Abstract

When photoactive molecules interact strongly with confined light modes in optical cavities, new hybrid light–matter states form. They are known as polaritons and correspond to coherent superpositions of excitations of the molecules and of the cavity photon. The polariton energies and thus potential energy surfaces are changed with respect to the bare molecules, such that polariton formation is considered a promising paradigm for controlling photochemical reactions. To effectively manipulate photochemistry with confined light, the molecules need to remain in the polaritonic state long enough for the reaction on the modified potential energy surface to take place. To understand what determines this lifetime, we have performed atomistic molecular dynamics simulations of room-temperature ensembles of rhodamine chromophores strongly coupled to a single confined light mode with a 15 fs lifetime. We investigated three popular experimental scenarios and followed the relaxation after optically pumping (i) the lower polariton, (ii) the upper polariton, or (iii) uncoupled molecular states. The results of the simulations suggest that the lifetimes of the optically accessible lower and upper polaritons are limited by (i) ultrafast photoemission due to the low cavity lifetime and (ii) reversible population transfer into the “dark” state manifold. Dark states are superpositions of molecular excitations but with much smaller contributions from the cavity photon, decreasing their emission rates and hence increasing their lifetimes. We find that population transfer between polaritonic modes and dark states is determined by the overlap between the polaritonic and molecular absorption spectra. Importantly, excitation can also be transferred ”upward” from the lower polariton into the dark-state reservoir due to the broad absorption spectra of the chromophores, contrary to the common conception of these processes as a ”one-way” relaxation from the dark states down to the lower polariton. Our results thus suggest that polaritonic chemistry relying on modified dynamics taking place within the lower polariton manifold requires cavities with sufficiently long lifetimes and, at the same time, strong light–matter coupling strengths to prevent the back-transfer of excitation into the dark states.

In general, molecules cannot be treated in isolation but have to be understood as embedded in and coupled to the electromagnetic field surrounding them. This applies even when the field is in its vacuum state, and leads to properties such as the Lamb shift or spontaneous emission from excited states. In free space, these are typically small corrections and can be neglected in many cases (e.g., emission lifetimes are normally on the order of nanoseconds, much slower than the electronic and nuclear dynamics determining most photochemical reactions). The situation is different when molecules are placed inside optical or plasmonic cavities,1,2 because these photonic structures can modify the vacuum field to such an extent that photonic degrees of freedom also become important.3,4 These structures not only confine the light to smaller volumes, increasing the coupling strength, but also restrict the number of photonic modes available to interact with the molecules. The confinement furthermore enhances the light–matter interaction, which can become strong enough for the photonic and molecular degrees of freedom to hybridize into new light–matter states, known as polaritons.2,5

We summarize the main consequences of strong light–matter coupling from a molecular standpoint here, with more detailed descriptions available in the literature.6,7 Within the single-excitation subspace accessed under weak driving, strong coupling between N molecules and a single confined light mode leads to the formation of N + 1 coherent superpositions of excitations in each of the molecules and of the confined light mode:8,9

| 1 |

Here, |gi⟩ and |ei⟩ are the electronic ground and

excited states

of molecule i, while |1⟩ or |0⟩ indicates

if the confined light mode is excited or not. The βik and αk are expansion

coefficients ( ), and the index k labels

the N + 1 single-excitation eigenstates of the strongly

coupled molecule–cavity system. If the excitation energy of

the molecules (hνi) is similar to the frequency of the confined light mode (ℏωcav), the energy gap, or Rabi

splitting (ℏΩRabi), between

the lowest (k = 1, i.e., the lower polariton, LP)

and the highest (k = N + 1, i.e.,

the upper polariton, UP) hybrid light–matter states is proportional

to the square root of the number of molecules (N)

that are strongly interacting with the confined light mode of the

cavity

), and the index k labels

the N + 1 single-excitation eigenstates of the strongly

coupled molecule–cavity system. If the excitation energy of

the molecules (hνi) is similar to the frequency of the confined light mode (ℏωcav), the energy gap, or Rabi

splitting (ℏΩRabi), between

the lowest (k = 1, i.e., the lower polariton, LP)

and the highest (k = N + 1, i.e.,

the upper polariton, UP) hybrid light–matter states is proportional

to the square root of the number of molecules (N)

that are strongly interacting with the confined light mode of the

cavity

| 2 |

where μmolTDM is the transition dipole

moment of the molecular excitation, ϵ0 is the vacuum

permittivity, and Vcav is the effective

mode volume of the confined photon with energy ℏωcav. Note that we have assumed perfect alignment between

the molecular dipole moments and the cavity electric field ( ) here for simplicity.

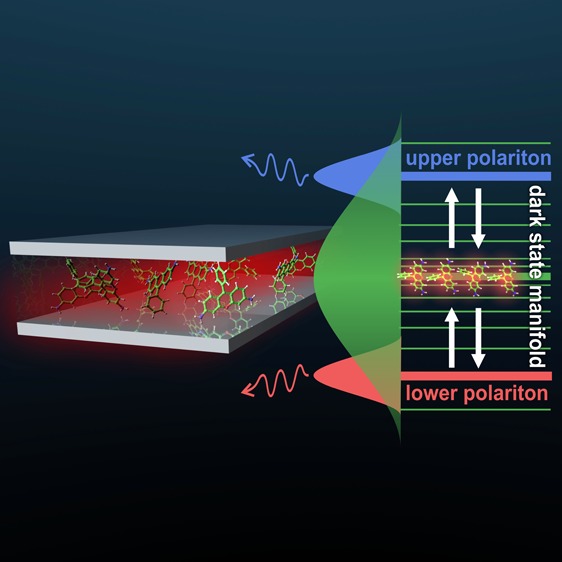

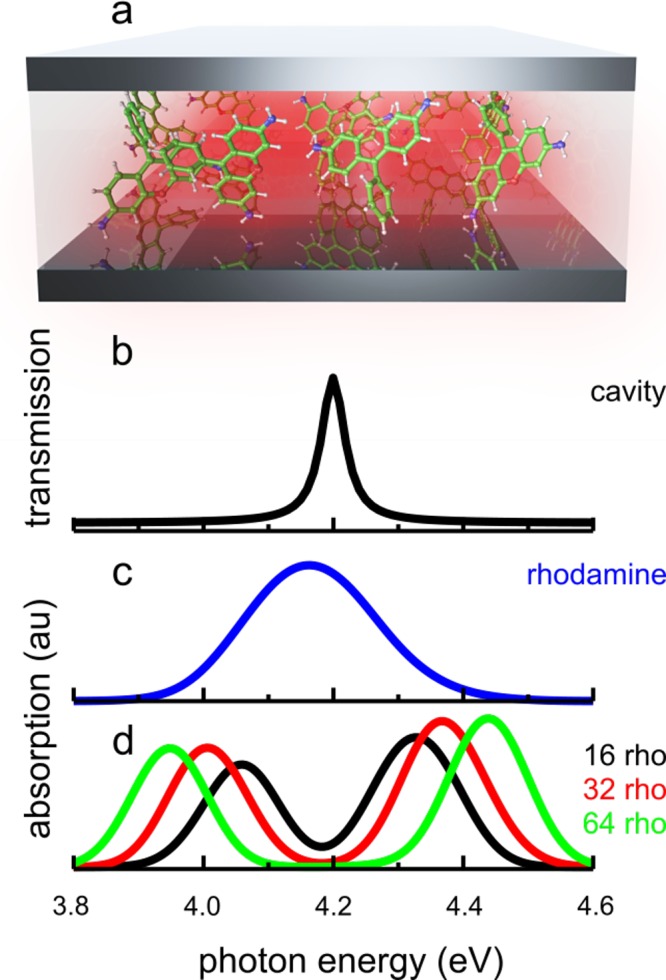

The lower and upper

polariton have the highest contribution of the cavity mode. Since

the cavity typically dominates the response under external driving,

the absorption spectrum of the cavity–molecule system then

contains two peaks corresponding to the lower and upper polaritons,

located below and above the absorption maxima of the molecules and

the cavity (Figure 1). Due to their smaller cavity contribution, the other N – 1 levels are typically far less visible and are thus referred

to as “dark” states.

) here for simplicity.

The lower and upper

polariton have the highest contribution of the cavity mode. Since

the cavity typically dominates the response under external driving,

the absorption spectrum of the cavity–molecule system then

contains two peaks corresponding to the lower and upper polaritons,

located below and above the absorption maxima of the molecules and

the cavity (Figure 1). Due to their smaller cavity contribution, the other N – 1 levels are typically far less visible and are thus referred

to as “dark” states.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic depiction of the cavity–molecule systems studied in this work. Note that although a typical Fabry-Pérot cavity is illustrated here, the cavities in our simulations more closely resemble a plasmonic nanocavity, in particular when there are only a few molecules. (b) Cavity transmission spectrum. (c) Absorption spectrum of the rhodamine model in water outside of the cavity. (d) Absorption spectrum of the cavity with 16 (black), 32 (red), and 64 (green) solvated rhodamine molecules in the cavity volume.

The hybridization of light and matter into polaritons not only delocalizes the excitation over many molecules (eq 1) but also changes the molecular potential energy surfaces, and thus provides a new way to control photochemistry10−19 and photophysics.20−23 To manipulate reactivity with confined light, however, the polariton lifetime should exceed the time it takes for the molecules to react on the modified potential energy surface. As polariton lifetimes are mostly determined by the cavity quality factor (Q-factor), one may thus expect that very high-finesse cavities would be required, in particular for slower photochemical reactions. However, results of recent time-resolved pump–probe experiments on various strongly coupled systems suggest that the lower polariton inherits the excited-state lifetime of the molecules, rather than that of the cavity.24−26

While this finding could have major implications for the feasibility of polaritonic catalysis,7,27−29 an alternative explanation for the slow emission from the lower polaritonic state in these experiments is that the strongly coupled system undergoes transitions into the hybrid “dark” states, which act as a reservoir that slowly replenishes the polariton modes.28,30−39 Because these dark states lack a strong contribution from the cavity photon (αk in eq 1), their decay is dominated by the excited-state lifetimes of the molecules, which are typically much longer. Results from time-dependent quantum dynamics simulations on simplified molecule–cavity systems, in which the nuclear degrees of freedom were modeled as one or many harmonic oscillators and treated to various levels of approximation, support this notion.39−44 Although the vibrational structure of the molecules was included, the harmonic approximation, which was necessary to solve the Schrödinger equation, restricts these simulations to nonreactive systems. To overcome this limitation and model the effects of strong light–matter coupling on the dynamics of even larger ensembles of realistic molecules, we recently proposed a multiscale molecular dynamics approach based on hybrid Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) simulations.6 Here, we apply that approach to model the relaxation dynamics of up to 1000 rhodamine molecules strongly coupled to a confined light mode with a lifetime of 15 fs.

Because the number of polaritonic states equals the number of molecules in the cavity plus one (eq 1) and the energy gaps between these states are very small, the dynamics have to be simulated in a dense manifold of coupled states.7,45 While Tully’s fewest switches surface hopping (FSSH) algorithm46 has been highly successful for modeling non-adiabatic dynamics in systems with few electronic states,47 the number of semiclassical simulations required to achieve convergence when there are hundreds to thousands of near-degenerate states precludes FSSH for modeling the dynamics of the large ensembles of strongly coupled molecules in this work. We therefore rely on Ehrenfest, or mean-field, dynamics instead48 and integrate the time-dependent polaritonic wave function, expanded in the basis of the time-independent polaritonic states (eq 1)

| 3 |

along the N classical molecular dynamics (MD) trajectories evolving on the mean-field potential energy surface. The force on atom a is then

| 4 |

and we use the unitary propagator in a local diabatic basis to integrate the coefficients, ck(t).49 The complete description of our Ehrenfest dynamics simulations is available as Supporting Information (SI).

We have simulated ensembles of up to 1000 rhodamine molecules including the solvent environment and a confined light mode with a resonance frequency of ωcav = 4.2 eV, tuned near the absorption maximum of the rhodamine molecules (Figure 1), which is 4.18 eV at the CIS/3-21G//Amber level of QM/MM theory (SI). The cavity photon lifetime is taken as 15 fs, corresponding to a decay rate of γcav = 66.7 ps–1 (line-width ℏγcav = 0.04 eV), in line with previous experiments.26 This lifetime depends on the accuracy of the nanofabrication process, the thickness of the mirrors, and the cavity material.1 In the simulations, the dissipation of the cavity photon is modeled ad hoc as a first-order decay process of polaritonic states with a contribution from the confined light mode6

| 5 |

where ρk(t) = |ck(t)|2 is the population of polaritonic state ψk at time t, αk the contribution of the photonic mode to that state (eq 1) and Δt the time step of the classical MD simulation (0.1 fs; see SI for further details). The cavity lifetime is illustrated by the finite line width of the cavity transmission peak in Figure 1b.

Two types of ensembles were investigated. In the first, all molecules started from the same initial coordinates, but with different nuclear velocities selected randomly from a Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution at a temperature of 300 K. In the second set of simulations, both initial coordinates and velocities were selected randomly from QM/MM trajectories of a single Rhodamine molecule in water. Assuming instantaneous and resonant photoexcitation, the simulations were started in either the upper or lower polaritonic states. While for the ensembles with the same initial coordinates, the lower and upper polaritons can be identified without ambiguity as the eigenstates with the lowest and highest eigenvalue of the cavity–molecule Hamiltonian, the identification is more complicated for the heterogeneous room temperature ensembles, where the excitation energies form a distribution due to structural heterogeneity (Figure 1c). Because in this situation there are multiple states with a significant contribution of the cavity photon, the initial state of the simulation was a superposition of all polaritonic states below (LP) or above (UP) the transmission maximum of the cavity, weighted by their photonic contributions (i.e., |αk|2 in eq 1).

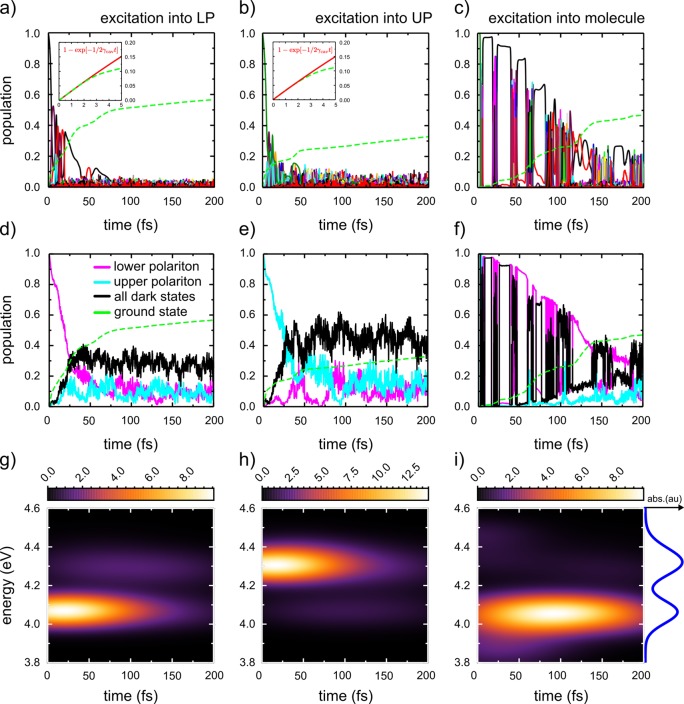

Regardless of the cavity mode volume (Vcav) or the number of molecules (N), the results of our molecular dynamics simulations, shown in Figures 2, 3, and S6–S8 (SI), suggest a relaxation process that involves the transient population of “dark” states, if these are available. After pumping the upper or lower polariton in ensembles of molecules with the same starting coordinates (i.e., same excitation energies), but different velocities, the relaxation initially occurs through direct photoemission, as evidenced by the rapid buildup of the ground-state population (dashed green line in Figure 2) and the concomitant decline of the initial polaritonic states. Because the upper and lower polaritons are approximately equal mixtures of the molecular excitations and the confined light mode at the start of the simulations, the initial rate of this radiative decay process is approximately the product of the cavity decay rate (γcav, eq 5) and the photonic component of the polariton (|αLP/UP|2 ≈ 0.5, eq 1). As shown in the insets of Figure 2a,b, the rise of the ground-state population in the first few femtoseconds indeed follows a simple exponential function with a decay constant of 0.5γcav. However, while the system relaxes, non-adiabatic coupling with the “dark” states triggers population transfer from both the upper and lower polaritons into these states. As the dark states have a much smaller contribution of the cavity photon, direct emission is reduced significantly and the rate at which the ground-state population builds up decreases. Nevertheless, because population transfer is reversible and also occurs from the dark states back into the bright upper and lower polaritons, radiative decay continues, albeit at a much lower rate (lower panels in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Top panels: populations of the polaritonic states

(|ck(t)|2, eq 3, all colors) in simulations

of 64 molecules in a nanocavity with single-photon field strength  atomic units (0.7 MV cm–1), corresponding to a

mode volume of 7275 nm3 (leading

to a Rabi splitting on resonance of 260 meV, eq 2, after excitation into the lower polariton

(LP, a,d); into the upper polariton (UP, b,e); and into a molecular

excited state that is 156 meV above the UP (c,f). The population of

the ground state with no photon present (i.e., |g1g2···gi···gN⟩|0⟩) is plotted

as green dashed lines. The insets in a and b show the ground-state

population for the first 5 fs and an exponential fit (red line). Middle

panels: populations of the bright lower (magenta) and upper (cyan)

polaritons and the sum of the dark states (black). States are considered

bright (dark) if the contribution of the cavity photon (|αk|2) is above (below) 0.05. Bottom

panels: time-resolved emission spectra (sunset color scheme) after

photoexcitation into LP (g), into UP (h), and into a state above the

UP (i). The photoabsorption spectrum of this cavity–molecule

system is shown at the right of panel i.

atomic units (0.7 MV cm–1), corresponding to a

mode volume of 7275 nm3 (leading

to a Rabi splitting on resonance of 260 meV, eq 2, after excitation into the lower polariton

(LP, a,d); into the upper polariton (UP, b,e); and into a molecular

excited state that is 156 meV above the UP (c,f). The population of

the ground state with no photon present (i.e., |g1g2···gi···gN⟩|0⟩) is plotted

as green dashed lines. The insets in a and b show the ground-state

population for the first 5 fs and an exponential fit (red line). Middle

panels: populations of the bright lower (magenta) and upper (cyan)

polaritons and the sum of the dark states (black). States are considered

bright (dark) if the contribution of the cavity photon (|αk|2) is above (below) 0.05. Bottom

panels: time-resolved emission spectra (sunset color scheme) after

photoexcitation into LP (g), into UP (h), and into a state above the

UP (i). The photoabsorption spectrum of this cavity–molecule

system is shown at the right of panel i.

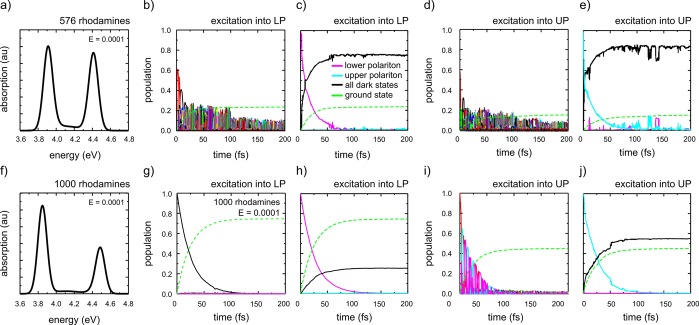

Figure 3.

Absorption spectra (first column) and state populations after excitation into the lower polariton (second and third columns) and upper polariton (fourth and fifth columns). The dashed green line is the ground-state population. Two systems are shown: 576 (top panels) and 1000 molecules (bottom panels) in a nanocavity with single-photon field strength of Ecav = 0.0001 atomic units (0.5 MV cm–1), corresponding to a mode volume of 14,259 nm3. In panels b, d, g, and i, the populations of all adiabatic polaritonic states are plotted (i.e., |ck(t)|2, eq 3, all colors). In panels c, e, h, and j, the populations of bright lower and upper polaritons are shown in magenta and cyan, respectively, while the total dark-state population is plotted as a single black line. States are considered bright (dark) if the contribution of the cavity photon (|αk|2) is above (below) 0.05.

The observation that the population transfers from the upper polariton into the “dark” states and eventually into the lower polariton is in good qualitative agreement with experiments that probed prolonged photoluminescence from strongly coupled cavity–molecule systems after pumping the upper polariton,24,26,33,35,50 while more recently, population transfer from the lower polariton into the “dark” state manifold has also been suggested on the basis of anti-Stokes emission measured after pumping the lower polariton.51 Thus, the results of our simulations do not support the conjecture that the polaritons inherit the excited-state lifetime of the molecules,24−26 but rather suggest that nonradiative scattering into dark states, which are sometimes referred to as the “exciton reservoir”,31,32,36 controls the polariton relaxation, in agreement also with previous calculations on simpler molecular models.39,42,45

To mimic experiments in which a molecular electronic state lying above the upper polariton is pumped,24,26,52 we added a structure from the equilibration trajectory that has a geometry in which the S0 → S1 excitation energy (4.48 eV) is higher than the upper polariton (4.32 eV) to the cavity. Because of the larger excitation energy, the highest electronic state in these cavities is localized on this molecule. After excitation into that state, the initial decay process is slower than when the UP or LP is pumped directly (Figure 2c,f). We attribute this difference to the much lower photonic contribution to this state in the cavity. However, due to non-adiabatic transitions, both upper and lower polaritonic states as well as the other dark states become transiently populated. Because only states with a significant photonic contribution can emit efficiently, as evidenced by the photoluminescence spectra in Figure 2i, the transient population of upper and lower polariton increases the decay rate. The results of these simulations confirm that excitation of uncoupled states leads to the transient population of the optically accessible polariton states, in particular, the lower polariton (Figure 2f). However, as with excitation directly into the UP or LP,33,51 the total lifetime of the polaritonic photoluminescence is controlled by the competition between, on one hand, direct photoemission determined by the cavity decay rate and, on the other hand, transient population of the dark states, and thus exceeds the cavity lifetime (bottom panels in Figure 2).

To investigate the effect of structural disorder among the chromophores,

we randomly selected initial coordinates and velocities from equilibrium

QM/MM trajectories of uncoupled rhodamine. In Figure 3, we plot the time evolution of the populations

with 576 and 1000 rhodamine molecules in the cavity. In line with

the results obtained when the molecules have the same starting coordinates,

there is competition between direct photoemission (dashed green line)

and transitions into the dark states, when these are available (Figure 3). In the case of

576 and 1000 molecules, the single-molecule coupling is held constant,

so that the Rabi splitting increases by a factor of  , with the effect that for the 1000 molecule

ensemble, the polariton lies outside the absorption band of the uncoupled

molecules. The simulations show that decay through photoemission is

most efficient in this case. Additionally, this direct radiative decay

channel is more efficient for the LP than the UP, as illustrated by

the faster buildup of ground-state population when the LP state is

pumped. The reason for this difference is that from the UP, “dark”

states are more accessible, and hence these nonradiative “dark”

states become populated to a much larger extent (compare Figure 3h and j).

, with the effect that for the 1000 molecule

ensemble, the polariton lies outside the absorption band of the uncoupled

molecules. The simulations show that decay through photoemission is

most efficient in this case. Additionally, this direct radiative decay

channel is more efficient for the LP than the UP, as illustrated by

the faster buildup of ground-state population when the LP state is

pumped. The reason for this difference is that from the UP, “dark”

states are more accessible, and hence these nonradiative “dark”

states become populated to a much larger extent (compare Figure 3h and j).

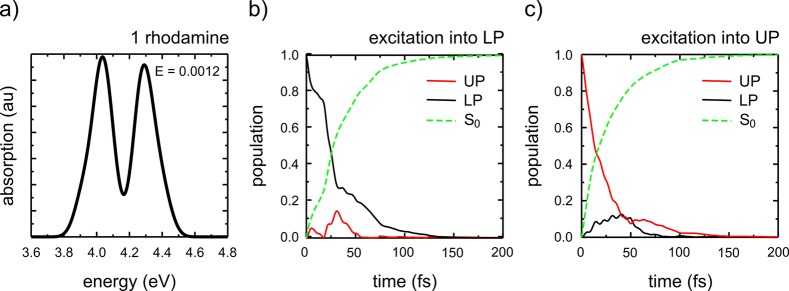

When there is only a single molecule inside the cavity (Figure 4), which has been realized experimentally, for example, by Baumberg and co-workers,53 there is a non-adiabatic population transfer between the upper and lower polaritons in addition to direct photoemission. However, because the cavity is tuned near the excitation maximum of the molecule, both states have strong photonic character (|αk|2 ≈ 0.5) and the system rapidly decays to the ground state (green dashed line) from both polaritonic states, with a rate controlled by the cavity lifetime γcav. The transient population of the lower polariton after pumping the upper polariton (Figure 4c) was also observed in recent tensor network simulations of a single strongly coupled molecule by del Pino and co-workers,39 as were the oscillatory features due to the activation of coherent vibrations of Franck–Condon active modes upon photoexcitation.

Figure 4.

Absorption spectrum (left panel) and state populations after excitation into the lower polariton (middle panel) and upper polariton (right panel) of a single molecule strongly coupled to a nanocavity with a mode volume of 99 nm3, corresponding to a single photon field strength of Ecav = 0.0012 atomic units (6.2 MV cm–1). The dashed green line is the ground-state population.

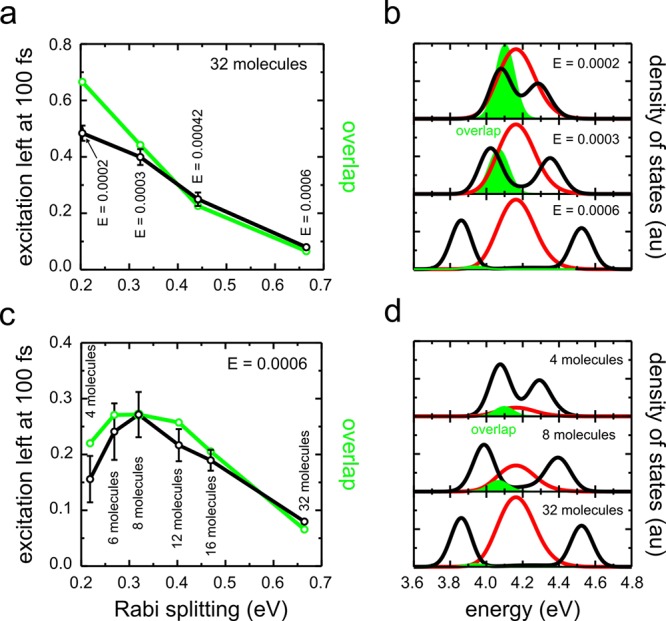

Comparing the relaxation process between simulations with the same number of molecules but different cavity mode volumes (Figures S6–S8) or, equivalently, different single-photon field strengths Ecav, we observe that decay through direct photoemission increases if the cavity mode volume decreases. In Figure 5, we plot the total population that remains excited at 100 fs after photoexcitation into the LP as a function of the Rabi splitting. Because non-adiabatic population transfer into the dark states competes with direct photoemission from the lower polariton, the overall decay rate is determined by the accessibility of the dark states. As the non-adiabatic coupling between states is inversely proportional to the energy gap, the most accessible states are the ones at or near resonance with the lower polariton.

Figure 5.

Total population

remaining in the excited-state manifold,  , containing the LP, N –

1 dark states, and UP, at 100 fs after photoexcitation into the lower

polariton as a function of Rabi splitting (black lines in a and c).

In panel a, there are 32 Rhodamine molecules in cavities with various

single-photon field strengths (E, in atomic units).

In c, the number of molecules in the cavity is varied from 4 to 32,

while keeping the cavity field strength constant at 0.0006 au (3.1

MV cm–1, 396 nm3 mode volume). Error

bars are estimated from five independent simulations. The green peaks

in panels b and d show the overlap between the LP (left dark peak)

and the dark states (red peak). The trend of this overlap is shown

as the green line in panels a and c.

, containing the LP, N –

1 dark states, and UP, at 100 fs after photoexcitation into the lower

polariton as a function of Rabi splitting (black lines in a and c).

In panel a, there are 32 Rhodamine molecules in cavities with various

single-photon field strengths (E, in atomic units).

In c, the number of molecules in the cavity is varied from 4 to 32,

while keeping the cavity field strength constant at 0.0006 au (3.1

MV cm–1, 396 nm3 mode volume). Error

bars are estimated from five independent simulations. The green peaks

in panels b and d show the overlap between the LP (left dark peak)

and the dark states (red peak). The trend of this overlap is shown

as the green line in panels a and c.

The distribution of the dark states, i.e., their density of states (DOS), is very similar to that of the uncoupled molecules (red curve in Figure 5b) and, hence, closely matches the absorption spectrum of the bare molecule (Figure 1c).52 Indeed, the overlap, evaluated as the integral between the DOS of the lower polariton (left black peak in Figure 5b) and the DOS of the bare molecules (red; see SI for details of this calculation), shows the same trend as the excited-state survival rate, estimated as the excitation remaining in the system at 100 fs after photoexcitation (Figure 5a). This observation suggests that the rate of population transfer into the dark states is controlled by the DOS of the dark states at the polariton energy level, as suggested by Coles et al.52 Thus, our results suggest that the efficiency of remaining in the lower polaritonic state, which is essential for manipulating photochemistry,7,12,29,54 can be estimated directly from the overlap between the polaritonic and molecular absorption spectra. In other words, the simple picture of photochemistry occurring on polaritonic potential energy surfaces under strong coupling only applies (in the many-molecule case) if the Rabi splitting is large enough for the polaritons to be energetically well-separated from the bare-molecule states, extending similar observations for the absorption spectra in extremely simplified model molecules.3

To further verify the validity of this overlap argument, we have also varied the number of molecules, while keeping the cavity mode volume, or quantized field strength, constant. In Figure 5c, we plot the total excited population remaining at 100 fs after pumping the lower polariton, as a function of Rabi splitting. Again, the trend follows the overlap between the DOS of the lower polariton on one hand and the DOS of the molecules on the other hand (Figure 5d). Since the energy level of the LP is determined by the square root of the number of rhodamine molecules (eq 2), while the DOS of the dark states scales linearly with the number of molecules, the overlap has a maximum when there are eight molecules in our cavity. Indeed, with eight molecules inside the cavity, the population of dark states at 100 fs is the highest, confirming that the accessibility of these states is determined by their overlap with the optically active lower polariton.

Because vibronic progression cannot be modeled in classical MD simulations, the molecular spectra appear as a single heterogeneously broadened peak without vibrational structure (Figure 1c). Because vibronic progression extends the spectrum toward higher energies on the blue side of the absorption maximum, we could thus underestimate the overlap between the upper polariton and the dark states. In contrast, because the lower polariton is situated below the (vertical) absorption maximum, the effects of vibronic progression on the overlap should be much smaller, possibly even negligible.

The observation that the overlap between the bright and dark polaritonic states governs the lifetime of the molecule–cavity system is supported by experiments that probed the photoluminescence in strongly coupled systems after pumping the lower polariton. For molecules with very narrow absorption bands, such as J-aggregates, there is minimal overlap between the dark states and the lower polariton already at moderate Rabi splittings. Without involvement of dark states, the relaxation process after pumping the lower polariton is thus dominated by ultrafast radiative emission. In low-finesse cavities, this decay is difficult to detect, in both stationary and transient measurements, in line with experimental observations.24−26 In contrast, for molecules with a broad absorption band, there is significant overlap between the bright and dark polaritonic states even for large Rabi splittings. Because in addition to ultrafast direct photoemission from the LP, there is also population transfer into the long-lived dark state manifold due to this overlap, the apparent lifetime of the LP emission is prolonged and hence detectable.26,51,52 The results of our simulations furthermore suggest occupation of polaritonic states above the LP due to a redistribution of the thermal energy. This thermal population of polaritonic states can account not only for the observation of anti-Stokes emission after pumping the LP,51 but also for the temperature-dependent emission from the UP.52 We believe that our findings could be relevant for designing molecule–cavity systems for polaritonic chemistry, in which access to dark states may compromise the control of photoreactivity due to modifications of the lower polaritonic potential energy surface.7,12−14,27,28,54

In summary, we have performed MD simulations of ensembles of rhodamine molecules strongly coupled to a single confined light mode. The results of the simulations suggest that relaxation of the optically active polaritons involves both direct photoemission with a rate controlled by the cavity lifetime as well as transitions into the “dark” state manifold, or “exciton reservoir”.31,32 Because the transient population of the dark states, which lack a strong photonic contribution, delays the photoemission, the molecule–cavity system has a much longer lifetime than the cavity alone, in line with previous experiments24−26,33 and theoretical work.37,39,42,45 Furthermore, our simulations also suggest that the efficiency of transitions into the dark states is determined by the overlap between the densities of the dark and bright polaritonic states, which can be inferred directly from the absorption spectra. Because both radiative decay and radiationless transitions into the dark-state manifold compete with the dynamics on the polaritonic energy landscape,54 controlling photochemistry with cavities requires both a long-lived cavity mode and a large Rabi splitting. In followup work, we will further address these issues for photoreactive molecules in a cavity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Academy of Finland (Grants 289947 to JJT, 290677 to GG, and 285481 to DM) as well as the European Research Council (ERC-2016-StG-714870 to JF) and the Spanish Ministry for Science, Innovation, and Universities – AEI (RTI2018-099737-B-I00 to JF). We thank the Center for Scientific Computing (CSC-IT Center for Science) for computational resources and Fredrik Robertsén in particular for his help with running our simulations on GPUs. We also acknowledge PRACE for awarding us access to resource Curie based in France at GENCI.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b02192.

Complete description of the Ehrenfest molecular dynamics simulation protocol, calculation of absorption and emission spectra, calculation of density of states (DOS), and plots of the populations versus time in all simulations (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Vahala K. J. Optical Microcavities. Nature 2003, 424, 839–846. 10.1038/nature01939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Törmä P.; Barnes W. L. Strong coupling between surface plasmon polaritons and emitters: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2015, 78, 013901. 10.1088/0034-4885/78/1/013901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galego J.; Garcia-Vidal F. J.; Feist J. Cavity-Induced Modifications of Molecular Structure in the Strong-Coupling Regime. Phys. Rev. X 2015, 5, 041022. 10.1103/PhysRevX.5.041022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flick J.; Ruggenthaler M.; Appel H.; Rubio A. Atoms and Molecules in Cavities: From Weak to Strong Coupling in QED Chemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017, 114, 3026–3034. 10.1073/pnas.1615509114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovzhenko D. S.; Ryabchuk S. V.; Rakovich Y. P.; Nabiev I. R. light–matter interaction in the strong coupling regime: configurations, conditions, applications. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 3589–3605. 10.1039/C7NR06917K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk H.-L.; Feist J.; Toppari J. J.; Groenhof G. Multiscale Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Polaritonic Chemistry. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2017, 13, 4324–4335. 10.1021/acs.jctc.7b00388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feist J.; Galego J.; Garcia-Vidal F. J. Polaritonic chemistry with organic molecules. ACS Photonics 2018, 5, 205–216. 10.1021/acsphotonics.7b00680. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaynes E. T.; Cummings F. W. Comparison of quantum and semiclassical radiation theories with to the beam maser. Proc. IEEE 1963, 51, 89–109. 10.1109/PROC.1963.1664. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tavis M.; Cummings F. W. Approximate solutions for an N-molecule radiation-field Hamiltonian. Phys. Rev. 1969, 188, 692–695. 10.1103/PhysRev.188.692. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison J. A.; Schwartz T.; Genet C.; Devaux E.; Ebbesen T. W. Modifying Chemical Landscapes by Coupling to Vacuum Fields. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 1592–1596. 10.1002/anie.201107033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera F.; Spano F. C. Cavity-controlled chemistry in molecular ensembles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 238301. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.238301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galego J.; Garcia-Vidal F. J.; Feist J. Suppressing photochemical reactions with quantized light fields. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13841. 10.1038/ncomms13841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalewski M.; Bennett K.; Mukamel S. Cavity Femtochemistry: Manipulating Nonadiabatic Dynamics at Avoided Crossings. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 2050–2054. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b00864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galego J.; Garcia-Vidal F. J.; Feist J. Many-Molecule Reaction Triggered by a Single Photon in Polaritonic Chemistry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 136001. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.136001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csehi A.; Halás G. J.; Cederbaum L.; Vibók Á. Competition between Light-Induced and Intrinsic Nonadiabatic Phenomena in Diatomics. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 1624–1630. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.7b00413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vendrell O. Coherent dynamics in cavity femtochemistry: Application of the multi-configuration time-dependent Hartree method. Chem. Phys. 2018, 509, 55–65. 10.1016/j.chemphys.2018.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szidarovszky T.; Halasz G. J.; Csaszar A. G.; Cederbaum L. S.; Vibok A. Conical Intersections Induced by Quantum Light: Field-Dressed Spectra from the Weak to the Ultrastrong Coupling Regimes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 6215–6223. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.8b02609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triana J. F.; Peláez D.; Sanz-Vicaro J. L. Entangled Photonic-Nuclear Molecular Dynamics of LiF in Quantum Optical Cavities. J. Phys. Chem. A 2018, 122, 2266–2278. 10.1021/acs.jpca.7b11833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munkhbat B.; Wersäll M.; Baranov D. G.; Antosiewicz T. J.; Shegai T. Suppression of photo-oxidation of organic chromophores by strong coupling to plasmonic nanoantennas. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaas9552 10.1126/sciadv.aas9552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong X.; Chervy T.; Wang S.; George J.; Thomas A.; Hutchison J. A.; Devaux E.; Genet C.; Ebbesen T. W. Non-Radiative Energy Transfer Mediated by Hybrid light–matter States. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 6202–6206. 10.1002/anie.201600428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong X.; Chervy T.; Zhang L.; Thomas A.; George J.; Genet C.; Hutchison J. A.; Ebbesen T. W. Energy Transfer between Spatially Separated Entangled Molecules. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 9034–9038. 10.1002/anie.201703539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles D. M.; Somaschi N.; Michetti P.; Clark C.; Lagoudakis P. G.; Savvidis P. G.; Lidzey D. G. Polariton-mediated energy transfer between organic dyes in a strongly coupled optical microcavity. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 712–719. 10.1038/nmat3950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stranius K.; Herzog M.; Börjesson K. Selective manipulation of electronically excited states through strong light–matter interactions. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2273. 10.1038/s41467-018-04736-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz T.; Hutchison J. A.; Leonard J.; Genet C.; Haacke S.; Ebbesen T. W. Polariton Dynamics under Strong Light-Molecule Coupling. ChemPhysChem 2013, 14, 125–131. 10.1002/cphc.201200734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Wang H.-Y.; Bozzola A.; Toma A.; Panaro S.; Raja W.; Alabastri A.; Wang L.; Chen Q.-D.; Xu H.-L.; Angelis F. D.; Sun H.-B.; Zaccaria R. P. Dynamics of Strong Coupling between J-Aggregates and Surface Plasmon Polaritons in Subwavelength Hole Arrays. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 6198–6205. 10.1002/adfm.201601452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- George J.; Wang S.; Chervy T.; Canaguier-Durand A.; Schaeffer G.; Lehn J.-M.; Hutchison J. A.; Genet C.; Ebbesen T. W. Ultra-strong coupling of molecular materials: spectroscopy and dynamics. Faraday Discuss. 2015, 178, 281–294. 10.1039/C4FD00197D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzog M.; Wang M.; Mony J.; Börjesson K. Strong light–matter interactions: a new direction within chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 937–961. 10.1039/C8CS00193F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro R. F.; Martinéz-Martinéz L. A.; Du M.; Campos-Gonzalez-Angule J.; Yuen-Zhou J. Polariton chemistry: controlling molecular dynamics with optical cavities. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 6325–6339. 10.1039/C8SC01043A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebbesen T. W. Hybrid light–matter States in a Molecular and Material Science Perspective. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 2403–2412. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somaschi N.; Mouchliadis L.; Coles D.; Perakis I. E.; Lidzey D. G.; Lagoudakis P. G.; Savvidis P. G. Ultrafast polariton population build-up mediated by molecular phonons in organic microcavities. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 143303. 10.1063/1.3645633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Agranovich V. M.; Litinskaia M.; Lidzey D. G. Cavity polaritons in microcavities containing disordered organic semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2003, 67, 085311. 10.1103/PhysRevB.67.085311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Litinskaya M.; Reineker P.; Agranovich V. M. Fast polariton relaxation in strongly coupled organic microcavities. J. Lumin. 2004, 110, 364–372. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2004.08.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Virgili T.; Coles D.; Adawi A. M.; Clark C.; Michetti P.; Rajendran S. K.; Brida D.; Polli D.; Cerullo G.; Lidzey D. G. Ultrafast polariton relaxation dynamics in an organic semiconductor microcavity. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2011, 83, 245309. 10.1103/PhysRevB.83.245309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lidzey D. G.; Bradley D. D. C.; Virgili T.; Armitage A.; Skolnick M.; Walker S. Room Temperature Polariton Emission from Strongly Coupled Organic Semiconductor Microcavities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 82, 3316–3319. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.3316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coles D. M.; Grant R.; Lidzey D. G.; Clark C.; Lagoudakis P. G. Imaging the polariton relaxation bottleneck in strongly coupled organic semiconductor microcavities. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2013, 88, 121303. 10.1103/PhysRevB.88.121303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chovan J.; Perakis I. E.; Ceccarelli S.; Lidzey D. G. Controlling the interactions between polaritons and molecular vibrations in strongly coupled organic semiconductor microcavities. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2008, 78, 045320. 10.1103/PhysRevB.78.045320. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- del Pino J.; Feist J.; Garcia-Vidal F. J. Quantum Theory of Collective Strong Coupling of Molecular Vibrations with a Microcavity Mode. New J. Phys. 2015, 17, 053040. 10.1088/1367-2630/17/5/053040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman T.; Aizpurua J. Origin of the Asymmetric Light Emission from Molecular Exciton-Polaritons. Optica 2018, 5, 1247. 10.1364/OPTICA.5.001247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- del Pino J.; Schröder F. A. Y. N.; Chin A. W.; Feist J.; Garcia-Vidal F. J. Tensor Network Simulation of Non-Markovian Dynamics in Organic Polaritons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 227401. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.227401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michetti P.; La Rocca G. C. Polariton-polariton scattering in organic microcavities at high excitation densities. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2010, 82, 115327. 10.1103/PhysRevB.82.115327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michetti P.; La Rocca G. C. Simulation of J-aggregate microcavity photoluminescence. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2008, 77, 195301. 10.1103/PhysRevB.77.195301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera F.; Spano F. C. Theory of nanoscale organic cavities: The essential role of vibration-photon dressed states. ACS Photonics 2018, 5, 65–79. 10.1021/acsphotonics.7b00728. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera F.; Spano F. C. Dark Vibronic Polaritons and the Spectroscopy of Organic Microcavities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118, 223601. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.223601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera F.; Spano F. C. Absorption and Photoluminescence in Organic Cavity QED. Phys. Rev. A: At., Mol., Opt. Phys. 2017, 95, 053867. 10.1103/PhysRevA.95.053867. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vendrell O. Collective Jahn-Teller Interactions through light–matter Coupling in a Cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 253001. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.121.253001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tully J. C. Molecular dynamics with electronic transitions. J. Chem. Phys. 1990, 93, 1061–1071. 10.1063/1.459170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Otero R.; Barbatti M. Recent Advances and Perspectives on Nonadiabatic Mixed Quantum-Classical Dynamics. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 7026–7068. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenfest P. Bemerkung über die angenäherte Gültigkeit der klassischen Mechanik innerhalb der Quantenmechanik. Eur. Phys. J. A 1927, 45, 455–457. 10.1007/BF01329203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Granucci G.; Persico M.; Toniolo A. Direct semiclassical simulation of photochemical processes with semiempirical wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 2001, 114, 10608–10615. 10.1063/1.1376633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wersäll M.; Cuadra J.; Antosiewicz T. J.; Balci S.; Shegai T. Observation of Mode Splitting in Photoluminescence of Individual Plasmonic Nanoparticles Strongly Coupled to Molecular Excitons. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 551–558. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b04659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou K.; Jayaprakash R.; Askitopoulos A.; Coles D. M.; Lagoudakis P. G.; Lidzey D. G. Generation of Anti-Stokes Fluorescence in a Strongly Coupled Organic Semiconductor Microcavity. ACS Photonics 2018, 5, 4343–4351. 10.1021/acsphotonics.8b00552. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coles D. M.; Michetti P.; Clark C.; Adawi A. M.; Lidzey D. G. Temperature dependence of the upper-branch polariton population in an organic semiconductor microcavity. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2011, 84, 205214. 10.1103/PhysRevB.84.205214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chikkaraddy R.; de Nijs B.; Benz F.; Barrow S. J.; Scherman O. A.; Rosta E.; Demetriadou A.; Fox P.; Hess O.; Baumberg J. J. Single-molecule strong coupling at room temperature in plasmonic nanocavities. Nature 2016, 535, 127–130. 10.1038/nature17974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eizner E.; Martínez-Martínez L. A.; Yuen-Shou J.; Kéna-Cohen S. Inverting Singlet and Triplet Excited States using Strong light–matter Coupling. Arxiv 2016, 1903.09251v1, 1–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.