Abstract

microRNAs (miRNAs) play important roles in physiologic and pathologic regulation, but their delivery for use in therapeutic applications is challenging. Extracellular vesicles (EVs), which are being explored as drug delivery vehicles, are stable in circulation and contain miRNAs. However, using EVs to deliver miRNAs has been limited by the difficulty of loading miRNAs into EVs. In this study we describe a method to produce miRNA-enriched EVs in large quantities. We show that overexpressing an miRNA precursor in cells enormously increases the specific miRNA content in EVs. Growing cells in bioreactors can generate large quantities of miRNA-enriched EVs that can be concentrated by tangential flow filtration. The EVs thus produced can enter into cells in vitro and can increase circulating miRNA levels in vivo in animal models. These miRNA-enriched EVs may be useful in various in vitro and in vivo applications.

Impact Statement

This article describes a method for producing microRNA (miRNA)-enriched extracellular vesicles in large quantities. It enables in vivo delivery of specific miRNA for therapeutic applications.

Keywords: : extracellular vesicle, microRNA, large-scale production, miRNA-133a-3p, miRNA-202-5p

Introduction

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are heterogeneous membranous vesicles released by various cells through different pathways. EVs include microvesicles, which originate from outward membrane budding, and exosomes, which originate from inward budding of multivesicular bodies and subsequent fusion of the multivesicular body membranes with the plasma membrane.1 Exosomes play important roles in intercellular crosstalk and disease pathogenesis and are believed to function by delivering RNAs, proteins, and lipids.2 There are currently many efforts exploring the usage of EVs, especially exosomes, as drug delivery vehicles.3

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small (18–22 nucleotides in length) RNAs that regulate gene expression through binding to the 3′-untranslated regions of the targeted messenger RNAs (mRNAs) to suppress translation or degrade target mRNAs.4 An miRNA can regulate the expression of enormous numbers of genes.5 EVs contain RNA species such as microRNAs and may mediate intercellular RNA transfer and communication.6 Although miRNAs play pivotal roles in physiologic and pathologic conditions,7–9 their therapeutic application has been hampered by challenges associated with their delivery because they are unstable and cannot enter cells without a vehicle.

EVs are being actively pursued as a method for miRNA delivery. The most common strategy being used is to isolate EVs and then load miRNA into them in vitro by electroporation10–13 or liposomes.14 Another strategy is to transfect synthetic miRNA into cells followed by purifying exosomes from these cells.15,16 Mesenchymal stem cells treated with miRNA-expressing plasmids17 or lentivirus18 have been used to prepare miRNA-enriched EVs to deliver miRNAs to other cells. Although these strategies are incompatible with large-scale preparation of miRNA-enriched EVs, they show that increasing the expression of a specific miRNA in cells also increased the concentration of that miRNA in EVs secreted by the cells.

In this study we describe a method of enabling large-scale preparation of EVs enriched with a specific miRNA, addressing the challenges associated with miRNA delivery in regenerative medicine and other therapeutic applications.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids

Lentiviral vectors expressing unmodified hsa-mir-133a (RmiR6037-MR03), hsa-mir-202 (HmiR0166-MR03), and nontargeting control (CmiR0001-MR03) were purchased from GeneCopoeia, Inc. For expression of miRNAs modified with an exosome sorting motif, the mir-133a and mir-202 precursor sequences were synthesized and inserted into the XMIRXpress cloning lentivector with Xmotif (Cat no. XMIRXP-Vect; System Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Specifically, to enhance miR-133a-3p expression in the exosome, the annealed product of oligos mir-133a-Top (gatccACAATGCTTTGCTAGAGCTGGTAAAATGGAACCAAATCGCCTCTTCAATGGATTTGGTCCCCTTCAACCAGCTGTAGCTATGCATTGAc; human mir-133a precursor sequence are in uppercase, sequences in lowercase are added for subcloning) and mir-133a-Bot (ctaggTCAATGCATAGCTACAGCTGGTTGAAGGGGACCAAATCCATTGAAGAGGCGATTTGGTTCCATTTTACCAGCTCTAGCAAAGCATTGTg) were inserted into the prelinearized XMIRXP-Vect by ligation with T4 DNA ligase.

To enhance miR-202-5p expression in the exosome, the annealed product of oligos mir-202-Top (gatcc AAGAGGTATAGCGCATGGGAAGATGGAGCTGGATCTGGTCTAGTTCCTTTTTCCTATGCATATACTTCTTTGc; human mir-202 precursor sequence are in capital and the two underlined blocks were switched in position according to the manufacturer's protocol, the sequences in lowercase were added for subcloning) and mir-202-Bot (ctagg CAAAGAAGTATATGCATAGGAAAAAGGAACTAGACCAGATCCAGCTCCATCTTCCCATGCGCTATACCTCTTg) were inserted into the prelinearized XMIRXP-Vect by ligation with T4 DNA ligase. A nontargeting control vector was also purchased from System Biosciences. The resulting plasmid DNA was used to produce lentiviral vectors.

Making stable cell lines overexpressing mir-202 and mir-133a

To make the lentiviral vectors for expressing miR-133a and miR-202, 5 × 106 HEK293T cells were seeded in 10 cm dishes in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) 24 h before transfection. Then the lentiviral target vectors described above (RmiR6037-MR03, HmiR0166-MR03, nontargeting control CmiR0001-MR03 from GeneCopoeia, and vectors constructed based on the XMIRXpress cloning lentivector) were cotransfected with psPAX2 and pMD2.G DNA (9, 6, and 3 μg, respectively) into the cells mediated by 54 μL Fugene 6 (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI) according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

To make HEK293 cell lines overexpressing mir-133a, mir-202, and nontargeting controls, the viral vector-containing supernatant was mixed with prewarmed fresh 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) containing DMEM at 1:1, and 2 mL of the mixture was added to 2.5 × 105 HEK293 cells in a well of six-well plates. To enhance transduction, polybrene was added at a final concentration of 6 μg/mL. Twenty-four hours after transduction, the cells were incubated in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 2 μg/mL puromycin for 7 days to kill the cells without viral DNA integration. The puromycin-resistant cells were called HEK293-mir-133a, HEK293-mir-202, HEK293-mir-NT, HEK293-mir-133a-EXO, HEK293-mir-202-EXO, and HEK293-mir-NT-EXO. Cells with “-EXO” labeling indicate cells expressing miRNA modified to enhance miRNA exosome sorting.

High-density cell culture in hollow fiber bioreactor for EV collection

The hollow fiber bioreactor (FiberCell Systems, Inc., New Market, MD), equipped with a cartridge with the molecular cutoff of 20 kDa (no. C2011), was used to culture cells at high density for EV collection. The cartridge was primed sequentially by phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), serum-free DMEM, and DMEM (high glucose) with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, each for 24 h. Then 2 × 108 miRNA-overexpressing HEK293 cells were seeded into the cartridge. The glucose level of the medium was monitored everyday to evaluate cell growth rate, and the medium was changed once the glucose level decreased to half the original level. When the glucose level dropped to 50% within a day (normally 1 week after cell seeding), the medium was changed to DMEM (high glucose) with 10% chemically defined medium for high density cell culture (an FBS replacement). Afterward, EV-containing medium was collected from the cartridge everyday for ∼30 days.

Small-scale EV isolation

The ExoQuick kit (System Biosciences) was used to isolate exosomes from mouse serum or tissue culture supernatant. In brief, 100 μL serum was mixed with 150 μL PBS and 63 μL ExoQuick reagent, and incubated at 4°C for 30 min. Then the mixture was centrifuged at 1500 g for 30 min, and the resulting pellet contained the EVs.

Ultracentrifugation was used to isolate EVs from tissue culture medium following our published procedures.19 In brief, the cell culture medium was centrifuged at 1000 g for 30 min at 4°C to remove cell debris. The supernatant was centrifuged at 120,000 g for 70 min at 4°C. The pellet was washed once with PBS and centrifuged again under the same conditions. The resulting pellet contained the EVs.

Large-scale EV isolation with the tangential flow filtration system

The culture medium from the hollow fiber bioreactor was spun at 4°C at 1000 g for 30 min to remove larger particles and cell debris. The supernatant was then filtered with a 0.85 μm filter (no. 450-0080; ThermoFisher Scientific), concentrated and purified with the KR2i TFF system (Spectrum Labs), using the concentration–diafiltration–concentration mode. Typically, 500–1000 mL supernatant from the hollow fiber bioreactor was concentrated to ∼100 mL, diafiltrated with 500–1000 mL PBS, and finally concentrated to ∼8–4 mL. The hollow fiber filter modules were made from modified polyethersulfone, with a molecular weight cutoff of 500 kDa. The flow rate was 80 mL/min and the pressure limit was 8 psi for the filter module D02-E500-05-N (used to concentrate supernatant from large volumes to ∼8 mL). The flow rate was 10 mL/min and the pressure limit was 5 psi for filter module C02-E500-05-N (used to concentrate supernatant from ∼10 mL to ∼3–4 mL).

miRNA purification and detection

The miRNA was isolated from cells or EVs with the miRNeasy Mini Kit (no. 217004; Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Typically, 50 μL of serum or culture medium from the hollow fiber bioreactor or 5 μL of concentrated EV samples were used for miRNA isolation. About 5–10 ng of total RNA was used for reverse transcription with the TaqMan Advanced miRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit (no. A28007; ThermoFisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. TaqMan advanced miRNA assays for hsa-miR-202-5p, hsa-miR-133-3p, and hsa-miR-16-5p were used together with TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (no. 4444557; ThermoFisher Scientific) to detect miRNA expression by quantitative PCR. The thermal cycle conditions were 95°C for 20 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, and 60°C for 30 s.

Nanoparticle tracking analysis of EVs

Hydrodynamic diameters and concentrations of EVs were measured using the Nanosight NS500 instrument (Malvern Instruments, United Kingdom) using the instrument's software (version NTA3.2). The instrument was primed using PBS, pH 7.4 and the temperature was maintained at 25°C. Accurate particle tracking was verified using 50 and 100 nm polystyrene nanoparticle standards (Malvern Instruments) before examining samples. Purified samples containing EVs were serial diluted 10–40,000-fold in PBS. The linear range for quantification of EV concentration in each sample fell between 10- and 40,000-fold dilutions. Therefore, all samples were diluted 20,000-fold in PBS. Five independent measurements (60 s each) were obtained for each sample in triplicate. Data are reported as the mean (multiplied by dilution factor for concentration determination) of these measurements ± standard error of the mean.

Transmission electron microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy was performed at the Cellular Imaging Shared Resource of Wake Forest Baptist Health Center (Winston-Salem, NC). For negative staining, plain carbon grids were soaked in 20 μL of EV samples and stained with phosphotungstic acid. The samples were dried and observed under an FEI Tecnai G2 30 electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR).

Exosome labeling and uptake into HEK293T cells

An aliquot of frozen EV was resuspended in 1 mL of PBS and labeled with the PKH26 Fluorescent Cell Linker Kits (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, 2 × PKH26-dye solution (4 μL PKH26 dye into 1 mL of Diluent C) was prepared and mixed with 400 μg of EV solution for a final dye concentration of 2 × 10–6 M. The samples were mixed gently for 5 min. Staining was stopped by adding 2 mL of 1% bovine serum albumin to capture excess PKH26 dye. The labeled EVs were transferred into a 100-kDa Vivaspin filter (Sartorius), spun at 4000 g, and then washed with PBS twice.

For EV uptake experiments, HEK293 and NIH3T3 cells were plated in eight-well chamber slides (1 × 104 cells/well) using growth medium. After 24 h, fresh DMEM with 10% exosome-free FBS (200 μL) containing labeled EVs was added to each well and incubated for 1.5 h at 4°C (negative control) or 37°C. After incubation, the slides were washed twice with PBS (500 μL) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 20 min at room temperature. The slides were washed twice with PBS (500 μL) and mounted with mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories). The cells were visualized using an Axioskop microscope (Carl Zeiss). ImageJ was used for quantification of EV absorption signal. First the mean density of a whole image was obtained. Then the minimal and maximal densities of individual cells in that image were measured. These values were normalized by the mean density of the whole image to obtain the relative densities.

Delivery of miRNA-enriched EV to mice by intraperitoneal injection

Female BL6/C57 mice (20 months old, National Institute of Aging) were used in these experiments. An EV suspension (50–400 μg protein) was delivered to mice by intraperitoneal injection and blood was collected 4, 8, 12, and 24 h after injection. EV was purified from the serum by Exoquick (ExoQ20A-1; System Biosciences) and miRNA isolation and detection were performed as described previously.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism software was used for statistical analyses. T-tests were used to compare the averages of two groups. In cases of more than two groups or one factor, analysis of variance was performed followed by Tukey or Bonferroni post hoc tests. p < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Overexpressing miRNA in cells increased its EV compartment

To develop a strategy to prepare large quantities of EVs enriched with a specific miRNA, we prepared HEK293 cell lines stably expressing human mir-133a and mir-202 precursors by the human cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter (HEK293-mir-133a, HEK293-mir-202). We chose these miRNAs because they have relatively narrow tissue expression profiles (mir-133a in muscle20 and mir-202 in reproductive organs21) and because miR-133a-3p and miR-202-5p are detectable in body fluids,22,23 suggesting that they have intrinsic characteristics enabling their secretion through EVs. Recently it was reported that some sequence motifs helped the sorting of miRNAs into exosomes.24,25 Thus in addition to cell lines expressing unmodified miRNA precursors (HEK293-mir-133a, HEK293-mir-202), we also made cell lines expressing mir-133a and mir-202 precursors from the XMIRXpress lentivectors driven by H1 promoters, aiming to enhance the sorting of miR-133a-3p and miR-202-5p into exosomes (HEK293-mir-133a-EXO, HEK293-mir-202-EXO).

In one of the experiments, quantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR showed that in HEK293-mir-133a-EXO cells, cellular mir-133a-5p and mir-133a-3p expression increased by 2394- and 2367-fold, respectively, suggesting that both mature miRNAs could be increased by overexpressing an miRNA precursor. In subsequent experiments, we focused on one mature miRNA from each precursor, which were miR-133a-5p and miR-202-3p. Stable expression of the mir-133a precursor significantly increased miR-133a-5p expression in cells and the EVs, but had little effect on miR-202-3p expression (Table 1). Similarly, stable expression of the mir-202 precursor significantly increased miR-202-3p expression in cells and EVs, but had little effect on miR-133a-5p expression (Table 2). The increase of miR-133a-5p expression is ∼10-fold of that of miR-202-3p, although the expression was controlled by the same promoter. This could be related to intrinsic features of the two miRNAs, such as the processing efficiency and stability.

Table 1.

miR-133a-3p Expression in Cells and Extracellular Vesicles after mir-133a Overexpression

| HEK293-mir-133a (CMV, unmodified) | HEK293-mir-133a-EXO (H1, modified) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular miR-133a-3p | 89,987 ± 15,179 (n = 7) | 1695 ± 336 (n = 7) |

| EV miR-133a-3p | 70,591 (n = 2) | 1645.958 (n = 2) |

| EV/cellular | 0.78 | 0.97 |

| EV miR-202-5p | 5 (n = 1) | 0.3 (n = 1) |

“n” indicates number of experiments. All expression levels are expressed as fold of cells expressing nontargeting controls. For cellular expression, mean ± SEM is listed. For EV expression, only the mean is listed because of the low replicate numbers.

CMV, cytomegalovirus; EV, extracellular vesicle; EXO, exosome; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Table 2.

miR-202-5p Expression in Cells and Extracellular Vesicles after mir-202 Overexpression

| HEK293-mir-202 (CMV, unmodified) | HEK293-mir-202-EXO (H1, modified) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular miR-202-5p | 7681 ± 1409 (n = 7) | 197 ± 35 (n = 7) |

| EV miR-202-5p | 108 (n = 2) | 36 (n = 2) |

| EV/cellular | 0.014 | 0.18 |

| EV miR-133a-3p | 1 (n = 1) | 6 (n = 2) |

“n” indicates number of experiments. All expression levels are expressed as fold of cells expressing nontargeting controls. For cellular expression, mean ± SEM is listed. For EV expression, only the mean is listed because of the low replication numbers.

Adding sequence motif to increase miRNA exosomal secretion greatly helped the exosomal secretion of miR-202-5p (>10-fold different EV/cellular values in Table 2) but did not show evident effect on miR-133-3p (similar EV/cellular values in Table 1). However, as the cellular and EV expression of the miRNAs from CMV promoter-controlled unmodified precursors (HEK293-mir-133a and HEK293-mir-202) were much higher than the H1-controlled modified precursors (HEK293-mir-133a-EXO and HEK293-mir-202-EXO), HEK293-mir-133a and HEK293-mir-202 cells were used in subsequent experiments.

Use of a hollow fiber bioreactor for large-scale preparation of miRNA-enriched EVs

The hollow fiber bioreactor system allows high-density culture of EV-producing cells, and the 20 kDa cutoff of the fiber allows nutrients and waste products to pass through but retains EVs (40–1000 nm in diameter, molecular weight >500 kDa). We grew the HEK293-mir-133a, HEK293-mir-202, and HEK293-mir-NT cells in the system for >30 days, and collected 50 mL of EV-enriched supernatant every 1 or 2 days. We discontinued the cultures only because we collected enough supernatant. Compared with supernatants of conventional 2D cultures, expression of miR-133a-3p and miR-202-5p in the supernatants collected from the bioreactors contained 4.3-fold more miR-133a-3p or miR-202-5p in EVs. We did not compare the copy numbers of miRNA molecules per EV particle. However, we posit that higher EV particle concentrations in the supernatant could be one of the mechanisms of the increased miRNA yields. Thus the bioreactor can be used to prepare miRNA-enriched EVs continuously.

To examine whether the levels of EV miRNA production will decrease during the continued high-density culture, we compared miR-133a-3p levels in EVs of the supernatant collected on days 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30. In a period of 30 days, the relative expression of miR-133a-3p was 1, 1.1, 1.4, 1.5, 1.5, and 1.6 after normalizing by endogenous miR-16-3p, an abundant miRNA in EVs. Thus the miRNA expression was stable for the duration examined.

Concentrating miRNA-enriched EVs with a tangential flow filtration system

Initially, we used the traditional method of ultracentrifugation to concentrate miRNA-enriched EVs, but these proved very difficult to be resuspended even when using serum-free medium. Thus, we used the tangential flow filtration system to concentrate EVs collected from the bioreactor. With this method, we could concentrate the supernatants by 200-fold without forming precipitates. Compared with EV preparations from cells expressing a nontargeting control, miR-133a-3p-enriched EV had ∼10,000 times more miR-133a-3p, and the miR-202-5p-contained EV had >7000 times more miR-202-5p.

Next, we compared the contents of miR-133a-3p, miR-202-5p, and miR-16-3p in the EV samples before and after the concentration process. miR-16-3p is abundant in EVs of many cells and is used as an endogenous control. For miR-133a-3p, miR-202-5p, and miR-16-3p, the values of miRNA concentration factor/EV concentration factor were 0.9 ± 0.2 (n = 3), 1.4 ± 0.14 (n = 2), and 0.8 ± 0.16 (n = 3), respectively. Thus, after processing, concentrations of all examined miRNAs increased in direct proportion to the overall increase in concentration of the EVs. Most miRNAs were recovered during concentration of the EVs, indicating that most were associated with membrane structures or large protein complexes >500 kDa. Thus, tangential flow filtration could effectively concentrate EVs without a significant loss of the specific miRNA-loaded EV population.

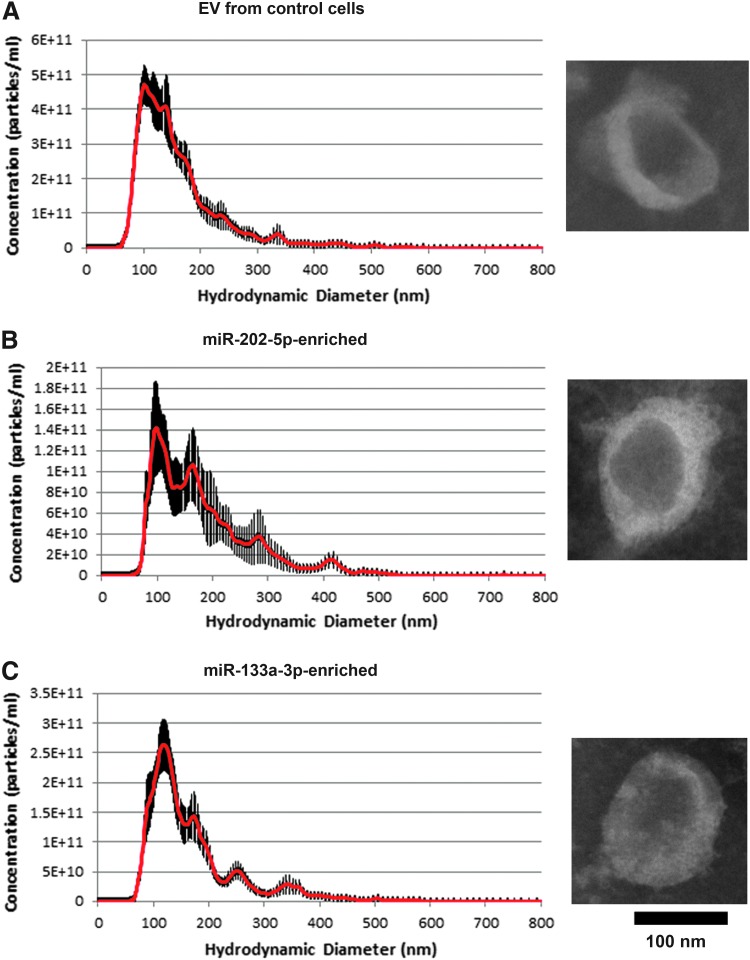

After 200-fold concentration, protein content in the EV preparations was ∼80 mg/mL. Particle concentrations were 2.2 × 1013 ± 1.0 × 1012, 6.9 × 1012 ± 4.1 × 1011, and 8.4 × 1012 ± 2.4 × 1011/mL, and sizes were 138 ± 1.77, 150.8 ± 12.2, and 142.7 ± 4.4 nm for control EVs, miR-202-5p-enriched EVs, and miR-133a-3p-enriched EVs, respectively (Fig. 1). Control EVs, miR-202-5p-enriched EVs, and miR-133a-3p-enriched EVs had similar morphology on electron microscopy (Fig. 1). The sizes of individual EVs were heterogeneous in electron microscopy for all three types of EVs, consistent with the nanoparticle tracking analysis data. We did not attempt to quantitatively compare the size of EVs from electron microscopy because of the EV heterogeneity. miR-133a-3p content in miR-133a-3p-enriched EVs was 37,000-fold of that in mouse plasma, and that of miR-202-5p it was 7 × 105-fold of miR-202-5p in mouse plasma.

FIG. 1.

Size and morphological analyses of concentrated EVs. (A) Concentrated EVs from nontargeting control cells. (B) Concentrated EVs from mir-202 overexpressed cells. (C) Concentrated EVs from mir-133a overexpressed cells. For (A–C), the samples were diluted 20,000-fold for nanoparticle tracking analysis. The left images are nanoparticle tracking analysis of EVs. The right images are electronic microscopy images. The EVs were stained by phosphotungstic acid for electron microscopy analysis. EV, extracellular vesicle.

Systemic delivery of miRNA-enriched EVs increased circulating miRNA levels

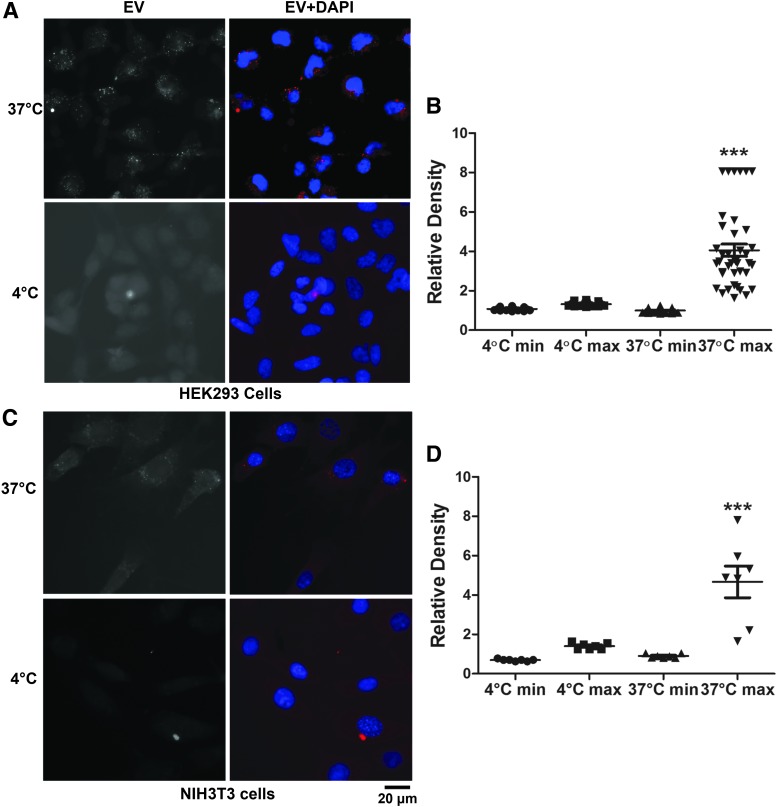

We tested whether the EV preparations can enter HEK293 cells (the cell line from which the EVs were prepared) and NIH3T3 cells (a cell line from a different species). Cells kept at 4°C or 37°C were incubated with PKH26-labeled EVs for 1.5 h before they were processed for fluorescence and observation. Much more fluorescence was observed in cells incubated at 37°C than those at 4°C (Fig. 2A, C), demonstrating that EVs entered into the cells. We compared the density of fluorescence signals by ImageJ. As the signals appeared as tiny bright granules, we measured the minimal and maximal densities in each cell. The average minimal density of cells incubated at 37°C was not different from that at 4°C (Fig. 2B, D), indicating similar level of background. However, the average maximal density of cells incubated at 37°C was significantly higher than that at 4°C. This difference was caused by the absorption of EVs at 37°C.

FIG. 2.

Fluorescence microscopy analysis of EV uptake by cells at different temperatures. (A) Images of HEK293 cells incubated at different temperatures. (B) Quantification of minimal and maximal densities of HEK293 cells. Each point indicates one cell. (C) Images of NIH3T3 cells incubated at different temperatures. (D) Quantification of minimal and maximal densities of NIH3T3 cells. miR133a-3p-enriched EVs were labeled by PKH26 and visualized with excitation of 550 nm. The nuclei were stained by DAPI. The experiments were performed twice. In each experiment, cells on four coverslips (placed in 24-well plates) were treated under a condition. Shown are representative images. ***p < 0.0001 when compared with other groups (Tukey's multiple comparison test after ANOVA). ANOVA, analysis of variance.

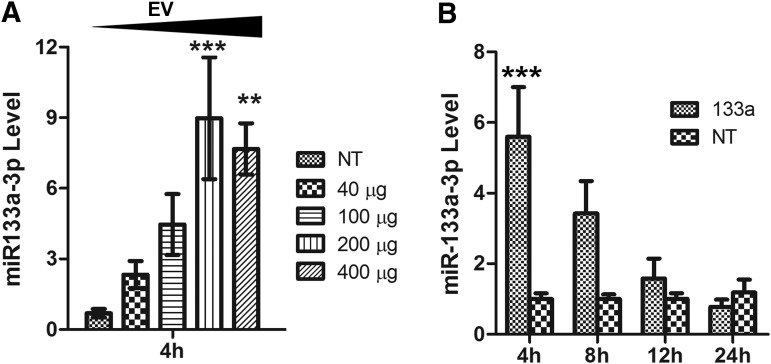

We then examined whether intraperitoneal injections of the miRNA-enriched EVs could increase circulating miRNA in mice. Significantly higher concentrations of circulating miR133a-3p were detected when 200 μg EV proteins (5 μL of miR133a-3p enriched EVs) were injected (Fig. 3A). We estimated by quantitative RT-PCR that the content of miR133a-3p in 1 mL of our miR-133a-3p-enriched EVs equaled that in 37,543 mL of mouse blood. Thus, 5 μL of our EV samples would contain the miR-133a-3p content of 5 × 37,543 μL (188 mL) in mouse blood, which is ∼75-fold of total blood miR-133a-3p content of an adult mouse (assuming 2.5 mL total blood for an adult mouse).26

FIG. 3.

Detection of miR-133a-3p after intraperitoneal injection into mice. (A) Determining the amount of miR-133a-3p-enriched EV needed to increase circulating miR-133a-3p. Blood was collected 4 h after injection. ** and *** indicate p < 0.01 and p < 0.0001 compared with the group injected with EVs from NT control cells (Tukey's multiple comparison test after ANOVA). (B) Examine the duration of injected miR-133a-3p-enriched EV in circulation. The amount of EV injected per mouse was 200 μg protein. *** p < 0.0001 compared with the group injected with EVs from NT control cells (Bonferroni post-tests after ANOVA). NT, nontargeting.

We then examined the duration of the EV-delivered miR-133a-3p in mouse circulation. We detected increased miR133a-3p at 4 and 8 h, but not 12 or 24 h after injection when 200 μg of miR-133a-3p-enriched EVs were injected (Fig. 3B). This observation is consistent with earlier observations that EVs have a relatively short half-life in animal circulation.27,28 Nevertheless, injecting miRNA-enriched EVs increased circulating miRNA for at least 8 h.

Discussion

This work describes a method for large-scale production of EVs enriched with a specific miRNA. At present miRNAs are commonly introduced into cells by complexing with liposomes that limit their in vivo applications. Exosomes and EVs are receiving increasing interest as drug delivery vehicles, but their use to deliver miRNAs is hampered by difficulties associated with loading miRNAs into exosomes/EVs. Loading miRNAs into isolated EVs in vitro by electroporation10–13 or liposomes14 is inefficient and incompatible with large-scale preparation. Transfecting synthetic miRNA into cultured cells and then purifying exosomes from these cells15,16 faces similar challenges. Mesenchymal stem cells treated with miRNA-expressing plasmids17 or lentivirus18 have been used to prepare miRNA-enriched EVs, but again are inadequate for large-scale preparation of miRNA-enriched EVs.

Here we generated cells that stably overexpressed miR-133a-3p or miR-202-5p and showed that EVs isolated from these cells contained hundreds or thousands fold more respective miRNA than EVs from control cells. We used a system adding sequence motifs to precursor miRNA sequences to enhance miRNA exosomal secretion.24,25 This modification indeed increased the ratio of EV miR-202-5p versus cellular miR-202-5p. However, as both the cellular and EV miRNAs were much lower than those of the unmodified system, we used the unmodified system for subsequent experiments. Greatly reduced total miRNA expression from the modified system could result from the H1 promoter, or the modification of the precursor sequences that interferes with the processing of the mature miRNA. Using the same promoter for the two expression systems may help to distinguish the two possibilities.

Of importance, these cells can be grown in bioreactors at high density to further increase the miRNA content in EVs, and the EVs can be efficiently concentrated without forming insoluble precipitates, a problem often encountered when preparing exosomes/EVs by ultracentrifugation. The procedure enabled us to produce large quantities of miRNA-enriched EVs for in vitro and in vivo experiments. Currently it is possible to make large quantities of EVs from a specific cell source. However, it is difficult to obtain large quantities of EVs enriched with a specific miRNA. The novelty of the method described here is the ability to produce large quantities of specific miRNA-enriched EVs that make the in vivo delivery of therapeutic miRNA through EVs possible.

We showed that the EVs produced following this procedure increased concentrations of circulating miRNAs for at least 8 h. Several studies have suggested that circulating exosomal miRNAs might play important roles in regulating physiologic and pathologic processes.7–9 Now the ability to make large quantities of EVs enriched with a specific miRNA makes it possible to further study the roles of exosomal miRNAs. In addition, being able to deliver large quantities of miRNA in vivo by exosomes makes it possible to explore therapeutic applications of specific miRNAs.

One shortcoming of this method is the requirement of continued proliferation of the cells for cloning and subsequent large-scale production. This requirement prevents us from using most primary cells and some adult stem cells for this purpose. Another shortcoming is that the basal contents of the EVs are uncontrollable and are determined by the cells used for overexpression. In addition, both the 3p and 5p are overexpressed from the precursor and currently it is difficult to enrich only one of them. The last issue may not be a problem in some situations because this is the way that endogenous miRNAs are expressed, but will be a problem when the functions of 3p and 5p of a specific miRNA are to be studied.

Conclusion

Using high-density bioreactors to culture cells engineered to overexpress a specific miRNA, we generated miRNA-enriched EVs at large quantities. These miRNA-enriched EVs may be useful for miRNA delivery in in vitro and in vivo applications.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Karen Klein (Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute, which is supported through NIH grant UL1 TR 001420) for editing the article.

Authors' Contribution

B.L. and A.A. designed the study; K.W.Y., N.L., V.M. and R.N.S. performed the experiments; B.L. wrote the article. All the authors discussed the results, commented, and revised the article.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Heijnen H.F., Schiel A.E., Fijnheer R., Geuze H.J., and Sixma J.J. Activated platelets release two types of membrane vesicles: microvesicles by surface shedding and exosomes derived from exocytosis of multivesicular bodies and alpha-granules. Blood 94, 3791, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ratajczak J., Miekus K., Kucia M., et al. . Embryonic stem cell-derived microvesicles reprogram hematopoietic progenitors: evidence for horizontal transfer of mRNA and protein delivery. Leukemia 20, 847, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alvarez-Erviti L., Seow Y., Yin H., Betts C., Lakhal S., and Wood M.J. Delivery of siRNA to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes. Nat Biotechnol 29, 341, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eulalio A., Huntzinger E., and Izaurralde E. Getting to the root of miRNA-mediated gene silencing. Cell 132, 9, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Selbach M., Schwanhäusser B., Thierfelder N., Fang Z., Khanin R., and Rajewsky N. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature 455, 58, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Valadi H., Ekström K., Bossios A., Sjöstrand M., Lee J.J., and Lötvall J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol 9, 654, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ying W., Riopel M., Bandyopadhyay G., et al. . Adipose tissue macrophage-derived exosomal miRNAs can modulate in vivo and in vitro insulin sensitivity. Cell 171, 372, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Melo S.A., Sugimoto H., O'Connell J.T., et al. . Cancer exosomes perform cell-independent microRNA biogenesis and promote tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 26, 707, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang Y., Kim M.S., Jia B., et al. . Hypothalamic stem cells control ageing speed partly through exosomal miRNAs. Nature 548, 52, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang D., Lee H., Zhu Z., Minhas J.K., and Jin Y. Enrichment of selective miRNAs in exosomes and delivery of exosomal miRNAs in vitro and in vivo. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 312, L110, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wahlgren J., De L Karlson T., Brisslert M., et al. . Plasma exosomes can deliver exogenous short interfering RNA to monocytes and lymphocytes. Nucleic Acids Res 40, e130, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hood J.L., Scott M.J., and Wickline S.A. Maximizing exosome colloidal stability following electroporation. Anal Biochem 448, 41, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Momen-Heravi F., Bala S., Bukong T., and Szabo G. Exosome-mediated delivery of functionally active miRNA-155 inhibitor to macrophages. Nanomedicine 10, 1517, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shtam T.A., Kovalev R.A., Varfolomeeva E.Y., Makarov E.M., Kil Y.V., and Filatov M.V. Exosomes are natural carriers of exogenous siRNA to human cells in vitro. Cell Commun Signal 11, 88, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shimbo K., Miyaki S., Ishitobi H., et al. . Exosome-formed synthetic microRNA-143 is transferred to osteosarcoma cells and inhibits their migration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 445, 381, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. O'Brien K., Lowry M.C., Corcoran C., et al. . miR-134 in extracellular vesicles reduces triple-negative breast cancer aggression and increases drug sensitivity. Oncotarget 6, 32774, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lou G., Song X., Yang F., et al. . Exosomes derived from miR-122-modified adipose tissue-derived MSCs increase chemosensitivity of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hematol Oncol 8, 122, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang B., Yao K., Huuskes B.M., et al. . Mesenchymal stem cells deliver exogenous microRNA-let7c via exosomes to attenuate renal fibrosis. Mol Ther 24, 1290, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lu P., Li H., Li N., et al. . MEX3C interacts with adaptor-related protein complex 2 and involves in miR-451a exosomal sorting. PLoS One 12, e0185992, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen J.F., Mandel E.M., Thomson J.M., et al. . The role of microRNA-1 and microRNA-133 in skeletal muscle proliferation and differentiation. Nat Genet 38, 228, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen J., Cai T., Zheng C., et al. . MicroRNA-202 maintains spermatogonial stem cells by inhibiting cell cycle regulators and RNA binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 45, 4142, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kuwabara Y., Ono K., Horie T., et al. . Increased microRNA-1 and microRNA-133a levels in serum of patients with cardiovascular disease indicate myocardial damage. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 4, 446, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Joosse S.A., Müller V., Steinbach B., Pantel K., and Schwarzenbach H. Circulating cell-free cancer-testis MAGE-A RNA, BORIS RNA, let-7b and miR-202 in the blood of patients with breast cancer and benign breast diseases. Br J Cancer 111, 909, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Batagov A.O., Kuznetsov V.A., and Kurochkin I.V. Identification of nucleotide patterns enriched in secreted RNAs as putative cis-acting elements targeting them to exosome nano-vesicles. BMC Genomics 12(Suppl. 3), S18, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bolukbasi M.F., Mizrak A., Ozdener G.B., et al. . miR-1289 and “zipcode”-like sequence enrich mRNAs in microvesicles. Mol Ther Nucl Acids 1, e10, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Riches A.C., Sharp J.G., Thomas D.B., and Smith S.V. Blood volume determination in the mouse. J Physiol 228, 279, 1973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Takahashi Y., Nishikawa M., Shinotsuka H., et al. . Visualization and in vivo tracking of the exosomes of murine melanoma B16-BL6 cells in mice after intravenous injection. J Biotechnol 165, 77, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bala S., Csak T., Momen-Heravi F., et al. . Biodistribution and function of extracellular miRNA-155 in mice. Sci Rep 5, 10721, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]