Abstract

Objectives:

Hospital trauma activation criteria are intended to identify children who are likely to require aggressive resuscitation or specific surgical interventions that are time sensitive and require the resources of a trauma team at the bedside. Evidence to support criteria is limited, and no prior publication has provided historical or current perspectives on hospital practices toward informing best practice. This study aimed to describe the published variation in (1) highest level of hospital trauma team activation criteria for pediatric patients and (2) hospital trauma team membership and (3) compare these finding to the current ACS recommendations.

Methods:

Using an Ovid MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations search, any published description of hospital trauma team activation criteria for children that used information captured in the prehospital setting was identified. Only studies of children were included. If the study included both adults and children, it was included if the number of children assessed with the criteria was included.

Results:

Eighteen studies spanning 20 years and 13,184 children were included. Hospital trauma team activation and trauma team membership were variable. Nearly all (92%) of the trauma criteria used physiologic factors. Penetrating trauma (83%) was frequently included in the trauma team activation criteria. Mechanisms of injury (52%) were least likely to be included in the highest level of activation. No predictable pattern of criterion adoption was found. Only 2 of the published criteria and 1 of published trauma team membership are consistent with the current American College of Surgeons recommendations.

Conclusions:

Published hospital trauma team activation criteria and trauma team membership for children were variable. Future prospective studies are needed to define the optimal hospital trauma team activation criteria and trauma team membership and assess its impact on improving outcomes for children.

Keywords: trauma/emergency team, emergency medical services, wounds and injury

When children are transported to a trauma center, emergency medical services providers communicate the condition of the child to the emergency department (ED) staff before arrival. That information is used to determine whether the trauma team should be activated so that they are present in the ED when the patient arrives. Hospital trauma activation criteria are intended to identify children who are likely to require aggressive resuscitation or specific surgical interventions that are time sensitive and require the resources of a trauma team at the bedside. Presence of the trauma team has been shown to decrease mortality by 25% to 30% for the seriously injured child.1 Overuse of the trauma team, however, can lead to excess costs and resource use as well as provider fatigue. Indeed activating the trauma team only when a critically injured patient is identified has been shown to reduce costs in adult and pediatric trauma patients.2,3

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) Committee on Trauma described a tiered trauma team activation that is based on predetermined prehospital criteria.4 These criteria are distinct from the prehospital triage criteria that are used to identify patients that need the services of a trauma center. The ACS proposes 6 criteria that serve as the minimum criteria that should be used for the highest level trauma team activation, as follows:

Age-specific hypotension: systolic blood pressure less than 70 mm Hg + (2 × age in years);

Gunshot wound to the neck, chest, or abdomen or extremities proximal to the elbow/knee;

Glasgow Coma Scale less than 9 or deteriorating by 2, with mechanism attributed to trauma;

Transfer patients from other hospitals receiving blood to maintain vital signs;

Intubated patients transferred from the scene or patients who have respiratory compromise or are in need of an emergency airway or intubated patients who are transferred from another facility with ongoing respiratory compromise;

Discretion of the emergency physician;

Trauma centers can expand on these criteria to include any of the prehospital information that is available. This typically includes physiologic, anatomic, and mechanism of injury criteria. There is no referenced evidence to support the ACS recommendations, although they parallel in content the minimum criteria for adults.

Trauma team members that usually respond to the activation are also outlined by the ACS.4

General surgeon

Emergency physician

Surgical and emergency residents

Emergency department nurses

Laboratory technician

Radiology technologist

Critical care nurse

Anesthesiologist or certified registered nurse anesthetist

Operating room nurse

Security officers

Chaplain or social worker

Scribe

The rationale for this systematic review is to evaluate the published evidence and compare it with the recommended criteria and team composition for the pediatric trauma patient. This synthesis of data is an incremental step toward understanding current practice, identifying variability, and optimizing hospital trauma activation criteria for children. The objective of this systematic review was to describe for pediatric patients (1) the variation in highest level of hospital trauma team activation criteria and (2) trauma team membership. Lastly, we sought to (3) compare these finding with the current ACS recommendations.

METHODS

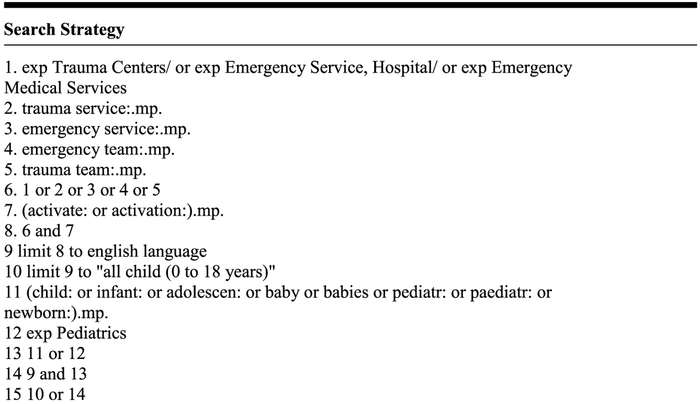

Studies were identified with a search of Ovid MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily, and Ovid MEDLINE using search terms outlined in Figure 1, including only human trials without language restriction. Trauma/emergency service and trauma/emergency team were the terms chosen to search broadly for any publications on the topic, and then, the search was focused to include all children aged 0 to 18 years. A published protocol does not exist for this systematic review. All databases were searched from inception until January 3, 2015. To be included in this review, studies had to describe hospital trauma team activation criteria for pediatric patients that were assessed in the prehospital setting. Studies that included both children and adults were included if trauma activation criteria and number of children evaluated were included separately. Studies that included only prehospital triage criteria that are used to identify patients that need the services of a trauma center were not included. Studies that included only a specific population (ie, winter sports injuries) or mechanism of injury (ie, horse-related injuries) or simply interhospital transfers were excluded. Reference lists from studies included in the analyses were reviewed by hand to identify additional articles meeting criteria, and no additional articles were identified.

FIGURE 1.

Search strategy.

Data were abstracted by a single author (A.D.). Patient characteristics, trauma activation criteria, and trauma team membership were abstracted from each publication. These were reviewed and specific criteria and trauma team members that were shared between publications were used to populate the rows of the tables. The data were then abstracted a second time from each of the publications directly into the tables. Finally, the data in the table were then compared with the published manuscript on a third review to assure accuracy. Patient characteristics included dates of inclusion, patient age, number of trauma patients overall during study enrollment, number transferred to the operating room (variable definitions of emergent operative cases), deaths (including ED deaths, when available), and number of trauma activations. Trauma activation criteria were divided into categories for ease of reporting: physiologic, penetrating, anatomic, mechanism of injury, and other criteria. Criteria were assigned to each of these 5 categories based on their most frequent assignment in the published literature. If the study specifically excluded a population (eg, penetrating injuries or drowning) this was designated as “*” in the table, and the proportion of criteria with that criterion was calculated using only the criteria that included the population. This review is focused on the highest level (most severely injured) of trauma team activation. When the publication included graded or tiered response activation, this was noted in Table 1, but only the highest-level criteria were reported in Table 2. If 2 different criteria were compared, then both criteria were included. The current ACS recommendations were also included for comparison. The membership for the trauma team activated for the highest level activation was also abstracted, and the current ACS recommendations included for comparison.

TABLE 1.

Studies Included in the Systematic Review

| Author | Journal | Publication Year |

Enrollment Years |

Age | Total Trauma Patients |

Operating Room |

Deaths (ED deaths) |

Trauma Activations |

Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sola, JE | Journal of Pediatric Surgery | 1994 | 1/19/91–2/6/92 | 0–14 | 26 | 15 | 216 | Baltimore "Alpha" | |

| 5 | 0 | 736 | Baltimore "Bravo" | ||||||

| DeKeyser | Annals of Emergency Medicine | 1994 | 1991 | 214 | Fairfax Blue | ||||

| DeKeyser | Annals of Emergency Medicine | 1994 | 1991 | 604 | Fairfax Yellow | ||||

| Quazi | Academic Emergency Medicine | 1998 | 7/12/96–2/28/97 | 0–14 | 192 | 12 | Akron Paramedic | ||

| Quazi, K | Journal of Trauma | 1998 | 7/1/93–7/31/94 | 0–14 | 0 | 0 | 194 | Akron Mechanism | |

| Vernon, DD | Pediatrics | 1999 | 638 | 8 | 7 | 49 | Salt Lake City "Trauma One" | ||

| Dowd, MD | Academic Emergency Medicine | 2000 | 1/1/96–12/31/96 | 0–15 | 492 | 32 | 21 | 179 | Cincinnati Trauma Team Activation |

| Nuss, KE | Pediatric Emergency Care | 2001 | 1/1/95–12/31/96 | 542 | 26 | 39 (6 ED) | 253 | Columbus Level 1 | |

| 22 | 1 (0 ED) | 289 | Columbus Level 2 | ||||||

| Chen, LE | Pediatric Emergency Care | 2004 | 1994–1999 | 0–19 | 5122 | 44 | (15 ED) | 220 | St Louis Trauma Stat |

| 40 | (0 ED) | 250 | St Louis Trauma Minor | ||||||

| Simon, B | Pediatric Emergency Care | 2004 | 1990–2001 | 0–13 | 1112 | 21 | 6 | 461 | mPTS |

| Edil, BH | Journal of Pediatric Surgery | 2005 | 1/2000–1/2004 | 0–13 | 118 | 4 | 18 | 40 | Oklahoma Level 1 Alert |

| Steele, R | Annals of Emergency Medicine | 2006 | 1/1/97–6/30/04 | 0–14 | 2311 | 8/62/121 | 87/166/836 | Loma Linda Peds | |

| Steele, R | Annals of Emergency Medicine | 2007 | 1/1/97–6/30/04 | 0–14 | 2311 | 8/62/121 | 534 | ACS Criteria 2002 | |

| Nasr, A | Journal of Trauma | 2007 | 1993–2003 | 0–15 | 3579 | 628 | Toronto mPTS | ||

| Bevan, C | Journal of Trauma | 2009 | 4/2004–4/2006 | 0–15 | ~4400 | 6 | 192 | Melbourne #1 | |

| 7 | 82 | Melbourne #2 | |||||||

| Kouzminova | Journal of Trauma | 2009 | 1998–2007 | Santa Clara Major | |||||

| Kouzminova | Journal of Trauma | 2009 | 1998–2007 | * | Santa Clara Minor | ||||

| Mukherjee, K | Journal of Pediatric Surgery | 2010 | 1 y | 0–14 | 152 | 18 | 10 | 98 | Vanderbilt (physiologic focused) |

| 25 | Vanderbilt (standard) | ||||||||

| Davis | Injury, International J. Care Injured | 2010 | 2008 | * | 57 | 18 | 468/676 | South Wales | |

| Williams, D | Journal of Pediatric Surgery | 2011 | 2006–2008 | 0–14 | 4502 | 2118 | 48 | 211 | UT Southwestern Stat |

| 29 | 1104 | UT Southwestern Alert | |||||||

| Bozeman, AP | The American Journal of Surgery | 2012 | 1/1/2009–2/10/2011 | 0–14 | 271 | 176 | Arkansas Restraints | ||

| Krieger, AR | Journal of Trauma Acute Care Surgery | 2012 | 1/2006–3/2009 | 0–18 | 2538 | St. Louis Traum Stat MOI | |||

| 4/2009–6/2010 | 1088 | St. Louis Trauma Major ABP | |||||||

| Falcone, RA | Journal of Trauma Acute Care Surgery | 2012 | 1 y | 0–20 | 9722 | 144 | 72 (24 ED) | 656 | Multicenter |

| Nabaweesi, R | Pediatric Surgery International | 2014 | 1/1/2008–12/31/2011 | 0–14 | 2235 | 37 | 7 | 369 | Arkansas FTTA |

| 1766 | Arkansas PTTA |

TABLE 2.

Published Hospital Trauma Activation Criteria for Children

| Author and Pub Year | Sola 1994 | Quazi 1998 | Vernon 1999 | Dowd 2000 | Nuss 2001 | Chen 2004 | Simon 2004 | Edil 2005 | Steele 2006 | Steele 2007 | Nasr 2007 | Bevan 2009 | Mukherjee 2010 | Williams 2011 | Bozeman 2012 | Krieger 2012 | Falcone 2012 | Nabaweesi 2014 | % of Criteria | ACS Criteria | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria type (if multiple) | Physio | Anat | PTS | mPTS | Criteria | ACS 2002 | mPTS | 1 of 3 | single | Physio | mechanism | anat/physio | |||||||||||||||||

| Physiologic criteria | Cardiopulmonary arrest | penetrating trauma | 28 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Systolic Blood Pressure (SBP) | <80 | age-specific | age-specific | <80 | hypotension | <80 | <90 | age-specific | age-specific | <80 | <90 | hypotension | hypotension | hypotension | hypotension | age-specific | age-specific | age-specific | 72 | ||||||||||

| Heart rate | >130 <50 | age-specific | tachcardia | age-specific | age-specific | age-specific | tachcardia | tachcardia | tachcardia | tachcardia | age-specific | 44 | |||||||||||||||||

| Pulse quality | weak pulse | 2 | 2 | weak/absent | 16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Perfusion quality | CRF>3 sec | "poor" | cool, clammy, CRF | >2 | CRF >2 sec | cool, dammy, CRF | cyanosis | 24 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Clinical signs of shock | 32 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Blood transfusion | 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| IV fluid bolus | >40 cc/kg | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ongoing blood loss | or sig blood loss | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resp compromise/ distress | airway integrity | airway integrity | airway integrity | airway compromise | unstable airway | unstable airway | grunt/retract | 72 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Intubation | with blood | 52 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Airway foreign body / obstruction | 24 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stridor | 20 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Respiratory rate | >30, <20 | age-specific | >30 | age-specific | age-specific | <10>50 | tachypnea | age-specific | 32 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Glasgow Coma Scale | <9 | <8 | <9 | <9 | <14 | <9 | <8 | <8 | <8 | <8 | <8 | <8 | <13 | <13 | <8 | <9 | 68 | ||||||||||||

| Suspected spinal cord injury | w paralysis | cervical | 44 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Paralysis | 24 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Focal neuro deficit | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deteriorating level of consciousness | GCS by 2 | 20 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Agitated or confused or altered | 24 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Loss of consciousness | >5 min | <5 min | >5 min | >5 min | >5 min | 24 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Any physiologic Criteria | 92 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Penetrating | GSW | * | * | Penetrating injury | * | * | Penetrating mechanism | * | * | * | 16 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Penetrating injury to extremity | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 27 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Penetrating injury to abdomen | * | * | * | * | * | or pelvis | or pelvix | or pelvis | * | +GSW, BB | * | 66 | |||||||||||||||||

| Penetrating injury to neck | * | * | * | * | * | * | +GSW, BB | * | 77 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Penetrating injury to head | * | * | and face | * | * | * | * | +GSW, BB | * | 77 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Penetrating injury to torso | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 27 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Penetrating injury to trunk | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 22 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Penetrating injury to the thorax | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 22 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Penetrating injury to groin | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 38 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Penetrating injury to chest | * | * | * | * | * | * | +GSW. BB | * | 50 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Any penetrating criteria | * | * | * | * | * | * | 83 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anatomic Criteria | Maxlllo/Faclal/Tracheal Injury | 24 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Open or depressed skull fx | 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CFS leak | 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Flail chest | 24 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Open chest wound | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pneumothorax | open | or hemo | or hemo | or hemo | 20 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cardiac/great vessel injury | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crush of torso | crush | crush | 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crush of chest or abdomen | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Peritonitis | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burns; total | * | >30% BSA | >30% BSA | >20% BSA | >10% BSA | * | >20% BSA | >20 BSA | >40% TBSA | >30% BSA | * | 41 | |||||||||||||||||

| Burn; 2nd and 3rd degree | * | >15% BSA | * | burns >40% | >15% BSA | * | 14 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Suspected airway injury from burn | * | * | * | * | 41 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Long bone fractures | 2+ | 2+ | 2+* | 2+ | 2+ | upper/lower | multile | 2+ | 32 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Pelvic fracture/injury | with tachycardia and hypotension | 20 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Skeletal integrety | 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Axial skeleton fracture | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arterial bleeding | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vascular injury | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pulseless extremity | 16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Amputation or degloving | proximal | proximal | or crush proximal | proximal | 56 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 systems injured | 16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Blunt abdominal trauma | seatbelt sign | abd injury | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Injury above and below diaphragm | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Severe head or neck injury | midline shift | scalp wound | intracranial injury GCS<14 | intracranial bleed | 20 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Severe chest or abdominal injury | with tachycardia and hypotension | 12 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| subq emphysema | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Open wound | 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Any anatomic criteria | 76 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mechanism Criteria | MVC unrestrained | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MVC with ejection | 36 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MVC with prolonged extrication | > 20 min | >20 min | >20 min | 12 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MVC with roll-over | >70 mph | 20 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MVC with death in same car | 32 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MVC >20 mph | unrestrained | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MVC >40 mph | restrained | 8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Run-over or dragged by car | or thrown | 12 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Major auto deformity >50 cm | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MVC intrusion | >20 in | >12 in | >30 cm | >18 inches | 20 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MPC/MBC | thrown 15 ft | 10 mph | >20 mph | >20 mph | >20 mph | 10 km/hr/30 km/hr | including horse | 28 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Drowning | * | * | * | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fall | >20 ft | >20 ft | >10 ft | 3x height | 3x height | >3m | >20 ft | 28 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Lightening strike / Electric shock | >200 v | >200 v | 20 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Trauma In a hostile environment | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanging or strangulation | * | * | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| High velocity impact | explosion | 12 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Any mechanism criteria | 52 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other | Multiple simultaneous victims | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Trauma score <12 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Child abuse with viral signs change | * | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ambulance discretion | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Trauma transfer with criteria | * | 12 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MD discretion | 16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Patients with these findings were explicitly excluded.

RESULTS

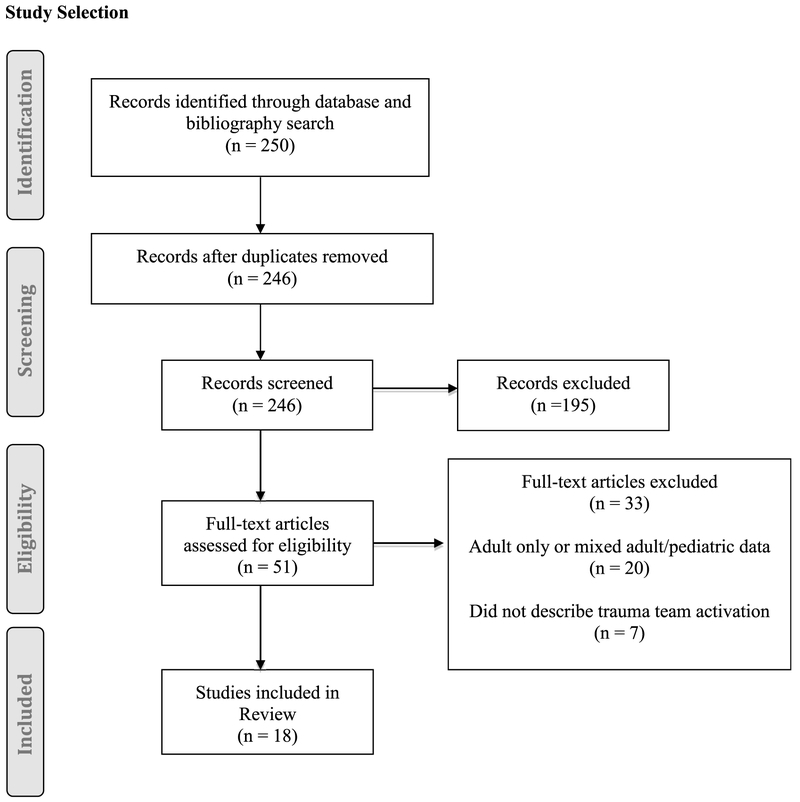

The search identified 246 articles. Two review authors (A.D. and M.G.) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all citations identified by the search (Fig. 2). Full articles were obtained when they seemed to meet the inclusion criteria or there were insufficient data in the title and abstract to make a clear decision for inclusion. The inclusion of the studies was made after reviewing the full-text articles. Agreement between reviewers was excellent for inclusion of articles, with a Kappa coefficient of 0.91 (0.81, 1.00). Disagreements were resolved between the 2 review authors about study inclusion by discussion and consensus.

FIGURE 2.

Study selection.

Application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria resulted in 18 studies and 25 criteria that were included in our analysis (Fig. 1).2,5-21 Table 1 shows the included studies and criteria. All but 1 were retrospective cohort studies. The only prospective study empirically derived pediatric trauma activation criteria.13 Many (39%) described 2-tiered trauma team activation criteria.5,8-10,16,17,21 A number of studies evaluated the accuracy of criteria categories including mechanism6,8,18,19 and physiologic criteria2 as well as simplified criteria including only respiratory compromise and intubation.12 Two studies evaluated variations of the Pediatric Trauma Score,11,15 and 2 studies applied the current ACS criteria to the trauma population.14,20 The included articles spanned 20 years, and 13,184 children meeting the trauma activation criteria were included. Most studies reported the number of children that underwent surgery and number of deaths (Table 1), but this inconsistent reporting limits the ability to compare injury severity.

Physiologic factors reported for trauma team activation generally included assessments for airway integrity, respiratory distress or compromise, signs of shock or resuscitation requirements, and the Glasgow Coma Scale. Nearly all (92%) of the trauma criteria used physiologic factors (Table 2), and most included respiratory compromise (72%), although this was inconsistently defined between studies. Specifically, an intervention for airway compromise like intubation (52%) was reported more often than respiratory rate (32%), but intervention for shock including fluid bolus (8%) and blood transfusion (12%) was less frequent than heart rate (44%) or blood pressure (72%). Cardiopulmonary arrest was the designated criterion for only 28% of trauma activation criteria. Most activation criteria included Glasgow Coma Scale (68%), but the threshold score was variably defined between 8 and 14.

Penetrating trauma (83%) was frequently included in the trauma team activation criteria (Table 2). For penetrating trauma, the site of injury was inconsistent between studies including head (77%), neck (77%), abdomen (66%), chest (50%), groin (38%), and extremity (27%). Anatomic factors (76%) were commonly included, but there was significant variability in the factors included, with the most common criteria being amputation or degloving (56%), burns or suspected airway injury from burns (41%), long bone fractures (32%), facial/tracheal injury (24%), and flail chest (24%). Some published criteria depended heavily on anatomic factors to identify trauma team activation criteria including 14 specific injuries,2 but 6 criteria included no anatomic factors at all.6,7,12-14,18

Mechanisms of injury (52%) were least likely to be included in the highest level of activation (Table 2). The most frequently included criteria were motor vehicle crash with ejection (36%), death in the same car (32%), and falls (28%). A number of unique trauma team activation criteria were included that did not meet the standard categories and are also included in Table 2. One of these, emergency physician's discretion, is now recommended by the ACS but was infrequently included (16%).

Of the studies included in this systematic review, 12 studies reported their trauma team composition (Table 3). The average number of trauma team members was 14 (range, 6–19). All activation criteria included a surgeon, although the level of training required was variable, and most included an ED physician (92%).

TABLE 3.

Trauma Team Composition

| Author and Publication Year | Sola 1994 | Quazi 1998 | Vernon 1999 | Dowd 2000 | Nuss 2001 | Chen 2004 | Simon 2004 | Nasr 2007 | Bevan 2009 | Mukheijee 2010 | Williams 2011 | Nabaweesi 2014 | ACS 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery attending | |||||||||||||

| Surgery fellow | |||||||||||||

| Surgery Sr resident | |||||||||||||

| Surgery Jr resident | |||||||||||||

| PICU attending | |||||||||||||

| PICU fellow | |||||||||||||

| PICU resident | senior | ||||||||||||

| ED attending | or | or | |||||||||||

| PEM fellow | |||||||||||||

| EM resident | or | senior | |||||||||||

| Pediatric resident | |||||||||||||

| Pediatrics | |||||||||||||

| Anesthesiologist | |||||||||||||

| Anesthesiologist resident | |||||||||||||

| Peds Neurosurgery | |||||||||||||

| Orthopeds | |||||||||||||

| RN supervisor | |||||||||||||

| OR Charge RN/RN | |||||||||||||

| OR personnel/team | |||||||||||||

| PICU RN | |||||||||||||

| PICU Charge RN | |||||||||||||

| ER RN | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| Float RN | |||||||||||||

| Phlebotomist | |||||||||||||

| Respiratory therapist | |||||||||||||

| Radiology tech | |||||||||||||

| Radiologist | |||||||||||||

| Pharmacist | |||||||||||||

| Distribution | |||||||||||||

| Chaplain / Patoral Care | or | ||||||||||||

| Social Services | |||||||||||||

| Security | |||||||||||||

| Orderly | |||||||||||||

| Blood products / Blood Bank | |||||||||||||

| Administrative supervisor | |||||||||||||

| Trauma nurse coordinator | |||||||||||||

| Patient service attendant | |||||||||||||

| Scribe | |||||||||||||

| Number of participants | 9 | 12 | 12 | 18 | 13 | 19 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 18 | 18 *team members not identified |

6 | 13 |

Current ACS guidelines recommend only physiologic factors. Only 2 of the published pediatric trauma activation criteria in this review included all elements.14,20 The currently recommended ACS trauma team member response for highest level activations for a severely injured patient include 12 people.4 None of the published team compositions included all of the ACS-recommended members.

DISCUSSION

The published literature about hospital trauma team activation for pediatric patients shows a significant amount of variability in the criteria used and the team that is commenced. This historical perspective provides the opportunity to evaluate the evolution of trauma team activation criteria during the last 20 years, but this evidence shows no predictable pattern of criterion adoption or any data to support the current criteria. Nor any evidence to support the value of these criteria in identifying children who require the activation of a trauma team. Prospective research is needed to evaluate the criteria used for trauma team activation for children.

The initial assessment and evaluation of severely injured trauma patients begins with the prehospital assessment and care. This information is used for both destination decision-making as well as hospital trauma team activation. The cost of missing a severely injured child during destination decision-making can be significant because of hours of delay for the child to be evaluated at a lower level or nontrauma center and then for the child to be transported to a higher level trauma center. In fact, the typical goal is for the transfer to occur in 2 to 3 hours. In contrast, if the hospital trauma team is not activated for a severely injured child being transported to a trauma center, the delay will be much shorter. However, for some critically injured patients, even a short delay will affect morbidity and mortality. This suggests the tradeoff between sensitivity and specificity, for the 2 criteria can be different. For destination decision-making, a goal of 5% undertriage and 30% to 50% overtriage is often quoted, but for hospital trauma activation, it might be reasonable to increase the rate of undertriage to decrease the overtriage rate.22 This would lead to a better use of resources and likely a minimal change in morbidity and mortality.

Trauma centers have published their experiences evaluating potential criteria for trauma team activation because most centers have developed their criteria based on experiences at their center. Historically, most trauma centers included more anatomic and mechanistic factors. This review did not find a reduced number of criteria over time as one might expect with performance review. This systematic review found that pediatric hospital trauma team activation criteria used are consistently inconsistent, not based in empiric evidence, and not consistent with the most recent published guidelines.

The evidence to support each criterion is lacking based on the findings of this systematic review. Only 1 study evaluated each factor (as opposed to full criteria), and the same study was the only prospectively performed study.13 Future investigations should include a rigorous evaluation of each factor with the determination of the incremental improvement to the undertriage and overtriage rates for injured children. Most of the included studies did evaluate the undertriage and overtriage rates for the overall trauma activation criteria. However, there was no consistency in the outcome used to define the need for a trauma center, making comparisons impossible in this study. Multidisciplinary performance improvement to refine the undertriage and overtriage rates and the appropriateness of prehospital-based trauma team activations has been recommended. A recent publication of that consensus statement should lead to stronger evidence to support the selection of criteria.23

This study has limitations. Synthesis of results by combining studies to assess the accuracy of the hospital trauma team activation criteria was not possible because of the inconsistent use of outcomes to assess the criteria. The published literature may not represent clinical practice and may not provide accurate insights into historical practices. However, many institutions rely on the published literature to inform system changes, and this review provides an excellent summary of that information.

In conclusion, published hospital trauma team activation criteria and trauma team membership for children were historically variable. No predictable pattern of criterion adoption was found. The published criteria are also dissimilar from the current ACS-recommended criteria. Future prospective studies are needed to define the optimal hospital trauma team activation criteria and trauma team membership and assess its impact on improving outcomes for children.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Rita Sieracki, reference librarian at the Medical College of Wisconsin, for her assistance in performing the literature search for this article.

This study was supported by grant R01HD075786 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Presented: Pediatric Academic Societies, San Diego CA, May 2015.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stafford PW, Blinman TA, Nance ML. Practical points in evaluation and resuscitation of the injured child. Surg Clin North Am. 2002;82: 273–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mukherjee K, Rimer M, McConnell MD, et al. Physiologically focused triage criteria improve utilization of pediatric surgeon-directed trauma teams and reduce costs. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:1315–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ochsner MG, Schmidt JA, Rozycki GS, et al. The evaluation of a two-tier trauma response system at a major trauma center; is it cost effective and safe? J Trauma. 1995;39:971–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient 2014. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sola JE, Scherer LR, Haller JA, et al. Criteria for safe cost-effective pediatric trauma triage: prehospital evaluation and distribution of injured children. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:738–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qazi K, Wright MS, Kippes C. Stable pediatric blunt trauma patients: is trauma team activation always necessary? J Trauma. 1998;45: 562–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vernon DD, Furnival RA, Hansen KW, et al. Effect of a pediatric trauma response team on emergency department treatment time and mortality of pediatric trauma victims. Pediatrics. 1999;103:20–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dowd MD, McAneney C, Lacher M, et al. Maximizing the sensitivity and specificity of pediatric trauma team activation criteria. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1119–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nuss KE, Dietrich AM, Smith GA. Effectiveness of a pediatric trauma team protocol. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2001;17:96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen LE, Snyder AK, Minkes RK, et al. Trauma stat and trauma minor: are we making the call appropriately? Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004u20: 421–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simon B, Gabor R, Letourneau P. Secondary triage of the injured pediatric patient within the trauma center: support for a selective resource-sparing two-stage system. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004;20:5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edil BH, Tuggle DW, Jones S, et al. Pediatric major resuscitation—respiratory compromise as a criterion for mandatory surgeon presence. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:926–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steele R, Green SM, Gill M, et al. Clinical decision rules for secondary trauma triage: predictors of emergency operative management. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steele R, Gill M, Green SM, et al. Do the American College of Surgeons' "major resuscitation" trauma triage criteria predict emergency operative management? Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nasr A, Mikrogianakis A, McDowall D, et al. External validation and modification of a pediatric trauma triage tool. J Trauma. 2007;62:606–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bevan C, Officer C, Crameri J, et al. Reducing "Cry Wolf"—Changing trauma team activation at a pediatric trauma centre. J Trauma. 2009;66:698–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams D, Foglia R, Megison S, et al. Trauma activation: are we making the right call? A 3-year experience at a Level I pediatric trauma center. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:1985–1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bozeman AP, Dassinger MS, Recicar JF, et al. Restraint status improves the predictive value of motor vehicle crash criteria for pediatric trauma team activation. Am J Surg. 2012;204:933–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krieger AR, Wills HE, Green MC, et al. Efficacy of anatomic and physiologic indicators versus mechanism of injury criteria for trauma activation in pediatric emergencies. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73: 1471–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Falcone RA Jr, Haas L, King E, et al. A multicenter prospective analysis of pediatric trauma activation criteria routinely used in addition to the six criteria of the American College of Surgeons. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:377–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nabaweesi R, Morlock L, Lule C, et al. Do prehospital criteria optimally assign injured children to the appropriate level of trauma team activation and emergency department disposition at a level I pediatric trauma center? Pediatr Surg Int. 2014;30:1097–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient: 2006. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lerner EB, Drendel AL, Falcone RA, et al. A consensus-based criterion standard definition for pediatric patients who needed the highest-level trauma team activation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:634–638. PMID 25710438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]