Abstract

Background: To synthesize high-quality evidence to compare traditional in-person screening and tele-ophthalmology screening.

Methods: Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. The intervention of interest was any type of tele-ophthalmology, including screening of diseases using remote devices. Studies involved patients receiving care from any trained provider via tele-ophthalmology, compared with those receiving equivalent face-to-face care. A search was executed on the following databases: Medline, EMBASE, EBM Reviews, Global Health, EBSCO-CINAHL, SCOPUS, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, OCLC Papers First, and Web of Science Core Collection. Six outcomes of care for age-related macular degeneration (AMD), diabetic retinopathy (DR), or glaucoma were measured and analyzed.

Results: Two hundred thirty-seven records were assessed at the full-text level; six RCTs fulfilled inclusion criteria and were included in this review. Four studies involved participants with diabetes mellitus, and two studies examined choroidal neovascularization in AMD. Only data of detection of disease and participation in the screening program were used for the meta-analysis. Tele-ophthalmology had a 14% higher odds to detect disease than traditional examination; however, the result was not statistically significant (n = 2,012, odds ratio: 1.14, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.52–2.53, p = 0.74). Meta-analysis results show that odds of having DR screening in the tele-ophthalmology group was 13.15 (95% CI: 8.01–21.61; p < 0.001) compared to the traditional screening program.

Conclusions: The current evidence suggests that tele-ophthalmology for DR and age-related macular degeneration is as effective as in-person examination and potentially increases patient participation in screening.

Keywords: : tele-ophthalmology, clinical, systematic review, meta-analysis

Introduction

With an aging population, associated ophthalmic disease frequency will increase demand for eye care, resulting in under supply of eye care providers.1,2 In parallel, there is a shortage of trained ophthalmologists, in both high- and low-income nations.3 Within developed and developing nations, there is a significant regional disparity in the provision of eye services, with most ophthalmologists centered in large cities.4

The rise in chronic eye diseases combined with disproportionate distribution of ophthalmologists has necessitated innovative care delivery methods. Telemedicine is the use of technology to exchange medical data to evaluate patients separated by distance to a physician.5,6 The advent of technological advances and the ability to directly visualize and image the eye have made ophthalmology an ideal specialty for the use of telemedicine. Although there have been a number of review articles describing tele-ophthalmology technologies, there have been few reviews looking at the clinical effectiveness of tele-screening.7–9

Understanding the clinical effectiveness of tele-ophthalmology is vital to ensuring that patients are receiving appropriate care. To our knowledge, there are no systematic reviews that summarize high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on the clinical effectiveness of tele-ophthalmological evaluation of age-related chronic eye disease. The aim of our systematic review was to synthesize high-quality evidence to compare traditional in-person screening and tele-ophthalmology screening. We conducted an up-to-date systematic review of RCTs to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of tele-ophthalmology as an alternative to face-to-face patient screening for three potentially blinding chronic eye diseases: age-related macular degeneration (AMD), diabetic retinopathy (DR), and glaucoma.

Methods and Analysis

Eligibility Criteria for Considering Studies for this Review

Types of studies

Only RCTs (including cluster-randomized trials) were included in this meta-analysis.

Types of participants

Patients receiving care from any trained provider through the medium of tele-ophthalmology, compared with those receiving the equivalent face-to-face care. We excluded children younger than 18 years for this review, given the clinical outcomes we targeted.

Types of interventions

The intervention of interest was any type of tele-ophthalmology, including screening of diseases using remote devices. The comparison interventions could be either single interventions or combination of systems.

Types of outcome measures

Clinical outcomes of care for AMD, DR, or glaucoma. All the relevant clinical outcomes, for which four review authors (A.K., N.S., A.S., and K.F.D.) agreed, were included in our study.

Searching Sources and Strategy

A search was executed by an expert searcher/librarian (S.C.) on the following databases: Medline, EMBASE, EBM Reviews—Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2005 to April 2015), ACP Journal Club (1991 to April 2015), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (2nd Quarter 2015), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (April 2015), Cochrane Methodology Register (3rd Quarter 2012), Health Technology Assessment (2nd Quarter 2015), NHS Economic Evaluation Database (2nd Quarter 2015), Global Health, EBSCO-CINAHL, SCOPUS, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, OCLC Papers First, and Web of Science Core Collection using controlled vocabulary (e.g., MeSH and Emtree) and key words representing the concepts “telehealth” and “ophthalmology.” No limits were applied. Detailed search strategies are available in Supplementary Data (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/tmj).

Data Collection and Analysis

We followed the methodology for data collection and analysis in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.10

Study Selection

Following removal of duplicate studies, two review authors (A.K. and N.S.) independently assessed the eligibility of the studies. We selected studies as being potentially relevant by screening the titles and abstracts. Since categorizing studies was found to be challenging in the initial review (kappa: 0.52, standard error: 0.03), a training session for the two reviewers was performed resulting in good agreement (kappa: 0.81, standard error: 0.02). A third reviewer (A.S.) also assessed all the titles and abstracts that remained in disagreement. We obtained the full text of the article for review when a decision could not be made by screening the title and the abstract. The two review authors (A.K. and N.S.) retrieved the full texts of all potentially relevant articles and independently assessed the eligibility by filling out eligibility forms designed in accordance with the specified inclusion criteria.

Inclusion Criteria

Studies that met the following inclusion criteria were included: (1) compared tele-screening with an in-person gold standard comparator; (2) used tele-ophthalmology as an intervention focusing on screening and detection; (3) had a control group that was screened in person by an individual with background training about the condition being screened, such as ophthalmologists, other physicians, nurses, residents, technicians, or optometrists who had some background education on the disease; (4) reported on clinical effectiveness of DR, glaucoma, and age-related macular degeneration; and (5) reported on patients older than 18 years.

Exclusion Criteria

Studies that met the following criteria were excluded: (1) studies without an in-person screening comparison; (2) studies reporting exclusively on patients younger than 18 years; (3) studies published before 2000 were excluded as we wanted to examine the efficacy of the latest technology and technology before 2000 was thought to be drastically different; (4) studies using tele-ophthalmology for monitoring and management of DR, glaucoma, and age-related macular degeneration; and (5) studies where the comparative group was screened by a computer algorithm or by an individual with no training or background in ophthalmology.

Data Extraction and Management

We extracted the data using a data extraction form that was designed by the review authors. The review authors (A.K. and N.S.) extracted the data independently and entered the data into Review Manager Software® (RevMan 5.1).

Assessment of Risk of bias in included Studies

We used the standard methods of the Cochrane Collaboration to assess the methodological quality of included studies. Specifically, we assessed study quality and risk of bias using the criteria documented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.10 We also assessed eligible studies using the following key criteria: allocation concealment (blinding of randomization), blinding of intervention, completeness of follow-up, and blinding of outcome measurement. We used the “risk of bias” table that addressed the following for each included study: (1) Sequence generation, (2) Allocation concealment, (3) Blinding, (4) Incomplete outcome data: we assessed the completeness of data, including attrition and exclusions from the analysis, (5) Selective reporting bias, and (6) Other sources of bias: we described any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias. Finally, we also assessed whether each study was free of any other issues that could put it at risk of bias. For each element of risk of bias, the risk was categorized as a low, unclear, or high risk.

Measures of Treatment Effect and Data Synthesis

We followed the standard meta-analysis methods of the Cochrane Collaboration. Data were analyzed using random-effect models and were combined with trials where populations, methods, and clinical outcomes were judged to be sufficiently similar. Data were categorical, and treatment effects were reported using odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) estimates. Specifically, we estimated tele-ophthalmology effects for three main outcomes, for which we could obtain the exact number of participants: (1) disease detection, (2) visual acuity at diagnosis of choroidal neovascularization (CNV), and (3) disease screening participation. All statistical analyses for the clinical outcomes were carried out using RevMan 5.1.

Results

Results of the Search

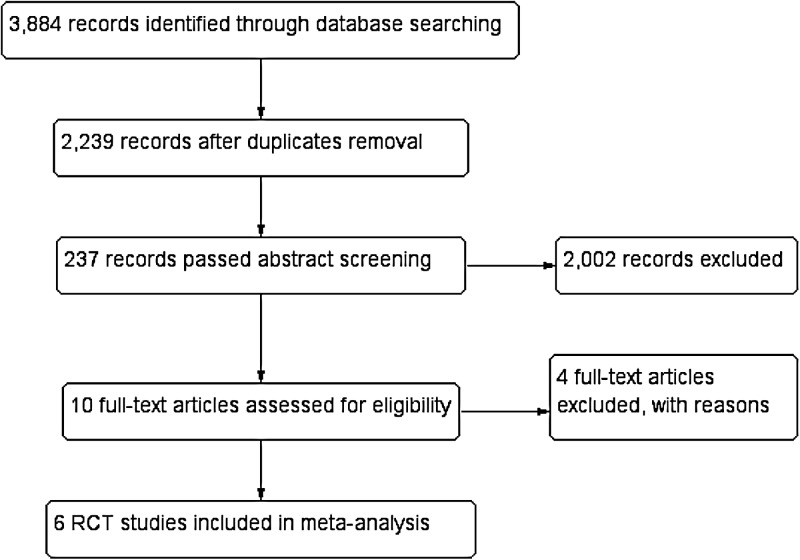

Electronic literature searches as of May 20, 2015, identified 3,884 potentially relevant titles and abstracts for this review (Fig. 1). After duplicate removal, we had 2,239 unique records. Following the independent abstract review, 237 records were assessed at the full-text level, of which 10 were included in the review. We found no ongoing trials. Four out of the 10 were excluded in the meta-analysis with reasons (Supplementary Table: Characteristics of Included and Excluded Studies). The two review authors (A.K., N.S.) agreed on the selection of the six included studies.

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram for the literature search (see also Results section of the search). RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Included Studies

We included six RCTs in this review (Supplementary Table: Characteristics of Included and Excluded Studies).11–16 Four studies involved participants with diabetes mellitus,11,12,14,16 and two studies examined CNV in AMD.13,14 No RCTs were found that examined tele-ophthalmology in glaucoma patients.

Excluded Studies

We excluded four studies from the meta-analysis: one was a protocol of an included study,17 one did not provide results in the published literature,18 and two were not RCTs19,20 (see the Supplementary Table).

Risk of Bias in Included Studies

Allocation

Chew et al. used permuted block size of 4 and Mansberger et al. used a random number generator for randomization (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2).12,14–16 The method of treatment assignment for the other two trials was unclear, although they stated that the groups were randomly allocated.11,13

Blinding

None of the included studies reported masking all study participants and/or personnel. Given the nature of the interventions, we assumed blinding of participants and personnel was not feasible, and thus, we classified the risk of bias for all the included studies as “high.” Blinding of outcome assessment was classified as low/unclear since only Chew et al. reported that the reading center personnel who graded the ocular images were masked to all medical knowledge or treatment assignment of the study participants.15

Incomplete outcome data

The risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data was assessed as low in four studies (13–16) and unclear in two studies.11,12 No exclusions or losses to follow-up were reported in two studies.11,12

Selective Reporting

Four of the included studies demonstrated selective reporting,13–16 and the reporting bias was unable to be determined due to the lack of reported information in two studies.11,12

Other Potential Sources of Bias

We did not identify other potential sources of bias for the included studies, except the study by Davis et al., in which the observational period was not provided and was not clear for the earliest Mansberger et al. report in 2010.11,12

Effects of Interventions

Six different outcomes were evaluated: (1) detection of disease, (2) participation in the screening program, (3) visual acuity at diagnosis, (4) referral accuracy, (5) waiting time to receive a referral, and (6) patient satisfaction. Only data on the first three were used for the meta-analysis.

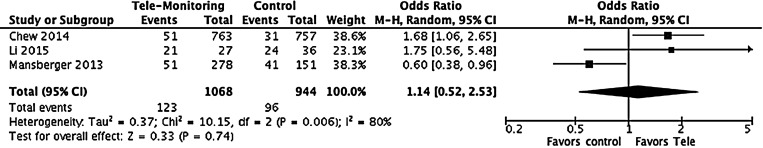

Detection of Disease

Figure 2 shows the results from the three trials that compared detection of the disease.13–15 Results indicate that tele-ophthalmology had a 14% higher odds to detect disease than traditional examination, however, the result was not statistically significant (n = 2,012, OR: 1.14, (95% CI: 0.52–2.53), p = 0.74) (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Detection of the disease. CI, confidence interval; M-H, Mantel–Haenszel; OR, odds ratios.

Table 1.

Summary of Effects in Each Outcome

| OUTCOMES | NO. OF STUDIES INCLUDED | TOTAL NO. OF PARTICIPANTS | EFFECT ESTIMATES ODDS RATIO | 95% CONFIDENCE INTERVALS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detection of CNV | 3 | 2,012 | 1.14 | 0.52–2.53 |

| Participation for eye screening | 2 | 626 | 13.15 | 8.01–21.61 |

| Visual acuity outcomes at diagnosis of CNV | 1 | 81 | 2.42 | 0.90–6.52 |

CNV, choroidal neovascularization.

In the study by Chew et al., at the prespecified interim analysis, 51 individuals were detected to having progressed to CNV in at least one of the study eyes in the device monitoring group and 31 in the standard care group.15 In this study, the accumulation of CNV events over time in each group and the difference in a number of events between the groups were also provided. The device monitoring group accumulated events at a higher rate initially, with the standard care group lagging behind. The events rate became virtually identical in each of the monitoring group later in the study.

Li et al. reported that for the 63 patients enrolled in the monitoring of neovascular AMD recurrence, the recurrence rate was 67.7% in the routine group and 76% in the tele-ophthalmology group. The average time to recurrence for the routine group was 103.9 days compared with the tele-ophthalmology group at 108.1 days. We utilized these numbers in the meta-analysis to estimate the odds for detection of the disease.13

In the study by Mansberger et al., prevalence and severity of DR were provided in proportions. Considering the proportion of patients with DR, excluding patients categorized as “no DR” and “unable to determine,” the proportion of patients detected with DR using tele-ophthalmology was 18.4% (51/278) in the tele-ophthalmology group and 27.1% (41/151) in the traditional group. However, it is important to note that in the tele-ophthalmology group significantly more patients were in the “unable to determine” category for DR compared to the traditional group (9.4% vs. 2.6%). When comparing the “unable to determine” group (n = 67) with those with an adequate DR screening examination (n = 362), older age was the only patient characteristic associated with the “unable to determine” group.14

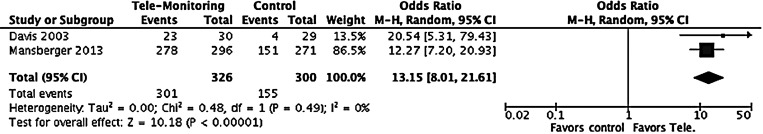

Participation in Eye Screening

Two trials were included considering participation in eye screening as the outcome.11,14 Meta-analysis results show that odds of having DR screening in the tele-ophthalmology group was 13.15 (95% CI: 8.01–21.61; p < 0.001) compared to the traditional screening program (Table 1; Fig. 3). Davis et al. reported that of the 30 patients randomized to the tele-retinal screening, 23 patients (77%) obtained screening eye examinations via tele-ophthalmology. Of the 29 clinical care group of patients, four patients (14%) scheduled eye appointments with eye care providers. Mansberger et al. reported that the tele-ophthalmology group completed a DR screening examination within 12 months of enrollment more frequently than the traditional surveillance group (94% vs. 56%, p < 0.001).14 DR screening was also more frequent in the tele-ophthalmology group compared to the traditional surveillance group in the 6-month through 18-month time bin with a difference of 19.8% (53.0% vs. 33.2% for 6 months, 16.5% vs. 23.1% for 18 months).16

Fig. 3.

Participation for eye screening.

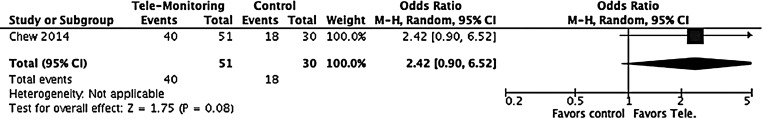

Visual Acuity Outcomes at Diagnosis of CNV

A study by Chew et al. considered visual acuity as an outcome reporting on the best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) test scores at the time of CNV detection.15 In the intention-to-treat (ITT) cohort, the tele-ophthalmology device-monitoring group exhibited a significantly smaller decline in BCVA with fewer letters lost from baseline to CNV detection; a median of −4 letters interquartile range (p = 0.021). The odds of having a better visual acuity in the device monitoring compared to that in the standard group was 2.42 (95% CI: 0.90–6.52; p = 0.08; Table 1; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Visual acuity outcomes at diagnosis of choroidal neovascularization.

Referral Accuracy

Li et al. reported that the referral accuracy in the overall study population for suspected neovascular AMD was 42.3%, and two patients (1.9%) were diagnosed as having neovascular AMD in a nonreferral eye. However, referral accuracy for each study group was not provided.13 In the study by Chew et al., the sensitivity of the home monitoring device and the strategy that included tele-ophthalmology were evaluated by comparing the two study groups.15 Of the 51 eyes in the device monitoring group regardless of whether patients were using the monitoring device at the time when they developed CNV (i.e., ITT), the combination of monitoring device alert and symptoms triggered the first alerts in 37 eyes (72.5%). The monitoring device alone was the first modality to alert in 51.0%; symptoms were the first modality to alert in 21.6%, while the remaining 27.5% had a diagnosis of CNV at the scheduled visit for routine care or the study visit. In the standard care arm that developed CNV, symptoms were the first modality to alert in 54.8%, while 45.2% events were identified during scheduled visits.13

Waiting Time to Receive Referral

Li et al. did not find statistical significant differences in the average referral to diagnostic imaging time between the tele-ophthalmology group (22.5 days) and the routine screening group (18.0 days), a difference of 4.5 days (p = 0.23). The overall referral-to-treatment time for patients who were diagnosed as having neovascular AMD and required treatment was 39.1 days for the tele-ophthalmology group compared with 30.4 days for the routine screening group, a difference of 8.7 days (p = 0.19).13

Patient Satisfaction

A study by Li et al. examined patient satisfaction ratings between routine and tele-ophthalmologic screening for AMD. They found no differences between the two groups regarding ease of access, registration process, staff friendliness, and overall appointment convenience. The tele-ophthalmologic screening group had higher satisfaction ratings, however, when it came to ease of parking indicating that community-based tele-ophthalmologic sites requiring less travel may be more preferable to patients.13

Discussion

Summary of Findings

Based on the six articles included in our study, we have conducted meta-analyses of three outcomes: (1) detection of disease, (2) visual acuity at diagnosis, and (3) participation in the screening program. Our meta-analysis found that tele-ophthalmology had a statistically significantly higher odds of patient participation compared with the clinical in-person care. However, there was no statistically significant difference in the odds of disease detection or visual acuity at the time of disease diagnosis compared with traditional examination (Table 1). Thus, our meta-analysis and systematic review suggest that tele-ophthalmology has similar outcomes to traditional clinical care, while potentially increasing patient participation.

The results for referral accuracy, waiting time to referral, and patient satisfaction could only be synthesized as there were not enough homogenous data to perform a meta-analysis. A study by Chew et al. noted that in the device monitoring group, 73% of patients were identified either via symptoms or through the device with only 27.5% of patients being diagnosed with CNV at a scheduled visit. In comparison, in the standard care arm, 45% of patients were diagnosed at a scheduled visit. This suggests that patients may have been identified earlier by using the tele-screening device. Another study conducted by Li et al. examined the waiting time for referral and patient satisfaction. They found that there was no statistically significant difference between tele-ophthalmology and standard of care for both outcomes. Our systematic review highlights the paucity in RCTs, but the existing studies suggest that tele-ophthalmology is equally effective as in-person consultation and potentially increases patient participation in screening.

Comparison with Literature

To our knowledge, there has been no previously published systematic literature reviews looking at clinical effectiveness using RCTs of tele-ophthalmology. One study by Tan et al. recently published a systematic review of tele-ophthalmology diagnostic accuracy compared with face-to-face consultation. Out of 12 included articles, 1 showed superior accuracy and six articles showed similar accuracy.21 While this review only examined diagnostic accuracy, our meta-analysis of disease detection also showed a positive trend favoring tele-ophthalmology, but showed no statistically significant difference from commonly used in-person care.

Another systematic review conducted by Kanagasingam et al. on AMD found a few studies that described different imaging modalities to screen for AMD. However, they did not report on any study that compared AMD with in-person screening and found a paucity of studies assessing the effectiveness of AMD screening.22 Our review found only two articles reporting on AMD screening and our meta-analysis did not show any significant difference in CNV detection and the patient's visual acuity at the time of diagnosis. Hence, further advances in technology and more routine AMD screening should theoretically lead to earlier disease detection and better management of AMD.

Limitations of this Review

There are a number of limitations to our systematic review. A small number of articles met our inclusion criteria. We only included RCTs in our study to provide high-quality evidence, which limited the number of studies that reported on each of our six outcome measures. There were no studies in tele-glaucoma that met our inclusion criteria. The paucity in tele-ophthalmology literature prevented us from conducting publication bias assessment, and the heterogeneity of the results could not be explored. Our review included a number of different diseases with differing etiologies. As well, the duration of exposure and follow-up for outcome measure was significantly different in each study. These challenges made it difficult to perform meta-analyses on all the outcome measures. The heterogeneity combined with the lack of data allowed us to only perform meta-analyses of the data available for CNV disease detection, visual acuity at time of diagnosis of CNV, and participation in eye screening.

Benefits and Limitations of Tele-Ophthalmology

Tele-ophthalmology has the potential to increase patient access by permitting screening in remote locations.23 It also has the potential to identify patients with disease early and has high patient acceptability and satisfaction due to reduced travel costs and time.24 Our review affirmed that tele-ophthalmology is comparable with traditional in-person screening. Furthermore, it suggests increased patient participation due to the convenience of tele-screening for patients in remote locations.

Tele-ophthalmology is not without limitations. Depending on who is providing frontline screening and management of tele-ophthalmic consultations, telemedicine models could affect the ophthalmologist–patient relationship and create issues surrounding patient ownership and scope of practice. Adequate training of frontline staff will be needed, and clear guidelines and care pathways need to be developed to address these issues and clearly outline the scope of practice for various individuals involved in the initial screening and subsequent interpretation. Currently, tele-screening guidelines exist for DR, but similar guidelines need to be created for other ophthalmic conditions.24 In addition, some diseases, such as glaucoma, will be harder to accurately screen remotely due to technological limitations, for example, related to gonioscopy and anterior segment assessment. However, with innovations and improvements in technology, tele-ophthalmology should become more accurate and feasible. Given the potential heterogeneity of the systems or devices used in telemedicine, we also suggest conducting further literature reviews for each of the diseases to delineate the effects and impacts in each condition.

Conclusions

The current evidence suggests that tele-ophthalmology may be as effective as in-person examination and potentially increases patient participation in screening. Due to the benefits of early disease detection and treatment of these chronic eye diseases, tele-ophthalmology should hold the promise of improved patient screening, early detection, and outcomes. However, our review also highlights the paucity in high-quality RCTs that have looked at the effectiveness of tele-ophthalmology, particularly with respect to glaucoma. In addition, to clinical effectiveness, it will also be important to review the cost–effectiveness of tele-ophthalmology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Atsushi Kawaguchi received support from the Women and Children's Health Research Institute (Graduate Studentship Award) that indirectly supports this study. He also received a graduate stipend from the School of Public Health, University of Alberta, for this specific project. Noha Sharafeldin received a research stipend from the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences.

Authors' Contributions

Dr. Kawaguchi conceptualized and designed the review, carried out the systematic review and subsequent analysis, drafted the initial manuscript (Methods and Analysis and Results sections), revised the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Dr. Sharafeldin conceptualized and designed the review, carried out systematic review and subsequent analysis, drafted the initial manuscript (Methods and Analysis and Results sections), revised the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Ms. Campbell constructed a search formula and conducted a search. She revised the initial manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Dr. Sundaram assisted with the design, carried out the systematic review as a third reviewer, drafted the initial manuscript (Introduction, Methods and Analysis, and Discussion sections), revised the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Dr. Tennant reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final version as submitted. Dr. Rudnisky reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final version as submitted. Dr. Weis helped refine the review and analysis methodology, reviewed and revised the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Dr. Damji conceptualized and designed the review, supervised the construction of the review, reviewed and revised the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Bellan L, Buske L. Ophthalmology human resource projections: Are we heading for a crisis in the next 15 years? Can J Ophthalmol 2007;42:34–38 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Eye Institute. Prevalence of adult vision impairment and age-related eye diseases in America. Available at https://nei.nih.gov/eyedata/adultvision_usa (last accessed December28, 2015)

- 3.Resnikoff S, Felch W, Gauthier TM, Spivey B. The number of ophthalmologists in practice and training worldwide: A growing gap despite more than 200,000 practitioners. Br J Ophthalmol 2012;96:783–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellan L, Buske L, Wang S, Buys YM. The landscape of ophthalmologists in Canada: Present and future. Can J Ophthalmol 2013;48:160–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das T, Raman R, Ramasamy K, Rani PK. Telemedicine in diabetic retinopathy: Current status and future directions. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol 2015;22:174–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li HK. Telemedicine and ophthalmology. Surv Ophthalmol 1999;44:61–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamminen H, Voipio V, Ruohonen K, Uusitalo H. Telemedicine in ophthalmology. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2003;81:105–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murthy KR, Murthy PR, Kapur A, Owens DR. Mobile diabetes eye care: Experience in developing countries. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2012;97:343–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekeland AG, Bowes A, Flottorp S. Effectiveness of telemedicine: A systematic review of reviews. Int J Med Inform 2010;79:736–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions V 5.1.0. Available at http://handbook.cochrane.org/front_page.htm (last accessed March31, 2017)

- 11.Davis RM, Pockl J, Bellis K. Improved diabetic eye care utilizing telemedicine: A randomized controlled trial. IOVSARVO E-abstract 2003:166 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mansberger SL, McClure TM, Wooten KA, Becker TM. Telemedicine to detect diabetic retinopathy in American Indian/Alaska natives and other ethnicities. American Federation for Medical Research Western Regional Meeting, AFMR; 2010, Carmel, CA, 2010;58:116 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li B, Powell A-M, Hooper PL, Sheidow TG. Prospective evaluation of teleophthalmology in screening and recurrence monitoring of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol 2015;133:276–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mansberger SL, Gleitsmann K, Gardiner S, Sheppler C, Demirel S, Wooten K, et al. Comparing the effectiveness of telemedicine and traditional surveillance in providing diabetic retinopathy screening examinations: A randomized controlled trial. Telemed J E Health 2013;19:942–948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Group AHSR, Chew EY, Clemons TE, Bressler SB, Elman MJ, Danis RP, et al. Randomized trial of a home monitoring system for early detection of choroidal neovascularization home monitoring of the Eye (HOME) study. Ophthalmology 2014;121:535–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mansberger SL, Sheppler C, Barker G, Gardiner SK, Demirel S, Wooten K, et al. Long-term comparative effectiveness of telemedicine in providing diabetic retinopathy screening examinations: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol 2015;133:518–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chew EY, Clemons TE, Bressler SB, Elman MJ, Danis RP, Domalpally A, et al. Randomized trial of the ForeseeHome monitoring device for early detection of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. The HOme Monitoring of the Eye (HOME) study design—HOME Study report number 1. Contemp Clin Trials 2014;37:294–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shanit D, Lifshitz T, Giladi R, Peterburg Y. A pilot study of tele-ophthalmology outreach services to primary care. J Telemed Telecare 1998;4 Suppl 1:1–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liesenfeld B, Kohner E, Piehlmeier W, Kluthe S, Aldington S, Porta M, et al. A telemedical approach to the screening of diabetic retinopathy: Digital fundus photography. Diabetes Care 2000;23:345–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maa AY, Evans C, DeLaune WR, Patel PS, Lynch MG. A novel tele-eye protocol for ocular disease detection and access to eye care services. Telemed J E Health 2014;20:318–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan IJ, Dobson LP, Bartnik S, Muir J, Turner AW. Real-time teleophthalmology versus face-to-face consultation: A systematic review. J Telemed Telecare 2017;23:629–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanagasingam Y, Bhuiyan A, Abramoff MD, Smith RT, Goldschmidt L, Wong TY. Progress on retinal image analysis for age related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res 2014;38:20–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sreelatha OK, Ramesh SV. Teleophthalmology: Improving patient outcomes? Clin Ophthalmol 2016;10:285–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cavallerano J, Lawrence MG, Zimmer-Galler I, Bauman W, Bursell S, Gardner WK, et al. Telehealth practice recommendations for diabetic retinopathy. Telemed J E Health 2004;10:469–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.