Abstract

Multiciliated cells (MCCs) amplify large numbers of centrioles, which convert into basal bodies that are required for producing multiple motile cilia. Most centrioles amplified by MCCs grow on the surface of organelles called deuterosomes, while a smaller number grow through the centriolar pathway in association with the two parent centrioles. Here we show that MCCs lacking deuterosomes amplify the correct number of centrioles with normal step-wise kinetics. This is achieved through a massive production of centrioles on the surface and in the vicinity of parent centrioles. Therefore, deuterosomes may have evolved to relieve, rather than supplement, the centriolar pathway during multiciliogenesis. Remarkably, MCCs lacking parent centrioles and deuterosomes also amplify the appropriate number of centrioles inside a cloud of pericentriolar and fibrogranular material. These data show that centriole number is set independently of their nucleation platforms and that massive centriole production in MCCs is a robust process that can self-organize.

Multiciliated cells (MCCs) contain tens of motile cilia that beat to drive fluid flow across epithelial surfaces. MCCs are present in the respiratory tract, brain ventricles and reproductive systems. Defects in motile cilia formation or beating lead to the development of hydrocephaly, lethal respiratory symptoms and fertility defects1–4.

A centriole, or basal body, serves as a template for the cilium axoneme. In cycling cells, centriole duplication is tightly controlled so that a single new procentriole forms adjacent to each of the two parent centrioles5. However, MCC progenitors with two parent centrioles produce hundreds of additional new centrioles to nucleate multiple motile cilia1. Steric constraints imposed by the “centriolar” pathway seem to restrict the number of procentrioles that can be nucleated by the parent centrioles. Therefore, centriole amplification is thought to rely on the assembly of dozens of MCC-specific organelles called deuterosomes, which each nucleate tens of procentrioles6–14.

Deuterosomes are assembled during centriole amplification and support the growth of ~90% of the procentrioles formed in mammalian MCCs12, 14. Deuterosomes have been proposed to be nucleated from the younger parent centriole12, but can form spontaneously in a cloud of pericentriolar material (PCM) in MCCs depleted of the parent centrioles15–17. Many proteins required for centriole formation in MCCs are common to centriole duplication11–15, 18–22. However, DEUP1 (gene name: CCDC67) has been identified as a deuterosome-specific protein that arose from a gene duplication event of the centriolar gene Cep63. Recent data suggest that Deup1 evolved to enable the formation of the deuterosomes and the generation of large numbers of motile cilia14.

In this manuscript, we interrogate the function of the deuterosome in mouse and Xenopus MCCs. Surprisingly, our findings reveal that deuterosomes are dispensable for centriole amplification and multiciliogenesis both in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, we show that neither deuterosomes nor parent centrioles are required for MCCs to amplify the correct number of centrioles. These findings raise new questions about the evolutionary role of the deuterosome during multiciliogenesis and the mechanisms regulating centriole number in MCCs.

Results

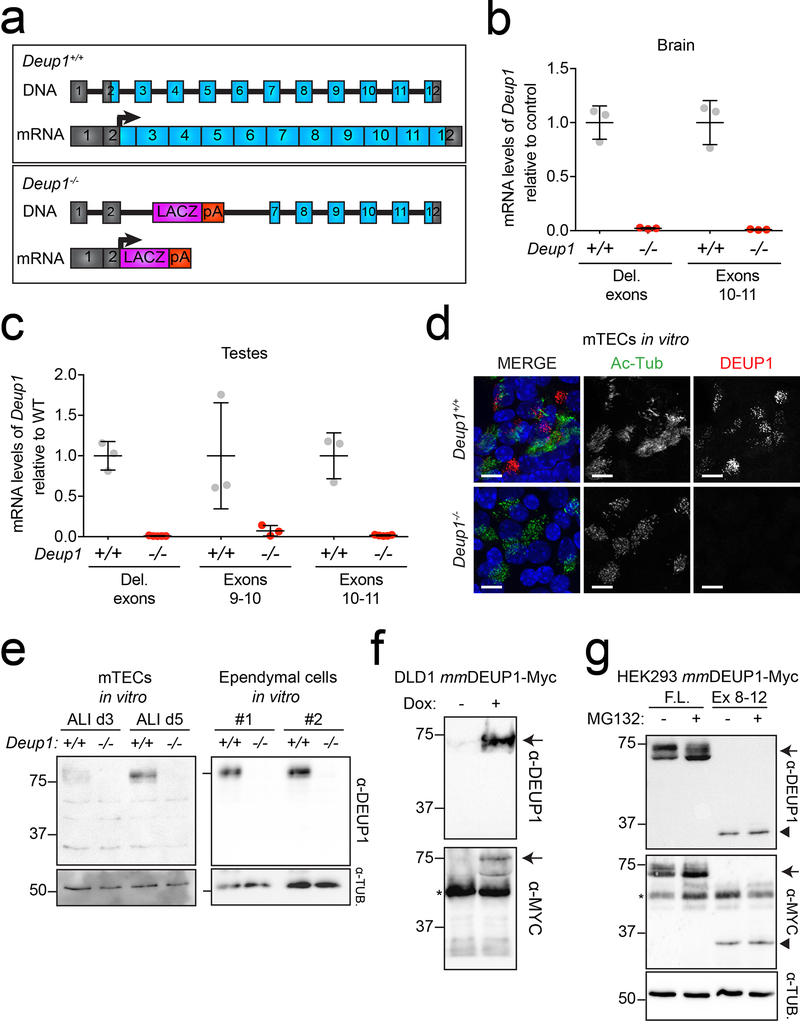

Generation of a Deup1 knockout mouse

To examine the role of the deuterosome in multiciliogenesis we created a Deup1 knockout mouse by replacing a region from within exon 2 to within exon 7 of the Deup1 gene with a LacZ reporter (Extended Data. 1a). RT-qPCR on brain and testes showed that Deup1 mRNA levels were reduced by > 10-fold in the Deup1 knockout compared to control mice (Extended Data. 1b, c).

To examine the process of multiciliogenesis in Deup1−/− cells, we utilized in vitro cultures of mouse tracheal epithelial cells (mTECs) or ependymal cells23, 24. Consistent with the absence of Deup1 mRNA, DEUP1 foci were absent in differentiating Deup1−/− tracheal cells (Extended Data. 1d). Moreover, full-length DEUP1 protein was undetectable by immunoblot in differentiating Deup1−/− ependymal and tracheal epithelial cells (Extended Data. 1e). An in-frame ATG is present near the start of exon 8 of the Deup1 gene. Although our antibody recognized the full-length and exon 8–12 DEUP1 protein fragment ectopically expressed in HEK293FT cells (Extended Data. 1f, g), neither full-length DEUP1, or the exon 8–12 protein fragment was detectable in cell lysates from differentiating Deup1−/− mouse tracheal or ependymal cells. We thus conclude that Deup1−/− mice are null for the DEUP1 protein.

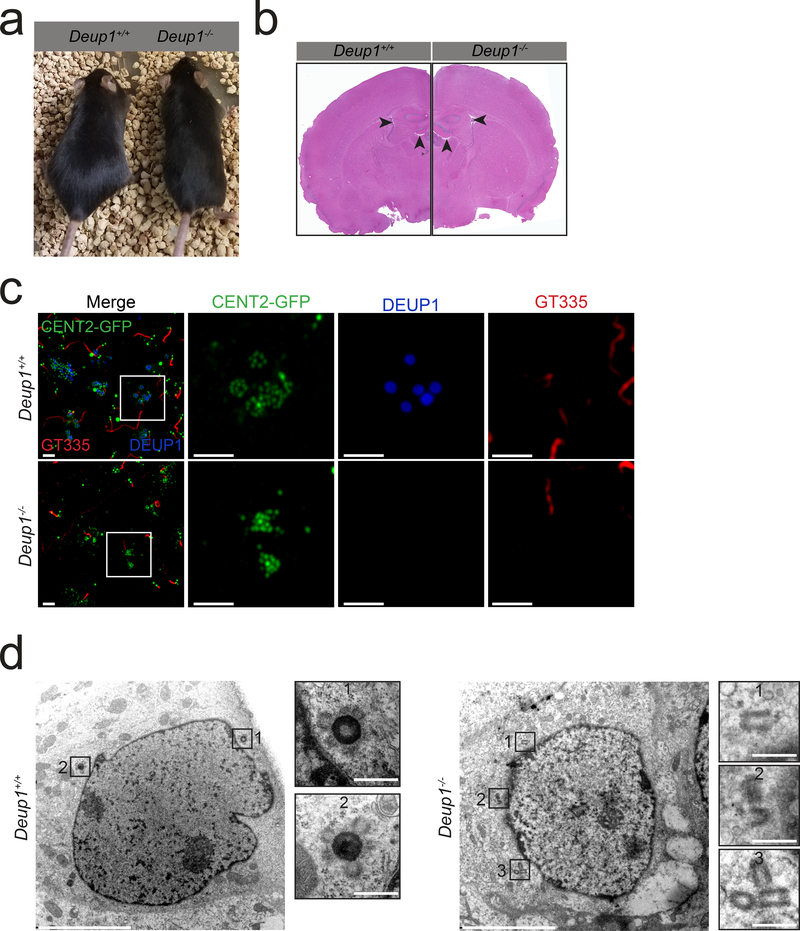

Deup1−/− mice lack deuterosomes

Deup1−/− mice were born at normal Mendelian ratios and had no apparent phenotype (Supplementary Table 1 and Fig. 1a–b). To determine whether Deup1−/− MCCs lack deuterosomes, we analyzed the ventricular walls of mouse brains at P3-P4 when ependymal progenitor cells differentiate into MCCs. While DEUP1 rings decorated with Centrin-stained procentrioles were observed in differentiating Deup1+/+ ependymal cells, DEUP1 foci were absent from the ventricular walls of Deup1−/− brains (Fig. 1c). To confirm the lack of deuterosomes in Deup1−/− cells, we performed serial transmission electron microscopy (TEM) through the volume of 11 differentiating Deup1−/− ependymal cells cultured in vitro. While cytoplasmic procentrioles were observed growing from deuterosomes in all of the Deup1+/+ ependymal cells analyzed, procentrioles were never found associated with deuterosomes in the cytoplasm of Deup1−/− cells (Fig. 1d). These data show that deuterosomes are absent in Deup1−/− mice and confirm previous findings that DEUP1 is a critical structural component of the deuterosome14.

Fig. 1. Deup1 knockout mice lack deuterosomes.

(a) Images of 5-month-old Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− mice.

(b) Histological sections from the brain of adult Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− mice. Arrowheads mark the lateral and third ventricles. Note there is no apparent hydrocephalus in the Deup1−/− mice.

(c) Immunofluorescence images of Centrin 2-GFP expressing Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− ependymal cells in vivo. Brain sections were stained with antibodies against GT335 to mark cilia and DEUP1 to mark the deuterosome. Scale bars represent 2 μm.

(d) Transmission electron microscopy of Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− ependymal cells in the growth stage. In Deup1+/+ cells deuterosomes are clearly observed in the cytoplasm (Box 1 and 2). In Deup1−/− cells deuterosomes are not detected. Instead, singlets (Box 1), doublets (Box 2), and groups (Box 3) of procentrioles are observed in the cytoplasm. Scale bars represent 5 μm and 500 nm for zoomed in regions of interest.

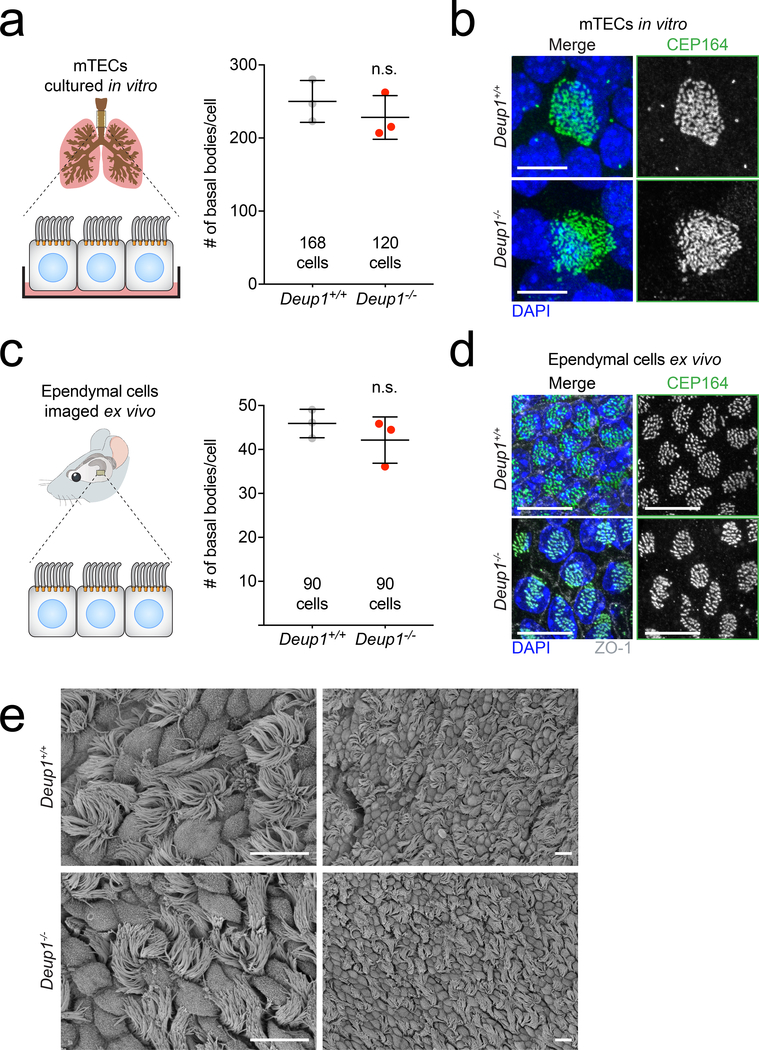

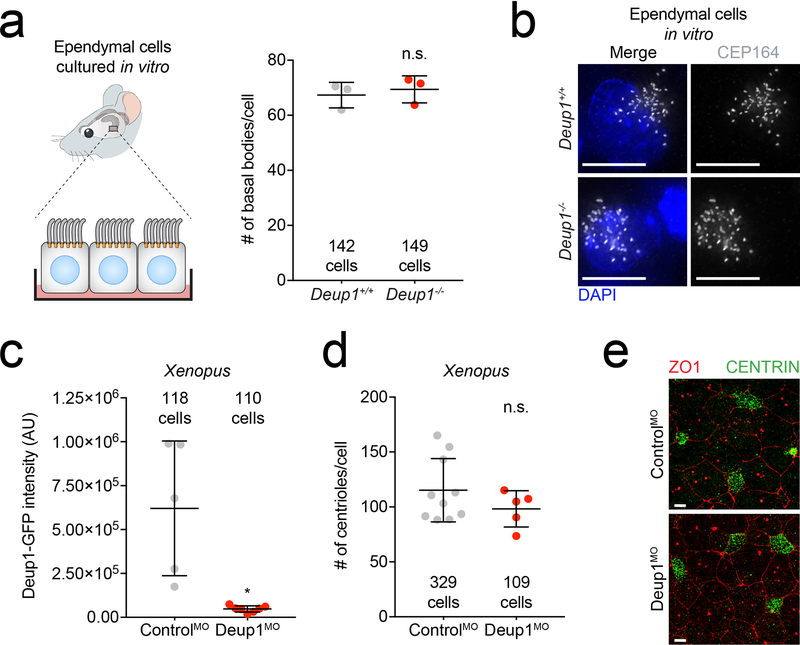

Deuterosomes are dispensable for centriole amplification during multiciliogenesis

To investigate the role of deuterosomes during centriole amplification in MCCs, we examined centriole number in mature MCCs. Surprisingly, knockout of DEUP1 did not significantly reduce the number of centrioles formed in multiciliated ependymal or tracheal cells in vitro (Fig. 2a, b and Extended Data. 2a, b). Consistent with our in vitro results, the number of centrioles produced in ependymal cells in the brain of Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− mice were comparable (Fig. 2c–d). In addition, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of mouse trachea revealed no differences in the multiciliated epithelium in Deup1−/− animals compared with control mice (Fig. 2e).

Fig. 2. Deuterosomes are dispensable for centriole amplification during multiciliogenesis.

(a) Quantification of basal body number in mTECs from Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− mice. Basal bodies were stained with CEP164. n = 3 mice/genotype. The total number of cells analyzed per genotype is indicated. P values, unpaired, two-tailed, Welch’s t-test. n.s. = not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Bars represent mean +/− SD.

(b) Representative images of basal bodies stained with CEP164 from Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− mTECs. Scale bars represent 5 μm.

(c) Quantification of the basal body marker CEP164 foci in ependymal cells from Deup1+/+ or Deup1−/− adult brain sections. n = 3 mice/genotype. The total number of cells per analyzed genotype is indicated. P values, unpaired, two-tailed, Welch’s t-test. n.s. = not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Bars represent mean +/− SD.

(d) Representative images of ependymal cells in adult brain sections from Deup1+/+ or Deup1−/− mice. DAPI marks the nuclei, ZO-1 marks tight junctions and CEP164 stains basal bodies. Scales bar represent 10 μm.

(e) Scanning electron microscopy images of tracheas from Deup1+/+ or Deup1−/− adult mice. Scale bar represents 10 μm.

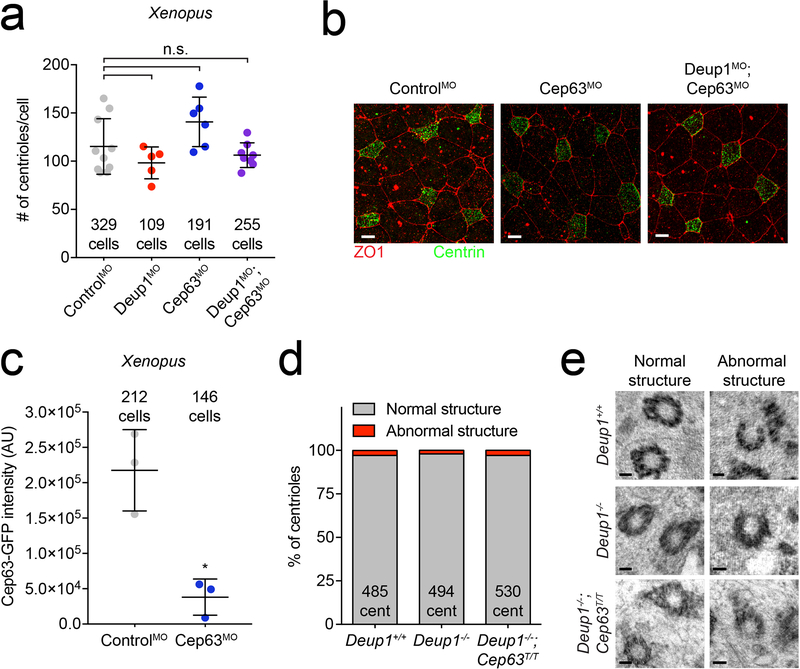

To test the requirement of DEUP1 for centriole amplification in a different vertebrate model, we examined the effects of Deup1 depletion in multiciliated cells from Xenopus embryonic epidermis. Due to the absence of an antibody against Xenopus Deup1, we validated the ability of a Deup1 morpholino oligonucleotide (MO) to efficiently silence expression of an mRNA encoding a deup1-GFP reporter in MCCs (Extended Data. 2c). Importantly, injection of the Deup1 MO did not significantly decrease the number of centrioles generated in Xenopus MCCs (Extended Data. 2d, e). These data suggest that Deup1 is not required to amplify the correct number of centrioles in MCCs of both Xenopus and mice.

Our observations contrast with a previous report that observed a reduction in centriole production after acute depletion of DEUP1 with an shRNA in mTECs14. To address a possible difference in the effect of chronic versus acute depletion of DEUP1, we used 4 pooled siRNAs to knock down Deup1 expression in ependymal cell cultures and analyzed centriole number in cells at the disengagement phase12 depleted of Deup1 (Extended Data. 3a,b). Consistent with the results observed in Deup1−/− mice, cells depleted of DEUP1 amplified comparable numbers of centrioles (Extended Data. 3c, d).

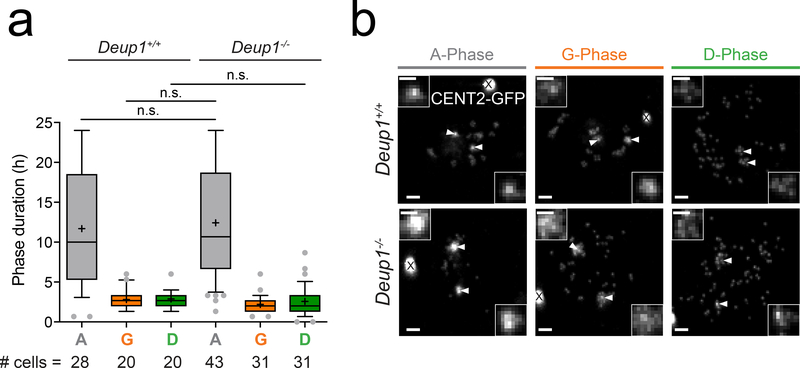

Procentrioles form with normal step-wise dynamics in cells lacking deuterosomes

To determine the dynamics of centriole amplification in the absence of deuterosomes we performed live imaging in differentiating control and Deup1−/− ependymal cells expressing GFP-tagged Centrin 2 (CENT2-GFP)25. It was previously established that centriole amplification proceeds through three stages: amplification, growth, and disengagement12, 19. Each of these phases of centriole amplification was distinguishable in both Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− cells (Supplementary Video 1, 2) and loss of DEUP1 did not affect their duration (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3. Live-imaging of differentiating Deup1−/− ependymal cells reveals normal, step-wise kinetics of centriole amplification.

(a) Box (25 to 75%) and whisker (10 to 90%) plots of A- (Gray), G- (Orange), and D- (Green) phase duration in differentiating Centrin 2-GFP Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− ependymal cells using time-lapse microscopy. A = amplification phase, G = growth phase, D = disengagement phase; n > 3 cultures/genotype. The total number of cells per genotype at each phase (# cells) is indicated. P values, unpaired, two-tailed, Welch’s t-test. n.s.=not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

(b) Still images from time-lapse videos of Centrin 2-GFP Deup1+/+ (Supplementary Video 1) or Deup1−/− (Supplementary Video 2) ependymal cells in the amplification (A), growth (G) or disengagement (D) phase. Arrow heads and zoomed regions mark the parent centrioles. X marks Centrin 2-GFP aggregates resulting from expression of the Centrin 2-GFP transgene25. Scale bars represent 2 μm.

The amplification stage in Deup1+/+ ependymal MCCs is marked by the emergence of CENT2-GFP rings representing procentrioles organized around deuterosomes (Fig. 3b, top row and Supplementary Video 1)12, 17. By contrast, CENT2-GFP rings were not observed in Deup1−/− cells. Instead, cells exhibited an increased CENT2-GFP signal around the parent centrioles and a gradual accumulation of faint CENT2-GFP foci arising from a region close to the parent centrioles (Fig. 3b, bottom row and Supplementary Video 2). During the growth stage, CENT2-GFP rings transformed into flower-like structures in control cells, reflecting the growth of procentrioles associated with deuterosomes (Fig. 3b, top row and Supplementary Video 1). In Deup1−/− cells, the CENT2-GFP signal around the parent centrioles developed into brighter CENT2-GFP spots, showing that the amplification of centrioles via the centriolar pathway is increased in cells lacking deuterosomes. The faint cytoplasmic CENT2-GFP foci in Deup1−/− cells also resolved into distinct CENT2-GFP spots that represent single or small groups of procentrioles (Fig. 3b, bottom row and Supplementary Video 2). At the disengagement stage, centrioles were simultaneously released from deuterosomes and parent centrioles in control cells, and from the parent centrioles and small groups of procentrioles in Deup1−/− cells. We conclude that Deup1−/− cells achieve the correct number of centrioles through normal step-wise dynamics of centriole amplification. Nevertheless, Deup1−/− cells differ from control cells in two important characteristics: first, the centriolar pathway is increased in Deup1−/− cells and second, procentrioles that are released in the cytoplasm are organized into smaller groups that do not adopt a ring-shaped morphology.

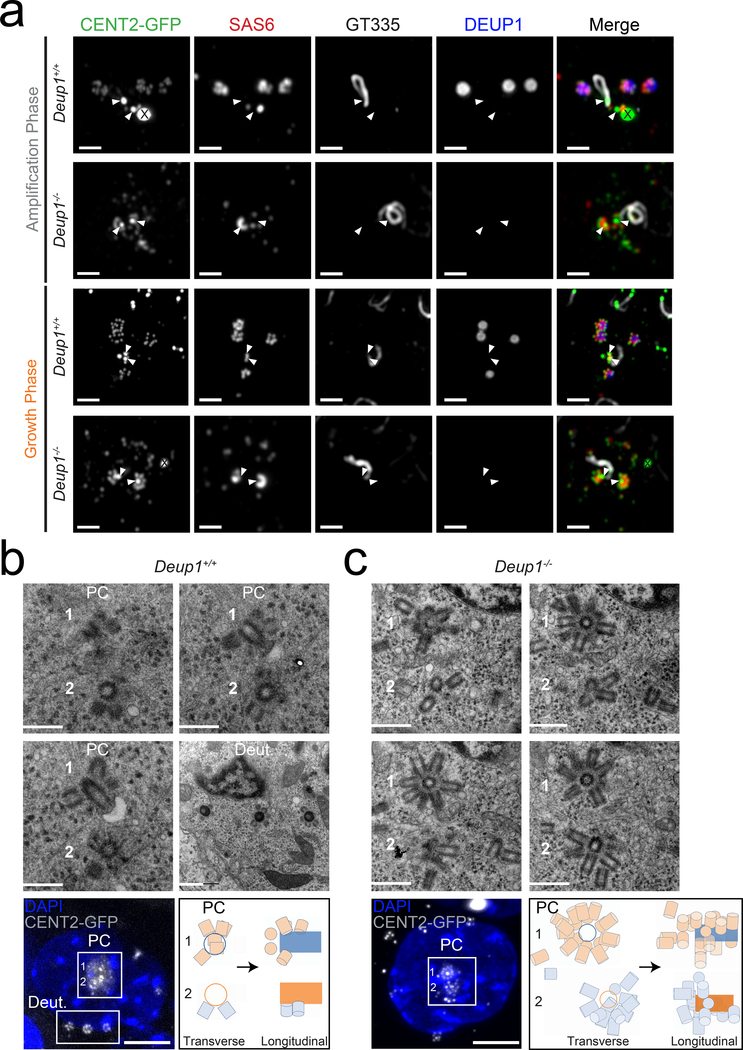

In the absence of deuterosomes, procentrioles form in the vicinity of the parent centrioles

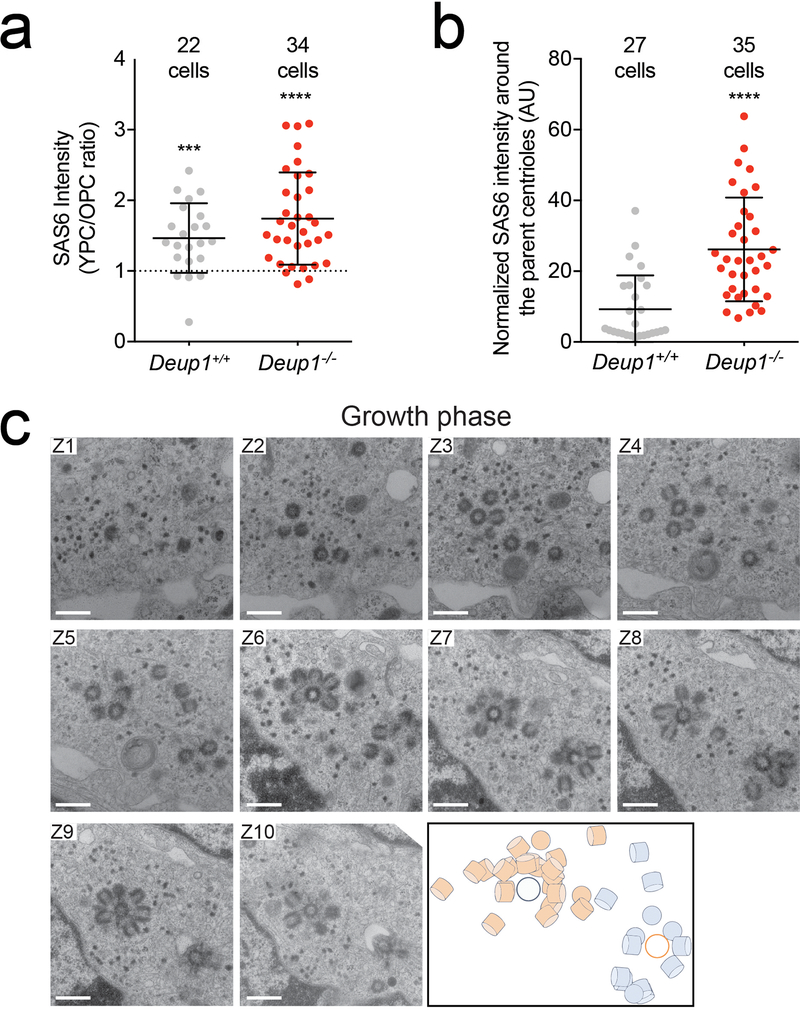

To increase the spatial resolution of our analysis, we performed super-resolution imaging of differentiating ependymal cells lining the brain ventricular walls. While in control cells, SAS6+ procentrioles were observed growing from both deuterosomes and parent centrioles during the amplification stage, in Deup1−/− brains, SAS6+ procentrioles were observed on the wall of the parent centrioles and scattered in the vicinity of these structures (Fig. 4a). An increase in SAS6 staining at the parent centrioles in Deup1−/− cells confirmed that more procentrioles are nucleated by parent centrioles compared to controls (Fig. 4a and Extended Data. 4b). We observed a preferential localization of SAS6 to the younger parent centriole compared to the older centriole (distinguishable in amplification stage by the presence of a cilium) in both Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− cells (Fig. 4a, and Extended Data. 4a). This asymmetry in SAS6 staining suggests that the younger parent centriole has a greater capacity for procentriole nucleation12. Consistent with live imaging, procentrioles that were present in the cytoplasm of Deup1−/− cells were more widely distributed during the growth stage than in the amplification stage and were organized as singlets or small groups of procentrioles (Fig. 4a). These data suggest that in the absence of deuterosomes, most procentrioles are formed on the wall of the parent centrioles and in their vicinity before being released into the cytoplasm.

Fig. 4. Centriole amplification in the absence of deuterosomes occurs on, and in proximity to, pre-existing centrioles.

(a) Immunofluorescence images of Centrin 2-GFP expressing Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− ependymal cells in vivo (P2-P6). Brain sections were stained with antibodies against GT335, SAS6, and DEUP1. GT335 marks the cilium that forms from the older parent centriole, SAS6 marks new procentrioles and DEUP1 marks the deuterosome. X marks Centrin 2-GFP aggregates resulting from expression of the Centrin 2-GFP transgene25. Arrowheads indicate location of pre-existing centrioles. Scale bars represent 2 μm.

(b) Correlative light and electron microscopy of a Centrin 2-GFP expressing Deup1+/+ ependymal cell in the growth phase. Procentrioles are formed by both parent centrioles (PC) and deuterosomes (Deut.). Bottom left shows an immunofluorescence image of the Centrin 2-GFP Deup1+/+ cell depicted in the EM images. Bottom right shows a schematic representation of the relative position of procentrioles formed on the parent centrioles. Scale bars represent 600 nm for the EM images and 5 μm for the immunofluorescence image. This cell is shown in Supplementary Video 3.

(c) Correlative light and electron microscopy of a Centrin 2-GFP-expressing Deup1−/− cell reveals centriole amplification on, or in close proximity to, the parent centrioles (PC). Procentrioles are also observed further away in the cytoplasm. Bottom left shows an immunofluorescence image of the Centrin 2-GFP Deup1−/− cell depicted in the EM images. Bottom right shows a schematic representation of the relative position of procentrioles formed on the parent centrioles. Scale bars represent 600 nm for the EM images and 5 μm for the immunofluorescence image. This cell is shown in Supplementary Video 4 and 5.

To resolve procentriole formation that occurs close to the parent centrioles, we performed serial-section electron microscopy (EM) or Correlative Light-Electron Microscopy (CLEM) on cultured ependymal cells during the growth stage. As expected, the majority of procentrioles formed on the surface of deuterosomes and small numbers were present on the parent centrioles in Deup1+/+ cells (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Video 3). Interestingly, in Deup1−/− cells, we observed that more procentrioles were produced on the surface of the parent centrioles (Fig. 4c, Extended Data. 4c, Supplementary Video 4). While procentrioles were predominantly nucleated from the proximal end of the parent centrioles in control cells, they could form along the entire length of the parent centrioles in Deup1−/− cells, allowing the growth of up to 18 procentrioles from a single parent centriole (Fig. 4c and Extended Data. 4c, Supplementary Video 5). Consistent with live-cell imaging and ex vivo analysis, singlets or groups of 2–3 procentrioles often connected at their proximal side were also observed in the vicinity of the parent centrioles and further away in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1d, Fig. 4c and Extended Data. 4c). During the growth phase these groups of procentrioles are observed around the nuclear membrane (Fig. 1d). We conclude that in the absence of deuterosomes, the centriolar pathway is enhanced and procentrioles form along the entire length and in the vicinity of the parent centrioles. As the amplification stage progresses, singlets or groups of procentrioles are released into the cytoplasm and are organized around the nuclear envelope in a similar configuration to that seen in control cells17, 19.

Despite the increase in nucleation of procentrioles on the parent centriole, incomplete rings of SAS6 were often observed around the circumference of parent centrioles in Deup1−/− cells (Fig. 4a), and sites unoccupied by procentrioles were also visible on the walls of the parent centrioles by EM (Fig. 4c and Extended Data. 4c, Supplementary Video 4–5). This non-homogenous distribution may arise as a result of a symmetry breaking reaction that creates a non-uniform distribution of PLK4, similar to what occurs in cycling cells26. Alternatively, procentrioles may detach from the walls of the parent centrioles, which could explain their presence in close proximity to the parent centrioles (Fig. 4a, c and Extended Data. 4c).

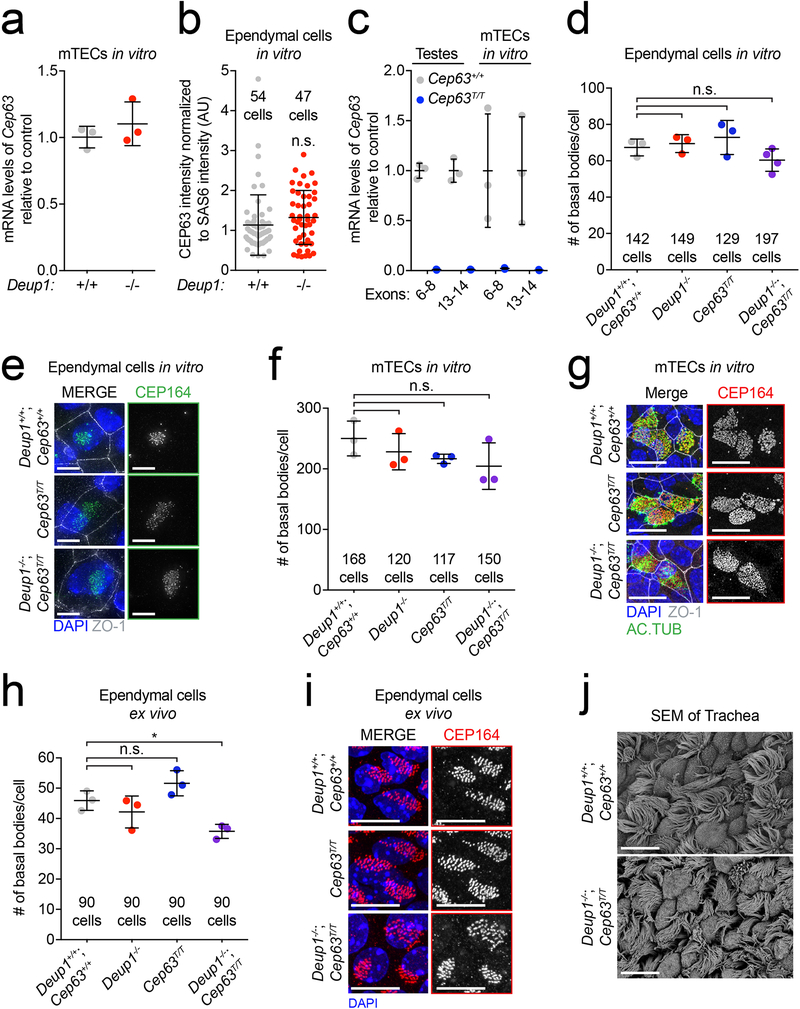

CEP63 loss modestly reduces centriole amplification in Deup1−/− MCCs

Deup1 is a paralogue of the centriolar protein encoding gene Cep63. The two proteins share 37% sequence identity in mouse and compete for binding to the centriole duplication protein CEP15214. It has been proposed that CEP63 could compensate for the loss of DEUP1 by enhancing the recruitment of CEP152 to the parent centrioles to trigger increased procentriole nucleation14. Importantly, the level of Cep63 mRNA in whole culture extracts and CEP63 protein in single cells in the process of centriole amplification was unchanged in Deup1−/− cells (Extended Data. 5a, b). We obtained Cep63T/T mice that have the Cep63 gene disrupted with a gene-trap insertion27, 28. Cep63T/T mice showed a > 40-fold reduction in Cep63 mRNA levels in mouse testes and mTECs (Extended Data. 5c). Loss of Cep63 expression did not decrease the final number of centrioles produced in fully differentiated mTECs or ependymal cells in vitro or in vivo (Extended Data. 5d–5i). SEM of trachea revealed no apparent defect in multiciliogenesis in Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T mice compared with control (Extended Data. 5j). In addition, MO-mediated depletion of both Cep63 and Deup1 in multiciliated Xenopus epithelial cells did not significantly decrease the final number of centrioles generated (Extended Data. 6a–c). However, Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T ependymal cells analyzed ex vivo showed a 22% decrease in the number of centrioles amplified compared to control (Extended Data. 5h,i). Although not reaching statistical significance, we also note a modest decrease in centriole number in Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T ependymal cells (10%) and mTECs (18%) differentiated in vitro (Extended Data. 5d–5g). These data show that CEP63 may modestly compensate for the loss of Deup1.

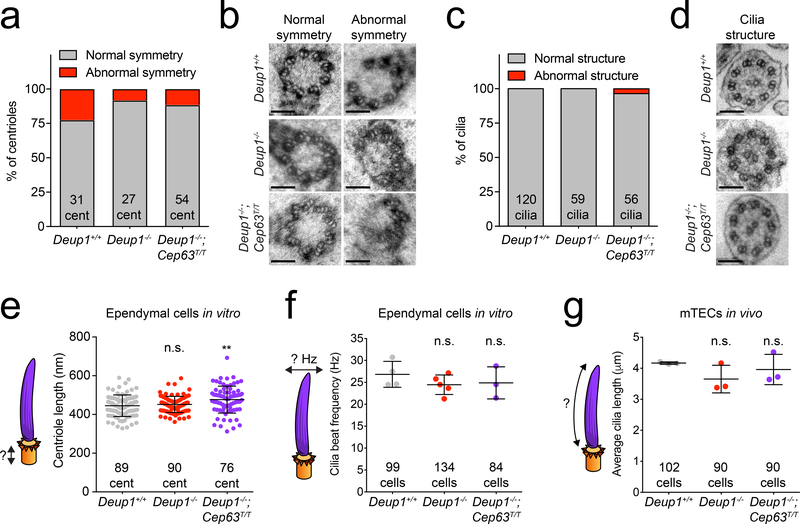

Loss of Deup1 does not compromise basal body structure or cilia function

To analyze the core structure of basal bodies that assemble in Deup1−/− and Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T MCCs, we performed TEM on fully-differentiated cultured ependymal MCCs. >95% of the mature basal bodies in Deup1+/+, Deup1−/− and Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T MCCs exhibited a normal cylindrical structure (Extended Data. 6d–e). High resolution TEM analysis on transversally sectioned basal bodies and cilia revealed no increase in microtubule triplet symmetry defects or in cilia structural abnormalities in Deup1−/− and Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T MCCs compared to control cells (Fig. 5a–d). The length of mature basal bodies was similar in control and Deup1−/− ependymal cells but was ~ 7% longer in the Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T MCCs (Fig. 5e). Deup1−/− and Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T ependymal cells produced cilia that beat with similar frequencies to that observed in control cells (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Video 6–8). Finally, the length of the cilia formed in vivo measured by SEM of trachea was comparable in control, Deup1−/− and Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T cells (Fig. 5g). Together, these data show that deuterosomes are not required to produce structurally sound basal bodies and functional cilia.

Fig. 5. Loss of Deup1 does not compromise basal body structure or cilia function.

(a) Quantification of the percent of centrioles from in vitro ependymal cells with abnormal symmetry in Deup1+/+, Deup1−/− and Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T cells. n > 10 cells/genotype. The total number of centrioles analyzed per genotype is indicated.

(b) Representative TEM images of normal and abnormal symmetry observed in centrioles in Deup1+/+, Deup1−/− and Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T ependymal cells in vitro. Scale bar represents 100 nm.

(c) Quantification of the percent of cilia with abnormal structure in fully differentiated Deup1+/+, Deup1−/− and Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T ependymal cells in vitro. n > 5 cells/genotype. The total number of cilia analyzed per genotype is indicated.

(d) Representative TEM images of normal cilia in fully differentiated Deup1+/+, Deup1−/− and Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T ependymal cells in vitro. Scale bar represents 100 nm.

(e) Centriole length quantification via TEM in fully differentiated Deup1+/+, Deup1−/− and Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T ependymal cells. n > 10 cells/genotype. Each point represents a single centriole. The total number of centrioles analyzed per genotype is indicated. P values, unpaired, two-tailed, Welch’s t-test. n.s. = not statistically significant (p > 0.05); **: p ≤ 0.01. Bars represent mean +/− SD.

(f) Quantification of ciliary beat frequency measured in fully differentiated Deup1+/+, Deup1−/− and Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T ependymal cells. n = ≥ 3 cultures/genotype. The total number of cells analyzed per genotype is indicated. P values, unpaired, two-tailed, Welch’s t-test. n.s. = not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Bars represent mean +/− SD.

(g) Quantification of cilia length measured using scanning electron microscopy of Deup1+/+, Deup1−/− and Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T mTECs in vivo. The total number of cells analyzed per genotype is indicated. P values, unpaired, two-tailed, Welch’s t-test. n.s. = not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Bars represent mean +/− SD.

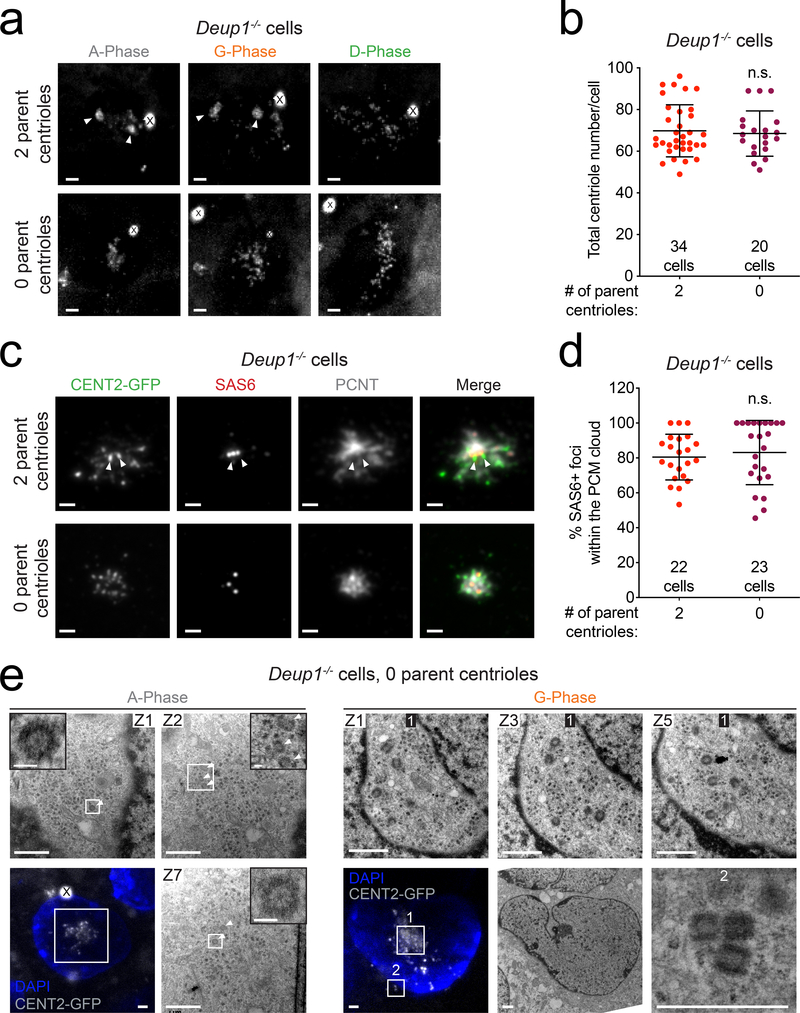

Parent centrioles are not required for centriole amplification in cells lacking deuterosomes

We interrogated the role of parent centrioles in promoting centriole amplification in Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− cells. Recent work has shown that treatment of cycling MCC progenitor cells with the PLK4 inhibitor centrinone depletes parent centrioles, but does not prevent deuterosome formation during MCC differentiation15–17, 29. By treating ependymal progenitors with centrinone during their proliferation, we obtained a mixed population of cells with 2, 1 or 0 parent centrioles. MCC differentiation was then triggered after centrinone washout and centriole amplification monitored by live-cell imaging in CENT2-GFP-expressing Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− cells that lacked parent centrioles. Remarkably, like previously described in Deup1+/+ cells17, the loss of parent centrioles did not prevent centriole amplification in Deup1−/− ependymal cells (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Video 9, 10). In addition, the final number of centrioles produced in Deup1−/− cells lacking parent centrioles was similar to that in Deup1−/− cells with two parent centrioles (Fig. 6b). These data suggest that neither parent centrioles nor deuterosomes are required for the massive centriole amplification that occurs in mouse MCCs.

Fig. 6. Centriole amplification can occur without deuterosomes and parent centrioles.

(a) Images from videos of Centrin 2-GFP-expressing Deup1−/− ependymal cells transiently treated with centrinone to deplete the preexisting centrioles. Images show cells with 2 (Supplementary Video 9) or 0 (Supplementary Video 10) parent centrioles. The phases of centriole amplification cannot be accurately determined in Deup1−/− cells with 0 parent centrioles. X marks Centrin 2-GFP aggregates25. Arrowheads mark the parent centrioles when present. Scale bars represent 2μm.

(b) Centriole number in Centrin 2-GFP-expressing Deup1−/− ependymal cells. Quantifications were carried out using time-lapse imaging in D-phase cells that began centriole amplification with 2 or 0 parent centrioles. Each point represents a single cell. Total number of cells analyzed is indicated. n > 3 cultures/condition. P values, unpaired, two-tailed, Welch’s t-test. n.s. = not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Bars represent mean +/− SD.

(c) Immunofluorescence images of Centrin 2-GFP-expressing Deup1−/− cultured ependymal cells treated with centrinone to deplete the parent centrioles. Images show cells with 2 or 0 parent centrioles. Arrowheads mark parent centrioles when present. Scale bars represent 2 μm.

(d) Quantification of the percentage of SAS6+ foci localized within the PCM cloud in Centrin 2-GFP expressing Deup1−/− ependymal cells during the amplification phase of cells with either 2 or 0 parent centrioles. Quantification is based on the localization of SAS6 foci within the PCM cloud marked by PCNT staining. Each point represents a single cell. Total number of cells analyzed is indicated. n = ≥ 2 cultures/condition. P values, unpaired, two-tailed, Welch’s t-test. n.s. = not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Bars represent mean +/− SD.

(e) Correlative light and electron microscopy of Centrin 2-GFP-expressing Deup1−/− ependymal cells treated with centrinone to deplete the parent centrioles. (Left) A cell in amplification phase (left) and growth phase (right) are shown (Supplementary Video 11 and 12). Arrowheads mark procentrioles forming in the absence of preexisting centrioles and deuterosomes. They form as either single freestanding procentrioles (Box 1) or small groups of 2–3 procentrioles (Box 2). Scale bars represent 1 μm and 100 nm for the zoomed in regions of interest.

Procentrioles are amplified within the confines of a PCM cloud

Immunofluorescence staining of in vivo and in vitro differentiating ependymal MCCs in the amplification and growth phase suggested that procentrioles were largely amplified within the confines of a cloud marked by the PCM protein, Pericentrin (PCNT) (Fig. 6c–d, Extended Data. 7a,b). This preferential localization of newborn procentrioles occurred whether or not deuterosomes or parent centrioles were present. The abundance and the size of the PCNT cloud was not altered by the absence of deuterosomes and parent centrioles (Extended Data. 7c,d). To further analyze how centrioles are amplified in the absence of both parent centrioles and deuterosomes, we performed CLEM on a Deup1−/− ependymal cell that lacked parent centrioles during the amplification or the growth phase. We observed single or small groups of procentrioles in a nuclear pocket where fibrogranular material was concentrated6, 8, 30 (Fig. 6e, Supplementary Video 11, 12). This reveals that the minimal microenvironment for centriole biogenesis and number control in MCCs does not require the deuterosome or parent centrioles. Rather, it is characterized by a proximity to the nuclear membrane and the presence of PCM and fibrogranular material.

Discussion

In this manuscript, we show that deuterosomes are dispensable for procentriole amplification during multiciliogenesis. Cells that lack deuterosomes amplify the correct number of centrioles through apparently normal step-wise kinetics. However, this amplification occurs through the massive production of procentrioles from along the entire length of the parent centrioles and in their vicinity, suggesting that deuterosome organelles have evolved to relieve rather than supplement the centriolar pathway (Extended Data. 7e). Remarkably, in the absence of both deuterosomes and parent centrioles, MCC progenitors still amplify the appropriate number of centrioles within the confines of a cloud of PCM and fibrogranular material (Extended Data. 7e). We conclude that centriole number is set independently of the centrosome and deuterosome organelles, and that centriole amplification in MCCs is a robust process supported by the self-assembly properties of centrioles.

A previous study reported that centriole production was reduced by ~35% in differentiating mTECs following stable expression of a Deup1 shRNA14. By contrast, our data demonstrate that loss of DEUP1, through gene knockout in tracheal and ependymal cells, or through siRNA depletion in ependymal cells, does not significantly reduce the final number of centrioles. The reason for this discrepancy may arise from the quantification of centriole number during the growth stage14, where procentrioles in Deup1−/− MCCs are difficult to accurately count due to upregulation of the centriolar pathway. By contrast, our quantification was performed at the disengagement/multiple basal body stages, where individual centrioles can be better resolved. In the same study, Zhao et al., showed that shRNA depletion of both CEP63 and DEUP1 decreased the number of centrioles produced in cultured mTECs by > 90%. In our study, we observed only a modest decrease in centriole formation in Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T tracheal and ependymal cells. The involvement of CEP63 in centriole amplification in Deup1−/− MCCs requires further investigation.

While defects in centriole amplification in MCCs can lead to the development of a condition known as Reduced Generation of Motile Cilia (RGMC)31–33, patients with mutations in DEUP1 have yet to be identified. According to the gnomAD database, 4.7% of Africans are heterozygous for a non-sense mutation in exon 12 of DEUP1 (p.Arg468Ter) which is predicted to lead to a truncated or absent protein product, and homozygous individuals have not been reported to have RGMC symptoms34. Moreover, our study shows that the kinetics of centriole amplification and centriole number, structure, and function are unaffected by the absence of deuterosomes in mouse MCCs. Consistent with deuterosomes being dispensable for centriole amplification, flatworms lack DEUP1 and can produce MCCs with dense multicilia without utilizing deuterosome structures35, 36. Taken together, these observations question the nature of the benefit provided by deuterosome organelles that are widely conserved across vertebrate MCCs.

When deuterosomes are absent, the centrosomal region becomes densely populated with procentrioles, suggesting that deuterosomes could help prevent the overcrowding of parent centrioles that may interfere with other centrosomal functions. DEUP1 interacts with CEP152 and is capable of self-assembling into deuterosome-like structures when expressed in bacteria14. One possibility is that DEUP1 recruits CEP152 and biases centriole nucleation away from the parent centrioles. Alternatively, an interaction with CEP152 could allow DEUP1 to be recruited by procentrioles nucleated on, or in the vicinity of, the parent centrioles. This hypothesis is consistent with the observation that deuterosomes are often found associated with the younger parent centriole, and that more procentrioles amplify from this site in Deup1−/− cells12. In both cases, DEUP1 self-assembly would relieve the centriolar pathway by sequestering procentrioles into groups away from the parent centrioles.

In Deup1−/− cells, procentrioles are observed along the entire length of the parent centrioles and in their vicinity by EM and super-resolution imaging of ependymal MCCs. PCM staining and live-imaging suggests that these procentrioles are progressively released from the centrosomal region. How these procentrioles arise remains unclear. One possibility is that all of the centrioles in Deup1−/− cells are nucleated on the wall of the parent centrioles, but some detach because of ectopic attachment or steric constraints. Another possibility is that some procentrioles are nucleated “de novo” within the PCM37. Finally, we cannot exclude the possibility that procentrioles could also be nucleated by other procentrioles. This is supported by presence of orthogonal and co-linear configurations of procentrioles in the cytoplasm of Deup1−/− cells with or without parent centrioles (Fig. 1e, 4c, 6e, Extended Data. 4c). We note however that procentrioles engaged in an orthogonal or co-linear configuration have similar lengths, arguing against a reduplication process. Nucleation by centrosomal centrioles, de novo centriole assembly and centriole reduplication have been proposed to contribute to jointly to centriole amplification in the MCCs of the Macrostomum flatworm that lack deuterosomes35. In MCCs that lack both centrosomes and deuterosomes, such as in the Schmidtea Mediterranea flatworm, the mode of centriole amplification is unknown36.

Our study suggests that the minimal environment for centriole amplification in MCCs does not require deuterosomes or parent centrioles but is characterized by the presence of PCM and fibrogranular material. Of note, fibrogranular material contains the protein PCM1, which is also required to scaffold the assembly of “pericentriolar satellites” that are found in non-MCCs. It is therefore possible that the fibrogranular material is functionally equivalent to the pericentriolar satellites of non-MCCs38–41. Additional studies will be required to identify the minimal components involved in centriole assembly and number control, and to define the role of DEUP1 and the deuterosome in MCCs.

Methods

Mouse models

Mice were housed and cared for in an AAALAC-accredited facility and experiments were conducted in accordance with Institute Animal Care and Use Committee approved protocols (for AJH), or in accordance with the guidelines of the European Community and French Ministry of Agriculture and were approved by the Direction départementale de la protection des populations de Paris (Approval number APAFIS#9343–201702211706561 v7) (for AM). The study is compliant with all relevant ethical regulations regarding animal research.

Deup1−/− mouse

Deup1 heterozygous sperm (Deup1tm1.1(KOMP)Vlcg) was obtained from the U.C.-Davis Knockout Mouse Phenotyping Consortium (project ID: VG11314). NIH grants to Velocigene at Regeneron Inc (U01HG004085) and the CSD Consortium (U01HG004080) funded the generation of gene-targeted ES cells for 8500 genes in the KOMP Program and archived and distributed by the KOMP Repository at UC Davis and CHORI (U42RR024244). Mice were rederived using C57B/L6N mice at the Johns Hopkins University, School of Medicine Transgenic Core Laboratory. These animals were maintained on a congenic C57BL/6N background. The following primers were used for genotyping: Mut For 5’-ACT TGC TTT AAA AAA CCT CCC ACA-3’, Mut Rev 5’-GGA AGT AGA CTA ACG TGG AGC AAG C-3’, WT For 5’-TAG GGC ACT GTT GGG TAT ATT GG-3’, WT Rev 5’-CCA CAC ATT TCT GCT TCT CC-3’. Embryos and adults from both genders were included in our analysis.

Cep63T/T mouse

Cep63T/T mice were obtained from the laboratory of Travis Stracker from the Institute for Research in Biomedicine—Barcelona. The generation of these Cep63 gene-trapped mice was described previously27, 28. Cep63T/T mice were backcrossed for two generations onto a C57Bl/6N strain. The following primers were used for genotyping: Cep63–5P2 5’-GTA GGA CCA GGC CTT AGC GTT AG-3’, Cep63–3P1a 5’-TAA GTG TAA AAG CCG GGC GTG GT −3’, and MutR (B32) 5’-CAA GGC GAT TAA GTT GGG TAA CG −3’.

CENT2-GFP Mouse

CENT2-GFP mice (CB6-Tg(CAG-EGFP/CETN2)3–4Jgg/J) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory25. These animals were maintained on a C57Bl/6J background. Experiments were performed on cells from homozygous or heterozygous CENT2-GFP.

Double transgenic CENT2-GFP; Deup1−/− Mouse

Homozygous CENT2-GFP mice were crossed with Deup1−/− mice to generate CENT2-GFP+/−;Deup+/−. These double heterozygous mice were then crossed to produce Deup1−/− mice (identified through genotyping) positive for CENT2-GFP (either CENT2-GFP+/− or CENT2-GFP −/−, identified using a fluorescence binocular).

Cell Culture

Primary cells

Mouse tracheal epithelial cell (mTEC) cultures were harvested and grown as previously described23. Briefly, tracheas were harvested from mice from 3 weeks to 12 months of age. Tracheas were then incubated in Pronase (Roche) overnight at 4 degrees. The following day, tracheal cells were dissociated by enzymatic and mechanical digestion. Cells were plated onto 0.4 μm Falcon transwell membranes (Transwell®, Corning). Once cells were confluent (~proliferation day 5), media from the apical chamber was removed and basal media was replaced with low serum (NuSerum) media. This timepoint is considered Air-Liquid Interface (ALI) day 0. Cells were then allowed to differentiate until needed for analysis (ALI day 3 or day 5).

For mouse ependymal cell cultures, brains were dissected from P0 – P2 mice, dissociated and cultured as previously described24. Briefly, mice were sacrificed by decapitation. The brains were dissected in Hank’s solution (10% HBSS, 5% HEPES, 5% sodium bicarbonate, 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (P/S) in pure water) and the telencephalon were cut manually into pieces, followed by enzymatic digestion (DMEM glutamax, 33% papain (Worthington 3126), 17% DNAse at 10 mg/ml, 42% cystein at 12 mg/ml) for 45 minutes at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Digestion was stopped by addition of a solution of trypsin inhibitors (Leibovitz Medium L15, 10% ovomucoid at 1 mg/ml, 2% DNAse at 10 mg/ml). The cells were then washed in L15 and resuspended in DMEM glutamax supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% P/S in a Poly-L-lysine (PLL)-coated flask. Ependymal progenitors proliferated for 4–5 days until confluence before shaking (250 rpm) overnight. Pure confluent astroglial monolayers were re-plated at a density of 7 × 104 cells/cm2 (differentiation day 1) in DMEM glutamax, 10% FBS, 1% P/S on PLL coated coverslides for immunocytochemistry experiments, Lab-Tek chambered coverglasses (8 well; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for time-lapse experiments, 4-well glass bottom slide (Ibidi) for ciliary beating frequency measurements or glass-bottom dishes with imprinted 50 mm relocation grids (Ibidi) for correlative3D-SIM/EM and maintained overnight. The medium was then replaced by serum-free DMEM glutamax 1% P/S, to trigger ependymal differentiation in vitro (differentiation day 0).

Cell lines

Flp-in TRex-DLD-142 and HEK293FT cells were grown in DMEM (Corning) containing 10% FB Essence (VWR Life Science Seradigm) and 100U/mL of penicillin and streptomycin. All cells were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2 and atmospheric oxygen.

Centrinone treatment to deplete parent centrioles

Centrinone treatment was carried out as previously described17. Briefly, centrinone was added on day 2 of the proliferation phase at a final concentration of 0.6 μM. Centrinone was washed out 3 times in PBS at the end of the proliferation phase just before trypsinization and re-plating at high confluence for MCC differentiation (differentiation day 1).

siRNA knockdown

siRNA transfections were performed on trypsinized cells in suspension at differentiation day 1 using the Jetprime (Polyplus). 1.3 × 106 ependymal cells were transfected with 100 nM of either ON-TARGETplus Non-targeting siRNA (Dharmacon, Cat no. D-001810–01-05) or ON-TARGETplus Deup1 siRNA (Dharmacon, Cat no. L-042708–01-0005) and seeded onto 4 coverslips. Cells were fixed and analyzed 4 days after serum starvation (differentiation day 4).

Cloning and transfection

Deup1 full-length and exons 8–12

The full-length mouse Deup1 ORF or Deup1 exons 8–12 were cloned into a pcDNA5/FRT/TO vector. A Myc tag was inserted on the 3’ end of the cDNA sequence. DEUP1 transgenes were inserted into a single genomic locus in the Flp-in TRex-DLD-1 cells using FLP-mediated recombination. DLD-1 cells were seeded at 2 × 105 cells per well in a 6-well plate. The next day a transfection mixture of 100 uL Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Cat. # 31985070), 3 uL of X-tremeGene HP (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. 6366236001), 100 ng of pcDNA5 plasmid and 900 ng of POG44 (Flp recominase) was prepared and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes and then added drop-wise to each well. Two days later, cells were selected with 50 ug/mL of Hygromycin B (ThermoFisher, cat. no. 10687010). HEK293FT were transfected using PEI reagent as previously described42.

Morpholino experiments

For the morpholino validation experiments, morpholino-targetable Cep63 was PCR amplified from Xenopus laevis cDNA and cloned into the PCS2+ vector with a C-terminal EGFP. Morpholino-targetable Deup1 was produced by annealing two complementary primers consisting of the Deup1 morpholino sequence and cloned into PCS2+ vector with a C-terminal EGFP. Plasmids were linearized and mRNA was made from both of these constructs using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE Sp6 Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher, AM1340) and purified using an RNA isolation kit (QIAGEN).

Embryo Injections

Xenopus laevis embryos were obtained by standard in vitro fertilization protocols approved by Northwestern University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Morpholinos were designed targeting Xenopus Deup1 and Cep63 (Gene Tools, LLC). The Deup1 morpholino had the sequence 5’-GGCTTTCAGTGTCTGTTTGCATTTC-3’ and the Cep63 morpholino had the sequence 5’-CATTCCGTTTTCTCAACACACTGCA-3’. Embryos were injected with 10–20 ng of morpholino and with Dextran-Cascade Blue (Thermo Fisher, D1976) as a tracer at the two to four-cell stage. Standard scrambled morpholino controls were used in all morpholino experiments (Gene Tools, LLC). For morpholino validation experiments, the morpholino-targetable Deup1-GFP or Cep63-GFP RNAs were injected 4 times in two-to four cell stage embryos, and then the corresponding morpholinos were injected as mosaics in two of the four blastomeres at the 4-cell stage with membrane RFP or dextran-blue as tracers.

Processing of cells and tissues for immunofluorescence microscopy

Brains for ex vivo imaging of ependymal cells

For centriole quantification, adult mice were perfused with 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and dissected brains were post-fixed in 1% PFA overnight at 4°C. The next day, brains were washed 3x in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature, then embedded in 3% low-melting-point agarose. Brains were cut coronally into 100 μm sections, using a vibratome (Leica Biosystems). Brain sections were stained overnight at 4°C in primary antibodies diluted in 10% donkey serum (in PBST; 1x PBS, 0.5% Triton X-100). The next day sections were washed 3 x with PBST at room temperature then incubated in secondary antibodies and 1 μg/ml 40,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) diluted in 10% donkey serum at 4°C. The following day sections were washed 3 x with PBST at room temperature then mounted onto slides with Fluoromount G mounting media. (SouthernBiotech).

To stain different phases of centriole amplification, lateral brain ventricles from P2-P6 pups were first pre-permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 BRB medium (80mM PIPES, 1mM MgCl2, 1mM EGTA) for 2 min before fixation. Tissues were then fixed in methanol at −20 °C for 10 min. Samples were pre-blocked in 1× PBS with 0.2% Triton X-100 and 10% FBS before incubation with primary and secondary antibodies. Tissues were counterstained with DAPI (10 μg/ml, Sigma) and mounted in Fluoromount (Southern Biotech).

mTEC cultures

Membranes were incubated in microtubule stabilization buffer (30% glycerol, 100 mM PIPES, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgSO4) for 60 seconds, followed by fixation in 4% PFA for 10 minutes at room temperature. Membranes were washed with PBST (1x PBS, 0.1% Triton X-100) 3 x for 5 minutes each. Membranes were then blocked at room temperature for an hour. Membranes were cut into quarters and incubated with primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer for an hour at room temperature. Membranes were washed 3 x in PBST for 5 minutes each and incubated with secondary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer for 45 minutes at room temperature. Membranes were incubated with DAPI (10 μg/ml, Sigma) diluted in PBS for 1 minute at room temperature and mounted onto slides with ProLong Gold Antifade (Invitrogen).

Ependymal cell cultures

Cells were grown on 12-mm glass coverslips as described above and fixed for 10 minutes in either 4% PFA at room temperature or 100% ice-cold methanol at −20°C. Cells were fixed on differentiation day 2 – 6 for analysis of centriole amplification and on differentiation day 10 for analysis of differentiated cells. Samples were pre-blocked in PBS with 0.2% Triton X-100 and 10% FBS before incubation with primary and secondary antibodies. Cells were counterstained with DAPI (10 μg/ml, Sigma) and mounted in Fluoromount (Southern Biotech).

Xenopus

Embryos in the morpholino validation experiment were fixed in 3% PFA in PBS for 2 hours, washed in PBST (1X PBS and 0.1% Triton X-100) and then stained with phallodin-647 (Invitrogen). Embryos used for centriole analysis were fixed in 100% ice-cold methanol for 48 hours at −20°C. Embryos were rehydrated in a methanol series, washed in PBST, and blocked in 10% heat-inactivated goat serum for 2 hours. Mouse Anti-centrin (EMD Millipore 04–1624) and rabbit anti–ZO-1 (61–7300; Invitrogen) primary antibodies were used, followed by Cy-2 and Cy-3-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.).

Ciliary beat frequency

Cells were seeded onto a 4 well glass bottom slide (Ibidi) and imaged at differentiation day 7 on a 3i Live-Cell Spinning Disk Confocal (Zeiss) using a 32x Air objective with 1.6x magnification. Cells were imaged using widefield light with a 3 ms exposure time at 330 frames/second for 10 seconds. The number of beats per second was measured using previous methods43. Briefly, a 16×16 pixel region of interest was selected containing a single beating cilium, and changes in intensity over time was counted using the ImageJ z-axis profile tool. The total number of beats over a 3–5 second interval was measured and used to calculate the average beats per second for each cell. 1–3 regions were measured for each cell and used to plot the average beat frequency for each cell.

Cilia length measurement

Cilia length was measured from scanning electron microscopy images of MCCs in the mouse trachea. Length was measured using ImageJ software. Three cilia per cell were measured and the average length per cell for each mouse plotted.

Antibodies

Staining of cells and tissues was performed with the following primary antibodies: Goat polyclonal anti-γTubulin-55544 (homemade, raised against the peptide CDEYHAATRPDYISWGTQEQ), Mouse monoclonal anti-Centrin, clone 20H5 (Millipore, 04–1624, 1:3000), Rabbit polyclonal anti-CEP164 (EMD Millipore, ABE2621, 1:1000), Mouse monoclonal Acetylated-alpha tubulin (Cell Signaling Technologies, 12152, 1:1000), Rat polyclonal anti-ZO-1 (ThermoFisher Scientific, 14–9776-82, 1:1000), Rabbit polyclonal anti-DEUP1 #1 (1:1000) (homemade, raised against the full length protein, see below), Rabbit anti-DEUP1 (1:2000) (homemade, raised against the peptide TKLKQSRHI)17; Mouse anti-GT335 (1:500, Adipogen); Mouse anti-SAS6 (1:750, Santa Cruz); Rabbit anti-Pericentrin (1:2000, Covance); Rabbit anti-CEP63 (1:500, Proteintech). Secondary antibodies were conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488, 555 or 650 (Life Technologies).

Custom-made Deup1 antibodies

Full-length mouse Deup1 was cloned into a pET-28M bacterial expression vector (EMD Millipore) containing a C-terminal 6-His tag. Recombinant protein was purified from Escherichia coli (Bl21Rosetta) cells using Ni-NTA beads (QIAGEN) and 2 mg was used for immunization into 2 rabbits (ProSci Incorporated). Rabbit immune sera were affinity-purified. Purified antibodies were directly conjugated to AlexaFluor 555 and AlexaFluor 650 fluorophores (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for use in immunofluorescence. A rabbit anti-Deup1 (1:2000) antibody raised against the peptide TKLKQSRHI was previously described17.

Microscopy

Immunofluorescence microscopy

For centriole counting in mouse tracheal epithelial cells and brain sections, cells were imaged using a Zeiss LSM700 confocal microscope controlled by ZEN software. Images were collected using a Zeiss 63× 1.4 NA oil objective at 0.3 μm z-sections using Zeiss immersion oil (N=1.518).

For centriole counting in cultured ependymal cells and DLD-1 cells, cells were imaged using a DeltaVision Elite system (GE Healthcare) and a scientific CMOS camera (pco.edge 5.5). The equipment and acquisition parameters were controlled by SoftWoRx suite (GE Healthcare). Images were collected using an Olympus 60× 1.42 NA objective at 0.2μm z-sections using Applied Precision immersion oil (N=1.516). For amplification phase imaging in cultured ependymal cells, cells were imaged using an upright epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axio Observer.Z1) controlled by ZEN software. Images were collected using a Zeiss Apochromat 63× 1.4 NA oil objective and a Zeiss Apotome with an H/D grid at 0.24 μm z-sections using Zeiss immersion oil (N=1.518). For amplification phase imaging of brain cells, cells were imaged using an inverted LSM 880 Airyscan Zeiss microscope with 440, 515, 560 and 633 laser line controlled by ZEN software. Images were collected using a Zeiss Apochromat 63× 1.4 NA oil objective at 0.24 μm z-sections using Zeiss immersion oil (N=1.518).

All microscopy on Xenopus was performed on a laser-scanning confocal microscope (A1R; Nikon) using a 60× 1.4 NA oil Plan-Apochromat objective lens. Embryos were imaged at room temperature in Fluro-gel (Electron Microscopy Sciences) using the Nikon Elements software. Images were analyzed for centriole number and mean fluorescent intensity using ImageJ. Data were analyzed and bar graphs were generated in Excel (Microsoft).

Live cell imaging

Cultured cells between differentiation day 2 and differentiation day 6 were filmed using an inverted spinning disk Nikon Ti PFS microscope equipped with oil-immersion ×63 1.32 NA and ×100 1.4 NA objectives, an Evolve EMCCD Camera (Photometrics), dpss laser (491 nm, 25% intensity, 70ms exposition), appropriate filter sets for DAPI/FITC/TRITC, a motorized scanning deck and an incubation chamber (37 °C; 5% CO2; 80% humidity). Images were acquired with Metamorph Nx using 40-minute time intervals. Image stacks were recorded with a z-step of 0.7 μm. In centrinone treated cells, the presence or absence of parent centriole was monitored using the Cen2-GFP signal at the beginning of centriole amplification.

Scanning electron microscopy

The Johns Hopkins microscopy facility performed scanning electron microscopy. Briefly, tracheas were cut open lengthwise and fixed overnight at 4°C in a buffer of 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 100 mM sodium cacodylate, 3 mM MgCl2, pH 7.2. Following a rinse in a buffer of 3% sucrose, samples were post-fixed for 1.5 hours on ice in the dark with 2% osmium tetroxide in 100 mM cacodylate buffer containing 3 mM MgCl2. Samples were rinsed in dH2O and dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol to 90%. Dehydration was continued through 100% ethanol, then passed through a 1:1 solution of ethanol:HMDS (Hexamethyldisiloxazne Polysciences) followed by pure HMDS. Samples were then placed in a desiccator overnight to dry. Tracheal pieces were attached to aluminum stubs via carbon sticky tabs (Pella), and coated with 40 nm of AuPd with a Denton Vacuum Desk III sputter coater. Stubs were viewed on a Leo 1530 FESEM operating at 1 kV and digital images captured with Smart SEM version 5.

TEM and Correlative light and electron microscopy (CLEM)

CLEM was done as previously described12. Briefly, primary CENT2-GFP ependymal progenitors were grown in 0.17-mm thick glass dishes with imprinted 50 μm relocation grids (Ibidi). At differentiation day 3–6, cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 10 min and ependymal progenitors undergoing A-phase or G-Phase were imaged for CENT2-GFP and DAPI, in PBS, with an upright epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axio Observer.Z1). Coordinates on the relocation grid of the cells of interest were recorded. Cells were then processed for transmission electron microscopy. Briefly, cultured cells were treated with 1% OsO4, washed and progressively dehydrated. The samples were then incubated in 1% uranyl acetate in 70% methanol, before final dehydration, pre-impregnation with ethanol/epon (2/1, 1/1, 1/2) and impregnation with epon resin. After mounting in epon blocks for 48 h at 60 °C to ensure polymerization, resin blocks were detached from the glass dish by several baths in liquid nitrogen. Using the grid pattern imprinted in the resin, 50 serial ultra-thin 70-nm sections of the squares of interest were cut on an ultramicrotome (Ultracut EM UC6, Leica) and transferred onto formvar-coated EM grids (0.4 × 2 mm slot). The central position of the square of interest and DAPI staining were used to relocate and image the cell of interest using a Philips Technai 12 transmission electron microscope.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and qPCR

Total RNA from cells and tissues was extracted with Trizol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s protocol. SuperScriptIV reverse transcriptase (ThermoFisher Scientific) was used for cDNA synthesis. The cDNA was then used for quantitative real-time PCR (BioRad), using SYBR Green qPCR mastermix reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific). The following primers were used:

Deup1 (deleted exons)

For: 5’- GCC AGA TGT AGA CAT TTC TTG GCA TGG −3’

Rev: 5’- CCC ACC TCC TGG CCT TT −3’

Deup1 (exons 10–12):

For: 5’- TAC GTC TTC CAG AGC CAG C −3’

Rev: 5’- CAG GAA GTG CTG TGC AGC −3’

Deup1 (exons 9–10):

For: 5’- GAA TTA AGC AAG GCT GTG GAC T −3’

Rev: 5’- CTC TGG AAG ACG TAT GCC CC −3’

Cep63 (exons 6–8):

For: 5’- ATC AGA CCT ACA GTT CTG CC −3’

Rev: 5’- CTG ACT TAG AAT CTC CTT ATG CTC −3’

Cep63 (exons 13–14):

For: 5’- GCA GGA GGA ATT AAG CAG ACT −3’

Rev: 5’- CTG TCG GAA TTC CTC TAT TTT TCC AG −3’

GAPDH:

For: 5’- AAT GTG TCC GTC GTG GAT CTG A −3’

Rev: 5’- GAT GCC TGC TTC ACC ACC TTC T −3’.

All samples were normalized to GAPDH (ΔCt). The relative fold change in mRNA expression as quantified using the 2−ΔΔCt method comparing experimental samples to controls. All data was then normalized to the average value for the control samples.

Western blotting

For immunoblot analyses, protein cells were lysed in 2x sample buffer (125mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 20% glycerol, 4% SDS, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 4% β-mercaptoethanol). Samples were then separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane with a Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and blocked in 5% milk for one hour at room temperature. Membranes were incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with primary antibodies diluted in 5% milk, washed 3 x with TBST (1x TBS/1% Tween-20) and then incubated with a HRP-conjugated secondary antibody diluted in 5% milk. Blots were washed 3 x in TBST for 5 minutes each. Blots were incubated with either SuperSignal West Pico PLUS or Femto enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (ThermoFisher Scientific) for 1 minute and imaged using a G:Box (SynGene). The following primary antibodies were used: YL1/2 (rat anti–α-tubulin, 1:3,000; Pierce Antibodies), rabbit anti-Deup1 #2 (1 μg/ml custom made). The following secondary antibodies were used: anti-rat or anti-rabbit IgG linked to HRP (Cell Signaling Technologies).

Quantification of centriole number in fixed samples

Regions were selected that contained a high density of MCCs. >3 fields of view were selected per sample, and all cells within those fields of view were counted until the number of quantified cells across all fields exceeded 30. Cells where individual centrioles could not be resolved were excluded from our analysis. Centrin or CEP164 foci within each cell were quantified using three-dimensional image stacks and the multipoint tool in ImageJ.

Quantification of centriole number using CENT2-GFP movies

The total number of centrioles was calculated during the disengagement phase when the CENT2-GFP signal was dispersed. The entire volume of the cell was used for the quantification. Image quantification was performed using ImageJ.

Centriole Length measurement

Centriole length was measured using TEM pictures. Only centrioles whose axis was parallel to the cut plane were analyzed.

Quantification of fluorescence intensity

SAS6 intensity measurement

Identically sized concentric rings were drawn by hand around the CENT2-GFP positive parent centrioles and used as region of interest (ROI). An identically sized concentric ring was used for background measurement. Cells where the SAS6 signal of the two parent centrioles overlapped were excluded. Younger and older parent centrioles were discriminated by staining the primary cilium (GT335+) that is nucleated by the older parent centriole. SAS6 asymmetry was measured as the background subtracted signal (raw integrated density) from the young parent centriole divided by the background subtracted signal for the older parent centriole. To calculate the total SAS6 intensity around the parent centrioles the background subtracted signal for the older and younger parent centrioles was summed together and divided by the background. Image quantification was performed using ImageJ.

PCNT cloud intensity measurement

The boundary of the PCNT cloud was determined using a semi-automated segmentation process. Briefly, PCNT staining for each cell was normalized using a Gaussian blur with a radius of 3. Then, the automatic “Otsu” threshold was applied. PCNT intensity (raw integrated density) was measured within the resulting mask and divided by the background signal measured in a concentric ring of 4.24 μm2 within the same cell. Image quantification was performed using ImageJ.

Procentriole localization compared to PCM cloud

The boundary of the PCNT cloud was determined using the semi-automated segmentation process detailed above. The resulting mask was used to identify if centrioles (marked by SAS6) were inside or outside the PCNT cloud. Centrioles on the edge of the cloud were considered to be inside. Image quantification was performed using ImageJ.

CEP63 intensity measurement

The boundary of the CEP63 staining was determined using a semi-automated segmentation process detailed above. CEP63 intensity (raw integrated density) was measured within the resulting mask and divided by the SAS6 intensity within the same mask to normalize for biases that may arise from differences in the number of amplified procentrioles in each cell.

DEUP1 variant

The human DEUP1 variant was identified using the gnomAD database (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/variant/11–93141472-C-T).

Statistics and Reproducibility

Each experiment was repeated independently with similar results. P values were calculated using an unpaired, two-tailed, Welch’s t-test across averages of 3 independent experiments. Quantification was semi-automated using a script detailed in the methods section for the following data: delimitation of the PCNT cloud border (for Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. 7b) and quantification of PCNT and CEP63 area and/or intensity (for Supplementary Fig. 5b, Supplementary 7c, d). Otherwise quantification was performed manually, and there are several levels of redundancy and quality control in our data that give us a high degree of confidence in the lack of a substantial difference in centriole number between control and Deup1−/− animals. First, for the initial experiment we performed in the Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− multiciliated mTECs, the experimenter was blinded to the genotypes when quantifying (Fig. 2a). The data from the following repeats matched what we observed in the initial experiment. Second, centriole number has been independently quantified on immunostained control and Deup1−/− multiciliated ependymal cells in both the Holland and Meunier labs and the results of this analysis were very similar. Third, the quantification of centriole number in cultured multiciliated ependymal cells performed with fixed imaging in the Holland lab (Supplementary Fig. 2a) was highly similar to that obtained from a parallel analysis performed in the Meunier lab on live cells expressing the CENT2-GFP marker (Fig. 6b). Finally, the analysis of centriole number in Xenopus multiciliated cells was performed in the Mitchell lab and reached similar conclusions to what we had observed in mouse multiciliated cells. As an additional quality check, re-quantification of centriole number in the ependymal cells in vivo was performed, in which the quantifier was blinded to genotype (Figure 2c and Supplemental Figure 5h). Importantly, the differences in centriole number between the four genotypes in this analysis are comparable to the original quantification.

Data availability statement

Source data for Figs. 1a, 2a, 2c, 3a, 5a, 5c, 5e, 5f, 5g, 6b, 6d, and Extended Data. 1b, 1c, 2a, 2c, 2d, 3a, 3b, 3c, 3e, 3f, 5a, 5b, 5c, 5d, 5f, 5h, 6a, 6c and 7b, 7c and 7d have been provided in the file Statistics Source Data. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1: Deup1−/− mice lack Deup1 mRNA and detectable protein.

(a) A Deup1 knock-out was generated by replacing a region from within exon 2 to within exon 7 of the Deup1 gene with a LacZ reporter followed by a polyA sequence. (top) Schematic representation of the Deup1 gene and (bottom) mRNA structure in Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− mice.

(b) RT-qPCR analysis of Deup1 mRNA levels in postnatal day 5 brain tissue. Deleted (Del.) exons denote primers designed to amplify exons 2–3 that are deleted in Deup1−/− mice. The average of Deup1+/+ samples was normalized to 1. n = 3 mice/genotype. Bars represent mean +/− SD.

(c) RT-qPCR analysis of testes in 2–5-month-old mice using 3 different primer sets. The average of Deup1+/+ samples was normalized to 1. n ≥ 3 mice/genotype. Bars represent mean +/− SD.

(d) Immunofluorescence images of mTECs at air-liquid interface (ALI) day 4. Scale bars represent 10 μm.

(e) Western blot of lysates from mTECs at ALI day 3 and 5, and two different ependymal cell cultures differentiated for 8 days. Membranes were probed with antibodies against DEUP1 and α-tubulin was used as a loading control. Full blot shown in Source Data.

(f) Immunoblot of DLD1 cells expressing doxycycline (dox) inducible mmDEUP1-Myc transgene. Membranes were probed with antibodies against DEUP1 or Myc. Arrow denotes the mmDEUP1-Myc protein and the asterisk shows endogenous Myc. Full blot shown in Source Data.

(g) Immunoblot of HEK293 cells expressing either full-length (F.L.) or exons 8–12 (Ex 8–12) of mmDEUP1 in the presence or absence of the proteasome inhibitor, MG132. MG132 was used to enable the detection of unstable protein fragments. Membranes were probed with antibodies against DEUP1 or Myc. α-tubulin was used as a loading control. Arrow denotes the full-length mmDEUP1-Myc protein, arrowhead denotes the exon 8–12 mmDEUP1-Myc protein and the asterisk shows endogenous Myc. Full blot shown in Sourc Data.

Extended Data Fig. 2: DEUP1 is not required for centriole amplification.

(a) Quantification of CEP164 foci which marks the mature basal bodies in control or Deup1−/− ependymal cells. The total number of cells analyzed per genotype is indicated. n = 3 mice/genotype. P values, unpaired, two-tailed, Welch’s t-test. n.s. = not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Bars represent mean +/− SD.

(b) Representative images of mature centrioles in Deup1+/+ or Deup1−/− ependymal cells stained with an antibody against CEP164. Scale bars represent 10 μm.

(c) Quantification of Deup1-GFP intensity in control or Deup1 morpholino treated Xenopus epithelial cells. Note, the Deup1 MO efficiently silenced expression of an mRNA encoding a morpholino-targetable fragment of Deup1 fused to GFP in Xenopus MCCs. n ≥ 5 embryos per genotype. The total number of cells analyzed per condition is indicated. P values, unpaired, two-tailed, Welch’s t-test. * = p ≤ 0.05. Bars represent mean +/− SD.

(d) Quantification of centriole number in control or Deup1 morpholino treated Xenopus epithelial cells. Points represent the average number of centrioles per embryo. n ≥ 5 embryos per genotype. The total number of cells analyzed per condition is indicated. P values, unpaired, two-tailed, Welch’s t-test. n.s. = not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Bars represent mean +/− SD.

(e) Representative immunofluorescence images from control or Deup1 morpholino treated Xenopus epithelial cells stained with tight junction marker, ZO1, and centriole marker, Centrin. Scale bars represent 10 μm

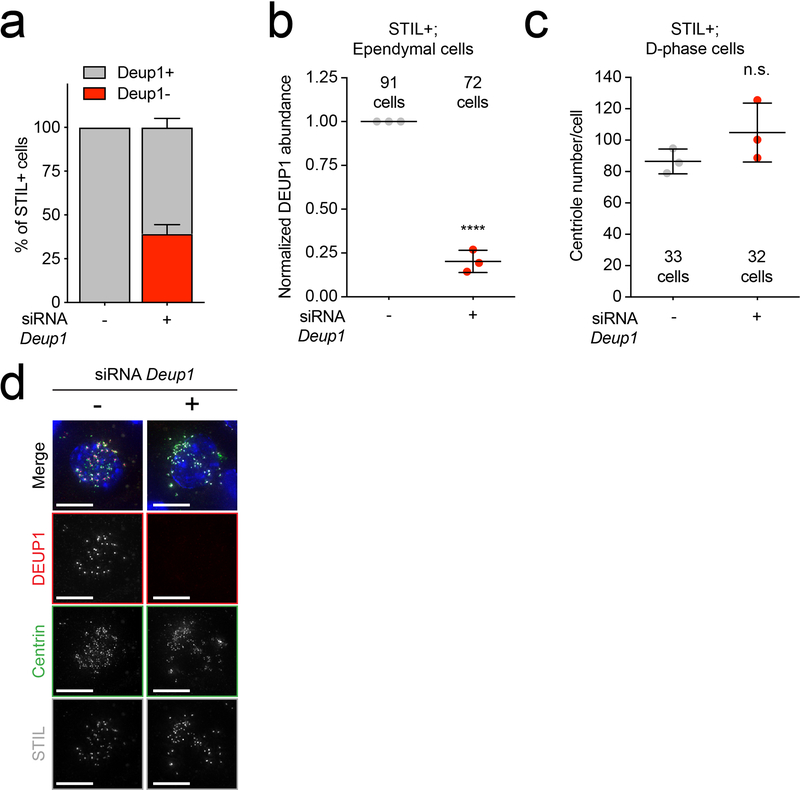

Extended Data Fig. 3: Deup1 siRNA does not suppress centriole amplification in MCCs.

(a) Quantification of control or Deup1 siRNA treated cells undergoing centriole amplification that contained (DEUP1+) or lacked (DEUP1-) DEUP1 foci. To identify cells in the process of centriole amplification we immunostained for STIL, which localizes to immature procentrioles but is absent from mature basal bodies. n = 3 cultures/genotype.

(b) Quantification of the intensity of DEUP1 signal in STIL+/DEUP1+ controls or STIL+/DEUP1- siRNA-treated cells. n = 3 cultures/genotype. The average intensity for the control siRNA sample was normalized to 1 for each experiment. n = 3 mice/genotype. P values, one sample t-test compared to a mean of 1. **** = p ≤ 0.0001.

(c) Quantification of centriole number in control and Deup1 siRNA-treated cells. Only STIL+ cells were quantified so that DEUP1 depletion could be monitored, and only cells depleted for DEUP1 (assessed by immunostaining) in the siRNA condition were quantified. n = 3 cultures/genotype. P values, unpaired, two-tailed, Welch’s t-test. n.s. = not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

(d) Representative images of control ependymal cells and cells with siRNA-mediated depletion of DEUP1. Scale bars represent 10 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 4: Procentrioles form in the vicinity of parent centrioles in cells that lack deuterosomes.

(a) Quantification of the ratio of SAS6 intensity at the younger parent centriole (YPC) compared to the older parent centriole (OPC) in ependymal cells in vivo (P2-P6) during A-phase. GT335 staining was used to mark the cilium that forms from the older parent centriole. n = 3 mice/genotype. P values, one sample t-test compared to the value of 1, which represents identical SAS6 intensity levels at the YPC and OPC. *** = p ≤ 0.001, **** = p ≤ 0.0001.

(b) Quantification of SAS6 intensity on parent centrioles in Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− ependymal cells in amplification phase in vivo (P2-P6). The SAS6 signal associated with the two parent centrioles was summed together and normalized to background SAS6 staining of the same cell. n = 3 mice/genotype. P values, unpaired, two-tailed, Welch’s t-test. **** = p ≤ 0.0001. All bars represent mean +/− SD.

(c) Serial EM images of a Deup1−/− ependymal cell in the growth phase from basal (Z1) to apical (Z10). Note the increase in centriole amplification on, and in the vicinity of, the parental centrioles. Bottom right shows a schematic representation of the relative position of procentrioles formed by the parent centrioles. Scale bar represents 500 nm.

Extended Data Fig. 5: CEP63 modestly affects centriole amplification in Deup1−/− MCCs.

(a) RT-qPCR analysis of Cep63 mRNA levels in Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− mTECs. n = 3 mice/genotype. The average of Deup1+/+ samples was normalized to 1.

(b) Quantification of CEP63 protein levels in ependymal cells in the amplification phase. To account for differences in the number of procentrioles present in each cell, CEP63 levels were normalized to the abundance of the procentriole marker SAS6. n = 3 cultures/genotype.

(c) RT-qPCR analysis of Cep63 mRNA levels in testes and mTECs from Cep63+/+ and Cep63T/T mice using two different primer sets. The average of Cep63+/+ samples was normalized to 1. n = 3 mice/genotype.

(d) Quantification of CEP164 foci which marks basal bodies in cultured mature ependymal cells. Data from Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− cultures are from Extended Data 2a and shown for comparison. n = 3 cultures/genotype.

(e) Representative images of mature basal bodies using an antibody against CEP164 in mature ependymal cells.

(f) Quantification of CEP164 foci in mature mTECs. Data from Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− cultures are from Fig. 2a and shown for comparison. n = 3 cultures/genotype.

(g) Representative images from mature mTECs. DAPI marks the nuclei, acetylated-tubulin (AcTub) marks cilia, ZO-1 marks tight junctions and CEP164 stains basal bodies.

(h) Quantification of the basal body marker CEP164 foci in adult brain sections. Data from Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− mice are from Fig. 2c and shown for comparison. n = 3 mice/genotype.

(i) Representative images of ependymal cells in adult brain sections. DAPI marks the nuclei, ZO-1 marks tight junctions and CEP164 stains basal bodies.

(j) Scanning electron micrographs of trachea from control or Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T adult mice. All scale bars represent 10 μm. All bars represent mean +/− SD. All P values are from unpaired, two-tailed, Welch’s t-test. n.s. = not statistically significant (p > 0.05), * = p ≤ 0.05.

Extended Data Fig. 6: Deup1 and Cep63 are dispensable for centriole amplification in Xenopus.

(a) Quantification of centriole number in Xenopus epithelial cells treated with Cep63 or Deup1 and Cep63 morpholinos. Data from control and Deup1 morpholinos are from Extended Data 2d and shown for comparison. Points represent the average number of centrioles per cell in one embryo. n ≥ 5 embryos/genotype. The total number of cells analyzed per condition is indicated. P values, unpaired, two-tailed, Welch’s t-test. n.s. = not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Bars represent mean + SD.

(b) Representative immunofluorescence images from control, Cep63 or Deup1 and Cep63 morpholino treated Xenopus epithelial cells stained with tight junction marker, ZO1, and centriole marker, Centrin. Scale bars represent 10 μm.

(c) Quantification of Cep63-GFP intensity in control and Cep63 morpholino-treated Xenopus epithelial cells. Note, the Cep63 MO efficiently silenced expression of an mRNA encoding a morpholino-targetable Cep63 fused to GFP in Xenopus MCCs. n = 3 embryos/genotype. The total number of cells analyzed per condition is indicated. P values, unpaired, two-tailed, Welch’s t-test. * = p ≤ 0.05. Bars represent mean + SD.

(d) Quantification of the percent of centrioles with normal or abnormal structure in Deup1+/+, Deup1−/− and Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T ependymal cells. n > 30 cells/genotype. The total number of centrioles analyzed per genotype is indicated.

(e) Representative TEM images of normal and abnormal centrioles in Deup1+/+, Deup1−/− and Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T ependymal cells. Scale bar represents 100 nm.

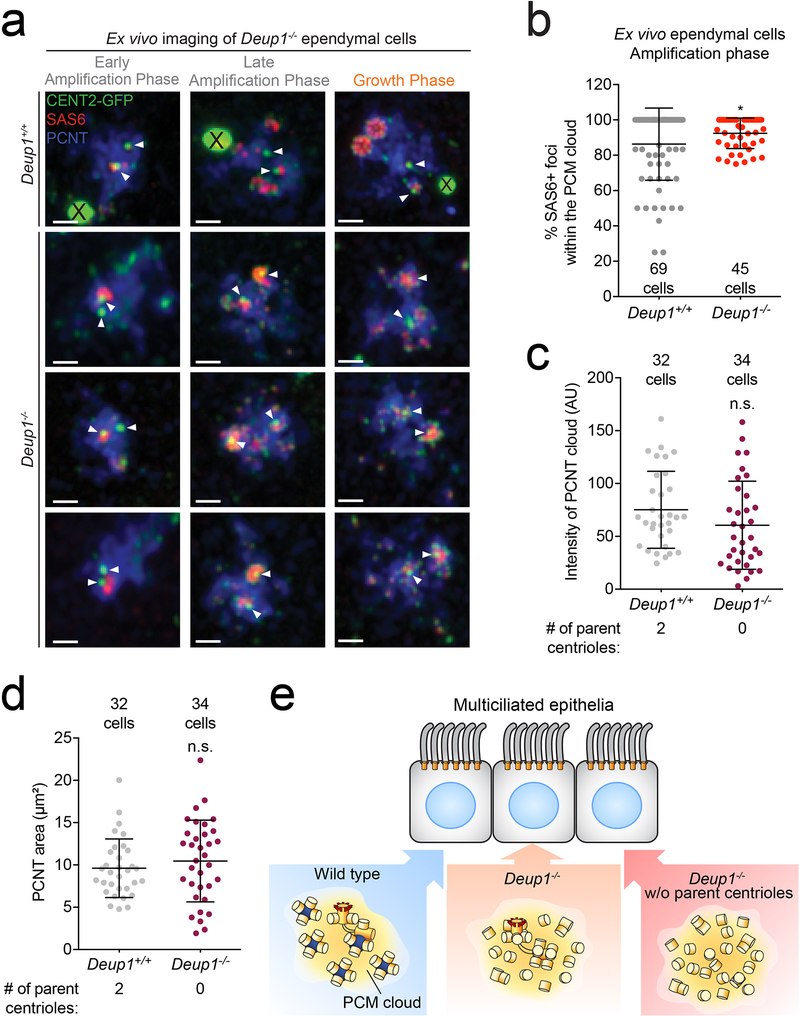

Extended Data Fig. 7: Procentrioles are amplified within a cloud of PCNT in both Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− cells with or without parent centrioles.

(a) Immunofluorescence images of Centrin 2-GFP-expressing Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− ependymal cells. Brain sections were stained with antibodies against the procentriole protein SAS6 and pericentriolar material protein PCNT. X marks Centrin 2-GFP aggregates. Arrowheads point to parent centrioles. Scale bars represent 1 μm.

(b) Quantification of the percent of SAS6+ foci observed within the PCM cloud in Deup1+/+ and Deup1−/− ependymal cells during the amplification phase in vivo. n = 3 mice/genotype. Each point represents a single cell. The total number of cells analyzed per genotype is indicated. P values, unpaired, two-tailed, Welch’s t-test. * = p ≤ 0.05. Bars represent mean +/− SD.

(c) Quantification of the intensity of the PCNT cloud in Deup1+/+ ependymal cells with 2 parent centrioles and in Deup1−/− ependymal cells with 0 parent centrioles during the amplification phase in vitro. n = 3 cultures/genotype. The total number of cells analyzed per genotype is indicated. P values, unpaired, two-tailed, Welch’s t-test. n.s. = not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Bars represent mean +/− SD

(d) Quantification of the area of the PCNT cloud in Deup1+/+ ependymal cells with 2 parent centrioles and in Deup1−/− ependymal cells with 0 parent centrioles during the amplification phase in vitro. n = 3 cultures/genotype. The total number of cells analyzed per genotype is indicated. P values, unpaired, two-tailed, Welch’s t-test. n.s. = not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Bars represent mean +/− SD.

(e) Model of centriole amplification in MCCs. (Blue) Wild type cells amplify centrioles on the surface of deuterosomes and the parent centrioles. (Orange) DEUP1 knockout cells achieve the correct number of centrioles through the massive production of centrioles on the surface and in the vicinity of parent centrioles. (Red) MCCs that lack parent centrioles and deuterosomes amplify the correct number of centrioles within the confines of a PCM cloud.

Supplementary Material

(a) Table showing the frequency of mice with the indicated genotype. Genotyping was performed between p4–p7.

Live imaging of cilia beating in a control ependymal cell. Movies were imaged at 330 frames per second; displayed at 20 frames per second.

Live imaging of cilia beating in a Deup1−/− ependymal cell. Movies were imaged at 330 frames per second; displayed at 20 frames per second.

Live imaging of cilia beating in a Deup1−/−; Cep63T/T ependymal cell. Movies imaged at 330 frames per second; displayed at 20 frames per second.

Live imaging of centriole amplification in a Centrin 2-GFP Deup1−/− ependymal cell with two parent centrioles. Cell is shown in Fig. 6a. One frame captured every 40 min; displayed at 1 frame per second. A, G and D-Phase are depicted in grey, orange and green, respectively. Arrows indicate parent centrioles. “X” marks a Centrin 2-GFP aggregate.

Live-cell imaging of centriole amplification in a Centrin 2-GFP Deup1+/+ ependymal cell shown in Fig. 3b. One frame captured every 40 min; displayed at 1 frame per second. A, G and D-Phase are depicted in grey, orange and green, respectively. Arrows indicate parent centrioles. “X” marks a Centrin 2-GFP aggregate.

Live imaging of centriole amplification in a Centrin 2-GFP Deup1−/− ependymal cell treated with centrinone to deplete both of the parent centrioles. Cell is shown in Fig. 6a. One frame captured every 40 min; displayed at 1 frame per second. Amplification phases (A, G or D-Phase) cannot be identified without parent centrioles. “X” marks a Centrin 2-GFP aggregate.

Serial section electron microscopy of a Centrin 2-GFP Deup1−/− ependymal cell treated with centrinone to deplete both of the parent centrioles. Cell is shown in Fig. 6e. The cell is in the amplification phase. Images are taken in 70-nm sections; displayed at 4 frames per second.

Serial section electron microscopy of a Centrin 2-GFP Deup1−/− ependymal cell treated with centrinone to deplete both of the parent centrioles. Cell is shown in Fig. 6e. The cell is in the growth phase. Images are taken in 70-nm sections; displayed at 4 frames per second.

Live imaging of centriole amplification in a Centrin 2-GFP Deup1−/− ependymal cell shown in Fig. 3b. One frame captured every 40 min; displayed at 1 frame per second. A, G and D-Phase are depicted in grey, orange and green, respectively. Arrows indicate parent centrioles. “X” marks Centrin 2-GFP aggregate.

Serial section electron microcopy of a Centrin 2-GFP control ependymal cell shown in Fig. 4b. The cell is in the growth phase. Images are taken in 70-nm sections; displayed at 4 frames per second.

Serial section electron microcopy of a Centrin 2-GFP Deup1−/− ependymal cell shown in Fig. 4c. The cell is in the growth phase. Images are taken in 70-nm sections; displayed at 4 frames per second.

3D rendering of the serial section electron microcopy data shown in Fig. 4c.

Acknowledgments