Abstract

Hormone receptor (HR) negative breast cancers are relatively more common in low-risk than high-risk countries and/or populations. However, the absolute variations between these different populations are not well established given the limited number of cancer registries with incidence rate data by breast cancer subtype. We, therefore, used two unique population-based resources with molecular data to compare incidence rates for the ‘intrinsic’ breast cancer subtypes between a low-risk Asian population in Malaysia and high-risk non-Hispanic white population in the National Cancer Institute’s surveillance, epidemiology, and end results 18 registries database (SEER 18). The intrinsic breast cancer subtypes were recapitulated with the joint expression of the HRs (estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor) and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2). Invasive breast cancer incidence rates overall were fivefold greater in SEER 18 than in Malaysia. The majority of breast cancers were HR-positive in SEER 18 and HR-negative in Malaysia. Notwithstanding the greater relative distribution for HR-negative cancers in Malaysia, there was a greater absolute risk for all subtypes in SEER 18; incidence rates were nearly 7-fold higher for HR-positive and 2-fold higher for HR-negative cancers in SEER 18. Despite the well-established relative breast cancer differences between low-risk and high-risk countries and/or populations, there was a greater absolute risk for HR-positive and HR-negative subtypes in the US than Malaysia. Additional analytical studies are sorely needed to determine the factors responsible for the elevated risk of all subtypes of breast cancer in high-risk countries like the United States.

Keywords: Breast cancer, intrinsic subtypes, SEER, incidence rates

Introduction

Breast cancer incidence overall is known to vary within and across geographic locations and/or ethnic groups [1], with the highest risks (or rates) occurring in the more economically developed regions of the world and among non-Hispanic white women. Moreover, breast cancers among high-risk countries and/or populations such as in the United States (US) typically have greater relative frequency distributions (fractions or proportions) of hormone receptor (HR)-positive than HR-negative tumors [2, 3]. In contrast, breast cancers among low-risk countries and/or ethnic groups such as certain Asian and African populations trend toward greater fractions of HR-negative subtypes [4, 5, 6, 7].

The factors responsible for these varying relative distributions are not fully known. Given the lack of reliable cancer registry data in many less developed regions, it is uncertain if the relative differences represent absolute differences in the age-standardized or age-specific incidence rates. Therefore, to compare the relative and absolute breast cancer differences in a high-risk and low-risk country, we examined breast cancer subtypes in the US (high-risk) and Malaysia (low-risk).

Invasive female breast cancer case and population data for non-Hispanic whites (NHW) and Asian/Pacific Islanders (API) in the US were obtained from the National Cancer Institute’s surveillance and epidemiology and end results 18 registries database (SEER 18) [8]. Native Asian women in Malaysia were accrued from the Department of Radiotherapy and Oncology (DRO) of the Sarawak General Hospital (SGH), which captures about 93 % of all breast cancer cases in Sarawak [9]. Both SEER and the DRO databases have recorded HR and human epidermal growth factor-2 receptor (HER2) data for the recapitulation of the four so-called ‘intrinsic’ breast cancer subtypes [10, 11].

Patients and methods

There were 1,741 female patients diagnosed with invasive breast cancer from the Department of Radiotherapy (DRO) at Sarawak General Hospital (SGH) in Sarawak, Malaysia from 2003 through 2011. The breast cancer cases were corrected to the expected population total by dividing the observed number in each 5-year age group by 0.93 (the percentage of breast cancer cases in Sarawak that are captured by the DRO). Estimates for the general population at risk in Sarawak were obtained from population quick information web site, Department of Statistics Malaysia (http://statistics.gov.my/). We compared the invasive breast cancer cases among Asians in Sarawak to non-Hispanic White (NHW; n = 352,832), and Asian/Pacific Islander (API; n = 34,218) female breast cancers in SEER 18 (2003–2011) [8], representing about 28 % of the U.S. population. The project was approved by the National Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health of Malaysia and exempted from review by the NIH Office of Human Subject Research Protections since it did not involve interaction with human subjects and/or use of personal identifying information (OHSRP number: 5410).

Pathology

Demographic and tumor characteristics in Malaysia and SEER 18 included age at diagnosis, tumor size, tumor grade, axillary lymph nodal status, hormone receptor expression (HR; estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR)), and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) expression. ER and PR were assessed with immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections, while HER2 expression was determined by IHC and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), as previously described [9]. All IHC staining in Sarawak was done in the central pathology laboratory of SGH. To assess the accuracy of IHC staining for ER and PR expression in Sarawak, S.M.H. confirmed a high degree of agreement among a subset of tumor samples (n = 34). The so-called breast cancer ‘intrinsic’ molecular subtypes were recapitulated with joint HR (ER or PR) and HER2 expression: HR-positive/HER2-negative (luminal A), HR-positive/HER2-positive, HR-negative/HER2-positive (HER2-enriched), and HR-negative/HER2-negative (triple negative) [12, 13]. SEER’s 18 registries database collected ER and PR data for our entire study period but did not begin to record HER2 expression until 2010 [8].

Statistical analysis

Incidence rates for Malaysia and SEER 18 were age standardized to the 2000 US standard population by the direct method. We quantified the temporal trend in the age-standardized rate (ASR) with the estimated annual percentage change (EAPC) in the ASR. Age-specific incidence rates were calculated and plotted on a log-linear scale by thirteen 5-year age groups and one group for all women 85+ years (i.e., ages 20–24, 25–29, ⋯, 80–84, and 85+ years). The differences in incidence rates by breast cancer subtype and ethnicity/race were quantified by incidence rate ratios (IRRs), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) with IRR for NHW women assigned as the reference racial group (IRR NHW = 1.0). Separate IRRs were calculated for age groups (20–39, 40–69, and 70–89). All p values were two-sided and considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 11.2 (Statacorp, College Station, TX) and MATLAB® R2012b (The MathWorks Inc., MA).

Results

Median ages at diagnosis were 62 years, 56 years, and 50 years for NHW, API, and Malaysian women, respectively (Table 1, p < 0.001). The relative frequency distributions of all tumor characteristics were significantly different in SEER 18 and Malaysia (p < 0.001), except for tumor grade. Breast cancers were larger at diagnosis with more lymph node positive and ER-negative disease in Malaysia. For women with known hormone receptor (HR) expression, more than 70 % were HR-positive in SEER 18 and nearly 60 % HR-negative in Malaysia.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for select clinicopathologic features among female breast cancer cases in Sarawak, Malaysia (2003–2011) and SEER 18 Cancer Registry (2003–2011)

| NHW, SEER 18 | API, SEER 18 | Sarawak, Malaysia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | n = 352,832 | Column, % | n = 34,218 | Column, % | P-valuea | n = 1,741 | Column, % | P-valueb |

| Age range | 2–114 | 17–108 | 19–91 | |||||

| Median age | 62 | 56 | 50 | |||||

| Variable | N | N | N | |||||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||||||

| <40 | 13,647 | 3.9 | 2,589 | 7.6 | <0.001 | 223 | 12.8 | <0.001 |

| 40–49 | 53,890 | 15.3 | 8,006 | 23.4 | 609 | 35 | ||

| 50–59 | 81,783 | 23.2 | 9,366 | 27.4 | 530 | 30.4 | ||

| ≥60 | 203,512 | 57.7 | 14,257 | 41.7 | 379 | 21.8 | ||

| Tumor size | ||||||||

| ≤2 cm | 205,103 | 65.3 | 18,469 | 60.0 | <0.001 | 330 | 19.1 | <0.001 |

| >2 cm | 109,172 | 34.7 | 12,401 | 40.0 | 1,395 | 80.9 | ||

| Unknown/In situ | 38,557 | ~ | 3,348 | ~ | 16 | ~ | ||

| Tumor grade | ||||||||

| Low grade | 215,862 | 67.2 | 19,565 | 61.8 | <0.001 | 1,164 | 69.4 | 0.05 |

| High grade | 105,388 | 32.8 | 12,077 | 38.2 | 513 | 30.6 | ||

| Unknown | 31,582 | ~ | 2,576 | ~ | 64 | ~ | ||

| Node status | ||||||||

| Negative | 224,901 | 68.6 | 21,564 | 67.2 | <0.001 | 745 | 43.7 | <0.001 |

| Positive | 103,176 | 31.4 | 10,523 | 32.8 | 959 | 56.3 | ||

| Unknown | 24,755 | ~ | 2,131 | ~ | 37 | ~ | ||

| ER expression | ||||||||

| Negative | 58,975 | 18.3 | 6,493 | 20.4 | <0.001 | 973 | 57.5 | <0.001 |

| Positive | 263,964 | 81.7 | 25,323 | 79.6 | 718 | 42.5 | ||

| Unknown | 29,893 | ~ | 2,402 | ~ | 50 | ~ | ||

| Tumor subtypec | ||||||||

| HR +/HER2− | 53,784 | 75.8 | 5,682 | 71.4 | <0.001 | 722 | 47.5 | <0.001 |

| HR+/HER2+ | 6,792 | 9.6 | 967 | 12.1 | 230 | 15.1 | ||

| HR−/HER2+ | 2,835 | 4.0 | 535 | 6.7 | 204 | 13.4 | ||

| HR−/HER2− | 7,577 | 10.7 | 779 | 9.8 | 364 | 23.9 | ||

| Unknown | 8,423 | ~ | 918 | ~ | 221 | ~ | ||

Abbreviations API Asian or Pacific Islander, NHW Non-Hispanic white, ER Estrogen receptor, HR Hormone receptor (includes estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor), HER2 Human epidermal growth factor receptor-2. Column percentages are calculated using only patients with available data; ~, not calculated

P value calculated using Chi-square tests comparing a API or b Malaysian frequency distributions to NHW women

In SEER18, the tumor marker data used to create the tumor subtype categories are only available for the years 2010 and 2011

Age-standardized incidence rates (ASRs)

The ASRs for breast cancer overall ranged from 180.6 to 125.0 to 36.2 per 100,000 among NHW, API, and Malaysian women, respectively (Table 2). The ASRs varied more for ER-positive than ER-negative breast cancers. ER-positive incidence rates were nearly 7-fold greater between NHW than Malaysian women and only 2-fold greater for ER-negative cancers between NHW and Malaysian women.

Table 2.

Age-standardized breast cancer incidence rates (ASR) and estimated annual percent change in the ASR among women in SEER 18 and Sarawak, Malaysia overall and by estrogen receptor (ER) expression

| SEER NHW, 2003–2011 | SEER API, 2003–2011 | Sarawak, 2003–2011 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASR (SD) | EAPC (95 % CI) | ASR (SD) | EAPC (95 % CI) | ASR (SD) | EAPC (95 % CI) | |

| Overall | 180.6 (0.31) | −0.27 % (−0.43 to −0.12) | 125.0 (0.68) | 0.65 % (0.14 to 1.16) | 36.2 (20.3) | 3.44 % (1.13 to 5.80) |

| ER+ | 134.8 (0.27) | 2.03 % (1.84 to 2.22) | 92.7 (0.59) | 2.85 % (2.24 to 3.45) | 20.3 (0.64) | 6.66 % (3.45 to 9.96) |

| ER− | 31.2 (0.13) | −2.55 % (−2.93 to −2.17) | 23.4 (0.29) | −2.03 % (−3.17 to −0.88) | 14.8 (0.55) | 1.46 % (−2.10 to 5.14) |

Age-standardized incidence rates (ASR) per 100,000 woman-years were calculated using the 2000 US Standard population. Estimated annual percent change (EAPC) in the ASR per year and 95 % confidence intervals were calculated by weighted log-linear regression. Abbreviations API Asian or Pacific Islander, NHW Non-Hispanic white, ER Estrogen receptor

For breast cancer overall, the estimated annual percent change (EAPC) in the ASR decreased slightly for NHW and rose modestly for API women in the US (Table 2). Conversely, in Malaysia, the EAPC rose 3.44 % per year (95 % CI: 1.13 to 5.80 %/year). The EAPCs for ER-positive and ER-negative breast cancers diverged in SEER 18 as previously described [14], i.e., ER-positive cancers rose while ER-negative cancers declined for NHW and API women. More specifically, we observed an annual rise of about 2 % for ER-positive breast cancers in SEER 18 compared to a sharper annual increase of 6.7 % in Malaysia. There also was a non-significant rise for ER-negative breast cancers in Malaysia.

Age-specific incidence rates by ER expression

Age-specific incidence rates for ER-negative breast cancers rose rapidly until age 50 years then flattened among US women (Fig. 1a–b); whereas rates for ER-positive cancers continued to rise, albeit at a slower pace after age 50 years. On the other hand, in Malaysia, age-specific rates flattened after age 50 years irrespective of ER expression (Fig. 1c). Incidence rates of ER-negative breast cancer were highest for NHWs peaking near 60, 40, and 30 per 100,000 woman-years among NHW, API, and Malaysian women, respectively; whereas ER-positive rates peaked near 400, 200, and 30 per 100,000.

Fig. 1.

Age-specific incidence rates per 100,000 woman-years (or women per year) comparing women in Sarawak, Malaysia to the National Cancer Institute’s surveillance, epidemiology, and end results 18 registries database (SEER 18), stratified by estrogen receptor (ER) expression. a Non-Hispanic white (NHW) women in SEER 18 for the years 2003–2011 b Asian/Pacific Islander (API) women in SEER 18 for the years 2003–2011 c Malaysian women in Sarawak, cases restricted to the years 2003–2011

Age-specific incidence rates and rate ratios by molecular subtype

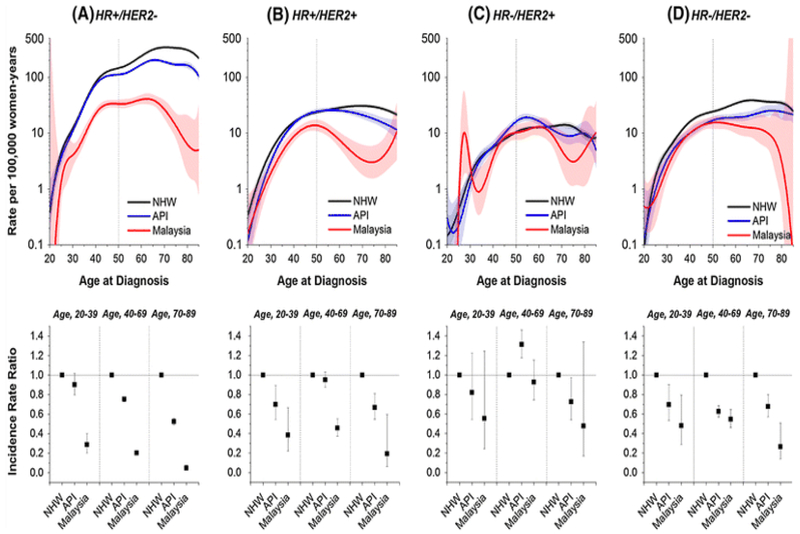

Age-specific incidence rates (Fig. 2, upper panels) and incidence rate ratios (IRRs, Fig. 2 lower panels) were stratified by molecular subtype and ethnicity. Age-specific rates for HR-positive/HER2-positive, HR-negative/HER2-positive (HER2-enriched), and HR-negative/HER2-negative (triple negative) cancers rose rapidly until age 50 years then flattened or fell irrespective of geographic location and/or ethnic group (Fig. 2b–d, upper panels), similar to what was seen for ER-negative cancers in Fig. 1a–c. In contrast, rates continued to rise after age 50 years for HR-positive/HER2-negative (Fig. 2a, upper panels), though less for Malaysian than NHW and API women. IRRs by molecular subtype generally declined from NHW to API to Malaysian women irrespective of age group (Fig. 2, lower panels), except for HR-negative/HER2-positive cancers. Notably, for these HER2-enriched breast cancers, the IRR was greater for API than NHW at ages 40–69 years.

Fig. 2.

Age-specific incidence rates per 100,000 woman-years (or women per year) and incidence rate ratios and 95 % confidence intervals comparing women in Sarawak, Malaysia and US Asian/Pacific Islanders (API) to non-Hispanic white (NHW) in SEER18, stratified by molecular subtype defined as a HR-positive/HER2-negative (HR +/HER2−; ER or PR positive and HER2 negative) cases for NHW, API women in SEER18 (restricted to 2010–2011), and Sarawak, Malaysia data (restricted to the years 2008–2011); b HR-positive/HER2-positive (HR +/HER2 + ; ER or PR positive and HER2 positive) cases; c HR-negative/HER2-positive (HR−/HER2 + ; ER and PR negative and HER2 positive) cases; d HR-negative/HER2-negative (HR−/HER2−; ER, PR and HER2 negative) cases

Discussion

In this study, we compared the relative and absolute breast cancer incidence rates (risks) among women in the Sarawak state of Malaysia and the United States SEER 18 registries database. Consistent with previous reports from low-risk native Asian populations [15], we found a higher proportion of HR-negative breast cancers in Malaysia. However, the observed relative differences did not translate into higher absolute risks (incidence rates) for any of the four so-called ‘intrinsic’ breast cancer subtypes. For example, the incidence rate for every subtype in all age groups was the highest among NHW, followed by API, and then Malaysian women.

The one exception was HR-negative/HER2-positive (HER2-enriched) cancers among API populations at ages 40–69 years, which is consistent with other studies among Asian women [13, 16, 17, 18]. Notably, the incidence rate for the HR-negative/HER2-positive subtypes in Sarawak also reached the NHW rate at ages 40–69 years. In total, these observations suggest that Asian women may have an inherently greater risk for HER2-enriched breast cancer.

Long gone are the days where breast cancer overall can be considered a single disease. The distinct age-specific incidence rates suggest different age-associated etiologies for the different breast cancer subtypes. Risk factors that are more prevalent in high-risk populations such as high dietary fat intake, nulliparity, late age at first birth, and post-menopausal obesity are more strongly associated with the risk of HR-positive than HR-negative disease [19, 20]. These observations may partially explain the disproportionally large incidence gap for HR-positive subtypes among NHW women in the US and Asian women in Sarawak. The presence of population-based mammographic screening in the US and its absence in Malaysia may also contribute to the incidence differences particularly for HR-positive subtypes, given that screening has a greater sensitivity for HR-positive than HR-negative breast cancer [21]. Risk factors for HR-negative subtypes are less clear, though a recent analysis from the African American breast cancer epidemiology and risk (AMBER) consortium showed that parity with lack of breast feeding was a risk factor for HR-negative subtypes, especially HR-/HER2- (triple negative) cancers [22]. Nonetheless, even though all of the risk factor profiles for the various breast cancer subtypes are not completely known, this study suggests that the exposures for all subtypes are elevated among women in the US.

Analogous to the women in Malaysia, breast cancer among women in sub-Saharan Africa often report a higher prevalence of HR-negative breast cancer compared to Western countries [4, 23, 24]. These findings have led researchers to conclude that traditionally “low-risk” countries are at “high-risk” for the more aggressive HR-negative cancers. However, most all of these analyses generally have relied upon relative frequency distributions rather than population-based age-adjusted or age-specific incidence rates, and therefore, may not reflect absolute risk differences.

Our study is not without limitations. Calculations of incidence rates in Sarawak were based on hospital cases, which may not represent the total breast cancer population in Sarawak. However, the numbers of cases treated in SGH and reported by Sarawak cancer registry are very similar, [9] suggesting near total case ascertainment. Also, molecular marker data were not available for Malaysian cases diagnosed before 2003; and therefore, our analysis is limited to the most recent decade. Similarly, SEER 18 analysis by molecular subtype was restricted to the 2010 and 2011 collection period. Finally, there are several ethnic groups in Sarawak with distinct lifestyles and breast cancer subtype distributions, especially between Chinese and non-Chinese women [9]. However, our study was not powered to investigate the incidence and survival patterns by molecular subtype and ethnicity. Major strengths of our study are the molecular characterization of tumors and the population-based case collection that enabled us to calculate the absolute incidence rates by breast cancer subtypes. These unique data in Sarawak, Malaysia are being compared to the US SEER 18 dataset with available HER2 expression, which to our knowledge have not previously been used to compare across different geographic locations. Our findings highlight the importance of using a rate-based approach when comparing cancers between different geographic locations and/or ethnic groups.

In summary, our evaluation shows a greater absolute risk for all subtypes of breast cancer among women in the US compared to Asian women in a low-risk country like Malaysia. If our results are generalizable, other low-risk countries and/or populations may be at lower absolute risk for HR-negative as well as HR-positive breast cancers. Finally, additional research is sorely needed to determine why women in high-risk populations and/or countries like NHW in the US are at greater risk for all subtypes of breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Pathology Department of Sarawak General Hospital and Ms. Rokia Iren for their assistance in tissue block retrieval. Research support Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NCI, DCEG.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM (2010) Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF (2006) Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer rates in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol 24(14):2137–2150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray F, Jemal A, Grey N, Ferlay J, Forman D (2012) Global cancer transitions according to the human development index (2008-2030): a population-based study. Lancet Oncology 13(8):790–801. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70211-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huo D, Ikpatt F, Khramtsov A, Dangou JM, Nanda R, Dignam J, Zhang B, Grushko T, Zhang C, Oluwasola O, Malaka D, Malami S, Odetunde A, Adeoye AO, Iyare F, Falusi A, Perou CM, Olopade OI (2009) Population differences in breast cancer: survey in indigenous African women reveals over-representation of triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 27(27):4515–4521. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.6873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhikoo R, Srinivasa S, Yu TC, Moss D, Hill AG (2011) Systematic review of breast cancer biology in developing countries (part 1): Africa, the middle East, Eastern Europe, Mexico, the Caribbean and South America. Cancers 3(2):2358–2381. doi: 10.3390/cancers3022358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhikoo R, Srinivasa S, Yu TC, Moss D, Hill AG (2011) Systematic review of breast cancer biology in developing countries (part 2): Asian subcontinent and South East Asia. Cancers 3(2):2382–2401. doi: 10.3390/cancers3022382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howlader N, Altekruse SF, Li CI, Chen VW, Clarke CA, Ries LAG, Cronin KA (2014) US Incidence of breast cancer subtypes defined by joint hormone receptor and HER2 status. J Natl Cancer Inst 106(5):dju055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.SEER-18 (2014) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 18 Regs Research Data + Hurricane Katrina Impacted Louisiana Cases, Nov 2013 Sub (2000-2011) < Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment > - Linked To County Attributes - Total U.S., 1969-2012 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Surveillance Systems Branch, released April 2014 (updated 5/7/2014), based on the November 2013 submission www.seer.cancer.gov [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devi CR, Tang TS, Corbex M (2012) Incidence and risk factors for breast cancer subtypes in three distinct South-East Asian ethnic groups: Chinese, Malay and natives of Sarawak. Malaysia. Int J Cancer 131(12):2869–2877. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA, Fluge O, Pergamenschikov A, Williams C, Zhu SX, Lonning PE, Borresen-Dale AL, Brown PO, Botstein D (2000) Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 406(6797):747–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sorlie T, Tibshirani R, Parker J, Hastie T, Marron JS, Nobel A, Deng S, Johnsen H, Pesich R, Geisler S, Demeter J, Perou CM, Lonning PE, Brown PO, Borresen-Dale AL, Botstein D (2003) Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100(14):8418–8423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nielsen TO, Hsu FD, Jensen K, Cheang M, Karaca G, Hu Z, Hernandez-Boussard T, Livasy C, Cowan D, Dressler L, Akslen LA, Ragaz J, Gown AM, Gilks CB, van de Rijn M, Perou CM (2004) Immunohistochemical and clinical characterization of the basal-like subtype of invasive breast carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 10(16):5367–5374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke CA, Keegan TH, Yang J, Press DJ, Kurian AW, Patel AH, Lacey JV Jr (2012) Age-specific incidence of breast cancer subtypes: understanding the black-white crossover. J Natl Cancer Inst 104(14):1094–1101. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson WF, Katki HA, Rosenberg PS (2011) Breast cancer incidence in the United States: current and future trends. J Natl Cancer Inst 103(18):1397–1402. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez SL, Quach T, Horn-Ross PL, Pham JT, Cockburn M, Chang ET, Keegan TH, Glaser SL, Clarke CA (2010) Hidden breast cancer disparities in asian women: disaggregating incidence rates by ethnicity and migrant status. Am J Public Health 100(Suppl 1):S125–S131. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yau TK, Sze H, Soong IS, Hioe F, Khoo US, Lee AW (2008) HER2 overexpression of breast cancers in Hong Kong: prevalence and concordance between immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridisation assays. Hong Kong Acad Med 14(2):130–135 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao J, Liu H, Wang M, Gu L, Guo X, Gu F, Fu L (2009) Characteristics and prognosis for molecular breast cancer subtypes in Chinese women. J Surg Oncol 100(2):89–94. doi: 10.1002/jso.21307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan YO, Han S, Lu YS, Yip CH, Sunpaweravong P, Jeong J, Caguioa PB, Aggarwal S, Yeoh EM, Moon H (2010) The prevalence and assessment of ErbB2-positive breast cancer in Asia: a literature survey. Cancer 116(23):5348–5357. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma H, Wang Y, Sullivan-Halley J, Weiss L, Marchbanks PA, Spirtas R, Ursin G, Burkman RT, Simon MS, Malone KE, Strom BL, McDonald JA, Press MF, Bernstein L (2010) Use of four biomarkers to evaluate the risk of breast cancer subtypes in the women’s contraceptive and reproductive experiences study. Cancer Res 70(2):575–587. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bianchini F, Kaaks R, Vainio H (2002) Overweight, obesity, and cancer risk. Lancet Oncol 3(9):565–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porter PL, El-Bastawissi AY, Mandelson MT, Lin MG, Khalid N, Watney EA, Cousens L, White D, Taplin S, White E (1999) Breast tumor characteristics as predictors of mammographic detection: comparison of interval- and screen-detected cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 91(23):2020–2028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmer JR, Viscidi E, Troester MA, Hong CC, Schedin P, Bethea TN, Bandera EV, Borges V, McKinnon C, Haiman CA, Lunetta K, Kolonel LN, Rosenberg L, Olshan AF, Ambrosone CB (2014) Parity, lactation, and breast cancer subtypes in African American women: results from the AMBER consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCormack VA, Joffe M, van den Berg E, Broeze N, Silva Idos S, Romieu I, Jacobson JS, Neugut AI, Schuz J, Cubasch H (2013) Breast cancer receptor status and stage at diagnosis in over 1,200 consecutive public hospital patients in Soweto, South Africa: a case series. Breast Cancer Res 15(5):R84. doi: 10.1186/bcr3478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stark A, Kleer CG, Martin I, Awuah B, Nsiah-Asare A, Takyi V, Braman M, Quayson SE, Zarbo R, Wicha M, Newman L (2010) African ancestry and higher prevalence of triple-negative breast cancer: findings from an international study. Cancer 116(21):4926–4932. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]