Abstract

Photorelease of caged compounds is among the most powerful experimental approaches for studying cellular functions on fast timescales. However, its full potential has yet to be exploited, as the number of caged small molecules available for cell biological studies has been limited by synthetic challenges. Addressing this problem, a straightforward, one‐step procedure for efficiently synthesizing caged compounds was developed. An in situ generated benzylic coumarin triflate reagent was used to specifically functionalize carboxylate and phosphate moieties in the presence of free hydroxy groups, generating various caged lipid metabolites, including a number of GPCR ligands. By combining the photo‐caged ligands with the respective receptors, an easily implementable experimental platform for the optical control and analysis of GPCR‐mediated signal transduction in living cells was developed. Ultimately, the described synthetic strategy allows rapid generation of photo‐caged small molecules and thus greatly facilitates the analysis of their biological roles in live cell microscopy assays.

Keywords: caged compounds, cell signaling, lipids, one-step synthesis, platelet activating factor

A coumarin‐based triflate reagent enables one‐step synthesis of photocaged probes for optically controlling GPCR signaling.

Modern screening approaches, particularly lipidomics and metabolomics, allow for the rapid identification of small molecules that appear to be involved in cellular processes.1, 2, 3 Given the remarkably improved sensitivity and scope of these methods, the validation of the obtained hits in live cell experiments has now become the major bottleneck when studying the biology of lipids and other metabolites.4, 5, 6, 7 In particular, understanding fast processes such as signal transduction requires the ability to measure reaction kinetics in living cells.7 Obtaining such kinetic datasets necessitates to change the levels of cellular small molecules in a rapid fashion and to monitor downstream responses with organelle‐specific biosensors.8, 9, 10 Current methods for rapidly modulating cellular small molecules are based on optogenetic proteins,11, 12 chemical dimerizers13, 14 and photo‐caged15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 or photo‐switchable19, 22, 23, 24 chemical probes. However, implementing new optogenetic tools or chemical dimerizer systems is not straightforward and requires significant effort. The increased use of photo‐caged small molecules could in principle serve as an alternative experimental strategy, yet the de novo development of these chemical probes usually requires challenging multi‐step syntheses, a few notable examples25 notwithstanding.

Thus, a renewed focus on synthetic strategies for generating photo‐caged, bioactive small molecules in a cost‐ and time‐efficient manner is required. Ideally, commercially available parent molecules should directly be equipped with photo‐caging groups, without the need to rely on protection group chemistry or total synthesis. As caging groups are mostly attached to phosphate, carboxylate or amine groups, the resulting synthetic problem can often be reduced to the derivatization of one of these functional groups with a photo‐caging group in the presence of free hydroxyl groups. In some examples, most prominently for photo‐caged nucleotides, such transformations have been achieved,25, 26 typically through utilization of diazo reagents or leaving groups in benzylic positions. Despite these early successes, the reported substrate scope of such reactions has remained relatively limited, presumably due to the fact that the reactivity of the utilized diazo reagents is not sufficient for alkylating less nucleophilic substrates such as zwitterionic or sterically hindered phosphodiester groups commonly found in phospholipids. In addition, the required elevated temperatures might further reduce the applicability of diazo reagents for sensitive substrates such as lipids and lipid metabolites.

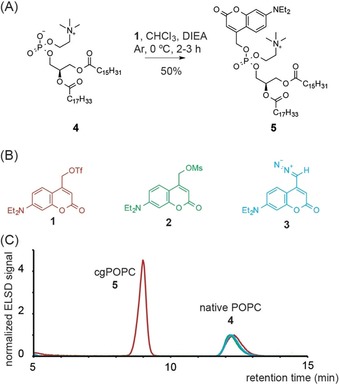

We reasoned that a benzylic coumarinyl triflate reagent (1) should provide sufficient reactivity under mild conditions to functionalize less nucleophilic phosphates and carboxylates, while still leaving hydroxyl groups unaffected (Scheme 1). However, benzylic or allylic triflates are not typically used in nucleophilic substitution reactions featuring carboxylate or phosphate nucleophiles. In fact, to the best of our knowledge, only one such example has been reported for a carboxylate nucleophile27 and none for phosphates. We proceeded to synthesize 1 starting from the corresponding coumarin alcohol. The respective diazo and mesylate reagents 2 and 3 were synthesized according to previously described methodology.25 Due to the inherent instability of benzylic triflates, 1 was generated and used in situ to react with phosphatidylcholine (4) and platelet activating factor (PAF) as model substrates. We confirmed that the triflate reagent 1 is sufficiently reactive to alkylate sterically hindered phosphodiesters (Figure 1) at 0 °C, whereas transformations using the corresponding mesylate and diazo reagents (2,3) did not result in noticeable conversion (Figure 1 B,C). Prolonged reaction times at higher temperatures, in line with literature protocols for diazo compounds,25 led to minimal product formation for coumarin mesylate and triflate reagents while no conversion was observed for the diazo reagent (Figure S1 in the Supporting Information).

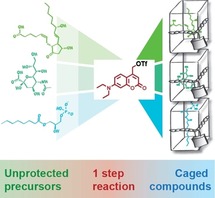

Scheme 1.

Schematic representation of one‐step synthesis of caged compounds. Unprotected precursor molecules are treated with an in situ generated benzylic coumarin triflate reagent which reacts with phosphate and carboxylate groups in the presence of unprotected hydroxy groups, thus circumventing lengthy synthetic routes and improving availability of caged compounds for cell biological applications.

Figure 1.

(A) Conversion of POPC 4 to photo‐caged POPC 5 using coumarinyl reagents 1. (B) Coumarinyl reagents utilized for functionalizing phosphate and carboxylate moieties. (C) HPLC traces of reactions of the coumarinyl reagents 1 (red) 2 (green) and 3 (blue) with native POPC 4. Traces were normalized to the POPC signal.

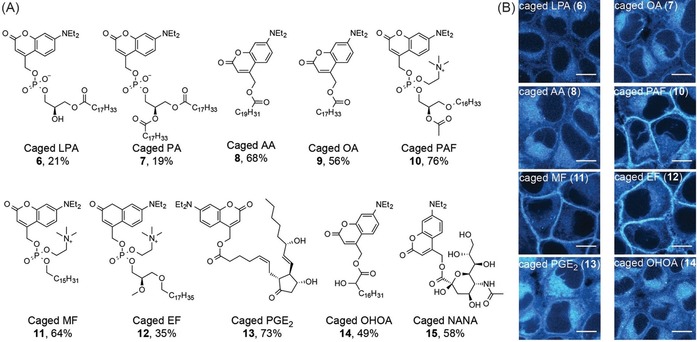

After developing a suitable reagent for functionalizing phosphate and carboxylate moieties with photo‐caging groups, we explored the substrate space for potential interference by free hydroxyl groups and other sensitive moieties while simultaneously focusing on generating biologically relevant probes. Apart from phosphatidylcholine (4, PC), we chose to include the phospholipid phosphatidic acid (PA), the natural GPCR (G‐protein coupled receptor) ligands lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), platelet activating factor (PAF) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), the synthetic GPCR agonists miltefosin (MF) and edelfosin (EF), the fatty acids oleic (OA) and arachidonic acid (AA), 2‐hydroxy‐oleic acid (OHOA) and finally N‐acteyl‐neuraminic acid (NANA), a key ganglioside building block. NANA represents a particularly challenging substrate as it features a sterically hindered carboxyl group in the presence of multiple primary and secondary hydroxy groups. Strikingly, all molecules were readily converted into their photo‐caged versions in acceptable to good yields with small adaptations to the general one‐step protocol (Figure 2 A, see supplementary information for details). Compounds were photo‐physically characterized (Figure S2) and photorelease of the intact parent molecules was confirmed by HPLC and mass spectrometry (Figure S3). Out of the 11 coumarin‐caged compounds generated via this route, three (caged LPA (6), caged arachidonic acid (8) and caged oleic acid (9)) have been reported before,16, 28 whereas the other 8 (caged PC (5), caged PA (7), caged PAF (10), caged miltefosin (11), caged edelfosin (12), caged prostaglandin E2 (13), caged 2‐hydroxy oleic acid (14) and caged N‐acteyl‐neuraminic acid (15)) represent new molecular probes. This suggests that in situ generated triflate reagents such as 1 are powerful synthetic tools for providing rapid access to caged compounds that otherwise would only be accessible through more elaborate syntheses.

Figure 2.

One‐step synthesis of bioactive caged compounds. (A) Overview of generated photo‐caged compounds. Unprotected parent compounds were typically reacted with in situ generated 1 in the presence of DIEA in chloroform at 0 °C. In the case of N‐acetyl‐neuraminic acid, DMF was used to enhance solubility. Yields are given below each structure. (B) Cellular localization of photo‐caged compounds 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14. Image acquisition settings were optimized for each compound, larger fields of view and images acquired using identical settings for all compounds are displayed in Supplementary Figure S4 and S5 for comparison. Scale bars indicate 10 μm.

We next assessed the GPCR ligands among the new photo‐caged compounds (6, 8–13) in live cell fluorescence microscopy assays. We first determined cellular uptake in HeLa Kyoto cells by fluorescence microscopy using the intrinsic fluorescence of the diethylamino‐coumarin group as readout. All compounds proved to be membrane permeable, despite the fact that some molecules (6, 10, 11, 12) are intrinsically positively or negatively charged (Figure 2 B, Figure S4). While the compounds mostly exhibited the unspecific localization in cellular membranes typical for diethylamino‐coumarin‐caged molecules, overall fluorescence intensities varied significantly among compounds (Figure S5). Intriguingly, compounds featuring a choline headgroup exhibited a certain preference for the plasma membrane (Figure 2 B, Figure S4), presumably due to the fact that these positively charged molecules are attracted to the negatively charged inner leaflet of the plasma membrane.

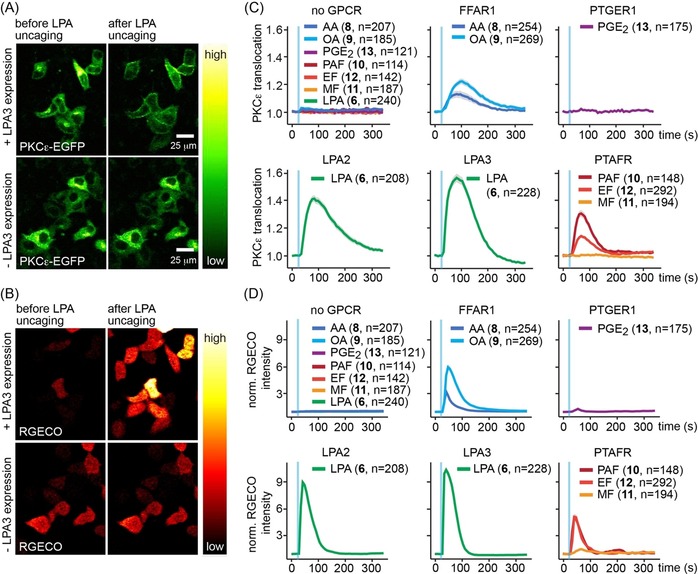

To demonstrate the utility of the new probes for acutely activating GPCRs, we used an assay to monitor the recruitment of the DAG effector protein PKCϵ to the plasma membrane and Ca2+ signaling in response to GPCR activation. Specifically, we used a PKCϵ‐EGFP fusion protein and the genetically encoded Ca2+ sensor RGECO29 to observe Ca2+ transients in two‐color time‐lapse fluorescence microscopy experiments. In order to ensure the observation of specific receptor‐ligand interactions, we heterologously expressed the respective GPCRs (FFAR1, LPA2, LPA3, PTFAR, PTGER1, see Supplementary Table S1 for details) in HeLa Kyoto cells. When adding free ligands to GPCR‐expressing cells, we observed ligand‐specific recruitment of PKCϵ and accompanying Ca2+ signals (Figures S6 and S7). As a control we added the free ligands to cells not expressing the

GPCRs and observed no PKCϵ recruitment to the plasma membrane or Ca2+ transients (Figure S7). In subsequent live cell photoactivation experiments, we monitored temporal PKCϵ and Ca2+ signaling profiles in response to uncaging of compounds 6 and 8–13 in HeLa cells transiently expressing the respective GPCRs. In principle, uncaging experiments can be carried out in two distinct ways: (i) as wash‐off experiments, where the loading solution is removed after a defined time‐period and only the cellular pool of caged compound is photoactivated; or (ii) as leave‐on‐experiments, where the loading solution is left on the sample and photoactivation takes place within cells and the surrounding solution. Wash‐off experiments are typically associated with a stable cellular caged compound concentration, which is not the case for leave‐on experiments due to continued compound uptake from the medium. We thus decided to perform only wash‐off experiments but nevertheless tested the applicability of the synthesized compounds for leave‐on experiments. To this end, we compared cellular Ca2+ transients after addition of free and caged compounds. We found that the caged fatty acids (7,8) can be used at all tested concentrations, whereas caged LPA (6), caged PAF (10) and caged edelfosin (12) have narrower suitable concentration windows, while caged PGE2 (13) was found to be not suitable for leave‐on experiments (Figure S8, see supplementary information for details). To ensure that the utilized compound loading procedures for wash‐off uncaging experiments had no adverse effects on GPCR mediated signal transduction, we confirmed that both, resting Ca2+ levels and Ca2+ transients induced by addition of free ligands were similar for loaded and unloaded cells with the exception of caged PGE2 (13), for which a slight desensitization towards the ligand was observed (Figure S9, see supplementary information for details).

We found that photoactivation of all biologically active compounds elicited signaling responses (Figure 3, Figure S10), whereas no responses where observed in the absence of transient GPCR expression (Figure 3 C, D, upper left panels, Figure S11). Specifically, photorelease of LPA in cell expressing the LPA2 or LPA3 receptors triggered intense but brief (ca. 100 s long) Ca2+ transients, accompanied by longer (ca. 150 s long) PKCϵ recruitment events (Figure 3 C, D). Weaker effects were observed for uncaging of oleic and arachidonic acid in cells expressing the corresponding receptor FFAR1 (Figure 3 C, D). Photorelease of PGE2 triggered brief, low‐intensity Ca2+ transients but no discernible PKCϵ activation (Figure 3 C, D) in PTGER1 expressing cells. Uncaging of PAF in cells expressing the PAF receptor PTAFR resulted in pronounced Ca2+ transients and PKCϵ recruitment, uncaging of edelfosin was followed by subtler responses, whereas photorelease of miltefosin did not elicit signaling events (Figure 3 C, D) These findings are in line with responses observed after adding the free ligands (Figure S6). Taken together, these data demonstrate that the newly synthesized photo‐caged GPCR ligands enable optical control of GPCR mediated signal transduction.

Figure 3.

Photo‐caged compounds enable optical control of GPCR mediated signal transduction. (A,B) Cellular localization of PKCϵ‐EGFP (A) and RGECO fluorescence intensity (B) before and after uncaging of LPA from 6 in HeLa Kyoto cells with (upper panels) or without overexpression (lower panels) of the LPA receptor LPA2. Scale bars indicate 25 μm, images for the same conditions in a and b show the same cells. (C,D) Quantification of PKCϵ‐EGFP recruitment (C) and RGECO fluorescence intensity (D) upon uncaging of caged arachidonic acid (8), caged oleic acid (9), caged prostaglandin E2 (13), caged lysophosphatidic acid (6), caged platelet activating factor (10), caged edelfosin (12) and caged miltefosin (11) in HeLa Kyoto cells transiently expressing the corresponding GPCRs (FFAR1, PTGER1, LPA2, LPA3, PTFAR). Upper left panels depict the quantification of PKCϵ‐EGFP recruitment (C) and RGECO fluorescence intensity (D) upon uncaging of all compounds in HeLa Kyoto cells without GPCR expression as negative control. Blue bars indicate uncaging events, data are mean, shaded areas indicate SEM, n‐numbers are given in brackets behind compound identifiers and indicate single cell traces.

Furthermore, we observed that single‐cell traces in response to ligand uncaging were much more homogeneously distributed compared to experiments in which the free ligands were added (Figures S12–S15) suggesting that our strategy should be well suited to analyze the onset kinetics of GPCR mediated signaling events.

In summary, we developed a new, highly efficient route for the synthesis of photo‐caged, bioactive small molecules, bypassing the currently challenging syntheses that have resulted in a slow pace of probe development. Using our newly developed synthetic strategy, we generated a series of photo‐caged GPCR ligands which enabled optical control of GPCR mediated signaling for multiple receptors in live‐cell time lapse experiments. We anticipate that the methodology reported here will significantly accelerate the development of new photo‐caged small molecules in the future and further boost chemical biology approaches for studying cellular signaling.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following services and facilities at MPI‐CBG Dresden for their support: Mass Spectrometry Facility and the Light Microscopy Facility. We are particularly grateful for the outstanding support and expert advice of Anna Shevchenko, Jan Peychl and Sebastian Bundschuh. A.N. gratefully acknowledges funding by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Grant Agreement GA758334 ASYMMEM), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) as a member of the TRR83 consortium (Project Number 112927078‐TRR 83) and the Indo‐German Max‐Planck Lipid Center.

N. Wagner, M. Schuhmacher, A. Lohmann, A. Nadler, Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 15483.

References

- 1. Shevchenko A., Simons K., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 593–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Atilla-Gokcumen G. E., Muro E., Relat-Goberna J., Sasse S., Bedigian A., Coughlin M. L., Garcia-Manyes S., Eggert U. S., Cell 2014, 156, 428–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Köberlin M. S., Snijder B., Heinz L. X., Baumann C. L., Fauster A., Vladimer G. I., Gavin A. C., Superti-Furga G., Cell 2015, 162, 170–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harayama T., Riezman H., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 281–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Muro E., Atilla-Gokcumen G. E., Eggert U. S., Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 1819–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Laguerre A., Schultz C., Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2018, 53, 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Honigmann A., Nadler A., Biochemistry 2018, 57, 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goujon A., Colom A., Straková K., Mercier V., Mahecic D., Manley S., Sakai N., Roux A., Matile S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 3380–3384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xu W., Zeng Z., Jiang J. H., Chang Y. T., Yuan L., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 10372; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 10528. [Google Scholar]

- 10. DiPilato L. M., Zhang J., Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010, 14, 37–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang K., Cui B., Trends Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 92–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rost B. R., Schneider-Warme F., Schmitz D., Hegemann P., Neuron 2017, 96, 572–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feng S., Laketa V., Stein F., Rutkowska A., MacNamara A., Depner S., Klingmüller U., Saez-Rodriguez J., Schultz C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 6720–6723; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 6838–6841. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Voß S., Klewer L., Wu Y.-W., Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2015, 28, 194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wagner N., Stephan M., Höglinger D., Nadler A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 13339–13343; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 13523–13527. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nadler A., Yushchenko D. A., Müller R., Stein F., Feng S., Mulle C., Carta M., Schultz C., Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Feng S., Harayama T., Montessuit S., David F. P. A., Winssinger N., Martinou J. C., Riezman H., Elife 2018, 7, e34555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ellis-Davies G. C. R., Nat. Methods 2007, 4, 619–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mayer G., Hechel A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 4900–4921; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2006, 118, 5020–5042. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bardhan A., Deiters A., Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2019, 57, 164–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Herzig L.-M., Elamri I., Schwalbe H., Wachtveitl J., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 14835–14844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Broichhagen J., Trauner D., Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Frank J. A., Yushchenko D. A., Hodson D. J., Lipstein N., Nagpal J., Rutter G. A., Rhee J.-S., Gottschalk A., Brose N., Schultz C., Trauner D., Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016, 12, 755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Albert L., Peñalver A., Djokovic N., Werel L., Hoffarth M., Ruzic D., Xu J., Essen L. O., Nikolic K., Dou Y., Vázques O., ChemBioChem 2019, 20, 1417–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.

- 25a. Eckardt T., Hagen V., Schmidt R., Schweitzer C., Synthesis 2002, 703–710; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25b. Weinrich T., Gränz M., Grünewald C., Prisner T. F., Göbel M. W., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 491–496; [Google Scholar]

- 25c. Wong P. T., Roberts E. W., Tang S., Mukherjee J., Cannon J., Nip A. J., Corbin K., Krummel M. F., Choi S. K., ACS Chem. Biol. 2017, 12, 1001–1010; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25d. Ito K., Maruyama J., Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1983, 31, 3014–3023. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ando H., Okamoto H., Methods Cell Sci. 2003, 25, 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hughes G., O'Shea P., Goll J., Gauvreau D., Steele J., Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 3189–3196. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hövelmann F., Jalink K., Schultz C., Nadler A., Müller R., Kedziora K. M., Cell Chem. Biol. 2016, 23, 629–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhao Y., Araki S., Wu J., Teramoto T., Chang Y.-F., Nakano M., Abdelfattah A. S., Fujiwara M., Ishihara T., Nagai T., Campbell R. E., Science 2011, 333, 1888–1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary