Abstract

Background

Diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) is one the serious disabling conditions in patients with diabetes. Several approaches are available to manage DFU including Negative Pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT). The objective of this overview is systematically reviewing the related reviews about the effectiveness, safety, and cost benefits of NPWT interventions.

Methods

In October 2018, electronic databases including Medline, Embase, Scopous, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library and Google scholar were searched for systematic reviews about the NPWT’s effectiveness and safety in DFUs. The Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews 2 (AMSTAR2) checklist was used for the appraisal of the systematic reviews. According to this checklist the studies were categorized as high, moderate, low and critically low quality.

Results

The electronic searches yielded 6889 studies. After excluding duplicates and those not fellfield the inclusion criteria, 23 systematic reviews were considered. The sample size of the reviews ranged between 20 and 2800 patients published since 2004 to 2018. Twenty systematic reviews (86.95%) included only randomized clinical trials (RCT). Regarding the AMSTAR-2 checklist, 7 studies were assigned to high quality, 8 were categorized as low quality and 8 studies belonged to the critically low quality groups. Accordingly, three, two and one out of seven high quality studies approved the effectiveness, safety and cost benefit of the NPWT therapy, respectively. However, some of them declared that there is some flaws in RCTs designing.

Conclusion

This overview illustrated that either systematic reviews or the included RCTs had wide variety of quality and heterogeneity in order to provide high level of evidence. Hence, well-designed RCTs as well as meta-analysis are required to shade the light on different aspects of NPWT.

Keywords: Diabetic foot ulcer, Negative pressure wound therapy, Systematic review

Introduction

In 2013, about 382 million people had diabetes mellitus (DM), and it is projected that 592 million people would be affected by 2035 [1]. The high prevalence of diabetes would be resulted in the enhancement of the risk of foot problems, the most debilitating complication of DM, predominantly due to neuropathy and/or peripheral arterial disease [2, 3]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) and to the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF) [4], diabetic foot is described as a condition in which the foot of a patient with diabetes has a potential risk of pathologic consequences, including ulceration, infection and/or destruction of the deep tissues, associated with neurological abnormalities and various grades of peripheral arterial disease and metabolic complications of diabetes in the lower limb.

It is estimated that 15% of all patients with DM have had or will have diabetic foot ulcers (DFU) in their life time [5]. Whenever ulceration happens, healing is difficult. Furthermore, it is believed that every 20 s, a lower limb is amputated due to diabetes in the world [6]. Accordingly, researchers have been encouraged to find the best modalities for DFU management. Serious consideration should be paid to this issue by the foot care team. Multidisciplinary team approach can reduce the incidence of first ulcer, infection, the necessity and duration for hospitalization, as well as the frequency of major limb amputation [7]. The main approaches applied so far for DFU management are ulcer debridement, infection control, and off-loading and basic and advanced wound contact dressings. However, there is little quality evidence to support the use of any single dressing product over another in promoting a moist wound bed for the DFU.

Nowadays, novel modalities come with the help of conventional modalities for accelerating the process of DFU healing. So, Negative Pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT) has been proposed as an adjunctive treatment through several randomized clinical trials for enhanced wound healing process [8]. The NPWT technique is a non-invasive system by placing foam dressing in the wound and uses a negative pressure controlled by a device connected to the vacuum that promotes stimulation and wound healing [9, 10].

However, despite the existing evidence about the use of NPWT in surgical, vascular or other types of wound healing, there are few studies that analyze its effectiveness in DFU.

In some systematic reviews, researchers concur that there is moderate to strong evidence for the use of NPWT in DFUs [11–13] . However, results from some of them have highlighted certain negative aspects related to NPWT [14–16]. The FDA Safety Communication Report, has warned about the potential adverse effects of NPWT including wound maceration, wound infection, bleeding, and retention of dressings [17]. On the other hand; available NPWT systems seem to be expensive, which may preclude their widespread usage. However, if the therapy does accelerate wound healing, considerable reserves could be made in dressing-associated costs [18]. Thus, the objective of this overview is gathering and analyzing the scientific evidence from systematic reviews that evaluate the effectiveness and safety as well as the cost-effectiveness of NPWT in DFUs treatment.

Material and methods

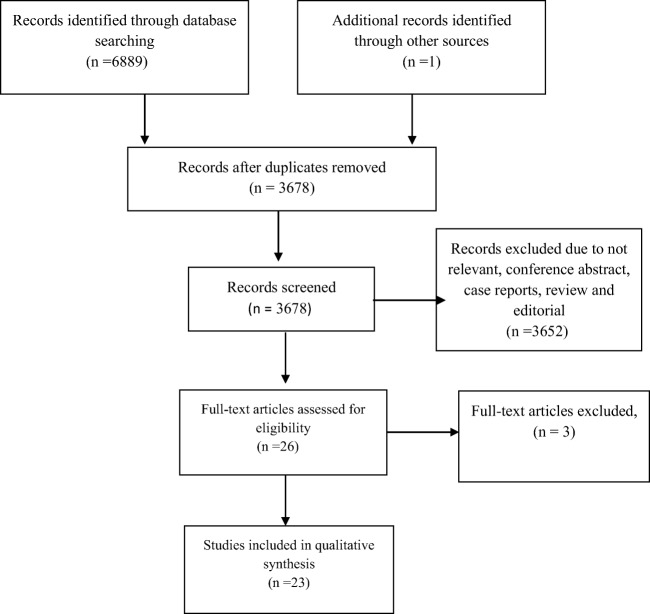

The current study was approved by the ethics committee of the Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Institute (EMRI) affiliates to Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS) with the ethical code ≠ IR.TUMS.EMRI.REC.1395.00142. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart defines the selection process of the included studies in this review (Diagram 1). [19]

Search strategy

In October 2018, the systematic search was conducted in MEDLINE (via PubMed), SCOPUS, Web of Science, the Cochrane library and Embase between January 1996 and August 2018 (when modern NPWT setups, commercially accessible, were widely used in the management of complex wounds in both inpatient and outpatient care settings). The search strategy was based on predefined search terms including “Negative-Pressure Wound Therapy” (NPWT) and “ulcer”.

The keywords and medical subject headings, using the following Boolean operators were: (((“Negative-Pressure Wound Therapy” OR (Negative AND Pressure*) OR VACUUM OR Vacuum OR VAC) AND (therap* OR treat* OR Healing* OR “Wound Healing” OR Therapeutics OR polytherapy OR somatotherap OR granulation) AND (Wound* OR Ulcer* OR “Wounds and Injuries” OR Wound* OR “Wound Healing” OR Topical OR injur* OR lesion OR sore OR vulnus OR ulcus OR reinjury) AND (review* OR systematic OR Review OR “Review Literature as Topic”) NOT ((Animals OR animal* OR rat OR rats) AND (Humans OR human*))).

The search results from the so called databases were imported in to EndNote X7 and duplicates were removed by the software and manually. We also investigated google scholar and screened the reference lists of primary included systematic reviews to find the other eligible studies.

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

Studies that had searched more than one database and had accompanied a critical analysis of their included studies were considered to be systematic reviews, and the methodology designated by Smith et al. were practiced for this overview of systematic reviews [20]. We included systematic reviews and meta-analyses which evaluated the effect of any brand of NPWT in subjects with DFU (either post-surgical debridement/amputation or non-surgical). Moreover, studies in patients suffering from DFU constituted a part of the total population were only included if the subgroup analysis of diabetic patients were distinctly discussed. The summary of inclusion criteria are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria of systematic reviews (PICO)

| Population | Diabetic patients >18 years with foot ulcer |

| Intervention | Negative pressure wound therapy |

| Comparator | Any conventional wound dressing for diabetic ulcers |

| Outcome |

Primary outcome: complete wound healing (healing time, change in ulcer size, granulation tissue formation) Secondary outcome: adverse events (e.g. infection, pain), and cost-effectiveness |

Therefore, articles of any language and study setting, identified via English titles and abstracts were considered for inclusion criteria of the study. If a review was an update of a previous review, the latest updates was considered. Narrative reviews, case reports, animal studies and conference abstracts were excluded.

Study selection and data extraction

First of all, 4 independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of all studies identified through database searches. They excluded articles if they did not mention about NPWT or its similar terminology used in search strategy. The full text of the remaining article was then reviewed.

In order to extract data from the selected studies, characteristics of each included systematic review were independently reviewed by 4 so called authors. For this purpose a template was designed and all relevant features were recorded. (Data are presented in Table 2).

Table 2.

Charactristics of included systematic reviews

| No | Author/Date Country | databases searched | Objective | Type of intervention | Included Population | Number of included studies and Study designs | Method of risk of bias/quality assessment | outcomes reported in the review | Authors conclusion | Study rating | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy | safety | cost | ||||||||||

| 1 | Samson D./ Spain 2004 [23] | 3(medline/embase/cochrane) | “to systematically review and synthesize the available evidence on the effectiveness of vacuum-assisted closure(VAC) for wound healing” | VAC vs. moist gauze dressings | 20 people with diabetic foot ulcer | 2 RCT [41, 42] | Harris rating system [43] | Change in wound area, incidence of complete wound closure, time to complete closure, adverse events | Inconclusive | N/A | N/A | High |

|

There was not any significant advantage with regard to VAC therapy. However the evidence from the RCTs were poor | ||||||||||||

| 2 | Pham C. / Australia 2006 [24] | 3(medline/embase/cochrane) | “To review the efficacy and safety outcomes of topical negative pressure(TNP) in treating particular wound types” | TNP vs. conventional method | 51 people with diabetic foot ulcer | 2RCT and 1 case series [41, 42, 44] | N/R | Wound closure, adverse events | Inconclusive | Inconclusive | N/A | Critically Low |

| There is a lack of high-quality reports with sufficient sample sizes to detect any differences between NPWT and conventional method | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Noble-Bell G, et.al UK 2008 [16] | 4(the Cochrane register of controlled trials, Medline, Embase and CINHAL, | To systematically review the evidence relating to the effectiveness of NPWT in the management of diabetes foot ulcers | NPWT vs. conventional dressings | 206 either type1 or type 2diabetic Patients with, chronic or acute wounds, including postoperative wounds | 4 RCT [41, 42, 45, 46] | JADAD criteria | time to wound healing, Treatment related complications, cost-effectiveness | Beneficial | Beneficial | Inconclusive | High |

| Negative-pressure wound therapy may be particularly beneficial for diabetic foot ulcer healing without any major adverse events, however the studies quality were weak to moderate | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Vikatmaa, P., et al. Finland 2008 [13] | 2 (Cochrane, medline) | To gather the most reliable evidence available on the effectiveness and safety of NPWT in the treatment of acute and chronic wounds | NPWT vs. any other local wound therapy | 206 2diabetic Patients with foot ulcer | 4 RCT [41, 42, 45, 46] | Harris rating system [43] | time needed to reepithelialization, Second amputation, wound area, reduction, | Beneficial | Beneficial | N/A | Low |

| NPWT was at least as effective and in some cases more effective than the control treatment., however the quality of studies were poor | ||||||||||||

| 5 | *Gregor S, et al. Germany 2008 [35] | 4(MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Library) | To assess the clinical effectiveness and safety of NPWT vs conventional wound therapy | NPWT vs.conventional wound dressing | 206 patients with diabetic foot amputations or chronic diabetic wounds | 2 RCT, 2 non-RCT [41, 42, 45, 46] | trials were assessed for their quality using IQWiG | Incidence and Time to wound closure, safety | Inconclusive | inconclusive | N/A | High |

| Although there is some indication that NPWT may improve wound healing, the body of evidence available is insufficient to clearly prove an additional clinical benefit of NPWT. The large number of prematurely terminated and unpublished trials is reason for concern. | ||||||||||||

| 6 | Hinchliffe RJ/ UK/ 2008 [25] | 4 (Medline, Embase, the Cochrane database of systematic reviews, and the Cochrane Central Controlled Trials Register | “to identify interventions for which there is evidence of effectiveness” | NPWT efficacy vs. Saline moistened gauze, standard care | 182 people older than 18 with either type 1 or 2 with chronic foot ulcers or post-amputation wounds | 3 RCT [41, 42, 45] | Dutch Cochrane Center (www.cochrane.nl/index.html) | Ulcer healing time to healing, reduction in ulcer area | Beneficial | Beneficial | N/A | Low |

| NPWT therapy have been shown to improve the rate of healing after post-amputation wounds, however further evidence is required to substantiate the benefit and cost–benefit of TNP therapy after post-amputation wounds, as well as in the non-operated chronic wound. | ||||||||||||

| 7 | Ubbink/ netherland2008a [22] | 4(Cinahl, Embase and Medline and the Cochrane controlled trials register | “to summarize up-to-date, high-level evidence on the effectiveness of TNP on wound healing, in both acute and chronic settings” | TNP effectiveness vs. Saline moistened gauze | 206 diabetic patients | 4 RCT [41, 42, 45, 46] | Dutch Cochrane Collaboration checklist (www.cochrane.nl). | wound healing adverse events | Inconclusive | N/A | N/A | Low |

| There is no valuable evidence to support the use of TNP in the treatment of chronic wounds, when compared to MGWD or other topical wounds dressing. | ||||||||||||

| 8 | Ubbink DT, Netherlands, 2008b [26] | 4(Ovid EMBASE, Ovid CINAHL, The Cochrane Library, Ovid MEDLINE) | To determine: if TNP is more effective than alternative wound dressings in terms of healing rates, costs, quality of life, pain management and comfort for people with chronic wounds | effects of TNP vs. | 20 people with chronic diabetic foot ulcer | 2RCT [41, 42] | Dutch Cochrane Collaboration checklis | Time to complete healing, Rate of change in wound area, Proportion of wounds completely healed, Adverse events., Costs | Inconclusive | N/A | N/A | High |

| There are methodological flaws regarding with trials comparing TNP with alternative treatments in chronic wounds. Although data demonstrate a beneficial effect of TNP on wound healing, more better quality research is needed. | ||||||||||||

| 9 | Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series, Canada, 2010 [27] | 5(PubMed, Embase, CINAHL,the Cochrane Library INAHT) | to review the NPWT technique regarding efficacy and safety in the management of skin ulcers | NPWT vs. moist wound therapy or AMWT | 504 people who had diabetic ulcer and amputation wounds | 2RCT [8, 46] | Pedro Scale | complete wound closure, Granulation tissue formation, time to granulation tissue formation, rate of secondary amputation and other adverse events, cost-effectiveness | Beneficial | N/A | Inconclusive | High |

|

Time to complete healing was significantly shorter in NPWT groups vs. controls Proportion of patients who achieved complete ulcer closure in NPWT was significantly greater than in controls in both studies | ||||||||||||

| 10 | Xie X. et al./Canada/ 2010 [12] | 2 (PubMed and Embase,) | to estimate the efficacy of negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) | NPWT compared to any standardwound dressing | 580 people who had diabetic ulcer | 7RCT [8, 41, 42, 45–48] | PEDro Scale | rate of wound healing | Beneficial | N/A | N/A | Critical low |

| There is now sufficient evidence to show that NPWT will accelerate healing of diabetes-associated chronic lower extremity wounds. | ||||||||||||

| 11 | C.A. Fries, et al. United Kingdom 2011 [28] | 5(Cinahl, Embase, Medline, ProQuest and the Cochrane Library) | to conduct a review of the evidence supporting the effectiveness use of TNP in trauma patients | N/A | 206 Patients with diabetic foot ulcers | 4 RCT [41, 42, 45, 46] | N/R | Rate of time healing, rate of complete closure, wound depth | Beneficial | N/A | N/A | Critical low |

| All trials suggest that wound healing rates and reduction of wound surface area is improved by TNP | ||||||||||||

| 12 | F.L. game / / UK 2012 [11] | 3(Medline, Embase, clinical trials registries) | N/A | NPWT vs. standard wound care | chronic foot ulcers in diabetic people older than 18 with either type 1 or 2 | 3 RCT included 375diabetic foot patients and 1 cohort included 16,319 diabetic foot patients [8, 47–49] |

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network criteria. |

Wound healing, time to healing, reduction in ulcer area or amputation | Beneficial | Beneficial | N/A | Low |

| Weakly significant benefit of NPWT in reduced healing time, increased incidence of healing and reduced risk of minor amputation is for diabetic foot ulcers. | ||||||||||||

| 13 | Yarwood L UK, 2012 [29] | 3(CINAHL, MEDLINE and the Cochrane Library | Seeks to review the effectiveness of NPWT and conventional wound_dressings | NPWT vs.conventional wound dressings | 640 people with diabetic foot ulcer | 4 RCT [8, 41, 46, 50] | N/A | Granulation tissue formation, healing time, wound surface area reduction, adverse events, cost | Beneficial | Beneficial | Beneficial | Low |

| NPWT has proven to be more effective than conventional Wound dressings. However further studies are needed evaluating cost-effectiveness and patients accessibility. | ||||||||||||

| 14 | Quecedo L/ Spain/ 2013 [30] | 5(medline, ebbase, NHS, HTAD, chocrane library, Aggressive research website) | to analyze the scientific evidence from clinical trials that evaluate the effectiveness and safety of NPWT in the treatment of diabetic wounds | NPWT vs. conventional therapies | 570 people aged 18 years or affected by complicated foot injuries or postoperative wounds | 6RCT [41, 42, 45, 46, 48, 51] | The Jaddad criteria | healing time, adverse events, costs | Beneficial | Beneficial | Beneficial | Critical low |

| It could be possible to make a recommendation for its use given the safety profile and costs and consistency of the results, in spite of the low quality grade of evidence. | ||||||||||||

| 15 | Greer, N, et al. USA 2013 [14] | 2 (MEDLINE, Cochrane Library) | to systematically evaluate the efficacy and harms of NPWT | NPWT vs. standard care | 342 diabetic patients | 1 RCT [8] |

modifide Cochrane Approach to determining risk of bias [52] |

Percentage of ulcer healed, healing time, adverse events, | Beneficial | N/A | N/A | low |

| This good-quality study found improved healing with NPWT | ||||||||||||

| 16 | Dumville, UK, 2013 [15] | 6(Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register; The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); The Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE),The NHS Economic Evaluation Database,MEDLINE, EMBASE; and EBSCO CINAHL | To assess the effects of NPWT in the healing of foot wounds in people with diabetes mellitus | NPWT vs. standard care or adjuvant therapies | 605 diabetic patients with Type 1 or 2 DM, with foot wounds below the knee, regardless of underlying etiology | 5RCT [8, 46, 50, 53, 54] | Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias | Complete wound healing, amputation adverse events, | Inconclusive | Inconclusive | Inconclusive | High |

| There is some evidence to suggest that NPWT is more effective in healing diabetic post-operative foot wounds compared with moist wound dressing | ||||||||||||

| 17 | Guffani A,USA, 2014 [31] | 2(pubmed, OVID) | to address the effectiveness and safety of NPWT for wound healing in patients with a diabetic foot | NPWT vs. SMWT | 545 diabetic Patients with chronic or acute diabetic foot ulcers | 4 RCT [8, 45, 46, 48] | N/R | wound closure rate, safety and reduction in secondary complications | Beneficial | Beneficial | N/A | Critical low |

| Evidence from 4 randomized controlled trials suggests that NPWT using a VAC system is more effective than Standard Moist Wound Therapy(SMWT) in promoting the healing of diabetic foot wounds and is safe and effective for management of diabetic foot ulcers | ||||||||||||

| 18 | *Zhang, Jian, et al. China 2014 [37] | 3(PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases) | To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of negative-pressure wound therapy for diabetic foot ulcers | NPWT Vs. with standard wound care | 669 diabetic foot patients with any chronic foot wound and postoperative wounds in type 1 or 2patients diabetic | 8 RCT [8, 41, 42, 45, 46, 48, 50, 55] | Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions | ulcer healing, time to ulcer healing, adverse events | Beneficial | Beneficial | N/A | low |

| Negative-pressure wound therapy appears to be more effective for diabetic foot ulcers compared with non–negative-pressure wound therapy, and has a similar safety profile. | ||||||||||||

| 19 | * Wang R/ China/ 2015 [36] | 5(PubMed, Ovid EMBASE and Web of Science, Cochrane library and Chinese biomedicine literatures databases | “To compare the strength and weakness of negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) with ultrasound debridement (UD) as for diabetic foot ulcers (DFU)” | NPWT vs.standard wound care | 2800 Patients with diabetic foot ulcers | 8 RCT [8, 42, 45–48, 50, 55]and **22 compared studies | Modified JADAD criteria | full epithelialization, Time to wound closure, decrement in ulcer area, secondary amputation | Beneficial | Beneficial | N/A | Critical low |

| NPWT significantly improved the proportion of diabetic foot ulcer healing compared with standard wound care | ||||||||||||

| 20 | Peters E.J./ The Netherland/2016 [33] | 2(PubMed, Embase) | To review the effectiveness of NPWT on infection control in diabetic foot ulcers | NPWT vs. advanced wound dressing | 130 people aged 18 years or older who had diabetes and foot infection | 1RCT [56] | Dutch Cochrane Centre | Wound healing, infection control | Inconclusive | Inconclusive | N/A | Critical low |

| There is no sufficient conclusions about the usefulness of the NPWT | ||||||||||||

| 21 | Game, F. L., et al. UK & USA2016 [32] | 2(MEDLINE, Cochrane Library) | to review the NPWT effectiveness in healing of chronic ulcers of the foot in diabetes | NPWT vs. Standard care or advanced wound dressing | 297 chronic foot ulcers in diabetic people older than 18 with either type 1 or 2 | 3 RCT [50, 55, 56] | Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network criteria [57] | healing, time to healing, and/or reduction in ulcer area, cost | Inconclusive | N/A | Inconclusive | Critical low |

| The evidence to support the NPWT effectiveness and cost effectiveness in diabetic foot ulcers is not strong | ||||||||||||

| 22 | *Liu, Si, et al. 2017 China [18] | 5(Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Ovid, and Chinese Biological Medicine databases) | “to assess the clinical efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness of NPWT in the treatment of DFUs” | NPWT vs. standard dressing changes | 1044 Patients with chronic diabetic foot ulcers | 11 RCT [8, 41, 42, 46, 48, 50, 55, 58–61] | Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias | healing time, reduction in ulcer area reduction in ulcer depth,amputations, treatment-related adverse effects, cost-effectiveness | Beneficial | Beneficial | Beneficial | High |

|

All trials suggested that: Higher rate of complete healing, shorter healing time, and fewer amputations. | ||||||||||||

| 23 | Gonzalez-Ruiz, M Spain 2018 [34] Article in spanish | 4(PubMed, CINAHL, SciELO and Web of Science) | To conduct a systematic review for analyze the effectiveness of TNP in ulcers of diabetic patients | TPN Vs.conventional dressing | 967 people with diabetic foot ulcer | 12 RCT [8, 41, 45, 47, 48, 50, 51, 55, 62–65] | JADAD scale | Wound surface area, time to granulation, quality of life cost | Beneficial | Beneficial | Beneficial | low |

| TPN achieve a greater surface of granulation tissue and faster healing time. Even so, future studies are needed to evaluate the impact of TPN with the aim of incorporating it into daily clinical practice. | ||||||||||||

VAC vacuum assisted closure, RCT randomized controlled trial, NPWT negative pressure wound therapy, N/A not aplicable, TNP topical negative pressure, N/R not reported, MGWD moist gauze wound dressing, DFU diabetic foot ulcer, SWC standard wound care

*Meta-analyses

**these studies are not mentioned in this overview

Quality assessment

After retrieving the relevant studies in terms of titles and abstracts, the researchers used’ Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews 2′ (AMSTAR2) [21] measurement tool for the critical appraisal of systematic reviews. AMSTAR2 is a validated measure tool for systematic reviews that comprise randomized or non-randomized studies of healthcare interventions, or both.

For each systematic review, the 16 domains (Box 1) included on the AMSTAR 2 checklist were considered along with the checklist guidelines. The response options for the most domains consisted of “yes” and “no” while some domains contained the third option as “partial yes”. In the present study, the checklist was used as a qualitative rather than quantitative indicator. This process had been completed independently by 4 mentioned reviewers. From 16 domains, 7 of them were critical (items: 2, 4, 7, 9, 11, 13 and 15). The overall quality of each systematic review was rated in the 4 following categories: “High” for no or one non-critical weakness,;“Moderate” for more than one non-critical weakness; “Low” for one critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses and “Critically low” for more than one critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses. [21]

Box 1: AMSTAR2 checklist

|

1. Did the research questions and inclusion criteria for the review include the components of PICO? *2. Did the report of the review contain an explicit statement that the review methods were established prior to the conduct of the review and did the report justify any significant deviations from the protocol? 3. Did the review authors explain their selection of the study designs for inclusion in the review? *4. Did the review authors use a comprehensive literature search strategy? 5. Did the review authors perform study selection in duplicate? 6. Did the review authors perform data extraction in duplicate? *7. Did the review authors provide a list of excluded studies and justify the exclusions? 8. Did the review authors describe the included studies in adequate detail? *9. Did the review authors use a satisfactory technique for assessing the risk of bias (RoB) in individual studies that were included in the review? 10. Did the review authors report on the sources of funding for the studies included in the review? *11. If meta-analysis was performed, did the review authors use appropriate methods for statistical combination of results? 12. If meta-analysis was performed, did the review authors assess the potential impact of RoB in individual studies on the results of the meta-analysis or other evidence synthesis? *13. Did the review authors account for RoB in primary studies when interpreting/discussing the results of the review? 14. Did the review authors provide a satisfactory explanation for, and discussion of, any heterogeneity observed in the results of the review? *15. If they performed quantitative synthesis did the review authors carry out an adequate investigation of publication bias (small study bias) and discuss its likely impact on the results of the review? 16. Did the review authors report any potential sources of conflict of interest, including any funding they received for conducting the review? |

*critical domains

Results

Literature search

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA diagram of literature search and study selection process. The databases search recognized 6889 articles. After excluding duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, 26 full text articles fulfilled the inclusion criteria, 3 of them had been updated later and 23 full text of articles were retrieved for the overview; (see Table 2 for details of included reviews). Among the included articles 19 articles [11–16, 22–34] were systematic reviews and 4 [18, 35–37] were systematic reviews with meta-analysis.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for literature search process for inclusion in overview

Review characteristics

Twelve out of 23 SR/MAs evaluated DFUs specifically while 11 SR/MAs evaluated NPWT treatment in wounds with other etiologies rather than DFUs. Comparators in SRs were standard wound care or advanced moist wound care (included hydrogel, foam, alginate or hydrocolloid dressing). The number range of included studies in each systematic review was between one and thirty studies (Table 3). Twenty systematic reviews (86.95%) included only randomized clinical trials (RCTs). Almost the majority of RCTs had had been included in SRs/MAs except 4 RCT which were only assessed by Liu et al. [18], and 5 RCT were only assessed by Gonzalez-Ruiz et al. [34]. Two observational studies were assessed by Pham C et al. [24] and Game F.L et al. [11] rather than their included RCTs too. All of the 4 M/As used RCTs for analysis except study by Wang R. et al. [36] which also included 22 comparator studies (Tables 3 and 5).

Table 3.

-Summary of included trials/ observational studies in included systematic reviews /meta-analyses

| SRs | MAs | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCTs | Samson,2004 | Pham C, 2006 | Noble-Bell G, 2008 | Vikatmaa, P., 2008 | Hinchliffe RJ. 2008 | Ubbink DT, 2008a | Ubbink DT, 2008b | Health Quality O, 2010 | X. Xie 2010 | C.A. Fries,2011 | Game, F. L.,2012 | Yarwood, 2012 | Quecedo, L, 2013 | Greer N, 2013 | Dumville JC, 2013 | Guffani A, 2014 | Peters E.J, 2016 | Game, F. L. 2016 | Gonzalez-Ruiz, M,2018 | Gregor S, et al.2008 | Zhang J,2014 | *Wang R, 2015 | Liu, Si, 2017 | |

| McCallon et al., [42] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Eginton et al., [41] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Armstrong et al., [46] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||

| Etoz et al., [45] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||

| Akbari et al., [47] | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Blume et al., [8] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||

| Mody et al., [53] | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sepulveda et al., [48] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||||||||||

| Novinscak et al., [54] | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nain et al., [55] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||

| Karatepe et al., [50] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||

| Paola et al. 2010 | √ | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Ravari et al., [60] | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| vaidhya et al., [59] | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| [58] | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sajid et al., [61] | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lavery et al., [64] | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lone et al.[63] | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lavery et al., [62] | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yang et al. [65] | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Apelqvist et al. [51] | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| observational | Armstrong et al., [44] | √ | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Frykberg et al., [49] | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||

SRs systematic reviews, M/As meta-analyses, RCTs randomized controlled trails

*only represent included RCTs

Table 5.

Included meta- analyses results

| SR with MA | Studies included | Variables analyzed | Result | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gregor S, et al. 2008 [35] |

Etoz et al. 2007 [45] Mc Callon, 2000 [42] |

Change in wound size |

SMD(95% CI): −1.3(−2.07 to −0.54) In favor of NPWT |

High |

| Zhang J, et al 2014 [37] |

Armstrong, et al. 2005 [46] Blume et al. 2008 [8] Nain et al.2001 [55] |

Proportion of ulcer healing |

(42.8% vs. 31.96%; rr,1.52; 95% CI, 1.23 to 1.89; p < 0.001) In favor of NPWT |

Low |

|

Eginton et al. 2003 [41] Etoz et al. 2004 [45] Mc Callon et al. 2000 [42] Nain et al.2001 [55] |

Ulcer area reduction |

SMD, 0.89; 95%CI, 0.41to 1.37; p = 0.003 In favor of NPWT |

||

|

Mc Callon et al. 2000 [42] Sepulveda et al. 2009 [48] |

Time to ulcer healing |

(standardized mean difference, −1.10; 95% CI, −1.83 to −0.37; p = 0.003). In favor of NPWT |

||

|

Armstrong et al. 2005 [46] Blume et al. 2008 [8] |

Adverse events, including edema, pain, bleeding, and localized wound infection. |

(relative risk, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.66 to 1.89; p = 0.683) No significant difference |

||

| Wang R, 2015 [36] | 20 studies but did not specified Which studies included in meta-analysis | proportion of diabetic foot ulcer healing |

OR(95% CI; 0.36(0.24–0.54) In favor of NPWT |

Critical low |

| 15 studies but did not specified Which studies included in meta-analysis | Time to wound closure |

standard mean difference and 95% confidence interval, −18 [−29, −6.6] In favor of NPWT |

||

| 15 studies but did not specified Which studies included in meta-analysis | Decrement in ulcer area |

standard mean difference and 95% confidence interval, −18 [−29, −6.7] In favor of NPWT |

||

| Liu, Si, 2017 [18] |

Armstrong et al. 2005 [46] Blume et al. 2008 [8] Nain et al. 2001 [55] Vaidhya et al. [59] Ravari et al. [60] |

Complete healing |

RR; 1.48 (95% CI: 1.24–1.76, P < 0.0001) In favor of NPWT |

High |

|

Mc Callon et al.2000 [42] Karatepe et al. 2004 [37] |

Time to Complete healing |

(mean difference: −8.07, 95% CI: −13.70– −2.45, P = 0.005) In favor of NPWT |

||

|

Nain et al.,2001 [55] Ravari et al.,2013 [60] Mc Callon et al., 2000 [42] Eginton et al., 2003 [41] Sun and sun et al., 2007 [58] Sajid et al., 2015 [61] |

Reduction of ulcer size |

95% CI: 8.50–15.86, P < 0.0001 In favor of NPWT |

||

|

Armstrong et al. 2005 [46] Blume et al., 2008 [8] Sepulveda et al., 2009 [48] |

Treatment related Adverse events |

95% CI: 0.66–1.89, P = 0.68) No significant diference |

SR systematic review, MA meta-analysis

One review specifically investigated the NPWT effectiveness on the infection control rather than ulcer healing. However because of missing details, they could not able to draw any conclusions regarding with NPWT therapy [33] (Table 2).

The duration of treatment ranged from 2 to 36 weeks in the included studies in reviews.

Owing to the extent of information provided by the 23 reviews, only the results of high quality SRs/MAs are reported in result section and details of the remaining studies are presented in Table 2.

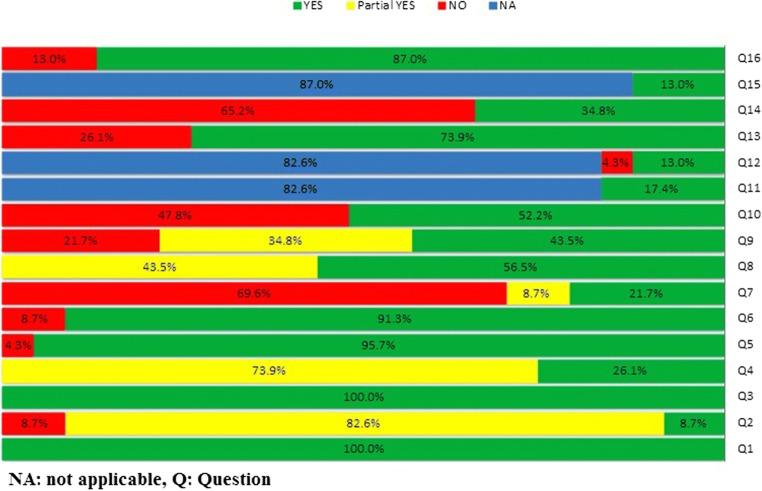

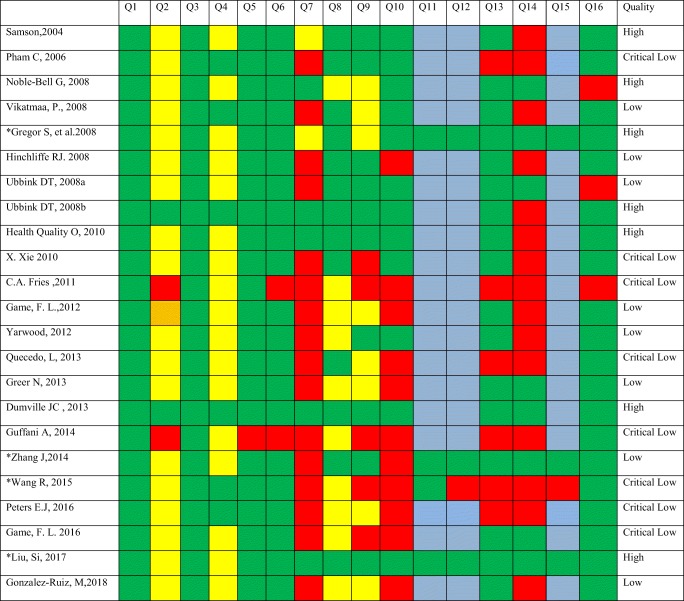

Methodological quality assessment

Figure 2 displays the overall proportions of each of the 16 criteria on the AMSTAR 2 checklist. Moreover, Table 4 represents the methodological quality of included studies. Based on AMSTAR- 2, 7 reviews (including 2 meta- analyses) did not contain any critical domain flaw, in which the quality was settled high. Eight reviews contained one critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses, and the quality of them was considered low. Two or more domains of critical flaw were perceived in 8 reviews, and the quality of these reviews was considered critically low.

Fig. 2.

AMSTAR-2 Quality Assessment Results. NA: not applicable, Q: Question

Table 4.

Quality assessment results of included reviews based on AMSTAR-2.

Q question

Q question

*Meta analyses

Based on the extracted conclusions of included reviews, the results were focused on effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness. In order to clarify the outcomes, the authors characterized the results as beneficial (the evidence support the NPWT usage), inconclusive (the evidence could not achieved a clear conclusion), and not applicable (the evidence did not evaluate the mentioned item) (Table 2).

All of the reviews fulfilled the PICO criteria.

Only 2 Cochrane systematic reviews stated about a developed priori protocol that might be resulted in modification of the methods during review process. Six studies (26.1%) used a comprehensive search strategy. Data extraction and selection had been prepared by at least 2 reviewers in 95.6% of the studies. Eleven reviews did not mention any conflict of interest (COI) presented in their included studies.

All 20 reviews assessed the risk of bias but 3 reviews did not elucidate the consideration of one or more recognized risk of bias indices. Four S/A and one M/A did not mention any technique for assessing the risk of bias (RoB) in their included studies.

One out of four M/As did not examine the publication bias of its included RCTs. The methods used for evaluating the quality or risk of bias of individual trials varied across reviews.

Outcome results for DFUs complete healing

Main findings and authors conclusions of included SRs/MAs are presented in Table 2.

A consensus clinical effectiveness with regard to the proportion of wound healing (in terms of complete wound closure, wound reduction area or decrease in wound volume) was in favor of NPWT in the majority of the reviews. However, specifically, high quality SRs indicated that many of their reviewed trials were of poor to moderate quality.

A recently well conducted M/A by Liu et al. [18] analyzed the results of 11 RCTs evaluating NPWT for patient with DFU. They classified only one of the RCTs as having a low risk of bias. They pooled 5 articles, consisting of 617 diabetic patients with study duration of 2–16 weeks, and found a significantly higher healing rate in the NPWT group compared to controls (RR: 1.48, 95% CI: 1.24–1.76, P < 0.0001). Dumville JC et al. [15], evaluated 5 RCTs as having low or very low quality. Two included RCTs compared NPWT with advanced moist wound treatment (AMWT) during 16 weeks. They found that the rate of wound healing is in favor of NPWT group (RR (95% CI): 1.47(1.18, 1.84, P < 0.001)).

Outcome results for wound area/volume reduction

In a meta-analysis of 6 RCTs consisting of 389 patients Liu et al. [18] found that NPWT reduced DFU area more effectively than standard dressing group (95% CI: 8.50–15.86, P < 0.00001).

In a meta-analysis of 2 non-RCTs (including 34 patients) by Gregor et al. [35], a significant reduction in wound size was detected in favor of NPWT (SMD,-1.3; 95% CI, −2.07 to −0.54).

Samson et al. [23] and Ubbink et al. [26] recruited the same 2 RCTs (with poor quality) consisting of 20 patients. They found that the rate of reduction in ulcer area/volume was in favor of TNP group (average decrease of 28.4% (SD 24.3) in the TNP group compared with an Increase of 9.5% (SD 16.9) in the gauze group).

Outcome results for time to complete healing

Dumville et al. [15] and OHTA group [27] in evaluating 2 commonly RCTs consisting of 504 patients with 16 weeks study duration, found that the median time to complete wound closure was significantly shorter in NPWT group in both RCTs (p = 0.001 and p = 0.005).

Liu et al. [18] in the meta-analysis of 2 RCT results found that NPWT had a shorter time to complete healing (SMD-8.07,95%CI:-13.7- -2.45, P = 0.005). However, Samson et al. [23] and Ubbink et al. [26] reported that although the wound healing was shorter in NPWT group (about 20 days), the difference was trivial and non-significant .

Outcome results for NPWT cost effectiveness

In one of the included RCTs in Liu et al. [18] study, the mean number of dressings to achieve a satisfactory result was 7.46 ± 2.25 in NPWT compared to 69.8 ± 11.93 in conventional dressing group (p < 0.001). The majority of studies did not obviously discuss the cost benefits of NPWT.

Outcome results for treatment- related adverse events

In pooling data from 3 RCTs (528 patients) by Liu et al., no significant difference was found regarding adverse events (pain, infection, bleeding) between NPWT group and standard dressing group (95% CI: 0.66–1.89, P = 0.68).

Dumville et al. [15] found that there is no statistically significant difference in the number of participants experiencing one or more treatment-related adverse events in the NPWT group compared with the moist dressing group (RR: 0.9; 95% CI 0.4 to 2.06). Noble-Bell et al. [16] stated that no serious treatment-related adverse events is detected in their 4 included RCTs.

Discussion

Based on the findings of the present systematic review, some points are revealed regarding this intervention. We found a heterogeneity between the majority of SAs/MAs with regard to the sample size (20 to 2800 patients), treatment duration (2–36 weeks), methodology used for assessing ROB/ quality of their included studies, as well as the large number of low/critically low SRs/MAs according to AMSTAR-2 appraisal and etc). These factors could stand to justify the various outcomes of NPWT usage.

On the other hand, still there is scarce of available high-quality clinical trials supporting the superiority of this technology compared to other standard treatments. Other issues are the restricted access to the unpublished data as well as publication bias that can lead to publish only positive results [38].

As mentioned above, the discussion was expanded in three areas of effectiveness, safety and cost-effectiveness of NPWT therapy. Hence, three, two and one out of seven high quality studies approved the effectiveness, safety and cost benefit of the NPWT therapy, respectively.

Assessment of NPWT effectiveness

We found that NPWT is likely to be effective based on data from a high quality systematic review including a meta-analysis in terms of higher rate of complete healing and shorter healing time [18]. Nevertheless, an emphasize should be made on designing further robust RCTs to strengthen the treatment usage.

Likewise, the majority of other included SAs/MAs in this overview with any quality type, stated about a beneficial effectiveness of NPWT as compared to SMWT/AMWT regarding with wound healing, more reduction of ulcer area/volume, and wound healing duration [11–14, 16, 25, 27–30, 34, 36, 37]. However, some of these reviews elucidated about the weakness in the quality of RCTs included in their SAs/MAs. On the other hand, 3 of the high quality reviews indicated that the evidence to support NPWT effectiveness in diabetic wound healing is not strong [15, 26, 35].

Assessment of NPWT safety

The adverse events associated with NPWT treatment could be infection, pain and edema, bleeding and mortality. Adverse events were reported in 16 studies where a comparison is made between NPWT and other treatments. Generally, most of them did not achieve a significant difference in any serious adverse events regarding with NPWT system compared to other standard treatments.

Assessment of NPWT cost effectiveness

Regarding with high NPWT expenditure and lack of full coverage by insurance companies the cost effectiveness of this therapy could be influenced by other factors such as faster healing time, shorter duration of hospitalization, number of treatment sessions, and number of dressing changes. In a recent meta-analysis by Liu etal. [18], a significant faster healing time was detected by NPWT technology as compared to other standard dressings. This finding can justify the cost benefit of the NPWT.

Conclusion

It seems that to conclude a definite answer about effectiveness of NPWT, more high-quality RCTS, with larger sample size, high power and adjust factor analysis are required.

Moreover, the combination of these data with a meta-analysis could support the clinicians to decide upon the effectiveness of negative pressure. In order to find a concrete response on the safety and cost effectiveness of NPWT, high quality economic and cost-benefit studies containing health economic indicators are needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Tricco, A. C et al. [39] and Anaya, M.M et al. [40] in terms of their valuable articles which guided us for preparing Fig. 2 and Table 4 of the study.

Funding information

This study was funded by the Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Institute affiliated to Tehran University of Medical Sciences Grant ≠ 1394–03–108-1996.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shahrzad Mohseni, Email: Shmohseni58@gmail.com.

Maryam Aalaa, Email: aalaamaryam@gmail.com.

Rasha Atlasi, Email: rashaatlasi@gmail.com.

Mohamad Reza Mohajeri Tehrani, Email: mrmohajeri@tums.ac.ir.

Mahnaz Sanjari, Email: msanjari@tums.ac.ir.

Mohamad Reza Amini, Email: mramini@tums.ac.ir.

References

- 1.Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I, Beagley J, Linnenkamp U, Shaw JE. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103(2):137–149. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Internal Clinical Guidelines t . National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Clinical Guidelines. Diabetic Foot Problems: Prevention and Management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK) Copyright (c) 2015 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morbach S, Furchert H, Groblinghoff U, Hoffmeier H, Kersten K, Klauke GT, et al. Long-term prognosis of diabetic foot patients and their limbs: amputation and death over the course of a decade. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(10):2021–2027. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newrick P. International consensus on the diabetic foot. BMJ. 2000;321(7261):642A-A. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Leone S, Pascale R, Vitale M, Esposito S. [Epidemiology of diabetic foot]. Le infezioni in medicina : rivista periodica di eziologia, epidemiologia, diagnostica, clinica e terapia delle patologie infettive. 2012;20 Suppl 1:8–13. [PubMed]

- 6.Bus SA, Armstrong DG, van Deursen RW, Lewis JE, Caravaggi CF, Cavanagh PR. IWGDF guidance on footwear and offloading interventions to prevent and heal foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32(Suppl 1):25–36. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Cornia PB, Pile JC, Peters EJG, Armstrong DG, Deery HG, Embil JM, Joseph WS, Karchmer AW, Pinzur MS, Senneville E, Infectious Diseases Society of America 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot Infectionsa. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(12):e132–ee73. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blume PA, Walters J, Payne W, Ayala J, Lantis J. Comparison of negative pressure wound therapy using vacuum-assisted closure with advanced moist wound therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(4):631–636. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isaac Adam L., Armstrong David G. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy and Other New Therapies for Diabetic Foot Ulceration. Medical Clinics of North America. 2013;97(5):899–909. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2013.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Argenta Louis C., Morykwas Michael J. Vacuum-Assisted Closure: A New Method for Wound Control and Treatment. Annals of Plastic Surgery. 1997;38(6):563–577. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199706000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Game FL, Hinchliffe RJ, Apelqvist J, Armstrong DG, Bakker K, Hartemann A, et al. A systematic review of interventions to enhance the healing of chronic ulcers of the foot in diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28(Suppl 1):119–141. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie X, McGregor M, Dendukuri N. The clinical effectiveness of negative pressure wound therapy: a systematic review. J Wound Care. 2010;19(11):490–495. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2010.19.11.79697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vikatmaa P., Juutilainen V., Kuukasjärvi P., Malmivaara A. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy: a Systematic Review on Effectiveness and Safety. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery. 2008;36(4):438–448. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greer N, Foman NA, MacDonald R, Dorrian J, Fitzgerald P, Rutks I, Wilt TJ. Advanced wound care therapies for nonhealing diabetic, venous, and arterial ulcers: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(8):532–542. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-8-201310150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dumville JC, Hinchliffe RJ, Cullum N, Game F, Stubbs N, Sweeting M. Negative pressure wound therapy for treating foot wounds in people with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(1). 10.1002/14651858.CD010318. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Noble-Bell G, Forbes A. A systematic review of the effectiveness of negative pressure wound therapy in the management of diabetes foot ulcers. Int Wound J. 2008;5(2):233–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2008.00430.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orgill DP, Bayer LR. Update on negative-pressure wound therapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(Suppl 1):105s–115s. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318200a427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu S, He CZ, Cai YT, Xing QP, Guo YZ, Chen ZL, Su JL, Yang LP. Evaluation of negative-pressure wound therapy for patients with diabetic foot ulcers: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2017;13:533–544. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s131193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith V, Devane D, Begley CM, Clarke M. Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(1):15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Ubbink DT, Westerbos SJ, Nelson EA, Vermeulen H. A systematic review of topical negative pressure therapy for acute and chronic wounds. Br J Surg. 2008;95(6):685–692. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samson D, Lefevre F, Aronson N. Wound-healing technologies: low-level laser and vacuum-assisted closure. Evidence report/technology assessment (Summary). 2004(111):1–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Pham CT, Middleton PF, Maddern GJ. The safety and efficacy of topical negative pressure in non-healing wounds: a systematic review. J Wound Care. 2006;15(6):240–250. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2006.15.6.26926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hinchliffe RJ, Valk GD, Apelqvist J, Armstrong DG, Bakker K, Game FL, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions to enhance the healing of chronic ulcers of the foot in diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24(Suppl 1):S119–S144. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ubbink DT, Westerbos SJ, Evans D, Land L, Vermeulen H. Topical negative pressure for treating chronic wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008b;3. 10.1002/14651858.CD001898.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Health Quality O. Negative pressure wound therapy: an evidence update. Ontario health technology assessment series. 2010;10(22):1–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Fries C.A., Jeffery S.L.A., Kay A.R. Topical negative pressure and military wounds—A review of the evidence. Injury. 2011;42(5):436–440. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yarwood-Ross Lee, Dignon Andree Marie. NPWT and moist wound dressings in the treatment of the diabetic foot. British Journal of Nursing. 2012;21(Sup15):S26–S32. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2012.21.Sup15.S26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quecedo L, Llano J. Systematic review of studies on efficacy of negative pressure therapies in complex diabetic foot wounds (Provisional abstract). PharmacoEconomics - Spanish Research Articles 2013.

- 31.Guffanti Alan. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy in the Treatment of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Journal of Wound, Ostomy & Continence Nursing. 2014;41(3):233–237. doi: 10.1097/WON.0000000000000021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Game FL, Apelqvist J, Attinger C, Hartemann A, Hinchliffe RJ, Löndahl M, Price PE, Jeffcoate WJ, International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot Effectiveness of interventions to enhance healing of chronic ulcers of the foot in diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32:154–168. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peters EJ, Lipsky BA, Aragón-Sánchez J, Boyko EJ, Diggle M, Embil JM, Kono S, Lavery LA, Senneville E, Urbančič-Rovan V, van Asten S, Jeffcoate WJ, International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot Interventions in the management of infection in the foot in diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2016;32:145–153. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.González-Ruiz M, Torres-González JI, Pérez-Granda MJ, Leñero-Cirujano M, Corpa-García A, Jurado-Manso J et al. Efectividad de la terapia de presión negativa en la cura de úlceras de pie diabético: revisión sistemática. Rev Int Cienc Podol. 2018;12(1):1–13. 10.5209/Ricp.57985.

- 35.Gregor Sven. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy. Archives of Surgery. 2008;143(2):189. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2007.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang R, Feng Y, Di B. Comparisons of negative pressure wound therapy and ultrasonic debridement for diabetic foot ulcers: a network meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(8):12548–12556. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Jian, Hu Zhi-Cheng, Chen Dong, Guo Dong, Zhu Jia-Yuan, Tang Bing. Effectiveness and Safety of Negative-Pressure Wound Therapy for Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2014;134(1):141–151. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peinemann F, McGauran N, Sauerland S, Lange S. Negative pressure wound therapy: potential publication bias caused by lack of access to unpublished study results data. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tricco AC, Antony J, Vafaei A, Khan PA, Harrington A, Cogo E, et al. Seeking effective interventions to treat complex wounds: an overview of systematic reviews. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0288-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anaya MM, Franco JVA, Ballesteros M, Sola I, Cuchí GU, Cosp XB. Evidence mapping and quality assessment of systematic reviews on therapeutic interventions for oral cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:117. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S186700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eginton MT, Brown KR, Seabrook GR, Towne JB, Cambria RA. A prospective randomized evaluation of negative-pressure wound dressings for diabetic foot wounds. Ann Vasc Surg. 2003;17(6):645–649. doi: 10.1007/s10016-003-0065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCallon SK, Knight CA, Valiulus JP, Cunningham MW, McCulloch JM, Farinas LP. Vacuum-assisted closure versus saline-moistened gauze in the healing of postoperative diabetic foot wounds. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2000;46(8):28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, Lohr KN, Mulrow CD, Teutsch SM, Atkins D, Methods Work Group, Third US Preventive Services Task Force Current methods of the US preventive services task force: a review of the process. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(3 Suppl):21–35. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Armstrong DG, Lavery LA, Abu-Rumman P, Espensen EH, Vazquez JR, Nixon BP, et al. Outcomes of subatmospheric pressure dressing therapy on wounds of the diabetic foot. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2002;48(4):64–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Etoz A, Kahveci R. Negative pressure wound therapy on diabetic foot ulcer. Wounds : a compendium of clinical research and practice. 2007;19(9):250–4. [PubMed]

- 46.Armstrong DG, Lavery LA, Consortium DFS. Negative pressure wound therapy after partial diabetic foot amputation: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9498):1704–1710. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67695-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akbari Asghar, Moodi Hesam, Ghiasi Fatemeh, Sagheb Hamidreza Mahmoudzadeh, Rashidi Homayra. Effects of vacuum-compression therapy on healing of diabetic foot ulcers: Randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 2007;44(5):631. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2007.01.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sepúlveda Gustavo, Espíndola Manuel, Maureira Mauricio, Sepúlveda Edgardo, Fernández José Ignacio, Oliva Claudia, Sanhueza Antonio, Vial Manuel, Manterola Carlos. Curación asistida por presión negativa comparada con curación convencional en el tratamiento del pie diabético amputado. Ensayo clínico aleatorio. Cirugía Española. 2009;86(3):171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frykberg RG, Williams DV. Negative-pressure wound therapy and diabetic foot amputations: a retrospective study of payer claims data. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2007;97(5):351–359. doi: 10.7547/0970351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karatepe O, Eken I, Acet E, Unal O, Mert M, Koc B, Karahan S, Filizcan U, Ugurlucan M, Aksoy M. Vacuum assisted closure improves the quality of life in patients with diabetic foot. Acta Chir Belg. 2011;111(5):298–302. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2011.11680757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Apelqvist J, Armstrong DG, Lavery LA, Boulton AJ. Resource utilization and economic costs of care based on a randomized trial of vacuum-assisted closure therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot wounds. Am J Surg. 2008;195(6):782–788. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic review of interventions version 5.1. 0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011. Available from www cochrane-handbook org. 2013.

- 53.Mody GN, Nirmal IA, Duraisamy S, Perakath B. A blinded, prospective, randomized controlled trial of topical negative pressure wound closure in India. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2008;54(12):36–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Novinscak T, Zvorc M, Trojko S, Jozinovic E, Filipovic M, Grudic R. Comparison of cost-benefit of the three methods of diabetic ulcer treatment: dry, moist and negative pressure. Acta Med Croatica. 2010;64(Supl 1):113–115. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garg Ramneesh, Bajaj Kuljyot, Garg Shirin, Nain PrabhdeepSingh, Uppal SanjeevK. Role of negative pressure wound therapy in healing of diabetic foot ulcers. Journal of Surgical Technique and Case Report. 2011;3(1):17. doi: 10.4103/2006-8808.78466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dalla Paola L, Carone A, Ricci S, Russo A, Ceccacci T, Ninkovic S. Use of vacuum assisted closure therapy in the treatment of diabetic foot wounds.

- 57.SIGN: critical appraisal: notes and checklists 6th november 2014.

- 58.Jian-wei S, Jian-hui S, Chun-cai Z. Vacuum assisted closure technique for repairing diabetic foot ulcers: analysis of variance by using a randomized and double-stage crossover design. J Clin Rehab Tissue Eng Res.2007;11(44):8908.

- 59.Vaidhya Nikunj, Panchal Arpit, Anchalia M. M. A New Cost-effective Method of NPWT in Diabetic Foot Wound. Indian Journal of Surgery. 2013;77(S2):525–529. doi: 10.1007/s12262-013-0907-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ravari H, Modaghegh M-HS, Kazemzadeh GH, Johari HG, Vatanchi AM, Sangaki A, et al. Comparision of vacuum-asisted closure and moist wound dressing in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2013;6(1):17–20. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.110091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sajid MT, Mustafa Q, Shaheen N, Hussain SM, Shukr I, Ahmed M. Comparison of Negative Pressure Wound Therapy Using Vacuum-Assisted Closure with Advanced Moist Wound Therapy in the Treatment of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2015;25(11):789–93. [PubMed]

- 62.Lavery LA, La Fontaine J, Thakral G, Kim PJ, Bhavan K, Davis KE. Randomized clinical trial to compare negative-pressure wound therapy approaches with low and high pressure, silicone-coated dressing, and polyurethane foam dressing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(3):722–726. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000438046.83515.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lone Ali M., Zaroo Mohd I., Laway Bashir A., Pala Nazir A., Bashir Sheikh A., Rasool Altaf. Vacuum-assisted closure versus conventional dressings in the management of diabetic foot ulcers: a prospective case–control study. Diabetic Foot & Ankle. 2014;5(1):23345. doi: 10.3402/dfa.v5.23345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lavery LA, Barnes SA, Keith MS, Seaman JW, Armstrong DG. Prediction of healing for postoperative diabetic foot wounds based on early wound area progression. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(1):26–29. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang SL, Han R, Liu Y, Hu LY, Li XL, Zhu LY. Negative pressure wound therapy is associated with up-regulation of bFGF and ERK 1/2 in human diabetic foot wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2014;22(4):548–554. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]