Abstract

Background:

The association of the APOE ε4 allele with incident Alzheimer’s dementia is higher among European Americans (EAs) than African Americans (AAs), but similar for the rate of cognitive decline.

Objective:

To examine the racial differences in the association of the APOE ε4 allele with incident Alzheimer’s dementia and cognitive decline.

Methods:

Using a population-based sample of 5,117 older adults (66% AAs and 63% females), we identified cognitive trajectory groups from a latent class mixed model and examined the association of the APOE ε4 allele with these groups.

Results:

The frequency of the APOE ε4 allele was higher among AAs than EAs (37% versus 26%). Four cognitive trajectories were identified: slow, mild, moderate, and rapid. Overall, AAs had a lower baseline global cognition than EAs, and a higher proportion had rapid (7% versus 5%) and moderate (20% versus 15%) decline, but similar mild (44% versus 46%), and lesser slow (29% versus 34%) decline compared to EAs. Additionally, 25% of AAs (13% of EAs) with mild and 5% (<1% of EAs) with slow decline were diagnosed with incident Alzheimer’s dementia. The APOE ε4 allele was associated with higher odds of rapid and moderate decline compared to slow decline among AAs and EAs, but not with mild decline.

Conclusions:

AAs had lower cognitive levels and were more likely to meet the cognitive threshold for Alzheimer’s dementia among mild and slow decliners, explaining the attenuated association of the ε4 allele with incident Alzheimer’s dementia among AAs.

Keywords: Apolipoproteins E, Alzheimer’s disease, cognitive aging, race relations

INTRODUCTION

The development of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia is characterized by a rapid decline in cognitive function [1–3] and expected to increase with longer life expectancy and a growing number of older adults [4]. Non-Hispanic African Americans (AAs) have a higher occurrence of cognitive dysfunction than non-Hispanic European Americans (EAs) [5], although there is little evidence of increased cognitive aging among AAs compared to EAs [6–10]. The presence of the APOE ε4 allele increases the risk of Alzheimer’s dementia and cognitive decline [11–16]. Although, the association of the APOE ε4 allele with the rate of cognitive decline is similar between AAs and EAs [16], the association of the APOE ε4 allele with incident Alzheimer’s dementia is greater among EAs than AAs [17–23].

We hypothesize that racial differences in cognitive trajectories, as a function of level and decline, contributes to racial differences in the association of the APOE ε4 allele with clinically diagnosed incident Alzheimer’s dementia. The absence of racial differences in the rate of cognitive decline suggests that the differences for incident Alzheimer’s dementia may be attributed to lower cognitive performance among AAs compared to EAs. Since the APOE ε4 allele is more robustly associated with rate of cognitive decline than with level of cognitive function [16], the attenuated association of the APOE ε4 allele with incident Alzheimer’s dementia among AAs could be due to the cognitive threshold for clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia being similar to EAs. To test this hypothesis, we examine the population-level cognitive decline of 5,117 AAs and EAs based on the level of cognition and the rate of cognitive decline and show that the cognitive thresholds for incident Alzheimer’s dementia is not different among AAs and EAs. Further, we identify the homogeneous groups of cognition and examine the incidence of clinically diagnosed Alzheimer’s dementia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and examine how the APOE ε4 allele is associated with these groups among AAs and EAs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and participants

This is a longitudinal population-based study of the epidemiology of Alzheimer’s dementia in adults over the age of 65 years conducted over 18 years from 1993–2012 that enrolled 78.7% of all older adults from a geographically defined community of AAs and EAs [24]. Data was collected for up to six follow-up cycles for the original cohort, and two to five follow-up cycles for successive cohorts (four successive cohorts). A brief battery of cognitive tests was administered to all participants during in-home interviews in three-year cycles and a sample of these individuals were selected for a detailed clinical evaluation.

Our analytical sample was restricted to 5,117 participants with three or more cognitive assessments to reduce the impact of follow-up time on latent classification of cognitive trajectories. A total of 5,684 participants were excluded, including participants who died without a follow-up (N = 2,796), participants who declined follow-up participation (N = 171), participants with no DNA extracted (N = 1,949), participants with less three follow-ups (N = 688), participants with insufficient cognitive data (N = 78), and participants without demographic data (N = 3). Participants who did not provide three assessments had significantly lower baseline composite cognitive function test scores 0.253 versus 0.346 standard deviation units [SDU]; p < 0.0001) than those included in the sample, and participants who provided DNA samples had higher baseline cognitive scores (0.346 versus 0.147 SDU; p < 0.0001) compared to those who did not provide DNA samples.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The Rush University Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved the parent CHAP study and the use of data for research purposes. All participants enrolled in the study provided written informed consent before the beginning of the study.

Global cognitive function

A composite cognitive function was created using a short battery of four tests: two tests of episodic memory (immediate and delayed recall of the East Boston Story) [25, 26], one test of perceptual speed, a component of executive function (Symbol Digits Modalities Test) [27], and one test of general orientation and global cognition (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE]) [28]. The four test scores were standardized individually by centering and scaling each to their baseline mean and standard deviation, and then combined into a composite test score by averaging the four tests together [29]. The standardized score of 0 matches the average participant at baseline. However, a positive and negative score is indicative of better and poor cognitive tests.

Clinical diagnosis of incident Alzheimer’s dementia and MCI

Of the 5,117 participants in the population study, a stratified random sample of 2,055 participants under-went a uniform clinical evaluation that included a neurological examination based on a battery of 19 cognitive tests. A board-certified neurologist, blinded to previously collected data, but not blinded to race, diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease according to the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria [30]. However, the neuropsychologist was blinded to race. A clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia requires a history of cognitive decline and evidence of impairment in two or more cognitive domains, of which memory must be one. Participants who had impairment in one or more domains, but were not diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia, were classified as having mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [31], and participants who had no impairments in at least one domain were classified as no cognitive impairment (NCI). To maintain diagnostic uniformity across time and clinical decision makers, we developed cut points for impairment on 11 of the cognitive tests [32] and an algorithm for rating impairment in five cognitive domains. The cognitive test outpoints were not adjusted for race/ethnicity (because the study was designed to assess possible racial/ethnic differences in dementia), but they were adjusted for four levels of educational attainment (0–7 years, 8–11 years, 12–15 years, 16 or more years). The average composite cognitive function score at the time of clinical diagnosis of incident Alzheimer’s dementia was remarkably similar between AAs and EAs (–0.597 versus –0.549 SDU; p = 0.50), suggesting uniform application of diagnostic criteria for incident Alzheimer’s dementia across racial/ethnic categories (Supplementary Table 1).

Apolipoprotein E ε4 allele

Two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), rs7412 and rs429358, were used to determine APOE ε4 genotypes. These SNPs were genotyped in each subject at the Broad Institute for Population Genetics using the hME Sequenom MassARRAY® platform. Genotyping call rates were 100% for SNP rs7412, and 99.8% for SNP rs429358. Both SNPs were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium with p-values of 0.08 and 0.79, respectively. Based on these two SNPs, we created an indicator variable for participants with one or more copies of the APOE ε4 allele.

Demographic variables

Our analysis adjusted for demographic variables, such as age (measured in years and centered at 75), sex (males or females), and self-reported education (measured in number of years of schooling completed and centered at 12). Most of our analysis was stratified by race based on 1990 census.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive characteristics of the study sample were reported by means and standard deviations for continuous measures, and percentages for categorical measures. Sample characteristics were compared using two-sample independent t-test for continuous measures and chi-squared test statistic for categorical measures. We identified categories of severity in cognitive decline using a latent class mixed model with class-specific covariates for age, sex, and education, and interaction of age, sex, and education with years of follow-up among AAs and EAs [33]. Random effects were included for subject-specific variation in the intercept and the rate of cognitive decline. We fit the primary models with 3, 4, 5, and 6 latent-class-specific linear mixed models. The models with four latent classes provided the most parsimonious characterization of classes of cognitive trajectories based on better posterior probabilities (likelihood of classification) (Supplementary Figure 1) and the lack of considerable improvement in the BIC criteria. A multinomial logistic regression model was used to model the log odds ratio of belonging in each of the cognitive severity categories relative to belonging to the slow category with demographic characteristics and the presence of the APOE ε4 allele. To keep the latent classes independent of the APOE ε4 allele, we did not include the APOE ε4 allele in the latent-class specific mixed models. The latent class mixed model was fit using lcmm package in R software [34]. The association of the APOE ε4 allele with incident Alzheimer’s dementia was assessed by a generalized linear model with a logit link function from a quasi-binomial family to account for overdispersion using glm function in R program among AAs and EAs separately. We performed additional sensitivity analysis for two cognitive assessments instead of three cognitive assessments using a similar latent class model with four groups and truncation due to mortality using a joint modeling framework for longitudinal class-specific cognitive decline models and a survival model for time-to-mortality [35].

The latent class model was fit in 5,117 participants with three or more population-level composite cognitive function test scores. To validate the severity categories, we examined the sample weight adjusted proportion of participants in each latent class who were clinically diagnosed with incident Alzheimer’s dementia, MCI, and NCI among AAs and EAs. This analysis was performed in the 2,055 participants who underwent clinical diagnosis for incident Alzheimer’s dementia and MCI.

RESULTS

The CHAP study sample consisted of 5,117 participants with an average follow-up time of 10.0 (SD = 2.3) years, of which 3,361 (66%) were AAs with a large proportion of females (63%). The baseline characteristics of participants stratified by race/ethnicity are shown in Table 1. The average level of cognitive performance score for participants diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia did not differ between AAs and EAs. Compared to EAs, AAs were younger by two years, had 2.5 fewer years of education and 0.5 standard deviation lower global cognitive function score at baseline, and were more likely have an APOE ε4 allele.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of 5,117 participants from a biracial population sample

| All Participants Mean (SD) |

African Americans Mean (SD) |

European Americans Mean (SD) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 5,117 | N = 3,363 | N = 1,754 | ||

| Age, y | 71.4 (5.4) | 70.6 (4.8) | 72.8 (6.1) | <0.001 |

| Education, y | 12.5 (3.6) | 11.6 (2.6) | 14.2 (3.2) | <0.001 |

| Global cognition | 0.346 (0.653) | 0.182 (0.669) | 0.659 (0.486) | <0.001 |

| Years of follow-up | 9.9 (3.5) | 9.9 (3.4) | 10.0 (3.6) | 0.83 |

| Females, % | 3,233, 63% | 2,129, 63% | 1,105, 63% | 0.77 |

| APOE ε4 allele, % | 1,269, 33% | 898, 37% | 371, 26% | <0.001 |

Classification of cognitive trajectories and race/ethnicity

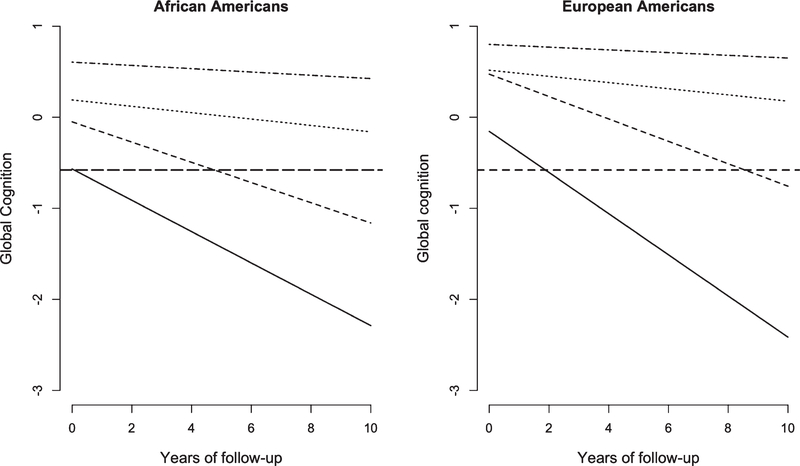

We identified four cognitive trajectory groups with differing levels and rates of cognitive decline among AAs and EAs. We labeled these groups, in order of severity of decline, as slow, mild, moderate, and rapid decline (Table 2 and Fig. 1). AAs had, on average, much lower baseline levels of global cognition than EAs. Rapid decliners were a small group (7% of AAs and 5% of EAs) with a higher rate of cognitive decline in EAs compared to AAs. Moderate decliners were a larger group among AAs than EAs (20% versus 15%) with a substantial rate of cognitive decline among AAs and EAs. Mild decliners were the largest group (44% of AAs and 46% of EAs) with similar rate of cognitive decline between AAs and EAs. The slow decliners were smaller than the mild decliners (29% of AAs versus 34% of EAs) with a much smaller rate of cognitive decline among AAs than EAs.

Table 2.

Coefficient (SE) for baseline level and the annual rate of cognitive decline and sample size by cognitive category among African Americans and European Americans

| Decline Group | All Participants Coefficient (SE) |

African Americans Coefficient (SE) |

European Americans Coefficient (SE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid | Baseline level | −0.479 (0.071) | −0.611 (0.098) | −0.155 (0.130) |

| Cognitive decline | 0.191 (0.012) | 0.176 (0.015) | 0.229 (0.021) | |

| Sample size, % | 309, 6% | 218, 7% | 91, 5% | |

| Moderate | Baseline level | 0.090 (0.028) | −0.058 (0.035) | 0.473 (0.039) |

| Cognitive decline | 0.114 (0.005) | 0.111 (0.007) | 0.123 (0.010) | |

| Sample size, % | 951, 19% | 688, 20% | 263, 15% | |

| Mild | Baseline level | 0.303 (0.012) | 0.184 (0.021) | 0.517 (0.023) |

| Cognitive decline | 0.034 (0.002) | 0.035 (0.003) | 0.034 (0.004) | |

| Sample size (%) | 2,270, 44% | 1,463, 44% | 807, 46% | |

| Slow | Baseline level | 0.685 (0.011) | 0.605 (0.019) | 0.815 (0.019) |

| Cognitive decline | 0.016 (0.001) | 0.018 (0.002) | 0.015 (0.003) | |

| Sample size (%) | 1,587, 31% | 991, 29% | 596, 34% | |

Fig. 1.

Predicted 10-year course of cognitive decline in four severity categories among African Americans and European Americans. The solid line shows rapid decliners, dashed line shows moderate decliners, dotted line shows mild decliners, and dotted and dashed line shows slow decliners. The bold dashed line is average level of global cognitive function among those developing incident Alzheimer’s dementia.

Classification of cognitive trajectories and development of incident Alzheimer’s dementia and MCI

The four cognitive trajectory groups differed widely in the proportions developing clinically diagnosed incident Alzheimer’s dementia and MCI (Table 3). In our study, 23% of participants were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia and another 32% of participants were diagnosed with incident MCI. Subject-specific cognitive trajectories of those with incident Alzheimer’s dementia, MCI, and NCI varied among the four groups despite consistency in the average cognitive level at which the clinical diagnosis of incident Alzheimer’s dementia and MCI were made across AAs and EAs (Supplementary Figure 2). This variation reflected lower initial cognitive levels among AAs, which resulted in much shorter times to reach the cognitive threshold for Alzheimer’s dementia diagnosis for AAs than EAs, despite lesser or similar rates of cognitive decline.

Table 3.

Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia (AD), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and no cognitive impairment (NCI) of 2,055 African Americans (AAs) and European Americans (EAs) belonging to the four severity categories

| Decline Group | AD (N, %*) |

MCI (N, %*) |

NCI (N, %*) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAs N=326 |

EAs N=153 |

AAs N=430 |

EAs N=232 |

AAs N=416 |

EAs N=498 |

|

| Rapid | 56, 80% | 18, 90% | 12, 17% | 2, 10% | 2, 3% | 0, 0% |

| Moderate | 120, 59% | 87, 60% | 65, 32% | 37, 26% | 18, 9% | 20, 14% |

| Mild | 130, 25% | 46, 13% | 220, 43% | 123, 34% | 162, 32% | 193, 53% |

| Slow | 20, 5% | 2, <1% | 133, 34% | 70, 20% | 234, 61% | 285, 80% |

Percentage of persons in the race-specific diagnostic group.

Among rapid decliners, the proportion of participants developing incident Alzheimer’s dementia was high among AAs (80%) and EAs (90%), and the average time to development of incident Alzheimer’s dementia was short. The moderate decliners also showed a similar pattern where about 60% of AAs and EAs developed incident Alzheimer’s dementia. As the rate of cognitive decline became less severe, racial/ethnic differences in proportions developing incident Alzheimer’s dementia increased. In the mild group, AAs were twice as likely to be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia as EAs (25% of AAs versus 13% of EAs). In the slow group, only a small fraction was clinically diagnosed with incident Alzheimer’s dementia (5% of AAs and <1% of EAs). The large higher proportion of AAs in the mild group accounted for much of the observed overall difference in the prevalence of Alzheimer’s dementia between AAs and EAs. Additionally, a consistently higher proportion of AAs across the four groups were classified as incident MCI than EAs; mostly due to lower initial levels of cognition.

The APOE ε4 allele association

The proportions of participants having the APOE ε4 allele was higher among AAs than EAs in all four groups, and higher in the rapid and moderate groups than in the mild or slow groups for both AAs and EAs (Supplementary Table 2). Among both AAs and EAs, the presence of the APOE ε4 allele was associated with being classified as rapid or moderate decline instead of the slow decline: the strength of this association was similar for both racial/ethnic groups (Table 4). However, the presence of the APOE ε4 allele was not associated with being classified as a mild decliner compared to a slow decliner among either AAs or EAs. The large size of the mild decline group, and AAs being twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s dementia than EAs, might explain some of the attenuated association of the APOE ε4 allele with incident Alzheimer’s dementia.

Table 4.

Relative odds of being classified as rapid, moderate, and mild decline compared to slow decline, according to sample characteristics, by race

| Compared to Slow Decline |

Characteristics | African Americans Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

White Participants Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid | Age | 1.02 (0.97, 1.09) | 1.18 (1.10, 1.26)* |

| Education | 0.92 (0.86, 0.98)† | 1.08 (0.95, 1.24) | |

| Females | 0.93 (0.60, 1.45) | 2.10 (0.84, 6.73) | |

| APOE ε4 allele | 3.44 (2.24, 5.33)* | 2.34 (1.46, 3.74)* | |

| Moderate | Age | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) | 1.15 (1.13, 1.21)* |

| Education | 0.84 (0.80, 0.87)* | 1.05 (1.00, 1.11)† | |

| Females | 0.87 (0.68, 1.12) | 1.14 (0.78, 1.69) | |

| APOE ε4 allele | 1.80 (1.40, 2.30)* | 2.24 (1.54, 3.26)* | |

| Mild | Age | 0.93 (0.91, 0.95)* | 1.07 (1.05, 1.10)* |

| Education | 0.88 (0.85, 0.90)* | 1.18 (1.14, 1.22)* | |

| Females | 0.98 (0.82, 1.18) | 0.79 (0.62, 0.99)† | |

| APOE ε4 allele | 0.98 (0.82, 1.19) | 0.89 (0.70, 1.12) | |

p < 0.001;

p < 0.05.

After adjusting for age, sex, and education, the APOE ε4 allele was weakly associated with incident Alzheimer’s dementia among AAs (OR = 1.45, 95% CI = 1.13, 1.86), whereas this association appeared larger among EAs (OR = 2.50, 95% CI = 1.80, 3.48). As a sensitivity analysis, after excluding mild decliners with incident Alzheimer’s dementia, we found that the association of the APOE ε4 allele was similar between AAs (OR = 2.04, 95% CI = 1.45, 2.86) and EAs (OR = 2.64, 95% CI = 1.47, 4.71) (Supplementary Table 3). In a combined model with an interaction of the APOE ε4 allele with AA race/ethnicity, the odds ratio for the association of APOE ε4 allele with incident Alzheimer’s dementia was not significantly different between AAs and EAs (OR[interaction] = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.75, 1.10; p= 0.36).

DISCUSSION

Four cognitive trajectory groups were identified among AAs and EAs based on the initial level and the rate of cognitive decline. The cognitive groups explained some of the observed racial differences in the association of the APOE ε4 allele with incident Alzheimer’s dementia between AAs and EAs. The mild decline group had significantly lower levels of cognition, but similar rates of decline when compared to EAs. This resulted in a much higher proportion of AAs reaching a cognitive threshold consistent with the clinical diagnosis of incident Alzheimer’s dementia. The lack of association of the APOE ε4 allele with mild decline makes the overall association weaker among AAs compared to EAs. In addition, the association of the APOE ε4 allele with faster and moderate decline groups was similar between AAs EAs, and excluding moderate decliners diagnosed with incident Alzheimer’s dementia in AAs made the association of the APOE ε4 allele with incident Alzheimer’s dementia similar between AAs and EAs.

The identification of cognitive trajectory groups has some similarities to previous findings in a longitudinal sample of EAs [36]. Studies that were confined to those diagnosed with incident Alzheimer’s dementia only also reported four [37] to six groups [38], whereas we used our entire sample, irrespective of Alzheimer’s dementia status. Substantially smaller studies using the MMSE detected only two groups [39], and memory scores detected three groups [40]. Most importantly, none of these studies provide race-specific analyses of changes in cognitive function and their association to a clinical diagnosis of incident Alzheimer’s dementia and MCI. Cognitive decline in participants with no cognitive impairment was similar among AAs and EAs, consistent with previous reports [6–9].

Several studies have reported null or weaker association between the APOE ε4 allele and incident Alzheimer’s dementia among AAs [17–23]. Some of these studies might also consist of mild decliners. The lack of association of the APOE ε4 allele with mild decliners among AAs had not been shown previously. The association of the APOE ε4 allele with rapid and moderate decline was similar between AAs and EAs. An earlier report from the CHAP study reported weak associations of the APOE ε4 allele with a clinical diagnosis of incident Alzheimer’s dementia among AAs [22]. However, using the same data, if AAs with mild cognitive decline were excluded from being clinically diagnosed with incident Alzheimer’s dementia then the association of APOE ε4 allele with a clinical diagnosis of incident Alzheimer’s dementia was similar between AAs and EAs. Racial differences in cognitive levels between AAs and EAs can be explained by demographic, social, and cognitive activities [41] and the association of the APOE ε4 allele with cognitive level did not differ between AAs and EAs [16].

Age-associated cognitive decline was more severe among EAs than AAs. Years of formal education was protective for MCI among AAs, suggesting the importance of education among minority groups [42]. However, EAs with more years of formal education were likely to have moderate and mild decline, a pattern usually observed in individuals with higher cognitive reserve. Cognitive classifications could also be markedly different with risk factors not included in this study. By restricting our length of follow-up to three or more cognitive assessments instead of two or more cognitive assessments did not change the rate of cognitive decline or the class membership rates, but the cognitive levels were lower for those with two or more cognitive assessments in the rapid and moderate decliners, but not in the mild and slow groups.

Restricting our sample to participants with three or more cognitive assessments provided a smoothed estimate of long-term changes in cognition, making our estimates of latent classes and cognitive trajectories more generalizable. Attrition due to non-participation in participants with three or more cognitive assessments was low. However, attrition due to mortality was 38% that showed an increasing pattern with severity of cognitive decline ranging from 24% among slow to 77% among rapid decliners, which was consistent among AAs and EAs. Additional sensitivity analysis for truncation due to mortality suggests that cognitive decline estimates in rapid and moderate decliners were about 10–15% higher, making our estimates in those two groups conservative, especially since APOE ε4 allele also increases the risk of mortality [43]. Including the baseline global cognitive function level in the latent class models did not modify the group compositions or the rate of cognitive decline. The APOE ε4 allele was associated with faster rate of cognitive decline in rapid and moderate decline that was similar in AAs and EAs, including the APOE ε4 allele in the latent models did not influence the groupings, but made the rapid and moderate groups larger by 2%. Since, functional impairment is not a NINCDS/ADRDA dementia criterion, in part because of the difficulty in uniformly assessing it across different age, socioeconomic, and cultural groups, our diagnostic criteria did not use impairment. Our study was limited to basic demographic factors and the APOE genotype but including other risk factors may provide a different categorization of cognitive trajectories.

Although cognitive decline was slower among AAs than EAs, differences in initial levels of composite cognitive function resulted in higher proportion of AAs being clinically diagnosis with incident Alzheimer’s dementia than EAs, especially AAs with mild decline. The APOE ε4 allele was not associated with mild decline even though AAs with mild decline were twice as likely to be diagnosed with incident Alzheimer’s dementia. In summary, using the rate of cognitive decline as an outcome measure in gene-based studies, in addition to incident Alzheimer’s dementia, might provide a better understanding of the underlying genetic risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study is funded by the NIH grants R01-AG051635, RF1-AG057532, and R01-AG058679.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/19-0538r2).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-190538.

REFERENCES

- [1].Dixon RA, de Frias CM (2004) The Victoria Longitudinal Study: From characterizing cognitive aging to illustrating changes in memory compensation. Aging Neuropsychol Cogn 11, 346–376. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Berg S (1996) Aging, behavior, and terminal decline In: Birren JE, Schaie KW, eds. Handbook of the psychology of aging. Academic Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Daviglus ML, Bell CC, Berrettini W, Bowen PE, Connolly ES Jr, Cox NJ, Dunbar-Jacob JM, Granieri EC, Hunt G, McGarry K, Patel D, Potosky AL, Sanders-Bush E, Silberberg D, Trevisan M (2010) National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: Preventing Alzheimer’s Disease and Cognitive Decline. NIH Consens State Sci Statements 27, 1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Colby SL, Ortman JM (2015) Projections of the size and composition of the US Population: 2014 to 2060, 25–1143. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Rajan KB, Weuve J, Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Evans DA (2019) Prevalence and incidence of clinically diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease dementia from 1994 to 2012 in a population study. Alzheimers Dement 15, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Atkinson HH, Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Penninx BW, Fried LP, Guralnik JM, Williamson JD (2005) Predictors of combined cognitive and physical decline. J Am Geriatr Soc 53, 1197–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Masel MC, Peek MK (2009) Ethnic differences in cognitive function over time. Ann Epidemiol 19, 778–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Castora-Binkley M, Peronto CL, Edwards JD, Small BJ (2015) A longitudinal analysis of the influence of race on cognitive performance. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 70, 512–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Marsiske M, Dzierzewski JM, Thomas KR, Kasten L, Jones RN, Johnson K, Willis SL, Whitfield KE, Rebok GW (2013) Race-relateddisparitiesin5-yearcognitivelevelandchange in untrained Active participants. J Aging Health 25, 103S–127S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wilson RS, Capuano AW, Sytsma J, Bennett DA, Barnes LL (2015) Cognitive aging in older Black and White Persons. Psychol Aging 30, 279–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Strittmatter WJ, Saunders AM, Schmechel D, Pericak-Vance M, Enghild J, Salvesen GS, Roses AD (1993) Apolipoprotein E: High-avidity binding to beta-amyloid and increased frequency of type 4 allele in late-onset familial Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90,1977–1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Saunders Strittmatter WJ, Schemchel D (1993) Association of apolipoprotein E allele epsilon 4 with late-onset familial and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 43, 1467–1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, Hyman B, Kukull WA, Mayeux R, Myers RH, Pericak-Vance MA, Risch N, van Duijn CM (1997) Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer’s disease. JAMA 278, 1349–1356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Knopman DS, Mosley TH, Catellier DJ, Coker LH; Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study Brain MRI Study (2009) Fourteen-year longitudinal study of vascular risk factors, APOE genotype, and cognition: The ARICMRI Study. Alzheimers Dement 5, 207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bretsky P, Guralnik JM, Launer L, Albert M, Seeman TE; MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging (2003) The role of APOE-epsilon4 in longitudinal cognitive decline: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Neurology 60, 1077–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Rajan KB, Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Weuve J, McAninch EA, Evans DA (2019) Apolipoprotein E genotypes, age, race, and cognitive decline in a population sample. J Am Geriatr Soc 67, 734–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Packard C, Westendorp R, Stott D, Caslake MJ, Murray HM, Shepherd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, Bollen EL, Buckley BM, Cobbe SM, Ford I, Gaw A, Hyland M, Jukema JW, Kamper AM, Macfarlane PW, Jolles J, Perry IJ, Sweeney BJ, Twomey C; Prospective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk Group (2007) Association between apolipoprotein E4 and cognitive decline in elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 55, 1777–1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Maestery G, Ottman R, Stern Y, Gurland B, Chun M, Tang MX, Shelanski M, Tycko B, Mayeux R (1995) Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer’s disease: Ethnic variation in genotypic risks. Ann Neurol 37, 254–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Tang MX, Stern Y, Marder K, Bell K, Gurland B, Lantigua R, Andrews H, Feng L, Tycko B, Mayeux R (1998) The APOE-ε4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer disease among African Americans, whites, and Hispanics. JAMA 279, 751–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Blair CK, Folsom AR, Knopman DS, Bray MS, Mosley TH, Boerwinkle E; Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study Investigators (2005) APOE genotype and cognitive decline in a middle-aged cohort. Neurology 64, 268–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mayeux R, Stern K, Ottman R, Tatemichi TK, Tang MX, Maestre G, Ngai C, Tycko B, Ginsberg H (1993) The Apolipoprotein 4 allele in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 34, 752–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Evans DA, Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Morris MC, Scherr PA, Hebert LE, Aggarwal N, Beckett LA, Joglekar R, Berry-Kravis E, Schneider J (2003) Incidence of Alzheimer disease in a biracial urban community. Arch Neurol 60, 185–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hendrie HC, Hall KS, Hui S, Unverzagt FW, Yu CE, Lahiri DK, Sahota A, Farlow M, Musick B, Class CA (1995) Apolipoprotein E genotypes and Alzheimer’s disease in a community study of elderly African Americans. Ann Neurol 37, 118–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bienias JL, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Evans DA (2003) Design of the Chicago Health and Aging Project (CHAP). J Alzheimers Dis 5, 349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Albert M, Smith LA, Scherr PA, Taylor JO, Evans DA, Funkenstein HH (1991) Use of brief cognitive tests to identify individuals in the community with clinically diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Neurosci 57, 167–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Bienias JL, Aggarwal NT, Mendes De Leon CF, Morris MC, Schneider JA, Evans DA (2002) Cognitive activity and incident AD in a population-based sample of older adults. Neurology 59, 1910–1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Smith A (1982) Symbol Digit Modalities Test manual-revised. Western Psychological, Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh TR (1975)“Mini-Mental State”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wilson RS, Benette DA, Beckett LA, Morris MC, Gilley DW, Bienias JL, Scherr PA, Evans DA (1999) Cognitive activity in older persons from a geographically defined population. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 54, 155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan M (1984) Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 34,939–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wilson RS, Aggarwal NT, Barnes LL, Mendes de Leon CF, Hebert LE, Evans DA (2010) Cognitive decline in incident Alzheimer disease in a community population. Neurology 74, 951–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Yang J, James BD, Bennett DA (2015) Early life instruction in foreign language and music and incidence of mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychology 29, 292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Proust-Lima C, Amieva H, Jacqmin-Gadda H (2013) Analysis of multivariate mixed longitudinal data : A flexible latent process approach. Br J Math Stat Psychol 66, 470–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Proust-Lima C, Philipps V, Liquet B (2015) Estimation of Extended Mixed Models Using Latent Classes and Latent Processes: The R package lcmm, Arxiv. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Rizopoulos D (2012) Joint models for longitudinal and time to-event data. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Marioni RE, Proust-Lima C, Amieva H, Brayne C, Matthews FE, Dartigues JF, Jacqmin-Gadda H (2014) Cognitive lifestyle jointly predicts longitudinal cognitive decline and mortality risk. Eur J Epidemiol 29, 211–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Leoutsakos JS, Forrester SN, Corcoran CD, Norton MC, Rabins PV, Steinberg MI, Tschanz JT, Lyketsos CG (2015) Latent classes of course in Alzheimer’s disease and predictors: The Cache County Dementia Progression Study. Int J Ger Psychiatry 30, 824–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wilkosz P, Seltman HJ, Devlin B, Devlin B, Weamer EA, Lopez OL, DeKosky ST, Sweet RA (2010) Trajectories of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr 22, 281–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Small BJ, Backman L (2007) Longitudinal trajectories of cognitive change in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: A growth mixture modeling analysis. Cortex 43, 826–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Pietrzak RH, Lim YY, Ames D, Harrington K, Restrepo C, Martins RN, Rembach A, Laws SM, Masters CL, Villemagne VL, Rowe CC, Maruff P; Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) Research Group (2015) Trajectories of memory decline in preclinical ssAlzheimer’s disease: Results from the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle Flag-ship Study of Ageing. Neurobiol Aging 36, 1231–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wilson RS, Rajan KB, Barnes LL, Weuve J, Evans DA (2016) Factors related to racial differences in late-life level of cognitive function. Neuropsychology 30, 517–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Evans DA, Mendes de Leon CF (2011) Racial differences in the association of education with physical and cognitive function in older Blacks and Whites. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 66, 354–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Rajan KB, Barnes LL, Wilson RS, McAninch EA, Weuve J, Sighoko D, Evans DA (2017) Racial differences in the association between apolipoprotein E risk alleles and overall and total cardiovascular mortality over 18 years. J Am Geriatr Soc 65, 2425–2430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.