Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the ability of electronic health record (EHR) data extracted into a data-sharing system to accurately identify contraceptive use.

Study Design:

We compared rates of contraceptive use from electronic extraction of EHR data via a data-sharing system and manual abstraction of the EHR among 142 female patients ages 15–49 years from a family medicine clinic within a primary care practice-based research network (PBRN). Cohen’s kappa coefficient measured agreement between electronic extraction and manual abstraction.

Results:

Manual abstraction identified 62% of women as contraceptive users, whereas electronic extraction identified only 27%. Long acting reversible (LARC) methods had 96% agreement (Cohen’s kappa 0.78; confidence interval, 0.57–0.99) between electronic extraction and manual abstraction. EHR data extracted via a data-sharing system was unable to identify barrier or over-the-counter contraceptives.

Conclusions:

Electronic extraction found substantially lower overall rates of contraceptive method use, but produced more comparable LARC method use rates when compared to manual abstraction among women in this study’s primary care clinic.

Implications:

Quality metrics related to contraceptive use that rely on EHR data in this study’s data-sharing system likely under-estimated true contraceptive use.

1. Introduction:

Contraceptive use has been associated with improved reproductive health outcomes and reduced rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States [1, 2]. As a way to increase quality contraceptive care within primary care clinics, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the United States Office of Population Affairs developed federal guidelines, entitled Providing Quality Family Planning Services [3]. More recently, quality of care measures for contraceptive provision were endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF), which is a not-for-profit organization that produces standardized indicators used to measure and publicly report on health care quality [4, 5]. The contraceptive care measures include the percentage of women at risk of unintended pregnancy who are provided a most effective method of contraception (female sterilization, intrauterine device/system, implant) or moderately effective method of contraception (injectable, pill, patch, ring, diaphragm) [6, 7]. Additional measures include the percentage of women who are provided long-acting reversible methods of contraception (LARC), which includes intrauterine devices (IUDs) and implants. [4, 8].

Best methods to accurately and efficiently measure clinical performance measures in primary care practice are generally ill-defined, although it has been suggested that practice-based research Networks (PBRNs) may be valuable settings in which to explore whether clinical performance measures have been met [9–11]. PBRNs are developing ways to efficiently extract data elements from electronic health records (EHRs) for research and QI efforts with data sharing systems that link data from different EHRs into a common data model [12]. With the ability to extract large scale information from diverse primary care clinics, it is now critical to begin testing the degree to which these data can be relied upon to assess quality of contraceptive care [13]. Pursuant to our research team’s interest in determining whether primary care clinics are meeting performance measures for quality care, the accuracy of electronically extracted EHR data for assessing current use of contraception is a key variable that has not been evaluated to date. This study used a PBRN’s data sharing infrastructure to assess the strength of agreement between electronic extraction and the existing gold-standard of manual abstraction of EHR data in identifying the use of different types of contraception within a primary care practice in the northwestern U.S.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Setting

This study included patients from a single member clinic in the WWAMI region Practice and Research Network (WPRN), a PBRN of over 60 primary care clinics across 28 organizations in the five-state Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana and Idaho region. The study clinic serves approximately 2,300 women aged 18–64 years annually. Providers within the clinic include physicians, pharmacists, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, psychologists and dieticians. This clinic provides on-site LARC. Other methods, such as oral contraceptives, condoms and the 3-month injectable method, depomedroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), were ordered but not dispensed on-site by the clinic. Clinic providers were able to prescribe and administer DMPA, but patients had to pick up the prescription at an outside pharmacy and return to the clinic for administration.

2.2. Data Sources/Electronic Extraction

De-identified individual patient data were extracted from Data QUEST, an electronic data-sharing infrastructure designed for sharing EHR data for research within the WPRN, and provided to the study team at the University of Washington [14–16]. Specific data from the study site’s Centricity EHR are extracted annually by DARTNet Institute, a not-for-profit 501(c)3 organization that hosts data sets of health information for quality improvement and research, and maintains the Data QUEST infrastructure [17]. These data include an encrypted identifier (ID) demographics, diagnoses, vital signs, immunizations, selected laboratory tests and procedures, and medications. This study site’s EHR does not include a structured set of discrete fields for coding contraceptive methods. Although the EHR had some information about contraceptive methods in the “flowsheet” section, the flowsheet data are not included in the Data QUEST infrastructure because they are not considered coded.

The University of Washington study team sent a random selection of study patients (identified by encrypted study identifiers and study IDs) to an independent vendor. The vendor then provided the study patients’ medical record numbers and study identifiers (ID) directly to the WPRN clinic so that it could conduct the manual chart abstraction for these patients. The abstractor entered the manual abstraction information and the unique study ID directly into REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) [18], a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, where it could be downloaded by the research team at the University of Washington for analysis and linked via study ID to the electronic extraction data on contraceptive use. The Human Subjects Review Board of the University of Washington approved this study.

2.3. Sample

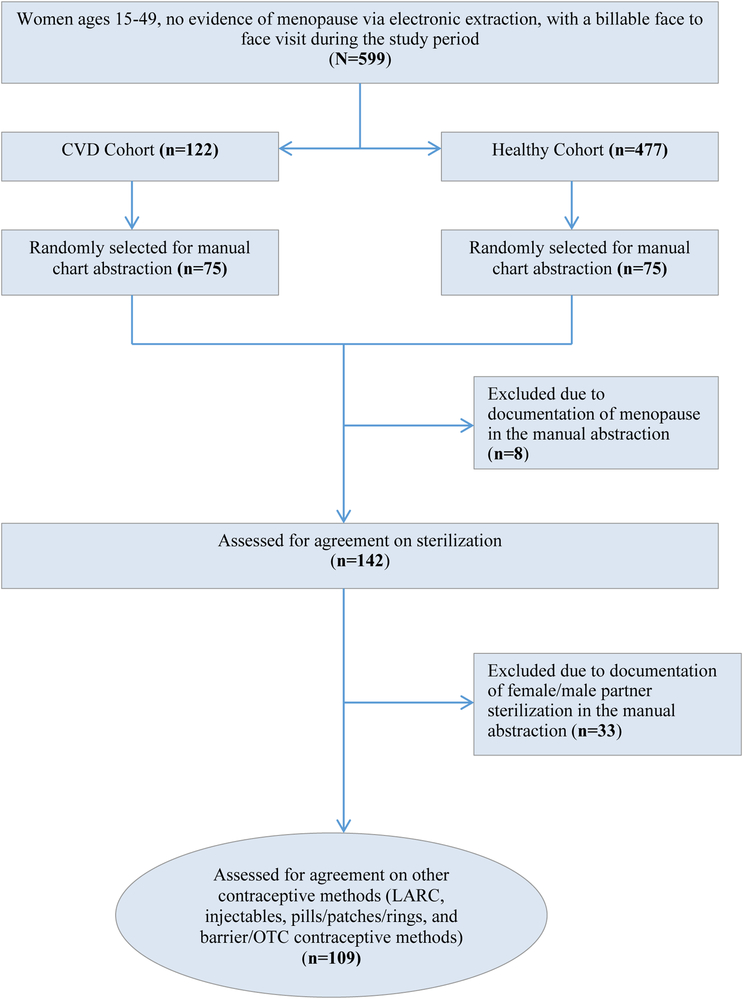

This study was part of a larger research project whose primary aim was to compare use of different contraceptive methods among women with cardiovascular-related disease (CVD) and those without chronic disease, which will be published elsewhere. Among these women, this study included female patients between the ages of 15 and 49 without International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-documented menopause who were seen in the clinic during the study period (June 1, 2011-November 30, 2012) and at least once in the three years’ prior (June 1, 2008-May 31, 2011). Among women meeting the study period inclusion criteria (n=599), we created two subgroups, with CVD and without CVD or other chronic medical conditions, related to our primary research question about adherence to contraceptive performance measures. From each of these two subgroups, we randomly selected 75 (total n=150) medical records for manual abstraction so that we could examine agreement of current contraceptive method use between extraction of EHR data into the data-sharing network and manual abstraction. During the manual abstraction, we excluded women who were menopausal (8 women total with 4 in the group with CVD, 4 in the healthy cohort). This left 142 women (71 women from each cohort) in our final sample (Figure 1). We assessed these 142 women for female sterilization and partner vasectomy. We subsequently excluded those using sterilization or partner vasectomy (n=33), leaving 109 women who were assessed for reversible contraceptive method use (LARC, injectables, pills/patches/rings, barrier and other methods).

Figure 1:

Inclusion flow for the agreement of electronic extraction and manual abstraction on contraceptive methods

2.4. Identification of Contraceptive methods

For the electronic extraction, we defined methods of contraception using drug name, diagnosis codes, and billing codes, including International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision (ICD-9), Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and Health Care Common Procedural System (HCPCS) J-codes (See Appendix A for terms, dates and methods used to identify contraceptive methods with electronic extraction and manual abstraction). National Drug Codes (NDC) were not available through the EHR. Contraceptive methods that were still listed as “active” in the EHR during our study period but had prescription duration dates outside our designated time period for that method were excluded (e.g. oral contraceptive pills for which the prescription was prescribed for 12 months, but was generated in the EHR more than a year prior). For the manual abstraction, a research coordinator familiar with the clinic’s EHR searched for these same contraceptive methods using a 20-page coding manual provided by the research team at the University of Washington. The manual was developed to reduce bias due to inter-reviewer variability during the review process [19]; it instructed the abstractor to systematically look in certain locations within the EHR (e.g., to find use of oral contraceptive pills, the abstractor was instructed to first look under the “medications tab” for a list of generic names of pills. If no method was found, then the abstractor was instructed to click on the “documents tab” and search notes for mention of contraceptive pills in the provider notes). Additionally, the abstractor used both the diagnosis, billing and procedure codes as well as contraceptive brand and generic names to identify evidence of a contraceptive method used during the study period. Abstractors looked back prior to initiation of the study period for evidence of longer acting or permanent contraceptive methods. If abstractors identified female sterilization or partner vasectomy any time prior to the end of the study period, that was considered her current contraceptive method. Otherwise, abstractors were instructed to look as far back as 10 years prior to start of study period for non-hormonal IUD methods, 5 years for hormonal IUD and 3 years for implant. Once the abstractor identified the most current contraceptive method being used by the patient, the abstractor did not look for other method use in the EHR.

2.5. Analyses

All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We used simple descriptive frequencies to examine the demographic characteristics of the study sample, and the proportion of women using each category of contraceptive method as identified by both electronic extraction and manual abstraction. We calculated whether each contraceptive method was identified by extraction only, abstraction only, or both. For each contraceptive method category, we also calculated the percent overall level of agreement between the electronic extraction and manual abstraction and the chance-adjusted agreement using Cohen’s kappa statistic calculation. Level of absolute agreement represents the proportion of patients for whom both the electronic extraction (EXT) and manual abstraction (ABST) were assigned a particular method as either “yes” (i.e., EXT yes and ABST yes) or “no” (EXT No and ABST No). The rate of absolute agreement reflects the frequency with which a contraceptive method was used. An infrequently used contraceptive method may have high levels of agreement because both manual abstraction and electronic extraction are likely to agree that the majority of individuals were not using this method.

3. Results

The sample of 142 women had a mean age of 33.9 years (Table 1), and the majority were Caucasian (88%). Half had private health care coverage (50%), and nearly all (90%) had either private or public health insurance.

Table 1:

Demographic characteristics of women included in the manual abstraction

| Characteristic | Women in the manual abstraction (n = 142) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), Mean (SD) | 33.95 (9.43) |

| Race/ethnicity1 | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 105 (88%) |

| Hispanic | 9 (8%) |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 6 (5%) |

| Insurance coverage2 | |

| Private | 70 (50%) |

| Public | 54 (37%) |

| None (Self-Pay) | 17 (12%) |

n = 120. 15% (n = 22) of patients did not have information related to race/ethnicity.

n = 141. 1% (n = 1) of patients did not have information related to insurance coverage.

Electronic extraction identified that 73% of the total cohort of 142 female patients were not using any contraceptive method, whereas manual abstraction identified roughly half as many women (38%) were not using any contraceptive method (Table 2). Percent absolute agreement between extraction and abstraction was low (62%). The percent overall agreement was relatively high at 88% (κ=0.54, 95% CI 0.35–0.73). Even though manual abstraction identified 11% of sterilized women not identified by electronic extraction, both electronic extraction and manual abstraction identified 80% of the cohort as not using sterilization, contributing to high level of agreement.

Table 2:

Frequency of documentation of different contraceptive methods by electronic extraction and abstraction method, with percent agreement between the two ascertainment methods1

| Contraceptive Method1 | Electronic extraction (n=142)* | Manual abstraction (n=142)* | Percent absolute agreement | Cohen’s kappa (κ) (95% Confidence Interval) | Proportionate distribution of assignment2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXT3 Yes, ABST3 Yes | EXT3 No, ABST3 No | EXT3 Yes, ABST3 No | EXT3 No, ABST3 Yes | ||||||

| LARC METHOD | No contraceptive method | 103 (73%) | 54 (38%) | 62% | 0.29 (0.15 – 0.43) | 0.41 | 0.21 | 0.35 | 0.03 |

| Sterilization4 | 13 (9%) | 33 (23%) | 88% | 0.54 (0.35 – 0.73) | 0.08 | 0.80 | 0.01 | 0.11 | |

| Electronic extraction (n=109)* | Manual abstraction (n=109)* | ||||||||

| Any IUD5 | 10 (9%) | 7 (6%) | |||||||

| Hormonal IUD | 6 (6%) | 7 (6%) | |||||||

| Copper IUD | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | |||||||

| Unspecified IUD | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | |||||||

| Implant | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 96% | 0.78 (0.57 – 0.99) | 0.07 | 0.89 | 0.04 | 0.00 | |

| 3-month injectable | 3 (3%) | 11 (10%) | 91% | 0.25 (−0.05 – 0.56) | 0.02 | 0.89 | 0.01 | 0.08 | |

| Pills, patches or rings | 15 (14%) | 33 (30%) | 74% | 0.28 (0.09 – 0.47) | 0.09 | 0.65 | 0.05 | 0.21 | |

| Emergency contraception | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | Not calculated | ||||||

| Other/Barrier method6 | 0 (0%) | 31 (28%) | 72% | - | 0.00 | 0.72 | 0.00 | 0.28 | |

We assessed 142 women for sterilization. We subsequently excluded those using female/male partner sterilization (n=33), leaving 109 women who were assessed for reversible contraceptive method use (LARC, injectables, pills/patches/rings, and barrier and other methods)

Contraceptive methods are not mutually exclusive. Percentages may not round to 100 due to rounding

EXT=electronic extraction; ABST=manual abstraction

Sterilization includes tubal ligation, hysteroscopic sterilization and partner vasectomy. Partner vasectomy was only able to be included if found in manual abstraction, as there is no ICD code for partner vasectomy that could be used to search electronically

IUD=intrauterine device

Other/barrier method includes all other methods found by the research assistant conducting the manual abstraction: diaphragm, cervical cap, sponge, shield, periodic abstinence, condom use, lactational amenorrhea, natural family planning, or other

Analysis of other contraceptive methods was restricted to the 109 women not sterilized. The 3-month injectable, combined hormonal methods (pills/patches/rings) and barrier methods had large differences between the proportion of women using these methods that was identified by electronic extraction and by manual abstraction. These methods’ level of agreement was higher than “no contraceptive method” because women in this cohort were using them less frequently. Similarly, among women using the injectable, manual abstraction identified more than three times the percentage (10%) compared to electronic extraction (3%). However, because injectable use in this clinic was low and both manual abstraction and electronic extraction identified similar proportions of women who were not using 3-month injectable, the overall agreement was high at 91% (κ=0.25, 95% CI 0.05–0.56). Combined hormonal methods, including pills, patches and rings, were used at greater frequency than 3-month injectable and LARC methods, with manual abstraction identifying 30% and electronic extraction identifying 14% as using combined methods. The level of agreement for combined methods was lower (74%) than other methods because manual abstraction identified a fairly large proportion of combined hormonal users (21%) that electronic extraction did not. Likewise, because barrier and other methods were not identified by electronic extraction at all, the percent agreement was also low (72%). LARC, which includes IUDs and implants, demonstrated comparable use rates when identified by manual abstraction (6%) and electronic extraction (9%), and the highest percent agreement among methods included in this study (96%) (κ=0.78, 95% CI 0.57–0.99).

4. Discussion

This study sought to evaluate the use of a primary care clinic’s EHR data that was electronically extracted into a data-sharing system for accurately assessing current use of contraceptive methods. It did so by assessing agreement in the use of contraceptive methods between electronic extraction and gold standard manual abstraction from a single clinic in a primary care PBRN. We found substantial agreement between electronic extraction and manual abstraction in identifying LARC methods, suggesting that in this setting electronic extraction of EHR data into a data-sharing system alone can be used to answer research and clinical questions about these methods, such as those related to performance measures. Agreement with other contraceptive methods was lower, raising questions about whether EHR data electronically extracted can be used to assess contraceptive performance measures. For example, manual abstraction identified 22% more pills, patch and ring method users and 28% additional barrier, other and OTC method users than those identified through our data-sharing electronic extraction; our electronic extraction was not able to identify any women who were using barrier, other or OTC contraceptive methods.

Similar to our findings, research suggests electronically extracted data from the EHR can be imprecise. A systematic review reported that 53% of medication lists within primary care practices had missing data, and problem lists were also inaccurate and varied, depending on the medical condition [20]. EHR data from integrated health systems in the United States, such as Kaiser Permanente, provide more comprehensive information because these systems address missing or incomplete data through database linkages with their integrated pharmacy system [19]. Many primary care clinics, like the clinic selected for our study, do not have linkages to pharmacy or hospital EHRs that can be used to increase data completeness.

Primary care PBRNs are important laboratories for surveillance and research for the millions of patients who are seen in primary care clinics daily. Thus, it is critical that these PBRNs have the technological ability to extract data from diverse EHR systems to provide clinical performance measures that allows them to improve healthcare quality. While this study found that electronic extraction of EHR data from this clinic into the PBRN’s Data QUEST data sharing infrastructure can be used to study LARC methods, it is unlikely to be sufficient on its own to study other contraceptive methods. Like our study, other research related to congestive heart failure, found that electronic extraction of EHR data missed important clinical data that could only be found in the provider’s clinical notes [21]. One systematic review suggests that data documentation rates can be improved with staff training and education, although more time is needed to input the data, which may not be feasible, especially within busy primary care practices [20]. Alternatively, incorporating natural language processing (NLP), a process that allows computers to understand human language, holds promise to improve future electronic extraction [22]. NLP has shown to extract medication names with comparable sensitivity and precision to manual abstraction, suggesting extraction of millions of data relatively quickly and inexpensively [23]. Because of the demonstrated limitations in complete and accurate extraction of some types of data from the EHR, researchers should assess the completeness and accuracy of their EHR data prior to its use for research or quality improvement purposes [24].

The differences our study found between extraction and abstraction are likely related to narrative data within the EHR and that in this clinical setting contraceptive methods are not documented in the EHR in a codified format. Thus, it is likely that some women in our study were using contraceptive methods that were documented in the clinic note, but not within a discrete EHR field such as non-prescribed OTC, barrier methods and methods without an ICD codes like woman whose male partner has a vasectomy. Similarly, it is possible that established patients may have received contraception from outside clinics, which did not get documented in the EHR in a codified format. LARC devices are dispensed and placed by the clinic in this study and thus the devices and procedures were billable and documented in codified format, unlike several other contraceptive methods.

EHR data can be limited because they are dependent on what data the medical providers enter into the patient charts, how current the providers keep their EHR data, and what sections of the EHR are extracted to data sharing architectures. One study limitation was our approach to the manual abstraction validation in which we excluded 23% of 142 patients from further chart review once they were identified as using sterilization as a way to reduce research assistant time. Electronic extraction only identified 9% as using sterilization, which may have skewed the true “validation” process. Despite this limitation, it seems plausible that the electronic extraction underestimated the number using sterilization because these procedures are not usually preformed in a primary care office and may not have been documented in the EHR consistently. Our study may have underestimated contraceptive method use because we excluded prescriptions that were still listed as “active” in the EHR during our study period but had prescription duration dates outside our designated time period for that method (see Appendix A). On the other hand, electronic extraction could have overestimated contraceptive method use since it identified all methods used within the study period (June 1, 2011 and November 30, 2012), whereas the manual abstraction manual instructed the abstractor to stop looking for additional contraceptive methods once the most recently prescribed method was identified in the chart, rather than going to the beginning of the study period. Generalizability also was limited because we included women from only one family medicine clinic.

In conclusion, electronic extraction of EHR data via a data-sharing system was able to accurately identify LARC methods, but not other contraceptive methods. Until there are discrete fields in the EHR that allow for, and are reliably used for comprehensive codification of contraception, NLP may remain necessary to enable accurate and efficient determination of contraceptive use when electronically extracting data from the EHR system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Rex Force, PharmD, and Loni Chacon, of the Idaho State University Department of Pharmacy Practice and Family Medicine and Alyce Sutko, MD, of the University of Washington Department of Family Medicine for their assistance with this study. The data extraction was supported by the DARTNet Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the DARTNet Institute. This project was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR000423. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest/Disclosure statement: EMG receives compensation as an instructor from Merck. The UW Department of Family Medicine receives research funding from Merck, Bayer and Teva. There are no other conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Winner B, et al. , Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med, 2012. 366(21): p. 1998–2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Frost JJ and Lindberg LD, Reasons for using contraception: perspectives of US women seeking care at specialized family planning clinics. Contraception, 2013. 87(4): p. 465–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gavin L and Moskosky S, Improving the quality of family planning services: the role of new federal recommendations. J Womens Health (Larchmt), 2014. 23(8): p. 636–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jones EJ, Eikner D, and Coleman CM, NFPRHA commentary on the contraceptive care performance measures. Contraception, 2017. 96(3): p. 145–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].National Quality Forum: About us. 2018. [cited 2018 March 17]; Available from: http://www.qualityforum.org/About_NQF/.

- [6].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Effectiveness of Family Planning Methods. 2011. [cited 2018 January 31]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/unintendedpregnancy/pdf/contraceptive_methods_508.pdf.

- [7].Curtis KM, et al. , U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep, 2016. 65(4): p. 1–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gavin L, et al. , New clinical performance measures for contraceptive care: their importance to healthcare quality. Contraception, 2017. 96(3): p. 149–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Brown AE and Pavlik VN, Patient-centered research happens in practice-based research networks. J Am Board Fam Med, 2013. 26(5): p. 481–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Fagnan LJ, et al. , Rural Clinician Evaluation of Children’s Health Care Quality Measures: An Oregon Rural Practice-based Research Network (ORPRN) Study. J Am Board Fam Med, 2015. 28(5): p. 595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Holub JL, et al. , Quality of Colonoscopy Performed in Rural Practice: Experience From the Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative and the Oregon Rural Practice-Based Research Network. J Rural Health, 2018. 34 Suppl 1: p. s75–s83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Pace WD, et al. , The DARTNet Institute: Seeking a Sustainable Support Mechanism for Electronic Data Enabled Research Networks. EGEMS (Wash DC), 2014. 2(2): p. 1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Benin AL, et al. , How good are the data? Feasible approach to validation of metrics of quality derived from an outpatient electronic health record. Am J Med Qual, 2011. 26(6): p. 441–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cole AM, et al. , Implementation of a health data-sharing infrastructure across diverse primary care organizations. J Ambul Care Manage, 2014. 37(2): p. 164–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lin CP, et al. , Developing Governance for Federated Community-based EHR Data Sharing. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc, 2014. 2014: p. 71–6. eCollection 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Stephens KA, et al. , LC Data QUEST: A Technical Architecture for Community Federated Clinical Data Sharing. AMIA Summits Transl Sci Proc, 2012. 2012: p. 57–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].DARTNet Institute: Informing Practice, Improving Care. 2015. [cited 2016 March 18]; Available from: http://www.dartnet.info/.

- [18].Harris PA, et al. , Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform, 2009. 42(2): p. 377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. Epub 2008 Sep 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lin J, et al. , Application of electronic medical record data for health outcomes research: a review of recent literature. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res, 2013. 13(2): p. 191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chan KS, Fowles JB, and Weiner JP, Review: electronic health records and the reliability and validity of quality measures: a review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev, 2010. 67(5): p. 503–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Baker DW, et al. , Automated review of electronic health records to assess quality of care for outpatients with heart failure. Ann Intern Med, 2007. 146(4): p. 270–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jha AK, The promise of electronic records: around the corner or down the road? JAMA, 2011. 306(8): p. 880–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Deleger L, et al. , Large-scale evaluation of automated clinical note de-identification and its impact on information extraction. J Am Med Inform Assoc, 2013. 20(1): p. 84–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Terry AL, et al. , Using your electronic medical record for research: a primer for avoiding pitfalls. Fam Pract, 2010. 27(1): p. 121–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.