Abstract

Inactivation of the VHL tumor suppressor gene is the signature initiating event in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), the most common form of kidney cancer, and causes the accumulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 2α (HIF-2α). HIF-2α inhibitors are effective in some ccRCC cases, but both de novo and acquired resistance have been observed in the laboratory and in the clinic. Here, we identified synthetic lethality between decreased activity of cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6 (CDK4/6) and VHL inactivation in two species (human and Drosophila) and across diverse human ccRCC cell lines in culture and xenografts. Although HIF-2α transcriptionally induced the CDK4/6 partner cyclin D1, HIF-2α was not required for the increased CDK4/6 requirement of VHL−/− ccRCC cells. Accordingly, the antiproliferative effects of CDK4/6 inhibition were synergistic with HIF-2α inhibition in HIF-2α–dependent VHL−/− ccRCC cells and not antagonistic with HIF-2α inhibition in HIF-2α–independent cells. These findings support testing CDK4/6 inhibitors as treatments for ccRCC, alone and in combination with HIF-2α inhibitors.

INTRODUCTION

More than 400,000 patients are diagnosed with kidney cancer annually, making it one of the 10 most common forms of cancer in the developed world (1). In the United States, more than 14,500 patients die of kidney cancer each year (2). The most common type of kidney cancer is clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), which accounts for >70% of all kidney cancer cases (3).

The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene (VHL) is mutationally inactivated or hypermethylated in nearly 90% of ccRCCs, leading to the synthesis of a dysfunctional pVHL (or no pVHL at all) (4). pVHL is a part of an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets the transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor 2α (HIF-2α) for proteasomal degradation. In renal cells lacking pVHL, HIF-2α accumulates and acts as an oncogenic driver by transcriptionally activating proliferative and angiogenic genes, such as those encoding cyclin D1 (CCND1) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), respectively.

Localized ccRCC can often be managed with a partial or radical nephrectomy. Patients who recur after surgery or who present with advanced or metastatic disease are typically treated with VEGF inhibitors or immune checkpoint inhibitors as first-line therapies. Although these treatments can cause disease control in a substantial proportion of patients, few (if any) ccRCC patients are cured with these agents. Patients who do not respond to these therapies are sometimes treated with inhibitors of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), which are also palliative and not curative in this setting. Small molecules that directly target HIF-2α are promising for the treatment of pVHL-defective ccRCCs (5-7). However, the response of pVHL-defective ccRCCs to HIF-2α inhibitors appears to be heterogeneous based on preclinical and early clinical data (5-7). Therefore, new therapeutic targets are needed in ccRCC. Ideally, drugs against these targets would be active as single agents and would also lend themselves to combinations with existing agents as a means of decreasing the likelihood of acquired and de novo resistance.

One approach for developing new therapy options in ccRCC would be to identify targets that have synthetic lethal relationships with VHL loss. Synthetic lethality describes a relationship between two genes where the loss of either gene alone is tolerated, but the concurrent loss of both genes is lethal. Applying synthetic lethality to identify therapeutic targets is particularly attractive for cancer because it leverages mutations that are cancer specific, thereby creating a potential therapeutic window between cancer cells and normal host cells. Genes or proteins whose inactivation is selectively lethal in the context of VHL inactivation would theoretically be ideal targets for treating ccRCC.

A few genes have been reported to be synthetically lethal with VHL loss (8-11). A challenge is to ensure that synthetic lethal relationships are robust across models and not peculiar to, for example, an extremely narrow set of cell lines that are not truly representative of the genotype of interest. In an earlier pilot study, we identified CDK6 as being synthetic lethal with VHL in the context of two different ccRCC lines (12). Here, we performed synthetic lethal screens in isogenic Drosophila cells using RNA interference (RNAi) and isogenic human ccRCC cells using a focused chemical library. These screens reidentified inactivation of CDK4/6 as synthetic lethal with loss of VHL, suggesting that this interaction is highly robust. We found that increased HIF-2α activity was not necessary for this synthetic lethal interaction. Inhibiting CDK4/6 suppressed the proliferation of pVHL-defective ccRCCs both ex vivo and in vivo, including pVHL-defective ccRCCs that are HIF-2α independent. Moreover, CDK4/6 inhibitors enhanced the activity of a HIF-2α inhibitor in HIF-2α–dependent ccRCCs. Therefore, CDK4/6 inhibition is an attractive new avenue for treating pVHL-defective ccRCCs.

RESULTS

Loss of CDK4/6 activity selectively inhibits the fitness of VHL-deficient cells relative to VHL-proficient cells in multiple species

We screened for genes that are synthetic lethal with VHL inactivation in Drosophila melanogaster S2R+ cells and in human ccRCC cells, reasoning that a synthetic lethal relationship that was true in both of these species would likely represent a fundamental dependency that would be robust enough to withstand many differences among human cell lines and variability between patients.

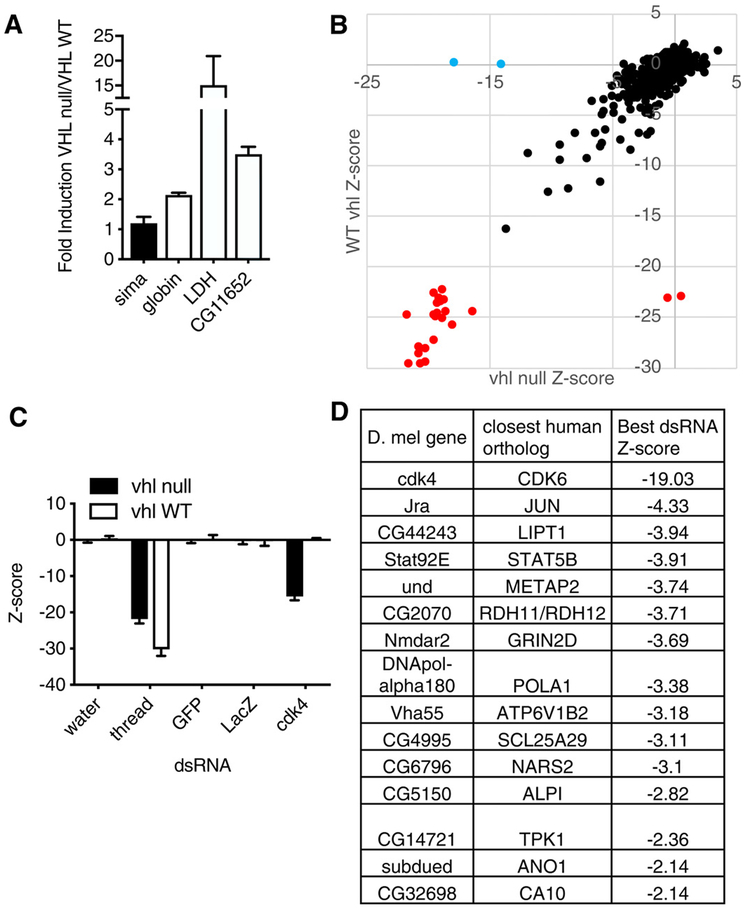

For the Drosophila screen, we first used CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing to inactivate vhl, the Drosophila ortholog of the human VHL gene, in S2R+ cells. Using single-cell cloning, we generated an S2R+ derivative that had a vhl frameshift mutation (hereafter referred to as vhl-null S2R+ cells) and confirmed that this derivative accumulated high amounts of hypoxia-inducible mRNAs (such as LDH and CG11652) driven by sima, which is the Drosophila ortholog of the human genes encoding HIF-1α and HIF-2α (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. RNAi screen for genes that are synthetically lethal with vhl inactivation in Drosophila S2R+ cells.

(A) Relative mRNA expression for sima, the D. melanogaster ortholog of the human gene encoding HIFα, and the indicated sima-responsive genes in vhl-null S2R+ cells as compared to wild-type (WT) S2R+ cells. Data are means ± SD of n = 2 independent experiments. (B) Z scores for change in viable cell number, as determined by CellTiter-Glo assays, after a 5-day incubation with dsRNAs (three dsRNAs per gene on average, 448 genes) in vhl-null S2R+ (x axis) and WT S2R+ (y axis) cells. Each dot represents the median Z score (n = 3 biological replicates) for one dsRNA. dsRNAs targeting the pan-essential Drosophila gene thread are indicated in red;those targeting cdk4 are indicated in blue. (C) Quantification of select data in (B). LacZ and GFP dsRNAs are negative controls that do not affect cell viability. Data are means ± SD of n = 3 independent experiments. (D) Top hits from (B), based on the top-scoring dsRNAs for each gene. A hit was defined as a gene targeted by a dsRNA with Z < −1.5 in at least two-thirds of replicates in EV cells and not more than one-third of VHL cells.

Next, we seeded the wild-type and vhl-null S2R+ cells into separate 384-well plates, with each well containing a unique double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) from a focused Drosophila dsRNA library targeting 448 Drosophila genes (with about three dsRNAs per gene) that are orthologous to 691 human genes (due to cases where a single ancestral ortholog in Drosophila has multiple paralogs in human) that encode protein targets of U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved drugs. In addition, the library contained dsRNAs targeting thread as a pan-lethal control and dsRNAs against GFP and LacZ as negative controls. Cells were incubated with dsRNAs for 4 days before assessment of cell number using CellTiter-Glo in three biological replicates. The data for the wild-type cells were pooled with data from six earlier replicates done with the same library. Z scores were calculated for the effects of individual dsRNAs and were used to identify dsRNAs that inhibited viability in the vhl-null cells but not in the wild-type cells (Fig. 1, B to D). The Drosophila gene cdk4, which is the ancestral ortholog of the human genes encoding CDK4 and CDK6, was the top-scoring gene fulfilling this criterion. The full dataset is available at www.flyrnai.org/screensummary (and data file S1).

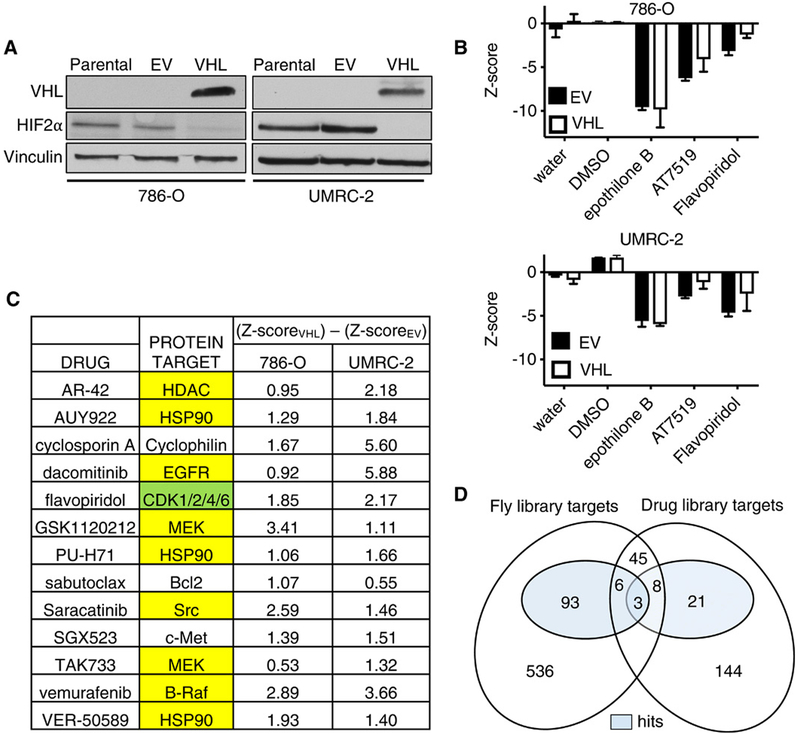

For the screen in human cells, we made 786-O and UMRC-2 human VHL−/− ccRCC cells expressing both VHL and GFP (hereafter called VHL cells) or GFP alone [hereafter called empty vector (EV) cells] using bicistronic lentiviruses that did or did not contain a VHL complementary DNA (cDNA), respectively. We confirmed that reintroduction of wild-type pVHL suppressed HIF-2α protein abundance (Fig. 2A). Next, the VHL and EV cells were seeded into separate 384-well plates, with each well containing a unique chemical from a library of ~400 annotated chemicals with known anticancer activity. These chemicals targeted proteins encoded by 227 unique genes (some chemicals had multiple or overlapping targets, and some chemicals had unknown targets). Each chemical was tested at 10 concentrations from 1 nM to 20 μM in two biological replicates. Cells were incubated with compounds for 48 hours, after which the number of green fluorescent protein (GFP)–positive objects per well was assessed as a proxy for cell number. Z scores were calculated for the effects of individual drugs using dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as a negative control and epothilone B as a pan-lethal control (Fig. 2, B and C, and data file S2). We identified a total of 63 compounds that inhibited the growth of VHL-defective 786-O and UMRC-2 cells more substantially than their VHL-reconstituted counterparts; two of these compounds (flavopiridol and AT7519) targeted proteins encoded by genes for which the Drosophila ortholog scored in our Drosophila screen (CDK2, CDK4, and CDK6) (Fig. 2D and data file S3). CDK4/6 was the only target that scored among the top 10 hits in both screens and was therefore pursued further.

Fig. 2. Small-molecule screen for chemicals that are synthetically lethal with VHL inactivation in ccRCC cell lines.

(A) Immunoblot of HIF-2α, VHL, and vinculin (loading control) abundance in parental VHL−/− 786-O and UMRC-2 cells and those stably infected with lentivirus expressing GFP and VHL (VHL) or GFP alone (EV), as indicated. Blots are representative of three biological replicates. (B) Z scores assessing the change in viable cell number, as determined by a CellTiter-Glo assay, after a 48-hour incubation with DMSO, epothilone B (123 μM), AT7519 (370 μM), or flavopiridol (41 μM) in the indicated cell lines. Data are means ± SD of n = 2 independent experiments. (C) Top-scoring drugs based on differential Z scores (VHL – EV) in 786-O and UMRC-2 cells and their putative protein targets. Yellow highlighting indicates targets that were interrogated in the Drosophila dsRNA screen (Fig. 1) but were not hits in that screen. Green highlighting indicates the targets human CDK4/6 (ortholog cdk4) and, to a lesser extent, CDK2 (ortholog cdk2) that were hits in the Drosophila dsRNA screen. (D) Venn diagram showing overlap of the human orthologs of the Drosophila dsRNA screening library and the genes encoding the protein targets of the ccRCC drug screen library. Shaded regions indicate screen hits. The data behind this diagram are in data files S1 to S3.

Pharmacological inhibition of CDK4/6 preferentially suppresses the fitness of VHL-defective ccRCC cells

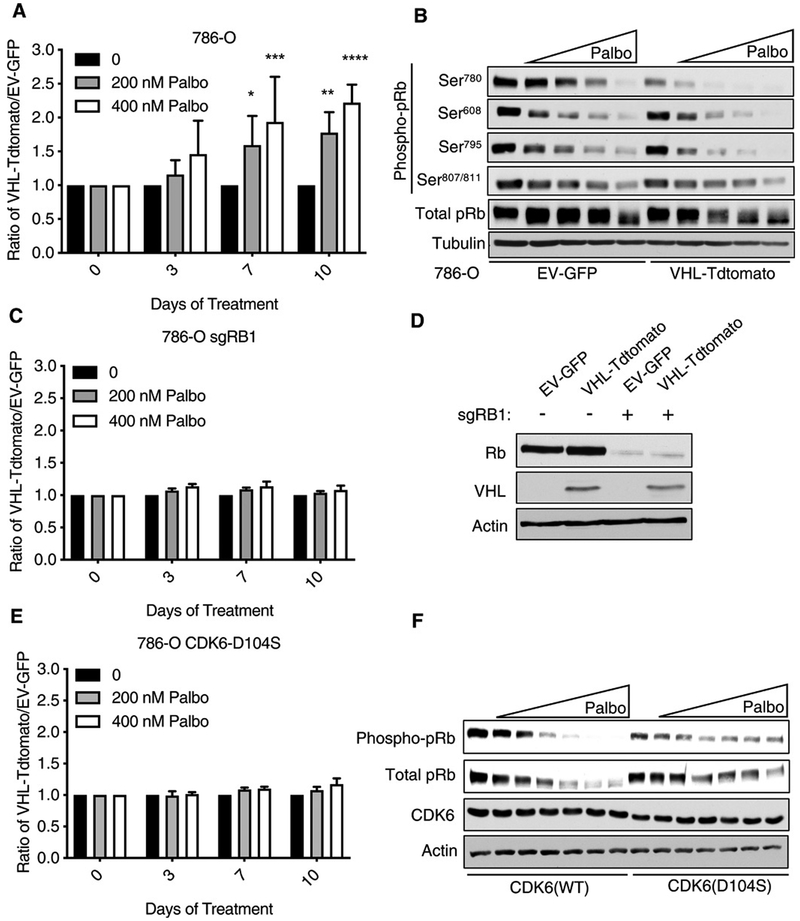

We next performed low-throughput experiments to validate the synthetic lethality observed with dual inactivation of VHL and CDK4/6. We generated Cas9-expressing 786-O cells that stably express both VHL and Tdtomato (hereafter referred to as VHL-Tdtomato) or GFP alone (EV-GFP) using bicistronic lentiviruses that did or did not contain a VHL cDNA, respectively (fig. S1A). We then mixed these cells (1:1), treated them with the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib, and monitored the composition of the cell mixture by flow cytometry. Palbociclib inhibits ccRCC cell line growth at clinically achievable concentrations (13). Palbociclib decreased the number of the EV-GFP cells relative to the VHL-Tdtomato cells (Fig. 3A), consistent with a synthetic lethal interaction between VHL loss and CDK4/6 inhibition. Such competition assays measure relative cellular fitness; a relative decrease in cell number, indicative of a relative decrease in cellular fitness, can reflect decreased cellular proliferation, viability, or both. Similar results were achieved when the fluorophores were swapped such that the VHL cells expressed GFP and the EV cells expressed Tdtomato (fig. S1B). Palbociclib did not score as a hit in our initial screen, probably because its differential effects on VHL−/− ccRCC cells compared to pVHL-proficient cells only manifested after 72 hours of treatment (Fig. 3A and data file S2).

Fig. 3. The CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib preferentially inhibits pVHL-deficient ccRCC cells in an on-target manner.

(A) Ratio of 786-O cells stably infected with a bicistronic lentivirus expressing VHL and Tdtomato (VHL-Tdtomato) to 786-O cells infected with GFP alone (EV-GFP) that had been mixed (1:1) and then treated with 0, 200, or 400 nM palbociclib for 3 to 10 days. Data are means ± SD of n = 4 independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 by two-way ANOVA. (B) Immunoblot of total and Ser780-, Ser608-, Ser795-, and Ser807/811-phosphorylated pRb in 786-O cells expressing VHL-Tdtomato or EV-GFP and treated with 100, 200, 400, or 800 nM palbociclib, as indicated by the triangle, for 24 hours. Blots are representative of three biological replicates. (C) 786-O cells that underwent CRISPR/Cas9 editing with an RB1 sgRNA and then were infected, mixed, and treated as in (A). The ratio of RB1-null VHL-Tdtomato cells to RB1-null EV-GFP cells after treatment is shown. Data are means ± SD of n = 3 independent experiments. (D) Immunoblot of Rb, VHL, and actin (loading control) abundance in 786-O cells edited with an RB1 sgRNA (as indicated, +) and infected as described in (C), but not otherwise treated. Blots are representative of three biological replicates. (E) Ratio of 786-O cells stably expressing CDK6(D104S) and either VHL-Tdtomato or EV-GFP that had been mixed and treated as described in (A). Data are means ± SD of n = 3 experiments. (F) Immunoblot of 786-O cells stably infected with lentivirus expressing either WT or mutant (D104S) CDK6 and then treated with 50, 100, 200, 400, 800, or 1600 nM palbociclib, as indicated by the triangle, for 24 hours. Blots are representative of three biological replicates.

In parallel, we treated EV-GFP and VHL-Tdtomato cells with palbociclib for 24 hours and measured changes in the phosphorylation of pRb, the canonical CDK4/6 substrate. As measured by immunoreactivity with an antibody against phosphorylated pRb and by increased electrophoretic mobility of pRb, palbociclib noticeably reduced pRb phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner both in EV-GFP and (possibly more so) in VHL-Tdtomato cells (Fig. 3B).

Unphosphorylated pRb represses the transcription factor E2F. In keeping with our immunoblot data, palbociclib decreased the expression of E2F-responsive mRNAs in both the EV-GFP and VHL-Tdtomato cells (fig. S1C). Moreover, palbociclib had similar effects on the transcriptome and on cell cycle distribution in the VHL−/− 786-O cells compared to their pVHL-restored counterparts (fig. S1, D and E). Therefore, the differential sensitivity to CDK4/6 inhibition was not due to an inability of palbociclib to effectively inhibit CDK4/6 kinase activity in the pVHL-proficient cells. Similar results were obtained in multiple other human VHL−/− ccRCC cell lines, including lines that are (A498) or are not (UMRC-2 and 769-P) HIF-2α dependent (fig. S2, A to F) (5, 14, 15). VHL expression in the absence of palbociclib had minimal effects on the fitness of the 786-O, UMRC-2, and 769-P cells for the duration of the competition assays and conferred a fitness disadvantage to the A498 cells (fig. S3).

To investigate whether the VHL-dependent effects of palbociclib on cellular fitness were on-target, we eliminated RB1 in 786-O cells using CRISPR/Cas9, infected them to stably express either VHL and Tdtomato (VHL-Tdtomato) or GFP alone (EV-GFP), and repeated our competition assays. In the absence of pRb, both the VHL-Tdtomato– and EV-GFP–expressing cells were similarly affected by palbociclib (Fig. 3, C and D). In a complementary set of experiments, we introduced a palbociclib-resistant CDK6 variant (D104S) into 786-O cells (Fig. 3, E and F). First, we confirmed that CDK6 (D104S) attenuated the pharmacodynamic effects of palbociclib on the abundance of phosphorylated pRb relative to cells expressing wild-type CDK6 (Fig. 3F). The cells expressing CDK6(D104S) were then infected to stably express either VHL and Tdtomato (VHL-Tdtomato) or GFP alone (EV-GFP) and used in our competition assays. The presence of the D104S variant, like the loss of pRb, rendered the VHL-Tdtomato and EV-GFP equally sensitive to palbociclib (Fig. 3E). The structurally unrelated CDK4/6 inhibitor abemaciclib, like palbociclib, also preferentially reduced the fitness of EV-GFP cells relative to the VHL-Tdtomato cells (fig. S2, G and H). Therefore, palbociclib’s effects in our assays were likely on-target.

Loss of CDK4 or CDK6 individually is not sufficient for synthetic lethality with VHL inactivation

In Drosophila cells, a single gene (cdk4) is the ancestral ortholog of both of the human genes CDK4 and CDK6, and the available CDK4/6 inhibitors, including palbociclib and abemaciclib, inhibit both paralogs. The observed rescue by CDK6(D104S) indicated that inhibition of CDK6 is necessary for the antifitness effects of palbociclib in VHL−/− ccRCC cells but did not address whether inhibition of CDK6 would also be sufficient for such effects. To address this, we created 786-O cells that stably express Cas9 and either VHL and Tdtomato (VHL-Tdtomato) or GFP alone (EV-GFP). We then mixed the cells (1:1), superinfected them either with a lentivirus encoding a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting CDK4 or CDK6 or with a lentivirus encoding a nontargeting control sgRNA (sgNT), and monitored the cell populations by flow cytometry (fig. S4, A and B). Although substantial knockdown was achieved (fig. S4C), loss of neither CDK4 nor CDK6 phenocopied the effects of the dual CDK4/6 inhibitors palbociclib and abemaciclib (fig. S4, A and B), suggesting that inhibition of both CDK4 and CDK6 is required (i.e., that inhibition of either alone is not sufficient) to selectively suppress the fitness of VHL−/− ccRCC cells.

The synthetic lethal relationship between CDK4/6 and VHL is not driven by HIF

To begin to understand the basis of the synthetic lethal relationship between CDK4/6 and VHL, we next created a pVHL variant in which the β domain of pVHL, which is responsible for substrate recognition, is deleted (pVHLΔB) (fig. S1A) and repeated our 786-O cell competition experiments using VHLΔB-Tdtomato cells mixed with EV-GFP cells. In this experiment, we did not observe any difference in the ratio of VHLΔB-Tdtomato:EV-GFP cells upon treatment with palbociclib (fig. S1F). These data suggest that pVHL’s ability to bind substrates through the β domain decreases dependence on CDK4/6.

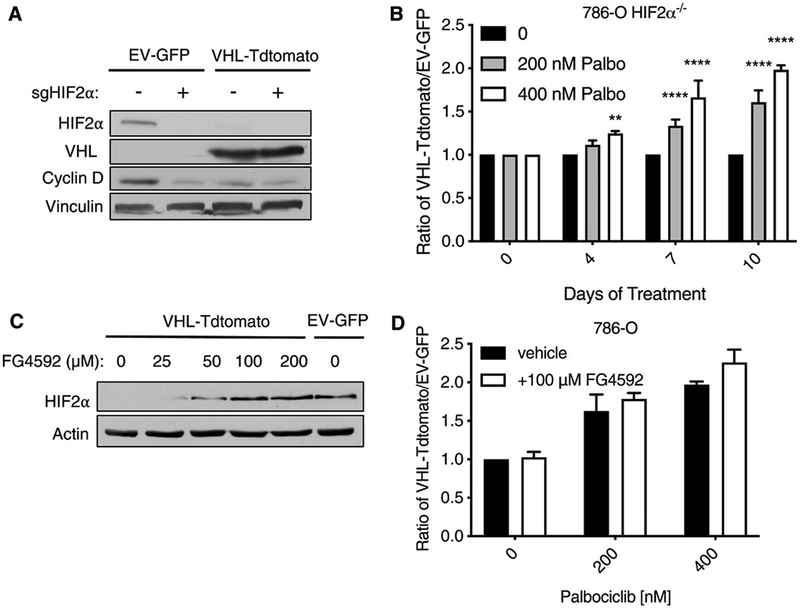

The best documented substrate of pVHL is HIFα. HIF-2α acts as an oncogenic driver in most ccRCC, and many ccRCC cell lines, including 786-O cells, express HIF-2α but not HIF-1α (16, 17). To investigate whether dysregulated HIF-2α is necessary for the increased dependence of VHL−/− ccRCC lines on CDK4/6, we eliminated HIF-2α in 786-O cells using CRISPR/Cas9 and then superinfected them with the lentiviruses expressing either VHL and Tdtomato (VHL-Tdtomato) or GFP alone (EV-GFP) (Fig. 4A). We mixed these cell types (1:1), treated the mixed population with palbociclib, and assessed the VHL-Tdtomato:EV-GFP ratio at multiple time points (Fig. 4B). Inhibition of CDK4/6 by palbociclib was synthetic lethal with VHL inactivation even in cells that lack HIF-2α, demonstrating that HIF-2α is not necessary for this interaction.

Fig. 4. Increased HIF-2α is neither necessary nor sufficient for the synthetic lethal relationship between CDK4/6 and VHL in ccRCC.

(A) Immunoblot of HIF-2α, VHL, cyclin D1, and vinculin (loading control) abundance in 786-O cells that underwent CRISPR/Cas9 editing with a HIF-2α sgRNA (as indicated, +) and were then infected to express VHL and Tdtomato (VHL-Tdtomato) or GFP alone (EV-GFP). Blots are representative of three biological replicates. (B) Ratio of HIF-2α–null VHL-Tdtomato cells to HIF-2α–null EV-GFP cells that were mixed (1:1) and then treated with 0, 200, or 400 nM palbociclib for 4 to 10 days. Data are means ± SD of n = 3 independent experiments. **P < 0.01 and ****P < 0.0001 by two-way ANOVA. (C) Immunoblot of HIF-2α and actin (loading control) abundance in 786-O cells stably expressing VHL and Tdtomato (VHL-Tdtomato) or GFP alone (EV-GFP) and treated with vehicle (0) or 25, 50, 100, or 200 μM FG4592 for 36 hours. Blots are representative of three biological replicates. (D) Ratio of VHL-Tdtomato cells to EV-GFP 786-O cells that were mixed (1:1) and then treated with 0, 200, or 400 nM palbociclib with or without 100 μM FG4592 for 10 days. Data are means ± SD of n = 3 independent experiments.

The binding of pVHL to HIF-2α requires that HIF-2α be prolyl-hydroxylated. In a complimentary set of experiments, we first treated the 786-O VHL-Tdtomato cells with increasing amounts of the prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor FG4592 and determined that 100 μM or more FG4592 induced an increase in HIF-2α abundance to an amount that was comparable to that in EV-GFP cells (Fig. 4C). We then repeated our competition assays with palbociclib in the presence or absence of 100 μM FG4592 and found that normalizing HIF-2α abundance with FG4592 did not diminish the fitness disadvantage of the EV-GFP cells relative to the VHL-Tdtomato cells (Fig. 4D). Collectively, these findings argue that HIF-2α dysregulation is not necessary for the increased CDK4/6 requirement exhibited by VHL−/− ccRCC cells.

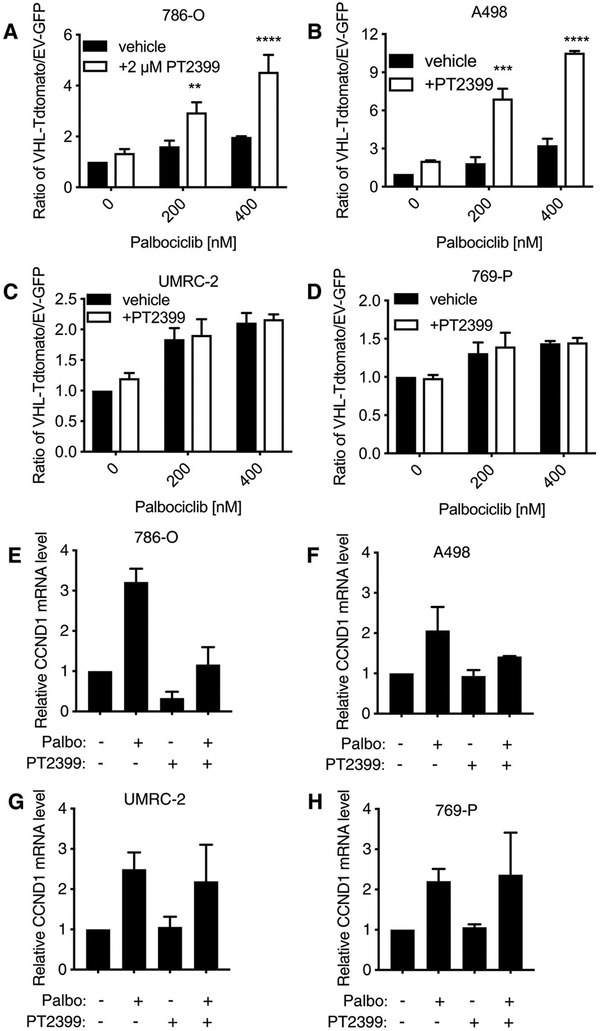

Combined inhibition of CDK4/6 and HIF-2α synergistically suppresses growth of HIF-2α–sensitive VHL-defective ccRCC cell lines

In ccRCC, HIF-2α transcriptionally induces the expression of cyclin D1, the binding partner for CDK4 and CDK6 (18-20). Because HIF-2α activity was not necessary for the preferential inhibition of VHL−/− cell proliferation by palbociclib, we predicted that combining a HIF-2α inhibitor with a CDK4/6 inhibitor would be additive or synergistic.

To test this, we mixed VHL-Tdtomato and EV-GFP cells in a 1:1 ratio, treated them with palbociclib in the presence or absence of 2 μM PT2399, and measured the ratio of VHL-Tdtomato:EV-GFP 10 days later (Fig. 5, A to D). We observed a synergistic increase in the ratio of VHL-Tdtomato:EV-GFP cells that had been treated with both palbociclib and PT2399, as compared to cells treated with palbociclib alone in the HIF-2α–dependent 786-O and A498 cell lines. Note that PT2399 monotherapy did not cause a statistically significant increase in the VHL-Tdtomato:EV-GFP ratio, consistent with earlier studies showing that 786-O cells tolerate the loss of HIF-2α in short-term cultures under high serum conditions (21, 22). Palbociclib increased the abundance of cyclin D1 at both the mRNA and proteins levels, which was blunted by adding PT2399 in the HIF-2α–dependent 786-O and A498 cell lines (Fig. 5, E to H, and fig. S5). As expected, PT2399 also decreased basal cyclin D1 mRNA and protein abundance in 786-O cells. However, for reasons that remain to be investigated, PT2399 had variable effects on basal cyclin D1 mRNA and protein abundance in the A498 cells [Fig. 5F, fig. S5, and data in (5)].

Fig. 5. Palbociclib and PT2399 synergistically suppress cell viability of VHL-null cells in PT2399-sensitive, but not PT2399-insensitive, ccRCC cell lines.

(A) Ratio of VHL-Tdtomato–expressing to EV-GFP–expressing 786-O cells that were mixed (1:1) and then treated with 0, 200, or 400 nM palbociclib with or without 2 μM PT2399 for 10 days. Data are means ± SD of n = 3 independent experiments. (B to D) As described for (A) in A498 (B), UMRC-2 (C), and 769-P (D) cells. (E) Relative mRNA expression for CCND1 in EV-GFP–expressing 786-O cells treated with 2 μM PT2399, 400 nM palbociclib, or the combination (as indicated) for 48 hours. Data are means ± SD of n = 2 independent experiments. (F to H) As described for (E) in A498 (F), UMRC-2 (G), and 769-P (H) cells. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 by two-way ANOVA.

In the HIF-2α–independent UMRC-2 and 769-P cell lines, palbociclib again led to a loss of the EV-GFP cells, but now, this loss was not enhanced further by PT2399, which correlated with a failure of PT2399 to down-regulate cyclin D1 abundance (Fig. 5, G and H, and fig. S5). Therefore, and in keeping with our genetic experiments (Fig. 4B), PT2399 enhances palbociclib’s antifitness effects on HIF-2α–dependent ccRCC cell lines and does not antagonize its effects on HIF-2α–independent ccRCC lines. HIF-2α dependence was presumed on the basis of previous studies reporting the effect of PT2399 on soft agar and orthotopic tumor growth (5), soft agar growth after CRISPR/Cas9-mediated HIF-2α elimination (5), and HIF-2α (EPAS1) sgRNA guide depletion in Project Achilles (14,15).

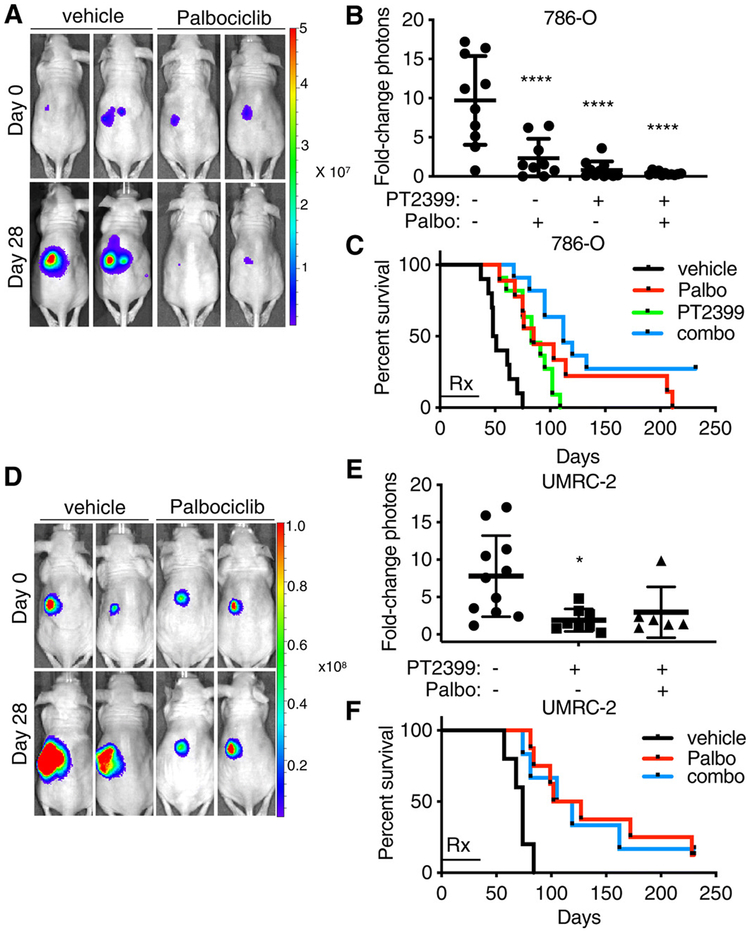

Palbociclib inhibits the growth of ccRCC orthotopic xenografts

To begin to address the in vivo relevance of our findings, we orthotopically injected 786-O (HIF-2α–dependent) and UMRC-2 (HIF-2α–independent) cells engineered to express firefly luciferase into nude mice. Two weeks later, we initiated weekly bioluminescent imaging (BLI). Mice exhibiting an increasing BLI signal for two successive weeks were then randomized to palbociclib (65 mg/kg), PT2399 (20 mg/kg), both, or vehicle(s) given daily by oral gavage for 28 days [the PT2399 arm was, however, omitted for the UMRC-2 cells because PT2399 monotherapy does not suppress the growth of these cells in such assays (5)]. A sub-maximal dose of PT2399 was used to assess whether CDK4/6 inhibition would enhance or suppress its antitumor activity. The doses of palbociclib and PT2399 used did not result in any statistically significant changes in body weight throughout the course of the study. Two mice from each treatment arm were euthanized after two doses of therapy for pharmacodynamic studies. As expected, PT2399 decreased cyclin D1 abundance, and both agents, singly and in combination, decreased both phospho-pRb and Ki-67 staining (fig. S6).

Consistent with our cell culture studies, 786-O tumor growth was significantly retarded, as determined by BLI, after 28 days of treatment with palbociclib (Fig. 6, A to C, and fig. S7, A and B). UMRC-2 tumor growth was also significantly retarded in parallel experiments (Fig. 6, D to F, and fig. S8, A and B). Similar results were obtained with mice implanted with 786-O xenografts and treated with abemaciclib (fig. S9). Similar doses of palbociclib and abemaciclib also suppressed the growth of subcutaneous tumors formed by a freshly explanted ccRCC (PDX model) (fig. S10). PT2399 monotherapy, as expected, likewise suppressed 786-O cell tumor growth, with a trend toward greater suppression with the combination (Fig. 6B and fig. S7, C and D). Abemaciclib’s ability to suppress 786-O subcutaneous xenograft growth was recently reported by others (23). The combination did not suppress UMRC-2 cell tumor growth more effectively than palbociclib alone (Fig. 6E and fig. S8C).

Fig. 6. In vivo antitumor activity of palbociclib in VHL-null ccRCC.

(A) Representative BLIs of orthotopic tumors formed by firefly luciferase-expressing 786-O cells before and after mice were treated with vehicle or palbociclib (65 mg/kg), dosed daily for 28 days by oral gavage. Images are representative of n = 10 or 9 mice, respectively. (B) Quantification of BLI at day 28 in mice described in (A) and in those treated daily by oral gavage with PT2399 (20 mg/kg) or both PT2399 (20 mg/kg) and palbociclib (65 mg/kg) (combo). Data are means ± SD overlaying the individual data points from n = 10, 9, 11, and 11, respectively. Photon counts on day 28 were normalized to those on day 0 for each mouse individually. ****P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for mice described in (B). “Rx” bar indicates duration of treatment. Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test, P < 0.0001; log-rank test for trend, P = 0.0001. (D to F) As described in (A) to (C) using UMRC-2 cells. n = 11 mice (vehicle), 8 mice (palbociclib), and 6 mice (combo). *P < 0.05 (P = 0.0112) by one-way ANOVA (F); P = 0.0012 by log-rank Mantel-Cox test (F), in which log-rank test for trend showed P > 0.05.

After the completion of therapy, the mice were monitored by weeky BLI and euthanized when they appeared morbid and distressed or lost >20% of their body weight. Palbociclib and PT2399 each individually prolonged the survival of the 786-O cell tumor–bearing mice, with a trend toward enhanced survival in the combination treatment arm (Fig. 6C and fig. S7, E to H). Three of the 11 mice treated with the combination therapy were alive and tumor free (BLI negative) 175 days after treatment ended. Palbociclib likewise enhanced the survival of the UMRC-2-bearing mice (Fig. 6F). Consistent with our cell culture studies, however, the activity of palbociclib in the UMRC-2 model was not enhanced by PT2399 (Fig. 6, E and F, and fig. S8, D to F).

DISCUSSION

We show that inactivation of the VHL tumor suppressor gene is synthetic lethal with loss of CDK4/6 activity. This relationship is robust because it can be detected in both Drosophila cells and a variety of human cancer cell lines and with both genetic CDK4/6 inhibitors and pharmacological CDK4/6 inhibitors. The antiproliferative effects of the pharmacological inhibitors were on-target because they were observed with two structurally distinct inhibitors and were rescued with a drug-resistant CDK6 point mutant or by eliminating pRb. The synthetic lethal relationship between VHL and CDK4/6 requires inactivation of both CDK4 and CDK6 and does not require HIF-2α, which is a pVHL-regulated oncogenic driver in many ccRCCs. Accordingly, in VHL-defective cells that are HIF-2α dependent, combining a HIF-2α inhibitor with a CDK4/6 inhibitor synergistically suppresses their cellular fitness ex vivo. In orthotopic tumor assays, the HIF-2α inhibitor and CDK4/6 inhibitor did not antagonize one another, suggesting that they can be combined. As expected from our ex vivo studies, adding a HIF-2α inhibitor did not enhance the activity of a CDK4/6 inhibitor against a HIF-2α–resistant line and might have enhanced the activity of the CDK4/6 inhibitor against the HIF-2α–sensitive line. Further studies are needed to confirm the latter as well as to understand the molecular basis for the HIF-2α–independent increase in CDK4/6 dependence of VHL−/− cells.

Our findings are consistent with two earlier studies that showed that palbociclib and abemaciclib have antiproliferative effects against ccRCC cells at clinically relevant concentrations, although these studies did not explore a genetic interaction between VHL and CDK4/6 (13, 23). In a previous study, we observed that VHL−/− ccRCCs were hypersensitive to a CDK6 short hairpin RNA (shRNA) compared to their VHL-proficient counterparts (12). We now suspect that this earlier result was confounded by an shRNA off-target effect, because our new findings show that CDK4 can compensate for CDK6 loss in VHL−/− ccRCC.

Exploiting synthetic lethal relationships potentially addresses two vexing problems in cancer drug discovery: (i) how to pharmacologically tackle loss-of-function mutations and (ii) how to achieve a therapeutic window between normal cells and tumor cells. The clinical utility of the synthetic lethal paradigm has now been well established by the clinical activity of poly(adenosine diphosphate–ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors in BRCA1/2-mutant breast and ovarian cancer (24-26). The VHL tumor suppressor gene is mutated in >90% of ccRCC cases (4), usually as the initiating or “truncal” event, and is thus an ideal target for the development of synthetic lethality-based therapy that will selectively kill ccRCC cells.

In estrogen receptor (ER)–positive breast cancer, ER drives transcription of the gene encoding cyclin D1, a requisite binding partner for both CDK4 and CDK6 (fig. S11). The combination of ER antagonists and CDK4/6 inhibitors is now standard of care in ER-positive breast cancer, presumably because both treatments converge on the activities of the cyclin D1/CDK4 and cyclin D1/CDK6 complexes. An analogy can be made to ccRCC, in which the VHL-regulated HIF-2α transcription factor drives transcription of cyclin D1 (fig. S11). Moreover, as shown here, pVHL loss creates a hyperdependence on CDK4/6 that is not driven by HIF-2α. Therefore, combining a HIF-2α inhibitor with a CDK4/6 inhibitor should maximize the suppression of cyclin D1/CDK4 (or CDK6) activity while still leveraging the synthetic lethality between VHL and CDK4/6. We observed synergistic suppression of cancer cell growth ex vivo when using a CDK4/6 inhibitor in combination with a HIF-2α inhibitor in cell lines in which inhibition of HIF-2α decreases cyclin D1. In cell lines where HIF-2α inhibition did not alter cyclin D1 abundance, no synergy was observed (although these cell lines remained sensitive to CDK4/6 inhibitor monotherapy). In summary, our findings suggest that VHL status, like ER status, could be a predictive biomarker for CDK4/6 inhibitors.

In an effort to increase robustness, we focused on genes that scored in both our Drosophila RNAi and human chemical screens. The use of Drosophila cells has several advantages. For example, many human paralogs are represented as a single gene in the Drosophila genome. Therefore, false negatives due to paralog compensation are less common in Drosophila RNAi screens than in typical human shRNA or sgRNA screens. Moreover, RNAi is highly efficient and titratable in Drosophila cells (27). Last, genetic interactions that can be demonstrated in both Drosophila and human cells are likely to be hard-wired rather than highly context dependent (28). However, a limitation of our study is that most of the genes we interrogated were not represented in both libraries and, hence, could not score as such. For example, MET scored in a previous shRNA screen (12) and in our chemical screen but was not represented in our Drosophila RNAi screen. c-Met inhibition might contribute to the clinical activity of the VEGF receptor inhibitor cabozantinib (29). Moreover, failure to score in Drosophila cells does not preclude a bona fide synthetic relationship in human ccRCC cells that could be clinically meaningful. For example, MAP2K1 scored in a previous shRNA screen in human cells (12) and with two pharmacological inhibitors in our study, but not in Drosophila cells. MAP2K1, encoding MEK1, is intriguing because MEK1, via ERK (extracellular signal–regulated kinase), promotes CCND1 transcription and posttranslational assembly of active cyclin D1/CDK4(or 6) complexes (30, 31). Therefore, some of the other hits from our screens could be true positives worthy of further study.

Some, but not all, kidney cancer patients respond to HIF-2α inhibitors, in keeping with the heterogeneous HIF-2α dependence observed among VHL−/− ccRCC cell lines, and those patients who do respond eventually relapse. Combining drugs that have distinct mechanisms of action is the classical way to both increase efficacy and decrease acquired and de novo resistance. These principles, together with our preclinical data to date, suggest that adding a CDK4/6 inhibitor to a HIF-2α inhibitor would improve outcomes in ccRCC patients.

Spontaneous regression of ccRCCs is well described, which led to the idea that ccRCC is an immunogenic tumor (32, 33). Moreover, immune checkpoint inhibitors are active against this disease, despite the fact that ccRCCs have much lower mutational burdens compared to melanomas and mismatch repair–deficient colon cancers (34). Several studies have demonstrated that inhibiting CDK4/6 increases the immunogenicity of cancer cells and their removal by T cells (35-37). It is therefore possible that the antitumor effects we observed with CDK4/6 inhibitors would have been greater in immunocompetent hosts, including people. One can envision eventually combining a HIF-2α inhibitor and a CDK4/6 inhibitor with the current frontline therapy of a checkpoint inhibitor and a VEGF inhibitor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and cell culture

D. melanogaster S2R+ cells were a gift from N. Perrimon’s laboratory (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). Human 786-O, 769-P, and A498 cells were originally obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. UMRC-2 cells were originally provided by B. Zbar and M. Linehan (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD) (38). S2R+ cells were maintained in Schneider’s Drosophila Media (Life Technologies, no. 21720024). 786-O, A498, and UMRC-2 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Life Technologies, no. 11965126). 769-P cells were maintained in RPMI (Life Technologies, no. 11875119). All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies, no. 10437028) and 1× penicillin-streptomycin (Life Technologies, no. 15140163). S2R+ cells were maintained at 25°C and ambient CO2, and all human cells were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. S2R+ cells were allowed to grow to confluency and were detached from culture plates by washing with spent media. All human cell lines were passaged at ≤80% confluency using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Life Technologies, no. 25200114) to dissociate cells from culture flask. Cells were tested for mycoplasma at least every 8 weeks using the MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza, no. LT07-418).

Where indicated, the following chemicals were added to the media: palbociclib (1 mM stock in water; Selleckchem.com, no. S1116), abemaciclib (10 mM stock in DMSO; a gift from Eli Lilly, no. LY2835219), FG4592 (100 mM stock in DMSO; ApexBio Technology, no. ASP4187), and PT2399 (10 mM stock in DMSO; a gift from Peloton Therapeutics, no. PT2399-16). All stock solutions were stored at −20°C.

sgRNA expression vectors for Drosophila cells

The pl018 Drosophila expression vector (28) was digested with Bbs I (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. ER1011) for 30 min at 37°C, and the linearized backbone vector was purified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) purification. sgRNA sequences were designed using the Drosophila RNAi Screening Core sgRNA design tool (www.flyrnai.org/crispr2/). Sense and antisense vhl oligonucleotides containing appropriate overhangs for ligation into the Bbs I–digested vector were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) (vhl sense, 5′-GTTCGTCTGTACTGGGTGTGCGAGC-3′; vhl antisense, 5′-AAACGCTCGCACACCCAGTACAGAC-3′).

An equimolar ratio of oligonucleotides (0.1 nmol of each sense and antisense oligonucleotide) was then annealed and phosphorylated by T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (New England Biolabs, no. M0201). Annealing and phosphorylation were carried out using a 30-min incubation at 37°C followed by a 5-min incubation at 95°C. The incubation temperature was then lowered by 5°C/min until a final temperature of 25°C was reached. The annealed phosphorylated oligonucleotides were then ligated into the Bbs I–digested pl018 by incubating for 5 min at room temperature with T7 Ligase (Enzymatics, no. L602L). A 2-μl aliquot of the ligation reaction was then transformed into chemically competent Escherichia coli cells. Plasmid DNA from ampicillin-resistant colonies was evaluated by high-resolution melt assay (HRMA) as previously described (21) and further confirmed by deep amplicon sequencing.

dsRNA screening in Drosophila cells

Screening and screen analysis were performed as previously described (39, 40). Screening library plates were obtained from the Drosophila RNAi Screening Core (DRSC) (https://fgr.hms.harvard.edu). The DRSC FDA library (Drosophila orthologs of human genes encoding targets of FDA-approved drugs) was used for screening.

Lentiviral cDNA expression vectors

The pLenti-EF1α-Cas9-FLAG-IRES-Neo vector (a gift from S. McBrayer, Kaelin Laboratory) was used to generate Cas9-expressing cells. pLenti-EF1α-Cas9-FLAG-IRES-Neo was created by PCR amplification of the cDNA from lentiCRISPR v2 (Addgene, no. 52961) encoding Cas9 with a terminal Flag epitope tag with a 5′ primer that introduced an Eco RI restriction enzyme site and a 3′ primer that introduced a Not I restriction enzyme site. This PCR product was digested with Eco RI and Not I, gel-purified, and ligated to pLenti-EF1α-IRES-Neo vector (a gift from G. Lu, Kaelin Laboratory alumnus) that was restricted with these two enzymes.

The pLX304-gate-IRES-GFP and pLX304-gate-IRES-Tdtomato destination vectors were made by V. Koduri as previously described (41). The pDONR223-VHL, pDONR223-EV, and pDONR223-VHLΔB entry clones were gifts from A. Chakraborty (Kaelin Laboratory) and were used in Gateway cloning reactions to move the EV stuffer DNA insert into the pLX304-gate-IRES-GFP destination vector and to move the VHL and VHLΔB (deletion of amino acids 91 to 121) cDNAs into the pLX304-gate-IRES-GFP and pLX304-gate-IRES-Tdtomato destination vectors by homologous recombination using LR Clonase II (Life Technologies, no. 11791100) at room temperature for 1 hour per the manufacturer’s instructions. A 3-μl aliquot of each recombination reaction was then transformed into 50-μl HB101 competent cells (Promega, no. L2011). Plasmids from ampicillin-resistant colonies were isolated by the QIAprep Spin Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, no. 27106) and validated by DNA sequencing. The EV insert is 5′-TGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTTTAAAGGAACCAATTCAGTCGACTGGATCCGGTACCGAATTCGCGGCCGCACTCGAGATATCTAGACCCAGCTTTCTTGTA-3′.

The pLenti-CDK6-D104S lentiviral vector was made by Gateway cloning the pDONR223-CDK6-D104S entry clone (a gift from N. Persky, Broad Institute) into the pLenti-EF1α-gate-3HA-PGK-Puromycin destination vector (a gift from G. Lu, Kaelin Laboratory alumnus) as described above.

The pLL3.7-EF1α-Fluc-Neo vector (a gift from M. Oser, Kaelin Laboratory) was used to generate Fluc-expressing cells. pLL3.7-EF1α-Fluc-Neo was created by PCR amplification of the firefly luciferase cDNA from Luc.Cre EV (Addgene, no. 20905) with a 5′ primer that introduced an Xba I restriction enzyme site and a 3′ primer that introduced a Not I restriction enzyme site. This PCR product was digested with Xba I and Not I, gel-purified, and ligated to a modified pLL3.7 lentiviral expression vector containing the EF1α promoter and a neomycin resistance gene (a gift from S. McBrayer, Kaelin Laboratory) that was restricted with these two enzymes.

Lentiviral sgRNA expression vectors

The pLentiGuide-Puro vector (Addgene, no. 52963) was used as a backbone for all sgRNA expression vectors with the exception of the sgRB1 expression vector, which was made with the lenti-CRISPRv2-zeo vector (a gift from S. McBrayer, Kaelin Laboratory). The lentiCRISPRv2-zeo vector was created by PCR amplification of a cDNA encoding the zeocin resistance gene from the pLenti4/V5-DEST vector (Invitrogen, no. V49810) using primers that introduced 5’ and 3′ homology arms targeted to regions of the lentiCRISPR v2 vector (Addgene, no. 52961) flanking the puromycin resistance gene cDNA. Primers corresponding to these homology arms were used in an inverse PCR with the lentiCRISPR v2 vector as a template. The zeocin resistance gene cDNA was gel-purified and used in an InFusion exchange reaction with the inverse PCR product.

pLentiGuide-Puro or lentiCRISPRv2-zeo vectors were digested with Bsm BI (New England Biolabs, no. R0580) or FastDigest Esp 3I (Life Technologies, no. FD0454) for 30 min at 37°C, and the resulting linearized vectors were gel-purified. sgRNA oligonucleotide sequences were designed using the Broad Institute Genetic Perturbation Platform Web Portal (https://portals.broadinstitute.org/gpp/public/analysis-tools/sgrna-design) with corresponding Bsm BI/Esp 3I overhangs added to facilitate ligation. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by IDT. Oligonucleotides were annealed using 0.15 nmol of each sense and antisense oligonucleotides. The oligonucleotides were heated at 95°C for 4 min and allowed to slowly cool to room temperature. Annealed oligonucleotides were then diluted 1:100 in nuclease-free water and ligated into the linearized vectors using T4 ligase in a 4-hour incubation at room temperature. A 2-μl aliquot of the ligation mixture was then transformed into 25 μl of HB101 chemically competent E. coli cells (Promega, no. L2011). Plasmids from ampicillin-resistant colonies were isolated by QIAprep Spin Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, no. 27106) and validated by DNA sequencing. The sgRNA oligonucleotides used for editing (including Bsm BI/Esp 3I overhangs) are listed in table S1.

Lentivirus production

Lentiviruses were made by Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies, no. 13778150)–based cotransfection of human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells with the lentiviral expression vector and the packaging vectors psPAX2 (Addgene, no. 12260) and pMD2.G (Addgene, no. 12259) in a 4:3:1 ratio. Supernatant was replaced after 24 hours, and virus-containing supernatant was collected after 48 and 72 hours. Virus-containing supernatant was then pooled, purified using a 45-μm filter, and frozen at −80°C in 500-μl aliquots.

Lentiviral infection

Cells were seeded into six-well plates at a density of 300,000 cells per well and allowed to attach for at least 6 hours. Spent media were discarded and replaced with 2.5 ml of fresh media, 500 μl of lentivirus, and polybrene (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, no. SC-134220) at a final concentration of 8 μg/ml (except when infecting UMRC-2 cells, when polybrene was omitted). Plates were centrifuged at 4000g for 30 min at 25°C and then incubated for 14 to 16 hours at 37°C. The supernatant was then removed and replaced with fresh media for 12 to 24 hours before the addition of selection antibiotics. Lentivirally infected 786-O cells were selected in media containing blasticidin (10 μg/ml), G418 (600 μg/ml), puromycin (2 μg/ml), or zeocin (100 μg/ml) as appropriate for the lentiviral drug resistance cassette. Lentivirally infected UMRC-2 cells were selected in media containing blasticidin (10 μg/ml) or G418 (1.8 mg/ml) as appropriate for the lentiviral drug resistance cassette. Lentivirally infected 769-P and A498 cells were selected in media containing blasticidin (10 μg/ml).

Immunoblot analysis

Cells grown in 6- or 10-cm tissue culture dishes were washed once with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). A cell lifter was then used to detach the cells in 1 ml of fresh 1× PBS. The cell suspension was transferred to a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube and centrifuged for 250g for 3 min. The supernatant was aspirated, and the cell pellet was lysed by incubation in 50 to 100 μl of EBC lysis buffer [50 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40] containing protease inhibitor cocktail (cOmplete, Roche Applied Science, no. 11836153001) and phosphatase inhibitors (PhosSTOP, Sigma, no. 04906837001) for 30 min with gentle rotation at 4°C. The lysates were then clarified by centrifugation at 17,000g for 10 min at 4°C. Whole-cell extracts were quantified using a BCA Protein Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. PI23227). Extracts were boiled for 5 min in sample buffer (3×: 6.7% SDS, 33% glycerol, 300 mM dithiothreitol, bromophenol blue). Protein concentrations were standardized using 1× sample buffer, and samples were resolved by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes using a Trans-Blot Turbo (Bio-Rad, no. 1704155). Membranes were blocked by incubation in 5% milk/tris-buffered saline (TBS)/0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T) for 1 hour at room temperature, washed three times with TBS-T (5 min per wash), and then probed with primary antibody as indicated for 1 hour (with the exception of HIF-2α, which was probed overnight). Membranes were washed three times with TBS-T (5 min per wash) and then incubated with 1:5000 horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated secondary antibody in 5% milk/TBS-T [goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. 31430) or goat anti-rabbit IgG (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. 31460)] for 1 hour at room temperature. Membranes were washed three times in TBS-T (5 min per wash). Bound antibodies were then detected with enhanced chemiluminescence Western blotting reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. WBKLS0500) or Super-Signal West Pico (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. PI34078).

The primary antibodies used were rabbit a-VHL (1:500; Cell Signaling, no. 68547), rabbit α–HIF-2α (1:1000; Bethyl, no. 118-1261), mouse α-vinculin (1:10,000; Sigma, no. V9131), rabbit α-actin (1:2000; Cell Signaling, no. 4970), rabbit α-tubulin (1:1000; Cell Signaling, no. 2146), rabbit α-CDK4 (1:1000; Cell Signaling, #12790), rabbit α-CDK6 (1:1000; Cell Signaling, no. 13331), rabbit α–phospho-pRb (Ser780) (1:5000; Cell Signaling, no. 8180), α–phospho-pRb (Ser795) (used at 1:5000; Cell Signaling, no. 9301), α–phospho-pRb (Ser608) (1:5000; Cell Signaling, no. 8147), ––phospho-pRb (Ser807/811) (1:5000; Cell Signaling, no. 8516), mouse α-pRb (used at 1:5000; Cell Signaling, no. 9309), rabbit α-NDRG1 (1:750; Cell Signaling, no. 5196), and rabbit α–cyclin D1 (1:500; Cell Signaling, no. 2978).

Small-molecule screening in human cells

Small-molecule screening was performed using the ICCB-Longwood Screening Facility (https://iccb.med.harvard.edu). GFP-expressing cells were seeded into black-sided 384-well plates at 600 cells per well using a Multidrop Combi Reagent Dispenser (Thermo Fisher Scientific, no. 5840300) in a final volume of 30 μl per well. After 24 hours, a Seiko Compound Transfer Robot was used to pin transfer 100 nl of each library plate well into the cell-containing plates. Forty-eight hours later, the GFP signal was measured as a proxy for cell number using an Acumen Laser Scanning Cytometer. The Ludwig Anti-Cancer Library of compounds was a gift from J. Brugge (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). It contains ~400 compounds in 10-point concentration curves ranging from 1 nM to 20 μM. The average Z′ value for this screening setup was 0.75 when using actinomycin D as the positive control.

GFP reporter assay for Cas9 activity

786-O cells infected with a pLenti-EF1α-Cas9-P2A-neo lentivirus were superinfected with a lentivirus expressing GFP and an sgRNA that targets GFP (pXPR_011; Addgene, #59702). Superinfected cells were selected for puromycin resistance and tested for GFP fluorescence by flow cytometry at multiple time points. 786-O cells lacking Cas9 and mock-infected cells (that were not puromycin-selected) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively, for GFP expression. Loss of GFP fluorescence over time in the superinfected cells was used to monitor CRISPR/Cas9-based editing of GFP.

Pharmacodynamic studies of palbociclib, abemaciclib, FG4592, and PT2399

Cells were seeded at 300,000 cells/10-cm dish and treated with the indicated concentrations of the specified drug for 24 hours (except in the case of PT2399, which was incubated for 48 hours). Cells were then collected, and immunoblot analysis of pharmacodynamic marker proteins was performed as described above.

Flow cytometry–based direct competition assay

Cells were infected with a pLX304-EV-IRES-GFP (EV-GFP), pLX304-VHL-IRES-Tdtomato (VHL-Tdtomato), or pLX304-VHLΔB-IRES-Tdtomato (VHLΔB-Tdtomato) lentivirus as indicated, followed by selection for antibiotic resistance with blasticidin (10 μg/ml). For competition assays with small-molecule inhibitors, EV-GFP and VHL-Tdtomato (or VHLΔB-Tdtomato) were mixed (1:1) and seeded at 300,000 cells/10-cm dish and treated with the indicated concentrations of drug or the equivalent volume of vehicle. The cells were split every 3 to 4 days. After each split, a portion of the cells were reseeded in fresh media and drug, and the remaining cells were used for flow cytometry analysis.

For competition assays using CRISPR/Cas9 editing of target genes, EV-GFP and VHL-Tdtomato cells were mixed (1:1) and seeded at 300,000 cells per well in a six-well dish and allowed to attach for at least 6 hours. The cells were then infected with viruses encoding sgRNAs against the desired target as described above. After each split, a portion of the cells were reseeded in fresh media and drug, and the remaining cells were used for flow cytometry analysis.

For flow cytometry, 10,000 cells per sample were analyzed using a BD LSRFortessa flow cytometer with the BD FACSDiva software. Living single cells were gated, and then the percentages of those cells that were GFP positive or Td-tomato positive were quantified. The ratio of Tdtomato-positive:GFP-positive cells was used as a measure of VHL+/+: VHL−/− cells and normalized to the ratio in the vehicle-treated or nontargeting sgRNA sample for each time point.

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR

Cells were homogenized using QIAshredder columns (Qiagen, no. 79654), and total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, no. 74106) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was reverse-transcribed from purified RNA using the AffinityScript qPCR cDNA Synthesis Kit (Agilent, no. 600559) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was performed in duplicate for each primer pair on each sample using LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master Mix (Roche Diagnostics, no. 04707516001) using half the volume of each reagent specified in the manufacturer’s instructions. Ct values were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method using actin 5c for reference in Drosophila cells and Beta-Actin (ACTB) for reference in human cells. The PCR primers used are listed in table S2.

Cell cycle distribution analysis

Cells were plated at ~30% confluency and treated with 0, 200, or 400 nM palbociclib for 24 hours. During the final 45 min of treatment, culture medium was supplemented with 10 μM 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU). At the completion of treatment, cells were trypsinized. Once the cells had detached from the tissue culture plate, the trypsin was neutralized with complete media and the cells were counted using a Vi-CELL XR (Beckman Coulter). One million cells were pelleted, and the supernatant was aspirated. Cells were then washed once with 1× PBS and pelleted. Cells were fixed, stained, and analyzed by flow cytometry using the FITC BrdU Flow Kit (BD Pharmingen, no. BD559619) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Histograms were created using FlowJo.

RNA sequencing

786-O EV-GFP and 786-O VHL-Tdtomato cells were treated with 400 nM palbociclib or vehicle for 72 hours and then washed once with 1× PBS. A cell lifter was then used to detach the cells in 1 ml of fresh 1× PBS. Cells were pelleted, and supernatant was aspirated. Total RNA was isolated as described for reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR).

Libraries were prepared using Roche KAPA mRNA HyperPrep sample preparation kits from 100 ng of purified total RNA according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The finished dsDNA libraries were quantified by Qubit fluorometer, Agilent TapeStation 2200, and RT-qPCR using the KAPA Biosystems library quantification kit according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Uniquely indexed libraries were pooled in equimolar ratios and sequenced on two Illumina NextSeq500 runs with single-end 75–base pair reads by the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Molecular Biology Core Facilities.

Sequenced reads were aligned to the UCSC (University of California, Santa Cruz) hg38 reference genome assembly, and gene counts were quantified using STAR (v2.5.1b) (42). Differential gene expression testing was performed by DESeq2 (v1.10.1) (43), and normalized read counts [fragments per kilobase of exon per million reads (FPKM)] were calculated using cufflinks (v2.2.1) (44). RNA sequencing analysis was performed using the VIPER snakemake pipeline (45).

ccRCC cell line orthotopic xenografts

Adherent Fluc-expressing cells grown in 15-cm tissue culture dishes were detached with trypsin, resuspended in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and centrifuged at 300g for 3 min. The cell pellets were then washed once with 1× PBS. The cells were resuspended in 1× PBS containing 2% FBS. Cell number and viability were assessed by automated cell counting on a Vi-CELL XR (Beckman Coulter). PBS (1×) containing 2% FBS was then added to achieve a cell concentration of 108/ml.

Female NCr nude mice at ~8 weeks old (Taconic, #NCRNU-F) were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine/xylazine. An incision was made in the skin, and 2 × 106 viable cells (20 μl) were injected through the fascia and into the lower pole of the renal parenchyma. The incision was closed using two to three wound clips. The mice were subcutaneously administered buprenorphine for analgesia immediately after wound closure and were allowed to regain movement and consciousness on a slide warmer. After surgery, the viability of the remaining uninjected cells was again assessed by counting on a Vi-CELL XR and was confirmed to be >98%. Mice were monitored daily for changes in weight, changes in activity, and food and water intake. Baytril was administered in drinking water for 7 days after surgery to prevent infection. Wound clips were removed 7 to 8 days after surgery.

Tumors were monitored weekly by BLI beginning 2 weeks after surgery (see below). Once the tumors showed at least two consecutive weeks of growth, the mice were randomized to receive abemaciclib (60 mg/kg), palbociclib (65 mg/kg), PT2399 (20 mg/kg), the combination of palbociclib (65 mg/kg) and PT2399 (20 mg/kg), or the corresponding vehicle(s), all by oral gavage daily for 28 days. The monotherapy mice also received the vehicle for the complementary drug used in the combination arm, and control mice received the vehicles for both combination partners. Imaging was performed by Animal Resources staff who were blinded to the treatment groups. Formulations were as follows: Abemaciclib was prepared in 1% hydroxyethyl cellulose/25 mM phosphate buffer, palbociclib was prepared in 50 mM sodium lactate buffer (pH 4.0), and PT2399 was dissolved in 10% ethanol/30% polyethylene glycol 400/60% water containing 0.5% methylcellulose and 0.5% Tween 80. Photon emission was normalized to the photon count on day 0 (the time of enrollment). Mice were sacrificed at the end of the dosing period for studies in which tumor weight was measured. For survival analysis studies, the mice were sacrificed when they lost 20% of their body weight or when they appeared moribund or distressed.

Bioluminescent imaging

Mice were administered luciferin (15 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection and anesthetized using isoflurane. Imaging began 10 min after luciferin was injected and was carried out using an IVIS camera (PerkinElmer). Bioluminescence images were analyzed using Living Image version 4.2 software (PerkinElmer).

Histology and immunohistochemistry analysis of ccRCC cell line xenografts

Tumor-bearing kidneys were harvested and immediately fixed with 10% formalin in PBS for 24 hours. Tissue was then washed and stored in 70% ethanol before being embedded in paraffin and sectioned to 4 μm thickness. Sections were baked for 30 min at 60°C to melt excess paraffin. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Immunohistochemistry staining for anti–cyclin D1 (Neomarkers, no. RM-9104), anti–Ki-67 (Biocare, no. CRM325), and phospho-Ser807/811–pRb (Cell Signaling, no. 9308) was performed on a Bond III (Leica Biosystems) with the Bond Polymer Refine Detection Kit (Leica Biosystems, #DS9800). Antigen retrieval was performed using Bond Epitope Retrieval Solution 2 for 20 min (cyclin D1 and Ki-67) or Epitope Retrieval Solution 1 for 30 min (phospho-Ser807/811–pRb). Sections were incubated for 30 min with primary antibody diluted in Bond Primary Antibody Diluent followed by incubation for 10 min with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Sections were then incubated with chromogen 3,3′-diaminobenzidine for 5 min to visualize staining. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and dehydrated in graded ethanol and xylene. Slides were digitized using a ScanScope XT (Leica Biosystems), and representative images were obtained using the Indica Labs Halo platform.

Mouse PDX xenograft model

The study was performed by Champions Oncology Inc. Tumor fragments harvested from donor animals at passage 11 were implanted in the flank region of female Athymic Nude-Foxn1nu mice (Envigo) between 7 and 9 weeks of age. Tumor size and body weight were measured twice weekly. Palbociclib (75 mg/kg) was dosed daily, and abemaciclib (60 mg/kg) was dosed twice daily for 25 days. All mice were dosed with 10 ml/kg by oral gavage.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Method of statistical analysis is indicated in the figure legends for individual experiments. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7 software (GraphPad). For comparison of two groups, t test with Welch’s correction for unequal variance was used. For comparison of multiple groups with one variable, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used with Dunnett’s post hoc testing for multiple comparisons. For comparison of multiple groups with more than one variable, two-way ANOVA was used with Dunnett’s (when comparing groups to a control group) or Tukey’s (when comparing groups to all other groups) post hoc testing for multiple comparisons. Differences were considered statistically significant if the P value was <0.05. For all figures, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. Error bars represent +SD for bar graphs and ±SD for scatter plots.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Control experiments for competition experiments done with isogenic ccRCC cell lines treated with CDK4/6 inhibitors.

Fig. S2. The CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib preferentially inhibits pVHL-deficient cells in various ccRCC cell lines.

Fig. S3. Changes in proliferation of ccRCC cells after pVHL reconstitution does not account for differential sensitivity to CDK4/6 inhibition.

Fig. S4. Individual knockdown of CDK4 or CDK6 does not differentially affect the viability of ccRCC cells based on VHL status.

Fig. S5. PT2399 attenuates palbociclib-induced up-regulation of cyclin D1 abundance in HIF-2α–dependent, but not HIF-2α–independent, cell lines.

Fig. S6. Effect of palbociclib, PT2399, and their combination on cyclin D1 and phospho-pRb abundance in vivo.

Fig. S7. Growth of ccRCC orthotopic xenografts during treatment with vehicle, palbociclib, PT2399, or their combination.

Fig. S8. Growth of HIF-2α inhibition–resistant VHL-null ccRCC orthotopic xenografts during treatment with vehicle, palbociclib, or the combination of palbociclib with PT2399.

Fig. S9. Antitumor activity of abemaciclib in VHL-null ccRCC orthotopic xenografts.

Fig. S10. Antitumor activity of palbociclib and abemaciclib in a ccRCC PDX model.

Fig. S11. Schematic of analogous signaling mechanisms in breast cancer and ccRCC.

Table S1. sgRNA oligonucleotides.

Table S2. PCR primers.

Data file S1. Results of screen for synthetic lethality with vhl inactivation using dsRNA library in Drosophila cells.

Data file S2. Results of screen for synthetic lethality with VHL inactivation using chemical library in human 786-O and UMRC-2 ccRCC cells.

Data file S3. Overlap between genes encoding targets of chemicals that scored in chemical screen and human orthologs of Drosophila genes that scored in dsRNA screen.

Acknowledgments:

We thank N. Persky and C. Johannessen for providing the entry clone for the CDK6(D104S) mutant, the DRSC for facilitation of the screening in Drosophila cells, and the members of the Kaelin Laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript and contribution of reagents. We would also like to thank E. Wallace and Peloton Therapeutics Inc. for providing the PDX model data.

Funding: H.E.N. was supported by the National Cancer Institute (F32CA220849-02) and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.W.G.K.was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the National Cancer Institute (R35CA210068) and the NIH (P50 CA101942-14). N.P. was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01GM067761). S.S. was funded by a SPORE grant from the NIH (P50CA101942). The PDX experiments were funded by Peloton Therapeutics.

Footnotes

Competing interests: H.E.N., Z.T., B.E.H., R.B.J., L.A.S., and N.P. declare that they have no competing interests. S.S. has received commercial research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb and AstraZeneca; is a consultant/advisory board member for Merck, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AACR, and NCI; and receives royalties from BioGenex. W.G.K. has financial competing interests with Lilly Pharmaceuticals (BOD), Agios Pharmaceuticals (SAB), Cedilla Therapeutics (Founder), Fibrogen (SAB), Nextech Invest (SAB), Peloton Therapeutics (SAB), Tango Therapeutics (Founder), and Tracon Pharmaceuticals (SAB).

Data and materials availability: The full dataset of the dsRNA screen in Drosophila S2R+ cells is available at www.flyrnai.org/screensummary. All other data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.World Cancer Research Fund, Kidney Cancer Statistics; www.wcrf.org.

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A, Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J. Clin 68, 7–30 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowey CL, Rathmell WK, VHL gene mutations in renal cell carcinoma: Role as a biomarker of disease outcome and drug efficacy. Curr. Oncol. Rep 11, 94–101 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaelin WG Jr., Molecular biology of kidney cancer, in Kidney Cancer Principles and Practice, Lara PN, Jonasch E, Eds. (Springer International Publishing, ed. 2, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho H, Du X, Rizzi JP, Liberzon E, Chakraborty AA, Gao W, Carvo I, Signoretti S, Bruick RK, Josey JA, Wallace EM, Kaelin WG, On-target efficacy of a HIF-2α antagonist in preclinical kidney cancer models. Nature 539, 107–111 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen W, Hill H, Christie A, Kim MS, Holloman E, Pavia-Jimenez A, Homayoun F, Ma Y, Patel N, Yell P, Hao G, Yousuf Q, Joyce A, Pedrosa I, Geiger H, Zhang H, Chang J, Gardner KH, Bruick RK, Reeves C, Hwang TH, Courtney K, Frenkel E, Sun X, Zojwalla N, Wong T, Rizzi JP, Wallace EM, Josey JA, Xie Y, Xie X-J, Kapur P, McKay RM, Brugarolas J, Targeting renal cell carcinoma with a HIF-2 antagonist. Nature 539, 112–117 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Courtney KD, Infante JR, Lam ET, Figlin RA, Rini BI, Brugarolas J, Zojwalla NJ, Lowe AM, Wang K, Wallace EM, Josey JA, Choueiri TK, Phase I dose-escalation trial of PT2385, a first-in-class hypoxia-inducible factor-2α antagonist in patients with previously treated advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol 36, 867–874 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan DA, Giaccia AJ, Targeting cancer cells by synthetic lethality: Autophagy and VHL in cancer therapeutics. Cell Cycle 7, 2987–2990 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolff NC, Pavía-Jiménez A, Tcheuyap VT, Alexander S, Vishwanath M, Christie A, Xie X-J, Williams NS, Kapur P, Posner B, McKay RM, Brugarolas J, High-throughput simultaneous screen and counterscreen identifies homoharringtonine as synthetic lethal with von Hippel-Lindau loss in renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 6, 16951–16962 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chakraborty AA, Nakamura E, Qi J, Creech A, Jaffe JD, Paulk J, Novak JS, Nagulapalli K, McBrayer SK, Cowley GS, Pineda J, Song J, Wang YE, Carr SA, Root DE, Signoretti S, Bradner JE, Kaelin WG Jr., HIF activation causes synthetic lethality between the VHL tumor suppressor and the EZH1 histone methyltransferase. Sci. Transl. Med 9, eaal5272 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson JM, Nguyen QH, Singh M, Pavesic MW, Nesterenko I, Nelson LJ, Liao AC, Razorenova OV, Rho-associated kinase 1 inhibition is synthetically lethal with von Hippel-Lindau deficiency in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Oncogene 36, 1080–1089 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bommi-Reddy A, Almeciga I, Sawyer J, Geisen C, Li W, Harlow E, Kaelin WG Jr., D. A. Grueneberg, Kinase requirements in human cells: III. Altered kinase requirements in VHL−/− cancer cells detected in a pilot synthetic lethal screen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 105, 16484–16489 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Logan JE, Mostofizadeh N, Desai AJ, VON Euw E, Conklin D, Konkankit V, Hamidi H, Eckardt M, Anderson L, Chen H-W, Ginther C, Taschereau E, Bui PH, Christensen JG, Belldegrun AS, Slamon DJ, Kabbinavar FF, PD-0332991, a potent and selective inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6, demonstrates inhibition of proliferation in renal cell carcinoma at nanomolar concentrations and molecular marker predict for sensitivity. Anticancer Res. 33, 2997–3004 (2013). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broad DepMap, DepMap Achilles 19Q1 Public (2019); figshare. Fileset. doi: 10.6084/m9.figshare.7655150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyers RM, Bryan JG, McFarland JM, Weir BA, Sizemore AE, Xu H, Dharia NV, Montgomery PG, Cowley GS, Pantel S, Goodale A, Lee Y, Ali LD, Jiang G, Lubonja R, Harrington WF, Strickland M, Wu T, Hawes DC, Zhivich VA, Wyatt MR, Kalani Z, Chang JJ, Okamoto M, Stegmaier K, Golub TR, Boehm JS, Vazquez F, Root DE, Hahn WC, Tsherniak A, Computational correction of copy number effect improves specificity of CRISPR-Cas9 essentiality screens in cancer cells. Nat. Genet 49, 1779–1784 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shen C, Beroukhim R, Schumacher SE, Zhou J, Chang M, Signoretti S, Kaelin WG Jr., Genetic and functional studies implicate HIF1α as a 14q kidney cancer suppressor gene. Cancer Discov. 1, 222–235 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maxwell PH, Wiesener MS, Chang G-W, Clifford SC, Vaux EC, Cockman ME, Wykoff CC, Pugh CW, Maher ER, Ratcliffe PJ, The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature 399, 271–275 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zatyka M, da Silva NF, Clifford SC, Morris MR, Wiesener MS, Eckardt K-U, Houlston RS, Richards FM, Latif F, Maher ER, Identification of cyclin D1 and other novel target for the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene by expression array analysis and investigation of cyclin D1 genotype as a modifier in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Cancer Res. 62, 3803–3811 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bindra RS, Vasselli JR, Stearman R, Linehan WM, Klausner RD, VHL-mediated hypoxia regulation of cyclin D1 in renal carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 62, 3014–3019 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baba M, Hirai S, Yamada-Okabe H, Hamada K, Tabuchi H, Kobayashi K, Kondo K, Yoshida M, Yamashita A, Kishida T, Nakaigawa N, Nagashima Y, Kubota Y, Yao M, Ohno S, Loss of von Hippel-Lindau protein causes cell density dependent deregulation of CyclinD1 expression through hypoxia-inducible factor. Oncogene 22, 2728–2738 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iliopoulos O, Kibel A, Gray S, Kaelin WG Jr., Tumour suppression by the human von Hippel-Lindau gene product. Nat. Med 1, 822–826 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kondo K, Kim WY, Lechpammer M, Kaelin WG Jr., Inhibition of HIF2α is sufficient to suppress pVHL-defective tumor growth. PLOS Biol. 1, e83 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Small J, Washburn E, Millington K, Zhu J, Holder SL, The addition of abemaciclib to sunitinib induces regression of renal cell carcinoma xenograft tumors. Oncotarget 8, 95116–95134 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt ANJ, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, Santarosa M, Dillon KJ, Hickson I, Knights C, Martin NMB, Jackson SP, Smith GCM, Ashworth A, Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 434, 917–921 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, Parker KM, Flower D, Lopez E, Kyle S, Meuth M, Curtin NJ, Helleday T, Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature 434, 913–917 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lord CJ, Ashworth A, PARP inhibitors: Synthetic lethality in the clinic. Science 355, 1152–1158 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Housden BE, Li Z, Kelley C, Wang Y, Hu Y, Valvezan AJ, Manning BD, Perrimon N, Improved detection of synthetic lethal interactions in Drosophila cells using variable dose analysis (VDA). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 114, E10755–E10762 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Housden BE, Valvezan AJ, Kelley C, Sopko R, Hu Y, Roesel C, Lin S, Buckner M, Tao R, Yilmazel A, Mohr SE, Manning BD, Perrimon N, Identification of potential drug targets for tuberous sclerosis complex by synthetic screens combining CRISPR-based knockouts with RNAi. Sci. Signal 8, rs9 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yakes FM, Chen J, Tan J, Yamaguchi K, Shi Y, Yu P, Qian F, Chu F, Bentzien F, Cancilla B, Orf J, You A, Laird AD, Engst S, Lee L, Lesch J, Chou Y-C, Joly AH, Cabozantinib (XL184), a novel MET and VEGFR2 inhibitor, simultaneously suppresses metastasis, angiogenesis, and tumor growth. Mol. Cancer Ther 10, 2298–2308 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sherr CJ, Beach D, Shapiro GI, Targeting CDK4 and CDK6: From discovery to therapy. Cancer Discov. 6, 353–367 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng M, Sexl V, Sherr CJ, Roussel MF, Assembly of cyclin D-dependent kinase and titration of p27Kip1 regulated by mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK1). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 95, 1091–1096 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Şenbabaoğlu Y, Gejman RS, Winer AG, Liu M, Van Allen EM, de Velasco G, Miao D, Ostrovnaya I, Drill E, Luna A, Weinhold N, Lee W, Manley BJ, Khalil DN, Kaffenberger SD, Chen Y, Danilova L, Voss MH, Coleman JA, Russo P, Reuter VE, Chan TA, Cheng EH, Scheinberg DA, Li MO, Choueiri TK, Hsieh JJ, Sander C, Hakimi AA, Tumor immune microenvironment characterization in clear cell renal cell carcinoma identifies prognostic and immunotherapeutically relevant messenger RNA signatures. Genome Biol. 17, 231 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papac RJ, Spontaneous regression of cancer: Possible mechanisms. In Vivo 12, 571–578 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santoni M, Massari F, Di Nunno V, Conti A, Cimadamore A, Scarpelli M, Montironi R, Cheng L, Battelli N, Lopez-Beltran A, Immunotherapy in renal cell carcinoma: Latest evidence and clinical implications. Drugs Context 7, 212528 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deng J, Wang ES, Jenkins RW, Li S, Dries R, Yates K, Chhabra S, Huang W, Liu H, Aref AR, Ivanova E, Paweletz CP, Bowden M, Zhou CW, Herter-Sprie GS, Sorrentino JA, Bisi JE, Lizotte PH, Merlino AA, Quinn MM, Bufe LE, Yang A, Zhang Y, Zhang H, Gao P, Chen T, Cavanaugh ME, Rode AJ, Haines E, Roberts PJ, Strum JC, Richards WG, Lorch JH, Parangi S, Gunda V, Boland GM, Bueno R, Palakurthi S, Freeman GJ, Ritz J, Haining WN, Sharpless NE, Arthanari H, Shapiro GI, Barbie DA, Gray NS, Wong KK, CDK4/6 inhibition augments antitumor immunity by enhancing T-cell activation. Cancer Discov. 8, 216–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goel S, DeCristo MJ, Watt AC, BrinJones H, Sceneay J, Li BB, Khan N, Ubellacker JM, Xie S, Metzger-Filho O, Hoog J, Ellis MJ, Ma CX, Ramm S, Krop IE, Winer EP, Roberts TM, Kim H-J, McAllister SS, Zhao JJ, CDK4/6 inhibition triggers anti-tumour immunity. Nature 548,471–475 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J, Bu X, Wang H, Zhu Y, Geng Y, Nihira NT, Tan Y, Ci Y, Wu F, Dai X, Guo J, Huang YH, Fan C, Ren S, Sun Y, Freeman GJ, Sicinski P, Wei W, Cyclin D-CDK4 kinase destabilizes PD-L1 via cullin 3-SPOP to control cancer immune surveillance. Nature 553, 91–95 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barton Grossman H, Wedemeyer G, Ren L, Human renal carcinoma: Characterization of five new cell lines. J. Surg. Oncol 28, 237–244 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Housden BE, Perrimon N, Detection of indel mutations in Drosophila by high-resolution melt analysis (HRMA). Cold Spring Harb. Protoc 10.1101/pdb.prot090795, (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Housden BE, Nicholson HE, Perrimon N, Synthetic lethality screens using RNAi in combination with CRISPR-based knockout in Drosophila cells. Bio Protoc. 7, e2119 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oser MG, Fonseca R, Chakraborty AA, Brough R, Spektor A, Jennings RB, Flaifel A, Novak JS, Gulati A, Buss E, Younger ST, McBrayer SK, Cowley GS, Bonal DM, Nguyen QD, Brulle-Soumare L, Taylor P, Cairo S, Ryan CJ, Pease EJ, Maratea K, Travers J, Root DE, Signoretti S, Pellman D, Ashton S, Lord CJ, Barry ST, Kaelin WG Jr., Cells lacking the RB1 tumor suppressor gene are hyperdependent on Aurora B kinase for survival. Cancer Discov. 9, 230–247 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dobin A, STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S, Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold AJ, Pachter L, Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol 28,511–515 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]