Abstract

Dermal–epidermal interaction plays a role in many pathophysiological processes, such as tumor invasion and psoriasis, as well as wound healing, and is mediated at least in part by secretory factors. In this study, we investigated the factor(s) involved. We found that stanniocalcin‐1 (STC1), a cytokine, is expressed at the basal layer of epidermis. Knockdown of STC1 with siRNA in HaCaT cells decreased matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP1) expression, suggesting that STC1 serves as an autocrine factor, maintaining MMP1 mRNA expression in the epidermal layer. In dermal fibroblasts, STC1 increased MMP1 mRNA expression and decreased collagen1A1 and elastin mRNA expression. These actions were inhibited by SP600125, a jun kinase (JNK) inhibitor. Nuclear translocation of AP‐1, a downstream signal of JNK, was implicated in the actions of STC1. In a coculture system of HaCaT cells and fibroblasts, used as a model of dermal–epidermal interaction, knockdown of STC1 in HaCaT cells with siRNA reduced the negative effects (i.e., induction of MMP1 and decrease of collagen1A1 and elastin) of STC1 on fibroblasts. These results suggest that STC1 secreted from the epidermal layer is a mediator of dermal–epidermal interaction.

Keywords: collagen, dermal–epidermal interaction, elastin, MMP1, stanniocalcin‐1

Abbreviations

- JNK

jun kinase

- MMP1

matrix metalloproteinase 1

- STC1

stanniocalcin‐1

1. INTRODUCTION

Epidermal–dermal interaction plays an important role in skin development and maintenance of skin condition.1 For example, in the wound healing process, epithelial cells act to terminate hypertrophy of the dermal layer by modifying dermal fibroblast function, including inhibition of production of type 1 collagen, a major component of the dermal layer, and increase of matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP1), which degrades type 1 collagen.2, 3 Factors secreted from the epidermal side are thought to mediate these changes,4, 5 and if the changes are delayed, fibrosis may occur. On the other hand, in epithelial cancer invasion (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma, SCC), epithelial cells secrete multiple factors that weaken the dermal layer by increasing MMP1 production and inhibiting matrix production.6 Therefore, modulation of these secretory factors has potential clinical value, and studies are required to identify them.

STC1 is a glycoprotein secreted from a variety of tissues and is conserved from fish to human.7, 8 It is thought to show both autocrine and paracrine actions, being involved in inflammation,9 metabolism,10 development,11 and angiogenesis.12 It is expressed in various types of human epithelial cell‐derived malignancies, such as lung cancer,13 esophageal cancer,14 and breast cancer.15 It is also related to metastasis of renal cancer.16 Furthermore, in renal carcinoma cells, inhibition of STC1 expression reduced invasive activity.17 Thus, STC1 secretion may regulate invasion of epithelial cells into the connective tissue layer.

Therefore, in this study, we investigated the role of STC1 in dermal–epidermal interaction by means of epidermal–dermal cell coculture, quantitative real‐time PCR measurements of mRNA expression, and histological observation.

2. METHODS

2.1. Materials

Neonatal human dermal fibroblasts were purchased from Lonza (Walkersville, MD). SP600125 and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). HaCaT cells were obtained from Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum (DKFZ, Heidelberg, Germany) with a material transfer agreement. Neonatal human keratinocytes were purchased from Lonza (Walkersville, MD) and cultured with Epilife GIBCO/BRL (Carlsbad, CA). Superscript VILO, Lipofectamine, and DMEM were from GIBCO/BRL (Carlsbad, CA). Cell culture flasks, dishes, and Transwells were purchased from Falcon (Franklin Lakes, NJ). RNeasy Protect Kit and QIAzol were purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). Rabbit anti‐phospho‐c‐JUN antibody and fluorescein‐labeled anti‐mouse IgG antibody were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, MA). Stanniocalcin‐1 was purchased from Biovendor (Candler, NC).

2.2. Coculture system

HaCaT cells and fibroblasts were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% (w/v) FBS in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air at 37°C. When cells became subconfluent, they were harvested with 0.025% trypsin and 0.01% EDTA and plated. HaCaT cells were plated at a density of 25,000 cells/cm2. Cell abundance was measured by alamarBlue assay18(Wako; Tokyo, Japan) according to the instruction manual. Dermal fibroblasts were plated on Transwells (Falcon; Franklin Lakes, NJ) at a density of 1,250 cells/cm2. After 24 hr, HaCaT cells were transfected with siRNA by using Lipofectamine according to the instruction manual. Twelve hours later, fibroblasts were layered onto the HaCaT cells. Two days later, fibroblasts in the upper well were harvested with QIAzol. siRNA for STC1 (sequence: CTGCTTAAACAAAGCAGTATA) and negative control siRNA were purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA).

2.3. Quantitative real‐time PCR

RNA was extracted using a RNeasy Protect Kit and translated to cDNA using Superscript VILO according to the manufacturer's instructions. 28S rRNA was quantified as an internal control, and quantification of cDNA for each selected gene was conducted by real‐time PCR amplification using a LightCycler.19 The cycle threshold values (Ct values) calculated by LightCycler software ver. 3.5 were normalized to 28S rRNA for each sample. Primers and probes used in this study were: MMP1 forward ATTTGCCGACAGAGATGAAGTCC, reverse GGGTATCCGTGTAGCACATTCTG; STC1 forward ATGAGGCGGAGCAGAATGAC, reverse GTTGAGGCAACGAACCACTT; COL1A1 forward AGCAGGCAAACCTGGTGAAC, reverse AACCTCTCTCGCCTCTTGCT; ELN forward TGTCCATCCTCCACCCCTCT, reverse CCAGGAACTCCACCAGGAAT; and 28S rRNA forward ACGGTAACGCAGGTGTCCTA, reverse CCGCTTTCACGGTCTGTATT.

2.4. Histological observation

Skin specimens were excised from the inner side of an upper arm of eight Japanese female subjects in their 20s. All studies were approved by the ethics committee of Shiseido Research Center. Informed consent was obtained from each subject prior to all studies. Eight Caucasian females, in their 40s, with abdominal skin samples were purchased from Biopredic International (Rennes, France). Samples had been prepared from skin obtained during cosmetic surgery according to the French Law L.1245 CSP “product and element of human body taken during surgical procedure and used for scientific research.” The specimens were fixed with acetone and embedded in paraffin according to the AMeX procedure.20 Sections of 5 μm were deparaffinized, rehydrated through graded alcohols, and stained with hematoxylin–eosin (HE) or stained with rabbit anti‐human STC1 polyclonal antibody (HPA023918; Sigma), followed by detection with fluorescein‐labeled anti‐rabbit IgG antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA) or Envision+ (Dako, Carpinteria, CA).

2.5. Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as means ± SEM. Differences between groups were examined for statistical significance by using Student's t test or Dunnett's test as a multiple comparison test. A p value of less than .05 was considered to indicate a significant difference.

3. RESULTS

3.1. STC1 is expressed at the basal layer of epidermis and serves to maintain MMP1 expression in epidermal cells

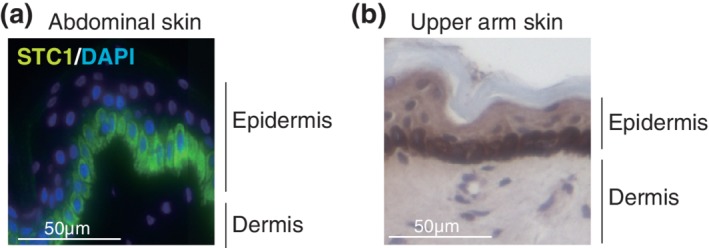

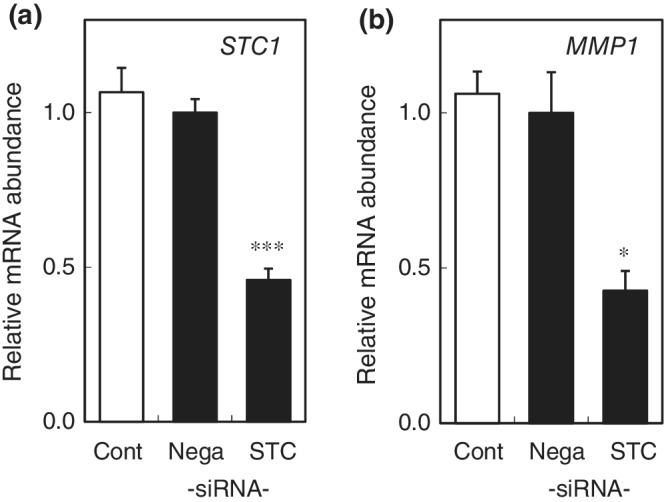

Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemical studies indicated that STC1 is specifically localized at the basal layer of the epidermis in skin specimens from sun‐protected areas at the inner side of the upper arm and the abdomen (Figure 1), whereas STC1 was not detected in dermal fibroblasts. To clarify the role of STC1 in epidermal cells, STC1 expression was knocked down with siRNA in HaCaT cells (Figure 2). Cell proliferation measured by alamarBlue assay and differentiation measured by mRNA expression analysis of differentiation markers (cytokeratins, involucrin, and loricrin) were unaffected (data not shown). On the other hand, MMP1 mRNA expression in HaCaT cells was significantly inhibited (Figure 2). Similar findings were obtained with a different siRNA for STC1 (data not shown). We also confirmed that addition of STC1 to HaCaT cells in which STC1 expression had been knocked down with siRNA significantly restored MMP1 expression (Figure SS1**). Thus, STC1 may have an autocrine function to maintain MMP1 gene expression in these cells.

Figure 1.

STC1 is expressed at the basal layer of epidermis. (a) Immunofluorescence and (b) immunohistochemical staining of STC1 in a representative acetone‐fixed specimen of abdominal skin or skin from the inner side of the upper arm of a female subject. Nuclei were stained with DAPI or hematoxylin, respectively

Figure 2.

STC1 contributes to maintenance of MMP1 expression in HaCaT cells

(a) Knockdown of STC1 mRNA with siRNA in HaCaT cells. mRNA abundance at 48 hr after transfection of siRNA for STC1 (STC), negative control siRNA (Nega), or no transfection (Cont) was expressed as mean ± SEM of three wells in each group. (b) MMP1 mRNA was decreased in the siRNA‐treated HaCaT cells. The statistical significance of differences between groups was determined by Dunnett's test. *: p < .05, ***: p < .001 compared with Nega

3.2. STC1 negatively regulates matrix‐related gene expression in dermal fibroblasts through the JNK pathway

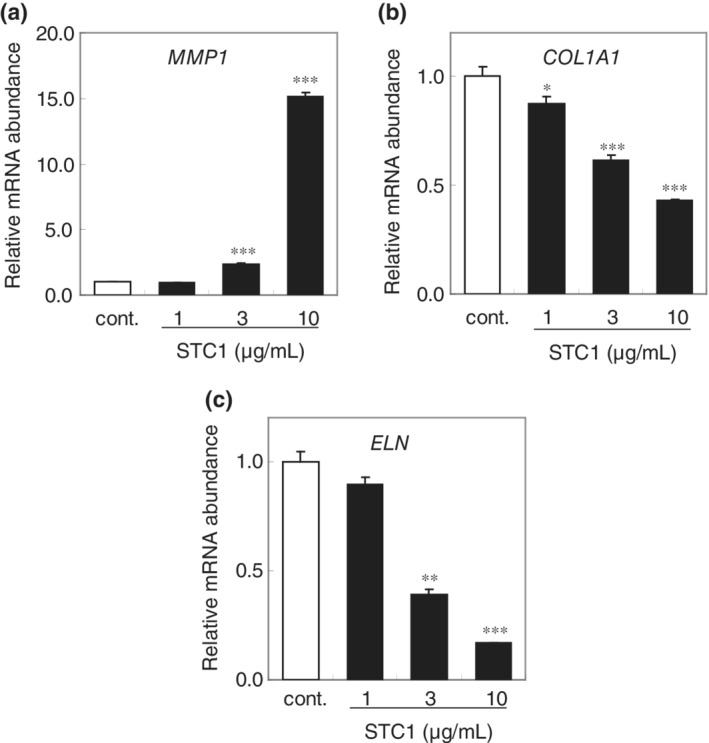

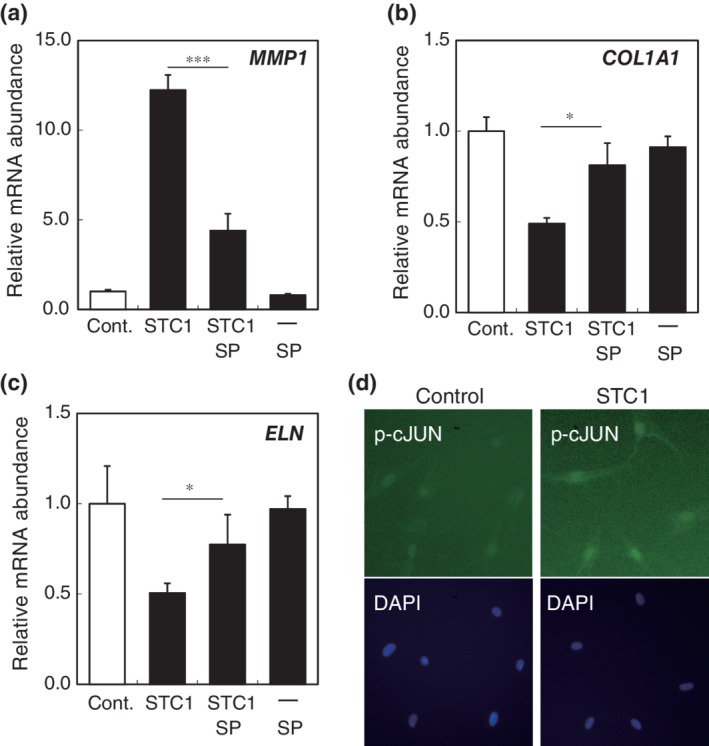

**As STC1 was expressed in the basal epidermal layer, we next investigated the influence of STC1 on dermal cells, fibroblasts. We found that STC1 concentration dependently increased MMP1 mRNA expression in fibroblasts (Figure 3a). STC1 also inhibited mRNA expression of both the collagen1a1 component of Type 1 collagen and elastin (Figure 3b,c). These results indicate that STC1 secreted from epidermis may be a negative regulator of the dermal layer. To investigate the mechanism of STC1 action on dermal fibroblasts, we examined the effects of various inhibitors of intracellular signaling molecules, such as NF‐kB and MAP kinase. JNK inhibitor SP600125 significantly inhibited the effects of STC1 (Figure 4a–c). Furthermore, we observed nuclear translocation of AP‐1, a transcription factor that is known to enhance MMP1 gene transcription and decrease collagen1A1 and elastin gene transcription, and a downsteam signaling molecule of JNK (Figure 4d).21, 22, 23 Thus, STC1 appears to negatively regulate dermal fibroblast matrix‐related gene transcription via the JNK‐AP‐1 pathway.

Figure 3.

STC1 negatively regulates dermal fibroblast matrix‐related gene expression. mRNA abundance of (a) MMP1, (b) collagen1A1, and (c) elastin in human dermal fibroblasts at 48 hr after addition of STC1, expressed as mean ± SEM of three wells in each group. The statistical significance of differences between groups was determined by Dunnett's test. n.s., Not significant; *, p < .05; **, p < .01; ***, p < .001 compared with control

Figure 4.

STC1 negatively influences dermal fibroblasts though the JNK pathway. mRNA abundance of (a) MMP1, (b) collagen1A1, (c) elastin in dermal fibroblasts treated with 5 μM JNK inhibitor (SP600125) for 3 hr, followed by treatment with 10 μg/mL STC1 for 24 hr. The negative influence of STC1 on mRNA expression in dermal fibroblasts (STC1) was significantly reversed by SP600125 (STC + SP), whereas SP600125 alone (SP) had no effect. mRNA abundance was expressed as mean ± SEM of three wells in each group. The statistical significance of differences between groups was determined by Dunnett's test. *: p < .05, ***: p < .001 of (STC + SP) compared with (STC1). (d) STC1 induces AP‐1 nuclear translocation (downstream signal of JNK). Phospho‐c‐JUN was immunocytochemically stained in dermal fibroblasts at the indicated time after addition of STC1. Nuclei were stained with DAPI

3.3. STC1 mediates the negative influence of epidermal cells on dermal fibroblasts

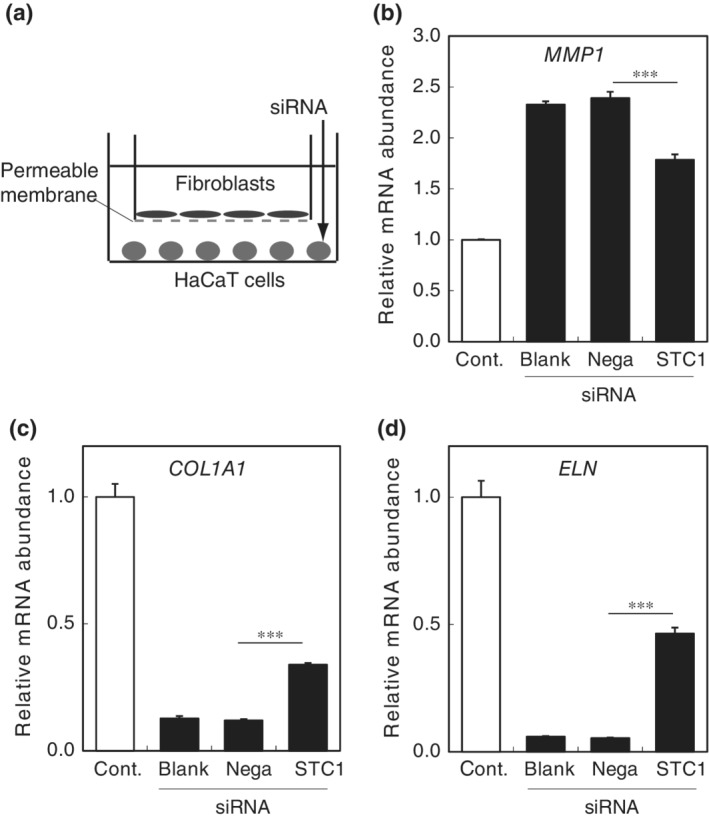

To confirm that STC1 from epidermal cells is a negative regulator of dermal fibroblasts, we constructed a coculture system of HaCaT cells and fibroblasts, separated by a permeable membrane (Figure 5a). In this system, the two cell types cannot contact each other directly, but signaling molecules can pass through the permeable membrane. When fibroblasts were cocultured with HaCaT cells, mRNA expression of MMP1 was significantly increased, while expression of collagen1A1 and elastin mRNAs was significantly decreased in the fibroblasts (Figure 5b–d). We further confirmed that normal epidermal cells significantly increase mRNA expression of MMP1 and significantly decrease collagen1A1 and elastin mRNA expression in fibroblasts in the same manner as HaCaT cells in the coculture system (Figure S2**). When STC1 expression in the HaCaT cells was knocked down with siRNA, the changes in mRNA expression of MMP1, collagen1A1, and elastin in fibroblasts were partially reversed. These results are consistent with the idea that STC1 from epidermal cells is a negative regulator of dermal fibroblasts.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of STC1 in HaCaT cells reduces the negative influence of HaCaT cells on matrix‐related gene expression of dermal fibroblasts in the coculture model. (a) Dermal fibroblasts were cocultured with or without HaCaT cells in Transwells. After 2 days of coculture, the abundance of (b) MMP1, (c) collagen1A1, and (d) elastin mRNAs in dermal fibroblasts was negatively influenced (Cont) compared with fibroblasts alone (blank). The changes were significantly ameliorated in dermal fibroblasts cocultured with HaCaT cells transfected with siRNA for STC1 (STC) compared with dermal fibroblasts cocultured with HaCaT cells transfected with negative control siRNA (Nega). The statistical significance of differences between groups was determined by Dunnett's test. ***: p < .001 (STC) versus (Nega)

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that STC1 is expressed at the basal layer of the epidermal layer and plays an autocrine role in maintaining MMP1 expression in epidermal cells. It also downregulates the expression of matrix‐related genes in dermal fibroblasts. These results are consistent with the idea that STC1 is an epidermal secretory factor that plays a negative regulatory role in modulating the condition of the dermal matrix.

Although STC1 is expressed in healthy subjects, it could also have a pathological role. Secretory factors that are increased in wound healing, tumor invasion, and psoriasis have been investigated, but stably secreted factors could also have a significant role in these diseases; for example, the concentration of such a factor could be locally increased due to an increase of the epidermal layer, as seen in the rete ridges or in psoriasis. Furthermore, the dermal layer is separated from the epidermal layer by the basal membrane, which regulates communication between the two layers. Thus, when basement membrane is impaired, such as during wound healing or tumor invasion, cytokines may directly act on the dermal layer even if their concentration is unchanged. Therefore, STC1 could be an important player in dermal–epidermal interaction in various situations.

SCC cells have been reported to increase MMP1 in the adjacent dermal layer.24 Although the factor(s) mediating this action has not been identified, it is known that the JNK–AP1 pathway is induced in dermal fibroblasts.17 These results are consistent with our findings in this study that STC1 activates the JNK–AP1 pathway to induce MMP1 in dermal fibroblasts. A further study is needed to confirm the intracellular signaling pathway of STC1 in SCC, but our results suggest that STC1 may be a key regulator of MMP1. These findings, together with the decreasing effect of STC1 on expression of collagen and elastin in the dermal layer, suggest that STC1 plays a central role in epidermal expansion into the dermal layer, as seen in SCC invasion and psoriasis.

Stratafin, interferon, and CXCL5 have already been identified as mediators of epidermal–dermal interaction,25 and our present results indicate that STC1 can be added to this list. It is noteworthy that the epidermal layer induces aberrant angiogenesis in the dermal layer in SCC and psoriasis and during wound healing,26 and STC1 has been reported to induce angiogenesis.12 Thus, targeting STC1 and/or signaling molecules induced by STC1 could be a new therapeutic strategy for controlling diseases involving dysregulation of epidermal and dermal interactions.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Addition of STC1 to HaCaT cells in which STC1 expression had been knocked down with siRNA significantly restored MMP1 expression. HaCaT cells were transfected with siRNA for STC1 (si), or not transfected (Cont). In another group (si + STC), 10 μg/mL STC1 was added to HaCaT cells at the same time point as siRNA transfection. The MMP1 mRNA abundance in each group after 48 h was expressed as mean ± S.E.M. of 3 wells. The statistical significance of differences between groups was determined by means of the Tukey–Kramer test*: p < 0.05 compared with si, **: p < .001 compared with Cont.

Figure S2 Normal human epidermal cells regulate dermal fibroblast matrix‐related gene expression in the same manner as HaCaT cells in the coculture system. Dermal fibroblasts were cocultured with or without normal human epidermal cells in Transwells. After 2 days of coculture, the abundance of (a) MMP1 was increased, and that of (b) collagen1A1 and (c) elastin mRNAs was decreased in dermal fibroblasts in the coculture (KC), compared with that of fibroblasts cultured alone (Cont). The statistical significance of differences between groups was determined by means of Student's test. ***: p < .001 (Cont) vs. (KC).

Ezure T, Amano S. Stanniocalcin‐1 mediates negative regulatory action of epidermal layer on expression of matrix‐related genes in dermal fibroblasts. BioFactors. 2019;45:944–949. 10.1002/biof.1547

REFERENCES

- 1. Ghaffari A, Kilani RT, Ghahary A. Keratinocyte‐conditioned media regulate collagen expression in dermal fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:340–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ghahary A, Ghaffari A. Role of keratinocyte‐fibroblast cross‐talk in development of hypertrophic scar. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15(Suppl 1):S46–S53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rohani MG, Parks WC. Matrix remodeling by MMPs during wound repair. Matrix Biol. 2015;44‐46:113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ghaffari A, Li Y, Karami A, Ghaffari M, Tredget EE, Ghahary A. Fibroblast extracellular matrix gene expression in response to keratinocyte‐releasable stratifin. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:383–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chavez‐Munoz C, Hartwell R, Jalili RB, et al. SPARC/SFN interaction, suppresses type I collagen in dermal fibroblasts. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113:2622–2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bernat‐Peguera A, Simon‐Extremera P, da Silva‐Diz V, et al. PDGFR‐induced autocrine SDF‐1 signaling in cancer cells promotes metastasis in advanced skin carcinoma. Oncogene. 2019;38:5021–5037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yoshiko Y, Aubin JE. Stanniocalcin 1 as a pleiotropic factor in mammals. Peptides. 2004;25:1663–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sarapio E, Souza SK, Vogt EL, et al. Effects of stanniocalcin hormones on rat brown adipose tissue metabolism under fed and fasted conditions. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2019;485:81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kanellis J, Bick R, Garcia G, et al. Stanniocalcin‐1, an inhibitor of macrophage chemotaxis and chemokinesis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F356–F362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McCudden CR, Majewski A, Chakrabarti S, Wagner GF. Co‐localization of stanniocalcin‐1 ligand and receptor in human breast carcinomas. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;213:167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jiang WQ, Chang AC, Satoh M, Furuichi Y, Tam PP, Reddel RR. The distribution of stanniocalcin 1 protein in fetal mouse tissues suggests a role in bone and muscle development. J Endocrinol. 2000;165:457–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zlot C, Ingle G, Hongo J, et al. Stanniocalcin 1 is an autocrine modulator of endothelial angiogenic responses to hepatocyte growth factor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47654–47659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Du YZ, Gu XH, Li L, Gao F. The diagnostic value of circulating stanniocalcin‐1 mRNA in non‐small cell lung cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2011;104:836–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shirakawa M, Fujiwara Y, Sugita Y, et al. Assessment of stanniocalcin‐1 as a prognostic marker in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2012;27:940–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cornmark L, Lonne GK, Jogi A, Larsson C. Protein kinase Calpha suppresses the expression of STC1 in MDA‐MB‐231 breast cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2011;32:1023–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chang AC, Doherty J, Huschtscha LI, et al. STC1 expression is associated with tumor growth and metastasis in breast cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2015;32:15–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ma X, Gu L, Li H, et al. Hypoxia‐induced overexpression of stanniocalcin‐1 is associated with the metastasis of early stage clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2015;13:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ahmed SA, Gogal RM Jr, Walsh JE. A new rapid and simple non‐radioactive assay to monitor and determine the proliferation of lymphocytes: An alternative to [3H]thymidine incorporation assay. J Immunol Methods. 1994;170:211–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ezure T, Amano S. Negative regulation of dermal fibroblasts by enlarged adipocytes through release of free fatty acids. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:2004–2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sato Y, Mukai K, Watanabe S, Goto M, Shimosato Y. The AMeX method. A simplified technique of tissue processing and paraffin embedding with improved preservation of antigens for immunostaining. Am J Pathol. 1986;125:431–435. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hwang BM, Noh EM, Kim JS, et al. Curcumin inhibits UVB‐induced matrix metalloproteinase‐1/3 expression by suppressing the MAPK‐p38/JNK pathways in human dermal fibroblasts. Exp Dermatol. 2013;22:371–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Qin Z, Voorhees JJ, Fisher GJ, Quan T. Age‐associated reduction of cellular spreading/mechanical force up‐regulates matrix metalloproteinase‐1 expression and collagen fibril fragmentation via c‐Jun/AP‐1 in human dermal fibroblasts. Aging Cell. 2014;13:1028–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Park B, Hwang E, Seo SA, Cho JG, Yang JE, Yi TH. Eucalyptus globulus extract protects against UVB‐induced photoaging by enhancing collagen synthesis via regulation of TGF‐beta/Smad signals and attenuation of AP‐1. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2018;637:31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hakelius M, Koskela A, Ivarsson M, et al. Keratinocytes and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells regulate urokinase‐type plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor‐1 in fibroblasts. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:3113–3118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reichert O, Kolbe L, Terstegen L, et al. UV radiation induces CXCL5 expression in human skin. Exp Dermatol. 2015;24:309–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Armstrong AW, Voyles SV, Armstrong EJ, Fuller EN, Rutledge JC. Angiogenesis and oxidative stress: Common mechanisms linking psoriasis with atherosclerosis. J Dermatol Sci. 2011;63:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Addition of STC1 to HaCaT cells in which STC1 expression had been knocked down with siRNA significantly restored MMP1 expression. HaCaT cells were transfected with siRNA for STC1 (si), or not transfected (Cont). In another group (si + STC), 10 μg/mL STC1 was added to HaCaT cells at the same time point as siRNA transfection. The MMP1 mRNA abundance in each group after 48 h was expressed as mean ± S.E.M. of 3 wells. The statistical significance of differences between groups was determined by means of the Tukey–Kramer test*: p < 0.05 compared with si, **: p < .001 compared with Cont.

Figure S2 Normal human epidermal cells regulate dermal fibroblast matrix‐related gene expression in the same manner as HaCaT cells in the coculture system. Dermal fibroblasts were cocultured with or without normal human epidermal cells in Transwells. After 2 days of coculture, the abundance of (a) MMP1 was increased, and that of (b) collagen1A1 and (c) elastin mRNAs was decreased in dermal fibroblasts in the coculture (KC), compared with that of fibroblasts cultured alone (Cont). The statistical significance of differences between groups was determined by means of Student's test. ***: p < .001 (Cont) vs. (KC).