Abstract

Cytarabine (AraC) is the mainstay for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Although complete remission is observed in a large proportion of patients, relapse occurs in almost all the cases. The chemotherapeutic action of AraC derives from its ability to inhibit DNA synthesis by the replicative polymerases (Pols); the replicative Pols can insert AraCTP at the 3′ terminus of the nascent DNA strand, but they are blocked at extending synthesis from AraC. By extending synthesis from the 3′-terminal AraC and by replicating through AraC that becomes incorporated into DNA, translesion synthesis (TLS) DNA Pols could reduce the effectiveness of AraC in chemotherapy. Here we identify the TLS Pols required for replicating through the AraC templating residue and determine their error-proneness. We provide evidence that TLS makes a consequential contribution to the replication of AraC-damaged DNA; that TLS through AraC is conducted by three different pathways dependent upon Polη, Polι, and Polν, respectively; and that TLS by all these Pols incurs considerable mutagenesis. The prominent role of TLS in promoting proficient and mutagenic replication through AraC suggests that TLS inhibition in acute myeloid leukemia patients would increase the effectiveness of AraC chemotherapy; and by reducing mutation formation, TLS inhibition may dampen the emergence of drug-resistant tumors and thereby the high incidence of relapse in AraC-treated patients.

Keywords: DNA repair, DNA polymerase, DNA replication, mutagenesis, mutagenesis mechanism, acute myeloid leukemia, AraC, AraC mutagenesis, cytarabine, translesion synthesis

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML)3 is a cancer of the myeloid line of blood cells. In AML, myeloblast, an immature precursor of white blood cells in normal hematopoiesis, undergoes genetic changes that prevent its normal differentiation. The undifferentiated immature clone of myeloblasts continues to proliferate, jeopardizing the production of normal white blood cells. The replacement of normal blood cells with leukemia cells in bone marrow causes a large reduction not only in white blood cells but also in platelets and red blood cells. As a result, AML patients suffer from an increased risk of infection, anemia, and bleeding (1). The incidence of AML increases with age, and it accounts for ∼90% of acute leukemias in adults. Cytarabine (1-β-d-arabinofuranosyl cytosine) (AraC) is a drug of choice in AML treatment (2–4). Although complete remission is observed in 50–75% of cases, relapse occurs in almost all of these cases (5, 6), requiring further treatment that may include postremission chemotherapy, stem cells transplantation, or immunotherapy.

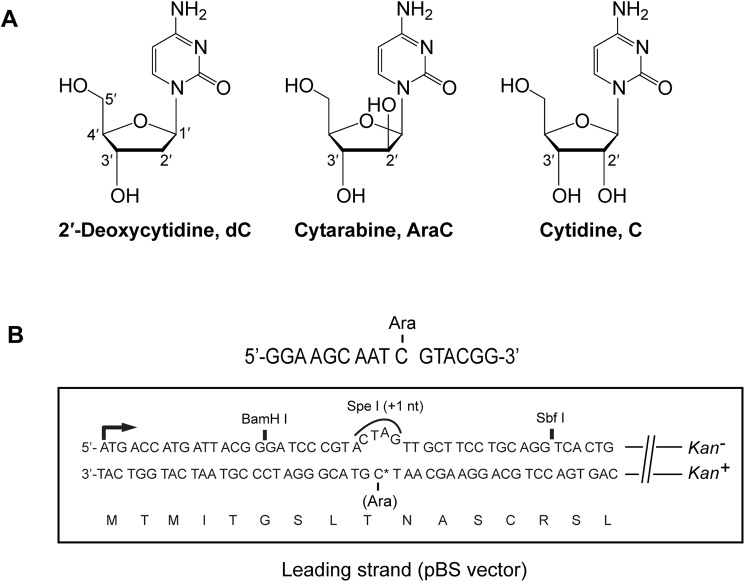

AraC differs from 2′-deoxycytidine by the presence of an additional hydroxyl group at the C2′ position of the 2′-deoxyribose, and AraC differs from cytidine in that the 2′-OH of the arabinose sugar points in a direction opposite from that of the 2′-OH of the ribose sugar in ribonucleotides (Fig. 1A). The chemotherapeutic action of AraC derives from its ability to inhibit DNA replication. Inside the cell, AraC is converted to a triphosphate (7), and AraCTP competes with dCTP for incorporation into DNA. The replicative polymerases (Pols) can insert AraC into DNA, but they are inhibited at extending from AraC at the 3′ terminus (8–10). In the next replication cycle, the presence of AraC in the template strand will be further inhibitory to DNA replication. However, human cells harbor a number of translesion synthesis (TLS) DNA Pols that can, in principle, surmount the chemotherapeutic action of AraC both by extending DNA synthesis from AraC terminated 3′ ends and by replicating through AraC in the template strand. As such, TLS Pols may play a pre-eminent role in reducing the chemotherapeutic impact of AraC, but there exists little information on how the TLS Pols enhance the replication potential of AraC-treated cells.

Figure 1.

TLS analyses opposite AraC. A, chemical structures of 2′-deoxycytidine, cytarabine, and cytidine. B, the 16-mer target sequence containing an AraC is shown on top, and the lacZ′ sequence in the leading strand in the pBS vector containing the AraC nucleotide is shown on the bottom. The AraC containing DNA strand is in-frame, and it carries the Kan+ gene. TLS through AraC generates Kan+ blue colonies.

Biochemical and structural studies have indicated that different TLS Pols are adapted for replicating through different types of DNA lesions, and depending upon the DNA lesion, a particular TLS Pol may carry out only the insertion or the extension step of TLS, or it could perform both the steps of TLS (11). For example, among the Y-family Pols, Polη has the unique ability to accommodate two template residues in its active site, and thus it can efficiently replicate through UV-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (12–15). The ability of Polι to push the template purine A or G residue into a syn conformation and to form an Hoogsteen bp with the incoming T or C, respectively, enables it to insert nucleotides (nts) opposite DNA lesions that impair Watson–Crick base pairing (16–18). Rev1 pushes the templating G residue into a solvent-filled cavity, and an Arg residue in Rev1 forms hydrogen bonds with the incoming C (19, 20); this protein template-directed mechanism of nt incorporation allows Rev1 to insert a C opposite N2-dG adducts that protrude into the DNA minor groove (21). Polκ is highly adapted for extending from such minor groove DNA lesions (22), whereas Polζ, a member of the B-family of Pols, can extend synthesis from the nt opposite from a large variety of DNA lesions (11, 17, 23–25).

Although we now have considerable information on how TLS Pols can replicate through different kinds of DNA lesions generated from exogenous and endogenous sources, this information pertains largely to DNA lesions that disrupt the base moiety and not the sugar moiety. In the absence of genetic and cellular studies, there is no clear understanding of the relevance of TLS in AraC-treated cells, and the identity of TLS Pols involved in AraC bypass is also unknown. As such, the role of TLS Pols in reducing the chemotherapeutic potential of AraC in AML remains undetermined. The mutagenic potential of TLS through AraC is also unknown. There is no information available on which TLS Pols function in an error-free manner and which function in a mutagenic fashion. Because error-prone replication by TLS Pols through the AraC lesion may contribute to the emergence of drug-resistant tumors and to the relapse of cancers, knowledge of which TLS Pols function in an error-prone manner could suggest means for preventing the emergence of drug-resistant tumors and for reducing refractory AML.

Here we identify the TLS Pols required for replicating through AraC in human cells. Our data indicate that TLS through AraC occurs via three different pathways dependent upon Polη, Polι, and Polν, respectively. TLS through AraC generates a considerable level of mutagenesis as ∼10% of TLS products harbor mutations in which an A is inserted opposite AraC, and all these Pols contribute to mutagenic TLS. The rather high mutagenicity of AraC may contribute to the emergence of drug-resistant tumors and to the relapse of cancers.

Results

Genetic control of TLS through AraC in human cells

AraC (Fig. 1A) was incorporated in the lacZ target sequence in the leading strand in the SV40-based duplex plasmid system in which bidirectional replication initiates from a replication origin (Fig. 1B). Because the lacZ sequence in the AraC-containing strand is in frame, both error-free and error-prone TLS mechanisms generate blue colonies. The other DNA strand lacking AraC contains a +1 frameshift; hence, the lacZ gene in this strand is nonfunctional. The two DNA strands are further distinguished by the kan+ (kanamycin resistance) gene in the AraC-containing strand and the kan− gene in the other strand (Fig. 1B). In this plasmid system, the number of blue colonies among the total colonies that grow on LB + Kan plates gives a very reliable estimate of TLS frequency (26).

To identify the TLS Pols involved in replicating through AraC, we examined the effects of siRNA depletions on TLS frequency. In normal human fibroblasts (HFs) treated with control (NC) siRNA, TLS occurred with a frequency of ∼47%, and depletion of Polκ or the Rev3 catalytic subunit of Polζ had no effect on TLS frequency (Table 1). Depletion of Polη or Polι, however, reduced TLS frequency to ∼33%, and depletion of Polν conferred a reduction to ∼27% (Table 1). To determine whether Pols η, ι, and ν carry out TLS independently or whether any two of these Pols function together in one TLS pathway, in which one Pol would insert a nt opposite AraC and the other Pol would extend synthesis from the inserted nt, we examined the effects of co-depletion of any two of these Pols on TLS frequency. Co-depletion of Polη and Polι reduced TLS frequency to ∼23%, and co-depletion of Polη with Polν reduced TLS frequency to ∼19% (Table 1). The observation that co-depletion of Polη with Polι or with Polν conferred a greater reduction in TLS frequency than that seen upon their individual depletion suggested that Polη functions independently of Polι or Polν. The result that the co-depletion of Polι and Polν reduced TLS frequency to ∼14% indicated that Polι and Polν function independently of one another (Table 1). Altogether, these results indicated that TLS through AraC is mediated via three independent pathways dependent upon Polη, Polι, and Polν, respectively.

Table 1.

Effects of siRNA knockdown of TLS Pols on the replicative bypass of the AraC lesion carried on the leading strand template in wildtype HFs (GM637)

| siRNA | No. Kan + colonies | No. blue colonies among Kan+ | TLS |

|---|---|---|---|

| % | |||

| NC | 523 | 248 | 47.4 |

| Polκ | 316 | 154 | 48.7 |

| Rev3 | 334 | 163 | 48.8 |

| Polη | 386 | 126 | 32.6 |

| Polι | 402 | 134 | 33.3 |

| Polν | 418 | 114 | 27.3 |

| Polη + Polι | 378 | 86 | 22.8 |

| Polη + Polν | 384 | 72 | 18.8 |

| Polι + Polν | 408 | 58 | 14.2 |

To verify this conclusion, we examined the effects of depletion of Polι or Polν in XPV cells defective in Polη. In XPV cells, TLS through AraC occurs at a frequency of ∼37%, and it is reduced to ∼25% in Polι-depleted cells and to ∼21% in Polν-depleted cells (Table 2). This reduction in TLS frequency confirms the inference that Polι and Polν act independently of Polη. The observation that co-depletion of Polι and Polν in XPV cells reduced TLS frequency to ∼7% (Table 2) adds further support to the conclusion that Pols η, ι, and ν function independently of one another in mediating TLS through AraC.

Table 2.

Effects of siRNA knockdown of TLS Pols on the replicative bypass of the AraC lesion carried on the leading strand template in XPV HFs (GM03617)

| siRNA | No. Kan + colonies | No. blue colonies among Kan+ | TLS |

|---|---|---|---|

| % | |||

| NC | 433 | 162 | 37.4 |

| Polι | 350 | 86 | 24.6 |

| Polν | 316 | 66 | 20.9 |

| Polι + Polν | 304 | 20 | 6.6 |

Mutagenicity of TLS opposite AraC

In HFs treated with control siRNA, TLS through AraC incurs significantly elevated mutagenicity, because ∼9% of TLS products harbor a mutational change in which an A is incorporated opposite AraC (Table 3). Depletion of Polη or Polι reduced the frequency of mutagenic TLS to ∼7.5%, and depletion of Polν increased the frequency of mutagenic TLS to ∼14%. Similar to that in WT HFs treated with control siRNA, in HFs depleted for Polη, Polι, or Polν, mutagenic TLS occurred via an A incorporation (Table 3). Even though all these Pols conduct error-prone TLS opposite AraC, the greater increase in mutation frequency in Polν-depleted cells than in Polη- or Polι-depleted cells suggests that Polν promotes a less error-prone mode of TLS opposite AraC than Polη or Polι.

Table 3.

Effects of siRNA knockdown of TLS Pols on mutation frequency and nucleotide inserted opposite AraC carried on the leading strand template in wild type HFs (GM637)

| siRNA | No. of Kan+ blue colonies sequenced | Nucleotide inserted |

Mutation frequency | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | G | C | T | |||

| % | ||||||

| NC | 448 | 42 | 406 | 0 | 0 | 9.4 |

| Polη | 462 | 34 | 428 | 0 | 0 | 7.4 |

| Polι | 355 | 27 | 328 | 0 | 0 | 7.6 |

| Polν | 294 | 40 | 254 | 0 | 0 | 13.6 |

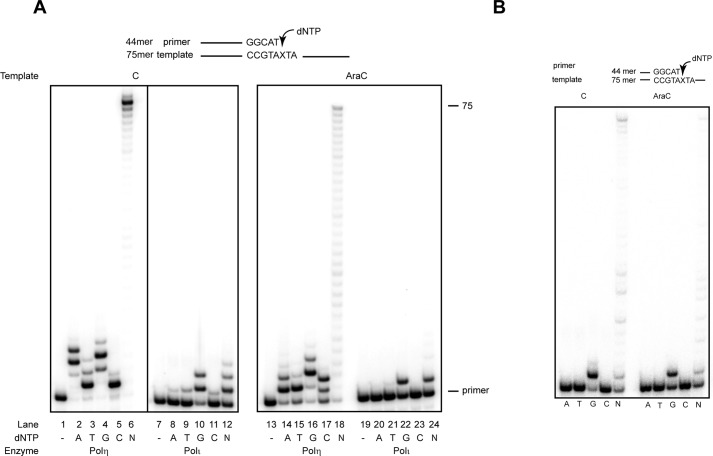

Replication through AraC by purified TLS Pols

Our genetic evidence in human cells that TLS through AraC is mediated by Polη-, Polι-, and Polν-dependent pathways and that all these Pols contribute to mutagenic TLS by inserting an A opposite AraC suggested that in biochemical assays these Pols will insert predominantly a G and less frequently an A opposite AraC. To assess this, we examined their ability for replicating through AraC in the presence of dATP, dTTP, dGTP, or dCTP, or all four dNTPs (Fig. 2). Opposite AraC, Polη inserts a G but it also inserts an A, T, or C; T or C, however, are inserted less well than an A (Fig. 2A). Opposite undamaged C, Polη exhibits high error-proneness, misincorporating all the nucleotides. In the presence of all four dNTPs, Polη replicates through AraC proficiently (Fig. 2A). In contrast to Polη, Polι inserts only a G opposite AraC, and it is inhibited at extending synthesis any further (Fig. 2A). Polν also inserts only a G opposite AraC, and in the presence of all four dNTPs, it inserts a G and then extends synthesis (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Deoxynucleotide incorporation opposite C or AraC by TLS Pols. A, deoxynucleotide incorporation opposite undamaged C or AraC template by Polη or Polι. Each protein (1 nm) was incubated with DNA substrate (10 nm) and 25 μm each of a single deoxynucleotide dATP, dTTP, dGTP, or dCTP, or 25 μm each of all four dNTPs (N) for 10 min at 37 °C. B, deoxynucleotide incorporation by Polν opposite undamaged C or AraC template. Polν (1 nm) was incubated with DNA substrate (10 nm) and with 10 μm each of a single nucleotide (A, T, G or C), or 10 μm each of all four dNTPs (N) for 10 min at 37 °C.

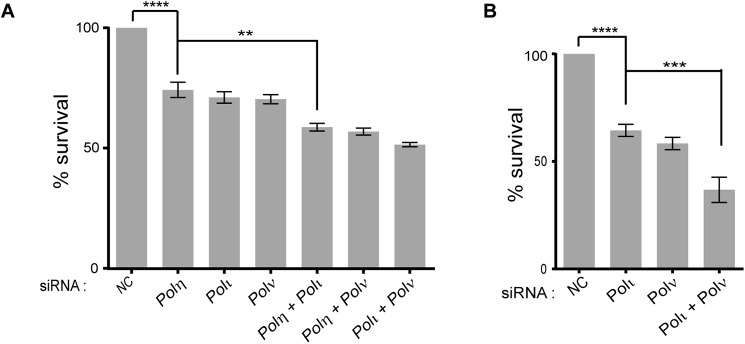

TLS Pols promote survival of AraC-treated cells

To determine the contribution of Polη, Polι, and Polν to survival in AraC-treated cells, we incubated WT HFs depleted for TLS Pols in medium containing 30 μm AraC for 48 h. Compared with cells treated with NC siRNA, survival was reduced to ∼75% in cells depleted for Polη, Polι, or Polν, and co-depletion of Polη with Polι or Polν or co-depletion of Polι with Polν reduced survival to ∼55% (Fig. 3A). In AraC-treated XPV HFs, depletion of Polι or Polν reduced survival, and co-depletion of Polι with Polν caused a further reduction in survival (Fig. 3B). Overall, all three Pols contribute approximately equally to the survival of AraC-treated cells.

Figure 3.

Effects of siRNA depletion of TLS Pols on survival of HFs treated with AraC. GM637 (WT) HFs (A) and Polη defective XP30R0 HFs (B) were depleted of TLS Pols and treated with 30 μm AraC, and cell survival was determined by MTS assays. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of results of four independent experiments. Student's two-tailed t test p values are as follows: **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001. NC, negative control.

Discussion

Genetic pathways for replicating through AraC in human cells

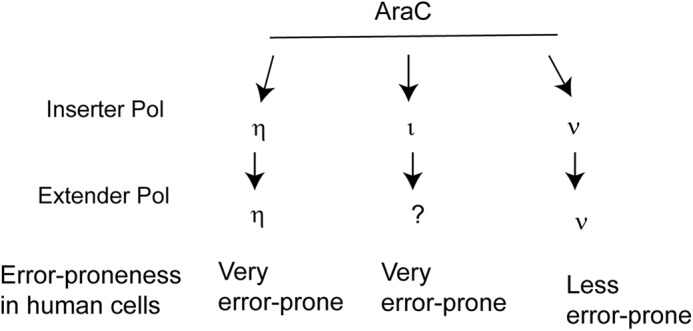

From siRNA depletion of TLS Pols in normal HFs, we inferred the involvement of Pols η, ι, and ν in TLS through AraC, and based on co-depletion analyses in HFs and XPV cells, we concluded that these Pols act independently in replicating through AraC (Fig. 4). The proficient ability of purified Polη to insert a nt opposite AraC, and to extend synthesis from the inserted nt suggests that Polη alone could conduct TLS through AraC. By contrast to Polη, Polι inserts a nt opposite AraC, but it is very inefficient in extending synthesis from the inserted nt, suggesting that the extension step is performed by an as-yet-unidentified Pol. The proficient ability of Polν for inserting a nt opposite AraC and for extending synthesis suggests that Polν alone could replicate through AraC in human cells (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

TLS Pols promote error-prone replication through AraC in human cells. TLS through AraC is mediated by the independent roles of Polη, Polι, or Polν. Based on the proficiency of purified Polη or Polν for replicating through AraC, we suggest that each of these Pols carries out both the insertion and extension steps of TLS in human cells. The inability of purified Polι to extend synthesis from the nt it inserts opposite AraC suggests that an as-yet-unidentified TLS Pol carries out this role in human cells.

High error-proneness of TLS opposite AraC

In normal human cells, Pols η, ι, and ν carry out highly error-prone TLS opposite AraC. Although the high error-proneness of Polη for TLS in human cells conforms with the error-prone synthesis by purified Polη opposite AraC, the error-proneness of TLS by Pols ι and ν in human cells is incongruent with the error-free TLS performed by these purified Pols. The rather high error-prone TLS by Pols ι and ν in human cells and not with purified Pols stands in sharp contrast to the greatly reduced mutagenicity of TLS opposite other DNA lesions in human cells compared with the high error-proneness of TLS by purified Pols. Thus, for example, TLS in human cells opposite UV-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and (6-4)-photoproducts, or opposite other DNA lesions such as thymine glycol, N3-methyladenine, N1-methyladenine, γ-hydroxy-1-N2-propano-2′-deoxyguanosine, and 1,N6-ethenodeoxyadenosine (26–34) occurs with a much higher fidelity than indicated from the fidelity of purified Pols. The much higher fidelity of TLS Pols in human cells than that indicated from in vitro biochemical analyses can be rationalized by assuming that TLS Pols in human cells are components of multiprotein ensembles, and the fidelity of TLS Pols in these ensembles is actively modulated by protein–protein interactions and post-transcriptional modifications.

Contrawise, the acquisition of reduced fidelity by Polι and Polν in TLS opposite AraC in human cells would suggest that protein–protein interactions and post-transcriptional modifications contribute to reducing the fidelity of TLS Pols opposite AraC rather than to its enhancement. The striking divergence in the fidelity of TLS Pols opposite AraC versus opposite other DNA lesions in human cells may accrue from the fact that all the other DNA lesions for which we have analyzed the genetic control and fidelity of TLS thus far are generated from normal cellular reactions or from prevalent environmental sources; consequently, strong selection pressure for maintaining cellular homeostasis would have led to the acquisition of predominantly error-free TLS mechanisms. Because AraC is not a by-product of cellular reactions or generated from persistent environmental exposure, TLS mechanisms opposite this chemotherapeutic drug would have been under no selection pressure to adapt to a more error-free mode; instead, the mechanisms that have evolved to adapt TLS Pols to act in a more error-free manner opposite the various more prevalent DNA lesions could have caused TLS Pols to operate opposite AraC in a more error-prone manner in human cells than in the purified Pol.

Role of TLS in countering the chemotherapeutic potential of AraC

TLS Pols will impact the chemotherapeutic potential of AraC first by extending synthesis from AraCMP at the 3′ terminus of the nascent DNA strand and second by replicating through AraC incorporated in the template strand. Biochemical studies have indicated a role of Polη in extending synthesis from AraC at the 3′ terminus, and structural studies have shown that Polη can accommodate AraC via specific hydrogen bonding and stacking interactions (35). Our results that TLS Pols η, ι, and ν can promote replication through AraC and that their inactivation reduces survival of AraC-treated cells suggest that TLS through AraC would contribute to reducing the effectiveness of AraC chemotherapy. In addition, our evidence that TLS through AraC generates a considerably high level of mutations explains the high mutagenicity conferred by AraC treatment (36–40) and suggests that TLS-induced mutagenicity would contribute to the emergence of drug-resistant tumors and to the relapse of cancers.

Experimental procedures

Construction of plasmid vectors containing an AraC and TLS assays

The 16-mer oligonucleotides containing an AraC were purchased from Trilink Biotechnologies, and the in-frame target sequence of the lacZ′ gene in the resulting vector is shown in Fig. 1B. The WT kanamycin gene was placed on the DNA strand containing AraC, and in this DNA strand lacz′ is in-frame and functional for β-galactosidase. The opposite DNA strand harbors an SpeI restriction site containing a +1 frameshift, which makes it nonfunctional for β-galactosidase. Details of TLS assays have been published before (26, 32).

Translesion synthesis assays in human cells and mutational analyses of TLS products

WT (GM637) or XPV (XP30RO) HFs were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (GeneDepot) containing high d-glucose (4500 mg/liter), Phenol red (15 mg/liter), and sodium pyruvate (110 mg/liter) with 10% fetal bovine serum (GeneDepot) and plated in 6-well plates at 70% confluence (approximately, 3 × 105 cells/well). The cells were transfected with 100 pmol of siRNAs with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). For the simultaneous siRNA knockdown of two genes, 100 pmol of siRNAs for each gene were mixed and transfected. After 48 h of incubation, the heteroduplex target vector DNA (1 μg) and 50 pmol of siRNA (second transfection) were co-transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). After 30 h of incubation, plasmid DNA was rescued from the cells by the alkaline lysis method and digested with DpnI to remove unreplicated plasmid DNA. The plasmid DNA was then transformed into Escherichia coli XL1-Blue super competent cells (Stratagene). Transformed bacterial cells were diluted in 1 ml of SOC medium and plated on LB/kan (25 μg/ml kanamycin) (Sigma). TLS analyses and mutational analyses of TLS products were carried out as described previously (26).

siRNA sequences used for knockdowns of human TLS Pols

The siRNA sequences used for knockdowns of Polη, Polι, and Rev3 have been published previously (26). The siRNA sequence used for Polν depletion is 5′-CCCAAUUCAGAUUACUACATT-3′.

AraC survival assay

WT (GM637) or XPV (XP30RO) HFs were transfected with siRNA, and 48 h after siRNA transfection, the cells were incubated with 30 μm AraC (Sigma) in fresh growth medium for 48 h. AraC cytotoxicity was determined by MTS assay (Promega). Briefly, 100 μl of MTS assay solutions were added to each well containing cells and incubated for 30 min. Cell viability was determined by measuring OD at 490 nm. Four independent experiments were carried out.

Protein expression and purification

Full-length human Polη and Polι were expressed as GST-tagged fusion proteins from plasmids pR30.186 and pPOL114, respectively, and purified from yeast cells as described (41–43). The GST tags were cleaved from each DNA Pol by treatment with prescission protease, leaving a 7-amino acid linker peptide at the N terminus of each protein. To express human Polν lacking the proline-rich C-terminal 39 residues (44) in yeast, a 2.6-kb E. coli codon optimized cDNA encoding amino acids 1–861 of the 900-amino acid protein was synthesized. The cDNA was amplified by PCR to add flanking 5′ and 3′ BamHI restriction endonuclease sites, and the fragment was cloned in frame with a FLAG metal affinity tag–SUMO* tag under control of a galactose inducible phosphoglycerate kinase promoter in plasmid pPM1514, generating plasmid pBJ2086. SUMO* contains residues 1–98 of the yeast SMT3 encoded protein and harbors mutations R64T and R71E, rendering it resistant to cellular sumo-proteases. Yeast strain YRP654 was transformed with plasmid pBJ2086, and cells were grown as described (41). Protein expression was induced by the addition of 2% galactose, and cells were grown for 16 h. Polν(1–861) was affinity-purified using anti-FLAG agarose. Clarified protein extract was prepared from 10 g of yeast cells disrupted by French press as described (41), except that breakage buffer additionally contained 0.1% Triton X-100. The clarified protein extract was rocked with 0.1 ml of M2 αFLAG–agarose (Sigma) for 3 h and subsequently washed with 20 volumes of 1× GBB (GST binding buffer) containing 500 mm NaCl and 0.1% Triton X-100. The M2 αFLAG–agarose beads were equilibrated in 1× GBB (GST binding buffer) containing 150 mm NaCl and 0.01% Triton X-100, and protein was eluted by the addition of 0.1 mg/ml FLAG peptide. Eluted protein was aliquoted and frozen at −70 °C.

DNA polymerase assays

DNA substrates consisted of a radiolabeled oligonucleotide primer annealed to a 75-nt-oligonucleotide DNA template by heating a mixture of primer/template at a 1:1.5 molar ratio to 95 °C and allowing it to cool to room temperature for several hours. The template 75-mer oligonucleotide contained the sequence 5′-AGC AAG TCA CCA ATG TCT AAG AGT TCG TAT CAT GCC TAC ACT GGA GTA CCG GAG CAT CGT CGT GAC TGG GAA AAC-3′, and it harbored an undamaged C or an AraC at the underlined position. For examining the incorporation of dATP, dTTP, dCTP, or dGTP nucleotides, or of all four dNTPs, a 44-mer primer 5′-GTT TTC CCA GTC ACG ACG ATG CTC CGG TAC TCC AGT GTA GGC AT-3′ was annealed to the above mentioned 75-mer templates.

The standard DNA polymerase reaction (5 μl) contained 25 mm Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 100 μg/ml BSA, 10% glycerol, 10 nm DNA substrate, and 1 nm of Polη, Polι, or Polν. For nucleotide incorporation assays with Polη or Polι, 25 μm dATP, dTTP, dCTP, or dGTP (Roche Biochemicals) were used, and for examining synthesis through the undamaged C or AraC, all four dNTPs (25 μm each) were used. For nucleotide incorporation assays with Polν, 10 μm dATP, dTTP, dCTP, or dGTP were used, and for examining synthesis through the undamaged C or AraC, all four dNTPs (10 μm each) were used. The reactions were carried out for 10 min at 37 °C. Reaction products were resolved on a 12% polyacrylamide gel containing 8 m urea and analyzed by a PhosphorImager.

Author contributions

J.-H. Y., L. P., and S. P. conceptualization; J.-H. Y. formal analysis; J.-H. Y., L. P., and S. P. validation; J.-H. Y., J. R. C., and L. P. investigation; J.-H. Y. and J. R. C. methodology; J.-H. Y., J. R. C., L. P., and S. P. writing-review and editing; L. P. resources; L. P. and S. P. supervision; L. P. and S. P. project administration; S. P. funding acquisition; S. P. writing-original draft.

Acknowledgment

We thank Robert Johnson for help with preparation of this manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant CA200575. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- AML

- acute myeloid leukemia

- AraC

- 1-β-d-arabinofuranosyl cytosine

- NC

- negative control

- nt

- nucleotide

- Pol

- polymerase

- TLS

- translesion synthesis

- HF

- human fibroblast.

References

- 1. Cooper T. M., Hasle H., and Smith F. O. (2011) Acute myeloid leukemia, myeloproliferative and myelodysplastic disorders. In Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology (Pizzo P. A., and Poplack D. G., eds) pp. 566–610, Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kadia T. M., Ravandi F., O'Brien S., Cortes J., and Kantarjian H. M. (2015) Progress in acute myeloid leukemia. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 15, 139–151 10.1016/j.clml.2014.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lichtman M. A. (2013) A historical perspective on the development of the cytarabine (7 days) and daunorubicin (3 days) treatment regimen for acute myelogenous leukemia: 2013 the 40th anniversary of 7+3. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 50, 119–130 10.1016/j.bcmd.2012.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Magina K. N., Pregartner G., Zebisch A., Wölfler A., Neumeister P., Greinix H. T., Berghold A., and Sill H. (2017) Cytarabine dose in the consolidation treatment of AML: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood 130, 946–948 10.1182/blood-2017-04-777722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cancer Facts and Figures 2018. American Cancer Society (2018) [Google Scholar]

- 6. Walter R. B., Othus M., Burnett A. K., Löwenberg B., Kantarjian H. M., Ossenkoppele G. J., Hills R. K., Ravandi F., Pabst T., Evans A., Pierce S. R., Vekemans M. C., Appelbaum F. R., and Estey E. H. (2015) Resistance prediction in AML: analysis of 4601 patients from MRC/NCRI, HOVON/SAKK, SWOG and M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. Leukemia 29, 312–320 10.1038/leu.2014.242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grant S. (1998) Ara-C: cellular and molecular pharmacology. Adv. Cancer Res. 72, 197–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harrington C., and Perrino F. W. (1995) The effects of cytosine arabinoside on RNA-primed DNA synthesis by DNA polymerase α-primase. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 26664–26669 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mikita T., and Beardsley G. P. (1988) Functional consequences of the arabinosylcytosine structural lesion in DNA. Biochemistry 27, 4698–4705 10.1021/bi00413a018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Perrino F. W., Mazur D. J., Ward H., and Harvey S. (1999) Exonucleases and the incorporation of aranucleotides into DNA. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 30, 331–352 10.1007/BF02738118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Prakash S., Johnson R. E., and Prakash L. (2005) Eukaryotic translesion synthesis DNA polymerases: specificity of structure and function. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 74, 317–353 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Biertümpfel C., Zhao Y., Kondo Y., Ramón-Maiques S., Gregory M., Lee J. Y., Masutani C., Lehmann A. R., Hanaoka F., and Yang W. (2010) Structure and mechanism of human DNA polymerase η. Nature 465, 1044–1048 10.1038/nature09196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnson R. E., Prakash S., and Prakash L. (1999) Efficient bypass of a thymine-thymine dimer by yeast DNA polymerase, Polη. Science 283, 1001–1004 10.1126/science.283.5404.1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Masutani C., Kusumoto R., Yamada A., Dohmae N., Yokoi M., Yuasa M., Araki M., Iwai S., Takio K., and Hanaoka F. (1999) The XPV (xeroderma pigmentosum variant) gene encodes human DNA polymerase η. Nature 399, 700–704 10.1038/21447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Silverstein T. D., Johnson R. E., Jain R., Prakash L., Prakash S., and Aggarwal A. K. (2010) Structural basis for the suppression of skin cancers by DNA polymerase eta. Nature 465, 1039–1043 10.1038/nature09104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nair D. T., Johnson R. E., Prakash L., Prakash S., and Aggarwal A. K. (2005) Human DNA polymerase ι incorporates dCTP opposite template G via a G·C+ Hoogsteen base pair. Structure 13, 1569–1577 10.1016/j.str.2005.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nair D. T., Johnson R. E., Prakash L., Prakash S., and Aggarwal A. K. (2006) Hoogsteen base pair formation promotes synthesis opposite the 1,N6-ethenodeoxyadenosine lesion by human DNA polymerase iota. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 619–625 10.1038/nsmb1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nair D. T., Johnson R. E., Prakash S., Prakash L., and Aggarwal A. K. (2004) Replication by human DNA polymerase ι occurs via Hoogsteen base-pairing. Nature 430, 377–380 10.1038/nature02692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nair D. T., Johnson R. E., Prakash L., Prakash L., and Aggarwal A. K. (2005) Rev1 employs a novel mechanism of DNA synthesis using a protein template. Science 309, 2219–2222 10.1126/science.1116336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Swan M. K., Johnson R. E., Prakash L., Prakash L., and Aggarwal A. K. (2009) Structure of the human REV1–DNA–dNTP ternary complex. J. Mol. Biol. 390, 699–709 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nair D. T., Johnson R. E., Prakash L., Prakash L., and Aggarwal A. K. (2008) Protein-template directed synthesis across an acrolein-derived DNA adduct by yeast Rev1 DNA polymerase. Structure 16, 239–245 10.1016/j.str.2007.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lone S., Townson S. A., Uljon S. N., Johnson R. E., Brahma A., Nair D. T., Prakash S., Prakash L., and Aggarwal A. K. (2007) Human DNA polymerase κ encircles DNA: implications for mismatch extension and lesion bypass. Mol. Cell 25, 601–614 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haracska L., Unk I., Johnson R. E., Johansson E., Burgers P. M., Prakash S., and Prakash L. (2001) Roles of yeast DNA polymerases δ and ζ and of Rev1 in the bypass of abasic sites. Genes Dev. 15, 945–954 10.1101/gad.882301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johnson R. E., Haracska L., Prakash S., and Prakash L. (2001) Role of DNA polymerase η in the bypass of a (6-4) TT photoproduct. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 3558–3563 10.1128/MCB.21.10.3558-3563.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johnson R. E., Washington M. T., Haracska L., Prakash S., and Prakash L. (2000) Eukaryotic polymerases ι and ζ act sequentially to bypass DNA lesions. Nature 406, 1015–1019 10.1038/35023030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yoon J.-H., Prakash L., and Prakash S. (2009) Highly error-free role of DNA polymerase η in the replicative bypass of UV induced pyrimidine dimers in mouse and human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 18219–18224 10.1073/pnas.0910121106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Conde J., Yoon J. H., Roy Choudhury J., Prakash L., and Prakash S. (2015) Genetic control of replication through N1-methyladenine in human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 29794–29800 10.1074/jbc.M115.693010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yoon J. H., Hodge R. P., Hackfeld L. C., Park J., Roy Choudhury J., Prakash S., and Prakash L. (2018) Genetic control of predominantly error-free replication through an acrolein-derived minor-groove DNA adduct. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 2949–2958 10.1074/jbc.RA117.000962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yoon J. H., Roy Choudhury J., Park J., Prakash S., and Prakash L. (2014) A role for DNA polymerase θ in promoting replication through oxidative DNA lesion, thymine glycol, in human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 13177–13185 10.1074/jbc.M114.556977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yoon J. H., Roy Choudhury J., Park J., Prakash S., and Prakash L. (2017) Translesion synthesis DNA polymerases promote error-free replication through the minor-groove DNA adduct 3-deaza-3-methyladenine. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 18682–18688 10.1074/jbc.M117.808659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yoon J.-H., Bhatia G., Prakash S., and Prakash L. (2010) Error-free replicative bypass of thymine glycol by the combined action of DNA polymerases κ and ζ in human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 14116–14121 10.1073/pnas.1007795107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yoon J.-H., Prakash L., and Prakash S. (2010) Error-free replicative bypass of (6-4) photoproducts by DNA polymerase ζ in mouse and human cells. Genes Dev. 24, 123–128 10.1101/gad.1872810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yoon J. H., Johnson R. E., Prakash L., and Prakash S. (2019) DNA polymerase θ accomplishes translesion synthesis opposite 1,N6-ethenodeoxyadenosine with a remarkably high fidelity in human cells. Genes Dev. 33, 282–287 10.1101/gad.320531.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yoon J. H., McArthur M. J., Park J., Basu D., Wakamiya M., Prakash L., and Prakash S. (2019) Error-prone replication through UV lesions by DNA polymerase θ protects against skin cancers. Cell 176, 1295–1309.e15 10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rechkoblit O., Choudhury J. R., Buku A., Prakash L., Prakash S., and Aggarwal A. K. (2018) Structural basis for polymerase η–promoted resistance to the anticancer nucleoside analog cytarabine. Sci. Rep. 8, 12702 10.1038/s41598-018-30796-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ding L., Ley T. J., Larson D. E., Miller C. A., Koboldt D. C., Welch J. S., Ritchey J. K., Young M. A., Lamprecht T., McLellan M. D., McMichael J. F., Wallis J. W., Lu C., Shen D., Harris C. C., et al. (2012) Clonal evolution in relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Nature 481, 506–510 10.1038/nature10738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fordham S. E., Cole M., Irving J. A., and Allan J. M. (2015) Cytarabine preferentially induces mutation at specific sequences in the genome which are identifiable in relapsed acute myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia 29, 491–494 10.1038/leu.2014.284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Garg M., Nagata Y., Kanojia D., Mayakonda A., Yoshida K., Haridas Keloth S., Zang Z. J., Okuno Y., Shiraishi Y., Chiba K., Tanaka H., Miyano S., Ding L. W., Alpermann T., Sun Q. Y., et al. (2015) Profiling of somatic mutations in acute myeloid leukemia with FLT3-ITD at diagnosis and relapse. Blood 126, 2491–2501 10.1182/blood-2015-05-646240,10.1182/blood.V126.23.2491.2491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Greif P. A., Hartmann L., Vosberg S., Stief S. M., Mattes R., Hellmann I., Metzeler K. H., Herold T., Bamopoulos S. A., Kerbs P., Jurinovic V., Schumacher D., Pastore F., Bräundl K., Zellmeier E., et al. (2018) Evolution of cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia during therapy and relapse: an exome sequencing study of 50 patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 1716–1726 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kunz J. B., Rausch T., Bandapalli O. R., Eilers J., Pechanska P., Schuessele S., Assenov Y., Stütz A. M., Kirschner-Schwabe R., Hof J., Eckert C., von Stackelberg A., Schrappe M., Stanulla M., Koehler R., et al. (2015) Pediatric T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia evolves into relapse by clonal selection, acquisition of mutations and promoter hypomethylation. Haematologica 100, 1442–1450 10.3324/haematol.2015.129692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Johnson R. E., Prakash L., and Prakash S. (2006) Yeast and human translesion DNA synthesis polymerases: expression, purification, and biochemical characterization. Methods Enzymol. 408, 390–407 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)08024-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Washington M. T., Johnson R. E., Prakash L., and Prakash S. (2003) The mechanism of nucleotide incorporation by human DNA polymerase η differs from that of the yeast enzyme. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 8316–8322 10.1128/MCB.23.22.8316-8322.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Washington M. T., Johnson R. E., Prakash L., and Prakash S. (2004) Human DNA polymerase ι utilizes different nucleotide incorporation mechanisms dependent upon the template base. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 936–943 10.1128/MCB.24.2.936-943.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Marini F., Kim N., Schuffert A., and Wood R. D. (2003) POLN, a nuclear PolA family DNA polymerase homologous to the DNA cross-link sensitivity protein Mus308. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 32014–32019 10.1074/jbc.M305646200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]