Abstract

Background: Previous research has suggested that gender diversity affects everyone in the family, with positive mental health and global outcomes for gender diverse youth reliant on receiving adequate family support and validation. Although the individual mental health, treatment and outcomes for gender diverse youth have received recent research attention, much less is known about a family perspective. Hence, a review of the literature exploring youth gender diversity from a family perspective is warranted.

Aims: To systematically identify, appraise and summarize all published literature primarily exploring gender diversity in young people under the age of 18 years, as well as selected literature pertaining to a family understanding.

Methods: Six electronic databases (CINAHL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, SCOPUS, Web of Science) were searched for relevant literature pertaining to youth under the age of 18 years.

Results: Research evidence was consistently found to support the beneficial effects of a supportive family system for youth experiencing gender diversity, and a systemic understanding and approach for professionals. Conversely, lack of family support was found to lead to poorer mental health and adverse life outcomes. Few articles explored the experience of siblings under the age of 18 years.

Discussion: This literature review is the first to critically evaluate and summarize all published studies which adopted a family understanding of youth gender diversity. The review highlighted a lack of current research and the need for further targeted research, which utilizes a systemic clinical approach to guide support for gender diverse youth and family members.

Key Words: gender diversity, youth, family, sibling, parent, mental health, support

Introduction

Many gender diverse children and adolescents experience a mismatch between their gender assigned at birth and their experienced or true gender self (Ehrensaft, 2011). Gender diversity is known to affect everyone in the family in varied, unexpected and often significant ways. Given that most gender diverse youth remain reliant on the family for varied forms of support in adolescence and beyond, a family understanding is merited. There has been a noticeable increase in coverage of youth gender diversity by academic journals and the media, and an increase in individuals presenting with gender-related issues (Deutsch, 2016; Goldberg, 2017; Katz-Wise et al., 2017; Reilly, Desousa, Garza-Flores, & Perrin, 2019; Turban & Ehrensaft, 2018). It has been estimated that up to 1.2% of young people of high school age identify as transgender (Clark et al., 2014). Incidentally, the number of referrals of children and adolescents wishing to pursue gender affirming medical and surgical treatments in Australia and elsewhere has been increasing exponentially (Aitken et al., 2015; Butler, De Graaf, Wren, & Carmichael, 2018; Spack et al., 2012; Telfer, Tollit, & Feldman, 2015; Wood et al., 2013). It is therefore imperative that service providers and professionals better understand the issues affecting these young people and their families. To date, few researchers have specifically examined individual family members’ experiences within a family context involving siblings (Coolhart, Ritenour, & Grodzinski, 2018; Norwood, 2012, 2013b; Zamboni, 2006).

Early understanding of self, others and the larger world is created within the context of the family system and associated relationships. It is already known that poorer family functioning can lead to increased mental health difficulties and worse psychosocial outcomes for children and young people generally (Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009; Umberson & Karas Montez, 2010). Conversely, family structures that provide essential nurture and protection from harm contribute to healthier individual functioning (Carr & Springer, 2010; Resnick et al., 1997; Umberson, Thomeer, & Williams, 2013). The family system can be conceptualized as an essential ‘psychological buffer’ to help children and young people navigate necessary developmental and social challenges (Telzer, Fuligni, Lieberman, & Galván, 2013; Walsh, 2002).

Several studies have confirmed the fundamental importance of family support for improving gender diverse youths’ mental health and fostering resilience (McConnell, Birkett, & Mustanski, 2016; Olson, Durwood, DeMeules, & McLaughlin, 2016; Sansfaçon et al., 2018; Sansfaçon, Robichaud, & Dumais-Michaud, 2015; Simons, Olson, Belzer, Clark, & Schrager, 2012; Simons, Schrager, Clark, Belzer, & Olson, 2013; Travers et al., 2012). Nonetheless, there seems to be little research that has adopted a family approach, encompassing all family member viewpoints. Importantly, the family can also be the source of “culturally imbued transphobia” (Ehrensaft, 2011, p. 530) and microaggressions from within (Gartner & Sterzing, 2018; Parker, Hirsch, Philbin, & Parker, 2018). Cultural beliefs, religion, social context and conceptual understandings of gender identity and expression may influence family member responses and acceptance. Consequently, the issues faced by families and individual family members of gender diverse young people can therefore be complex, multi-faceted and unique, and are worthy of investigation (Hill & Menvielle, 2009).

The literature review aimed to systematically identify, appraise and summarize all literature involving a family or systemic (pertaining to the family system and wider social systems) understanding of youth experiencing gender diversity under the age of 18 years. Furthermore, the literature review aimed to highlight and promote the importance of a systemic understanding and approach for all professionals working with gender diverse youth and their families.

Methods

Type and focus of review: the literature review broadly identified all published research literature relating to youth gender diversity (under 18 years) within a family context. The review followed a five-step process of literature search, identification, data evaluation, data analysis and presentation of integrated findings.

Protocol: Six chosen databases were searched in April 2019: CINAHL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, SCOPUS and Web of Science. A range of search terms, synonyms and Boolean technique using AND/OR operators were used to ensure the different nomenclature captured relevant literature (see Tables 1 and 2) and adapted for each database. Searches were initially performed in the abstract or keyword domains. However, this was found to be ineffective; while the search terms were present, the primary focus of the articles retrieved were generally irrelevant to this literature review. Therefore, search terms were confined to the title domain. This process was repeated immediately prior to submission of this manuscript. To promote rigor, reference lists of retrieved articles were searched manually to identify additional articles of interest not captured by the search strategy. Each of the articles retrieved was assessed for relevance by reading the abstract and the whole article if necessary.

Table 1.

Search terms used within the six databases.

| Gender diversity | gender divers* gender dysphoria gender varian* gender identity disorder transsexual* transgender* gender expansive gender creative gender nonconforming LGBT1* LGBTQ2* gender queer gender fluid gender independent gender minority |

| Child | child* adolescen* youth teen* |

| Family | family familial systemic parent* mother father caregiver carer* sibling* brother* sister* |

1Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender.

2Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Questioning.

Table 2.

Individual database searches and results.

| Database: date of initial search | Terms/keywords with Boolean operators | Number of citations retrieved |

|---|---|---|

| PsycINFO 25/04/2019 No date limitations (1806-2019) |

Gender dysphoria OR gender varian* OR gender identity disorder OR gender divers* or transsexual* OR transgender* OR gender expansive OR gender creative or gender nonconforming OR gender minority OR LGBT3* OR LGBTQ4* OR gender queer OR gender fluid OR gender independent | 11535 (keyword) 5330 (title) |

| AND child* OR youth OR teen* OR adolescen* | 3160 (keyword) 782 (title) |

|

| AND family OR parent* OR carer* OR caregiver OR systemic OR familial OR brother* OR sister* Or sibling* OR families OR systemic | 1355-(keyword) 129-(title) |

|

| Web Of Science: 25/4/19 No date limitations (1945-2019) |

Gender dysphoria OR gender varian* OR gender identity disorder OR gender divers* or transsexual* OR transgender* OR gender expansive OR gender creative or gender nonconforming OR gender minority OR LGBT* OR LGBTQ* OR gender queer OR gender fluid OR gender independent | 80082 (topic) 6030 (title) |

| AND child* OR youth OR teen* OR adolescen* | 16581(topic) 691 (title) |

|

| AND family OR parent* OR carer* OR caregiver OR systemic OR familial OR brother* OR sister* Or sibling* OR families OR systemic | 5711 (topic) 87 (title) |

|

| Scopus: 25/4/19 (title) No date limitations (1966-2019) #1 |

Gender dysphoria OR gender varian* OR gender identity disorder OR gender divers* or transsexual* OR transgender* OR gender expansive OR gender creative or gender nonconforming OR gender minority OR LGBT* OR LGBTQ* OR gender queer OR gender fluid OR gender independent | 30541 (title/abstract/key words) 1973 (title) |

| Scopus: 25/4/19 #2 |

AND child* OR youth OR teen* OR adolescen* | #1 AND #2 10115 (title/abstract/key words) 272 (title) |

| Scopus: 25/4/19 #3 |

AND family OR familial OR families OR parent* OR carer* OR caregiver OR sibling* OR brother* OR sister* OR systemic | (#1 AND #2) AND #3 3590 (title/abstract/key words) 23 (title) |

| CINAHL 25.4.19 #1 No date limitations (1986-2019) |

Gender dysphoria OR gender varian* OR gender identity disorder OR gender divers* or transsexual* OR transgender* OR gender expansive OR gender creative or gender nonconforming OR gender minority OR LGBT* OR LGBTQ* OR gender queer OR gender fluid OR gender independent | 5789 (abstract) 1243 (title) |

| CINAHL 25.4.19 #2 |

AND Child* OR youth OR teen* OR adolescen* | #1 AND #2 = 1228 (abstract) 227 (title) |

| CINAHL 25.4.19 #3 |

AND family OR families OR familial OR systemic OR parent* OR sibling* OR brother* OR sister* OR caregiver* OR carer* OR caregiver | (#1 AND #2) AND #3 = 475 (abstract) 39 (title) |

| MEDLINE via OVID 25.4.19 No date limitations (1946-2019) |

Gender dysphoria OR gender varian* OR gender identity disorder OR gender divers* or transsexual* OR transgender* OR gender expansive OR gender creative or gender nonconforming OR gender minority OR LGBT* OR LGBTQ* OR gender queer OR gender fluid OR gender independent | 9775 (keyword) 3825 (title) |

| MEDLINE via OVID 25.4.19 | AND Child* OR youth OR teen* OR adolescen* | 2887 (keyword) 446 (title) |

| MEDLINE via OVID 25.4.19 | AND family OR families OR familial OR systemic OR parent* OR sibling* OR brother* OR sister* OR caregiver* OR carer* OR caregiver | 729 (keyword) 45 (title) |

| EMBASE 25.4.19 No date limitations (1974-2019) |

Gender dysphoria OR gender varian* OR gender identity disorder OR gender divers* or transsexual* OR transgender* OR gender expansive OR gender creative or gender nonconforming OR gender minority OR LGBT* OR LGBTQ* OR gender queer OR gender fluid OR gender independent | 12159 (keyword) 5583 (title) |

| EMBASE 25.4.19 | AND Child* OR youth OR teen* OR adolescen* | 3390 (keyword) 738 (title) |

| EMBASE 25.4.19 | AND family OR families OR familial OR systemic OR parent* OR sibling* OR brother* OR sister* OR caregiver* OR carer* OR caregiver | 1133 (keyword) 76 (title) |

3Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender.

4Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Questioning.

Eligibility criteria: search findings were limited to human research, peer reviewed journal articles in English, with no time limits imposed.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria: all research was included that involved gender diverse youth under the age of 18 years, their caregivers or parents, and siblings. In addition, research was included that involved gender diverse adults retrospectively reflecting on their adolescent years or current family circumstances, if deemed relevant. Articles including sexual minority youth LGBQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, questioning) were included if considered relevant to gender diverse youth and their families. Unpublished theses, books and previous literature reviews were excluded, as were articles focusing specifically on causation, etiology or interventions for child or adolescent gender diversity. However, articles were included if specifically related to a family member perspective or experience.

Data extraction process and analysis: Each of the identified articles were read in full, with the main findings and themes summarized for the purposes of the literature review.

No formal ethical approval was required, given that no research participants were involved.

Results

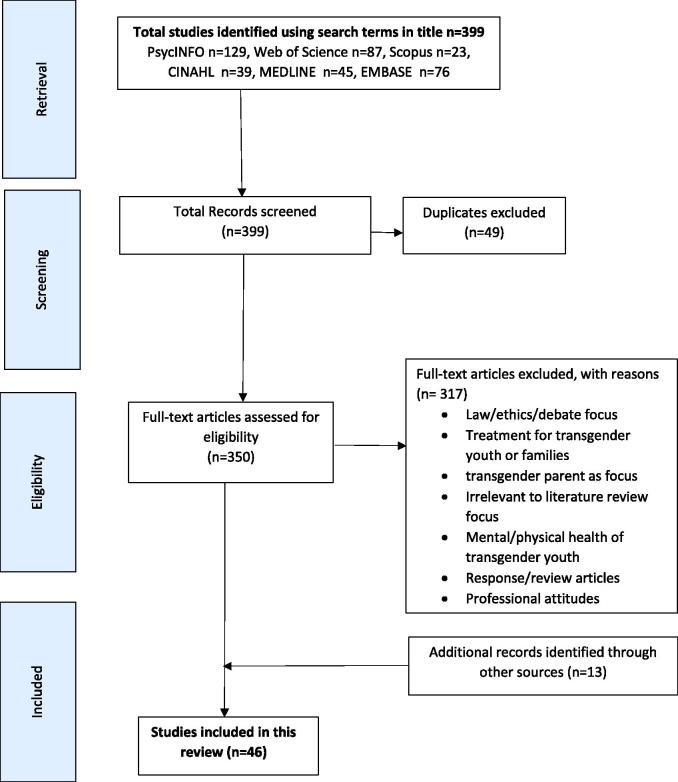

The search yielded 46 relevant studies/papers (Figure 1), undertaken in eight countries: USA (35), UK (2), Canada (4), Germany (1), Australia (4), Ireland (1), Spain (1) and Belgium (1). Details of the publications can be found in Table 3. Four were discussion papers and did not include actual research participants but were felt to offer valuable insights to the literature review overall (Connolly, 2005; Ehrensaft, 2011; Emerson & Rosenfeld, 1996; Katz-Wise, Rosario, & Tsappis, 2016). Three studies were multi-centre: Spain and Belgium, USA and Canada, and Canada, Ireland and USA (Catalpa & McGuire, 2018; Dierckx & Platero, 2018; Mehus, Watson, Eisenberg, Corliss, & Porta, 2017). Studies included various participants: parents or caregivers (24), followed by youth experiencing gender diversity (18), adults experiencing gender diversity (4), siblings under 18 years (3), adult siblings (2) and professionals (1). Only seven studies involved more than one family member from the same family. The age of youth participants ranged from 5 to 26 years, while parent or caregiver responses related to children and youth between the ages of 4 and 22 years inclusive.

Figure 1.

PRISMA literature review flowchart.

Table 3.

Overview of included publications.

| Study title, country, author and year | Design | Participants | Themes, findings and recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supporting families of transgender children/youth: parents speak on their experiences, identity and views. USA (Aramburu Alegria, 2018) |

Longitudinal, qualitative study | 14 parents of transgender children aged 6-17 years | Themes

|

| Transgressing the gendered norms in childhood: Understanding transgender children and their families. USA (Barron & Capous-Desyllas, 2017) |

Qualitative case study and ethnographic techniques | 4 families, involving all family members: parents, siblings aged 6-8 years, transgender children aged 5-8 years | Themes

|

| Parent experiences of a child’s social transition: moving beyond the loss narrative. USA (Bull & D’Arrigo-Patrick, 2018) |

Phenomenological study- analyzed data from hermeneutic perspective | 8 parents, facilitated social transition for children 4-12 years | Themes

|

| Family Boundary ambiguity among transgender youth. USA, Ireland, Canada (Catalpa & McGuire, 2018) |

Ethnographic content analysis, recruited from community centers, 10 cities across 3 countries | 90 transgender youths aged 15-26 years | Themes

|

| Experiences of gender minority stress in cisgender parents of transgender/gender-expansive prepubertal children: A qualitative approach. USA (Chen, Hidalgo, & Garofalo, 2017) |

Qualitative study using focus groups | 30 parents of transgender and gender expansive children less than 11 years | Finding

|

| A process of change: The intersection of the GLBT5 individual and their family of origin. USA (Connolly, 2005) |

Discussion paper | Finding

|

|

| Experiences of ambiguous loss for parents of transgender male youth: A phenomenological exploration. USA (Coolhart, Ritenour and Grodzinski, 2018) |

Interpretive phenomenological analysis | 6 parents of youth aged 14-19 years | Themes

|

| The meaning of trans* in a family context. Spain and Belgium (Dierckx & Platero, 2018) |

Qualitative, grounded theory study in Belgium and Spain, life stories- experiences of parents and children transitioning | 15 transgender children 5-19 years 15 parents | Findings

|

| Boys will be girls, girls will be boys. Children affect parents as parents affect children in gender non-conformity. USA (Ehrensaft, 2011) |

Discussion paper | Themes

|

|

| Stages of adjustment in family members of transgender individuals. USA (Emerson & Rosenfeld, 1996) |

Discussion paper | Findings

|

|

| Parenting transgender children in PFLAG.6 USA (Field & Mattson, 2016) |

14 interviews with parents, coded for themes | 14 parents of individuals aged 10-49 years | Findings

|

| Social ecological correlates of family-level interpersonal and environmental microaggressions toward sexual and gender minority adolescents. USA (Gartner & Sterzing, 2018) |

Internet based anonymous survey using Likert scales | 1,177 LGBTQ7 adolescents 14-19 years old | Findings

|

| The positive aspects of being the parent of an LGBTQ child. USA (Gonzalez et al., 2013) |

Online Survey | 142 parents of children/individuals aged 4-56 years | Findings

|

| Am I doing the right thing? Pathways to parenting a gender variant child. USA (Gray et al., 2016) |

Ecological transactional approach - analyzed with grounded theory | 11 parents of children aged 5-13 years | Themes

|

| Understanding the experience of parents of pre-pubescent children with gender identity issues. UK (Gregor, Hingley-Jones, & Davidson, 2015) |

Free association narrative interviews- constructivist version of grounded theory | 8 parents of children aged 6-10 years | Themes

|

| Parents’ reactions to transgender youths’ gender nonconforming expression and identity. USA (Grossman et al., 2005) |

Individual interviews and questionnaires | 55 transgender youth aged 15-21 years | Findings

|

| You have to give them a place where they feel protected and safe and loved: the views of parents. USA (Hill & Menvielle, 2009) |

Telephone interviews | 42 parents of 31 transgender youth aged 4-17.5 years (over half adopted). | Findings

|

| Communication of acceptance and support in families who have gender-variant youth. USA (Libby at al., 2019) |

Qualitative study using grounded theory analysis | 5 parent-adolescent dyads. Adolescents aged 14-20 years | Findings

|

| Lesbian, Gay, bisexual, and Transgender youth and family acceptance. USA (Katz-Wise, Rosario, & Tsappis, 2016) |

Discussion paper | Recommendations

|

|

| Transactional pathways of transgender identity development in transgender and gender-nonconforming youth and caregiver perspectives from the Trans Youth Family Study. USA (Katz-Wise et al., 2017) |

Qualitative interviews using respondent narratives | 16 transgender youth aged 7-18 years 29 caregivers |

Themes

|

| Family functioning and mental health of transgender and gender-nonconforming youth in the trans teen and family narratives project. USA (Katz-Wise et al., 2018) |

Longitudinal study Measured family communication/family satisfaction of transgender youth, parents, siblings using (FACES IV) Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales- recruited from community-based resources | 33 transgender youth 13-17 years, 15 siblings 14-24 years, 48 parents | Findings

|

| Child, Family, and Community Transformations: Findings from Interviews with Mothers of Transgender Girls. USA (Kuvalanka, Weiner, & Mahan, 2014) |

Individual interviews, inductive thematic analysis | 5 mothers of transgender girls 8-11 years | Themes

|

| Risk factors for psychological functioning in German adolescents with gender dysphoria: poor peer relations and general family functioning. Germany (Levitan et al., 2019) |

Cross-sectional, questionnaire-based, single-subject study design using youth self-report, McMasters Family Assessment Device (MFAD) | 180 adolescents, mean age 15.5 years | Findings

|

| Families matter: social supports and mental health trajectories among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. USA (McConnell, Birkett, & Mustanski, 2016) |

Longitudinal study over 5.5 years, using rating scales | 232 LGBT youth aged 16-20 years | Findings

|

| ‘Deep down where the music plays’: How parents account for childhood gender variance. USA (Meadow, 2011) |

Qualitative interviews | 49 parents of children aged 4-18 years | Findings

|

| Living as an LGBTQ adolescent and a parent’s child: Overlapping or separate experiences. USA and Canada (Mehus et al., 2017) |

Qualitative using open ended questions | 66 LGBTQ adolescents aged 14-19 years | Findings

|

| Transitioning meanings? Family members communicative struggles surrounding transgender identity. USA (Norwood, 2012) |

Analysis of online postings re transgender identity and transition- using relational dialectics approach - struggle between different meanings | 63 individuals (age over 18) | Themes

|

| Grieving gender: Trans-identities, Transition, and Ambiguous loss. USA (Norwood, 2013) |

Relational dialectics- social world system of competing discourses | 37 interviews – parents, siblings, children of transgender persons (no age specified, although likely adults) | Themes

|

| Meaning matters: framing trans identity in the context of family relationships. USA (Norwood, 2013) |

Qualitative, dialogic analysis, using ‘authoring’ | Telephone interview of 35 family members of trans individuals | Themes

|

| Experiences regarding coming out to parents among African American, Hispanic, and white gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and questioning adolescents. USA (Potoczniak, Crosbie-Burnett, & Saltzburg, 2009) |

Qualitative study using focus groups, grounded theory and naturalistic enquiry | LGBT adolescents aged 14-18 years | Themes

|

| The gender binary meets the gender variant child: parent’s negotiations with childhood gender variance. USA (Rahilly, 2015) |

Qualitative interviews using Foucault’s nation of ‘truth regime’ to conceptualize the gender binary | 24 parents of youth 5-19 years | Themes

|

| Support experiences and attitudes of Australian parents of gender variant children. Australia (Riggs & Due, 2015) |

Scoping study, mixed methods, using internet survey | 61 parents of children 4-18 years | Findings

|

| The needs of gender-variant children and their parents: A parent survey. Australia (Riley at al., 2011) |

Internet survey- content analysis and reflective-interpretive process | 31 parents of children <12 years | Themes

|

| Recognising the needs of gender-variant children and their parents. Australia (Riley et al., 2013) |

Online survey Grounded theory and content/thematic analysis | 31 parents of children <12 years, 29 professionals and 110 transgender adults | Findings

|

| Surviving a gender variant childhood: the views of transgender adults on the needs of gender variant children and their parents. Australia (Riley et al., 2013) |

Semi-structured, qualitative internet survey- analyzed by content and thematic coding | 110 transgender adults | Findings

|

| “Family support would have been like amazing”: LGBTQ youth experiences with parental and family Support. USA (Roe, 2017) |

Phenomenological analysis of individual interviews | 7 LGB adolescents 16-18 years | Findings

|

| Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT adults. USA (Ryan et al., 2010) |

Quantitative study 9% transgender participants 21-25 years | 245 participants aged 21-25 years, reflecting on age 13-19 years | Findings

|

| Examining the Family Transition: How parents of gender-diverse youth develop trans affirming attitudes. USA (Ryan, 2017) |

Guided by Ridgeway’s theory of gender primarily organizing social life | 36 parents, in-depth interviews of preschool children | Themes

|

| The experience of parents who support their children’s gender variance. Canada (Sansfacon, Robichaud, & Dumais-Michaud, 2015) |

Qualitative action research, using grounded theory | 14 parents of children aged 4-13 years | Themes

|

| Youth and caregiver experiences of gender identity transition: a qualitative study. USA (Schimmel-Bristow et al., 2018) |

Qualitative, semi-structured interview or focus group discussion | 15 transgender youth aged 14-22 years 18 caregivers of transgender youth 22 years or younger | Findings

|

| The relationship between parental support and depression and suicidality in transgender adolescents. USA (Simons et al., 2012) |

Computer based survey using Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), suicidality and support questionnaires | 28 transgender adolescents aged 15-24 years | Finding

|

| Parental support and mental health among transgender adolescents. USA (Simons et al., 2013) |

Used family subscale of multidimensional scale of perceived social support, linear regression analysis | 66 transgender youth 12-24 years presenting for care LA children’s hospital | Findings

|

| Impacts of strong parental support for trans youth: a report prepared for the children’s Aid society of Toronto. Canada (Travers et al., 2012) |

Internet survey | 84 socially transitioned youth aged 16-24 years | Findings

|

| Family matters: transgender and gender-diverse people’s experience with family when they transition. Australia (von Doussa, Power, & Riggs, 2017) |

Qualitative- interviews | 13 transgender adults | Findings

|

| Understanding more about how young people make sense of their siblings changing gender identity: How this might affect their relationships with their gender-diverse siblings and their experiences. UK (Wheeler et al, 2019) |

Qualitative semi-structured interviews | 8 siblings, aged 11-25 years, of gender diverse youth aged 8-18 years | Themes

|

| ‘I can accept my child is transsexual, but if ever see him in a dress I’ll hit him’: dilemmas in parenting a transgender adolescent. USA (Wren, 2002) |

Qualitative study analyzed using grounded theory | 11 families of gender diverse youth aged 14-19 years, no siblings | Themes

|

5Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender.

6Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays.

7Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Questioning.

Despite geographical, cultural and healthcare differences, research themes and findings were largely consistent. For ease, retrieved studies will be discussed according to study participants and main themes identified, although several studies included more than one family member or theme.

Parent or caregiver experiences

In total, 16 studies involving between 5 to 142 parent or caregiver participants were found that focused solely on the experiences of parents or carers of gender diverse young people, between the ages of 4 to 19 years (Aramburu Alegría, 2018; Bull & D’Arrigo-Patrick, 2018; Coolhart et al., 2018; Field & Mattson, 2016; Gonzalez, Rostosky, Odom, & Riggle, 2013; Gray, Sweeney, Randazzo, & Levitt, 2016; Gregor, Hingley-Jones, & Davidson, 2015; Hidalgo & Chen, 2019; Hill & Menvielle, 2009; Kuvalanka, Weiner, & Mahan, 2014; Meadow, 2011; Rahilly, 2015; Riggs & Due, 2015; Riley, Sitharthan, Clemson, & Diamond, 2011; Ryan, 2017; Sansfaçon et al., 2015). However, studies by Gonzalez et al. (2013) and Field and Mattson (2016) additionally included parental experiences of gender diverse individuals spanning from childhood to adulthood. A variety of methodologies were used, including qualitative thematic analysis, mixed methods, phenomenology, free association narrative and grounded theory. In-depth individual interviews were the most frequently used way of exploring experiences, either in person or by telephone, followed by online surveys, used to gather data from the largest sample of 142 parents.

Gender diverse youth experiences

Eleven studies, ranging from 7 to 1177 youth participants, were found that specifically focused on gender diverse youths’ experiences between the ages of 12–26 years, using various methodologies: ethnographic content analysis, phenomenological analysis, quantitative approaches and internet surveys (Catalpa & McGuire, 2018; Gartner & Sterzing, 2018; Grossman, D'Augelli, Howell, & Hubbard, 2005; Levitan, Barkmann, Richter-Appelt, Schulte-Markwort, & Becker-Hebly, 2019; McConnell et al., 2016; Mehus et al., 2017; Potoczniak, Crosbie-Burnett, & Saltzburg, 2009; Roe, 2017; Simons et al., 2012; Simons et al., 2013; Travers et al., 2012). Themes emerged of acceptance versus rejection, changing identity and relationships, adjustment within the family and the need for family support.

Sibling experiences

One study was found that concentrated exclusively on siblings: 8 siblings with a gender diverse sibling were asked their experiences (Wheeler, Langton, Lidster, & Dallos, 2019). This study sought sibling opinions of the research questions in advance, utilizing an LGBTQ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Questioning) charity as part of the research design. Themes of confusion, role ambiguity, adjustment and enhanced sibling relationship were identified.

Parent and youth experiences

5 studies combined 5-29 parent or caregiver views and the views of gender diverse youth aged 7-22 years (Dierckx & Platero, 2018; Katz-Wise et al., 2017; Libby, Miller, Regan, Gruschow, & Hawkins, 2019; Schimmel-Bristow et al., 2018; Wren, 2002) using grounded theory analysis and qualitative interviewing. Indeed, Schimmel-Bristow et al. (2018) was the first in-depth study of caregiver and youth experiences, using responses from 18 caregivers and 15 gender diverse youth aged 14 -22 years.

Parent, youth and sibling experiences

Two studies were found that combined all immediate family member responses; sibling experiences under the age of 18 years with parents and youth experiencing gender diversity. In their longitudinal study, Katz-Wise, Ehrensaft, Vetters, Forcier, and Austin (2018) included 15 siblings aged 14-24 years, parents and gender diverse youth aged 13-17 years, using responses from the FACES-IV (Family adaptability and cohesion evaluation scale-IV) questionnaire. However, the research findings were limited by siblings only completing one subscale, as opposed to two. Moreover, sibling viewpoints were not found to have any correlation to the mental health of their gender diverse sibling; however, better family functioning was. A further qualitative case study using ethnographic techniques by Barron and Capous-Desyllas (2017) included two cisgender siblings aged six and eight years, whose gender diverse sibling was aged eight and five years respectively.

Family support and acceptance

Two studies explored the impact of parental support on the health and wellbeing of between 66 and 84 gender diverse youth respectively, aged 12-24 years, using quantitative questionnaires and an internet survey (Simons et al., 2013; Travers et al., 2012). Sansfaçon et al. (2015) instead explored the experience of parents who support their children’s gender variance and identified various themes ranging from facilitating understanding to experiencing invisibility and stigma. In their landmark study, Simons et al. (2013) asked 66 transgender youth their experience of parental support and documented associations between parental support, mental health and the quality of life of gender diverse youth. Parental support led to higher life satisfaction, lower perceived burden of being gender diverse and less depression. The role religion plays in coming out and whether the family is accepting or rejecting was identified by youth in three studies (Gartner & Sterzing, 2018; Potoczniak et al., 2009; Roe, 2017). In a further study focusing on family acceptance for gender diverse adolescents between 13-19 years, Ryan, Russell, Huebner, Diaz, and Sanchez (2010) used adult transgender (age 21-25 years) participants’ recollections, concluding that greater family acceptance leads to improved self-esteem, social support, general health status and is protective against depression, substance abuse and suicidal ideation and behaviors. Katz-Wise et al. (2016) conclude that more research is needed to determine the impact of parental acceptance or rejection on the health of gender diverse youth.

Collective family system experiences/interpretation

Three papers discussed potential changes within the family system as a whole, with particular reference to how parents or carers react to youth gender diversity and the bi-directional interplay of youth gender diversity on family dynamics and the wider social system (Connolly, 2005; Ehrensaft, 2011; Emerson & Rosenfeld, 1996). Indeed, Emerson and Rosenfeld (1996) were amongst the first scholars who sought to explain family member reactions using a five-stage grief paradigm model (Kübler-Ross, 1973).

Meaning making

Five studies explored ‘meaning making’ of youth gender diversity using various conceptual ‘lenses’, including ambiguous loss, whereby other family members often experience gender transition from a grief and loss perspective (Boss, 1999). Meaning making was primarily explored from a caregiver perspective, incorporating relational and individual factors. Furthermore, etiological causation was explored and collectively found to be reducible to an interplay of biological, sociocultural and normative identity development by a variety of researchers (Bull & D’Arrigo-Patrick, 2018; Katz-Wise et al., 2017; Norwood, 2012, 2013a, 2013b).

Family needs of gender diverse youth

Three online studies using qualitative (grounded theory) internet surveys focused on the needs of gender diverse children (less than 12 years) and their parents, using a non-linear approach (asking about the feelings or needs of another); 31 parents, 29 professionals and 110 transgender adults were asked about the needs of gender diverse youth and parents (Riley, Clemson, Sitharthan, & Diamond, 2013; Riley et al., 2011; Riley, Sitharthan, Clemson, & Diamond, 2013). Gender diverse youths’ needs were summarized using a HAPPINESS acronym: Heard and accepted, Professional access and support, Peer contact, Information, Not to be bullied, Expressive freedom, Safety and Support.

Studies involving research participants with gender diversity over 18 years

Five studies were included that involved adult participants, as findings were considered applicable to a youth context. In an Australian study, von Doussa, Power, and Riggs (2017) explored how gender diverse individuals experience transition within the family, while three further studies explored meaning making and loss related to trans identity within the family (Norwood, 2012, 2013a, 2013b). Riley, Clemson, et al. (2013) uniquely adopted a circular and lived approach (Selvini, Boscolo, Cecchin, & Prata, 1980) in that transgender adults were asked to think about the needs of gender diverse children and their parents, using their own lived experience.

Discussion

This review summarizes and synthesizes the available literature of youth gender diversity understood from a family or systemic context. It needs to be borne in mind that there was a noticeable absence of any literature from anywhere other than Europe, North America and Australia. This suggests that the results summarized are not necessarily comparable to family systems and cultures in Asia, Africa, The Middle East or elsewhere. This could therefore be a focus for future research. Two studies were included where the age of family member participants was unclear (Norwood, 2013a, 2013b). The literature retrieved identified consistent themes and findings in relation to youth gender diversity. Researchers attempted to understand individual family member experiences from a systemic perspective, considering the immediate and wider family context. Overarching themes identified were meaning making, carer or parental responses, lack of professional understanding or support, loss and grief, a family system understanding and family support. It is evident from the research that youth gender diversity may become both the focus and stressor for the family system, and interpersonal relationships, and the ‘filter’ through which family life is viewed (Aramburu Alegría, 2018; Gray et al., 2016; Ryan, 2017). Gender diversity affects all members of the family in unique, highly personal and diverse ways, not always readily apparent to others. Several authors focused on the same themes. Bull and D’Arrigo-Patrick (2018) discussed meaning making in relation to individual, societal and relational perspectives and distinguished small-t transition (ongoing transitional issues) and large-t transitions (definitive changes such as name change). Similarly, Connolly (2005) viewed youth gender diversity through familial and societal constraints lenses. Individual family members variably understood gender transition as a medical condition, a natural nuance of gender identity or a lifestyle choice, although individual meaning making was generally a complex and highly individualized endeavor (Hill & Menvielle, 2009; Norwood, 2012, 2013b). Moreover, Schimmel-Bristow et al. (2018) highlighted deficits of appropriate language and knowledge to describe initial feelings of gender confusion for both youth and caregivers. Several authors sought to describe and understand caregiver responses within the immediate context of the family. Ehrensaft (2011) categorized parents as ‘transformers, transphobic or transporting’: ‘transformers’ provide attuned emotional support for young people to live in their chosen gender and can usually overcome any potential internalized transphobia. ‘Transphobic’ parents, by contrast, are described as insecure in their own gender authenticity, struggle to provide support to their child and are rejecting. ‘Transporting’ parents are described as insidious and incongruent in presentation, meaning that their initial and subsequent reactions are not always predictable. Rahilly (2015) instead postulated ‘gender-hedging’ (attempting to curb gender diversity), ‘playing along’ with the child’s gender expression (when confronted by others) and ‘gender literacy’, or parents talking back to the gender binary. Unhelpful historical assumptions in relation to attributing blame to caregivers or the family system were challenged by the findings of Hill and Menvielle (2009) who found no evidence of family discord, child or parent issues in all 42 parents interviewed; however, they note that over half of the children in the study were adopted. Furthermore, Ehrensaft (2011) strongly contests orthodox and psychoanalytic interpretations of the cause of childhood gender diversity, and instead clearly situates gender diversity and creativity within a normal developmental paradigm.

The conceptual frameworks and ‘lenses’ of grief, loss and ambiguous loss related to youth gender diversity within a family context were utilized by several authors (Aramburu Alegría, 2018; Catalpa & McGuire, 2018; Coolhart et al., 2018; Emerson & Rosenfeld, 1996; Gregor et al., 2015; Norwood, 2013a). In their multi-centre ethnographic study of 90 transgender youth, Catalpa and McGuire (2018) adopted a systemic understanding using the concept of ‘family boundary ambiguity’, referring to who is ‘in or out’ of the family. Boss (1999, p. 4) defined ambiguous loss as “not knowing whether a loved person is absent or present, dead or alive” and described this as one of the most debilitating and difficult losses to resolve. Norwood (2013a) continues with the theme of grief and discusses how family members endure, avoid or overcome grief associated with transition and conceptualized the transitional process as encompassing consecutive stages of replacement, revision, evolution and removal.

Both Emerson and Rosenfeld (1996) and Gregor et al. (2015) instead postulated a 5-stage grief model, with denial and loss being experienced respectively, leading to acceptance. Field and Mattson (2016) attempted to differentiate the LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender) cohort grouping and found parenting a transgender child was more difficult and isolative compared with parenting a lesbian, gay or bisexual child. In contrast, Gonzalez et al. (2013) discussed the positive experiences of parenting an LGBT child, including personal growth, positive emotions, activism, social connection and closer relationships.

Definitive evidence was found by several authors in terms of the positive and negative effects of parental support, or lack thereof, on the mental health, resilience and quality of life of gender diverse youth (Aramburu Alegría, 2018; Katz-Wise et al., 2018; Ryan et al., 2010; Simons et al., 2013; Travers et al., 2012). Numerous authors highlighted the need for, or lack of, professional support and understanding of youth and families experiencing gender diversity (Dierckx & Platero, 2018; Gregor et al., 2015; Riggs & Due, 2015; Riley et al., 2011; Schimmel-Bristow et al., 2018; von Doussa et al., 2017). Indeed, Katz-Wise et al. (2016) went so far as to suggest that health professionals should address issues of family acceptance and rejection during routine clinical visits. Literature was generally excluded if not directly referring to youth experiences. However, adult transgender experiences in relation to the family system will share common characteristics to those of children and young people, which some authors have already demonstrated (Riley, Sitharthan, et al., 2013). Nonetheless, the literature review findings are limited by the relatively small numbers of research participants and ungeneralisable sampling techniques. This is however understandable within the context of studying a minority and stigmatized population, and studies predominantly using a qualitative methodological approach. Fathers and male caregivers were under-represented, and caregiving of gender diverse youth was commonly found to be a solo endeavor. Some of the included literature subjugated transgender youth participants with lesbian, gay and bisexual youth, which although similar in many respects, are a unique and distinct research cohort. Only three studies could be found that included sibling experiences under the age of 18 years (Barron & Capous-Desyllas, 2017; Katz-Wise et al., 2018; Wheeler et al., 2019) and no studies could be found that primarily adopted a non-linear or circular line of enquiry (asking someone in the family how someone else might be feeling) involving caregivers, youth and siblings. Furthermore, although frequently mentioned in the research literature, no studies could be found describing how family functioning or individual family member viewpoints are currently explored in routine or specialist clinical care.

The importance and merit of understanding youth gender diversity within a family or systemic context is supported by the collective research findings. Frequent and compelling themes of meaning making for individual family members, adjustment, acceptance, professional understanding and improving youth mental health and quality of life, were found in the literature. Nevertheless, several authors highlighted a dearth of current research using a systemic perspective and the need for future research to incorporate findings into routine clinical care and to better understand and improve outcomes for young people and their families. The research findings consistently highlighted either a need for, or a lack of, professional knowledge, coupled with unsatisfactory healthcare experiences for young people experiencing gender diversity and other family members. Furthermore, future research should strategically target siblings and male caregivers to address a clear gap in the research literature.

The following recommendations are made to contribute to an enhanced understanding of individual and collective family member experiences, to inform current clinical practice and improve management guidelines and outcomes for gender diverse young people:

explore existing specialist assessment protocols to determine whether a comprehensive family approach is utilized;

explore professional viewpoints in relation to the value of a systemic approach in assessment and treatment;

include and integrate all family member viewpoints using a circular line of enquiry (asking one family member how another family member might be thinking or feeling) to reveal potentially unknown family member opinions, with a view to addressing unhelpful or pejorative assumptions to promote family acceptance; (Brown, 1997; Cecchin, 1987; Selvini et al., 1980); and

use future research results to inform professionals, educators, therapeutic approaches and treatment guidelines.

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Questioning

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Questioning

Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender

Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Questioning

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- Aitken M., Steensma T. D., Blanchard R., VanderLaan D. P., Wood H., Fuentes A., … Zucker K. J. (2015). Evidence for an Altered Sex Ratio in Clinic‐Referred Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(3), 756–763. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aramburu Alegría C. (2018). Supporting families of transgender children/youth: Parents speak on their experiences, identity, and views. International Journal of Transgenderism, 19(2), 132–143. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2018.1450798 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barron C., & Capous-Desyllas M. (2017). Transgressing the Gendered Norms in Childhood: Understanding Transgender Children and Their Families. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 13(5), 407–438. doi: 10.1080/1550428X.2016.1273155 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boss P. (1999). Insights: ambiguous loss: living with frozen grief. The Harvard Mental Health Letter, 16(5), 4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. (1997). Circular Questioning: An Introductory Guide. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 18(2), 109–114. doi: 10.1002/j.1467-8438.1997.tb00276.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bull B., & D’Arrigo-Patrick J. (2018). Parent experiences of a child’s social transition: Moving beyond the loss narrative. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 30(3), 170–190. doi: 10.1080/08952833.2018.1448965 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butler G., De Graaf N., Wren B., & Carmichael P. (2018). Assessment and support of children and adolescents with gender dysphoria. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 103(7), 631–636. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2018-314992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D., & Springer K. W. (2010). Advances in families and health research in the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 743–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00728.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Catalpa J. M., & McGuire J. K. (2018). Family Boundary Ambiguity Among Transgender Youth. Family Relations, 67(1), 88–103. doi: 10.1111/fare.12304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchin G. (1987). Hypothesizing, circularity, and neutrality revisited: An invitation to curiosity. Family Process, 26(4), 405–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1987.00405.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D., Hidalgo M. A., & Garofalo R. (2017). Parental perceptions of emotional and behavioral difficulties among prepubertal gender-nonconforming children. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 5(4), 342–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark T. C., Lucassen M. F. G., Bullen P., Denny S. J., Fleming T. M., Robinson E. M., & Rossen F. V. (2014). The Health and Well-Being of Transgender High School Students: Results From the New Zealand Adolescent Health Survey (Youth'12). Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(1), 93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly C. M. (2005). A process of change: The intersection of the GLBT individual and their family of origin. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 1(1), 5–20. doi: 10.1300/J461v01n01_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coolhart D., Ritenour K., & Grodzinski A. (2018). Experiences of Ambiguous Loss for Parents of Transgender Male Youth: A Phenomenological Exploration. Contemporary Family Therapy, 40(1), 28–41. doi: 10.1007/s10591-017-9426-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch M. B. (2016). Making it count: Improving estimates of the size of transgender and gender nonconforming populations. LGBT Health, 3(3), 181–185. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierckx M., & Platero R. L. (2018). The meaning of trans* in a family context. Critical Social Policy, 38(1), 79–98. doi: 10.1177/0261018317731953 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft D. (2011). Boys will be girls, girls will be boys: Children affect parents as parents affect children in gender nonconformity. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 28(4), 528–548. doi: 10.1037/a0023828 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson S., & Rosenfeld C. (1996). Stages of adjustment in family members of transgender individuals. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 7(3), 1–12. doi: 10.1300/J085V07N03_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Field T. L., & Mattson G. (2016). Parenting Transgender Children in PFLAG. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 12(5), 413–429. doi: 10.1080/1550428X.2015.1099492 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gartner R. E., & Sterzing P. R. (2018). Social Ecological Correlates of Family-Level Interpersonal and Environmental Microaggressions Toward Sexual and Gender Minority Adolescents. Journal of Family Violence, 33(1), 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10896-017-9937-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg S. (2017). The Gender revolution (special issue). National Geographic, 231, 1–154. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez K. A., Rostosky S. S., Odom R. D., & Riggle E. D. (2013). The positive aspects of being the parent of an LGBTQ child. Family Process, 52(2), 325–337. doi: 10.1111/famp.12009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray S. A. O., Sweeney K. K., Randazzo R., & Levitt H. M. (2016). Am I Doing the Right Thing?': Pathways to Parenting a Gender Variant Child. Family Process, 55(1), 123–138. doi: 10.1111/famp.12128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor C., Hingley-Jones H., & Davidson S. (2015). Understanding the experience of parents of pre-pubescent children with gender identity issues. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 32(3), 237–246. doi: 10.1007/s10560-014-0359-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman A. H., D'Augelli A. R., Howell T. J., & Hubbard S. (2005). Parents' reactions to transgender youths' gender nonconforming expression and identity. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 18(1), 3–16. doi: 10.1300/J041v18n01_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo M. A., & Chen D. (2019). Experiences of Gender Minority Stress in Cisgender Parents of Transgender/Gender-Expansive Prepubertal Children: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Family Issues, 40(7), 865–886. doi: 10.1177/0192513X19829502 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill D. B., & Menvielle E. (2009). You have to give them a place where they feel protected and safe and loved”: The views of parents who have gender-variant children and adolescents. Journal of LGBT Youth, 6(2-3), 243–271. doi: 10.1080/19361650903013527 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise S. L., Budge S. L., Fugate E., Flanagan K., Touloumtzis C., Rood B., … Leibowitz S. (2017). Transactional pathways of transgender identity development in transgender and gender-nonconforming youth and caregiver perspectives from the Trans Youth Family Study. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(3), 243–263. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2017.1304312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise S. L., Ehrensaft D., Vetters R., Forcier M., & Austin S. B. (2018). Family Functioning and Mental Health of Transgender and Gender-Nonconforming Youth in the Trans Teen and Family Narratives Project. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(4-5), 582–590. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2017.1415291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise S. L., Rosario M., & Tsappis M. (2016). Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth and Family Acceptance. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 63(6), 1011–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kübler-Ross E. (1973). On Death and Dying. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kuvalanka K. A., Weiner J. L., & Mahan D. (2014). Child, family, and community transformations: Findings from interviews with mothers of transgender girls. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 10(4), 354–379. doi: 10.1080/1550428X.2013.834529 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levitan N., Barkmann C., Richter-Appelt H., Schulte-Markwort M., & Becker-Hebly I. (2019). Risk factors for psychological functioning in german adolescents with gender dysphoria: Poor peer relations and general family functioning. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby B. D., Miller V., Regan K., Gruschow S., Hawkins L., & Dowshen N. (2019). Communication of Acceptance And Support In Families Who Have Gender-Variant Youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(2), S101–S102. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.10.216 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell E. A., Birkett M., & Mustanski B. (2016). Families Matter: Social Support and Mental Health Trajectories Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(6), 674–680. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.07.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadow T. (2011). Deep down where the music plays': How parents account for childhood gender variance. Sexualities, 14(6), 725–747. doi: 10.1177/1363460711420463 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehus C. J., Watson R. J., Eisenberg M. E., Corliss H. L., & Porta C. M. (2017). Living as an LGBTQ adolescent and a parent's child: Overlapping or separate experiences. Journal of Family Nursing, 23(2), 175–200. doi: 10.1177/1074840717696924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norwood K. (2012). Transitioning meanings? Family members' communicative struggles surrounding transgender identity. Journal of Family Communication, 12(1), 75–92. doi: 10.1080/15267431.2010.509283 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norwood K. (2013). Grieving gender: Trans-identities, transition, and ambiguous loss. Communication Monographs, 80(1), 24–45. doi: 10.1080/03637751.2012.739705 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norwood K. (2013). Meaning matters: Framing trans identity in the context of family relationships. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 9(2), 152–178. doi: 10.1080/1550428X.2013.765262 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olson K. R., Durwood L., DeMeules M., & McLaughlin K. A. (2016). Mental Health of Transgender Children Who Are Supported in Their Identities. Pediatrics, 137(3), e20153223. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker C. M., Hirsch J. S., Philbin M. M., & Parker R. G. (2018). The Urgent Need for Research and Interventions to Address Family-Based Stigma and Discrimination Against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 63(4), 383–393. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potoczniak D., Crosbie-Burnett M., & Saltzburg N. (2009). Experiences regarding coming out to parents among African American, Hispanic, and White gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and questioning adolescents. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 21(2-3), 189–205. doi: 10.1080/10538720902772063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahilly E. P. (2015). The gender binary meets the gender-variant child: Parents' negotiations with childhood gender variance. Gender & Society, 29(3), 338–361. doi: 10.1177/0891243214563069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly M. M. D., Desousa V. D. O., Garza-Flores A. M. D., & Perrin E. C. M. D. (2019). Young Children With Gender Nonconforming Behaviors and Preferences. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 40(1), 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick M. D., Bearman P. S., Blum R. W., Bauman K. E., Harris K. M., Jones J., … Shew M. (1997). Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA, 278(10), 823–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs D. W., & Due C. (2015). Support Experiences and Attitudes of Australian Parents of Gender Variant Children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(7), 1999–2007. doi: 10.1007/s10826-014-9999-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riley E. A., Clemson L., Sitharthan G., & Diamond M. (2013). Surviving a gender-variant childhood: The views of transgender adults on the needs of gender-variant children and their parents. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 39(3), 241–263. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2011.628439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley E. A., Sitharthan G., Clemson L., & Diamond M. (2011). The needs of gender-variant children and their parents: A parent survey. International Journal of Sexual Health, 23(3), 181–195. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2011.593932 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riley E. A., Sitharthan G., Clemson L., & Diamond M. (2013). Recognising the needs of gender-variant children and their parents. Sex Education, 13(6), 644–659. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2013.796287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe S. (2017). Family support would have been like amazing”: LGBTQ youth experiences with parental and family support. The Family Journal, 25(1), 55–62. doi: 10.1177/1066480716679651 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C., Huebner D., Diaz R. M., & Sanchez J. (2009). Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics, 123(1), 346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C., Russell S. T., Huebner D., Diaz R., & Sanchez J. (2010). Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23(4), 205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2010.00246.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan K. N. (2017). Examining the family transition: How parents of gender-diverse youth develop trans-affirming attitudes. Sociological Studies of Children and Youth, 23, 67–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sansfaçon A. P., Hebert W., Lee E. O. J., Faddoul M., Tourki D., & Bellot C. (2018). Digging beneath the surface: Results from stage one of a qualitative analysis of factors influencing the well-being of trans youth in Quebec. International Journal of Transgenderism, 19(2), 184–202. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2018.1446066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sansfaçon A. P., Robichaud M.-J., & Dumais-Michaud A.-A. (2015). The experience of parents who support their children's gender variance. Journal of LGBT Youth, 12(1), 39–63. doi: 10.1080/19361653.2014.935555 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmel-Bristow A., Haley S. G., Crouch J. M., Evans Y. N., Ahrens K. R., McCarty C. A., & Inwards-Breland D. J. (2018). Youth and caregiver experiences of gender identity transition: A qualitative study. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5(2), 273–281. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000269 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Selvini M. P., Boscolo L., Cecchin G., & Prata G. (1980). Hypothesizing—circularity—neutrality: Three guidelines for the conductor of the session. Family Process, 19(1), 3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1980.00003.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons L., Olson J., Belzer M., Clark L., & Schrager S. (2012). The relationship between parental support and depression and suicidality in transgender adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(2), S29. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.10.078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons L., Schrager S. M., Clark L. F., Belzer M., & Olson J. (2013). Parental support and mental health among transgender adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(6), 791–793. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spack N. P., Edwards-Leeper L., Feldman H. A., Leibowitz S., Mandel F., Diamond D. A., & Vance S. R. (2012). Children and adolescents with gender identity disorder referred to a pediatric medical center. Pediatrics, 129(3), 418. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telfer M., Tollit M., & Feldman D. (2015). Transformation of health-care and legal systems for the transgender population: The need for change in Australia. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 51(11), 1051–1053. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telzer E. H., Fuligni A. J., Lieberman M. D., & Galván A. (2013). Meaningful family relationships: Neurocognitive buffers of adolescent risk taking. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 25(3), 374–387. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers R., Bauer G., Pyne J., Bradley K., Gale L., & Papadimitriou M. (2012). Impacts of strong parental support for trans youth: A report prepared for Children's Aid Society of Toronto and Delisle youth services. Trans PULSE Retrieved from http://transpulseproject.ca/research/impacts-of-strong-parental-support-for-trans-youth/

- Turban J. L., & Ehrensaft D. (2018). Research Review: Gender identity in youth: Treatment paradigms and controversies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(12), 1228–1243. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D., & Karas Montez J. (2010). Social relationships and health: A flashpoint for health policy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(1_suppl), S54–S66. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D., Thomeer M. B., & Williams K. (2013). Family status and mental health: Recent advances and future directions In Aneshensel C. S., Phelan J. C., & Bierman A. (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental health (pp. 405–431). Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- von Doussa H., Power J., & Riggs D. W. (2017). Family matters: Transgender and gender diverse peoples’ experience with family when they transition. Journal of Family Studies, 1–24. doi: 10.1080/13229400.2017.1375965 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh F. (2002). A Family Resilience Framework: Innovative Practice Applications. Family Relations, 51(2), 130–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2002.00130.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler N. L., Langton T., Lidster E., & Dallos R. (2019). Understanding more about how young people make sense of their siblings changing gender identity: How this might affect their relationships with their gender-diverse siblings and their experiences. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24(2), 258–276. doi: 10.1177/1359104519830155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood H., Sasaki S., Bradley S. J., Singh D., Fantus S., Owen-Anderson A., … Zucker K. J. (2013). Patterns of referral to a gender identity service for children and adolescents (1976-2011): Age, sex ratio, and sexual orientation. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 39(1), 1–6. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2012.675022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wren B. (2002). I Can Accept My Child is Transsexual but if I Ever See Him in a Dress I'll Hit Him': Dilemmas in Parenting a Transgendered Adolescent. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 7(3), 377–397. doi: 10.1177/1359104502007003006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zamboni B. D. (2006). Therapeutic considerations in working with the family, friends, and partners of transgendered individuals. The Family Journal, 14(2), 174–179. doi: 10.1177/1066480705285251 [DOI] [Google Scholar]