Abstract

Foot ulcers are one of the major complications of Diabetes Mellitus and are associated with increasing rates of morbidity and mortality. It is estimated that 2% of diabetic patients present lesions in the feet, with relapse rates between 30% and 40% in the first year after healing of the first ulcerations. Therapeutic footwear is one of the main strategies to prevent foot ulceration. OBJECTIVES: To identify in the literature aspects related to the recommendation of health professionals and the use of therapeutic footwear by patients with Diabetes Mellitus. MATERIALS AND METHODS: Scoping review of literature in the Scopus, Scielo, Pubmed and Cochrane databases, using diabetic foot crosswords and therapeutic footwear. RESULTS: Twenty-six articles were included in this review. The majority was systematic reviews (46.15%) with published date from 2016 (38.5%). Of the 26 articles included, 10 (38.5%) referred to adherence to the use of footwear, 10 (38.5%) the difficulty to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention and 6 (23.0%) to changes in the balance and biomechanics patterns In the studies, the use of therapeutic footwear is linked to the reduction of the risk of ulceration or its recurrence in people with diabetes who already have diabetic neuropathy as chronic complication of the disease. CONCLUSIONS: Therapeutic footwear for diabetics was able to produce significant reductions of peak plantar pressure in static and dynamic analysis, being more efficient than a common footwear, and could contribute to the prevention of injuries associated with diabetic foot.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, Diabetic neuropathy, Therapeutic footwear, Diabetic foot

Introduction

A serious health problem in people with Diabetes Mellitus (DM) is foot ulceration, since an initially simple injury can lead to functional losses [1, 2] and culminate in limb amputation or even death. Every year, more than 1 million people with diabetes lose at least part of their leg because of diabetes complications. This translates into the estimation that every 20 s a lower limb is lost to diabetes somewhere in the world [3].

Several factors are involved in the development of foot ulcers in people with diabetes such as neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease, limiting joint movements, trophic skin disorders and abnormal distribution of mechanical forces in the feet [4–6]. Among them, the most important etiological factor is peripheral diabetic neuropathy [7]. The evolution of diabetic neuropathy brings several somatosensory alterations that make the disease even more progressive, leading to instability and kinematic changes in locomotion and posture, which increases the risk of fall, formation of ulcers and even amputations [8], because in most of these patients, peripheral neuropathy plays a central role, more than 50% of type 2 diabetic patients present neuropathy and feet at risk.

Peripheral diabetic neuropathy (NDP) leads to insensitivity (loss of protective sensation) and, subsequently, to deformity of the foot, with the possibility of abnormal gait. Foot deformity and limited joint mobility may result in abnormal biomechanical load of the foot, with formation of hyperkeratosis (callus), which culminates with altered skin integrity (ulcer) and other biomechanical changes. With the absence of pain and sensitivity, the patient continues walking, which impairs healing [9] and corroborates the worsening of the lesion.

Thus, if the magnitude of forces is sufficiently high in a plantar region, the occurrence of any loss of skin or hypertrophy of the stratum corneum (callus) will increase the risk of ulceration by two orders of magnitude. It is understood that the risk of ulceration is proportional to the number of risk factors, and that these increase 1.7 times in people diagnosed with peripheral neuropathy, rising to 12 times in people with neuropathy and deformity of the foot and 36, in those with neuropathy, deformity and previous amputation, when compared to people without risk factors [10].

The combination of foot deformity, loss of protective sensation, inadequate off-loading, and a minor trauma leads to tissue damage and ulceration, which, once installed, may be chronically delayed [11].

In this cases, interventions and technologies aiming the treatment and prevention of injuries associated to peripheral diabetic neuropathy, such as the therapeutic footwear, are crucial. Therapeutic Footwear is the generic term used for shoes designed as a form of treatment, which can be customized / adapted or prefabricated to decrease aggression in the ulcer bed [12], which have been advocated worldwide by the National Health Medical Research Council (NHMRC) [13] and the International Diabetes Foot Consensus (IDF) [14].

The prescription of therapeutic footwear is suggested to relieve plantar pressure during walking (30% load reduction), prevent recurrent plantar ulcers in at-risk patients, and strategies to encourage the use of shoes by patients. In addition, patients at risk (with deformities, high risk of ulceration or recurrent ulcers) should have access to educational interventions for self-care and specific foot care, such as the use of insoles and footwear that fit the anatomy of the feet and attenuate the effect of repetitive stress [15].

Although the use of therapeutic footwear is widely recommended and recommended for individuals who already have foot ulcerations [16, 17], the specific role in preventing the development of foot ulcers in patients at risk of development is still lacking in the literature, and, are therefore urgently needed, since their use in individuals who have already presented ulceration is widely defended and motivated by reducing the plantar pressures that are one of the risk factors for ulceration [18].

The interventions regarded as best practices and the literature published in recent years on the subject, with various levels of evidence, led to the conduction of this scoping review, with the objective to identify aspects referring to the recommendation of therapeutic footwear by health professionals and results of the use by patients with DM, and organize the studies according to level of evidence to make them more accessible to professionals, motivating the implementation of strategies that promote the adherence to best practices in the reduction of DM deaths and / or amputation, since it is done change in the behavior of individuals with diabetic neuropathy in relation to footwear to become permanent prior to a serious threatening event to the foot or limbs.

Material and method

Scoping literature review, carried out from August to November 2018, whose objective is to gather and synthesize research results on a particular topic or subject, in a systematic and ordely manner, contributing to the complete understanding of the subject to be studied [19], as a methodology that provides the synthesis of knowledge and the incorporation of the applicability of the results of significant studies in the practice.

In order to carry out this review, the following steps were observed: 1) identification of the theme and selection of the hypothesis or research question; 2) establishment of criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies, as well as the search in the literature; 3) definition of the information to be extracted from the selected research; 4) categorization and evaluation of included studies; 5) interpretation of the results and 6) synthesis of the evidenced knowledge [20, 21].

To make this integrative review operational, the following question was used as the guiding question: “What is the impact of the use of therapeutic footwear on people with diabetes mellitus?”

The inclusion criteria were defined by the selection of articles published in Portuguese and English; articles in full that portray the subject of the scoping review on the use of therapeutic footwear for people with diabetes who present some degree of ulceration, published and indexed in said databases in the last 10 years. The exclusion criteria were: publications in the form of thesis, dissertations, monographs, books, reviews of any style and reports of experience.

The articles were collected in internet databases specialized in biological and health sciences, using the following descriptors and their combinations: diabetic foot, therapeutic footwear and ulcerations in Portuguese and English with the exact term and associated descriptors.

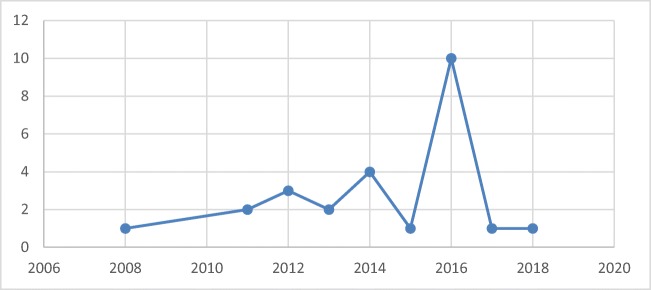

In order to find evidence to answer the research question, “ diabetic foot “ and “therapeutic footwear” were selected in the Health Sciences Descriptors (DECS) and in the Medical Subject Headings Section (MESH), combined by the Boolean AND and OR in the databases: National Library of Medicine of the USA (PUBMED), Scielo, Cochrane Library (Cochrane) and Scopus. Figure 1 shows the flow chart of selection and identification of the studies.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of selection and identification of studies

In order to extract the information, content was collected and processed in four phases: recognition, selective, critical or reflective and interpretive reading. A title and summary analysis was performed to confirm the inclusion within the inclusion criteria and later, the collection phase was organized, analyzed and interpreted according to each identified theme. For this purpose, a data collection instrument was developed by the authors adapted to the objectives of the research containing the following items: identification of the original article, methodological characteristics, types of diagnoses and main results.

Critical evaluation was performed by two reviewers before inclusion in the review and none was aware of the results of the other review until the end of this process. In the absence of consensus, among the reviewers, the differences that emerged were resolved through discussion with the inclusion of an experienced third reviewer. Data were extracted from the studies included in the corpus by two reviewers alone, using the instrument elaborated by the authors with basis in the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [22] data extraction, and the differences were resolved through discussion.

The results were presented in a descriptive way, allowing the reader to evaluate the applicability of the elaborated review, providing bases for clinical decision making on the use of therapeutic footwear in people with Diabetes Mellitus, as well as the identification of knowledge gaps such as development and improvement of future research.

The analyzes were performed through the reading, grouping and analysis of the articles, based on PICU strategy (patient, intervention, comparison and outcomes). The authors analyzed the data based on the PICO strategy where P = diabetic patients, I = therapeutic footwear, C = other strategies for prevention of foot injuries, and O = reduction of foot injuries.

Results

Of the 26 articles included in the review, 24 (92.30%) articles were published in English and only one in Portuguese (3.84%) and another in Spanish (3.84%).

As for the place of publication, 11 (42.30%) were produced in the United States of America, 06 (23.07%) in the United Kingdom, 03 (11.53%) in Amsterdam, 02 (7.69%), in the Netherlands, 02 (7.69%) in Brazil, 01 (3.84%) in France and 01 (3.84%) in Australia.

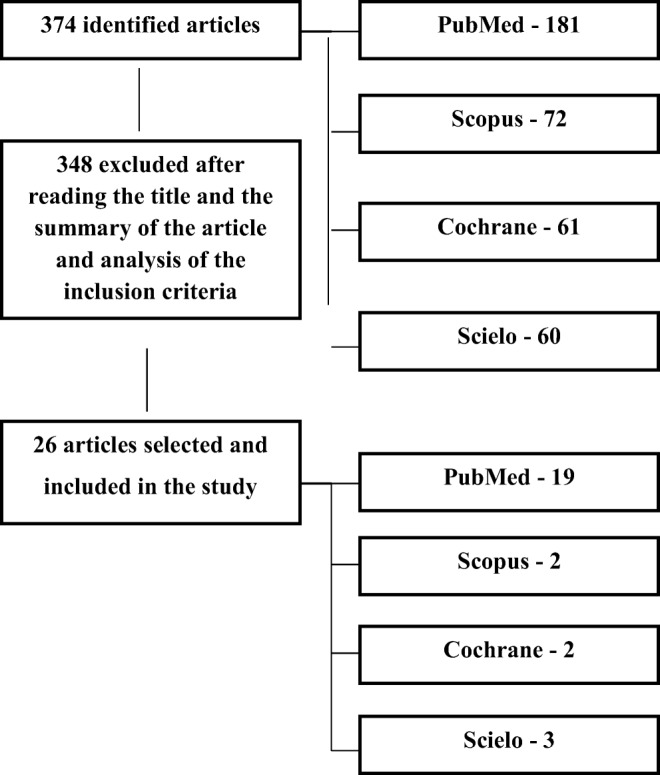

The most used method was systematic reviews (12 or 46.15%), clinical trials (5 or 19.23%), cross-sectional studies (4 or 15.38%) and the remainder were narrative reviews and studies (5 or 19.24%). Most articles published date from 2016 (10 or 38.5%), with similar distribution of publications in the other years, as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Timeline of the publications included in the review

Regarding the categories listed, with concern to studies related to the use of therapeutic footwear, the peculiarities regarding diabetes mellitus and diabetic foot were analyzed. After analyzing the texts, we were able to separate the selected articles and the synthesis of the studies identified and included in the present integrative review and their main results can be visualized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Evaluation of the use of therapeutic footwear in people with Diabetes Mellitus in the last 10 years

| Author, Year and Country | Type of Study | Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Mark LJ et al., 2014, Holanda [23] | Cross-sectional study |

P = 153 patients with diabetes, peripheral neuropathy and anterior plantar ulceration I = Personalized footwear. C = A questionnaire was used to evaluate the use of footwear in relation to weight, appearance, comfort, durability, use / withdrawal, stability, benefit and general valuation of their prescribed footwear. |

| Paton JS et al., 2013, Reino Unido [24] | Qualitative study |

P = 16 patients with diabetes and peripheral neuropathy. I = Therapeutic footwear. C = A questionnaire was used to evaluate the use of footwear in relation to confidence, stability and balance. |

| Healy A, Naemi R, Chockalingam N., 2014, EUA [25] | Systematic review |

P = Patients with diabetes, diabetic foot ulcers or the alteration of biomechanical factors. I = Therapeutic footwear C = Other removable discharge devices. |

| Arts ML et al., 2012, EUA [26] | Clinical trial |

P = 171 patients with diabetic neuropathy and plantar ulcers. I = Therapeutic footwear. C = Measured of the plantar pressure of walking barefoot and footwear. |

| Lázaro-Martínez JL et al., 2014, Espanha [27] | Cross-sectional study |

P = Individuals with diabetic neuropathy who presented biomechanical alterations for recurrence of ulceration. I = Effect of discharging tailored footwear. C = Use of barodopometry to evaluate the plantar pressures of individuals with footwear and bare feet. |

| Waaijman R et al., 2012, EUA [28] | Clinical trial |

P = 117 patients with diabetes, neuropathy and plantar foot ulcers. I = Therapeutic footwear. C = Use of barodopometry to evaluate the dynamic, plantar foot pressures. |

| Pataky Z et al., 2016, França [29] | Descriptive study |

P = Patients with diabetes I = Personalized footwear. C = Use of barodopometry to evaluate the dynamic pressures of the plantar foot in relation to discharging and footwear. |

| Bus SA et al., 2016, Reino Unido [30] | Systematic review |

P = Persons with diabetes. I = Therapeutic footwear and offloading. C = Benefits and damages, patient values and preferences, and costs (resource utilization). |

| Elraiyah T et al., 2016, Minnesota [31] | Systematic review |

P = Diabetic patients. I = Best available evidence for discharge methods. C = Protocol based on levels of evidence in relation to the benefits demonstrated with the use of discharge methods. |

| Arts ML , Bus SA, 2011, EUA [32] | Clinical trial |

P = 30 neuropathic diabetic patients. I = custom-made therapeutic footwear. C = Use of barodopometry to evaluate the number of steps required to validate plantar pressure. |

| Bus SA, Van Netten JJ, 2016, Amsterdã [33] | Systematic review |

P = Patients with diabetic foot. I = changes in foot care management. C = Protocol based on levels of evidence in relation to prevention and treatment of ulcer healing. |

| Hingorani Aet al, 2016, EUA [34] | Systematic review |

P = Patients with diabetic foot. I = Clinical practice guideline. C = Specific practice recommendations using the Grades of Recommendation Assessment, Development, and Evaluation system. |

| Bus SA, 2016, EUA [35] | Systematic review |

P = People with diabetes. I = Plantar pressure and temperature measurements in the diabetic foot. C = Use of barodopometry to evaluate the plantar pressure e termografic to temperatures. |

| Paton J et al., 2016, Reino Unido [36] | Systematic review |

P = patients with multiple sclerosis, idiopathic peripheral neuropathy and with diabetic neuropathy. I = Use of the vibrating insoles and AFO. C = Protocol based on levels of evidence regarding outcome measures after the use of therapeutic footwear and AFO. |

| Schaper NC et al., 2016, Holanda [37] | Systematic review |

P = persons with diabetes. I = Summary Guidance for Daily Practice. C = Describe the basic principles of prevention and management of foot problems in persons with diabetes. |

| Dy SM et al., 2017, EUA [38] | Systematic review |

P = People with diabetic peripheral neuropathy. I = Evidence for critical outcomes. C = Protocol based on levels of evidence in relation eligibility, risk of bias and critical outcomes. |

| Oliveira AF, De Marchi ACB, Leguisamo CP, 2016, Brasil [9] | Cross-sectional study, |

P = 10 diabetic patients with peripheral neuropathy. I = Therapeutic footwear. C = Evalution of plantar, static and dynamic peaks of pressure were measured in three situations: barefoot, standard shoes. |

| Padilha AP et al., 2018, Brasil [39] | Narrative review of the scoping study |

P = people with diabetes mellitus with diabetic foot. I = Contents of the manual educational. C = Not applicable |

| N.Even, 2016, Espanha [40] | Clinical study |

P = Diabetic patients with peripheral neuropathy. I = Preventive orthoses. C = A questionnaire was used to evaluate the use of orthoses in relation to education and autonomy of the patient and the integrity of the feet. |

| Lewis J, Lipp A, 2013, Reino Unido [41] | Systematic review |

P = Patients diabetic I= = Therapeutic footwear. C = Effects of pressure-relieving interventions on the healing of foot ulcers in people with diabetes. |

| Chen WM, Lee SJ, Lee PV, 2015, Austrália [42] | Cross-sectional study |

P=Patients diabetic and rheumatoid arthritis to relieve ulcer risks and pain. I = Therapeutic footwear. C = The sensitivity and geometric effects of the insole were analyzed in relation to the thickness, fit of the metatarsal element and peak of plantar pressure. |

| Bus A et al., 2008, Amisterdã [17] | Systematic review |

P = patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus, with plantar foot ulceration. I = Effectiveness of footwear and offloading C=Interventions were assigned into four subcategories: casting, footwear, surgical offloading and other offloading techniques. |

| Jaap J. van Netten et al., 2018, Austrália [43] | Systematic review |

P = People with diabetes. I = Create an updated Australian guideline on footwear. C = Protocol based on levels of evidence in relation new footwear publications, (inter)national guidelines, and consensus expert opinion alongside the 2013 Australian footwear guideline. |

| Sicco A. et al., 2011, Reino Unido [44] | Clinical trial |

P = 23 patients with neuropathic diabetic. I = Therapeutic footwear. C = Analysis of plantar pressure in regions with a peak>200 kPa, aiming at the optimization of footwear. |

| Paton JS et al. 2014, Reino Unido [45] | Phenomenological study |

P = 4 people who are at risk of diabetic neuropathic foot ulceration. I = Therapeutic footwear C = Used interview semi structure of intentional selection in relation to the feelings and thoughts of the people after the use of the therapeutic footwear. |

| Lavery LA et al., 2012, EUA [46] | Randomized control study |

P = 299 patients with diabetic neuropathy and loss of protective sensitivity, foot deformity or history of foot ulceration. I = Therapeutic footwear. C = Standard therapy group (therapeutic footwear, diabetic foot education, and regular foot evaluation by a podiatrist) or a group with a shear reducer insole (new insole designed to reduce pressure and shear in the sole of the foot) |

Legend: P=Patients; I=Interventions; C=Control

The level of scientific evidence was considered according to the Oxford Center for Evidence-Based Medicine Classification, because the level of evidence in science corresponds to the approach taken to classify the evidence strength of scientific studies, referring to the method used in obtaining information or decision according to its scientific credibility, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Level of scientific evidence and results presented on the use of therapeutic footwear in people with Diabetes Mellitus in the last 10 years

| Author, Year and Country | Results (R) and Conclusions (C) | Degree of Recommendation | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mark LJ et al., 2014, Holanda [23] | The use of footwear was low to moderate and dependent only on the perceived benefit of footwear. Therefore, professionals should focus on improving patient assessment of the therapeutic benefit of custom-made footwear. | B | 2C |

| Paton JS et al., 2013, Reino Unido [24] |

R = Engaging with patients to address these needs and concerns can improve the viability and acceptance of therapeutic footwear to reduce the risk of foot ulcers and increase confidence in balance. C = People with diabetic neuropathy have specific needs for diseases and concerns related to how footwear affects balance. |

B | 3B |

| Healy A, Naemi R, Chockalingam N., 2014, EUA [25] |

R = Majority of the identified studies were randomized control trials which compared the ulcer healing rates of different footwear and other removable off-loading device interventions. C = Appears that the currently available therapeutic footwear were the least effective, followed by sock or jump shoes. |

A | 1A |

| Arts ML et al., 2012, EUA [26] |

R = Mean in-shoe peak pressures ranged between 211 and 308 kPa in feet with forefoot deformity (vs. 191–222 kPa in non-deformed feet) and between 140 and 187 kPa in feet with midfoot deformity (vs. 112 kPa in non-deformed feet). C = Together with the large inter-subject variability in pressure outcomes, this emphasizes the need for evidence-based prescription and evaluation procedures to assure adequate offloading. |

A | 1B |

| Lázaro-Martínez JL et al., 2014, Espanha [27] |

R = Footwear and insoles have been recommended as effective therapies that prevent the development of new ulcers; however, the majority of studies have analyzed their effects in terms of reducing peak plantar pressure rather than ulcer relapse. C = Although several therapies have been described for preventing foot ulcers, the rates of reulcerations are very high. |

B | 3B |

| Waaijman R et al., 2012, EUA [28] |

R = Lowered pressures were maintained or further reduced over time and were significantly lower, by 24–28%, compared with pressures in the control group. C = The offloading capacity of custom-made footwear for high-risk patients can be effectively improved and preserved using in-shoe plantar pressure analysis as guidance tool for footwear modification. |

A | 1B |

| Pataky Z et al., 2016, França [29] |

R = Describes the concept of intelligent footwear we developed, based on continuous measurements and permanent and automatic adaptations of the shoe insole’s rigidity. C = Due to the complexity of their use, the available foot discharge devices are underutilized by both healthcare professionals and patients with very low therapeutic adherence. |

D | 5 |

| Bus SA et al., 2016, Reino Unido [30] |

R = Study demonstrates to relief plantar pressure and is worn by the patient, in the prevention of plantar foot ulcer recurrence. C = Sufficient evidence of good quality supports the use of non-removable offloading to heal plantar neuropathic forefoot ulcers and therapeutic footwear with demonstrated pressure relief that is worn by the patient to prevent plantar foot ulcer recurrence. |

B | 2A |

| Elraiyah T et al., 2016, Minnesota [31] |

R = Although based on low quality evidence (ie, evidence to ensure less certainty), the benefits are demonstrated for the use of total contact casting and irremovable cast walkers in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. C = Reduced relapse rate is demonstrated with various therapeutic footwear and insoles compared to regular footwear. |

B | 2A |

| Arts ML , Bus SA, 2011, EUA [32] |

R = With the exception of deviant outcomes in three forefoot regions for force-time integral, overall 12 steps per foot were required for valid data. C = custom-made therapeutic footwear, provides directions for the use of in-shoe plantar pressure analysis in research and clinical practice in this patient group. |

A | 1B |

| Bus SA, Van Netten JJ, 2016, Amsterdã [33] |

R = After healing of a foot ulcer, the risk of recurrence is high. For the prevention of a recurrent foot ulcer, home monitoring of foot temperature, pressure-relieving therapeutic footwear, and certain surgical interventions prove to be effective. C = These interventions should be investigated for efficacy as a state-of-the-art integrated foot care approach, where attempts are made to assure treatment adherence. |

A | 1B |

| Hingorani Aet al, 2016, EUA [34] |

R = Identified only limited high-quality evidence for many of the critical questions, we used the best available evidence and considered the patients’ values and preferences and the clinical context to develop these guidelines. C = Whereas these guidelines have addressed five key areas in the care of DFUs, they do not cover all the aspects of this complex condition. |

B | 2A |

| Bus SA, 2016, EUA [35] |

R = Studies show a large discrepancy between evidence-based recommendations on offloading and what is used in clinical practice. C = Innovations in plantar pressure and temperature measurements illustrate an important transfer in diabetic foot care from subjective to objective evaluation of the high-risk patient, demonstrate clinical value and a large potential in helping to reduce the patient and economic burden of diabetic foot disease. |

A | 1A |

| Paton J et al., 2016, Reino Unido [36] |

R = The methodological quality of the included studies was poor and no study used a randomized controlled trial (RCT) methodology or follow-up period or tested the intervention within the context of the intended clinical setting. C = There is limited evidence to suggest that footwear and insole devices can artificially alter postural stability and may reduce the step-to-step variability in adults with sensory perception loss. |

B | 2A |

| Schaper NC et al., 2016, Holanda [37] |

R = Healthcare providers should follow a standardized and consistent strategy for evaluating a foot wound, as this will guide further evaluation and therapy. C = Prevent and manage foot problems in diabetes depend upon a well-organized team, using a holistic approach in which the ulcer is seen as a sign of multi-organ disease, and integrating the various disciplines involved. |

B | 3A |

| Dy SM et al., 2017, EUA [38] |

R = Glycemic control (moderate), treatment options, specific types of therapeutic footwear (moderate), integrated foot care (low), home monitoring of foot skin temperature specific types of surgical interventions (low). C = For the prevention of complications, intensive glycemic control is more effective than the standard control for amputation prevention, and home monitoring of skin temperature, footwear, and integrated interventions are effective in preventing the incidence and / or recurrence of ulcers on the feet. |

B | 2A |

| Oliveira AF, De Marchi ACB, Leguisamo CP, 2016, Brasil [9] |

R = The use of diabetic footwear promoted a reduction in the mean of plantar pressure peaks of 22% in the static analysis, and 31% in the dynamic analysis. C = Diabetic footwear was able to produce significant reductions in plantar pressure peaks, being more efficient than ordinary footwear. This effect may contribute to the prevention of injuries associated with diabetic foot. |

A | 1B |

| Padilha AP et al., 2018, Brasil [39] |

R = The existing literature and consultation with the participants subsidized the preparation of the contents of the manual. C = The method enabled the construction of the manual that resulted in a nursing product for use in health education for the care of the person with diabetes with diabetic foot. |

B | 2A |

| N.Even, 2016, Espanha [40] |

R = Prevention of six sessions and annual monitoring of the degree of diabetic foot 3, provides methods to accompany or accompany patients and orthopedic pre-positioned orthopedic (orthopedics, orthopedic orthopedics and plantar orthopedics). C = The evaluation, correction and adjustments of these orthopedic appliances should be systematic in each consultation. |

A | 1B |

| Lewis J, Lipp A, 2013, Reino Unido [41] |

R = Excessive pressure buildup on the soles of the feet is one of the reasons that leads to the formation of wounds in the feet of diabetics. C = Non-removable, pressure-relieving casts are more effective in healing diabetes related plantar foot ulcers than removable casts, or dressings alone. Non-removable devices, when combined with Achilles tendon lengthening were more successful in one forefoot ulcer study than the use of a non-removable cast alone. |

A | 1A |

| Chen WM, Lee SJ, Lee PV, 2015, Austrália [42] |

R = The unsuccessful outcome due to a distally positioned MP can be attributed to the way it interacts with the plantar tissue (eg, plantar fascia) adjacent to the MTH. C = The designated functions of an insole design can be best achieved when the insole is too thick, and when the MP can achieve a uniform pattern of tissue compression adjacent to the MTH. |

A | 1C |

| Bus A et al., 2008, Amisterdã [17] |

R = This systematic review provides support for the use of non-removable materials to cure foot ulcers. C = More high-quality studies are urgently needed to confirm the promising effects found in controlled and uncontrolled shoe studies and interventions designed to prevent ulcers, cure ulcers or reduce pressure. |

A | 1A |

| Jaap J. van Netten et al., 2018, Austrália [43] |

R = Health professionals who manage people with diabetes should be aware of the 10 recommendations regarding therapeutic footwear. C = This guideline contains 10 key recommendations to guide health professionals in selecting the most appropriate footwear to meet the specific foot risk needs of an individual with diabetes. |

A | 1A |

| Sicco A. et al., 2011, Reino Unido |

R = Plantar pressure analysis in the shoe is an effective and efficient tool to evaluate and guide footwear modifications that significantly reduce the pressure in neuropathic diabetic foot. C = This result provides an objective approach to instantly improve footwear quality, which should reduce the risk for pressure-related plantar foot ulcers. |

B | 2B |

| Paton JS et al. 2014, Reino Unido [45] |

R = Four overlapping themes that interact to regulate footwear choice emerged from the analyses: Self-perception dilemma; Reflective adaption; Adherence response and Reality appraisal. C = For people living at risk of diabetic neuropathic foot ulceration, the decision whether or not to wear therapeutic footwear is driven by the individual ‘here and now’, risks and benefits, of footwearchoice on emotional and physical well-being for a given social context. |

A | 1B |

| Lavery LA et al., 2012, EUA [46] |

R = The standard therapy group was about 3.5 times more likely to develop an ulcer compared with shear-reducing insole group (hazard ratio, 3.47; 95% confidence interval, 0.96–12.67). C = These results suggest that a shear-reducing insole is more effective than traditional insoles to prevent foot ulcers in high-risk persons with diabetes. |

B | 2B |

Legend: R = Results; C=Conclusion

The articles of this review presented recommendation grades A, B and D, and of these 13 had recommendation grade A, 12 recommendation B and 1 recommendation D. Of the articles with recommendation grade A, 5 had evidence level 1A (systematic review of randomized controlled trial), 7 level of evidence 1B (controlled clinical trial randomized with narrow confidence interval) and 1C (therapeutic results).

Of the 12 articles that presented grade of recommendation B, 6 were of level of evidence 2A (systematic review of cohort study), 2 with evidence 2B (cohort study), 1 level of evidence 2C (observation of therapeutic resources), 1 of level 3A (systematic review of case control study) and 2 of evidence 3B (case control study). Only 1 article was characterized with degree of recommendation D and level of evidence 5.

After summarizing the surveys included in this review, three main themes were identified: adherence to the use of footwear; changes in balance and biomechanics and difficulty in evaluating the effectiveness of the intervention.

Of the 26 articles included, 10 (38.5%) referred to adherence to the use of footwear, 10 (38.5%) the difficulty to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention and 6 (23.0%) to changes in the balance and biomechanics.

The axis adherence to the use of footwear is evidenced in 03 transversal studies that identified low and moderate adhesion, 02 clinical studies that demonstrated high adhesion, 03 systematic reviews that revealed moderate and high adhesion, 01 descriptive study that considered the adhesion to footwear as low and 01 a phenomenological study that identified moderate adherence to the use of footwear.

The descriptive study that considered adherence to therapeutic footwear as low, analyzed the sensitivity and effects of geometric variations of the therapeutic insole in terms of thickness, placement of the relief element in the peak of pressure of the metatarsals and states of tension / deformation within several tissues of the forefoot, not taking into account the other specificities necessary in relation to the manufacture of therapeutic insoles.

The studies that considered adherence as low to moderate, referred only to the perceived benefit of the footwear by the user, without taking into account other variables. On the other hand, the studies that considered moderate to high adherence suggest that the analysis of plantar pressure in footwear is an effective and efficient tool to evaluate and guide the modifications of the foot and that significantly reduce the pressure in diabetic neuropathic foot.

Regarding the axis changes in balance and biomechanics, it was composed of 06 articles being 03 systematic reviews, 01 clinical trial, 01 qualitative study and 01 cross-sectional study. In these, the main results suggest that the evaluation of the biomechanical alterations allows to identify modifications of the position of the foot, and therefore to examine the structure of the foot and to register the plantar pressure could help in the creation of insoles and footwear. However, there is limited evidence to suggest that footwear and insoles devices can alter postural stability and reduce step-by-step variability in adults with loss of sensory perception.

In the difficulty axis to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention, we identified 06 systematic reviews, 02 clinical trial, 1 randomized control study and 1 narrative review. All were unanimous that more high-quality studies are urgently needed to confirm the promising effects found in controlled and uncontrolled shoe studies and interventions designed to prevent ulcers, cure ulcers, or reduce pressure, and none of them showed a treatment effect statistically intervention.

Discussion

Among the studies included in this review, it was identified that the use of therapeutic footwear is linked to a decrease in the risk of ulceration or its recurrence in people with diabetes who already have diabetic neuropathy as a chronic complication of the disease, according to Arts et al. [26].

The measurement of plantar pressure has been used in research and clinical practice, bringing reliable and valid data and being an optimization factor to avoid the recurrence of ulcers, since the plantar pressure analysis allows the production of shoes tailored for patients with diabetes, which can improve and preserve the discharge of weight in the feet [28, 32, 40].

Predictive values of peak plantar pressure above 200 kPa have the potential to cause biomechanical deformities in the feet, so Lavery et al. [46] suggest that a plantar pressure-reducing insole is more effective than traditional insoles to prevent foot ulcers in people with diabetes .

Research indicates shoes and insoles as effective therapies to prevent the development of new ulcers, although varying the properties of the insole material does not significantly affect static balance or gait. In addition, biomechanical changes, education and patient evaluations should be taken into account for a better therapeutic success, aiding in the prescription of appropriate footwear, insoles and design [27, 42].

The experience of patients at risk of ulceration was reported in an interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA), where Paton et al. [45] addressed people who are at risk of diabetic foot ulceration, for whom the decision to use therapeutic footwear is driven by the risks and from the choice of footwear within the scope of emotional and physical well-being to a certain social activity.

The incidence of diabetic foot ulcerations and lower limb amputations remains very high and unacceptable. The high risk of ulceration and consequent amputation is strongly related to difficulties in obtaining appropriate devices to prevent and / or cure them, especially in the long term. Due to the complexity of their use, the available weight-bearing devices are underutilized by healthcare professionals and patients with very low therapeutic adherence, requiring the development of “smart” footwear based on continuous measurements and permanent and automatic foot adaptations and insole [29].

According to Paton et al. [24], in another study, the type of footwear used by people with diabetes and neuropathy influences the balance that may lead to falls due to the presence of somatosensory deficit. Clinical relevance is increased as therapeutic footwear is often provided to people with diabetes to reduce the risk of foot ulcers and not aiming for balance.

Thus, a critical evaluation of the feet and qualification of health professionals in this theme is fundamental [25, 30, 31, 33–39, 41]. The education and morphological composition of patients should be taken into account to improve therapeutic success as people with diabetic neuropathy have specific needs and concerns related to how footwear affects their balance [43, 47, 48]. Thus, involvement with patients to address these needs and concerns is critical to improving the viability and acceptability of therapeutic footwear to reduce the risk of foot ulcers and increase confidence in balance and improve biomechanical changes already in place [23].

The limitations of this study are related to the methodological issues presented in the articles found, since offloading techniques and the use of therapeutic footwear are commonly used in clinical practice for the prevention and treatment of foot ulcers in people with diabetes, but the evidence base for supporting this use is not well known among clinical studies, being more explicit only in the systematic reviews of the literature.

Conclusion

Through this review it was possible to identify that the decision to use therapeutic footwear is often related to the emotional well-being and to the social context, not being made by the industrial market a designer that is favorable to the users.

Therapeutic footwear for diabetics was able to produce significant reductions in plantar pressure peak in static and dynamic analysis, being more efficient than a common footwear. This effect may contribute to the prevention of injuries associated with diabetic foot. Plantar pressure-reducing inserts were more effective than traditional insoles to prevent foot ulcers in high-risk people.

Health professionals who manage people with diabetes need to be empowered and oriented to choose the most appropriate indication for the specific needs of each person and foot. We hope that with this review, international and national guidelines can be used to ensure that all people with diabetes have access to quality care and assessment and to the provision of appropriate footwear to meet their needs, as this should improve the practice of using footwear and reduce the burden of diabetic foot disease for people and states.

The development of studies to delimit the best instruments of evaluation with high predictive values, specificity, sensitivity and reliability are crucial points for a good evolution of the clinical study. Future research could protocol the best instruments to be used in clinical trials in the health area in order to facilitate and contribute to treatments in these various areas.

Acknowledgements

To the National Council of Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for fomenting the research process 433478 / 2018-7.

Abbreviations

- COCHRANE

Cochrane Library

- DECS

Health Sciences Descriptores

- DM

Diabetes Mellitus

- IDF

Internacional Diabetes Foot Consensus

- IPA

Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis

- JBI

Joanna Briggs Institute

- MESH

Medical Subject Headings Section

- NDP

Peripheral Diabetic Neuropathy

- NHMRC

National health Medical Research Council

- PICU

Patient, intervention, comparison and outcomes

- PUBMED

National Library of Medicine of the USA

- UNIFESP

University of São Paulo

Funding

To the National Council of Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for fomenting the research process 433478 / 2018–7.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

STATEMENTS

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Dear Editor,

We hereby submit our manuscript entitled “EVALUATION OF THE USE OF THERAPEUTIC FOOTWEAR IN PEOPLE WITH DIABETES MELLITUS” with a view for publication in Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders.

This paper reports unpublished data and is not under consideration for publication in other journals. All authors have approved the submission of manuscript to this journal.

With our best regards,

Juliana Vallim Jorgetto

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL

Dear Editor,

The sets of data used and / or analyzed during manuscript entitled “EVALUATION OF THE USE OF THERAPEUTIC FOOTWEAR IN PEOPLE WITH DIABETES MELLITUS” the are available from the corresponding author on prior request.

With our best regards,

Juliana Vallim Jorgetto

COMPETING INTERESTS

Dear Editor,

The authors of the manuscript entitled "EVALUATION OF THE USE OF THERAPEUTIC FOOTWEAR IN PEOPLE WITH DIABETES MELLITUS" do not have conflicts of financial interest, personal or institutional relationships, referring to the theme or data presented in the manuscript and the financial support received for the research. Were duly mentioned in the manuscript.

With our best regards,

Juliana Vallim Jorgetto

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

Dear Editor,

We hereby submit our manuscript entitled “EVALUATION OF THE USE OF THERAPEUTIC FOOTWEAR IN PEOPLE WITH DIABETES MELLITUS” with a view for publication in Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders.

The JVJ authors performed the research, analyzed and interpreted the data presented as well as the final writing and MAG and DMK conducted the review of all data and writing the manuscript.

With our best regards,

Juliana Vallim Jorgetto

References

- 1.Andreassen CS, Jakobsen J, Andersen H. Muscle weakness: a progressive late complication in diabetic distal symmetric polyneuropathy. Diabetes. 2006;55(3):806–812. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.03.06.db05-1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruce DG, Davis WA, Davis TM. Longitudinal predictors of reduced mobility and physical disability in patients with type 2 diabetes: the Fremantle diabetes study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(10):2441–2447. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.10.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbott CA, et al. Multicenter study of the incidence of and predictive risk factors for diabetic neuropathic foot ulceration. Diabetes Care. 1998;7:1071–1075. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.7.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghanassia E, Villon L, Thuan dit Dieudonne JF, Boegner C, Avignon A, Sultan A. Long-term outcome and disability of diabetic patients hospitalized for diabetic foot ulcers: a 6.5-year follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(7):1288–1292. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulton AJ. The diabetic foot: grand overview, epidemiology and pathogenesis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24(Suppl 1):S3–S6. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giacomozzi C, D'Ambrogi E, Cesinaro S, Macellari V, Uccioli L. Muscle performance and ankle joint mobility in long-term patients with diabetes. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:99. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavery LA, Peters EJ, Armstrong DG. What are the most effective interventions in preventing diabetic foot ulcers? Int Wound J. 2008;5(3):425–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2007.00378.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bacarin TA, Sacco IC, Hennig EM. Plantar pressure distribution patterns during gait in diabetic neuropathy patients with a history of foot ulcers. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2009;64(2):113–120. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322009000200008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gershater MA, Löndahl M, Nyberg P, Larsson J, Thörne J, Eneroth M, Apelqvist J. Complexity of factors related to outcome of neuropathic and neuroischaemic/ischaemic diabetic foot ulcers: a cohort study. Diabetologia. 2009;52(3):398–407. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1226-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rizzo L, Tedeschi A, Fallani E, Coppelli A, Vallini V, Iacopi E, Piaggesi A. Custom-made orthesis and shoes in a structured follow-up program reduces the incidence of neuropathic ulcers in high-risk diabetic foot patients. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2012;11:59–64. doi: 10.1177/1534734612438729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pham H, et al. Screening techniques to identify people at high risk for diabetic foot ulceration - a prospective multicenter trial. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:606–611. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.5.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Netten JJ, et al. Diabetic foot Australia guideline on footwear for people with diabetes. J Foot Ankle Res. 2018;11:2. doi: 10.1186/s13047-017-0244-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Guideline . National evidence-based guideline on prevention, identification and management of foot complications in diabetes (Part of the guidelines on management of type 2 diabetes) Melbourne: Baker IDI Heart & Diabetes Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.International Diabetes Federation (IDF). International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot Prevention and Management of Foot Problems in Diabetes Guidance Documents and Recommendations; 2017.

- 15.International Diabetes Federation (IDF). International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot Prevention and Management of Foot Problems in Diabetes Guidance Documents and Recommendations; 2015.

- 16.Cisneros Lígia L. Avaliação de um programa para prevenção de úlceras neuropáticas em portadores de diabetes. Revista Brasileira de Fisioterapia. 2010;14(1):31–37. doi: 10.1590/S1413-35552010000100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bus SA, Valk GD, van Deursen RW, Armstrong DG, Caravaggi C, Hlaváček P, Bakker K, Cavanagh PR. The effectiveness of footwear and offloading interventions to prevent and heal foot ulcers and reduce plantar pressure in diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24(Suppl 1):S162–S180. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bus SA, Waaijman R, Arts M, de Haart M, Busch-Westbroek T, van Baal J, Nollet F. Effect of custom-made footwear on foot ulcer recurrence in diabetes a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:4109–4116. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendes KDS, Silveira RCCP, Galvão CM. Revisão integrativa: método de pesquisa para a incorporação de evidências na saúde e na enfermagem. Texto Contexto Enferm, Florianópolis. Out-Dez. 2008;17(4):758–764. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beyea S, Nicoll LH. Writing an integrative review. AORN J. 1998;67(4):877–880. doi: 10.1016/S0001-2092(06)62653-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whittemore R, Knal K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2011 edition. Available from: http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/ReviewersManual-2011.pdf. Accessed 13 May 2019.

- 23.Mark LJ, et al. Perceived usability and use of custom-made footwear in diabetic patients at high risk for foot ulceration. J Rehabil Med. 2014;46:357–362. doi: 10.2340/16501977-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paton JS, Roberts A, Bruce GK, Marsden J. Does footwear affect balance? The views and experiences of people with diabetes and neuropathy who have fallen. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2013;103(6):508–515. doi: 10.7547/1030508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Healy A, Naemi R, Chockalingam N. The effectiveness of footwear and other removable off-loading devices in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: a systematic review. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2014;10(4):215–230. doi: 10.2174/1573399810666140918121438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arts ML, et al. Offloading effect of therapeutic footwear in patients with diabetic neuropathy at high risk for plantar foot ulceration. Diabet Med. 2012;29(12):1534–1541. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lázaro-Martínez JL, Aragón-Sánchez J, Álvaro-Afonso FJ, García-Morales E, García-Álvarez Y, Molines-Barroso RJ. The best way to reduce reulcerations: if you understand biomechanics of the diabetic foot, you can do it. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2014;13(4):294–319. doi: 10.1177/1534734614549417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waaijman R, et al. Pressure-reduction and preservation in custom-made footwear of patients with diabetes and a history of plantar ulceration. Diabet med. 2012. Dec. 2012;29(12):1542–1549. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pataky Z, et al. Intelligent footwear for diabetic. Rev Med Suisse. 2016;12(502):143–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bus SA, Armstrong DG, van Deursen RW, Lewis JEA, Caravaggi CF, Cavanagh PR, on behalf of the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF) IWGDF guidance on footwear and offloading interventions to prevent and heal foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32(Suppl. 1):25–36. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elraiyah T, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of off-loading methods for diabetic foot ulcers. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63(2 Suppl):59S–68S.e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arts ML, Bus SA. Twelve steps per foot are recommended for valid and reliable in-shoe plantar pressure data in neuropathic diabetic patients wearing custom made footwear. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2011;26(8):880–884. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bus SA, van Netten JJ. A shift in priority in diabetic foot care and research: 75% of foot ulcers are preventable. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32(Suppl. 1):195–200. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hingorani A, LaMuraglia GM, Henke P, Meissner MH, Loretz L, Zinszer KM, Driver VR, Frykberg R, Carman TL, Marston W, Mills JL, Sr, Murad MH. The management of diabetic foot: a clinical practice guideline by the Society for Vascular Surgery in collaboration with the American podiatric medical association and the Society for Vascular Medicine. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63(2 Suppl):3S–21S. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bus SA. The role of pressure offloading on diabetic foot ulcer healing and prevention of recurrence. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(3 Suppl):179S–187S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paton SJ, et al. Effects of foot and ankle devices on balance, gait and falls in adults with sensory perception loss: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016;14(12):127–162. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schaper NC et al. Prevention and management of foot problems in diabetes: a Summary Guidance for Daily Practice 2015, based on the IWGDF Guidance documents. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews32,(S1) Supplement Article, 2015.

- 38.Dy SM et al. Preventing complications and treating symptoms of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. 2017 Mar. report no.: 17-EHC005-EF. AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. [PubMed]

- 39.Padilha AP et al. Manual de cuidados às pessoas com diabetes e pé diabético: Construção por SCOPING STUDY. Texto Contexto Enferm. 26 (4) Florianópolis. 2018.

- 40.Even N. Tratamiento de las ulceraciones diabéticas en la consulta del pedicuro-podólogo, acompañamiento y prevención. EMC – Podologia. 2016;18(3):1–10. doi: 10.1016/S1762-827X(16)77504-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lewis J, Lipp A. Pressure-relieving interventions for treating diabetic foot ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD002302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Chen WM, Lee SJ, Lee PV. Plantar pressure relief under the metatarsal heads: therapeutic insole design using three-dimensional finite element model of the foot. J Biomech. 2015;48(4):659–665. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Netten JJ, et al. Diabetic Foot Australia guideline on footwear for people with diabetes. Journal of Foot and Ankle Research. 2018;11:2. doi: 10.1186/s13047-017-0244-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sicco A. et al. Evaluation and optimization of therapeutic footwear for neuropatic diabetic foot patients using in-shoe plantar pressure analysis. Diabetes Care (2001);34(7):1595–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Paton JS, Roberts A, Bruce GK, Marsden J. Patients' experience of therapeutic footwear whilst living at risk of neuropathic diabetic foot ulceration: an interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) J Foot Ankle Res. 2014;7(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1757-1146-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lavery LA, LaFontaine J, Higgins KR, Lanctot DR, Constantinides G. Shear-reducing insoles to prevent foot ulceration in high-risk diabetic patients. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2012;25(11):519–524. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000422625.17407.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valk GD, Kriegsman DM, Assendelft WJ. Patient education for preventing diabetic foot ulceration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;25(1):CD001488. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001488.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lott DJ, et al. Effect of footwear and orthotic devices on stress reduction and soft tissue strain of the neuropathic foot. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2007;22(3):352–359. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]