Abstract

Background

Prior stroke is regarded as risk factor for bleeding after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). However, there is a paucity of data on detailed bleeding risk of patients with prior hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes after PCI.

Methods and Results

In a pooled cohort of 19 475 patients from 3 Japanese PCI studies, we assessed the influence of prior hemorrhagic (n=285) or ischemic stroke (n=1773) relative to no‐prior stroke (n=17 417) on ischemic and bleeding outcomes after PCI. Cumulative 3‐year incidences of the co‐primary bleeding end points of intracranial hemorrhage, non‐intracranial global utilization of streptokinase and tissue plasminogen activator for occluded coronary arteries (GUSTO) moderate/severe bleeding, and the primary ischemic end point of ischemic stroke/myocardial infarction were higher in the prior hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke groups than in the no‐prior stroke group (6.8%, 2.5%, and 1.3%, P<0.0001, 8.8%, 8.0%, and 6.0%, P=0.001, and 12.7%, 13.4%, and 7.5%, P<0.0001). After adjusting confounders, the excess risks of both prior hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes relative to no‐prior stroke remained significant for intracranial hemorrhage (hazard ratio (HR) 4.44, 95% CI 2.64–7.01, P<0.0001, and HR 1.52, 95% CI 1.06–2.12, P=0.02), but not for non‐intracranial bleeding (HR 1.18, 95% CI 0.76–1.73, P=0.44, and HR 0.94, 95% CI 0.78–1.13, P=0.53). The excess risks of both prior hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes relative to no‐prior stroke remained significant for ischemic events mainly driven by the higher risk for ischemic stroke (HR 1.46, 95% CI 1.02–2.01, P=0.04, and HR 1.49, 95% CI 1.29–1.72, P<0.0001).

Conclusions

Patients with prior hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke as compared with those with no‐prior stroke had higher risk for intracranial hemorrhage and ischemic events, but not for non‐intracranial bleeding after PCI.

Keywords: coronary artery disease, percutaneous coronary intervention, stroke

Subject Categories: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Ischemic Stroke, Intracranial Hemorrhage

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

There is a paucity of data evaluating the bleeding risk of patients with prior hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke separately.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Our study findings suggest that prior hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke are associated with higher risk for intracranial hemorrhage and ischemic events, but not for non‐intracranial bleeding after percutaneous coronary intervention.

Introduction

Patients with prior stroke constitute 8% to 12% of the population undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).1, 2 Patients with prior stroke are generally regarded as having high bleeding risk, in whom consideration might be needed to shorted the duration of a dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) after PCI. In patients with acute (<12–24 hours) ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), 3 previous studies, CHANCE (the Clopidogrel in High‐Risk Patients with Acute Nondisabling Cerebrovascular Events), SOCRATES (the Acute Stroke or Transient Ischaemic Attack Treated with Aspirin or Ticagrelor and Patient Outcomes), and POINT (the Platelet‐Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke) suggested that short‐term (≈90 days) DAPT or ticagrelor monotherapy as compared with aspirin monotherapy significantly reduced ischemic stroke without increase in hemorrhagic stroke.3, 4, 5 However, in patients with recent (≈90–180 days) ischemic stroke or TIA, 3 other previous studies, MATCH (the Management of Atherothrombosis with Clopidogrel in High‐Risk Patients), PRoFESS (the Prevention Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes), and SPS3 (the Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes) demonstrated that long‐term (1.5–3 years) DAPT as compared with clopidogrel or aspirin monotherapy increased major bleeding and intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) without reduction in ischemic stroke.6, 7, 8 Therefore, in the 2018 American Stroke Association/American Heart Association guidelines, DAPT initiated within 24 hours is recommended for early secondary prevention during the initial 90 days, but is not recommended for routine long‐term secondary prevention after a minor stroke or TIA.9 DAPT is also not recommended for routine long‐term secondary prevention after major stroke.10

Trials of potent DAPT after acute coronary syndrome have excluded patients with prior hemorrhagic stroke, but not prior ischemic stroke/TIA. The risk for ICH was higher in patients with prior stroke than those without when treated with more potent P2Y12 inhibitors such as prasugrel, ticagrelor, or vorapaxar, while it was discordant when treated with clopidogrel.11, 12, 13 The current PCI guidelines do not provide recommendations on DAPT duration specific for patients with prior ischemic stroke.14, 15 Furthermore, there is a paucity of data about DAPT in patients with prior hemorrhagic stroke. Therefore, we sought to evaluate the impact of prior stroke, stratified by hemorrhagic or ischemic subtypes, on ischemic and bleeding events after PCI in a large Japanese database.

Methods

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article and its online supplementary files.

Study Population

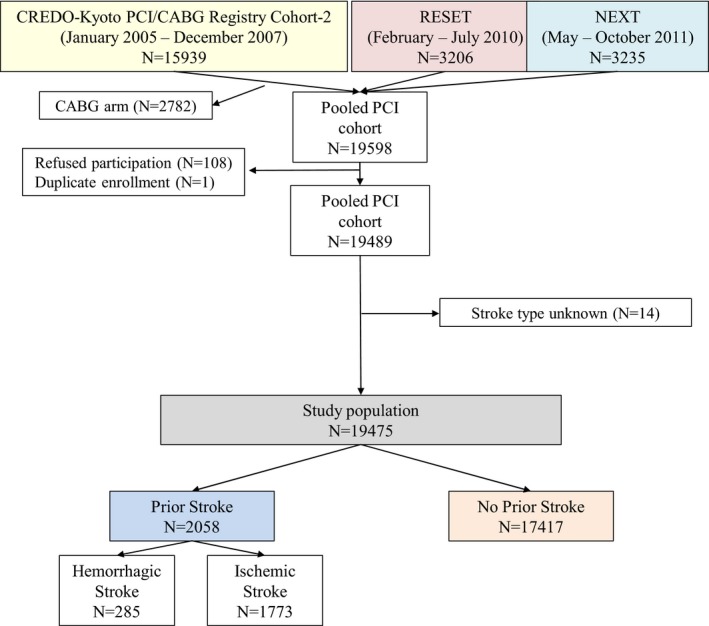

We performed a patient‐level pooled analysis of the 3 PCI studies conducted after the introduction of a drug‐eluting stent in Japan including CREDO‐Kyoto (The Coronary Revascularization Demonstrating Outcome study in Kyoto) PCI/coronary artery bypass grafting registry cohort‐2, RESET (the Randomized Evaluation of Sirolimus‐Eluting Versus Everolimus‐Eluting Stent Trial), and NEXT (NOBORI Biolimus‐Eluting Versus XIENCE/PROMUS Everolimus‐Eluting Stent Trial) (Figure 1).16, 17, 18 The CREDO‐Kyoto PCI/coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) registry cohort‐2 is an investigator‐initiated multicenter registry enrolling consecutive patients who underwent first coronary revascularization procedures among 26 centers in Japan between January 2005 and December 2007.16 RESET and NEXT are prospective, multicenter, randomized trials in Japan comparing everolimus‐eluting stent with sirolimus‐eluting stent and comparing biolimus‐eluting stent with everolimus‐eluting stent, respectively.17, 18 The relevant review boards in all the participating centers for each study approved each research protocol for the 3 studies. Because of retrospective enrollment, written informed consents from the patients were waived in the CREDO‐Kyoto PCI/CABG registry cohort‐2; however, we excluded those patients who refused participation in the study when contacted for follow‐up. Written informed consents were obtained from all the study patients in the RESET and NEXT trials. Patients with recent strokes and/or ICH were not excluded from the CREDO‐Kyoto registry cohort‐2, RESET, and NEXT.

Figure 1.

Study patient flow. CABG indicates coronary artery bypass grafting; CREDO‐Kyoto, the Coronary Revascularization Demonstrating Outcome study in Kyoto; NEXT, NOBORI Biolimus‐Eluting Versus XIENCE/PROMUS Everolimus‐Eluting Stent TrialPCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RESET, the Randomized Evaluation of Sirolimus‐Eluting Versus Everolimus‐Eluting Stent Trial.

Among the total 19 489 PCI patients in these 3 studies, the current study population consisted of 19 475 patients after excluding 14 patients in whom the type of stroke was unknown (Figure 1). Among them, 2058 patients had prior stroke (10.6%) including 285 patients with prior hemorrhagic stroke (hemorrhagic stroke group: 1.5%), and 1773 patients with prior ischemic stroke (ischemic stroke group: 9.1%), whereas 17 417 patients (89.4%) had no prior stroke (no‐prior stroke group). Cerebral hemorrhage subsequent to ischemic stroke was not regarded as hemorrhagic stroke, but was regarded as ischemic stroke. Patients who had histories of both hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke were allocated to the hemorrhagic stroke group. Among 285 patients with prior hemorrhagic stroke, 61 patients (21%) also had prior ischemic stroke. Prior TIA was not regarded as prior stroke.

Procedural anticoagulation was achieved with unfractionated heparin based on the local site protocols. The recommended antiplatelet regimen included aspirin (≥81 mg/day) indefinitely and thienopyridines (75 mg of clopidogrel or 200 mg of ticlopidine daily) for ≥3 months across 3 studies regardless of the stent types. The actual DAPT duration was left to the discretion of each attending physician. The status of antiplatelet therapy was evaluated throughout the follow‐up period by the same methodology across all the studies. Discontinuation of DAPT was defined as the persistent discontinuation of either aspirin or thienopyridine for 2 months or longer.19

Definitions

Definitions of the baseline characteristics were consistent across the 3 studies. The primary ischemic end point was defined as a composite of ischemic stroke or myocardial infarction (MI), while the co‐primary bleeding end points were ICH and non‐intracranial major bleeding defined as the global utilization of streptokinase and tissue plasminogen activator for occluded coronary arteries (GUSTO) moderate/severe bleeding.20 Stroke during follow‐up was defined as that requiring hospitalization with symptoms lasting >24 hours. Cerebral hemorrhage subsequent to ischemic stroke was not regarded as hemorrhagic stroke, but regarded as ischemic stroke, while it was included in the bleeding event. Traumatic brain bleeding was not regarded as hemorrhagic stroke, but included in intracranial bleeding. MI was adjudicated by the definition of ARTS (Arterial Revascularization Therapies Study) in CREDO Kyoto PCI/CABG registry cohort‐2, and by the definition of Academic Research Consortium consensus criteria in the RESET and NEXT.21, 22 However, both the ARTS and the Academic Research Consortium definitions adopted the same criteria for spontaneous MI (biomarker elevation above upper limit of normal). The definitions for the outcomes other than MI were identical across the 3 studies. Stent thrombosis was defined according to the definition of the Academic Research Consortium.22 Target‐lesion revascularization was defined as either PCI or CABG attributable to restenosis or thrombosis of the target lesion that included the proximal and distal edge segments as well as the ostium of the side branches. All clinical events were adjudicated by the independent clinical event committees in each study.

Data Collection and Follow‐Up

In all 3 studies, demographic, angiographic, and procedural data were collected from hospital charts or databases in each participating center according to the pre‐specified definitions by the site investigators or by the experienced clinical research coordinators in the study management center (Research Institute for Production Development, Kyoto, Japan). Follow‐up data were obtained from hospital charts or by contacting patients or referring physicians with questions on vital status, subsequent hospitalization, and status of antiplatelet therapy. The follow‐up duration was 5 years in the CREDO‐Kyoto PCI/CABG registry cohort‐2, and 3 years in the RESET and NEXT. In the present analysis, follow‐up was truncated at 3 years to standardize the follow‐up duration.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were presented as number and percentage and were compared with the Chi‐square test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean value±SD, and were compared with analysis of variance or Kruskal–Wallis based on the distributions. Cumulative incidence was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and differences were assessed with the log‐rank test.

We used Cox proportional hazard models to estimate the risk of the prior hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke groups, respectively, relative to no‐prior stroke group for clinical end points adjusting the clinically relevant factors for the patient characteristics and medications. We chose 17 clinically relevant factors for both bleeding and ischemic events shown in Table 1 as the risk adjusting variables in consistent with our previous studies.23 The continuous variables were dichotomized by clinically meaningful reference values. Prior hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke and the 17 risk‐adjusting variables were simultaneously included in the Cox proportional hazard model for the adjusted analyses. In the Cox proportional hazard model, we developed dummy code variables for prior hemorrhagic stroke and prior ischemic stroke with no‐prior stroke as the reference. We also developed dummy codes for the RESET and the NEXT trials with the CREDO‐Kyoto Registry cohort‐2 as the reference to adjust for the differences in studies. The effects of the prior hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke groups as compared with no‐prior stroke reference group were expressed as hazard ratio (HR) and their 95% CI. We constructed the same Cox proportional hazard model to estimate the HRs for prior hemorrhagic stroke and prior ischemic stroke compared with no‐prior stroke in the subgroup of acute myocardial infarction. We calculated the type 3 P values for interaction between prior stroke status and subgroup factor. Statistical analyses were conducted by a physician (Natsuaki M) and a statistician (Morimoto T) with the use of JMP 10.0 software. All the statistical analyses were 2‐tailed. P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics and Medications

| Hemorrhagic Stroke | Ischemic Stroke | No Prior Stroke | P Value | SMD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=285) | (n=1773) | (n=17 417) | |||

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Age, y | 71.0±9.2 | 72.3±9.0 | 68.1±10.8 | <0.0001 | 0.39 |

| Age ≥75 ya | 109 (38%) | 771 (43%) | 5231 (30%) | <0.0001 | 0.29 |

| Mena | 212 (74%) | 1332 (75%) | 12 781 (73%) | 0.27 | 0.04 |

| BMI | 23.2±3.3 | 23.5±3.5 | 23.9±3.5 | <0.0001 | 0.2 |

| BMI <25.0a | 205/275 (75%) | 1151/1685 (68%) | 11 088/16 989 (65%) | 0.0002 | 0.2 |

| Acute myocardial infarctiona | 77 (27%) | 394 (22%) | 4590 (26%) | 0.0006 | 0.09 |

| Hypertensiona | 261 (92%) | 1545 (87%) | 14 082 (81%) | <0.0001 | 0.29 |

| Diabetes mellitusa | 117 (41%) | 853 (48%) | 6847 (39%) | <0.0001 | 0.18 |

| On insulin therapy | 25 (8.8%) | 208 (12%) | 1435 (8.2%) | <0.0001 | 0.12 |

| Current smokinga | 65 (23%) | 322 (18%) | 5012 (29%) | <0.0001 | 0.24 |

| Heart failurea | 57 (20%) | 450 (25%) | 2903 (17%) | <0.0001 | 0.23 |

| Multivessel disease | 165 (58%) | 1773 (61%) | 9037 (51%) | <0.0001 | 0.18 |

| Mitral regurgitation grade 3/4 | 9 (3.2%) | 79 (4.5%) | 538 (3.1%) | 0.01 | 0.08 |

| LVEF, % | 57.8±13.3 (237) | 57.5±13.3 (1447) | 59.1±12.7 (14 635) | <0.0001 | 0.13 |

| Prior myocardial infarctiona | 53 (19%) | 322 (18%) | 2870 (16%) | 0.14 | 0.06 |

| Peripheral vascular diseasea | 26 (9.1%) | 259 (15%) | 1092 (6.3%) | <0.0001 | 0.32 |

| Moderate CKDa | 107 (38%) | 718 (41%) | 5214 (30%) | <0.0001 | 0.23 |

| Severe CKDa | 33 (12%) | 232 (13%) | 1241 (7.1%) | <0.0001 | 0.22 |

| eGFR <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2, not on dialysis | 16 (5.6%) | 122 (6.9%) | 544 (3.1%) | <0.0001 | 0.2 |

| Dialysis | 17 (6.0%) | 110 (6.2%) | 697 (4.0%) | <0.0001 | 0.11 |

| Atrial fibrillationa | 36 (13%) | 253 (14%) | 1267 (7.3%) | <0.0001 | 0.26 |

| Anemia (hemoglobin <11 g/dL)a | 47 (16%) | 334 (19%) | 1929 (11%) | <0.0001 | 0.24 |

| Platelet <100×109/La | 7 (2.5%) | 31 (1.8%) | 255 (1.5%) | 0.31 | 0.08 |

| COPD | 9 (3.2%) | 74 (4.2%) | 535 (3.1%) | 0.054 | 0.06 |

| Liver cirrhosisa | 6 (2.1%) | 41 (2.3%) | 335 (1.9%) | 0.54 | 0.03 |

| Malignancya | 24 (8.4%) | 183 (10%) | 1429 (8.2%) | 0.01 | 0.08 |

| Procedural characteristics | |||||

| Number of target lesions | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 0.003 | 0.07 |

| 1.42±0.71 | 1.43±0.71 | 1.38±0.69 | |||

| Target of proximal LAD | 159 (56%) | 907 (51%) | 9363 (54%) | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| Target of unprotected LMCA | 9 (3.2%) | 77 (4.3%) | 559 (3.2%) | 0.051 | 0.07 |

| Target of CTO | 32 (11%) | 198 (11%) | 1767 (10%) | 0.35 | 0.04 |

| Target of bifurcation | 77 (27%) | 499 (28%) | 5125 (29%) | 0.37 | 0.05 |

| Side‐branch stenting | 8 (2.8%) | 66 (3.7%) | 627 (3.6%) | 0.73 | 0.05 |

| Total number of stents | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | <0.0001 | 0.12 |

| 1.85±1.22 (275) | 1.87±1.21 (1688) | 1.74±1.11 (16 614) | |||

| Total stent length, mm | 28 (18–50) | 30 (18–51) | 28 (18–46) | <0.0001 | 0.12 |

| 39.2±29.0 (275) | 40.1±29.3 (1687) | 36.7±26.4 (16 603) | |||

| Minimum stent size, mm | 3.0 (2.5–3.0) | 2.75 (2.5–3.0) | 3.0 (2.5–3.0) | <0.0001 | 0.16 |

| 2.88±0.42 (275) | 2.85±0.41 (1687) | 2.92±0.43 (16 602) | |||

| Baseline medication | |||||

| Medication at hospital discharge | |||||

| Antiplatelet therapy | |||||

| Thienopyridine | 279 (97.9%) | 1730 (97.6%) | 17 052 (97.9%) | 0.67 | 0.02 |

| Ticlopidine | 200 (70%) | 1120 (63%) | 10 979 (63%) | 0.04 | 0.15 |

| Clopidogrel | 79 (28%) | 606 (34%) | 6011 (35%) | 0.051 | 0.15 |

| Aspirin | 281 (98.6%) | 1737 (98.0%) | 17 241 (99.0%) | 0.002 | 0.1 |

| Cilostazole | 49 (17%) | 273 (15%) | 2579 (15%) | 0.45 | 0.07 |

| Other medications | |||||

| Statins | 133 (47%) | 943 (53%) | 10 539 (61%) | <0.0001 | 0.28 |

| Beta‐blockers | 101 (35%) | 555 (31%) | 5723 (33%) | 0.26 | 0.09 |

| ACE‐I/ARB | 194 (68%) | 1094 (62%) | 10 268 (59%) | 0.0007 | 0.19 |

| Nitrates | 92 (32%) | 595 (34%) | 5659 (32%) | 0.66 | 0.03 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 145 (51%) | 857 (48%) | 7105 (41%) | <0.0001 | 0.2 |

| Warfarin | 23 (8.1%) | 227 (13%) | 1324 (7.6%) | <0.0001 | 0.19 |

Values are expressed as mean±SD, median (interquartile range), or number (%). ACE‐I indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers; BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CTO, chronic total occlusion; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LMCA, left main coronary artery; SMD, standardized mean differences.

Potential independent variables selected in multivariable analysis.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics were much different in several aspects across the 3 groups (Table 1). Patients in the hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke groups were significantly older than those in the no‐prior stroke group. Body mass index in the hemorrhagic stroke group was significantly lower than that in the no‐prior stroke group. Patients in the hemorrhagic stroke group more often had hypertension, multivessel disease, chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, and anemia than patients in the no‐prior stroke group. Patients in the ischemic stroke group more often had hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart failure, multivessel disease, peripheral vascular disease, chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, and anemia than patients in the no‐prior stroke group. Patients in both the hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke groups less often had current smoking than patients in the no‐prior stroke group (Table 1). On the procedural characteristics, total stent length was significantly longer in the hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke groups than those in the no‐prior stroke group. For the baseline medications, DAPT was implemented in the vast majority of patients in the 3 groups. Patients in the hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke groups less often received statins, while they more often received inhibitors of the renin‐aldosterone system and calcium channel blockers. Patients in the ischemic stroke group more often received warfarin than patients in the no‐prior stroke group (Table 1).

Clinical Outcomes Through 3 Years

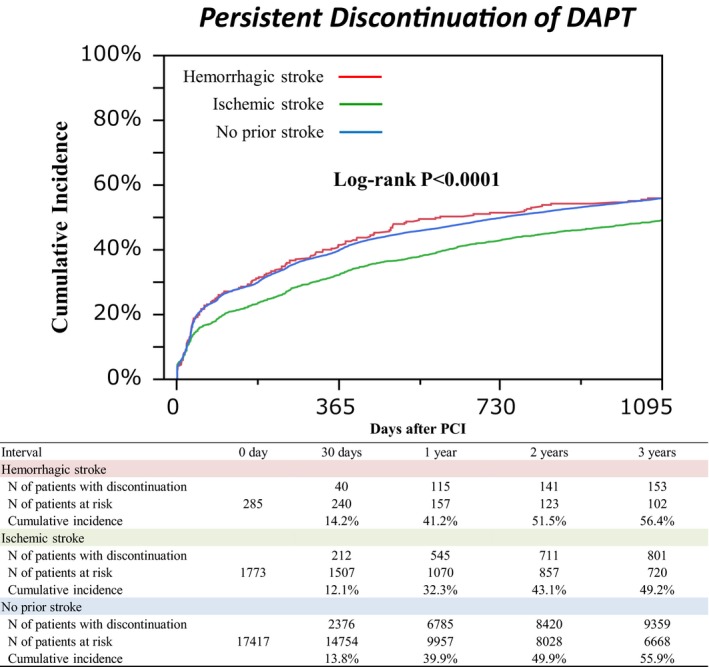

During 3‐year follow‐up, cumulative incidence of persistent discontinuation of DAPT was significantly lower in the ischemic stroke group than the other 2 groups, while it was not different between the hemorrhagic stroke group and the no‐prior stroke group. Substantial proportion of patients in the hemorrhagic stroke group had received prolonged DAPT (58.8% at 1 year and 43.6% at 3 years) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of persistent discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy. DAPT indicates dual antiplatelet therapy; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

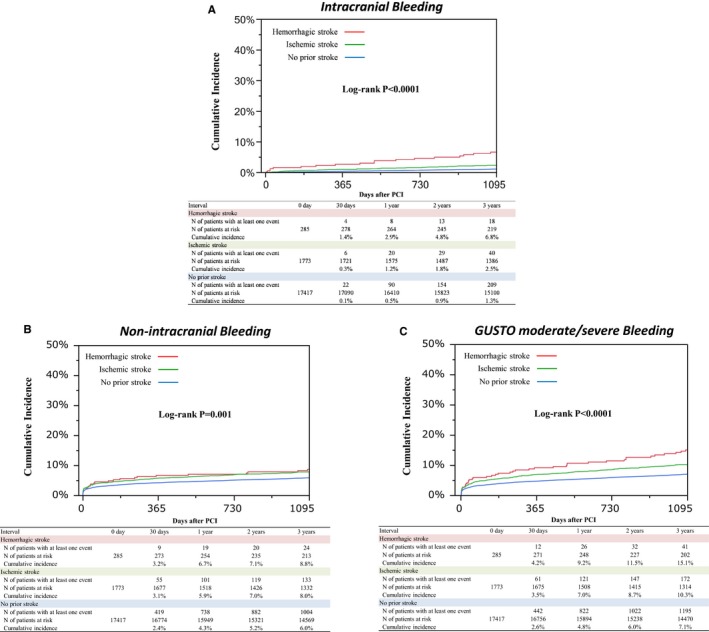

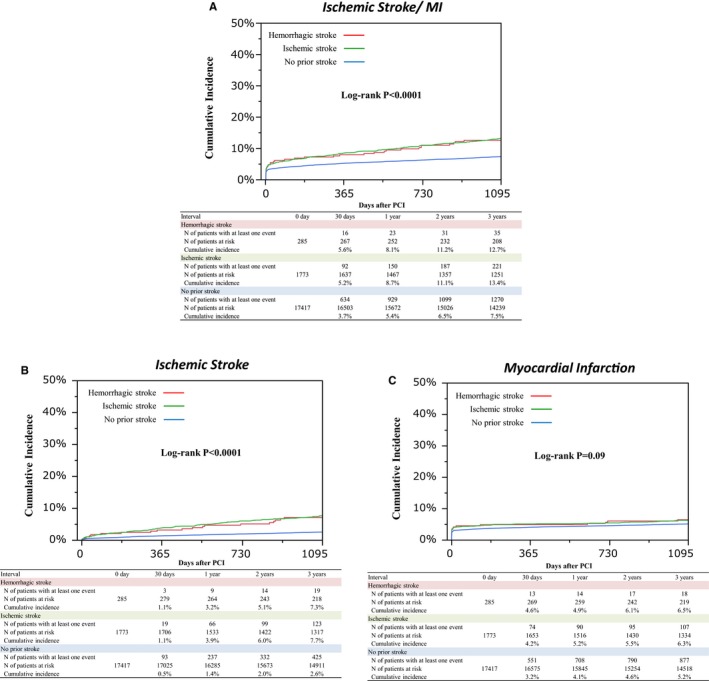

Cumulative incidence of ICH was much higher in the hemorrhagic stroke group than in the other 2 groups (6.8%, 2.5%, and 1.3%, P<0.0001) (Table 2 and Figure 3). Cumulative incidences of non‐intracranial bleeding, gastrointestinal bleeding, and any GUSTO moderate/severe bleeding were also higher in the hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke groups than patients in the no‐prior stroke group (8.8%, 8.0%, and 6.0%, P=0.001, and 3.7%, 3.0%, and 2.2%, P=0.04, and 15.1%, 10.3%, and 7.1%, P<0.0001) (Table 2 and Figure 3). Cumulative incidence of the primary ischemic end point of ischemic stroke/MI was significantly higher in the hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke groups than in the no‐prior stroke group (12.7%, 13.4%, and 7.5%, P<0.0001) (Table 2 and Figure 4A). Cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke was much higher in the hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke groups than in the no‐prior stroke group, while there was no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of MI across the 3 groups (7.1%, 7.7%, and 2.6%, P<0.0001, and 6.5%, 6.3%, and 5.2%, P=0.09) (Table 2 and Figure 4B, 4C). Cumulative incidence of all‐cause death was also higher in the hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke groups than in the no‐prior stroke group (14.7%, 17.1%, and 9.0%, P<0.0001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical Outcomes Through 3 Years

| Hemorrhagic Stroke | Ischemic Stroke | No Prior Stroke | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients With Events (Cumulative 3‐year Incidence) | No. of Patients With Events (Cumulative 3‐year Incidence) | No. of Patients with Events (Cumulative 3‐year Incidence) | ||

| (n=285) | (n=1773) | (n=17 417) | ||

| GUSTO moderate/severe bleeding | 41 (15.1%) | 172 (10.3%) | 1195 (7.1%) | <0.0001 |

| GUSTO severe bleeding | 22 (8.3%) | 81 (4.9%) | 526 (3.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 11 (4.2%) | 28 (1.7%) | 148 (0.9%) | <0.0001 |

| Intracranial bleeding | 18 (6.8%) | 40 (2.5%) | 209 (1.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Non‐intracranial bleeding | 24 (8.8%) | 133 (8.0%) | 1004 (6.0%) | 0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 10 (3.7%) | 49 (3.0%) | 368 (2.2%) | 0.04 |

| MI/Ischemic stroke | 35 (12.7%) | 221 (13.4%) | 1270 (7.5%) | <0.0001 |

| MI | 18 (6.5%) | 107 (6.3%) | 877 (5.2%) | 0.09 |

| Ischemic stroke | 19 (7.1%) | 123 (7.7%) | 425 (2.6%) | <0.0001 |

| Stroke | 30 (11.3%) | 147 (9.1%) | 570 (3.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Death | 41 (14.7%) | 298 (17.1%) | 1552 (9.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiac death | 13 (4.8%) | 160 (9.3%) | 778 (4.6%) | <0.0001 |

| Non‐cardiac death | 28 (10.5%) | 138 (8.5%) | 774 (4.7%) | <0.0001 |

| Death/MI/stroke | 75 (26.7%) | 475 (27.1%) | 2631 (15.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Definite/Probable ST | 4 (1.6%) | 17 (1.0%) | 216 (1.3%) | 0.63 |

| TLR | 44 (16.1%) | 229 (14.1%) | 2657 (15.9%) | 0.11 |

| Any coronary revascularization | 72 (26.5%) | 423 (26.2%) | 4650 (28.0%) | 0.15 |

GUSTO bleeding criteria: Severe=intracerebral hemorrhage or resulting in substantial hemodynamic compromise requiring treatment. Moderate=requiring blood transfusion but not resulting in hemodynamic compromise. GUSTO indicates global utilization of streptokinase and tissue plasminogen activator for occluded coronary arteries; MI, myocardial infarction; ST, stent thrombosis; TLR, target‐lesion revascularization.

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence of bleeding events through 3 years. A, Kaplan–Meier curves for intracranial bleeding through 3 years. B, Kaplan–Meier curves for non‐intracranial bleeding through 3 years. C, Kaplan–Meier curves for GUSTO moderate/severe bleeding through 3 years. GUSTO indicates global utilization of streptokinase and tissue plasminogen activator for occluded coronary arteries; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Figure 4.

Cumulative incidence of ischemic events through 3 years. A, Kaplan–Meier curves for the primary ischemic end point through 3 years. B, Kaplan–Meier curves for ischemic stroke through 3 years. C, Kaplan–Meier curves for myocardial infarction through 3 years. Primary ischemic end point was defined as a composite of ischemic stroke or MI. MI indicates myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

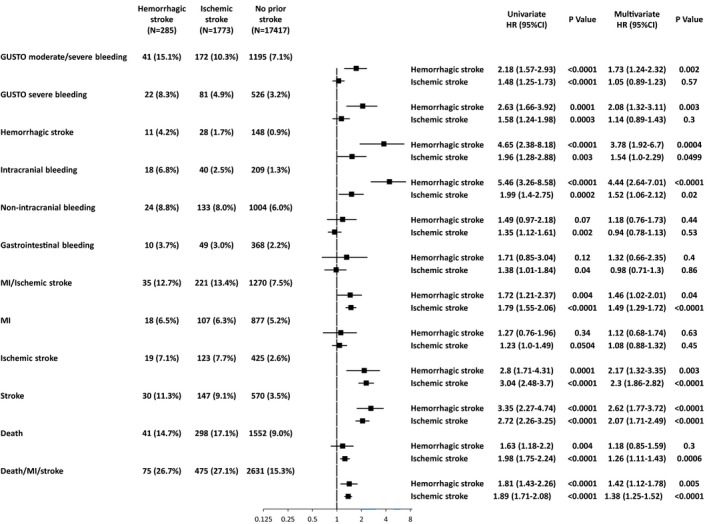

After adjusting the confounders, the excess risk of the hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke groups relative to the no‐prior stroke group remained significant for ICH, but not for non‐intracranial bleeding. Patients in the hemorrhagic stroke group, but not those in the ischemic stroke group, had higher risk for any GUSTO moderate/severe bleeding than patients in the no‐prior stroke group. Patients in the hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke groups had significantly higher adjusted risk for ischemic stroke/MI than patients in the no‐prior stroke group, which was mainly driven by the higher risk for ischemic stroke. Patients in the ischemic stroke group, but not those in the hemorrhagic stroke group, had higher mortality risk than patients in the no‐prior stroke group (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Forrest plot for the adjusted hazard ratios of prior hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke relative to no prior stroke for the clinical events. GUSTO indicates global utilization of streptokinase and tissue plasminogen activator for occluded coronary arteries; HR, hazard ratio; MI, myocardial infarction.

Clinical Outcomes Through 3 Years in Patients With or Without Acute Myocardial Infarction

Cumulative incidence of intracranial bleeding was significantly higher in the hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke groups than in the no‐prior stroke group in those with and without acute myocardial infarction (3.1%, 2.8%, and 1.1%, P=0.01 and 8.0%, 2.4%, and 1.3%, P<0.0001). Cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke/MI was also significantly higher in the hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke groups than in the no‐prior stroke group in those with and without acute myocardial infarction (13.0%, 15.3%, and 7.3%, P<0.0001 and 12.7%, 12.9%, and 7.6%, P<0.0001). There was no significant interaction between clinical presentation and prior stroke (Table S1).

Clinical Outcomes Through 3 Years in Patients With or Without Atrial Fibrillation in the Prior Ischemic Stroke Group

In the prior ischemic stroke group, cumulative incidence of GUSTO moderate/severe bleeding and ischemic stroke/MI was significantly higher in patients with atrial fibrillation than in those without (14.7% versus 9.6%, P=0.02, and 18.9% versus 12.5%, P=0.01). Cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke was markedly higher in patients with atrial fibrillation than in those without (14.1% versus 6.7%, P<0.0001) (Table S2).

Clinical Outcomes in Patients With or Without DAPT Between 4 Months and 3 Years By the Landmark Analysis at 4 Months

Cumulative incidences of non‐intracranial bleeding and ischemic stroke/MI between 4 months and 3 years tended to be higher in the prior hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke groups than in the no‐prior stroke group in patients with and without DAPT at 4 months (Table S3). However, cumulative incidence of ICH in the prior hemorrhagic stroke group was higher than in the no‐prior stroke group in patients on‐DAPT at 4 months, but not in patients off‐DAPT at 4 months.

Antiplatelet Therapy at the Onset of ICH and Ischemic Stroke

More than 70% of patients had DAPT at the time of ICH throughout the follow‐up period (0–30 days: 87.5%, 31–180 days: 76.7%, 181–365 days: 71.9%, 366–1095 days: 71.5%). On the other hand, patients with DAPT at the onset of ischemic stroke decreased with longer‐term follow‐up (0–30 days: 87.6%, 31–180 days: 66.3%, 181–365 days: 65.6%, 366–1095 days: 55.9%) (Figure S1).

Discussion

The main findings of this study were as follows: (1) Patients with prior hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke had higher adjusted risk for ICH, but not for non‐intracranial bleeding; (2) Patients in the hemorrhagic stroke group, but not those in the ischemic stroke group, had higher risk for any GUSTO moderate/severe bleeding than patients in the no‐prior stroke group; (3) Patients with prior hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke had significantly higher ischemic risk (ischemic stroke/MI), which was mainly driven by the higher risk for ischemic stroke.

The impact of prior stroke on bleeding after PCI might be different according to the type of bleeding. In predicting bleeding complications in patients undergoing stent implantation and subsequent dual antiplatelet therapy (PRECISE‐DAPT [the predicting bleeding complications in patients undergoing stent implantation and subsequent dual antiplatelet therapy]) the predicting bleeding complications in patients undergoing stent implantation and subsequent dual antiplatelet therapy study including 8 trials enrolled between 2007 and 2014, patients with prior stroke had similar risk of thrombolysis in myocardial infarction major/minor bleeding as compared with those without (HR 1.16, 95% CI 0.54–2.48, P=0.70).24 In the PARIS (patterns of non‐adherence to anti‐platelet regimens in stented patients) registry, rates of BARC (the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium) 3 or 5 bleeding in patients with and without previous stroke were also similar (4.1% versus 3.5%, respectively, P=0.66).25 Indeed, prior stroke is not included as a risk factors for major bleeding in several bleeding risk scores.23, 24, 25 On the other hand, patients with previous stroke had higher risk for hemorrhagic stroke after PCI in the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society database (HR 4.07, 95% CI 1.13–14.62, P=0.03).26 Therefore, prior stroke might be associated with higher risk for ICH after PCI. However, impact of prior hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke on bleeding was not evaluated separately in these studies.

In the PLATO (Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes) trial excluding those with previous bleeding events, the risk for major bleeding was not significantly different between patients with or without prior ischemic stroke (adjusted HR 1.18, 95% CI 0.98–1.43, P=0.09), although this trial might not have enough power for the risk evaluation of major bleeding. On the other hand, patients with prior ischemic stroke had significantly higher rate of ICH than those without (0.8% versus 0.2%, P=0.0005).12 In line with the results of the PLATO trial, patients with prior ischemic stroke in the present study were not associated with higher risk for GUSTO moderate/severe bleeding, while they had significantly higher risk for ICH and hemorrhagic stroke. Therefore, prior ischemic stroke could be the risk for ICH after PCI, but not for non‐intracranial bleeding.

The data in patients with prior hemorrhagic stroke are scarce because most previous studies did not differentiate between ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.23, 24, 25 Furthermore, patients with prior hemorrhagic stroke had been excluded from the randomized trials considering the risk for the recurrence of bleeding events.27, 28 In the present study, patients with prior hemorrhagic stroke were associated with markedly higher risk for ICH than those with no prior stroke. Therefore, DAPT duration after PCI should be as short as possible in patients with prior hemorrhagic stroke. However, DAPT duration after PCI was similar in patients with prior hemorrhagic stroke and in patients with no‐prior stroke, highlighting the need for a practice change. Furthermore, given their markedly higher ICH risk, the threshold for PCI should be higher in patients with prior hemorrhagic stroke, in whom optimal medical treatment alone or CABG might be more preferable to PCI requiring DAPT.

In the PARIS registry, rate of coronary thrombotic events in patients with previous stroke was significantly higher than in those without (7.0% and 3.3%, P=0.01).25 In PLATO, patients with prior stroke had significantly higher rates of MI and stroke than those without (11.5% versus 6.0%, P<0.0001, and 3.4% versus 1.2%, P<0.0001, respectively).12 In line with these previous reports, patients with either prior hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke were associated with higher ischemic risk (ischemic stroke/MI) in the present study. However, the higher ischemic risk in patients with prior hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke was mainly driven by the higher risk for stroke, while their risk for MI was not different from that in patients with no prior stroke. The risk for stroke and MI might be different according to the types of ischemic stroke such as embolic versus athero‐thrombotic stroke. Indeed, the risk for recurrent ischemic stroke was markedly higher in patients with atrial fibrillation than in those without. Considering their higher ICH risk, prolonged DAPT would better be avoided in patients with prior ischemic stroke despite their high ischemic risk, and defining optimal antithrombotic regimen is challenging in patients with prior stroke, representing an unmet clinical need.

Study Limitation

Some limitations to our study should be considered. First, this study is the pooled analysis of the retrospective registry and randomized controlled trials. Despite the adjustment for the study, we could not exclude the possibility for the presence of unmeasured confounding related to the pooling of patients from different types of studies. Second, this analysis includes only Japanese patients and race is well known to be associated with a different ischemic‐to‐bleeding tradeoff. Therefore, we should be cautious to extrapolate the current study results outside of Japan. Third, substantial proportion of patients received ticlopidine as a P2Y12 receptor blocker, which is no longer used in the current clinical practice. Prasugrel or ticagrelor were not available in the enrollment period between 2005 and 2011 in Japan. Considering these differences in antiplatelet therapy, it remains unclear how the findings from this analysis can be translated into current clinical practice. Fourth, patients were enrolled between 2005 and 2011 in this pooled cohort. Many of the patients were treated with protocols that are no longer recommended, so the applicability of the findings to patients in current practice might be somewhat questionable. Fifth, the timing of the onset of prior stroke was unknown in this study. Therefore, we could not evaluate the relationship between the timing of stroke and clinical outcomes after PCI, although the risk for ICH or ischemic events might be different according to the time interval between prior stroke and PCI. Sixth, the details of the types of stroke and stroke severity were unknown in this study. Finally, we did not perform head‐computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging systematically to evaluate the previous history of stroke. Therefore, there is a possibility for underreporting of the previous history of stroke.

Conclusions

Patients with prior hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke as compared with those with no prior stroke had higher risk for ICH and ischemic events (ischemic stroke/MI), but not for non‐intracranial bleeding after PCI.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency in Tokyo, Japan, Abbott Vascular in Tokyo, Japan and Terumo in Tokyo, Japan.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. List of the Participating Centers and the Investigators.

Table S1. Clinical Outcomes Through 3 Years in Patients With or Without AMI

Table S2. Clinical Outcomes Through 3 Years in Patients With or Without Atrial Fibrillation in the Prior Ischemic Stroke Group

Table S3. Clinical Outcomes Between 4‐Month and 3‐Year in Patients With or Without DAPT by the Landmark Analysis at 4‐Month

Figure S1. A, Antiplatelet therapy at the onset of intracranial bleeding. B, Antiplatelet therapy at the onset of ischemic stroke. DAPT indicates dual‐antiplatelet therapy; PCI indicates percutaneous coronary intervention.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the support of the co‐investigators participating in the CREDO‐Kyoto PCI/CABG Registry Cohort‐2, RESET, and NEXT trials.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e013356 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013356.)

References

- 1. Acharya T, Salisbury AC, Spertus JA, Kennedy KF, Bhullar A, Reddy HKK, Joshi BK, Ambrose JA. In‐hospital outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention in America's safety net: insights from the NCDR CATH‐PCI registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:1475–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee JM, Kang J, Lee E, Hwang D, Rhee TM, Park J, Kim HL, Lee SE, Han JK, Yang HM, Park KW, Na SH, Kang HJ, Koo BK, Kim HS. Chronic kidney disease in the second‐generation drug‐eluting stent era: pooled analysis of the Korean multicenter drug‐eluting stent registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:2097–2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang Y, Zhao X, Liu L, Wang D, Wang C, Li H, Meng X, Cui L, Jia J, Dong Q, Xu A, Zeng J, Li Y, Wang Z, Xia H, Johnston SC. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Johnston SC, Amarenco P, Albers GW, Denison H, Easton JD, Evans SR, Held P, Jonasson J, Minematsu K, Molina CA, Wang Y, Wong KS. Ticagrelor versus aspirin in acute stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, Barsan W, Conwit RA, Elm JJ, Kim AS, Lindblad AS, Palesch YY. Clopidogrel and aspirin in acute ischemic stroke and high‐risk TIA. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:215–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, Cimminiello C, Csiba L, Kaste M, Leys D, Matias‐Guiu J, Rupprecht HJ. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high‐risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sacco RL, Diener HC, Yusuf S, Cotton D, Ounpuu S, Lawton WA, Palesch Y, Martin RH, Albers GW, Bath P, Bornstein N, Chan BP, Chen ST, Cunha L, Dahlof B, De Keyser J, Donnan GA, Estol C, Gorelick P, Gu V, Hermansson K, Hilbrich L, Kaste M, Lu C, Machnig T, Pais P, Roberts R, Skvortsova V, Teal P, Toni D, Vandermaelen C, Voigt T, Weber M, Yoon BW. Aspirin and extended‐release dipyridamole versus clopidogrel for recurrent stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1238–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Benavente OR, Hart RG, McClure LA, Szychowski JM, Coffey CS, Pearce LA. Effects of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with recent lacunar stroke. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:817–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, Biller J, Brown M, Demaerschalk BM, Hoh B, Jauch EC, Kidwell CS, Leslie‐Mazwi TM, Ovbiagele B, Scott PA, Sheth KN, Southerland AM, Summers DV, Tirschwell DL. 2018 Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49:e46–e110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, Bravata DM, Chimowitz MI, Ezekowitz MD, Fang MC, Fisher M, Furie KL, Heck DV, Johnston SC, Kasner SE, Kittner SJ, Mitchell PH, Rich MW, Richardson D, Schwamm LH, Wilson JA. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:2160–2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Montalescot G, Ruzyllo W, Gottlieb S, Neumann FJ, Ardissino D, De Servi S, Murphy SA, Riesmeyer J, Weerakkody G, Gibson CM, Antman EM. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2001–2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H, Held C, Horrow J, Husted S, James S, Katus H, Mahaffey KW, Scirica BM, Skene A, Steg PG, Storey RF, Harrington RA, Freij A, Thorsen M. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1045–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bonaca MP, Scirica BM, Braunwald E, Wiviott SD, O'Donoghue ML, Murphy SA, Morrow DA. Coronary stent thrombosis with vorapaxar versus placebo: results from the TRA 2°P‐TIMI 50 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2309–2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, Brindis RG, Fihn SD, Fleisher LA, Granger CB, Lange RA, Mack MJ, Mauri L, Mehran R, Mukherjee D, Newby LK, O'Gara PT, Sabatine MS, Smith PK, Smith SC Jr. 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1082–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA, Collet JP, Costa F, Jeppsson A, Juni P, Kastrati A, Kolh P, Mauri L, Montalescot G, Neumann FJ, Petricevic M, Roffi M, Steg PG, Windecker S, Zamorano JL. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS: the task force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the european society of cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for Cardio‐Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:213–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kimura T, Morimoto T, Furukawa Y, Nakagawa Y, Kadota K, Iwabuchi M, Shizuta S, Shiomi H, Tada T, Tazaki J, Kato Y, Hayano M, Abe M, Tamura T, Shirotani M, Miki S, Matsuda M, Takahashi M, Ishii K, Tanaka M, Aoyama T, Doi O, Hattori R, Tatami R, Suwa S, Takizawa A, Takatsu Y, Kato H, Takeda T, Lee JD, Nohara R, Ogawa H, Tei C, Horie M, Kambara H, Fujiwara H, Mitsudo K, Nobuyoshi M, Kita T. Long‐term safety and efficacy of sirolimus‐eluting stents versus bare‐metal stents in real world clinical practice in Japan. Cardiovasc Interv Ther. 2011;26:234‐245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kimura T, Morimoto T, Natsuaki M, Shiomi H, Igarashi K, Kadota K, Tanabe K, Morino Y, Akasaka T, Takatsu Y, Nishikawa H, Yamamoto Y, Nakagawa Y, Hayashi Y, Iwabuchi M, Umeda H, Kawai K, Okada H, Kimura K, Simonton CA, Kozuma K. Comparison of everolimus‐eluting and sirolimus‐eluting coronary stents: 1‐year outcomes from the randomized evaluation of sirolimus‐eluting versus everolimus‐eluting stent trial (RESET). Circulation. 2012;126:1225–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Natsuaki M, Kozuma K, Morimoto T, Kadota K, Muramatsu T, Nakagawa Y, Akasaka T, Igarashi K, Tanabe K, Morino Y, Ishikawa T, Nishikawa H, Awata M, Abe M, Okada H, Takatsu Y, Ogata N, Kimura K, Urasawa K, Tarutani Y, Shiode N, Kimura T. Biodegradable polymer biolimus‐eluting stent versus durable polymer everolimus‐eluting stent: a randomized, controlled, noninferiority trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:181–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kimura T, Morimoto T, Nakagawa Y, Tamura T, Kadota K, Yasumoto H, Nishikawa H, Hiasa Y, Muramatsu T, Meguro T, Inoue N, Honda H, Hayashi Y, Miyazaki S, Oshima S, Honda T, Shiode N, Namura M, Sone T, Nobuyoshi M, Kita T, Mitsudo K. Antiplatelet therapy and stent thrombosis after sirolimus‐eluting stent implantation. Circulation. 2009;119:987–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. The GUSTO investigators . An international randomized trial comparing four thrombolytic strategies for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:673–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Serruys PW, Ong AT, van Herwerden LA, Sousa JE, Jatene A, Bonnier JJ, Schonberger JP, Buller N, Bonser R, Disco C, Backx B, Hugenholtz PG, Firth BG, Unger F. Five‐year outcomes after coronary stenting versus bypass surgery for the treatment of multivessel disease: the final analysis of the arterial revascularization therapies study (ARTS) randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:575–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, Boam A, Cohen DJ, van Es GA, Steg PG, Morel MA, Mauri L, Vranckx P, McFadden E, Lansky A, Hamon M, Krucoff MW, Serruys PW. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Natsuaki M, Morimoto T, Yamaji K, Watanabe H, Yoshikawa Y, Shiomi H, Nakagawa Y, Furukawa Y, Kadota K, Ando K, Akasaka T, Hanaoka KI, Kozuma K, Tanabe K, Morino Y, Muramatsu T, Kimura T. Prediction of thrombotic and bleeding events after percutaneous coronary intervention: CREDO‐Kyoto thrombotic and bleeding risk scores. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008708 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.008708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Costa F, van Klaveren D, James S, Heg D, Raber L, Feres F, Pilgrim T, Hong MK, Kim HS, Colombo A, Steg PG, Zanchin T, Palmerini T, Wallentin L, Bhatt DL, Stone GW, Windecker S, Steyerberg EW, Valgimigli M. Derivation and validation of the predicting bleeding complications in patients undergoing stent implantation and subsequent dual antiplatelet therapy (PRECISE‐DAPT) score: a pooled analysis of individual‐patient datasets from clinical trials. Lancet. 2017;389:1025–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Baber U, Mehran R, Giustino G, Cohen DJ, Henry TD, Sartori S, Ariti C, Litherland C, Dangas G, Gibson CM, Krucoff MW, Moliterno DJ, Kirtane AJ, Stone GW, Colombo A, Chieffo A, Kini AS, Witzenbichler B, Weisz G, Steg PG, Pocock S. Coronary thrombosis and major bleeding after PCI with drug‐eluting stents: risk scores from PARIS. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2224–2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Myint PK, Kwok CS, Roffe C, Kontopantelis E, Zaman A, Berry C, Ludman PF, de Belder MA, Mamas MA. Determinants and outcomes of stroke following percutaneous coronary intervention by indication. Stroke. 2016;47:1500–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rost NS, Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Murphy SA, Crompton AE, Norden AD, Silverman S, Singhal AB, Nicolau JC, SomaRaju B, Mercuri MF, Antman EM, Braunwald E. Outcomes with edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with previous cerebrovascular events: findings from ENGAGE AF‐TIMI 48 (effective anticoagulation with factor Xa next generation in atrial fibrillation‐thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 48). Stroke. 2016;47:2075–2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. James SK, Storey RF, Khurmi NS, Husted S, Keltai M, Mahaffey KW, Maya J, Morais J, Lopes RD, Nicolau JC, Pais P, Raev D, Lopez‐Sendon JL, Stevens SR, Becker RC. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes and a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack. Circulation. 2012;125:2914–2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. List of the Participating Centers and the Investigators.

Table S1. Clinical Outcomes Through 3 Years in Patients With or Without AMI

Table S2. Clinical Outcomes Through 3 Years in Patients With or Without Atrial Fibrillation in the Prior Ischemic Stroke Group

Table S3. Clinical Outcomes Between 4‐Month and 3‐Year in Patients With or Without DAPT by the Landmark Analysis at 4‐Month

Figure S1. A, Antiplatelet therapy at the onset of intracranial bleeding. B, Antiplatelet therapy at the onset of ischemic stroke. DAPT indicates dual‐antiplatelet therapy; PCI indicates percutaneous coronary intervention.