Abstract

Adolescent dating violence (ADV) is a pressing public health problem in North America. Strategies to prevent perpetration are needed, and a substantial body of research demonstrates the importance of applying a gender lens to target root causes of adolescent dating violence as part of effective prevention. To date, however, there has been limited research on how to specifically engage boys in adolescent dating violence prevention. In this short communication, we describe the protocol for a longitudinal, quasi-experimental outcome evaluation of a program called WiseGuyz. WiseGuyz is a community-facilitated, gender-transformative healthy relationships program for mid-adolescent male-identified youth that aims to reduce male-perpetrated dating violence and improve mental and sexual health, by allowing participants to critically examine and deconstruct male gender role expectations. The primary goal of this evaluation is to explore the impact of WiseGuyz on adolescent dating violence outcomes at one-year follow-up among participants, as compared to a risk- and demographically-matched comparison group. Knowledge generated and shared from this project will provide evidence on if and for whom WiseGuyz works, with important implications for adolescent health and well-being.

Keywords: Adolescent, Male, Violence prevention, Healthy relationships, Gender transformative

Abbreviations: ADV, Adolescent dating violence

1. Introduction

The prevention of adolescent dating violence (ADV) is a pressing public health task [1,2], and healthy relationships-based prevention approaches are promising [[3], [4], [5], [6]]. To date, most evidence-based healthy relationships ADV prevention programs have focused on individual skills needed for healthy relationships, such as communication/conflict negotiation skills ex. [3,7]. However, ecological and feminist approaches to violence prevention point to the importance of also targeting factors beyond the individual to address root causes of ADV. In particular, a growing body of literature demonstrates the connection between certain masculine role norms (e.g., avoidance of femininity, emotional restriction) and violence perpetration, including in adolescent dating relationships [[8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]]. For example, in a sample of over 1600 male high school athletes, McCauley and colleagues [8] showed that boys who held more gender-equitable attitudes were significantly less likely to report perpetration of both physical-sexual and emotional ADV. Adherence to these norms also facilitates the continuation of violence through their impact on men and boy's willingness to serve as bystanders and allies [[15], [16], [17]]. Yet, ADV prevention research in the past decade has almost exclusively focused on gender-neutral approaches – approaches that do not engage with how social gender norms are intertwined with experiences of violence – leading to recent calls for gender-transformative1 violence prevention programming [[18], [19], [20]].

To date, only one such gender-transformative approach to violence prevention has been rigorously evaluated with male-identified youth in North America, Coaching Boys Into Men [21,22]. While this program demonstrated lower ADV perpetration and fewer negative bystander behaviors (e.g., going along with it) at one-year follow-up among participants as compared to controls, it is designed to be implemented in a targeted population (high school athletes, with coaches as facilitators). Further, this program was designed and evaluated within an American context. Thus, Canadian programs that take a universal, gender-transformative approach to ADV prevention are needed.

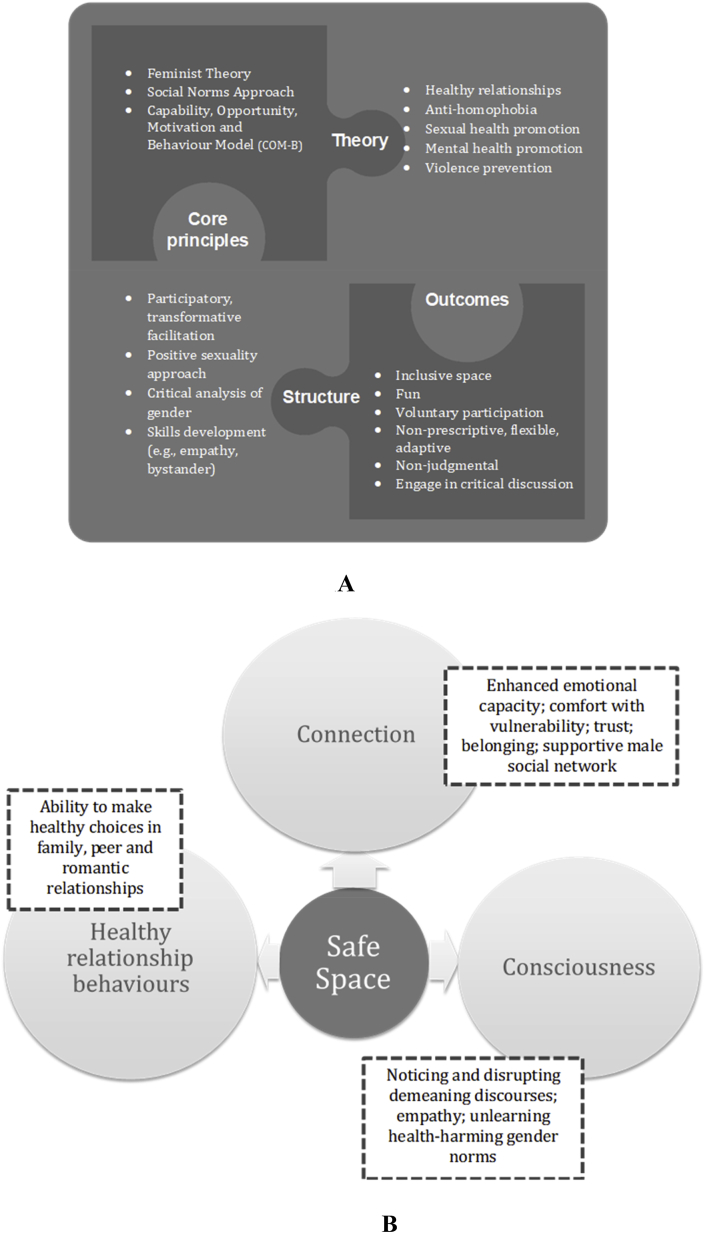

WiseGuyz was designed to fill this gap, and draws on current knowledge about “what works” to prevent ADV [3,19], as well as recommended best practices for violence prevention with young men [[23], [24], [25]]. WiseGuyz is a participatory, gender-transformative healthy relationships promotion program, developed in 2010 by the Centre for Sexuality in Calgary, Alberta (Fig. 1A and B). WiseGuyz strategically targets ninth grade male-identified youth, who are in a pivotal developmental period regarding sexual health and relationships [26]. Past research also demonstrates that mid-adolescence (~ages 13–15) is a key period for starting to deconstruct expectations around social gender norms, and to discuss dating and sexual relationships as part of this deconstruction [18]. During this period, adolescents in Western settings also participate in gender and sexual identity development and prepare to take on adult roles [27,28], and romantic/sexual relationships are increasingly frequent [29].

Fig. 1.

A. WiseGuyz conceptual model. Figure credit, Centre for Sexuality, Calgary, AB.

B. WiseGuyz pilot outcomes summary. Figure credit, Dr. Debb Hurlock.

WiseGuyz is primarily offered in schools, as this environment provides access to a majority of youth and is an important setting for gender role socialization [30]. WiseGuyz is delivered weekly during instructional time and facilitated by a community-based facilitator recruited and trained by the program developers. Each school works with the WiseGuyz team to determine when to offer the program during the school day (e.g., during a health period; during a flex period; alternating each week so students do not miss the same class). Each WiseGuyz session is 75–90 min, and there are 20 sessions total; with holidays, the program typically takes from early October to early June to implement. To promote a culturally safe environment, each group is capped at a maximum of 15 boys (average group size 10–12), and participation is always voluntary. Typically, two groups are run at each participating school. Prior to the start of the standardized curriculum, several weeks are spent creating a safe space and building rapport among participants: in our prior work, we have found that building this safe space at the start of and throughout the program is critical to WiseGuyz’ success [31]. Based on literature identifying the importance of “like-minded” men in prevention programming with male-identified adults and youth [32], all facilitators in this study will be young adult, male-identified individuals.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design and overview

We will explore the effectiveness of WiseGuyz using a longitudinal, quasi-experimental design. This design was chosen because of how recruitment into WiseGuyz occurs (i.e., always voluntary, and so randomizing youth to intervention was not possible at the within-school level). We will survey all ninth grade male-identified youth at each participating school who have parent consent and youth assent, and then create a risk- and demographically-matched comparison group (i.e., comparing youth who took WiseGuyz with those who did not).

The primary objective of this study is to assess whether WiseGuyz participants report increased positive bystander intervention behaviors (primary outcome) at one-year follow-up, as compared to the matched comparison group. A key secondary objective is to assess whether WiseGuyz participants report decreased ADV perpetration (secondary outcome) at one-year follow-up, as compared to the matched comparison group (Table 2). Proposed mediators of behavioral outcomes include attitudes towards male role norms and dating abuse awareness. Proposed moderators of behavioral outcomes include baseline levels of attitudes towards male role norms, masculine discrepancy stress, dating abuse awareness attitudes, sense of school belonging and stressful life experiences. For example, we will explore if dating abuse awareness attitudes at baseline (T1) moderate the association between male role norms at T1 and bystander behavior for violence prevention at follow-up, similar to McCauley and colleagues [8]. To contextualize quantitative survey data, we will conduct focus groups with WiseGuyz participants at each school. All procedures were reviewed and approved by a university research ethics board, and the participating school divisions.

Table 2.

Primary and secondary outcome measures.

| Construct and Measure | Response Options | Data Collection Occasions | Items |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome Measure | |||

| Positive bystander intervention behaviours for violence prevention [36] |

|

T1 T2 T3 |

The following questions ask about specific behaviors that you may have seen or heard among your male peers or friends. If you experienced this at least once in the past 3 months, how did you respond?

|

| Secondary Outcome Measures | |||

| Adolescent dating violence perpetration: Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (CADRI) [41]/Electronic Intrusiveness items [42] | Inclusion question: Have you ever had a dating relationship? A dating relationship is defined as the kind of relationship where you like a person, they like you back, and other people know that you are together. This does not have to mean going on a formal date. [43],p268 Yes No (skip out) Not sure – Response options: ‘never’, ‘once’, and ‘more than once’; dichotomized as any endorsement |

T1 T3 |

Have you done any of the following to a dating partner in the past 6 months? Don't count it if you did it in self-defense.

|

| Positive mental health: Mental Health Continuum – Short Form (MHC-SF) [44] | 6 point Likert scale from ‘Never’ to ‘Everyday’; analyzed as mean score overall and by sub-scale (emotional well-being, psychological well-being, social well-being) | T1 T3 |

The next questions ask about your feelings in the past month. For each statement, please fill in the bubble that describes YOU best. During the past month, how often did you feel … Emotional:

|

| Bullying perpetration: School Climate Bullying Survey – Bullying Behavior Sub-Scale (SCBS-BB) [45] | 4 point Likert scale from ‘never’ to ‘several times per week’; dichotomized as any endorsement overall and by type | T1 T3 |

The next set of questions ask about your experiences with bullying in the last month. For this survey, bullying is defined as the use of one's strength or popularity to injure, threaten or embarrass another person. Bullying can be physical, verbal, social or electronic. It is not bullying when two students who are about the same in strength or power have a fight or argument.

|

| Friendship closeness: Network of Relationships Inventory – Relationship Qualities Version (NRI-RQV) [46] | 5 point Likert scale from ‘never or hardly at all’ to ‘always or extremely much’; analyzed as mean score | T1 T3 |

BEST SAME-SEX FRIEND

|

| Homophobic name-calling: Homophobic Content Agent Scale (HCAT) [47] | 5 point Likert scale from ‘never’ to’ ‘7 or more times’; analyzed as mean score for each target | T1T2 T3 |

Some kids call each other names such as gay, lesbo, fag, etc. How many times in the last week did you say these things to:

|

| Sexual health self-efficacy: Sexual Health-Efficacy Scale (SHSE) [48] | 5-point Likert scale from ‘not at all confident’ to ‘extremely confident; analyzed as mean score | T1 T2 T3 |

Available from scale developer |

| Adherence to male role norms: Male Role Norms Inventory – Adolescent – Revised (MRNI-A-r) [49] | 7-point Likert scale from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’; analyzed as mean score overall and by sub-scale (avoidance of femininity, toughness, emotionally detached dominance) | T1 T2 |

Available from scale developer |

| Adolescent Masculinity Ideology in Relationships Scale (AMIRS) [50] | 7-point Likert scale from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’; analyzed as mean score overall | T1 T2 |

|

| Masculine Discrepancy Stress Scale [51] | 5-point Likert scale from ‘disagree strongly’ to ‘agree strongly’; analyzed as mean score overall | T1 T2 |

|

| Attitudes towards sexual minorities: Negativity Towards Sexual Minorities Scale (NTSM) [52] | 7-point Likert scale from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree; analyzed as mean score | T1 T2 |

Available from scale developer |

| Dating abuse awareness: Dating Abuse Awareness Scale (DAAS) [36] | 5-point Likert scale from ‘not abusive’ to ‘extremely abusive’; analyzed as mean score | T1 T2 |

Below is a list of experiences people might have in a dating relationship. Please rate each of the following actions towards a girlfriend or boyfriend as not abusive, a little abusive, somewhat abusive, very abusive or extremely abusive.

|

| Intentions to intervene with peers [36] | 5-point Likert scale from ‘very unlikely’ to ‘very likely’; analyzed as mean score | T1 T2 |

How likely are YOU to do something to try and stop what's happening if a male friend or peer (someone your age) is:

|

| Help-seeking intentions: General Help Seeking Questionnaire (GHSQ), adapted [53] | 7-point Likert scale from ‘extremely unlikely’ to ‘extremely likely’; analyzed as likelihood to seek help from each source | T1 T2 |

If you were having a personal or emotional problem, how likely is it that you would seek help from the following people?

|

| Drug use intentions: Drug Resistance Self-Efficacy (DRSE) [54] | 5-point Likert scale from ‘disagree strongly’ to ‘agree strongly’; analyzed as mean score | T1 T2 |

I am confident that I can …

|

2.2. Participants

We will recruit 6–700 ninth grade male-identified youth in 9 participating high schools across two cohorts (Cohort 1: Fall 2019; Cohort 2: Fall 2020). Any male-identified youth in ninth grade is welcome to participate, regardless of their involvement with WiseGuyz, and youth do not need to participate in the research to participate in the program. Schools for this project were chosen because they are in our two partner school divisions and willing to offer WiseGuyz and participate in the research project from 2019 to 2022. To recruit schools, the WiseGuyz program manager and research project lead (first author) met with principals at schools within each participating division that had contacted the Centre for Sexuality about offering WiseGuyz in the 2019/20 school year, and informed them about the research project. Participating schools receive a small honorarium ($300) each year as a thank-you for their participation. To honor youth time commitment and support retention, all youth research participants (WiseGuyz and comparison) will receive a $10 gift card at baseline (T1) and post-test (T2), and a $25 gift card at one-year follow-up (T3). At recruitment, we are also collecting contact information (email, cell phone, social media) from all participants to facilitate retention.

2.3. Procedures

We will make presentations on the research project to all ninth grade boys at participating schools in early fall 2019, to recruit both WiseGuyz and comparison group participants. To supplement these presentations, principals at participating schools will send out an email describing the project to the parents/guardians of adolescent boys (along with the electronic consent link); the research team will hold lunchtime snack tables at participating schools to tell boys directly about the project; and the research team will attend school parent nights to tell parents/guardians directly about the project. Interested participants need to provide signed parent/guardian consent (paper or electronic through REDCap) and themselves complete an assent form to participate in the research. To encourage parent consent return (whether or not the youth chooses to participate), all schools where at least 50% of boys return a parent consent (indicating yes or no to the project) will receive a pizza party for all grade 9 classes.

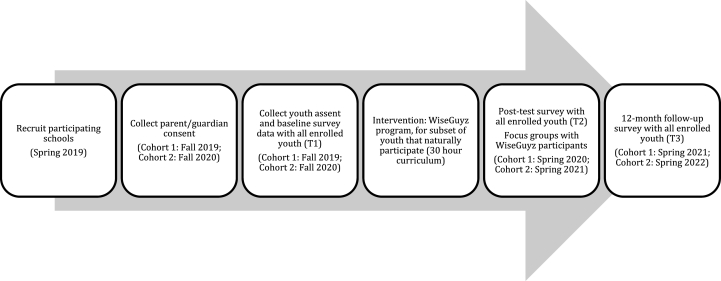

Quantitative data will be collected in two cohorts (Cohort One – T1: October 2019; T2: May 2020; T3: May 2021; Cohort Two – T1: October 2020; T2: May 2021; T3: May 2022; Fig. 2). All surveys will be conducted on computer using REDCap. At T1 and T2, we will go to each school site to collect data, and surveys will be completed during school time on a personal or school computer. We will work with each school to find a time and date that is convenient for them to conduct these surveys, and all surveys will be conducted on or before the third week of WiseGuyz programming at that particular school (as the third week is when content starts). At T3, data will be collected both in- and out-of-school time using email.

Fig. 2.

WiseGuyz outcome evaluation study timeline.

We will gather qualitative focus group data from ~60 WiseGuyz participants immediately post-intervention (Cohort One – May 2020; Cohort Two – May 2021). Based on our past experience conducting WiseGuyz focus groups, each focus group will be capped at five participants, to ensure a safe space for sharing. As such, a selection of those who have parental consent to participate in the focus groups will be selected for participation (parent consent for focus groups is obtained at the same time as parent consent for surveys). Our selection procedures are as follows: 1) facilitators suggest youth who would enjoy participating in a focus group. This judgement is not based on youth engagement levels, but rather youth comfort with sharing in a group setting (as this is required in the focus group). As facilitators know youth very well by this point in the year, they are in the best position to tell us which youth would be most comfortable participating in this type of data collection. In addition, if any youth directly lets their facilitator know they want to participate, their name is added to the list; and 2) of that list, the research team looks at which of those youth have parental consent to participate. If there are more youth on the list than we can accommodate, participation decisions are made by random draw, to promote fairness. Facilitators then let selected youth know the date and time of the focus group, but the focus group is conducted by the research team (i.e., facilitators are not in the room during youth assenting or the conduct of the focus group). During the focus groups, youth will receive pizza and juice as a thank you for participating. The semi-structured focus group guide explores the participant's decision to join WiseGuyz, key learnings and perceived changes (e.g., in understanding of masculinity), and suggested improvements for the program.

2.4. WiseGuyz intervention

WiseGuyz is an integrated and sequential curriculum comprised of four core modules and 20 sessions (Table 1). Sessions are a mix of targeted education, group discussion, and skills development (e.g., role play). Theoretically, the program draws on feminist theory, the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation and Behavior model (COM-B) and a social norms approach (Fig. 1A) [20,[33], [34], [35]]. All WiseGuyz facilitators for this study have implemented the program for at least one year.

Table 1.

Overview of the WiseGuyz curriculum.

| Module Description | Session Breakdown |

|---|---|

| Module 1: Healthy Relationships – This module examines the difference between healthy, unhealthy, and abusive relationships. Participants also learn about personal boundaries, consent, coping skills, empathy and emotional expression, and effective ways to resolve conflict. |

|

| Module 2: Sexual Health – In this module, participants become more aware of healthy sexuality, including changes during puberty and reproductive anatomy. Participants also learn about sexual and reproductive health more broadly, including sexual consent, so that they can identify supports and make informed decisions. |

|

|

|

|

|

2.5. Measures

2.5.1. Primary outcome

Positive (increase) in bystander behavior for violence prevention, measured using the Bystander Intervention Behaviors scale [36] at T1 and T3. This measure assesses both positive (e.g., said something to them in private) and negative (e.g., went along with it) bystander behaviors, and was previously used in the Coaching Boys Into Men evaluation [21,22]. See Table 2 for a full description of this scale.

2.5.2. Secondary outcomes

See Table 2 for a list of secondary outcomes.

2.5.3. Process evaluation

From October 2019–May 2021, we will collect implementation tracking data at the start of the program year, immediately following each WiseGuyz session, at the end of each WiseGuyz module, and at the end of the program year from all facilitators. Youth impressions of the program (e.g., acceptability, utility) will be assessed during the end-of-year focus groups.

2.6. Sample size

Based on our pilot data collection as well as retention in other ADV outcome evaluations, we anticipate an overall consent/assent rate of 50% across the 9 schools (total enrolled n ~ = 600–700). We anticipate that approximately half of these participants will be in the WiseGuyz program, and the other half will serve as our comparison pool. We anticipate an attrition rate of 20% at the one-year follow-up. This final anticipated sample size after attrition (n ~ = 480–560) gives us 80% power to detect an effect size (Cohen's d) of 0.24–0.26 at the α = 0.05 level. In pilot testing, we have observed effect sizes in this range for attitudes, and larger effect sizes for positive bystander behaviors (Cohen's d = 0.39) [37].

2.7. Main analytic plan

We will use 1:1 propensity score matching to create matched comparison and intervention groups [38]. Variables we will explore as part of our propensity score model include baseline (T1) scores on the Male Role Norms Inventory-Adolescent-Revised (MRNI-A-r), Negativity Towards Sexual Minorities (NTSM), Adolescent Masculinity Ideology in Relationships Scale (AMIRS), Dating Abuse Awareness Scale (DAAS), Masculine Discrepancy Stress, and Intentions to Intervene with Peers scales (Table 2), a measure of stressful life experiences (T1); a measure of school belonging (T1); and demographics (race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation and family structure). Because there are typically two WiseGuyz groups at each participating school, we will use multilevel models that account for nesting at both the school and group level (e.g., at School A, participants would be nested into School A-WiseGuyz Group 1; School A-WiseGuyz Group 2; or School A-Comparison). As we have nine schools participating, this will give us ~27 level 2 clusters. We will analyze our nested outcome data using multivariate models including an indicator for treatment group (1 = WiseGuyz; 0 = comparison), and controlling for the baseline level of the outcome variable and the propensity score [38]. We will also explore the data for any cohort effects, and if found, control for cohort, as well. We will conduct attrition analyses to compare those who do and do not complete T2 and T3 surveys, and explore multiple imputation to handle missing data.

Focus groups will be audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. We will code transcripts in Dedoose (a mixed-methods analysis software), using qualitative description methodology [39]. As a member check, themes that arise from coding will be reviewed with WiseGuyz facilitators and the WiseGuyz youth advisory committee prior to finalizing. Using Dedoose, we will also be able to disaggregate codes/themes by key demographic variables of interest (e.g., school). We will integrate quantitative and qualitative data using parallel mixed analysis [40], a method that facilitates triangulation, and is thus appropriate for project goals.

3. Results

We recruited nine high schools in a large, Western Canadian province for this study. High schools are in two school divisions, representing urban, suburban and rural areas. While standard, publicly available demographic information is not collected on Canadian students, census data on median income for included schools is presented in Table 3. Youth recruitment for this project will start in early September 2019.

Table 3.

Geographic Setting and Median Income in Project Schools, in US dollars.

| School Number | Geographic Settinga | Median Individual Income Rangeb |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rural (population < 15,000) | $28,000-$33,000 |

| 2 | Small suburban (population < 40,000) | $35,000-$40,000 |

| 3 | Rural (population < 15,000) | $25,000-$30,000 |

| 4 | Large urban (population > 1,000,000) | $38,000-$43,000 |

| 5 | Medium suburban (population < 100,000) | $37,000-$42,000 |

| 6 | Small suburban (population < 40,000) | $28,000-$33,000 |

| 7 | Small suburban (population < 40,000) | $43,000-$48,000 |

| 8 | Rural (population < 15,000) | $42,000-$47,000 |

| 9 | Small suburban (population < 40,000) | $37,000-$42,000 |

Geographic setting classifications taken from 2016 Canadian Census population centre data.

Income range given to protect school anonymity. The Low Income Cut-off (poverty line) set by Statistics Canada is $17,940 USD per year. Conversion rate to US dollars (USD) was $1 Canadian dollar = $0.77 USD.

4. Conclusions

WiseGuyz is a gender-transformative program designed to prevent ADV, and promote sexual and mental health, among mid-adolescent boys. The described study is an important first step in establishing the evidence base for WiseGuyz, and draws on six years of promising pilot work [26,31,37,55,56]. This will be the first study in Canada to provide evidence on if and how a gender-transformative program for boys impacts positive mental health, violence prevention and sexual health at one-year follow-up, as compared to a matched comparison group. As such, this project has the potential to make a major contribution to evidence-based research and practice with adolescent boys in Canada.

Based on the theoretical underpinnings of the program and anticipated power to detect effects, we chose bystander behavior for violence prevention as our primary outcome. Bystander behavior is an important target for a number of current violence prevention programs [e.g., 21], and is theoretically and empirically linked to reduced ADV perpetration [21,57,58]. The qualitative data we collect will deepen our understanding of potential program impacts (e.g., by allowing us to better understand how WiseGuyz promotes bystander behavior). Limitations of this study include the non-randomized design; the self-report nature of most survey and all process evaluation items; the collection of process evaluation items from facilitators only; and, as all involved school divisions require active consent, anticipated issues with parental consent return. However, despite these limitations, this study will provide critical information on gender-transformative violence prevention with adolescent boys, an area of growing interest and promise for ADV prevention.

Funding

This work was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada [grant number 1819-HQ-000063]. The sponsor had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Declaration of competing interest

The fourth and fifth author's organization is the creator and implementer of the WiseGuyz program. The third author is a consultant with the Centre for Sexuality. The first, second and sixth authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the participating schools and school divisions. Thanks also to Becky Van Tassel, Kerry Coupland, Gary Benthem, Rocio Ramirez Rivera and the WiseGuyz facilitators for their work creating Fig. 1A.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Exner-Cortens D., Eckenrode J., Bunge J., Rothman E. Re-victimization after physical and psychological adolescent dating violence in a matched, national sample of youth. J. Adolesc. Health. 2017;60(2):176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Exner-Cortens D., Eckenrode J., Rothman E. Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):71–78. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfe D.A., Crooks C., Jaffe P. A school-based program to prevent adolescent dating violence: a cluster randomized trial. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2009;163(8):692–699. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levesque D.A., Johnson J.L., Welch C.A., Prochaska J.M., Paiva A.L. Teen dating violence prevention: cluster-randomized trial of teen choices, an online, stage-based program for healthy, nonviolent relationships. Psychol. Violenc. 2016;6:421–432. doi: 10.1037/vio0000049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller E., Chopel A., Jones K., Dick R.N., McCauley H.L., Jetton J., Tancredi D.J. 2015. Integrating Prevention and Intervention: A School Health Center Program to Promote Healthy Relationships.https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/248640.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niolon P., Vivolo-Kantor A., Tracy A. An RCT of Dating Matters: effects on teen dating violence and relationship behaviors. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019;57(1):13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller S., Williams J., Cutbush S., Gibbs D., Clinton-Sherrod M., Jones S. Evaluation of the Start Strong initiative: preventing teen dating violence and promoting healthy relationships among middle school students. J. Adolesc. Health. 2015;56(2):14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCauley H.L., Tancredi D.J., Silverman J.G. Gender-equitable attitudes, bystander behavior, and recent abuse perpetration among heterosexual dating partners of male high school athletes. Am. J. Public Health. 2013;103(10):1882–1887. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poteat V.P., Kimmel M.S., Wilchins R. The moderating effects of support for violence beliefs on masculine norms, aggression, and homophobic behavior during adolescence. J. Res. Adolesc. 2011;21(2):434–447. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reed E., Silverman J.G., Raj A., Decker M.R., Miller E. Male perpetration of teen dating violence: associations with neighborhood violence involvement, gender attitudes, and perceived peer and neighborhood norms. J. Urban Health. 2011;88(2):226–239. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9545-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reidy D.E., Smith-Darden J.P., Cortina K.S., Kernsmith R.M., Kernsmith P.D. Masculine discrepancy stress, teen dating violence, and sexual violence perpetration among adolescent boys. J. Adolesc. Health. 2015;56(6):619–624. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reyes H.L.M., Foshee V.A., Niolon P.H., Reidy D.E., Hall J.E. Gender role attitudes and male adolescent dating violence perpetration: normative beliefs as moderators. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016;45(2):350–360. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0278-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santana M.A., Raj A., Decker M.R., La Marche A., Silverman J.G. Masculine gender roles associated with increased sexual risk and intimate partner violence perpetration among young adult men. J. Urban Health. 2006;83(4):575–585. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9061-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silverman J.G., Decker M.R., Reed E. Social norms and beliefs regarding sexual risk and pregnancy involvement among adolescent males treated for dating violence perpetration. J. Urban Health. 2006;83(4):723–735. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9056-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlson M. I'd rather go along and be considered a man: masculinity and bystander intervention. J. Men's Stud. 2008;16(1):3–17. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casey E.A., Ohler K. Being a positive bystander: male antiviolence allies' experiences of ‘‘Stepping Up’’. J. Interpers Violence. 2012;27(1):62–83. doi: 10.1177/0886260511416479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leone R.M., Parrott D.J., Swartout K.M., Tharp A.T. Masculinity and bystander attitudes: moderating effects of masculine gender role stress. Psychol. Violenc. 2016;6(1):82–90. doi: 10.1037/a0038926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller E. Reclaiming gender and power in sexual violence prevention in adolescence. Violence Against Women. 2018;24(15):1785–1793. doi: 10.1177/1077801217753323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Status of Women Canada . 2017. Strategy to Prevent and Address Gender-Based Violence.http://www.swc-cfc.gc.ca/violence/strategy-strategie/index-en.html [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brush L.D., Miller E. Trouble in paradigm: “Gender transformative” programming in violence prevention. Violence Against Women. 2019;25(14):1635–1656. doi: 10.1177/1077801219872551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller E., Tancredi D.J., McCauley H.L. “Coaching boys into men”: a cluster-randomized controlled trial of a dating violence prevention program. J. Adolesc. Health. 2012;51(5):431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller E., Tancredi D.J., McCauley H.L. One-year follow-up of a coach-delivered dating violence prevention program: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013;45(1):108–112. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peacock D., Barker G. Working with men and boys to prevent gender-based violence: principles, lessons learned, and ways forward. Men Masculinities. 2014;17(5):578–599. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berkowitz A.D. VAWnet; Harrisburg, PA: 2004. Working with Men to Prevent Violence against Women: an Overview (Part One) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crooks C.V., Goodall G.R., Hughes R., Jaffe P.G., Baker L. Engaging men and boys in preventing violence against women: applying a cognitive-behavioral model. Men Masculinities. 2007;13(3):217–239. doi: 10.1177/1077801206297336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Exner-Cortens D, Hurlock D, Wright A, Carter R, Krause, P. Preliminary Evaluation of a Gender-Transformative Healthy Relationships Program for Adolescent Boys [published Online Ahead of Print January 31, 2019]. Psychol Men Masculin. doi:10.1037/men0000204.

- 27.Galambos N.L. Gender and gender role development in adolescence. In: Lerner R.M., Steinberg L., editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. second ed. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2004. pp. 233–262. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill J.P., Lynch M.E. The intensification of gender-role related expectations during early adolescence. In: Brooks-Gunn J., Petersen A., editors. Girls at Puberty: Biological and Psychosocial Perspectives. Plenum; New York, NY: 1983. pp. 201–228. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meier A., Allen G. Romantic relationships from adolescence to young adulthood: evidence from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Sociol. Quart. 2009;50(2):308–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2009.01142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Connell R.W. Teaching the boys: new research on masculinity, and gender strategies for schools. Teachers Coll. 1996;98(2):206–235. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hurlock D. Boys returning to themselves: healthy masculinities and adolescent boys (WiseGuyz research report #3) 2016. https://www.centreforsexuality.ca/programs-workshops/wiseguyz/

- 32.Exner-Cortens D, Cummings N. Bystander-based sexual violence prevention with college athletes: a pilot randomized trial [published online ahead of print September 1, 2017]. J. Interpers Violence. doi:10.1177/0886260517733279. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Michie S., van Stralen M.M., West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterizing and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011;6:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berkowitz A. An overview of the social norms approach. In: Lederman L.C., Stewart L.P., editors. Changing the Culture of College Drinking: A Socially Situated Health Communication Campaign. Hampton Press INC; Cresskill, NJ: 2005. pp. 193–214. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berkowitz A., Jaffe P., Peacock D., Rosenbluth B., Sousa C. 2003. Young Men as Allies in Preventing Violence and Abuse: Building Effective Partnerships with Schools.http://www.alanberkowitz.com/articles/BPIFinal.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abebe K., Jones K., Culyba A. Engendering healthy masculinities to prevent sexual violence: rationale for and design of the Manhood 2.0 trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2018;71:18–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Exner-Cortens D., Hurlock D., Krause P. Poster Presented at the 26th Society for Prevention Research Annual Meeting. 2018. Promoting positive bystanding behavior among adolescent boys: pilot findings from the WiseGuyz study. Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stuart E.A. Matching methods for causal inference: a review and a look forward. Stat. Sci. 2010;25(1):1–21. doi: 10.1214/09-STS313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res. Nurs. Health. 2000;23(4):334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Onwuegbuzie A.J., Teddlie C. A framework for analyzing data in mixed methods research. In: Tashakkori A., Teddlie C., editors. Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research. SAGE Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2003. pp. 351–384. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolfe D.A., Scott K., Reitzel-Jaffe D., Wekerle C., Grasley C., Straatman A. Development and validation of the conflict in adolescent dating relationships inventory. Psychol. Assess. 2001;13(2):277–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reed L.A., Tolman R.M., Safyer P. Too close for comfort: attachment insecurity and electronic intrusion in college students' dating relationships. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015;50:431–438. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giordano P.C., Longmore M.A., Manning W.D. Gender and the meanings of adolescent romantic relationships: a focus on boys. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2006;71:260–287. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keyes C.L.M. Mental health in adolescence: is America's youth flourishing? Am. J. Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76(3):395–402. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cornell D. 2017. Research Summary for the Authoritative School Climate Survey.https://curry.virginia.edu/uploads/resourceLibrary/Authoritative_School_Climate_Survey_Research_Summary_7-11-17.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buhrmester D., Furman W. University of Texas at Dallas; 2008. The Network of Relationships Inventory: Relationship Qualities Version. Unpublished Measure. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Poteat V.P., Espelage D.L. Exploring the relation between bullying and homophobic verbal content: the Homophobic Content Agent Target (HCAT) scale. Violence Vict. 2005;20:513–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koch P.B., Colaco C., Porter A.W. Sexual health practices self-efficacy scale. In: Fisher T.D., Davis C.M., Yarber W.L., editors. Handbook of Sexuality-Related Measures. third ed. Routledge; New York, NY: 2011. pp. 345–347. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levant R.F., Rogers B.K., Cruickshank B. Exploratory factor analysis and construct validity of the male role norms inventory-adolescent-revised (MRNI-A-r) Psychol. Men Masculinity. 2012;13(4):354–366. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chu J.Y., Porche M.V., Tolman D.L. The adolescent masculinity Ideology in relationships scale. Men Masculinities. 2005;8(1):93–115. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reidy D.E., Brookmeyer K.A., Gentile B., Berke D.S., Zeichner A. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2016;45:459–465. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0413-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levant R.F., Rankin T.J., Williams C.M., Hasan N.T. Evaluation of the factor structure and construct validity of scores on the Male Role Norms Inventory-Revised (MRNI-R) Psychol. Men Masculinity. 2010;11(1):25–37. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson C.J., Deane F.P., Ciarrochi J., Rickwood D. Measuring help-seeking intentions: properties of the general help-seeking questionnaire. Can. J. Couns. 2005;39(1):15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Institute of Behavioral Research . Texas Christian University, Institute of Behavioral Research; 2006. TCU Adolescent Thinking Form B (TCU ADOL THKForm B). Fort Worth. ibr.tcu.edu. Published. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Claussen C. The WiseGuyz Program: sexual health education as a pathway to supporting changes in endorsement of traditional masculinity ideologies. J. Men's Stud. 2016;25(2):150–167. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Claussen C. Sex Educ-Sex Soc; 2018. Men Engaging Boys in Healthy Masculinity through School-Based Sexual Health Education. published online ahead of print August 10. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coker A.L., Bush H.M., Cook-Craig P.G. RCT testing bystander effectiveness to reduce violence. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017;52(5):566–578. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Edwards K.M., Baynard V.L., Sessarego S.N., Waterman E.A., Mitchell K.J., Chang H. Evaluation of a bystander-focused interpersonal violence prevention program with high school students. Prev. Sci. 2019;20(4):488–498. doi: 10.1007/s11121-019-01000-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]