Abstract

Introduction

The optimal choice of first-line chemotherapy in urothelial carcinoma (UC) patients who relapse after receiving peri-operative cisplatin-based chemotherapy (PCBC) is unclear. We investigated outcomes with cisplatin re-challenge vs. a non-cisplatin regimen in patients with recurrent metastatic UC following PCBC in a multicenter retrospective study.

Methods

Individual patient-level data were collected for patients who received various first-line chemotherapies for advanced UC following previous PCBC. Cox proportional hazards models were used to investigate the prognostic ability of type of peri-operative and first-line chemotherapy to independently impact overall survival (OS) and progression-free (PFS) after accounting for known prognostic factors.

Results

Data were available for 145 patients (12 centers). The mean age was 62 years; ECOG-PS was >0 in 42.0% patients. Sixty-three-percent of patients received cisplatin-based first-line chemotherapy and the median time from prior chemotherapy (TFPC) was 6.2 months (range 1–154). Median OS was 22 months (95%CI:18–27) and median PFS was 6 months (95%CI:5–7). Better ECOG-PS and longer TFPC (>12 months vs ≤12 months; HR 0.32, 95%CI: 0.20–0.52, p<0.001) was prognostic for OS and PFS. Cisplatin-based chemotherapy was associated with poor OS (1.86 [95% CI: 1.13, 3.06], p=0.015), which appeared to be pronounced in those patients with TFPC ≤12 months, re-treatment with cisplatin in the first-line setting was associated with worse OS (HR=3.38, p<0.001).

Conclusions

This retrospective analysis suggests that in patients who had received prior PCBC for UC, re-challenging with cisplatin may confer poorer OS, especially in those who progressed in less than a year.

Keywords: cisplatin, first-line, peri-operative, urothelial carcinoma

Microabstract

To identify the optimal choice for first-line chemotherapy in advanced urothelial carcionoma (UC) we investigated outcomes with cisplatin vs. non-cisplatin regimens in patients with mtastastic UC following peri-operative cisplatin-based chemotherapy (PCBC) in a multicenter retrospective study. In patients who had received prior PCBC for UC, re-challenging with cisplatin conferred poorer overall survival, especially in those who progressed in less than one-year.

Introduction

Despite relatively high initial response rates to chemotherapy, durability of response is still suboptimal, and 5-year survival rates for patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma (UC) of the bladder is only 10–20% 1,2. In both the peri-operative and first-line metastatic setting, cisplatin combination chemotherapy (predominantly gemcitabine and cisplatin (GC); or methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin and cisplatin (MVAC)) is the standard of care 1–7. For those patients who progress after receiving peri-operative cisplatin-based chemotherapy, however, there is no consensus as to whether cisplatin re-challenge or the use of a different regimen is superior. Clinical trials which established MVAC and GC as standard of care for metastatic therapy 1–5 were conducted in populations for whom peri-operative chemotherapy was either not yet an option or did not allow prior systemic therapy 8. Yet contemporary trials evaluating these regimens in patients after PCBC are lacking. A key question therefore is: should advanced UC after PCBC be re-treated with cisplatin based chemotherapy or receive a different non-cisplatin or second-line regimen to improve efficacy.

To address this question we initiated a multicenter retrospective study to investigate differences in outcomes between patients with advanced UC who received cisplatin-based first-line chemotherapy versus those who did not receive cisplatin-based first-line chemotherapy, following previous peri-operative (neoadjuvant or adjuvant) cisplatin-based chemotherapy (PCBC). It was hypothesized that patients with a long TFPC would be reflective of platinum-sensitive disease, and these patients would have improved outcomes with cisplatin-based chemotherapy in the first-line setting. Conversely, the therapeutic index may be better when using a non-cisplatin regimen in those with a short TFPC following PCBC.

Patients and Methods

Patient population

Individual patient-level data were collected from 12 regional referral centres in North America and Europe for consecutive patients who received chemotherapy for advanced UC after previous peri-operative cisplatin-based therapy. Data included age, sex, baseline visceral metastasis (defined as one or more of bone, brain, liver, lung), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), time from prior peri-operative chemotherapy (TFPC), calculated creatinine clearance, hemoglobin (Hb), leukocyte count, and albumin. Peri-operative and first-line chemotherapy treatment information, such as number of cycles of chemotherapy, dose of cisplatin per cycle, setting of peri-operative chemotherapy (neoadjuvant or adjuvant), and first-line regimen were also collected, along with patient outcomes, specifically objective response-rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS), from first-line therapy. The study was conducted after approval from the ethics committee of the University of British Columbia (sponsor of the study) and of each participating Institutions.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient and treatment characteristics and outcomes. The study endpoints were PFS and OS. OS was the primary clinical endpoint of interest and defined as the time between the start of first-line therapy and death from any cause; time was censored at the date of last follow-up for patients remaining alive. PFS was the time between the start of first-line therapy and the date of disease progression or death without progression, whichever occurred first; time was censored at the date of last follow-up for patients alive without progression, both defined from the date of beginning first-line chemotherapy. TFPC was defined from the last date of peri-operative chemotherapy until the first date of first-line therapy. Predefined cut points of TFPC were selected a priori at ~0.5 years (26 weeks), ~1 year (52 weeks), ~1.5 years (78 weeks), and ~2 years (104 weeks) for analysis. Anemia was defined as Hb < the lower limit of normal recorded by the local laboratory. Leukocytosis was defined as a white blood cell count (WBC) > the upper limit of normal (ULN) based on the local laboratory. Albumin was evaluated on a continuous scale.

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate time to event outcomes. Univariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to investigate the prognostic ability of all factors and clinical trial status (i.e. whether therapy was on trial or not) on OS and PFS. The effect of treatment for metastatic disease (cisplatin-based chemotherapy versus non-cisplatin-based chemotherapy) and specific peri-operative chemotherapy (GC, MVAC or others) was investigated univariably, and in a multivariable model after adjusting for 4 known prognostic factors; ECOG-PS (≥1 versus 0), anemia, visceral metastases, and TFPC. Attempts to identify optimal cut points for TFPC were performed by examining martingale residuals, and evaluating results from multiple models based on TFPC as a log-transformed continuous covariable, and using the a priori defined cut points. All tests and confidence intervals (CIs) were 2-sided and statistical significance was defined at P = 0.05 level.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient and treatment characteristics are summarized in Table 1. One-hundred and forty-five patients treated from 1995–2014 (exception: 2007–2011 for UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center) were included from 12 institutions in North America and Europe. The median (range) age of patients was 63 (32–81) years at first-line, over three-quarters of patients were male, and 10.4% were ECOG PS 2 or 3. Most patients (n=90, 63.8%) received adjuvant chemotherapy. Eighty-one (57.5%) patients received GC peri-operative chemotherapy, 36 (25.5%) received MVAC, and 24 (17%) received another cisplatin-based regimen. These other cisplatin-based regimes consisted of 11 patients who received methotrexate, vinblastine, epirubicin, cisplatin, and 9 who received methotrexate, cisplatin and the remaining 4 patients received another cisplatin-based combination. Ninety-one (62.8%) were retreated with cisplatin-based first-line chemotherapy (cisplatin with etoposide, methotrexate, vinblastine, gemcitabine or doxorubicin) and 12 (8.3%) received first-line therapy as part of a clinical trial. Clinical trial therapies included AZD4877, OGX427, PZP, ramucirumab, sunitinib, vinflunine, vinblastine, nab-paclitaxel. The remaining 42 (28.9%) patients received non-cisplatin-based first-line therapy regimes including carboplatin with vinblastine, paclitaxel or gemcitabine, paclitaxel with gemcitabine or everolimus, ramucirumab with docetaxel docetaxel alone, paclitaxel alone. Median (IQR) TFPC was 7 (1 to 19) months. Since only 24 (17.0%) patients had TFPC > 2 years, the use of 2 years as a cut point was excluded from future analyses. After a median follow up of 10.8 (IQR: 5.5–18.9) months, 136 (94%) patients had confirmed disease progression, and 104 (71.7%) patients have died. One-year PFS and OS were 22.7% (95%CI: 16.1 to 29.9) and 73.8% (95%CI: 65.3 to 80.5), respectively.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Variable | Total Patients | Overall (n = 145) | Cisplatin (n = 91) | Other (n = 54) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institution | 145 | NS | |||

| AOU Frederico II + Napoli | 13 (9.0) | 13 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| BCCA | 21 (14.5) | 17 (18.9) | 4 (7.4) | ||

| CCI | 11 (7.6) | 10 (11.0) | 1 (1.9) | ||

| COH | 3 (2.1) | 3 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Dusseldorf | 5 (3.5) | 2 (2.2) | 3 (5.6) | ||

| AUO 20/99 (GemTax) | 35 (24.1) | 0 (0.0) | 35 (64.8) | ||

| INT | 44 (30.3) | 38 (41.8) | 6 (11.1) | ||

| Karmanos | 5 (3.5) | 1 (1.1) | 4 (7.4) | ||

| Liverpool | 1 (0.7) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| UAB | 4 (2.8) | 3 (3.3) | 1 (1.9) | ||

| Utah | 3 (2.1) | 3 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Male gender | 145 | 113 (77.9) | 71 (78.0) | 42 (77.8) | .97 |

| Perioperative chemotherapy | 141 | .063 | |||

| Neoadjuvant-based | 51 (36.2) | 38 (41.8) | 13 (26.0) | ||

| Adjuvant-based | 90 (63.8) | 53 (58.2) | 37 (74.0) | ||

| Perioperative chemotherapy type | 141 | <.001 | |||

| GC | 81 (57.5) | 60 (65.9) | 21 (42.0) | ||

| MVAC | 36 (25.5) | 30 (33.0) | 6 (12.0) | ||

| Other cisplatin-basedb | 24 (17.0) | 1 (1.1) | 23 (46.0) | ||

| Cycles (n) | 140 | <.001 | |||

| 1 | 20 (14.3) | 16 (17.8) | 4 (8.0) | ||

| 2 | 29 (20.7) | 27 (30.0) | 2 (4.0) | ||

| 3 | 36 (25.7) | 16 (17.8) | 20 (40.0) | ||

| 4 | 46 (32.9) | 23 (31.1) | 18 (36.0) | ||

| 5 | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.0) | ||

| 6 | 7 (5.0) | 3 (3.3) | 4 (8.0) | ||

| Metastatic recurrence site: visceral disease | 145 | 69 (47.6) | 44 (48.4) | 25 (46.3) | .81 |

| Time from PCBC to first-line (mo) | 141 | .003 | |||

| Median | 6.2 | 2.3 | 8.1 | ||

| IQR | 0.9–17.3 | 0.9–16.6 | 4.8–22.8 | ||

| TFPC | 141 | ||||

| >6 mo | 72 (51.1) | 40 (44.0) | 32 (64.0) | .023 | |

| >12 mo | 45 (31.9) | 27 (29.7) | 18 (36.0) | .44 | |

| >18 mo | 32 (22.7) | 18 (19.8) | 14 (28.0) | .26 | |

| >24 mo | 24 (17.0) | 13 (14.3) | 11 (22.0) | .24 | |

| Mean age at first-line therapy (year) | 141 | 61.6 ± 8.8 | 61.1 ± 8.2 | 62.6 ± 9.7 | .18 |

| Weight at first-line therapy (kg) | 94 | .46 | |||

| Median | 76.8 | 77.5 | 74.5 | ||

| Range | 49–140 | 50–140 | 49–123 | ||

| First-line chemotherapya | 145 | ||||

| Cisplatin, no clinical trial | 89 (66.9) | 89 (97.8) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Clinical trial | 12 (8.3) | 2 (2.2) | 10 (18.5) | ||

| Non-cisplatin, no clinical trial | 44 (33.1) | 0 (0.0) | 44 (81.5) | ||

| Frequency of first-line chemotherapy | .003 | ||||

| Every 2 wk | 140 | 19 (13.6) | 19 (20.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Every 3 wk | 116 (82.9) | 69 (75.8) | 47 (95.9) | ||

| Every 4 wk | 5 (3.6) | 3 (3.3) | 2 (4.1) | ||

| No. of first-line cycles | 137 | .64 | |||

| Median | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||

| Range | 1–17 | 1–8 | 1–17 | ||

| First-line therapy stopped by toxicity | 139 | 31 (22.3) | 21 (23.1) | 10 (20.8) | .76 |

| ECOG PS at first-line therapy | 135 | <.001 | |||

| 0 | 74 (54.8) | 60 (67.4) | 14 (30.4) | ||

| 1 | 47 (34.8) | 21 (23.6) | 26 (56.5) | ||

| 2 | 12 (8.9) | 6 (6.7) | 6 (13.0) | ||

| 3 | 2 (1.5) | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Creatinine clearance (mL/min) | 126 | .003 | |||

| <60 | 38 (30.2) | 17 (21.0) | 21 (46.7) | ||

| ≥60 | 88 (69.8) | 64 (79.0) | 24 (53.3) | ||

| Hemoglobin, normal range | 138 | 78 (56.5) | 45 (52.3) | 33 (63.5) | .20 |

| WBC count greater than ULN | 131 | 65 (49.6) | 29 (34.9) | 36 (75.0) | <.001 |

| Albumin | 63 | .64 | |||

| Median | 4 | 4 | 4.1 | ||

| Range | 2.2–5.12 | 2.2–5.1 | 3.3–4.5 | ||

| Best overall response to first-line therapy | 145 | .29c | |||

| CR | 18 (12.4) | 11 (12.1) | 7 (13.0) | ||

| PR | 47 (32.4) | 22 (24.2) | 8 (14.8) | ||

| SD | 30 (20.7) | 17 (18.7) | 20 (37.0) | ||

| PD | 37 (25.5) | 5 (5.5) | 8 (14.8) | ||

| NE | 13 (9.0) | 36 (39.6) | 11 (20.4) | ||

| PFS | 145 | .12 | |||

| Patients with progression | 136 (93.8) | 85 (93.4) | 51 (94.4) | ||

| Median PFSd (mo) | 5.5 (4.1–6.2) | 6.0 (5.5–7.4) | 3.5 (2.1–5.1) | ||

| 6-mo PFS (%) | 43.1 (34.8–51.1) | 49.4 (38.7–59.3) | 32.6 (20.5–45.2) | ||

| 12-mo PFS (%) | 22.7 (16.1–29.9) | 24.1 (15.8–33.5) | 20.4 (10.7–32.3) | ||

| 24-mo PFS (%) | 8.7 (4.6–14.3) | 9.5 (4.4–17.0) | 7.6 (2.3–17.5) | ||

| OS | 145 | .18 | |||

| Patients who died | 104 (71.7) | 58 (63.7) | 46 (85.2) | ||

| Median OSd (mo) | 19.8 (16.1–24.4) | 18.0 (13.8–21.4) | 23.7 (16.1–33.8) | ||

| 6-mo OS (%) | 89.2 (82.7–93.3) | 87.5 (78.5–92.9) | 92.2 (80.5–97.0) | ||

| 12-mo OS (%) | 73.8 (65.3–80.5) | 70.4 (59.0–79.1) | 83.8 (70.2–91.6) | ||

| 24-mo OS (%) | 41.5 (32.4–50.4) | 36.0 (24.6–47.6) | 49.7 (34.9–62.9) | ||

| 60-mo OS (%) | 17.1 (10.3–25.4) | 13.8 (5.5–25.6) | 20.9 (10.5–33.6) |

Data presented as n (%), mean ± standard deviation, or rate (95% CI), unless otherwise noted. Abbreviations: AOU Frederico II + Napoli = University of Naples; AUO = Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria; BCCA = British Columbia Cancer Agency; CCI = Cross Cancer Institute; CI = confidence interval; COH = City of Hope Cancer Center; CR = complete response; Dusseldorf = Heinrich Heine University; ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; GC = gemcitabine and cisplatin; MVAC = methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, cisplatin; INT = Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori; IQR = interquartile range; Karmanos = Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute; Liverpool = University of Liverpool; NE = not evaluable; OS = overall survival; PD = progressive disease; PFS = progression-free survival; PR = partial response; PS = performance status; SD = stable disease; TFPC = time from previous chemotherapy; UAB = UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center; ULN = upper limit of normal; Utah = Huntsman Cancer Institute; WBC = white blood cell.

First-line chemotherapy: cisplatin-based—cisplatin with etoposide, methotrexate, vinblastine, and gemcitabine or doxorubicin; clinical trial-based—, OGX427, PZP, ramucirumab, sunitinib, VFL ×2, vinblastine, vinflunine ×3, nab-paclitaxel; non—cisplatin-based—carboplatin with vinblastine, paclitaxel, or gemcitabine; paclitaxel with gemcitabine or everolimus; ramucirumab with docetaxel; docetaxel alone; paclitaxel alone.

Other cisplatin-based = methotrexate, vinblastine, epirubicin, cisplatin (n = 11), methotrexate, cisplatin (n = 9), various combinations (n = 4).

Response versus no response.

Data in parentheses are 95% CIs.

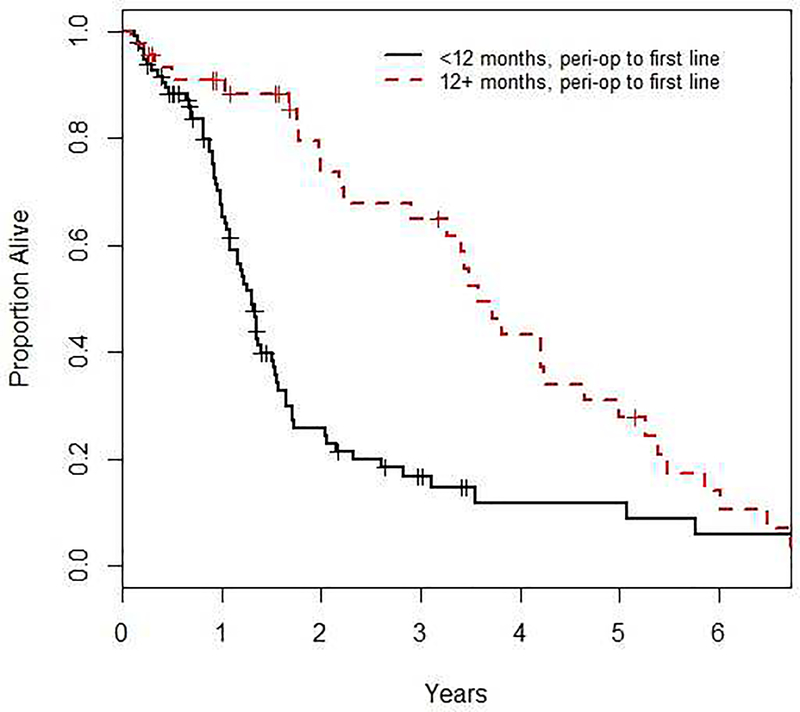

Association of variables with OS

The results of the univariate and multivariable Cox analyses on OS are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. In the univariate analysis, the type of peri-operative chemotherapy (GC: HR=1.54, 95% CI=0.95 to 2.49, MVAC: HR=0.81, 95% CI=0.41 to 1.61, overall p=0.046), TFPC (26-week cut point: HR=0.50, 95% CI=0.33 to 0.74, p<0.001; 12 months: HR=0.42, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.65, p<0.001; 20 months: HR=0.40, 95% CI=0.25 to 0.65, p<0.001; log-transformed: HR=0.85, 95% CI=0.76 to 0.95, p=0.005) and age at first-line therapy (HR=0.97, 95% CI=0.95 to 1.00, p=0.025) were all statistically significant. Figure 1 shows the OS for patients based on TFPC >52 versus ≤12 months.

Table 2.

Prognostic Factors for OS (Univariate)

| Factor | N | Hazards Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female vs Male | 145 | 0.78 (0.49, 1.27) | 0.32 |

| Peri-operative Chemo | Adjuvant vs Neoadjuvant | 141 | 0.80 (0.53, 1.21) | 0.29 |

| Peri-operative Chemo Type | GC | 141 | 1.54 (0.95, 2.49) | 0.046 |

| MVAC | 0.81 (0.41, 1.61) | |||

| Other Cisplatin-Based | Reference | |||

| Number of Cycles | Continuous | 140 | 0.90 (0.76, 1.07) | 0.23 |

| Site of Metastases | Visceral Disease vs No | 145 | 0.93 (0.63, 1.37) | 0.70 |

| Time Peri-op to first-line | Log-transformation |

141 | 0.85 (0.76, 0.95) |

0.005 |

| >6 vs ≤2 |

0.50 (0.33, 0.74) |

<0.001 |

||

| >12 vs ≤12 |

0.42 (0.27, 0.65) |

<0.001 |

||

| >18 vs ≤18 | 0.40 (0.25, 0.65) | <0.001 | ||

| Age at first-line | Continuous | 141 | 0.97 (0.95, 1.00) | 0.025 |

| Weight at first-line, kg | Continuous | 94 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.80 |

| ECOG Status at first-line | 1+ vs 0 | 135 | 1.34 (0.89, 2.01) | 0.16 |

| Creatinine Clearance | ≥60 ml/min vs <60 | 126 | 0.76 (0.50, 1.16) | 0.20 |

| Hemoglobin | In Normal Range vs No | 138 | 1.06 (0.71, 1.57) | 0.78 |

| WBC | >ULN vs No | 131 | 1.11 (0.75, 1.65) | 0.61 |

| Albumin | Continuous | 63 | 0.60 (0.36, 1.01) | 0.057 |

| First-line Chemotherapy | Cisplatin | 145 | 1.32 (0.88, 1.97) | 0.18 |

| First-line Chemotherapy | Clinical Trial | 145 | 1.35 (0.65, 2.79) | 0.42 |

| Frequency of first-line Chemotherapy | Ordinal | 140 | 0.91 (0.43, 1.91) | 0.80 |

| First-line Non-Cisplatin Patients* | ||||

| Time Peri-op to first-line | >12 vs ≤12 months | 50 | 0.39 (0.21, 0.75) | 0.004 |

| Time Peri-op to first-line | >18 vs ≤18 months | 50 | 0.40 (0.21, 0.78) | 0.007 |

| First-line Cisplatin Patients* | ||||

| Time Peri-op to first-line | >12 vs ≤12 months | 91 | 0.42 (0.23, 0.76) | 0.004 |

| Time Peri-op to first-line | >18 vs ≤18 months | 91 | 0.39 (0.19, 0.78) | 0.008 |

Interaction term between cisplatin status and time from peri-op to first-line therapy was not significant (12 months p=0.92 and 20 months p=0.89).

Table 3.

Prognostic Factors for OS (Multivariable)

| Factor | N | Hazards Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients†* | ||||

| ECOG Status at first-line | 1+ vs 0 | 128 | 2.24 (1.36, 3.69) | 0.002 |

| Site of Metastases | Visceral Disease vs No | 0.83 (0.55, 1.25) | 0.38 | |

| Hemoglobin | In Normal Range vs No | 0.77 (0.49, 1.21) | 0.26 | |

| Time Peri-op to first-line | >12 vs ≤12 months | 0.32 (0.20, 0.52) | <0.001 | |

| First-line Chemotherapy | Cisplatin | 1.86 (1.13, 3.06) | 0.015 | |

| TFPC ≤12 months | ||||

| ECOG Status at first-line | 1+ vs 0 | 85 | 4.50 (2.26, 8.97) | <0.001 |

| Site of Metastases | Visceral Disease vs No | 0.94 (0.57, 1.57) | 0.82 | |

| Hemoglobin | In Normal Range vs No | 0.91 (0.53, 1.54) | 0.71 | |

| First-line Chemotherapy | Cisplatin | 3.38 (1.66, 6.89) | <0.001 | |

| TFPC >12 months | ||||

| ECOG Status at first-line | 1+ vs 0 | 43 | 1.38 (0.62, 3.05) | 0.43 |

| Site of Metastases | Visceral Disease vs No | 0.96 (0.44, 2.13) | 0.93 | |

| Hemoglobin | In Normal Range vs No | 0.58 (0.23, 1.45) | 0.24 | |

| First-line Chemotherapy | Cisplatin | 1.88 (0.82, 4.35) | 0.14 | |

Addition of clinical trial status as a factor was not significant (p=0.22).

Interaction term between cisplatin status and time from peri-op to first-line therapy was not significant (p=0.30).

Figure 1.

shows the effect of TFPC on OS when patients are subcategorized into <12 months and 12+ months. Time from peri-operative chemotherapy to first-line chemotherapy was significantly prognostic for OS (HR 0.39, 95% CI, 0.21, 0.75, p=0.004). Analyses were adjusted for ECOG status, presence of visceral metastases and hemoglobin.

After adjusting for ECOG-PS, TFPC, anemia status and presence of visceral metastases, first-line cisplatin-based chemotherapy was a statistically significant poor prognostic factor for OS (HR=1.86, 95% CI=1.13 to 3.06; p=0.015). No significant interaction was observed between cisplatin-based treatment and TFPC at 12 months (p=0.30) or 18 months (p=0.52).

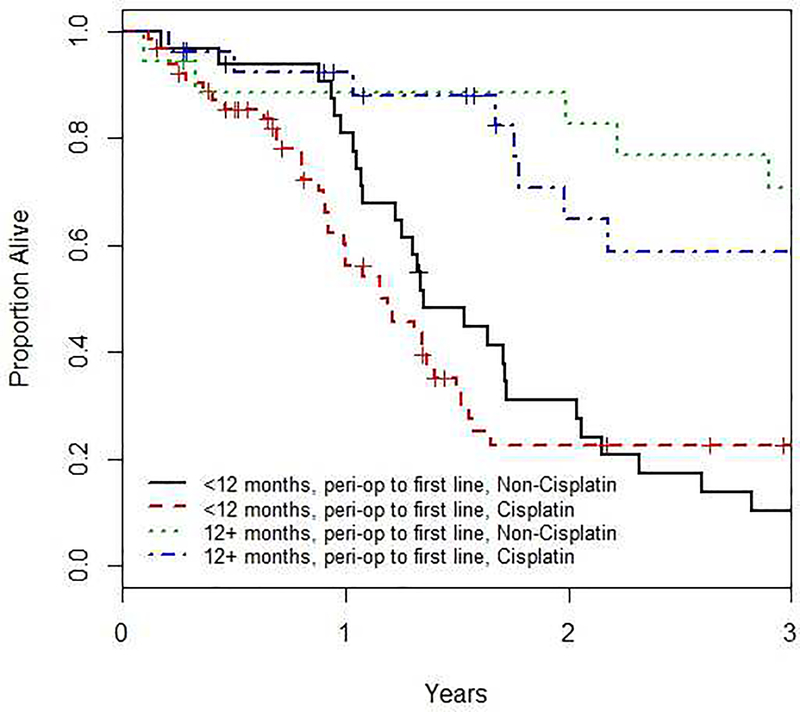

The interaction term between cisplatin treatment and TFPC was not statistically significant (p=0.61), however, the estimated HR for cisplatin treatment amongst patients with TFPC ≤12 months was 1.14, indicative of worse outcome for those treated with cisplatin. In contrast, the HR for cisplatin treatment amongst patients with TFPC >12 months was 0.75, indicative of improved outcomes amongst cisplatin treated patients. For those patients with TFPC ≤12 months, re-treatment with cisplatin in the first-line setting was associated with statistically significantly worse (HR=3.38, p<0.001) OS, while the effect was reduced (HR=1.88) and non-significant (p=0.14) amongst patients with TFPC >12 months (see Table 3 and Figure 2).

Figure 2.

shows the effect of TFPC on OS when patients are subcategorized into <12 months, 12+ months, first-line cisplatin and first-line non-cisplatin. Time from peri-operative chemotherapy to first-line chemotherapy was significantly prognostic for OS regardless of whether first-line cisplatin was used (HR 0.421, 95% CI 0.23, 0.76, p=0.004) or not (HR 0.39, 95% CI 0.21, 0.75, p=0.004).

Association of variables with PFS

The results of univariate and multivariable Cox analyses on PFS are shown in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. In the univariate analysis, TFPC using the 78-week cut point (Hazard Ratio (HR)=0.58, 95% Confidence Interval (CI)=0.38 to 0.89, p=0.013), ECOG-PS (HR=1.69, 95% CI=1.19 to 2.42, p=0.004), WBC (HR=1.52, 95% CI=1.06 to 2.16, p=0.022), clinical trial status (HR=2.00, 95% CI=1.07 to 3.74, p=0.030) and peri-operative chemotherapy type (GC HR=0.95, 95% CI=0.60 to 1.50; MVAC HR=0.47, 95% CI=0.27 to 0.82, versus other cisplatin-based chemotherapies, p-value=0.005) were all statistically significant. The effect of peri-operative chemotherapy type on PFS was evaluated adjusting for first-line ECOG-PS with similar results (data not shown). No obvious cut point for TFPC was observed after examining martingale residual plots, and no interaction between TFPC at either 12 months (p-value=0.59) or 18 months (p-value=0.53) with cisplatin first-line therapy was observed, so 1-year was selected based on practical considerations. After adjusting for ECOG-PS, site of metastases, anemia and TFPC, type of first-line chemotherapy (cisplatin vs. non-cisplatin) was not statistically significantly associated with PFS (HR=0.92, 95% CI=0.61 to 1.40, p=0.70 for cisplatin-based chemotherapies). The estimated HR for PFS was >1 for patients with TFPC ≤12 months, while it was <1 for those patients with TFPC >12 months (Table 5).

Table 4.

Prognostic Factors for PFS (Univariate)

| Factor | N | Hazards Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female vs Male | 145 | 0.76 (0.50, 1.15) | 0.19 |

| Peri-operative Chemo | Adjuvant vs Neoadjuvant | 141 | 1.03 (0.72, 1.47) | 0.88 |

| Peri-operative Chemo Type | GC | 141 | 0.95 (0.60, 1.50) | 0.005 |

| MVAC | 0.47 (0.27, 0.82) | |||

| Other Cisplatin-Based | Reference | |||

| Number of Cycles | Continuous | 140 | 1.00 (0.88, 1.15) | 0.95 |

| Site of Metastases | Visceral Disease vs No | 145 | 0.90 (0.64, 1.26) | 0.52 |

| Time Peri-op to first-line | Log-transformed |

141 | 0.97 (0.88, 1.07) |

0.58 |

| >6 vs ≤6 |

0.90 (0.63, 1.26) |

0.53 |

||

| >12 vs ≤12 |

0.73 (0.50, 1.06) |

0.094 |

||

| >18 vs ≤18 | 0.58 (0.38, 0.89) | 0.013 | ||

| Age first-line | Continuous | 141 | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | 0.098 |

| Weight at first-line, kg | Continuous | 94 | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.61 |

| ECOG Status at first-line | 1+ vs 0 | 135 | 1.69 (1.19, 2.42) | 0.004 |

| Creatinine Clearance | ≥60 ml/min vs <60 | 126 | 0.93 (0.63, 1.38) | 0.71 |

| Hemoglobin | In Normal Range vs No | 138 | 0.94 (0.66, 1.32) | 0.71 |

| WBC | >ULN vs No | 131 | 1.52 (1.06, 2.16) | 0.022 |

| Albumin | Continuous | 63 | 1.02 (0.64, 1.63) | 0.94 |

| First-line Chemotherapy | Cisplatin | 145 | 0.76 (0.53, 1.08) | 0.12 |

| First-line Chemotherapy | Clinical Trial | 145 | 2.00 (1.07, 3.74) | 0.030 |

| Frequency of first-line Chemotherapy | Ordinal | 140 | 1.26 (0.72, 2.20) | 0.42 |

| First-line Non-Cisplatin Patients* | ||||

| Time Peri-op to first-line | >12 vs ≤12 months | 50 | 0.88 (0.48, 1.60) | 0.67 |

| Time Peri-op to first-line | >18 vs ≤18 months | 50 | 0.73 (0.39, 1.39) | 0.34 |

| First-line Cisplatin Patients* | ||||

| Time Peri-op to first-line | >12 vs ≤12 months | 91 | 0.63 (0.39, 1.02) | 0.059 |

| Time Peri-op to first-line | >18 vs ≤18 months | 91 | 0.46 (0.26, 0.82) | 0.009 |

Interaction term between cisplatin status and time from peri-op to first-line therapy was not significant (12 months p=0.59 and 20 months p=0.53).

Table 5.

Prognostic Factors for PFS (Multivariable)

| Factor | N | Hazards Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients†* | ||||

| ECOG Status at first-line | 1+ vs 0 | 128 | 1.73 (1.14, 2.62) | 0.010 |

| Site of Metastases | Visceral Disease vs No | 1.01 (0.70, 1.47) | 0.95 | |

| Hemoglobin | In Normal Range vs No | 0.76 (0.52, 1.12) | 0.16 | |

| Time Peri-op to first-line | >12 vs ≤12 months | 0.63 (0.41, 0.95) | 0.027 | |

| First-line Chemotherapy | Cisplatin | 0.92 (0.61, 1.40) | 0.70 | |

| TFPC ≤12 months | ||||

| ECOG Status at first-line | 1+ vs 0 | 85 | 2.42 (1.44, 4.04) | <0.001 |

| Site of Metastases | Visceral Disease vs No | 0.91 (0.58, 1.44) | 0.70 | |

| Hemoglobin | In Normal Range vs No | 0.78 (0.48, 1.27) | 0.33 | |

| First-line Chemotherapy | Cisplatin | 1.14 (0.66, 1.95) | 0.64 | |

| TFPC >12 months | ||||

| ECOG Status at first-line | 1+ vs 0 | 43 | 1.09 (0.53, 2.26) | 0.81 |

| Site of Metastases | Visceral Disease vs No | 1.17 (0.57, 2.40) | 0.67 | |

| Hemoglobin | In Normal Range vs No | 0.65 (0.32, 1.34) | 0.24 | |

| First-line Chemotherapy | Cisplatin | 0.75 (0.37, 1.52) | 0.42 | |

Addition of clinical trial status as a factor was not significant (p=0.68).

Interaction term between cisplatin status and time from peri-op to first-line therapy was not significant (p=0.61).

Discussion

The optimal selection of chemotherapy for recurrent metastatic UC following prior peri-operative cisplatin-based chemotherapy remains a significant area of uncertainty 9–11. Specifically, the impact of reinstituting cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy versus a different noncisplatin-based first-line combination chemotherapy regimen versus a second-line generally single agent therapy is unclear. This retrospective study including 145 patients from 12 different institutions aimed to shed light on this issue. The study assembled patients treated at multiple institutions, because of the difficulty of identifying a large cohort of such patients from a single institution. As this is a retrospective analysis, the analyses accounted for the impact of known prognostic factors in the first-line and/or salvage settings, notably presence of visceral disease, hemoglobin (Hb) level, patient performance status, leukocytosis, albumin and time from prior peri-operative chemotherapy (TFPC) were incorporated in this analysis based on their demonstrated prognostic impact in previous reports 12–14. The major finding of our study is that reinstituting cisplatin-based first-line chemotherapy after PCBC may have a detrimental impact on OS, especially on those within 12 months of prior therapy. However, cisplatin-based first-line chemotherapy was not associated with poorer PFS. Nevertheless, these data cast doubts on the viability and utility of reinstituting cisplatin-based first-line chemotherapy in those previously exposed to PCBC.

Interestingly, the type of peri-operative chemotherapy was observed to be a significant prognostic factor for OS and PFS on univariate analyses only, although we hasten to point out that this may well be resultant of patient selection factors. Patients treated with peri-operative GC had a worse prognosis compared with patients treated with MVAC. Since GC is more tolerable than MVAC, the latter may select for patients with a better initial health status and fewer comorbidities. Other factors (e.g. social support) could not be captured in this retrospective review, and likely also confound the interpretation of this result.

Not unexpectedly, previously recognized prognostic factors such as time from peri-operative chemotherapy to first-line therapy and ECOG-PS were significant prognostic factors for both OS and PFS 14–16. In contrast, Hb and sites of metastasis were not significant on multivariable analyses, which may be a consequence of small sample size and an underpowered analysis.

Interpretation of results from this study is limited due to its retrospective nature and modest sample size. First and foremost, numerous reasons are considered when determining a type of first-line chemotherapy for patients, much of which cannot be captured in a retrospective chart review such as this analysis. Prospective validation, ideally through a clinical trial, is necessary to determine the optimal treatment, however the relatively low prevalence that this population represents will likely preclude such a possibility. The proportion and number of patients receiving non-cisplatin-based therapy for metastatic recurrence was relatively modest and the types of non-cisplatin agents were quite varied and were categorized together. This raises the likelihood that the efficacy of specific non-cisplatin drug regimens were masked. As is common in many retrospective analyses, missing data was common, which limited the ability to explore the effects of some factors such as albumin and baseline neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR). WBC was evaluated instead of baseline neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), which is known to demonstrate prognostic capability in several oncological settings. The cause for poorer OS when repeating cisplatin-based first-line therapy after PCBC is unclear and requires further study. Lastly, some patients may choose other treatments, such as palliative care or a non-chemotherapy based clinical trial; which may limit the generalizability of these results.

Given our results, there remains some uncertainty on whether or not one should re-challenge a patient with cisplatin-based first-line therapy; however, given that the majority of patients in our dataset had recurred within 1 year of PCBC, patients relapsing <1 year after peri-operative cisplatin-based chemotherapy should probably be considered for alternative non-cisplatin or second-line treatments or clinical trials. Notably, all of the landmark phase III trials that evaluated cisplatin-based first-line chemotherapy did not include patients who had received PCBC 2,4,17,18. One prior retrospective study suggested that repeating cisplatin after >1 year from PCBC may be reasonable, although that study did not assess a differential impact of other non-cisplatin-based regimens on disease recurrence 15.

Our findings suggest that the therapeutic index of cisplatin-based first-line chemotherapy following PCBC is suboptimal. Moreover, durable complete remission by repeating cisplatin-based chemotherapy is biologically unlikely in those who recurred following PCBC. Indeed, residual renal dysfunction following PCBC may render many patients suboptimal candidates for re-challenging with cisplatin. Assuming that most appropriate and fitter cisplatin-eligible patients received first-line cisplatin (and only cisplatin-ineligible patients or those with comorbidities or poor performance received other regimens), it is somewhat worrisome that those receiving first-line cisplatin demonstrated poor OS. Thus, with the exception of those with a long time from PCBC (>12 months) and no residual toxicities of cisplatin such as renal dysfunction and neurotoxicity, re-challenging with cisplatin should probably not be considered.

Conclusions

This hypothesis-generating retrospective analysis demonstrated that re-challenging patients who progressed following PCBC for UC, especially those progressing within a year, with cisplatin appears ill advised. Further validation in a larger dataset is warranted.

Clinical Practice Points.

The optimal selection of chemotherapy for recurrent metastatic UC following prior peri-operative cisplatin-based chemotherapy remains a significant area of uncertainty.

In a multicenter retrospective study we demonstrate that reinstituting cisplatin-based first-line chemotherapy after PCBC may have a detrimental impact on OS, especially on those within one year of prior therapy.

In future practice, these results cast doubts on the viability and utility of reinstituting cisplatin-based first-line chemotherapy in those previously exposed to PCBC.

Footnotes

Disclosure:

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sternberg CN, de Mulder P, Schornagel JH, et al. Seven year update of an EORTC phase III trial of high-dose intensity M-VAC chemotherapy and G-CSF versus classic M-VAC in advanced urothelial tract tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(1):50–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von der Maase H, Sengelov L, Roberts JT, et al. Long-term survival results of a randomized trial comparing gemcitabine plus cisplatin, with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, plus cisplatin in patients with bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(21):4602–4608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sternberg CN, Yagoda A, Scher HI, et al. Preliminary results of M-VAC (methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin and cisplatin) for transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelium. J Urol. 1985;133(3):403–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loehrer PJ S, Einhorn LH, Elson PJ, et al. A randomized comparison of cisplatin alone or in combination with methotrexate, vinblastine, and doxorubicin in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma: A cooperative group study. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(7):1066–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von der Maase H, Hansen SW, Roberts JT, et al. Gemcitabine and cisplatin versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in advanced or metastatic bladder cancer: Results of a large, randomized, multinational, multicenter, phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(17):3068–3077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta S, Mahipal A. Role of systemic chemotherapy in urothelial urinary bladder cancer. Cancer Control. 2013;20(3):200–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Izawa JI, Chin JL, Winquist E. Timing cystectomy and perioperative chemotherapy in the treatment of muscle invasive bladder cancer. Can J Urol. 2006;13 Suppl 3:48–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellmunt J, von der Maase H, Mead GM, et al. Randomized phase III study comparing paclitaxel/cisplatin/gemcitabine and gemcitabine/cisplatin in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer without prior systemic therapy: EORTC intergroup study 30987. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(10):1107–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carballido EM, Rosenberg JE. Optimal treatment for metastatic bladder cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2014;16(9):404–014-0404–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim JJ. Recent advances in treatment of advanced urothelial carcinoma. Curr Urol Rep. 2012;13(2):147–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JH, Kang SG, Kim ST, et al. Modified MVAC as a second-line treatment for patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma after failure of gemcitabine and cisplatin treatment. Cancer Res Treat. 2014;46(2):172–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galsky MD, Pal SK, Chowdhury S, et al. Comparative effectiveness of gemcitabine plus cisplatin versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, plus cisplatin as neoadjuvant therapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cancer. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Apolo AB, Ostrovnaya I, Halabi S, et al. Prognostic model for predicting survival of patients with metastatic urothelial cancer treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(7):499–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sonpavde G, Pond GR, Fougeray R, et al. Time from prior chemotherapy enhances prognostic risk grouping in the second-line setting of advanced urothelial carcinoma: A retrospective analysis of pooled, prospective phase 2 trials. Eur Urol. 2013;63(4):717–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Necchi A, Pond GR, Giannatempo P, et al. Cisplatin-based first-line therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma after previous perioperative cisplatin-based therapy. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pond GR, Bellmunt J, Rosenberg JE, et al. Impact of the number of prior lines of therapy and prior perioperative chemotherapy in patients receiving salvage therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma: Implications for trial design. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2015;13(1):71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellmunt J, von der Maase H, Mead GM, et al. Randomized phase III study comparing paclitaxel/cisplatin/gemcitabine and gemcitabine/cisplatin in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer without prior systemic therapy: EORTC intergroup study 30987. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(10):1107–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sternberg CN, de Mulder PH, Schornagel JH, et al. Randomized phase III trial ofhigh-dose-intensity methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (MVAC) chemotherapy and recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor versus classic MVAC in advanced urothelial tract tumors: European organization for research and treatment of cancer protocol no. 30924. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(10):2638–2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]