Abstract

The ANKS1B gene was a top finding in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of antipsychotic drug response. Subsequent GWAS findings for ANKS1B include cognitive ability, educational attainment, body mass index, response to corticosteroids and drug dependence. We review current human association evidence for ANKS1B, in addition to functional studies that include two published mouse knockouts. The several GWAS findings in humans indicate that phenotypically relevant variation is segregating at the ANKS1B locus. ANKS1B shows strong plausibility for involvement in CNS drug response because it encodes a postsynaptic effector protein that mediates long-term changes to neuronal biology. Forthcoming data from large biobanks should further delineate the role of ANKS1B in CNS drug response.

Keywords: : antipsychotics, BMI, cognition, corticosteroids, drugs of abuse, glutamatergic neurotransmission, NMDA, postsynaptic density, serotonin, synapse to nucleus communication, synaptic plasticity

The ankyrin repeat and sterile alpha motif domain containing 1B (ANKS1B) gene encodes an activity dependent postsynaptic effector protein that is highly expressed in the brain [1]. Its encoded protein is often referred to as AIDA-1, while early studies also used the identifiers EB-1, ANKS2 and cajalin-2. The ANKS1B locus emerged as a top finding in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of antipsychotic drug (AP) response [2,3]. Since then, new findings suggest that ANKS1B could mediate response to other drugs, including clinical therapeutics and drugs of abuse, and may harbor variants of relevance for several phenotypes. In this review, we aim to assemble current information in the public domain on this promising gene in the context of CNS drug response. We achieved this by searching PubMed, PubMed Central and BioRxiv for articles in English containing the terms ‘ANKS1B’ and ‘AIDA-1’ (not case sensitive). We review current phenotypic associations with ANKS1B reported for humans and model organisms and discuss these in the context of the biological function of ANKS1B protein in the CNS. In particular, we aim to show that ANKS1B protein’s function as an intermediary between neuronal stimulation and longer-term changes to neuronal biology render it an important target for further study in relation to behavioral and CNS drug response phenotypes.

Biology of ANKS1B

ANKS1B is widely expressed in the brain [1]. In fact, its expression levels in brain are so high relative to its expression in other tissues that it is estimated to have the second most brain-specific expression pattern of all human genes [4]. ANKS1B takes its name from the several distinct, functional domains in the encoded protein. Figure 1 shows the domain structure of the full length protein isoform, with ankyrin (ANK) repeats, two sterile alpha motif (SAM) domains and a phosphotyrosine binding domain. As we now explain, each of these domains plays a distinct role in the complex function of ANKS1B protein.

Figure 1. . Linear protein domain structure of the full length ANKS1B protein.

The ANKS1B acronym comes from ‘ANKyrin repeat and Sterile alpha motif domain containing 1B’. The Ankyrin repeats (ANK, green boxes) link membrane proteins to the underlying cytoskeleton; the second SAM (pink triangles) domain contains a nuclear import signal; the PTB (pink rectangle) domain is involved in tyrosine kinase signaling. Light pink areas on the main axis represent regions of low complexity. ANKS1B is now known to be a protein of the postsynaptic density that translocates to the cell nucleus to regulate neuronal biology.

Domain structure adapted from the SMART database (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) [5].

ANK: Ankyrin; PTB: Phosphotyrosine binding; SAM: Sterile alpha motif.

Ankyrin repeat-containing proteins serve as adaptor or scaffold proteins that link membrane proteins to the underlying cytoskeleton [6]. Specifically, ANKS1B acts as a scaffold protein at the postsynaptic density (PSD), the protein-dense region located at postsynaptic membranes of excitatory glutamatergic synapses [7]. ANKS1B has been found in protein complexes with PSD-95 protein, one of the most prominent protein components of the PSD, with an estimated ratio of one ANKS1B protein to every two PSD-95 proteins [8]. As expected for a PSD protein, ANKS1B is also found in complexes containing several classes of glutamatergic receptor [9].

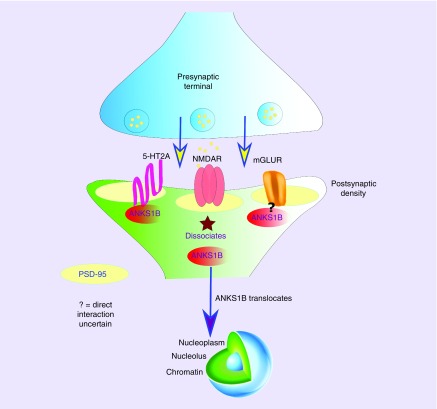

The presence of a phosphotyrosine binding domain indicates an involvement in signal transduction and this role for ANKS1B was confirmed in early studies [10]. In 2007, Jordan et al. [11] showed that stimulation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamatergic receptor complex at the PSD leads to translocation of ANKS1B protein to the nucleus where it regulates neuronal protein expression (Figure 2). Helix 5 of the second SAM domain in ANKS1B contains the nuclear import signal [12]. Subsequent studies showed that ANKS1B concentrates at the PSD core under basal conditions and its movement under excitatory conditions is mediated by CaMKII [13,14]. This CaMKII-mediated redistribution is similar to the movement of SynGAP under the same conditions [15,16]. The movement of these two abundant PSD proteins upon stimulation was thought to be significant in molecular reorganization of the synapse [15]. In 2015, Tindi et al. showed specifically that lack of ANKS1B leads to impairment of both NMDA-dependent long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD), confirming its role in synaptic plasticity.

Figure 2. . Diagram showing ANKS1B protein translocation from the postsynaptic density to the nucleus.

ANKS1B protein has been found in complexes with several PSD components, including PSD-95 and glutamate receptors of both ionotropic (NMDA) and metabotropic (mGluR) types. ANKS1B protein has also been shown to be a direct interacting partner of the serotonin 2A (5HT2A) receptor, which is a major target for second-generation antipsychotic drugs. The figure shows how, upon stimulation of NMDA receptors, ANKS1B dissociates from the PSD and migrates to the cell nucleus where it affects neuronal regulation, including protein expression. To date, it remains to be determined if 5HT2A or metabotropic glutamate receptor stimulation results in the same outcome.

Taken together, these molecular studies of ANKS1B and its functional interactions show that it operates as an intermediary between neuronal activity, specifically glutamatergic neurotransmission, and downstream changes to neuronal biology [17]. This suggests that ANKS1B could impact behavior and disorders of the CNS. We now describe the existing associations with ANKS1B in humans, beginning with the earliest, which is AP response in schizophrenia.

ANKS1B & antipsychotic drug response

Schizophrenia & antipsychotic drugs

Schizophrenia (SCZ) is a common psychiatric disorder with a median lifetime prevalence of just under 1% [18]. It is characterized by positive symptoms (hallucinations, delusions), negative symptoms (blunted affect, social withdrawal) and alterations to cognition (deficits in memory, attention and executive function) [19]. APs have been the mainstay of SCZ treatment since their introduction in the 1950s [20]. Currently, eleven first generation (typical) APs and twelve second-generation (atypical) APs are approved by the US FDA for clinical use, with additional approvals for injectable formulations (e.g., Aristada®). First- and second-generation drugs are distinguished by their modes of action. Second-generation APs such as olanzapine produce extensive blockade of serotonin 2A (5HT2A) receptors and, to a lesser extent, dopamine D2 (DRD2) receptors. This contrasts with first-generation APs, such as haloperidol, which are mainly DRD2 receptor antagonists and have weak, if any, potency as 5HT2A receptor antagonists [21].

Despite the range of APs currently available, no single drug is effective in all patients [22]. Therefore, researchers began to seek out genetic predictors of AP response. To date, the vast majority of studies focused on candidate genes hypothesized to play a role in AP pharmacodynamics or pharmacokinetics [23]. Pharmacodynamic candidate gene studies focused on genes encoding AP targets, such as DRD2, but no variant at any pharmacodynamic candidate gene has yet emerged as a robust predictor of AP response. Only variants at the CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genes, which encode drug-metabolizing enzymes, are considered by regulatory bodies such as the FDA as valid AP genetic biomarkers.

Genome-wide association studies of antipsychotic response

The limited repertoire of robust AP biomarkers at candidate genes led to the adoption of GWAS to discover novel associations. GWAS has been phenomenally successful in identifying genes for many diseases and traits (see www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/). Previously, we carried out GWAS to study AP outcomes in the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE), one of the largest publicly funded clinical trials of antipsychotics in the treatment of SCZ. In CATIE, four second-generation APs (olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine and ziprasidone) were compared with a first-generation AP (perphenazine) [22]. We conducted two GWAS of AP efficacy, the first of which used reduction in SCZ symptoms as measured by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) to define a response, while the second used improvement in neurocognitive function. In both studies, ANKS1B was among the top findings. More specifically, in the first analysis, SNP rs7968606 at ANKS1B was associated with improvement in negative symptoms following treatment with olanzapine (p = 3.2 × 10-7) [3]. In the second analysis, SNP rs11110077 at ANKS1B was associated with improved working memory following treatment with quetiapine (p = 3.7 × 10-7) [2]. Although neither SNP passed the current consensus threshold for genome-wide significance (GWS, p < 5 × 10-8), ANKS1B was the only gene to emerge as a top finding in both analyses.

A recent GWAS of response to lurasidone, an atypical AP, was conducted by Li et al. [24] in 302 patients with schizophrenia. Although this study did not find any GWS associations, they focused on ANKS1B as a candidate gene. They found rs10860532 in ANKS1B to be associated with lurasidone response (p = 2.6 × 10-5). This is a different SNP from those reported in CATIE and cited above, but it is just 22.5 Kb from one of them, rs11110077, which was associated with improvement in working memory following quetiapine treatment [2].

A targeted pharmacogenetic study by Kang et al. [25] focused on SNP rs7968606, which was associated with negative symptom response to olanzapine in CATIE. Kang et al. analyzed rs7968606 in a Korean sample of 154 patients and reported a significant association (p < 0.05) between this SNP and response to amisulpride, an atypical AP. They found a significant association between the polymorphism and the general improvement score of the PANSS, but there was no significant association between the SNP and other domain scores of PANSS.

In the largest AP pharmacogenomics GWAS to date, the Chinese Antipsychotic Pharmacogenomics Consortium (CAPOC), the authors found five loci associated with AP response that passed the GWS threshold. Although ANKS1B was not among these GWS findings, the authors also studied several candidate genes, including ANKS1B, for association with AP response. The best association with ANKS1B was p = 3.0 × 10-4 with response to olanzapine, a drug with which it was originally associated in CATIE.

Some AP GWAS did not find any evidence for ANKS1B, even in the context of candidate gene testing, as far as can be ascertained. Li et al. [26] performed a GWAS of response to extended release paliperidone tablets or once monthly injectable formulations and did not detect any associations with ANKS1B SNPs. However, their threshold for reporting findings was p = 1.0 × 10-5 so it is possible that nominally significant SNPs at ANKS1B were observed that did not pass this threshold. Stevenson et al. [27] performed an analysis of glutamatergic candidate genes and an exploratory GWAS of risperidone response in 86 first episode psychosis patients. However, ANKS1B was not among the candidate genes selected, possibly because it is not widely recognized as a mediator of glutamatergic signaling, nor was it associated p < 0.001 (threshold reported) in the exploratory GWAS.

Overall, the findings for ANKS1B and AP response are promising, but not definitive. An ongoing issue in psychiatric pharmacogenomics studies is statistical power. Clinical trials are expensive, so sample sizes tend to be too small to reliably detect genes of small effect. Several other factors preclude clear replications of the original CATIE findings in that many of the drugs investigated in subsequent studies were not studied in CATIE, for example, lurasidone and amisulpride. Furthermore, while the instrument used to assess symptoms, and therefore response, was similar across many of these studies (i.e., the PANSS), different thresholds and timelines are often used. For example, the CAPOC study used a 6-week period whereas the CATIE analyses took account of the entire 18 month duration of the trial. Ethnicities used in the trials were different as well. This can lead to discrepancies in replication if the underlying causal mutation is relatively recent and therefore only seen at high frequencies in specific ancestral groups. Nevertheless, if we consider the original CATIE analyses as ‘hypothesis-generating’, then subsequent studies that tested ANKS1B as a candidate gene do suggest that it could be a mediator of second-generation AP response. In the context of further interpreting the influence of ANKS1B genetic variation on human traits, we now consider other association findings for ANKS1B.

Genomic findings for ANKS1B: the broad perspective

Table 1 shows 18 current GWAS hits for ANKS1B in the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) – European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) GWAS catalog (www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas), in addition to four recent GWS findings that have not yet been entered into the GWAS catalog. Most of these associations can be classified into four partially overlapping categories, viz: drug response; CNS and behavioral phenotypes; weight-related phenotypes; and circulating cytokines and growth factors. We now discuss the GWAS catalog entries for ANKS1B, in addition to other relevant associations, in these four areas. Association p-values by genomic position for the ANKS1B locus are plotted in Figure 3 to visualize proximity of associated SNPs.

Table 1. . Genome-wide association studies findings of ANKS1B associations.

| SNP | Chr12 position (GRCh38) | Phenotype | p-value | Study (year) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS catalog | |||||

| rs142161979 | 99392036 | Peak cortisol response to low dose short synacthen test in corticosteroid treated asthma | 9 × 10-9 | Hawcutt et al. (2018) | [28] |

| rs7960581 | 98825958 | ACE inhibitor intolerance | 3 × 10-7 | Mahmoudpour et al. (2017) | [29] |

| rs660884 | 99160030 | Yeast infection | 2 × 10-6 | Tian et al. (2017) | [30] |

| rs11110094 | 9894329 | Stromal cell-derived factor 1 α levels | 2 × 10-7 | Ahola-Olli et al. (2016) | [31] |

| rs11110094 | 99894329 | IL-17 levels | 8 × 10-7 | Ahola-Olli et al. (2016) | [31] |

| rs11110094 | 99894329 | IL-6 levels | 6 × 10-6 | Ahola-Olli et al. (2016) | [31] |

| rs146024394 | 99333356 | Stem cell growth factor β levels | 5 × 10-7 | Ahola-Olli et al. (2016) | [31] |

| rs150896237 | 99901313 | Stem cell growth factor β levels | 3 × 10-6 | Ahola-Olli et al. (2016) | [31] |

| rs10745841 | 99099957 | SCZ | 1 × 10-6 | Goes et al. (2015) | [32] |

| rs201412 | 98896535 | Electrodermal activity | 1 × 10-7 | Vaidyanathan et al. (2014) | [33] |

| rs1961649 | 99510762 | Metabolite levels (HVA/5 –HIAA ratio) | 3 × 10-6 | Luykx et al. (2013) | [34] |

| rs108603992 | 99104409 | Autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder and schizophrenia (combined) | 2 × 10-6 | Smoller et al. (2013) | [35] |

| rs2036225 | 98796594 | ALS (Age of onset) | 8 × 10-6 | Ahmeti et al. (2012) | [36] |

| rs483610 | 98940751 | Obesity-related traits | 7 × 10-6 | Comuzzie et al. (2012) | [37] |

| rs2373011 | 99567571 | BMI | 9 × 10-6 | Croteau-Chonka et al. (2010) | [38] |

| rs2373011 | 99567571 | Waist circumference | 2 × 10-6 | Croteau-Chonka et al. (2010) | [38] |

| rs11110077 | 99872335 | Response to antipsychotic treatment (working memory) | 3.7 × 10-7 | McClay et al. (2010) | [3] |

| rs7968606 | 99423064 | Response to antipsychotic treatment (negative SCZ symptoms) | 3.2 × 10-7 | McClay et al. (2009) | [2] |

| New genome-wide significant findings | |||||

| Gene-based | 98,735,422-99,984,237 | General cognitive ability† | 1.1 × 10-8 | Davies et al. (2018) | [39]† |

| rs2131167 | 99,239,411 | Educational attainment | 1.5 × 10-8 | Lee et al. (2018) | [40] |

| rs2246664 | 99,217.881 | BMI meta-analysis | 1.8 × 10-14 | Yengo et al. (2018) | [41] |

| rs2133896 | 99,455,372 | Substance dependence | 4.1 × 10−8 | Sun et al. (2018) | [42] |

The table shows SNP markers in the ANKS1B gene region with GWAS entries in the NHGRI-EBI GWAS catalog or newer genome-wide significant findings that have yet to be entered in the catalog. SNPs are shown with their genomic positions on chromosome 12 in the latest human genome build (GRCh38), in addition to the reported p-value of association and the original citation.

not plotted on Figure 3 because association involves several markers spanning the gene.

5-HIAA: 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid; ACE: Angiotensin converting enzyme; ALS: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; BMI: Body mass index; GWAS: Genome-wide association study; HVA: Homovanillic acid; SCZ: Schizophrenia.

Figure 3. . Graph of ANKS1B genome-wide association studies findings, plotted by position in the gene (x-axis).

The approximate exon–intron structure is also shown below the x-axis. Each GWAS finding is labeled with the associated phenotype (see Table 1 for more details). For each genome-wide association study finding, the -log10 (p-value) of the top SNP is plotted on the y-axis, with more significant findings exhibiting larger y-axis values.

Points labeled ‘Cytokine/GF’ refer to associations with circulating cytokines and growth factors as reported by [31].

ACE: Angiotensin-converting enzyme; ALS: Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; AP: Antipsychotic; SCZ: Schizophrenia.

Drug response

In addition to the two CATIE GWAS studies of AP response mentioned above, ANKS1B has a GWAS catalog entry for association with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)-inhibitor intolerance. Specifically, Mahmoudpour et al. [29] found SNP rs796051 at ANKS1B to be associated with ACE inhibitor intolerance at p = 3 × 10-7 in a sample of 972 patients. It is difficult to speculate, however, on a possible mechanism through which ANKS1B could mediate ACE inhibitor intolerance in light of its function as a PSD effector protein. The GWAS catalog also shows an entry for response to methotrexate in juvenile idiopathic arthritis [43]. However, the top SNP reported in this study is actually located in the neighboring ANO4 gene on chromosome 12 and hence is not included in Table 1.

More robust evidence for an ANKS1B drug response association was provided by Hawcutt et al. [28], who found several SNPs at ANKS1B to be associated with peak cortisol response to a low dose Synacthen test in young patients with corticosteroid-treated asthma (best p = 9 × 10-9). This test evaluates the ability of the adrenal cortex to produce cortisol after stimulation by synthetic adrenocorticotrophic hormone (tetracosactide, with the trade name Synacthen). The test is most typically used to assess adrenal suppression, which is an adverse side effect of corticosteroid therapy. Therefore, this interesting GWS finding indicates that ANKS1B may play a role in mediating corticosteroid response and/or side effects.

A very recent GWAS by Sun et al. [42] reports a GWS association between SNP rs2133896 at ANKS1B and substance dependence (p = 4.1 × 10-8), looking at a large combined cohort of heroin- (n = 1026), methamphetamine- (n = 1749) and alcohol- (n = 521) dependent subjects and 2859 controls. Combining both their discovery and replication samples, the ANKS1B association was validated in the heroin (p = 2.4 × 10-5) and methamphetamine (p = 2.8 × 10-7) single drug dependence groups. Furthermore, the authors confirmed the statistical association in humans in a rodent drug self-administration test by showing that overexpression of the rat ortholog Anks1b was protective against high levels of methamphetamine and heroin self-administration. Interestingly, rs2133896 associated with substance dependence in this study is just 32 kb from rs7968606, which was associated with improvement in negative symptoms following treatment with olanzapine in CATIE and in the candidate gene study of amisulpride by Kang et al. [25]. Although the development of drug dependence is clearly distinct from AP response, both outcomes share the core feature of CNS adaptation to a pharmacological exposure. Due to the proximity of the associations, it is tempting to speculate that they are tagging the same underlying causative variant(s).

In addition to the findings in Table 1, ANKS1B was reported among the top ranked findings in other drug response GWAS, although the levels of significance did not meet even the liberal GWAS Catalog reporting minimum (p = 1.0 × 10-6). For example, ANKS1B was the 5th best finding (p = 2.1 × 10-5) in a GWAS of citalopram response in the STAR*D trial, a large clinical trial of antidepressants [44]. Furthermore, SNPs at ANKS1B ranked as the 5th (p = 1.3 × 10-3) and 6th (p = 1.3 × 10-3) best findings in a GWAS of treatment response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) plus antipsychotic treatment in 96 Japanese obsessive compulsive disorder subjects [45].

CNS & behavioral phenotypes

ANKS1B has a GWAS Catalog entry for association with risk for SCZ (p = 1 × 10-6) in a study by Goes et al. [32]. However, the study reported a very large number of associations (>600) despite being conducted in a relatively small sample. Furthermore, the patient sample was from a population isolate, the Ashkenazi Jews, so it may not generalize to the wider population. In a much larger GWAS of approximately thirty thousand patients, Smoller et al. [35] reported a weak (p = 1 × 10-6) association between ANKS1B and cross-disorder liability for five major psychiatric disorders, in other words, SCZ, major depressive disorder (MDD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), bipolar disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Although these two studies are suggestive of an effect, very large and well-powered GWAS of major psychiatric disorders in tens of thousands of subjects have now been published by the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC). ANKS1B was not among the 108 significant associations in the PGC GWAS of SCZ published in 2014 [46], nor the 44 associations with MDD published in 2018 [47]. The lack of association in these studies argues against common variants at ANKS1B contributing to SCZ or MDD. Equivalent scale analyses of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder are forthcoming. On the other hand, rare variant analysis using DNA sequencing approaches has implicated ANKS1B in SCZ and ASD as we discuss in the Rare Variants section below.

Despite limited evidence for common variants at ANKS1B being risk factors for psychiatric disorders, recent large scale GWAS have found this gene to be associated with cognitive phenotypes in the general population. ANKS1B was a gene-based GWS finding with general cognitive ability in the CHARGE-COGENT and UK Biobank study (p = 1.1 × 10-8) [39]. SNP rs2131167 at ANKS1B was also a GWS finding with educational attainment in a study of 1.1 million individuals [40]. In both cases, the effect sizes were small but these studies indicate the presence of common variants at ANKS1B of relevance to cognition. These findings with ANKS1B and cognition in the general population support, to some extent, the CATIE association with ANKS1B and improved neurocognitive outcomes (working memory) following treatment with quetiapine, mentioned above.

The remaining GWAS catalog entries in the neuropsychiatric area are with endophenotypes, which are typically defined as simpler, more stable biological correlates of a complex trait or disease. One suggestive endophenotype finding with ANKS1B is electrodermal activity, or more specifically skin conductance (p = 1 × 10-7) [33]. This measure is correlated with autonomic nervous system arousal and is considered to be an endophenotype for several behavioral traits such as psychopathy and anxiety. Furthermore, ANKS1B has a GWAS catalog entry for metabolite levels in cerebrospinal fluid. Specifically, the finding was with the homovanillic acid (HVA) to 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid (5-HIAA) ratio (p = 3 × 10-6) [34]. Homovanillic acid is the primary metabolite of dopamine in the cerebrospinal fluid, while 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid is the primary metabolite of serotonin. As the receptors of these neurotransmitters are among the primary targets for APs, this is another finding consistent with the presence of genetic variation at ANKS1B of relevance to CNS function.

Circulating cytokines & growth factors

All the GWAS catalog associations reported between ANKS1B and levels of circulating cytokines and growth factors arise from a single study by Ahola-Olli et al. [31] of 8293 Finnish subjects. ANKS1B showed suggestive evidence for association with several factors, including levels of IL-6 and -17, stromal derived factor 1 α levels and stem cell growth factor β levels.

Weight & BMI phenotypes

ANKS1B has GWAS catalog entries for obesity-related traits in children [37], in addition to BMI and waist circumference in women [38], although both of these associations are not genome-wide significant. However, a more recent BMI GWAS by Hoffman et al. [48] identified rs2372716 at ANKS1B to be associated with BMI at p = 3 × 10-15. In a GWAS meta-analysis of BMI conducted by Yengo et al. [41], ANKS1B shows robust evidence for GWS with 138 SNPs at the locus showing association p < 5.0 × 10-8. This study comprised over 700 K subjects and was conducted in the GIANT (Genetic Investigation of Anthropometric Traits) and UK Biobank samples, which also served as replication samples for the Hoffman et al. study. These associations in human GWAS are further supported by a fine mapping study in mice that identified Anks1b as a quantitative trait locus (QTL) for bodyweight [49].

Rare variants

As outlined above, ANKS1B is not associated with psychiatric disease risk in the large-scale GWAS of common SNPs conducted by the PGC. However, next-generation sequencing of rare variants has produced some interesting findings for ANKS1B. Considering SCZ first, ANKS1B is one component of a PSD-95 gene set enriched for rare variants considered to have large effects on SCZ (see Extended Data Table 2 in reference [50]). Furthermore, ANKS1B was found to harbor de novo variation not shared between twins discordant for SCZ [51]. Li et al. [52] performed whole genome sequencing of postmortem brain tissue from ASD cases and identified significant nonsynonymous variants at ANKS1B. These findings were validated by exome sequencing of an independent cohort of 505 ASD cases and 491 controls. Finally, using high resolution microarray analysis, ANKS1B rare copy number variations were identified in infants with obsessive compulsive disorder [53]. Taken together, these findings suggest that mutations at ANKS1B are not well-tolerated and may lead to increased risk for psychiatric disorders.

Epigenetic & functional studies of ANKS1B

Epigenetics

In addition to being a top finding in GWAS, ANKS1B has emerged as a top finding in several exploratory epigenetic studies of CNS-related phenotypes. Epigenetics is the study of reversible modifications to chromatin that regulate gene expression, with DNA methylation of cytosine residues and post-translational modifications to histone lysine residues being the most studied. As with the findings with genetic variants, most epigenetic associations with ANKS1B have been found with neuropsychiatric or other CNS outcomes. Most notably, Han et al. [54] identified CpG cg24305861 at ANKS1B to be differentially methylated (p = 8.6 × 10-7) in the prefrontal cortex of patients with SCZ. However, the authors did not provide information on any controls for drug treatment in the analysis. Therefore, it is unclear if this DNA methylation difference increases risk for the disorder or could be the result of AP treatment. Previous studies have shown that AP treatment can influence epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation in the brain, while other studies have suggested histone acetylation may be involved in AP response [55,56]. Disentangling the epigenetic direction of effect in AP response is an important challenge in the field.

Papale et al. [57] identified Anks1b as a differentially hydroxymethylated region in mice exposed to early life stress with later anxiety behaviors. The change in hydroxymethylation also correlated with expression, suggesting the differentially hydroxymethylated region may have a functional impact. The same group found hippocampal hydroxymethylation changes at Anks1b in female mice in response to acute stress [58]. Anks1b was also a GWS hypomethylated finding in the nucleus accumbens of offspring of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-treated rats [59], suggesting the THC-induced epigenetic effect was laid down during gestation. Finally, Sewal et al. [60] found Anks1b to be the 4th most significant differentially expressed transcript (log ratio 6.44) in hippocampal CA1 neurons following a learning experience (water maze) in the presence of a histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACi). Histone acetylation serves as an important molecular mediator of environmental influences on neuronal gene and protein expression. The study by Sewal et al. implicates Anks1b in an epigenetically mediated gene expression cascade in learning.

Animal studies of Anks1b

The effects of deficiency or depletion of Anks1b have begun to be evaluated in both constitutive (whole body) [61] and conditional, tissue-specific knockout mice [62]. The Cre-lox system was used on a C57BL/6 background to ablate exon 17 in the germ line. Exon 17 encodes the second SAM domain and the nuclear import signal and its ablation leads to zero functional protein [61]. These constitutive Anks1b knockout mice showed significantly fewer homozygous knockouts at weaning than expected, indicating that zero functional Anks1b is partially lethal. The surviving knockouts showed greater levels of general locomotor activity and stereotypy counts than their wild-type counterparts. These mice also displayed significant deficits in prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle response, an operational measure of sensorimotor gating. Sensorimotor gating is defined as the neurocognitive inhibitory process of filtering out excessive or irrelevant stimuli and is significantly disrupted in SCZ [63,64]. Prepulse inhibition can be disrupted pharmacologically by NMDA antagonists as well as by dopamine agonists (for review, see [65]). In response to the NMDA antagonist ketamine, Anks1b knockout mice display a heightened sensitivity to the drug’s locomotor-stimulating effects insofar as a potentiated locomotor effect is observed at a low dose [61].

In addition to behavior, the role of Anks1b in regulating synaptic and NMDA receptor function using a forebrain-specific (CaMKII) knockout mouse model has begun to be characterized [62]. Electrophysiological and immunochemical data from hippocampal slices of these knockout mice suggests changes to NMDA receptor subunit composition, with a decrease in GluN2B-containing receptors and an increase in GluN2A-containing receptors being found in hippocampal PSDs. Importantly, these changes in NMDA subunit composition correspond with a reduced NMDA receptor-dependent LTP and LTD profile, two processes underlying learning and memory. The involvement of NMDA receptors in these processes has been widely studied (for review, see [66]). Moreover, changes in AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid)-type glutamate receptor subunit levels or AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission were not observed in these knockout mice, suggesting Anks1b selectively regulates NMDA receptors. An accumulation of GluN2B in the endoplasmic reticulum fractions of hippocampal tissue from knockout mice further supports a role for Anks1b in regulation of NMDA receptor subunit composition.

Taken together, these rodent models of Anks1b ablation display disrupted NMDA signaling that is reflected at the cellular and behavioral levels, including disruption to processes such as LTP and LTD that are fundamental to cognition. Therefore, these studies offer support for the human GWAS findings of ANKS1B with cognitive phenotypes.

ANKS1B/AIDA-1 & Alzheimer’s disease

An alternative name for ANKS1B protein is AIDA-1, which stands for amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain associated-1. Amyloid precursor protein is involved in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common type of dementia among older adults that leads to memory loss, cognitive disabilities and death. Deposition and aggregation of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide in the brain play a crucial role in AD [67] and Aβ peptide is released by the amyloid-β precursor protein (AβPP) via proteolytic cleavage [68]. Ghersi et al. [1] first showed the interaction between amyloid-β precursor protein and ANKS1B protein, while a more recent exploratory study by Scholz et al. [69] identified ANKS1B and seven other genes as candidates for late-onset AD in participants of the Vienna Transdanube Aging (VITA) study. Finally, Ianov et al. [70] found the expression of ANKS1B to be decreased in the medial prefrontal cortex in aging. With the clear pattern of association between ANKS1B and cognition, this finding suggests that further study of ANKS1B in the context of age-related cognitive decline is warranted.

Summary & discussion

We reviewed genome-wide significant (GWS) associations with ANKS1B in the areas of general cognitive ability, educational attainment, BMI, drug dependence and corticosteroid response. We also reviewed several suggestive associations with ANKS1B, predominantly in the areas of neuropsychiatric phenotypes and circulating cytokines and growth factors. Broadly, these studies indicate that there are common, phenotypically relevant variants at this gene segregating in the population. More specifically, the GWS findings in cognition and BMI in large, well-powered cohort studies reinforce earlier findings in smaller sample sizes that fell short of GWS. We also summarized evidence that rare, disruptive variants at ANKS1B are present in patients with psychiatric disorders such as SCZ and ASD, suggesting that ablation of this gene has significant effects on phenotype, which was substantiated in studies of knockout mice. Overall, functional and epigenetic studies of ANKS1B provide a sound mechanistic basis that can explain the associations with cognition in humans. Specifically, we refer to the role of ANKS1B protein as a downstream effector of NMDA receptor signaling and its involvement in synaptic plasticity, LTP and LTD. We now discuss the potential mechanisms by which ANKS1B could influence other phenotypes that we have discussed in this review.

Potential mechanisms of ANKS1B associations with neuropsychiatric phenotypes

In the absence of a clear functional effect of a variant on the coding sequence of a gene (e.g., nonsynonymous substitution, frameshift), we can consider if it affects expression levels. Variants affecting expression are known as expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) and large-scale consortia such as the Genotype Tissue Expression (GTEx) project have begun to systematically test for significant eQTLs genome-wide. According to GTEx (gtexportal.org), the strongest brain eQTLs for ANKS1B are for expression in the amygdala, some of which achieved GWS p-values. Other, weaker brain eQTLs (p = 10-4) were found for cerebellar expression, and none emerged for the cortex or hippocampal region. Perhaps surprisingly, given the brain-specific expression pattern of ANKS1B, the vast majority of GTEx eQTLs for ANKS1B were found in the thyroid. Although it is difficult to reconcile this finding with ANKS1B‘s cognitive associations, it is possibly congruent with its BMI associations because of the role of the thyroid in regulating metabolism, as discussed below (ANKS1B and antipsychotic-induced weight gain).

In contrast to GTEx, a separate study of postmortem human brain gene expression showed allelic expression imbalance (AEI) at ANKS1B, whereby it was in the top ten most AEI regions in Brodmann’s Area (BA) 46 and in the top 20 for BA22 [71]. BA46 roughly corresponds to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), occupying the middle third of the middle frontal gyrus and the rostral portion of the inferior frontal gyrus. BA22 occupies much of the superior temporal gyrus, which includes Wernicke’s area, and is involved in auditory processing, including language. Both the DFPLC and the superior temporal gyrus regions have been implicated in SCZ. These AEI findings suggest that ANKS1B alleles are differentially expressed in the brain, but the underlying mechanism (e.g., cis-acting variants, genomic imprinting, epigenetic silencing) is unknown. More focused research is needed to determine the nature and extent of allelic expression differences in these important brain regions, in order to reconcile this finding with the lack of GTEx eQTLs uncovered in human cortex.

Potential mechanisms of ANKS1B associations with drug response

The precise mechanisms through which ANKS1B may mediate drug effects are unclear at this point. Possibly the most pressing question is how drugs may affect ANKS1B function, such that pre-existing individual differences in ANKS1B expression or activity are manifested as differences in response following drug exposure. Several recent findings regarding the interacting partners of ANKS1B protein now allow us to speculate on possible mechanisms and suggest hypotheses that could be tested in future studies. We illustrate all ANKS1B direct protein–protein interactions reported in the public domain in Figure 4.

Figure 4. . Network of known ANKS1B direct protein interactions.

The network graph was generated from public data on direct protein–protein interactions only using InBioMap™ from Intomics (www.intomics.com).

Most relevant in the context of AP response is that ANKS1B protein is a direct interacting partner of the serotonin 2A receptor (5HT2A) [72], which is a primary target for second-generation AP drugs [21]. Second-generation APs include olanzapine, quetiapine, lurasidone and amisulpride that were the subject of ANKS1B pharmacogenetics associations outlined above (see Genome-wide association studies of antipsychotic response). The physical interaction between 5HT2A and ANKS1B implicates ANKS1B in serotonergic neurotransmission. Serotonin regulates both dopamine and glutamate neurotransmission in cortical and subcortical regions, with substantial implications for SCZ therapy [73]. PSD-95 is also a known binding partner of 5HT2A and PSD-95 knockout mice show altered second-generation AP drug response [74]. Further analysis of the interplay between 5HT2A, ANKS1B and the PSD in the context of AP response could be a fruitful avenue for further study, particularly since expression of other PSD scaffold proteins such as Homer1a are altered following AP administration [75].

Another ANKS1B protein interacting partner of relevance is ERBB4, which encodes a receptor tyrosine kinase that is activated by neuregulins. The neuregulin/ERBB4 pathway has been implicated in SCZ [76], AP response [77] and cognition in previous studies. Furthermore, and in direct parallel with ANKS1B, there are reported associations between ERBB4 and BMI/weight. For example, Locke et al. [78] found a GWS association between ERBB4 variants and BMI in a large GWAS. Since both ANKS1B and ERBB4 proteins physically interact and appear to be associated with similar phenotypes, it is likely that they operate in the same functional pathway. NMDA receptor signaling and ERBB4/neuregulin have been implicated in synaptic plasticity in SCZ [76], which is congruent with ANKS1B’s role in LTP/LTD [62]. Indeed, Chang et al. [79] used a gene network approach to integrate common and rare genetic risk factors in SCZ and found several over-represented networks, including ERBB signaling, neural development and synaptic plasticity. The NMDAR interactome was the top network overall and ANKS1B was highlighted as one of the top candidate genes in it (p = 1.3 × 10-6). Chang et al. [79] stated that “genes targeted by common SNPs are more likely to interact with genes harboring de novo mutations in the protein–protein interaction network, suggesting a mutual interplay of both common and rare variants in schizophrenia.” Further experimental characterization of the ANKS1B/ERBB4 interaction may be fruitful in the context of AP response, particularly in determining if ANKS1B facilitates neuregulin signaling.

In addition to AP drugs, ANKS1B was implicated in mediating corticosteroid response. This association with the endocrine signaling, rather than classical neurotransmission, puts us beyond the well-defined biology of ANKS1B protein function. Nevertheless, several of the interacting partners in Figure 4 may provide clues as to possible mechanisms. For example, the ERBB family receptors, which include EGFR (EGF receptor, also known as ERBB1), may once again play a role. There is a growing recognition of crosstalk between the ERBB receptors and steroid hormone systems, such that steroid hormones modulate ERBB signaling and vice versa [80]. The integrins (ITGB1, B3 and B7, Figure 4) also interact with steroid hormones. Integrins are transmembrane receptors that facilitate cell-extracellular matrix adhesion and activate several signal transduction pathways. They occur as heterodimers of α- and β-subunits. Expression of integrin β3 (encoded by ITGB3 – see Figure 4) dramatically increases (>sixfold) following exposure to the synthetic corticosteroid dexamethasone [81]. Therefore, the involvement of ANKS1B in corticosteroid response is certainly plausible and further study of the interplay between these factors in model systems may be a fruitful avenue of research.

The final category of drug for which we emphasized association evidence is drugs of abuse. Neurobiological theories of drug abuse and dependence tend to emphasize the hedonic impact of dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens to explain drug-seeking behavior [82]. We have not found any indication that ANKS1B interacts with dopaminergic neurotransmission but this remains to be formally tested. Nevertheless, response to drugs of abuse may be mediated by dopaminergic interactions at PSD, where ANKS1B is located, and there is a significant body of literature on the role of learning and synaptic plasticity in conditioning and reinforcement of drug-seeking behavior [82]. Indeed, chronic ethanol exposure causes synaptic clustering of ANKS1B protein in primary hippocampal neurons and this increase can be blocked by concurrent stimulation of NMDARs [83]. These results suggest a complex, NMDAR activity-dependent interaction with the drug. Sun et al. [42] showed that reduced Anks1b expression in the rat ventral tegmental area increased addiction vulnerability in heroin and methamphetamine self-administration rat models. Further study of drugs of abuse in Anks1b model systems, particularly mouse knockouts, may yield insights into the interplay of learning, synaptic plasticity and development of drug dependence.

ANKS1B & antipsychotic-induced weight gain

Weight gain and metabolic dysregulation are significant side effects in patients taking APs, particularly second-generation APs [84]. Therefore, it is of interest that ANKS1B shows evidence for association with BMI/weight in addition to AP response. Several studies suggest that neurotransmitter and receptor interactions play a crucial role in gaining weight. For instance, NMDARs [85,86] and serotonin receptors [87] are involved in the control of appetite and bodyweight. Furthermore, the low density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins 1 and 2 (LRP1 and LRP2) are known interacting partners with ANKS1B protein (Figure 4). Both LRP1 and LRP2 are involved in CNS regulation of food intake and leptin signaling [88,89]. Taken together, these findings show that a link between ANKS1B and weight/BMI is plausible. It is perhaps surprising, therefore, that there is no current association evidence for ANKS1B genetic variants and susceptibility to AP-induced weight gain. Studies of long-term antipsychotic administration in rodent models may shed light on this issue.

Future perspective

Psychiatric drug response is accepted to be a complex, multifactorial phenotype, and it is thought that pharmacogenetics associations with psychiatric outcomes are likely to have small effect sizes. The detection of small effect sizes requires large samples, but the cost of clinical trials is prohibitive and psychiatric pharmacogenetic studies have been plagued with low power for this reason. Meta-analysis of several trials can also be challenging due to heterogeneity of trial designs (e.g., duration of trial, definition of response). However, large scale biobank samples such as the UK Biobank are now available for analysis and other samples such as the US ‘All of Us’ sample are being collected. The commercial genomics company 23andMe has shown that simple response phenotypes in large samples can yield potentially meaningful associations with psychiatric drug response (specifically antidepressants) [90]. As reported at the 26th World Congress of Psychiatric Genetics in Glasgow, October 2018, plans are being laid to harness the power of biobank data for psychiatric pharmacogenetics. These studies will allow ANKS1B's potential role in psychiatric drug response to be more fully characterized in the next 5–10 years. Considering ANKS1B's involvement in drug response beyond psychiatry, genome-wide significant findings with corticosteroid response and drug dependence have already been reported and further analysis of these phenotypes in rodent models is warranted. With two Anks1b knockout mouse lines already extant, one a CNS-specific knockout and the other a germ-line full body knockout, we expect to see significant progress in this area in the coming years.

Finally, we believe the relevance of ANKS1B lies in its role at the intersection between neurotransmission and activity-dependent, longer-term changes to neuronal biology. Jordan & Kreutz have stated that the ‘ability of a neuron to transduce activity-dependent signals into long-lasting changes in neuronal morphology is central to its normal function. Although changes in neuronal morphology can occur via local signaling at synapses, regulation of gene transcription is required to make these alterations into long-lasting effects [91]’. Therefore, understanding potential genetic regulatory interactions with ANKS1B, particularly those mediated by epigenetic changes, should be an area of interest in coming years. Studies in mice have already shown epigenetic changes at Anks1b after stress (see Epigenetics section) and protein expression changes following ethanol exposure. Therefore, pursuit of a mechanistic understanding of ANKS1B's response to stress and drugs and how this is translated into a change in gene expression will be an area of focus in coming years and we expect to see advances in understanding of these phenomena.

Executive summary.

Biology of ANKS1B

ANKS1B encodes an activity-dependent effector protein of the postsynaptic density.

Upon receptor stimulation, ANKS1B protein migrates to the nucleus and initiates long-term changes to neuronal biology.

ANKS1B has been implicated in the regulation of synaptic plasticity.

ANKS1B & antipsychotic drug response

ANKS1B was a top finding in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of antipsychotic drug response in the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) sample, but the results did not quite achieve genome-wide significance.

Subsequent pharmacogenetics studies that examined ANKS1B as a candidate gene found evidence for its mediating response to second-generation antipsychotics.

Genomic findings for ANKS1B: the broad perspective

Genome-wide significant associations for ANKS1B have emerged for cognitive ability, educational attainment, BMI, drug dependence and corticosteroid response.

Suggestive GWAS findings have also emerged for ANKS1B with CNS metabolites, skin conductance (a measure of arousal) and other phenotypes.

Sequencing studies have shown enrichment of ANKS1B mutations in schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorder.

Epigenetic & functional studies of ANKS1B

ANKS1B is differentially methylated in postmortem brain tissue from schizophrenia patients.

Anks1b showed differential epigenetic regulation in mice following stress, in utero THC exposure and in a learning paradigm.

Anks1b knockout mice exhibit reduced NMDA receptor-dependent long-term potentiation and long-term depression, two processes underlying learning and memory.

Ansk1b knockout mice also show alterations to sensorimotor gating, locomotor activity and NMDA receptor antagonism, all behavioral phenotypes of potential relevance to schizophrenia.

Summary & discussion

Phenotypically relevant variation at ANKS1B is segregating in the human population.

As a mediator of glutamatergic signaling in the CNS, ANKS1B is a clear candidate for involvement in cognitive phenotypes, CNS drug response and drug dependence.

ANKS1B protein interacts with serotonin receptor 2A, an antipsychotic drug target, and receptor tyrosine kinases such as ERBB4 that make it a plausible mediator of antipsychotic response.

ANKS1B protein also functionally interacts with low density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins that could (partially) explain the genetic associations with weight/BMI.

Future perspective

Large scale GWAS in biobanks of hundreds of thousands of patients will continue to delineate the phenotypes with which ANKS1B is associated.

Further analysis of mouse knockouts and other functional studies will provide further mechanistic understanding of the relationship between ANKS1B and drug response.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

RM Younis was funded through a graduate studentship from Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) School of Pharmacy and this review was completed in partial fulfillment of the doctoral requirements in Pharmaceutical Sciences at VCU. This work was funded through a pilot award from the Endowment Fund of the Wright Center for Clinical and Translational Research at VCU and UL1TR000058 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. JL McClay was partially supported by National Institute of Mental Health grant R56MH107879. PM Beardsley was supported by NIDA N01DA-14-8917, NIDA N01DA-17-8932 and DOJ D-17-OD-0092. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.Ghersi E, Vito P, Lopez P, Abdallah M, D'Adamio L. The intracellular localization of amyloid beta protein precursor (AbetaPP) intracellular domain associated protein-1 (AIDA-1) is regulated by AbetaPP and alternative splicing. J. Alzheimers Dis. 6(1), 67–78 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McClay JL, Adkins DE, Åberg K. et al. Genomewide pharmacogenomic analysis of response to treatment with antipsychotics. Mol. Psychiatry 16(1), 76–85 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • The earliest reported genome-wide association studies association with ANKS1B.

- 3.McClay JL, Adkins DE, Åberg K. et al. Genome-wide pharmacogenomic study of neurocognition as an indicator of antipsychotic treatment response in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 36(3), 616–626 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teng S, Yang JY, Wang L. Genome-wide prediction and analysis of human tissue-selective genes using microarray expression data. BMC Med. Genomics 6(Suppl. 1), S10 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Letunic I, Doerks T, Bork P. SMART: recent updates, new developments and status in 2015. Nucl. Acids Res. 43(D1), D257–D260 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunha SR, Mohler PJ. Ankyrin protein networks in membrane formation and stabilization. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 13(11–12), 4364–4376 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jordan BA, Fernholz BD, Boussac M. et al. Identification and verification of novel rodent postsynaptic density proteins. Mol. Cell Proteomics 3(9), 857–871 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lowenthal MS, Markey SP, Dosemeci A. Quantitative mass spectrometry measurements reveal stoichiometry of principal postsynaptic density proteins. J. Proteome Res. 14(6), 2528–2538 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernández E, Collins MO, Uren RT. et al. Targeted tandem affinity purification of PSD-95 recovers core postsynaptic complexes and schizophrenia susceptibility proteins. Mol. Systems Biol. 5(1), 269 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • An excellent empirical study of protein components of the postsynaptic density.

- 10.Fu X, McGrath S, Pasillas M, Nakazawa S, Kamps MP. EB-1, a tyrosine kinase signal transduction gene, is transcriptionally activated in the t(1;19) subset of pre-B ALL, which express oncoprotein E2a-Pbx1. Oncogene 18(35), 4920–4929 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jordan BA, Fernholz BD, Khatri L, Ziff EB. Activity-dependent AIDA-1 nuclear signaling regulates nucleolar numbers and protein synthesis in neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 10(4), 427–435 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• The first report of postsynaptic density to nucleus communication involving ANKS1B/AIDA-1.

- 12.Kurabi A, Brener S, Mobli M, Kwan JJ, Donaldson LW. A nuclear localization signal at the SAM-SAM domain interface of AIDA-1 suggests a requirement for domain uncoupling prior to nuclear import. J. Mol. Biol. 392(5), 1168–1177 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacob AL, Jordan BA, Weinberg RJ. The organization of amyloid-β protein precursor intracellular domain-associated protein-1 in the rat forebrain. J. Comp. Neurol. 518(16), 3221–3236 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dosemeci A, Toy D, Reese TS, Tao-Cheng J-H. AIDA-1 moves out of the postsynaptic density core under excitatory conditions. PLOS ONE 10(9), e0137216 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dosemeci A, Toy D, Burch A, Bayer KU, Tao-Cheng J-H. CaMKII–mediated displacement of AIDA-1 out of the postsynaptic density core. FEBS Lett. 590(17), 2934–2939 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dosemeci A, Weinberg RJ, Reese TS, Tao-Cheng J-H. The postsynaptic density: there is more than meets the eye. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 8, 23 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smirnova E, Shanbhag R, Kurabi A, Mobli M, Kwan JJ, Donaldson LW. Solution structure and peptide binding of the PTB domain from the AIDA1 postsynaptic signaling scaffolding protein. PLoS ONE 8(6), e65605 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saha S, Chant D, Welham J, McGrath J. A systematic review of the prevalence of Schizophrenia. PLoS Med. 2(5), e141 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia. Lancet 374(9690), 635–645 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malhotra AK, Murphy GM, Kennedy JL. Pharmacogenetics of psychotropic drug response. Am. J. Psychiatry 161(5), 780–796 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meltzer H, Massey B. The role of serotonin receptors in the action of atypical antipsychotic drugs. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 11(1), 59–67 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP. et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N. Engl. J. Med. 353(12), 1209–1223 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J-P, Malhotra AK. Pharmacogenetics of antipsychotics: recent progress and methodological issues. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 9(2), 183–191 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li J, Yoshikawa A, Brennan MD, Ramsey TL, Meltzer HY. Genetic predictors of antipsychotic response to lurasidone identified in a genome wide association study and by schizophrenia risk genes. Schizophr. Res. 192, 194–204 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang S-G, Chee I-S, Lee K, Lee J. rs7968606 polymorphism of ANKS1B is associated with improvement in the PANSS general score of schizophrenia caused by amisulpride. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 32(2), e2562 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Q, Wineinger NE, Fu D-J. et al. Genome-wide association study of paliperidone efficacy. Pharmacogenet. Genomics 27(1), 7–18 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stevenson JM, Reilly JL, Harris MSH. et al. Antipsychotic pharmacogenomics in first episode psychosis: a role for glutamate genes. Transl. Psychiatry 6, e739 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hawcutt DB, Francis B, Carr DF. et al. Susceptibility to corticosteroid-induced adrenal suppression: a genome-wide association study. Lancet Respir. Med. 6(6), 442–450 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Report of a genome-wide significant genomic association for ANKS1B and corticosteroid response.

- 29.Mahmoudpour SH, Veluchamy A, Siddiqui MK. et al. Meta-analysis of genome wide association studies (GWAS) on the intolerance of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. Pharmacogenet. Genomics 27(3), 112–119 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tian C, Hromatka BS, Kiefer AK. et al. Genome-wide association and HLA region fine-mapping studies identify susceptibility loci for multiple common infections. Nat. Commun. 8(1), 599 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahola-Olli AV, Würtz P, Havulinna AS. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 27 loci influencing concentrations of circulating cytokines and growth factors. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 100(1), 40–50 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goes FS, McGrath J, Avramopoulos D. et al. Genome-wide association study of schizophrenia in Ashkenazi Jews. Am. J. Med. Geneti. Part B 168(8), 649–659 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaidyanathan U, Isen JD, Malone SM, Miller MB, McGue M, Iacono WG. Heritability and molecular genetic basis of electrodermal activity: a genome-wide association study. Psychophysiology 51(12), 1259–1271 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luykx JJ, Bakker SC, Lentjes E. et al. Genome-wide association study of monoamine metabolite levels in human cerebrospinal fluid. Mol. Psychiatry 19(2), 228–234 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Identification of risk loci with shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet 381(9875), 1371–1379 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmeti KB, Ajroud-Driss S, Al-Chalabi A. et al. Age of onset of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is modulated by a locus on 1p34.1. Neurobiol.Aging 34(1), 357.e7–19 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Comuzzie AG, Cole SA, Laston SL. et al. Novel genetic loci identified for the pathophysiology of childhood obesity in the Hispanic population. PLoS ONE 7(12), e51954 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Croteau-Chonka DC, Marvelle AF, Lange EM. et al. Genome-wide association study of anthropometric traits and evidence of interactions with age and study year in Filipino women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 19(5), 1019–1027 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davies G, Lam M, Harris SE. et al. Study of 300,486 individuals identifies 148 independent genetic loci influencing general cognitive function. Nat. Commun. 9(1), 2098 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee JJ, Wedow R, Okbay A. et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nat. Genet. 50(8), 1112–1121 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yengo L, Sidorenko J, Kemper KE. et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for height and body mass index in ∼700,000 individuals of European ancestry. bioRxiv 274654 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun Y, Chang S, Liu Z. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies common genetic risk factors for alcohol, heroin and methamphetamine dependence. bioRxiv 505917 (2018). [Google Scholar]; •• Very significant preliminary report of ANKS1B mediating dependence on three different abused substances, plus functional confirmation in a rat self-administration model where Anks1b function was knocked down.

- 43.Cobb J, Cule E, Moncrieffe H. et al. Genome-wide data reveal novel genes for methotrexate response in a large cohort of juvenile idiopathic arthritis cases. Pharmacogenomics J. 14(4), 356–364 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garriock HA, Kraft JB, Shyn SI. et al. A genomewide association study of citalopram response in major depressive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 67(2), 133–138 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Umehara H, Numata S, Tajima A. et al. Calcium signaling pathway is associated with the long-term clinical response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and SSRI with antipsychotics in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. PLoS ONE 11(6), e0157232 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 511(7510), 421–427 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wray NR, Ripke S, Mattheisen M. et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat. Genet. 50(5), 668–681 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoffmann TJ, Choquet H, Yin J. et al. A large multiethnic genome-wide association study of adult body mass index identifies novel loci. Genetics 210(2), 499–515 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parker CC, Cheng R, Sokoloff G. et al. Fine-mapping alleles for body weight in LG/J × SM/J F2 and F(34) advanced intercross lines. Mamm. Genome 22(9–10), 563–571 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Purcell SM, Moran JL, Fromer M. et al. A polygenic burden of rare disruptive mutations in schizophrenia. Nature 506(7487), 185–190 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Castellani CA, Melka MG, Gui JL, Gallo AJ, O’Reilly RL, Singh SM. Post-zygotic genomic changes in glutamate and dopamine pathway genes may explain discordance of monozygotic twins for schizophrenia. Clin. Transl. Med. 6(1), 43 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li J, Shi M, Ma Z. et al. Integrated systems analysis reveals a molecular network underlying autism spectrum disorders. Mol. Syst. Biol. 10, 774 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grünblatt E, Oneda B, Ekici AB. et al. High resolution chromosomal microarray analysis in paediatric obsessive–compulsive disorder. BMC Med. Genomics 10(1), 68 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Han S, Lin Y, Wang M. et al. Integrating brain methylome with GWAS for psychiatric risk gene discovery. bioRxiv 440206 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aberg KA, Xie LY, McClay JL. et al. Testing two models describing how methylome-wide studies in blood are informative for psychiatric conditions. Epigenomics 5(4), 367–377 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kurita M, Holloway T, García-Bea A. et al. HDAC2 regulates atypical antipsychotic responses through the modulation of mGlu2 promoter activity. Nat. Neurosci. 15(9), 1245–1254 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Papale LA, Madrid A, Li S, Alisch RS. Early-life stress links 5-hydroxymethylcytosine to anxiety-related behaviors. Epigenetics 12(4), 264–276 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Papale LA, Li S, Madrid A. et al. Sex-specific hippocampal 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is disrupted in response to acute stress. Neurobiol. Dis. 96, 54–66 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watson CT, Szutorisz H, Garg P. et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling reveals epigenetic changes in the rat nucleus accumbens associated with cross-generational effects of adolescent THC exposure. Neuropsychopharmacology 40(13), 2993–3005 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sewal AS, Patzke H, Perez EJ. et al. Experience modulates the effects of histone deacetylase inhibitors on gene and protein expression in the hippocampus: impaired plasticity in aging. J. Neurosci. 35(33), 11729–11742 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Enga RM, Rice AC, Weller P. et al. Initial characterization of behavior and ketamine response in a mouse knockout of the post-synaptic effector gene Anks1b. Neurosci. Lett. 641, 26–32 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tindi JO, Chávez AE, Cvejic S, Calvo-Ochoa E, Castillo PE, Jordan BA. ANKS1B gene product AIDA-1 controls hippocampal synaptic transmission by regulating GluN2B subunit localization. J. Neurosci. 35(24), 8986–8996 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Important study of forebrain specific Anks1b knockout and effects on synaptic plasticity.

- 63.Braff D, Stone C, Callaway E, Geyer M, Glick I, Bali L. Prestimulus effects on human startle reflex in normals and schizophrenics. Psychophysiology 15(4), 339–343 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Braff DL, Grillon C, Geyer MA. Gating and habituation of the startle reflex in schizophrenic patients. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 49(3), 206–215 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Geyer MA, Krebs-Thomson K, Braff DL, Swerdlow NR. Pharmacological studies of prepulse inhibition models of sensorimotor gating deficits in schizophrenia: a decade in review. Psychopharmacology 156(2–3), 117–154 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lüscher C, Malenka RC. NMDA receptor-dependent long-term potentiation and long-term depression (LTP/LTD). Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4(6), pii: a005710 (2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hardy J. Amyloid, the presenilins and Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neuroscie. 20(4), 154–159 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Duyckaerts C, Delatour B, Potier M-C. Classification and basic pathology of Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 118(1), 5–36 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scholz C-J, Weber H, Jungwirth S. et al. Explorative results from multistep screening for potential genetic risk loci of Alzheimer's disease in the longitudinal VITA study cohort. J. Neural. Transm. (Vienna) 125(1), 77–87 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ianov L, Rani A, Beas BS, Kumar A, Foster TC. Transcription profile of aging and cognition-related genes in the medial prefrontal cortex. Front. Aging Neurosci. 8, 113 (2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Webb A, Papp AC, Curtis A. et al. RNA sequencing of transcriptomes in human brain regions: protein-coding and non-coding RNAs, isoforms and alleles. BMC Genomics 16, 990 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sheffler DJ, Kroeze WK, Garcia BG. et al. p90 ribosomal S6 kinase 2 exerts a tonic brake on G protein-coupled receptor signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103(12), 4717–4722 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.de Bartolomeis A, Buonaguro EF, Iasevoli F. Serotonin–glutamate and serotonin–dopamine reciprocal interactions as putative molecular targets for novel antipsychotic treatments: from receptor heterodimers to postsynaptic scaffolding and effector proteins. Psychopharmacology 225(1), 1–19 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abbas AI, Yadav PN, Yao W-D. et al. PSD-95 is essential for hallucinogen and atypical antipsychotic drug actions at serotonin receptors. J. Neurosci. 29(22), 7124–7136 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Iasevoli F, Ambesi-Impiombato A, Fiore G, Panariello F, Muscettola G, de Bartolomeis A. Pattern of acute induction of Homer1a gene is preserved after chronic treatment with first- and second-generation antipsychotics: effect of short-term drug discontinuation and comparison with Homer1a-interacting genes. J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford) 25(7), 875–887 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Balu DT, Coyle JT. Neuroplasticity signaling pathways linked to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 35(3), 848–870 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Deng C, Pan B, Engel M, Huang X-F. Neuregulin-1 signalling and antipsychotic treatment: potential therapeutic targets in a schizophrenia candidate signalling pathway. Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 226(2), 201–215 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI. et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature 518(7538), 197–206 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chang X, Lima L, Liu Y. et al. Common and rare genetic risk factors converge in protein interaction networks underlying schizophrenia. Front. Genet. 9, 434 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.D'Uva G, Lauriola M. Towards the emerging crosstalk: ERBB family and steroid hormones. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 50, 143–152 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Faralli JA, Gagen D, Filla MS, Crotti TN, Peters DM. Dexamethasone increases αvβ3 integrin expression and affinity through a calcineurin/NFAT pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833(12), 3306–3313 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Volkow ND, Morales M. The brain on drugs: from reward to addiction. Cell 162(4), 712–725 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mulholland PJ, Jordan BA, Chandler LJ. Chronic ethanol up-regulates the synaptic expression of the nuclear translational regulatory protein AIDA-1 in primary hippocampal neurons. Alcohol 46(6), 569–576 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Malhotra AK, Murphy GM, Kennedy JL. Pharmacogenetics of psychotropic drug response. AJP 161(5), 780–796 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Guard DB, Swartz TD, Ritter RC, Burns GA, Covasa M. NMDA NR2 receptors participate in CCK-induced reduction of food intake and hindbrain neuronal activation. Brain Res. 1266, 37–44 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ritter RC. A tale of two endings: modulation of satiation by NMDA receptors on or near central and peripheral vagal afferent terminals. Physiol. Behavior. 105(1), 94–99 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nonogaki K, Strack AM, Dallman MF, Tecott LH. Leptin-independent hyperphagia and Type 2 diabetes in mice with a mutated serotonin 5-HT2C receptor gene. Nat. Med. 4(10), 1152–1156 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mao H, Lockyer P, Li L. et al. Endothelial LRP1 regulates metabolic responses by acting as a co-activator of PPARγ. Nat. Commun. 8, 14960 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gil SY, Youn B-S, Byun K. et al. Clusterin and LRP2 are critical components of the hypothalamic feeding regulatory pathway. Nat. Commun. 4, 1862 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Li QS, Tian C, Seabrook GR, Drevets WC, Narayan VA. Analysis of 23andMe antidepressant efficacy survey data: implication of circadian rhythm and neuroplasticity in bupropion response. Transl. Psychiatry 6(9), e889 (2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jordan BA, Kreutz MR. Nucleocytoplasmic protein shuttling: the direct route in synapse-to-nucleus signaling. Trends Neurosci. 32(7), 392–401 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]