Abstract

Enteric methane (CH4) emissions are not only an important source of greenhouse gases but also a loss of dietary energy in livestock. Corn oil (CO) is rich in unsaturated fatty acid with >50% PUFA, which may enhance ruminal biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids, leading to changes in ruminal H2 metabolism and methanogenesis. The objective of this study was to investigate the effect of CO supplementation of a diet on CH4 emissions, nutrient digestibility, ruminal dissolved gases, fermentation, and microbiota in goats. Six female goats were used in a crossover design with two dietary treatments, which included control and CO supplementation (30 g/kg DM basis). CO supplementation did not alter total-tract organic matter digestibility or populations of predominant ruminal fibrolytic microorganisms (protozoa, fungi, Ruminococcus albus, Ruminococcus flavefaciens, and Fibrobacter succinogenes), but reduced enteric CH4 emissions (g/kg DMI, −15.1%, P = 0.003). CO supplementation decreased ruminal dissolved hydrogen (dH2, P < 0.001) and dissolved CH4 (P < 0.001) concentrations, proportions of total unsaturated fatty acids (P < 0.001) and propionate (P = 0.015), and increased proportions of total SFAs (P < 0.001) and acetate (P < 0.001), and acetate to propionate ratio (P = 0.038) in rumen fluid. CO supplementation decreased relative abundance of family Bacteroidales_BS11_gut_group (P = 0.032), increased relative abundance of family Rikenellaceae (P = 0.021) and Lachnospiraceae (P = 0.025), and tended to increase relative abundance of genus Butyrivibrio_2 (P = 0.06). Relative abundance (P = 0.09) and 16S rRNA gene copies (P = 0.043) of order Methanomicrobiales, and relative abundance of genus Methanomicrobium (P = 0.09) also decreased with CO supplementation, but relative abundance (P = 0.012) and 16S rRNA gene copies (P = 0.08) of genus Methanobrevibacter increased. In summary, CO supplementation increased rumen biohydrogenatation by facilitating growth of biohydrogenating bacteria of family Lachnospiraceae and genus Butyrivibrio_2 and may have enhanced reductive acetogenesis by facilitating growth of family Lachnospiraceae. In conclusion, dietary supplementation of CO led to a shift of fermentation pathways that enhanced acetate production and decreased rumen dH2 concentration and CH4 emissions.

Keywords: corn oil, dissolved hydrogen, goat, methane, rumen fermentation, rumen microbes

Introduction

Enteric methane (CH4) emissions from ruminant livestock contribute about 40% of the total greenhouse gases (GHGs) produced from livestock production (Gerber et al., 2013). Methane emissions also represent 2% to 12% of dietary energy waste in ruminants (Johnson and Johnson, 1995; Animut et al., 2008; Bhatta et al., 2012). Therefore, enteric CH4 mitigation may help to decrease GHG concentrations in the atmosphere and improve feed efficiency and livestock productivity. Ruminal microbial fermentation releases metabolic hydrogen ([H]), which can be converted to molecular hydrogen (H2) by hydrogenase and then utilized by methanogens to produce CH4 (Hegarty and Gerdes, 1998). Enteric CH4 mitigation can be achieved by diverting [H] in the rumen away from methanogenesis or by inhibiting rumen microbes involved in methanogenesis (Patra, 2012).

Many oils can effectively reduce methane emissions, while maintaining or improving the productivity of ruminants (Boadi et al., 2004; Beauchemin et al., 2009). Typically, inhibition of methanogenesis is expected to decrease the use of [H], leading to increased ruminal H2 accumulation (Wang et al., 2013). Oil supplementation can decrease ruminal fiber degradation by inhibiting ruminal protozoa (Bhatt et al., 2011), causing a reduction in [H] release. Furthermore, oils may be rich in unsaturated fatty acid (UFA), and biohydrogenation of UFA to SFA can act as an alternative H2 sink and thus may redirect [H] away from methanogenesis (Jenkins et al., 2008). However, the quantitative significance of biohydrogenation as an H2 sink is uncertain (Woodward et al., 2006).

Corn oil (CO) is also rich in UFA with >50% PUFA, which may enhance ruminal biohydrogenation of UFA, leading to a change in ruminal H2 metabolism and methanogenesis. The hypothesis of this study was that CO supplementation of a diet would decrease methanogenesis by altering H2 production and consumption processes accompanied by changes in rumen fermentation, biohydrogenation and microbial community. To test this hypothesis, we used goat as experimental animal and then measured total-tract digestibility of nutrients, enteric CH4 emissions, rumen dissolved gases, rumen fermentation, and microorganisms.

Materials and Methods

Animal and Diets

All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care Committee (Approval number: ISA-Wang-201803), Institute of Subtropical Agriculture, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Changsha, China.

Six healthy female Liuyang Black goats (a local breed in southern of China, 12 ± 0.5 months of age, nonpregnant) with a BW of 19 ± 1.2 (mean ± SD) kg were used in a study designed as a triplicated crossover with 2 consecutive periods. During each period, the goats were randomly allocated to 1 of 2 treatments (3 goats per treatment); control and CO supplementation. The control diet was formulated to supply 1.2 times the DE and CP requirements of nonpregnant female goats according to Zhang and Zhang (1998), and consisted of 50% of rice straw and 50% of concentrate (Table 1). CO (30 g/kg dietary DM) was supplemented to the diet at the expense of soybean meal (15 g/kg) and corn grain (15 g/kg). The ingredients, chemical composition, and long chain fatty acid (LCFA) content of diets are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Ingredients, and chemical and long chain fatty acid (LCFA) composition of the diets

| Diet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Item1 | Control | Corn oil |

| Ingredient, g/kg | ||

| Rice straw | 500 | 500 |

| Concentrate | ||

| Soybean meal | 80.0 | 65.0 |

| Corn grain | 292 | 277 |

| Wheat bran | 98.0 | 98.0 |

| CaCO3 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| CaH2PO4 | 4.00 | 4.00 |

| NaCl | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Premix2 | 20.0 | 20.0 |

| Corn oil3 | 0.00 | 30.0 |

| Chemical composition, g/kg | ||

| OM | 910 | 913 |

| CP | 105 | 99.9 |

| NDF | 468 | 450 |

| ADF | 271 | 262 |

| Starch | 245 | 226 |

| EE | 10.2 | 40.0 |

| GE, MJ/kg | 16.1 | 16.3 |

| Predominant LCFA composition, g/100 g fatty acids | ||

| C16:0 | 20.2 | 15.0 |

| C16:1 | 0.18 | 0.12 |

| C17:0 | 0.39 | 0.20 |

| C18:0 | 2.57 | 1.79 |

| C18 UFA | 73.4 | 81.1 |

| C18:1n9t | 0.11 | 0.13 |

| C18:1n9c | 21.8 | 25.9 |

| C18:2n6c | 48.7 | 53.7 |

| C18:3n3 | 2.73 | 1.31 |

| C20:0 | 0.54 | 0.37 |

| C20:1 | 0.32 | 0.35 |

| C22:0 | 0.36 | 0.17 |

| Other | 2.10 | 0.86 |

| Total UFA | 74.1 | 81.7 |

| Total SFA | 25.9 | 18.2 |

1OM, organic matter; CP, crude protein; NDF, neutral detergent fiber; ADF, acid detergent fiber; EE, ether extract; GE, gross energy; UFA, unsaturated fatty acids; SFA, saturated fatty acids.

2Premix was formulated to provide (per kg of premix): 400 g NaHCO3, 2 g Fe, 1 g Cu, 0.01 g Co, 0.05 g I, 6.6 g Mn, 4.4 g Zn, 0.003 g Se, 333 mg retinol, 5 mg cholecalciferol, 838 mg α-tocopherol.

3The corn oil was supplied by Wilmar International Ltd., Wuhan, China, and was composed of 15% saturated fatty acids, 32% monounsaturated fatty acids, and 53% polyunsaturated fatty acids.

Goats were kept in individual pens and fed at 07:30 and 17:30 hours with equal portions of feed offered at each meal. Each period lasted 25 d, including 14 d of diet adaption, 5 d of feces and urine collection, 4 d of respiration chamber measurements, and 2 d of rumen sampling. Diets were offered ad libitum during the first 7 d of each period to allow the goats to adapt to diets and to measure individual feed intake. From days 8 to 25, DMI was restricted to 100% of the ad libitum DMI of the goats to avoid diet selection. Feed refusals, if present, were collected and measured to determine actual nutrient intake.

Nutrient Digestibility

Nutrient digestibility was measured from days 15 to 19. Total feces were collected by the separator which can separate the feces and urine in the pen and weighed before the morning and afternoon feedings. A subsample (~1%) of feces from each goat was obtained at each collection time and frozen immediately at −20 °C, and another subsample (~1%) was acidified using 10% (w/w) H2SO4 to prevent N loss and then frozen immediately at −20 °C. The subsamples were then individually combined by day and goat within period. Fecal samples were dried at 65 °C for 48 h in a forced-air oven, and ground through a 1-mm screen. The acidified samples were used for total N analysis, whereas non-acidified samples were used for other chemical analysis.

Enteric Methane Emissions

Methane emissions were measured from days 20 to 23 using three plexiglass respiration chambers that permitted the goats to see each other. The emissions were measured individually for each goat as described by Wang et al. (2017). The goats were restrained within the chambers and had free access to a feed bin and drinking water. Airflow through the chamber was controlled by a pump and maintained under negative pressure (flow rate = 35 m3/h). Outlet gas from the chambers and background gas were sampled by the multiport inlet to a gas analyzer (UGGA, Los Gatos Research) for measuring CH4 concentration. The calibration of each chamber is described by Wang et al. (2017). The measurements were cycled every 30 min, with 6 min for analyzing background concentrations of CH4 in incoming air and 8 min for analyzing gases from each of the 3 chambers. Daily CH4 emission was calculated using net CH4 concentration and flow rate of air through each chamber at 30-min intervals. The chambers were opened twice a day at 07:00 and 17:00 hours to deliver the diets, and chambers were cleaned before the morning feeding.

Rumen Sampling

Samples of rumen contents were collected at 0, 2.5, and 6 h after the morning feeding on days 24 and 25. Rumen contents were collected by oral stomach tubing according to the method described by Wang et al. (2016). More than 300 mL of rumen contents were collected, with the initial 100 mL discarded to avoid saliva contamination and the remaining sample used for subsequent measurements. The pH was measured immediately after sampling using a portable pH meter (Starter 300; Ohaus Instruments Co. Ltd, Shanghai, China). Two other subsamples (35 mL each) were immediately transferred into 50-mL plastic syringes for measuring dissolved H2 (dH2) and dissolved CH4 (dCH4) concentrations. Samples of 2 mL of rumen contents were collected and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and then 1.5 mL of supernatant was transferred to 2-mL tubes and acidified with 0.15 mL of 25% (w/v) metaphosphoric acid. The acidified samples were stored at −20 °C for measuring VFA concentrations. Two 10 mL subsamples (not centrifuged) were immediately frozen in liquid N2 and then stored at −80 °C for DNA extraction and microbial analysis. Another two 10 mL subsamples were immediately stored at −20 °C for LCFA measurement. The remaining sample of rumen content was stored at −20 °C for measuring ammonia (NH4+) concentration.

Chemical Analysis

All samples of feeds, refusals, and feces were dried at 65 °C and ground to pass through a 1-mm screen. The DM content was determined by oven drying at 105 °C for 24 h. The OM (method 942.05), CP (method 970.22), and ether extract (EE; method 963.15) were determined according to methods of AOAC (2005). The NDF and ADF were measured by a Fibretherm analyzer (C. Gerhardt Ins., Königswinter, Germany) following the procedures of Van Soest et al. (1991) and expressed as inclusive of residual ash with inclusion of α-amylase (Sigma, Shanghai, China) for NDF. GE was determined using an isothermal automatic calorimeter (5E-AC8018; Changsha Kaiyuan Instruments Co., Changsha, Hunan, China). Starch content was determined after pre-extraction with ethanol (80%), and glucose released from starch by enzyme hydrolysis was measured using amyloglucosidase (Kartchner and Theurer, 1981).

The technique used to extract dCH4 and dH2 from liquid to gas phase is described by Wang et al. (2014). Extracted gaseous CH4 and H2 were analyzed using gas chromatography (GC; Agilent 7890A, Agilent Inc., Palo Alto, CA). Concentrations of dH2 and dCH4 in the original liquid fraction were calculated using equations described by Wang et al. (2016).

Individual VFA concentrations were analyzed using GC according to the procedure of Wang et al. (2016). Ammonia concentration was measured using the procedure of Shahinian and Reinhold (1971). For LCFA composition determination, feedstuffs were processed in the state obtained, while rumen contents were freeze-dried (CHRIST RVC2-25 CDPIUS, Marin Christ CO., Ltd, Osterode, Germany). About 200 mg of sample was placed into 15.5 mL Pyrex screw-cap culture tubes that contained 0.7 mL of 10 N KOH in water and 5.3 mL of methanol. The tubes were incubated in a water bath at 55 °C for 1.5 h and hand-shaking vigorously for 5 s every 20 min, cooled in a water bath to below room temperature, 0.58 mL of 24 N H2SO4 in water was added, and samples were mixed by inversion to precipitate the K2SO4 present. Samples were incubated again in a water bath at 55 °C for 1.5 h, hand-shaking vigorously for 5 s every 20 min, then cooled in a water bath to below room temperature, 3 mL of hexane was added and tubes were vortex mixed for 5 min. Tubes were centrifuged for 5 min at 1,500 × g, and the hexane layer containing fatty acid methyl esters was transferred into a vial and stored at −20 °C until analysis. Individual LCFA composition of the fatty acid methyl esters was analyzed according to the direct fatty acid methyl esters synthesis procedure described by O’Fallon et al. (2007).

Microbial Analyses

Rumen samples collected 2.5 h after the morning feeding were freeze-dried (CHRIST RVC2-25 CDPIUS, Marin Christ CO., Ltd, Osterode, Germany) for microbial analysis. The DNA was extracted with repeated bead beating plus column purification as described by Yu and Morrison (2004), and eluted by 300 μL TE buffer (Tris 10 mmol/L, EDTA 1 mmol/L, pH = 8.0). The quality and quantity of DNA was measured based on absorbance at 260 and 280 nm using a NanoDrop ND-2000 (NanoDrop Technologies Inc., Wilmington).

The 16S rRNA V3–V4 hypervariable regions of the bacteria genomic DNA were used for PCR amplification with the primers 5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3″ (338F) and 5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′ (806R) (Wang et al., 2017), while the 16S rRNA V4–V5 hypervariable regions of the methanogen genomic DNA were used for PCR amplification with the primers 5′-TGYCAGCCGCCGCGGTAA-3′ (524F) and 5′-YCCGGCGTTGAVTCCAATT-3′ (Arch958R) (Ma et al., 2018). The PCR reactions were performed in triplicate using a 20-μL mixture containing 0.8 μL of each primer (10 μmol/L), 10 ng of template DNA, 2 μL 2.5 mM dNTPs, 0.4 μL of FastPfu polymerase (Transgen, Beijing, China) and 4 μL 5 × FastPfu Buffer (Transgen). The thermal cycling programing was performed as follows: initial denaturation step, 95 °C, 3 min; denaturation, 27 cycles, 95 °C, 30 s; annealing, 55 °C, 30 s; elongation, 72 °C, 45 s; and final extension, 72 °C, 10 min. The PCR products were excised from 2% agarose gels and purified using a QIAquick Gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The 16S rRNA library was prepared according to the instructions provided with Nextera XT Index kits (Illumina, San Diego, CA). A unique 10-base barcode was added at the 5′ end of each amplicon as well as to Illumina adapter sequences. Amplicons from each reaction mixture were quantified using QuantiFluorTM–ST system (Promega, Madison, WI), and pooled at equimolar ratios based on the concentration of each amplicon. Amplicons were sequenced with the Illumina MiSeq platform (PE300) at the Majorbio Bio-Pham Technology, Shanghai, China. MOTHUR v.1.39.5 (Schloss et al., 2009) was used for quality control of the sequence reads following the protocol described by Kozich et al. (2013). Quality filters were applied to trim raw sequences according to the following criteria: (i) reads with average quality score < 20 over a 10-bp sliding window were removed, and truncated reads shorter than 150 bp were discarded. (ii) Truncated reads containing homopolymers longer than 8 nucleotides, more than 0 base in barcode matching, or more than 2 different bases to the primer were removed from the dataset. The possible chimeras were checked and removed via USEARCH using the ChimeraSlayer “gold” database as described by Edgar et al. (2011). The average reads per sample used for operational taxonomic unit (OTU) determination of bacteria and Archaea was 25,184 ± 3,490.0 (Supplementary Fig. S1) and 29,991 ± 6,098.9 (Supplementary Fig. S2), respectively. The high-quality reads were clustered into OTU at 97% similarity using USEARCH (Edgar, 2013), and representative sequences defined by abundance from each OTU were identified using PyNAST (Caporaso et al., 2010) against SILVA database v.128 for bacteria and archaea (Quast et al., 2013). Taxonomy analysis was performed using RDP classifier v.11.1 with a minimum support threshold of 80% (Wang et al., 2007). α diversity analyses were generated by MOTHUR v.1.39.5 (Schloss et al., 2009), including observed species, Chao, Ace, Shannon-Weiner, and Simpson’s indices. All 16S rRNA gene sequences were deposited into the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under accession number PRJNA494452 for bacteria and PRJNA494459 for methanogen.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed according to the procedures detailed by Jiao et al. (2014). In brief, the plasmid DNA containing exact 16S or 18S rRNA gene inserts were used to make a standard curve for each group and individual species. All standard curves met the following requirements: R2 > 0.99 and 90% < E < 120%. Forward and reverse primers selected from the literature for qPCR groups are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Statistical Analysis

Data were subjected to analysis using the SPSS 19.0 software. Fermentation and CH4 emissions data were averaged to obtain a mean value for the 2 consecutive days before further analysis. The normal distribution of our data was checked with normality test (Kolmogorov-Smirnov). The data followed normal distribution were analyzed according to the following procedures. Data of nutrient digestibility, CH4 emissions, qPCR, alpha diversity indexes, and relative abundance estimated from 16S rRNA gene library sequences were analyzed using a linear mixed model that included dietary treatment (n = 2) as fixed effect, and period (n = 2) and goat (n = 6) as random effects. Data of ruminal samples were analyzed using a linear mixed model with treatment (n = 2) and treatment by sampling time interaction as fixed effects, goat (n = 6) and period (n = 2) as random effects, and sampling time (n = 3) as a repeated measurement. For the data that not follow a normal distribution, the permutation test was run by R with linear mixed models (package minque, permutation number = 999; https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/minque/index.html) as descripted by Wu (2012) according to MINQUE theory (Rao, 1971). Significance was considered when P ≤ 0.05, and 0.05 < P ≤ 0.1 was accepted as a tendency to significance.

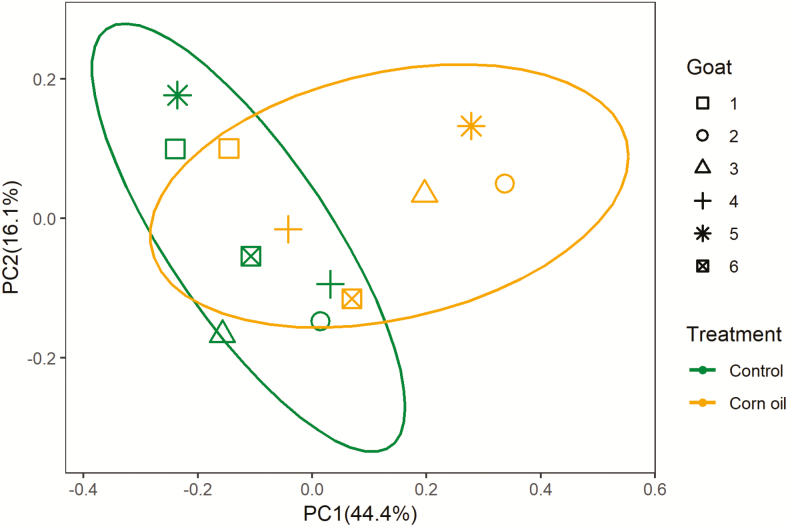

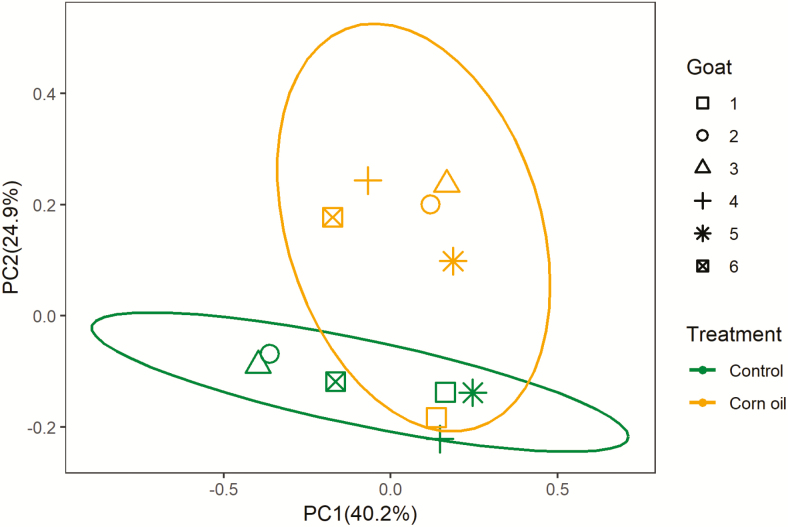

A principal coordinate analysis was performed in MOTHUR v.1.39.5 (Schloss et al., 2009) at OTU level according to 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequence data based on Bray–Curtis similarity distances (Bray and Curtis, 1957) to test the treatment and goat effects on bacteria and methanogens community structure. Data were then analyzed by nonparametric permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) based on 9,999 permutations with treatment (n = 2) and goat (n = 6) as fixed effects (R statistics; Vegan package 2.4–4; Function adonis; Oksanen et al., 2017).

Results

Total-Tract Digestibility and Methane Emissions

CO supplementation had no effect on the DMI (P = 0.29), decreased (P < 0.001) total-tract digestibility of starch, tended to increase NDF digestibility (P = 0.08), and decreased CH4 emission expressed as g/d (−15.0 %, P = 0.003), g/kg DMI (−15.1%, P = 0.003), g/kg OM digested (−10.8%, P = 0.07), g/kg NDF digested (−11.9%, P = 0.043), and MJ/MJ GE intake (−18.1%, P < 0.001; Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of corn oil supplementation on nutrient intake, digestibility, and enteric methane emissions in goats (n = 6)

| Treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item1 | Control | Corn oil | SEM2 | P-value |

| DMI, g/d | 472 | 478 | 4.4 | 0.29 |

| Digestibility, % | ||||

| DM | 67.2 | 67.7 | 0.94 | 0.57 |

| OM | 70.3 | 70.2 | 1.38 | 0.90 |

| CP | 63.9 | 63.6 | 2.30 | 0.93 |

| NDF | 56.6 | 58.9 | 2.17 | 0.07 |

| Starch | 97.8 | 97.0 | 0.25 | <0.001 |

| GE | 66.2 | 67.0 | 0.92 | 0.43 |

| Methane emission | ||||

| g/d | 8.45 | 7.18 | 0.55 | 0.003 |

| g/kg DMI | 17.9 | 15.2 | 1.15 | 0.003 |

| g/kg OM digested | 27.9 | 24.9 | 1.77 | 0.07 |

| g/kg NDF digested | 74.2 | 65.4 | 5.65 | 0.08 |

| MJ/MJ GE intake, % | 6.14 | 5.03 | 0.39 | <0.001 |

1DMI, dry matter intake; DM, dry matter; OM, organic matter; CP, crude protein; NDF, neutral detergent fiber; GE, gross energy.

2SEM is pooled standard error of means.

Rumen Fermentation

CO supplementation decreased (P < 0.001) UFA proportion and increased (P < 0.001) SFA proportion in rumen fluid (Table 3). For individual UFA and SFA, CO supplementation decreased proportion of C18:1n9c (P = 0.007), C18:2n6c (P < 0.001), C20:1 (P = 0.001), and C20:4n6 (P < 0.001), and increased (P < 0.001) proportion of C18:0. No interaction effect between treatment and sampling time on rumen LCFA profile was found.

Table 3.

Effect of corn oil supplementation on long chain fatty acid profile (g/100 g fatty acid) in the rumen content of goats (n = 6)

| Treatment | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item1 | Control | Corn oil | SEM2 | Treatment | Time | Treatment × time |

| C14:0 | 5.78 | 2.65 | 0.39 | <0.001 | 0.54 | 0.96 |

| C16:0 | 30.1 | 24.6 | 0.43 | <0.001 | 0.35 | 0.59 |

| C16:1 | 1.48 | 0.81 | 0.07 | <0.001 | 0.82 | 0.70 |

| C17:0 | 1.94 | 1.08 | 0.11 | <0.001 | 0.83 | 0.35 |

| C18:0 | 33.3 | 47.2 | 1.07 | <0.001 | 0.06 | 0.31 |

| C18 UFA | 25.0 | 22.5 | 0.80 | 0.011 | <0.001 | 0.29 |

| C18:1n9t | 9.62 | 12.8 | 0.57 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.16 |

| C18:1n9c | 7.16 | 5.26 | 0.68 | 0.007 | <0.001 | 0.42 |

| C18:2n6c | 7.68 | 4.24 | 0.54 | <0.001 | 0.026 | 0.58 |

| C18:3n3 | 0.58 | 0.22 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.33 | 0.89 |

| C20:0 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.03 | 0.48 | 0.022 | 0.73 |

| C20:1 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.001 | 0.28 | 0.36 |

| C20:4n6 | 1.69 | 0.61 | 0.18 | <0.001 | 0.50 | 0.94 |

| Others | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.28 | 0.36 |

| Total UFA | 28.4 | 24.0 | 0.79 | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.29 |

| Total SFA | 71.6 | 76.0 | 0.79 | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.29 |

1UFA, unsaturated fatty acids; SFA, saturated fatty acids.

2SEM is pooled standard error of means.

CO supplementation decreased pH (P < 0.001), dH2 (−33.3%, P < 0.001), and dCH4 (−33.8%, P < 0.001) concentration, and increased (+17.2%, P = 0.043) ammonia-N concentration in rumen fluid (Table 4). There was an increase in total VFA concentration (P = 0.027), molar percentage of acetate (P < 0.001) and isobutyrate (P < 0.001), and acetate to propionate ratio (P = 0.038), and decreased molar percentage of propionate (P = 0.015), valerate (P < 0.001), and isovalerate (P < 0.001) with CO supplementation. No interaction effect between treatment and sampling time on rumen fermentation characteristics was found.

Table 4.

Effect of corn oil supplementation on metabolites in the rumen of goats (n = 6)

| Treatment | P-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Control | Corn oil | SEM1 | Treatment | Time | Treatment × time |

| pH | 6.56 | 6.38 | 0.02 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.22 |

| Dissolved gas | ||||||

| Hydrogen, µmol/L | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.035 | 0.11 |

| Methane, mmol/L | 1.33 | 0.87 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.20 | 0.26 |

| Ammonia-N, mmol/L | 6.38 | 7.48 | 1.72 | 0.043 | <0.001 | 0.23 |

| VFA2, mmol/L | 77.6 | 85.0 | 3.52 | 0.027 | 0.09 | 0.60 |

| Acetate to propionate ratio | 3.45 | 3.82 | 0.33 | 0.038 | 0.31 | 0.88 |

| Molar percentage of individual VFA, mol/100 mol | ||||||

| Acetate | 69.5 | 72.2 | 1.89 | <0.001 | 0.73 | 0.83 |

| Propionate | 20.2 | 18.9 | 1.51 | 0.015 | 0.07 | 0.86 |

| Butyrate | 7.22 | 6.39 | 0.73 | 0.07 | 0.40 | 0.77 |

| Isobutyrate | 0.81 | 1.10 | 0.09 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.12 |

| Valerate | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.08 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.75 |

| Isovalerate | 1.39 | 1.18 | 0.11 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.14 |

1SEM is pooled standard error of means.

2VFA, volatile fatty acid.

Rumen Microbial Community

CO supplementation had no effect on bacterial richness expressed as Chao and Ace scores (Table 5). Goats fed a diet supplemented with CO had a greater Shannon index (P = 0.048) and tended to have increased observed OTUs (P = 0.10). Goats had distinct separation of bacterial community (P = 0.009), and CO supplementation altered bacterial community of each individual goat (Fig. 1). CO supplementation decreased relative abundance of family Bacteroidales_BS11_gut_group (P = 0.032) and increased relative abundance of family Rikenellaceae (P = 0.021) and Lachnospiraceae (P = 0.025) (Table 5). CO supplementation tended to increase relative abundances of genus Butyrivibrio_2 (P = 0.06) and Prevotellaceae_UCG-001 (P = 0.06), and tended to decrease relative abundance of genus Ruminococcus_2 (P = 0.06). The relative abundances of other major bacterial groups are supplied in Supplementary Table S2, with relative abundance >0.5% and P > 0.10 between treatments at genus level.

Table 5.

Effect of corn oil supplementation on α diversity and bacterial groups (relative abundance >0.5%, P ≤ 0.10 between treatments at genus level) in the rumen of goats (n = 6)

| Treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Control | Corn oil | SEM2 | P-value |

| α diversity index | ||||

| Observed OTUs | 792 | 837 | 65.8 | 0.10 |

| Shannon | 4.17 | 4.59 | 0.11 | 0.048 |

| Simpson | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.011 | 0.12 |

| Chao | 716 | 729 | 16.5 | 0.34 |

| Ace | 707 | 726 | 15.8 | 0.21 |

| Relative abundances assessed by amplicon sequences1, % | ||||

| f__Prevotellaceae | 33.1 | 29.9 | 6.37 | 0.66 |

| g__Prevotellaceae_UCG-001 | 0.69 | 1.72 | 0.081 | 0.06 |

| f__Bacteroidales_BS11_gut_group | 16.3 | 8.49 | 1.701 | 0.032 |

| g__norank_f__Bacteroidales_BS11_gut _group | 16.3 | 8.49 | 1.701 | 0.032 |

| f__Ruminococcaceae | 13.2 | 15.3 | 2.43 | 0.47 |

| g__Ruminococcus_2 | 0.79 | 0.44 | 0.111 | 0.06 |

| g__Ruminococcaceae_UCG-002 | 0.47 | 1.14 | 0.299 | 0.09 |

| f__Rikenellaceae | 4.45 | 8.05 | 1.478 | 0.021 |

| g__unclassified_f__Rikenellaceae | 1.09 | 2.38 | 0.315 | 0.07 |

| f__Lachnospiraceae | 6.11 | 7.99 | 1.263 | 0.025 |

| g__Butyrivibrio_2 | 0.21 | 0.73 | 0.155 | 0.06 |

1f_, family; g_, genus.

2SEM is pooled standard error of means.

Figure 1.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) plots of the Bray–Curtis dissimilarities for the bacterial community of rumen samples (treatment, P = 0.18; goat, P = 0.009; n = 12). Percentages of data variation explained by the analysis are shown on the axes. Green ellipse represents the control group, orange ellipse represents the corn oil treatment, and the confidence interval is 95%.

CO supplementation had no effect on methanogen richness expressed as Shannon index, Chao and Ace, decreased the observed OTUs (P = 0.026) and tended to increase Simpson index (P = 0.06) (Table 6). Goats had distinct separation of methanogen community (P = 0.041), and CO supplementation altered methanogen community of each individual goat (Fig. 2). CO supplementation increased (P = 0.033) relative abundance of order Methanobacteriales and tended to decrease (P = 0.09) relative abundance of order Methanomicrobiales. CO supplementation increased (P = 0.012) relative abundance of genus Methanobrevibacter and tended to decrease (P = 0.09) relative abundance of genus Methanomicrobium. The relative abundances of other major methanogen groups are supplied in Supplementary Table S3, with relative abundance >0.5% and P > 0.10 between treatments at genus level.

Table 6.

Effect of corn oil supplementation on α diversity and methanogens groups (relative abundance >0.5%, P ≤ 0.10 between treatments at genus level) in the rumen of goats (n = 6)

| Treatment | – | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Control | Corn oil | SEM2 | P-value |

| α diversity index | ||||

| Observed OTUs | 150 | 134 | 14.1 | 0.026 |

| Shannon | 1.70 | 1.57 | 0.141 | 0.13 |

| Simpson | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.039 | 0.06 |

| Chao | 53.2 | 64.8 | 9.40 | 0.25 |

| Ace | 63.8 | 67.4 | 11.62 | 0.58 |

| Relative abundances assessed by amplicon sequences1, % | ||||

| o__Methanobacteriales | 65.4 | 82.8 | 7.80 | 0.033 |

| g__Methanobrevibacter | 59.3 | 79.9 | 6.36 | 0.012 |

| o__Methanomicrobiales | 23.7 | 8.00 | 5.940 | 0.09 |

| g__Methanomicrobium | 23.7 | 8.00 | 5.940 | 0.09 |

1o_, order; g_, genus.

2SEM is pooled standard error of means.

Figure 2.

PCoA plots of the Bray–Curtis dissimilarities for methanogen community of rumen samples (treatment, P = 0.21; goat, P = 0.041, n = 12). Percentages of data variation explained by the analysis are shown on the axes. Green ellipse represents the control group, orange ellipse represents the corn oil treatment, and the confidence interval is 95%.

CO supplementation had no effect on the 16S/18S rRNA/ ITS1 gene copies of total bacteria and methanogens, fungi, and protozoa, respectively, but it showed a tendency to decrease the 16S rRNA gene copies of Ruminobacter amylophilus (P = 0.08) and decreased 16S rRNA gene copies of Methanomicrobiales (P = 0.043), and tended to increase 16S rRNA gene copies of Methanobacteriales (P = 0.09) and Methanobrevibacter (P = 0.08; Table 7).

Table 7.

Effect of corn oil supplementation on selected microbial groups (log10 copies/g DM rumen contents) in the rumen of goats (n = 6)

| Treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item1 | Control | Corn oil | SEM2 | P-value |

| Bacteria | 13.6 | 13.6 | 0.08 | 0.80 |

| Fungi | 10.3 | 10.2 | 0.17 | 0.44 |

| Protozoa | 10.2 | 10.2 | 0.23 | 0.83 |

| Methanogens | 11.9 | 11.9 | 0.09 | 0.92 |

| Selected groups of bacteria | ||||

| Prevotella | 13.1 | 13.1 | 0.08 | 0.77 |

| Fibrobacter succinogenes | 10.7 | 10.9 | 0.22 | 0.45 |

| Ruminococcus albus | 9.83 | 10.1 | 0.17 | 0.12 |

| Ruminococcus flavefaciens | 10.0 | 9.96 | 0.13 | 0.76 |

| Ruminobacter amylophilus | 11.1 | 10.8 | 0.14 | 0.08 |

| Selected groups of methanogens | ||||

| Methanobacteriales | 11.1 | 11.5 | 0.19 | 0.09 |

| Methanobrevibacter | 10.2 | 10.4 | 0.12 | 0.08 |

| Methanomicrobiales | 9.23 | 9.04 | 0.26 | 0.043 |

116S rRNA gene copies were measured for bacteria and methanogen, 18S rRNA gene copies were measured for protozoa, and the multiple alignments of 18S rRNA and ITS1 gene copies were measured for fungi.

2SEM is pooled standard error of means.

Discussion

Unsaturated fatty acid of oil is toxic to rumen microbes (Maia et al., 2007), and increased UFA intake may lead to an inhibition of fiber digestion (McGinn et al., 2004). Studies have reported that oil supplementation of diets can negatively affect nutrient digestibility (especially fiber digestibility) in dairy and beef cattle (50 g/kg DM sunflower oil; McGinn et al., 2004; 40 g/kg DM linseed oil; Benchaar et al., 2015). In our study, CO supplementation of diets fed to goats did not alter OM digestibility with a tendency for increased NDF digestibility and decreased starch digestibility. The dose of CO supplementation (30 g/kg DM) may not have been high enough to negatively affect fiber digestibility. Furthermore, the different LCFA composition among oils might be another possible explanation. For example, C18:3 fatty acids have greater toxicity than other fatty acids for the ruminal microbes (Maia et al., 2007). CO has lower C18:3 fatty acids (0.7%), which may have less effect on major fiber degraders and fiber digestibility.

The rumen has a wide-range of fibrolytic microbial groups that degrade fiber. Fungi, protozoa, and fibrolytic bacteria (i.e., Ruminococcus albus, Ruminococcus flavefaciens, and Fibrobacter succinogenes) are active fiber degraders (Wang and McAllister, 2002). Yang et al. (2009) reported that linseed oil (40 g/kg DM) supplementation inhibited R. flavefaciens in dairy cows. Patra and Yu (2013) reported that coconut oil supplementation (6.2 mL/L culture fluid) decreased NDF degradation by inhibiting R. flavefaciens and F. succinogenes during in vitro ruminal fermentation. In the present study, CO supplementation did not alter population density of the major fiber degraders, which is consistent with the lack of negative effects on digestibility.

Oil supplementation can inhibit rumen methanogenesis. Puchala et al. (2018) found that coconut oil and soybean oil supplementation (40 g/kg DM) can reduce 34% and 32% of CH4 emissions in goat, respectively. Machmüller et al. (2003) reported that coconut oil (50 g/kg DM) could reduce 14% of CH4 emissions in sheep. We observed that 30 g CO/kg DM supplementation reduced CH4 emissions by 10.8% (g/kg OM digested) to 18.1% (MJ/MJ GE intake), depending upon how CH4 was expressed. Moreover, the observed reduction in methanogenesis is further supported by the decreased ruminal dCH4 concentration. Oil supplementation can inhibit ruminal fermentation, decrease protozoa and provide an alternative H2 sink redirecting [H] away from methanogenesis (Johnson and Johnson, 1995). In the present study, CO supplementation did not alter OM digestibility or 18S rRNA gene copies of protozoa, but increased VFA concentration, indicating that the reduction in CH4 emissions was unlikely caused by decreased ruminal substrate fermentation or by the inhibition of protozoa growth. Machmüller et al. (2003) have also reported that the inhibited methanogenesis with coconut oil supplementation is not caused by the depression of protozoa population in sheep.

Unsaturated fatty acids in oil utilize [H] during the ruminal biohydrogenation process and thus can compete H2 away from methanogenesis (Jenkins et al., 2008). The UFA concentration in the CO diet was greater than that in the control diet. However, goats fed the CO diet had greater SFA proportion in rumen contents than those fed the control diet, indicating that CO consumed [H] by facilitating ruminal UFA biohydrogenation for SFA synthesis. Loor et al. (2004) found greater ruminal biohydrogenation in dairy cows fed a diet supplemented with linseed oil (30 g/kg DM). Furthermore, the decreased dH2 concentration also indicated that CO supplementation enhanced H2 consumption by incorporating [H] for UFA biohydrogenation. The predominant LCFA is C16 and C18 fatty acids, which accounted for more than 85% of total LCFA in this study. Goats fed CO had lower total or individual C18 UFA (such as C18:1n9c, C18:2n6c, and C18:3n3) than those fed the control diet, indicating an enhancement of biohydrogenation. Studies have reported that beef steers fed a diet with greater oil content had greater biohydrogenation of total and individual C18 UFA than those fed a control diet (Bolte et al., 2001; Duckett et al., 2002).

Oil supplementation can affect rumen fermentation profile. Benchaar et al. (2015) reported that linseed oil supplementation (40 g/kg DM) increased propionate production at the expense of acetate in dairy cows. Gonthier et al. (2004) demonstrated that flaxseed supplementation (126 g/kg DM) decreased acetate and increased propionate percentage. However, such changes in VFA profiles are not always observed with oil feeding. For instance, Machmüller et al. (2003) observed that coconut oil (50 g/kg) supplementation of diets increased acetate-to-propionate ratio in sheep. In our study, CO supplementation increased acetate and decreased propionate molar percentage in goats, and such facilitation of acetate production was consistent with the observed low ruminal dH2 concentration in the rumen of the goats. Janssen (2010) stated that H2 forming pathways have more negative Gibbs free energy changes at low dH2 concentration. Acetate generation is thermodynamically favorable under low ruminal H2 partial pressure, which facilitates H2 generation through acetate production (Martinez-Fernandez et al., 2017). Furthermore, acetate can be produced from H2 and carbon dioxide (4H2 + 2CO2 → CH3COOH + 2H2O) through the acetyl-CoA pathway by acetogens, such as family Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae (Gagen et al., 2015). CO supplementation increased relative abundance of family Lachnospiraceae and acetate molar percentage, indicating that reductive acetogenesis might have played a role in H2 consumption, and may have contributed to the decrease in dH2 concentration and CH4 emissions.

CO supplementation altered some groups of bacteria related to biohydrogenation, H2-production, and H2-utilization. Genus Butyrivibrio and some unknown genera within the family Lachnospiraceae are the most important biohydrogenating bacteria (Boeckaert et al., 2008), especially for C18 biohydrogenation (Van de Vossenberg and Joblin, 2003; Paillard et al., 2007). Goats fed diet with CO supplementation had greater relative abundance of family Lachnospiraceae and a tendency for increased genus Butyrivibrio_2, which may have been responsible for utilizing H2 for C18 biohydrogenation in our study. Decreased ruminal H2 may facilitate H2 production and inhibit H2 utilization (Janssen, 2010; Wang et al., 2016). The family Rikenellaceae is described as rod-shaped bacteria and can ferment carbohydrates to produce H2 (Su et al., 2014). CO supplementation increased relative abundance of family Rikenellaceae. The family Bacteroidales_BS11_gut_group belongs to order Bacteroidales and is an H2 user (Gast et al., 2009), while R. amylophilus is a starch-using bacteria and is also an H2-user (Anderson, 1995). CO supplementation decreased relative abundance of family Bacteroidales_BS11_gut_group and16S rRNA gene copies of R. amylophilus. A shift in the bacterial community composition indicated that CO supplementation favored growth of family Lachnospiraceae and genus Butyrivibrio_2 that use H2 for UFA biohydrogenation. However, there was also a decline in the relative abundance of some other H2-using bacterial groups as well as an increase in the relative abundance of some H2-producing bacterial groups.

The C18 fatty acids of oil are toxic to protozoa (Machmüller et al., 2000). Fatty acids are considered to inhibit methanogens by binding to the cell membrane and interrupting membrane transport (Dohme et al., 2001). Oil supplementation has been shown to decrease the methanogen population (Mao et al., 2010), which was not the case in our study. This lack of effect on methanogen population is consistent with the unchanged protozoa population, as 10% to –20% of methanogens are associated with protozoa (Stumm et al., 1982). However, CO supplementation may also alter some groups of methanogens, as shifts of methanogen community were observed within each individual goat. CO supplementation decreased relative abundance and 16S rRNA gene copies of order Methanomicrobiales, and increased relative abundance and 16S rRNA gene copies of order Methanobacteriales and genus Methanobrevibacter. The reduction in dH2 concentration due to CO supplementation decreased H2 availability for methanogens, which may have changed the relative abundances of Methanobrevibacter and Methanomicrobium, as methanogens could have different advantages for using available rumen H2 (Danielsson et al., 2017). Methanogens hold genes encoding the key methanogenic enzyme methyl-coenzyme M reductase (MCR). MCRI and MCRII are two isoenzymes of MCR. MCRI is usually expressed at low H2 concentrations, while the MCRII is usually expressed at high H2 concentrations (Reeve et al., 1997). Methanobrevibacter ruminantium M1 can only code for MCRI (Leahy et al., 2010). Genus Methanobrevibacter may also code for MCRI, and thus was increased at lower H2 concentrations for CO treatment.

Conclusions

CO supplementation decreased ruminal dH2 and dCH4 concentrations, CH4 emissions, and increased ruminal SFA proportion. The unsaturated fatty acids in CO provided an additional H2 sink for biohydrogenation that competed with methanogenesis for available rumen H2. Reductive acetogenesis may have been another cause of enhanced H2 consumption leading to increased acetate production. CO supplementation increased acetate molar percentage and favored growth of some H2-producing bacterial groups, and decreased propionate molar percentage and inhibited growth of some H2-using bacterial groups. CO supplementation did not alter methanogen population, indicating that decreased methanogensis can be caused by the decreased activity of methanogens under low rumen H2. Thus, CO supplementation decreased the available H2 for methanogens through enhanced biohydrogenation and reductive acetogenesis, leading to enhanced acetate production and decreased CH4 emissions. Further researches are still need to investigate its effect on animal productivity and CH4 emissions over a longer period. Figure S1. The multiple samples rarefaction curve of bacteria. SP1–12 are number of samples. Figure S2. The multiple samples rarefaction curve of methanogens. SP1–12 are number of samples.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31922080 and 31561143009), National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant Nos. 2016YFD0500504 and 2018YFD0501800), State Key Laboratory of Animal Nutrition (Grant No. 2004DA125184F1705), China Agriculture Research System (Grant No. CARS-37), Major Project of Hunan Province (Grant No. 2017NK1020), Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (Grant No. 2016327), and CAS President’s International Fellowship (Grant No. 2018VBA0031).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Literature Cited

- Anderson K. L. 1995. Biochemical analysis of starch degradation by Ruminobacter amylophilus 70. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:1488–1491. doi: 10.1002/bit.260460112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Animut G., Puchala R., Goetsch A. L., Patra A. K., Sahlu T., Varel V. H., and Wells J.. 2008. Methane emission by goats consuming different sources of condensed tannins. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 144:228–241. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2007.10.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. 2005. Official methods of analysis. 18th ed.Gaithersburg, MD:Association of Official Analytical Chemists. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin K. A., McGinn S. M., Benchaar C., and Holtshausen L.. 2009. Crushed sunflower, flax, or canola seeds in lactating dairy cow diets: effects on methane production, rumen fermentation, and milk production. J. Dairy Sci. 92:2118–2127. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benchaar C., Hassanat F., Martineau R., and Gervais R.. 2015. Linseed oil supplementation to dairy cows fed diets based on red clover silage or corn silage: effects on methane production, rumen fermentation, nutrient digestibility, N balance, and milk production. J. Dairy Sci. 98:7993–8008. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-9398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt R. S., Soren N. M., Tripathi M. K., and Karim S. A.. 2011. Effects of different levels of coconut oil supplementation on performance, digestibility, rumen fermentation and carcass traits of Malpura lambs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 164:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2010.11.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatta R., Enishi O., Yabumoto Y., Nonaka I., Takusari N., Higuchi K., Tajima K., Takenaka A., and Kurihara M.. 2012. Methane reduction and energy partitioning in goats fed two concentrations of tannin from Mimosa spp. J. Agric. Sci. 151:119–128. doi: 10.1017/s0021859612000299 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boadi D., Benchaar C., Chiquette J., and Massé D.. 2004. Mitigation strategies to reduce enteric methane emissions from dairy cows: update review. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 84:319–335. doi: 10.4141/A03-109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boeckaert C., Vlaeminck B., Fievez V., Maignien L., Dijkstra J., and Boon N.. 2008. Accumulation of trans C18:1 fatty acids in the rumen after dietary algal supplementation is associated with changes in the Butyrivibrio community. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:6923–6930. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01473-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolte M. R., Scholljegerdes E. J., Hess B. W., Gould J., Rule D. C., and Owens F. N.. 2001. Long-chain fatty acid flow in and digestion by beef steers fed dry-rolled or high-moisture typical or high-oil corn diets. J. Anim. Sci. 79(Suppl. 2):98 (Abstr.) [Google Scholar]

- Bray J. R., and Curtis J. T.. 1957. An ordination of the upland forest communities of southern Wisconsin. Ecol. Monogr. 27:325–349. doi: 10.2307/1942268 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso J. G., Bittinger K., Bushman F. D., DeSantis T. Z., Andersen G. L., and Knight R.. 2010. PyNAST: a flexible tool for aligning sequences to a template alignment. Bioinformatics 26:266–267. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsson R., Dicksved J., Sun L., Gonda H., Müller B., Schnürer A., and Bertilsson J.. 2017. Methane production in dairy cows correlates with rumen methanogenic and bacterial community structure. Front. Microbiol. 8:226. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohme F., Machmüller A., Wasserfallen A., and Kreuzer M.. 2001. Ruminal methanogenesis as influenced by individual fatty acids supplemented to complete ruminant diets. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 32:47–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.2001.00863.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckett S. K., Andrae J. G., and Owens F. N.. 2002. Effect of high-oil corn or added corn oil on ruminal biohydrogenation of fatty acids and conjugated linoleic acid formation in beef steers fed finishing diets. J. Anim. Sci. 80:3353–3360. doi: 10.2527/2002.80123353x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. 2013. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10:996–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C., Haas B. J., Clemente J. C., Quince C., and Knight R.. 2011. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27:2194–2200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagen E. J., Padmanabha J., Denman S. E., and McSweeney C. S.. 2015. Hydrogenotrophic culture enrichment reveals rumen Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae acetogens and hydrogen-responsive Bacteroidetes from pasture-fed cattle. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 362:fnv104. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnv104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gast R. J., Sanders R. W., and Caron D. A.. 2009. Ecological strategies of protists and their symbiotic relationships with prokaryotic microbes. Trends Microbiol. 17:563–569. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber P. J., Steinfeld H., Henderson B., Mottet A., Opio C., Dijkman J., Falcucci A., and Tempio G.. 2013. Tackling climate change through livestock: a global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Gonthier C., Mustafa A. F., Berthiaume R., Petit H. V., Martineau R., and Ouellet D. R.. 2004. Effects of feeding micronized and extruded flaxseed on ruminal fermentation and nutrient utilization by dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 87:1854–1863. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(04)73343-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty R., and Gerdes R.. 1998. Hydrogen production and transfer in the rumen. Rec. Adv. Anim. Nutr. 12:37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen P. H. 2010. Influence of hydrogen on rumen methane formation and fermentation balances through microbial growth kinetics and fermentation thermodynamics. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 160:1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2010.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins T. C., Wallace R. J., Moate P. J., and Mosley E. E.. 2008. Board-invited review: recent advances in biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids within the rumen microbial ecosystem. J. Anim. Sci. 86:397–412. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao J., Wang P., He Z., Tang S., Zhou C., Han X., Wang M., Wu D., Kang J., and Tan Z.. 2014. In vitro evaluation on neutral detergent fiber and cellulose digestion by post-ruminal microorganisms in goats. J. Sci. Food Agric. 94:1745–1752. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.6485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. A., and Johnson D. E.. 1995. Methane emissions from cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 73:2483–2492. doi: 10.2527/1995.7382483x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kartchner R. J., and Theurer B.. 1981. Comparison of hydrolysis methods used in feed, digesta, and fecal starch analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 29:8–11. doi: 10.1021/jf00103a003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozich J. J., Westcott S. L., Baxter N. T., Highlander S. K., and Schloss P. D.. 2013. Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79:5112–5120. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01043-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leahy S. C., Kelly W. J., Altermann E., Ronimus R. S., Yeoman C. J., Pacheco D. M., Li D., Kong Z., McTavish S., Sang C., . et al. 2010. The genome sequence of the rumen methanogen Methanobrevibacter ruminantium reveals new possibilities for controlling ruminant methane emissions. PLoS One 5:e8926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loor J. J., Ueda K., Ferlay A., Chilliard Y., and Doreau M.. 2004. Biohydrogenation, duodenal flow, and intestinal digestibility of trans fatty acids and conjugated linoleic acids in response to dietary forage:concentrate ratio and linseed oil in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 87:2472–2485. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(04)73372-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z., Wang R., Wang M., Zhang X., Mao H., and Tan Z.. 2018. Short communication: variability in fermentation end-products and methanogen communities in different rumen sites of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 101:5153–5158. doi: 10.3168/jds.2017-14096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machmüller A., Ossowski D. A., and Kreuzer M.. 2000. Comparative evaluation of the effects of coconut oil, oilseeds and crystalline fat on methane release, digestion and energy balance in lambs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 85:41–60. doi: 10.1016/S0377-8401(00)00126-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Machmüller A., Soliva C. R., and Kreuzer M.. 2003. Effect of coconut oil and defaunation treatment on methanogenesis in sheep. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 43:41–55. doi:10.1051/rnd:2003005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia M. R., Chaudhary L. C., Figueres L., and Wallace R. J.. 2007. Metabolism of polyunsaturated fatty acids and their toxicity to the microflora of the rumen. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 91:303–314. doi: 10.1007/s10482-006-9118-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao H. L., Wang J. K., Zhou Y. Y., and Liu J. X.. 2010. Effects of addition of tea saponins and soybean oil on methane production, fermentation and microbial population in the rumen of growing lambs. Livest. Sci. 129:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2009.12.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Fernandez G., Denman S. E., Cheung J., and McSweeney C. S.. 2017. Phloroglucinol degradation in the rumen promotes the capture of excess hydrogen generated from methanogenesis inhibition. Front. Microbiol. 8:1871. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinn S. M., Beauchemin K. A., Coates T., and Colombatto D.. 2004. Methane emissions from beef cattle: effects of monensin, sunflower oil, enzymes, yeast, and fumaric acid. J. Anim. Sci. 82:3346–3356. doi: 10.2527/2004.82113346x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Fallon J. V., Busboom J. R., Nelson M. L., and Gaskins C. T.. 2007. A direct method for fatty acid methyl ester synthesis: application to wet meat tissues, oils, and feedstuffs. J. Anim. Sci. 85:1511–1521. doi: 10.2527/jas.2006-491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen J., Blanchet F. G., Kindt R., Legendre P., Minchin P. R., O’hara R. B., and Stevens M. H. H.. 2017. Vegan: community ecology package. R package Version 2:4–4. [Google Scholar]

- Paillard D., McKain N., Rincon M. T., Shingfield K. J., Givens D. I., and Wallace R. J.. 2007. Quantification of ruminal Clostridium proteoclasticum by real-time PCR using a molecular beacon approach. J. Appl. Microbiol. 103:1251–1261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03349.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra A. K. 2012. Enteric methane mitigation technologies for ruminant livestock: a synthesis of current research and future directions. Environ. Monit. Assess. 184:1929–1952. doi: 10.1007/s10661-011-2090-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra A. K., and Yu Z.. 2013. Effects of coconut and fish oils on ruminal methanogenesis, fermentation, and abundance and diversity of microbial populations in vitro. J. Dairy Sci. 96:1782–1792. doi: 10.3168/jds.2012-6159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchala R., LeShure S., Gipson T. A., Tesfai K., Flythe M. D., and Goetsch A. L.. 2018. Effects of different levels of lespedeza and supplementation with monensin, coconut oil, or soybean oil on ruminal methane emission by mature Boer goat wethers after different lengths of feeding. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 46:1127–1136. doi: 10.1080/09712119.2018.1473253 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quast C., Pruesse E., Yilmaz P., Gerken J., Schweer T., Yarza P., Peplies J., and Glockner F. O.. 2013. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41:D590–D596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao C. R. 1971. Estimation of variance and covariance components-MINQUE theory. J. Multiva. Ana. 1:257–275. doi:1016/0047-259X(71)90001-7 [Google Scholar]

- Reeve J. N., Nölling J., Morgan R. M., and Smith D. R.. 1997. Methanogenesis: genes, genomes, and who’s on first? J. Bacteriol. 179:5975–5986. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.19.5975-5986.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schloss P. D., Westcott S. L., Ryabin T., Hall J. R., Hartmann M., Hollister E. B., Lesniewski R. A., Oakley B. B., Parks D. H., Robinson C. J., . et al. 2009. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:7537–7541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahinian A. H., and Reinhold J. G.. 1971. Application of the phenol-hypochlorite reaction to measurement of ammonia concentrations in Kjeldahl digests of serum and various tissues. Clin. Chem. 17:1077–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2010.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumm C. K., Gijzen H. J., and Vogels G. D.. 1982. Association of methanogenic bacteria with ovine rumen ciliates. Br. J. Nutr. 47:95–99. doi: 10.1079/bjn19820013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X. L., Tian Q., Zhang J., Yuan X. Z., Shi X. S., Guo R. B., and Qiu Y. L.. 2014. Acetobacteroides hydrogenigenes gen. nov., sp. nov., an anaerobic hydrogen-producing bacterium in the family Rikenellaceae isolated from a reed swamp. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 64(Pt 9):2986–2991. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.063917-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungerfeld E. M. 2015. Shifts in metabolic hydrogen sinks in the methanogenesis-inhibited ruminal fermentation: a meta-analysis. Front. Microbiol. 6:37. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Vossenberg J. L. C. M. and Joblin K. N.. 2003. Biohydrogenation of C18 unsaturated fatty acids to stearic acid by a strain of Butyrivibrio hungatei from the bovine rumen. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 37:424–428. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765X.2003.01421.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest P. J., Robertson J. B., and Lewis B. A.. 1991. Symposium: carbohydrate methodology, metabolism and nutritional implications in dairy cattle. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 74:3583–3597. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(91)78551-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Garrity G. M., Tiedje J. M., and Cole J. R.. 2007. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. and McAllister T. A.. 2002. Rumen microbes, enzymes and feed digestion-a review. Asian-Aust. J. Anim. Sci. 15:1659–1676. doi: 10.5713/ajas.2002.1659 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Janssen P. H., Sun X. Z., Muetzel S., Tavendale M., Tan Z. L., and Pacheco D.. 2013. A mathematical model to describe in vitro kinetics of H2 gas accumulation. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 184:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2013.05.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Sun X. Z., Janssen P. H., Tang S. X., and Tan Z. L.. 2014. Responses of methane production and fermentation pathways to the increased dissolved hydrogen concentration generated by eight substrates in in vitro ruminal cultures. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 194: 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2014.04.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Wang R., Janssen P. H., Zhang X. M., Sun X. Z., Pacheco D., and Tan Z. L.. 2016. Sampling procedure for the measurement of dissolved hydrogen and volatile fatty acids in the rumen of dairy cows. J. Anim. Sci. 94:1159–1169. doi: 10.2527/jas.2015-9658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Wang R., Zhang X., Ungerfeld E. M., Long D., Mao H., Jiao J., Beauchemin K. A., and Tan Z.. 2017. Molecular hydrogen generated by elemental magnesium supplementation alters rumen fermentation and microbiota in goats. Br. J. Nutr. 118:401–410. doi: 10.1017/S0007114517002161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward S. L., Waghorn G. C., and Thomson N. A.. 2006. Supplementing dairy cows with oils to improve performance and reduce methane—Does it work? Proc. N.Z. Soc. Anim. Prod. 66:176–181. [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. 2012. GenMod: an R package for various agricultural data analyses. ASA, CSSA, and SSSA 2012 International Annual Meetings, Cincinnati, OH; p. 127. [Google Scholar]

- Yang S. L., Bu D. P., Wang J. Q., Hu Z. Y., Li D., Wei H. Y., Zhou L. Y., and Loor J. J.. 2009. Soybean oil and linseed oil supplementation affect profiles of ruminal microorganisms in dairy cows. Animal 3:1562–1569. doi: 10.1017/S1751731109990462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z., and Morrison M.. 2004. Improved extraction of PCR-quality community DNA from digesta and fecal samples. Biotechniques 36:808–812. doi: 10.2144/04365ST04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. F. and Zhang Z. Y.. 1998. Animal nutrition parameters and feeding standard. Beijing: China Agriculture Press. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.