Abstract

Background

Race influences medical decision making, but its impact on advanced heart failure therapy allocation is unknown. We sought to determine whether patient race influences allocation of advanced heart failure therapies.

Methods and Results

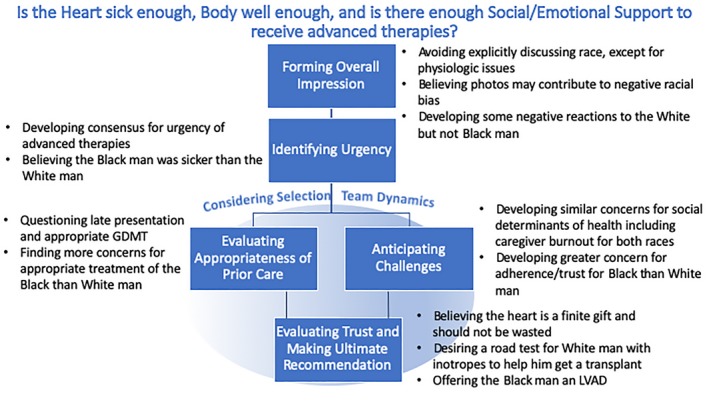

Members of a national heart failure organization were randomized to clinical vignettes that varied by patient race (black or white man) and were blinded to study objectives. Participants (N=422) completed Likert scale surveys rating factors for advanced therapy allocation and think‐aloud interviews (n=44). Survey results were analyzed by least absolute shrinkage and selection operator and multivariable regression to identify factors influencing advanced therapy allocation, including interactions with vignette race and participant demographics. Interviews were analyzed using grounded theory. Surveys revealed no differences in overall racial ratings for advanced therapies. Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator regression selected no interactions between vignette race and clinical factors as important in allocation. However, interactions between participants aged ≥40 years and black vignette negatively influenced heart transplant allocation modestly (−0.58; 95% CI, −1.15 to −0.0002), with adherence and social history the most influential factors. Interviews revealed sequential decision making: forming overall impression, identifying urgency, evaluating prior care appropriateness, anticipating challenges, and evaluating trust while making recommendations. Race influenced each step: avoiding discussing race, believing photographs may contribute to racial bias, believing the black man was sicker compared with the white man, developing greater concern for trust and adherence with the black man, and ultimately offering the white man transplantation and the black man ventricular assist device implantation.

Conclusions

Black race modestly influenced decision making for heart transplant, particularly during conversations. Because advanced therapy selection meetings are conversations rather than surveys, allocation may be vulnerable to racial bias.

Keywords: decision making, healthcare delivery, healthcare disparities, heart failure, heart transplant

Subject Categories: Transplantation, Heart Failure, Health Services, Race and Ethnicity, Treatment

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Interviews revealed that the decision‐making process was based on medical appropriateness, comorbidities, and strength of the social and emotional support system.

Compared with the white man, black race negatively influenced the allocation of heart transplant modestly.

The racial differences in the decision‐making process for heart transplant were more pronounced during interviews than during surveys.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Race modestly influences the decision‐making process for advanced heart failure therapies.

Further investigation should address tactics to reduce racial bias in decision making for advanced heart failure therapies.

Introduction

Racial disparities persist in heart failure (HF).1 Blacks have the highest rates of HF and greatest mortality compared with other ethnicities.1 Compared with whites, blacks are less likely to receive HF medications2 and device therapies3 and less likely to receive care by a cardiologist.4 Insurance broadening has contributed to increased access to heart transplants among blacks but has not fully eliminated disparities.5 Ventricular assist device (VAD) implantation rates also remain below expected rates for blacks.6

Healthcare professionals’ decision‐making processes may contribute to racial disparities in HF. A recent meta‐synthesis of medical qualitative studies concluded that physicians’ clinical decisions were influenced by patient ethnicity.7 However, the role of race in the decision‐making process for advanced HF therapies, such as heart transplants and VAD, is unknown.

The decision‐making process for advanced therapies for HF is complex. Healthcare professionals must determine the best therapy for patients while also carefully assessing for contraindications for advanced HF therapies. Most contraindications to advanced therapies exist on a spectrum, and the point at which advanced therapies should not be pursued is subjective.8, 9 Subjectivity at these decision points creates vulnerability for racial bias.10

We sought to determine whether race influences the decision‐making process for advanced HF therapies. Quantitative surveys and qualitative think‐aloud interviews were performed to understand the following: (1) general decision process, (2) how race influences the decision process, and (3) which factors have the greatest influence on the decision process when considering patients of black and white race.

Methods

Study Design, Sample, and Recruitment

A simultaneous mixed‐methods approach was performed from September 2018 to February 2019 among members of the Heart Failure Society of America, a national organization of HF professionals, including postdoctoral trainees, nurses, pharmacists, pharmaceutical representatives, nurse practitioners, and physicians. Eligible members (N=1432) included all healthcare professionals who participate in the decision‐making process for advanced HF therapies in adults in the United States. Participants were identified through membership directory (N=1929), but advanced therapy allocation roles were not available and exclusion estimates may be underestimated. Self‐report during consent (n=180), inaccurate e‐mail address (n=49), and electronic search (n=268) identified a total of 497 ineligible participants. A census approach was used, in which electronic surveys were e‐mailed to all members in repeated waves through Qualtrics. Among invitations, 422 participated (29% response rate), which is consistent with survey responses for healthcare professionals11, 12 and higher than cardiovascular society survey response rates.13 This would also provide a priori 99% power to detect 0.9‐unit difference in scores (1–10) with 1‐unit SD for supporting advanced therapies in black versus white men.14 Simultaneously, in‐person or videoconference think‐aloud interviews were performed with surveying among a purposeful sample of members representing diverse ethnicities, sexes, position, and geographic institution. Snowball sampling was used to help identify 44 professionals for interviews.15 Trained research assistants (E.Y., A.L.) performed, audio recorded, and collected field notes for all interviews. Study participants provided verbal consent and received incentives worth $10 (US dollars). This study was approved by the University of Arizona Institutional Review Board. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. To minimize the possibility of unintentionally sharing information that can be used to reidentify private information, only a subset of data will be available.

Vignette

Participants were blinded to study objectives until participation was complete and were randomized 1:1 to white man or black man. Race was indicated using text, photograph, and ethnic‐sounding names.16 Photographs were selected from a normalization study conducted by the primary investigator's (K.B.) team (S.S., L.L., K.H.T., L.Z.). The 2 study photographs differed only by race, having similar hairstyle, clothing, and physical build; they were similarly rated for age, attraction, intelligence, health, facial expression, and trustworthiness (Table S1). The vignettes were identical with the exception of race. The vignette described a patient with end‐stage HF with a complex history, including multiple relative contraindications for advanced therapies, such as reduced social support, reduced treatment adherence, financial instability, and history of remote drug use, obesity, and mild levels of diabetes mellitus, kidney dysfunction, and peripheral vascular disease (Table S2).

Survey Instrument

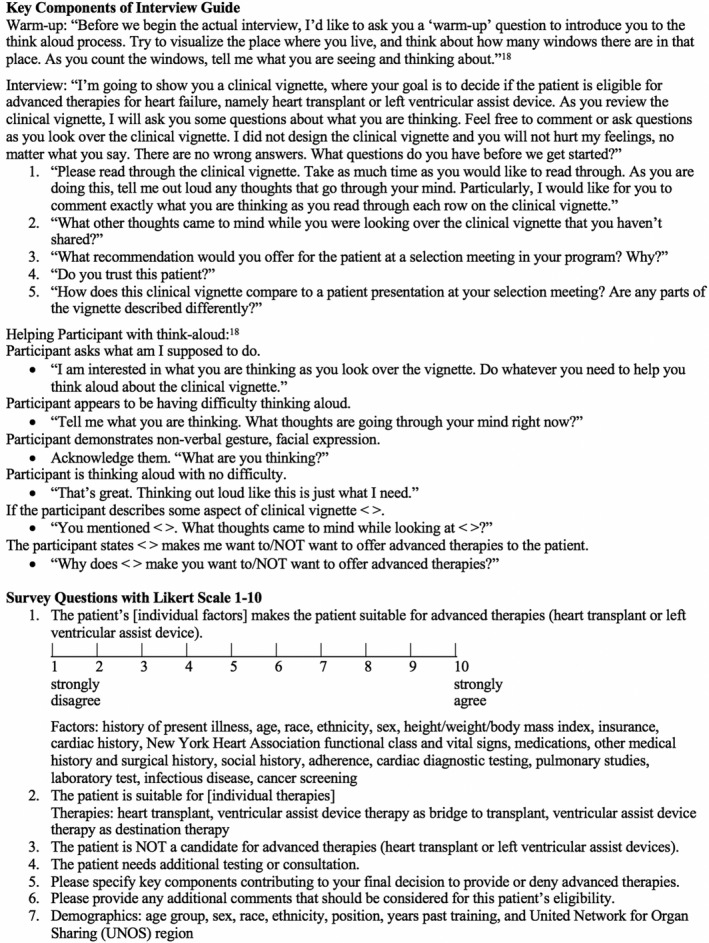

Participants were asked to rate on a Likert scale (1–10, strongly disagree to strongly agree) how well individual factors make the patient suitable for advanced HF therapies (Figure 1). Final recommendations for heart transplant, bridge to transplant VAD (future candidate for transplant), destination VAD (not a candidate for transplant), and no advanced therapies were individually elicited on a Likert scale. Write‐in responses were invited to describe key reasons for final decisions and additional pertinent comments. Demographic information was also collected.

Figure 1.

Interview guide and survey questions. Warm‐up questions and helping participant with think aloud were from Shafer and Lohse instructions on cognitive interviewing.19

Interview Guide

Think aloud, a form of cognitive interviewing, is an established method of qualitatively evaluating the decision‐making process.17, 18 The interview guide was framed on the cognitive interview guide by Shafer and Lohse, which includes probes to assist with thinking aloud.19 Participants were prompted about thoughts on patient candidacy for advanced therapies as they read through each section of the vignette (Figure 1). Participants were asked for a final recommendation for type of advanced therapy and about whether the participant trusted the patient. Participants were also asked to detail how the vignette compared with patient presentations during their own selection meetings.

Statistical Analysis

Surveys were considered complete if all 18 survey factor variables plus need for additional testing (Figure 1) and 4 outcome variables (heart transplant, bridge to transplant VAD, destination therapy VAD, and no advanced therapies) were given. The exception was for the paper surveys from interview subjects for which only the 4 outcome variables were required for inclusion (excluded 5 participants). Simple imputation (median values) was used for missing values from the factor variables (7 values from 5 participants). Multiple imputation was used for missing values for participant‐demographic questions (57 missing values from 21 participants). Predictive mean matching was used with the R package “mice.”20 For all analyses, ordinary least squares regression was used on a transformed response variable to account for nonnormality. The t‐test was used to compare 4 outcome results by vignette race. A 2‐stage approach was used to analyze the survey data. This was performed in the interest of avoiding overparameterization with the large number of variables, as well as because of the use of multiple imputation on the participant demographics. First, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO)21 was used to perform variable selection on the 19 factors and the interaction of each of those factors with vignette race (a total of 38 parameters) for each response variable. The tuning parameter for LASSO (λ) was selected via 10‐fold cross validation. For each response variable, the value of λ giving mean‐squared error within 1 SD of the minimum was used. The R package “glmnet” was used for the LASSO analysis.22 Last, once a baseline model of important factors was established for each response, all demographic variables and the interactions of all demographic variables with vignette race were added. Model estimates and SEs were based on pooled values from 20 imputations.

Think‐aloud interviews underwent thematic analysis using grounded theory while blinded to the vignette patient's race. Then, results were unblinded and categories were compared according to race. The stepwise process included the following: (1) open coding: identifying themes (patterns) until reaching saturation (absence of new themes that designates appropriate sample size23), (2) central phenomenon: exploring themes to arrive at a central category, (3) axial coding: connecting categories, and (4) selective coding: generating a model representing the decision‐making process.24 Rigor was established through credibility (validation of interview response with survey response), transferability (debrief with advanced HF cardiologist [N.S.]), and confirmability (including trained interviewers [E.Y., A.L.] and 2 independent analysts [N.P., M.H.] who performed the entire qualitative analyses with differences arbitrated by an independent qualitative expert [J.C.] and the primary investigator [K.B.]).25 An audit trail and codebook were maintained throughout the study.

Results

Participants were randomized to white (N=204 survey, n=22 interview) and black (N=218 survey, n=22 interview) man patient vignettes similarly across demographics (Table 1, Table S3). Half or more of participants who completed surveys and interviews were aged ≥40 years, men, non‐Hispanic white, cardiologist or cardiothoracic surgeons, with <11 years past training. Participants were dispersed similarly throughout the United Network for Organ Sharing regions (Figure S1), with the exception of interview participants missing from region 6.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Demographics | White Man | Black Man | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vignette (N=204) | Vignette (N=218) | ||

| Age, y | 0.76 | ||

| <40 | 82 (40.2) | 82 (37.6) | |

| 40 | 119 (58.3) | 129 (59.2) | |

| Unknown | 3 (1.5) | 7 (3.2) | |

| Sex | 0.34 | ||

| Men | 107 (52.5) | 125 (57.3) | |

| Women | 92 (45.1) | 87 (39.9) | |

| Unknown | 5 (2.5) | 6 (2.8) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.83 | ||

| Minority | 59 (28.9) | 67 (30.7) | |

| Non‐Hispanic white | 137 (67.2) | 145 (66.5) | |

| Unknown | 8 (3.9) | 6 (2.8) | |

| Position | 0.83 | ||

| Noncardiologist | 59 (28.9) | 65 (29.8) | |

| Cardiologist or cardiothoracic surgeon | 142 (69.6) | 146 (67.0) | |

| Unknown | 3 (1.5) | 7 (3.2) | |

| Past training, y | 0.95 | ||

| <11 | 113 (55.4) | 118 (54.1) | |

| 11 | 89 (43.6) | 90 (41.3) | |

| Unknown | 2 (1.0) | 10 (4.6) | |

| UNOS region | |||

| 1 | 14 (6.9) | 13 (6.0) | 0.30b |

| 2 | 21 (10.3) | 21 (9.6) | |

| 3 | 13 (6.4) | 13 (6.0) | |

| 4 | 16 (7.8) | 12 (5.5) | |

| 5 | 33 (16.2) | 34 (15.6) | |

| 6 | 3 (1.5) | 7 (3.2) | |

| 7 | 29 (14.2) | 25 (11.5) | |

| 8 | 16 (7.8) | 12 (5.5) | |

| 9 | 14 (6.9) | 13 (6.0) | |

| 10 | 25 (12.3) | 22 (10.1) | |

| 11 | 17 (8.3) | 39 (17.9) | |

| Unknown | 3 (1.5) | 7 (3.2) |

Data are given as number (percentage). Interviewed participants meeting exclusion criteria for survey analysis because of missing values for therapy allocation are not included in this table (white man vignette n=2, black man vignette n=3). UNOS indicates United Network for Organ Sharing.

The χ2 test for P value excludes unknowns because small values of unknown provide inaccurate approximation.

The UNOS region P value approximation may be inaccurate.

Survey Results

The favorability for heart transplant (mean rating: white, 7.08 [95% CI, 6.74–7.43]; black, 7.28 [95% CI, 6.97–7.58]), bridge to transplant VAD (white, 7.61 [95% CI, 7.28–7.93]; black, 7.74 [95% CI, 7.44–8.05]), destination VAD (white, 6.84 [95% CI, 6.47–7.21]; black, 7.17 [95% CI, 6.82–7.53]), and no advanced HF therapies (white, 2.39 [95% CI, 2.15–2.63]; black, 2.23 [95% CI, 1.99–2.47]) was similar for white and black man vignettes. Results for interview participants were also quantitatively similar for the white and black man vignettes (Table S4). Variables selected via LASSO for heart transplant that had a positive effect on allocation included the following (in order of greatest to least magnitude): adherence, social history, other medical and surgical history, laboratory tests, history of present illness, and cardiac diagnostic testing (Table 2). Need for additional testing or consultation had a negative effect on transplant allocation. Variables selected via LASSO for bridge to transplant VAD only had a positive effect on allocation. In order of greatest to least magnitude, these included the following: social history, other medical and surgical history, laboratory tests, adherence, and cardiac diagnostic testing. For destination therapy VAD, no factors were selected as important by LASSO. For allocation to no advanced therapy, the LASSO selected factors included the following: need for additional testing or consultation as a positive effect (supporting no advanced therapies) and the following factors as negative effects on allocation (supporting advanced therapy): history of present illness, adherence, other medical or surgical history, laboratory tests, cardiac diagnostic testing, social history, and height/weight/body mass index. The interactions with vignette race and each survey factor were not selected as important in the LASSO analysis.

Table 2.

Factors Influencing Decision Making for Advanced Therapies From Stage 1 LASSO and Stage 2 Multivariable Regression Models

| Stage 1 LASSO Regression Model | Coefficient | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Transplant | BTT VAD | DT VAD | Not Candidate | |

| HPI | 0.032 | ··· | ··· | −0.074 |

| Age | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· |

| Race or ethnicity | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· |

| Sex | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· |

| Height/weight/BMI | ··· | ··· | ··· | −0.0003 |

| Insurance | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· |

| Blood type and PRA class | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· |

| Cardiac history | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· |

| NYHA functional class and vital signs | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· |

| Medications | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· |

| Other medical history and surgical history | 0.058 | 0.080 | ··· | −0.047 |

| Social history | 0.085 | 0.137 | ··· | −0.016 |

| Adherence | 0.123 | 0.020 | ··· | −0.055 |

| Cardiac diagnostic testing | 0.027 | 0.009 | ··· | −0.031 |

| Pulmonary studies | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· |

| Laboratory tests | 0.054 | 0.040 | ··· | −0.043 |

| Infectious disease | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· |

| Cancer screening | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· |

| Additional testing/consultation needed | −0.003 | ··· | ··· | 0.003 |

| Black vignette | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· |

| Stage 2 Demographic Factors’ Multivariable Regression Model | Parameter Estimate (95% CI) | P Value | Parameter Estimate (95% CI) | P Value | Parameter Estimate (95% CI) | P Value | Parameter Estimate (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White non‐Hispanic | −0.13 (−0.47 to 0.21) | 0.44 | 0.18 (−0.18 to 0.55) | 0.32 | 0.49 (−0.02 to 1.00) | 0.06 | −0.22 (−0.53 to 0.10) | 0.18 |

| Women | 0.09 (−0.29 to 0.46) | 0.65 | 0.19 (−0.20 to 0.58) | 0.34 | 0.27 (−0.27 to 0.82) | 0.33 | 0.06 (−0.29 to 0.40) | 0.75 |

| Aged ≥40 y | 0.39 (−0.04 to 0.83) | 0.08 | 0.25 (−0.20 to 0.71) | 0.27 | 0.03 (−0.62 to 0.68) | 0.93 | −0.17 (−0.57 to 0.23) | 0.40 |

| ≥11 y Past training | −0.49 (−0.92 to −0.06)a | 0.02 | −0.51 (−0.96 to −0.07)a | 0.03 | 0.12 (−0.52 to 0.77) | 0.71 | 0.49 (0.10 to 0.88)a | 0.01 |

| Cardiologist | 0.04 (−0.37 to 0.46) | 0.84 | 0.12 (−0.31 to 0.55) | 0.58 | 0.01 (−0.59 to 0.61) | 0.98 | −0.16 (−0.54 to 0.22) | 0.41 |

| Black vignette | 0.20 (−0.53 to 0.93) | 0.58 | 0.15 (−0.61 to 0.92) | 0.69 | 0.76 (−0.33 to 1.86) | 0.17 | −0.05 (−0.74 to 0.64) | 0.89 |

| White non‐Hispanic and black vignette interaction | −0.04 (−0.51 to 0.42) | 0.86 | −0.35 (−0.84 to 0.15) | 0.17 | −0.46 (−1.17 to 0.26) | 0.21 | 0.42 (−0.03 to 0.86) | 0.06 |

| Women and black vignette interaction | 0.00 (−0.50 to 0.50) | 0.99 | 0.10 (−0.42 to 0.62) | 0.71 | −0.19 (−0.94 to 0.55) | 0.61 | −0.24 (−0.71 to 0.23) | 0.32 |

| Aged ≥40 y and black vignette interaction | −0.58 (−1.15 to −0.0002)a | 0.0499 | −0.25 (−0.85 to 0.36) | 0.42 | 0.28 (−0.59 to 1.15) | 0.53 | −0.06 (−0.62 to 0.49) | 0.83 |

| ≥11 y Past training and black vignette interaction | 0.52 (−0.05 to 1.09) | 0.08 | 0.50 (−0.10 to 1.10) | 0.10 | −0.35 (−1.21 to 0.51) | 0.42 | −0.19 (−0.74 to 0.36) | 0.49 |

| Cardiologist and black vignette interaction | −0.14 (−0.69 to 0.41) | 0.61 | −0.11 (−0.69 to 0.46) | 0.70 | −0.27 (−1.10 to 0.55) | 0.52 | −0.09 (−0.61 to 0.44) | 0.74 |

Positive values denote support for decision, and negative values denote disapproval for decision; ellipses indicate 0 coefficient and no influence on decision making. Each factor was also included as an interaction with black vignette. These interactions were zero coefficients in stage 1 of LASSO regression and do not include participant demographics. Stage 2 multivariable model included factors with nonzero coefficient from LASSO model to determine influence of participant demographics. BMI indicates body mass index; BTT, bridge to transplant; DT, destination therapy; HPI, history of present illness; LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PRA, panel reactive antibody; VAD, ventricular assist device.

Multivariable regression P value factors with significance <0.05.

After LASSO and multivariable regression, significant participant demographic factors negatively influenced allocation to heart transplant, including ≥11 years of past training (−0.49 [95% CI, −0.92 to −0.06]) and interaction of age ≥40 years by black vignette (−0.58 [95% CI, −1.15 to −0.0002]). Overall among healthcare professionals aged ≥40 years, the white vignette trended more favorably for transplant over the black vignette but was not significantly different (white vignette, 0.39 [95% CI, −0.04 to 0.83]; black vignette, −0.18 [95% CI, −0.56 to 0.19]). Bridge to transplant VAD was negatively influenced by ≥11 years of past training (−0.51 [95% CI, −0.96 to −0.07]). No participant demographic factors significantly influenced the decision for destination therapy VAD. Advising against candidacy for advanced therapies was positively influenced by ≥11 years of past training (0.49 [95% CI, 0.10‐0.88]).

Think‐Aloud Interview Results

Using grounded theory, a 3‐pronged central phenomenon guiding decision making for advanced HF therapies emerged: Is the heart sick enough? Is the body well enough? Is there enough social/emotional support to make it through the process? The decision‐making process was sequentially directed by 5 themes, with 2 themes occurring simultaneously: (1) forming an overall impression, (2) identifying urgency, (3a) evaluating the appropriateness of prior care, (3b) anticipating challenges, and (4) evaluating trust and making the ultimate recommendation (Table 3, Figure 2). Themes were further characterized by 12 subthemes describing racial similarities and differences affecting the decision‐making process. Exemplar quotes illustrate the descriptions of the 5 major themes in the following section.

Table 3.

Themes and Subthemes With Illustrative Quotations

| Central Phenomenon: Is the Heart Sick Enough? Is the Body Well Enough? Is There Enough Social/Emotional Support to Make It Through the Process? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Themes | Illustrative Quotations (Participant Race) | |

| Subthemes | Vignette Type | |

| Forming an overall impression | ||

| Black |

“…he looks clean and well groomed. You can tell that his beard has been combed. He is of darker skin so non‐Caucasian; I think it's actually difficult to tell what ethnicity this patient is based on the picture anyhow… That's about all I notice about the gentleman.” (white) “Because they look well‐kept, it gives me a sense that they may be compliant with medical therapy. Since they take the time to trim their beard, they probably are detail‐oriented. That's my initial impression” (minority) |

|

| White |

“It looks like a middle‐aged man. He is not smiling, and he's bald… He's got a goatee, well‐trimmed. Hard to tell what his teeth look like…for me, a big part of the physical exam is always the oral exam….I would not lean one way or another just based on how he looks.” (minority) “He doesn't look that sick when I look at him. He's not heavy and I don't see any JVD standing up so he's got good fill‐out of his face and temple area and stuff. Looks young. Lots of options, just looking at him” (white) |

|

| Avoiding explicitly discussing race, except for physiologic issues | Black |

“African‐American, I would probably send genetic testing for amyloid” (minority) “One of the few things that his race would affect would be I guess interpreting PSA, so, it's good that his PSA is negative…” (white) |

| White |

“I'm looking at a white Caucasian male which I know affects survival and risk…” (white) “His picture matches his age and the other description, right non‐Hispanic. So that's about it. Doesn't look malnourished, doesn't look cachectic… It's just a head shot. This photo's neutral.” (white) |

|

| Believing photographs may contribute to negative racial bias | Black | “…we don't usually say what the ethnicity of the person is… Yeah, we don't have a picture of the person usually either…” (white) |

| White |

“I am certain that there is a bias, especially when it comes to ethnic minorities and women in general…” (minority) “…I just think it's interesting, because I do think people are swayed by that [knowing race]… And I just think that's wrong. I should not know the sex, anything else.” (white) |

|

| Developing some negative reactions to the white but not black man | Black |

“Looks like a typical gentleman that you would see, stated age; doesn't look terribly ill.” (minority) “…well‐kept, good hygiene, neatly trimmed beard. That's all I would say based on the photo.” (minority) |

| White |

“…if I look at the face, that scares the heck out of me. I'll be honest with you, it sways me… I think he looks scary. Honestly, first judgement when you see him, he looks like a prisoner…it looks like a mugshot photo of somebody.” (white) “My first reaction was cover the face, because I don't want that information… Because I think that you have a bias right there… I think most people wouldn't like him. He doesn't look very friendly to start with.” (white) |

|

| Identifying urgency | ||

| Black | “So, all of these things are signs to me that things are not going well with his illness and that he could be or is in the end stages of HF.” (white) | |

| White |

“There's no question about the need of more advanced care.” (white) “And then the high number of hospitalizations… No matter what we decide at this committee meeting, we know that this guy is probably not going to be alive for much longer.” (white) |

|

| Developing consensus for urgency of advanced therapies | Black | “…things are really starting to mount that he's got advanced disease.” (white) |

| White |

“He needs advanced therapies…I will say, I will just list him for transplant…he's very advanced.” (white) “The other things jump out in terms of urgency. So the fact that he's had four hospitalizations in the past 6 months, his mortality rate is very high… so it's not as if we have a long time to kind of consider his candidacy.” (minority) |

|

| Believing the black man was sicker than the white man | Black |

“Multiple hospitalizations in the past 6 months is a terrible prognostic indicator, moreover, it would insinuate that he has a terrible quality of life… His dizziness and lightheadedness with walking minimal distance suggests that he is a terribly ill man, and he also [has] ventricular arrhythmia, so he has a very high‐risk profile for dying.” (white) “I don't have too many patients in my clinic like this that are not being actively considered for advanced therapies, or…being referred to hospice or at least a palliative care visit. It's time to be thinking about those things, yeah.” (white) “I think he's too sick…he has a sick heart, but otherwise, he's favorable for transplant listing or VAD I would say, really…he's going to die unless something is done soon…” (white) “You know given how sick he is and that we need to make a decision quickly on this gentleman. My thought given his blood type is that he's somebody we're gonna need to move really quickly to an LVAD as a bridge hopefully to transplantation.” (white) |

| White |

“My sense is he's not terribly frail…” (white) “He doesn't seem like he's critically ill, based on his PMH didn't tell me that…” (white) |

|

| Evaluating the appropriateness of prior care | ||

| Black | “Certainly, if he's not on good therapy, maybe he would be better if he was on better therapy…” (white) | |

| White |

“Adherence, lost to follow‐up for a few years when he didn't have health insurance, we see that all the time. I think it's a horrible statement in our country, but we haven't fixed that.” (white) “I just want to make sure that someone has tried to get him [on] a good medical therapy and that he is taking what he's been able to…” (white) |

|

| Questioning late presentation and appropriate guideline‐directed medical therapy | Black | “I'd also question whether or not he is adequately treated from a medical standpoint, and whether or not he has been discharged prematurely, and whether or not he is on optimal medical therapy in the hopes of precluding another hospitalization.” (white) |

| White |

“Does he have, has he been, is he on adequate therapy? Is there anything that could be done, that can be done to improve his trajectory?” (white) “This is our typical kind of patient…We usually get them too late and it doesn't matter. I mean, we still do exactly what we need to do but it's just… the systems are not sophisticated enough to capture these patients. For example, this guy was in the hospital 4 times in the last 6 months. Could we have gotten him, in an ideal world, after his second one and with his kidneys and liver in better shape?” (white) |

|

| Finding more concerns for appropriate treatment of black than white man | Black |

“Has he not been triaged and treated properly?” (minority) “…he seems to have a pretty malignant course in that he was just diagnosed a year ago and…doesn't seem to have responded to medical management unfortunately. Lots of hospitalizations which is a poor prognostic indicator.” (white) “It sounds like he's a gentleman despite having significant heart failure… probably has not been exposed to heart failure specialists previously.” (white) |

| White |

“I think it was a pretty thorough workup and presentation…” (white) “Typical stuff. It looks like he's had a reasonable workup.” (white) |

|

| Anticipating challenges | ||

| Black |

“So, his size and blood type would infer that if he is indeed a candidate for heart transplant, his time on the wait list would be considerable.” (white) “The social history is concerning for whether or not he has adequate social and financial resources to tolerate a VAD or a transplant…” (white) |

|

| White |

“I think the fact that we can't put him on medications is a major issue. When we consider advanced therapies, certainly, taking a pill is a lot easier than going through major cardiac surgery. We try to max out medications first…” (white) “… social support and kind of having backup plans as what to do that like any other thing with heart failure patients is a constant struggle but it can be overcome if you make them think that way. Prepare, have a backup plan. You know, work on it. Talk to people. Have a wider net of support, not just your wife, not just your brother.” (minority) |

|

| Developing similar concerns for social determinant of health, including caregiver burnout for both races | Black |

“So if you have a patient, let's say, that may not have the [social] support for transplant then maybe VAD may be an option because there's less visits…. that's something I would consider in this patient too, if we find that the support is not adequate for transplant.” (minority) “I think healthcare literacy is a major issue. I don't think this is a malignantly noncompliant patient. He lets life overwhelm him as a subjective judgment. So I would say this is something we can help modify. It's not a deal breaker.” (minority) |

| White |

“…I don't want your wife to burn out. She's maintaining 2 children, household, and taking care of you so she needs help. And if he says I can't find anybody I say I cannot move forward with transplant or VAD if you can't come up with a second person. Because it's not fair to his wife.” (minority) “But he's kind of drawing the short straw when it comes to the social determinants of health. He sounds resource poor, lost his job, doesn't even have disability yet.” (white) |

|

| Developing greater concerns for adherence/trust for black than white man | Black |

“Adherence… Lost to follow‐up for a couple of years when he didn't have healthcare insurance… Something's not fitting here. Is he lying to us? Was he not working for the Postal Service? The social worker will need to sort that out…” (minority) “He's seeking disability. I don't like the word seeking… It's been 6 months. What kind of financial support is he going to have?” (minority) “It makes me wonder what his outpatient situation has been like and what also his compliance issue has been with his outpatient care…” (minority) |

| White |

“The fact that he's had, is married or would have had a significant other that's working lends credibility to their ability to take care of the needs that come along with really advanced therapy…” (white) “I'd say the adherence part doesn't push me away from advanced therapies. It may push me towards LVAD first and say if you miss an appointment or maybe it's not quite as a big a deal….it gives me some time to get to know him first before he's in a stage where he needs to take immunosuppression and have it tightly regulated and get labs and be compliant.” (white) |

|

| Evaluating trust and making the ultimate recommendation | ||

| Black |

“I don't have reason not to… It sounds like he was a guy who worked all his life… I don't trust anyone really but I trust that he wants to live, and if that's the case then I'll give him a shot…” (minority) “I don't have a longitudinal history with him… I don't like to use the word trust. I would use the word has this person shown sufficient compliance and understanding of liability…” (minority) “He seems pretty clean and straightforward based on what I'm presented. I mean it's one thing, again, you know meeting somebody and reading about somebody are 2 totally different things.” (minority) |

|

| White |

“It goes back to the whole photo. So, if I didn't have the photo and I'm looking at the facts, we would [trust him]. The answer is, this patient has tried.” (white) “Neither one's on the table until I get to know him better, you know…” (white) |

|

| Believing the heart is a finite gift and should not be wasted | Black |

“If there isn't [adequate social support] and there's still a gray area then I would be pushed a little more towards VAD than transplant…there's a limited number of organs available whereas VADS, there's no limitation on that. So, we describe it as a precious resource, the heart…” (white) “We really do need to show consistency of follow‐up just given our obligations with transplant, that we were good stewards of the organs…” (white) “I know I keep saying social compliance and I think it's more for respect for an organ honestly…” (minority) |

| White |

“And if you take a 20‐year‐old heart and put it in somebody who's only going to get 5 years out of it, you haven't really served the donor appropriately. And that might be something that pushes me more towards going towards a VAD…. I don't want to take a heart and give it to somebody who's going to mess it up in 5 years.” (white) “…these therapies are not only very expensive, but are limited, and so, in the world of ethics, and trying to maximize utility for everybody, you really don't want to use resources on somebody who is not going to benefit fully from them because of things like nonadherence and variable compliance.” (minority) “At the same time we need to pick candidates who are capable of taking care of the vital resource that they were provided, be it a VAD and/or a transplant, obviously transplant more. And it's my job ethically to make sure he's able to do that. If some poor mother's going to donate a 17‐year‐old's heart, I need to know that this person's capable of taking care of it.” (white) |

|

| Desiring a road test for white man with inotropes to help him get a transplant | White |

“…we will ask him to come to clinic every week, show compliance to his medication regimen, show that he can come to clinic appointments, bring his social support people with him…” (minority) “I still think he's a candidate [for transplant]. Maybe he would benefit from some IV inotropes in the meantime…” (white) “If he has an adequate caregiver plan and can get his diabetes under good control would place on inotropes/IABP and list for transplant.” (white) “I'm thinking he should be put on inotropes and we should get to know him…” (white) “I would like to have some bridge to show me that he's compliant… Start with an inotrope… See if they can handle it.” (minority) |

| Offering the black man a VAD | Black |

“It's not clear what the equipoise is here for this but I think most people would VAD him too, at this point.” (white) “I would lean a little bit more towards an LVAD just given the issues with the noncompliance…” (minority) “…[if he won't take a hep c heart] he's probably a candidate for LVAD cuz he's pretty sick…” (white) “I would say that I don't know right or wrong, I think sometimes in cases where we don't have the ability to wait, we typically give the patients the benefit of the doubt for an LVAD, probably not for transplant.” (white) “But I think in this case you could go either way. And then really it's up to him or his financial plus family support that if he can go straight to transplant because obviously the patient and the family has to be very, very compliant with therapy. So they have to come to the clinic visit and then also take medications and stuff like that. If there is any concern from that perspective, then LVAD might be a better option.” (minority) “…this guy absolutely merits inotropic support. And the question is, is the inotropic support going to be a bridge to compliance? Is the inotropic support going to be a bridge to optimization for LVAD? Or is the inotropic support going to be a bridge to transplant listing? We don't know that yet.” (minority) “…I would lean a little bit more towards an LVAD just given the issues with the noncompliance…cuz we can work with [the A1C] and obesity… Those are from what I know now, fixable problems…but I think the noncompliance, that is definitely a hindrance to ideal care.” (minority) “I think we would definitely consider this man for an LVAD at our center pretty soon. I think transplant is a little bit harder to be very enthusiastic about…” (minority) |

| White |

“I would push him to be a transplant candidate instead of a VAD candidate… He would potentially be a great candidate for transplant” (white) “At this stage, if all those statements that I made are presumed, that there's nothing else missing, that he doesn't have sarcoidosis, he doesn't have active inflammation in his heart, I would probably recommend that he goes through a transplant.” (minority) |

|

HF indicates heart failure; IV, intravenous; IABP, intra‐aortic balloon pump; JVD, jugular venous distention; LVAD, left VAD; PSA, prostate specific antigen; PMH, past medical history; VADs, ventricular assist devices.

Figure 2.

Decision‐making process for allocating advanced heart failure therapies. Themes from Grounded Theory of Think‐Aloud Interviews. GDMT indicates guideline‐directed medical therapy; LVAD, left ventricular assist device.

Forming an overall impression

Participants developed an overall impression of the patient from the photograph. Some participants suggested the photograph contributed to negative bias about race and socioeconomic position for both the white and black vignettes. Others felt that the photograph had little impact on their decisions and found race irrelevant with the exception of making decisions about genotyping. Several participants found the photographs to be more detrimental toward the white than the black vignette.

“…a few times a staff member has given the presentation and decided to actually put the photo [in], and I decided that that was not good, because you have an opinion that is now not based on facts on paper, but whether you thought the person was lovely or not.” (white participant/white vignette)

Identifying urgency

The second step in decision making included figuring out the patient's severity of illness and need for advanced HF therapies. All participants surmised that both the white and black vignette patients had end‐stage HF on the basis of the history of present illness. Participants believed that developing consensus for urgency was an important step in the decision‐making process. However, participants displayed more consistent concern for higher illness acuity within the black than the white vignette.

“…I think he is going to need to have a workup and relatively expeditious action. I don't think this is the kind of patient you can sit on for a long time and hope that they're going to do well. So I would say that I would not be dragging my feet…” (white participant/black vignette)

Evaluating the appropriateness of care

In the third step, participants questioned whether the patients had received appropriate care before referral. Participants wondered whether guideline‐directed medical therapy had been provided correctly and why patients were presenting so late for evaluation for advanced HF therapies.

“… If he was my own patient, I would probably try myself to see if indeed he is intolerant. I would have to do a very thorough review of his chart to see if he has been given the old college try to confirm absolute intolerance.” (white participant/black vignette) Participants found more concerns about appropriate prior treatment for the black than the white vignette.

Throughout the decision‐making process, participants believed that the selection team dynamics impacted decisions. Hierarchy in selection team seating, role, and opinion were described during actual advanced HF therapy selection meetings.

“But at an actual selection meeting, it's such an interesting sociologic study because you always have the people with the most power and seniority…at the front of the room. They're the ones who make the decisions. Then the underlings sit in the back of the room…then somebody who knows the patient might chime in…with their usual strong opinion that may or may not be completely rational in a given clinical situation.” (white participant/white vignette)

Anticipating Challenges

In this simultaneous third step, participants also began anticipating barriers to advanced HF therapies. Participants were concerned about social determinants of health and the risk of caregiver burnout for both the white and black vignettes. Participants developed greater concerns for adherence with the black vignette.

“I know we sometimes use the VAD…like a test to see if they would do well with a heart transplant and because of his non‐compliant appearing issues in the past, that would be why I would lean towards a VAD to foresee if he can be compliant before giving him an organ…it's more of a test to see if…a patient can respect the organ that's given to them.” (minority participant/black vignette)

“Adherence, lost to follow‐up for a couple of years when he didn't have health insurance. That is a red flag for both therapies. You know, these are high resource‐intense therapies that you really do need to maintain… We really do need to show consistency of follow‐up just given our obligation with transplant, that we were good stewards of the organs.” (white participant/black vignette)

“This guy was taking care of himself, just his disease outstripped his ability to manage it…” (white participant/white vignette)

Evaluating Trust and Making the Ultimate Recommendation

The last step in the decision‐making process included evaluating whether the healthcare selection team trusted the patient with advanced HF therapy, which contributed to the final recommendation. Participants believed that the heart is a finite gift and should not be wasted. This contributed to hesitancy with offering a transplant in both the black and white vignettes. However, the final recommendation differed by race. The white vignette was more often offered a “road test” with inotropes to see if he could appropriately manage his care and be listed for heart transplant later. The black vignette was offered a VAD because he was thought to be too ill to wait for transplant.

“I would say that I don't know right or wrong, I think sometimes in cases where we don't have the ability to wait, we typically give the patients the benefit of the doubt for an LVAD [left VAD], probably not for transplant.” (white participant/black vignette)

Discussion

In this first study to robustly address how patient race influences decision making for advanced HF therapies, we found that black race compared with white race modestly influenced allocation to heart transplant, particularly during interviews. Survey ratings for advanced HF therapies were similar for black and white patient vignettes, but analysis revealed that black vignette and healthcare professional aged ≥40 years were subtly associated with opposing heart transplant. Surveys revealed that subjectively assessed factors, including social history and adherence patterns, were significant factors in the decision‐making process. Both factors were described during interviews as negatively influencing allocation of heart transplant, particularly among blacks.

Interviews revealed a stepwise decision‐making process that was influenced by race. Race influenced each of these steps: avoiding discussing race explicitly, believing photographs may contribute to racial bias, believing the black man was more ill and possibly undertreated compared with the white man, developing greater concern for trust and adherence with the black man, and ultimately offering the white man a transplant and the black man a VAD.

Clinical uncertainty can contribute to racial bias in clinical decision making.10, 26 The indications and absolute contraindications for advanced HF therapies are definitive in the guidelines; however, relative contraindications, which are increasing among advanced therapy candidates,27 are open to provider interpretation.9, 28 As observed in this study, healthcare professionals had benevolent goals for the patients in the vignettes but were subtly influenced by patient race.

An extensive literature base has demonstrated that unconscious bias contributes to racial inequalities in medical care.7, 29, 30, 31 Often, racial and ethnic minority patients are perceived negatively by healthcare professionals.7, 29, 30, 31 Bias increases further against minority patients compared with white patients when the patient has a lower socioeconomic position.29 As was illustrated in our study, the black man was viewed as less adherent to therapy than the white man, despite having the same clinical and social history. Over 2 decades ago, similar findings were found among physicians considering cardiovascular catheterizations for black and white patients.14 Although bias was subtly observed in our study, its presence can profoundly affect medical care.32

The stability of advanced therapy programs is based on having good patient outcomes and reasonable patient volumes. Programs may deny candidacy to patients perceived as high risk for poor outcomes because they may threaten the longevity of the advanced therapy program.33 Blacks have higher mortality after heart transplant than whites34 and are known to not receive equitable access to care.4 This could contribute to decisions to offer a heart transplant to the white patient over the black patient. However, programs have demonstrated similar long‐term outcomes after heart transplant for blacks and whites through comprehensive multidisciplinary care.35

Reducing racial inequities in decision making for heart transplant may require several approaches. The first step could include reducing clinical uncertainty by making subjective assessments objective. Subjective assessments of adherence and social support could be replaced with known objective measurements, such as the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale36 and the Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplantation.37 The second step includes awareness that conscious and unconscious bias can contribute to interpretation of assessments.7 Known methods to promote egalitarian treatment of patients and healthcare team members include bias training.38 Healthcare professionals can learn how to recognize biases and work to establish connections that supersede bias.7, 38 Last, patient presentations can be changed so that potentially biasing information is not presented. As described by participants in this study, programs can eliminate photographs and ethnicity identifiers from presentations. This last step would not remove bias from those that have a working relationship with the patient but may prevent other team members involved in decision‐making processes from potentially making a biased decision.

Limitations

The response rate for surveys was 29%. Although this may limit generalization, participants from all US United Network for Organ Sharing regions were represented, with the exception of region 6, in the interviews. Because the membership directory did not distinguish members who routinely allocate advanced HF therapies, the number of eligible respondents is lower than the total number sent the survey. Thus, our actual response rate is unknown, but >29%. Over 10% of participants were interviewed and saturation was achieved, signifying an appropriate sample size. Interviewers were not blinded to study objectives and could have emphasized topics unintentionally during interviews. However, steps were taken to avoid biased interviewing, including a 3‐hour training on think‐aloud protocol and multiple observed practice interviews.

Conclusions

When provided a patient case vignette, HF professionals followed a stepwise process in clinical decision making for advanced HF therapies that addressed medical appropriateness, comorbidities, and strength of social and emotional support systems. Race modestly influenced the decision‐making process. Healthcare providers subtly recommended heart transplant in white patients over black patients, despite identical medical and social history. Racial bias was demonstrated particularly during interviews, which more closely resemble allocation meetings, than in numerical surveys. Because allocation for advanced HF therapies occurs via conversations in group settings rather than through surveys, the influence of race on decision making may be significant and should be addressed.

Sources of Funding

Dr Breathett received support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute K01HL142848, University of Arizona Health Sciences, Strategic Priorities Faculty Initiative Grant, and University of Arizona, Sarver Heart Center, Women of Color Heart Health Education Committee. L. Luy received support from National Institutes of Health R25HL108837.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Table S1. Normalization of Vignette Photos

Table S2. Headshot Photograph of White or African‐American Man

Table S3. Demographics of Think‐Aloud Interview Participants

Table S4. Think‐Aloud Interview Participants Survey Recommendations

Figure S1. UNOS regions.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Sarver Heart Center administrative support from Gilbert Maldonado, Mari Vayre, and Taylor Valenzuela.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e013592 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013592.)

This work was presented at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions, November 16–18, 2019, in Philadelphia, PA.

References

- 1. Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Das SR, Delling FN, Djousse L, Elkind MSV, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Jordan LC, Khan SS, Kissela BM, Knutson KL, Kwan TW, Lackland DT, Lewis TT, Lichtman JH, Longenecker CT, Loop MS, Lutsey PL, Martin SS, Matsushita K, Moran AE, Mussolino ME, O'Flaherty M, Pandey A, Perak AM, Rosamond WD, Roth GA, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Schroeder EB, Shah SH, Spartano NL, Stokes A, Tirschwell DL, Tsao CW, Turakhia MP, VanWagner LB, Wilkins JT, Wong SS, Virani SS; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics—2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139:e56–e66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chan PS, Oetgen WJ, Buchanan D, Mitchell K, Fiocchi FF, Tang F, Jones PG, Breeding T, Thrutchley D, Rumsfeld JS, Spertus JA. Cardiac performance measure compliance in outpatients: the American College of Cardiology and National Cardiovascular Data Registry's PINNACLE (Practice Innovation And Clinical Excellence) program. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:8–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Farmer SA, Kirkpatrick JN, Heidenreich PA, Curtis JP, Wang Y, Groeneveld PW. Ethnic and racial disparities in cardiac resynchronization therapy. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Breathett K, Liu WG, Allen LA, Daugherty SL, Blair IV, Jones J, Grunwald GK, Moss M, Kiser TH, Burnham E, Vandivier RW, Clark BJ, Lewis EF, Mazimba S, Battaglia C, Ho PM, Peterson PN. African Americans are less likely to receive care by a cardiologist during an intensive care unit admission for heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6:413–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Breathett K, Allen LA, Helmkamp L, Colborn K, Daugherty SL, Khazanie P, Lindrooth R, Peterson PN. The Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion correlated with increased heart transplant listings in African‐Americans but not Hispanics or Caucasians. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5:136–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Breathett K, Allen LA, Helmkamp L, Colborn K, Daugherty SL, Blair IV, Jones J, Khazanie P, Mazimba S, McEwen M, Stone J, Calhoun E, Sweitzer NK, Peterson PN. Temporal trends in contemporary use of ventricular assist devices by race and ethnicity. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11:e005008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Breathett K, Jones J, Lum HD, Koonkongsatian D, Jones CD, Sanghvi U, Hoffecker L, McEwen M, Daugherty SL, Blair IV, Calhoun E, de Groot E, Sweitzer NK, Peterson PN. Factors related to physician clinical decision‐making for African‐American and Hispanic patients: a qualitative meta‐synthesis. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5:1215–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mehra MR, Kobashigawa J, Starling R, Russell S, Uber PA, Parameshwar J, Mohacsi P, Augustine S, Aaronson K, Barr M. Listing criteria for heart transplantation: International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation guidelines for the care of cardiac transplant candidates—2006. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:1024–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feldman D, Pamboukian SV, Teuteberg JJ, Birks E, Lietz K, Moore SA, Morgan JA, Arabia F, Bauman ME, Buchholz HW, Deng M, Dickstein ML, El‐Banayosy A, Elliot T, Goldstein DJ, Grady KL, Jones K, Hryniewicz K, John R, Kaan A, Kusne S, Loebe M, Massicotte MP, Moazami N, Mohacsi P, Mooney M, Nelson T, Pagani F, Perry W, Potapov EV, Eduardo Rame J, Russell SD, Sorensen EN, Sun B, Strueber M, Mangi AA, Petty MG, Rogers J. The 2013 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation guidelines for mechanical circulatory support: executive summary. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:157–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care—Institute of Medicine [Internet]. http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2002/Unequal-Treatment-Confronting-Racial-and-Ethnic-Disparities-in-Health-Care.aspx. Accessed August 21, 2012.

- 11. Cunningham CT, Quan H, Hemmelgarn B, Noseworthy T, Beck CA, Dixon E, Samuel S, Ghali WA, Sykes LL, Jetté N. Exploring physician specialist response rates to web‐based surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morton SMB, Bandara DK, Robinson EM, Carr PEA. In the 21st century, what is an acceptable response rate? Aust N Z J Public Health. 2012;36:106–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sarma AA, Nkonde‐Price C, Gulati M, Duvernoy CS, Lewis SJ, Wood MJ. Cardiovascular medicine and society: the pregnant cardiologist. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:92–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, Kerner JF, Sistrunk S, Gersh BJ, Dubé R, Taleghani CK, Burke JE, Williams S, Eisenberg JM, Escarce JJ. The effect of race and sex on physicians’ recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:618–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Granovetter M. Network sampling: some first steps. Am J Sociol. 1976;81:1287–1303. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bertrand M, Mullainathan S. Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination [Internet]. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2003. http://www.nber.org/papers/w9873. Accessed December 12, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li AC, Kannry JL, Kushniruk A, Chrimes D, McGinn TG, Edonyabo D, Mann DM. Integrating usability testing and think‐aloud protocol analysis with “near‐live” clinical simulations in evaluating clinical decision support. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81:761–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Crist JD, Koerner KM, Hepworth JT, Pasvogel A, Marshall CA, Cruz TP, Effken JA. Differences in transitional care provided to Mexican American and non‐Hispanic white older adults. J Transcult Nurs. 2017;28:159–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shafer K, Lohse B. How to conduct a cognitive interview: a nutritional education example [Internet]. http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/usda/cog_interview.pdf. Accessed April 6, 2019.

- 20. van Buuren S, Groothuis‐Oudshoorn K. mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the Lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological). 1996;58:267–288. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Friedman JH, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J Stat Softw. 2010;33:1–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Curry LA, Nembhard IM, Bradley EH. Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation. 2009;119:1442–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Strauss A, Corbin JM. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Balsa AI, McGuire TG. Prejudice, clinical uncertainty and stereotyping as sources of health disparities. J Health Econ. 2003;22:89–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kilic A, Conte JV, Shah AS, Yuh DD. Orthotopic heart transplantation in patients with metabolic risk factors. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:718–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mehra MR, Canter CE, Hannan MM, Semigran MJ, Uber PA, Baran DA, Danziger‐Isakov L, Kirklin JK, Kirk R, Kushwaha SS, Lund LH, Potena L, Ross HJ, Taylor DO, Verschuuren EAM, Zuckermann A; International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Infectious Diseases, Pediatric and Heart Failure and Transplantation Councils . The 2016 International Society for Heart Lung Transplantation listing criteria for heart transplantation: a 10‐year update. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35:1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio‐economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:813–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, Ngo LH, Raymond KL, Iezzoni LI, Banaji MR. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1231–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, Merino YM, Thomas TW, Payne BK, Eng E, Day SH, Coyne‐Beasley T. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:e60–e76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Ryn M, Burgess DJ, Dovidio JF, Phelan SM, Saha S, Malat J, Griffin JM, Fu SS, Perry S. The impact of racism on clinician cognition, behavior, and clinical decision making. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8:199–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Felker GM, Milano CA, Yager JEE, Hernandez AF, Blue L, Higginbotham MB, Lodge AJ, Russell SD. Outcomes with an alternate list strategy for heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:1781–1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Morris AA, Kransdorf EP, Coleman BL, Colvin M. Racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes after heart transplantation: a systematic review of contributing factors and future directions to close the outcomes gap. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35:953–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pamboukian SV, Costanzo MR, Meyer P, Bartlett L, Mcleod M, Heroux A. Influence of race in heart failure and cardiac transplantation: mortality differences are eliminated by specialized, comprehensive care. J Card Fail. 2003;9:80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel‐Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2008;10:348–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 37. Maldonado JR, Dubois HC, David EE, Sher Y, Lolak S, Dyal J, Witten D. The Stanford Integrated Psychosocial Assessment for Transplantation (SIPAT): a new tool for the psychosocial evaluation of pre‐transplant candidates. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stone JA, Moskowitz GB. Non‐conscious bias in medical decision making: what can be done to reduce it? Med Educ. 2011;45:768–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Normalization of Vignette Photos

Table S2. Headshot Photograph of White or African‐American Man

Table S3. Demographics of Think‐Aloud Interview Participants

Table S4. Think‐Aloud Interview Participants Survey Recommendations

Figure S1. UNOS regions.