Abstract

Simple Summary

Increasing litter size is critical for the intensive sheep production system. Genetic marker-assisted selection (MAS) based on proven molecular indicators could enhance the efficacy of sheep selection with improving litter size traits. Many single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) linked with litter size in Hu sheep and Small-tailed Han sheep have been identified. However, they usually explain a small portion of genetic variation and additional genetic markers linked with litter size have not been found. The present study investigated the potential SNPs in ten genes as candidate markers for improved litter size in sheep. As a result, nine SNPs in six out of ten genes can be served as useful genetic markers to improve the selection of litter size since they are significantly associated with litter size either in Hu sheep or Small-tailed Han sheep. Further, a combined haplotypes analysis of the two loci (LIFR: g.35862868C>T and LIFR: g.35862947G>T) revealed that H2H3 (CTTT) combined haplotypes had the largest litter size than the rest combined haplotypes and more than those with either mutation alone in Small-tailed Han sheep. Our knowledge is essential to implement the MAS in sheep and further to increase the profitability in the sheep industry.

Abstract

Hu sheep and Small-tailed Han sheep are the most widely raised and most famous maternal sheep breeds in China, which are known for precocious puberty, perennial oestrus and high fecundity (1–6 lambs each parity). Therefore, it is crucial to increase litter size of these two breeds for intensive sheep industry. The objective of this study was to identify potential genetic markers linked with sheep litter size located at ten genes. This study collected blood sample of 537 Hu sheep and 420 Small-tailed Han sheep with litter size of first parity. The average litter sizes in Hu sheep and Small-tailed Han sheep were 2.21 and 1.93. DNA-pooling sequencing method was used for detecting the potential single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in ten genes related to follicle development and female reproduction. SNPscan® was used for individually genotyping. As a result, a total of 78 putative SNPs in nine out of ten candidate genes (except NOG) were identified. In total, 50 SNPs were successfully genotyped in Hu sheep and Small-tailed Han sheep. After quality control, a total of 42 SNPs in Hu sheep and 44 SNPs in Small-tailed Han sheep were finally used for further analysis. Association analysis revealed that nine SNPs within six genes (KIT: g.70199073A>G, KITLG: g.124520653G>C, ADAMTS1: g.127753565T>C, ADAMTS1: g.127754640G>T, NCOA1: g.31928165C>T, NCOA1: g.32140565G>A, LIFR: g.35862868C>T, LIFR: g.35862947G>T and NGF: g.91795933T>C) were significantly associated with litter size in Hu sheep or Small-tailed Han sheep. A combined haplotypes analysis of the two loci (LIFR: g.35862868C>T and LIFR: g.35862947G>T) revealed that H2H3 (CTTT) combined haplotypes had the largest litter size than the rest combined haplotypes and more than those with either mutation alone in Small-tailed Han sheep. Taken together, our study suggests that nine significant SNPs in six genes can be served as useful genetic markers for MAS in sheep.

Keywords: MAS, SNP, litter size, sheep, SNPscan

1. Introduction

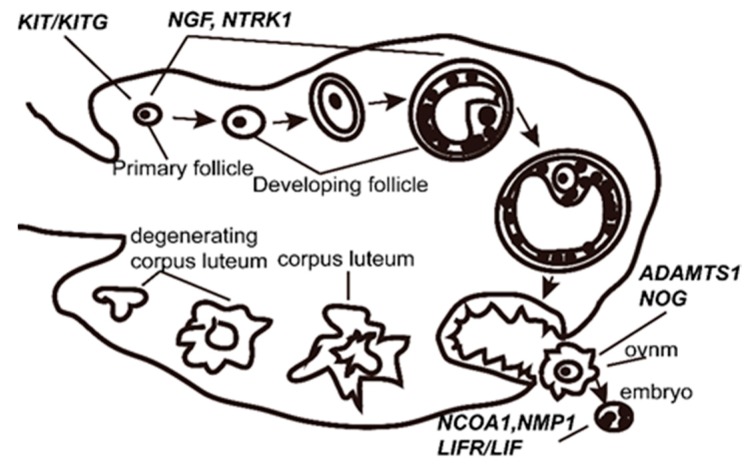

Litter size is one of the most important economic traits because it has a noticeable impact on profitability in the sheep industry. If specific genetic makers associated with litter size are identified, marker-assisted selection (MAS) can be then used to improve the selection of litter size. Genomic selection is efficient but severely unaffordable in large sample size. Finding single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with litter size in candidate gene is an alternative method to improve the litter size in case of a limited budget. As well known, ovulation rate and embryo survival are directly linked to sheep litter size [1]. Therefore, it is an effective way to scan SNPs in genes with known reproductive physiology functions. Based on current literatures, ten genes (NGF, NTRK1, KIT, KITLG, LIF, LIFR, NCOA1, ADAMTS1, NPM1, and NOG) with known reproductive physiology functions (Figure 1, Supplementary Materials Table S1) in animals were selected as potential candidate genes for sheep litter size. Specifically, KIT, KITG, NCF, and NTRK1 play roles in follicle growth [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in KIT were linked with goat litter size [9]. Similarly, ten loci in KITLG were significantly associated with goat litter size [10,11,12,13]. ADAMTS1 and NOG were crucial for ovulation [14,15,16,17,18] and a mutation in ADAMTS1 was notably linked with litter size in a new Qingping female line [19]. NCOA1 was essential for embryo survival [20]. A significant association of SNPs in the NCOA1 gene with litter size in Icelandic sheep has been reported [21]. LIFR, LIF and NMP1 [22,23,24,25,26,27,28] play a vital role in embryo implantation. LIF linked with litter size in pigs has been reported [29].

Figure 1.

Reproductive physiology functions of the ten candidate genes.

In China, the population size of domesticated sheep was 116.35 million in 2017 and sheep meat accounts for 14.38 % for the meat production in the ruminant sector (http://www.fao.org/faostat/, last access date: 31 October 2019). Hu sheep and Small-tailed Han sheep are two majors, widely used high-fecundity sheep breeds for intensive sheep production system (house feeding) in China. The estimated inventory of Hu sheep and Small-tailed Han sheep were approximately four million and five million, respectively. These two breeds usually used as female parents crossing with elite ram breeds, e.g., polled Dorset, to produce meat.

Despite the relatively clear characterization of the roles of these ten genes in influencing the reproductive biological process, the assessment of these candidate genes for the genetic selection of sheep litter size has not been conducted extensively and systematically, particularly in Hu sheep and Small-tailed Han sheep. Our hypothesis for this study was that the potential SNPs in above mentioned ten candidate genes may be linked with litter size in Hu sheep and Small-tailed Han sheep. Thus, the objectives of this study were to scan SNPs in these ten genes and to investigate the association of SNPs with litter size in Hu sheep (n = 537) and Small-tailed Han sheep (n = 420). Our findings may serve as useful genetic markers for Hu sheep and Small-tailed Han sheep.

2. Materials and Methods

The experimental protocols followed the guidelines stated in the Guide for the Use of Animal Subjects in Lanzhou University and the Rules and Regulations of Experimental Field Management Protocols (file No: 2010-1 and 2010-2), which were approved by Lanzhou University.

2.1. Phenotypic Data Collection and DNA Extraction

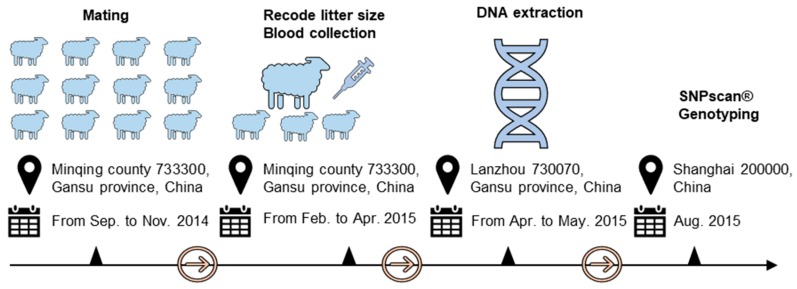

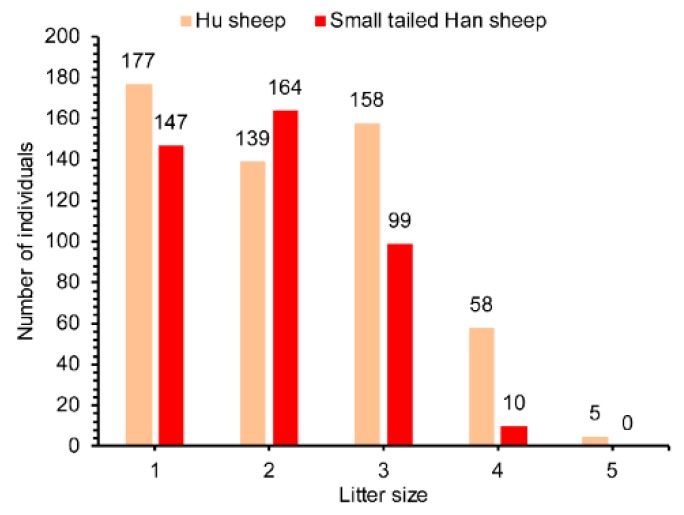

Increasing litter size is critical for intensive sheep production system (house feeding). Two sheep breeds, Hu sheep and Small-tailed Hans sheep were selected in this study because these two breeds are widely used in China for their high fecundity. In the current study, all ewes (Hu sheep and Small-tailed Han sheep) were raised under the same management conditions and were mated from September to December 2014, which was a short-day period in Minqing, Gansu province, China. Blood samples of 957 ewes with litter size recorded at first parity from February to April 2015 were collected at Minqing Zhongtian Sheep Industry Co., Ltd. (Minqing, Gansu Province, P.R. China), including 537 Hu sheep and 420 Small-tailed Han sheep. The experimental protocol across times was shown in Figure 2. Data for the phenotype of litter size records in Hu sheep and Small-tailed Han sheep are shown in Figure 3. The litter size ranged from one to five in Hu sheep and one to four in Small-tailed Han sheep. The average litter sizes in Hu sheep and Small-tailed Han sheep were 2.21 and 1.93. Genomic DNA was extracted using a phenol-chloroform method [30] and then dissolved in double-distilled water and stored at −20 °C.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the experimental protocol across times.

Figure 3.

Frequency distribution of litter size in Hu sheep and Small-tailed Han sheep.

2.2. Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Detection and Genotyping

A total of ten DNA pools were constructed for two sheep breeds (each five) to identify potential SNPs in the ten genes analyzed. Each DNA pool comprised ten individuals which were randomly selected balanced across all different litter sizes, as described in Table 1. Different DNA pools contain the different individuals. A total of 119 paired primers were designed to amplify all exons and flanking regions of each gene (Supplementary Materials Table S1). The PCR reaction mixture was 25 μL, containing 1 μL pooled DNA, 0.4 μL forward primers, 0.4 μL reverse primers, 12.5 μL 2× Taq PCR MasterMix and 10.7 μL double-distilled water. The PCR protocol was 5 min at 94 °C for initial denaturing followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, annealing for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s, and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The purified PCR products were sequenced using an ABI 3730XL DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and the sequences were compared using DNAstar to detect putative SNPs. The identified SNPs were individually genotyped by the SNPscan® method (Genesky Biotechnologies Inc., Shanghai, China), which was based on double ligation and multiplex fluorescence PCR [31]. Three DNA samples were randomly selected from 957 samples to genotype twice, and two blank samples (double-distilled water) were also used to eliminate cross-contamination.

Table 1.

Sample constitution in each DNA pool balanced across different litter sizes.

| Sheep Breed | Litter Size | Total Samples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Hu sheep (sample size) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 10 |

| Small-tailed Han sheep (sample size) | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 10 |

2.3. Population Parameter Calculation and Quality Control

The SnpReady R package [32] was used to calculate the allele frequencies, minor allele frequency (MAF), polymorphic information content (PIC), expected heterozygosity (He), and observed heterozygosity (Ho) and to implement the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test. The formulas used to estimate population parameters were well descripted in the manual of SnpReady R package [32]. SNP was excluded for further analysis if its MAF was smaller than 0.05 and/or it seriously deviated from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (p < 0.001).

2.4. Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Association Analysis

A linear model was used to test the single SNP effect on the litter size in each sheep breed:

| L = 1n μ + G + e | (1) |

where L was an n × 1 vector of the litter size (Hu sheep, n = 537; Small-tailed Han sheep, n = 420), 1n was an n × 1 vector with all elements equal to 1, μ was the overall mean, G was fixed effects corresponding to SNPs, and e was an n × 1 vector of random residual effect. Differences in mean litter size among genotypes were tested using the LSD test in the agricolae R package [33]. P < 0.05 was to be considered significant. P < 0.01 was considered to be highly significant. Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple testing between genotype groups.

2.5. The Haplotype Analysis

In the current study, only the significant SNPs in the same gene in each sheep breed were used to estimate the extent of linkage disequilibrium (LD) and haplotype blocks. Two significant SNPs (ADAMTS1: g.127753565T>C and ADAMTS1: g.127754640T>G) in Hu sheep and four significant SNPs (NCOA1: g.31928165C>T, NCOA1: g.32140565G>A, LIFR: g.35862868C>T and LIFR: g.35862947G>T) in Small-tailed Han sheep meet this precondition and were used for further analysis. The extent of LD between significant SNP pairs and haplotype blocks was estimated using the Haploview 4.2 software [34]. The model of association analysis between combined haplotypes and litter size was as follows in Formula (1) except that the genotype (G) was replaced by combined haplotypes. Numbers less than 12 of the combined haplotypes were excluded from the association analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Genotyping and Quality Control

A total of 78 putative SNPs in nine candidate genes (except NOG) were identified by DNA pooling sequencing (Supplementary Materials Table S2). After evaluating the ligand primers, 50 out of 78 SNPs were genotyped using the SNPscan® method (Supplementary Table S2). The genotypic correlation coefficient of three pairs of technical repeats equal to one and no genotyping signals were detected in two blank samples, indicating that the SNPscan® method is reliable. Eight SNPs (KIT: g.70224398T>A, ADAMTS1: g.127751615C>T, ADAMTS1: g.127753643C>T, ADAMTS1: g.127756130G>A, NPM1: g.3247135T>G, NPM1: g.3247450C>T, ADAMTS1: g.127753727C>T; and LIF: g.68801067C>T) in Hu sheep and six SNPs in Small-tailed Han sheep (KIT: g.70224398T>A, ADAMTS1: g.127756130G>A, NPM1: g.3247135T>G, NPM1: g.3247450C>T, ADAMTS1: g.127753727C>T, and LIFR: g.35867028T>C) were excluded for further analysis because their MAF were smaller than 0.05 and/or they seriously deviated from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (p < 0.001). Finally, a total of 42 SNPs in Hu sheep and 44 SNPs in Small-tailed Han sheep were used for further analysis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Population genetic parameters of the 42 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in Hu sheep (HUS) and 44 SNPs in Small-tailed Han sheep (STH).

| SNP ID | Breed | MA | MAF | He | Ho | PIC | χ2 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KIT: g.70199073A>G | HUS | G | 0.19 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.6442 |

| STH | G | 0.28 | 0.40 | 0.44 | 0.32 | 4.10 | 0.0430 | |

| KITLG: g.124520653G>C | HUS | C | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.9410 |

| STH | C | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 1.31 | 0.2530 | |

| ADAMTS1: g.127751615C>T | HUS | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| STH | T | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.6729 | |

| ADAMTS1: g.127753565T>C | HUS | C | 0.37 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 2.05 | 0.1519 |

| STH | C | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.37 | 1.93 | 0.1652 | |

| ADAMTS1: g.127753643C>T | HUS | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| STH | T | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.45 | 0.5023 | |

| ADAMTS1: g.127754640T>G | HUS | T | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.37 | 3.19 | 0.0740 |

| STH | G | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 0.9216 | |

| NCOA1: g.31928165C>T | HUS | T | 0.40 | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.36 | 2.89 | 0.0891 |

| STH | T | 0.33 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.35 | 0.10 | 0.7507 | |

| NCOA1: g.31928230C>T | HUS | T | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.83 | 0.3630 |

| STH | T | 0.25 | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 1.71 | 0.1916 | |

| NCOA1: g.32072394C>T | HUS | T | 0.19 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.92 | 0.3371 |

| STH | T | 0.22 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.28 | 1.54 | 0.2142 | |

| NCOA1: g.32116034A>G | HUS | G | 0.22 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 1.60 | 0.2064 |

| STH | G | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.27 | 0.75 | 0.3867 | |

| NCOA1: g.32140565G>A | HUS | A | 0.11 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 2.84 | 0.0922 |

| STH | A | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.03 | 0.8540 | |

| NCOA1: g.32140837T>C | HUS | C | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 2.13 | 0.1448 |

| STH | C | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.29 | 1.28 | 0.2589 | |

| NPM1: g.3245714T>C | HUS | C | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.04 | 0.8432 |

| STH | T | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.46 | 0.37 | 2.68 | 0.1019 | |

| NPM1: g.3245741C>T | HUS | T | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.37 | 0.07 | 0.7901 |

| STH | C | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 0.91 | 0.3407 | |

| NPM1: g.3245965C>T | HUS | T | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 0.9257 |

| STH | C | 0.45 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.37 | 3.05 | 0.0808 | |

| NPM1: g.3246266T>G | HUS | G | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 3.12 | 0.0774 |

| STH | G | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 6.62 | 0.0101 | |

| NPM1: g.3247499A>T | HUS | T | 0.29 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 2.04 | 0.1534 |

| STH | T | 0.31 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.34 | 0.65 | 0.4218 | |

| NPM1: g.3251189A>T | HUS | T | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.00 | 0.9940 |

| STH | T | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.77 | 0.3811 | |

| LIF: g.68801067C>T | HUS | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| STH | T | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 1.63 | 0.2019 | |

| LIF: g.68816215C>T | HUS | T | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.59 | 0.4418 |

| STH | T | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.9715 | |

| LIFR: g.35813711C>T | HUS | T | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.5646 |

| STH | T | 0.32 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.34 | 0.03 | 0.8658 | |

| LIFR: g.35814094C>T | HUS | T | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.37 | 0.59 | 0.4418 |

| STH | T | 0.32 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.34 | 0.10 | 0.7568 | |

| LIFR: g.35813931G>A | HUS | T | 0.19 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 3.33 | 0.0680 |

| STH | T | 0.29 | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 3.88 | 0.0489 | |

| LIFR: g.35813935A>G | HUS | G | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 1.22 | 0.2690 |

| STH | G | 0.35 | 0.46 | 0.41 | 0.35 | 4.52 | 0.0334 | |

| LIFR: g.35817147A>G | HUS | G | 0.17 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.97 | 0.3250 |

| STH | G | 0.27 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.9578 | |

| LIFR: g.35817247G>A | HUS | A | 0.17 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.97 | 0.3250 |

| STH | A | 0.27 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.9888 | |

| LIFR: g.35835329G>A | HUS | A | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.36 | 0.40 | 0.5280 |

| STH | A | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.37 | 2.54 | 0.1113 | |

| LIFR: g.35835474G>T | HUS | T | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.7117 |

| STH | T | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 0.66 | 0.4154 | |

| LIFR: g.35841608T>C | HUS | C | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.27 | 0.6044 |

| STH | C | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 1.07 | 0.3022 | |

| LIFR: g.35845633T>C | HUS | T | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.79 | 0.3743 |

| STH | C | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 1.64 | 0.2009 | |

| LIFR: g.35847837A>G | HUS | G | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.72 | 0.3954 |

| STH | G | 0.25 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 0.43 | 0.5103 | |

| LIFR: g.35847864A>T | HUS | T | 0.41 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.37 | 0.89 | 0.3463 |

| STH | T | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.54 | 0.37 | 5.34 | 0.0209 | |

| LIFR: g.35848079G>A | HUS | A | 0.38 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.36 | 0.13 | 0.7151 |

| STH | A | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 2.27 | 0.1318 | |

| LIFR: g.35848108A>G | HUS | G | 0.41 | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.37 | 1.28 | 0.2571 |

| STH | G | 0.45 | 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.37 | 8.43 | 0.0037 | |

| LIFR: g.35847912C>T | HUS | T | 0.41 | 0.48 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.03 | 0.8553 |

| STH | T | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.37 | 2.63 | 0.1047 | |

| LIFR: g.35851829T>C | HUS | C | 0.22 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.9701 |

| STH | C | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.5640 | |

| LIFR: g.35853589T>C | HUS | C | 0.35 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.8470 |

| STH | C | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.37 | 0.70 | 0.4014 | |

| LIFR: g.35853637T>G | HUS | G | 0.30 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0.6765 |

| STH | G | 0.37 | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 2.46 | 0.1167 | |

| LIFR: g.35853852T>C | HUS | C | 0.22 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.98 | 0.3211 |

| STH | C | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.9251 | |

| LIFR: g.35862868C>T | HUS | T | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.06 | 0.8061 |

| STH | T | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.37 | 4.63 | 0.0314 | |

| LIFR: g.35862947G>T | HUS | T | 0.45 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.09 | 0.7616 |

| STH | G | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.37 | 5.07 | 0.0244 | |

| LIFR: g.35867028T>C | HUS | C | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.08 | 0.7815 |

| STH | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| NGF: g.91795933T>C | HUS | C | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 0.79 | 0.3734 |

| STH | C | 0.40 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.37 | 0.72 | 0.3961 | |

| NTRK1: g.105276945C>T | HUS | T | 0.34 | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 3.18 | 0.0745 |

| STH | T | 0.17 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.24 | 3.05 | 0.0807 | |

| NTRK1: g.105288550C>G | HUS | C | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 6.71 | 0.0096 |

| STH | C | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 5.47 | 0.0193 |

Note: MA: Minor allele; MAF: Minor allele frequency; PIC: Polymorphic information content; He: Expected heterozygosity; Ho: Observed heterozygosity; χ2 and p value denote the chi-square value and p-value of Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test; “-” denotes information is not available.

3.2. Population Genetic Parameters

The MAF, He, Ho, PIC and Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium test p-values are summarized in Table 2. The MAF in Hu sheep ranged from 0.06 to 0.48, and that in Small-tailed Han sheep ranged from 0.11 to 0.49. The minimum (maximum) values of He were 0.12 (0.5) and 0.19 (0.5) in Hu sheep and Small-tailed Han sheep, respectively. The min (max) value of Ho was 0.12 (0.37) and 0.19 (0.56) in Hu sheep and Small-tailed Han sheep. Nine SNPs in Hu sheep (KITLG: g.124520653G>C, NCOA1: g.31928230C>T, NCOA1: g.32140565G>A, LIF: g.68816215C>T, LIFR: g.35817147A>G, LIFR: g.35817247G>A, LIFR: g.35835474G>T, LIFR: g.35841608T>C, and LIFR: g.35847837A>G) and seven SNPs in Small-tailed Han sheep (KITLG: g.124520653G>C, ADAMTS1: g.127751615C>T, LIF: g.68801067C>T, LIF: g.68816215C>T, LIFR: g.35845633T>C, LIFR: g.35853852T>C, and NTRK1: g.105276945C>T) with low polymorphic status (PIC < 0.25) were observed. The other SNPs had moderate (0.25 ≤ PIC < 0.5) or high polymorphic (PIC ≥ 0.5) status. One SNP (NTRK1: g.105288550C>G) in Hu sheep and nine SNPs (KIT: g.70199073A>G, NPM1: g.3246266T>G, LIFR: g.35813931G>A, LIFR: g.35813935A>G, LIFR: g.35847864A>T, LIFR: g.35848108A>G, LIFR: g.35862868C>T, LIFR: g.35862947G>T, and NTRK1: g.105288550C>G) in Small-tailed Han sheep deviated from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (p < 0.05).

3.3. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms Associated with Litter Size

Table 3 details the significant associations between the tested SNPs and litter size. Single SNP association analysis showed that three SNPs (KITLG: g.124520653G>C, ADAMTS1: g.127754640T>G, and ADAMTS1: g.127753565T>C) were significantly associated with litter size in Hu sheep, four SNPs (NCOA1: g.31928165C>T, NCOA1: g.32140565G>A, LIFR: g.35862947G>T, and NGF: g.91795933T>C) were significantly associated with litter size in Small-tailed Han sheep, two SNPs (KIT: g.70199073A>G and LIFR: g.35862868C>T) were strongly associated with litter size in Small-tailed Han sheep. LIFR: g.35862868C>T was the most significant locus in Small-tailed Han sheep (p = 0.0054). In this locus, sheep with the TT and CT genotypes were significantly greater than CC genotype carriers on litter size, which could be observed with overall litters size 0.33 and 0.29 greater than CC genotype carriers, respectively. Overall, nine SNPs (KIT: g.70199073A>G, KITLG: g.124520653G>C, ADAMTS1: g.127753565T>C, ADAMTS1: g.127754640T>G, NCOA1: g.31928165C>T, NCOA1: g.32140565G>A, LIFR: g.35862868C>T, LIFR: g.35862947G>T, and NGF: g.91795933T>C) were significantly associated with litter size in at least one sheep population (Table 3). The remaining 36 SNPs were not significantly associated with litter size in any population (Supplementary Materials Table S3).

Table 3.

Associations between the nine single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and litter size in Hu sheep and Small-tailed Han sheep.

| SNP ID | Gene Symbol | Genotype | Hu Sheep | Small-Tailed Han Sheep | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean ± S.D. | N | Mean ± S.D. | |||

| KIT: g.70199073A>G |

KIT (intron 2) |

AA | 354 | 2.25 ± 1.05 | 211 | 1.88 ± 0.78b |

| GA | 166 | 2.13 ± 1.02 | 185 | 1.94 ± 0.85ab | ||

| GG | 17 | 2.12 ± 1.32 | 24 | 2.42 ± 0.83a | ||

| p-value | 0.42 | 0.00945 ** | ||||

| KITLG: g.124520653G>C |

KITLG (intron 9) |

CC | 6 | 3.17 ± 0.75a | 4 | 1.50 ± 0.58 |

| GC | 100 | 2.10 ± 1.11b | 97 | 1.93 ± 0.79 | ||

| GG | 431 | 2.22 ± 1.03ab | 319 | 1.94 ± 0.84 | ||

| p-value | 0.0461 * | 0.568 | ||||

| ADAMTS1: g.127753565T>C |

ADAMTS1 (exon 5) Ser→Ser |

CC | 66 | 2.24 ± 1.02ab | 114 | 2 ± 0.79 |

| CT | 266 | 2.09 ± 1.02b | 223 | 1.93 ± 0.85 | ||

| TT | 205 | 2.35 ± 1.07a | 83 | 1.84 ± 0.80 | ||

| p-value | 0.0262 * | 0.42 | ||||

| ADAMTS1: g.127754640G>T |

ADAMTS1 (intron 7) |

GG | 137 | 2.39 ± 1.07a | 86 | 1.88 ± 0.79 |

| GT | 288 | 2.10 ± 1.01b | 207 | 1.94 ± 0.83 | ||

| TT | 111 | 2.25 ± 1.11ab | 127 | 1.95 ± 0.84 | ||

| p-value | 0.0297* | 0.817 | ||||

| NCOA1: g.31928165C>T |

NCOA1 (intron 1) |

CC | 184 | 2.28 ± 1.09 | 185 | 1.98 ± 0.86a |

| CT | 276 | 2.13 ± 1.01 | 189 | 1.97 ± 0.79a | ||

| TT | 76 | 2.3 ± 1.08 | 45 | 1.60 ± 0.75b | ||

| p-value | 0.217 | 0.0158* | ||||

| NCOA1: g.32140565G>A |

NCOA1 (intron 21) |

AA | 3 | 3.00 ± 1.70 | 16 | 1.38 ± 0.50b |

| GA | 116 | 2.25 ± 1.02 | 135 | 2.02 ± 0.84a | ||

| GG | 418 | 2.19 ± 1.05 | 269 | 1.92 ± 0.82a | ||

| p-value | 0.368 | 0.0109* | ||||

| LIFR: g.35862868C>T |

LIFR (intron 19) |

CC | 169 | 2.19 ± 1.03 | 104 | 1.71 ± 0.81b |

| CT | 262 | 2.21 ± 1.08 | 231 | 2.00 ± 0.83 a | ||

| TT | 106 | 2.25 ± 1.01 | 84 | 2.04 ± 0.78a | ||

| p-value | 0.91 | 0.0054** | ||||

| LIFR: g.35862947G>T |

LIFR (intron 19) |

GG | 166 | 2.18 ± 1.03 | 90 | 1.74 ± 0.84b |

| GT | 262 | 2.21 ± 1.08 | 233 | 1.96 ± 0.81ab | ||

| TT | 109 | 2.23 ± 1.01 | 97 | 2.05 ± 0.82a | ||

| p-value | 0.915 | 0.0309* | ||||

| NGF: g.91795933T>C |

NGF (intron 2) |

CC | 115 | 2.32 ± 1.06 | 73 | 1.73 ± 0.79b |

| CT | 278 | 2.13 ± 1.05 | 194 | 1.94 ± 0.85ab | ||

| TT | 144 | 2.28 ±1.02 | 153 | 2.02 ± 0.79a | ||

| p-value | 0.157 | 0.0418* | ||||

Note: N and S.D. in table headers denote the sample size and standard deviation of litter size. a, b within the same column with different superscripts means p < 0.05. *p indicates the significant association at the significance level α = 0.05; **p indicates the significant association at the significance level α = 0.01.

Nine significant SNPs were mapped to sheepQTL database (https://www.animalgenome.org/cgi-bin/QTLdb/OA/index) to better understand the potential role of these SNPs. Nine SNPs were mapped to 13 litter size related quantitative trait loci (QTLs) (Table 4). The nearest distance between SNPs and QTLs is 1.8 Mb (between KIT: g.70199073A>G and QTL 13975).

Table 4.

Litter size related quantitative trait loci (QTLs) annotation of nine significant single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with litter size in Hu sheep or Small-tailed Han sheep.

| SNP ID | QTL ID | QTL Region (Chr:Mb) | Distance (Mb) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KIT: g.70199073A>G | 13975 | Chr6:68.3-68.4 | 1.80 | [35] |

| 130449 | Chr6: 42.6-42.6 | 27.60 | [36] | |

| 154661 | Chr6: 29.4-29.4 | 40.80 | [21] | |

| 154662 | Chr6:29.4-29.4 | 40.80 | [21] | |

| KITLG: g.124520653G>C | 14242 | Chr3:75.2-75.3 | 49.22 | [37] |

| ADAMTS1: g.127753565T>C | - | - | - | - |

| ADAMTS1: g.127754640G>T | - | - | - | - |

| NCOA1: g.31928165C>T | 14242 | Chr3:75.2-75.3 | 43.27 | [37] |

| NCOA1: g.32140565G>A | 14242 | Chr3:75.2-75.3 | 43.27 | [37] |

| LIFR: g.35862868C>T | 154682 | Chr16:31.8-31.8 | 4.06 | [21] |

| 154683 | Chr16:31.8-31.8 | 4.06 | [21] | |

| 154684 | Chr16:31.9-31.9 | 3.96 | [21] | |

| LIFR: g.35862947G>T | 154682 | Chr16:31.8-31.8 | 4.06 | [21] |

| 154683 | Chr16:31.8-31.8 | 4.06 | [21] | |

| 154684 | Chr16:31.9-31.9 | 3.96 | [21] | |

| NGF: g.91795933T>C | - | - | - | - |

Note: “-” denotes information is not available.

3.4. The Haplotype Analysis

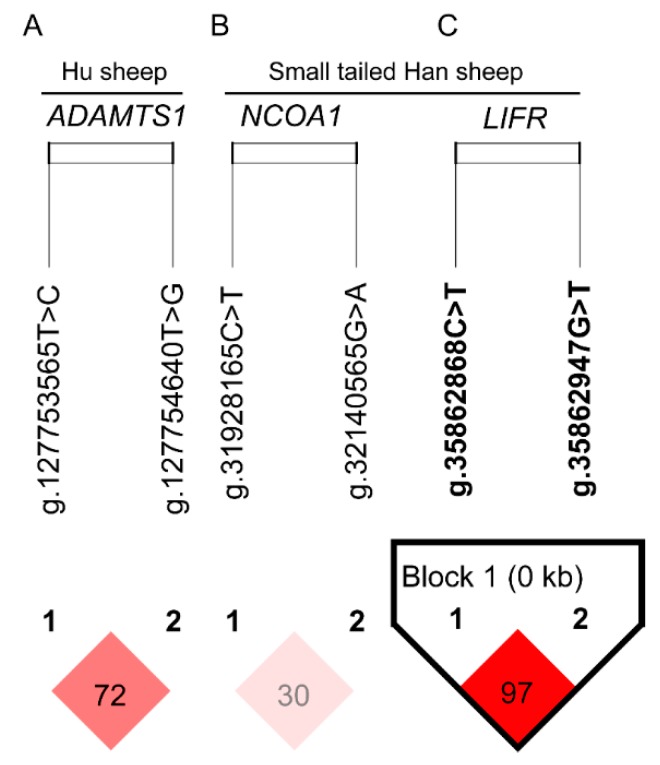

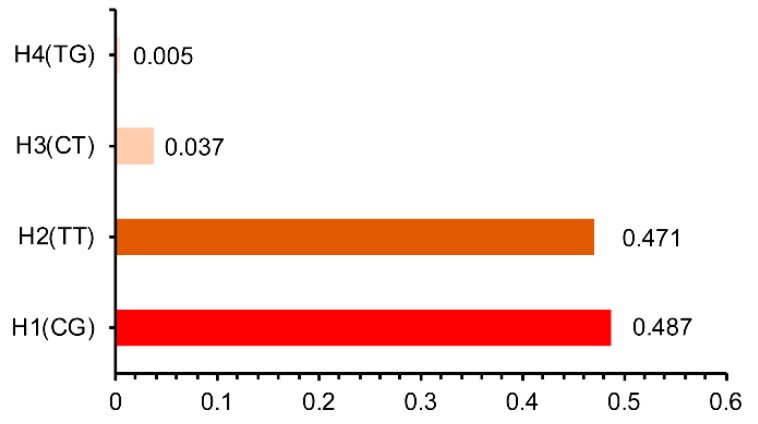

The D′ (r2) value is a factional indicator of LD and was calculated in this study. The D′ (r2) were 0.72 (0.34) and 0.30 (0.04) indicated that two SNPs (ADAMTS1: g.127753565T>C and ADAMTS1: g.127754640T>G) in Hu sheep (Figure 4A) and two SNPs (NCOA1: g.31928165C>T and NCOA1: g.32140565G>A) in Small-tailed Han sheep (Figure 4B) were not closely linked. While two SNPs (LIFR: g.35862868C>T and LIFR: g.35862947G>T) were closely linked (D′ and r2 were 0.97 and 0.84, Figure 4C). One haplotype block was identified in Small-tailed Han sheep (Figure 4C), where four different haplotypes were H1 (CG), H2 (TT), H3 (CT) and H4 (TG) (Figure 5). The highest haplotype frequency was H1, which accounted for 48.7% of all haplotypes. H2 was the next largest proportion, at 47.1% followed closely by H3 (3.7%) and H4 (0.5%) (Figure 4). Since haplotypes with low frequencies were meaningless in statistical analysis, H4 was excluded from subsequent analysis. The association analysis showed that haplotype combinations were significantly associated with litter size in Small-tailed Han sheep (Table 5). Individuals with H2H3 (CTTT), H2H2 (TTTT), H1H2 (CTGT) had greater litter size than individuals with H1H1 (CCGG).

Figure 4.

Linkage disequilibrium pattern for the significant single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in ADAMTS1 (A), NCOA1 (B), and LIFR gene (C). Scale of red color indicating the extend linkage disequilibrium (D′ value).

Figure 5.

Frequency of haplotypes inferred form two loci (LIFR: g.35862868C>T and LIFR: g.35862947G>T) in Small-tailed Han sheep.

Table 5.

Association between haplotype combinations and litter size in Small-tailed Han sheep.

| Haplotype Combination (n) | Litter Size (Mean ± S.D.) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| H1H1 (87) | 1.70 ± 0.82b | 0.0284* |

| H1H2 (214) | 1.97 ± 0.81a | |

| H1H3 (17) | 1.76 ± 0.75ab | |

| H2H2 (83) | 2.02 ± 0.78a | |

| H2H3 (14) | 2.21 ± 1.05a |

Note: S.D. in table headers denotes the standard deviation of litter size; H1denotes CG; H2 denotes TT; H3 denotes CT; a, b within the same column with different superscripts means p < 0.05; *p indicates the significant association at the significance level α = 0.05.

4. Discussion

Our hypothesis for this study was that the potential SNPs in these ten candidate genes may be linked with litter size in Hu sheep and Small-tailed Han sheep. If SNPs from the candidate genes were found significantly associated with litter size in a sheep breed, they could be served as molecular indicators for MAS. MAS based on prioritized molecular indicators could enhance the efficacy of sheep selection with improved litter size traits.

Nine SNPs in Hu sheep and eight SNPs in Small-tailed Han sheep with low polymorphic status (PIC < 0.25) were observed, and the heterozygosity of these loci were also notably low, which might be a result of artificial selection [38]. The majority of sites had a moderate (0.25 ≤ PIC < 0.5) or high polymorphic status (PIC ≥ 0.5), suggesting that these SNPs could provide more effective genetic information. One SNP in Hu sheep and nine SNPs in Small-tailed Han sheep significantly deviated from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, which was mainly due to nonrandom mating and/or artificial selection [38].

In the current study, nine SNPs in six genes were strongly linked with sheep litter size, confirming their genetic roles in regulating sheep litter size. Previous research found two SNPs in KIT [9] and ten SNPs in KITLG were significantly associated with goat litter size [10,11,12,13]. A mutation in ADAMTS1 was associated with pig litter size [19]. SNPs in NCOA1 were associated with litter size in Icelandic sheep [21]. Two SNPs in NGF were associated with litter size in goat [39]. In accordance with these studies, seven SNPs (KIT: g.70199073A>G, KITLG: g.124520653G>C, ADAMTS1: g.127753565T>C, ADAMTS1: g.127754640G>T; NCOA1: g.31928165C>T, NCOA1: g.32140565G>A, and NGF: g.91795933T>C) in five genes were significantly associated with litter size in Hu sheep or Small-tailed Han sheep. To the best of our knowledge, this report is the first to describe two SNPs (LIFR: g.35862868C>T, LIFR: g.35862947G>T) in LIFR that were significantly associated with sheep litter size. As a result, the finding that nine genetic markers were significantly associated with litter size in Hu sheep or Small-tailed Han sheep in the present study suggests that these SNPs were in LD with a nearby QTL for litter size or directly involved in the genetic control of the trait. To date, four QTLs on chromosome six, one QTL on chromosome three, three QTLs on chromosome 16 have been reported to contribute to the litter size (total lambs born) in sheep (Table 4). In this study, nine significant SNPs were not exactly located in any of these sheep litter size QTLs, the relatively short distances between SNPs and QTLs (e.g., 1.8 Mb between KITLG: g.124520653G>C and QTL 13975) indicated that it is possible that these markers are in LD with sheep litter size QTLs.

Previous research focused mainly on missense mutations because these SNPs can change amino acids and then protein function directly. Many missense SNPs, such as Y409N in KIT [9], have been identified as litter size-related genetic markers in sheep [40] or other mammals [9]. In the current study, eight out of nine significant SNPs (KIT: g.70199073A>G; KITLG: g.124520653G>C, ADAMTS1: g.127754640G>T; NCOA1: g.31928165C>T; NCOA1: g.32140565G>A; LIFR: g.35862868C>T; LIFR: g.35862947G>T; and NGF: g.91795933T>C) are in the intronic region, and one SNP (ADAMTS1: g.127753565T>C) is a synonymous mutation (Ser→Ser), indicating that these SNPs are unlikely to affect litter size by changing the amino acid directly. Nevertheless, the effects of these mutations cannot be ignored because mutations in an intron can regulate gene expression [41] or splicing [42], and synonymous mutations can affect mRNA splicing [43], stability [44,45], protein translation, and folding [46]. Recent research has shown that a SNP (KITLG: c.1457A>C) in KITLG 3′-UTR can affect goat litter size by changing the microRNA binding site to regulate KITLG mRNA expression level [13]. This finding suggests that these mutations have potential functions in litter size, although the underlying genetic mechanism warrants further investigation.

It is necessary to analyze the combined effect of multiple loci on litter size, since the litter size is controlled by multiple genes and loci. In this research, associations between the combined haplotypes (in LIFR gene) and litter size of Small-tailed Han sheep were analyzed. The combined haplotypes of the two loci association analysis revealed that H2H3 (CTTT) combined haplotypes had larger litter sizes than other combined haplotypes and larger than those with either mutation alone in Small-tailed Han sheep. This result indicates that the LIFR: g.35862868C>T and LIFR: g.35862947G>T have an interaction effect on sheep litter size. A previous study showed that a combined genotype (TTAA) in KIT gene in three goat breeds showed a larger litter size than those carrying single mutations, which supported the interactive effect of multiple markers within a gene on the litter size [9]. Theoretically, the most positive combined haplotypes should be H2H2 (TTTT) based on the association analysis between single locus and litter size. However, the litter size between H2H2 and H2H3 was not significant, which suggests that both CTTT and TTTT were advantageous combinations affecting the sheep litter size.

We observed that parity had an important effect on sheep litter sizes because it was reported that the correlation between litter size and first to third parities was a significant positive correlation [40]. However, in the current study, only first parity data were collected. Thus, the model of the association analysis did not consider parities for the ewes, which would be essential for future studies.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we extensively and systematically investigated potential SNPs in ten genes (NGF, NTRK1, KIT, KITLG, LIF, LIFR, NCOA1, ADAMTS1, NPM1, and NOG) as candidate markers for improved litter size in sheep. Nine SNPs in six genes (KIT: g.70199073A>G, KITLG: g.124520653G>C, ADAMTS1: g.127753565T>C, ADAMTS1: g.127754640G>T, NCOA1: g.31928165C>T, NCOA1: g.32140565G>A, LIFR: g.35862868C>T, LIFR: g.35862947G>T, and NGF: g.91795933T>C) were significantly associated with litter size in Hu sheep or Small-tailed Han sheep. The combined haplotypes analysis of the two loci (LIFR: g.35862868C>T and LIFR: g.35862947G>T) revealed that H2H3 (CTTT) combined haplotypes had more litter size than other combined haplotypes and more than those with either mutation alone in Small-tailed Han sheep. These nine SNPs can be served as useful genetic markers for MAS in Small-tailed Han sheep and Hu sheep.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Ruidong Xiang, University of Melbourne for language editing.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/9/11/958/s1. Table S1: Primers and PCR condition applied for pooled-DNA sequencing for the ten candidate genes. Table S2: Information of 78 identified single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the ten genes. Table S3: Associated between 36 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with litter size in Hu sheep and Small-tailed Han sheep.

Author Contributions

These studies were designed by X.Y and F.L.; Z.Y. analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript; J.Z. performed all the molecular experiments; X.Y. contributed to revisions of the manuscript; F.L., W.L., and W.W. assisted in explaining the results and preparing samples.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Technology Research and Development Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China, grant number 2015BAD03B05, China Agriculture Research System, grant number CARS-38, and Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University, grant number IRT13019.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Haresign W. The physiological basis for variation in ovulation rate and litter size in sheep: A review. Livest. Prod. Sci. 1985;13:3–20. doi: 10.1016/0301-6226(85)90075-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutt K., McLaughlin E., Holland M., McLaughlin E. Kit ligand and c-Kit have diverse roles during mammalian oogenesis and folliculogenesis. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2006;12:61–69. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Driancourt M., Reynaud K., Cortvrindt R., Smitz J. Roles of KIT and KIT LIGAND in ovarian function. Rev. Reprod. 2000;5:143–152. doi: 10.1530/ror.0.0050143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knapczyk-Stwora K., Grzesiak M., Duda M., Koziorowski M., Slomczynska M. Effect of flutamide on folliculogenesis in the fetal porcine ovary—Regulation by Kit ligand/c-Kit and IGF1/IGF1R systems. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2013;142:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dissen G.A., Romero C., Hirshfield A.N., Ojeda S.R. Nerve Growth Factor Is Required for Early Follicular Development in the Mammalian Ovary. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2078–2086. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.5.8126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaves R., Alves A., Duarte A., Araújo V., Celestino J., Matos M., Lopes C., Campello C., Name K., Báo S., et al. Nerve Growth Factor Promotes the Survival of Goat Preantral Follicles Cultured in vitro. Cells Tissues Organs. 2010;192:272–282. doi: 10.1159/000317133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaves R.N., Alves A.M., Lima L.F., Matos H.M., Rodrigues A.P., Figueiredo J.R. Role of nerve growth factor (NGF) and its receptors in folliculogenesis. Zygote. 2013;21:187–197. doi: 10.1017/S0967199412000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayerhofer A., Dissen G.A., Parrott J.A., Hill D.F., Mayerhofer D., Garfield R.E., Costa M.E., Skinner M.K., Ojeda S.R. Involvement of nerve growth factor in the ovulatory cascade: Trka receptor activation inhibits gap junctional communication between thecal cells. Endocrinology. 1996;137:5662–5670. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.12.8940397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.An X.P., Hou J.X., Gao T.Y., Cao B.Y. Cloning and expression of caprine KIT gene and associations of polymorphisms with litter size. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2016;56:1579–1584. doi: 10.1071/AN13497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.An X.P., Hou J.X., Li G., Song Y.X., Wang J.G., Chen Q.J., Cui Y.H., Wang Y.F., Cao B.Y. Polymorphism identification in the goat KITLG gene and association analysis with litter size. Anim. Genet. 2012;43:104–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2011.02219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.An X.P., Hou J.X., Gao T.Y., Lei Y.N., Song Y.X., Wang J.G., Cao B.Y. Association analysis between variants in KITLG gene and litter size in goats. Gene. 2015;558:126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.An X.P., Hou J.X., Lei Y.N., Gao T.Y., Song Y.X., Wang J.G., Cao B.Y. Two mutations in the 5′-flanking region of the KITLG gene are associated with litter size of dairy goats. Anim. Genet. 2015;46:308–311. doi: 10.1111/age.12277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.An X., Song Y., Bu S., Ma H., Gao K., Hou J., Wang S., Lei Z., Cao B. Association of polymorphisms at the microRNA binding site of the caprine KITLG 3′-UTR with litter size. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:25691. doi: 10.1038/srep25691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willis E.L., Bridges P.J., Fortune J.E. Progesterone receptor and prostaglandins mediate luteinizing hormone-induced changes in messenger RNAs for ADAMTS proteases in theca cells of bovine periovulatory follicles. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2017;84:55–66. doi: 10.1002/mrd.22761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robker R. Ovulation: A multi-gene, multi-step process. Steroids. 2000;65:559–570. doi: 10.1016/S0039-128X(00)00114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown H.M., Dunning K.R., Robker R.L., Boerboom D., Pritchard M., Lane M., Russell D.L. ADAMTS1 cleavage of versican mediates essential structural remodeling of the ovarian follicle and cumulus-oocyte matrix during ovulation in mice. Biol. Reprod. 2010;83:549–557. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.084434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kadi N., Tahiri L., Maziane M., Mernissi F.Z., Harzy T. Proximal symphalangism and premature ovarian failure. Jt. Bone Spine. 2012;79:83–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kosaki K., Sato S., Hasegawa T., Matsuo N., Suzuki T., Ogata T. Premature ovarian failure in a female with proximal symphalangism and Noggin mutation. Fertil. Steril. 2004;81:1137–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yue K., Peng J., Zheng R., Li J.L., Chen J.F., Li F.E., Dai L.H., Ding S.H., Guo W.H., Xu N.Y., et al. Sequencing, Genomic Structure, Chromosomal Mapping and Association Study of the Porcine ADAMTS1 Gene with Litter Size. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2008;21:917–922. doi: 10.5713/ajas.2008.60724. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen X., Liu Z., Xu J. The cooperative function of nuclear receptor coactivator 1 (NCOA1) and NCOA3 in placental development and embryo survival. Mol. Endocrinol. 2010;24:1917–1934. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu S.S., Gao L., Xie X.L., Ren Y.L., Shen Z.Q., Wang F., Shen M., Eyorsdottir E., Hallsson J.H., Kiseleva T., et al. Genome-Wide Association Analyses Highlight the Potential for Different Genetic Mechanisms for Litter Size Among Sheep Breeds. Front. Genet. 2018;9:118. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Modric T., Kowalski A.A., Green M.L., Simmen R.C., Simmen F.A. Pregnancy-dependent expression of leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF), LIF receptor-beta and interleukin-6 (IL-6) messenger ribonucleic acids in the porcine female reproductive tract. Placenta. 2000;21:345–353. doi: 10.1053/plac.1999.0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yelich J.V., Pomp D., Geisert R.D. Ontogeny of elongation and gene expression in the early developing porcine conceptus. Biol. Reprod. 1997;57:1256–1265. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod57.5.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song H., Lim H., Das S.K., Paria B.C., Dey S.K. Dysregulation of EGF family of growth factors and COX-2 in the uterus during the preattachment and attachment reactions of the blastocyst with the luminal epithelium correlates with implantation failure in LIF-deficient mice. Mol. Endocrinol. 2000;14:1147–1161. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.8.0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savatier P., Lapillonne H., van Grunsven L.A., Rudkin B.B., Samarut J. Withdrawal of differentiation inhibitory activity/leukemia inhibitory factor up-regulates D-type cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors in mouse embryonic stem cells. Oncogene. 1996;12:309–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart C.L., Kaspar P., Brunet L.J., Bhatt H., Gadi I., Kontgen F., Abbondanzo S.J. Blastocyst implantation depends on maternal expression of leukaemia inhibitory factor. Nature. 1992;359:76–79. doi: 10.1038/359076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anegon I., Cuturi M.C., Godard A., Moreau M., Terqui M., Martinat-Botte F., Soulillou J.P. Presence of leukaemia inhibitory factor and interleukin 6 in porcine uterine secretions prior to conceptus attachment. Cytokine. 1994;6:493–499. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(94)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma X.H., Hu S.J., Ni H., Zhao Y.C., Tian Z., Liu J.L., Ren G., Liang X.H., Yu H., Wan P., et al. Serial analysis of gene expression in mouse uterus at the implantation site. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:9351–9360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511512200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geisert R., Yelich J. Regulation of conceptus development and attachment in pigs. J. Reprod. Fertil. Suppl. 1997;52:133–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook J., Russell D.W. The Condensed Protocols From Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H., Wang B., Liu D., Wang T., Li Q., Wang W., Li H. SNPscan as a high-performance screening tool for mutation hotspots of hearing loss-associated genes. Genomics. 2015;106:83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Granato I.S.C., Galli G., de Oliveira Couto E.G., e Souza M.B., Mendonça L.F., Fritsche-Neto R. snpReady: A tool to assist breeders in genomic analysis. Mol. Breed. 2018;38:102. doi: 10.1007/s11032-018-0844-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Mendiburu F., Simon R. Agricolae-Ten Years of an Open Source Statistical Tool for Experiments in Breeding, Agriculture and Biology. PeerJ. 2015;PrePrints 3:e1404v1. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barrett J.C., Fry B., Maller J., Daly M.J. Haploview: Analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chu M., Jia L., Zhang Y., Jin M., Chen H., Fang L., Di R., Cao G., Feng T., Tang Q., et al. Polymorphisms of coding region of BMPR-IB gene and their relationship with litter size in sheep. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011;38:4071–4076. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0526-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.El-Halawany N., Zhou X., Al-Tohamy A.F., El-Sayd Y.A., Shawky A.E., Michal J.J., Jiang Z. Genome-wide screening of candidate genes for improving fertility in Egyptian native Rahmani sheep. Anim. Genet. 2016;47:513. doi: 10.1111/age.12437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chu M.X., Guo X.H., Feng C.J., Li Y., Huang D.W., Feng T., Cao G.L., Fang L., Di R., Tang Q.Q., et al. Polymorphism of 5′ regulatory region of ovine FSHR gene and its association with litter size in Small Tail Han sheep. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012;39:3721–3725. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma X., Guan L., Xuan J., Wang H., Yuan Z., Wu M., Liu R., Zhu C., Wei C., Zhao F., et al. Effect of polymorphisms in the CAMKMT gene on growth traits in Ujumqin sheep. Anim. Genet. 2016;47:618–622. doi: 10.1111/age.12455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Naicy T., Venkatachalapathy R.T., Aravindakshan T.V., Radhika G., Raghavan K.C., Mini M., Shyama K. Nerve Growth Factor gene ovarian expression, polymorphism identification, and association with litter size in goats. Theriogenology. 2016;86:2172–2178. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2016.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang W., La Y., Zhou X., Zhang X., Li F., Liu B. The genetic polymorphisms of TGFbeta superfamily genes are associated with litter size in a Chinese indigenous sheep breed (Hu sheep) Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2018;189:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang K.C. Critical regulatory domains in intron 2 of a porcine sarcomeric myosin heavy chain gene. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2000;21:451–461. doi: 10.1023/A:1005625302409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anna A., Monika G. Splicing mutations in human genetic disorders: Examples, detection, and confirmation. J. Appl. Genet. 2018;59:253–268. doi: 10.1007/s13353-018-0444-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pagani F., Raponi M., Baralle F.E. Synonymous mutations in CFTR exon 12 affect splicing and are not neutral in evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:6368–6372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502288102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kimchi-Sarfaty C., Oh J.M., Kim I.W., Sauna Z.E., Calcagno A.M., Ambudkar S.V., Gottesman M.M. A “silent” polymorphism in the MDR1 gene changes substrate specificity. Science. 2007;315:525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.1135308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fung K.L., Pan J., Ohnuma S., Lund P.E., Pixley J.N., Kimchi-Sarfaty C., Ambudkar S.V., Gottesman M.M. MDR1 synonymous polymorphisms alter transporter specificity and protein stability in a stable epithelial monolayer. Cancer Res. 2014;74:598–608. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sauna Z.E., Kimchi-Sarfaty C. Understanding the contribution of synonymous mutations to human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:683–691. doi: 10.1038/nrg3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.