Summary

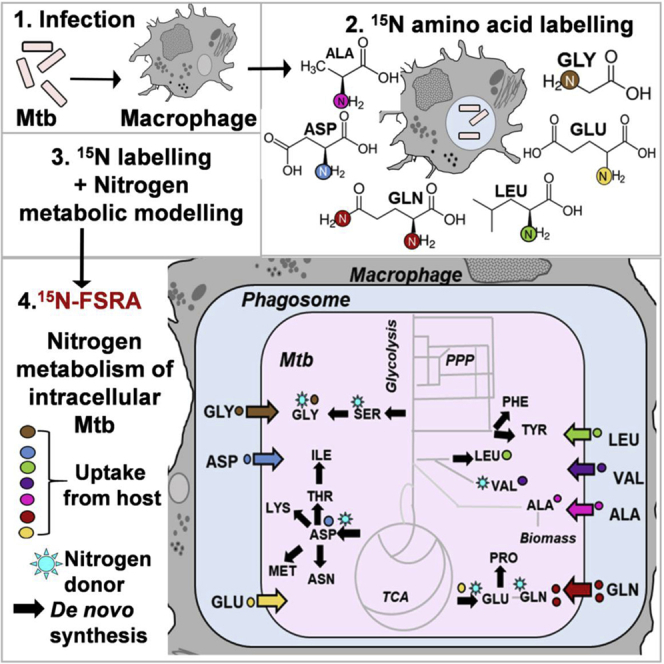

Nitrogen metabolism of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is crucial for the survival of this important pathogen in its primary human host cell, the macrophage, but little is known about the source(s) and their assimilation within this intracellular niche. Here, we have developed 15N-flux spectral ratio analysis (15N-FSRA) to explore Mtb’s nitrogen metabolism; we demonstrate that intracellular Mtb has access to multiple amino acids in the macrophage, including glutamate, glutamine, aspartate, alanine, glycine, and valine; and we identify glutamine as the predominant nitrogen donor. Each nitrogen source is uniquely assimilated into specific amino acid pools, indicating compartmentalized metabolism during intracellular growth. We have discovered that serine is not available to intracellular Mtb, and we show that a serine auxotroph is attenuated in macrophages. This work provides a systems-based tool for exploring the nitrogen metabolism of intracellular pathogens and highlights the enzyme phosphoserine transaminase as an attractive target for the development of novel anti-tuberculosis therapies.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, tuberculosis, host macrophages, intracellular pathogen, nitrogen metabolism, systems biology, isotopic labeling, flux analysis, host metabolism, amino acid

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Mycobacterium tuberculosis utilizes multiple amino acids as nitrogen sources in human macrophages

-

•

15N-FSRA tool identified the intracellular nitrogen sources

-

•

Glutamine is the predominant nitrogen donor for M. tuberculosis

-

•

Serine biosynthesis is essential for the survival of intracellular M. tuberculosis

Borah et al. measured nitrogen uptake and assimilation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis during replication in host macrophages using 15N-flux spectral ratio analysis (15N-FSRA), a systems-based tool. The biosynthetic and transport systems of the identified nitrogen sources involved in serine biosynthesis are potential drug targets.

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the top 10 causes of morbidity and mortality in the human population, responsible for 1.6 million deaths and 10 million new infections every year (WHO, 2018, Flynn, 2006, Zumla et al., 2013). The causative agent of TB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), primarily resides within the hostile environment provided by the phagosome of macrophages and can therefore resist stress conditions such as low pH, hypoxia, reactive oxygen species, reactive nitrogen species, and nutrient starvation (Gouzy et al., 2014a, Russell, 2001, Rustad et al., 2009). Metabolism within this restricted niche is key to the survival and pathogenesis of Mtb (Beste et al., 2011, Ehrt and Rhee, 2013, Eoh et al., 2017, Warner, 2014). Understanding Mtb’s metabolism within the macrophage has therefore become an important focus for research, with the aim of identifying vulnerable metabolic pathways that could be targeted with drugs. Carbon metabolism in Mtb has been intensively investigated, and host-derived lipids, cholesterol, and CO2 have been identified as essential nutrients for intracellular growth and survival of TB in animal models (Beste et al., 2011, Beste et al., 2013, Ehrt et al., 2018, Eisenreich et al., 2010, Gouzy et al., 2014b, McKinney et al., 2000, Niederweis, 2008, Schnappinger et al., 2003). Our 13C-flux spectral analysis (13C-FSA) approach, applied to the intracellular carbon metabolism of Mtb, also demonstrated that several nonessential amino acids are acquired by Mtb from macrophages, highlighting their availability as potential nitrogen sources within the human host. However, the identity of the primary nitrogen sources for intracellular Mtb remains uncertain. Amino acid acquisition and metabolism is important for the pathogenesis of several intracellular bacterial pathogens, including Mtb (Das et al., 2010, Eylert et al., 2008, Gouzy et al., 2013, Gouzy et al., 2014c, Kloosterman and Kuipers, 2011). For example, Salmonella enterica, Serovar typhimurium, and Streptococcus pneumoniae require arginine for intracellular survival and virulence (Das et al., 2010, Kloosterman and Kuipers, 2011), demonstrating that this amino acid is a nitrogen source. Listeria monocytogenes has been shown to acquire aspartate, alanine, and glutamate from the host macrophages for de novo amino acid synthesis (Eylert et al., 2008). Isotopologue profiling studies also identified the amino acid serine as a carbon and energy source for the growth and replication of Legionella pneumophilia (Eylert et al., 2010).

In vitro, Mtb can utilize a wide range of carbon sources but was only able to utilize 13 out of 95 tested compounds as nitrogen sources (Lofthouse et al., 2013). These included mainly the following amino acids: alanine, asparagine, aspartate, valine, glutamate, glutamine, ornithine, and serine. Agapova et al. (2019) recently extended this list to include arginine, isoleucine, and proline, and urea has previously been shown to be utilized as a nitrogen source in vitro (Lin et al., 2012). The work by Agapova et al. (2019) also demonstrated that growth rates and yields are higher when Mtb grows with amino acids, as compared with ammonium as nitrogen sources, and that like carbon sources, Mtb can co-metabolize two amino acids simultaneously in vitro. However, a comprehensive study to identify the nitrogen sources for intracellular Mtb growing within the host macrophage has never been performed.

The Mtb genome encodes several transporters for both inorganic and organic nitrogen compounds (e.g., ammonium chloride [Amt] and nitrate [NarK2]), as well as ATP-binding cassette (ABC) amino acid transporters (Cole et al., 1998). Aspartate and asparagine have been detected in the Mtb phagosome, highlighting these amino acids as potential intracellular nitrogen sources. However, while the gene directing the transport of aspartate (AnsP1) was essential for the synthesis of nitrogen-containing compounds in a murine model of TB, this gene was dispensable for intracellular survival, suggesting that aspartate is not the primary nitrogen donor for Mtb growing within macrophages. Conversely, a study by the same group demonstrated that the asparagine transporter (AnsP2) was required for surviving intra-phagosomal acid stress but was dispensable for in vivo survival (Gouzy et al., 2013, Gouzy et al., 2014a). Glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH), the enzyme that catalyzes the production of glutamate from 2-oxoglutarate, is also essential for the intracellular survival of Mtb (Cowley et al., 2004, Gallant et al., 2016, Viljoen et al., 2013). However, GDH is also required for resistance to acidic and nitrosative stress in Mycobacterium bovis (BCG); therefore, the role of glutamate as a nitrogen source is uncertain. Mtb auxotrophic mutants of leucine, proline, tryptophan, and glutamine have previously been shown to be severely attenuated in vivo (Hondalus et al., 2000, Lee et al., 2006, Smith et al., 2001), indicating that biosynthesis of these amino acids is required by Mtb growing in the intracellular environment. Several other auxotrophic mutants (e.g., methionine, isoleucine, or valine) can, however, successfully proliferate in macrophages, indicating that these amino acids can be acquired from the macrophage milieu (Awasthy et al., 2009, McAdam et al., 1995). Mutagenesis studies are useful in identifying Mtb genes required for nitrogen uptake or metabolism during intracellular or in vivo survival; however, none of these studies have directly measured the uptake and assimilation of nitrogen by intracellular Mtb.

Isotopic tracer studies, combined with direct interpretation of the labeling patterns in metabolites, have emerged as a powerful strategy to study the intracellular metabolism of important pathogens (Buescher et al., 2015, Eylert et al., 2010). We previously used 13C isotopomer analysis and developed 13C-FSA to identify the intracellular carbon sources for Mtb (Beste et al., 2013). However, this approach was unsuitable for the current study because of the lack of backbone rearrangements in the metabolic network, as compared to carbon, and limited mass isotopomer information from single nitrogen atoms. To overcome these limitations, here we developed 15N-FSRA, a computational platform for analysis of the uptake of all potential amino acids as nitrogen sources. Specifically, to counteract the limited measurement information, an array of 15N labeling experiments was conducted under equal conditions, which was simultaneously evaluated in an integrative system-based approach. This work showed that Mtb uptakes and co-metabolizes multiple intracellular sources of nitrogen when replicating within its human host macrophage. These results identify amino acid metabolism as a target for TB therapeutics while also providing a systems-based tool that can be applied to study the nitrogen metabolism of other intracellular organisms.

Results

Mtb Co-assimilates Multiple Nitrogen Sources during Intracellular Growth

To measure the uptake and assimilation of nitrogen during the intracellular growth of Mtb, THP-1 human macrophages were infected with Mtb in the presence of a 15N tracer—aspartate (Asp), glutamate (Glu), glutamine (Gln), leucine (Leu), alanine (Ala), or glycine (Gly)—for 48 h, the isotopic steady-state labeling period established in our previous work (Beste et al., 2013). Asparagine was not tested, as it had previously been shown to be a nitrogen source for intracellular Mtb (Gouzy et al., 2014a). Proteinogenic amino acids were used for isotopomer analysis because they acquire the labeling pattern of their central metabolic precursors and are abundant and stable (Beste et al., 2013) (Figure S1, I). Using an identical method to that developed by Beste et al. (2013), macrophage and Mtb fractions were separated, and 15N incorporation into proteinogenic amino acids from infected macrophages and intracellular Mtb was measured using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Amino acid pairs of glutamate, glutamine and aspartate, asparagine (Asn) cannot be distinguished using GC-MS due to acid hydrolysis, so the 15N enrichments for these amino acid pairs are combined as glutamate/glutamine (Glu/n) and aspartate/asparagine (Asp/n), respectively. Experimental controls of uninfected THP-1 macrophages and in-vitro-grown Mtb were cultivated in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) containing each of the tracers for 48 h. These experiments established that the 15N labeling profile of proteinogenic amino acids from intracellular Mtb was distinct from that of Mtb in RPMI (Figures 1C and S1, II). For example, the labeled nitrogen from 15N1-Leu was incorporated predominantly into Leu when Mtb was tested in RPMI, but it was widely dispersed into other amino acids for Mtb growing intracellularly (Figure S1, IID). Similarly, for Mtb in RPMI, the label from 15N1-Asp, 15N1-Glu, and 15N2-Gln was incorporated into Asp/n and Glu/n. However, during intracellular growth, labeled nitrogen from 15N1-Asp was incorporated into almost all measured amino acids, including Asp/n and Glu/n (Figures S1, IIA–IIC). The distinct 15N labeling profiles of intracellular Mtb versus in-vitro-grown Mtb in RPMI demonstrated that there was negligible cross-contamination from extracellular Mtb in these experiments. Moreover, there was no cross-contamination during the separation of the macrophage and the intracellular Mtb, as evidenced by the unique labeling profile of proteinogenic amino acids from these two fractions (Figures 1A and 1C). The labeling profiles of proteinogenic amino acids from infected and uninfected macrophages were virtually identical, indicating that Mtb infection does not significantly perturb the nitrogen metabolism of macrophages (Figures 1A and 1B).

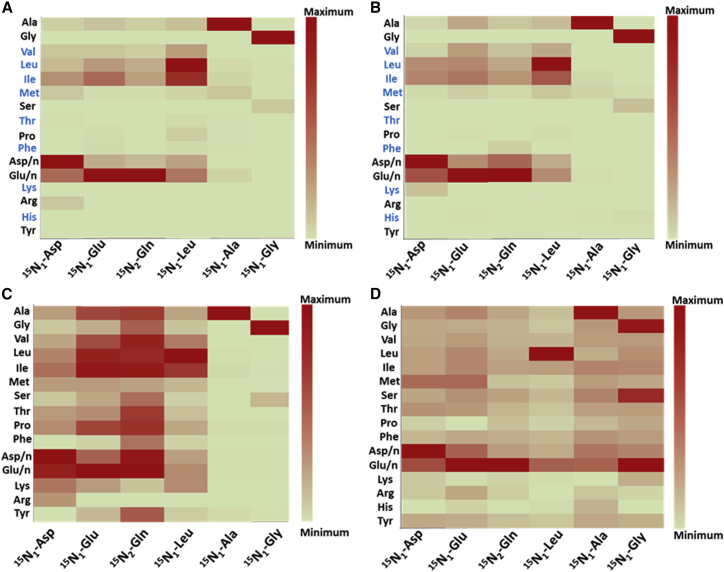

Figure 1.

Assimilation Pattern of Different Nitrogen Sources

(A–D) Heatmaps are shown for amino acids derived from Mtb-infected macrophages (A), uninfected macrophages (B), intracellular Mtb (C), and in-vitro-grown Mtb in rosins minimal media (D). Assimilation patterns are shown for six tracers: 15N1-Asp, 15N1-Glu, 15N2-Gln, 15N1-Leu, 15N1-Ala, and 15N1 Gly. Essential amino acids for macrophages are highlighted in blue. Heatmaps were produced using enrichment (%) of amino acids recorded for each of the individual tracer experiments in Data S1. The maximum and minimum enrichments for each heatmap are described using color keys. Enrichments are shown for the following amino acids: alanine (Ala), m/z 260; glycine (Gly), m/z 246; valine (Val), m/z 288; leucine (Leu), m/z 274; isoleucine (Ile), m/z 274; methionine (Met), m/z 320; serine (Ser), m/z 390; threonine (Thr), m/z 404; proline (Pro), m/z 258; phenylalanine (Phe), m/z 336; aspartate/asparagine (Asp/n), m/z 418; glutamate/glutamine (Glu/n), m/z 432; lysine (Lys), m/z 431; arginine (Arg), m/z 442; and tyrosine (Tyr), m/z 466, measured using GC-MS.

In accordance with expectations, most of the amino acids derived from macrophages remained unlabeled, reflecting their direct uptake from unlabeled nitrogen sources in the tissue culture media rather than from any transamination from the tracer (Figure 1A). This is not the case for intracellular Mtb. For example, labeled nitrogen from 15N1-Asp, 15N1-Glu, or 15N2-Gln was incorporated predominantly into Asp/n, Glu/n, and isoleucine (Ile) in the macrophage, but labeling was measured in nearly all amino acids derived from intracellular Mtb (Figures 1A and 1C). These data also reveal potential directions of transamination in Mtb. For example, nitrogen from 15N2-Gln was assimilated into six amino acids—Asp/n, Glu/n, Ile, Leu, valine (Val), or Ala in infected macrophages (Figure 1A)—whereas in Mtb, eight additional amino acids were labeled (Figure 1C). As the label from Gln has already been transaminated into several amino acids in the macrophage, any of those macrophage’s amino acids could be the source of the Mtb’s labeled nitrogen.

Nitrogen Metabolism Is Compartmentalized when Mtb Is Growing Intracellularly

Our results demonstrate that nitrogen was assimilated differently, depending on the original amino acid source in intracellular Mtb. We use the term “compartmentalization” to refer to the selective transfer of nitrogen from the tracers to other amino acids (Figure 1C). For example, nitrogen from 15N1-Asp, 15N1-Glu, 15N2-Gln, and 15N1-Leu was incorporated into many additional amino acids, but nitrogen from 15N1-Ala and 15N1-Gly was incorporated predominantly into only Ala, Gly, and serine (Ser) pools, respectively. The enrichment profiles for amino acids obtained from the tracers were also distinct. For example, more than 50% of 15N from 15N1-Asp was transferred to Glu/n: 15N1-Glu to six amino acids, 15N2-Gln to eight amino acids, and 15N1-Leu to Ile (Figures 1C and 2A). Also, some amino acids were preferentially labeled by particular tracers. For example, the labeling of tyrosine (Tyr) indicates that the nitrogen is transferred from 15N1-Glu/15N2-Gln but not from 15N1-Asp or any other tracers used. Similarly, nitrogen in arginine (Arg) can be donated by 15N1-Asp, but not from any other tested amino acid (Figure 1C). To investigate whether the compartmentalized nitrogen distribution is restricted to intracellular growth of Mtb, we performed similar 15N tracer experiments with Mtb grown in Roisin’s minimal media, with glycerol and ammonium chloride as the carbon and nitrogen source, respectively, with the addition of 15N labeled tracers. As can be seen, the results demonstrated compartmentalized distribution of 15N from Asp, Glu, Gln, Leu, Ala, and Gly in to the amino acid pools (Figures 2B and S2), extending the finding of Agapova et al. (2019), who demonstrated the compartmentalized distribution of nitrogen from Gln and Asn during in vitro growth of Mtb. It is noteworthy that the promiscuous pattern of distribution of nitrogen from both 15N1-Ala and 15N1-Gly in vitro is very different from the restricted distribution found for intracellular Mtb (Figures 1C, 2B, S3E, and S3F). To check whether this promiscuous label distribution in in-vitro-grown Mtb was biased by the experimental method, we harvested amino acids from in-vitro-grown Mtb using the same method as described for intracellular Mtb. We found no difference in label distribution from 15N1-Ala and 15N1-Gly in in-vitro-grown Mtb using the two methods, which confirmed that the non-promiscuous pattern of these tracers in intracellular Mtb was not experimentally biased (Figure S2, II). The non-promiscuous pattern for these two tracers in intracellular Mtb suggests that these amino acids are scarce, in comparison to other amino acids such as Gln within the Mtb phagosome, and are therefore incorporated directly into biomass by Mtb, rather than being used as nitrogen donors.

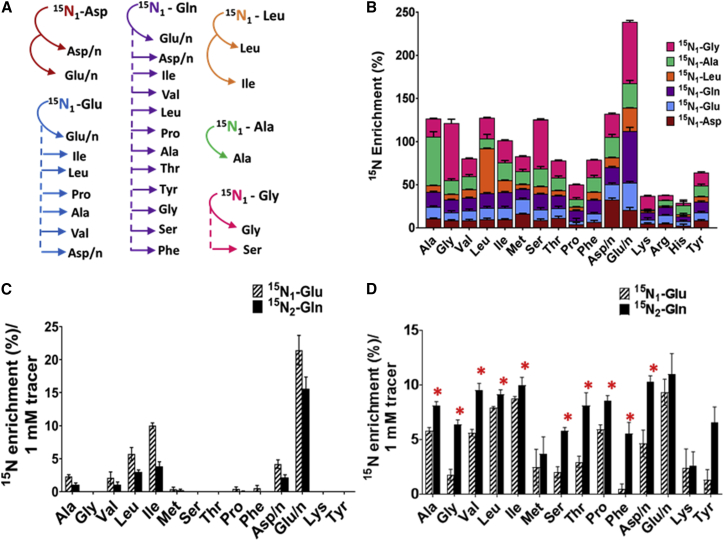

Figure 2.

Nitrogen Assimilation is Compartmentalized in Mtb

(A) Distinct enrichment of amino acids from each of the tracers in intracellular Mtb.

(B) 15N assimilation from the tracers into the amino acids in in-vitro-grown Mtb.

(C) Comparison of 15N enrichment from the tracers 15N1-Glu and 15N2-Gln in an infected macrophage.

(D) Comparison of 15N enrichment from the tracers 15N1-Glu and 15N2-Gln in intracellular Mtb.

Values are mean ± SEM from 3–4 biological replicates. Statistically significant differences were calculated using Holm-Sidak multiple t tests; ∗p < 0.001.

Out of all the nitrogen sources tested, nitrogen from 15N2-Gln was most widely distributed to other amino acids in intracellular Mtb, suggesting that Gln is the principal nitrogen donor for Mtb during intracellular growth (Figures 1C and 2A). The comparison of enrichment profiles between 15N1-Glu and 15N2-Gln demonstrated that both tracers gave similar 15N distribution patterns in amino acids derived from an uninfected macrophage and an infected macrophage (Figures 1A and 1B), but 15N2-Gln provided significantly higher enrichments than15N1-Glu for the majority of the intracellular Mtb amino acids (Figure 1C). Direct comparison of 15N1-Glu and 15N2-Gln demonstrated that there were no significant differences in enrichments between 15N1-Glu and 15N2-Gln in the macrophage (Figure 2C). But in the case of intracellular Mtb, using the tracer 15N2-Gln resulted in significant enrichments for the majority of amino acids (Figure 2D).

Uptake versus De Novo Synthesis of Amino Acids in Intracellular Mtb

To further evaluate the role of each macrophage amino acid pool in the provision of nitrogen to intracellular Mtb, we calculated the nitrogen incorporation ratio (NIR) between 15N enrichment of amino acids in intracellular Mtb and the same amino acid in the host macrophage. Amino acids acquired directly from the host that are not subject to any additional synthesis or metabolism will have similar 15N enrichment as the macrophage amino acids and an NIR of 1. De novo synthesis or additional metabolic processes, such as transamination reactions, will be revealed by different levels of 15N enrichment of amino acids in Mtb, compared with that of macrophage amino acids. Figures 3A–3G show the ratio of 15N enrichment for seven amino acids derived from intracellular Mtb compared with amino acids derived from infected macrophages. Amino acids Val, Ile, and Ala had an NIR of 1 for more than one tracer tested as the source of label, suggesting the uptake of these amino acids is directly from the macrophage by Mtb (Figures 3D–3F). Also, the NIR was >1 when 15N2-Gln was used as the tracer, suggesting the biosynthesis of these amino acids in addition to the uptake. Further clues as to the level of uptake versus biosynthesis can be gleaned from closer inspection of the data. For example, when 15N1-Asp was used as the label for the Asp/n pool, the NIR was <1 (Figure 3A), indicating that any Mtb Asp/n imported from the macrophage was being diluted with nitrogen from a source that was less labeled than the macrophage Asp/n pool. However, when 15N2-Gln was used as the tracer, the ratio for the Asp/n pools was >4, indicating that any Mtb Asp/n imported from the macrophage was being diluted with nitrogen from a source that was at least 4× more labeled than Asp/n pools from the macrophage. The same was not true when 15N1-Glu was the source of the label. The obvious conclusion is that the Asp’s nitrogen in Mtb is largely derived from the macrophage Gln. Overall, using the tracer 15N2-Gln resulted in the highest levels of labeling for the majority of the amino acids analyzed, confirming our previous conclusion that Gln is the predominant nitrogen donor for intracellular Mtb.

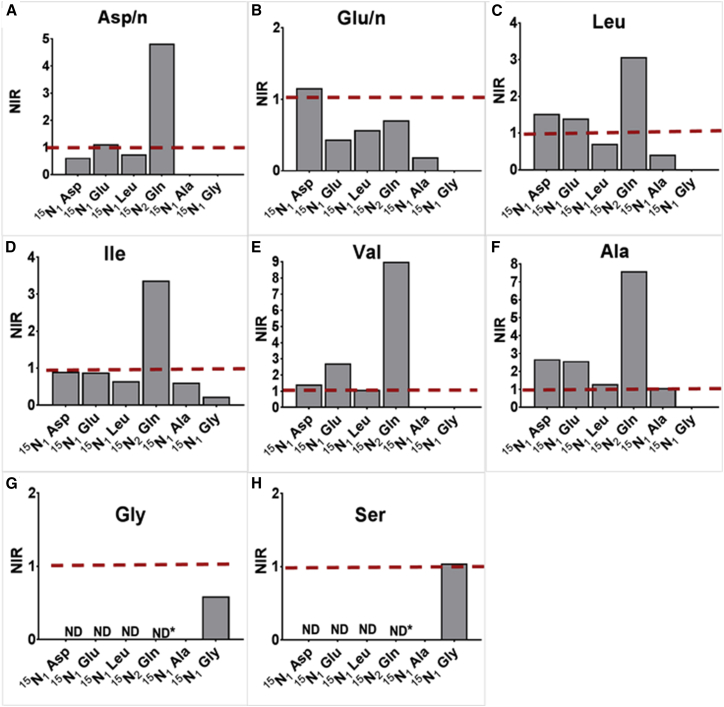

Figure 3.

Uptake versus De Novo Synthesis of Amino Acids in Intracellular Mtb

(A–H) The NIR of 15N enrichment (%) in intracellular Mtb to infected macrophages is shown for Asp/n, m/z 418 (A), Glu/n, m/z 432 (B), Leu, m/z 274 (C), Ile, m/z 274 (D), Val, m/z 288 (E), Ala, m/z 260 (F), Gly, m/z 246 (G), and Ser, m/z 390 (H). An NIR of 1 indicates that the particular amino acid in Mtb was acquired directly from the macrophage. NIRs were calculated from the enrichments measured from 3–8 individual macrophage infection experiments using the tracers 15N1-Asp, 15N1-Glu, 15N2-Gln, 15N1-Leu, 15N1-Ala, and 15N1-Gly. Ratios that were not determined for Gly (G) and Ser (H) are indicated by ND, and the asterisk indicates maximum 15N detected in Mtb from 15N2-Gln.

NIR analysis also revealed the exclusivity of nitrogen distribution in the Gly and Ser pools of intracellular Mtb (Figures 3G and 3H). Nitrogen from Gly is not promiscuous, as the label from 15N1-Gly remained with the Gly and Ser pools. Therefore, Gly is not a nitrogen donor for Mtb. For Gly, a homologous labeling with 15N1-Gly gave an NIR less than 1, indicating that Mtb’s Gly pool is being diluted by a less labeled nitrogen source, but not any of the tested amino acids, since none of them gave significant levels of incorporation into Gly (Figure 3G). None of the tracers tested provided nitrogen to Ser, except for Gly. The NIR of Ser was 1 for the label from 15N1-Gly, indicating the biosynthesis of Ser, in which imported Gly is converted to Ser in intracellular Mtb (Figure 3H).

Development of 15N-FSRA to Probe the Uptake of Nitrogen Sources from the Host by Mtb

Qualitative conclusions about the uptake of nitrogen sources can be drawn from simple labeling patterns generated by 15N1-Ala and 15N1-Gly (Figures S3, I and II); however, the Figure S3 NIR does not account for the intracellular redistribution of nitrogen. Here, we can use neither the traditional 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA), since we want to infer the uptake, nor our former 13C-FSA tool, since we have to take too many possible uptakes into account. We therefore developed 15N-FSRA to model the nitrogen source uptake by intracellular Mtb. This approach inputs data from the 15N tracer experiments into an in silico model of central nitrogen metabolism in Mtb, but without making a prior assumption on the number or combination of potential nitrogen sources. The method calculates the range of potential explanations in terms of nitrogen uptake flux relative to biomass contribution, which is consistent with the available labeling datasets simultaneously. We call this the flux spectral range (FSR). The FSR of an amino acid gives an unbiased possibilistic measure, reflecting the possible nitrogen flows.

A 15N metabolic model was constructed for Mtb including nitrogen atom transitions and reaction reversibilities (Data S2; Figure S4). The model was able to analyze the amino acid pairs Glu/Gln and Asp/Asn as separate pools and was solely constrained by the biomass equation taken from our previous work (Beste et al., 2011). The uptake of 15N labeled amino acids by Mtb was modeled by using the macrophage-derived amino acid mass isotopomer distributions as potential intracellular nitrogen sources. The measurements of all six tracer experiments were incorporated into the model. From the labeling data measurements, histidine (His), Arg, cysteine (Cys), and tryptophan (Trp) were excluded due to the low levels detected. The relative FSRs (minimum ratio, median, and maximum ratio) of amino acid nitrogen uptake flux to the nitrogen content of each amino acid in biomass were deduced (Data S3). For this analysis, amino acids with minimum/maximum FSR of ∼1 indicated that this amino acid is available in the macrophage and fully incorporated into Mtb’s biomass, whereas a minimum/maximum FSR of 0 indicates that the amino acid is unavailable and must be completely synthesized de novo by Mtb. A minimum or maximum FSR >1 indicates that the uptake of the amino acid is greater than the biomass requirements; therefore, this amino acid is a likely nitrogen donor. It should be noted that amino acids with FSRs between 0 and 1 may still be nitrogen donors, but the deficit in their uptake compared to biomass requirement must be made up by de novo synthesis with an alternative nitrogen source.

15N-FSRA identified 14 amino acids (minimum ratio > 0) that are available and taken up by intracellular Mtb from the macrophage (Table 1). Nine amino acids had FSRs between 0 and 1, and the biomass nitrogen requirement was met by de novo synthesis. The narrow FSR of 1 for Ala confirmed our previous analysis that this amino acid was taken up by Mtb from the macrophage and incorporated directly into the biomass. The analysis showed that Gln and Val are both used as nitrogen donors for the synthesis of other amino acids with high certainty (minimum FSR > 1). For Asp and Gly, the minimum FSR was >0 and the maximum >1, and they are synthesized de novo but could also be taken up by Mtb and used as nitrogen donors. Furthermore, our results revealed that nine amino acids (Asn, Ile, Leu, methionine [Met], Lys, Tyr, phenylalanine [Phe], proline [Pro], and threonine [Thr]) are synthetized de novo to suffice biomass requirements for growth in varying proportions, as seen from the narrow ratio ranges. The roles of Ser and Glu as nitrogen donors could not be resolved computationally, as the minimum FSR was 0 (not taken up from the macrophage) and maximum FSR > 1 (taken up in excess).

Table 1.

Flux Spectral Ranges Determined with 15N FSRA

| Category | Nitrogen Source | Flux Spectral Range |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum Ratio | Maximum Ratio | Median | ||

| ↓ | Asn | 0.06 | 0.19 | 0.13 |

| ↓ | Pro | 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.34 |

| ↓ | Thr | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.43 |

| ↓ | Ile | 0.52 | 0.64 | 0.55 |

| ↓ | Tyr | 0.57 | 0.63 | 0.60 |

| ↓ | Leu | 0.58 | 0.96 | 0.61 |

| ↓ | Met | 0.64 | 0.77 | 0.68 |

| ↓ | Phe | 0.63 | 0.75 | 0.69 |

| ↓ | Lys | 0.78 | 0.82 | 0.81 |

| → | Ala | 0.98 | 1 | 1 |

| 0/○ | Glu | 0 | 1.63 | 0.02 |

| 0/○ | Ser | 0 | 3.59 | 1.31 |

| ○ | Gly | 0.51 | 3.17 | 0.67 |

| ○ | Asp | 0.61 | 12.46 | 2.11 |

| ↑ | Gln | 1.50 | 11.85 | 2.47 |

| ↑ | Val | 1.82 | 13.45 | 2.88 |

Minimum and maximum FSRs for all computationally accessible amino acids and the median of their distributions (Data S3). Amino acids are grouped into five categories: ↓, spectral ranges in the interval [0,1) indicate that the biomass nitrogen need has to be fulfilled by de novo synthesis of the amino acid; →, spectral range is essentially 1, nitrogen biomass requirement is balanced with uptake, and no nitrogen is shared; 0, the amino acid is not taken up; ○, spectral range is inconclusive, as the amino acid might be synthesized de novo, but may also be a nitrogen donor; ↑, spectral ranges are larger then 1, indicating that this amino acid is available as a nitrogen donor.

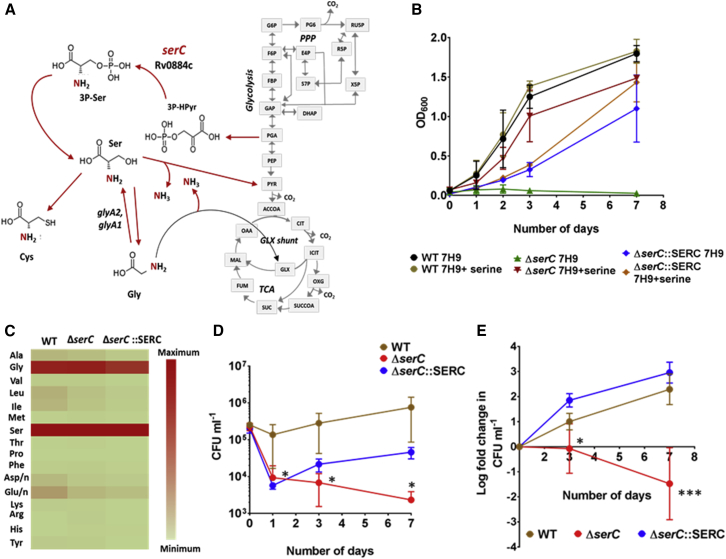

Serine Biosynthesis Is Essential for the Intracellular Survival of Mtb

15N-FSRA predicted the minimum FSR of Ser to be 0, indicating that there was no uptake of this amino acid from the macrophage and that its biosynthesis is essential for Mtb’s survival inside the host. To test this prediction, we constructed a serine auxotroph of Mtb and tested its survival in macropgaes. Ser is biosynthesized in a multistep reaction using 3-phosphoglyceric acid (PGA) as the precursor produced during glycolysis. Phosphoserine transaminase serC (Rv0884c) catalyzes the addition of nitrogen to the carbon backbone of pyruvate to form Ser (Figure 4A; Bai et al., 2011). In addition to being a proteinogenic amino acid, Ser provides the nitrogen backbone for the synthesis of Gly and Cys and also replenishes the pyruvate pool in central carbon metabolism (Figure 4A). Phosphoserine transaminase serC, the enzyme that aminated pyruvate to form Ser, was predicted to be essential for the growth of Mtb in vitro (DeJesus et al., 2017). Here, we successfully generated the ΔserC H37Rv Mtb strain. The ΔserC strain failed to grow without Ser supplementation, compared to the wild-type (WT) and the complemented strain, ΔserC::serC (Figure 4B), confirming serine auxotrophy. Unlike other nitrogen sources that were promiscuous when tested in in vitro (Figure 1D), Ser was not a widely assimilated in vitro nitrogen source; nitrogen from 15N1-Ser was distributed predominantly to Gly (Figure 4C). This result demonstrates the distinct nitrogen distribution between Ser and Gly via serine hydroxymethyltransferase glyA1, glyA2 (Figure 4A) and was in concord with our earlier analyses in Figures 1C and 3H. Furthermore, ΔserC was strongly attenuated for intracellular survival in THP-1 macrophages, as compared with WT H37Rv and the complemented strain (Figures 4D and 4E). These data validate the 15N-FRSA predictions and confirm that serine biosynthesis is essential for the intracellular survival of Mtb.

Figure 4.

Serine Biosynthesis Is Essential for the Intracellular Survival of Mtb

(A) Metabolic role of serC in Mtb. serC catalyzes the production of serine from pyruvate. Gly, Cys, and pyruvate are synthesized from Ser.

(B) Growth of wild-type (WT), ΔserC mutant, and complement ΔserC::SERC in 7H9 medium supplemented with 10% oleic acid, albumin, dextrose, and catalase (OADC) tested with and without the addition of Ser. Data are the average of three biological replicates ± SD.

(C) Assimilation of 15N1-SER by WT, ΔserC, and ΔserC::SERC in Rosin’s minimal medium with glycerol and NH4Cl. Data are the average of three biological replicates ± SD.

(D) Growth of WT, ΔserC, and ΔserC::SERC in THP-1 macrophages. CFUs (colony forming units) of the three strains were recorded for 0 (before infection), 1, 3, and 7 days post-infection.

(E) Fold change in CFUs of the three strains over the period of infection.

Data are the average of six independent infection experiments, each with three technical replicates for WT and ΔserC and one for infection with four technical replicates for ΔserC::SERC ± SD. Statistically significant reduction in CFU counts and fold change in CFUs for ΔserC as compared to the WT and complement was calculated using Student’s t test. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗∗p < 0.0005. PPP, pentose phosphate pathway; TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle; 3P-HPyr, 3-phosphonooxypyruvate; 3P-Ser, 3-Phosphoserine; Cys, cysteine; PGA, 3-phosphoglyceric acid; PYR, pyruvate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; GAP, glyceraldehyde 3phosphate; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; G6P, glucose-6-phosphate; F6P, fructose 6-phosphate; FBP, fructose bisphosphate; PG6, phosphogluconolactone; RU5P, riboluse 5-phosphate; R5P, ribose 5-phosphate; E4P, erythrose 4-phosphate; S7P, sedoheptoluse 7-phsophate; X5P, xylulose 5-phosphate; ACCCOA, AcetylCoA; OAA, oxaloacetic acid; MAL, malate; FUM, fumarate; SUC, succinate; SUCCOA, succinyl CoA; OXG, 2-oxoglutarate; ICIT, isocitrate; CIT, citrate.

Discussion

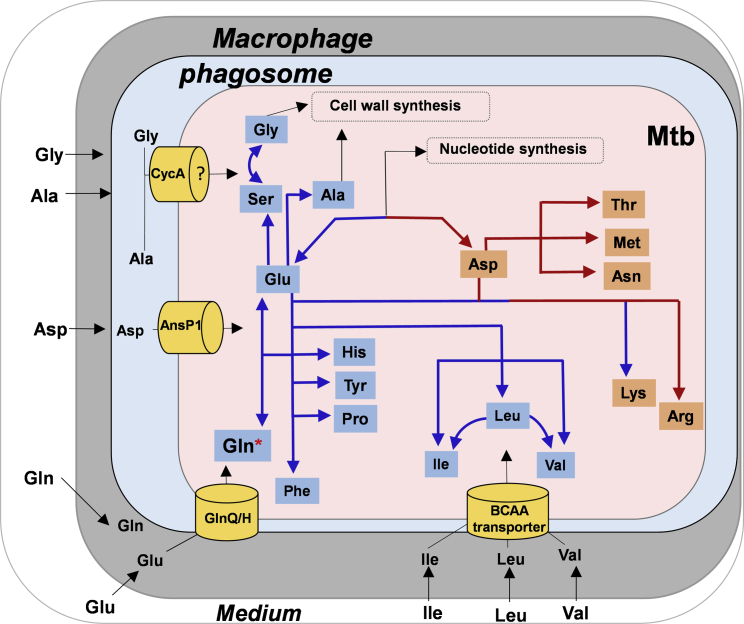

We and others have shown that Mtb co-metabolizes multiple carbon sources during intracellular growth in the human host cell (Beste et al., 2013, Ehrt et al., 2018, McKinney et al., 2000). Here, we demonstrate that this is also the case for nitrogen. Using 15N isotopomer profiling and 15N-FSRA systems-based inference tool, we describe the first nitrogen metabolic phenotype of Mtb inside human macrophages (Figure 5). With the 15N-FSRA tool, we predicted that Mtb has access to most amino acids within the macrophage (Table 1), and this uptake was insufficient to meet the biomass requirement for most tested amino acids and therefore must be complemented with de novo synthesis from nitrogen donors. This analysis identified the amino acids Asp, Glu, Gln, Val, Leu, Ala, and Gly as the intracellular nitrogen sources utilized by Mtb in human macrophages.

Figure 5.

Schematic Representation of Nitrogen Metabolism (Acquisition and Assimilation) in Intracellular Mtb

Macrophages acquires nitrogen sources Asp (aspartate), Glu (glutamate), Gln (glutamine), Leu (leucine), Ala (alanine), and Gly (glycine) directly from the growth media. Glu/Gln is taken from the host via yet-unidentified transporter. Asp is accessible to intraphagosomal Mtb, which it uptakes from the host macrophages via AnsP1 (Gouzy et al., 2014a). Leu, Ile (isoleucine), and Val (valine) are acquired from the host macrophages via yet-unindentified branched chain amino acid, probably an ABC-type transporter. Ala, Gly, and Ser are possibly acquired via CycA transport system. Gln, Val, and Asp were potential nitrogen donors for cellular protein synthesis, with Gln as the principal nitrogen donor in intracellular Mtb (indicated by asterisk). Nitrogen from Gln was transaminated primarily to Glu and Asp for the synthesis of other amino acids. Ala and Gly are assimilated mainly into Ala, Gly, and Ser pools. Limited transamination of nitrogen from Ala and Gly to other amino acids suggests direct assimilation of these two amino acids for biomass-cell wall synthesis.

Further analysis of the data demonstrated that, like carbon metabolism in Mtb (de Carvalho et al., 2010), nitrogen metabolism is compartmentalized (Figures 1C and 1D). Our in vitro results (Figure 1D) are consistent with the results of Agapova et al. (2019), who demonstrated that Mtb does not show a preference for any amino acids as nitrogen sources when grown in vitro. However, in this study, we demonstrate that this is clearly not the case for Mtb growing inside macrophages. Instead, the principal nitrogen source for intracellular Mtb appears to be Gln, but there is a clear pattern of compartmentalization of distribution of nitrogen with some sources: Gln is a highly promiscuous nitrogen donor, whereas other amino acids, such as Gly and Ala, have a restrictive pattern of nitrogen distribution. Metabolism has been shown to be compartmentalized in other bacteria with microcompartments, such as carboxysomes and metabolosomes, serving to compartmentalize enzymes involved in particular pathways and to restrict the exposure of toxic intermediates to the rest of the cell (Frank et al., 2013). For example, in Salmonella enterica, activity of the metabolosome was required to alleviate acetaldehyde toxicity during ethanolamine catabolism (Brinsmade et al., 2005). In the case of intracellular Mtb, different nitrogen sources might be assimilated using enzymes that are similarly localized. For example, enzymes glutamine synthetase and asparaginase are demonstrated to function extracellularly for the catabolism of Gln and Asn, respectively, in Mtb (Harth et al., 1994, Gouzy et al., 2014a) as a strategy to resist acidic stress inside the phagosome.

Earlier studies demonstrated that Asp is an intracellular nitrogen source for Mtb, and the pathways for Asp/n assimilation were recently described (Gouzy et al., 2013, Gouzy et al., 2014a). However, although our results confirm that Asp is indeed a nitrogen source, they also demonstrate that, of the tested amino acids, Gln is the principal source of nitrogen for intracellular Mtb and is the amino acid whose nitrogen is most widely assimilated (Figure 1C). Gln is the major fuel for a variety of mammalian cells including macrophages (Zhang et al., 2017), and THP-1 macrophages have previously been shown to assimilate Gln into Glu (Amorim Franco et al., 2017, Zhao et al., 2013, Choi and Park, 2018). Our previous study demonstrated that carbon from both Glu and Gln was available to Mtb inside the macrophage (Beste et al., 2013). Here, we additionally show that Gln, and not Glu, is the predominant nitrogen donor for intracellular Mtb. Once in Mtb, Gln can be converted to Glu by glutamate synthase (GltB) (Lee et al., 2018), and the nitrogen is transferred to other amino acids by various transaminases (Figure 5). Our results are thereby consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated that Glu/n biosynthesis is essential for the intracellular growth and survival of Mtb (Harper et al., 2008; Gallant et al., 2016, Ventura et al., 2013, Tullius et al., 2003). In addition to being the nitrogen donor for other amino acids, Glu/n is also involved in cell wall synthesis and resisting acid and nitrosative stress (Harth and Horwitz, 2003, Wietzerbin-Falszpan et al., 1973, Read et al., 2007). These studies, together with our results, establish Glu/n as the hub of nitrogen metabolism in intracellular Mtb. Gln was involved in modulating host cellular immune responses (Dos Santos et al., 2017), and Mtb infection increased macrophage’s metabolic dependency on Gln (Cumming et al., 2018). We found no significant changes in macrophage’s 15N2-Gln assimilation profile upon infection by Mtb (Figure 1A), but there could be an increase in the pool sizes of Gln and its related pathway intermediates. This leads to an intriguing hypothesis that Mtb may facilitate its own intracellular survival by metabolizing Gln in the host, and targeting Glu/n transport and metabolism therefore represents a promising avenue for the development of anti-TB drugs.

Biosynthesis of branched chain amino acids is also essential for the intracellular survival of Mtb (Awasthy et al., 2009). Here, we show that the branched chain amino acid Val is acquired directly by intracellular Mtb and is utilized as a nitrogen donor in addition to Gln (Figure 3; Table 1). Val was not directly tested as a tracer for the 15N experiments in the macrophage and intracellular Mtb, but the Val pool was 15N labeled from all of the amino acid tracers (except for 15N1-Ala and 15N1-Gly), suggesting that nitrogen was shared between Val and other amino acids. A Val auxotroph of Mtb was able to survive in macrophages (Awasthy et al., 2009); this is consistent with our FSRA predictions that intracellular Mtb acquired Val from the host. Nitrogen from Val is reversibly transaminated to Glu, Ile, and Leu by ilvE, the branched chain transaminase that is required for mycobacterial survival during infection in the mice model (Grandoni et al., 1998, Sassetti and Rubin, 2003, Tremblay and Blanchard, 2009). The demonstration by Zimmermann et al. (2017) that the biosynthetic genes for branched chain amino acids were downregulated when Mtb was growing intracellularly in macrophages is consistent with our evidence that these amino acids are also available in the phagosome. Our finding that nitrogen from Leu is assimilated by intracellular Mtb is surprising, since a ΔleuD auxotroph of Mtb was shown to be severely attenuated for growth and virulence in murine bone-marrow-derived macrophages and in mice, suggesting that Leu was unavailable to Mtb growing within its host (Chen et al., 2012, Hondalus et al., 2000, Sampson et al., 2004). The 15N-FSRA showed that Leu uptake is insufficient for Mtb’s biomass requirements, indicating that the uptake must be supplemented by de novo synthesis, consistent with the auxotrophic results.

Our previous work showed that the carbon backbone of Ala was acquired from the host and directly incorporated into Mtb’s biomass (Beste et al., 2013). Here, we show that Ala was not a nitrogen donor for intracellular Mtb (Figure 1C; Table 1). Gly was also a nitrogen source for intracellular Mtb, but its nitrogen was similarly not widely assimilated. Both Ala and Gly are components of the mycobacterial cell wall (Alderwick et al., 2015, Mahapatra et al., 2005, Wietzerbin-Falszpan et al., 1973), so it seems likely that these amino acids acquired from the host are directly incorporated into cell wall synthesis (Beste et al., 2013). 15N-FSRA predicted zero uptake of Ser, suggesting that its biosynthesis may be essential for the intracellular replication of Mtb and thereby a potential drug target. To test this hypothesis, we constructed a Ser auxotroph of Mtb and demonstrated that it is severely attenuated for growth in the macrophage. Our findings validate our systems-based approach and highlight Ser biosynthesis, and particularly the transaminase serC, as a potential drug target.

In addition to biosynthesis, the transport systems of nitrogen sources are potential targets for anti-TB drug development. However, there is only limited knowledge of the amino acid transport systems in Mtb (Cook et al., 2009). The Asp transporter AnsP1 is essential for the virulence of Mtb in murine models (Gouzy et al., 2013). Although Glu and branched chain amino transport systems are yet to be identified, the Streptococcus mutans and Lactococcus lactis glnQHMP system is known to transport Glu (Krastel et al., 2010, Fulyani et al., 2015), and Mtb encodes GlnQ and GlnP homologs that could function as Glu/n transporters (Cole et al., 1998, Braibant et al., 2000). The common transporter for Ala, Gly, and Ser, cycA, also remains unstudied (Awasthy et al., 2012, Chen et al., 2012, Cole et al., 1998). Further investigations are required to define these amino acid transporters of Mtb.

In summary, we describe the first nitrogen metabolic phenotype of intracellular Mtb and the development and application of a novel computational systems-based tool, 15N-FSRA, to investigate nitrogen uptake and assimilation of not only Mtb, but also any intracellular pathogen, in complement with direct isotopic labeling interpretation. In conclusion, we have identified that multiple nitrogen sources are acquired and assimilated by Mtb inside the host macrophages, and Gln is the principal intracellular nitrogen donor. The biosynthetic and transport systems of these identified nitrogen sources—and in particular, phosphoserine transaminase—involved in Ser biosynthesis are a target for the development of innovative anti-TB therapies.

STAR★Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Strains | ||

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv | Beste et al., 2013 | N/A |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis ΔserC H37Rv | This work | N/A |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis ΔserC::SERC | This work | N/A |

| Escherichia coli DH5α | Beste et al., 2011 | N/A |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| THP-1 human monocytic cell line | Beste et al., 2013 | ATCC TIB-202 |

| Chemicals, Peptides and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Middle brook7H11 agar | Sigma-Aldrich | M0428-500G |

| Middlebrook 7H9 | Sigma-Aldrich | M0178-500G |

| Oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase enrichment supplement-500ml | Becton Dickenson | 212351 (4312351) |

| Rosins minimal media | Beste et al., 2011 | N/A |

| Luria-Bertani (LB) medium | Sigma-Aldrich | L3027-250G |

| Glycerol | Sigma-Aldrich | G7893-1L |

| Tyloxapol | Sigma-Aldrich | T8761-50G |

| Fetal calf serum | Sigma-Aldrich | F9665-500ML |

| RPMI medium 1640 | Sigma-Aldrich | R0883 |

| 15N1 aspartic acid | Sigma-Aldrich | 332135-100MG |

| 15N1 leucine | Sigma-Aldrich | 340960-500MG |

| 15N1 glycine | Sigma-Aldrich | 299294-250MG |

| 15N2 glutamine | Sigma-Aldrich | 490032-250MG |

| 15N1 glutamic acid | Sigma-Aldrich | 332143-100MG |

| 15N1 alanine | Sigma-Aldrich | 332127-500MG |

| L-glutamine | Sigma-Aldrich | G7513-100ML |

| Hydrochloric acid | Sigma-Aldrich | 258148-500ML |

| Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate | Sigma-Aldrich | P8139-1MG |

| Phosphate buffer saline (PBS) | Sigma-Aldrich | D8537-500ML |

| NH4Cl | Sigma-Aldrich | 299251-20G |

| tert-butyldimethyl silyl chloride (TBDMSCl) | Sigma-Aldrich | 00942-10ML |

| Gigapack III Plus Packaging Extract | Agilent Technologies | 200204 |

| L-Serine | Sigma-Aldrich | S4500 |

| Q5 High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix | New England Biolabs | M0492S |

| 15N1-serine | Sigma-Aldrich | 609005-500MG |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Isotopomer Network Compartmental Analysis (INCA) | Young, 2014 | N/A |

| Metalign | Lommen, 2009 | N/A |

| 13CFLUX2 | Weitzel et al., 2013 | N/A |

| Omix | Omix Vizualization GmbH & Co. KG | |

| Chemstation | Agilent Technologies | N/A |

| Integrative Genomics Viewer | University of California | N/A |

| Snap Gene viewer | GSL Biotech LLC | N/A |

| Graph Pad Prism 8.0 | GraphPad Software | N/A |

| MATLAB | The MathWorks, Inc | N/A |

| NCBI Primer Blast | NIH | N/A |

| Other | ||

| Plasmid sequencing | Source Biosciences, UK | N/A |

| Whole genome sequencing | MicrobesNG, UK | N/A |

Lead Contact and Materials Availability

Further information and request for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Johnjoe McFadden (j.mcfadden@surrey.ac.uk). Plasmids and strains generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Sources of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, E. coli and cell lines used for this study are reported in the Key Resources Table.

Method Details

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) cultivation

Mtb, H37Rv was cultivated on Middle brook7H11 agar and Middlebrook 7H9 broth with 5% (v/v) oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase enrichment supplement and 0.5% (v/v) glycerol. Roisins minimal media was prepared with the composition described in Beste et al. (2011) and supplemented with 0.5% glycerol (v/v) as the carbon source and 10mM NH4Cl as nitrogen source, 0.1% tyloxapol (v/v) at 37°C with agitation (150 rpm).

THP-1 macrophage cultivation

The human monocytic THP-1 cell line was grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum at 37°C, 5% CO2 and 95% humidity. For 15N labeling experiments, modified RPMI supplemented with 0.2mM L-glutamine was used for testing 15N1 aspartic acid and 15N1 glutamic acid.RPMI without L-glutamine was used for testing 15N2 glutamine (sigma). RPMI-1640 with 200 mM L-glutamine was used for testing 15N1 leucine, 15N1 ala and 15N1 glycine.

15N isotopic labeling during infection of macrophages with Mtb

For infection, THP-1 cells and Mtb cultures were prepared as described in Beste et al., 2013. THP-1 cells (3 X 107) were differentiated into macrophages for 3 days using 50 nM Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate in a 175 cm2 tissue culture flasks. Macrophages were washed with warm PBS supplemented with 0.49 mM Mg2+ and 0.68 mM Ca2+ (PBS+) and 30 mL of RPMI media was added. Mtb was grown in 7H9 broth for a week to an optical density of 1 (1 × 108 colony forming units per ml). Mtb cultures were washed 3 times with PBS and resuspended in RPMI media and added to the macrophages at a multiplicity of infection- 5. Each amino acid tracer except for 15N2 glutamine was then added to the Mtb-infected macrophages at 3 times the concentration of that unlabelled amino acid present in the RPMI. For 15N2 glutamine experiment, RPMI without unlabelled glutamine was used, because a large amount of unlabelled glutamine was present in RPMI as compared to other amino acids. To reduce the costs of the 15N2 glutamine labeling experiment, the only glutamine in this RPMI was the tracer itself, added at 1 mM concentration which previously demonstrated by Tullius et al., 2003 and also confirmed in this study to have no detrimental effect on the macrophages (data not shown). The final concentration of tracers added during infection were- 0.6 mM 15N1 aspartic acid, 0.53 mM 15N1 glutamic acid, 0.8 mM 15N1 leucine, 0.3 mM 15N1 alanine, 1 mM 15N2 glutamine and 0.4 mM 15N1 glycine. Mtb infected macrophages were incubated for 3-4 h at 37°C, 5% CO2 and 95% humidity. After incubation, macrophages were washed 3 times with PBS, tracers were added and left for 48 h at 37°C, 5% CO2 and 95% humidity. After incubation for 48 h, macrophages were washed with cold PBS and Mtb cultures were harvested from macrophages using differential centrifugation (Beste et al., 2013). Amino acid hydrolysates were prepared from macrophage and Mtb using 6 M hydrochloric acid and incubation at 100°C for 24 h. The validity of the method for labeled amino acid extraction from intracellular Mtb was confirmed by comparing the nitrogen assimilation pattern obtained in RPMI grown labeled Mtb (control) (Figure S1, II). The control was set up by washing Mtb cultures with PBS and resuspending in RPMI for 48 h with equal amounts of 15N isotope tracers that was previously used for infection assays. After 48 h, Mtb in RPMI were harvested followed preparation of amino acid hydrolysate.

In vitro15N isotopic labeling

Mtb was grown in Roisins minimal spiked with 15N isotope tracers and left for 48 h at 37°C and cultures were agitated at 150 rpm. After 48 h, Mtb cultures were washed with triton, PBS and RIPA buffer. Cultures were harvested and amino acid hydrolysate was prepared by boiling Mtb in 6M hydrochloric acid for 24 h.

Gas-chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and 15N mass isotopomer analysis

Amino acid hydrolysates were dried and derivatized using pyridine and tert-butyldimethyl silyl chloride (TBDMSCl) (sigma) (Rossi et al., 2017, Masakapalli et al., 2013). Amino acids were analyzed using a VF-5ms inert 5% phenyl-methyl column (Agilent Technologies) on a GC-MS system. MS data were extracted using chemstation GC-MS software and were baseline corrected using Metalign (Lommen, 2009). Mass data were corrected for natural isotope effects using Isotopomer network compartmental analysis (INCA) platform (Young, 2014). Average 15N in an amino acid was calculated from the fractional abundance of the mass isotopomer in the entire fragment. For this study measurements > 1% were considered to be significantly enriched by the 15N tracers.

Nitrogen network model (of Mtb)

A nitrogen transition model was set up for Mtb using information available in databases (KEGG, BioCyc, Tuberculist) and literature. The network model comprises the amino acid biosynthesis pathways of all 20 proteinogenic amino acids, as well as a simplified nucleotide biosynthesis formulation. Reaction reversibilities and requirements for growth were taken from Beste et al. (2011). For 20 protein-derived amino acids unidirectional uptake reactions were formulated while it was assumed that no backflow of nitrogen from Mtb to the phagosome exists. The mass isotopomers observed in the macrophage were deconvolved into distributions of isotopomer species and modeled by additional reactions (Figure S4). For comparability of the inference results across different nitrogen uptake constellations, flux values were formulated relative to the biomass synthesis rate. In total, the model has 98 independent fluxes, from which 50 are intracellular (40 net, 10 exchange) and 48 nuisance fluxes for modeling the deconvolution of the substrate species. This nitrogen transition template model was then duplicated per dataset to give rise to a sextuple model (Beyß et al., 2019), where each sub-model shared flux values, biomass requirements, and growth rate. Eventually, the sextuple model had 338 free fluxes (50 intracellular and 288 nuisance fluxes) that had to be inferred from 264 independent labeling measurements (15 measurement groups for Mtb and the host, respectively (Data S2; Figure S4).

15N Flux Spectral Range Analysis (15N-FSRA)

15N-FSRA borrows the concept of parallel data integration from COMPLETE-MFA (Leighty and Antoniewicz, 2013) which, however, was reformulated resigning the knowledge of the experimentally inaccessible specific amino acid uptake rates and amending the traditional least-squares fitting approach by a tailored regularization approach to punish model complexity. In short, a penalty term was added to the weighted least-squares functional

| (1) |

where are the (independent) fluxes, the measured/simulated data, the measurement covariance matrix, and regularization parameters punishing non-zero flux values ( and ).

A multi-start optimization strategy was applied to safeguard against local minima while solving Equation (1). The flux fitting procedure was performed with the high-performance simulator 13CFLUX2 (Weitzel et al., 2013) using the multifitfluxes module with 1,000 randomly sampled starting points and the NAG C optimization library (Version 6.23, Oxford, UK) with a maximum number of 250 iterations. From the 1,000 runs, those with residuals less than a cut-off of 203.5 were accepted (the overall optimal residual value was 182.01, corresponding to a χ2 value > 99.99%, Data S3 and S4). This resulted in 800 accepted fits. From these accepted estimated flux distributions, FSRs (minimum, maximum, median) for each flux were derived (Table 1). Histograms of all FSRs are available in supplemental data file S4.

Construction of serC (Rv0884c) knockout strain of H37Rv

The knockout (KO) strain ΔserC was constructed using the bacteriophage mediated transduction of wild-type H37Rv (Bardarov et al., 2002). The strains and plasmid and primers used for this work are listed in Table S1A, B. Briefly, the allelic exchange vector was constructed by cloning upstream and downstream flanking regions of serC gene into the cosmid vector pYUB854with res sites flanking the hygromycin resistance (HYGR) gene. The recombinant cosmid with the allelic exchange substrates was cloned into the PacI site of the temperature sensitive shuttle phasmid phAEB159 using an in vitro λ-packaging reaction (GIGA PackII). The mycobacteriophage containing the recombinant pYUB854 was used for transduction of H37Rv. Bacterial cultures were grown up to exponential phase and washed with pre-warmed 7H9 no tween at 37°C. Phage was added at an m.o.i of 10 and incubated at 37°C for 4 h. After infection, cells were spun and plated onto 7H11 agar plates containing 100 μg ml-1 hygromycin and 50 μg ml-1 L-serine. Plates were incubated for 3 weeks and single colonies were picked for mutant screening. The knockout strain was confirmed by whole genome sequencing analysis where serC gene was deleted in H37Rv (Figure S6A, S6B; Data S5).

Construction of the complement strain ΔserC::SERC H37Rv

The complement strain was constructed using the integrating shuttle plasmid pMV361 with hsp60 promoter E. coli origin of replication (oriE), the attP and int genes of mycobacteriophage L5 (for integration in the mycobacterial chromosome) and a kanamycin resistance gene (Kanr) (Stover et al., 1991). serC was amplified using wild-type H437Rv genomic DNA as the template and primers with EcoRI and HindIII restriction site (Table S1). The amplified fragment was cloned into pMV361 EcoRI and HindIII sites downstream of the hsp60 promoter. The recombinant plasmid was transformed into E. coli DH5α competent cells and plated onto LB agar containing 50 μg ml-1 kanamycin. Transformants were confirmed by digestion of the pMV361serC construct with EcoRI and HindIII. The construct was electroporated into the KO strain ΔserC and plated onto 7H11 agar plates containing 100 μg ml-1 hygromycin and 25 μg ml-1 kanamycin. Plates were incubated for 3 weeks and single colonies were picked for complement strain screening. Genomic DNA of the complement strain was isolated and the fragment containing hsp60 promoter and serC gene was amplified. The complement strain had a PCR product of size 923 kb, identical to that of the construct pMV361serC confirming the complementation of the KO strain Figure S7B.

Growth of ΔserC and ΔserC::SERC H37Rv strains

For cultivation in agar plates, strains were grown in 7H11 agar supplemented with OADC. For ΔserC L-serine was added to the 7H11 + OADC plates at a concentration of 5mM and hygromycin at 100 μg ml-1. For ΔserC::SERC H37Rv, kanamycin was added at 25 μg ml-1 to the 7H11 + OADC plates. For liquid cultures, strains were grown in 7H9 medium with OADC. To test for auxotrophy, ΔserC was grown in 7H9 with and without 5mM L-serine. WT and complement was grown in parallel in 7H9 medium with and without serine for comparison with the mutant.

Macrophage infections with WT, ΔserC and ΔserC::SERC H37Rv strains

THP-1 macrophages were cultivated as described in Beste et al. (2013) and 5 X 105 cells were seeded for each infection. WT, mutant and complement strains were added to the macrophages at an m.o.i of 0.1 for 4 h. After 4 h macrophages were washed and fresh RPMI medium with 10% FBS was added. Macrophage survivability upon infection with the strains was monitored using crystal violet assays during the period of infection (data not shown). For bacterial survivability test, macrophages were lysed with 0.1% Triton X-100 at specific time points- 0 (inoculum before infection of macrophage), day 1, day 3 and day 7, and plated on 7H11 agar plates with OADC. 7H11 plates for ΔserC strain were supplemented with 5mM serine and hygromycin was added at 100 μg ml-1, and for ΔserC::SERC strain, kanamycin was added at 25 μg ml-1. Plates were incubated for 3 weeks at 37°C and colony forming unit ml-1 were recorded for the three strains.

15N1-serine isotopic labeling

Starter cultures of WT, mutant and complement strains were cultivated in 7H9 medium with OADC, 5mM L-serine and respective antibiotics for 4-5 days. For labeling experiments, starter cultures were spun and re-suspended Roisin’s minimal medium containing glycerol and ammonium chloride as carbon and nitrogen sources respectively, and with 50 μg ml-1 15N1-serine. Cultures were incubated for 48 h at 37°C. After incubation, cultures were spun and amino acid hydrolysates were prepared as described previously. 15N enrichment of amino acids was performed with GC-MS as described previously.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t test and significant differences were calculated using Holm Sidak method in graph pad prism 8.0. The details of number and type of replicate measurements used for calculating mean and standard error of the mean (SEM) are included in figure legends. Residual values for FSRA predictions (minimum, maximum, median) were calculated in 13CFLUX2 software and are described in details in the methods section.

Data and Code Availability

Data generated in this study are available in the supplemental items

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) grant (BB/L022869/1) and Medical Research Council (MR/K01224X/1), United Kingdom.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.B., D.J.V.B., K.N., and J.M.; Methodology, K.B., D.J.V.B., J.M., and K.N.; Investigation, K.B., M.B., and T.A.M.; Writing – Original Draft, K.B., D.J.V.B., and J.M.; Writing – Review and Editing, K.B., H.W., P.B., T.A.M., M.B., K.N., D.J.V.B., and J.M.; Funding Acquisition, D.J.V.B. and J.M.; Resources, J.M.; Supervision, K.N., D.J.V.B. and J.M.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: December 10, 2019

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2019.11.037.

Supplemental Information

References

- Agapova A., Serafini A., Petridis M., Hunt D.M., Garza-Garcia A., Sohaskey C.D., de Carvalho L.P.S. Flexible nitrogen utilisation by the metabolic generalist pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis. eLife. 2019;8:e41129. doi: 10.7554/eLife.41129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderwick L.J., Harrison J., Lloyd G.S., Birch H.L. The Mycobacterial Cell Wall--Peptidoglycan and Arabinogalactan. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015;5:a021113. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amorim Franco T.M., Favrot L., Vergnolle O., Blanchard J.S. Mechanism-Based Inhibition of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis branched-chain aminotransferase by d- and l-cycloserine. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017;12:1235–1244. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasthy D., Gaonkar S., Shandil R.K., Yadav R., Bharath S., Marcel N., Subbulakshmi V., Sharma U. Inactivation of the ilvB1 gene in Mycobacterium tuberculosis leads to branched-chain amino acid auxotrophy and attenuation of virulence in mice. Microbiology. 2009;155:2978–2987. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.029884-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasthy D., Bharath S., Subbulakshmi V., Sharma U. Alanine racemase mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis require D-alanine for growth and are defective for survival in macrophages and mice. Microbiology. 2012;158:319–327. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.054064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G., Schaak D.D., Smith E.A., McDonough K.A. Dysregulation of serine biosynthesis contributes to the growth defect of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis crp mutant. Mol. Microbiol. 2011;82:180–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardarov S., Bardarov S., Jr., Pavelka M.S., Jr., Sambandamurthy V., Larsen M., Tufariello J., Chan J., Hatfull G., Jacobs W.R., Jr. Specialized transduction: an efficient method for generating marked and unmarked targeted gene disruptions in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M. bovis BCG and M. smegmatis. Microbiology. 2002;148:3007–3017. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-10-3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beste D.J., Bonde B., Hawkins N., Ward J.L., Beale M.H., Noack S., Nöh K., Kruger N.J., Ratcliffe R.G., McFadden J. 13C metabolic flux analysis identifies an unusual route for pyruvate dissimilation in mycobacteria which requires isocitrate lyase and carbon dioxide fixation. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002091. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beste D.J., Nöh K., Niedenführ S., Mendum T.A., Hawkins N.D., Ward J.L., Beale M.H., Wiechert W., McFadden J. 13C-flux spectral analysis of host-pathogen metabolism reveals a mixed diet for intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Chem. Biol. 2013;20:1012–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyß M., Azzouzi S., Weitzel M., Wiechert W., Nöh K. The design of fluxml: a universal modeling language for 13C metabolic flux analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:1022. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braibant M., Gilot P., Content J. The ATP binding cassette (ABC) transport systems of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2000;24:449–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinsmade S.R., Paldon T., Escalante-Semerena J.C. Minimal functions and physiological conditions required for growth of salmonella enterica on ethanolamine in the absence of the metabolosome. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:8039–8046. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.23.8039-8046.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buescher J.M., Antoniewicz M.R., Boros L.G., Burgess S.C., Brunengraber H., Clish C.B., DeBerardinis R.J., Feron O., Frezza C., Ghesquiere B. A roadmap for interpreting (13)C metabolite labeling patterns from cells. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2015;34:189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.M., Uplekar S., Gordon S.V., Cole S.T. A point mutation in cycA partially contributes to the D-cycloserine resistance trait of Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccine strains. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e43467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y.K., Park K.G. Targeting glutamine metabolism for cancer treatment. Biomol. Ther. (Seoul) 2018;26:19–28. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2017.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole S.T., Brosch R., Parkhill J., Garnier T., Churcher C., Harris D., Gordon S.V., Eiglmeier K., Gas S., Barry C.E., 3rd Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook G.M., Berney M., Gebhard S., Heinemann M., Cox R.A., Danilchanka O., Niederweis M. Physiology of mycobacteria. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 2009;55:81–182. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(09)05502-7. 318–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley S., Ko M., Pick N., Chow R., Downing K.J., Gordhan B.G., Betts J.C., Mizrahi V., Smith D.A., Stokes R.W., Av-Gay Y. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein serine/threonine kinase PknG is linked to cellular glutamate/glutamine levels and is important for growth in vivo. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;52:1691–1702. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumming B.M., Addicott K.W., Adamson J.H., Steyn A.J. Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces decelerated bioenergetic metabolism in human macrophages. eLife. 2018;7:e39169. doi: 10.7554/eLife.39169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das P., Lahiri A., Lahiri A., Sen M., Iyer N., Kapoor N., Balaji K.N., Chakravortty D. Cationic amino acid transporters and Salmonella Typhimurium ArgT collectively regulate arginine availability towards intracellular Salmonella growth. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e15466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho L.P., Fischer S.M., Marrero J., Nathan C., Ehrt S., Rhee K.Y. Metabolomics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis reveals compartmentalized co-catabolism of carbon substrates. Chem. Biol. 2010;17:1122–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJesus M.A., Gerrick E.R., Xu W., Park S.W., Long J.E., Boutte C.C., Rubin E.J., Schnappinger D., Ehrt S., Fortune S.M. Comprehensive Essentiality Analysis of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Genome via Saturating Transposon Mutagenesis. MBio. 2017;8:e02133-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02133-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos G.G., Hastreiter A.A., Sartori T., Borelli P., Fock R.A. L-Glutamine in vitro Modulates some Immunomodulatory Properties of Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2017;13:482–490. doi: 10.1007/s12015-017-9746-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrt S., Rhee K. Mycobacterium tuberculosis metabolism and host interaction: mysteries and paradoxes. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2013;374:163–188. doi: 10.1007/82_2012_299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrt S., Schnappinger D., Rhee K.Y. Metabolic principles of persistence and pathogenicity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018;16:496–507. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0013-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eylert E., Herrmann V., Jules M., Gillmaier N., Lautner M., Buchrieser C., Eisenreich W., Heuner K. Isotopologue profiling of Legionella pneumophila: role of serine and glucose as carbon substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:22232–22243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.128678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenreich W., Dandekar T., Heesemann J., Goebel W. Carbon metabolism of intracellular bacterial pathogens and possible links to virulence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;8:401–412. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eoh H., Wang Z., Layre E., Rath P., Morris R., Branch Moody D., Rhee K.Y. Metabolic anticipation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Microbiol. 2017;2:17084. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eylert E., Schär J., Mertins S., Stoll R., Bacher A., Goebel W., Eisenreich W. Carbon metabolism of Listeria monocytogenes growing inside macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;69:1008–1017. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn J.L. Lessons from experimental Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:1179–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank S., Lawrence A.D., Prentice M.B., Warren M.J. Bacterial microcompartments moving into a synthetic biological world. J. Biotechnol. 2013;163:273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulyani F., Schuurman-Wolters G.K., Slotboom D.J., Poolman B. Relative rates of amino acid import via the ABC transporter GlnPQ determine the growth performance of Lactococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 2015;198:477–485. doi: 10.1128/JB.00685-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant J.L., Viljoen A.J., van Helden P.D., Wiid I.J. Glutamate dehydrogenase is required by Mycobacterium bovis BCG for resistance to cellular Stress. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0147706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouzy A., Larrouy-Maumus G., Wu T.D., Peixoto A., Levillain F., Lugo-Villarino G., Guerquin-Kern J.L., de Carvalho L.P., Poquet Y., Neyrolles O. Mycobacterium tuberculosis nitrogen assimilation and host colonization require aspartate. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013;9:674–676. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouzy A., Larrouy-Maumus G., Bottai D., Levillain F., Dumas A., Wallach J.B., Caire-Brandli I., de Chastellier C., Wu T.D., Poincloux R. Mycobacterium tuberculosis exploits asparagine to assimilate nitrogen and resist acid stress during infection. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003928. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouzy A., Poquet Y., Neyrolles O. Amino acid capture and utilization within the Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome. Future Microbiol. 2014;9:631–637. doi: 10.2217/fmb.14.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouzy A., Poquet Y., Neyrolles O. Nitrogen metabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis physiology and virulence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014;12:729–737. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandoni J.A., Marta P.T., Schloss J.V. Inhibitors of branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis as potential antituberculosis agents. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1998;42:475–482. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper C., Hayward D., Wiid I., van Helden P. Regulation of nitrogen metabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a comparison with mechanisms in Corynebacterium glutamicum and Streptomyces coelicolor. IUBMB Life. 2008;60:643–650. doi: 10.1002/iub.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harth G., Horwitz M.A. Inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis glutamine synthetase as a novel antibiotic strategy against tuberculosis: demonstration of efficacy in vivo. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:456–464. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.1.456-464.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harth G., Clemens D.L., Horwitz M.A. Glutamine synthetase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: extracellular release and characterization of its enzymatic activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:9342–9346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondalus M.K., Bardarov S., Russell R., Chan J., Jacobs W.R., Jr., Bloom B.R. Attenuation of and protection induced by a leucine auxotroph of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:2888–2898. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2888-2898.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloosterman T.G., Kuipers O.P. Regulation of arginine acquisition and virulence gene expression in the human pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae by transcription regulators ArgR1 and AhrC. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:44594–44605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.295832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krastel K., Senadheera D.B., Mair R., Downey J.S., Goodman S.D., Cvitkovitch D.G. Characterization of a glutamate transporter operon, glnQHMP, in Streptococcus mutans and its role in acid tolerance. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192:984–993. doi: 10.1128/JB.01169-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Jeon B.Y., Bardarov S., Chen M., Morris S.L., Jacobs W.R., Jr. Protection elicited by two glutamine auxotrophs of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and in vivo growth phenotypes of the four unique glutamine synthetase mutants in a murine model. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:6491–6495. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00531-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.J., Lim J., Gao S., Lawson C.P., Odell M., Raheem S., Woo J., Kang S.H., Kang S.S., Jeon B.Y., Eoh H. Glutamate mediated metabolic neutralization mitigates propionate toxicity in intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:8506. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26950-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighty R.W., Antoniewicz M.R. COMPLETE-MFA: complementary parallel labeling experiments technique for metabolic flux analysis. Metab. Eng. 2013;20:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W., Mathys V., Ang E.L.Y., Koh V.H.Q., Martínez Gómez J.M., Ang M.L.T., Zainul Rahim S.Z., Tan M.P., Pethe K., Alonso S. Urease activity represents an alternative pathway for Mycobacterium tuberculosis nitrogen metabolism. Infect. Immun. 2012;80:2771–2779. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06195-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofthouse E.K., Wheeler P.R., Beste D.J.V., Khatri B.L., Wu H., Mendum T.A., Kierzek A.M., McFadden J. Systems-based approaches to probing metabolic variation within the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e75913. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lommen A. MetAlign: interface-driven, versatile metabolomics tool for hyphenated full-scan mass spectrometry data preprocessing. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:3079–3086. doi: 10.1021/ac900036d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra S., Scherman H., Brennan P.J., Crick D.C. N Glycolylation of the nucleotide precursors of peptidoglycan biosynthesis of Mycobacterium spp. is altered by drug treatment. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:2341–2347. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.7.2341-2347.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masakapalli S.K., Kruger N.J., Ratcliffe R.G. The metabolic flux phenotype of heterotrophic Arabidopsis cells reveals a complex response to changes in nitrogen supply. Plant J. 2013;74:569–582. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdam R.A., Weisbrod T.R., Martin J., Scuderi J.D., Brown A.M., Cirillo J.D., Bloom B.R., Jacobs W.R., Jr. In vivo growth characteristics of leucine and methionine auxotrophic mutants of Mycobacterium bovis BCG generated by transposon mutagenesis. Infect. Immun. 1995;63:1004–1012. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.1004-1012.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney J.D., Höner zu Bentrup K., Muñoz-Elías E.J., Miczak A., Chen B., Chan W.T., Swenson D., Sacchettini J.C., Jacobs W.R., Jr., Russell D.G. Persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages and mice requires the glyoxylate shunt enzyme isocitrate lyase. Nature. 2000;406:735–738. doi: 10.1038/35021074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederweis M. Nutrient acquisition by mycobacteria. Microbiology. 2008;154:679–692. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/012872-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read R., Pashley C.A., Smith D., Parish T. The role of GlnD in ammonia assimilation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 2007;87:384–390. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M.T., Kalde M., Srisakvarakul C., Kruger N.J., Ratcliffe R.G. Cell-type specific metabolic flux analysis:a challenge for metabolic phenotyping and a potential solution in plants. Metabolites. 2017;7:E59. doi: 10.3390/metabo7040059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D.G. Mycobacterium tuberculosis: here today, and here tomorrow. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:569–577. doi: 10.1038/35085034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustad T.R., Sherrid A.M., Minch K.J., Sherman D.R. Hypoxia: a window into Mycobacterium tuberculosis latency. Cell. Microbiol. 2009;11:1151–1159. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson S.L., Dascher C.C., Sambandamurthy V.K., Russell R.G., Jacobs W.R., Jr., Bloom B.R., Hondalus M.K. Protection elicited by a double leucine and pantothenate auxotroph of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in guinea pigs. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:3031–3037. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.5.3031-3037.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassetti C.M., Rubin E.J. Genetic requirements for mycobacterial survival during infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:12989–12994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2134250100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnappinger D., Ehrt S., Voskuil M.I., Liu Y., Mangan J.A., Monahan I.M., Dolganov G., Efron B., Butcher P.D., Nathan C., Schoolnik G.K. Transcriptional adaptation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis within macrophages: insights into the phagosomal environment. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:693–704. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D.A., Parish T., Stoker N.G., Bancroft G.J. Characterization of auxotrophic mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and their potential as vaccine candidates. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:1142–1150. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.2.1142-1150.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover C.K., de la Cruz V.F., Fuerst T.R., Burlein J.E., Benson L.A., Bennett L.T., Bansal G.P., Young J.F., Lee M.H., Hatfull G.F. New use of BCG for recombinant vaccines. Nature. 1991;351:456–460. doi: 10.1038/351456a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay L.W., Blanchard J.S. The 1.9 A structure of the branched-chain amino-acid transaminase (IlvE) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2009;65:1071–1077. doi: 10.1107/S1744309109036690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tullius M.V., Harth G., Horwitz M.A. Glutamine synthetase GlnA1 is essential for growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human THP-1 macrophages and guinea pigs. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:3927–3936. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.3927-3936.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura M., Rieck B., Boldrin F., Degiacomi G., Bellinzoni M., Barilone N., Alzaidi F., Alzari P.M., Manganelli R., O’Hare H.M. GarA is an essential regulator of metabolism in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 2013;90:356–366. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viljoen A.J., Kirsten C.J., Baker B., van Helden P.D., Wiid I.J. The role of glutamine oxoglutarate aminotransferase and glutamate dehydrogenase in nitrogen metabolism in Mycobacterium bovis BCG. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e84452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]