Abstract

Background

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a novel HIV prevention method whereby HIV-negative individuals take the drugs tenofovir and emtricitabine to prevent HIV acquisition. Optimal adherence is critical for PrEP efficacy. Chemsex describes sexual activity under the influence of psychoactive drugs, in the UK typically; crystal methamphetamine, gamma-hydroxybutyrate(GHB) and/or mephedrone. Chemsex drug use has been associated with increased HIV transmission risk among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (GBM) and poor ART adherence among people living with HIV. This study assessed whether self-reported chemsex events affected self-reported daily PrEP adherence among PROUD study participants.

Methods

The PROUD study was an open-label, randomised controlled trial, conducted in thirteen English sexual health clinics, assessing effectiveness of TruvadaⓇ-PrEP among 544 HIV-negative GBM. The study reported an 86% risk-reduction of HIV from daily PrEP. Participants were asked about chemsex engagement at follow-up visits. Monthly self-reports of missed PrEP tablets were aggregated to assess adherence between visits. Univariable and multivariable regression analyses were performed to test for associations between chemsex and reporting less than seven out of seven intended doses(<7/7ID) in the 7 days before and/or after last condomless anal intercourse(CAI).

Results

1479 follow-up visit forms and 2260 monthly adherence forms from 388 participants were included in the analyses, with 38.5% visit forms reporting chemsex since last visit and 29.9% follow-up periods reporting <7/7ID. No statistically significant associations were observed between reporting <7/7ID and chemsex (aOR=1.29 [95% CI 0.90–1.87], p = 0.168). Statistically significant associations were seen between reporting <7/7ID and participants perceiving that they would miss PrEP doses during the trial, Asian ethnicity, and reporting unemployment at baseline.

Conclusions

These analyses suggest PrEP remains a feasible and effective HIV prevention method for GBM engaging in chemsex, a practise which is prevalent in this group and has been associated with increased HIV transmission risk.

Keywords: Chemsex; Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP); Adherence; HIV; Gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (GBM); Prevention

Introduction

In November 2018, Public Health England (PHE) reported significant progress towards ending the HIV epidemic; the UNAIDS 90:90:90 targets had been met for England in 2017, and a 17% decline in new UK HIV diagnoses compared to 2016 (from 5,280 to 4,363) had been observed in both gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (GBM) and heterosexual groups (Nash S et al., 2018). The stepwise implementation of combination HIV prevention; condom provision, scale up of frequent HIV testing and prompt antiretroviral therapy (ART) after diagnoses, and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), has been identified as the primary drivers for the drop in HIV incidence in GBM. Despite these gains, just over half (53%) of all new HIV diagnoses in England in 2017 were among GBM, demonstrating that this group are disproportionately at risk of acquiring HIV (Nash S et al., 2018).

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is an innovative HIV prevention strategy for individuals at risk for HIV acquisition, such as GBM engaging in condomless anal intercourse (CAI) (McCormack et al., 2016, McCormack et al., 2016). Although PrEP is not yet routinely commissioned in England, it is available through the PrEP Impact Trial (Nash S et al., 2018; NHS England, 2017) and can be purchased online and by private prescription. PrEP's efficacy in reducing HIV incidence in GBM and heterosexuals has been documented widely (Baeten et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2018; (McCormack et al., 2016; Molina et al., 2015; Okwundu, Uthman & Okoromah, 2012) and in trials such as the PROUD study, an open-label, randomized controlled trial of 544 HIV-negative GBM, the reduction in HIV risk from daily PrEP was 86% (McCormack et al., 2016). Optimal adherence is critical to PrEP's efficacy in HIV prevention, in order to achieve protective drug levels in the blood (Desai, Field, Grant & McCormack, 2017; Fonner et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2018; Spinner et al., 2016) and consequently, studies reporting limited PrEP efficacy have detected low or no therapeutic drug levels, indicating poor adherence (Corneli et al., 2014; Grant et al., 2014; Haberer et al., 2013; Marrazzo et al., 2015; Van Damme et al., 2012).

Chemsex refers to the use of psychoactive drugs within a sexual context to enhance and facilitate sexual experiences (Public Health England, 2015). The international chemsex definition varies, but within the UK typically involves the use of one or more of the three drugs; crystal methamphetamine, gamma-hydroxybutyrate [GHB] and mephedrone. (Bourne, Reid, Hickson, Torres-Rueda & Weatherburn, 2015; Edmundson et al., 2018; Public Health England, 2015). Chemsex has been increasingly reported among UK GBM in recent years (Macfarlane, 2016; Ottaway, Finnerty, Buckingham & Richardson, 2017; Sewell et al., 2018; Tomkins, George & Kliner, 2019) but prevalence estimates vary considerably due to lack of a standardised definition of chemsex and lack of prevalence measurements among representative, national samples of GBM. Furthermore, much of the available literature on chemsex only uses reporting of drugs associated with chemsex as a proxy for chemsex behaviour (i.e. intentional sex under the influence of the psychoactive drugs crystal methamphetamine, gamma-hydroxybutyrate [GHB], mephedrone) and does not assess event-level data. (Edmundson et al., 2018; Sewell et al., 2018).

Chemsex drug use has been associated with a number of harms including; sexual and other behaviours carrying HIV and hepatitis C risk (such as CAI, group sex and multiple partners, fisting and injecting) (Bourne et al., 2015; Daskalopoulou et al., 2017; Glynn et al., 2018; Hegazi et al., 2017; Maxwell, Shahmanesh & Gafos, 2019; Ristuccia, LoSchiavo, Halkitis & Kapadia, 2018; Tomkins et al., 2019), HIV diagnosis (Halkitis, Levy, Moreira & Ferrusi, 2014; Kenyon, Wouters, Platteau, Buyze & Florence, 2018; Pakianathan et al., 2018; White et al., 2019) and suboptimal adherence to ART among people living with HIV (Daskalopoulou et al., 2014; Perera, Bourne & Thomas, 2017; Stuart, 2013). The evidence on chemsex impacting ART adherence includes a systematic review published in 2017, reporting chemsex drug users as having 23% higher odds of ART non-adherence than non-chemsex drug users (OR 1.23, 95%CI 1.10–1.38, I2 0%, p = 0.372) (Perera et al., 2017). However as described earlier, the majority of studies on chemsex associated harms use chemsex drug use as a proxy, therefore attributing these harms to chemsex behaviours directly is problematic.

Evidence assessing the effect of chemsex behaviour and chemsex drug use on individuals’ PrEP adherence is limited and conflicting. One qualitative study among American PrEP-taking GBM reported associations between methamphetamine use and poor PrEP adherence, often in the context of group sex (Storholm, Volk, Marcus, Silverberg & Satre, 2017). Another American GBM study found similar associations with instances of “club drug” use (including GHB and methamphetamine) being correlated with missed PrEP doses on the same day (Grov, Rendina, John, & Parsons, 2018). Conversely, the same research also suggested that on average “club drug” users were no more likely to miss PrEP doses than non “club drugs” users (Grov, Rendina, John, & Parsons, 2018), and in another study among American GBM, methamphetamine use was shown not to be associated with decreased PrEP adherence (Hoenigl et al., 2019, Hoenigl et al., 2019). Interestingly, in an IPERGAY trial substudy, GBM reporting chemsex were more likely to report correct PrEP use during their most recent sexual encounter, which authors have explained by their additional finding that participants reporting chemsex also reported having a higher risk perception (Roux et al., 2018).

To our knowledge, there is currently no evidence assessing the impact of chemsex behaviours on PrEP adherence among GBM in England. This study explores the effect of reported chemsex episodes on daily PrEP adherence among PROUD study participants, to assess whether PrEP is likely to be an effective HIV prevention tool in periods around these high-risk events.

Methods

The PROUD study was an open-label, wait-listed, randomized controlled trial that was conducted in thirteen sexual health clinics in England, examining the real-world effectiveness of daily oral TruvadaⓇ as HIV PrEP. The study recruited 544 HIV-negative GBM between November 2012 and April 2014 who reported CAI in the previous 90 days and who considered they were likely to have CAI in the next 90 days. Participants were randomly assigned daily TruvadaⓇ either at study enrolment or after 12 months. Participants were followed up approximately quarterly with HIV/STI screening. In October 2014, interim analyses showed a large number of HIV infections in the deferred arm and evidence of PrEP being highly protective in the immediate arm, prompting a study design amendment whereby the X deferral arm participants still in the first 12 months of follow-up were given access to PrEP (McCormack, Dunn et al., 2016; . PROUD study design, baseline participant characteristics and results are described elsewhere (Dolling et al., 2016; Gafos, Brodnicki, et al., 2017; McCormack, Dunn et al., 2016;

From March 2015, participants were asked at each follow-up visit whether they had engaged in chemsex since last visit, on clinician-completed questionnaires. Specifically, these questionnaires asked, “Has the participant engaged in any of the following since their last visit: crystal meth, GHB/GBL or mephedrone immediately prior to, or during, sex (“chemsex”)”. Visit questionnaires answering yes to this question were used to define periods of chemsex engagement within the 90 days prior to follow-up visit dates (as follow-up visits were supposed to occur quarterly). Visit questionnaires were excluded from the analyses if they were from participants who were not currently taking PrEP or if the question on chemsex was not answered.

Participants were asked to complete monthly self-reported PrEP adherence questionnaires for the last month only; online, or on paper at follow-up visits. These adherence questionnaires asked participants how many days they missed PrEP tablets in the seven days before and seven days after last CAI (provided this had occurred in the preceding 30 days) and were used to assess adherence execution (Vrijens et al., 2012). Adherence questionnaires were eligible for our analyses if the completion date was within 90 days prior to the date on the visit questionnaire completion dates (and hence could be linked) and if the questions on missed PrEP were answered. We created a binary adherence outcome measure for participants reporting; taking all seven out of seven intended doses (7/7ID) in the seven days before and after last CAI, and participants reporting less than seven out of seven intended doses (<7/7ID) in the 7 days before and/or after last CAI. It was not possible to conduct a robust analysis with an adherence outcome for participants reporting missing ≥4 PrEP tablets in the 7 days before and/or after last CAI, as the sample was too small.

The adherence questionnaires were aggregated to calculate an overall PrEP adherence measure for each follow-up period. If participants reported 7/7ID in all monthly adherence questionnaires within the visit follow-up period, then the entire follow-up period would be defined as reporting 7/7ID. If participants reported <7/7ID any monthly adherence questionnaire within the follow-up period this would denote the follow-up period as reporting <7/7ID. Monthly and follow-up period adherence classifications are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Monthly and follow-up period PrEP adherence classifications.

| Monthly PrEP adherence | |

|---|---|

| Seven out of seven intended doses (7/7ID) | Less than seven out of seven intended doses (<7/7ID) |

| Participant reports missing 0 PrEP tablets in both 7 days before and 7 days after last CAI on monthly adherence form | Participant reports missing ≥1 PrEP tablet(s) in 7 days before and/or 7 days after last CAI on monthly adherence form |

| Follow-up period PrEP adherence | |

| Seven out of seven intended doses (7/7ID) within a follow-up period | Less than seven out of seven intended doses (<7/7ID) within a follow-up period |

| All monthly adherence forms within follow-up period between visits report taking seven out of seven intended doses in the 7 days before and 7 days after last CAI | ≥1 monthly adherence form(s) within follow-up period between visits reports less than seven out of seven intended doses in the 7 days before and/or 7 days after last CAI |

Statistical analysis

Comparative analyses using univariable logistic regression were performed to assess associations between the outcome and exposure of interest (<7/7ID within a follow-up period and chemsex reporting) and other covariates collected on baseline questionnaires at enrolment and visit questionnaires at each follow-up visit (demographics, lifestyle, sexual behaviour etc.). A forward stepwise approach was used for the multivariable model with chemsex, with variables entered where significant at p<0.1. Since participants could contribute to the analysis multiple times, robust variance was used for logistic regression analyses to account for clustering. Data were analysed using STATA 15.1.

Results

Our sample consisted of 1,479 visit questionnaires, 2,260 monthly adherence questionnaires and 388 baseline enrolment questionnaires derived from 388 participants, between 3rd December 2014 and 28th October 2016. The median number of follow-up visit questionnaires per participant over the study period was four (interquartile range [IQR]: 2–5), and the median number of adherence forms per participant was five (IQR: 3–7). The median number of adherence forms within a visit form period was 1 (IQR: 1–2).

Baseline characteristics

Descriptive analyses of participants from baseline questionnaires are detailed in Table 2 and were highly similar to baseline characteristics reported for the total PROUD study population (Dolling et al., 2016). Among the 388 participants within this study, median age was 36 years (IQR 30–43), 82% reported being of white ethnicity, and 60.6% were UK born. Almost all participants described their gender as male (99%; 384), and their sexuality as gay/homosexual (95.1%; 369). Among the participants, 43.3% reported currently being in a relationship, 63.4% reported completing a university degree or higher, and 73.2% were in full-time employment.

Table 2.

Participant sample characteristics at baseline from linked enrolment questionnaires (N = 388 participants).

| Demographics | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 384 | (99) |

| Transgender | 0 | (0) |

| Sexuality | ||

| Gay/homosexual | 369 | (95.1) |

| Straight/bisexual/other | 15 | (3.9) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 318 | (82) |

| Black | 13 | (3.4) |

| Asian | 18 | (4.6) |

| Other | 36 | (9.3) |

| Born in the UK | ||

| No | 151 | (38.9) |

| Yes | 235 | (60.6) |

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–25 | 40 | (10.3) |

| 26–35 | 145 | (37.4) |

| 36–45 | 119 | (30.7) |

| >45 | 84 | (21.7) |

| Maximum education level | ||

| University degree or higher | 246 | (63.4) |

| A levels / equivalent | 61 | (15.7) |

| GCSEs / equivalent | 38 | (9.8) |

| Vocational training/other qualifications | 23 | (5.9) |

| Still in full-time education | 10 | (2.6) |

| Finished education with no qualifications | 9 | (2.3) |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed/self-employed full-time | 284 | (73.2) |

| Employed/self-employed part-time | 38 | (9.8) |

| Unemployed | 24 | (6.2) |

| Student | 16 | (4.1) |

| Retired | 16 | (4.1) |

| Other | 7 | (1.8) |

| Relationship status | ||

| In relationship, living with partner | 113 | (29.1) |

| In relationship, not living with partner | 55 | (14.2) |

| Not currently in an ongoing relationship | 218 | (56.2) |

| Lifestyle | ||

| Recreational drug use in past 3 months | ||

| No | 92 | (23.7) |

| Yes | 286 | (73.7) |

| Alcohol drinking frequency | ||

| Never/Once | 40 | (10.3) |

| 2 or 3 times a month | 80 | (20.6) |

| Once or twice a week | 128 | (33) |

| 3 or 4 times a week | 75 | (19.3) |

| Nearly every day/Daily | 53 | (13.7) |

| Units of alcohol drank on a typical drinking day | ||

| 0–4 | 163 | (42) |

| 5–9 | 117 | (30.2) |

| 10+ | 60 | (15.5) |

| Perception of adherence ability throughout the trial | ||

| Find easy to remember to take drug daily | 250 | (64.4) |

| Might forget to take doses, will find daily dosing difficult | 122 | (31.4) |

Number of baseline enrolment questionnaires with missing data for gender (4); sexuality (4); ethnicity (3); born in the UK (2); education (1) employment (3) relationship status (2); recreational drug use (5); alcohol drinking frequency (12) alcohol units (48) perception of adherence (16)

Almost three quarters of participants (73.7%; 286) reported having used any recreational drugs in the three months prior to enrolment. Four in ten participants (43%; 167) reporting using one or more of the three chemsex-associated drugs, with a smaller proportion (12.9%; 50) reporting having used all three chemsex-associated drugs. 13.7% reporting drinking alcohol daily or nearly every day.

Participant prep adherence and chemsex reporting during follow-up

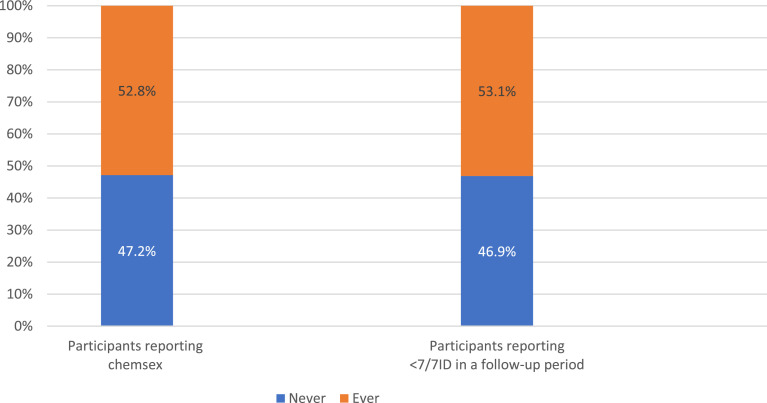

Nearly a quarter (23.3%; 527/2,260) of all adherence forms within our sample reported <7/7ID, with the majority (72.9%, 384/527) of these only reporting missing less than three intended doses in the week before and after last CAI. Chemsex and PrEP adherence reporting by participants at any time during their study period are described in Fig. 1. Just over half (52.8%, 205) of the participants ever reported engaging in chemsex on a follow-up visit questionnaire and just over half (53.1%, 206) ever had a follow-up period reporting <7/7ID. Most participants (85.8%, 333) had one or more follow-up period reporting 7/7ID.

Fig. 1.

Participant follow-up period PrEP adherence and chemsex reporting throughout trial follow-up (N = 388).

Follow-up period characteristics

Descriptive clinical, lifestyle and sexual behaviour characteristics from the 1,479 visit questionnaires are described in Table 3. Chemsex was reported on 38.5% visit questionnaires, 47.1% visit questionnaires reported group sex, 24% reported using sex toys and 13.9% reported fisting, since last visit. The median number of CAI partners in the 30 days prior to visit was 3 (IQR: 1–7). Only 8.8% of visit questionnaires reported an episode of injecting drug use and 20.1% reported powder cocaine use.

Table 3.

Visit questionnaire sample characteristics (N = 1479 visit questionnaires).

| Clinical | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Illness preventing daily activities since last follow-up visit | ||

| No | 1359 | (91.9) |

| Yes | 120 | (8.1) |

| Side effects to Truvada in last 30 days | ||

| No | 1433 | (96.9) |

| Yes | 38 | (2.6) |

| Lifestyle | ||

| Injected drugs since last follow-up visit | ||

| No | 1348 | (91.1) |

| Yes | 130 | (8.8) |

| Snorted cocaine since last follow-up visit | ||

| No | 1182 | (79.9) |

| Yes | 297 | (20.1) |

| Sexual behaviour | ||

| Number of condomless anal sex partners since last follow-up visit | ||

| 0 | 77 | (5.2) |

| 1 | 362 | (24.5) |

| 2–5 | 606 | (41) |

| >6 | 433 | (29.3) |

| Engaged in chemsex since last follow-up visit | ||

| No | 909 | (61.5) |

| Yes | 570 | (38.5) |

| Engaged in group sex since last follow-up visit | ||

| No | 783 | (52.9) |

| Yes | 696 | (47.1) |

| Used sex toys since last follow-up visit | ||

| No | 1124 | (76) |

| Yes | 355 | (24) |

| Engaged in fisting since last follow-up visit | ||

| No | 1273 | (86.1) |

| Yes | 205 | (13.9) |

| Follow-up period prep adherence | ||

| <7/7ID reported within last 90-day period | ||

| No | 1037 | (70.1) |

| Yes | 442 | (29.9) |

Number of follow-up visit questionnaires with missing data for side effects (8); injected drugs(1); number of condomless anal sex partners (1); fisting (1)

Factors associated with reporting less than 7 of 7 intended doses (≤7/7ID) within a follow-up period (Table 4)

Table 4.

Factors associated with reporting less than 7 of 7 intended doses (<7/7ID) in a follow-up period, from univariable and multivariable logistic regressions (N = 1479 follow-up visit questionnaires, N = 388 participants)a.

| Reporting <7/7ID in a follow-up period |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable |

Multivariable |

|||||||

| Totalc | nd | (%)e | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P | ||

| Baseline enrolment questionnaire variables - DEMOGRAPHICS | ||||||||

| Gender | Male | 1465 | 442 | (30.17%) | ||||

| Transgender | - | (0.00%) | ||||||

| Sexuality | Gay/homosexual | 1397 | 416 | (29.78%) | 1 | 0.851 | ||

| Straight/Bisexual/Other | 66 | 21 | (31.82%) | 1.10 (0.41–2.99) | ||||

| Ethnicity | White | 1196 | 336 | (28.09%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Black | 51 | 22 | (43.14%) | 1.94 (0.78 –4.80) | 0.151 | 1.78 (0.71 – 4.49) | 0.222 | |

| Asian | 69 | 30 | (43.48%) | 1.97 (0.84 –4.63) | 0.120 | 3.12 (1.20 – 8.21) | 0.020b | |

| Other | 151 | 50 | (33.11%) | 1.27 (0.76 –2.12) | 0.368 | 1.13 (0.64 – 1.97) | 0.678 | |

| Born in the UK | No | 569 | 171 | (30.05%) | 1 | 0.977 | ||

| Yes | 905 | 271 | (29.94%) | 0.99 (0.70 –1.42) | ||||

| Age (years)f | 18–25 | 148 | 62 | (41.89%) | 2.73 (1.48–5.04) | 0.001b | ||

| 26–35 | 532 | 181 | (34.02%) | 1.95 (1.21 –3.16) | 0.006b | |||

| 36–45 | 435 | 123 | (28.28%) | 1.49 (0.90 –2,47) | 0.118 | |||

| >45 | 364 | 76 | (20.88%) | 1 | ||||

| Maximum education levelf | University degree or higher | 965 | 282 | (29.22%) | 1 | |||

| A levels / equivalent | 201 | 65 | (32.34%) | 1.16 (0.70 –1.91) | 0.565 | |||

| GCSEs / equivalent | 149 | 36 | (24.16%) | 0.77 (0.40–1.49) | 0.441 | |||

| Vocational training/other qualifications | 92 | 32 | (34.78%) | 1.29 (0.67–2.49) | 0.444 | |||

| Still in full-time education | 39 | 20 | (51.28%) | 2.55 (1.05–6.21) | 0.039b | |||

| Finished education with no qualifications | 29 | 7 | (24.14%) | 0.77 (0.24–2.44) | 0.658 | |||

| Employment status | Employed/self-employed full time | 1050 | 298 | (28.38%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Employed/self-employed part time | 134 | 46 | (34.33%) | 1.32 (0.77–2.27) | 0.318 | 1.48 (0.81–2.70) | 0.203 | |

| Student | 107 | 43 | (40.19%) | 1.70 (0.88 –3.29) | 0.118 | 1.57 (0.75 –3.30) | 0.233 | |

| Unemployed | 77 | 30 | (38.96%) | 1.61 (0.72–3.62) | 0.248 | 2.31 (1.06–5.04) | 0.036b | |

| Retired | 70 | 15 | (21.43%) | 0.69 (0.24–1.99) | 0.491 | 0.53 (0.12 –2.35) | 0.403 | |

| Other | 30 | 10 | (33.33%) | 1.26 (0.45–3.50) | 0.655 | 0.53 (0.23–1.22) | 0.138 | |

| Relationship status | In relationship, living with partner | 429 | 110 | (25.64%) | 1 | |||

| In relationship, not living with partner | 192 | 55 | (28.65%) | 1.16 (0.64 –2.13) | 0.621 | |||

| Not currently in an ongoing relationship | 851 | 277 | (32.55%) | 1.40 (0.92–2.12) | 0.114 | |||

| Baseline enrolment questionnaire variables - Lifestyle | ||||||||

| Recreational drug use in past 3 months | No | 371 | 114 | (30.73%) | 1 | 0.718 | ||

| Yes | 1071 | 312 | (29.13%) | 0.93 (0.61–1.40) | ||||

| Alcohol drinking frequency | Never/Once | 169 | 46 | (27.22%) | ||||

| 2 or 3 times a month | 312 | 103 | (33.01%) | 1.32 (0.68 –2.55) | 0.412 | |||

| Once or twice a week | 483 | 133 | (27.54%) | 1.02 (0.53 –1.95) | 0.962 | |||

| 3 or 4 times a week | 286 | 96 | (33.57%) | 1.35 (0.67 –2.71) | 0.396 | |||

| Nearly every day/Daily | 190 | 48 | (25.26%) | 0.90 (0.43 –1.90) | 0.790 | |||

| Units of alcohol drank on a typical drinking day | 0–4 | 642 | 202 | (31.46%) | 1 | |||

| 5–9 | 442 | 129 | (29.19%) | 0.90 (0.60 –1.34) | 0.597 | |||

| ≥10 | 212 | 58 | (27.36%) | 0.82 (0.50–1.34) | 0.431 | |||

| Perception of adherence ability throughout the trial | Will find easy to remember to take drug daily | 966 | 249 | (25.78%) | 1 | 0.002b | 1 | 0.001b |

| Might forget to take doses/ will find daily dosing difficult | 462 | 175 | (37.88%) | 1.76 (1.23–2.51) | 1.88 (1.28 –2.75) | |||

| Follow-up questionnaire variables - Clinical | ||||||||

| Illness preventing daily activities since last visit | No | 1359 | 398 | (29.29%) | 1 | 0.116 | ||

| Yes | 120 | 44 | (36.67%) | 1.40 (0.92 –2.12) | ||||

| Side effects to Truvada in last 30 days | No | 1433 | 426 | (29.73%) | 1 | 0.599 | ||

| Yes | 38 | 10 | (26.32%) | 0.84 (0.45 –1.59) | ||||

| Follow-up questionnaire variables - Lifestyle | ||||||||

| Injected drugs since last visit | No | 1348 | 399 | (29.60%) | 1 | 0.684 | ||

| Yes | 130 | 42 | (32.31%) | 1.14 (0.62 –2.09) | ||||

| Snorted cocaine since last visit | No | 1182 | 343 | (29.02%) | 1 | 0.25 | ||

| Yes | 297 | 99 | (33.33%) | 1.22 (0.87–1.72) | ||||

| Follow-up questionnaire variables – Sexual behaviour | ||||||||

| Number of condomless anal sex partners since last visit | 0 | 77 | 20 | (25.97%) | 1 | |||

| 1 | 362 | 116 | (32.04%) | 1.34 (0.74 –2.43) | 0.327 | |||

| 2–5 | 606 | 176 | (29.04%) | 1.17 (0.64–2.14) | 0.619 | |||

| ≥6 | 433 | 130 | (30.02%) | 1.22 (0.64 –2.32) | 0.539 | |||

| Chemsex engagement since last visit | No | 909 | 253 | (27.83%) | 1 | 0.137 | 1 | 0.168 |

| Yes | 570 | 189 | (33.16%) | 1.29 (0.92–1.79) | 1.29 (0.90 –1.87) | |||

| Group sex since last visit | No | 783 | 249 | (31.80%) | 1 | 0.194 | ||

| Yes | 696 | 193 | (27.73%) | 0.82 (0.61–1.10) | ||||

| Used sex toys since last visit | No | 1124 | 334 | (29.72%) | 1 | 0.843 | ||

| Yes | 355 | 108 | (30.42%) | 1.03 (0.74–1.44) | ||||

| Fisting since last visit | No | 1273 | 386 | (30.32%) | 1 | 0.434 | ||

| Yes | 205 | 55 | (26.83%) | 0.84 (0.55–1.29) | ||||

Missing data from enrolment and visit questionnaires not included in logistic regression analyses.

Association considered significant (P<0.05).

total number of follow-up visit questionnaires reporting row variable.

total number of follow-up visit questionnaires reporting row variable and <7/7ID within linked 90-day follow-up period.

Row percentages based on non-missing data.

Not included retained in final multivariable logistic regression analyses as p-value >0.1 in multivariable model.

The univariable analyses demonstrated no statistically significant (p<0.05) association between chemsex engagement reported on follow-up visit questionnaires and reporting <7/7ID within linked follow-up periods (OR=1.29 [95% CI: 0.92–1.79], p = 0.137). Just over a third (33.2%) of follow-up periods linked to a visit questionnaire reporting chemsex since last visit reported <7/7ID and 27.8% follow-up periods linked to visit questionnaires not reporting chemsex reported <7/7ID.

Ethnicity, employment status and participants’ baseline perception of their adherence ability were entered into the multivariable model assessing chemsex and reporting <7/7ID within a follow-up period, as these were significant at p< 0.1 during the selection process. The association between chemsex and reporting <7/7ID remained statistically non-significant at p<0.05 (aOR=1.29 [95% CI: 0.90–1.87], p = 0.168). Within the multivariable analyses, visit questionnaires from participants perceiving at baseline they may encounter adherence difficulties were significantly associated with reporting <7/7ID at p<0.05 (aOR=1.88 [95% CI: 1.28–2.75], p = 0.001), as was reporting unemployment (aOR=2.31 [95% CI: 1.06–5.04], p = 0.036) and Asian ethnicity (aOR=3.12 [95% CI: 1.20–8.21], p = 0.020).

Although in the univariable analyses, visit questionnaires from participants in full-time education and aged 18–35 at baseline were significantly associated with reporting <7/7ID within a follow-up period, these variables were not retained in the final multivariable model as they were no longer significant at p<0.1.

Discussion

This analysis has shown no statistically significant association between reporting less than seven out of seven intended PrEP doses (<7/7ID) and reporting chemsex event periods among GBM. Although the direction of association is similar to that observed in the meta-analysis by Perera et al. (2017) between chemsex and ART non-adherence, their work focussed on reported use of drugs associated with chemsex only (i.e. not chemsex behaviour) and was assessed at the individual level. Our study assessed event-level data and measured specific reporting of chemsex behaviour by PROUD participants. Although ART and PrEP are both regular HIV-related medications used by GBM, they are taken for different purposes, the former to treat existing HIV infection, and the latter to prevent HIV acquisition. Therefore, motivations to adhere optimally will likely vary.

There is a growing amount of evidence suggesting that not all chemsex episodes or behaviours are inherently harmful, and that many GBM can successfully integrate sexualised drug use into their lives, whilst still being in control of their actions (Bourne, Reid, Hickson, Rueda & Weatherburn, 2014). Some sources report chemsex users as having relatively controlled drug use and maintaining safe sex strategies whilst under the influence of chemsex drugs (Graf, Dichtl, Deimel, Sander & Stover, 2018), or completely compartmentalising chemsex from the rest of their lives (Ahmed et al., 2016), suggesting that daily PrEP adherence around chemsex events can be achievable. A follow-up study of the TAPIR PrEP trial also found “less problematic” substance use to be a significant predictor of adequate adherence (Hoenigl, Hassan et al., 2019) and a recent study among Australian GBM has reported increased concurrent use of methamphetamines, Viagra and TruvadaⓇ-PrEP, demonstrating how PrEP can be added alongside chemsex drug use to mitigate against HIV risk (Hammoud et al., 2018).

It is also possible that GBM engaging in chemsex use tailored PrEP adherence strategies around periods of chemsex to ensure doses are not missed. Adapted PrEP adherence strategies documented among GBM engaging in sexualised drug use include habitually taking PrEP tablets at the start of the day and taking with other medications or when preparing for sex (Closson, Mitty, Malone, Mayer & Mimiaga, 2018). A study among thirty American GBM using PrEP and reporting illicit drug use found that although all individuals found that methamphetamine use negatively impacted PrEP adherence ability, many used innovative ways of remembering daily doses; 60% reported using reminder devices or memory techniques and 6.7% reported borrowing from peers and partners (Storholm et al., 2017).

Significantly higher odds of reporting <7/7ID within a follow-up period were observed from participants reporting at baseline that they may forget PrEP doses, compared to those perceiving they would find daily dosing easy. If PrEP becomes routinely available in England, it would be beneficial for clinicians to ascertain patients’ perception of their ability to adhere to PrEP during initial consultations, and provide adherence support where this is required. Compared to those of white ethnicity and those in full-time employment, follow-up periods from individuals of Asian ethnicity and those unemployed at baseline, also had significantly higher odds of reporting <7/7ID respectively, highlighting additional population groups that may benefit from adherence monitoring and support.

Strengths and limitations

This study benefitted from PROUD's large sample size and extensive collection of demographic, sexual behaviour and lifestyle data, allowing us to examine and adjust for multiple potential correlates and confounders for PrEP adherence. Our baseline data was also highly representative of the entire PROUD study population (Dolling et al., 2016), indicating that questionnaire exclusion criteria did not skew sample characteristics. As PROUD was delivered through thirteen sexual health clinics in six major English cities, this allows the results to be generalizable to urban populations of GBM at risk of HIV in England. These results may not, however, be generalizable to “low-risk” and non-urban GBM.

A major strength for this study was being able to use data that explicitly asked participants whether they engaged in chemsex using a specific chemsex definition, instead of using chemsex drug use as a proxy for the chemsex behaviour. Of the of 415 PROUD participants who completed acceptability questionnaires on the PROUD study design, 88% also reported feeling they could disclose sexual activity honestly, strengthening the validity of our exposure measurement (Gafos, Brodnicki, et al., 2017; . The longitudinal nature of PROUD meant multiple adherence data could be linked to multiple reported chemsex episodes over the study period; this would not have been possible if the analyses had been performed per participant, using an overall adherence measure for total individual follow-up time, and categorizing participants as chemsex and non-chemsex users. As both adherence and sexual behaviour may not be consistent for a participant throughout their trial follow-up, this was important to investigate, as much of the chemsex literature lacks event-level data (Edmundson et al., 2018). Visit questionnaires only asked participants one question about whether they engaged in chemsex, defined as using crystal methamphetamine, GHB/GBL or mephedrone immediately prior to, or during, sex. As the questionnaires did not ask participants to specify which of these three chemsex drugs were used, we were unable to assess associations between adherence and specific chemsex drug combinations.

Although some trials have observed self-reporting to provoke overestimations of adherence, it has also been demonstrated to be as accurate as refill and biological PrEP adherence measures in other trials (Amico et al., 2016; Lal et al., 2017; Montgomery et al., 2016; Vaccher et al., 2018) and self-reporting would have reduced social desirability bias compared to interviewing. Measuring adherence through missed doses before and after last condomless sex also meant adherence estimates were captured around critical risk periods for PrEP to be needed, however chemsex engagement itself could affect social desirability and recall bias when self-reporting adherence and recalling adherence, respectively.

An important drawback of this study is that reported chemsex events cannot be linked to the exact timeframe within the follow-up period where participants recorded missed pills. Further work is needed which asks GBM about PrEP adherence specifically during chemsex events. Our adherence classifications in Table 1 also meant that any single monthly adherence questionnaires reporting <7/7ID would denote an entire follow-up period as reporting <7/7ID. This would, however, most likely overestimate any negative impact of chemsex on adherence, which is contradictory to our findings. During data collection, we found that the majority of follow-up periods only had one linked monthly adherence questionnaire. As follow-up visits were supposed to be quarterly, this could mean there were months within a follow-up period where PrEP adherence was not captured on an adherence form. We are also aware that although follow-up visits were meant to be quarterly, in practise they did not always occur every 90 days, which was our cut-off for linking prior adherence forms to a follow-up visit date. Participants returning for follow-up visits were also almost exclusively doing so to obtain PrEP, hence participants who were adhering well to their PrEP may have been more likely to attend and contribute to our substudy cohort, potentially leading to an underestimation of any associations with reporting <7/7ID.

Our adherence measure may seem stringent due to evidence that taking PrEP ≥4/7 days a week is sufficient protection against HIV acquisition during anal sex (Anderson et al., 2012; (Grant et al., 2014)). The same analysis was repeated with missing ≥4/7 days of intended PrEP doses around last CAI as the adherence outcome measure, and no significant association with chemsex was found, however the sample size was too small to provide robust estimates due to the low proportion of follow-up periods (95/1479) that qualified for inclusion.

Chemsex reporting was clinician-completed at follow-up visits, meaning chemsex may have been underreported due to social desirability or acquiescence bias. Participants were asked about their last CAI in the 30 days prior in order to maximise recall for the adherence data, but participants were asked about chemsex activity since last follow-up visit (approx. quarterly), potentially introducing recall bias. Some participants reported difficulty in remembering sexual activity during recall periods, and finding questionnaires laborious and the monthly adherence questionnaires specifically hard to remember to complete (Gafos, Brodnicki, et al., 2017; Nonetheless, 82% of participants completing acceptability questionnaires reported not minding completing the monthly adherence forms (Gafos, Brodnicki, et al., 2017;

As PROUD participants had regular contact with clinics and frequent questionnaires reviewing adherence, the Hawthorne effect (Wickstrom & Bendix, 2000) could have influenced the optimal adherence profiles observed, through modified behaviour provoking improved adherence, and not reflecting true adherence whilst not under observation. Further insight into how chemsex users adhere to PrEP outside a trial setting is needed. As this substudy only measured the implementation component of adherence, it would be beneficial to measure initiation and persistence of PrEP adherence in the context of chemsex, as these adherence components are important in terms of risk of HIV acquisition Gafos, White, et al., 2017; Vrijens et al., 2012). As participants were not paying for their PrEP, their adherence may also change if there is an individual financial cost.

Conclusion

These analyses suggest that chemsex is not a barrier to optimal PrEP adherence among the PROUD study cohort, and that PrEP remains a feasible and effective prevention tool among GBM in England engaging in a sexual behaviour that is associated with HIV risk. These data strengthen evidence of PrEP's effectiveness as a key combination prevention method in the UK's progress towards ending the HIV epidemic. Whilst regular monitoring is recommended to help chemsex users manage their risk of chemsex associated harms, including HIV acquisition, it would be pertinent for clinicians to risk assess ethnic minority and unemployed individuals, or those with perceived adherence difficulties during initial PrEP prescribing, to ascertain if adherence support is needed.

Funding

The PROUD trial was supported by ad hoc funding from the Medical Research Council (MRC) Clinical Trials Unit at University College London and an innovations grant from Public Health England, and most clinics received support through the UK NIHR Clinical Research Network. Gilead Sciences provided Truvada, distributed drug to clinics, and awarded a grant for the additional diagnostic tests including drug concentrations in plasma. EW, DTD and SMc were supported by the UK Medical Research Council (MC_UU_12,023/23) during preparation of and outside the submitted work.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The PROUD study provided drug free of charge by Gilead Sciences plc. which also distributed it to participating clinics and provided funds for additional diagnostic tests for HCV and drug levels.

SMc reports grants from the European Union H2020 scheme, EDCTP 2, the National Institute of Health Research, and Gilead Sciences; other support from Gilead Sciences, and the Population Council Microbicide Advisory Board; and is Chair of the Project Advisory Committee for USAID grant awarded to CONRAD to develop tenofovir-based products for use by women (non-financial).

EW university fees and stipend funded by Gilead Science plc.

The remaining authors have no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the PROUD trial participants and trial and clinic staff.

A full list of contributors to the PROUD study are in Appendix A.

Data Sharing

The PROUD data is held at MRC CTU at UCL, which encourages optimal use of data by employing a controlled access approach to data sharing, incorporating a transparent and robust system to review requests and provide secure data access consistent with the relevant ethics committee approvals. All requests for data are considered and can be initiated by contacting proud.mrcctu@ucl.ac.uk.

The basis for this project originated from a MSc research project undertaken by COH at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), and ethical approval for this MSc project was granted by LSHTM. Data was accessed from University College London (UCL) and the Medical Research Council (MRC) Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) through a clinical data disclosure agreement and PROUD sub-study proposal agreement.

Contributor Information

Charlotte O'Halloran, Email: charlotte.ohalloran@phe.gov.uk.

Brian Rice, Email: Brian.Rice@lshtm.ac.uk.

Ellen White, Email: ellen.white@ucl.ac.uk.

Monica Desai, Email: Monica.Desai@nice.org.uk.

David T Dunn, Email: d.dunn@ucl.ac.uk.

Sheena McCormack, Email: s.mccormack@ucl.ac.uk.

Ann K. Sullivan, Email: Ann.Sullivan@Chelwest.nhs.uk.

David White, Email: david.white2@uhb.nhs.uk.

Alan McOwan, Email: Alan.McOwan@chelwest.nhs.uk.

Mitzy Gafos, Email: Mitzy.Gafos@lshtm.ac.uk.

Appendix A

STUDY CONTRIBUTORS

PROUD clinic and research teams

Birmingham Heartlands Hospital: Sian Gately, Gerry Gilleran, Jill Lyons, Chris McCormack, Katy Moore, Cathy Stretton, Stephen Taylor, David White

Brighton and Sussex University Hospital: Alex Acheampong, Michael Bramley, Amanda Clarke, Martin Fisher, Wendy Hadley, Kerry Hobbs, Sarah Kirk, Nicky Perry, Celia Richardson, Mark Roche, Emma Simpkin, Simon Shaw, Elisa Souto, Julia Williams, Elaney Youssef

Chelsea and Westminster Hospital: Simone Antonucci, Tristan Barber, Serge Fedele, Chris Higgs, Kathryn McCormick, Sheena McCormack, Alan McOwan, Alexandra Meijer, Sam Pepper, Jane Rowlands, Gurmit Singh, Sonali Sonecha, Ann Sullivan, Lervina Thomas

Gilead Sciences: Andrew Cheng, Rich Clarke, Bill Guyer, Howard Jaffe, Hans Reiser, Jim Rooney,

Homerton University Hospital: Frederick Attakora, Richard Castles, Rebecca Clark, Anke De-Masi, Veronica Espa, SifisoMguni, Iain Reeves

King's College Hospital: Hannah Alexander, Jake Bayley, Michael Brady, Shema Doshi, Susanna Gilmour-White, Larissa Mulka, James Stephenson

Manchester Royal Infirmary: Brynn Chappell, Carolyn Davies, Dornubari Lebari, Matthew Phillips, Gabriel Schembri, Lisa Southon, Sarah Thorpe, Anna Vas, Chris Ward, Stephanie Yau

Mortimer Market Centre: Alejandro Arenas-Pinto, Asma Ashraf, Richard Gilson, Lewis Haddow, Ana Milinkovic, June Minton, Dianne Morris, Clare Oakland, Pierre Pellegrino, Sarah Pett, Carmel Young

MRC CTU at UCL: Sarah Banbury, Elizabeth Brodnicki, Christina Chung, Yolanda Collaco Moraes, David Dolling, David Dunn, Keith Fairbrother, Mitzy Gafos, Fleur Hudson, Sajad Khan, Shabana Khan, Sheena McCormack, Brendan Mauger, Mary Rauchenberger, Annabelle South, Yinka Sowunmi, Susan Spencer, Ellen White, Gemma Wood

Public Health England: Lucy Boxall, Monica Desai, Sarika Desai, Noel Gill, Kate Hyland, Anthony Nardone, Parnam Seyan

Sheffield Teaching Hospital: Anthony Bains, Gill Bell, Christine Bowman, Terry Cox, Matt Harrison, Charlie Hughes, Hannah Loftus, Naomi Sutton, Debbie Talbot, Vince Tucker

Social Science Team: Gill Bell, Mitzy Gafos, Rob Horne (Lead), Will Nutland, Caroline Rae, Michael Rayment, Sonali Wayal

Royal London Hospital: Vanessa Apea, Drew Clark, Paul Davis, James Hand, Claire Mayes, Margaret Portman, Liat Sarner, John Saunders, Angelina Twumasi, Wayne Smith, Salina Tsui, Avan Umaipalan, Ryan Whyte, Andy Williams

St Mary's Hospital: Wilbert Ayap, Adam Croucher, Olamide Dosekun, Kristin Kuldanek, Ken Legg, Nicola Mackie, Nadia Naous, Killian Quinn, Severine Rey, Judith Zhou

St Thomas's Hospital: Margaret-Anne Bevan, Julie Fox, Lisa Hurley, Helen Iveron, Isabelle Jendrulek, Tammy Murray, Alice Sharp, Chi Kai Tam, Al Teague, Juan Tiraboschi

York Teaching Hospital: Christine Brewer, Richard Evans, Jan Gravely, Charles Lacey, Fabiola Martin, Georgina Morris, Sarah Russell-Sharpe, John Wightman,

PROUD Governance (Independent members)

Trial Steering Committee: Michael Adler (Co-Chair), Gus Cairns (Co-Chair) Daniel Clutterbuck, Rob Cookson, Claire Foreman, Stephen Nicholson, Tariq Sadiq, Matthew Williams Independent Data Monitor: Jack Cuzick

Independent Data Monitoring Committee: Simon Collins, Fiona Lampe, Anton Pozniak (Chair)

Community Engagement Group: Yusef Azad (NAT), Gus Cairns (NAM), Rob Cookson (LGF), Tom Doyle (Mesmac), Justin Harbottle (THT), Matthew Hodson (GMFA), Cary James (THT), Roger Pebody (NAM), Marion Wadibia (NAZ

References

- Ahmed A.K., Weatherburn P., Reid D., Hickson F., Torres-Rueda S., Steinberg P. Social norms related to combining drugs and sex (``chemsex'') among gay men in south london. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2016;38:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amico K.R., Mehrotra M., Avelino-Silva V.I., McMahan V., Veloso V.G., Anderson P. Self-reported recent prep dosing and drug detection in an open label prep study. AIDS and Behavior. 2016;20(7):1535–1540. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1360-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P.L., Glidden D.V., Liu A., Buchbinder S., Lama J.R., Guanira J.V. Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4(151):151ra25. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeten J.M., Donnell D., Ndase P., Mugo N.R., Campbell J.D., Wangisi J. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for hiv prevention in heterosexual men and women. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(5):399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne A., Reid D., Hickson F., Rueda S., Weatherburn P. Sigma Research, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine; London: 2014. The chemsex study: Drug use in sexual settings among gay and bisexual men in lambeth, southwark and lewisham. [Google Scholar]

- Bourne A., Reid D., Hickson F., Torres-Rueda S., Weatherburn P. Illicit drug use in sexual settings (`chemsex') and HIV/STI transmission risk behaviour among gay men in south london: Findings from a qualitative study. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2015;91(8):564–568. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Closson E.F., Mitty J.A., Malone J., Mayer K.H., Mimiaga M.J. Exploring strategies for prep adherence and dosing preferences in the context of sexualized recreational drug use among MSM: A qualitative study. AIDS Care. 2018;30(2):191–198. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1360992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneli A.L., Deese J., Wang M., Taylor D., Ahmed K., Agot K. FEM-PrEP: Adherence patterns and factors associated with adherence to a daily oral study product for pre-exposure prophylaxis. The Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2014;66(3):324–331. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskalopoulou M., Rodger A., Phillips A.N., Sherr L., Speakman A., Collins S. Recreational drug use, polydrug use, and sexual behaviour in HIV-diagnosed men who have sex with men in the UK: Results from the cross-sectional astra study. The Lancet HIV. 2014;1(1):E22–E31. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(14)70001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskalopoulou M., Rodger A.J., Phillips A.N., Sherr L., Elford J., McDonnell J. Condomless sex in HIV-diagnosed men who have sex with men in the UK: Prevalence, correlates, and implications for hiv transmission. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2017;93(8):590–598. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2016-053029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai M., Field N., Grant R., McCormack S. State of the art review: Recent advances in prep for hiv. BMJ (Clinical Researched) 2017;359(j5011) doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolling D.I., Desai M., McOwan A., Gilson R., Clarke A., Fisher M. An analysis of baseline data from the proud study: An open-label randomised trial of pre-exposure prophylaxis. Trials. 2016;17:163. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1286-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmundson C., Heinsbroek E., Glass R., Hope V., Mohammed H., White M. Sexualised drug use in the united kingdom (UK): A review of the literature. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;55:131–148. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonner V.A., Dalglish S.L., Kennedy C.E., Baggaley R., O'Reilly K.R., Koechlin F.M. Effectiveness and safety of oral hiv preexposure prophylaxis for all populations. AIDS (London, England) 2016;30(12):1973–1983. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gafos M., Brodnicki E., Desai M., McCormack S., Nutland W., Wayal S. Acceptability of an open-label wait-listed trial design: Experiences from the proud prep study. PloS One. 2017;12(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gafos M., White E., White D., Clarke A., Apea V., Brodnicki E. Adherence intentions, long-term adherence and hiv acquisition among prep users in the proud open-label randomised control trial of prep in england. International AIDS conference; 23-26 July 2017; Paris, France; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn R.W., Byrne N., O'Dea S., Shanley A., Codd M., Keenan E. Chemsex, risk behaviours and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men in dublin, ireland. The International Journal of Drug Policy. 2018;52:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf N., Dichtl A., Deimel D., Sander D., Stover H. Chemsex among men who have sex with men in germany: Motives, consequences and the response of the support system. Sexual health. 2018;15(2):151–156. doi: 10.1071/SH17142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant R.M., Anderson P.L., McMahan V., Liu A., Amico K.R., Mehrotra M. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and hiv incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: A cohort study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2014;14(9):820–829. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70847-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C., Rendina H.J., John S.A., Parsons J.T. Determining the roles that club drugs, marijuana, and heavy drinking play in prep medication adherence among gay and bisexual men: Implications for treatment and research. AIDS and Behavior. 2018;23(5):1277–1286. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2309-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberer J.E., Baeten J.M., Campbell J., Wangisi J., Katabira E., Ronald A. Adherence to antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention: A substudy cohort within a clinical trial of serodiscordant couples in east africa. PLOS Medicine. 2013;10(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis P., Levy M., Moreira A., Ferrusi C. Crystal methamphetamine use and hiv transmission among gay and bisexual men. Current Addiction Reports. 2014;1(3):206–213. [Google Scholar]

- Hammoud M.A., Vaccher S., Jin F., Bourne A., Haire B., Maher L. The new mtv generation: Using methamphetamine, truvada, and viagra to enhance sex and stay safe. The International Journal of Drug Policy. 2018;55:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegazi A., Lee M.J., Whittaker W., Green S., Simms R., Cutts R. Chemsex and the city: Sexualised substance use in gay bisexual and other men who have sex with men attending sexual health clinics. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2017;28(4):362–366. doi: 10.1177/0956462416651229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoenigl M., Hassan A., Moore D.J., Anderson P.L., Corado K., Dube M.P. Predictors of long-term hiv pre-exposure prophylaxis adherence after study participation in men who have sex with men. The Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2019;81(2):166–174. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoenigl M., Morgan E., Franklin D., Anderson P.L., Pasipanodya E., Dawson M. Self-initiated continuation of and adherence to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) after prep demonstration project roll-off in men who have sex with men: Associations with risky decision making, impulsivity/disinhibition, and sensation seeking. The Journal of NeuroVirology. 2019;25(3):324–330. doi: 10.1007/s13365-018-0716-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Hou J., Song A., Liu X., Yang X., Xu J. Efficacy and safety of oral TDF-Based pre-exposure prophylaxis for men who have sex with men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2018;9:799. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon C., Wouters K., Platteau T., Buyze J., Florence E. Increases in condomless chemsex associated with hiv acquisition in msm but not heterosexuals attending a hiv testing center in antwerp, belgium. AIDS Research and Therapy. 2018;15(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s12981-018-0201-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal L., Audsley J., Murphy D.A., Fairley C.K., Stoove M., Roth N. Medication adherence, condom use and sexually transmitted infections in australian preexposure prophylaxis users. AIDS (London, England) 2017;31(12):1709–1714. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane A. Sex, drugs and self-control: Why chemsex is fast becoming a public health concern. The Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health care/Faculty of Family Planning & Reproductive Health Care, Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists. 2016;42(4):291–294. doi: 10.1136/jfprhc-2016-101576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrazzo J.M., Ramjee G., Richardson B.A., Gomez K., Mgodi N., Nair G. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for hiv infection among african women. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(6):509–518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell S., Shahmanesh M., Gafos M. Chemsex behaviours among men who have sex with men: A systematic review of the literature. The International Journal of Drug Policy. 2019;63:74–89. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack S., Dunn D.T., Desai M., Dolling D.I., Gafos M., Gilson R. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): Effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet (London, England) 2016;387(10013):53–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00056-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack, S., Fidler, S., Waters, L., Azad, Y., Barber, T., & Cairns, G. et al. (2016).BHIVA–BASHH position statement on prep in UK: Second update may 2016 UK: Bhiva;[Available from:https://www.bhiva.org/update-to-BHIVA-BASHH-position-statement-on-PrEP.aspx.

- Molina J.M., Capitant C., Spire B., Pialoux G., Cotte L., Charreau I. On-Demand preexposure prophylaxis in men at high risk for HIV-1 infection. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373(23):2237–2246. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery M.C., Oldenburg C.E., Nunn A.S., Mena L., Anderson P., Liegler T. Adherence to pre-exposure prophylaxis for hiv prevention in a clinical setting. PloS One. 2016;11(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash S D.S., Croxford S., Guerra L., Lowndes C., Connor N., Gill O.N. Public Health England; London: 2018. Progress towards ending the HIV epidemic in the united kingdom: 2018 report. [Google Scholar]

- NHS England. PrEP impact trial questions and answers england: Nhs england; (2017). [Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/spec-services/npc-crg/blood-and-infection-group-f/f03/prep-impact-trial-questions-and-answers/#has-the-trial-received-ethical-approval.

- Okwundu C.I., Uthman O.A., Okoromah C.A. Antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for preventing hiv in high-risk individuals. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;7 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007189.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottaway Z., Finnerty F., Buckingham T., Richardson D. Increasing rates of reported chemsex/sexualised recreational drug use in men who have sex with men attending for postexposure prophylaxis for sexual exposure. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2017;93(1):31. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2016-052877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakianathan M., Whittaker W., Lee M.J., Avery J., Green S., Nathan B. Chemsex and new hiv diagnosis in gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men attending sexual health clinics. HIV Medecine. 2018 doi: 10.1111/hiv.12629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera S., Bourne A., Thomas S. P198 Chemsex and antiretroviral therapy non-adherence in HIV-positive men who have sex with men: A systematic review. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2017;93(A81) [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England. Substance misuse services for men who have sex with men involved in chemsex [briefing note] (2015). Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/669676/Substance_misuse_services_for_men_who_have_sex_with_men_involved_in_chemsex.pdf.

- Ristuccia A., LoSchiavo C., Halkitis P.N., Kapadia F. Sexualised drug use among sexual minority young adults in the united states: The P18 cohort study. The International Journal of Drug Policy. 2018;55:207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux P., Fressard L., Suzan-Monti M., Chas J., Sagaon-Teyssier L., Capitant C. Is on-demand HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis a suitable tool for men who have sex with men who practice chemsex? results from a substudy of the anrs-ipergay trial. The Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2018;79(2):E69–e75. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewell J., Cambiano V., Miltz A., Speakman A., Lampe F.C., Phillips A. Changes in recreational drug use, drug use associated with chemsex, and HIV-related behaviours, among HIV-negative men who have sex with men in london and brighton, 2013-2016. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2018;94(7):494–501. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2017-053439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinner C.D., Boesecke C., Zink A., Jessen H., Stellbrink H.J., Rockstroh J.K. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): A review of current knowledge of oral systemic hiv prep in humans. Infection. 2016;44(2):151–158. doi: 10.1007/s15010-015-0850-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storholm E.D., Volk J.E., Marcus J.L., Silverberg M.J., Satre D.D. Risk perception, sexual behaviors, and prep adherence among substance-using men who have sex with men: A qualitative study. Prevention Science : the Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research. 2017;18(6):737–747. doi: 10.1007/s11121-017-0799-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart D. Sexualised drug use by MSM: Background, current status and response. HIV Nursing. 2013;13(1):6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Tomkins A., George R., Kliner M. Sexualised drug taking among men who have sex with men: A systematic review. Perspectives in Public Health. 2019;139(1):23–33. doi: 10.1177/1757913918778872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccher S.J., Marzinke M.A., Templeton D.J., Haire B.G., Ryder N., McNulty A. Predictors of daily adherence to hiv pre-exposure prophylaxis in gay/bisexual men in the prelude demonstration project. AIDS and Behavior. 2018;23(5):1287–1296. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2353-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Damme L., Corneli A., Ahmed K., Agot K., Lombaard J., Kapiga S. Preexposure prophylaxis for hiv infection among african women. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(5):411–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrijens B., De Geest S., Hughes D.A., Przemyslaw K., Demonceau J., Ruppar T. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2012;73(5):691–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White E., Dunn D.T., Desai M., Gafos M., Kirwan P., Sullivan A.K. Predictive factors for hiv infection among men who have sex with men and who are seeking prep: A secondary analysis of the proud trial. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2019;95(6):449–454. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2018-053808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickstrom G., Bendix T. The ``Hawthorne effect''–what did the original hawthorne studies actually show? Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 2000;26(4):363–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]