Abstract

Purpose

To assess the association of baseline tumor size (BTS) with other baseline clinical factors and outcomes in pembrolizumab-treated patients with advanced melanoma in KEYNOTE-001 ().

Experimental Design

BTS was quantified by adding the sum of the longest dimensions of all measurable baseline target lesions. BTS as a dichotomous and continuous variable was evaluated with other baseline factors using logistic regression for objective response rate (ORR) and Cox regression for overall survival (OS). Nominal P values with no multiplicity adjustment describe the strength of observed associations.

Results

Per central review by RECIST v1.1, 583 of 655 patients had baseline measurable disease and were included in this post hoc analysis. Median BTS was 10.2 cm (range, 1–89.5). Larger median BTS was associated with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 1, elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), stage M1c disease, and liver metastases (with or without any other sites) (all P ≤ 0.001). In univariate analyses, BTS below the median was associated with higher ORR (44% vs 23%; P < 0.001) and improved OS (hazard ratio, 0.38; P < 0.001). In multivariate analyses, BTS below the median remained an independent prognostic marker of OS (P < 0.001) but not ORR. In 459 patients with available tumor programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, BTS below the median and PD-L1–positive tumors were independently associated with higher ORR and longer OS.

Conclusion

BTS is associated with many other baseline clinical factors but is also independently prognostic of survival in pembrolizumab-treated patients with advanced melanoma.

Keywords: Immunotherapy, anti–PD-1, prognostic factors

INTRODUCTION

There are multiple clinical factors associated with the overall prognosis for patients with metastatic melanoma including Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS), metastasis (M) stage as defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), and serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (1–4). Medical oncologists often use these prognostic factors to risk-stratify their patients, which may influence treatment decisions.

In addition to the above listed prognostic factors, clinicians commonly take into consideration an assessment of a patient’s tumor burden or baseline tumor size (BTS) when making treatment decisions. For patients with a high burden of disease, a more aggressive treatment approach could be considered and conversely for those with a lower tumor burden a less aggressive approach could be considered. Despite the common use of BTS in clinical decision-making, there is a relative lack of data on both defining tumor burden and evaluating the impact of tumor burden on outcome with therapy.

The purpose of this study was to retrospectively assess the impact of BTS on clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with the anti−programmed death 1 (PD-1) antibody pembrolizumab in the KEYNOTE-001 trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, ). Specifically, we assessed the relationship between BTS and several traditional clinical prognostic factors specific to melanoma (eg, LDH and M-stage) as well as other baseline characteristics such as age, gender, ECOG PS, BRAF status, previous treatments, tumor expression of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), and site of metastases. In addition, we assessed the association of BTS with the clinical outcomes of objective response rate (ORR) and overall survival (OS). We hypothesized that patients with lower BTS would have lower risk clinical factors as well as improved clinical outcomes when compared with patients with larger BTS or non-pulmonary metastases.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Selection and Treatment

As previously described (5–10), patients with advanced melanoma regardless of prior treatment, ECOG PS 0 to 1, ≥1 measurable lesion per investigator assessment, and normal organ function were eligible for the KEYNOTE-001 trial. Only patients with measurable disease at baseline, as assessed by central review and defined by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 (RECIST v1.1) (11) were included in this analysis. Patients received pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks (Q3W), 10 mg/kg Q3W, or 10 mg/kg Q2W. In randomized comparisons, these dosages have shown comparable efficacy (6,8,10,12,13).

The study protocol was approved by the appropriate institutional review boards at each participating institution. The study was conducted in accordance with the protocol, good clinical practice guidelines, the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all local regulations. All patients provided written informed consent.

Assessments

BTS was quantified by adding the sum of the longest dimensions of all measurable baseline target lesions as provided by central radiology review and assessed per RECIST v1.1 modified to include a maximum of 10 target lesions in total if clinically relevant or five per organ. We used 10 lesions instead of 5, as per RECIST v1.1, because at the time of the current study anti-PD1 therapy was in the early stages of development, and the best way to monitor for response was unclear. In the current study, we used all 10 lesions (in patients who had 10 lesions) per the design of the study. Best overall response by blinded independent central review per RECIST v1.1 was categorized as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or progressive disease. Analyses were performed using the best response by week 28. ORR was defined as the percentage of patients who achieved CR or PR; disease control rate (DCR) was defined as the percentage of patients who achieved CR, PR, or SD; and OS was defined as time from enrollment to death from any cause.

Tumor PD-L1 expression was assessed by a prototype immunohistochemistry assay (QualTek Molecular Laboratories, Goleta, CA) (14) in pretreatment tumor biopsy samples using the 22C3 antibody (Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ). PD-L1 positivity was defined as membranous staining in ≥1% of tumor and/or immune cells in tumor nests.

Statistical Methods

BTS was compared in subgroups defined by traditional baseline clinical factors (ECOG PS [0 vs 1], LDH level [normal vs elevated], M stage [M0, M1a, or M1b vs M1c], age [below vs above the median], and sex [male vs female]), as well as with other baseline clinical factors (BRAFV600 mutation status [mutant vs wild-type], prior brain metastases [yes vs no], prior ipilimumab treatment [naive vs exposed], number of prior therapies [0 vs ≥1], pembrolizumab dose and schedule [10 mg/kg Q2W vs 10 mg/kg Q3W vs 2 mg/kg Q3W], tumor PD-L1 status [positive vs negative], and site of metastasis [lung only vs liver (with or without any other sites) vs other]) using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test. Baseline factors were analyzed for their association with ORR using logistic regression. Univariate factors with P < 0.10 were then analyzed using a multivariate logistic regression to test independence in a stepwise procedure with alpha-to-enter 0.025 and alpha-to-remove 0.05. The association of baseline clinical factors with OS was estimated with a univariate Cox proportional hazard analysis applying the Efron method for handling ties. Statistical analyses were done using SAS (version 9.3).The data cutoff date for this post hoc analysis was September 18, 2015.

RESULTS

Patients and Association of BTS with Baseline Clinical Characteristics

Of the 655 patients with advanced melanoma treated in the KEYNOTE-001 trial, 583 had measurable disease at baseline by central RECIST v1.1 and were included in the analysis. Baseline characteristics for these patients are outlined in Table 1. Median age was 61 years, and the majority had ECOG PS 0 (66%), normal LDH level (58%), and stage M1c disease (80%). Of the 23% of patients with BRAFV600-mutant tumors, 68% had previously received a BRAF inhibitor. Most patients (77%) had previously received ≥1 therapy; 52% had previously received ipilimumab.

Table 1.

Baseline patient and disease characteristics by baseline tumor size

| Factor | N (%†) | BTS below median, n/N (%) | BTS above median, n/N (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 583 (100) | 292/583 (50) | 291/583 (50) | |

| Traditional factors | ||||

| ECOG PS | ||||

| 0 | 387 (66) | 224/387 (58) | 163/387 (42) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 195 (34) | 68/195 (35) | 127/195 (65) | |

| LDH level | ||||

| Normal | 333 (58) | 226/333 (68) | 107/333 (32) | <0.001 |

| Elevated | 238 (42) | 63/238 (27) | 175/238 (74) | |

| M stage | ||||

| M0, M1a, or M1b | 119 (20) | 96/119 (81) | 23/119 (19) | <0.001 |

| M1c | 464 (80) | 196/464 (42) | 268/464 (58) | |

| Age | ||||

| Below median (≤ 61 years) | 298 (51) | 134/298 (45) | 164/298 (55) | 0.012 |

| Above median (>61 years) | 285 (49) | 158/285 (55) | 127/285 (45) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 365 (63) | 179/365 (49) | 186/365 (51) | 0.514 |

| Female | 218 (37) | 113/218 (52) | 105/218 (48) | |

| Other factors | ||||

| BRAFV600 mutation status | ||||

| Mutant | 133 (23) | 66/133 (50) | 67/133 (50) | 0.976 |

| Wild type | 444 (77) | 221/444 (50) | 223/444 (50) | |

| Prior brain metastases | ||||

| Yes | 50 (9) | 31/50 (62) | 19/50 (38) | 0.076 |

| No | 532 (91) | 260/532 (49) | 272/532 (51) | |

| Prior ipilimumab treatment | ||||

| Naive | 278 (48) | 155/278 (56) | 123/278 (44) | 0.009 |

| Exposed | 305 (52) | 137/305 (45) | 168/305 (55) | |

| Number of prior therapies | ||||

| 0 | 137 (23) | 77/137 (56) | 60/137 (44) | 0.102 |

| ≥ 1 | 446 (77) | 215/446 (48) | 231/446 (52) | |

| Pembrolizumab dose and schedule | ||||

| 10 mg/kg Q2W | 168 (29) | 92/168 (55) | 76/168 (45) | 0.329 |

| 10 mg/kg Q3W | 272 (47) | 133/272 (49) | 139/272 (51) | |

| 2 mg/kg Q3W | 143 (25) | 67/143 (47) | 76/143 (53) | |

| Tumor PD-L1 status | ||||

| Positive | 353 (77) | 175/353 (50) | 178/353 (50) | 0.925 |

| Negative | 106 (23) | 52/106 (49) | 54/106 (51) | |

| Site of metastasis | ||||

| Lung only | 84 (14) | 74/84 (88) | 10/84 (12) | <0.001 |

| Liver, with or without any other sites | 201 (34) | 62/201 (31) | 139/201 (69) | |

| Other | 298 (51) | 156/298 (52) | 142/298 (48) | |

Abbreviations: BTS, baseline tumor size; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; Q2W, every 2 weeks; Q3W, every 3 weeks.

Percentages calculated by using the number of patients with available data for each baseline characteristic as the denominator (may be <583 patients for some characteristics).

Median BTS was 10.2 cm (range, 1–89.5 cm) (Supplemental Fig. S1). Several baseline clinical factors were associated with BTS. Larger median BTS was observed in patients with ECOG PS 1 compared with ECOG PS 0 (15.3 cm vs 8.1 cm; P < 0.001), elevated LDH level compared with normal LDH level (17.3 cm vs 6.2 cm; P < 0.001), stage M1c disease compared with other disease stages (13.1 cm vs 4.3 cm; P < 0.001), and age below the median compared with age above the median (12.0 cm vs 8.8 cm; P = 0.038). The location of metastases was also strongly associated with BTS. Patients with liver metastases (with or without any other sites) had larger median BTS versus those with lung only or other metastases (15.3 cm vs 3.9 cm vs 9.3 cm; P < 0.001). Compared with patients who were treatment naive, patients with previously treated disease had larger median BTS (11.1 cm vs 9.3 cm; P = 0.013), including those who previously received ipilimumab compared with those who were ipilimumab naive (12.1 cm vs 8.8 cm; P = 0.002).

Univariate Analysis of Baseline Clinical Factors Associated with ORR

In the 583 patients with measurable disease at baseline, the CR rate was 10%, ORR was 33%, and DCR was 51% (Table 2). Several baseline clinical factors were associated with higher ORR, including normal LDH level compared with elevated LDH level (P < 0.001), stage M0, M1a, or M1b disease compared with M1c disease (P < 0.001), BRAFV600 wild-type status compared with BRAFV600 mutant status (P = 0.036), no prior ipilimumab treatment compared with prior ipilimumab treatment (P = 0.028), no prior therapy compared with prior therapy (P = 0.009), BTS below the median compared with BTS above the median (P < 0.001), PD-L1–positive tumors compared with PD-L1‒negative tumors (P < 0.001), and lung only metastases compared with liver (with or without any other sites) and other metastases (P < 0.001) (Table 3). Patients with a BTS below the median were more likely to achieve CR (18% vs 2%; P < 0.001) and had a higher ORR (44% vs 23%; P < 0.001) and DCR (62% vs 40%; P < 0.001) than patients with a BTS above the median (Table 2). Patients with lung only metastases experienced an ORR of 62% while patients with liver metastases (with or without any other sites) had an ORR of 22%.

Table 2.

Summary of best overall response by independent review per RECIST v1.1

| Total population, % | BTS below median, % | BTS above median, % | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | 10 | 18 | 2 | <0.001 |

| PR | 24 | 26 | 21 | 0.149 |

| SD | 18 | 19 | 17 | 0.600 |

| PD | 39 | 33 | 45 | 0.005 |

| ORR | 33 | 44 | 23 | <0.001 |

| DCR | 51 | 62 | 40 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: BTS, baseline tumor size; CR, complete response; DCR, disease control rate; ORR, objective response rate; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors; SD, stable disease.

Table 3.

Univariate association of baseline patient and disease characteristics with survival and response

| Factor | Overall survival | Response | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive at 1 year, % (95% CI) | HR | P | ORR, % | P | |

| Traditional factors | |||||

| ECOG PS | |||||

| 0 | 70 (65.6 to 74.7) | 0.56 | <0.001 | 36 | 0.100 |

| 1 | 51 (43.6 to 57.7) | 29 | |||

| LDH level | |||||

| Normal | 79 (74.0 to 82.8) | 0.37 | <0.001 | 43 | <0.001 |

| Elevated | 44 (37.2 to 49.8) | 21 | |||

| M stage | |||||

| M0, M1a, or M1b | 86 (78.6 to 91.4) | 0.40 | <0.001 | 50 | <0.001 |

| M1c | 58 (53.6 to 62.6) | 29 | |||

| Age | |||||

| Below median (≤61 years) | 63 (56.7 to 67.8) | 0.93 | 0.534 | 32 | 0.464 |

| Above median (>61 years) | 65 (59.6 to 70.6) | 35 | |||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 64 (58.5 to 68.4) | 0.91 | 0.400 | 36 | 0.180 |

| Female | 64 (57.6 to 70.4) | 30 | |||

| Other factors | |||||

| BRAFV600 mutation status | |||||

| Wild type | 66 (60.8 to 69.7) | 0.82 | 0.113 | 36 | 0.036 |

| Mutant | 59 (50.4 to 67.2) | 26 | |||

| Prior brain metastases | |||||

| Yes | 68 (53.2 to 79.0) | 0.84 | 0.391 | 34 | 1.000 |

| No | 64 (59.2 to 67.4) | 34 | |||

| Prior ipilimumab treatment | |||||

| Naive | 68 (62.4 to 73.5) | 0.88 | 0.234 | 38 | 0.028 |

| Exposed | 60 (54.2 to 65.2) | 29 | |||

| Number of prior therapies | |||||

| 0 | 70 (61.8 to 77.3) | 0.77 | 0.053 | 43 | 0.009 |

| ≥ 1 | 62 (57.3 to 66.3) | 31 | |||

| Pembrolizumab dose and schedule | |||||

| 10 mg/kg Q2W | 63 (55.5 to 70.1) | 0.97 | 0.704 | 37 | 0.522 |

| 10 mg/kg Q3W | 64 (57.6 to 69.1) | 1.02 | 32 | ||

| 2 mg/kg Q3W | 65 (56.8 to 72.5) | 32 | |||

| BTS (SLD) | |||||

| Below median (≤ 10.2 cm) | 80 (74.6 to 83.9) | 0.38 | <0.001 | 44 | <0.001 |

| Above median (> 10.2 cm) | 48 (42.0 to 53.6) | 23 | |||

| Tumor PD-L1 status | |||||

| Positive | 69 (63.6 to 73.4) | 0.51 | <0.001 | 39 | <0.001 |

| Negative | 45 (35.4 to 54.4) | 13 | |||

| Site of metastasis | |||||

| Lung only | 89 (80.4,94.3) | 0.29 | <0.001 | 62 | <0.001 |

| Liver, with or without any other sites | 53 (46.2,60.1) | 1.00 | 22 | ||

| Other | 64 (58,68.9) | 0.65 | 33 | ||

Abbreviations: BTS, baseline tumor size; CI, confidence interval; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HR, hazard ratio; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ORR, objective response rate; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; Q2W, every 2 weeks; Q3W, every 3 weeks; SLD, sum of the longest diameters.

Univariate Analysis of Baseline Clinical Factors Associated with OS

With a median follow-up of 32 months (range, 24–46 months), median OS was 24 months at the time of analysis. Of the 655 patients treated in the trial, 66% were alive at 1 year, 50% were alive at 2 years, and 40% were alive at 3 years.

Several baseline clinical factors were associated with improved OS, including ECOG PS 0 compared with 1 (hazard ratio [HR], 0.56; P < 0.001), normal LDH level compared with elevated LDH level (HR, 0.37; P < 0.001), stage M0, M1a, or M1b disease compared with M1c disease (HR, 0.40; P < 0.001), no prior therapy compared with prior therapy (HR, 0.77; P = 0.053), BTS below the median compared with BTS above the median (HR, 0.38; P < 0.001), PD-L1‒positive tumors compared with PD-L1‒negative tumors (HR, 0.51; P < 0.001), and lung only and other metastases compared with liver metastases (with our without any other sites) (HRs, 0.29, 0.65, and 1.00; P < 0.001) (Table 3).Patients with lung only metastases had a 1-year OS rate of 89% while patients with liver metastases (with or without any other sites) had a 1-year OS rate of 53%

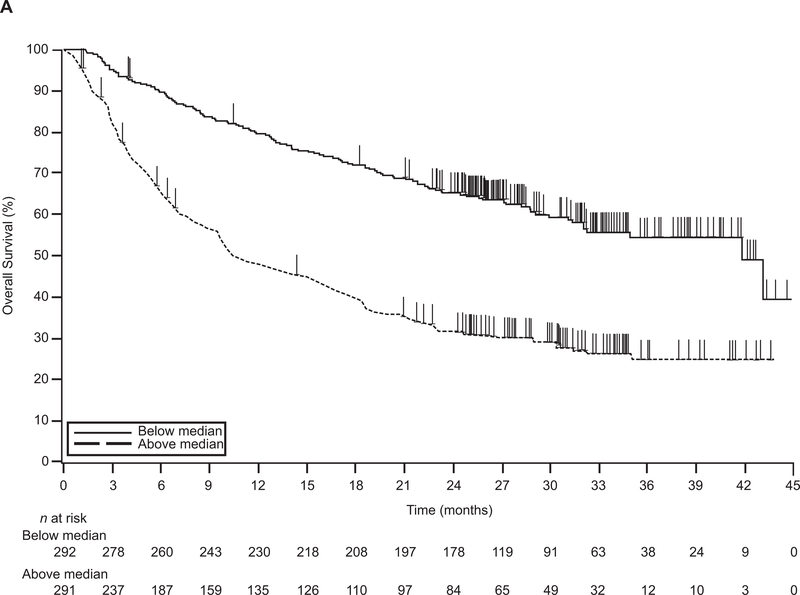

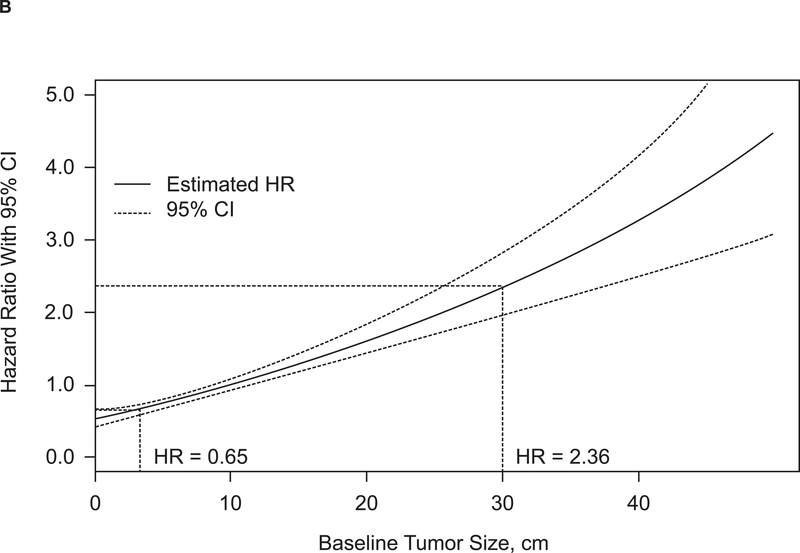

At 1 year, 80% of patients with BTS below the median were alive, compared with 48% of patients with BTS above the median (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1A). A continuous and direct relationship between BTS and risk for death was observed when BTS was assessed as a continuous variable (Fig. 1B). Using the median BTS of 10.2 cm as a comparator (HR, 1), a patient with BTS 30 cm had an HR for death of 2.36. Conversely, a patient with BTS 3.3 cm had an HR for death of 0.65.

Figure 1. Relationship between baseline tumor size and survival.

(A) Kaplan-Meier estimate of OS. (B) Baseline tumor size as a continuous effect on OS. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival.

Multivariate Analysis of Baseline Clinical Factors Associated with ORR and OS

Among the eight factors associated with ORR in the univariate model, three remained independently associated with higher ORR in a multivariate model: normal LDH level (odds ratio [OR], 2.52; P < 0.001), no prior therapies (OR, 1.76; P = 0.010), and site of metastasis (ORs, 4.51 and 1.81; P < 0.001) (Table 4). Of the 324 total deaths that occurred among treated patients with measurable disease at baseline, 315 occurred among the population included in the multivariate analysis. Among the seven factors associated with OS in the univariate model, four remained independently associated with longer OS in a multivariate model: normal LDH level (HR, 0.48; P < 0.001), BTS below the median (HR, 0.61; P < 0.001), ECOG PS of 0 (HR, 0.71; P = 0.004), and site of metastasis (HRs, 0.49 and 0.71; P = 0.002) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Independent factors on ORR

| Factors | OR | P |

|---|---|---|

| Normal LDH level | 2.52 | <0.001 |

| No prior therapies | 1.76 | 0.010 |

| Site of metastasis | <0.001 | |

| Lung only vs liver, with or without any other sites | 4.51 | |

| Other vs liver, with or without any other sites | 1.81 |

Abbreviations: LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; OR, odds ratio; ORR, objective response rate.

Table 5.

Independent factors on OS

| Factors | HR | P |

|---|---|---|

| Normal LDH level | 0.48 | <0.001 |

| BTS below median | 0.61 | <0.001 |

| ECOG PS 0 | 0.71 | 0.004 |

| Site of metastasis | 0.002 | |

| Lung only vs liver, with or without any other sites | 0.49 | |

| Other vs liver, with or without any other sites | 0.71 |

Abbreviations: BTS, baseline tumor size; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HR, hazard ratio; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; OS, overall survival.

Analysis of PD-L1 Expression as a Biomarker of ORR and OS

Of the 583 patients included in the analysis, 459 (79%) had tumor samples evaluable for PD-L1 expression, of which 353 (77%) had PD-L1–positive tumors and 106 (23%) had PD-L1–negative tumors (Table 1). Tumor PD-L1 expression was not associated with any baseline clinical factors except for prior ipilimumab treatment and site of metastasis because patients previously treated with ipilimumab were more likely to have PD-L1‒positive tumors than those who were ipilimumab naive (81% vs 72%; P = 0.015) and patients with lung only metastases were more likely to have PD-L1‒positive tumors than those with liver (with or without any other sites) or other sites of metastases (85% vs 68% vs 80%; P = 0.008). The percentage of patients with PD-L1–positive tumors did not differ among those with BTS above or below the median.

Patients with PD-L1–positive tumors were more likely to achieve an objective response than patients with PD-L1–negative tumors (39% vs 13%; P < 0.001). After adjusting for other factors that were at least minimally associated with higher ORR (P < 0.10), normal LDH level (OR, 1.93; P = 0.008), no prior therapies (OR, 2.04; P = 0.007), BTS below the median (OR, 1.63; P = 0.0496), PD-L1–positive tumors (OR, 4.19; P < 0.001), and lung only or other metastasis (OR, 3.54 and 1.78; P = 0.003) remained independently associated with higher ORR.

In the 459 patients with tumor samples evaluable for PD-L1 expression, those with PD-L1–positive tumors were also more likely to be alive at 1 year than those with PD-L1–negative tumors (69% vs 45%; P < 0.001) (Supplemental Table S1). When these factors were combined in a multivariate model, six factors remained independently associated with longer OS: ECOG PS 0, normal LDH level, no prior therapies, BTS below the median, PD-L1–positive tumors, and lung metastases.

We also performed a subset analysis of the 139 treatment-naive patients with measurable BTS (supplemental Table S2 and supplemental Figure S2). The median BTS in this subset was 10.2 cm; patients with BTS less than or equal to the median BTS were more likely to be alive at 1 year compared to those patients with a greater than median BTS (83% versus 56%, P < 0.001) and median survival was also significantly longer in patients with less than the median BTS (supplemental Figure S2). In terms of ORR, there was not a significant difference between patients above or below median BTS (50% versus 38%, P = 0.163).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the prognostic effect of BTS on clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with anti–PD-1 therapy. Not surprisingly, BTS was strongly associated with many baseline clinical factors and thus was also strongly associated with clinical outcomes. In our multivariate model, BTS was not independently associated with ORR but did remain independently associated with OS.

As BTS has not been routinely assessed and reported, it is difficult to contextualize the results of this work with previous studies that evaluated the effectiveness of immunotherapy in patients with metastatic melanoma. In previous studies of patients treated with high-dose interleukin 2, higher ORR was associated with ECOG PS 0 (15), no prior systemic therapy (15) and decreased LDH level (16). In the current study of PD-1 blockade with pembrolizumab, higher ORR was associated with normal LDH level; stage M0, M1a, or M1b disease; BRAFV600 wild-type status; no prior ipilimumab treatment; no prior therapy; BTS below the median; PD-L1–positive tumors; and number of sites of metastases in a univariate analysis. In a multivariate analysis, only normal LDH level, no prior therapies, and number of sites of metastasis were independently associated with higher ORR. In the prospective phase III study that compared ipilimumab with glycoprotein 100, no pretreatment characteristics identified patients more likely to benefit from ipilimumab; however, BTS was not evaluated in that report (17). Others have used number of organ sites involved of greater than or less than 3 as an important marker of prognosis in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with dabrafenib and trametinib (18). As a part of future studies, we plan to incorporate number of involved organ sites as a potential surrogate for BTS.

Although this analysis cannot differentiate the predictive versus prognostic effect of baseline factors, we hypothesize that BTS represents a distinct balance between tumor antigen burden and the preexisting ineffective immune response that, when adequately augmented by PD-1 blockade, can result in an effective antitumor response. Huang et al recently demonstrated that the magnitude of the pretreatment immune response is indeed related to tumor burden, suggesting an ineffective preexisting response; with PD-1 blockade, the increase in immune response relative to baseline tumor burden may be predictive of antitumor response (19). By this mechanism, BTS may be, in part, predictive of response to PD-1 blockade and prognostic of outcome as a result of both lead-time bias and a more efficient preexisting immune response.

Although patients with PD-L1–positive tumors had a higher ORR and better prognosis than patients with PD-L1–negative tumors, no association between BTS and PD-L1 expression was identified. That is, patients with a large BTS were as likely to have a PD-L1–positive tumor as patients with a small BTS. At present, PD-L1 expression remains a dynamic marker with unclear clinical usefulness in melanoma.

There are several potential clinical implications of this work. Our data suggest that there is a greater unmet medical need in patients with a larger BTS, a group that typically included previously treated patients, which thereby supports use of PD-1 inhibitors earlier in the disease course. In support of earlier PD-1 blockade, the ORR for pembrolizumab in KEYNOTE-001 was 33% overall but was 45% in treatment-naive patients (20). Other published data also suggest that ORR might be higher in previously untreated patients (13,21). In addition, although patients with a larger BTS had decreased survival compared with those with a smaller BTS, the 1-year survival rate of 48% for patients with BTS above the median is clinically meaningful and indicates that patients still benefit from pembrolizumab despite having a large tumor burden. Finally, if BTS were validated in subsequent studies as a predictive factor, it might be additionally insightful to assess BTS, among other baseline factors, in randomized studies of dual checkpoint blockade versus single-agent PD-1 blockade as a step toward improving patient selection for combination therapy options that may have increased toxicity.

Our findings may also have implications for trial design in melanoma. Because of the strength of BTS as an independent prognostic factor, BTS could be considered a stratification factor for clinical trials of PD-1 blockade if validated in additional studies. However, the application of using BTS to stratify patients could be challenging because of the continuous relationship between BTS and risk for death; therefore, a validated cut-off point of BTS would be helpful in this respect. In addition, although cross-trial comparisons are challenging and never definitive, the prospective quantification of BTS could allow for assessment of similar patient populations when comparing trial designs.

In addition to BTS, well-known prognostic markers in melanoma, such as LDH level, ECOG PS, and M stage, were also strongly associated with clinical outcome in this study, supporting the applicability of these results to the general melanoma population. One of the more interesting findings of our analysis was the exceptionally good outcomes for patients with lung only metastases; these patients experienced a near tripling of ORR compared with patients with liver metastases (62% vs 22%). While independent validation of this finding is necessary, if confirmed this information could aid in clinical decision making.

There are several important limitations of this work. First, our findings require prospective validation in an independent cohort. The effect of BTS on clinical outcomes in the KEYNOTE-002 () (12) and KEYNOTE-006 () (13) studies may help further address this question. Importantly, KEYNOTE-006 is a first-line study; therefore, it will be important to assess the value of BTS without the confounding element of prior treatment effect and to consider subsequent therapies in any analysis. Second, because the data derive from an uncontrolled study, conclusions cannot be drawn about whether BTS is prognostic or predictive in nature. Because BTS is associated with other known prognostic factors (such as elevated LDH and site of metastases), it is possible that it is a prognostic factor that might be associated with lower response across a variety of therapeutic categories. Another limitation is that there is no recognized gold standard to assess BTS. In this study, we evaluated the sum of the longest diameters of ≤10 target lesions and five lesions per organ, but we did not include lesions that are not captured by RECIST v1.1, such as bone lesions or lesions that did not meet RECIST v1.1 size criteria. We chose 10 lesions instead of 5, as per RECIST v1.1, because, at the time the study was designed, how to assess response to anti-PD1 agents was unclear. The design of the study included up to 10 lesions instead of the traditional 5 in RECIST v1.1 and, for the purposes of this manuscript, we included all 10 lesions as captured in the database. Therefore, our assessment of BTS does not include all lesions present in the patient and does include up to 5 more lesions than would be counted in RECIST v1.1. Another limitation of the current study is that we did not explore the difference between having multiple small tumors and having one large tumor. We believe this work is important and should be a part of future of analyses in melanoma and other tumor types, along with analysis of the number of involved metastatic sites.

In summary, BTS is strongly associated with several baseline clinical factors and clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with pembrolizumab. Because of the association of BTS with other known prognostic factors in melanoma, BTS should also be studied for its association with clinical outcomes of other antitumor agents. Because melanoma treatment strategies rapidly evolve, a key next step in advancing the field is to better define which therapy is best for the individual patient to minimize unnecessary toxicity without compromising clinical effectiveness. BTS may play a significant role in realizing individualized patient therapy.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the patients and their families and caregivers, and all investigators and site personnel, for participating in the study; Roger Dansey, MD (Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ), for critical manuscript review; and QualTek Molecular Laboratories (Goleta, CA) for PD-L1 immunohistochemistry assay testing. Medical writing and editorial assistance, funded by Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, were provided by Tricia Brown, MS, and Payal Gandhi, PhD, of the ApotheCom pembrolizumab team (Yardley, PA). This study was funded by Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ.

DISCLOSURE OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

R.W. Joseph has a consulting or advisory role for Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, and Exelixis; and received research funding to his institution from Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ. J. Elassaiss-Schaap was an employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, during the conduct of the study; he is currently director/owner of the privately held company PD-value B.V. that is active in the field of data-analytical services to the pharmaceutical industry. R. Kefford has a consulting or advisory role for Novartis, Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, Teva, and Bristol-Myers Squibb; has participated in speaker’s bureau for Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ and Bristol-Myers Squibb; and has received travel, accommodations, or expenses from Bristol-Myers Squibb. W.-J. Hwu has a consulting or advisory role for Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, and has received research funding from Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, and MedImmune. J.D. Wolchok has a consulting or advisory role for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, MedImmune, and Genentech and has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, and Genentech. A. Ribas has stock or other ownership interest in Kite Pharma, and has had a consulting or advisory role for Amgen, Pfizer, Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, and Roche. F.S. Hodi has had a consulting or advisory role for Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, EMD Serono, and Amgen; has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb; and has patents for MICA-related disorders and tumor antigens. O. Hamid has received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Novartis, and Amgen; has had a consulting or advisory role for Amgen, Novartis, Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ; has participated in speaker’s bureau for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, Novartis, and Amgen; and has received research funding from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celldex, Genentech, Immunocore, Incyte, Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, Merck Serono, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Rhinat, and Roche. C. Robert has had a consulting or advisory role for Amgen, Novartis, Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and GlaxoSmithKline. A. Daud has stock or other ownership interest in OncoSec, Inc.; has had a consulting or advisory role for Novartis, Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, Pfizer, and Genentech; has received research funding from Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, Pfizer, Genentech, and Bristol-Myers Squibb; and has a patent with OncoSec, Inc. J.S. Weber has stock or other ownership interest in Cytomx and Alton; has received honoraria from Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Celldex, Cytomx, Sellas, and EMD Serono; has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb; and has a patent by Biodesix for PD-1 biomarker. A. Patnaik has received research funding from Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ to her institution. D.P. de Alwis, A. Perrone, J. Zhang, and K.M Anderson are employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, and hold stock in the company. S.P Kang is an employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, and holds stock in the company, and has a patent from Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, for pembrolizumab in cancer. S. Ebbinghaus is an employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, and holds stock and a leadership position in the company. T.C Gangadhar has received honoraria from Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Novartis, and has received research funding from Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Incyte. A.M. Joshua, R. Dronca, P. Hersey declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

ASCO Annual Meeting 2014: Joseph RW et al. Abstract 2015: Baseline tumor size as an independent prognostic factor for overall survival in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with the anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody MK-3475.

Society for Melanoma Research 2014 Congress: Joseph R et al. Baseline tumor size (BTS) and PD-L1 expression are independently associated with clinical outcomes in patients (pts) with metastatic melanoma (MM) treated with pembrolizumab (pembro; MK-3475).

References

- 1.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol 1982;5:649–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balch CM, Buzaid AC, Soong S-J, Atkins MB, Cascinelli N, Coit DG, et al. Final version of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:3635–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwala SS, Keilholz U, Gilles E, Bedikian AY, Wu J, Kay R, et al. LDH correlation with survival in advanced melanoma from two large, randomised trials (Oblimersen GM301 and EORTC 18951). Eur J Cancer 2009;45:1807–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedikian AY, Johnson MM, Warneke CL, Papadopoulos NE, Kim K, Hwu WJ, et al. Prognostic factors that determine the long-term survival of patients with unresectable metastatic melanoma. Cancer Invest 2008;26:624–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, Hodi FS, Hwu WJ, Kefford R, et al. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2013;369:134–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robert C, Ribas A, Wolchok JD, Hodi FS, Hamid O, Kefford R, et al. Anti-programmed-death-receptor-1 treatment with pembrolizumab in ipilimumab-refractory advanced melanoma: a randomised dose-comparison cohort of a phase 1 trial. Lancet 2014;384:1109–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patnaik A, Kang SP, Rasco D, Papadopoulos KP, Elassaiss-Schaap J, Beeram M, et al. Phase I study of pembrolizumab (MK-3475; anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody) in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:4286–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamid O, Robert C, Ribas A, Wolchok F, Hodi S, Kefford R, et al. Randomized comparison of two doses of the anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody MK-3475 for ipilimumab-refractory (IPI-R) and IPI-naive (IPI-N) melanoma (MEL). J Clin Oncol 2014;32(suppl): abstr 3000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ribas A, Hamid O, Daud A, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD, Kefford R, et al. Association of Pembrolizumab With Tumor Response and Survival Among Patients With Advanced Melanoma. JAMA 2016;315:1600–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robert C, Joshua AM, Weber JS, Ribas A, Hodi FS, Kefford RF, et al. Pembrolizumab (pembro; MK-3475) for advanced melanoma (MEL): randomized comparison of two dosing schedules. Ann Oncol 2014;25:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishino M, Jagannathan JP, Ramaiya NH, Van den Abbeele AD. Revised RECIST guideline version 1.1: what oncologists want to know and what radiologists need to know. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010;195:281–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ribas A, Puzanov I, Drummer R, Daud A, Schadendorf D, Robert C, et al. A randomized controlled comparison of pembrolizumab and chemotherapy in patients with lpilimumab-refractory melanoma. Presented at The Society for Melanoma Research Eleventh International Congress; November 13–17, 2014; Zurich, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, Arance A, Grob JJ, Mortier L, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2521–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolled-Filhart M, Locke D, Murphy T, Lynch F, Yearley JH, Frisman D, et al. Development of a prototype immunohistochemistry assay to measure programmed death ligand-1 expression in tumor tissue. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2016;140:1259–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atkins MB, Lotze MT, Dutcher JP, Fisher RI, Weiss G, Margolin K, et al. High-dose recombinant interleukin 2 therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: analysis of 270 patients treated between 1985 and 1993. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:2105–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joseph RW, Sullivan RJ, Harrell R, Stemke-Hale K, Panka D, Manoukian G, et al. Correlation of NRAS mutations with clinical response to high-dose IL-2 in patients with advanced melanoma. J Immunother 2012;35:66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010;363:711–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schadendorf D, Long GV, Stroiakovski D, Karaszewska B, Hauschild A, Levchenko E, et al. Three-year pooled analysis of factors associated with clinical outcomes across dabrafenib and trametinib combination therapy phase 3 randomised trials. Eur J Cancer 2017;82:45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang AC, Postow MA, Orlowski RJ, Mick R, Bengsch B, Manne S, et al. T-cell invigoration to tumour burden ratio associated with anti-PD-1 response. Nature 2017;545:60–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daud A, Ribas A, Robert C, Hodi S, Wolchock JD, Joshua AM, et al. Long-term efficacy of pembrolizumab (pembro; MK-3475) in a pooled analysis of 655 patients (pts) with advanced melanoma (MEL) enrolled in KEYNOTE-001. J Clin Oncol 2015;33(suppl): abstr 9005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, Dutriaux C, Maio M, Mortier L, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med 2015;372:320–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.