Abstract

Tobacco smoking was examined as a risk for dementia and neuropathological burden in 531 initially cognitively normal older adults followed longitudinally at the University of Kentucky’s Alzheimer’s Disease Center. The cohort was followed for an average of 11.5 years; 111 (20.9%) participants were diagnosed with dementia, while 242 (45.6%) died without dementia. At baseline, 49 (9.2%) participants reported current smoking (median pack-years=47.3) and 231 (43.5%) former smoking (median pack-years=24.5). The hazard ratio (HR) for dementia for former smokers vs. never smokers based on the Cox model was 1.64 (95% CI: 1.09, 2.46), while the HR for current smokers vs. never smokers was 1.20 (0.50, 2.87). However, the Fine-Gray model, which accounts for the competing risk of death without dementia, yielded a subdistribution hazard ratio (sHR)=1.21 (0.81, 1.80) for former and 0.70 (0.30, 1.64) for current smokers. In contrast, current smoking increased incidence of death without dementia (sHR=2.38; 1.52, 3.72). All analyses were adjusted for baseline age, education, sex, diabetes, head injury, hypertension, overweight, APOE-ε4, family history of dementia, and use of hormone replacement therapy. Once adjusted for the competing risk of death without dementia, smoking was not associated with incident dementia. This finding was supported by neuropathology on 302 of the participants.

Keywords: competing risks, dementia, dementia free death, lifetime smoking

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco smoking has been described as a modifiable risk factor for dementia. This statement is supported by several meta-analyses of observational studies showing that the relative risk associated with smoking ranges from 1.16-1.27 for dementia and ranges from 1.45-1.79 for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1–3]. Public policy analyses based on these data estimate that nearly 14% (4.7 million) of AD cases worldwide and 11% (575,500 cases) in the US are attributable to smoking [4]. As a result, smoking cessation has become an integral part of several dementia prevention programs [5–7].

The purpose of this manuscript is to examine the risk of dementia associated with lifetime smoking in a longitudinal cohort of 531 initially cognitively intact individuals with a high prevalence of current and former smoking. This group represents the initial waves of participants recruited to the Biologically Resilient Adults in Neurological Studies (BRAiNS) cohort, previously described in detail [8]. These individuals are well characterized with annual cognitive assessments and a high autopsy rate upon death.

A standard Cox model examines smoking history as a risk for dementia after adjustment for known confounders while treating death without a dementia as a right censored event. This analysis is then compared to a similar statistical analysis that treats these dementia-free deaths as a competing event. Neuropathology findings on a large proportion of the subjects in the cohort and a pilot study on cause of death are used to inform these two approaches to the data analysis. Analyses of neuropathological data are critical when evaluating risk factors for dementia, since analysis of clinical diagnosis alone can lead to substantially biased conclusions, as has been demonstrated with analyses of diabetes and AD risk [9].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subject population

BRAiNS is a longitudinal cohort followed at the University of Kentucky Alzheimer’s Disease Center (UK ADC) [8]. Participants are at least 60 years old, community-dwelling, and relatively healthy at baseline (e.g., history of stroke is an exclusion criterion, but history of diabetes or hypertension is not). Participants are followed annually with detailed cognitive and neurological assessments, and they donate their brains for autopsy upon death. Full details on the cognitive assessments have been previously published [8]. Diagnosis of dementia was determined by DMS-IV criteria [10] and diagnosis of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) was determined by the Petersen criteria [11]. Participants in the current study were enrolled between 1989 and 2003; this window was selected to allow sufficient time to observe the endpoints of interest: death prior to dementia, and dementia. Additionally, included participants had to have at least two assessments and have APOE genotype available. The University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board approved all research procedures, and each participant provided informed consent for participation in the cohort and brain autopsy.

Smoking exposure

Participants completed a structured interview at baseline that included the questions “Do you smoke? If yes, how many cigarettes per day and for how many years? If you do not smoke now, did you ever smoke? If yes, when did you stop, how many cigarettes per day, and for how many years?” Participants were also asked about smoking pipes and cigars, with similar data collected on years smoked and average daily exposure. Participant responses were recoded into categories of smoking behavior (never, former, current), which was our primary exposure variable. Pack-years of smoking were also estimated from the responses, including data on pipes and cigars. Cigarette, pipe, and cigar smoking were converted to pack-years based on the standard conversion factors: 1 pack = 20 cigarettes, 1 pipe = 2.5 cigarettes, and 1 cigar = 4 cigarettes. Pack-year data were used in sensitivity analyses. Since smoking information was not updated regularly between 1989 and 2005, it was not possible to obtain end-of-follow-up smoking data for many participants. Thus, smoking exposure was fixed at baseline.

Covariates

Potential confounders for the association between smoking and dementia, as well as smoking and death, were included in the analyses. Covariates were fixed at baseline and included age in years and dummy indicators for APOE-ε4 carrier status (any 4 vs. no 4 allele), female sex, low education (i.e., less than a high school education), Type 2 diabetes, head injury, hypertension, overweight (body mass index > 25), family history of dementia (defined as a first degree relative), and use of hormone replacement therapy. Medical history information was self-reported by the participant during the structured baseline interview.

Neuropathology measures

Neuropathological evaluations were performed blind to clinical data (i.e., cognitive status and exposure status) as described previously [12]. Alzheimer’s disease neuropathologic changes (ADNC), diffuse (neocortical) Lewy body disease, hippocampal sclerosis of aging (HS-Aging) pathologies were as described using criteria as defined in consensus papers [13–16]. Additional cerebrovascular pathology measures included indicators for brain infarction, as well as ordinal ratings of atherosclerosis, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, and arteriolosclerosis [17]. Since we did not have Thal amyloid phases for all cases, a modified ADNC rating was derived as described previously [9]. For analysis, ordinal neuropathology variables were dichotomized as follows: ADNC as Intermediate/High AD vs. No/Low AD; Braak stage as V/VI vs. 0-IV; atherosclerosis as all vessels < 50% occluded vs. all vessels > 50%; diffuse plaques, neuritic plaques, arteriolosclerosis, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy as Moderate/Severe vs. None/Mild.

Cause of death

Primary cause of death was recorded by the neuropathologist when provided by the attending medical personnel or next of kin. These text descriptions were then classified into the following 13 mutually exclusive categories: accidental, cancer, dementia, embolism, failure to thrive, heart disease, infection, liver failure, pneumonia, chronic respiratory, renal disease, stroke, and other. Geriatric “failure to thrive” is a term adapted from the pediatric literature and refers to significant weight loss at the end of life due to cessation of eating and drinking. Authors RJK and ELA manually coded the causes of death, and both were blinded to cognitive status and all other data collected on the deceased.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed using means, standard deviations or medians and inter-quartile range (IQR). Proportions were compared using chi-square statistics. Survival time was defined as the length of time from baseline until the first event of interest, either a dementia diagnosis or death without a dementia diagnosis. The age at the first diagnosis of dementia was taken to be the average of the age at which the first diagnosis of dementia occurred and the age at the prior visit, to reflect our uncertainty about the true onset age. Otherwise, survival time was calculated as time from baseline to last follow-up. We did not exclude dementia diagnoses that occurred early during follow-up from the analysis because of the clear temporal sequencing between initiation of smoking exposure and onset of dementia. In other words, reverse causality, where preclinical or prodromal neuropathological disease “causes” the exposure (e.g., depression, anxiety, or insomnia) is unlikely to play a role here. Effect measure modification by age and sex were evaluated using cross-product interaction terms, while effect measure modification by APOE-ε4 and education status were evaluated using stratification due to low numbers of participants with APOE-ε4 and low education within some smoking groups. Since just 5/531 participants reported non-White race, race was not further considered in the analysis.

The Cox model treats all right censored nonevents as uninformative. Thus, the Cox model handles participants still at risk for dementia at their last follow-up (i.e., administrative censoring) and those who died before dementia (i.e., informative censoring) the same way. Since death prior to dementia fundamentally alters the probability of observing dementia, this event should not be treated as uninformative. Thus, we refit the model to adjust the hazard of dementia for the competing risk of death without dementia using the subdistribution hazard model developed by Fine and Gray [18]. As a sensitivity analysis, we redefined the cognitive event to include first diagnosis of either MCI or dementia and refit the models. Age at diagnosis of MCI was calculated as described above for age at diagnosis of dementia; here, the competing risk of death was defined as occurring prior to both MCI and dementia. All computations were performed using PROC PHREG in SAS 9.4® [19]. Cumulative incidence curves with 95% confidence limits were generated using the ‘baseline’ statement in this procedure.

Analyses of neuropathological features were performed using logistic regression, where the log-odds of the more severe pathology were estimated. Smoking exposure was treated as binary (ever vs. never), and these analyses were adjusted for age at death, sex, and APOE-ε4. As a sensitivity analysis, we further adjusted these models for hypertension and diabetes. As additional sensitivity analyses, we replaced the smoking indicator variable with baseline pack-years of exposure and re-fit the models. As above, potential effect measure modification by age and sex was assessed via cross-product interaction terms. Since longitudinal medical history was unavailable for approximately 1/3 of the autopsied participants, hypertension and diabetes were fixed at baseline.

For the cause of death analysis, we ranked the causes by frequency and examined associations with smoking, dementia, and neuropathology using proportions and unadjusted odds ratios. Adjustment was not performed for cause of death analyses, which we considered exploratory due to the large portion of missing data and likely biases in reporting.

RESULTS

Mean age at enrollment was 73.2±7.4 years; participants were majority female (63.1%) and highly educated (mean 16.0±2.4 years) (Table 1). A large percentage (40.3%) declared a positive family history of dementia and other risk factors for dementia including diabetes (8.3%), hypertension (53.1%), and head injury (15.4%). At least one APOE-ε4 allele was present in 30.3% of participants.

Table 1:

Characteristics of the BRAiNS cohort (enrolled 1989–2003) by baseline smoking status

| Characteristic* | All Participants (N=531) | Never Smokers (N=251) | Former Smokers (N=231) | Current Smokers (N=49) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline age, years | 73.2±7.4 | 72.9±9.2 | 74.1±7.5 | 71.1±7.1 |

| Education, years | 16.0±2.4 | 16.1±2.3 | 16.0±2.5 | 15.3±2.2 |

| Low education (< 12 years) | 62 (11.7) | 29 (11.6) | 25 (10.8) | 8 (16.3) |

| Female sex | 335 (63.1) | 183 (72.9) | 122 (52.8) | 30 (61.2) |

| APOE-ε4 carrier | 161 (30.3) | 79 (31.5) | 70 (30.3) | 12 (24.5) |

| Family history of dementia | 214 (40.3) | 116 (46.2) | 81 (35.1) | 17 (34.7) |

| Type 2 diabetes | 44 (8.3) | 23 (9.2) | 19 (8.2) | 2 (4.1) |

| Body Mass Index > 25 | 227 (42.8) | 110 (43.8) | 97 (42.0) | 20 (40.8) |

| Hypertension | 282 (53.1) | 135 (53.8) | 119 (51.5) | 28 (57.1) |

| Head Injury | 82 (15.4) | 34 (13.5) | 41 (17.7) | 7 (14.3) |

| Hormone replacement therapy (% all subjects) | 99 (18.6) | 57 (22.7) | 32 (13.9) | 10 (20.4) |

| Smoking pack-years | 2 (0-30) | 0 | 24.5 (10-42) | 47.3 (25.6-62.5) |

| Incident dementia diagnosis | 111 (20.9) | 54 (21.5) | 51 (22.1) | 6 (12.2) |

| Death without dementia | 242 (45.6) | 103 (41.0) | 111 (48.1) | 28 (57.1) |

All results presented are mean±SD or n (%), with the exception of pack-years, which are median (IQR).

Smoking exposure was common: 49 (9.2%) participants reported current smoking at baseline (median pack-years=47.3), while 231 participants reported former smoking (median pack-years=24.5) (Table 1). Former smokers were significantly older than current smokers, and were significantly less likely to be female; never smokers were significantly more likely to report a family history of dementia. Smoking groups were statistically comparable on the remaining characteristics in Table 1.

Median survival time was lengthy at 11.4 years (IQR 7.4-14.0). For the subset of 178 participants who did not experience either incident dementia or death, median survival time was even longer at 14.3 years (IQR 10.7-16.7). Mean age at the end of follow-up was 84.7 ± 7.3 years; mean age for the subset of 111 participants who transitioned to clinical dementia was 85.5 ± 7.0 years, and for the subset of participants who died without dementia it was 86.3 ± 7.5 years. MCI was diagnosed in 55/178 (30.9%) participants who did not die before dementia or develop dementia. Of these, 12/55 (21.8%) died with a diagnosis of MCI.

Survival analysis

The Cox model indicated smoking was a risk for incident dementia with adjusted HR=1.64 for former smokers vs. never smokers (95% CI: 1.09, 2.46); for current smokers, adjusted HR=1.20 (0.50, 2.87). Having at least 10 pack-years of smoking history (n=215) vs never smoking (n=251) was also associated with dementia, with an adjusted HR=1.65 (1.08, 2.53). Less than 10 pack-years (n=65) vs. never smoking yielded an adjusted HR=1.39 (0.76, 2.58). The cut-point 10 pack-years was chosen since it was the lower quartile of exposure in the former smoker category. There was no effect measure modification by age or sex for any of these analyses.

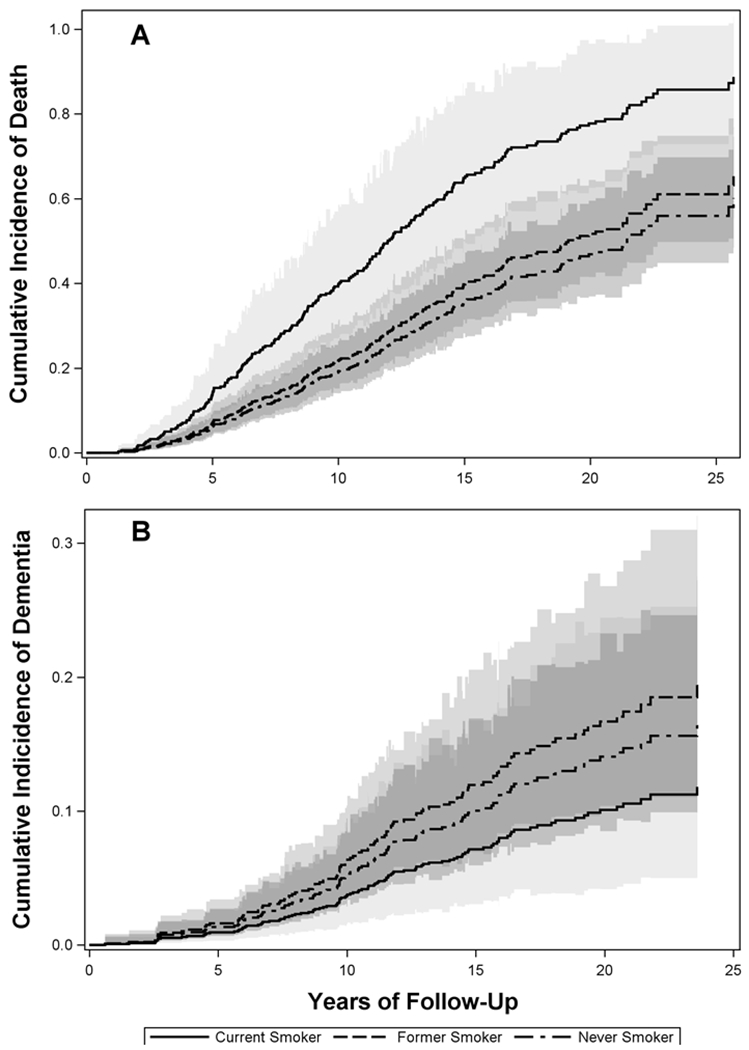

However, once adjusted for the competing risk of death without dementia, current smoking was no longer a significant risk for dementia. The adjusted subdistribution hazard ratio (sHR) was 1.21 (95% CI: 0.81, 1.80) for former and 0.70 (0.30, 1.64) for current smokers. The adjusted sHR for at least 10 pack-years of exposure was 1.14 (0.76, 1.71). In contrast, baseline current smoking increased the incidence of death without dementia (sHR = 2.38; 1.52, 3.72). These results are illustrated in the cumulative incidence curves of Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Cumulative incidence curves by baseline smoking status for the competing events death without dementia (Panel A) and dementia (Panel B). The predicted curves are based on hypothetical female participants who are 73 years old at baseline, with high education, no APOE-ε4, no family history of dementia, hypertension, no diabetes, no HRT use, normal weight, and no head injury.

While there was no observed effect measure modification by age, the association between smoking status and death without dementia was modified by sex. For former smokers vs. never smokers, the sHRfor men was 1.34 (0.83, 2.01) and 0.97 (0.65, 1.44) for women. For men, current vs. never smoking yielded sHR=1.16 (0.52, 2.58), while for women the sHR=4.13 (2.56, 6.67). For participants with high education, the sHR for death for current vs. never smoking was 2.00 (1.20, 3.34) and was 1.21 (1.08, 1.99) for former vs. never smoking. For participants with low education, the sHR for death for current vs. never smoking was 4.40 (1.36, 14.23) and 0.80 (0.32, 1.88) for former vs. never smoking. For participants with high education, sHR for dementia for current vs. never smoking was 0.84 (0.36, 1.99) and was 1.13 (0.74, 1.72) for former vs. never smoking. Due to low numbers, hazard ratios for dementia were not estimable in the low education stratum. For participants with at least one APOE-ε4 allele, the sHR for death for current vs. never smoking was 0.92 (0.28, 2.97) and 1.65 (0.96, 2.85) for former vs. never smoking. For participants no ε4 allele, the sHR for death was 3.61 (2.38, 5.49) for current vs. never and 1.03 (0.74, 1.44) for former vs. never smoking. For dementia, the sHR for current vs. never smoking was 1.40 (0.45, 4.31) and 0.99 (0.51, 1.92) for former vs. never smoking for ε4 allele carriers, and 0.36 (0.08, 1.55) for current vs. never and 1.37 (0.82, 2.30) for former vs. never smokers. Overall, we note that none of the effect measure modification analyses revealed significant associations between either current or former smoking and incident dementia within strata of the potential modifiers. However, some factors significantly increased the incidence of death before dementia for baseline current smokers: female sex, no APOE-ε4 allele, and low educational attainment.

When first diagnosis of either MCI or dementia was used as the cognitive event, death was considered a competing event only if it occurred prior to the first diagnosis of any cognitive impairment. This yielded 178/531 (33.5%) participants with an incident diagnosis of cognitive impairment, and 230/531 (43.3%) who died before cognitive impairment. In this analysis, the adjusted HR derived from the Cox model for former smokers vs. never smokers was 1.33 (95% CI: 0.96, 1.83) and 0.80 (0.39, 1.61) for current smokers vs. never smokers. In the competing risk analysis, the subdistribution HR for former smokers vs. never smokers was 0.97 (0.70, 1.34) and 0.51 (0.26, 0.99) for current smokers vs. never smokers. As in the dementia-only analysis, the Fine-Gray results showed that the apparent protective effect of smoking among current smokers is explained by an increased incidence of mortality vs. never smokers (sHR=2.52; 1.63, 3.89). The incidence of mortality was not significantly increased among former smokers vs. never smokers (sHR=1.16; 0.87, 1.56).

Autopsy data

Of the 531 participants in the study, 350 died and 302 came to autopsy (86.3%). Average age at death was 88.6±7.1 years among autopsied never smokers and 86.2±7.5 years among ever smokers. Neuropathological features were cross-tabulated against smoking history (Table 3). Compared to never smokers, ever smokers were less likely to have higher levels of any of the neuropathological features studied, with the exception of lacunar infarcts. Adjustment for age at death, sex, and APOE-ε4 did not alter the direction of these associations, and the severity of atherosclerosis, presence of pale infarcts, and presence of macro-infarcts were significantly lower among smokers (Table 3). Further adjustment for diabetes and hypertension did not appreciably change the results. There was no evidence of effect measure modification by age or sex for any of the analyses. Analyses based on pack-year data were consistent with the dichotomized smoking variable in both direction of the association and lack of statistical significance.

Table 3:

Adjusted odds ratios* between smoking status (ever vs. never) and neuropathological features among autopsied BRAiNS participants (N=302). Smoking history was associated with generally lower burden of both degenerative and cerebrovascular pathologies.

| Neuropathological feature | Never Smoker (N=141) | Ever Smoker (N=161) | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADNC rating: Intermediate/High AD | 46.5 | 33.3 | 0.63 (0.38, 1.03) |

| Neuritic Plaques: Moderate/Severe | 57.6 | 48.2 | 0.74 (0.45, 1.20) |

| Diffuse Plaques: Moderate/Severe | 70.8 | 63.6 | 0.76 (0.45, 1.28) |

| Braak neurofibrillary tangle stage: V/VI | 28.7 | 16.8 | 0.59 (0.33, 1.07) |

| Diffuse Lewy body disease | 9.0 | 6.2 | 0.66 (0.27, 1.63) |

| Hippocampal Sclerosis of Aging | 16.8 | 11.1 | 0.86 (0.42, 1.77) |

| Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: Moderate/Severe | 21.1 | 20.4 | 1.08 (0.59, 1.98) |

| Arteriolosclerosis: Moderate/Severe | 27.6 | 15.9 | 0.60 (0.31, 1.13) |

| Atherosclerosis: All vessels > 50% occluded | 62.0 | 44.0 | 0.55 (0.33, 0.91) |

| Hemorrhages present | 8.3 | 7.4 | 0.84 (0.35, 2.04) |

| Infarctions: | |||

| Micro-infarct present | 40.3 | 40.7 | 0.96 (0.59, 1.55) |

| Lacunar infarct present | 14.6 | 17.9 | 1.28 (0.67, 2.44) |

| Pale infarct present | 27.1 | 14.8 | 0.49 (0.27, 0.90) |

| Macro-infarct present | 27.1 | 13.6 | 0.41 (0.22, 0.75) |

Odds ratios were adjusted for age at death, sex, and APOE carrier status. Braak score missing for 1 smoker and 1 non-smoker. Amyloid angiopathy missing for 2 non-smokers. Hippocampal Sclerosis missing for 4 non-smokers. Arteriolosclerosis missing for 24 smokers and 21 non-smokers. Atherosclerosis missing for 3 smokers and 2 nonsmokers.

Cause of death

The cause of death was reported for 193/302 (63.9%) autopsied cases. Cause of death was reported for 111/161 (68.9%) smokers and 82/141 (58.2%) never smokers. The top four causes of death were heart disease (n=47), cancer (n=48), pneumonia (n=23), and stroke (n=21), representing 72.0% of the reported causes of death. Reported deaths in all four categories tended to occur in non-demented participants, with 6/47 (12.8%) heart disease, 7/48 (14.6%) cancer, 8/23 (34.8%) pneumonia, and 8/21 (38.1%) stroke deaths in each group diagnosed with dementia prior to death. For cases with unreported cause of death, 40/109 (36.7%) were diagnosed with dementia prior to death. Smoking history, however, was much more common among these deaths: 29/47 (61.7%) heart disease, 32/48 (66.7%) cancer, 16/23 (69.6%) pneumonia, and 8/21 (38.1%) stroke deaths were ever smokers. We note that the percent of ever smokers among all cases with known cause of death is 57.5% (111/193). For cases with unreported cause of death, 50/109 (45.9%) were ever smokers. Among cases with reported cause of death, 85/111 (76.6%) with a smoking history died of the top four causes, compared to 54/82 (65.9%) with no smoking history: OR = 1.70 (95% CI: 0.90, 3.19).

DISCUSSION

Here we provide evidence that the reported association between smoking and risk of dementia may be due to analytical methods that do not consider the competing risk of death without dementia. The Cox proportional hazards model, which is widely used in epidemiological research, treats competing events as uninformative censoring. However, when we treated these deaths as a competing risk in the analysis, smoking was no longer associated with dementia. The data used to illustrate this point were drawn from the UK ADC BRAiNS cohort, which provided a large sample of initially cognitively normal older adults (age 60+) followed for many years, with ample exposure to tobacco smoking (52.7% of participants had a smoking history). Most importantly, we had sufficient numbers of events (111 incident dementia diagnoses vs. 242 deaths without dementia) to make the case that smoking was a risk for earlier death but not for dementia. Large autopsy numbers (n=302) were used to support this finding since pathology shows that a smoking history was associated with a lower probability of AD or other neuropathology at death. These results were further supported by our analysis of causes of death, which showed that smokers tended to die of causes of death that were not associated with dementia. The top two reported causes of death (heart disease and cancer) were dominated by smokers (64.2% of deaths due to these causes were among smokers). Where cause of death was reported, consistent with the smoking literature [20], heart disease and cancer accounted for 56.0% of deaths among those who died without dementia but only 27.7% of those who died with dementia.

The conclusion that smoking did not increase the incidence of dementia, or cognitive impairment more generally, conflicts with the results of prior studies [1–3]. However, these analyses all relied on the standard Cox model to determine the association between smoking and dementia. Statistically, these studies are examining the marginal distribution of survival (i.e., time to dementia). In the case where there is heavy competition from another event, this can be misleading. An alternative is to examine the subdistribution of survival time to dementia, which adjusts for the presence of competing risks. This relies on estimating the cumulative incidence function, which accounts for competing risks. Adjustment for other covariates is made using a proportional hazards version of the cumulative incidence function due to Fine and Gray [19]. This approach is well known and has been adopted in other fields of medicine including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and gerontology [21–23]. Surprisingly, it is not the standard approach in the field of dementia research, where the competing risk of death is ever present.

Another alternative approach to adjusting for competing risks is to adopt a multistate model in which participants flow through different health states such as the pre-dementia states of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and competing risk states such as participant withdrawal and death without a dementia. This approach has been successfully used to study self-reported head injury and MCI [24–25]. The Markov chain approach works well if the cognitive assessments are equally spaced but can introduce some bias if not [(26]. Although the model becomes more complex, the unequally spaced intervals can be handled using a semi-Markov process, which also adjusts for competing risks [27].

For neurodegenerative diseases, it is critical to validate clinical findings with neuropathological findings due to the imperfect correlation between clinical diagnoses of dementia and neuropathology [9,28]. Our findings do not support a link between smoking and AD pathology. This is consistent with several prior neuropathological studies of smoking and AD pathology [29] but not all [30].

Somewhat surprisingly, smoking was generally not associated with increased cerebrovascular pathology, other than lacunar infarcts. However, the association with lacunes was not statistically significant. In addition, other neuropathologies also appeared to be less prevalent among those with a positive smoking history. This could be due in part to the smokers dying an average of two years sooner than never smokers. Other explanations may include chemotherapy treatments received by smokers who developed cancer [31] or a healthy survivor effect. The cohort studied here, which is community rather than population-based, comprises highly educated participants who had already survived to at least age 60 in good health, and in many cases survived into their late 80s and beyond. This may mean that our participants were better able to resist deleterious effects of smoking on the brain than other populations given similar levels of exposure.

Despite its many strengths this study has some limitations. Smoking was by self-report and fixed at study entry. Therefore, we do not know the full extent of exposure to tobacco smoke among those actively smoking at enrollment, or former smokers who may have reinitiated smoking. However, even at baseline the current smokers had much higher median pack-years of exposure, and it is unlikely that these additional data would have changed our results. We also did not have data on secondhand smoke exposure, or data on diet and physical activity. While the autopsy rate was high (86.3%), the missing autopsies may introduce bias. The recording of cause of death may also be vulnerable to selection and information bias. This may limit the generalizability of the results, so further studies on the implications of ignoring the competing risk of death before dementia on risk factor identification are needed using population-based data.

In conclusion, this study shows that when adjusted for the competing risk of death without dementia, smoking was not associated with increased risk of dementia or AD pathology in a cohort with high prevalence of lifetime smoking. This may have implications for the current focus on smoking cessation as a modifiable risk for dementia. We emphasize that this is not to say that efforts invested in smoking cessation are misguided or unimportant, since smoking clearly increases the risk of multiple other chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease and cancer, as well as earlier mortality. However, smoking cessation efforts focused on preventing dementia may not provide the expected benefit at the population level [4].

Table 2:

Adjusted hazard ratios and subdistribution hazard ratios* for dementia and death without dementia for current and former smokers vs. never smokers. Accounting for the competing risk of death in the Fine-Gray model mitigates the association between former smoking and dementia observed in the standard Cox model, and reveals a strong association between current smoking and incidence of mortality. Inclusion of milder forms of cognitive impairment further supports these results.

| Cox Model | Fine-Gray Models | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia | Dementia | Death w/o Dementia | ||||

| Current smoker | 1.20 | 0.50, 2.87 | 0.70 | 0.30, 1.64 | 2.38 | 1.52, 3.72 |

| Former smoker | 1.64 | 1.09, 2.46 | 1.21 | 0.81, 1.80 | 1.15 | 0.87, 1.53 |

| MCI/Dementia | MCI/Dementia | Death w/o MCI/Dementia | ||||

| Current smoker | 0.80 | 0.39, 1.61 | 0.51 | 0.26, 0.99 | 2.52 | 1.63, 3.89 |

| Former smoker | 1.33 | 0.96, 1.83 | 0.97 | 0.70, 1.34 | 1.16 | 0.87, 1.56 |

All hazard ratios are adjusted for baseline age, education, sex, APOE, hypertension, diabetes, head injury, hormone replacement therapy use, overweight, and family history of dementia.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was partially funded with support from the following grants to the University of Kentucky’s Sanders-Brown Center on Aging: R01 AG038651 and P30 AG028383 from the National Institute on Aging, R01 NS014189 from the National Institute of Nursing Research, as well as a grant to the University of Kentucky’s Center for Clinical and Translational Science, UL1TR000117, from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- [1].Anstey KJ, von Sanden C, Salim A, O’Kearney R (2007) Smoking as a risk factor for dementia and cognitive decline: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Epidemiol 166, 367–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Cataldo JK, Prochaska JJ, Glantz SA (2010) Cigarette smoking is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s Disease: an analysis controlling for tobacco industry affiliation. J Alzheimers Dis 19, 465–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Peters R, Poulter R, Warner J, Beckett N, Burch L, Bulpitt C (2008) Smoking, dementia and cognitive decline in the elderly, a systematic review. BMC Geriatr 8,36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Barnes DE, Yaffe K (2011) The projected impact of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s Disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol 10, 819–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Bryne C (2014) Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol 13, 788–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Winblad B, Amouyel P, Andrieu S, Ballard C, Brayne C, Brodaty H, Cedazo-Minguez A, Dubois B, Edvardsson D, Feldman H, Fratiglioni L, Frisoni GB, Gauthier S, Georges J, Graff C, Iqbal K, Jessen F, Johansson G, Jönsson L, Kivipelto M, Knapp M, Mangialasche F, Melis R, Nordberg A, Rikkert MO, Qiu C, Sakmar TP, Scheltens P, Schneider LS, Sperling R, Tjernberg LO, Waldemar G, Wimo A, Zetterberg H (2016) Defeating Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: a priority for European science and society. Lancet Neurol 15, 455–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Qui C, Fratiglioni L (2018) Aging without dementia is achievable: current evidence from epidemiological research. J Alzheimers Dis 62, 933–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Schmitt FA, Nelson PT, Abner E, Scheff S, Jicha GA, Smith C, Cooper G, Mendiondo M, Danner DD, Van Eldik LJ, Kryscio RJ (2012) University of Kentucky Sanders-Brown Healthy Brain Aging Volunteers: Donor characteristics, Procedures And Neuropathology. Curr Alzheimer Res 9, 724–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Abner EL, Nelson PT, Kryscio RJ, Schmitt FA, Fardo DW, Woltjer RL, Cairns NJ, Yu L, Dodge HH, Xiong C, Masaki K, Tyas SL, Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z (2016) Diabetes is associated with cerebrovascular but not Alzheimer neuropathology. Alzheimer Dement 12, 882–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Ed Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Petersen RC, Aisen P, Boeve BF, Geda YE, Ivnij RJ, Knopman DS, Mielke M, Pankratz VS, Roberts R, Rocca WA, Weigand S, Wiener M, Wiste H, Jack CR Jr. (2013) Criteria for mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease in the mmunity. Ann Neurol 74,199–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nelson PT, Jicha GA, Schmitt FA Liu H, Davis DG, Mendiondo MS, Abner EL, Markesbery WR (2007) Clinicopathologic correlation in a large Alzheimer disease center autopsy cohort neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles “do count” when staging disease severity. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 66, 1136–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Carrillo MC, Dickson DW, Duyckaerts C, French MP, Masliah E, Mira SS, Schneider JA, Thal DR, Thies B, Trojanowski JQ, Vinters HV, Montine TJ (2012). National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’sAssociation guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer Dement 8, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, Duyckaerts C, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Mira SS, Nelson PT, Schneider JA, Thal DR, Trojanowski JQ, Vinters HV, Hyman BT, National Institute on Aging, Alzheimer’s Association (2012). National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the Neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol 123, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nelson PT, Smith CD, Abner EL, Wilfred BJ, Wang WX, Neltner JH, Baker M, Fardo DW, Kryscio RJ, Scheff SW, Jicha GA, Jellinger KA, Van Eldik LJ, Schmitt FA (2013) Hippocampal sclerosis of aging, a prevalent and high-morbidity brain disease. Acta Neuropathol 126, 161–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nelson PT, Schmitt FA, Lin Y, Abner EL, Jicha GA, Patel E, Thomason PC, Neltner JH, Smith CD, Santacruz KS, Sonnen JA, Poon LW, Gearing M, Green RC, Woodard JL, Van Eldik LJ, Kryscio RJ (2011) Hippocampal sclerosis in advanced age: clinical and pathological features. Brain 134,1506–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Neltner JH, Abner EL, Baker S, Schmitt FA, Kryscio RJ, Jicha GA, Smith CD, Hammack E, Kukull WA, Brenowitz WD, Van Eldik LJ, Nelson PT (2014) Arteriolosclerosis that affects multiple brain regions is linked to hippocampal sclerosis of ageing. Brain 137, 255–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Fine JP, Gray RJ (1999) A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 94, 496–509. [Google Scholar]

- [19].PC-SAS 9.4. (2016) SAS Institute Inc; Cary N.C. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Thun MJ, Carter BD, Feskanich D, Freednab ND, Prentice R, Lopez AD, Hartge P, Gapstur SM (2013) 50 year trends in smoking-related mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med 368, 351–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chappell R (2012) Competing risk analysis: how they are different and why should you care? Clin Cancer Res 18, 2127–2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Berry SD, Ngo L, Samelson EJ, Kiel DP (2010) Competing risk of death: an important consideration in studies of elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 58, 783–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wolbers M, Koller MT, Witteman C, Steyerberg EW (2000) Prognostic models with competing risks: methods and application to coronary risk prediction Epidemiology 20, 555–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Abner EL, Nelson PT, Schmitt FA, Browning SR, Fardo DW, Wan L, Jicha GA, Cooper GE, Smith CD, Caban-Holt AM, van Eldik LJ, Kryscio RJ (2014) Self-reported head injury and risk of late-life impariment and AD pathology in an AD center cohort. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 37, 294–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tyas SL, Salazar JC, Snowdon DA, Desrosiers MF, Riley KP, Mendiondo MS, Kryscio RJ (2007) Transitions to mild cognitive impairments, demenita, and death: findings from the Nun Study. Am J Epidemiol 165, 231–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wan L, Lou W, Abner E, Kryscio RJ (2016) A comparison of time-homogenous Markov chain and Markov process multi-state models. Commun Stat Case Stud Data Anal Appl 2, 92–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kryscio RJ, Abner EL, Lin Y, Cooper GE, Fardo DW, Jicha GA, Nelson PT, Smith CD, Van Eldik LJ, Wan L, Schmitt FA (2013). Adjusting for mortality when identifying risk factors for transitions to mild cognitive impairment and dementia. J Alzheimer Dis 35, 823–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Beach T, Monsell S, Phillips L, Kukull W (2012). Accuracy of the Clinical Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease at National Institute on Aging Alzheimer’s Disease Centers, 2005-2010. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 71, 266–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chang RCC, Ho YS, Wong S (2014) Neuropathology of cigarette smoking. Acta Neuropathol 127, 53–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tyas SL, White LR, Petrovitch H, Webster Ross G, Foley DJ, Heimovitz HK, Launer LJ (2003) Mid-life smoking and late-life dementia: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Neurobiol Aging 24, 589–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Frain L, Swanson D, Cho K, Gagnon D, Lu KP, Betensky RA, Driver J (2017). Association of cancer and Alzheimer’s disease risk in a national cohort of veterans. Alzheimer Dement 13, 1364–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]