Abstract

Background

A giant retinal tear (GRT) is a full‐thickness neurosensory retinal break extending for 90° or more in the presence of a posterior vitreous detachment.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of pars plana vitrectomy combined with scleral buckle versus pars plana vitrectomy alone for eyes with giant retinal tear.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 8), which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register; Ovid MEDLINE; Embase.com; PubMed; Latin American and Caribbean Literature on Health Sciences (LILACS); ClinicalTrials.gov; and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP). We did not use any date or language restrictions in our electronic search. We last searched the electronic databases on 16 August 2018.

Selection criteria

We included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing pars plana vitrectomy combined with scleral buckle versus pars plana vitrectomy alone for giant retinal tear regardless of age, gender, lens status (e.g. phakic or pseudophakic eyes) of the affected eye(s), or etiology of GRT among participants enrolled in these trials.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed titles and abstracts, then full‐text articles, using Covidence. Any differences in classification between the two review authors were resolved through discussion. Two review authors independently abstracted data and assessed risk of bias of included trials.

Main results

We found two RCTs in abstract format (105 participants randomized). Neither RCT was published in full. Based on the data presented in the abstracts, scleral buckling might be beneficial (relative risk of re‐attachement ranged from 3.0 to 4.4), but the findings are inconclusive due to a lack of peer reviewed publication and insufficient information for assessing risk of bias.

Authors' conclusions

We found no conclusive evidence from RCTs on which to base clinical recommendations for scleral buckle combined with pars plana vitrectomy for giant retinal tear. RCTs are clearly needed to address this evidence gap. Such trials should be randomized, and patients should be classified by giant retinal tear characteristics (extension (90º, 90º to 180º, > 180º), location (oral, anterior, posterior to equator)), proliferative vitreoretinopathy stage, and endotamponade. Analysis should include both short‐term (three months and six months) and long‐term (one year to two years) outcomes for primary retinal reattachment, mean change in best corrected visual acuity, study eyes that required second surgery for retinal reattachment, and adverse events such as elevation of intraocular pressure above 21 mmHg, choroidal detachment, cystoid macular edema, macular pucker, proliferative vitreoretinopathy, and progression of cataract in initially phakic eyes.

Plain language summary

Scleral buckling and vitrectomy in retinal detachment

What is the aim of this review? To find out the effectiveness and safety of vitrectomy combined with scleral buckle versus vitrectomy alone for eyes with giant retinal tear.

Key messages Currently no conclusive evidence is available from randomized controlled trials comparing the effectiveness and safety of using a scleral buckle in a combined procedure with vitrectomy for giant retinal tear against using vitrectomy alone.

What was studied in this review? The retina is a thin inner layer that lines the back of the eye and helps to send visual stimuli to the brain. The retina partially lines the vitreous body, a jelly‐like fluid inside the eye. A giant retinal tear occurs when the vitreous body detaches from the retina (known as a retinal detachment) and creates a hole (retinal tear) of a certain size. For people who suffer retinal detachment associated with giant retinal tear, vitrectomy is usually indicated right away to prevent permanent vision loss. Vitrectomy is a type of eye surgery in which a doctor removes the vitreous and replace it with another solution.

For people with retinal detachment who are subjected to vitrectomy, this procedure can be combined with scleral buckling. Scleral buckling is a procedure to repair a retinal detachment in which a doctor attaches a piece of silicone or a sponge onto the white of the eye (scleral). Using scleral buckling may assist attachment of the retina.

What are the main results of the review? Cochrane researchers searched for all relevant studies to answer this question and found only two conference abstracts, neither of which was published in full. Cochrane researchers also reached out to the investigators of these two studies but did not receive additional information.

People affected by giant retinal tears and retinal surgeons treating them need evidence to show whether it is useful to combine scleral buckle with vitrectomy. They need more information about the surgical procedure associated with a higher rate of retinal reattachment and reduced surgical risk. Future studies need to obtain information on outcomes for people affected by this condition, such as eye and systemic medical history, eye and retinal tear findings, vision gained from surgery, and adverse events associated with surgery.

How up‐to‐date is this review? Cochrane researchers searched for studies published up to 16 August 2018.

Background

Description of the condition

A giant retinal tear (GRT) is a full‐thickness neurosensory retinal break extending for 90° or more in the presence of a posterior vitreous detachment (Freeman 1978; Glasspool 1973; Kanski 1975; Schepens 1967; Scott 1975).

The annual incidence of GRT in the general population is estimated to be between 0.094 and 0.15 per 100,000 individuals (Ang 2010; Mitry 2011). The mean age of people with GRT ranges from 30 to 53 years (Ambresin 2003; Freeman 1981; Ghosh 2004; Goezinne 2008; Lee 2009; Norton 1969; Sirimaharaj 2005; Wolfensberger 2003). By gender, men represent more cases of GRT ‐ up to 91% of all cases (Ang 2010). GRTs are estimated to be the cause of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in 0.5% to 8.3% of cases (Chou 2007; Freeman 1978; Malbran 1990; Yorston 2002).

GRTs can be classified as primary or secondary. Primary GRTs are idiopathic, and secondary GRTs can be caused by trauma or by peripheral retinal degeneration (lattice‐related and white‐without‐pressure); hereditary vitreoretinopathies, such as Stickler's (Donoso 2003; Stickler 2001), Ehlers‐Danlos, or Marfan syndrome (Dotrelova 1997); or high myopia (> 6 diopters) (Ang 2010); or as a complication of other surgical procedures such as pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) (Shinoda 2008), refractive surgery (Navarro 2005; Ozdamar 1998; Schipper 2000; Vilaplana 1999), excessive diathermy, or photocoagulation (Schepens 1962). Most GRTs are judged to be idiopathic (55% to 66%); next in frequency are those caused by trauma (31%) (Ghosh 2004; Goezinne 2008; Holland 1977; Kanski 1975; Leaver 1981; Leaver 1984; Norton 1969; Sirimaharaj 2005; Vidaurri‐Leal 1984), high myopia (9%) (Holland 1977; Kanski 1975; Lee 2009), and hereditary vitreoretinopathies (1%) (Donoso 2003; Stickler 2001). Other rare associations have included aniridia, lens coloboma, buphthalmos, microspherophakia, retinitis pigmentosa, endogenous endophthalmitis, and acute retinal necrosis (Cahill 1998; Cooling 1980; Dowler 1995; Hovland 1968; Pal 2005).

Up to 13% of GRTs present as bilateral, non‐traumatic tears (Ambresin 2003; Ang 2012; Freeman 1978; Ghosh 2004; Goezinne 2008; Holland 1977; Kanski 1975; Leaver 1984; Lee 2009; Schepens 1962; Schepens 1967; Sirimaharaj 2005; Vidaurri‐Leal 1984). Nearly 10% of cases of GRT have been associated with an earlier GRT in the fellow eye (Ang 2012). GRTs frequently are found just posterior to the ora serrata. In cases of blunt trauma, the GRT usually appears at the superonasal quadrant associated with vitreous base avulsion, secondary to anterior‐to‐posterior compression followed by transverse distention of the globe (Schepens 1967). When GRTs are presented at the equatorial zone with posterior extensions, the slits at either end of the GRT may extend farther posteriorly in a radial fashion (Scott 1976), giving the tear's edge increased independent mobility that tends to make it invert or fold on itself.

At diagnosis, visual acuity varies from counting fingers to light perception; in some cases, visual acuity can be as good as 20/40 (Ang 2010). More than 50% of all cases of GRT are associated with retinal detachment in which the fovea is compromised (fovea‐off retinal detachment). People with GRT usually present with acute painless loss of vision that may be preceded by the perception of lights, floaters, a shadow over the field of vision, or a combination of these symptoms (Ambresin 2003; Ang 2012; Aylward 1993; Ghosh 2004; Goezinne 2008; Leaver 1984).

Surgical management of GRT can be extremely challenging because of the high incidence of scarring on retinal surfaces and in the vitreous cavity following retinal detachment, which may lead to surgical failure even following initially successful surgical repair. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) may be due to retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells from the large area of exposed RPE and blood‐borne cells from any concurrent clinical or subclinical associated vitreous hemorrhage. RPE cells migrate toward the vitreous cavity and proliferate into the epiretinal and subretinal space with an increase in cytokine production followed by formation of cellular membranes, which may grow and contract (Duquesne 1996; Girard 1994; Kon 1999; Leaver 1984; Malbran 1990; Miller 1986; Ryan 1985; Tseng 2004; Weller 1990; Wiedemann 1988; Yeung 2008; Yoshino 1989). Proliferative vitreoretinopathy has been estimated to cause up to 49% of retinal redetachment of a GRT (Ghosh 2004; Kertes 1997; Malbran 1990; Rofail 2005; Scott 2002).

A long‐standing debate has surrounded the role of the scleral buckle procedure combined with PPV in the surgical management of GRT. Management includes performing complete vitrectomy, unfolding the retinal flap, sealing the tear with chorioretinal adhesion, and providing intraocular tamponade (Adelman 2013; Chang 1989; Kreiger 1992).

The role of scleral buckling is controversial. Some surgeons consider the procedure beneficial for facilitating attachment of the retina because it reduces early and late vitreoretinal traction, supports areas where unrecognized retinal breaks developed after surgery, and counteracts late traction on the peripheral retina from contracture of residual vitreous gel. Some surgeons believe that scleral buckling complicates closure of a GRT by causing gaping of retinal tissue, producing redundant retinal folds, and being a real cause of posterior retinal slippage due to its role in changing ocular contour and scleral shortening relative to retina. Alternatively, some surgeons consider performing a scleral buckle only for recurrent cases of GRT. This remains the topic of an ongoing discussion among experienced surgeons (Al‐Khairi 2008; Hoffman 1986; May 1992; Scott 2002).

Description of the intervention

One of two surgical interventions is used to repair GRTs: PPV combined with scleral buckle or PPV alone.

PPV is a surgical procedure that involves removal of the vitreous gel. Perfluorocarbon liquids are then used to unfold the retina and provide countertraction and retinal stabilization during removal of fibrous membranes adherent to the retina (epiretinal and subretinal membranes) (Machemer 1972). Once retinal reattachment is complete, the surgeon performs two or three rows of endophotocoagulation under air or a perfluorocarbon liquid bubble at the border of the tear. At the end of the PPV, silicone oil or a gas bubble is usually injected into the eye to provide retinal tamponade, while the retina heals and reattaches (Chang 1989; Machemer 1972; Mathis 1992).

Scleral buckle procedures involve the use of an explant made of silicon sponge or a solid silicone band sutured to the sclera circumferentially around the equator of the eye (Wilkinson 1999; Williams 2006).

Scleral buckle and PPV may be combined for treatment of GRTs (Goezinne 2008; Holland 1977; Weichel 2006).

How the intervention might work

In PPV, the vitreous body and the vitreous base are removed; intraoperatively, perfluorocarbon liquids (perfluoro n‐octano) are used to unfold the retina. Fibrous membranes are removed to relieve the vitreoretinal traction, while the retina flattens. Once the retina is flattened, the tear is sealed by chorioretinal adhesion induced by endophotocoagulation. At completion of the procedure, the vitreous cavity is filed with silicone oil or a gas bubble to promote adhesion between the retina and the RPE (Ambresin 2003; Freeman 1981; Leaver 1981; Leaver 1984; Sirimaharaj 2005).

The scleral buckle creates an indentation in the wall of the eye, which brings the detached retina closer to the eye wall and relieves the vitreoretinal traction by supporting the vitreous base. Thus, the combined procedure may hasten healing and result in better postsurgery anatomical and visual outcomes (Goezinne 2008; Holland 1977; Weichel 2006).

Why it is important to do this review

GRTs are an uncommon cause of retinal detachment. Even though primary and final retinal reattachment rates are achieved in up to 90% of cases (Chang 1989; Goezinne 2008), visual recovery may be limited. Because of the extensive area of RPE exposed, GRTs usually progress rapidly to proliferative vitreoretinopathy, leading to surgical failure or reduced vision. Surgical management of a GRT may be challenging; recurrent retinal detachment secondary to proliferative vitreoretinopathy occurs in up to 40% of cases (Ghosh 2004; Kertes 1997; Malbran 1990; Rofail 2005; Scott 2002).

GRT currently is managed with PPV; the use of adjunctive scleral buckling is debated because it is unclear whether applying a scleral buckle provides an anatomical or visual advantage. Although general consensus favors the combined procedure in cases of GRT with proliferative vitreoretinopathy, some surgeons choose not to use scleral buckling because it may distort the shape of the eye and enhance risks of slippage of the retina posteriorly, secondary axial lengthening, gaping of retinal tissue, redundant retinal folds, and fish mouthing (Chang 1989; Machemer 1972; Mathis 1992). Other surgeons favor the combined procedure because it is thought to reduce early and late traction within the vitreous base, thus decreasing the risk of recurrent retinal detachment (Goezinne 2008; Holland 1977; Weichel 2006).

It is therefore important to review the current evidence to compare PPV alone versus combined with scleral buckling to determine the better option that results in higher rates of surgery success, while reducing the number of secondary surgeries and the occurrence of adverse events. A separate Cochrane Review has been published about interventions for prevention of GRT in the fellow eye because people with unilateral GRT are at high risk of developing retinal tears and retinal detachment in the other eye (Ang 2012).

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of pars plana vitrectomy combined with scleral buckle versus pars plana vitrectomy alone for eyes with giant retinal tear.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs), irrespective of their publication status or language.

Types of participants

We included trials that enrolled participants with either unilateral or bilateral GRT. We define GRT as a full‐thickness retinal break extending circumferentially for 90° or greater in the presence of a posterior vitreous detachment, or as defined by eligible trials. We included trials with more than three months of follow‐up, regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, lens status (e.g. phakic or pseudophakic eyes) of the affected eye(s), or etiology of GRT among participants enrolled in the trials.

Types of interventions

We included trials that compared PPV combined with scleral buckle versus PPV alone for GRT.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Primary surgical success defined as primary retinal reattachment, or as defined by trial investigators, after initial surgery. We considered outcomes reported at different time points (less than six months, six to 12 months, and more than 12 months' follow‐up)

Secondary outcomes

Mean change in best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) in logMAR units from baseline to last follow‐up visit, reported at different time points (less than six months, six to 12 months, and more than 12 months' follow‐up)

Proportion of study eyes that required a second surgery for retinal reattachment after the initial surgery. We planned to analyze second surgeries reported from day one up to the last reported follow‐up visit after surgery

Adverse events

We planned to investigate the proportion of study eyes with adverse events after surgeries, such as retinal detachment recurrence, elevation of intraocular pressure above 21 mmHg, choroidal detachment, cystoid macular edema, macular pucker, proliferative vitreoretinopathy, or progression of cataract in initially phakic eyes, and any other adverse events reported by included trials at any time from day one up to the last reported follow‐up visit after surgery.

Economic outcome

It was not possible to determine differences in costs between treatment groups because of missing data.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Eyes and Vision Information Specialist searched the following electronic databases for RCTs and controlled clinical trials. There were no restrictions on language or year of publication. Electronic databases were last searched on 16 August 2018.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 8) (which contains the Cochrane Eyes and Vision Trials Register), in the Cochrane Library (searched 16 August 2018) (Appendix 1).

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 16 August 2018) (Appendix 2).

Embase.com (1947 to 16 August 2018) (Appendix 3).

PubMed (1948 to 16 August 2018) (Appendix 4).

Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information Database (LILACS) (1982 to 16 August 2018) (Appendix 5).

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 16 August 2018) (Appendix 6).

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp; searched 16 August 2018) (Appendix 7).

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of reports from trials we identified, to look for additional trials. We did not conduct manual searches of conference proceedings or abstracts specifically for this review. We used the Science Citation Index to find studies that cited the identified trials (last searched 21 July 2019).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed the titles and abstracts of all records identified by electronic and manual searches. Each review author labeled the study referenced in each citation as "definitely relevant," "unsure," or "definitely not relevant." We excluded from the review trials classified as "definitely not relevant." Two review authors independently reassessed the full text of trials labeled as "unsure" and "definitely relevant" according to the inclusion criteria for this review and classified them as "definitely include" or "definitely exclude." We assessed trials labeled as "definitely include" for methodological quality. We resolved any differences in classification between the two review authors through discussion at both stages of the screening process. We documented excluded trials after review of the full‐text reports and provided reasons for exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors extracted data independently using Covidence. Two review authors reached consensus before entering data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) (Review Manager 2014). We collected the following information from the included trials: study methods, participants, interventions, and outcomes. We contacted the authors of two conference abstracts that were not published, to ask for more information about the studies; we did not receive any data after two weeks.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed each included trial for risks of bias according to the guidelines provided in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2017). We considered the following criteria when assessing bias.

Random sequence generation: we planned to assess the method used to generate the allocation sequence generation and the allocation concealment method used before randomization.

Masking (blinding) of participants and outcome assessors: we planned to assess the methods used to mask participants and outcome assessors.

Incomplete outcome data: we planned to assess exclusions after randomization, rates of follow‐up, reasons for losses to follow‐up, and deviations from intention‐to‐treat analysis of outcomes.

Selective outcome reporting: we planned to assess selective outcome reporting by comparing protocols and other design documents with trial reports and by noting outcomes that were measured but not reported.

Other bias: we planned to assess other sources of bias, for example, industry funding.

We graded each trial on the basis of the above bias criteria as:

high risk of bias: when plausible bias seriously weakens the study results;

low risk of bias: when plausible bias is unlikely to alter the study results; or

unclear risk of bias: when plausible bias raises some doubt about the study results.

For all trials graded as "unclear risk of bias" because of doubt about the study on methods, results, or missing data, we contacted the investigators of the RCTs to request additional information. We assessed risks of bias of using available information if we did not hear back from trial investigators in two weeks, and we noted lack of response from trial investigators. We resolved any disagreements between review authors regarding bias assessment through discussion until we reached consensus.

Measures of treatment effect

We estimated the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) after surgery (PPV combined with scleral buckle vs PPV alone) for the following dichotomous outcomes with information obtained from the included studies.

Primary surgical success.

Second surgery for retinal reattachment.

Development of adverse events such as retinal detachment recurrence, elevation of intraocular pressure above 21 mmHg, choroidal detachment, cystoid macular edema, macular pucker, proliferative vitreoretinopathy, progression of cataract in initially phakic eyes, and any other adverse events reported by included trials at any time from day one up to the last reported follow‐up visit after surgery.

We planned to estimate means and standard deviations of absolute and relative change after surgery (PPV combined with scleral buckle vs PPV alone) for the following outcomes.

Absolute and relative change in visual acuity in logMAR from baseline to follow‐up visits in both surgery groups.

Absolute and relative change in retinal detachment in GRT from baseline to follow‐up visits in both surgery groups.

To avoid the phenomenon of regression to the mean for the absolute change, we planned to perform an analysis of covariance where the change was defined relative to the value of "y" at baseline.

Unit of analysis issues

For this review, the unit of analysis was the eye; all statistical estimations included within‐individual correlation among analyses. We planned to use covariance and linear regression for repeated measures.

For trials that enrolled both eyes of participants with bilateral GRT and used a paired‐eye design in which one eye was randomized to receive PPV alone and the fellow eye received the combined procedure, the unit of analysis was the eye. If enough data were provided for paired‐eye design trials such as covariance or paired tabulation, we planned to use a paired‐sample t‐test or a McNemar test to assess differences between paired‐eye outcomes.

Dealing with missing data

If trials were not analyzed via an intention‐to‐treat approach, or when data were unclear or missing, we planned to contact trial authors for clarification and further information. We allowed two weeks for trial authors to respond, and if we did not receive a response, we used available information.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to evaluate the heterogeneity of trials by using Cochrane Q and I² tests. The Q value has a Chi² distribution with the null hypothesis that the likelihood ratio is the same for all studies. The I² test evaluates variability of effect. We planned to consider values higher than 50% as evidence of substantial heterogeneity (Deeks 2017). If substantial heterogeneity or inconsistency was present, we did not report the pooled analysis; we planned to report instead a narrative summary of the results.

We expected methodological and clinical sources of heterogeneity from differences in participant characteristics, types or timing of outcome measurements, and intervention characteristics such as surgical methods used, including number of surgeons, PPV gauge number, scleral buckle type (silicon band/silicon sponge), preoperative lens status (phakic, pseudophakic, aphakic), and vitreous substitute endotamponade (gas/silicon oil).

Assessment of reporting biases

When possible, we planned to obtain published protocols or methods papers to compare intended outcomes versus reported outcomes. When we identified 10 or more RCTs, we planned to use funnel plots to judge asymmetry that may indicate publication bias in one or more reported studies in a meta‐analysis.

Data synthesis

We planned to perform data analysis according to the guidelines set forth in Chapter 9 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventios (Deeks 2017). We planned to compare PPV combined with scleral buckle versus PPV alone for GRT. When the number of trials was less than three, we planned to use a fixed‐effect model; otherwise we planned to to use a random‐effects model. If we found evidence of substantial heterogeneity, or if we noted large diversity in participant characteristics and trial methods, we planned to present only a narrative summary of the results. We planned to perform a meta‐analysis for all outcomes under Types of outcome measures.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to investigate potential explanations for clinical or statistical heterogeneity by comparing outcomes within subgroups to compare the relative effects of PPV combined with scleral buckle and PPV alone by type of tamponade used in surgery (silicon oil or gas), participant age, retinal tear etiology, duration of symptoms, grades or quadrants of retinal tear extension (90° to 180° or one or two quadrants, 180° to 270° or two or three quadrants, and 270° to 360° or three or four quadrants), lens status (phakic, pseudophakic, or aphakic), and presence of proliferative vitreoretinopathy (grade C) according to the Retinal Society classification (Machemer 1991), whenever sufficient data were reported.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to examine the impact of excluding trials with high risk of bias in all of the following domains ‐ incomplete data, unpublished data, and industry funding ‐ to assess the robustness of estimates with respect to these factors.

"Summary of findings" table

We planned to produce a "Summary of findings" table for the following outcomes: primary surgical success, mean change in BCVA from baseline measured in logMAR units, proportion of study eyes that required a second surgery for retinal reattachment, adverse events, and economic outcomes. We planned to use the GRADE approach to assess the quality of the evidence (Guyatt 2011). Given the certainty, we planned to consider limitations of any included studies, consistency of effect, imprecision of results, indirectness of results, and publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

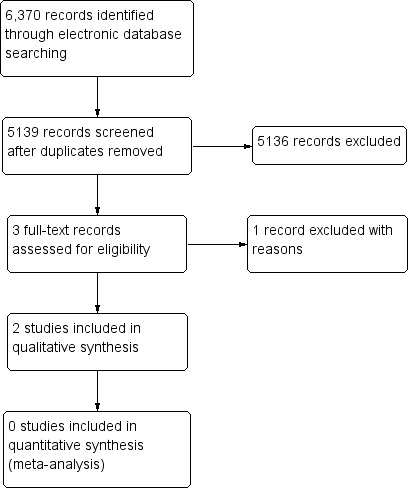

Through electronic searches, we retrieved a total of 5139 unique records, of which 5136 were excluded after review of titles and abstracts. We further excluded one full‐text report because the the population did not meet the eligibility criteria. We included the remaining two conference abstracts in the review (Figure 1). We contacted study authors for more information about the two included studies described in the conference abstracts; we did not obtain any data from investigators after waiting for two weeks.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

The Characteristics of included studies table lists the two included studies in abstract form. In Lewis 1998, 84 eyes were randomized, with a mean follow‐up of 18 months. In Sharma 2000, 21 eyes were randomized, with a follow‐up of 6 months.

Excluded studies

The Characteristics of excluded studies table lists one excluded study along with reasons for exclusion (Falkner Radler 2015).

Risk of bias in included studies

We found only two trials published in abstract form that were eligible for inclusion in the review and for risk of bias assessment.

Allocation

We assessed the two trials as having unclear risk of selection bias because insufficient information was provided in the abstracts.

Blinding

We assessed the two trials as having unclear risk of performance bias and detection bias because insufficient information was provided in the abstracts.

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed the two trials as having unclear risk of attrition bias because insufficient information was provided in the abstracts.

Selective reporting

We assessed the two trials as having unclear risk of reporting bias because we were not able to identify protocols or full reports for these studies.

Other potential sources of bias

We assessed the two trials as having unclear risk of other sources of bias because insufficient information was provided in the abstracts.

Effects of interventions

We foun two RCTs in abstract form (105 participants randomized). Neither RCT was published in full, and insufficient information was available to assess the effectiveness of the interventions.

In Lewis 1998, retinal re‐detachment occurred in 21% of eyes with scleral buckle and in 7% of eyes without scleral buckle (RR 3.0, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.9 to 10.3). Reoperations were performed in 50% of eyes with and in 14% of eyes without scleral buckle. In Sharma 2000, eight of ten eyes had an attached retina (80%) at six months’ follow‐up in the buckle group, as compared to two of 11 eyes (22%) in the no buckle group (RR 4.4, 95% CI 1.2 to 16.0).

Discussion

Summary of main results

We conducted a search of several electronic literature databases to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that evaluated the role of pars plana vitrectomy combined with scleral buckle versus pars plana vitrectomy in the management of giant retinal tear. Despite using a sensitive search strategy, we identified only two conference abstracts without full‐text reports. Based on these two abstracts, scleral buckling might be beneficial, but the findings are inconclusive due to a lack of peer reviewed publication and insufficient information for assessing risk of bias.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Most of the published literature on this topic is limited to retrospective reports or case series (Ambresin 2003; Dabour 2014; Ghosh 2004; Goezinne 2008; Kumar 2018; Lee 2009; Scott 2002; Rofail 2005). Any attempt to draw conclusions through non‐randomized studies may be misleading. This lack of information demonstrates the importance of publishing the two RCTs reported in the abstract form and conducting properly powered multicenter RCTs on this topic.

Quality of the evidence

Giant retinal tear (GRT) remains an uncommon vitreoretinal pathology; therefore the surgical approach may be challenging for many retinal surgeons. Most published research data have been derived from non‐randomized studies, with primary retinal reattachment ranging from 71.7% up to 94.4% (Ambresin 2003; Batman 1999; Ghosh 2004; Goezinne 2008; Kumar 2018; Lee 2009; Scott 2002; Verstraeten 1995). We found two conference abstracts describing two RCTs without full‐text reports (Lewis 1998; Sharma 2000). Unfortunately, the quality of data and the results cannot be analyzed because of missing information; therefore data should be interpreted cautiously. In summary, it is unclear to date if combining pars plana vitrectomy with scleral buckle offers any advantage in treating giant retinal tears.

Potential biases in the review process

We seek to minimize potential risk of bias by conducting an electronic search of clinical trials with two independent review authors and according to the methods recommended by Cochrane.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Our findings are consistent with those described in a published review (Shunmugam 2014). Both our review and Shunmugam 2014 described the difficulty of determining if using a scleral buckle in a combined procedure with pars plana vitrectomy for giant retinal tear can modify outcomes in GRT surgery. Since evidence from RCTs is lacking, it is difficult to reach conclusions from non‐randomized studies for which patient characteristics and the comparability of surgical techniques cannot be established.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Due to lack of evidence from RCTs, the ophthalmologist may have difficulty when making a decision to obtain better anatomical results and to reduce surgical failure outcomes. It is possible that knowing the characteristics of patients, as well as the characteristics of the giant retinal tear extension, location, and etiology, as well as the time that elapses during surgery and the presence of proliferative vitreoretinopathy, could lead to a better understanding of the impact of scleral buckling combined with vitrectomy. Data from retrospective and non‐randomized prospective studies are not appropriate for these purposes.

Implications for research.

Well‐designed RCTs are clearly needed to evaluate the advantages of pars plana vitrectomy combined with scleral buckle versus pars plana vitrectomy for giant retinal tear. Such trials should be randomized, and patients should be classified by giant retinal tear characteristics (extension (90º, 90º to 180º, > 180º), location (oral, anterior, posterior to equator), proliferative vitreoretinopathy stage, and endotamponade. Analysis should include both short‐term (three months and six months) and long‐term (one year to two years) outcomes for primary retinal reattachment, mean change in best corrected visual acuity, study eyes that required second surgery for retinal reattachment, and adverse events such as elevation of intraocular pressure above 21 mmHg, choroidal detachment, cystoid macular edema, macular pucker, proliferative vitreoretinopathy, progression of cataract in initially phakic eyes, and any other adverse events reported. Overall the most important goal is to discern the benefit of scleral buckle combined with vitrectomy.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lori Rosman, Information Specialist for Cochrane Eyes and Vision (CEV), who created and executed the electronic search strategies. We thank the CEV US Satellite for comments and edits to the protocol and to the full review. We are grateful to the following peer reviewers for their time and comments: Mohammad Rafieetary (Charles Retina Institute), Stephanie Klemencic (Cincinnati Eye Institute), and Nancy Fitton.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Retinal Detachment] explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor: [Retinal Perforations] explode all trees #3 MeSH descriptor: [Vitreous Detachment] explode all trees #4 MeSH descriptor: [Vitreoretinopathy, Proliferative] explode all trees #5 vitreoretinopath* #6 retin* near/3 break* #7 retin* near/3 tear* #8 retin* near/3 detach* #9 retin* near/3 perforat* #10 {or #1‐#9} #11 MeSH descriptor: [Vitrectomy] explode all trees #12 MeSH descriptor: [Vitreoretinal Surgery] explode all trees #13 vitrec* #14 PPV* #15 vitre* surg* #16 {or #11‐#15} #17 #10 and #16

Appendix 2. MEDLINE Ovid search strategy

1. Randomized Controlled Trial.pt. 2. Controlled Clinical Trial.pt. 3. (randomized or randomised).ab,ti. 4. placebo.ab,ti. 5. drug therapy.fs. 6. randomly.ab,ti. 7. trial.ab,ti. 8. groups.ab,ti. 9. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 10. exp animals/ not humans.sh. 11. 9 not 10 12. exp Retinal Detachment/ 13. exp Retinal Perforations/ 14. exp Vitreous Detachment/ 15. exp Vitreoretinopathy, Proliferative/ 16. vitreoretinopath*.tw. 17. (retin* adj3 break*).tw. 18. (retin* adj3 tear*).tw. 19. (retin* adj3 detach*).tw. 20. (retin* adj3 perforat*).tw. 21. or/12‐20 22. exp Vitrectomy/ 23. vitrect*.tw. 24. exp Vitreoretinal Surgery/ 25. exp Vitreous Body/su [Surgery] 26. limit 25 to yr="1966 ‐ 1983" 27. PPV*.tw. 28. vitre* surg*.tw. 29. or/22‐24,26‐28 30. 21 and 29 31. 11 and 30

The search filter for trials at the beginning of the MEDLINE strategy is from the published paper by Glanville 2006.

Appendix 3. Embase.com search strategy

#1 'randomized controlled trial'/exp #2 'randomization'/exp #3 'double blind procedure'/exp #4 'single blind procedure'/exp #5 random*:ab,ti #6 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 #7 'animal'/exp OR 'animal experiment'/exp #8 'human'/exp #9 #7 AND #8 #10 #7 NOT #9 #11 #6 NOT #10 #12 'clinical trial'/exp #13 (clin* NEAR/3 trial*):ab,ti #14 ((singl* OR doubl* OR trebl* OR tripl*) NEAR/3 (blind* OR mask*)):ab,ti #15 'placebo'/exp #16 placebo*:ab,ti #17 random*:ab,ti #18 'experimental design'/exp #19 'crossover procedure'/exp #20 'control group'/exp #21 'latin square design'/exp #22 #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 #23 #22 NOT #10 #24 #23 NOT #11 #25 'comparative study'/exp #26 'evaluation'/exp #27 'prospective study'/exp #28 control*:ab,ti OR prospectiv*:ab,ti OR volunteer*:ab,ti #29 #25 OR #26 OR #27 OR #28 #30 #29 NOT #10 #31 #30 NOT (#11 OR #23) #32 #11 OR #24 OR #31 #33 'retina tear'/exp #34 'retina detachment'/exp #35 'vitreous body detachment'/exp #36 (retin* NEXT/3 break*):ab,ti #37 (retin* NEXT/3 tear*):ab,ti #38 (retin* NEXT/3 detach*):ab,ti #39 (retin* NEXT/3 perforat*):ab,ti #40 'vitreoretinopathy'/exp #41 vitreoretinopath*:ab,ti #42 #33 OR #34 OR #35 OR #36 OR #37 OR #38 OR #39 OR #40 OR #41 #43 'vitreoretinal surgery'/exp #44 vitrec*:ab,ti #45 ppv*:ab,ti #46 vitre*:ab,ti AND surg*:ab,ti #47 #43 OR #44 OR #45 OR #46 #48 #42 AND #47 #49 #32 AND #48

Appendix 4. PubMed search strategy

1. ((randomized controlled trial[pt]) OR (controlled clinical trial[pt]) OR (randomised[tiab] OR randomized[tiab]) OR (placebo[tiab]) OR (drug therapy[sh]) OR (randomly[tiab]) OR (trial[tiab]) OR (groups[tiab])) NOT (animals[mh] NOT humans[mh]) 2. (retina*[tw] AND (break*[tw] OR tear*[tw] OR detach*[tw] OR perforat*[tw])) NOT Medline[sb] 3. vitreoretinopath*[tw] NOT Medline[sb] 4. #2 OR #3 5. (vitrec*[tw] OR PPV*[tw] OR Pars Plana[tw]) NOT Medline[sb] 6. (vitre*[tw] AND surg*[tw]) NOT Medline[sb] 7. #5 OR #6 8. #1 AND #4 AND #7

Appendix 5. LILACS search strategy

(MH:C11.768.648$ OR MH:C11.768.740$ OR "vitreous detachment" OR MH:C11.980$ OR (retin$ AND break$) OR (retin$ AND tear$) OR (retin$ AND detach$) OR (retin$ AND perforat$) OR MH:C11.768.890$ OR MH:C11.975$ OR vitreoretinopathy$) AND (vitrec$ OR MH:E04.540.960$ OR PPV$ OR (vitre$ AND surg$) OR MH:E04.540.980$)

Appendix 6. ClinicalTrials.gov search strategy

(retina OR retinal OR "vitreous detachment" OR vitreoretinopathy) AND (vitrectomy OR PPV OR "vitreous surgery" OR "vitreoretinal surgery")

Appendix 7. WHO ICTRP search strategy

(retina AND vitrectomy OR retinal AND vitrectomy OR "vitreous detachment" AND vitrectomy OR vitreoretinopathy AND vitrectomy OR retina AND "vitreous surgery" OR retinal AND "vitreous surgery" OR "vitreous detachment" AND "vitreous surgery" OR vitreoretinopathy AND "vitreous surgery" OR retina AND "vitreoretinal surgery" OR retinal AND "vitreoretinal surgery" OR "vitreous detachment" AND "vitreoretinal surgery" OR vitreoretinopathy AND "vitreoretinal surgery")

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Lewis 1998.

| Methods |

Study design: randomized parallel group Number randomized: 84 eyes Exclusions after randomization: not reported Losses to follow up: not reported Numbers analyzed (total and per group): not reported Unit of analysis: eye How were missing data handled? not reported Power calculation: not reported |

|

| Participants |

Country: not reported Age: not reported Sex: not reported Inclusion criteria: not reported Exclusion criteria: not reported Equivalence of baseline characteristics: not reported |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention: vitreous surgery without scleral buckle Comparison intervention: vitreous surgery with scleral buckle Length of follow‐up: mean 18 months |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcomes, as defined: not reported

Secondary outcomes: postoperative retinal detachment, reoperation Adverse effects reported: not reported |

|

| Notes |

Study period: not reported

Funding sources: not reported

Declarations of interest: not reported Reported subgroup analyses: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Only conference abstract is available |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Only conference abstract is available |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Only conference abstract is available |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Only conference abstract is available |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Only conference abstract is available |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Only conference abstract is available |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Only conference abstract is available |

Sharma 2000.

| Methods |

Study design: randomized parallel group Number randomized: 21 eyes Exclusions after randomization: not reported Losses to follow‐up: none Numbers analyzed (total and per group): total: 21 eyes; pars plana vitrectomy combined with buckle group: 10 eyes; pars plana vitrectomy alone group Unit of analysis: eyes How were missing data handled? N/A Power calculation: not reported |

|

| Participants |

Country: not reported Age: not reported Sex: not reported Inclusion criteria: eyes with giant retinal tears requiring vitreoretinal surgery Exclusion criteria: not reported Equivalence of baseline characteristics: not reported |

|

| Interventions |

Intervention: vitreoretinal surgery without scleral buckle Comparison intervention: vitreoretinal surgery with scleral buckle Length of follow‐up: 6 months |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcomes, as defined: not reported

Secondary outcomes: postoperative retinal detachment, reoperation Adverse effects reported: not reported |

|

| Notes |

Study period: not reported

Funding sources: not reported

Declarations of interest: not reported Reported subgroup analyses: not reported |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Only conference abstract is available |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Only conference abstract is available |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Only conference abstract is available |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Only conference abstract is available |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Only conference abstract is available |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Only conference abstract is available |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Only conference abstract is available |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Falkner Radler 2015 | Not the population of interest |

Contributions of authors

MG, MF, DZ, JLR, LN, RC, AJ and FG developed the protocol. MG and DZ screened the studies for inclusion. All authors contributed to drafting the review and will be responsible for future updates.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

Methodological support provided by the Cochrane Eyes and Vision US Project, supported by grant 1 U01 EY020522, National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, USA.

-

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), UK.

- Richard Wormald, Co‐ordinating Editor for Cochrane Eyes and Vision (CEV), acknowledges financial support for his CEV research sessions from the Department of Health through the award made by the National Institute for Health Research to Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology for a Specialist Biomedical Research Centre for Ophthalmology.

- This review was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to the CEV UK editorial base.

The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS, or the Department of Health.

Declarations of interest

MG: no conflict of interest or financial interest. JLR: no conflict of interest or financial interest. DZ: no conflict of interest or financial interest. MF: no conflict of interest or financial interest. AJ: no conflict of interest or financial interest. LN: no conflict of interest or financial interest. RC: no conflict of interest or financial interest. FG: no conflict of interest or financial interest.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

Lewis 1998 {published data only}

- Lewis H. Is scleral buckling required in the management of uncomplicated giant retinal tears? Results of a prospective, randomized clinical trial. American Academy of Ophthalmology; 1998 Nov 8–11; New Orleans, LA. 1998:131.

Sharma 2000 {published data only}

- Sharma YR, Azad RV, Talwar D, Rajpal D. 360° scleral buckling in giant retinal tear. American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2000 Oct 20‐23; Orlando, FL. 2000:246.

References to studies excluded from this review

Falkner Radler 2015 {published data only}

- Falkner‐Radler CI, Graf A, Binder S. Vitrectomy combined with endolaser or an encircling scleral buckle in primary retinal detachment surgery: a pilot study. Acta Ophthalmologica 2015;93(5):464‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Adelman 2013

- Adelman RA, Parnes AJ, Sipperley JO, Ducournau D. Strategy for the management of complex retinal detachments: the European vitreo‐retinal society retinal detachment study report 2. Ophthalmology 2013;120(9):1809‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Al‐Khairi 2008

- Al‐Khairi AM, Al‐Kahtani E, Kangave D, Abu El‐Asrar AM. Prognostic factors associated with outcomes after giant retinal tear management using perfluorocarbon liquids. European Journal of Ophthalmology 2008;18(2):270‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ambresin 2003

- Ambresin A, Wolfensberger TJ, Bovey EH. Management of giant retinal tears with vitrectomy, internal tamponade, and peripheral 360 degrees retinal photocoagulation. Retina 2003;23(5):622‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ang 2010

- Ang GS, Townend J, Lois N. Epidemiology of giant retinal tears in the United Kingdom: the British Giant Retinal Tear Epidemiology Eye Study (BGEES). Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science 2010;51(9):4781‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ang 2012

- Ang GS, Townend J, Lois N. Interventions for prevention of giant retinal tear in the fellow eye. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006909.pub3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Aylward 1993

- Aylward GW, Cooling RJ, Leaver PK. Trauma‐induced retinal detachment associated with giant retinal tears. Retina 1993;13(2):136‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Batman 1999

- Batman C, Cekiç O. Vitrectomy with silicone oil or long‐acting gas in eyes with giant retinal tears: long‐term follow‐up of a randomized clinical trial. Retina 1999;19(3):188‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cahill 1998

- Cahill MT, Barry PJ, Kenna PF. Giant retinal tear in Usher syndrome type II: coincidence or association?. Retina 1998;18(2):177‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chang 1989

- Chang S, Lincoff H, Zimmerman NJ, Fuchs W. Giant retinal tears. Surgical techniques and results using perfluorocarbon liquids. Archives of Ophthalmology 1989;107(5):761‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chou 2007

- Chou SC, Yang CH, Lee CH, Yang CM, Ho TC, Huang JS, et al. Characteristics of primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in Taiwan. Eye 2007;21(8):1056‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cooling 1980

- Cooling RJ, Rice NS, Mcleod D. Retinal detachment in congenital glaucoma. British Journal of Ophthalmology 1980;64(6):417‐21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dabour 2014

- Dabour SA. The outcome of surgical management for giant retinal tear more than 180º. BMC Ophthalmology 2014;14:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Deeks 2017

- Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG (editors), on behalf of the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. Chapter 9. Analysing data and undertaking meta‐analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Churchill R, Chandler J, Cumpston MS (editors), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 5.2.0 (updated June 2017), Cochrane, 2017. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

Donoso 2003

- Donoso LA, Edwards AO, Frost AT, Ritter R 3rd, Ahmad N, Vrabec T, et al. Clinical variability of Stickler syndrome: role of exon 2 of the collagen COL2A1 gene. Survey of Ophthalmology 2003;48(2):191‐203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dotrelova 1997

- Dotrelova D, Karel I, Clupkova E. Retinal detachment in Marfan's syndrome. Characteristics and surgical results. Retina 1997;17(5):390‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dowler 1995

- Dowler JG, Lyons CJ, Cooling RJ. Retinal detachment and giant retinal tears in aniridia. Eye 1995;9(Pt 3):268‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Duquesne 1996

- Duquesne N, Bonnet M, Adeleine P. Preoperative vitreous hemorrhage associated with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: a risk factor for postoperative proliferative vitreoretinopathy?. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 1996;234(11):677‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Freeman 1978

- Freeman HM. Fellow eyes of giant retinal breaks. Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society 1978;76:343‐82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Freeman 1981

- Freeman HM, Castillejos ME. Current management of giant retinal breaks: results with vitrectomy and total air fluid exchange in 95 cases. Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society 1981;79:89‐102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ghosh 2004

- Ghosh YK, Banerjee S, Savant V, Kotamarthi V, Benson MT, Scott RA, et al. Surgical treatment and outcome of patients with giant retinal tears. Eye 2004;18(10):996‐1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Girard 1994

- Girard P, Mimoun G, Karpouzas I, Montefiore G. Clinical risk factors for proliferative vitreoretinopathy after retinal detachment surgery. Retina 1994;14(5):417‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Glanville 2006

- Glanville JM, Lefebvre C, Miles JN, Camosso‐Stefinovic J. How to identify randomized controlled trials in MEDLINE: ten years on. Journal of the Medical Library Association 2006; Vol. 94, issue 2:130‐6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Glasspool 1973

- Glasspool MG, Kanski JJ. Prophylaxis in giant tears. Transactions of the Ophthalmological Societies of the United Kingdom 1973;93:363‐71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Goezinne 2008

- Goezinne F, Heij EC, Berendschot TT, Gast ST, Liem AT, Lundqvist IL, et al. Low redetachment rate due to encircling scleral buckle in giant retinal tears treated with vitrectomy and silicone oil. Retina 2008;28(3):485‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guyatt 2011

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Tugewell P, Knottnerus A. GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2011;64(4):380‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2017

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC (editors). Chapter 8. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Churchill R, Chandler J, Cumpston MS (editors), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 5.2.0 (updated June 2017), Cochrane, 2017. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

Hoffman 1986

- Hoffman ME, Sorr EM. Management of giant retinal tears without scleral buckling. Retina 1986;6(4):197‐204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Holland 1977

- Holland PM, Smith TR. Broad scleral buckle in the management of retinal detachments with giant tears. American Journal of Ophthalmology 1977;83(4):518‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hovland 1968

- Hovland KR, Schepens CL, Freeman HM. Developmental giant retinal tears associated with lens coloboma. Archives of Ophthalmology 1968;80(3):325‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kanski 1975

- Kanski JJ. Giant retinal tears. American Journal of Ophthalmology 1975;79(5):846‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kertes 1997

- Kertes PJ, Wafapoor H, Peyman GA, Calixto N Jr, Thompson H. The management of giant retinal tears using perfluoroperhydrophenanthrene. A multicenter case series. Vitreon Collaborative Study Group. Ophthalmology 1997;104(7):1159‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kon 1999

- Kon CH, Occleston NL, Aylward GW, Khaw PT. Expression of vitreous cytokines in proliferative vitreoretinopathy: a prospective study. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science 1999;40(3):705‐12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kreiger 1992

- Kreiger AE, Lewis H. Management of giant retinal tears without scleral buckling. Use of radical dissection of the vitreous base and perfluoro‐octane and intraocular tamponade. Ophthalmology 1992;99(4):491‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kumar 2018

- Kumar V, Kumawat D, Bhari A, Chandra P. Twenty‐five‐gauge pars plana vitrectomy in complex retinal detachments associated with giant retinal tears. Retina 2018;38(4):670‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Leaver 1981

- Leaver PK, Lean JS. Management of giant retinal tears using vitrectomy and silicone oil/fluid exchange. A preliminary report. Transactions of the Ophthalmological Societies of the United Kingdom 1981;101(1):189‐91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Leaver 1984

- Leaver PK, Cooling RJ, Feretis EB, Lean JS, McLeod D. Vitrectomy and fluid/silicone‐oil exchange for giant retinal tears: results at six months. British Journal of Ophthalmology 1984;68(6):432‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lee 2009

- Lee SY, Ong SG, Wong DW, Ang CL. Giant retinal tear management: an Asian experience. Eye 2009;23(3):601‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Machemer 1972

- Machemer R, Parel JM, Norton EW. Vitrectomy: a pars plana approach. Technical improvements and further results. Transactions ‐ American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology 1972;76:462‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Machemer 1991

- Machemer R, Aaberg TM, Freeman HM, Irvine AR, Lean JS, Michels RM. An updated classification of retinal detachment with proliferative vitreoretinopathy. American Journal of Ophthalmology 1991;112(2):159‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Malbran 1990

- Malbran E, Dodds RA, Hulsbus R, Charles DE, Buonsanti JL, Adrogue E. Retinal break type and proliferative vitreoretinopathy in nontraumatic retinal detachment. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 1990;228(5):423‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mathis 1992

- Mathis A, Pagot V, Gazagne C, Malecaze F. Giant retinal tears: surgical techniques and results using perfluorodecalin and silicone oil tamponade. Retina 1992;12(3):S7‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

May 1992

- May DR. Buckle‐less repair of giant retinal tears. Ophthalmology 1992;99(8):1181‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Miller 1986

- Miller B, Miller H, Patterson R, Ryan SJ. Retinal wound healing. Cellular activity at the vitreoretinal interface. Archives of Ophthalmology 1986;104(2):281‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mitry 2011

- Mitry D, Singh J, Yorston D, Siddiqui MA, Wright A, Fleck BW, et al. The predisposing pathology and clinical characteristics in the Scottish retinal detachment study. Ophthalmology 2011;118(7):1429‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Navarro 2005

- Navarro R, Gris O, Broc L, Corcostegui B. Bilateral giant retinal tear following posterior chamber phakic intraocular lens implantation. Journal of Refractive Surgery 2005;21(3):298‐300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Norton 1969

- Norton EW, Aaberg T, Fung W, Curtin VT. Giant retinal tears. I. Clinical management with intravitreal air. American Journal of Ophthalmology 1969;68(6):1011‐21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ozdamar 1998

- Ozdamar A, Aras C, Sener B, Oncel M, Karacorlu M. Bilateral retinal detachment associated with giant retinal tear after laser‐assisted in situ keratomileusis. Retina 1998;18(2):176‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pal 2005

- Pal N, Sharma YR, Azad R, Chandra P. Isolated bilateral microspherophakia with giant retinal tear and rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Journal of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus 2005;42(4):238‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Review Manager 2014 [Computer program]

- Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5). Version 5.3. Copenhagen: Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014.

Rofail 2005

- Rofail M, Lee LR. Perfluoro‐n‐octane as a postoperative vitreoretinal tamponade in the management of giant retinal tears. Retina 2005;25(7):897‐901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ryan 1985

- Ryan SJ. The pathophysiology of proliferative vitreoretinopathy in its management. American Journal of Ophthalmology 1985;100(1):188‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schepens 1962

- Schepens CL, Dobble JG, McMeel JW. Retinal detachments with giant breaks: preliminary report. Transactions ‐ American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology 1962;66:471‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schepens 1967

- Schepens CL, Freeman HM. Current management of giant retinal breaks. Transactions ‐ American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology 1967;71(3):474‐87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schipper 2000

Scott 1975

- Scott JD. Giant tear of the retina. Transactions of the Ophthalmological Societies of the United Kingdom 1975;95(1):142‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Scott 1976

- Scott JD. Equatorial giant tears affected by massive vitreous retraction. Transactions of the Ophthalmological Societies of the United Kingdom 1976;96(2):309‐12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Scott 2002

- Scott IU, Murray TG, Flynn HW Jr, Feuer WJ, Schiffman JC. Outcomes and complications associated with giant retinal tear management using perfluoro‐n‐octane. Ophthalmology 2002;109(10):1828‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shinoda 2008

- Shinoda H, Nakajima T, Shinoda K, Suzuki K, Ishida S, Inoue M. Jamming of 25‐gauge instruments in the cannula during vitrectomy for vitreous haemorrhage. Acta Ophthalmologica 2008;86(2):160‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shunmugam 2014

- Shunmugam M, Ang GS, Lois N. Giant retinal tears. Survey of Ophthalmology 2014;59(2):192‐216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sirimaharaj 2005

- Sirimaharaj M, Balachandran C, Chan WC, Hunyor AP, Chang AA, Gregory‐Roberts J, et al. Vitrectomy with short term postoperative tamponade using perfluorocarbon liquid for giant retinal tears. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2005;89(9):1176‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stickler 2001

- Stickler GB, Hughes W, Houchin P. Clinical features of hereditary progressive arthro‐ophthalmopathy (Stickler syndrome): a survey. Genetics in Medicine 2001;3(3):192‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tseng 2004

- Tseng W, Cortez RT, Ramirez G, Stinnett S, Jaffe GJ. Prevalence and risk factors for proliferative vitreoretinopathy in eyes with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment but no previous vitreoretinal surgery. American Journal of Ophthalmology 2004;137(6):1105‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Verstraeten 1995

- Verstraeten T, Williams GA, Chang S, Cox MS Jr, Trese MT, Moussa M, et al. Lens‐sparing vitrectomy with perfluorocarbon liquid for the primary treatment of giant retinal tears. Ophthalmology 1995;102(1):17‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vidaurri‐Leal 1984

- Vidaurri‐Leal J, Bustros S, Michels RG. Surgical treatment of giant retinal tears with inverted posterior retinal flaps. American Journal of Ophthalmology 1984;98(4):463‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vilaplana 1999

- Vilaplana D, Guinot A, Escoto R. Giant retinal tears after photorefractive keratectomy. Retina 1999;19(4):342‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Weichel 2006

- Weichel ED, Martidis A, Fineman MS, McNamara JA, Park CH, Vander JF, et al. Pars plana vitrectomy versus combined pars plana vitrectomy‐scleral buckle for primary repair of pseudophakic retinal detachment. Ophthalmology 2006;113(11):2033‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Weller 1990

- Weller M, Wiedemann P, Heimann K. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy ‐ is it anything more than wound healing at the wrong place?. International Ophthalmology 1990;14(2):105‐17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wiedemann 1988

- Wiedemann P, Weller M. The pathophysiology of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Acta Ophthalmologica. Supplement 1988;189:3‐15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wilkinson 1999

- Wilkinson CP. Scleral buckling techniques: a simplified approach. In: Guyer DR, Yannuzi LA, Chang S, Shields JA, Green WR editor(s). Retina‐Vitreous‐Macula. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1999:1248‐71. [Google Scholar]

Williams 2006

- Williams GA, Aaberg TA Jr. Techniques of scleral buckling. In: Ryan SJ, Wilkinson CP editor(s). Retina. 4th Edition. Vol. 3, Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby, 2006. [Google Scholar]

Wolfensberger 2003

- Wolfensberger TJ, Aylward GW, Leaver PK. Prophylactic 360 degrees cryotherapy in fellow eyes of patients with spontaneous giant retinal tears. Ophthalmology 2003;110(6):1175‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yeung 2008

- Yeung L, Yang KJ, Chen TL, Wang NK, Chen YP, Ku WC, et al. Association between severity of vitreous haemorrhage and visual outcome in primary rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Acta Ophthalmologica 2008;86(2):165‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yorston 2002

- Yorston DB, Wood ML, Gilbert C. Retinal detachment in East Africa. Ophthalmology 2002;109(12):2279‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yoshino 1989

- Yoshino Y, Ideta H, Nagasaki H, Uemura A. Comparative study of clinical factors predisposing patients to proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Retina 1989;9(2):97‐100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Gutierrez 2017

- Gutierrez M, Rodriguez JL, Zamora‐De la Cruz D, Flores Pimentel MA, Jimenez‐Corona A, Novak LC, et al. Pars plana vitrectomy combined with scleral buckle versus pars plana vitrectomy for giant retinal tear. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD012646] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]