, Bornholdt ZA, Liu T, Abelson DM, Lee DE, Li S, Woods VL Jr, Saphire EO. 2012. The Ebola virus interferon antagonist VP24 directly binds STAT1 and has a novel, pyramidal fold. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002550. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lumpkin RJ, Gu H, Zhu Y, Leonard M, Ahmad AS, Clauser KR, Meyer JG, Bennett EJ, Komives EA. 2017. Site-specific identification and quantitation of endogenous SUMO modifications under native conditions. Nat Commun 8:1171. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01271-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desterro JM, Rodriguez MS, Hay RT. 1998. SUMO-1 modification of IkappaBalpha inhibits NF-kappaB activation. Mol Cell 2:233–239. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hjerpe R, Aillet F, Lopitz-Otsoa F, Lang V, England P, Rodriguez MS. 2009. Efficient protection and isolation of ubiquitylated proteins using tandem ubiquitin-binding entities. EMBO Rep 10:1250–1258. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vertegaal AC, Andersen JS, Ogg SC, Hay RT, Mann M, Lamond AI. 2006. Distinct and overlapping sets of SUMO-1 and SUMO-2 target proteins revealed by quantitative proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics 5:2298–2310. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600212-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.González-Santamaría J, Campagna M, García MA, Marcos-Villar L, González D, Gallego P, Lopitz-Otsoa F, Guerra S, Rodríguez MS, Esteban M, Rivas C. 2011. Regulation of vaccinia virus E3 protein by small ubiquitin-like modifier proteins. J Virol 85:12890–12900. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05628-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marcos-Villar L, Lopitz-Otsoa F, Gallego P, Muñoz-Fontela C, González-Santamaría J, Campagna M, Shou-Jiang G, Rodriguez MS, Rivas C. 2009. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus protein LANA2 disrupts PML oncogenic domains and inhibits PML-mediated transcriptional repression of the survivin gene. J Virol 83:8849–8858. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00339-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. 2004. UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated during the present study are available from C. Rivas upon request.