Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To identify factors associated with nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) American Urological Association (AUA) guideline compliance in a rural state, to evaluate compliance rates over time, and to assess the impact of patient and provider rurality on delivery of NMIBC care.

METHODS

We identified 847 Iowans in Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare from 1992 to 2009 with high-grade NMIBC who survived 2 years and were not treated with cystectomy or radiation during this period. Compliance with AUA guidelines was assessed over time and compared to patient demographic, tumor, and treatment institution variables. Impact of rurality was analyzed using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results ZIP code data travel distance of patient to nearest urologist practice location.

RESULTS

Overall compliance with AUA guidelines was low (<1%), and did not markedly improve over the study period. In the multivariable model, only care at an academic medical center (OR 11.68, 95% CI 7.07–19.29) and tumor stage (Tis; OR 3.24, 95% CI 1.86–5.63) increased the odds of compliance. Patients living closer (<10 miles) to their urologists underwent more cystoscopies than patients living further (>30 miles) but distance did not affect compliance with other measures. Compliance was not associated with cancer-specific survival.

CONCLUSION

Compliance with post-Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumor (TURBT) NMIBC treatment guidelines has improved but remains suboptimal in our rural state, and is highly associated with treatment at an academic cancer center for reasons that could not be fully explained with these data.

Bladder cancer represents the second most common urologic malignancy1 and the most expensive cancer on a per patient basis.2,3 Patients with high grade nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) are challenging to manage with a reported recurrence rate of 55%–63% at 2 years and a significant risk of progression to muscle-invasive disease.4 Interventions to improve bladder cancer outcomes include the use of intravesical therapy as well as cystoscopic and upper tract surveillance which require significant coordination of care to deliver.

The American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines for NMIBC management were first released in 1999.5,6 In 2012, Chamie et al reported that from 1992 to 2002, a period of time where best practices for NMIBC were known but the guidelines had not been released, overall compliance with the recommendations was poor.7 Still, greater compliance was found to be associated with increased bladder cancer survival, adding guideline validity. Since their original release, the guidelines have been updated 3 times, but a population level analysis of how these guidelines have affected contemporary NMIBC management has not been repeated.

The purpose of the present study was to retrospectively evaluate state-wide compliance with the AUA NMIBC guidelines with the goal of utilizing the results to aid in developing a bladder cancer treatment network in the state of Iowa. Unlike the study performed by Chamie et al,7 our study focused on only one state, allowing us to merge unique hospital and provider level data with Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare data, adding geographic data on access to care to the procedural coding. In addition, Iowa is a mostly rural state with over 30% of the population living in rural counties and nearly half of the population living over 30 miles from the nearest urology practice.8 Our analysis included the impact of patient rurality and distance to provider on the of NMIBC treatment. We hypothesized that patients in rural counties, further from urologic care, would receive less intensive treatment and surveillance. Additional hypotheses included improved guideline compliance over time within the state, and association of compliance with improved cancer-specific survival.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Cohort

The study was exempt from Institutional Review Board approval after obtaining a data use agreement. Using the National Cancer Institute SEER-Medicare linkage, the patient cohort com- prised Iowans aged ≥66 years when diagnosed with NMIBC (Supplementary Fig. 1). NMIBC was diagnosed between January 1, 1992 and December 31, 2009 and defined as high grade (ie, poorly differentiated and undifferentiated), AJCC Stage 0/I bladder cancer (ICDO-3: C67.0-C67.9) with urothelial histology (ICD-O-3: 8120, 8130). Patients were limited to age ≥66 years because they were required to have Medicare Parts A and B, and no Health Maintenance Organization coverage in the 12 months prior to diag- nosis (so that comorbid conditions could be identified) and the 24 months following diagnosis (to assess compliance with treatment guidelines). About 4863 patients initially met our inclusion criteria. Additional exclusion criteria included death or loss to follow-up less than 24 months following diagnosis, evidence of treatment with partial/radical cystectomy or radiation (113 patients), missing month of diagnosis, and lack of claims during the month of diagnosis (Supplementary Fig. 1). We did not exclude cases based on comorbid or subsequent disease, specifically upper tract disease. Medicare claims were available for Iowa cancer patients who received care in other states. Where care was received was defined based on SEER-Medicare standards. The affiliation with a medical school gave the practice an academic designation, and only National Cancer Institute comprehensive cancer centers had a cancer center designation.

Study Outcome Compliance Variables

Compliance with the AUA NMIBC guidelines was measured as previously described by Chamie et al using the procedural codes listed in Supplementary Table 1.7 Perfect compliance with AUA guidelines for the 2 years following initial diagnosis of NMIBC would have meant that cystoscopy was performed 8 times (every 3 months), cytology 8 times (every 3 months), upper tract imaging at least once, perioperative intravesical instillation of Mitomycin C after initial resection (minimum of once), and 6 intravesical induction Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) treatments. As full compliance with published guidelines was shown to be exceed-ingly rare, for the purposes of the study, and in line with the original Chamie et al analysis, we utilized compliance with “relaxed guidelines” as an outcome measure, defined as ≥4 cystoscopies, ≥4 cytologies, ≥6 BCG treatments in the 2 years following Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumor (TURBT) diagnosis.7

Analysis of Factors Associated With Guideline Compliance

Mixed effects logistic regression models using generalized estimating equations were applied using the outcome of compliance with the relaxed guidelines. An exchangeable correlation structure was used to account for the possible dependency among patients seen at the same facility. Patient, tumor, and care center demographics were initially evaluated in a univariable fashion for their relationship to compliance. Variables are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Covariates used in the analysis were selected a priori based on clinical knowledge and availability.

Estimated effects of associations with compliance were reported as odds ratios (OR) along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Variations, in compliance (both frequency per patient and categorical compliance) over the 3 time-periods (1992–1997 (preguideline era), 1998–2002, and 2003–2009) were assessed using Wilcoxon rank sum and chi-square tests. An inverse probability score weighted Fine and Gray regression model was fit to evaluate cancer-specific survival differences between compliance groups. Propensity scores were derived from a mixed effects logistic regression model adjusting for age, gen- der, metro county, marital status, Charlson score, education, household income, institution type, year of diagnosis, grade, and T classification. Furthermore, a robust sandwich variance estimate was used to account for the possible dependency between patients seen as the same facility. Time was calculated from diagnosis to death due to bladder cancer with nonbladder cancer mortality considered a competing event. Estimated effects are reported as hazard ratios (HRs) along with 95% CIs. All statistical testing was 2-sided and assessed for significance at P<.05 using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Measuring the Effects of Rurality and Distance to Provider on Compliance

The “Iowa Physician Information System database” is a state- wide database maintained by the University of Iowa and used to monitor state physician density, including specialists. This was utilized to determine the distance from each patient to their nearest urology provider (either primary clinic or outreach clinics) utilizing zip code data, MPMileCharter and Microsoft MapPoint with representative centroid data. Dis- tances to nearest available provider were categorized into <10, 10–20, 20–30 and >30 miles and analyzed for the fre- quency of guideline recommended procedures performed per patient over the study period.

RESULTS

The study cohort included 847 Iowans with high grade NMIBC and 2-year surveillance data. The majority of patients were male (77.2%) and married (71.3%). Most patients were treated at a nonacademic center (67.9%). Overall patient demographics and tumor characteristics are shown in Table 1. Almost all patients were white (99%) so race could not be presented in Supplementary Table 2 due to small numbers. Median follow up was 6.08 years (range: 2.08–21.91).

Table 1.

Utilization of guideline recommended services by time period using means and compliance (yes/no) of individual quality measures within 2 years defined as ≥4 cystoscopies, ≥4 cytologies, 1 upper tract imaging, 1 perioperative mitomycin, or ≥6 BCG treatments

| Mean (SD) Services Utilized | Number (%) Compliant | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality-of-care measures | 1992–1997 | 1998–2002 | P* | 2003–2009 | Py | 1992–1997 | 1998–2002 | P* | 2003–2009 | Py |

| Cystoscopy | 4.7 (1.9) | 4.9 (1.8) | .54 | 4.9 (1.7) | .77 | 129 (80.1) | 126 (81.8) | .70 | 444 (83.5) | .63 |

| Upper tract imaging | 1.4 (2.5) | 1.1 (1.6) | .74 | 1.3 (1.7) | .07 | 82 (50.9) | 79 (51.3) | .95 | 303 (57.0) | .21 |

| Mitomycin C | 0.03 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.5) | <.01 | 0.4 (0.7) | <.01 | <11 (<7%) | 17 (11.0) | <.01 | 150 (28.2) | <.01 |

| BCG | 5.6 (7.0) | 6.0 (6.2) | .25 | 6.5 (6.3) | .21 | 72 (44.7) | 86 (55.8) | .05 | 298 (56.0) | .97 |

| Cytology | 1.9 (2.1) | 1.9 (2.2) | .85 | 1.7 (2.1) | .40 | 44 (27.3) | 36 (23.4) | .42 | 123 (23.1) | .95 |

Bold values denotes statistical significance.

P value is the comparison between time periods 1992 and 1997 and 1998 and 2002.

P value is the comparison between time periods 1998 and 2002 and 2003 and 2009.

Over the 3-time periods, only the post-TURBT utilization of perioperative Mitomycin C increased significantly during each period, with 2.5% of the population receiving that therapy in the years 1992–1997 and 28.2% receiving it between 2003 and 2009. BCG compliance also increased from 1992–1997 to 1998–2002, but then plateaued at 56% of the eligible patients during 2003–2009 (Table 1). Overall compliance with the guidelines was poor with fewer than 1% of all patients being fully compliant with AUA guidelines in both study time periods. When the guidelines were relaxed for the overall population (irrespective of time period), as depicted in Table 2, the compliance then “improved.” Overall, 96% of patients had a minimum of 1 post- TURBT cystoscopy in the 2-year follow-up period.

Table 2.

Number of Iowans who received NMIBC care between 1992 and 2009 that were compliant with progressive relaxation of guidelines

| Compliance Criteria | No.* | % |

|---|---|---|

| ≥8 cystoscopies, ≥8 cytologies, ≥6 BCG instillations | <11 | <1% |

| ≥8 cystoscopies, ≥8 cytologies, ≥1 BCG instillations | <11 | <1% |

| ≥4 cystoscopies, ≥4 cytologies, ≥6 BCG instillations | 142 | 16.8 |

| ≥4 cystoscopies, ≥4 cytologies, ≥1 BCG instillation | 160 | 18.9 |

| ≥4 cystoscopies, ≥1 cytology, ≥1 BCG instillation | 313 | 37.0 |

| ≥1 cystoscopy, ≥1 cytology, ≥1 BCG instillation | 339 | 40.0 |

| ≥1 cystoscopy, ≥1 BCG instillation | 550 | 64.9 |

| ≥1 cystoscopy | 813 | 96.0 |

Cells with <11 censored as per SEER/Medicare guidelines.

The univariable and multivariable models for compliance with the relaxed guidelines are shown in Table 3. In both the univariable and multivariable models, only care at an academic medical center (OR 11.68, 95% CI 7.07–19.29 (multivariate)) and tumor stage (Tis; OR 3.24, 95% CI 1.86–5.63)) increased the odds of increased compliance.

Table 3.

Mixed effects model predicting compliance with ≥4 cystoscopies, ≥4 cytologies, and ≥6 BCG treatments

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value |

| Age group, y | ||||||

| 66–69 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 70–74 | 1.05 | 0.60, 1.83 | .87 | 1.02 | 0.59, 1.79 | .93 |

| 75–79 | 0.63 | 0.34, 1.18 | .15 | 0.57 | 0.31, 1.03 | .06 |

| 80+ | 0.51 | 0.26, 1.03 | .06 | 0.53 | 0.28, 1.02 | .06 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1.00 | |||||

| Female | 0.78 | 0.49, 1.24 | .30 | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Other | 0.83 | 0.59, 1.16 | .28 | 0.87 | 0.59, 1.28 | .48 |

| Metro county | ||||||

| Metro | 1.00 | |||||

| Nonmetro | 1.27 | 0.84, 1.92 | .25 | |||

| Charlson score | ||||||

| 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 1 | 0.88 | 0.60, 1.30 | .53 | 0.94 | 0.66, 1.34 | .73 |

| 2 | 1.48 | 0.93, 2.35 | .10 | 1.58 | 0.95, 2.63 | .08 |

| ≥3 | 1.07 | 0.53, 2.14 | .85 | 1.14 | 0.58, 2.25 | .70 |

| Percent of subjects in zip code aged 25+ with ≥4 y of college education | ||||||

| <15% | 1.00 | |||||

| 15%–25% | 1.06 | 0.70, 1.62 | .78 | |||

| 25%–35% | 1.17 | 0.62, 2.21 | .62 | |||

| >35% | 0.78 | 0.52, 1.16 | .22 | |||

| Median zip code household income | ||||||

| <$35,000 | 1.00 | |||||

| $35,000-$45,000 | 1.37 | 0.92, 2.05 | .12 | |||

| $45,000-$55,000 | 1.09 | 0.62, 1.93 | .76 | |||

| >$55,000 | 1.21 | 0.46, 3.21 | .70 | |||

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||

| 1992–1997 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 1998–2002 | 1.42 | 0.69, 2.92 | .34 | 1.25 | 0.61, 2.54 | .54 |

| 2003–2009 | 1.26 | 0.65, 2.44 | .49 | 1.32 | 0.73, 2.38 | .36 |

| Institution type | ||||||

| Nonacademic noncancer center | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Academic noncancer center | 0.92 | 0.44, 1.92 | .83 | 0.93 | 0.44, 1.96 | 0.86 |

| Academic cancer center | 9.31 | 5.60, 15.49 | <.01 | 11.68 | 7.07, 19.29 | <.01 |

| Unknown | 0.48 | 0.11, 2.07 | .32 | 0.50 | 0.12, 2.01 | .33 |

| Grade | ||||||

| Poorly differentiated | 1.00 | |||||

| Undifferentiated | 1.26 | 0.80, 1.99 | .31 | |||

| Classification | ||||||

| Ta | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| T1 | 1.28 | 0.89, 1.83 | .18 | 1.26 | 0.88, 1.79 | .21 |

| Tis | 3.00 | 1.81, 4.99 | <.01 | 3.24 | 1.86, 5.63 | <.01 |

Bold values denotes statistical significance.

A shorter distance to the nearest urologic provider was associated only with more cystoscopies (Supplementary Table 3). On average, patients living >30 miles away from a urology office received 1 fewer cystoscopy during the 2-year follow-up period than patients living <10 miles away.

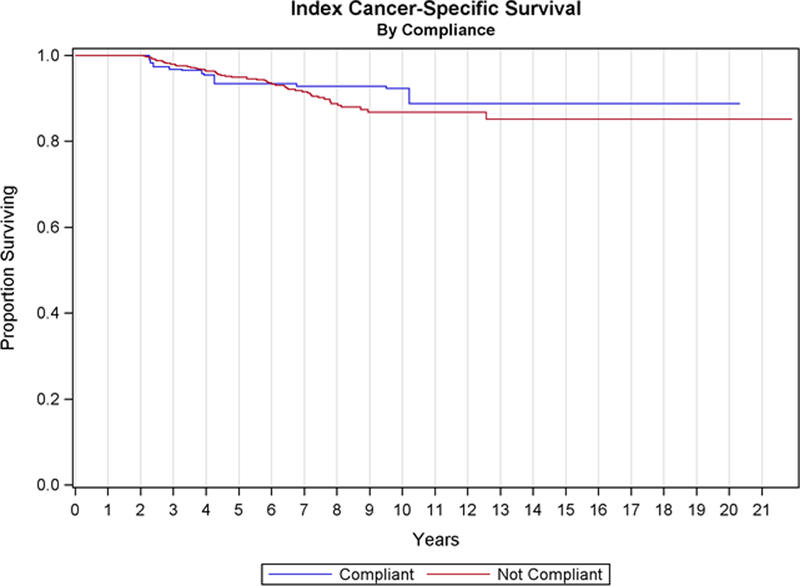

No cancer-specific survival differences were evidenced between patients that were compliant with the relaxed guidelines vs noncompliant patients (HR = 1.00, 95% CI 0.46–2.17, P = 1.00, Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Cancer-specific survival stratified by compliance with relaxed* AUA guidelines.* Relaxed guidelines: >4 cystoscopies, >4 cytologies, >6 BCG treatments in the 2 years following TURBT diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to evaluate changes in compliance with the NMIBC guidelines in the state of Iowa and to identify risk factors associated with noncompliance. We hypothesized that bladder cancer management, as determined by the compliance with AUA guidelines, would improve over the study period. However, with the exception of the perioperative instillation of mitomycin, which increased from 2.5% to just under 30% over the 17-year study period, and BCG instillation, which increased only during the early study period, the utiliza- tion of cystoscopy, cytology, upper tract imaging, and contemporary BCG administration remained statistically unchanged. Only 16.8% of patients were compliant with the “relaxed” AUA guidelines. Patient rurality did not significantly affect compliance other than cystoscopy rates. Compliance was not associated with cancer-specific survival.

The finding of no association with cancer-specific survival is counter to the findings of Chamie et al.7 Prior work has shown that increased intensity of treatment in bladder cancer offered no survival benefits.9 Additionally, data have shown the benefits of intravesical therapy on recurrence but have found no difference in progression or survival.10,11 These results warrant further evaluation in a broader population to better determine the association of survival with the guidelines.

Multivariable analysis demonstrated that the factor most strongly associated with guideline compliance was receiving care at an academic cancer. The only patient factor that was nearly significantly associated with compliance was younger age, and the only tumor characteristic that was significantly associated with compliance was Tis (vs Ta). In addition, our distance analysis showed that living a shorter distance to nearest urology provider was associated with more screening cystoscopies, though not other guideline measures.

The AUA NMIBC guidelines were last updated in 2016 and currently include 38 statements on NMIBC management, of which the majority are level C evidence.6 Chamie et al,7 were the first to critically evaluate NMIBC guideline “compliance” in the years prior to the official guideline publication and noted that nationwide, post-TURBT NMIBC management was both heterogeneous and incomplete. In their analysis, few patients were “fully compliant” with follow-up care—and with the exception of higher age, which predicted worse compliance, factors associated with improved compliance were mostly tumor related, with undifferentiated tumors (vs poorly differentiated) and stage (T1 and T1s vs Ta) leading to more intense postresection NMIBC monitoring.

Compliance with guidelines in the state of Iowa was significantly affected by the affiliation of their treating provider, with patients being managed at academic cancer centers undergoing significantly more intense follow-up care vs nonacademic centers. This is different from the findings of Chamie et al.7 The reasons for this discrepancy are not easily explained by patient or tumor data available in the SEER-Medicare database and specifically not in our study, since our cohort had a limited number in the academic cancer center thus these conclusions may be spurious. However, data are now emerging that show improved mortality and morbidity rates for academic vs nonacademic medical centers for both surgical and medical conditions, thought to be explained, at least in part, by academic centers’ propensity to utilize and comply with evidence-based medicine.12 Further investigation of these discrepancies will be especially important as we continue efforts to improve overall NMIBC compliance within the state. Examples may include improved training of physicians and hospitals in nonacademic centers of NMIBC guideline and the coordination and sharing of resources to improve overall compliance.

The vast majority of Iowa’s land area is rural, its population density ranks 36th in the country, and 36% of its inhabitants live in rural communities (vs 21% nationwide).13 Our group has previously shown that the state of Iowa addresses its urology provider access issues by conducting outreach clinics throughout the state,8 most of which also provide procedural care.14 However, how these outreach centers directly affect NMIBC patient outcomes has yet to be determined. While patients likely appreciate the need to travel fewer miles to see their urologists, a trade-off may be that fewer resources are available (eg, BCG) to the providers in these locations and patient care in these smaller centers may differ as a result.

One area in which the state did improve compliance dramatically was in post-TURBT mitomycin instillation. While BCG treatments still represent the gold standard for first line intravesical therapies, multiple variables that can inhibit compliance including; multiple trips to a clinic, they are uncomfortable for patients (and in some cases intolerable), require the confirmation of pathology before initiation, and require special equipment to store and prepare the BCG therapy.15 Evidence has shown that mitomycin C can be safely given after most bladder tumor resections, regardless of grade and stage, and a clinical benefit can be expected,16 thus making it a logical part of routine NMIBC care. However, the significant increase in mitomycin instillation without a corresponding increase in most other guideline suggested post-TURBT NIMBC care suggests that the logistics and access issues related to BCG therapy and other recommended post-TURBT NIMBC may be the primary drivers of low compliance with guidelines rather than lack of urologist awareness of guidelines.

Our study is not devoid of important limitations. First, while the SEER-Medicare database has been extensively utilized to describe practice patterns and healthcare utilization trends in the US, we are still limited by the use of claims data to describe clinical practices, and the possibility of unmeasured confounders. Second, though this study analyzed nearly 17 years-worth of Medicare data for patients residing in the SEER Registry regions, our Iowa NMIBC cohort comprised only 847 patients, which may have limited our ability to determine additional factors associated with compliance. Third, our use of Iowa data only could limit the generalizability of the findings, though we believe they are applicable to most states with similar access issues and rural populations, and the prior evaluation by Chamie et al,7 did not identify any variation by geographic region. Finally, though our analysis of provider distance data offers insights into potential explanations for care discrepancy, patients may not have received care at the closest provider.

CONCLUSION

Compliance with many of the AUA recommendations for NMIBC has not improved in our state over the past 2 decades. Receiving care at an academic cancer center and living closer to a urology provider appears to increase care intensity. As we attempt to improve the care of all NMIBC patients in our rural state, providing evidence-based care to everyone will continue to be logistically challenging as urologist numbers decrease and density within larger metropolitan areas increases. The trend of healthcare consolidation and care centralization within the state may help to improve overall compliance, though likely at the expense of patient convenience. Telemedicine will increase the reach of the individual urologist, but it is yet unclear how this approach will improve delivery of procedural based care. Designing a successful state-run treatment network will require consideration of many patient, provider, disease and educational factors highlighted in this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment.

Dr. Karim Chamie for assistance in grant development and access to prior study methodology.

Disclosures: Funding through the American Urological Association Data (062761671). Grant. This project was also supported by theHCCC Population Research and Biostatis- tics Cores (P30 CA086862).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2019.06.021.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Svatek RS, Hollenbeck BK, Holmang S, et al. The economics of bladder cancer: costs and considerations of caring for this disease. Eur Urol 2014;66:253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riley GF, Potosky AL, Lubitz JD, et al. Medicare payments from diagnosis to death for elderly cancer patients by stage at diagnosis. Med Care 1995;33:828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nepple KG, Lightfoot AJ, Rosevear HM, et al. Bacillus Calmette-Guerin with or without interferon alpha-2b and megadose versus recommended daily allowance vitamins during induction and maintenance intravesical treatment of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. J Urol 2010;184:1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall MC, Chang SS, Dalbagni G, et al. Guideline for the management of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (stages Ta, T1, and Tis): 2007 update. J Urol 2007;178:2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang SS, Boorjian SA, Chou R, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO guideline. J Urol 2016;196:1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chamie K, Saigal CS, Lai J, et al. Quality of care in patients with bladder cancer: a case report? Cancer. 2012;118:1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uhlman MA, Gruca TS, Tracy R, et al. Improving access to urologic care for rural populations through outreach clinics. Urology. 2013;82:1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollenbeck BK, Ye Z, Dunn RL, et al. Provider treatment intensity and outcomes for patients with early-stage bladder cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009;101:571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shelley MD, Court JB, Kynaston H, et al. Intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin versus mitomycin C for Ta and T1 bladder cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003:CD003231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oddens J, Brausi M, Sylvester R, et al. Final results of an EORTCGU cancers group randomized study of maintenance bacillus Calmette-Guerin in intermediate- and high-risk Ta, T1 papillary carcinoma of the urinary bladder: one-third dose versus full dose and 1 year versus 3 years of maintenance. Eur Urol 2013;63:462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke LG, Frakt AB, Khullar D, et al. Association between teaching status and mortality in US hospitals. JAMA. 2017;317:2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.St Sauver JL, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, et al. Associations between longitudinal changes in serum estrogen, testosterone, and bioavailable testosterone and changes in benign urologic outcomes. Am J Epidemiol 2011;173:787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uhlman M, Gruca T, Jarvie C, et al. Taking the Procedure to the patient: increasing access to urological procedural care through outreach. Urology Practice 2017;4:335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hensley D. Hazardous drugs in the urology workplace: focus on intravesical medications. Urol Nurs 2016;36:183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sylvester RJ, Oosterlinck W, Holmang S, et al. Systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of randomized trials comparing a single immediate instillation of chemotherapy after transurethral resection with transurethral resection alone in patients with stage pTa-pT1 urothelial carcinoma of the blad- der: which patients benefit from the instillation? Eur Urol 2016;69:231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.