Abstract

Sows often receive the same feed during gestation even though their nutrient requirements vary during gestation and among sows. The objective of this study was to report the variability in nutrient requirement among sows and during gestation, in order to develop a precision feeding approach. A data set of 2,511 gestations reporting sow characteristics at insemination and their farrowing performance was used as an input for a Python model, adapted from InraPorc, predicting nutrient requirement during gestation. Total metabolizable energy (ME) requirement increased with increasing litter size, gestation weeks, and parity (30.6, 33.6, and 35.5 MJ/d for parity 1, 2, and 3 and beyond, respectively, P < 0.01). Standardized ileal digestible lysine (SID Lys) requirement per kg of diet increased from weeks 1 to 6 of gestation, remained stable from weeks 7 to 10, and increased again from week 11 until the end of gestation (P < 0.01). Average Lys requirement increased with increasing litter size (SID Lys: 3.00, 3.27, 3.50 g/kg for small, medium and large litters, P < 0.01) and decreased when parity increased (SID Lys: 3.61, 3.17, 2.84 g/kg for parity 1, 2, and 3++, P < 0.01). Standardized total tract digestible phosphorus (STTD-P) and total calcium (Total-Ca) requirements markedly increased after week 9, with litter size, and decreased when parity increased (STTD-P: 1.36 vs. 1.31 g/kg for parity 1 and parity 3 and beyond; Total-Ca: 4.28 vs. 4.10 g/kg for parity 1 and parity 3 and beyond, P < 0.01). Based on empirical cumulative distribution functions, a 4-diets strategy, varying in SID Lys and STTD-P content according to parity and gestation period (P1 from weeks 0 to 11, P2 from weeks 12 to 17), may be put forward to meet the requirements of 90% of the sows (2 diets for multiparous sows: P1: 2.8 g SID Lys/kg and 1.1 g STTD-P/kg; P2: 4.5 g SID Lys/kg and 2.3 g STTD-P/kg; and 2 diets for primiparous sows: P1: 3.4 g SID Lys/kg and 1.1g STTD-P/kg; P2: 5.0 g SID Lys/kg, 2.2 g STTD-P/kg). Better considering the high variability of sow requirement should thus make it possible to optimize their performance whilst reducing feeding cost and excretion. Feeding sows closer to their requirement may initially be achieved by grouping and feeding sows according to gestation week and parity, and ultimately by feeding sows individually using a smart feeder allowing the mixing of different feeds differing in their nutrient content.

Keywords: gestation, individual variability, modeling, nutrition, requirements, sow

Introduction

Nutrient requirement for sows is relatively variable throughout gestation (NRC, 2012). At the end of gestation, requirements for energy (Noblet et al., 1987), amino acids (King and Brown, 1993; Dourmad and Etienne, 2002; NRC, 2012), and minerals (Jondreville and Dourmad, 2005; NRC, 2012) are much higher than in early gestation. These requirements also vary among sows (McPherson et al., 2004; Dourmad et al., 2008) according to their body condition and prolificacy. However, in practice, all sows are generally fed the same standard gestation feed and only feed allowance may vary according to parity, gestation stage, and body condition (Young et al., 2004). In all cases, this leads to under- or over-feeding situations which may result in a lack of performance and health issues on the one hand, and economic loss and environmental negative effects on the other. There is therefore a need to adjust the feed composition and feeding level of gestating sows more precisely. In practice, this individual fitting ought to be possible thanks to the development of innovative technologies (feeders and sensors), which allow the distribution of tailored rations and provide an increasing number of real-time data on animal characteristics and housing conditions, and the development of mathematical models that predict daily nutrient requirement for each animal as has successfully been done for growing pigs (Cloutier et al., 2015) and lactating sows (Gauthier et al., 2019). For that purpose, it is necessary to dynamically determine the individual nutrient requirement during gestation according to the specific information available for each sow. The objective of this study was thus to develop such a model and use it to explore on the basis of real farm data the within-farm variability in nutrient requirement among sows and over gestation period.

Material and Methods

General Approach

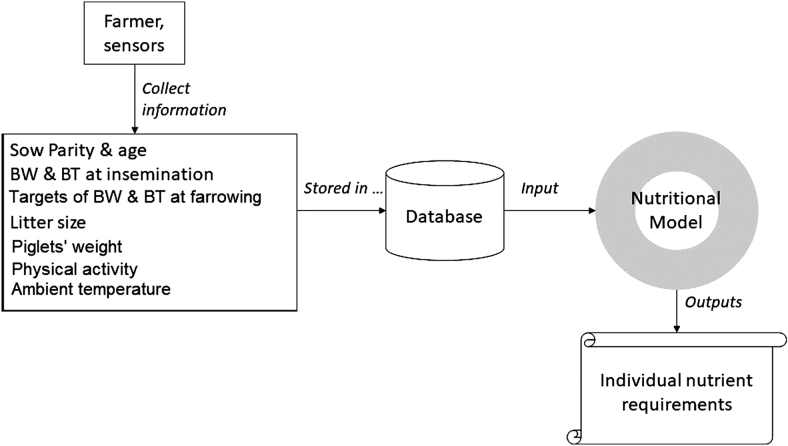

The originality of the approach developed (Figure 1) is the combination of current knowledge about the nutrient use of sows with the flow of data recorded on-farm, to provide a dynamic determination of optimal nutrient supplies for each sow. These data include 1) insemination events (date of insemination, parity, body weight (BW) and back fat thickness (BT) of sows), 2) events that occur during gestation (measurements of the physical activity of sows, BW, and BT), and 3) farrowing events (date of farrowing, litter size, and piglet birth weight). In practice, the farmer or sensors can record these types of data, which may provide a more accurate and dynamic prediction of nutrient requirement. A mechanistic module based mainly on the InraPorc model (Dourmad et al., 2008) with some improvements was used on a daily basis to calculate nutrient requirement. The module calculates daily maintenance costs and gestation costs for each sow, considering its performance. With this approach, nutrient requirement may change according to gestation days, sow performance, and individual farm situation.

Figure 1.

Estimate of individual nutrient requirement from data collected on-farm.

Model Description

General approach

The sow model used in this paper is adapted from the InraPorc model and was applied to the gestation period only. The sow is represented as the sum of different compartments (body lipid, body protein, and uterus), the status of these compartments being used to estimate the sow BW and BT. A computerized version of this model based on the set of equations described hereinafter was developed in order to be able to predict the dynamics and the variability in nutrient requirement of a large population of sows.

ME requirements

Total metabolizable energy (ME) requirement was calculated as the sum of the requirements for the maintenance, physical activity and thermoregulation, maternal growth and constitution of body reserves, and the development of fetuses and uterine contents (Table 1). First of all, individual average ME requirement was calculated during gestation (Table 1, Eq. 1a). This calculation takes into account maternal BW and BT at insemination and their targets at farrowing, as well as litter size (LS) and the average piglet birth weight. The target of BW after farrowing was determined based on the objective of BW evolution with age, which is defined according to a generalized Weibull function calibrated according to the genotype of the sows on the farm (Dourmad et al., 2008):

Table 1.

Main equations describing energy and protein utilization by gestating sows (adapted from Dourmad et al., 2008)

| Energy utilization | ME = MEm + ERc / kc + ERm / km [1a] |

| ME = MEm + ERc / kc + ERmp / kp + ERml / kl (- ERml / kr x kr) [1b] | |

| MEm: ME for maintenance | |

| ERc: energy retention in conceptus | |

| ERml: energy retained in maternal lipids | |

| ERmp: energy retained in maternal protein | |

| kc = 0.50 efficiency of ME retention in conceptus | |

| kp = 0.60 efficiency of ME retention in maternal protein | |

| kl = 0.80 efficiency of ME retention in maternal lipids | |

| km = 0.77 average efficiency of ME retention in maternal tissues | |

| kr = 0.80 efficiency of energy utilization from maternal reserves | |

| ME for maintenance and effect of activity and ambient temperature | in thermoneutral conditions |

| MEm = 440 kJ.BW-0.75.d−1 (for 240 min.d−1 standing activity) [2] | |

| physical activity = 0.30 KJ. kg BW-0,75.d−1.min−1 standing [3] | |

| below lower critical temperature (LCT) | |

| In individually housed sows: LCT = 20 °C | |

| MEm increases by 18 kJ.kg BW-0.75.d−1.°C−1 [4] | |

| In group-housed sows: LCT = 16°C MEm increases by 10 kJ.kg BW-0.75.d−1.°C−1 [5] |

|

| Energy retention |

ERc(t): Total energy in conceptus (kJ) on day t |

| ERc(t) = exp(11.72 − 8.62 e−0,0138 t + 0.0932 Litter size) [6] | |

| ERmp: Energy in maternal tissues as protein (MJ) | |

| ERmp(t) = 23.8 x 6.25 x NRm(t) [7] | |

| ERml: energy in maternal tissues as lipids (MJ) Energy balance > 0 |

|

| ERml(t) = (ME –(MEm + ERc / kc + ERmp / kp)) x kl [8a] | |

| Energy balance < 0 | |

| ERml(t) = (ME –(MEm + ERc / kc + ERmp / kp)) / kr [8b] | |

| Nitrogen retention | NRc: Total N content in conceptus (g), |

| NRc(t) = exp(8.090 − 8.71 e−0,0149 t + 0.0872 Litter size)/6.25 [9] | |

| NR: Total N retention (g.d-1) | |

| NR(t) = 0.85 (d(NRc)/dt − 0.4 + 45.9 (t/100) − 105.3 (t/100)2 + | |

| 64.4 (t/100)3)+ a (ME − MEmm) [10] | |

| where a = f(BW at mating) and MEmm = MEm at mating | |

| NRm: N retention in maternal tissues (MJ) | |

| NRm (t) = NR(t) − NRc(t) [11] | |

| Maternal protein and lipid deposition | PRm(t): maternal protein retention in tissues (g/d) |

| PRm(t) = NRm(t) x 6.25 [12] | |

| LIm(t): maternal lipid retention (g/d) | |

| LIm(t) = ERml(t) / 39.5 [13] | |

| Nutrient and energy in maternal body |

ERm: Total energy content in maternal tissues (MJ) |

| ERm = -1074 + 13.65 EBW + 45.94 BF [14] | |

| PROTm: Total protein content in maternal tissues (kg) | |

| PROm = 2.28 + 0.178 EBW – 0.333.94 B [15] | |

| LIPm: Total energy in maternal tissues (kg) | |

| LIPm = -26.4 + 0.211 EBW + 1.31 BF [16] |

The objective of BT at farrowing may depend on farming practices, with the same value being generally used for all parities. Sow BW before farrowing is calculated based on maternal BW and litter weight. The energy retention level to be attained in maternal tissues is calculated according to BW and BT gains during gestation (Table 1, Eq. 14). Energy retention in conceptus is calculated according to litter size (Table 1, Eq. 6). Maintenance requirement is calculated according to the average sow BW during gestation (Table 1, Eq. 2), with possible modulations according to housing conditions and sow activity (Table 1, Eq. 3, 4, and 5)

Secondly, nutrient- and energy-use was simulated on a daily basis for each sow assuming that they received the amount of ME corresponding to their individual requirements calculated in the first step. Metabolizable energy intake was partitioned into 1) maintenance requirement, which was predicted according to the BW of sows the previous day (Table 1, Eq. 2), 2) thermoregulation requirement, depending on the ambient temperature and housing type (group or individual) (Table 1, Eq. 4 and 5), 3) conceptus growth requirement, which was calculated based on the energy retained in conceptus and the efficiency of the use of ME for uterine growth, and 4) a remaining fraction utilized for maternal gain, and divided into protein and lipid deposition (Table 1, Eq. 1b). The amount of energy deposited as protein in maternal tissues was calculated (Table 1, Eq. 7) based on maternal nitrogen retention (NRm) (Table 1, Eq. 11), determined as the difference between total nitrogen retention (NR) (Table 1, Eq. 10) and nitrogen retention in conceptus (NRc) (Table 1, Eq. 9). The calculation of the amount of lipids deposited (LIm) or mobilized in maternal tissues was based on the amount of ME remaining or missing and the efficiency of ME for fat deposition, or on the efficiency of energy mobilization from body reserves to provide ME in the case of energy deficits (Table 1, Eq. 8a and b). Maternal protein (PRm) gain was calculated according to NRm (Table 1, Eq. 12) and maternal lipid gain (LIm) was calculated according to the energy retained in maternal tissue as lipids (Table 1, Eq. 13).

Amino acid requirements

Maintenance, maternal, and conceptus growth requirements were calculated for all essential amino acids (AA) (Table 2, Eq. 17). Maternal AA requirement covers lean tissue growth as well as growth of uterus (Walker and Young, 1992). Maintenance requirement was calculated as the sum of desquamation (skin and hair), minimum turnover, and basal endogenous intestinal losses (van Milgen et al., 2008 and NRC, 2012). Desquamation was estimated for each AA according to sow metabolic BW (Moughan, 1999). Requirement for minimum protein turnover also expressed per kg of metabolic weight reflects the minimum AA catabolism (van Milgen et al., 2008). Basal endogenous losses are composed of the fraction of protein originating from the enzymes secreted in the intestinal tract or from the desquamated intestinal cells which are not reabsorbed by the sow. They depend on dry matter feed intake (Sauvant et al., 2004). As proposed by van Milgen et al. (2008) for growing pigs and by Gauthier et al. (2019) for lactating sows, the maximum marginal efficiencies (kAA) of AA were calculated based on the assumption that the ideal AA profile for gestation was obtained for a sow weighing 200 kg on average, consuming 2.4 kg DM/d, with an average protein retention of 52 and 23 g/d in maternal tissues and conceptus, respectively. The maximum efficiency of lysine (Lys) above maintenance was set at 0.72 (Dourmad et al., 2002; NRC, 2012), from which the kAA values of the other AA were calculated and used to calculate standardized ileal digestible AA requirements (Table 3).

Table 2.

Main equations describing amino-acids, Ca, and P utilization by gestating sows

|

Amino Acid requirements

AAreq = (AAd + AAt)/1000 x BW0.75/1000 + DMI x AAe + (NRm x 6.25 x AAmc + NRc x 6.25 x AAcc) / kAA [17] |

| Phosphorus requirement (g/d) |

| STTD-P(t) = Pm(t)+ (Prm (t)+ (Pfoet(t) − Pfoet(t-1)) +(Pplact(t) − Pplac(t−1))) / 0.98 [18] Pm(t): P maintenance requirement on day t Pm (t)= 7 x BW(t) Prm(t): P retained in maternal tissues according to maternal weight gain (BWGm) on day t Prm(t)= BWGm(t) x 0.96 x (5.4199 − 2 x 0.002857 x BW(t)) Pfoet(t): Total P content in fetuses on day t Pfoet(t) = exp(4.591 − 6.389 x e(−0.02398 x (t-45)) + 0.0897 x LS) x (6.25 x BWl) / e(4.591–6.389 x exp(−0.02398 x (114–45)) + 0.0897 x LS) Pplac(t): Total P content in placenta on day t Pplac(t) = exp(4.591–6.389 x exp(−0.02398 x (t-45)) + 0.0897 x LS) x ((6.25 x BWl) / exp (4.591–6.389 x exp(−0.02398 x 70) + 0.0897 x LS)) |

| Calcium requirement (g/d) |

| STTD-Ca(t) = Cam(t)+ (Carm (t)+ (Cafoet(t)- Cafoet(t-1)) +(Caplact(t)- Caplac(t-1))) / 0.98 [19] Cam(t): Ca maintenance requirement on day t Cam (t) = 10 x BW(t) Cafoet(t): Total P in fetuses on day t Cafoet(t) = Pfoet(t) x 1.759 Caplac (t): Total Ca in placenta on day t Caplact(t) = Pfoet(t) x 1.759 Car(t): Ca retained in maternal tissue on day t Car(t) = Pr(t) x 1.650 |

m = maintenance, c = conceptus, r = reserves, foet = fetus, plac = placenta, LS = litter size, t = time (day in pregnancy), BWl = litter birth body weight of litter (kg), AAd = AA losses due to desquamation (mg/kg BW0.75), AAt = AA losses due to turnover (mg/kg BW0.75), AAe = AA basal endogenous losses (mg/kg dry matter intake), NRuc = conceptus nitrogen retention, NRm = maternal nitrogen retention, AAc = AA content in conceptus protein, AAmc = maternal AA content in protein, kAA = marginal efficiencies

1For maintenance, Bikker and Blok (2017) reported a 6 mg P/kgBW fecal endogenous losses, 1 mg P/kg BW urinary losses (total of 7 mg P/kgBW endogenous losses of P), and 8 mg Ca/kgBW fecal endogenous losses, 2 mg Ca/kg BW urinary losses (total of 10 mg Ca/kgBW endogenous losses).

Table 3.

Maximum efficiency of using standardized ileal digestible protein and amino acids for protein deposition in gestating sows, calculated based on the ideal amino acid profile, maintenance requirement and maternal and fetal protein amino acid contents

| AA | Ideal amino acid profile4, % of Lysine | Integument loss1 (AAd), mg/kg BW0.75 | Losses due to basal turnover1 (AAturn), mg/kg BW0.75 | Basal endogenous losses2 (AAe), g/kg DMI | Content in maternal body protein3, g/16 g N | Content in conceptus protein4, g/16 g N | Maximum efficiency5 (kAA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | |||||||

| Lysine | 100 | 4.5 | 23.9 | 0.313 | 6.96 | 5.90 | 0.726 |

| Methionine | 28 | 1.0 | 7.0 | 0.087 | 1.88 | 1.40 | 0.67 |

| Methionine + Cystine | 65 | 5.7 | 11.7 | 0.227 | 2.91 | 2.70 | 0.47 |

| Tryptophan | 20 | 0.9 | 3.5 | 0.117 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.55 |

| Threonine | 72 | 3.3 | 13.8 | 0.330 | 3.70 | 3.50 | 0.56 |

| Phenylalanine | 60 | 3.0 | 13.7 | 0.273 | 3.78 | 3.40 | 0.69 |

| Phenylalanine + Tyrosine | 100 | 4.9 | 22.7 | 0.496 | 6.64 | 5.80 | 0.73 |

| Leucine | 100 | 5.3 | 27.1 | 0.427 | 7.17 | 6.20 | 0.80 |

| Isoleucine | 65 | 2.5 | 12.4 | 0.257 | 3.46 | 3.00 | 0.55 |

| Valine | 75 | 3.8 | 16.4 | 0.357 | 4.67 | 4.60 | 0.70 |

| Histidine | 32 | 1.3 | 10.2 | 0.130 | 2.79 | 2.30 | 0.96 |

| Arginine | 42 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.280 | 6.26 | 6.80 | 1.51 |

1From Moughan (1999).

2From Noblet et al. (2004).

3From van Milgen et al. (2008).

4From Dourmad et al. (1999).

5The maximum marginal efficiencies were calculated based on the assumption that the ideal amino acid profile is adapted for a sow that weights 200 kg, consumes 2.4 kg DM/d, with a protein retention of 52 and 23 g/d in maternal tissues and conceptus, respectively. The maximum efficiency of lysine above maintenance was set at 0.72 (Dourmad et al., 2002, and NRC, 2012), from which the kAA values of the other amino acids were estimated as kAA = (Protm x AAm + Protc x AAc) / [(Lysmaint + (Protm x Lysm+ Protc x Lysc) / 0.72) x Id(AA:Lys) − AAmaint, where kAA is the marginal efficiency of amino acid “AA,” Protm the maternal protein depositiont, Protc the conceptus protein deposition, Id(AA:Lys) the AA:Lys ratio in the ideal protein for gestation, and AAmaint the AA maintenance requirement, calculated as the sum of requirements for desquamation, turnover and endogenous losses.

Mineral requirements

Standardized total tract digestible phosphorus (STTD-P) and calcium (STTD-Ca) requirements were calculated as the sum of requirements for maintenance, conceptus (fetuses and placenta) growth, and maternal body reserves (Table 2, Eq. 18 and 19). Maintenance requirement was determined according to the literature review by Bikker and Blok (2017) and amounted to 7 and 10 mg/kg BW for phosphorus and calcium, respectively. The retention of phosphorus in fetuses was calculated based on Jongbloed et al. (2003). The retention of phosphorus in the placenta was assumed to be proportional to protein retention considering a phosphorus to protein ratio of 0.96% (Jondreville and Dourmad, 2005). Phosphorus requirement for maternal body reserves was calculated according to BW gain and its P content. As proposed by Bikker and Blok (2017), a 0.98 efficiency of STTD-P was used for P retention and maintenance. Ca retention in conceptus and maternal tissue were calculated according to P retention based on a Ca/P ratio of 1.759 and 1.650 in conceptus and maternal tissues, respectively (Bikker and Blok, 2017). Total calcium (Total-Ca) requirement and Total-Ca/STTD-P ratio were calculated based on a 50% digestibility assumption for STTD-Ca (Bikker and Blok, 2017).

Database Used as an input to the Model for the Calculation of Individual Sow Nutrient Requirement

A data set of 2,511 gestations from crossbred Landrace x Large White sows obtained on an experimental farm from 2009 and 2013 was used. It contained the characteristics of sows as regard to their insemination and farrowing performance used as inputs to the model for predicting the individual variability and dynamics of the evolution of nutrient requirement during gestation. This database contained measures of sow body condition (BW and BT) at insemination and litter performance (Table 4). An individualized target of BW after farrowing was determined for each sow regarding its age and its BW at insemination using a generalized Weibull function, as described previously, adjusted to the set of data,

Table 4.

Description of the database (means ± SD) used to evaluate the variability of requirement1

| Parity | Number of sows | Litter size | Piglets BW, g | Sow BW at AI, kg | Sow BT at AI, mm | Target BW after farrowing, kg | Target BT after farrowing, mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 392 | 13.3 ± 2.94 | 1405 ± 215 | 163 ± 16 | 17.9 ± 4.03 | 203 | 18 |

| 2 | 389 | 13.5 ± 3.12 | 1557 ± 233 | 192 ± 16 | 15.9 ± 3.60 | 227 | 18 |

| 3 | 413 | 14.1 ± 3.43 | 1523 ± 234 | 211 ± 17 | 15.0 ± 3.44 | 243 | 18 |

| 4 | 384 | 14.9 ± 3.17 | 1480 ± 245 | 227 ± 18 | 14.4 ± 3.44 | 255 | 18 |

| 5 | 335 | 15.0 ± 3.09 | 1472 ± 215 | 234 ± 19 | 14.1 ± 3.47 | 260 | 18 |

| 6 | 253 | 14.8 ± 3.47 | 1438 ± 256 | 241 ± 20 | 14.1 ± 3.40 | 263 | 18 |

| 7 | 187 | 13.9 ± 3.54 | 1445 ± 231 | 246 ± 21 | 14.6 ± 3.78 | 265 | 18 |

| 8 | 158 | 13.6 ± 3.77 | 1455 ± 247 | 251 ± 19 | 14.9 ± 3.53 | 267 | 18 |

| All | 2511 | 14.1 ± 3.32 | 1478 ± 234 | 214 ± 18 | 15.2 ± 3.59 | 244 | 18 |

1BW, body weight, BT, backfat thickness, AI, artificial insemination.

The objective of BT after farrowing was set at 18 mm for all sows in accordance with the practices of the farm from which the data were collected.

Average (± SD) LS at farrowing was 14.1 (± 3.3) with an average BW of 1.48 kg per piglet (± 0.24), and a total litter weight of 20.5 (± 4.4) kg. The average BW of the sows at insemination increased from 163 to 251 kg between the first and eighth gestation, whereas BT at insemination tended to be higher for first and second parity sows and then remained relatively constant (Table 4).

Simulations

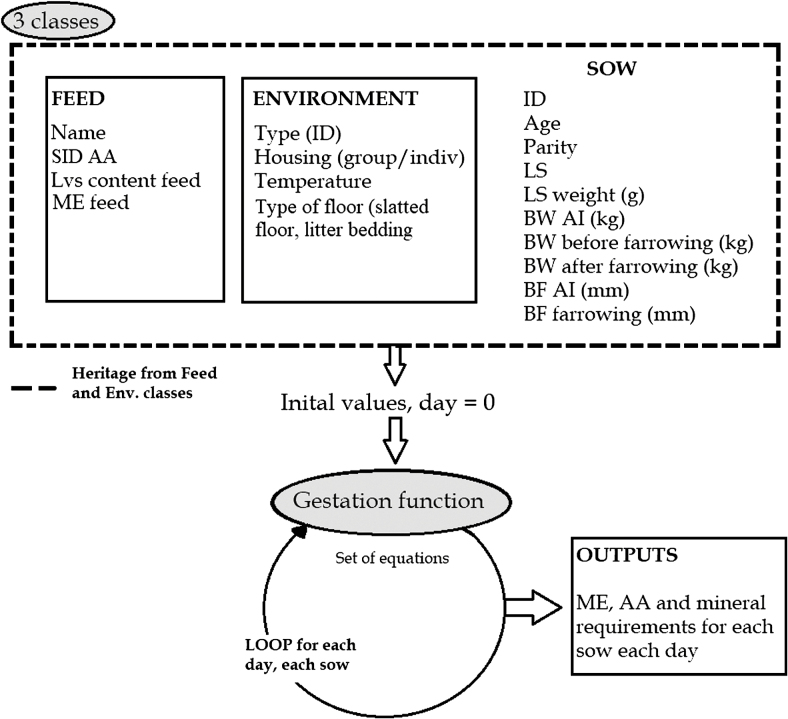

The simulation model was written in Python 3 (Python Software Foundation, Beaverton, Oregon). The Python model was composed of 3 classes (feed, environment, and sow), and 1 gestation function. The gestation function calculated the growth of the different body compartments, and the nutrient requirements (Figure 2) for each day and each sow. The sow class inherited the attributes of the feed and environment classes. The inputs for the feed class were the name of the feed, its ME, and Standardized ileal digestible (SID) AA contents. The inputs for the environment class were the scenario identification number, room temperature, and type of housing. The inputs of the sow class were: identification number, age, parity, LS, average litter BW, sow BW at insemination, sow BW before and after farrowing, and BT at insemination and after farrowing. Two simulations were run with sows housed in groups either at 16 °C in thermoneutral conditions or at 12 °C, i.e., 4 °C below the lower critical temperature (LCT).

Figure 2.

Structure of the Python model used to run the simulations.

Statistical Analysis

For the statistical analysis, the daily data obtained in thermoneutral conditions were averaged into weekly data, and LS was categorized into small (S: LS < 12 piglets), medium (M: 12 ≤ LS < 16 piglets), or large litters (L: LS ≥ 16 piglets). The influence of parity (1, 2, 3+), LS (S, M, L), and gestation weeks (1 to 16) on sow characteristics (BW, BW gain, PROTm, and LIPm), ME, AA, and mineral requirements was analyzed by applying a linear mixed-effect model with the fixed effects of LS, parity, week and their interaction, and the random sow effect. With the R version 3.4.2, the LME function, from the NLME package (Pinheiro et al., 2018), was used to fit the linear mixed-effect models (Laird and Ware, 1982). The correlations over weeks and for each sow were calculated using the temporal corAR1 function, which represents an autocorrelation structure of order 1 (Pinheiro and Bates, 2000). The results are presented in Tables 5 and 6 as means and standard errors for each parity and LS groups, including the P-values to indicate if these 2 factors and their interactions were significant (P < 0.05). When the interactions were not significant, a simplified model without the interactions was applied and the effects were reported in the text (Means ± SE). The week effect was always significant and was therefore not reported in the tables but described as graphs in the results section.

Table 5.

Means and standard errors of metabolizable energy and sows’ composition and mineral requirements regarding litter size and parity, for group-housed sows at 16 °C1

| Parity | 1 | 2 | >2 | SE | P-value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Litter Size | S | M | L | S | M | L | S | M | L | Parity | LS | Parity x LS | |

| Number of sows | 87 | 221 | 84 | 87 | 204 | 98 | 297 | 738 | 695 | ||||

| Metabolizable Energy | |||||||||||||

| MEm, MJ/d | 21.9 | 22.2 | 23.1 | 24.5 | 24.7 | 25.5 | 27.6 | 28.0 | 28.3 | 0.23 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.06 |

| MEc, MJ/d | 0.98 | 1.50 | 1.91 | 1.09 | 1.66 | 2.16 | 1.01 | 1.58 | 2.07 | 0.19 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.41 |

| MEr, MJ/d | 6.92 | 7.10 | 6.19 | 7.11 | 7.24 | 6.84 | 5.99 | 6.02 | 5.93 | 0.49 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.31 |

| MEreq, MJ/d | 29.8 | 30.8 | 31.2 | 32.7 | 33.6 | 34.5 | 34.6 | 35.6 | 36.3 | 0.28 | < 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.82 |

| Body composition and gain | |||||||||||||

| BW, kg | 184 | 187 | 197 | 213 | 216 | 225 | 249 | 255 | 258 | 0.10 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| ADG, g/d | 326 | 394 | 454 | 332 | 413 | 501 | 302 | 387 | 479 | 0.04 | 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.01 |

| LIPM, g/d | 40.3 | 40.8 | 42.9 | 44.9 | 44.9 | 46.4 | 50.4 | 51.2 | 51.5 | 0.08 | < 0.01 | 0.06 | < 0.01 |

| PROTM, g/d | 26.7 | 26.3 | 27.1 | 32.2 | 31.6 | 32.4 | 39.4 | 39.2 | 39.0 | 0.05 | < 0.01 | 0.17 | < 0.01 |

| NR, g/d | 10.8 | 12.4 | 13.2 | 10.2 | 11.8 | 13.3 | 8.24 | 9.58 | 11.2 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| Minerals requirement | |||||||||||||

| STTD-P, g/d | 2.85 | 3.24 | 3.61 | 3.07 | 3.52 | 4.01 | 3.16 | 3.63 | 4.10 | 0.18 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.36 |

| STTD-P, g/kg | 1.23 | 1.36 | 1.48 | 1.21 | 1.35 | 1.49 | 1.18 | 1.31 | 1.45 | 0.07 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.96 |

| Total-Ca, g/d | 8.90 | 10.2 | 11.5 | 9.56 | 11.1 | 12.7 | 9.72 | 11.3 | 12.9 | 0.62 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.35 |

| Total-Ca, g/kg | 3.85 | 4.28 | 4.71 | 3.78 | 4.25 | 4.72 | 3.64 | 4.1 | 4.57 | 0.24 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.97 |

| Ratio Total-Ca/ STTD-P | 3.11 | 3.13 | 3.14 | 3.09 | 3.12 | 3.13 | 3.06 | 3.09 | 3.11 | 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.01 |

1 m, maintenance, c, conceptus, r, maternal reserves, ML, maternal lipids, MP, maternal proteins, Litter Size, S, small litter < 12 piglets, M, average litter < 16 piglets and ≥ 12, L, large litter ≥ 16 piglets, ME, Metabolizable Energy (MJ/d), MEm, ME for maintenance, MEr, ME for maternal body reserves (lipids: ML and proteins: MP), MEc, ME for conceptus (placenta, fetuses, and liquids), MEt, ME for thermoregulation (in this case at 16 °C), NR, Total nitrogen retention (g/d), BW, body weight (kg), BWg, Body weight gain (g/d), PROTM, maternal protein gain (g/d), LIPM, maternal lipid gains (g/d).

Table 6.

Effect of parity and litter size on average SID AA requirement of gestating sows housed in thermoneutral conditions

| Parity1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | SE | P-value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Litter Size | S | M | L | S | M | L | S | M | L | Parity | LS | Parity x LS | |

| AA req., g/d | |||||||||||||

| Lysine | 7.76 | 8.75 | 9.33 | 7.71 | 8.71 | 9.64 | 6.95 | 7.79 | 8.79 | 0.12 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Threonine | 5.79 | 6.51 | 6.89 | 5.73 | 6.45 | 7.09 | 5.14 | 5.73 | 6.43 | 0.09 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Methionine | 2.07 | 2.35 | 2.52 | 2.07 | 2.35 | 2.62 | 1.88 | 2.12 | 2.41 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.06 |

| Cysteine | 3.31 | 3.68 | 3.85 | 3.23 | 3.6 | 3.91 | 2.85 | 3.14 | 3.48 | 0.04 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Tryptophan | 1.67 | 1.86 | 1.96 | 1.65 | 1.84 | 2.01 | 1.47 | 1.63 | 1.82 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Isoleucine | 5.07 | 5.72 | 6.09 | 5.01 | 5.68 | 6.28 | 4.48 | 5.03 | 5.69 | 0.08 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Leucine | 7.85 | 8.78 | 9.33 | 7.85 | 8.79 | 9.67 | 7.19 | 7.99 | 8.93 | 0.11 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Valine | 6.13 | 6.85 | 7.24 | 6.07 | 6.80 | 7.45 | 5.48 | 6.08 | 6.79 | 0.09 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Phenylalanine | 4.75 | 5.33 | 5.66 | 4.73 | 5.31 | 5.84 | 4.29 | 4.78 | 5.35 | 0.07 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Histidine | 2.48 | 2.78 | 2.95 | 2.48 | 2.78 | 3.07 | 2.29 | 2.54 | 2.85 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.06 |

| Arginine | 3.53 | 3.99 | 4.2 | 3.41 | 3.88 | 4.26 | 2.91 | 3.28 | 3.72 | 0.06 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.03 |

| AA req., g/kg | |||||||||||||

| Lysine | 3.35 | 3.65 | 3.82 | 3.04 | 3.34 | 3.57 | 2.60 | 2.82 | 3.10 | 0.04 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.10 |

| Threonine | 2.50 | 2.71 | 2.82 | 2.26 | 2.47 | 2.63 | 1.91 | 2.07 | 2.27 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.07 |

| Methionine | 0.90 | 0.98 | 1.03 | 0.82 | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.70 | 0.77 | 0.85 | 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.14 |

| Cysteine | 1.43 | 1.54 | 1.58 | 1.28 | 1.38 | 1.45 | 1.06 | 1.13 | 1.23 | 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Tryptophan | 0.72 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.65 | 0.71 | 0.75 | 0.55 | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Isoleucine | 2.19 | 2.38 | 2.50 | 1.98 | 2.17 | 2.33 | 1.67 | 1.82 | 2.01 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.09 |

| Leucine | 3.39 | 3.66 | 3.82 | 3.10 | 3.37 | 3.59 | 2.69 | 2.89 | 3.15 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.11 |

| Valine | 2.65 | 2.85 | 2.97 | 2.40 | 2.61 | 2.76 | 2.04 | 2.19 | 2.40 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.07 |

| Phenylalanine | 2.05 | 2.23 | 2.31 | 1.87 | 2.03 | 2.17 | 1.60 | 1.72 | 1.89 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.09 |

| Histidine | 1.07 | 1.16 | 1.21 | 0.98 | 1.07 | 1.14 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.13 |

| Arginine | 1.52 | 1.66 | 1.72 | 1.35 | 1.48 | 1.58 | 1.08 | 1.18 | 1.31 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Ratio Thr/Lys | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.01 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.59 |

1Litter Size: S, small litter < 12 piglets, M, average litter < 16 piglets and ≥ 12, L, large litter ≥ 16 piglets.

The temperature effect on ME, feed, AA, and minerals requirements was evaluated using a similar linear mixed-effects model. The results are reported in Table 7 and in the text as means and standard errors.

Table 7.

Means and standard errors of energy required for thermoregulation, digestible lysine, threonine, STTD-P, and Total-Ca requirements for gestating sows housed in groups at different temperatures (12 vs. 16 °C)

| at 16 °C | at 12 °C | SE | P 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermoregulation, MJ ME/d | 0 | 1.96 | 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| Requirements in g/d | ||||

| Lys, g/d | 8.25 | 8.29 | 0.03 | < 0.01 |

| Thr, g/d | 6.07 | 6.12 | 0.02 | < 0.01 |

| STTD-P, g/d | 3.62 | 3.64 | 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| Total-Ca, g/d | 11.37 | 11.39 | 0.04 | < 0.01 |

| Requirements in g/kg | ||||

| Lys, g/kg | 3.08 | 2.92 | 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| Thr, g/kg | 2.27 | 2.16 | 0.01 | < 0.01 |

| STTD-P, g/kg | 1.35 | 1.28 | 0.51 | < 0.01 |

| Total-Ca, g/kg | 4.23 | 4.01 | 0.01 | < 0.01 |

1Week always had a significant P value (P < 0.01) as described previously.

Cumulative distributions of SID Lys and STTD-P requirements were plotted according to different factors to determine the concentration of SID-Lys and STTD-P needed to meet the requirements of 90% of the sows.

Results

Metabolizable Energy Requirement

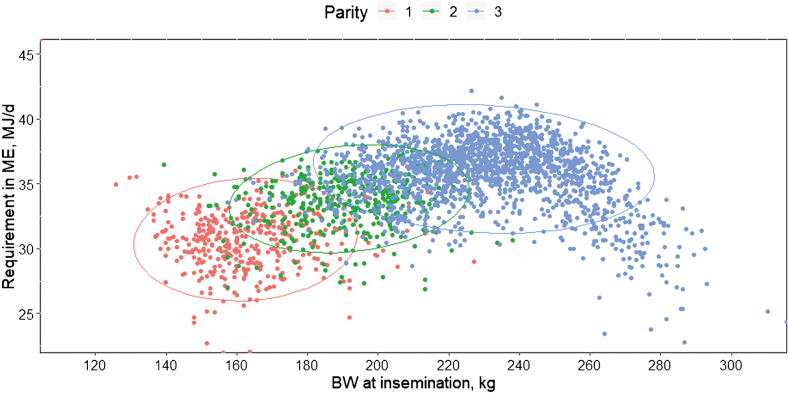

The average ME requirement of sows is influenced by their BW at insemination (P < 0.001), Figure 3) which shows the importance of taking into account individual variability. Sow BW at insemination accounted for 15% of the variability in ME requirement, with an average increase of 0.35 MJ/d ME for a 10-kg increase of BW. Average ME requirement during gestation was also affected by BT at mating (P < 0.001) with an average increase of 0.66 MJ/d ME for each mm decrease in BT at mating, contributing to 67% of the variability. Litter size contributed to 10% of the variability of ME requirement (P < 0.001), with an average increase of 0.29 MJ/d ME for each additional piglet at farrowing.

Figure 3.

Average metabolizable energy requirement of sows as influenced by their body weight at insemination. Each ellipse represents a population of sows from the same parity category (1, 2, or 3+).

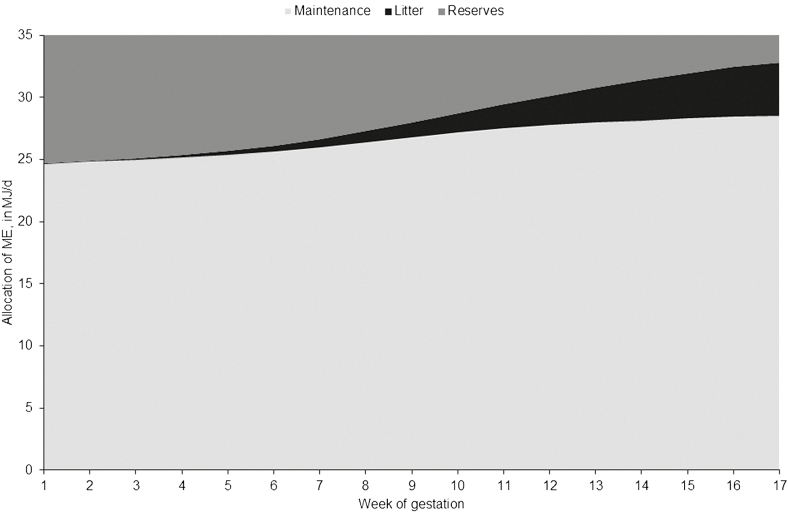

Total ME requirement of sows in thermoneutral conditions increased with increasing parity (30.6, 33.3, and 34.0 MJ/d for parity 1, 2, and 3+, respectively) and with litter size (32.4, 33.3, and 34.0 MJ/d for S, M, and L litters, respectively, Table 5). On average, 76% of the total ME was required for sow’s maintenance, 6% for conceptus, and 18% for maternal reserves. This distribution of ME among the different functions differed according to gestation weeks (Figure 4) and parity. The ME requirement for maintenance increased with parity (on average 22.4, 24.9, and 28.0 MJ/d, respectively, for parity 1, 2, and 3+) and again slightly with LS (on average 24.7, 25.0, and 25.6 MJ/d for S, M, and L, respectively). The ME requirement for conceptus increased during gestation (by about 6 MJ/d from weeks 1 to 17), with increasing LS (on average 1.03, 1.58, and 2.05 MJ/d for S, M, and L litters, respectively) and was higher for parity 2 (1.63 MJ/d) compared with parity 1 and 3+ sows (1.46 and 1.55 MJ/d, respectively). The ME requirement for sow body reserves was higher for parity 2 (7.04 MJ/d) compared with parity 1 and 3+ sows (6.73 and 5.96 MJ/d, respectively), and for sows having M litters (6.77 MJ/d) compared with sows having S and L litters (6.66 and 6.31 MJ/d). The amount of ME remaining for maternal body reserves decreased during gestation, by about −7 MJ/d on average between weeks 1 and 17. Consequently, the average feed allowance needed to meet ME requirement increased with parity (2.39, 2.61, and 2.78 kg/d for parity 1, 2, and 3+, respectively, for a diet containing 13 MJ ME/kg).

Figure 4.

Stacked area chart of the metabolizable energy requirement partitioned between body reserves, conceptus, and maintenance over gestation weeks of group-housed sows at 16 °C in thermoneutral conditions.

When ambient temperature decreased below LCT, daily ME requirement increased by 0.49 MJ/d per degree, which corresponds to a total increase of 1.96 ± 0.18 MJ/d at 12 °C. This corresponded to an increase in daily feed requirement of about 150 g/d (i.e., 2.84 ± 0.04 kg at 12 °C vs. 2.69 ± 0.04 kg at 16 °C, Table 7). It may be noted that this effect was more marked at the end of the gestation period.

SID Lysine Requirement

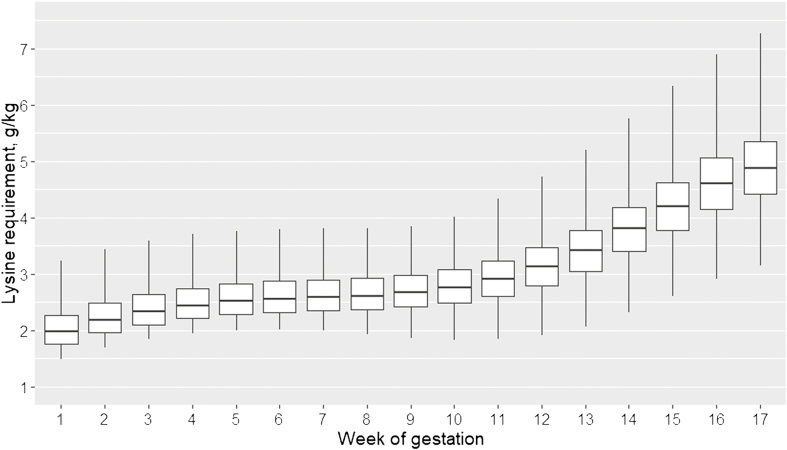

During gestation, AA requirements slightly increased over the first 6 weeks, then plateaued until week 10, and increased again, more steeply this time, until the end of gestation period (Figure 5). Variability increased after week 10 compared with the beginning of the gestation period. Until week 10, between 2.2 and 3.0 g SID Lys per kg of feed met the requirement of 75% of the sows, and 50% of sow AA requirements were satisfied with SID Lys between 2.0 and 2.7 g/kg. Between week 10 and the end of the gestation period SID Lys required to achieve the requirements of 75% of sows increased from 3.0 to 5.4 g SID Lys per kg of feed, the corresponding values to achieve the requirements of 50% of sows were 2.7 and 4.9 g/kg, respectively.

Figure 5.

Boxplots of SID Lysine requirement (in g/kg) of sows for each gestation week receiving on average over the gestation 2.60 kg of feed per day of a diet containing 13 MJ ME/kg.

The variation in daily AA requirements during gestation increased with parity (on average +4.69, +5.18, +5.66 g of SID Lys/d for parity 1, 2, and 3+, respectively, when passing from 30 to 110 d of gestation) and LS (on average +3.71, +5.28, +7.14 g of SID Lys /d for L, M, and L litters, respectively). Overall, SID AA requirement per kg feed increased with LS (SID Lys: 3.00, 3.27, 3.50 g/kg for S, M, L litters, respectively, P < 0.01, Table 6) and decreased when parity increased (SID Lys: 3.61, 3.17, 2.84 g/kg for parity 1, 2, and 3+, respectively, P < 0.01, Table 6).

Changes in other AA requirements per day and per kg of feed according to parity, litter size, and gestation weeks were similar to those observed for SID Lys, due to the rather low variability in the profile of AA requirements (Table 6). The ratio of SID AA requirements per 100 g SID Lys requirement (mean ± SD) was 27.1 ± 0.57 g/100 g for methionine, 66.4 ± 1.27 g/100 g for methionine and cysteine, 21.2 ± 0.36 g/100 g for tryptophan, 74.0 ± 1.38 g/100 g for threonine, 61.5 ± 1.13 g/100 g for phenylalanine, 102.0 ± 1.88 g/100 g for phenylalanine and tyrosine, 102.6 ± 1.87 g/100 g for leucine, 64.8 ± 1.30 g/100 g for isoleucine, 78.6 ± 1.39 g/100 g for valine, 32.6 ± 0.60 g/100 g for histidine, and 42.9 ± 0.84 g/100 g for arginine. These ratios were only slightly, yet significantly, affected by LS and parity as illustrated in Table 6 for Thr/Lys ratio.

When the ambient temperature decreased below 16 °C, the SID AA requirement remained relatively constant per day but decreased per kg of feed. For SID Lys the decrease was 0.04 g/kg per °C below LCT, the effect of temperature being more marked towards the end of the gestation period (Table 7).

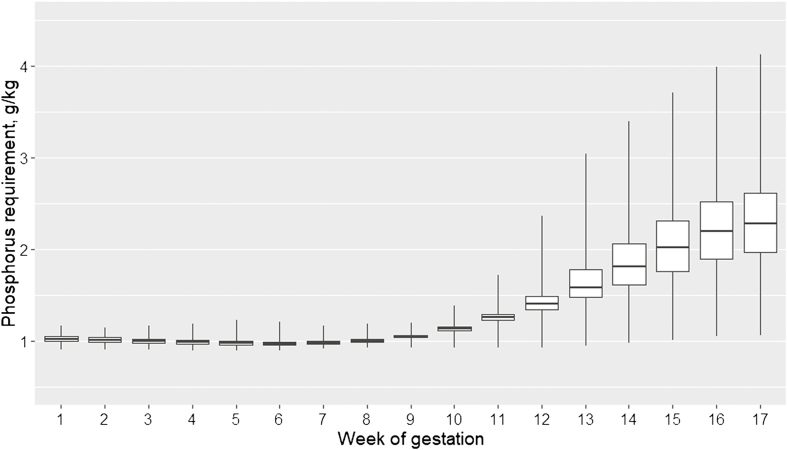

STTD-P and Total Ca Requirements

Total-Ca and STTD-P requirements were low and relatively steady over the first 9 weeks of gestation and markedly increased thereafter (Figure 6). Variability increased after week 10 compared with the beginning of the gestation period. Until week 10, around 1.0 g STTD-P per kg of feed satisfied the phosphorus requirement of the sows with almost no variability week by week. After week 10 and until the end of the gestation period, between 1.2 and 2.6 g STTD-P per kg of feed satisfied the phosphorus requirements of 75% of the sows depending on the week, and 50% of sow phosphorus requirements were satisfied with STTD-P between 1.1 and 2.3 g/kg.

Figure 6.

Boxplots of STTD Phosphorus requirement (in g/kg) of sows for each gestation week receiving on average over the gestation 2.60 kg of feed per day of a diet containing 13 MJ ME/kg.

The extent of the increase in requirement by the end of gestation increased with parity (on average +2.35, +2.73, +3.21 g/d of STTD-P between 30 and 110 d of gestation for parity 1, 2, and 3+, respectively) and litter size (on average +1.60, +2.98, +4.49 g/d of STTD-P between 30 and 110 d of gestation for S, M, and L litters, respectively).

The average STTD-P requirement in g/d increased with increasing LS (Table 5) and increasing parity (on average 3.23, 3.53, 3.63 ± 0.18 g/d for parity 1, 2, and 3+, respectively) while STTD-P requirement in g/kg remained rather constant with increasing parity (on average 1.36, 1.35, 1.35 ± 0.07 g/kg for parity 1, 2, and 3+, respectively). STTD-P requirements for maintenance, growth, and conceptus increased with parity and LS except for maternal growth where they decreased with increasing parity (on average 0.79, 0.76, and 0.67 ± 0.05 g/d for parity 1, 2, and 3+).

Total-Ca requirement and Ca requirements for maintenance, maternal growth, and conceptus increased with LS. Total-Ca requirement (in g/d) and Ca requirement for maintenance increased with parity, whereas Total-Ca requirement (in g/kg) and Ca requirement for maternal growth decreased. Ca requirement for conceptus was higher for parity 2 sows compared with parity 3+ sows; both with higher requirement than parity 1 sows (1.90, 2.12, and 2.01 ± 0.31 g/d, respectively, for parity 1, 2, and 3+).

The Total-Ca/ STTD-P ratio varied between 2.86 and 3.30, with an average of 3.10. This ratio was similar for S and M litters of parity 1 and 2 sows. Moreover, the Total-Ca/STTD-P ratio increased with LS, decreased with parity, and increased during gestation, from around 3.05 from weeks 0 to 9 up to 3.20 on average at week 17.

As for AA requirements, Total-Ca, and STTD-P requirements per kg feed decreased with decreasing temperature (P < 0.01), respectively, by 0.05 and 0.02 g/kg per °C below LCT, on average throughout the entire gestation period. This decrease was more pronounced at the end of the gestation period (Table 7).

Discussion

General Structure of the Model

The modeling approach is based on a combination of current knowledge of nutrient use of gestating sows with the flow of data produced on-farm, in a similar way to the work performed by Gauthier et al. (2019) for lactating sows. The approach considers individual variability in nutrient requirement according to gestation stage, sow characteristics at mating (age, parity, and body condition), and reproductive performance (number and weight of piglet at farrowing). This approach makes it possible to calculate farm specific nutrient recommendations based on their own flow of data.

In the present study, measured individual data were used to obtain LS and piglets birth BW. However, when applying the model in real-time, LS and piglet birth BW will not be available since techniques such as the ultrasound counting of fetuses are not applicable in practice. The alternative will be the development of within-farm predictive models or using data-mining approaches, based on the different criteria that are known to affect prolificacy, such as parity and sow age, prolificacy in previous litters, the duration of the interval between weaning and fertilization, and to a lesser extent the duration of previous lactation. For the future, the use of genomics (Fangmann et al., 2017) might also be an interesting perspective.

Variation in Energy Requirement

Energy requirement varied throughout gestation, with parity and among the different compartments (maintenance, conceptus, maternal lipids, and maternal proteins), which is in accordance with the results of Thomas et al. (2018). The energy requirement for maintenance was the highest throughout gestation. In early- and mid-gestation, energy is used primarily to support maintenance and maternal growth, whereas from around 70 d of gestation the metabolic focus shifts to the growing demands for the conceptus (McPherson et al., 2004) (Figure 4). The fact that energy for protein retention is greater in parity 1 than parity 2 or 3+ sows is mainly due to the higher protein retention potential of these animals that are still growing, and their lower energy requirement for maintenance is due to their lower BW (Dourmad et al., 1999). Pregnant sows are fed restrictively to control their body condition and the risk of reproductive troubles due to insufficient or excessive body fatness (Dourmad, 1994). Therefore, energy allowance during gestation is mainly affected by sow body condition and age or parity at insemination, which accounts for the greatest part of the variability among sows. This is in line with usual practices, at least in some farms, when energy supply is modulated according to parity, body condition (Young et al., 2004), and gestation stage, considering 2 (NRC, 2012; Cloutier et al., 2015) or 3 phases (Clowes et al., 2003), with an increased feed supply in late gestation, and sometimes a decrease in mid gestation. Indeed, when introducing phase feeding, it is necessary to reduce feed intake in early- and/or mid-gestation to accommodate an increase in feed allowance in late gestation (Moehn et al., 2011). Increasing energy allowance in late gestation may improve piglets’ vitality and survival at birth, especially in hyperprolific sows Quiniou et al. (2005), and helps maintaining sows’ body reserves at parturition, whist reducing backfat loss during lactation (Miller et al. 2000). Moreover, Shelton et al. (2009) found that additional feed allowance in late gestation increased the conception rate after weaning. The present model would allow going further, up to an individual adaptation of energy supply considering individual BW and BT at insemination and even when available their evolution along gestation.

Variation in Total-Ca and STTD-P Requirements

During the first two thirds of the gestation period, Total-Ca and STTD-P requirements were low and corresponded to the requirements for maintenance and maternal growth, while during the final third of the gestation period the requirements for these minerals increased, due to the faster growth of the fetuses, and were largely affected by LS. These results are in accordance with previous studies (Jondreville and Dourmad, 2005; NRC, 2012). They show the possibility of a reduction in phosphorus and calcium supplies in early gestation, but this reduction has to be implemented carefully since in our model we do not yet consider the possible requirement for the restoration of body minerals that may have been mobilized during the previous lactation. In the present study, the Total-Ca/ STTD-P ratio (on average of 3.10, and 3.13 and 3.07 in parity 1 and parity 3+, respectively) is slightly lower than the ratio proposed by Jongbloed et al. (2003) (3.3 in parity 1 to 3 sows and 3.5 in higher parities) but close to the ratio calculated by Bikker and Blok 2017 (3.15 in primiparous and 2.9 in multiparous sows). In agreement with the results of Bikker et al. (2017), the Total-Ca/STTD-P ratio increased during gestation because of a higher Total-Ca/ STTD-P ratio in piglets (from 3.15 to 3.30 in parity 1 and from 2.8 to 3.2 in parity 5).

Variation in AA Requirements

The increase in AA requirements in late gestation is in accordance with previous studies (Kim et al., 2009; Levesque et al., 2011) and is due to a change in the demand for nutrients from maternal lean tissue growth in early gestation to fetal and mammary growth in late gestation (McPherson et al., 2004). This important variation suggests the importance of adjusting diet AA content during gestation, at least with the use of a different diet in the final third of the gestation period, instead of feeding a fixed amount of AA throughout the entire gestation period. Indeed, in the case of a diet with a fixed AA content, the sows will be overfed in early gestation, which will increase feed costs and potential environmental impacts due to the excretion of excess nitrogen (Adeola, 1999), whereas they will be underfed in late gestation leading to the possible breakdown of maternal protein tissues to support fetal growth and/or in the case of more severe deficiency to reduced piglets birth weight (McPherson et al., 2004), especially in the case of hyper-prolific sows. In this context, it may thus be relevant to consider combining a change of feeding level and of feed AA composition in late gestation (Goncalves et al., 2016).

Toward a Better Adjustment of AA and P Supplies

In practice, a first step to consider the large variability in AA and P requirements between sows and according to gestation stage is to group sows based on parity and gestation stage.

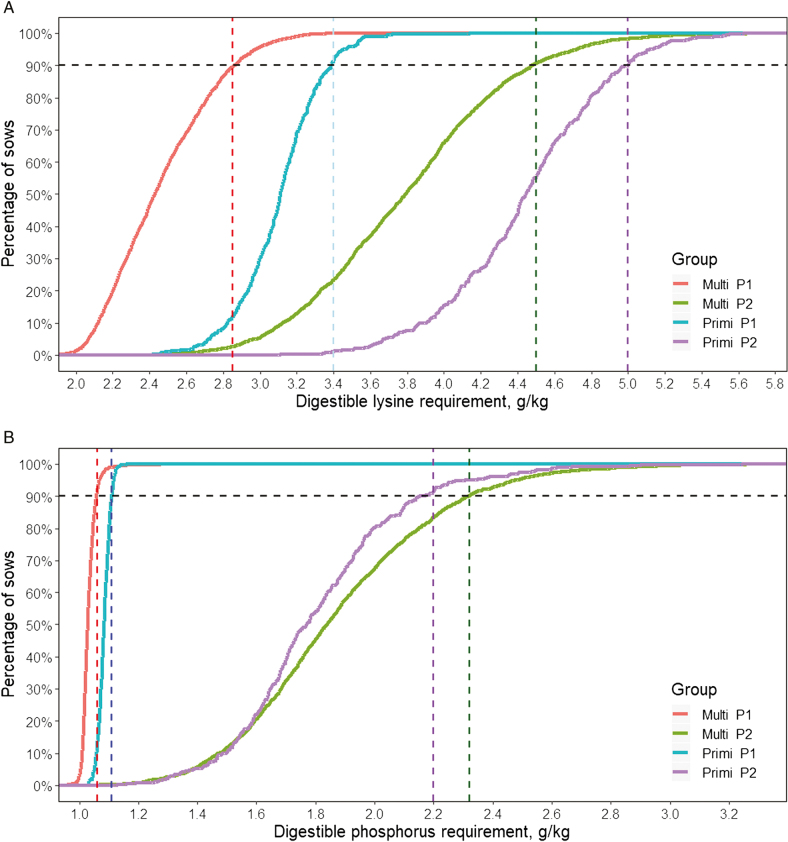

With cumulative distribution plots (Figure 7), we can propose different diets based on parity and gestation periods (P1: weeks 1 to 11; P2: weeks 12 to 17) to feed up to 90% of the sows according to their requirements. When grouping the sows by parity and gestation period, the concentrations of SID Lys needed to satisfy the requirements of 90% of the sows were of 2.8, 3.4, 4.5, and 5.0 g/kg for the multiparous in P1, the primiparous in P1, the multiparous in the P2, and the primiparous in P2, respectively, whereas the concentrations of STTD-P were of 1.1, 2.2, and 3.3 g/kg for all the sows in P1, the multiparous in P2, and the primiparous in P2.

Figure 7.

Cumulative distribution of the SID lysine requirement per kg of feed (a) and the digestible phosphorus requirement per kg of feed (b) according to group (multiparous in P1, multiparous in P2, primiparous in P1, primiparous in P2 with P1 being the period from weeks 0 to 11, and P2 from weeks 12 to 17). These plots can be used to determine the concentrations of SID lysine and digestible phosphorus (STTD-P) needed to satisfy the requirements of 90% of the sows (vertical dotted lines).

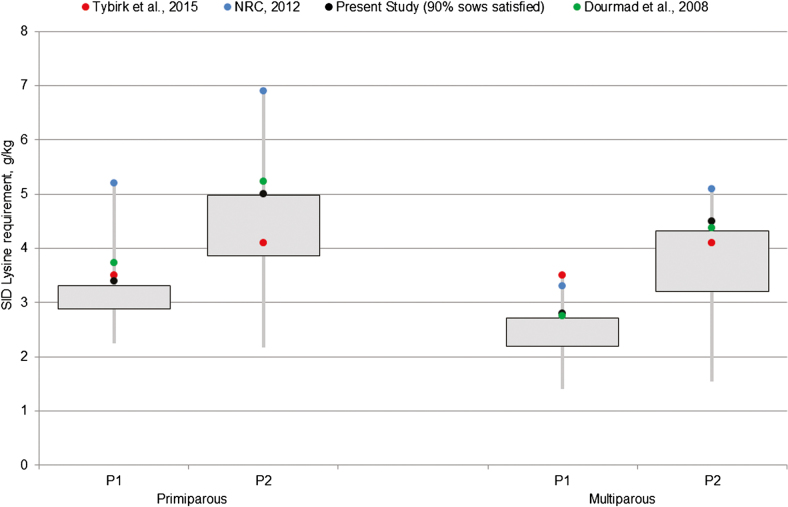

In Figure 8, we compared the SID lysine requirements obtained in the present study with those derived from different recommendations. In general, variability is greater for the late gestation period (P2) compared with the first part of gestation (P1). The NRC (2012) requirements of SID lysine per kg of feed are the highest and above those of the present study. They meet the requirements of all the primiparous sows and of the 99th percentile for multiparous sows, both in P1 and P2. Danish recommendations, which do not differ according to parity (Tybirk et al., 2015), meet the requirements of the 95th, 26th, 100th, and 74th percentile for primiparous P1, primiparous P2, multiparous P1, and multiparous P2, respectively. The requirements calculated from InraPorc (Dourmad et al., 2008) meet the requirements of the 100th, 98th, 82nd, and 88th percentile for primiparous P1, primiparous P2, multiparous P1, and multiparous P2, respectively. They are the closest to our recommendations to feed 90% of the sows up to their requirements. Differences between recommendations are mainly explained by differences in assumptions for SID lysine efficiency or in the definition of early and late gestation. For instance, in the present study, late gestation period starts earlier (77 d) than considered for the other recommendations (i.e., 90, 100, and 108 d for NRC, InraPorc, and the Danish study, respectively) which may account for the higher values in late gestation, as AA requirements increase with gestation days. As regard to Lys efficiency, in NRC (2012) efficiency of SID lysine for pregnancy is 0.47, representing an adjustment to the reference value of 0.75 to account for between animal variations in order to provide a population requirement. In the same way, InraPorc uses a slightly lower efficiency than in the present study (i.e., 0.65 vs. 0.72) but not low enough to take account of between animal variations, especially in multiparous sows.

Figure 8.

Boxplots of SID lysine requirement per kg of feed in gestating sows according to parity and period (early gestation period: P1—and late gestation period: P2—with a day of diet change varying between 77 and 108 depending on the reference). Calculated requirements are compared with recommendations of Dourmad et al. (2008, green dots), NRC (2012, blue dots), Tybirk et al. (2015, red dots) and those of the present study to meet the requirements of 90% of the sows (black dots).

These results underline the need for different diets that vary in AA and mineral composition, according to gestation stage and parity, showing the interest of a multiphase feeding strategy which could easily be set up in practice by grouping the sows according to their parity and gestation stage (early, late) and moving them to the feed line that carries the appropriate ration.

Nevertheless, looking at the huge variability among sows of the same parity group (Figure 5), this phase feeding strategy adapted to each parity would only constitute a first step towards precision feeding. Therefore, the next step will be to allow the mixing of 2 diets with different nutrient levels (high and low) and daily feed allowances, as it has been done for fattening pigs (Pomar et al., 2009; Andretta et al., 2016). From a feed cost point of view, this strategy would also be preferable compared with the multiphase strategy regarding parity, but it would require adapted feeding equipment (Moehn et al., 2011).

Moving forward to a daily individual feeding system using smart feeding and housing equipment could also take benefit of some others factors affecting nutrient requirement, already implemented in the model. For example, the ambient temperature and the activity of each sow could be recorded daily and included in the requirement calculations. Indeed, there is an increase of 10 to 18 kJ ME/kg BW−0.75 per day and per degree Celsius below the LCT and of 0.30 kJ ME/kg BW−0.75/d/min standing (currently fixed at 4-h standing) which almost doubles the instantaneous heat production during standing when compared with lying down (Dourmad et al., 2008). In the context of climate change, the effect of heat stress could also be interesting to consider in the future, although gestating sows are less sensitive to high temperature than lactating sows (Williams et al., 2013). However, this will require some improvements in the model which do consider yet the effects of temperature above the thermoneutral zone. Moreover, as shown by Wegner et al. (2016), the use of a temperature-humidity index (THI) would be more appropriate than temperature alone. For the future, it might also be interesting to modulate the objectives of BW after farrowing according to a specific trajectory for each individual sow, based on their own measured evolution of BW and BT.

All these adjustments will require the farms to be equipped with devices and sensors (weighing scales, cameras, accelerometers, hydro-thermometers, etc.) that continuously record this information to feed real-time databases. It will also require building, based on the present model, a full decision support system that may be embedded in automated feeding equipment.

As indicated by Gauthier et al. (2019), the approach developed in the present study is a contribution to the development of a new type of models that would be “data ready” and “precision-feeding ready,” and able to process both historical farm data (e.g., for ex post assessment of nutrient requirements) and real-time data (e.g., to control precision feeding).

Conclusion

Nutrient requirement is highly variable among sows and throughout gestation. Better considering the high variability of sows’ requirement in practice should thus make it possible to optimize their performance whilst reducing feeding cost. To start with, it can be achieved by grouping and feeding sows according to gestation week and parity. The model of the present study can be used to predict the individual nutrient requirement of sows during gestation and underlines the importance of data recorded on farm in real-time. It also provides an initial step in the development of a decision support system that may be embedded in automated feeding equipment.

Footnotes

This work is supported by Feed-a-Gene, a project that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No. 633531.

Literature Cited

- Adeola O. 1999. Nutrient management procedures to enhance environmental conditions: an introduction. J. Anim. Sci. 77:427–429. doi: 10.2527/1999.772427x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andretta I., Pomar C., Kipper M., Hauschild L., and Rivest J.. . 2016. Feeding behavior of growing-finishing pigs reared under precision feeding strategies. J. Anim. Sci. 94:3042–3050. doi: 10.2527/jas.2016-0392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikker P., and Blok M. C.. . 2017. Phosphorus and calcium requirements of growing pigs and sows. Wageningen:Wageningen Livestock Research. [Google Scholar]

- Cloutier L., Pomar C., Montminy M. P. L., Bernier J. F., and Pomar J.. . 2015. Evaluation of a method estimating real-time individual lysine requirements in two lines of growing-finishing pigs. Animal. 9:561–568. doi: 10.1017/s1751731114003073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clowes E. J., Kirkwood R., Cegielski A., and Aherne F. X.. . 2003. Phase-feeding protein to gestating sows over three parities reduced nitrogen excretion without affecting sow performance. Livest. Prod. Sci. 81:235–246. doi: 10.2527/2003.8161517x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dourmad J. Y., and Etienne M.. . 2002. Dietary lysine and threonine requirements of the pregnant sow estimated by nitrogen balance. J. Anim. Sci. 80:2144–2150. doi: 10.2527/2002.8082144x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dourmad J. Y., Etienne M., Prunier A., and Noblet J.. 1994. The effect of energy and protein intake of sows on their longevity. Livest. Prod. Sci. 40:87–97. doi: 10.1016/0301-6226(94)90039-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dourmad J. Y., Etienne M., Valancogne A., Dubois S., van Milgen J., and Noblet J.. . 2008. InraPorc: a model and decision support tool for the nutrition of sows. Anim. Feed Sci. Tech. 143:372–386. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2007.05.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dourmad J. Y., Noblet J., Père M. C., and Etienne M.. . 1999. Mating, pregnancy and pre-natal growth. In: Kyriazakis I., editor. A quantitative biology of the pig. Wallingford, UK: CAB, pp. 129–153. [Google Scholar]

- Fangmann A., Sharifi R. A., Heinkel J., Danowski K., Schrade H., Erbe M., and Simianer H.. . 2017. Empirical comparison between different methods for genomic prediction of number of piglets born alive in moderate sized breeding populations. J. Anim. Sci. 95:1434–1443. doi: 10.2527/jas.2016.0991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier R., Largouët C., Gaillard C., Cloutier L., Guay F., and Dourmad J. Y.. . 2019. Dynamic modeling of nutrient use and individual requirements of lactating sows1. J. Anim. Sci. 97:2822–2836. doi: 10.1093/jas/skz167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves M. A., Gourley K. M., Dritz S. S., Tokach M. D., Bello N. M., DeRouchey J. M., Woodworth J. C., and Goodband R. D.. . 2016. Effects of amino acids and energy intake during late gestation of high-performing gilts and sows on litter and reproductive performance under commercial conditions. J. Anim. Sci. 94:1993–2003. doi: 10.2527/jas.2015-0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jondreville C., and Dourmad J. Y.. . 2005. Le phosphore dans la nutrition des porcs. INRA Prod. Anim. 18:183–192. [Google Scholar]

- Jongbloed A. W., Diepen J. T. M., and van Kemme P. A.. 2003. Fosfornormen voor varkens: herziening 2003. CVB-documentatierapport nr. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. W., Hurley W. L., Wu G., and Ji F.. . 2009. Ideal amino acid balance for sows during gestation and lactation. J. Anim. Sci. 87:E123–132. doi: 10.2527/jas.2008-1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King R. H., and Brown W. G.. . 1993. Interrelationships between dietary protein level, energy intake, and nitrogen retention in pregnant gilts. J. Anim. Sci. 71:2450–2456. doi: 10.2527/1993.7192450x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird N. M., and Ware J. H.. . 1982. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics 38:963–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque C. L., Moehn S., Pencharz P. B., and Ball R. O.. . 2011. The threonine requirement of sows increases in late gestation. J. Anim. Sci. 89:93–102. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson R. L., Ji F., Wu G., Blanton J. R. Jr, and Kim S. W.. . 2004. Growth and compositional changes of fetal tissues in pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 82:2534–2540. doi: 10.2527/2004.8292534x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller H. M., Foxcroft G. R. and Aherne F. X.. . 2000. Increasing food intake in late gestation improved sow condition throughout lactation but did not affect piglet viability or growth rate. Anim. Sci. 71:141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Moehn S., Franco D., Levesque C., Samuel R., and Ball R. O.. New energy and amino acid requirements for gestating sows. Advances in Pork Production, Volume 22, pg. 10ième WCGALP, abstract 123, Vancouver, Canada, 17–22 août 2014. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Moughan P. 1999. Protein metabolism in the growing pig/ In: I. Kyriazakis, editor. A quantitative biology of the pig. Wallingford:CABI Publishing; p. 299–332. [Google Scholar]

- Noblet J., Henry Y., and Dubois S.. . 1987. Effect of Protein and Lysine Levels in the Diet on Body Gain Composition and Energy Utilization in Growing Pigs. J. Anim. Sci. Biotech. 65:717–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noblet J., Sève B., and Jondreville C.. . 2004. Valeurs nutritives pour les porcs. In: Sauvant D., Perez J.M., and Tran G., editors. Tables of composition and nutritional value of feed materials. The Netherlands:Wageningen Academic Publishers; p. 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- NRC 2012. Nutrient Requirements of Swine: Eleventh Revised Edition. Washington, DC:The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J. C., and Bates D. M.. . 2000. Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-PLUS Springer, esp. pp. 235, 397. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J., Bates D., DebRoy S., Sarkar D., and Team R. C.. 2018. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme NLME: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. R package version 3.1–137.

- Pomar C., Hauschild L., Zhang G. H., Pomar J., and Lovatto P. A.. . 2009. Applying precision feeding techniques in growing-finishing pig operations. Rev. Bras. Zootecn. 38:226–237. doi: 10.1590/S1516-35982009001300023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quiniou N. 2005. Influence de la quantité d’aliment allouée à la truie en fin de gestation sur le déroulement de la mise bas, la vitalité des porcelets et les performances de lactation. Journ. Rech. Porcine, 37, 187–194. http://www.journees-recherche-porcine.com/texte/2005/05Alim/a0503.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Sauvant D., Perez J. M., and Tran G.. . 2004. Tables of composition and nutritional value of feed materials. The Netherlands:Wageningen Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Shelton N. W., DeRouchey J. M., Neill C. R., Tokach M. D., Dritz S. S., Goodband R. D., and Nelssen J. L.. . 2009. Effects of increasing feeding level during late gestation on sow and litter performance. Kansas State University, Manhattan. Swine Day 2009. Report of Progress 1020 [Google Scholar]

- Thomas L. L., Goodband R. D., Tokach M. D., Dritz S. S., Woodworth J. C., and DeRouchey J. M.. . 2018. Partitioning components of maternal growth to determine efficiency of feed use in gestating sows. J. Anim. Sci. 96:4313–4326. doi: 10.1093/jas/sky219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tybirk P. 2015. Nutrient recommendations for pigs in Denmark. Copenhagen, Denmark:SEGES Pig Research Centre; Available at: http://www.pigresearchcentre.dk/~/media/Files/PDF%20- %20UK/Nutrient%20recommendations%20UK.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Van Milgen J., Noblet J., Valancogne A., Dubois S., Dourmad J.Y.. . 2008. InraPorc: a model and decision support tool for the nutrition of growing pigs. Anim. Feed Sci. Tech. 143:387–405. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2007.05.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walker B., and Young B. A.. . 1992. Modeling the development of uterine components and sow body composition in response to nutrient intake during pregnancy. Livest. Prod. Sci. 30:251–264. doi: 10.1016/S0301-6226(06)80014-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner K., Lambertz C., Das G., Reiner G., and Gauly M.. . 2016. Effects of temperature and temperature-humidity index on the reproductive performance of sows during summer months under a temperate climate. Anim. Sci. J. 87:1334–1339. doi: 10.1111/asj.12569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A. M., Safranski T. J., Spiers D. E., Eichen P. A., Coate E. A., and Lucy M. C.. . 2013. Effects of a controlled heat stress during late gestation, lactation, and after weaning on thermoregulation, metabolism, and reproduction of primiparous sows. J. Anim. Sci. 91:2700–2714. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-6055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young M. G., Tokach M. D., Aherne F. X., Main R. G., Dritz S. S., Goodband R. D., and Nelssen J. L.. . 2004. Comparison of three methods of feeding sows in gestation and the subsequent effects on lactation performance. J. Anim. Sci. 82:3058–3070. doi: 10.2527/2004.82103058x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]