Abstract

Background

Coronary artery ectasia (CAE) is an uncommon finding in patients undergoing coronary angiography and acute myocardial infarction is an extremely uncommon condition in the presence of coronary artery ectasia. To date, 50 gene variants associated with coronary artery disease have been identified, but none appear to be related to coronary artery ectasia.

Case presentation

This is a rare case of Coronary artery ectasia which is considered to be related to Gene variations in potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily H member 1, KCNH1 (encoding a protein designated ether à go-go, EAG1 or KV10.1).

Conclusion

Occurrence of Acute myocardial infarction in patient with coronary artery ectasia after diarrhea is a very rare condition and involvement of KCNH1 gene mutation which is described in this case report.

Keywords: Coronary artery ectasia, Acute myocardial infarction, KCNH1, Gene mutation, Diarrhea, Embolism

Background

Coronary artery ectasia (CAE) is defined as dilation of the coronary vascular lumen up to a diameter 1.5 times that of the adjacent normal coronary artery [1, 2]. Angina pectoris is the most common clinical manifestation [3] while acute myocardial infarction is an extremely uncommon condition in the presence of coronary artery ectasia, detected only in < 1% cases [4]. Genetic variation has been reported as one of the risk factors for coronary artery disease. To date, 50 gene variants associated with coronary artery disease have been identified [5], but none appear to be related to coronary artery ectasia.

Here, we have reported a rare case of acute myocardial infarction with coronary artery ectasia and mutation in potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily H member 1, KCNH1 (encoding a protein designated ether à go-go, EAG1 or KV10.1) gene.

Case presentation

A 33-years-old male was admitted into our hospital after 3 hrs of intermittent chest pain. Previously, the patient was admitted to our hospital and diagnosed with first-degree atrioventricular conduct block and coronary artery ectasia, which was conservatively treated with aspirin (100 mg/qd, atorvastatin 20 mg/qd) on a routine basis. After 7–8 episodes of diarrhea, the patient experiences a similar chest pain to previous episodes. Electrocardiography (ECG) was performed immediately, which disclosed ST elevation in inferior leads (II, III and avF). The patient was defibrillated after developing a sudden ventricular fibrillation.

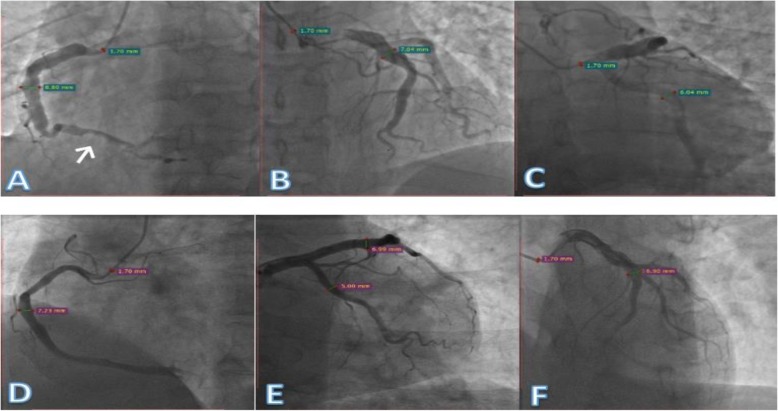

On admission, his pulse was recorded as 72/min and blood pressure (BP) as 120/70 mmHg. In laboratory examinations, cardiac enzyme contents were as follows: creatine kinase (CK)413 IU/L, high-sensitivity troponin I (hs-TnI) 3.303 μg/L, creatine kinase muscle/brain mass (CK-MBmass) 36.94 μg/L. The consequent diagnosis was acute ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The patient underwent elective coronary angiography, which revealed normal left main coronary artery (LMCA), left anterior descending (LAD) middle segment light stenosis with aneurysm-like ectasia and aneurysm-like ectasia of proximal left circumflex artery (LCX), as well as aneurysm-like ectasia of middle segment and thrombus in the distal segment of right coronary artery (RCA) (Fig. 1a-c).

Fig. 1.

a: Left anterior oblique view of ectatic right coronary artery with diameter of 8.80 mm and thrombus in the distal portion of RCA (arrow). b, c: Ectasia of left anterior descending artery and left circumflex artery with diameter of 7.04 and 6.04 (respectively), in the right cranial and caudal views. d: Ectasia in mid to distal segment of RCA with diameter of 7.23 mm. E, F: Ectasia in proximal to mid segment of LAD with diameter of 6.99 mm

Despite angiographic detection of a thrombus, conservative therapy (aspirin 100 mg/qd, ticagrelor 90 mg/tid, atorvastatin 20 mg/qd) appeared the optimal treatment choice. For further examination of cardiac function, echocardiography was performed, which revealed right and left ventricle regional wall motion abnormalities, left ventricle diameter of 55 mm, and left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) of 56%.

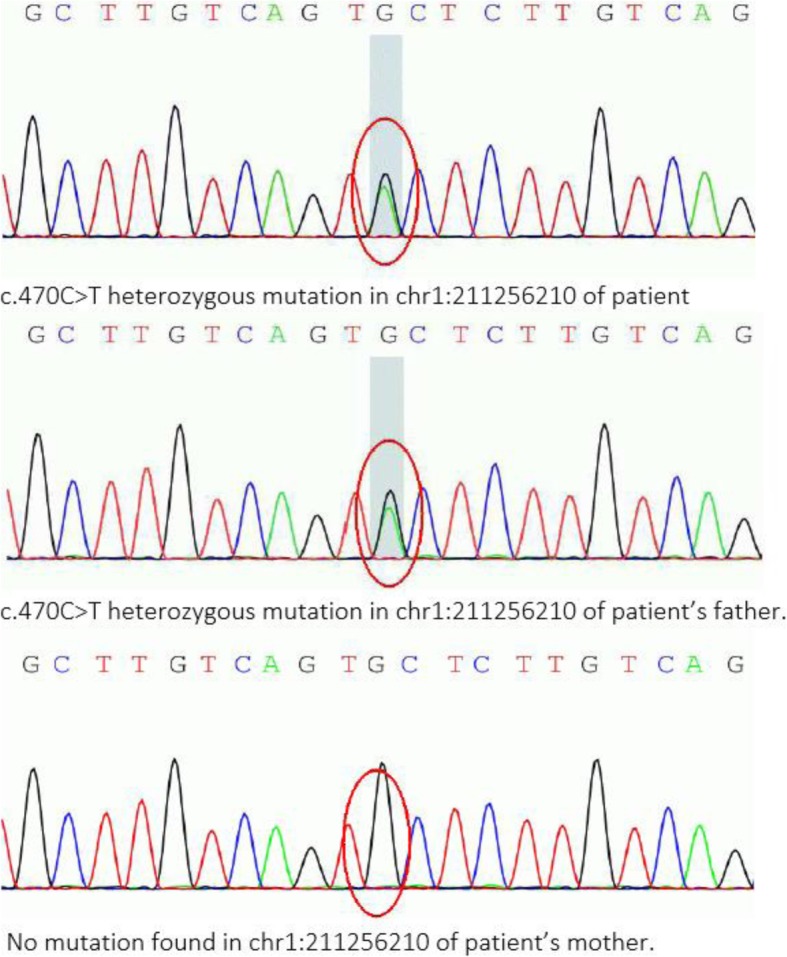

During history taking, the patient provided information on the medical history of his father who was admitted to another hospital due to a similar complaint of chest discomfort and underwent coronary angiography, which showed ectasia of the middle to distal segment of RCA and mid segment of LAD and normal LMCA, LCX (Fig. 1d-f). For analysis of the genetic relationships, high throughput sequencing testing was conducted, as depicted in (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Pyrosequencing profiles of three genotypes of the c.470C > T (chr1:211256210) KCNH1 mutation were identified. The patient and his father carried the same genetic mutation but not his mother. Genetic mutational analysis was performed using www.precisionmdx.com

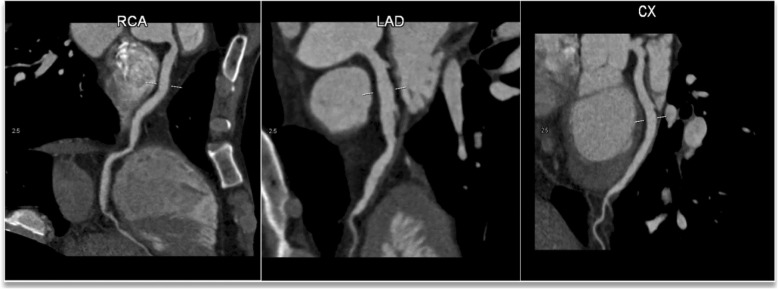

After 1 year of conservative therapy, the patient was re-admitted to our hospital due to short episodes of chest pain, which usually ended within a few seconds. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) revealed normal LMT, slight calcification and ectasia of LAD, LCX, and RCA (Fig. 3). Rivaroxaban 10 mg Qd was selected for anticoagulant therapy, along with atorvastatin 20 mg/qd.

Fig. 3.

Right coronary artery with a diameter of 8.80 mm, left anterior descending artery with a diameter of 7.04 mm, left circumflex artery with a diameter of 6.04 mm

Discussion

CAE is only observed in 5% patients undergoing coronary angiography. Overall, ~ 20–30% CAE cases are congenital, with the remainder being acquired, and up to 20% acquired CAE is attributed to atherosclerosis, which is mostly associated with obstructive coronary artery disease [6]. Congenital CAE is mainly linked to cardiac anomalies, such as bicuspid aortic valve, aortic root dilation, ventricular septal defect or pulmonary stenosis [6, 7]. Acquired CAE association with inflammatory or connective tissue disorder constitutes only 10–20% cases, such as scleroderma Elhers-Danlos syndrome, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-related vasculitis syphilitic aortitis and Kawasaki disease [8]. All the above etiologies of coronary artery ectasia were excluded based on patient history and serological test findings.

Disturbances in blood flow filling and washout are an inherent characteristic of CAE [9]. which may be the basis of ischemia or ischemic events in this patient group, and can alter the incidence of exercise-induced angina pectoris or myocardial infarction regardless of the severity of coexisting stenotic lesions. Slow blood flow to ectatic segments of coronary artery is reported to induce activation of platelets, coagulation and thrombus formation [10].

Before admission to the hospital, the patient experienced several episodes of diarrhea, which could cause dehydration (loss of body fluid), leading to higher concentrations of chemicals circulating in blood and increased serum osmolality, culminating in ectatic artery and consequent disturbance in blood flow, in turn, triggering formation of thrombus in the right coronary artery. After a year of follow-up, coronary CT angiography confirmed absence of thrombus in RCA. Accordingly, anticoagulant therapy with rivaroxaban 10 mg alone was selected for treatment.

KCNH1 (encoding ether à go-go, EAG1 or KV10.1), a voltage-gated potassium channel, is predominantly expressed in the central nervous system (CNS) [11].and its overexpression provides growth advantages to cancer cells and enhances proliferation. Mutations in the KCNH1 gene are reported to be associated with Zimmerman-Laband syndrome and Temple-Baraitser syndrome, characterized by intellectual disability, epilepsy, hypoplasia abnormal muscle tone and craniofacial dysmorphology [12]. Epilepsy is the main manifestation of KCNH1 mutation-induced disorders. However, our patient had none of the above features or epileptic history.

To our knowledge, this is the first documented report linking KCNH1 mutation to coronary heart disease. The detection of mutations in both family members suggests that KCNH1 abnormalities are significantly involved in this condition. Further studies focusing on the KCNH1 gene and the mechanisms underlying its specific association with coronary artery disease are thus warranted.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Tong Tao, Cath-lab technician in the Department of.

Coronary Heart disease for the high-quality images in this case.

Abbreviation

- BP

Blood pressure

- CAE

Coronary artery ectasia

- CK

Creatine kinase

- CK-MBmass

Creatine kinase muscle/brain mass

- CNS

Central nervous system

- CTA

Computed tomography angiography

- ECG

Electrocardiography

- hs-TnI

High-sensitivity troponin I

- KCNH1

Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily H member 1

- LAD

Left anterior descending

- LCX

Left circumflex artery

- LMCA

Left Main coronary artery

- LVEF

Left ventricle ejection fraction

- RCA

Right coronary artery

- STEMI

ST elevation myocardial infarction

Authors’ contributions

NMR wrote the manuscript. LPF collected all the relevant materials including the figures and medical records. BZ performed Percutaneous Coronary Angiography. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written consent for publication was obtained from the patient in this case study.

Competing interests

None.

Footnotes

All authors confirmed that this manuscript has not been previously published and is not currently under consideration by any other journal. Additionally, all of the authors have approved the contents of this paper and have agreed to the policies.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mohammad Rafi Noori, Email: noorirafi1@gmail.com.

Bo Zhang, Email: dalianzhangbo@yahoo.com.

Lifei Pan, Email: 393674598@qq.com.

References

- 1.Morrad B, Yazici HU, Aydar Y, Ovali C, Nadir A. Role of gender in types and frequency of coronary artery aneurysm and ectasia. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4395. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devabhaktuni S, Mercedes A, Diep J, Ahsan C. Coronary artery Ectasia-a review of current literature. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2016;12:318–323. doi: 10.2174/1573403X12666160504100159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin C-T, Chen C-W, Lin T-K, Lin C-L. Coronary artery ectasia. Tzu Chi Med J. 2008;20:270–274. doi: 10.1016/S1016-3190(08)60049-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen C-H, Lin C-T, Lin T-K. Coronary artery ectasia presenting with recurrent inferior wall myocardial infarction. Tzu Chi Med J. 2010;22:119–122. doi: 10.1016/S1016-3190(10)60053-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts R. Genetics of coronary artery disease: an update. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2014;10:7–12. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-10-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markis JE, Joffe CD, Cohn PF, Feen DJ, Herman MV, Gorlin R. Clinical significance of coronary arterial ectasia. Am J Cardiol. 1976;37:217–222. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90315-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aboeata AS, Sontineni SP, Alla VM, Esterbrooks DJ. Coronary artery ectasia: current concepts and interventions. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2012;4:300–310. doi: 10.2741/e377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gunduz H, Demirtas S, Vatan MB, Cakar MA, Akdemir R. Two cases of multivessel coronary artery ectasias resulting in acute inferior myocardial infarction. Korean Circ J. 2012;42:434–436. doi: 10.4070/kcj.2012.42.6.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manginas A, Cokkinos DV. Coronary artery ectasias: imaging, functional assessment and clinical implications. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1026–1031. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eitan A, Roguin A. Coronary artery ectasia: new insights into pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Coron Artery Dis. 2016;27:420–428. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yellen G. The voltage-gated potassium channels and their relatives. Nature. 2002;419:35–42. doi: 10.1038/nature00978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukai R, Saitsu H, Tsurusaki Y, Sakai Y, Haginoya K, Takahashi K, Hubshman MW, Okamoto N, Nakashima M, Tanaka F, Miyake N, Matsumoto N. De novo KCNH1 mutations in four patients with syndromic developmental delay, hypotonia and seizures. J Hum Genet. 2016;61:381–387. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2016.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.