Abstract

Background

Proteins encoded by Suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) genes have critical roles in the regulation of immune responses. Meanwhile, several lines of evidence support the presence of immune dysfunction in bipolar disorder (BD) patients.

Methods

In the present study, we assessed expression levels of SOCS1–3 and SOCS5 genes in peripheral blood of patients with BD and healthy subjects.

Results

All SOCS genes were up-regulated in patients compared with healthy subjects. However, when comparing patients with sex-matched controls, the significant differences were observed only in the male subjects except for SOCS5 which was up-regulated in both male and female patients compared with the corresponding control subjects. Significant pairwise correlations were found between expression levels of genes in both patients and controls. Based on the area under curve values, SOCS5 had the best performance in the differentiation of disease status in study participants (AUC = 0.92). Combination of four genes increased the specificity of tests and resulted in diagnostic power of 0.93.

Conclusion

Taken together, these data suggest a role for SOCS genes in the pathogenesis of BD especially in the male subjects. Moreover, peripheral expression levels of SOCS genes might be used as a subsection of a panel of diagnostic biomarkers in BD.

Keywords: Suppressors of cytokine signaling, Bipolar disease, Expression

Background

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a serious and insistent psychiatric disorder resulting in substantial morbidity and mortality. Among several theories for describing the principal patho-etiology of this disorder, immune dysfunction has extensively attained attention of researchers [1]. Comorbidity of BD with inflammatory diseases, dysregulation of cytokine levels in both peripheral blood and central nervous system (CNS) of patients and relapsing-remitting nature of disease are some clues that pointed out the significance of immune responses in the pathogenesis of BD [1]. Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor type 1 (sTNF-R1) are among cytokines whose levels have been consistently higher in manic patients compared with both healthy individuals and euthymic patients [2].

Suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins are the crucial negative regulators of immune responses that exert their effects through inhibiting the Jak/Stat signaling pathway [3]. Eight members of this family have been identified in human among them are SOCS1 and SOCS3 which alter immune responses in microglia/monocytes and astrocytes as well [4]. These two members of SOCS family are also involved in the TNF-α mediated function and signaling pathways [5, 6]. The role of SOCS genes in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases has been emphasized by the observed down-regulation of SOCS1 and SOCS5 genes in peripheral blood of multiple sclerosis (MS) patients [7]. However, we have recently assessed expression of SOCS genes in the peripheral blood of autistic patients and found no remarkable difference in their expression levels between patients and controls [8]. Based on the role of SOCS proteins in the regulation of immune responses and the observed dysregulation of immune system in BD, we hypothesized that expression of these genes are dysregulated in patients with BD. Consequently, in the present project, we examined expression levels of these genes in peripheral blood of BD patients to unravel if their transcript levels are different between patients and controls and whether they can be used as diagnostic biomarkers to differentiate BD from healthy status.

Methods

Study participants

Five milliliters of peripheral blood samples were collected from 50 bipolar patients and 50 healthy subjects. Patients were assessed based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5) [9]. Control subjects had no past history of psychiatric or neurodegenerative diseases, mental retardation, cancer or infection. They were non-smokers and were not on any medication. All patients were under treatment with Carbamazepine and were in euthymia phase. None of patients were smokers. The study protocol was approved by ethical committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences. Written consent forms were obtained from all study participants.

Expression analysis

RNA was extracted from blood samples using Hybrid-R Blood RNA (GeneAll Biotech, Korea). Afterwards, cDNA was made from RNA samples using PrimeScript 1st strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Clontech, Japan). Relative expression of SOCS genes were quantified in Rotor Gene 6000 real-time PCR system using the primer and probes listed in Table 1 and the RealQ Plus Master Mix (Ampliqon, Denmark). The HPRT1 gene was used as reference gene. As this gene is located on X chromosome, the data of males and females were analyzed separately.

Table 1.

Nucleotide sequences of primers and probes used for expression analysis

| Gene name | Primer and probe sequence | Primer and probe length | Product length |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPRT1 | F: AGCCTAAGATGAGAGTTC | 18 | 88 |

| R: CACAGAACTAGAACATTGATA | 21 | ||

| FAM -CATCTGGAGTCCTATTGACATCGC- TAMRA | 24 | ||

| SOCS1 | F: TGGCCCCTTCTGTAGGATGG | 20 | 109 |

| R: GGAGGAGGAAGAGGAGGAAGG | 21 | ||

| FAM- TGGCCCCTTCTGTAGGATGG- TAMRA | 20 | ||

| SOCS2 | F: ACGCGAACCCTTCTCTGACC | 20 | 99 |

| R: CATTCCCGGAGGGCTCAAGG | 20 | ||

| FAM -CTCGGGCGGCCACCTGTCTTTGC-TAMRA | 23 | ||

| SOCS3 | F: GTGGAGAGGCTGAGGGACTC | 20 | 111 |

| R: GGCTGACATTCCCAGTGCTC | 20 | ||

| FAM- CACCAAGCCAGCCCACAGCCAGG- TAMRA | 23 | ||

| SOCS5 | F: GTGACTCGGAAGAGGATACAACC | 23 | 91 |

| R: CTAACATGGGTATGGCTGTCTCC | 23 | ||

| FAM- CGCTGCTTCTGCCTCCGTGACTGC- TAMRA | 24 |

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were performed in the SPSS 22.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) and MedCalc statistical software. Expression levels of SOCS genes were compared between BD patients and normal controls using independent T test. The correlation between gene expression and demographic data of patients were assessed using regression model. Partial correlation was used to assess the strength and direction of a linear relationship between genes expressions and clinical variables (age, age at disease onset and disease duration) while controlling for the effect of gender. P < 0.05 was regarded as significant. The diagnostic power of transcript levels of SOCS genes was described by measuring the area under curve (AUC) in the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Sensitivity and specificity values were also calculated. The study power (1- β) was calculated by using Stata tool (StataCorp 2017. Stata statistical software Release 15, College station, Texas: StataCorp LLC).

Results

General information about study participants

Table 2 shows general demographic and clinical information of study participants.

Table 2.

General information of study participants

| Study groups | Parameters | Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Gender | Male | 35 |

| Female | 15 | ||

| Age (mean ± SD (range)) | 36.5 ± 9.32 (17–56) | ||

| Age at onset (mean ± SD (range)) | 32.64 ± 8.04 (15–48) | ||

| Disease duration (mean ± SD (range)) | 3.86 ± 2.66 (1–14) | ||

| Control | Gender | Male | 35 |

| Female | 15 | ||

| Age (mean ± SD (range)) | 33.62 ± 8.59 (14–52) | ||

Expression analysis

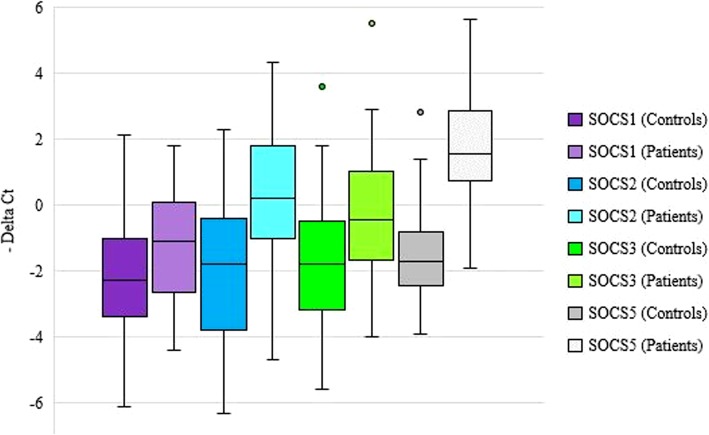

The power of the study (1- β) was calculated to be 82% by using Stata tool considering the mean values of SOCS1 gene expression in cases and controls (μ1 = 1.07 (±2.02), μ2 = 2.18 (±1.86), α = 0.05). All SOCS genes were up-regulated in BD patients compared with healthy subjects (Fig. 1). As the selected reference gene (HPRT1) is located on X chromosome, the data of males and females were analyzed separately. When comparing patients with sex-matched controls, the significant differences were observed only in male subjects except for SOCS5 which was up-regulated in both male and female patients compared with the corresponding control subjects. Table 3 shows the results of expression analysis.

Fig. 1.

Relative expression of SOCS genes in patients and controls as demonstrated by –delta CT values (CT reference gene- CT target gene)

Table 3.

Relative expression of SOCS genes in BD patients compared with controls

| Genes | Parameters | Total patients vs. total controls (50 vs. 50) | Male patients vs. male controls (35 vs. 35) | Female patients vs. female controls (15 vs. 15) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOCS1 | Expression ratio | 2.07 | 4.43 | 0.61 |

| P-value | 0.005 | < 0.001 | 0.14 | |

| SOCS2 | Expression ratio | 3.85 | 8 | 1.21 |

| P-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.47 | |

| SOCS3 | Expression ratio | 2.7 | 4.82 | 1.19 |

| P-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.61 | |

| SOCS5 | Expression ratio | 5.77 | 8.77 | 3.81 |

| P-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.001 |

Expression levels of genes were not correlated with any of demographic or clinical parameters of study participants after adjustment for gender. Table 4 shows the results of partial correlation analysis between expression levels of genes and clinical data.

Table 4.

Partial correlation analysis between expression levels of genes and clinical data (controlled for gender)

| SOCS1 | SOCS2 | SOCS3 | SOCS5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P value | R | P value | R | P value | R | P value | ||

| Case | Age | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 0.44 |

| Age at onset | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.34 | |

| Disease duration | - 0.05 | 0.35 | - 0.07 | 0.31 | - 0.08 | 0.29 | - 0.1 | 0.24 | |

| Control | Age | - 0.04 | 0.38 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.1 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.33 |

Significant pairwise correlations were found between expression levels of genes in both patients and controls (Table 5).

Table 5.

Pairwise correlation between expression levels of genes (R2 values are shown. *: Correlation is significant at P < 0.05 level, **: Correlation is significant at P < 0.01 level)

| SOCS5 | SOCS3 | SOCS2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOCS1 | Controls | 0.43** | 0.46** | 0.6** |

| Patients | 0.28** | 0. 17* | 0.34** | |

| SOCS2 | Controls | 0.51** | 0.59** | |

| Patients | 0.67** | 0.47** | ||

| SOCS3 | Controls | 0.47** | ||

| Patients | 0.58** | |||

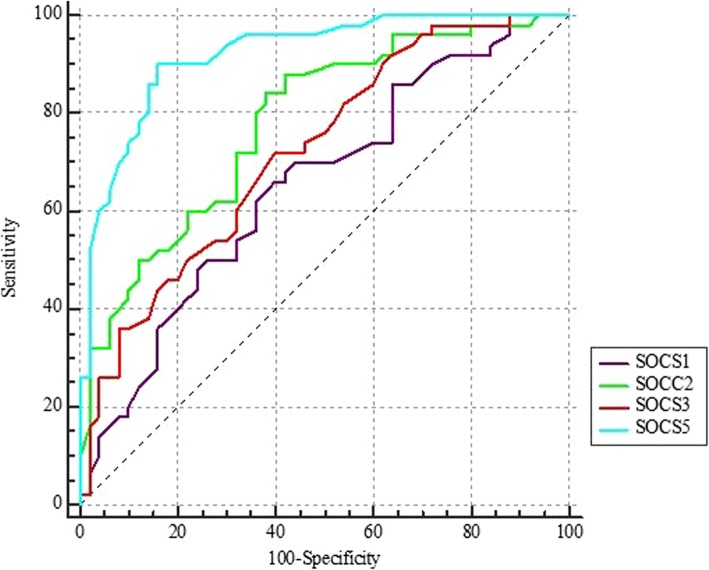

ROC curve analysis

Based on AUC values, SOCS5 had the best performance in differentiation of disease status in study participants (AUC = 0.92). Combination of four genes increased the specificity of tests and resulted in diagnostic power of 0.93. Table 6 and Fig. 2 show the results of ROC curve analysis.

Table 6.

The results of ROC curve analysis (a: Youden index, b: Significance Level P (Area = 0.5), Estimate criterion: optimal cut-off point for gene expression)

| Estimate criterion | AUC | Ja | Sensitivity | Specificity | P-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOCS1 | ≤ 1.5 | 0.65 | 0.26 | 62 | 64 | 0.005 |

| SOCS2 | ≤ 1.3 | 0.78 | 0.46 | 84 | 62 | < 0.0001 |

| SOCS3 | ≤ 1.3 | 0.72 | 0.32 | 72 | 60 | < 0.0001 |

| SOCS5 | ≤ 0.3 | 0.92 | 0.74 | 90 | 84 | < 0.0001 |

| Combination of four genes | > 0.54 | 0.93 | 0.8 | 88 | 92 | < 0.0001 |

Fig. 2.

The results of ROC curve analysis for assessment of diagnostic power of SOCS genes in BD

Discussion

In the current study, we evaluated expression of SOCS genes in the peripheral blood of BD patients. Based on the previously reported interactions between SOCS proteins and sex steroids [10], we performed sex difference analysis as well. We found a sexual dimorphism in up-regulation of SOCS genes except for SOCS5 which was up-regulated in both male and female patients compared with the corresponding control subjects. Although SOCS proteins have been primarily recognized for their anti-inflammatory functions, they might have different functions based on the tissue in which they are expressed. For instance, SOCS3 expression in neurons repressed insulin growth factor-1 (IGF-1)-induced neurite outgrowth [11] and reversed the neuroprotective effect of IGF-1 against TNF-α induced apoptosis [12]. Consistent with these functions, elevated levels of SOCS3 in oligodendrocytes and neurons after traumatic brain damage might exert harmful effects [13]. A previous study has shown decreased neurite mass in neuronal cell cultures being treated with serum of BD patients [14]. Although the underlying mechanism of such in vitro observation is not known, this study indicates the presence of specific peripheral factors that might affect central tissues of BD patients. Patel et al. have previously suggested that temporary or insistent disturbance of blood brain barrier (BBB) integrity would lead to diminished CNS defense and higher permeability of proinflammatory elements from the peripheral blood into the brain. These happenings might be involved in the pathogenesis of BD [15]. Higher levels of SOCS genes expression in peripheral blood of BD patients might affect integrity of BBB or might lead to higher levels of these genes in CNS tissue due to malfunctioned BBB in BD patients. Alternatively, the observed over-expression of SOCS genes in peripheral blood of male BD patients compared with healthy males might reflect higher levels of these genes in central tissues of BD patients as a result of a global event that modulate expression of these genes in whole tissues. On the other hand, such peripheral over-expression of SOCS genes might be a compensatory mechanism to alleviate the detrimental effects of cytokine over-production in BD patients. The latter is supported by the observed role of SOCS1 up-regulation in suppression of TNF-α-mediated cell oxidative stress and apoptosis [6].

Expression of SOCS proteins might also been related with levels of inflammatory markers. For instance, SOCS3 has an inhibitory effect on expression of IL-6 family cytokines [16], but promotes expression of IL-10 [17], an anti-inflammatory cytokine which is increased in serum samples of BD patients [18]. Thus, a future perspective of our work is assessment of the relationship between serum inflammatory markers and SOCS expression in BD patients and also their variations between manic and depressive patients.

SOCS3 is also involved in the evolution of leptin resistance [19]. Both leptin deficiency and leptin resistance might participate in changes in affective status [20]. Consequently, the observed higher levels of SOCS3 in peripheral blood of BD patients might lead to leptin resistance and contribute in the pathogenesis of BD through this axis. In addition, SOCS1 and SOCS3 proteins has been shown to induce insulin [21], a condition that is associated with poor psychiatric outcomes in patients with BD [22].

Expression levels of genes were not correlated with any of demographic or clinical parameters of study participants after adjustment for gender. In our previous study in autistic patients, we found correlation between SOCS5 expression and age of patients, but such correlation was not detected in healthy subjects [8]. However, contrary to the present study, SOCS3 expression levels were significantly correlated with the age of all both patients and controls [8]. Taken together, the correlation between expression of SOCS genes and age not only depends on the disease status but is also determined by the age range. The latter is deduced from the difference in age range of study participants in our previous study versus the current study (children versus adults).

We also detected significant pairwise correlations between expression levels of SOCS genes in both patients and controls which further supports our previous speculation regarding the presence of a single regulatory mechanism for these genes [8].

Conclusion

We reported dysregulation of SOCS genes in BD. We also assessed diagnostic power of SOCS transcripts in BD and found superiority of SOCS5 as over other assessed genes. Notably, expression levels of this gene could differentiate euthymic patients from healthy subject with a diagnostic power of 0.92. Consequently, our data suggest suitability of this gene independence of patients’ signs or symptoms which potentiates it as a subsection of a panel of diagnostic biomarkers in BD in complicated situations such as in forensic medicine. However, future studies are needed to verify our results in larger sample sizes.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank patients for their kind contribution in conducting this study.

Ethics approval and consent to participant

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study protocol was approved by ethical committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (IR.UMSHA.REC.1397.612). Written informed consent form was obtained from all participants above the age of 16 and a parent or guardian for participants under 16 years old.

Abbreviations

- AUC

Area under curve

- BD

Bipolar disorder

- CNS

Central nervous system

- DSM-5

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5

- IGF-1

Insulin growth factor-1

- MS

Multiple sclerosis

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- SOCS

Suppressors of cytokine signaling

- sTNF-R1

Soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor type 1

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-α

Authors’ contributions

MT and MDO made substantial contributions to the conception of the study and supervised the study. MME and AK1 performed the laboratory assessment. VKO and AK2 analysed the data. SGF wrote the manuscript. All authors have approved the final manuscript and have agreed both to be personally accountable for their own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Funding

This study was financially supported for Data collection and designing the study by Grant number 9709275737 by Hamadan University of Medical Sciences.

Availability of data and materials

The analysed data sets generated during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Amir Keshavarzi, Email: drkeshavarzi@yahoo.com.

Mohammad Mahdi Eftekharian, Email: eftekharian@umsha.ac.ir.

Alireza Komaki, Email: komaki@umsha.ac.ir.

Mir Davood Omrani, Email: davood_omrani@yahoo.co.uk.

Vahid Kholghi Oskooei, Email: vahidkholghioskooei@gmail.com.

Mohammad Taheri, Email: mohammad_823@yahoo.com.

Soudeh Ghafouri-Fard, Email: s.ghafourifard@sbmu.ac.ir.

References

- 1.Rosenblat JD, McIntyre RS. Bipolar disorder and immune dysfunction: epidemiological findings. Brain Sci. 2017 Oct;30, 7(11) PubMed PMID: 29084144. Pubmed Central PMCID: 5704151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Munkholm Klaus, Vinberg Maj, Vedel Kessing Lars. Cytokines in bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;144(1-2):16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gisselbrecht S. The CIS/SOCS proteins: a family of cytokine-inducible regulators of signaling. Eur Cytokine Netw 1999 Dec;10(4):463–470. PubMed PMID: 10586112. Epub 1999/12/10. eng. [PubMed]

- 4.Walker D, Whetzel A, Lue L-F. Expression of suppressor of cytokine signaling genes in human elderly and Alzheimer’s disease brains and human microglia. Neurosci. 2015;302:121–137. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.09.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dagvadorj J, Naiki Y, Tumurkhuu G. Shadat Mohammod Noman a, Iftakhar-E-Khuda I, Komatsu T, et al. tumor necrosis factor-α augments lipopolysaccharide-induced suppressor of cytokine signalling 3 (SOCS-3) protein expression by preventing the degradation. Immunol. 2010;129(1):97–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03154.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du C, Yao F, Ren Y, Du Y, Wei J, Wu H, et al SOCS-1 is involved in TNF-alpha-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in renal tubular epithelial cells. Tissue Cell 2017 Oct;49(5):537–544. PubMed PMID: 28732559. Epub 2017/07/25. eng. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Toghi M, Taheri M, Arsang-Jang S, Ohadi M, Mirfakhraie R, Mazdeh M, et al. SOCS gene family expression profile in the blood of multiple sclerosis patients. J Neurol Sci. 2017;375:481–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2017.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eftekharian MM, Omrani MD, Komaki A, Arsang-Jang S, Taheri M, Ghafouri-Fard S. Expression Analysis of Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling (SOCS) Genes in Blood of Autistic Patients. Adv Neuroimmune Biol. (Preprint):1–6.

- 9.Association AP . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®): American psychiatric pub. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newell M-L, Sebitloane M. Immediate or deferred pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: safe options for pregnant and lactating women an open-label randomised control study. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miao T. Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling-3 Suppresses the Ability of Activated Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription-3 to Stimulate Neurite Growth in Rat Primary Sensory Neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26(37):9512–9519. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2160-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yadav Ajay, Kalita Anjana, Dhillon Shivani, Banerjee Kakoli. JAK/STAT3 Pathway Is Involved in Survival of Neurons in Response to Insulin-like Growth Factor and Negatively Regulated by Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling-3. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(36):31830–31840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501316200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emery B., Cate H. S., Marriott M., Merson T., Binder M. D., Snell C., Soo P. Y., Murray S., Croker B., Zhang J.-G., Alexander W. S., Cooper H., Butzkueven H., Kilpatrick T. J. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 limits protection of leukemia inhibitory factor receptor signaling against central demyelination. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103(20):7859–7864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602574103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wollenhaupt-Aguiar B, Pfaffenseller B, Chagas VS, Castro MA, Passos IC, Kauer-Sant'Anna M, et al. Reduced Neurite Density in Neuronal Cell Cultures Exposed to Serum of Patients with Bipolar Disorder. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology. 2016 May 31. PubMed PMID: 27207915. Pubmed Central PMCID: 5091826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Patel Jay P., Frey Benicio N. Disruption in the Blood-Brain Barrier: The Missing Link between Brain and Body Inflammation in Bipolar Disorder? Neural Plasticity. 2015;2015:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2015/708306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Babon Jeffrey J., Varghese Leila N., Nicola Nicos A. Inhibition of IL-6 family cytokines by SOCS3. Seminars in Immunology. 2014;26(1):13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong Q., Fan R., Zhao S., Wang Y. Over-expression of SOCS-3 Gene Promotes IL-10 Production by JEG-3 Trophoblast Cells. Placenta. 2009;30(1):11–14. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunz Mauricio, Ceresér Keila Maria, Goi Pedro Domingues, Fries Gabriel Rodrigo, Teixeira Antonio L., Fernandes Brisa Simões, Belmonte-de-Abreu Paulo Silva, Kauer-Sant'Anna Márcia, Kapczinski Flavio, Gama Clarissa Severino. Serum levels of IL-6, IL-10 and TNF-α in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: differences in pro- and anti-inflammatory balance. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 2011;33(3):268–274. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462011000300010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lubis AR, Widia F, Soegondo S, Setiawati A. The role of SOCS-3 protein in leptin resistance and obesity. Acta Med Indones 2008 Apr;40(2):89–95. PubMed PMID: 18560028. [PubMed]

- 20.Lu Xin-Yun. The leptin hypothesis of depression: a potential link between mood disorders and obesity? Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2007;7(6):648–652. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howard Jane K., Flier Jeffrey S. Attenuation of leptin and insulin signaling by SOCS proteins. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2006;17(9):365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calkin Cynthia V, Alda Martin. Insulin resistance in bipolar disorder: relevance to routine clinical care. Bipolar Disorders. 2015;17(6):683–688. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The analysed data sets generated during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.